Abstract

The most important cognitive domains where hippocampal formation is crucially involved are navigation and memory. Some evidence suggests that different hippocampal subregions mediate these domains. However, a quantitative meta‐analysis on neuroimaging studies of spatial navigation versus memory is lacking. By means of activation likelihood estimation (ALE), we investigate concurrence of brain regions activated during spatial navigation encoding and retrieval as well as during episodic memory encoding and retrieval tasks in humans. During encoding in spatial navigation, activity was located in more posterior regions of the hippocampal formation, whereas episodic memory encoding was located in more anterior regions. Retrieval in spatial navigation was more strongly lateralized to the right compared to episodic memory retrieval. Within studies on spatial navigation retrieval, immediate recall was located more posterior and delayed recall more anterior. Overlap between concurrence of activation in spatial navigation and episodic memory was rather limited in comparison to uniquely involved regions. This argues in favor of two distinct networks, one for spatial navigation the other for episodic memory within the hippocampal formation. Hum Brain Mapp 35:1129–1142, 2014. © 2013 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

Keywords: hippocampus, spatial navigation, episodic memory, activation likelihood estimation, meta‐analysis

INTRODUCTION

The hippocampus and its surrounding structures are one of the most researched structures of the brain. However, it is an issue of debate whether the hippocampal system is specialized in spatial information processing or whether it plays a more general role in higher brain function such as memory and learning. Previous research on rodents and monkeys has supported the former view. In recordings of single neurons in freely moving rodents, neurons have been identified that are active predominately when the animal passes through a particular area in space [Derdikman and Moser, 2010; Moser et al., 2008; O'Keefe and Dostrovsky, 1971; Wilson and McNaughton, 2000]. These cells are active both in light and dark, suggesting that a single modality such as vision is not responsible for their positional firing [Quirk et al., 1990]. Consequently, these neurons have been termed place cells and a theory has been developed suggesting that the hippocampus acts as a cognitive map containing a representation of spatial orientation. In line with these findings, a recent fMRI study on humans revealed that place‐related information could be decoded particularly well from the bilateral hippocampi using multivoxel pattern analysis [Hassabis et al., 2009; Rodriguez, 2010aa,b]. Although the cognitive map theory suggests that episodic, but not semantic, memory is mediated by the hippocampus [Burgess et al., 2002; Moscovitch et al., 2006], the cognitive map has not been conceptually restricted to spatial representations. For instance, it has been proposed that relationships among multiple stimuli as well as contingencies and configurations may also be encoded within the hippocampus [Cohen and Eichenbaum, 1991; Eichenbaum and Cohen, 1988].

On the other hand, the famous case study of patient H.M. [Scoville and Milner, 2012] suggests that the hippocampus is of crucial importance for memory formation. More recent observations of patients, who sustained bilateral damage to the hippocampus early in life, indicate that such damage leads to deficits in memory for episodes and events, rather than for semantic material [Vargha‐Khadem et al., 1997]. Episodic memory has been defined as the ability to remember personally experienced episodes in a spatial and temporal context [Tulving, 1998]. How the consolidation of memory is accomplished has been extensively discussed in the literature. It has been debated whether memory storage initially requires hippocampal linking of dispersed neocortical storage sites, but over time this need seems to dissipate, and the hippocampal component is rendered unnecessary [Squire and Alvarez, 2006]. This so‐called standard consolidation theory assumes that as the consolidation process proceeds, the employment of other extrahippocampal structures sustain the permanent memory trace and mediate its retrieval. However, the so‐called multiple trace theory [Nadel and Moscovitch, 1997; Nadel et al., 2000] posits that each and every time information is presented, it is neurally encoded in a unique memory trace and all memory traces incorporated over time are combined into a multiple‐trace representation. In this view, hippocampal ensembles are always involved in storage and retrieval of episodic information, but the semantic gist of information can be established in neocortex without hippocampal contribution.

In rodents, experimental paradigms based on spatial navigation are often used as an operationalization of memory. Whereas in humans, these two lines of experimental research on the role of hippocampus have been pursued more or less independently. However, on a theoretical level, several unifying theories of hippocampal spatial and memory function have been proposed on a conceptually coarse scale. Burgess [2002] supposed that retrieval of information from long‐term storage requires the imposition of a particular viewpoint and therefore harbors spatial processing. Others have emphasized the commonality in the process of self‐projection [Buckner and Carroll, 2007]. In a similar line, it has been suggested that by definition episodic memories include information about time and place and therefore contextual information and scene construction is a necessary prerequisite for episodic memory [Hassabis and Maguire, 2007; Hasselmo et al., 2010; Kentros, 2006; Leutgeb et al., 2005].

Attempts to unite functions associated with activity in hippocampus on a theoretical level stand in contrast to evidence suggesting different localization of episodic memory and spatial navigation within the hippocampal formation. A multi‐electrode recording study in the hippocampus of rats has demonstrated an anatomically separated and highly specialized division of labor between regions that were active during spatial aspects of a task and regions that responded to nonspatial aspects of a task [Hampson et al., 1999]. In humans [Maguire et al., 2000, 2006] as well as in primates [Moser and Moser, 1998] an anterior–posterior distinction (also referred to as rostral‐caudal distinction and equivalent to a ventral‐dorsal distinction in rodents) within the hippocampus has been proposed, with the posterior part being more strongly involved in spatial navigation. Another frequently suggested division of labor across species is the lateralization of hippocampal involvement with navigation dominating in the right and memory in the left hemisphere [Burgess, 2002; Postma et al., 2008]. Likewise, patients with damage to the right temporal lobe frequently exhibit selective deficits in memory of the location of objects while memory of the identity of objects themselves is preserved [Smigh and Milner, 1982].

Within the scope of this study, we set out to systematically test the proposed posterior location and the right hemispheric lateralization of spatial navigation within the hippocampus. To explore the unique and overlapping regions involved in spatial navigation and episodic memory within the hippocampal formation, we conducted a quantitative meta‐analysis on neuroimaging studies in humans. The used activation likelihood estimation (ALE) approach [Eickhoff et al., 2009; Laird et al., 2005; Turkeltaub et al., 2002] enabled the identification of concordance of activated voxels across numerous studies on spatial navigation. It also allowed comparisons to be made with respect to the location of concordance within studies on episodic memory.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Selection of Studies

Studies were selected using a systematic search process. For the episodic memory analyses, we used the coordinate database Brainmap Sleuth (http://brainmap.org/sleuth/index.html) because it contains neuroimaging coordinates classified as memory tasks. We used the search terms [Diagnosis=Normals] AND [Behavioral Domain=Cognition.Memory] OR [Class=Encoding]. Moreover, we excluded studies in which the stimulus material was explicitly spatial or scenic in nature including autobiographical memory. Since, to our knowledge, no database of neuroimaging coordinates contains classification terms such as navigation or spatial memory, we performed a literature search manually. Peer‐reviewed articles published in English until March 2011 were selected from the search results of two separate literature databases (Pubmed, ISI Web of Knowledge). Keyword searches were conducted for the spatial navigation analyses using the following terms: (1) “neuroimaging” <OR> “fMRI” <OR> “PET,” and (2) “spatial navigation” <OR> “navigation” <OR> “route.”

From the resulting papers we selected those that presented contrasts reflecting brain activity during spatial navigation or episodic memory in comparison to a control condition. The reference lists of the selected papers were searched for additional studies that fit these criteria. We included all studies of which we were able to obtain MNI or Talairach coordinates [Talairach and Tournoux, 2011] of contrast. We only included coordinates resulting from analyses computed across the whole brain and not restricted by partial coverage, regions of interest or small volume correction. Because both fMRI and PET have been used to identify the neural correlates of navigation and memory, we included data from studies using either method despite the fact that they have a different physiological basis. Our rationale was to provide an all‐embracing overview of the attempts to identify the neural correlates of spatial navigation and episodic memory. In total a number of 29 spatial navigation studies were included, of which 11 were included in an analysis exploring encoding in spatial navigation. Twenty‐one studies exploring retrieval in spatial navigation were also included. The spatial navigation encoding analysis comprised 185 foci of altogether 237 participants, the spatial navigation retrieval analysis 353 foci of altogether 295 participants (Table 1). In the episodic memory encoding analysis, we included 19 studies comprising 263 foci of 306 participants (Table 2), in the episodic memory retrieval analysis 35 studies with 387 foci of altogether 593 participants were considered (Table 3). In the tables, we refer to “baseline” whenever the contrast was computed as an implicit baseline.

Table 1.

Spatial navigation studies included in the meta‐analysis

| Study | Modality | n | Foci | Contrast | Encoding | Retrieval | Retrieval delay |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Avila et al. [2006] | fMRI | 12 | 11 | Mental navigation to landmarks in hometown > covertly counting numbers | X | Long | |

| Baumann et al. [2010] | fMRI | 17 | 18, 24 | Invisible object in abstract virtual maze as target > visible object as target | X | X | Short |

| Brown et al. [2010] | fMRI | 22 | 19 | Navigation in maze overlapping > non‐overlapping with previously learned virtual maze | X | Short | |

| Ghaem et al. [1997] | PET | 5 | 14 | Mental navigation of a walk learned before > resting condition | X | Short | |

| Hartley et al. [2003] | fMRI | 16 | 8, 1 | Way finding > trail following, memorized route finding > way finding | X | X | Short |

| Iaria et al. [2003] | fMRI | 14 | 17 | Navigation in virtual maze > visible object as target | X | ||

| Iaria et al. [2007] | fMRI | 16 | 16, 9 | Map learning in virtual maze > trail following, Map retrieval in virtual maze > trail following | X | X | Short |

| Iaria et al. [2008] | fMRI | 10 | 19 | Navigation in familiar virtual maze > navigation in familiarization phase | X | Short | |

| Igloi et al. [2010] | fMRI | 19 | 22 | Navigation in virtual maze > trials in environment without landmarks | X | Short | |

| Ino et al. [2002] | fMRI | 16 | 10 | Mental navigation in home town > control task: counting backwards from 3digit number | X | Long | |

| Jordan et al. [2004] | fMRI | 10 | 15 | Navigation in virtual maze > trail following | X | Short | |

| Latini‐Corazzini et al. [2010] | fMRI | 16 | 17 | Snapshot of virtual environment, indicate direction to follow route > decide on orientation of a house relative to body midline | X | Short | |

| Maguire et al. [1997] | PET | 11 | 11 | Mental navigation of taxi drivers in hometown > number repetition | X | Long | |

| Maguire et al. [1998] | PET | 10 | 4 | Navigation in virtual town > trail following | X | Short | |

| Marsh et al. [2010] | fMRI | 25 | 9 | Navigation in virtual maze > trail following | X | ||

| Mayes et al. [2004] | fMRI | 9 | 3 | Personal memory of route episodes > personal memory of static episodes | X | Long | |

| Mellet et al. [2000] | PET | 5 | 11 | Mental navigation from one landmark to the other > resting condition | X | Short | |

| Moffat et al. [2006] | fMRI | 30 | 25 | Navigation in virtual environment > trail following (young participants) | X | ||

| Moffat et al. [2006] | fMRI | 21 | 21 | Navigation in virtual environment > trail following (old participants) | X | ||

| Ohnishi et al. [2006] | fMRI | 56 | 22 | Passive navigation trough virtual maze > passive movement on straight path | X | ||

| Orban et al. [2006] | fMRI | 24 | 47 | Navigation in virtual environment > baseline | X | Short | |

| Pine et al. [2002] | fMRI | 20 | 27 | Navigation in virtual environment > trail following | X | Short | |

| Rauchs et al. [2008] | fMRI | 16 | 28 | Navigation in virtual environment, find alternative way if original is blocked > navigation in the same environment | X | Short | |

| Rodriguez et al. [2010] | fMRI | 11 | 13 | Navigation retrieval in virtual environment > navigation encoding | X | Short | |

| Rosenbaum et al. [2004] | fMRI | 10 | 7 | Mental navigation in virtual environment, find alternative way if original is blocked > judge whether one of two landmarks contains more vowels | X | Long | |

| Shelton et al. [2002] | fMRI | 12 | 18 | Navigation in virtual environment > fixation | X | ||

| Spiers et al. [2006] | fMRI | 20 | 31 | Navigation in virtual hometown and mentally planning routes > not thinking while navigating | X | Long | |

| Weniger et al. [2010] | fMRI | 19 | 17 | Navigation in virtual maze > baseline | X | ||

| Wolbers et al. [2005] | fMRI | 11 | 13 | Navigation in virtual environment > navigation on one straight road with landmarks | X |

Table 2.

Encoding contrasts in non‐spatial memory studies included in the meta‐analysis

| Study | Modality | n | Foci | Stimuli | Contrast |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Achim et al. [2005] | fMRI | 18 | 26 | Animals, objects | Encoding of items and associations > pair of abstract images |

| Beauregard et al. [1998] | PET | 13 | 4 | Words | Subliminal incidental encoding > numbers on screen |

| Braver et al. [2001] | fMRI | 28 | 2 | Words, faces | Encoding > baseline |

| Dannhauser et al. [2008] | fMRI | 10 | 2 | Words | Encoding > reading |

| Dupont et al. [2002] | fMRI | 10 | 17 | Words | Encoding > baseline |

| Halsband et al. [2002] | PET | 10 | 17 | Word pairs | Encoding > nonsense words |

| Halsband [2006] | PET | 7 | 4 | Word pairs | Encoding > nonsense words |

| Ino et al. [2004] | fMRI | 39 | 29 | Word pairs | Encoding > repeating numbers |

| Jager et al. [2007] | fMRI | 40 | 6 | Photos | Associative learning > classification of photos |

| Kapur et al. [1996] | PET | 12 | 5 | Word pairs | Encoding > reading |

| Kelley et al. [1998] | fMRI | 5 | 55 | Words, objects, faces | Encoding > fixation |

| Meltzer et al. [2005] | fMRI | 12 | 5 | Word pairs | Encoding novel > encoding familiar |

| Mottaghy et al. [1999] | fMRI | 6 | 11 | Word pairs | Encoding > nonsense words |

| Neuner et al. [2007] | fMRI | 15 | 15 | Colored shapes | Encoding > fixation |

| Pihlajamäki et al. [2003] | fMRI | 12 | 15 | Animals, objects | Encoding > tracking |

| Ragland et al. [2001] | PET | 23 | 7 | Words | Encoding > finger tapping |

| Savage et al. [2001] | PET | 8 | 6 | Words | Encoding > fixation |

| Sperling et al. [2001] | fMRI | 8 | 15 | Face‐name pairs | Encoding > fixation |

| Sperling et al. [2003] | fMRI | 30 | 22 | Face‐name pairs | Encoding > fixation |

Table 3.

Retrieval contrasts in nonspatial memory studies included in the meta‐analysis

| Study | Modality | n | Foci | Stimuli | Contrast |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Braver et al. [2001] | fMRI | 28 | 1 | Words, faces | Recognition > baseline |

| Buckner et al. [1998] | fMRI | 26 | 53 | Words | Retrieval > fixation |

| Burianova et al. [2007] | fMRI | 12 | 7 | Pictures | Retrieval > scrambled pictures |

| Cabeza et al. [1997] | PET | 24 | 10 | Word pairs | Retrieval > encoding |

| Daselaar et al. [2001] | fMRI | 13 | 9 | Words | Retrieval > baseline |

| Daselaar et al. [2006] | fMRI | 14 | 20 | Words, non‐words | Recollection, familiarity > baseline |

| Dupont et al. [2002] | fMRI | 10 | 30 | Words | Retrieval > fixation |

| Düzel et al. [2001] | PET | 11 | 2 | Words | Retrieval > new words |

| Grady et al. [2001] | PET | 12 | 18 | Words, pictures | Retrieval > new words, pictures |

| Grosbras et al. [2001] | fMRI | 10 | 12 | Eye movement sequences | Retrieval > baseline |

| Halsband et al. [1998] | PET | 13 | 7 | Word pairs | Retrieval > control condition |

| Halsband et al. [2002] | PET | 10 | 6 | Words pairs | Retrieval > control condition |

| Halsband et al. [2006] | PET | 7 | 5 | Word pairs | Retrieval > control condition (Reference II) |

| Heckers et al. [1998] | PET | 8 | 3 | Words | Retrieval > word generation |

| Hofer et al. [2003] | fMRI | 20 | 15 | Words | Retrieval > baseline |

| Jernigan et al. [1998] | PET | 8 | 6 | Words | Retrieval > identification |

| Johnson et al. [2006] | fMRI | 77 | 7 | Pictures | Retrieval > new drawings |

| Kensinger et al. [2007] | fMRI | 19 | 25 | Pictures | Retrieval > baseline |

| Köhler et al. [2000] | PET | 12 | 11 | Pictures, words | Retrieval > encoding |

| Krause et al. [1999] | PET | 12 | 1 | Word pairs | Retrieval > control condition |

| Lepage et al. [2001] | PET | 12 | 9 | Visual and haptic objects | Retrieval > encoding |

| Mensebach et al. [2009] | fMRI | 18 | 12 | Words | Retrieval > baseline |

| Mottaghy et al. [1999] | fMRI | 6 | 10 | Word pairs | Retrieval > control condition (Reference II) |

| Neuner et al. [2007] | fMRI | 15 | 20 | Abstract objects, color, and shape | Retrieval (immediate, delayed) > motor baseline |

| Nyberg et al. [2000] | PET | 11 | 3 | Sentences, pictures | Retrieval > encoding |

| Ongur et al. [2005] | fMRI | 15 | 17 | Abstract picture pairs | Retrieval > baseline |

| Pihlajamaki et al. [2003] | fMRI | 12 | 10 | Picture pairs | Retrieval > tracking |

| Prince et al. [2005] | fMRI | 14 | 10 | Word pairs | Retrieval > encoding |

| Ragland et al. [2001] | PET | 46 | 8 | Words | Retrieval > finger tapping |

| Reber et al. [2002] | fMRI | 10 | 12 | Dot pattern | Retrieval > counting |

| Ries et al. [2006] | fMRI | 14 | 7 | Pictures | Retrieval > new stimuli |

| Sperling et al. [2003] | fMRI | 30 | 13 | Face‐name pairs | Retrieval > fixation |

| Squire et al. [1992] | PET | 18 | 3 | Words | Retrieval > baseline |

| Taylor et al. [1998] | PET | 8 | 2 | Emotional pictures | Retrieval > encoding |

| Wheeler et al. [2000] | fMRI | 18 | 3 | Pictures | Retrieval > fixation |

Creation of ALE Maps

The ALE method provides a voxel‐based meta‐analytic technique for neuroimaging data [Eickhoff et al., 2009; Turkeltaub et al., 2002]. By means of the software Brainmap GingerALE (http://brainmap.org/ale/) statistically significant concordance in the pattern of brain activity among several independent experiments was computed. ALE maps display regions in the brain that comprise statistically significant peak activation locations from multiple studies with a resolution of 2 mm × 2 mm × 2 mm. Coordinates reported in Talairach were converted to MNI using Lancster et al. [2007] (icbm2tal). In the approach taken by ALE, probability distributions for the foci were modeled at the center of 3D Gaussian functions, and the Gaussian distributions were summed across the entire set of experiments to generate a map of interstudy consistencies that estimated the likelihood of activation for each voxel—the ALE statistic. The false discovery rate (FDR) method was used to correct for multiple comparisons at a significance threshold of P < 0.01 and a cluster threshold of 100. Coordinates are reported in MNI space.

Conjunction Analysis

The ALE maps were imported into SPM8 (Wellcome Trust Centre for Neuroimaging, London, UK), to undertake a conjunction analysis to examine the correspondence of consistently activated regions in spatial navigation and episodic memory studies. The conjunction was determined by multiplying the resulting ALE maps. This conjunction does not constitute a statistical test but depicts regions of overlap.

RESULTS

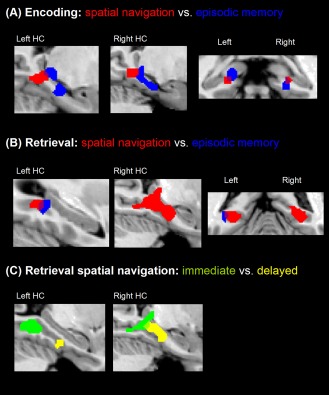

The convergence of all coordinates reported in studies of encoding and retrieval in spatial navigation and episodic memory can be found in Table 4. The main focus of our analysis was the exploration of differential activation within the hippocampal formation in spatial navigation as compared to episodic memory without explicit spatial aspects. Figure 1 depicts the results within this region of interest.

Table 4.

Statistical concurrence observed across studies on spatial navigation and nonspatial memory

| Anatomical region | Brodmann area | Coordinates (MNI) | Volume (mm3) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x | y | z | |||

| (a) Spatial navigation encoding | |||||

| Left precuneus, occipital gyrus | 19/31 | −28 | −80 | 26 | 1280 |

| Right precuneus | 19 | 33 | −75 | 36 | 1168 |

| Posterior cingulate | 30 | −14 | −59 | 7 | 768 |

| Right precuneus | 7 | 18 | −64 | 60 | 592 |

| Left parahippocampus/hippocampus | 30 | −19 | −39 | −6 | 568 |

| Right parahippocampus/hippocampus | 30 | 22 | −39 | −7 | 520 |

| Left precuneus | 7 | −15 | −62 | 59 | 512 |

| Left precentral gyrus | 6 | −29 | −3 | 58 | 400 |

| Pre supplementary motor area | 6 | −7 | 11 | 52 | 128 |

| Left occipital gyrus | 19 | −45 | −83 | 14 | 120 |

| Left lingual gyrus | 18 | −5 | −82 | 0 | 112 |

| (b) Spatial navigation retrieval | |||||

| Right parahippocampal gyrus/hippocampus | 35 | 26 | −35 | −11 | 3432 |

| Left parahippocampal gyrus/hippocampus | 37 | −26 | −47 | −9 | 1944 |

| Left posterior cingulate | 30 | −17 | −53 | 15 | 1632 |

| Left posterior cingulate | 30 | −15 | −59 | 19 | 976 |

| Left occipital gyrus | 19 | −34 | −85 | 26 | 712 |

| Left posterior cingulate | 29 | −9 | −50 | 6 | 480 |

| Right superior frontal gyrus | 6 | 26 | 5 | 56 | 336 |

| Presupplementary motor area | 6 | 8 | 17 | 49 | 304 |

| Left dorsal premotor cortex | 6 | −18 | −2 | 55 | 192 |

| Left lingual gyrus | 18 | −3 | −91 | −6 | 120 |

| (c) Nonspatial memory encoding | |||||

| Presupplementary motor area | 6 | −2 | 13 | 50 | 2424 |

| Left inferior frontal gyrus | 45 | −41 | 27 | 6 | 2064 |

| Left fusiform gyrus | 37 | −42 | −64 | −12 | 1952 |

| Left precentral gyrus | 6 | −44 | 7 | 33 | 1160 |

| Right precentral gyrus | 6 | 44 | 8 | 28 | 1120 |

| Left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex | 9/46 | −41 | 24 | 24 | 1048 |

| Right middle frontal gyrus | 8/9 | 34 | 42 | 36 | 992 |

| Left parahippocampal gyrus/hippocampus | 35 | −19 | −30 | −8 | 976 |

| Left dorsal premotor cortex | 6 | −40 | 2 | 48 | 912 |

| Left occipital gyrus | 18 | −31 | −90 | 10 | 896 |

| Right parahippocampal gyrus/hippocampus | 35 | 21 | −27 | −15 | 880 |

| Right fusiform gyrus | 37 | 40 | −51 | −20 | 744 |

| Left precuneus | 7 | −27 | −63 | 45 | 576 |

| Right insula | 13 | 43 | 28 | 11 | 336 |

| Right cuneus | 17 | 25 | −92 | 8 | 120 |

| Left cerebellum | −44 | −56 | −28 | 112 | |

| (d) Nonspatial memory retrieval | |||||

| Left insula/ inferior frontal gyrus | 13/47 | −32 | 25 | −1 | 1440 |

| Left precuneus | 19/7 | −28 | −63 | 45 | 696 |

| Left cingulate gyrus | 23 | 2 | −25 | 30 | 584 |

| Right insula | 13/47 | 34 | 21 | −9 | 568 |

| Left posterior cingulate | 29 | −4 | −44 | 21 | 464 |

| Left occipital gyrus | 18 | −29 | −92 | 0 | 376 |

| Left cuneus | 19 | −31 | −76 | 36 | 336 |

| Left precentral gyrus | 9 | −40 | 5 | 30 | 328 |

| Left parahippocampal gyrus/hippocampus | 37 | −33 | −41 | −9 | 320 |

| Right cuneus | 18 | 10 | −76 | 34 | 320 |

| Left dorsolateral prefrontal gyrus | 46 | −43 | 20 | 20 | 272 |

| Right posterior cingulate | 30 | 16 | −58 | 17 | 240 |

| Presupplementary motor area | 6 | −5 | 14 | 51 | 232 |

| Left temporo‐parietal junction | 39 | −43 | −67 | 29 | 224 |

| Anterior cingulate gyrus | 32 | 6 | 39 | 16 | 160 |

| Anterior cingulate gyrus | 32 | −1 | 30 | 41 | 136 |

| Medial frontal gyrus | 10 | 23 | 49 | −7 | 104 |

Figure 1.

ALE meta‐analysis maps of (A) the encoding phase in spatial navigation (red) or episodic memory tasks (blue), (B) the retrieval phase in spatial navigation (red) or episodic memory tasks (blue), and (C) immediate (green) or delayed (yellow) retrieval in spatial navigation (P < 0.01, corrected for multiple comparisons). [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

During encoding, the activity in spatial navigation tasks and episodic memory tasks was partly overlapping bilaterally in the posterior (caudal) part of the hippocampus, close to the junction of body and tail of the hippocampus (−18, −34, −5; 22, −34, −7). Spatial navigation related activity extended into the posterior parahippocampal and lingual gyrus, whereas episodic memory related activity extended into the hippocampal body and adjacent parahippocampal gyrus (Fig. 1A).

During retrieval, the conjunction revealed concurrence across studies on spatial navigation and episodic memory, with overlap observed in left parahippocampal gyrus (−32, −43, 11) but not in the right hemisphere. Of note, retrieval processes in the episodic memory tasks showed neither concurrence in right hippocampus nor in right parahippocampal gyrus or neighboring brain regions such as lingual or fusiform gyrus. However, retrieval in spatial navigation showed profound concurrence of activation in right hippocampal body and tail and the adjacent parahippocampal gyrus (Fig. 1B).

When computing separate analyses on PET and fMRI studies within the episodic memory encoding and the retrieval analysis (P < 0.05) significant overlap was observed between fMRI and PET studies on episodic memory encoding. The left parahippocampal/posterior hippocampal cluster in the episodic memory retrieval analysis, on the other hand, was mainly driven by the fMRI studies included.

To explore possible dissociations between immediate and delayed (i.e. retrieval phase took place more than a day after the encoding phase) retrieval in spatial navigation, we computed two separate meta‐analyses. Interestingly, the delay until retrieval revealed an anterior–posterior distinction: immediate retrieval was mainly located in regions in the posterior (caudal) part of bilateral parahippocampal gyrus and right hippocampal tail, whereas delayed retrieval was located in more anterior (rostral) regions of right hippocampal body and the left fusiform gyrus (Fig. 1C).

DISCUSSION

Within the scope of this study, we performed several quantitative meta‐analyses to determine commonalities and differential involvement of the hippocampal formation in the encoding and retrieval phase of spatial navigation in contrast to episodic memory tasks. The key findings of this study are threefold: first, during encoding, activity in spatial navigation tasks was located in more posterior parts (bilaterally close to the junction of body and tail of the hippocampus, extending into posterior parahippocampal and lingual gyrus) compared to episodic memory task activation that was located in more anterior parts within the hippocampal formation (hippocampal body and adjacent parahippocampal gyrus). Second, during the retrieval phase, activity in spatial navigation tasks was strongly lateralized to the right hippocampal formation (right hippocampal body and tail and the adjacent parahippocampal gyrus), whereas episodic memory task‐related activity was restricted to the left hemisphere. Third, when dividing the studies on the retrieval phase of spatial navigation into those with immediate retrieval and those with delayed retrieval (more than a day after encoding), an anterior‐posterior distinction was observed. Delayed retrieval relied more strongly on anterior (right hippocampal body and adjacent bilateral parahippocampal gyrus) and immediate retrieval relied more on posterior regions of the hippocampal formation (right hippocampal tail and adjacent bilateral parahippocampal gyrus).

The presented findings on encoding are in line with previous suggestions that spatial navigation is located in more posterior portions of the hippocampus in humans [Maguire et al., 2000, 2006] as well as in primates [Moser and Moser, 1998].

A model conceptualizing the anatomical connectivity of substructures within the hippocampal formation has been derived from evidence across different species [Eichenbaum and Lipton, 2008; Witter et al., 1993]. Basically, it comprises a continuation of the well‐known distinction of a ventral “what” and a dorsal “where” visual pathway [Mishkin and Ungerleider, 1982]. It assumes that the perirhinal cortex receives more input from areas along the ventral visual pathway that are considered important for object recognition, whereas the parahippocampal cortex receives input from areas of the dorsal visual stream considered important for spatial processing. Furthermore in rats and monkeys, the perirhinal cortex tends to project more strongly to the lateral enthorinal area and this in turn to the CA3 hippocampus subfield. In contrast, the parahippocampal or postrhinal cortex tends to project to the medial enthorinal area and in turn to the CA1 subfield of the hippocampus proper [Witter et al., 1993]. Functional imaging studies on humans revealed dissociations of activation in line with this two‐stream account. In one study, changes of the identity of objects activated the perirhinal cortex, whereas changes in the spatial arrangement of objects activated the parahippocampal cortex [Pihlajamäki et al., 2003]. Likewise, another study showed that merely the instruction to remember the object or the place of visually presented objects could alone differentially activate perirhinal or parahippocampal cortex [Buffalo et al., 2006]. Since the current meta‐analysis was based on fMRI and PET data, methods that rely heavily on smoothing, and additional smoothing within the ALE analysis we should not overestimate the resolution and precision of the localization of our results. However, the proposed division of the two‐stream account into the more anterior perirhinal cortex concerned with object recognition and the more posterior parahippocampal cortex concerned with spatial processing is in accordance with our anterior–posterior division of concurrence in studies on the encoding phase of episodic memory (anterior) as opposed to spatial navigation tasks (posterior).

The observed lateralization of hippocampal activation in spatial navigation during retrieval corroborates previous notions of right hemispheric dominance [Burgess, 2002; Postma et al., 2008] and substantiates it by showing significant concurrence across a broad range of studies. This finding is in accordance with studies on patients with posterior cerebral artery strokes that lead to problems with navigation (orienting) particularly when the right hemisphere was affected [Barrash et al., 2000]. Similar patterns of rightward lateralizations in navigation have been reported in rodents [Klur et al., 2009] and avians [Kahn and Bingman, 2004]. A recent article using pattern classification during an object–location incidental learning paradigm showed best classification rates within the right hippocampus [Manelis et al., 2012]. Furthermore, the findings are in line with a recent paper showing that the dorsal hippocampus (posterior in humans) is sufficient to form memory traces of spatial information, but that both dorsal and ventral hippocampus contribute to the retrieval of spatial information in rats [Loureiro et al., 2012]. Albeit in our present findings on retrieval, only an extended area within the hippocampal body and tail was activated, but not the head of the hippocampus.

In the included studies on retrieval in episodic memory, we found no convergence within the hippocampus proper, only in left parahippocampal gyrus. This absence of hippocampal involvement can be interpreted in support of the standard consolidation theory [Squire and Alvarez, 2006], assuming that other extrahippocampal structures suffice to mediate retrieval. In contrast, the multiple trace theory [Nadel and Moscovitch, 1997; Nadel et al., 2000] would have predicted hippocampal involvement during retrieval of episodic information, which we did not observe within the present meta‐analysis.

The observation that spatial navigation retrieval is located more medially in parahippocampal gyrus, whereas the episodic memory retrieval is located in a more lateral region is in accordance with a finding recently reported by Schultz et al. (2012). They found a distinction between spatial and non‐spatial content in a working memory paradigm during retrieval after distraction showing activation in the parahippocampal medial enthorinal pathway for scenes and in the parahippocampal lateral enthorinal pathway for faces.

Previous studies exploring the delay effect in retrieval processes have shown that activity in bilateral hippocampus increases with increasing time until retrieval [Huijbers et al., 2010; Talmi et al., 1988]. Brozinsky et al. (2005) reported increases in bilateral posterior hippocampus and anterior parahippocampus. This finding is not entirely in line with our observation that immediate retrieval is located in more posterior (tail) regions, and delayed retrieval is found in more anterior regions (body) of the hippocampal formation. However, the cluster of concordance of delayed retrieval studies in spatial navigation is indeed located in hippocampus proper, whereas the cluster of immediate retrieval extends into the parahippocampal gyrus. It is important to note that these previous studies focused on delays of up to 2 min, whereas the delayed condition in our meta‐analysis includes studies using delays of over 24 h making a direct comparison difficult.

It is difficult to relate the spatial dissociations observed in the present meta‐analysis to high‐resolution imaging studies investigating activity within hippocampal subfields, because the resolution of standard fMRI studies is low and summarizing activity across studies further enhances blurring. However, we would like to mention that the subfields CA1, CA3, and dentate gyrus have been suggested to support encoding of non‐spatial [Eldridge et al., 2005; Zeineh et al., 2003] as well as spatial associations [Suthana et al., 1992], whereas the subicular cortex has been shown to support retrieval of learned spatial [Suthana et al., 1992] as well as nonspatial associations [Eldridge et al., 2005; Zeineh et al., 2003]. Within the present meta‐analysis we mainly detected dissociations on the level of lateralization or between anterior and posterior portions of the hippocampal formation, whereas hippocampal subfields provide a more fine‐grained discrimination on coronal slices of the hippocampus. Future meta‐analyses should attempt to summarize information across high‐resolution studies that discriminate between hippocampal subfields in order to investigate whether similar dissociations can be observed.

Overall, the results of the present meta‐analyses are consistent with what has been reported about the organization of hippocampal connectivity and anatomy in the previous literature. Within the animal hippocampus literature, which has generally been accepted as consistent across rats, cats, monkeys and humans [Burwell, 2000] CA1 in the tail of hippocampus has been shown to contain a high density and selectivity of place cells coding spatial location [Jung et al., 1994; Muller et al., 1996]. Furthermore, the subicular complex, at the posterior end of the hippocampus, contains most so‐called head direction cells coding head position in space [Taube et al., 2007]. This is in line with our finding that encoding processes in spatial navigation tasks activate the hippocampal tail. Similarly the connectivity patterns of the body and the tail of hippocampus have been shown to differ, suggesting a division within the functional domain [Risold and Swanson, 1997]. Furthermore, the posterior (dorsal) CA1 as well as the dorsal parts of the subicular complex have prominent cortical projections to retrosplenial and anterior cingulate cortices in rats [Cenquizca and Swanson, 2007]. These cortical regions are involved in spatial navigation in rats [Harker and Whishaw, 2004] as well as in humans [Spiers and Maguire, 2003].

There is substantial data supporting that the posterior part of the hippocampus, namely body and tail, are involved in cognitive processing such as memory and navigation, whereas the anterior portion (namely the head) of the hippocampus modulates affective processing [Bannerman et al., 2004; Fanselow and Dong, 2010] in particular of fear and anxiety [Gray and McNaughton, 2000]. This functional subdivision is supported by an anatomical linkage between the amygdala and the head of the hippocampus [Kishi et al., 2006; Pitkanen et al., 2000]. The adjacent parahippocampal gyrus shows a similar functional subdivision [LaBar and Cabeza, 2006]. Within this study we did not find any concurrence within the head of hippocampus. This is on non‐spatial memory in line with the fact that the included studies on memory and spatial navigation did not aim at eliciting emotions.

LIMITATIONS

Although the results presented show considerable differences between brain activity associated with spatial and nonspatial memory within the hippocampal formation, one has to acknowledge that the studies included in the present meta‐analysis are heterogeneous in nature. In particular, the retrieval part of the studies included varies between overt and covert recollection as well as between familiarity and recollection judgments. Future meta‐analyses should attempt to match retrieval processes across the different retrieval domains when a sufficient number of respective studies are published.

Although the present studies are heterogeneous in nature many studies on episodic memory and spatial navigation that did not use subtraction methods, but correlations or pattern classification were not included in the present meta‐analysis. This selection may have potentially biased the results.

Another limitation might be seen in the direct comparison of encoding and retrieval phase that is confounded by factors such as novelty effects that are exclusively associated with the encoding phase and familiarity effects associated with the retrieval phase. However, the main focus of this study was the comparison between spatial navigation and episodic memory related activation in hippocampal formation. When comparing encoding or retrieval phase across domains the confounding factors are present in both.

CONCLUSION

Taken together, although there are multiple accounts that propose a unifying coarse‐scale theoretical framework of hippocampal involvement in spatial navigation and episodic memory, the neural correlates identified within the current quantitative meta‐analysis show considerable regional disparity. Encoding in spatial navigation uses more posterior regions of the hippocampal formation, whereas episodic memory encoding utilizes more anterior regions. Furthermore, spatial navigation retrieval is more strongly lateralized to the right hippocampal formation compared to episodic memory retrieval. Within spatial navigation retrieval, immediate recall requires more posterior regions of the hippocampal formation, while delayed recall is located more anterior. To summarize, the overlap of concurrence within the hippocampal formation is rather limited. This could be interpreted as arguing against unifying accounts of hippocampal function in spatial navigation and episodic memory.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

SK is a Postdoctoral Fellow of the Research Foundation Flanders (FWO). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Achim AM, Lepage M (2005): Neural correlates of memory for items and associations: An event‐related functional magnetic resonance imaging study. J Cogn Neurosci 17:652–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avila C, Barros‐Loscertales A, Forn C, Mallo R, Parcet M‐A, Belloch V, Campos S, Feliu‐Tatay R, Gonzalez‐Darder JM (2006): Memory lateralization with 2 functional MR imaging tasks in patients with lesions in the temporal lobe. Am J Neuroradiol 27:498–593. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bannerman DM, Rawlins JNP, McHugh SB, Deacon RMJ, Yee BK, Bast R, Zhang W‐N, Pothuizen HHJ, Feldon J (2004): Regional dissociations within the hippocampus—Memory and anxiety. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 28:273–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrash J, Damasio H, Adolphs R, Tranel D (2000): The neuroanatomical correlates of route learning impairment. Neuropsychologia 38:820–836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann O, Chan E, Mattingley JB (2010): Dissociable neural circuits for encoding and retrieval of object locations during active navigation in humans. NeuroImage 49:2816–2825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauregard M, Gold D, Evans AC, Chertkow H (1998): A role for the hippocampal formation in implicit memory: A 3D PET study. NeuroReport 9:1867–1873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braver TS, Barch DM, Kelley WM, Buckner RL, Cohen NJ, Miezin FM, Snyder AZ, Ollinger JM, Akbudak E, Conturo TE, Petersen SE. (2001): Direct comparison of prefrontal cortex regions engaged by working and long‐term memory tasks. NeuroImage 14:48–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TI, Ross RS, Keller JB, Hasselmo ME, Stern CE (2010): Which way was I going? Contextual retrieval supports the disambiguation of well‐learned overlapping navigational routes. J Neurosci 30:7414–7422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brozinsky CJ, Yonelinas AP, Kroll NEA, Ranganath C (2005): Lag‐sensitive repetition suppression effects in the anterior parahippocampal gyrus. Hippocampus 15:557–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner RL, Carroll DC (2007): Self‐projection and the brain. Trends Cogn Sci 11:49–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner RL, Koutstaal W, Schacter DL, Wagner AD, Rosen BR (1998): Functional‐anatomic study of episodic retrieval using fMRI. Retrieval effort versus retrieval success. NeuroImage 7:151–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buffalo EA, Bellgowan PSF, Martin A (2006): Distinct roles for medial temporal lobe structures in memory for objects and their locations. Learn Mem 13:638–643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess N (2002): The hippocampus, space, and viewpoints in episodic memory. Quart J Exp Psychol 55:1057–1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess N, Maguire EA, O'Keefe J (2002): The human hippocampus and spatial and episodic memory. Neuron 35:625–641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burianova H, Grady CL (2007): Common and unique neural activations in autobiographical, episodic and semantic retrieval. J Cogn Neurosci 19:1520–1534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burwell RD (2000): The parahippocampal region: Corticocortical connectivity. Ann N Y Acad Sci 911:25–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabeza R, McIntosh AR, Tulving E, Nyberg L, Grady CL (1997): Age‐related differences in effective neural connectivity during encoding and recall. NeuroReport 8:3479–3483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cairo TA, Liddle PF, Woodward TS, Ngan ETC (2004): The influence of working memory load on phase specific patterns of cortical activity. Cogn Brain Res 21:377–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cenquizca LA, Swanson LW (2007): Spatial organization of direct hippocampal field CA1 axonal projections to the rest of the cerebral cortex. Brain Res Rev 56:1–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen NJ, Eichenbaum H (1991): The theor that wouldn't die: A critical look at the spatial mapping theory of hippocampal function. Hippocampus 3:265–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dannhauser TM, Shergill SS, Stevens T, Lee L, Seal M, Walker RWH, Walker Z. (2008): An fMRI study of verbal episodic memory encoding in amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Cortex 44:869–880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derdikman D, Moser EI (2010): A manifold of spatial maps in the brain. Trends Cogn Sci 14:561–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deselaar SM, Fleck MS, Cabeza R (2006): Triple dissociation in the medial temporal lobes: Recollection, familiarity, and novelty. J Neurophysiol 96:1902–1911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deselaar SM, Rombouts SARB, Veltman DJ, Raaijmakers JGW, Lazeron RHC, Jonker C (2001): Parahippocampal activation during successful recognition of words: A self‐paced event‐related fMRI study. NeuroImage 13:1113–1120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupont S, Samson Y, Le Bihan, Baulac M (2002): Anatomy of verbal memory: A functional MRI study. Surg Radiol Anat 24:57–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Düzel E, Picton TW, Cabeza R, Yonelinas AP, Scheich H, Heinze H‐J, Tulving E. (2001): Comparative electrophysiological and hemodynamic measures of neural activation during memory‐retrieval. Hum Brain Mapp 13:104–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichenbaum H, Cohen NJ (1988): Representation in the hippocampus:What do hippocampal neurons code? Trends Neurosci 11:244–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichenbaum H, Lipton PA (2008): Towards a functional organization of the medial temporal lobe memory system: Role of the parahippocampal and medial enthorinal cortical areas. Hippocampus 18:1314–1324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eickhoff SB, Laird AR, Grefkes C, Wang LE, Zilles K, Fox PT (2009): Coordinate‐based activation likelihood estimation meta‐analysis of neuroimaging data: A random effects approach based on empirical estimates of spatial uncertainty. Hum Brain Mapp 30:2907–2926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eldridge LL, Engel SA, Zeineh MM, Bookheimer SY, Knowlton BJ (2005): A dissociation of encoding and retrieval processes in the human hippocampus. J Neurosci 25:3280–3286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fanselow MS, Dong H‐W (2010):Are the dorsal and ventral hippocampus functionally distinct structures? Neuron 6 5:7–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghaem O, Mellet E, Crivello F, Tzourio N, Mazoyer B, Berthoz A, Denis M. (1997): Mental navigation along memorized routes activates the hippocampus, precuneus and insula. NeuroReport 8:739–744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grady CL, McIntosh AR, Beig S, Craig FIM (2001): An examination of the effects of stimulus type, encoding task, and functional connectivity on the role of right prefrontal cortex in recognition memory. NeuroImage 14:556–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray JA, McNaughton N (2000):The Neuropsychology of Anxiety: An Enquiry into the Functions of the Septo‐hippocampal System. Oxford:Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Grosbras M‐H, Leonards U, Lobel E, Poline J‐B, LeBihan D, Berthoz A (2001): Human cortical networks for new and familiar sequences of saccades. Cerebral Cortex 11:936–945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halsband U (2006): Learning in trance: Functional brain imaging studies and neuropsychology. J Physiol 99:470–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halsband U, Krause BJ, Schmidt D, Herzog H, Tellmann L, Müller‐Gärtner H‐W (1998): Encoding and retrieval in declarative learning: A positron emission tomography study. Behav Brain Res 97:69–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halsband U, Krause BJ, Sipilä H, Teräs M, Laihinen A (2002): PET studies on the memory processing of word pairs in bilingual Finnish–English subjects. Behav Brain Res 132:47–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampson R, Simeral J, Deadwyler S (1999): Spatial and nonspatial information in the dorsal hippocampus. Nature 402:610–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harker KT, Whishaw IQ (2004): Impaired place navigation in place and matching‐to‐place swimming pool tasks follows both retrosplenial cortex lesions and cingulum bundle lesions in rats. Hippocampus 14:224–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartley T, Maguire EA, Spiers HJ, Burgess N (2003): The well‐worn route and the path less travelled: Distinct neural bases of route following and wayfinding in humans. Neuron 37:877–888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassabis D, Maguire EA (2007): Deconstructing episodic memory with construction. Trends Cogn Sci 11:299–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassabis D, Chu C, Rees G, Weiskopf N, Molyneux PD, Maguire EA (2009): Decoding neuronal essembles in the human hippocampus. Curr Biol 19:546–554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasselmo ME, Giocomo LM, Brandon MP, Yoshida M (2010): Cellular dynamical mechanisms for encoding the time and place of events along spatiotemporal trajectories in episodic memory. Behav Brain Res 215:261–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckers S, Rauch SL, Goff D, Savage CR, Schacter DL, Fischman AJ, et al. (1998): Impaired recruitment of the hippocampus during conscious recollection in schizophrenia. Nature Neurosci 1:318–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofer A, Weiss EM, Golaszewski SM, Seidentopf CM, Brinkhoff C, Kremser C, Felber S, Fleischhacker WW. (2003): An fMRI study of episodic encoding and recognition of words in patients with schizophrenia in remission. Am J Psychiatry 160:911–918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huijbers W, Pennartz CMA, Daselaar SM (2010): Dissociating the “retrieval success” regions of the brain: Effects of retrieval delay. Neuropsychologia 48:491–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iaria G, Chen J‐K, Guariglia C, Ptito A, Petrides M (2007): Retrosplenial and hippocampal brain regions in human navigation: Complementary functional contributions to the formation and use of cognitive maps. Eur J Neurosci 25:890–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iaria G, Fox CJ, Chen J‐K, Petrides M, Barton JJS (2008): Detection of unexpected events during spatial navigation in humans: Bottom‐up attentional system and neural mechanisms. Eur J Neurosci 27:1017–1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iaria G, Petrides M, Dagher A, Pike B, Bohbot VD (2003): Cognitive strategies dependent on the hippocampus and caudate nucleus in human navigation: variability and change with practice. J Neurosci 23:5945–5952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igloi K, Doeller CF, Berhoz A, Rondi‐Reig L, Burgess N (2010): Lateralized human hippocampal activity predicts navigation based on sequence of place memory. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107:14466–14471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ino T, Inoue Y, Kage M, Hirose S, Kimura T, Fukuyama H (2002): Mental navigation in humans is processes in the anterior bank of the parieto‐occipital sulcus. Neurosci Lett 322:182–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ino T, Doi T, Kumura T, Ito J, Fukuyama H (2004): Neural substrates of the performance of an auditory verbal memory: Between‐subjects analysis by fMRI. Brain Res Bull 64:115–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jager G, Van Hell HH, De Win MML, Kahn RS, Van den Brink W, Van Ree JM, Ramsey NF. (2007): Effects of frequent cannabis use on hippocampal activity during an associative memory task. Eur Neuropsychopharmacology 17:289–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jernigan TL. Ostergaard AL, Law I, Svarer C, Gerlach C, Paulson OB (1998): Brain activation during word identification and word recognition. NeuroImage 8:93–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SC, Schmitz TW, Moritz CH, Meyerand ME, Rowley HA, Alexander AL, Hansen KW, Gleason CE, Carlsson CM, Ries ML, Asthana S, Chen K, Reiman EM, Alexander GE. (1998): Activation of brain regions vulnerable to Alzheimer's disease: The effect of mild cognitive impairment. Neurobiol Aging 27:1604–1612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan K, Schadow J, Wüstenberg T, Heinze H‐J, Jäncke L (2004): Different cortical activations for subjects using allocentric or egocentric strategies in a virtual navigation task. NeuroReport 15:135–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung MW, Wiener SI, McNaughton BL (1994): Comparison of spatial firing characteristics of units in dorsal and ventral hippocampus of the rat. J Neurosci 14:7347–7356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn MC, Bingman VP (2004): Lateralization of spatial learning in the avian hippocampal formation. Behav Neurosci 118:333–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapur S, Tulving E, Cabeza R, McIntosh AR, Houle S, Craik FIM (1996): The neural correlates of intentional learning of verbal materials: A PET study in humans. Cogn Brain Res 4:243–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley WM, Miezin FM, McDermott KB, Buckner RL, Raichle ME, Cohen NJ, Ollinger JM, Akbudak E, Conturo TE, Snyder AZ, Petersen SE. (1998): Hemispheric specialization in human dorsal frontal cortex and medial temporal lobe for verbal and nonverbal memory encoding. Neuron 20:927–936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kensinger EA, Schacter DL (2007): Remembering the specific visual details of presented objects: Neuroimaging evidence for effects of emotion. Neuropsychologia 45:2951–2962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kentros C (2006): Hippocampal place cells:The “where” of episodic memory? Hippocampus 16:743–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishi T, Tsumori T, Yokota S, Yasui Y (2006): Topographical projection from the hippocampal formation to the amygdala: A combined anterograde and retrograde tracing study in the rat. J Comp Neurol 496:349–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klur S, Muller C, Pereira de Vasconcelos A, Ballard T, Lopez J, Galani R, Certa U, Cassel JC. (2009). Hippocampal‐dependent spatial memory functions might be lateralized in rats: An approach combining gene expression profiling and reversible inactivation. Hippocampus 19:800–816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Köhler S, Moscovitch M, Winocur G, McIntosh AR (2000): Episodic encoding and recognition of pictures and words: Role of the human medial temporal lobes. Acta Psychologia 105:159–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause BJ, Schmidt D, Mottaghy FM, Taylor J, Halsband U, Herzog H, Tellmann L, Müller‐Gärtner HW. (1999): Episodic retrieval activates the precuneus irrespective of the imagery content of word pair associates. A PET study. Brain 122:255–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBar KS, Cabeza R (2006): Cognitive neuroscience of emotional memory. Nature Neurosci Rev 7:54–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagopoulos J, Ivanovski B, Malhi GS (2007): An event‐related functional MRI study of working memory in euthymic bipolar disorder. J Psychiatry Neurosci 32:174–184. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laird AR, Fox PM, Price CJ, Glahn DC, Uecker AM, Lancaster JL, Turkeltaub PE, Kochunov P, Fox PT. (2005): ALE meta‐analysis: Controlling the false discovery rate and performing statistical contrasts. Hum Brain Mapp 25:155–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lancaster JL, Tordesillas‐Guiérrez D, Martinez M, Salinas F, Evans A, Zilles K, Mazziotta JC, Fox PT. (2007): Bias between MNI and Talairach coordinates analyzed using the ICBM‐152 brain template. Hum Brain Mapp 28:1194–1205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landau SM, Schumacher EH, Garavan H, Druzgal TJ, D'Esposito M (2004): A functional MRI study of the influence of practice on component processes of working memory. NeuroImage 22:211–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latini‐Corazzini L, Nesa MP, Ceccaldi M, Guedj E, Thinus‐Blanc C, Cauda F, Dagata F, Péruch P. (2010): Route and survey processing of topographical memory during navigation. Psychol Res 74:545–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepage M, McIntosh AR, Tulving E (2001): Transperceptual encoding and retrieval processes in memory: A PET study of visual and haptic objects. NeuroImage 14:572–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leutgeb S, Leutgeb JK, Moser M‐B, Moser EI (2005): Place cells, spatial maps and the population code for memory. Curr Opin Neurobiol 15:738–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linden DEJ, Bittner RA, Muckli L, Waltz JA, Kriegeskorte N, Goebel R, Singer W, Munk MH. (2003): Cortical capacity constraints for visual working memory: Dissociation of fMRI load effects in a fronto‐parietal network. NeuroImage 20:1518–1530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loureiro M, Lecourtier L, Engeln M, Lopez J, Consquer B, Geiger K, Kelche C, Cassel JC, Pereira de Vasconcelos A. (2012): The ventral hippocampus is necessary for expressing a spatial memory. Brain Struct Funct 217:93–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguire EA, Frackowiak RSJ, Frith CD (1997): Recalling routes around London: Activation of the right hippocampus in taxi drivers. J Neurosci 17:7103–7110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguire EA, Burgess N, Donnett JG, Frackowiak RSJ, Frith CD, O'Keefe J (1998): Knowing where and getting there: A human navigation network. Science 280:920–924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguire EA, Gadian DG, Johnsrude IS, Good CD, Ashburner J, Frackowiak RS, Frith CD. (2000): Navigation‐related structural change in the hippocampi of taxi drivers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97:4398–4403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguire EA, Woollett K, Spiers HJ (2006): London taxi drivers and bus drivers: A structural MRI and neuropsychological analysis. Hippocampus 16:1091–1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manelis A, Reder LM, Hanson SJ (2012): Dynamic changes in the medial temporal lobe during incidental learning of object‐location associations. Cereb Cortex 22:828–837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh R, Hao X, Xu D, Wang Z, Duan Y, Liu J, Kangarlu A, Martinez D, Garcia F, Tau GZ, Yu S, Packard MG, Peterson BS. (2010): A virtual reality‐based fMRI study of reward‐based spatial learning. Neuropsychologia 48:2912–2921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayes AR, Montaldi D, Spencer TJ, Roberts N (2004): Recalling spatial information as a component of recently and remotely acquired episodic or semantic memories: An fMRI study. Neuropsychology 18:426–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellet E, Bricogne S, Tzourio‐Mazoyer N, Ghaem O, Petit L, Zago L, Etard O, Berthoz A, Mazoyer B, Denis M. (2000): Neural correlates of topographic mental exploration: The impact of route versus survey perspective learning. NeuroImage 12:588–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meltzer JA, Constable RT (2005): Activation of human hippocampal formation reflects success in both encoding and cued recall of paired associates. NeuroImage 24:384–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mensebach C, Beblo T, Driessen M, Wingenfeld K, Mertens M, Rullkoetter N, Lange W, Markowitsch HJ, Ollech I, Saveedra AS, Rau H, Woermann FG. (2009): Neural correlates of episodic and semantic memory retrieval in borderline personality disorder: An fMRI study. Psychiatry Res Neuroimaging 171:94–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishkin M, Ungerleider LG (1982): Contribution of striate inputs to the visuospatial functions of parieto‐preoccipital cortex in monkeys. Behav Brain Res 6:57–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffat SD, Elkins W, Resnick SM (2006): Age differences in the neural systems supporting human allocentric spatial navigation. Neurobiol Aging 27:965–972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moscovitch M, Nadel L, Winocur G, Gilboa A, Rosenbaum RS (2006): The cognitive neuroscience of remote episodic, semantic and spatial memory. Curr Opin Neurobiol 16:179–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moser EI, Kropff E, Moser M‐B (2008): Place cells, grid cells, and the brain's spatial representation system. Annu Rev Neurosci 31:69–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moser M‐B, Moser EI (1998): Functional differentiation in the hippocampus. Hippocampus 8:608–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mottaghy FM, Shah NJ, Krause BJ, Schmidt D, Halsband U, Jäncke L, Müller‐Gärtner HW. (1999): Neuronal correlates of encoding and retrieval in episodic memory during a paired‐word association learning task: A functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Exp Brain Res 128:332–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller RU, Stead M, Pach J (1996): The hippocampus as a cognitive graph. J Gen Physiol 107:663–694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadel L, Moscovitch M (1997): Memory consolidation, retrograde amnesia and the hippocampal complex. Curr Opin Neurobiol 7:217–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadel L, Samsonovich A, Ryan L, Moscovitch M (2000): Multiple trace theory of human memory: Computational, neuroimaging, and neuropsychological results. Hippocampus 10:352–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuner I, Stöcker T, Kellermann T, Kircher T, Zilles K, Schneider F, Shah NJ. (2007): Wechsler memory scale revised edition: Neural correlates of the visual paired associates subtest adapted for fMRI. Brain Res 1177:66–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyberg L, Persson J, Habib98 R, Tulving E, McIntosh AR, Cabeza R, Houle S. (2000): Large sale neurocognitive networks underlying episodic memory. J Cogn Neurosci 12:163–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Keefe J, Dostrovsky J (1971): The hippocampus as a spatial map, preliminary evidence from unit activity in the freely‐moving rat. Brain Res 34:171–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohnishi T, Matsuda H, Hirakata M, Ugawa Y (2006): Navigation ability dependent neural activation in the human brain: An fMRI study. Neurosci Res 55:361–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Öngür D, Zalesak M, Weiss AP, Ditman T, Titone D, Heckers S (2005): Hippocampal activation during processing of previously seen visual stimulus pairs. Psychiatry Res Neuroimaging 139:191–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orban P, Rauchs G, Balteau E, Degueldre C, Luxen A, Maquet P, Peigneux P. (2006): Sleep after spatial learning promotes covert reorganization of brain activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103:7124–7129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pihlajamäki M, Tanila H, Hänninen T, Könönen M, Mikkonen M, Jalkanen V, Partanen K, Aronen HJ, Soininen H. (2003): Encoding of novel picture pairs activates the perirhinal cortex: An fMRI study. Hippocampus 13:67–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pine DS, Grun J, Maguire EA, Burgess N, Zarahn E, Koda V, Fyer A, Szeszko PR, Bilder RM. (2002): Neurodevelopmental aspects of spatial navigation: A virtual reality fMRI study. NeuroImage 15:396–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitkanen A, Pikkarainen M, Nurminen N, Ylinen A (2000): Reciprocal connections between the amygdala and the hippocampal formation, perirhinal cortex, and postrhinal cortex in rat. A review. Ann N Y Acad Sci 911:369–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Postma A, Kessels FPC, van Asselen M (2008): How the brain remembers and forgets where things are: The neurocognition of object‐location memory. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 32:1339–1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prince SE, Daselaar SM, Cabeza R (2005): Neural correlates of relational memory: Successful encoding and retrieval of semantic and perceptual associations. J Neurosci 25:1203–1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quirk GJ, Muller RU, Kubie JL (1990): The firing of hippocampal place cells in the dark depends on the rats recent experience. J Neurosci 10:2008–2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ragland JD, Gur RC, Raz J, Schroeder L, Kohler CG, Smith RJ, Alavi A, Gur RE. (2001): Effect of schizophrenia on frontotemporal activity during word encoding and recognition: A PET cerebral blood flow study. Am J Psychiatry 158:1114–1125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauchs G, Orban P, Balteau E, Schmidt C, Degueldre C, Luxen A, Maquet P, Peigneux P. (2008): Partially segregated neural networks for spatial and contextual memory in virtual navigation. Hippocampus 18:503–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reber PJ, Wong EC, Buxton RB (2002): Comparing the brain areas supporting nondeclarative categorization and recognition memory. Cogn Brain Res 14:245–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ries ML, Schmitz TW, Kawahara‐Baccus TN, Torgerson BM, Trivedi MA, Johnson SC. (2006): Task‐dependent posterior cingulate activation in mild cognitive impairment. NeuroImage 29:485–492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risold PY, Swanson LW (1996): Structural evidence for functional domains in the rat hippocampus. Science 272:1484–1486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez PF (2010a): Human navigation that requires calculating heading vectors recruits parietal cortex in a virtual and visually sparse water maze task in fMRI. Behav Neurosci 124:532–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez PF (2010b): Neural decoding of goal locations in spatial navigation in humans with fMRI. Hum Brain Mapp 31:391–397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum RS, Ziegler M, Winocur G, Grady CL, Moscovitch M (2004): “I have often walked down this street before”: fMRI studies on the hippocampus and other structures during mental navigation of an old environment. Hippocampus 14:826–835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savage CR, Deckersbach T, Heckers S, Wagner AD, Schacter DL, Alpert NM, Fischman AJ, Rauch SL. (2001). Prefrontal regions supporting spontaneous and directed application of verbal learning strategies: Evidence from PET. Brain 124:219–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz H, Sommer T, Peters J (2012): Direct evidence for domain‐sensitive functional subregions in human enthorinal cortex. J Neurosci 32:4716–4723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scoville WB, Milner B (1957): Loss of recent memory after bilateral hippocampal lesions. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 20:11–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelton AL, Gabrieli JDE (2002): Neural correlates of encoding space from route and survey perspectives. J Neurosci 22:2711–2717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheridan MA, Hinshaw S, D'Esposito M (2007): Efficiency of the prefrontal cortex during working memory in attention‐deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 46:1357–1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith ML, Milner B (1982): The role of the right hippocampus and the recall of spatial location. Neuropsychologia 19:781–793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperling RA, Bates JF, Cocchiarella AJ, Schacter DL, Rosen BR, Albert MS (2001): Encoding novel face‐name associations: A functional MRI study. Hum Brain Mapp 14:129–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperling R, Chua E, Cocchiarella A, Rand‐Giovannetti E, Poldrack R, Schacter D, Albert M. (2003): Putting names to faces: Successful encoding of associative memories activates the anterior hippocampal formation. NeuroImage 20:1400–1410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiers HJ, Maguire EA (2006): Thoughts, behaviour, and brain dynamics during navigation in the real world. NeuroImage 31:1826–1840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Squire LR, Alvarez P (1995): Retrograde amnesia and memory consolidation: A neurobiological perspective. Curr Opin Neurobiol 5:169–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Squire LR, Ojemann JG, Miezin FM, Petersen SE, Videen TO, Raichle ME (1992): Activation of the hippocampus in normal humans: A functional anatomical study of memory. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 89:1837–1841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suthana N, Ekstrom A, Moshirvaziri S, Knowlton B, Bookheimer S (2011): Dissociations within human hippocampal subregions during encoding and retrieval of spatial information. Hippocampus 21:694–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talairach J, Tournoux P (1988):Co‐planar Stereotaxic Atlas of the Human Brain. New York:Thieme. [Google Scholar]

- Talmi D, Grady CL, Goshen‐Gottstein Y, Moscovitch M (2005): Neuroimaging the serial position curve: A test of single‐store versus dual‐store models. Psychol Sci 16:716–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taube JS (2007): The head direction signal: Origins and sensory‐motor integration. Annu Rev Neurosci 30:181–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SF, Liberzon I, Fig LM, Decker LR, Minoshima S, Koeppe RA (1998): The effect of emotional content on visual recognition memory: A PET activation study. NeuroImage 8:188–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tulving E (2002): Episodic memory: From mind to brain. Annu Rev Psychol 53:1–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turkeltaub PE, Eden GF, Jones KM, Zeffiro TA (2002): Meta‐analysis of the functional neuroanatomy of single‐word reading: Method and validation. Neuroimage 16:765–780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vargha‐Khadem F, Gadian DG, Watkins KE, Connelly A, Van Paesschen W, Mishkin M (1997): Differential effects of early hippocampal pathology on episodic and semantic memory. Science 277:376–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weniger G, Siemerkus J, Schmidt‐Samoa C, Mehlitz M, Baudewig J, Dechent P, Irle E. (2010): The human parahippocampal cortex subserves egocentric spatial learning during navigation in a virtual maze. Neurobiol Learn Mem 93:46–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler ME, Petersen SE, Bukner RL (2000): Memory's echo: Vivid remembering reactivates sensory‐specific cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci 97:11125–11129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson MA, McNaughton BL (1993): Dynamics of the hippocampal ensemble code for space. Science 261:1055–1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witter MP, Naber PA, van Haeften T, Machielsen WC, Rombouts SA, Barkhof F, Scheltens P, Lopes da Silva FH. (2000): Cortico‐hippocampal communication by way of parallel parahippocampal‐subicular pathways. Hippocampus 10:398–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolbers T, Büchel C (2005): Dissociable retrosplenial and hippocampal contributions to successful formation of survey representations. J Neurosci 25:3333–3340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeineh MM, Engel SA, Thompson PM, Bookheimer SY (2003): Dynamics of the hippocampus during encoding and retrieval of face‐name pairs. Science 299:577–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]