Abstract

An important evolutionary function of emotions is to prime individuals for action. Although functional neuroimaging has provided evidence for such a relationship, little is known about the anatomical substrates allowing the limbic system to influence cortical motor‐related areas. Using diffusion‐weighted magnetic resonance imaging and probabilistic tractography on a cohort of 40 participants, we provide evidence of a structural connection between the amygdala and motor‐related areas (lateral and medial precentral, motor cingulate and primary motor cortices, and postcentral gyrus) in humans. We then compare this connection with the connections of the amygdala with emotion‐related brain areas (superior temporal sulcus, fusiform gyrus, orbitofrontal cortex, and lateral inferior frontal gyrus) and determine which amygdala nuclei are at the origin of these projections. Beyond the well‐known subcortical influences over automatic and stereotypical emotional behaviors, a direct amygdala‐motor pathway might provide a mechanism by which the amygdala can influence more complex motor behaviors. Hum Brain Mapp 35:5974–5983, 2014. © 2014 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

Keywords: amygdala, motor system, diffusion‐weighted magnetic resonance imaging, social responding

INTRODUCTION

The ability to detect and adjust one's own behavior to others' emotional signals has functional consequences for social interaction. The importance of these social skills in social species has led to the evolution of a number of neurological adaptations, that is, the “social brain” network. More specifically, the amygdala plays a pivotal role in emotion‐related functions and context‐appropriate social behaviors [Adolphs, 2010]. Following amygdala lesions, non‐human animals respond inappropriately to affective stimuli [Aggleton and Passingham, 1981] and display atypical social behaviors [Emery et al., 2001]. One way to account for these findings is that the amygdala has direct anatomical connections to subcortical and cortical areas allowing for fast and adaptive behavioral responses to social signals [Amaral and Price 1984; Avendano et al. 1983].

Although there is an abundant literature in animal research on the emotional motor subcortical system which includes the amygdala [Holstege, 1991], little is known about its connections to cortical motor‐related areas. Yet, there is sparse but consistent evidence from animal studies that the amygdala is in a position to influence behavior via cortical motor‐related areas: amygdala projections have been detected in the supplementary motor area (SMA), in the cingulate motor areas [Ghashghaei et al. 2007; Jürgens, 1984; Morecraft et al., 2007], in the lateral premotor cortex [Amaral and Price, 1984; Avendano et al., 1983; Ghashghaei et al., 2007; Llamas et al., 1985], and in the motor cortex [Llamas et al., 1977; Llamas et al., 1985; Macchi et al., 1978; Sripanidkulchai et al., 1984] of cats and monkeys, as well as in the somatosensory cortex in rats [Sripanidkulchai et al., 1984]. Of relevance here, all the aforementioned cortical regions have access‐either directly or indirectly‐to descending motor pathways [Dum and Strick, 2005], and can thus directly influence ongoing behavior.

In humans, it has been have demonstrated that, during the perception of emotional expressions, the amygdala and motor‐related areas are coactivated [Conty et al., 2012; de Gelder et al., 2004; Grèzes et al., 2013; Grosbras and Paus, 2006; Pichon et al., 2008; Pichon et al., 2009; Van den Stock et al., 2011] and functionally connected [Ahs et al., 2009; Grèzes et al., 2009; Qin et al., 2012; Roy et al., 2009; Voon et al., 2010]. Finally, direct evidence that emotional stimuli prime the motor system and facilitate action readiness was provided by transcranial magnetic stimulation studies [Baumgartner et al., 2007; Coelho et al., 2010; Coombes et al., 2009; Hajcak et al., 2007; Oliveri et al., 2003; van Loon et al., 2010]. The amygdala thus appears to work in tandem with cortical motor‐related areas, possibly to facilitate or influence the preparation of adaptive responses to social signals. However, it is currently unknown whether, in humans, there is a direct anatomical connection from the amygdala to the motor system.

Here, we present diffusion‐tensor magnetic resonance imaging (dMRI) evidence using high quality data from 40 subjects in the Human Connectome project (HCP) to investigate the existence of a human equivalent of the anatomical connections between the amygdala to cortical motor‐related areas. We also describe the nesting of these connections within the network linking the amygdala to emotion‐related brain structures involved in the perception of dynamic emotional expressions [superior temporal sulcus (STS), fusiform gyrus (FG), lateral inferior frontal gyrus (IFG), and orbitofrontal cortex (OFC)] [Grèzes et al., 2013; Pichon et al., 2009, 2012]. Finally, we describe which amygdala nuclei are at the origin of these projections.

METHODS

HCP Diffusion EPI and Anatomical Dataset

High angular resolution dMRI data from the HCP (Q2 release, http://www.humanconnectome.org/data/) were analyzed in a pool of 40 unrelated participants (21 females, range of age: 22–35).

Images were acquired with the 3T Siemens Skyra (Siemens AG, Erlanger, Germany) and a Siemens SC72 gradient coil. One hundred and eleven axial slices of diffusion EPI data were acquired using multiband pulse sequences [Feinberg et al., 2010; Moeller et al., 2010; Setsompop et al., 2012; Xu et al., 2012] and consequently reconstructed with the SENSE1 algorithm [Sotiropoulos et al., 2013]. Two hundred and seventy diffusion weighting directions (b = 1,000, 2,000, and 3,000 s/mm‐2; TR: 5,520 ms; TE: 89.5ms; voxel size: 1.25 × 1.25 × 1.25 mm) and six b = 0 volumes were interspersed throughout each run. The dataset was corrected for eddy‐current distortion and movement following Andersson et al.'s approach [Andersson et al., 2012, 2003]. Full information about the acquisition parameters of the HCP data acquisition are described in Van Essen et al. [2013]. In parallel, T1 weighted images were acquired with a pixel dimension of 0.7 × 0.7 × 0.7 mm (TR: 2.4 s; TE: 2.14 ms; TI: 1,000 ms). The anatomical images were defaced using the algorithm reported in Milchenko and Marcus [2013].

Seed, Target and Masks Regions

We used FreeSurfer (http://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu) to reconstruct cortical and subcortical parcellation from each subject's T1 scan. The anatomical nomenclature of each target and mask given by FreeSurfer [Destrieux et al., 2010] can be found in the Supporting Information Table S1.

First, we studied the anatomical connectivity from the amygdala to a priori defined cortical motor‐related targets in single‐subject dMRI data. The targets were defined as follow: precentral (Fig. 1A, green), central (Fig. 1A, red), postcentral (Fig. 1A, yellow), and mid‐cingulate (Fig. 1A, dark Blue) sulci, and cortices. The pre‐SMA (Fig. 1A, light blue) target corresponds to the intersection between the superior frontal gyrus region in FreeSurfer and the pre‐SMA as delimited by the Automated Anatomical Labeling (http://qnl.bu.edu/obart/explore/AAL/).

Figure 1.

Overview of tractography results. (A) Motor‐related cortical targets: postcentral (yellow), central (red), precentral target (green), pre‐SMA (light blue), and mid‐cingulate (dark blue) sulci and cortices. (B) Mean number of reconstructed tracts between amygdala and motor‐related cortical targets. The error bars are SEM. (C) Mean reconstructed tracts (red) from amygdala (orange) to motor‐related cortical targets as found with probabilistic fiber tracking dMRI and displayed using Mango (3.0.4). (D) Motor target (red) and emotion‐related targets: the superior temporal sulcus (STS, dark blue), the fusiform gyrus (FG, violet), the lateral inferior frontal gyrus (IFG, green), and the orbitofrontal cortex (OFC, yellow). (E) Mean number of reconstructed tracts between amygdala and the motor‐related cortical target, STS, FG, IFG, and OFC. The error bars are SEM. (F) Mean number of reconstructed tracts from amygdala to motor‐related cortical target (red), the IFG (green) and OFC (yellow), the FG (violet) and STS (blue) as found with probabilistic fiber tracking dMRI and displayed using Mango (3.0.4).

In both Amaral and Price [1984] and Morecraft et al. [2007], the labeled fibers between the amygdala and cortical motor‐related areas were observed in the autoradiographs traveling in the external capsule. We used exclusion and inclusion masks to isolate the white matter reconstructed bundles that travel from the amygdala to the motor system in the external capsule from other potential paths that do not travel in the external capsule and/or that traveled through the basal ganglia (and as such would not be direct). To do so, we excluded the Caudate, Putamen, Pallidum, Thalamus, Corpus Callosum, and Ventricles. As the putamen and pallidum were used as exclusion criteria, it was crucial that they did not include part of the external capsule. Yet, as both the putamen and pallidum segmentation given by FreeSurfer were bigger than expected (because the contrast is not well defined on the T1 image), and thus included part of the external capsule, we used the fractional anisotropy (FA) map to further reduce the mask of these two regions by keeping only voxels where the FA was lower than 0.2. Also, the Brainstem was excluded to avoid including the paths from the amygdala to emotional motor subcortical system (notably the periaqueductal gray [Holstege, 1991]) involved in species‐specific basic survival behaviors.

Second, we compared connections of amygdala with cortical motor‐related areas with connections of amygdala with other brain structures (STS, FG, lateral IFG, and OFC), which are found to be systematically coactivated with the premotor cortex during emotion processing [Grèzes et al., 2013; Pichon et al., 2008, 2009, 2012]. These four brain areas are well known to play a crucial role in social perception and in assigning emotional significance to perceived events [Barbas, 2000; Brothers, 1990]. The following targets were thus included in Freesurfer: a Motor target (Fig. 1D, red), the STS (Fig. 1D, blue), and the FG (Fig. 1D, purple). The IFG included its orbital, opercular, and triangularis parts (Fig. 1D, green) as our previous functional neuroimaging studies have revealed activations which could be localized in areas 44, 45, and/or 47 [Pichon et al., 2012]. The orbitofrontal region (Fig. 1D, yellow) included the anterior cingulate gyrus and sulcus, the orbital, rectus, and sub‐callosal gyrus. To properly target those regions rather than neighbors, we used exclusion mask of hippocampus, anterior cingulate, as well as the superior temporal and supramarginal regions. In addition, as the connectivity between the amygdala and OFC and amygdala and IFG are known to be mediated via the uncinate fascicle [Catani and Thiebaut de Schotten, 2012] that passes throughout the external capsule as the motor‐amygdala pathway, we used the same exclusion and inclusion masked as described in the first analysis.

Cortical and Subcortical Parcellation

In a first analysis (Fig. 1A–C), the parcellated cortical regions were several independent functional cortical motor‐related areas (i.e., postcentral, central, precentral, pre‐SMA, and mid‐cingulate) to look at the distribution of the pathways across the system.

In a second analysis (Fig. 1D–F), the aforementioned parcellated cortical regions were grouped into a single motor target and four emotion‐related brain targets (OFC, IFG, FG and STS). In both analyses, the resulting masks of the amygdala and cortical regions were provided as seed and target masks, respectively, for tractography.

Probabilistic tractography between the amygdala and cortical targets was performed using the diffusion toolbox (FDT) available in FSL [Woolrich et al., 2009] (FMRIB Software Library, http://www.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl/). We computed the probabilistic diffusion model on preprocessed data using the software module BEDPOSTX that can estimate the distribution of up to three crossing fiber bundles in each voxel. We took into account the multiple B‐values of the acquisition [Jbabdi et al., 2012]. For each subject, probabilistic fiber tractography was then computed using the software module Probtrackx on the BEDPOSTX output to generate an estimate of the most likely connectivity distribution between the seed and the targets [Behrens et al., 2007]. We used the standard parameters with 20,000 sample tracts per seed voxel, a curvature threshold of 0.2, a step length of 0.5 and a maximum number of steps of 2,000. Using the amygdala as the seed and every cortical region as classification targets, Probtrackx quantified the connectivity values between the seed mask and target masks. The average connectivity probability value between the seed and each target region was then calculated across all participants.

A third analysis consisted in identifying the subregion of origin of different studied paths. To do this, we used the cytoarchitectonic probability maps of the amygdala's major subregions: the centromedial group (CM: central and medial nuclei), the basolateral group (BL: lateral, basolateral, basomedial, and paralaminar nuclei), and the superficial group (SF: anterior amygdaloid area, ventral, and posterior cortical nuclei) [Amunts et al., 2005] as provided by the SPM Anatomy toolbox [Version 1.4, Eickhoff et al., 2005]. By quantifying the number of reconstructed tracts that end in a given target for each voxel of the seed, Probtrackx provides information about the subregion of the seed that is at the origin of the reconstructed tracts to each target. We then calculated the intercept between each of these subregions of the amygdala with each cytoarchitectonic probability map (CM, BL, and SF) and computed the average probability of being in the amygdala subregion X weighted by the probability to be connected to the region of interest Y.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses on Probtrackx outputs were conducted using SPSS 18.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL). Repeated‐measures analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were performed to test whether connectivity pattern differed between hemispheres, seed regions, and target regions. All tests were two‐tailed. Greenhouse‐Geisser epsilons (ε) and P values after correction as well as effect sizes (partial eta‐squared ( ) for F statistics) were reported where appropriate. Post hoc comparisons (two‐tailed t‐tests) were performed for the analysis of simple main effects when significant interactions were obtained.

RESULTS

Evidence for Direct Structural Connections Between the Amygdala and Motor‐Related Areas

A first analysis looked for evidence of direct structural connections between the amygdala seed and several independent cortical motor‐related targets (precentral, central, postcentral gyri, and sulci as well as motor cingulate cortex). We examined the number of reconstructed tracts going from the amygdala and reaching each target of interest [Eickhoff et al., 2010]. The statistical thresholding of probabilistic tractography is an unsolved issue. Here, we considered the connectivity between two brain areas to be reliable, and to genuinely exist if there was at least 10 pathways between the seed and the target and if these 10 reconstructed pathways were revealed in more than 50% of the participants [Blank et al., 2011].

Here, we found confirmation that the amygdala and motor‐related areas are connected via direct structural tracts traveling in the external capsule (See Supporting Information Table S2 and Fig. 1B,C). Only two participants out of forty did not show at least 10 pathways between the amygdala and the mid‐cingulate target and one participant for the postcentral target. The present human paths revealed with tractography are very similar to what was previously shown in animal neuronal tracing studies [Amaral and Price, 1984; Avendano et al., 1983] (see Fig. 2) and as such provide validity of our methods and results.

Figure 2.

(A–C) Reconstructed structural tracts (red) from the amygdala to several motor‐related areas (orange) as found with probabilistic fiber tracking dMRI and displayed using Mango (3.0.4) for a representative participant. (A) Superior axial section showing that the tracts were traveling in the external capsule, (B) coronal section, and (C) sagittal section. (D) Distribution of anterogradely labeled cells (red) in lateral premotor cortex and motor cingulate cortex (orange) following an injection (red) of three H‐amino acids into basal nucleus of amygdala of a monkey [case DM28L modified from Avendano et al., 1983].

We found a main effect of Targets (F (4,156) = 7.478, P < 0.001, ɛ = 0.44, P corr = 0.002, = 0.161). The probability value of reconstructed bundles from the amygdala to the mid‐cingulate target was lower than all other bundles (all Ps < 0.05) and the probability value from the amygdala to the postcentral target was significantly lower than those reaching the central target (P = 0.009). There was no difference in the number of reconstructed tracts between the two hemispheres (F (1,39) = 2.184, P < 0.148, = 0.053), and no interaction between hemispheres and targets (F (4,156) = 1,682, P < 0.157, ɛ = 0.42, P corr = 0.197, = 0.041).

Projections from Amygdala to Motor and Emotion‐Related Targets

In a second analysis, we examined the reconstructed tracts from the amygdala to a single motor target constituted by our previously studied motor‐related areas (i.e., postcentral, central, precentral, pre‐SMA, and mid‐cingulate) and to four emotion‐related areas (OFC, lateral IFG, FG, and STS) (See Supporting Information Table S3 and Fig. 1E,F). The amygdala‐motor, amygdala‐IFG, and amygdala‐OFC pathways were forced to pass throughout the external capsule. There were more reconstructed tracts in the left hemisphere than in the right hemisphere (F (1,39) = 5.44, P = 0.025, = 0.122), but no interaction between hemispheres and targets (F (4,156) = 2.26, P = 0.065, ɛ = 0.30, P corr = 0.135). There was also a main effect of targets (F (4,156) = 45.27, P < 0.001, ɛ = 0.28, P corr < 0.001, = 0.537). The results can be summarized as follow: (1) the probability value of reconstructed bundles differed significantly between each pathway and the other four (all Ps < 0.005); (2) the probability value of reconstructed bundles from the amygdala to the STS target was higher than all other bundles (all Ps < 0.001), and (3) the probability value of reconstructed bundles from the amygdala to the OFC target through the external capsule was lower than all other bundles (all Ps < 0.002) (See Supporting Information Table S3 and Fig. 1E,F).

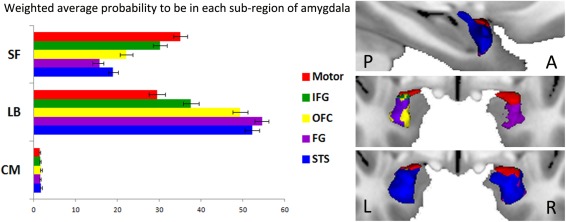

Amygdala Nuclei at the Origin of the Projections from Motor and Emotion‐Related Targets

We finally investigated which amygdala nuclei were at the origin of the aforementioned paths (see Supporting Information Table S4 and Fig. 3). To do so, we calculated the intercept between each cytoarchitectonic probability map (CM, BL, and SF) of the amygdala with each subregion at the origin of the reconstructed tracts to each target to compute a weighted average probability to be in the subregion X. We found a main effect of Nuclei (F (2,78) = 278.25, P < 0.001, ɛ = 0.58, P corr < 0.001, = 0.877), a main effect of targets (F (4,156) = 12.86, P < 0.001, ɛ = 0.42, P corr < 0.001, = 0.248) and hemisphere (F (1,39) = 111.43, P < 0.001, = 0.741) and a Nuclei × Targets × Hemisphere interaction (F (8,312) = 6.66, P < 0.001, ɛ = 0.33, P corr = 0.001, = 0.146). The main results are the following ones: (1) there is no difference between the paths regarding the centromedial nucleus (all Ps > 0.13); (2) the motor path originates from both the basolateral and the superficial nuclei (P = 0.066); (3) all paths implicate the basolateral nucleus more than the motor path (all Ps < 0.001); (4) the superficial nucleus is more implicated for the motor path compared to the other ones (all Ps < 0.001).

Figure 3.

Amygdala subregions of origin of the reconstructed paths. (A) Weighted average probability of overlap between each voxel of the amygdala at the origin of the reconstructed tracts to each target [motor target (red), superior temporal sulcus (STS, blue), Fusiform Gyrus (FG, violet), Inferior Frontal Gyrus (IFG, green), and orbitofrontal cortex (OFC, yellow)] with each cytoarchitectonic probability map [centromedial group (CM), the basolateral group (BL), and the superfial group (SF)]. (B) Subregions of the seed at the origin of the reconstructed tracts to each target. P: Posterior and A: Anterior part of the brain; L: Left and R: Right hemisphere.

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrates the existence of a structural connection between the amygdala and the cortical motor‐related areas in humans. Using axonal tracing, animal studies have long demonstrated the existence of monosynaptic anatomical connectivity between the amygdala and cortical motor areas [Llamas et al., 1977, 1985; Macchi et al., 1978; Morecraft et al., 2004]. Here, dMRI and probabilistic tractography techniques allowed us to provide the first evidence of a human homolog of this amygdala‐motor pathway. Figure 2 shows that the present human paths are very similar to those previously shown in animal neuronal tracing studies [Avendano et al., 1983].

The amygdala is part of the neural network that underlies normal social behavior and is a crucial component sustaining context‐appropriate social behaviors [Adolphs, 2010]. Existing data indeed suggest that the basolateral complex of the amygdala regulates complex behaviors in tandem with the prefrontal cortex and the ventral striatum [Groenewegen and Trimble, 2007; Mogenson et al., 1980] and that species‐specific basic survival behaviors are mediated by the emotional motor subcortical system, which includes the central nucleus of the amygdala and the periaqueductal gray [Holstege, 1991]. Here, we revealed that the amygdala also accesses descending corticospinal tracts via the premotor and primary motor cortex [Dum and Strick, 2005] and is, therefore, in a good anatomical position to exert significant influence over purposive motor functions.

The present study indicates that, in humans, the reconstructed tracts from the amygdala to cortical motor‐related areas mainly arise from basolateral and superficial subregions. Of interest, recent data in both monkeys and humans have revealed that these two subregions are especially sensitive to social stimuli [Ball et al., 2009; Goossens et al., 2009; Hoffman et al., 2007]. In line with the idea that the tracts mainly originate from basolateral and superficial regions, previous studies in cats and monkeys indicate that the projections to the motor system arise from the magnocellular division of the basal nucleus of the amygdaloid complex [Amaral and Price, 1984; Llamas et al., 1977, 1985; Macchi et al., 1978; Morecraft et al., 2007]. Also, findings from a comparative study between rats, monkeys, and humans further demonstrate that the connectivity of the central nucleus of the amygdala with visceral and autonomic systems is conserved over the course of evolution with only slight differences between the three species, but that the size of the lateral, basal, and accessory basal nuclei as well as their connectivity with cortical systems is dramatically more developed in primates [Chareyron et al., 2011]. This increase in connectivity between the amygdala and the neocortex throughout phylogeny might have allowed for the regulation and modulation of more complex and subtle behaviors such as social interactions [Chareyron et al., 2011; Llamas et al., 1977]. Likewise, the fact that electrical stimulation of the amygdala prompts ipsilateral rather than contralateral motor responses [Gloor et al., 1982] suggests that the present ipsilateral connections from the amygdala to motor areas can influence (rather than trigger) complex motor behavior. Together, these findings point to a potential mechanism for the amygdala to influence phylogenetically adapted motor behaviors.

Functional Considerations in Clinical Populations

The present results also raise the interesting possibility that disruption of the amygdala‐motor pathway might contribute to difficulties in initiating or adjusting social behavior during reciprocal interactions. Disorders that impact an individual's ability to accurately detect opportunities for actions that others' social signals evoke [Loveland, 2001] offer relevant models for studying the social functions of the interplay between limbic and motor systems. For example, individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD), characterized by a unique profile of impaired social interaction and communication skills, display “a pervasive lack of responsiveness to others” and “marked impairments in the use of multiple nonverbal behaviors to regulate social interactions” [American Psychiatric Association, 1994]. An fMRI study revealed that atypical processing of emotional expressions in adults with ASD was subtended by a weaker functional connectivity between the amygdala and the premotor cortex [Grèzes et al., 2009]. Similarly, Gotts et al., [2012] showed, using a whole‐brain functional connectivity approach in fMRI, a decoupling between brain regions activated during the evaluation of socially relevant signals and motor‐related circuits in ASDs. These results suggest the possibility that abnormal development of limbic and motor structures and of their connectivity might contribute to difficulties in perceiving social signals as action opportunities that trigger immediate but flexible behavioral response in the observer.

The maturation process of the brain's affective and social systems spans from childhood to adulthood, and social cognitive skills require extensive tuning during development. ASD is a neurodevelopmental disorder that may be linked to the disruption of this subtle brain tuning and could be at the origins of pervasive social skill impairments [Kennedy and Adolphs, 2012]. An important next step will therefore be to investigate the development of the amygdala‐motor pathway. Age‐related changes in amygdala connectivity have already been explored in typical development and have revealed drastic changes in the intrinsic functional connectivity of the basolateral nucleus of the amygdala with the sensorimotor cortex, with weaker integration and segregation of amygdala connectivity in 7–9‐year‐olds compared to 19–22‐year‐olds [Qin et al., 2012]. In addition, Greimel et al. [2012] recently demonstrated that age‐related changes in gray matter volume in the amygdala, temporo‐parietal junction, and premotor cortex differed in ASD compared to typically developing participants.

Beyond ASD, an interaction between the limbic and motor systems has also been implicated in other clinical populations that display impairments in social perception and understanding. For instance, the symptomatology of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), a common neurogenerative motor neuron disorder, includes inappropriate reactions to emotional stimuli [Lulé et al., 2007] and abnormalities in social behavior. A recent fMRI study reported altered connectivity patterns between limbic and motor regions in ALS patients in response to emotional faces when compared to healthy adults. Interestingly, this abnormality was associated with the severity and the duration of the disease [Passamonti et al., 2013]. Moreover, Voon et al. [2011] reported a reduction in activity in motor regions (i.e., SMA) and greater activity in regions associated with emotional processing, including the amygdala, in patients with motor conversion disorder. In another study [Voon et al., 2010] comparing patients with conversion disorder and healthy individuals, increased connectivity between the same two regions was observed. Motor conversion disorder is thought to be associated with a generalized state of heightened arousal, as indicated by an elevated amygdala activity, which in turn disrupts the normal limbic‐motor interactions and, therefore, motor behavior in response to emotional stimuli.

Limitations

It is important to acknowledge that dMRI‐tractography does not allow for a direct visualization of axons and only provides a reconstruction of axonal trajectories. Although dMRI identifies highly reproducible features of the human brain anatomy, this technique remains an indirect measure of white matter tracts. Moreover, because monosynaptic connections between structures cannot be disentangled from polysynaptic connections using dMRI, this technique cannot provide fully conclusive evidence of direct anatomical connections between the amygdala and motor‐related areas. Yet, the present diffusion‐tensor imaging provides evidence that is highly suggestive of the existence of a human equivalent of the anatomical connections described in cats and monkeys between the amygdala and cortical motor‐related areas. Complementary methods and cross‐comparisons between probabilistic tractography and postmortem histological studies in humans would be beneficial to confirm the results reported in this article.

CONCLUSIONS

Using diffusion‐tensor magnetic resonance imaging and probabilistic tractography, we provide the first evidence of a human equivalent of the anatomical connections between the amygdala and cortical motor‐related areas previously described in cats and monkeys. This direct connection might provide a mechanism by which the amygdala can influence more complex and subtle purposive behaviors, beyond the well‐known subcortical influences over automatic and stereotypical emotional behaviors.

Supporting information

Supplementary Information

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Data were provided by the Human Connectome Project, WU‐Minn Consortium (Principal Investigators: David Van Essen and Kamil Ugurbil; 1U54MH091657). The authors wish to warmly thank Michel Thiebaut de Schotten, Benjamin Yerys, and Richard Frackowiak for their useful comments and Natasha Tonge for carefully proofreading this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Adolphs R (2010): Conceptual challenges and directions for social neuroscience. Neuron 65:752–767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aggleton JP, Passingham RE (1981): Syndrome produced by lesions of the amygdala in monkeys (Macaca mulatta). J Comp Physiol Psychol 95:961–977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahs F, Pissiota A, Michelgard A, Frans O, Furmark T, Appel L, Fredrikson M (2009): Disentangling the web of fear: Amygdala reactivity and functional connectivity in spider and snake phobia. Psychiatry Res 172:103–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amaral DG, Price JL (1984): Amygdalo‐cortical projections in the monkey (Macaca fascicularis). J Comp Neurol 230:465–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association (1994): Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders DSM‐IV‐TR, 4th ed Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- Amunts K, Kedo O, Kindler M, Pieperhoff P, Mohlberg H, Shah NJ, Habel U, Schneider F, Zilles K (2005): Cytoarchitectonic mapping of the human amygdala, hippocampal region and entorhinal cortex: Intersubject variability and probability maps. Anat Embryol 210:343–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson J, Xu J, Yacoub E, Auerbach E, Moeller S, Ugurbil K (2012): A comprehensive Gaussian process framework for correcting distortions and movements in diffusion images. Proc Int Soc Magn Reson Med 20:2426. [Google Scholar]

- Andersson JLR, Skare S, Ashburner J (2003): How to correct susceptibility distortions in spin‐echo echo‐planar images: Application to diffusion tensor imaging. NeuroImage 20:870–888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avendano C, Price JL, Amaral DG (1983): Evidence for an amygdaloid projection to premotor cortex but not to motor cortex in the monkey. Brain Res 264:111–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball T, Derix J, Wentlandt J, Wieckhorst B, Speck O, Schulze‐Bonhage A, Mutschler I (2009): Anatomical specificity of functional amygdala imaging of responses to stimuli with positive and negative emotional valence. J Neurosci Methods 180:57–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumgartner T, Matthias W, and Lutz J (2007): Modulation of corticospinal activity by strong emotions evoked by pictures and classical music: A transcranial magnetic stimulation study. Neuroreport 18:261–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbas H (2000): Connections underlying the synthesis of cognition, memory, and emotion in primate prefrontal cortices. Brain Res Bull 52:319–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TEJ Behrens, HJ Berg, S Jbabdi, MFS Rushworth, MW Woolrich (2007): Probabilistic diffusion tractography with multiple fibre orientations: What can we gain? NeuroImage 34:144–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blank H, Anwander A, von Kriegstein K (2011): Direct structural connections between voice‐ and face‐recognition areas. J Neurosci 31:12906–12915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brothers L (1990): The social brain: A project for integrating primate behavior and neurophysiology in a new domain. Concepts Neurosci 1:27–51. [Google Scholar]

- Catani M, Thiebaut de Schotten M (2012): Atlas of Human Brain Connections. New‐York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chareyron LJ, Banta Lavenex P, Amaral DG, Lavenex P (2011): Stereological analysis of the rat and monkey amygdala. J Comp Neurol 519:3218–3239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coelho CM, Lipp OV, Marinovic W, Wallis G, Riek S (2010): Increased corticospinal excitability induced by unpleasant visual stimuli. Neurosci Lett 481:135–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conty L, Dezecache G, Hugueville L, Grèzes J (2012): Early binding of gaze, gesture, and emotion: Neural time course and correlates. J Neurosci 32:4531–4539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coombes SA, Tandonnet C, Fujiyama H, Janelle CM, Cauraugh JH, Summers JJ (2009): Emotion and motor preparation: A transcranial magnetic stimulation study of corticospinal motor tract excitability. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci 9:380–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Gelder B, Snyder J, Greve D, Gerard G, Hadjikhani N (2004): Fear fosters flight: A mechanism for fear contagion when perceiving emotion expressed by a whole body. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101:16701–16706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Destrieux C, Fischl B, Dale A, Halgren E (2010): Automatic parcellation of human cortical gyri and sulci using standard anatomical nomenclature. NeuroImage 53:1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dum RP, Strick PL (2005): Frontal lobe inputs to the digit representations of the motor areas on the lateral surface of the hemisphere. J Neurosci 25:1375–1386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SB Eickhoff, KE Stephan, H Mohlberg, C Grefkes, GR Fink, K Amunts, K Zilles (2005): A new SPM toolbox for combining probabilistic cytoarchitectonic maps and functional imaging data. NeuroImage 25:1325–1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eickhoff SB, Jbabdi S, Caspers S, Laird AR, Fox PT, Zilles K, Behrens TEJ (2010): Anatomical and functional connectivity of cytoarchitectonic areas within the human parietal operculum. J Neurosci 30:6409–6421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emery NJ, Capitanio JP, Mason WA, Machado CJ, Mendoza SP, Amaral DG (2001): The effects of bilateral lesions of the amygdala on dyadic social interactions in rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta). Behav Neurosci 115:515–544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg DA, Moeller S, Smith SM, Auerbach E, Ramanna S, Glasser MF, Miller KL, Ugurbil K, Yacoub E (2010): Multiplexed echo planar imaging for sub‐second whole brain FMRI and fast diffusion imaging. PLoS ONE 5:e15710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghashghaei HT, Hilgetag CC, Barbas H (2007): Sequence of information processing for emotions based on the anatomic dialogue between prefrontal cortex and amygdala. Neuroimage 34:905–923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gloor P, Olivier A, Quesney LF, Andermann F, Horowitz S (1982): The role of the limbic system in experiential phenomena of temporal lobe epilepsy. Ann Neurol 12:129–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goossens L, Kukolja J, Onur OA, Fink GR, Maier W, Griez E, Schruers K, Hurlemann R (2009): Selective processing of social stimuli in the superficial amygdala. Hum Brain Mapp 30:3332–3338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotts SJ, Simmons WK, Milbury LA, Wallace GL, Cox RW, Martin A (2012): Fractionation of social brain circuits in autism spectrum disorders. Brain 135:2711–2725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greimel E, Nehrkorn B, Schulte‐Ruther M, Fink GR, Nickl‐Jockschat T, Herpertz‐Dahlmann B, Konrad K, Eickhoff SB (2012): Changes in grey matter development in autism spectrum disorder. Brain Struct Funct 218:929–942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grèzes J, Wicker B, Berthoz S, de Gelder B (2009): A failure to grasp the affective meaning of actions in autism spectrum disorder subjects. Neuropsychologia 47:1816–1825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grèzes J, Adenis MS, Pouga L, Armony JL (2013): Self‐relevance modulates brain responses to angry body expressions. Cortex 49:2210–2220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groenewegen H, Trimble M (2007): The ventral striatum as an interface between the limbic and motor systems. CNS Spectr 12:887–892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grosbras MH, Paus T (2006): Brain networks involved in viewing angry hands or faces. Cereb Cortex 16:1087–1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajcak G, Molnar C, George M, Bolger K, Koola J, Nahas Z (2007): Emotion facilitates action: A transcranial magnetic stimulation study of motor cortex excitability during picture viewing. Psychophysiology 44:91–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman KL, Gothard KM, Schmid MC, Logothetis NK (2007): Facial‐expression and gaze‐selective responses in the monkey amygdala. Curr Biol 17:766–772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holstege G (1991): Descending motor pathways and the spinal motor system: Limbic and non‐limbic components. Prog Brain Res 87:307–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jbabdi S, Sotiropoulos SN, Savio AM, Grana M, Behrens TEJ (2012): Model‐based analysis of multishell diffusion MR data for tractography: How to get over fitting problems. Magn Reson Med 68:1846–1855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jürgens U (1984): The efferent and afferent connections of the supplementary motor area. Brain Res 300:63–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy DP, Adolphs R (2012): The social brain in psychiatric and neurological disorders. Trends Cogn Sci 16:559–572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llamas A, Avendano C, Reinoso‐Suarez F (1977): Amygdala projections to prefrontal and motor cortex. Science 195:794–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llamas A, Avendano C, Reinoso‐Suarez F (1985): Amygdaloid projections to the motor, premotor and prefrontal areas of the cat's cerebral cortex: A topographical study using retrograde transport of horseradish peroxidase. Neuroscience 15:651–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loveland K (2001): Toward an ecological theory of autism In: Burack CK, Charman T, Yirmiya N, Zelazo PR, editors. The Development of Autism: Perspectives from Theory and Research. New Jersey: Erlbaum Press; pp 17–37. [Google Scholar]

- Lulé D, Diekmann V, Anders S, Kassubek J, Kubler A, Ludolph A, Birbaumer N (2007): Brain responses to emotional stimuli in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). J Neurol 254:519–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macchi G, Bentivoglio M, Rossini P, Tempesta E (1978): The basolateral amygdaloid projections to the neocortex in the cat. Neurosci Lett 9:347–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milchenko M, Marcus D (2013): Obscuring surface anatomy in volumetric imaging data. Neuroinformatics 11:65–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moeller S, Yacoub E, Olman CA, Auerbach E, Strupp J, Harel N, Uğurbil K (2010): Multiband multislice GE‐EPI at 7 tesla, with 16‐fold acceleration using partial parallel imaging with application to high spatial and temporal whole‐brain fMRI. Magn Reson Med 63:1144–1153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mogenson GJ, Jones DL, Yim CY (1980): From motivation to action: Functional interface between the limbic system and the motor system. Prog Neurobiol 14:69–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morecraft RJ, Stilwell‐Morecraft KS, Rossing WR (2004): The motor cortex and facial expression: New insights from neuroscience. Neurologist 10:235–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morecraft RJ, McNeal DW, Stilwell‐Morecraft KS, Gedney M, Ge J, Schroeder CM, van Hoesen GW (2007): Amygdala interconnections with the cingulate motor cortex in the rhesus monkey. J Comp Neurol 500:134–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveri M, Babiloni C, Filippi MM, Caltagirone C, Babiloni F, Cicinelli P, Traversa R, Palmieri MG, Rossini PM (2003): Influence of the supplementary motor area on primary motor cortex excitability during movements triggered by neutral or emotionally unpleasant visual cues. Exp Brain Res 149:214–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passamonti L, Fera F, Tessitore A, Russo A, Cerasa A, Gioia CM, Monsurrò MR, Migliaccio R, Tedeschi G, Quattrone A (2013): Dysfunctions within limbic‐motor networks in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurobiol Aging 34:2499–2509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pichon S, de Gelder B, Grèzes J (2008): Emotional modulation of visual and motor areas by dynamic body expressions of anger. Soc Neurosci 3:199–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pichon S, de Gelder B, Grèzes J (2009): Two different faces of threat. Comparing the neural systems for recognizing fear and anger in dynamic body expressions. NeuroImage 47:1873–1883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pichon S, de Gelder B, Grèzes J (2012): Threat prompts defensive brain responses independently of attentional control. Cereb Cortex 22:274–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin S, Young CB, Supekar K, Uddin LQ, Menon V (2012): Immature integration and segregation of emotion‐related brain circuitry in young children. Proc Natl Acad Sci 109:7941–7946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy AK, Shehzad Z, Margulies DS, Kelly AMC, Uddin LQ, Gotimer K, Biswal BB, Castellanos FX, Milham MP (2009): Functional connectivity of the human amygdala using resting state fMRI. NeuroImage 45:614–626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Setsompop K, Gagoski BA, Polimeni JR, Witzel T, Wedeen VJ, Wald LL (2012): Blipped‐controlled aliasing in parallel imaging for simultaneous multislice echo planar imaging with reduced g‐factor penalty. Magn Reson Med 67:1210–1224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sotiropoulos SN, Moeller S, Jbabdi S, Xu J, Andersson JL, Auerbach EJ, Yacoub E, Feinberg D, Setsompop K, Wald LL, Behrens TEJ, Ugurbil K, Lenglet C (2013): Effects of image reconstruction on fibre orientation mapping from multichannel diffusion MRI: Reducing the noise floor using SENSE. Magn Reson Med 70:1682–1689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sripanidkulchai K, Sripanidkulchai B, Wyss JM (1984): The cortical projection of the basolateral amygdaloid nucleus in the rat: A retrograde fluorescent dye study. J Comp Neurol 229:419–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van den Stock J, Tamietto M, Sorger B, Pichon S, Grèzes J, de Gelder B (2011): Cortico‐subcortical visual, somatosensory, and motor activations for perceiving dynamic whole‐body emotional expressions with and without striate cortex (V1). Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108:16188–16193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Essen DC, Smith SM, Barch DM, Behrens TEJ, Yacoub E, Ugurbil K (2013): The WU‐Minn human connectome project: An overview. NeuroImage 80:62–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Loon AM, van den Wildenberg WPM, van Stegeren AH, Hajcak G, Ridderinkhof KR (2010): Emotional stimuli modulate readiness for action: A transcranial magnetic stimulation study. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci 10:174–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voon V, Brezing C, Gallea C, Ameli R, Roelofs K, LaFrance WC, Hallett M (2010): Emotional stimuli and motor conversion disorder. Brain 133:1526–1536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voon V, Brezing C, Gallea C, Hallett M (2011): Aberrant supplementary motor complex and limbic activity during motor preparation in motor conversion disorder. Mov Disord 26:2396–2403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolrich MW, Jbabdi S, Patenaude B, Chappell M, Makni S, Behrens T, Beckmann C, Jenkinson M, Smith SM (2009): Bayesian analysis of neuroimaging data in FSL. NeuroImage 45:S173–S186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Moeller S, Strupp J, Auerbach E, Feinberg DA, Ugurbil K, Yacoub E (2012): Highly accelerated whole brain imaging using aligned‐blipped‐controlled‐aliasing multiband EPI. Proc Int Soc Magn Reson Med 20:2306. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Information