Abstract

The effects of the 5‐HTTLPR polymorphism on neural responses to emotionally salient faces have been studied extensively, focusing on amygdala reactivity and amygdala‐prefrontal interactions. Despite compelling evidence that emotional face paradigms engage a distributed network of brain regions involved in emotion, cognitive and visual processing, less is known about 5‐HTTLPR effects on broader network responses. To address this, we evaluated 5‐HTTLPR differences in the whole‐brain response to an emotional faces paradigm including neutral, angry and fearful faces using functional magnetic resonance imaging in 76 healthy adults. We observed robust increased response to emotional faces in the amygdala, hippocampus, caudate, fusiform gyrus, superior temporal sulcus and lateral prefrontal and occipito‐parietal cortices. We observed dissociation between 5‐HTTLPR groups such that LALA individuals had increased response to only angry faces, relative to neutral ones, but S′ carriers had increased activity for both angry and fearful faces relative to neutral. Additionally, the response to angry faces was significantly greater in LALA individuals compared to S′ carriers and the response to fearful faces was significantly greater in S′ carriers compared to LALA individuals. These findings provide novel evidence for emotion‐specific 5‐HTTLPR effects on the response of a distributed set of brain regions including areas responsive to emotionally salient stimuli and critical components of the face‐processing network. These findings provide additional insight into neurobiological mechanisms through which 5‐HTTLPR genotype may affect personality and related risk for neuropsychiatric illness. Hum Brain Mapp 36:2842–2851, 2015. © 2015 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

Keywords: 5‐HTTLPR, serotonin, partial least squares, emotion, faces

INTRODUCTION

Emotional face paradigms have been widely used in the context of functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to probe brain regions and neural pathways responsive to emotionally salient stimuli, particularly aversive stimuli such as indices of threat. Previous studies have linked these neuroimaging measures to variability in behavioral and personality measures associated with risk for depression [Etkin et al., 2004; Stein et al., 2007]. Additionally, neuroimaging studies have reported altered response patterns in individuals with depression and linked these effects with treatment response, indicating these paradigms are useful for probing neural pathways underlying risk for and treatment of neuropsychiatric illness [Ruhe et al., 2011; Stuhrmann et al., 2011]. Thus, identifying predictors of variability in response to emotional face paradigms can inform our understanding of neurobiological mechanisms that contribute to risk for and treatment of neuropsychiatric illness. A broad corpus of literature in animal models and humans implicates serotonin signaling in modulating the neural response to aversive stimuli [Fisher and Hariri, 2012; Holmes, 2008]. This has motivated a large body of literature evaluating the extent to which genetic variants within serotonin‐related genes predict the neural response to aversive stimuli, most notably the 5‐HTTLPR polymorphism.

The 5‐HTTLPR is a polymorphism within the promoter region of the gene coding for the serotonin transporter and has been widely studied in the context of fMRI paradigms probing the response to emotionally salient stimuli. In vitro, the L or LA allele (L + A allele at rs25531) is associated with increased serotonin transporter expression compared to the S or S′ allele (LG, SA, or SG alleles) [Heils et al., 1995; Hu et al., 2006]. Most commonly, S′ carriers have been associated with significantly greater threat‐related amygdala reactivity compared to LALA individuals, but this effect size is estimated to be small [Murphy et al., 2013]. Although the 5‐HTTLPR polymorphism likely contributes to differences in the response to emotionally salient stimuli of other brain regions, this is not as commonly studied. This is partly due to an emphasis on the amygdala as a critical brain region for processing emotionally salient, in particular threat‐related, stimuli. It is also likely due to a region‐of‐interest approach focused on the amygdala to limit the negative effect on statistical power of the multiple comparisons penalty that results from voxel‐level univariate models. The result is a well‐studied effect on amygdala reactivity but a limited understanding of 5‐HTTLPR effects on the response of other brain regions known to be involved in emotion processing. There is some evidence that the neural response of regions critically involved in face perception (e.g., fusiform gyrus) and emotion regulation (e.g., prefrontal cortex) are affected by 5‐HTTLPR genotype but this remains less well understood [Hariri et al., 2002; Pezawas et al., 2005; Surguladze et al., 2008]. Here, we use a multivariate analytic approach for evaluating 5‐HTTLPR effects on emotional brain function to enhance our ability to identify distributed networks that respond similarly by modeling shared covariance across spatiotemporal dimensions.

Partial least squares (PLS) is a multivariate approach that models shared covariance across brain regions with respect to group/condition effects, a method effectively implemented in an fMRI framework [McIntosh and Lobaugh, 2004; McIntosh et al., 1996]. Support for this approach in the context of evaluating serotonin‐related effects on the response to emotional faces includes a study from our lab which demonstrated that acute serotonergic manipulation modulated brain network response patterns in an emotion‐specific manner [Grady et al., 2013]. However, this approach has not been previously applied toward evaluating 5‐HTTLPR effects on emotionally salient stimuli.

Within the current study we used PLS to evaluate emotion‐condition and 5‐HTTLPR genotype differences in the response to a paradigm involving gender‐discrimination of emotional faces including neutral, angry and fearful faces, in a cohort of 76 healthy individuals. Based on previous studies, we anticipated that we would see responses to emotional faces in a distributed set of brain regions, including important emotion and face‐processing regions, such as the amygdala, prefrontal cortex, insula, striatum and fusiform gyrus [Haxby et al., 2000; Phillips et al., 2003]. Our primary interest was whether this distributed response would be modulated by 5‐HTTLPR genotype.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

Data from 76 healthy participants were included in the current study (see Table 1 for demographic information). All participants were recruited from the Copenhagen region via online advertisements for research projects approved by the Ethics Committee of Copenhagen and Frederiksberg, Denmark (H‐1‐2010‐091, amendments: 28633, 30043; H‐1‐2010‐085, amendments 28641, 33540; (KF)01‐2006‐20, amendment: 23504, 23830). Inclusion criteria included: (1) 18–50 years of age, (2) no self‐reported present or past psychiatric or neurological illness, (3) no self‐reported present or past substance or alcohol abuse, (4) normal physical/neurological examination and blood screening results. Notably, some projects recruited only males and others recruited based on 5‐HTTLPR genotype status (i.e., oversampling of LALA and S′S′ individuals). Informed consent was obtained prior to study participation. All participants had structural MR‐images free from abnormalities. Two participants self‐reported mixed ethnic background (one European/African and one European/South American). Results are reported including all participants. Notably, all significant genotype and emotion condition effects remained when excluding these two participants. Emotional faces fMRI data from 30 [Fisher et al., 2014b] and 32 [Fisher et al., 2015] of the participants included in the current study have been described in unrelated studies.

Table 1.

Demographic information

| LALA | S′ carrier | P‐value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 31 | 45 | |

| Male/Female | 27/4 | 40/5 | 0.81 |

| Age (Mean ± SD) | 25.6 ± 5.1 | 25.7 ± 5.4 | 0.95 |

5‐HTTLPR distribution LALA: 31, LAS′: 22, S′S′: 23. Genotype groups deviate from Hardy‐Weinberg due to over‐sampling LALA and S′S′ individuals.

Genotyping

Analysis of genotype information was performed on DNA purified from saliva or blood samples.

Genotype status for the 5‐HTTLPR (SLC6A4; 17q11.1‐q12) was performed using a TaqMan 5′‐exnuclease allelic discrimination assay (Assay‐on‐Demand, Applied Biosystems, Foster City, California). The ABI 7500 multiplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR) device (Applied Biosystems) was used for this analysis. Status for the rs25531 A/G polymorphism was determined as described in [Kalbitzer et al., 2010]. Briefly, rs25531 status was determined by PCR amplification from the forward primer 5′‐GGCGTTGCCGCTCTGAATGC‐3′ and reverse primer 5′‐GAGGGACTGAGCTGGACAACCAC‐3′. The fragments were then digested by the restriction enzyme MspI and separated by gel electrophoresis. We report results from the “tri‐allelic” classification (i.e., LA = LA allele, S′ = LG, SA, or SG alleles) although we note that we obtained very similar results when considering the “biallelic” 5‐HTTLPR classification (i.e., LL vs. S‐carriers). Although our analysis focused on the comparison between LALA and S′ carriers, PLS effects comparing LALA, LAS′ and S′S′ groups separately can be found in Supporting Information Figures 1–4.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging Acquisition

Participants underwent a scan session in a 3T‐Trio MRI scanner using an eight‐channel head coil (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) as described previously [Fisher et al., 2014b; Grady et al., 2013; Hornboll et al., 2013]. Blood oxygen level‐dependent (BOLD) functional magnetic resonance images (fMRI) images were acquired using a T2*‐weighted echo‐planar imaging sequence (repetition time = 2500 msec, echo time = 26 msec, flip angle = 76°, in‐plane matrix = 64 × 64, in‐plane resolution = 3 × 3 mm, number of slices within a whole‐brain volume = 41, slice thickness = 3 mm, gap = 0.75 mm). Image acquisition was optimized for signal recovery within orbital frontal cortex by tilting slice orientation from a transverse toward a coronal orientation by approximately 30°, and using a preparation gradient pulse [Deichmann et al., 2003]. A total of 312 whole‐brain volumes (156 per run) were acquired for each scan session. A high‐resolution T1‐weighted whole‐brain three‐dimensional structural magnetic resonance scan was also acquired using a spin‐echo sequence (inversion time = 800 msec, echo time = 3.92 msec, repetition time = 1540 msec, flip angle = 9°, in‐plane matrix = 256 × 256, in‐plane resolution = 1 × 1 mm, number of slices = 192, slice thickness = 1 mm, no gap).

Emotional Faces Paradigm

Participants completed a gender discrimination task described previously [Fisher et al., 2014b; Hornboll et al., 2013] including blocks of fearful, angry or neutral faces from the Karolinska Directed Emotional Faces database [Lundqvist et al., 1998]. Each trial consisted of the stimulus presented for 1800 ms and an inter‐stimulus interval of 200 ms during which time a fixation cross (“+”) was present on the screen. Each block comprised six trials including three to five “faces” trials (mean face trials per block = 4) and one to three “null” trials (mean null trials per block = 2) consisting of a fixation cross (“+”). Faces and null trials were randomly mixed within each block. In total, 32 blocks of neutral faces were interleaved between 16 blocks of fearful and 16 blocks of angry faces presented across two fMRI runs with a brief break between runs. Neutral faces were presented twice throughout the task whereas fearful and angry faces were presented once. Stimulus presentations and response recordings were performed using E‐prime (Psychological Software Tools, Pittsburgh, PA).

Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging Data Analysis

Preprocessing of functional images including realignment, coregistration, normalization into Montreal Neurological Institute space and smoothing (8 mm Gaussian filter) was performed using SPM5 (http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/) and VBM5 (http://dbm.neuro.uni-jena.de/vbm/vbm5-for-spm5/) in Matlab version 8.1 (http://www.mathworks.com) as previously described [Fisher et al., 2014b]. Smoothed functional images (voxel‐size: 2 × 2 × 2 mm) were masked so as to include only voxels with a gray‐matter probability >0.1 and a cerebrospinal‐fluid probability <0.3 based on probability templates from SPM8 (csf.nii and grey.nii images in “apriori” folder). PLS uses information from all voxels so this masking was performed to ensure that ventricle voxels and those with low probability of being gray‐matter were excluded from the analysis.

Univariate Statistical Analysis

For comparison against our multivariate analysis we evaluated 5‐HTTLPR effects on brain response within a univariate framework. Voxel‐level genotype effects were evaluated independently against fear—neutral, angry—neutral and aversive (fear and angry)—neutral contrasts. We used 3dClustSim, a program in AFNI (http://afni.nimh.nih.gov/afni) to determine cluster threshold unlikely to occur by chance (α < 0.05) at a voxel‐level threshold of P < 0.01, uncorrected. Given compelling evidence for 5‐HTTLPR effects on amygdala reactivity, we performed an ROI analysis on this region as defined by WFU Pickatlas v3.0.3 [Maldjian et al., 2003]. An exploratory whole‐brain analysis was also performed. The statistically significant cluster extents for our amygdala and whole‐brain search volumes were 12 and 555 voxels, respectively. Genotype‐specific mean contrast estimates from the anatomical amygdala ROI can be found in Supplementary Information Table 1.

Partial Least Squares Analysis

PLS analyses were performed similar to as described previously [Grady et al., 2013] using plsgui (v. 6.1311050; http://www.rotman-baycrest.on.ca) in Matlab. PLS is a data‐driven multivariate analytic approach that identifies spatiotemporal patterns covarying with task conditions. Similar to other multivariate techniques, PLS identifies patterns explaining the covariance between conditions and brain activity in order of the amount of covariance explained [Krishnan et al., 2011]. Here, our analysis consisted of three face conditions (neutral, angry and fearful) and two groups (LALA and S′ carriers).

We adjusted time series using a block‐based signal normalization, which normalizes each time point in a block to the first time point in that block, and then calculated the mean activity for each condition, for each participant. Neuroimaging data per condition and participants were loaded into a single data matrix that was decomposed using singular value decomposition to extract voxel‐wise patterns of activity (latent variables, LV) that covaried across all experimental conditions.

Each LV identified a specific contrast of the three face conditions for each genotype group and a spatial pattern of brain activity reflecting the strength of each voxel's relation to an LV (salience). Each LV has a singular value reflecting the amount of covariance accounted for by that LV. P‐values are calculated for each LV, rather than for each voxel, because each LV identifies a whole‐brain pattern of covarying activity computed in a single step. The statistical significance of each LV was determined by a permutation test, which determines the likelihood by chance of obtaining a singular value greater than what we observed. For each of 1000 permutations, the conditions for each participant were randomly scrambled and the PLS model estimated and singular values determined. The probability that an observed singular value was exceeded by permuted singular values was used to calculate a P‐value, which identified LVs that were unlikely to have occurred by chance and analyzed further. LVs with a P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

We used voxel saliences to identify brain regions that strongly contributed to an LV pattern. Each voxel has a salience for each LV, which is a weight proportional to the covariance of its activity with the LV‐specific task contrast. To estimate the robustness of these salience estimates, we used a bootstrap procedure to determine the standard error (SE) of observed saliences for a LV [Efron, 1981]. For each of the 200 bootstraps, participants were randomly sampled, with replacement, and saliences estimated, providing an estimated SE for each voxel salience. The ratio of an observed salience and its SE (bootstrap ratio, BSR) was computed for each voxel. These ratios are analogous to Z‐scores meaning that a |BSR| > 3 roughly corresponds to a P < 0.005 [Sampson et al., 1989]. Voxels with a |BSR| > 3.0 and within a cluster > 100 voxels were considered as robustly contributing to the LV.

We calculated “brain scores” to determine group/condition contrasts supported by an LV, which are summary measures of each participant's expression of a given LV pattern. We calculated brain scores by multiplying each voxel salience by its normalized condition‐specific BOLD signal and summed across all voxels. Thus, we computed condition‐specific brain scores for each participant. These are similar to a factor score from a principal components analysis. The 95% confidence interval (CI) for each mean brain score was estimated via the bootstrap procedure. To determine differences due to group and/or condition, the brain scores were mean‐centered based on the grand mean across all groups/conditions, and significant differences in mean brain scores between groups/conditions were determined by a lack of overlap in relevant CIs (overlapping CIs indicate similar levels of activity).

Put another way, we used PLS to identify dimensions (LVs) within the space of our neuroimaging data, emotion condition and 5‐HTTLPR capturing the most covariance. Where we identified a dimension capturing a statistically significant amount of covariance we (1) evaluated which voxels most robustly related to that dimension and (2) evaluated how that dimension distinguished emotion conditions and genotype status based on brain score estimates, which are analogous to a summary statistic of the whole‐brain response.

Neuroimaging data were visualized using R version 3.0.2 [R Core Team, 2013] and xjview (http://www.alivelearn.net/xjview).

RESULTS

Demographic information is detailed in Table 1. Age and sex were well matched across genotype groups.

Our PLS analysis identified one significant LV capturing a large amount of covariance across all brain voxels, emotion conditions and genotype groups (total covariance explained: 36.8%, P = 0.011). The set of brain regions that were robustly and positively associated with this LV included regions critically involved in threat and general emotion‐related processing as well as faces and general visual processing: amygdala, hippocampus, lateral prefrontal cortex, caudate, superior temporal sulcus, occipital, and fusiform areas (Table 2, Fig. 1). Generally, these regions were more responsive for angry and fearful faces compared with neutral faces, although there were group differences in this response, described below. Additionally, there were three clusters that were negatively associated with the LV in cingulate and frontal cortices (Table 2), indicating reduced activity during emotional faces.

Table 2.

Brain regions in 5‐HTTLPR dependent network

| Region | X | Y | Z | Bootstrap ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Right hemisphere | ||||

| R fusiform gyrus | 44 | −46 | −16 | 9.33 |

| R amygdala | 30 | −4 | −20 | 9.22 |

| R hippocampus | 32 | −6 | −20 | 8.74 |

| R inferior occipital gyrus | 36 | −92 | −2 | 7.35 |

| R superior temporal sulcus | 52 | −16 | −6 | 7.24 |

| R lateral prefrontal cortex | 60 | 30 | 4 | 7.12 |

| R parahippocampal gyrus | 24 | −4 | −24 | 6.83 |

| R precentral gyrus | 14 | −24 | 74 | 5.78 |

| R caudate | 20 | −22 | 22 | 5.75 |

| R superior frontal gyrus | 14 | 44 | 54 | 4.96 |

| R cerebellum | 8 | −46 | −32 | 4.70 |

| R precuneus | 6 | −60 | 36 | 4.03 |

| R postcentral gyrus | 14 | −30 | 76 | 3.80 |

| R cingulate gyrus | 12 | 0 | 50 | −5.08 |

| Left hemisphere | ||||

| L middle occipital gyrus | −32 | −94 | 4 | 8.60 |

| L fusiform gyrus | −40 | −50 | −16 | 7.91 |

| L amygdala | −28 | −4 | −20 | 7.49 |

| L hippocampus | −28 | −6 | −20 | 6.52 |

| L lateral prefrontal cortex | −54 | 26 | −10 | 4.95 |

| L caudate | −14 | 20 | 10 | 4.84 |

| L middle frontal gyrus | −54 | 22 | 32 | 4.75 |

| L cerebellum | −4 | −64 | −46 | 4.71 |

| L precentral gyrus | −10 | −32 | 74 | 4.21 |

| L parahippocampal gyrus | −22 | −14 | −32 | 4.18 |

| L precuneus | −14 | −42 | 72 | 3.86 |

| L postcentral gyrus | −32 | −26 | 48 | −6.18 |

| L medial frontal gyrus | −6 | −6 | 56 | −5.02 |

Locations are expressed in MNI coordinates. Negative bootstrap ratios indicate negative saliences (i.e., showing an opposite emotion‐condition response profile as shown in Fig. 2).

Figure 1.

Brain network predicted by 5‐HTTLPR genotype. Parametric map illustrating brain regions that robustly contributed to the significant latent variable distinguishing 5‐HTTLPR genotype and emotional face conditions. Image is thresholded at |bootstrap ratio| > 3.0, cluster extent threshold > 100 voxels. Warm colors depict areas with greater activity during conditions with positive brain scores (see Fig. 2). Cool colors depict areas with reduced activity during conditions with positive brain scores. Scale reflects bootstrap ratio units. Slices are in MNI z‐coordinates. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

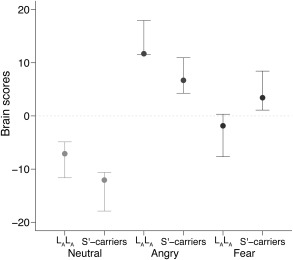

This LV identified brain response patterns that differentiated genotype groups and emotion conditions (Fig. 2). Across 5‐HTTLPR groups, the mean brain score for neutral faces was significantly lower than for angry faces (i.e., 95% CIs do not overlap). There was no significant difference between 5‐HTTLPR groups in the brain scores for neutral faces (LALA 95% CI: −7.09 [−11.63, −4.87], S′ carriers 95% CI: −12.06 [−17.89, −10.62]). However, other differences between emotion conditions were dependent on 5‐HTTLPR genotype. We observed dissociation between 5‐HTTLPR genotypes in the brain response to angry and fearful faces. Specifically, the brain scores of LALA individuals for fearful faces (95% CI: −1.84 [−7.66, 0.32]) were equivalent to those for neutral faces and significantly less than angry faces (95% CI: 11.71 [11.56, 17.96]), indicating a robust response only to angry faces, relative to neutral faces, in the LALA group. In contrast, the S′ carriers showed robust responses to both angry and fearful compared to neutral faces. The brain scores for fearful faces of S′ carriers (95% CI: 3.44 [1.10, 8.43]) were similar to angry faces (95% CI: 6.71 [4.26, 10.95]), and both were significantly greater than neutral faces. In terms of differences between the groups, LALA individuals had significantly higher brain scores for angry faces compared to S′ carriers, and S′ carriers had significantly higher brain scores for fearful faces relative to LALA individuals.

Figure 2.

Mean brain scores for emotional face conditions by 5‐HTTLPR genotype. Zero reflects mean brain response across all conditions. Points and errors bars show respective group mean and 95% confidence interval brain scores (based on bootstrap analysis). Nonoverlapping confidence intervals indicate significant differences between respective groups/conditions.

As a comparison to the PLS analysis, we evaluated univariate effects of 5‐HTTLPR genotype on fear—neutral, angry—neutral, and aversive (fear and angry)—neutral faces. We observed no statistically significant effects of genotype on amygdala reactivity with an ROI analysis or any other regions with a whole‐brain analysis (see Supporting Information Table 1 for extracted amygdala estimates).

DISCUSSION

Here, we report the identification of a pattern of brain activity reflecting 5‐HTTLPR genotype and emotion‐specific response patterns based on a PLS analysis of the BOLD response to an emotional faces paradigm. Notably, brain regions that robustly contributed to the LV included key emotional and face‐processing regions including the amygdala, hippocampus, prefrontal cortex, caudate, superior temporal sulcus and fusiform, and occipital cortices. There was a dissociable brain response to fearful faces such that LALA individuals showed no increase to fearful faces above that seen to neutral faces, whereas S′ carriers showed increased activity to fearful and angry faces. In addition, these emotion and face‐processing regions were more responsive to angry faces in LALA individuals compared to S′ carriers, but significantly more responsive to fear faces in S′ carriers compared to LALA individuals. Taken together, our findings support 5‐HTTLPR genotype effects on a distributed pattern of brain activity, providing novel evidence for the neurobiological effects of genotype on the response to emotional faces at multiple nodes within face‐ and emotion‐processing networks.

We identified a 5‐HTTLPR dependent dissociation in the brain response to fearful faces such that in LALA individuals this response was similar to that of neutral faces, whereas in S′ carriers it was similar to that of angry faces and differed from the response to neutral faces. Across many cognitive tasks among humans and non‐human primates, S or S′ carriers appear to show heightened sensitivity to salient environmental stimuli, including indices of threat, relative to LALA individuals [Borg et al., 2009; Jedema et al., 2010; Murphy et al., 2013]. Our findings also point toward a heightened sensitivity in the brain response to fearful faces of S′ carriers. However, our result goes beyond previous work to show that this heightened response includes not only the amygdala, but also regions critically involved in identifying and contextualizing emotionally salient stimuli and generating and regulating response to emotional stimuli, such as the hippocampus, caudate, and bilateral lateral prefrontal cortex [Phillips et al., 2003]. These findings may reflect a heightened but balanced engagement of a network that both drives and regulates responsiveness to indices of fear in healthy S′ carriers. Although speculative, this balanced response may contribute to the participants being generally healthy and without neuropsychiatric illness. Based on the model that S′ carrier status confers risk for mood and anxiety disorders that is moderated by stressful life events [Caspi et al., 2010], this generally heightened brain response may reflect this risk state in the absence of an environmental trigger. In addition to these emotion‐processing areas, critical face‐processing regions, such as fusiform gyrus, occipital face area and superior temporal sulcus [Haxby et al., 2002], also showed increased activity for fearful faces in S′ carriers and for angry faces across 5‐HTTLPR groups. We interpret activity in these regions as a reflection of several processes: face processing, the assignment of salience/emotional content and resulting feedback between brain regions based on perceived salience [Kilpatrick and Cahill, 2003; Morris et al., 1998; Pessoa and Adolphs, 2010]. Although previous studies have reported significant effects of 5‐HTTLPR genotype on the BOLD response to emotional faces in some of these regions [Canli et al., 2005; Hariri et al., 2002; Surguladze et al., 2008], our findings provide direct evidence that 5‐HTTLPR genotype affects the coherent response of these regions, as a group, to support successful processing of face identity (i.e., gender) and emotional salience. Consistent with this heightened sensitivity model, our findings point toward a neural bias in S′ carriers toward a heightened, more “angry‐like” response profile to fearful faces but a more “neutral‐like” response profile in LALA individuals.

Contrary to the effect on fearful faces, S′ carriers showed a significantly reduced brain response to angry faces compared to LALA individuals. This finding is intriguing because, to the best of our knowledge, no previous studies have reported a decreased response to angry faces in S′ carriers in populations of European ancestry. Notably, our approach models each condition in the context of all others but without specifying a contrast (e.g., angry–neutral faces). As a rough approximation, Figure 2 suggests that the difference in average brain scores between angry and neutral faces is similar for LALA and S′ carriers. Thus, our findings may reflect an effect that is typically masked by the contrast approach employed in a univariate framework. Despite the difference between LALA and S′ carriers, both groups showed a positive response compared to neutral faces. Our brain score estimates reflect response profiles derived from the entire brain, so they are not directly comparable to region specific contrasts, but nevertheless point toward a novel genetic effect that should be evaluated further in future studies.

Our data do not allow us to disentangle whether these findings reflect 5‐HTTLPR dependent alterations in circuit function (e.g., structural alterations) that may have emerged during development or effects mediated by alterations in serotonin signaling [Hariri and Holmes, 2006]. There is evidence for 5‐HTTLPR effects on brain morphology in humans and non‐human primates [Jedema et al., 2010; Selvaraj et al., 2011] and there have been mixed findings regarding 5‐HTTLPR effects on serotonin transporter binding potential in humans, assessed with positron emission tomography [Kalbitzer et al., 2009; Murthy et al., 2010; Parsey et al., 2006; Praschak‐Rieder et al., 2007; Reimold et al., 2007]. However, high levels of serotonin receptor expression in task‐responsive brain regions [Hall et al., 1997; Varnas et al., 2011, 2001], evidence that 5‐HTTLPR predicts a molecular neuroimaging marker that may reflect a feature of serotonin signaling [Fisher et al., 2014a], and evidence that an acute serotonergic manipulation altered the emotional response in many of the regions we identify here [Grady et al., 2013] suggests that 5‐HTTLPR effects on brain function may be mediated by alterations in serotonin signaling.

Notably, medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) and anterior cingulate cortex did not robustly contribute to the pattern of activity seen here, despite previous studies linking 5‐HTTLPR genotype with mPFC reactivity and connectivity with the amygdala [Dannlowski et al., 2008; Heinz et al., 2005; Pezawas et al., 2005]. Relaxing our cluster extent threshold revealed a 25 voxel cluster within mPFC that was negatively associated with our LV, suggesting a weak contribution. In this context, a “negative” association means the group/condition response profile of this region is directionally opposite that described in Figure 2. We observed a similar response profile within midcingulate, medial frontal gyrus and pre‐ and postcentral gyri, suggesting that these regions showed a positive response to neutral faces and negative response to angry and fearful faces, which is consistent with the idea that areas like mPFC regulate the neural response to emotionally salient stimuli [Phillips et al., 2003]. Complimentary tasks focused on engaging emotional regulation circuits might be better suited to reveal a pattern of activity to which mPFC and other critical regulatory regions may more robustly contribute.

Most previous studies evaluating 5‐HTTLPR effects have used a univariate approach based on a specified contrast (e.g., fear faces – neutral faces). We did not observe significant 5‐HTTLPR effects with a univariate approach, which, based on power calculations reported by Murphy et al., [2013], likely partly reflects low statistical power. An advantage of multivariate approaches like PLS is greater statistical power compared to univariate techniques, which is particularly relevant when probing potentially small genetic effects [Lukic et al., 2002]. We argue that this multivariate approach is advantageous compared to univariate techniques by modeling shared covariance across brain regions rather than independently modeling variance within voxels or regions. This is conceptually appealing based on evidence that 5‐HTTLPR genotype affects many features of brain function [Firk et al., 2013; Jonassen et al., 2012; Kruschwitz et al., 2014; Stollstorff et al., 2013], not just amygdala reactivity, and that task‐condition responses likely reflect multiple interlinked features of brain function. Conversely, we are unaware of a clear method for partitioning how much of the covariance captured by our latent variable is due to 5‐HTTLPR. Many 5‐HTTLPR studies have used ROI approaches, which is sensible given that serotonin affects emotional processing, which is strongly affected by amygdala reactivity. However, this limits the ability to probe 5‐HTTLPR effects on brain function across regions outside a priori defined circuits. Our current findings highlight advantages of this multivariate approach, indicating that 5‐HTTLPR modulates the response of a distributed network of brain regions in an emotion‐specific manner.

Our current study is not without its limitations. Our cohort reflects data collected from different studies, which used generally similar inclusion criteria but may have introduced additional heterogeneity. Our study included mostly males due to study‐specific inclusion criteria. Future studies including more females would provide insight into the extent that our findings generalize. Over‐sampling for LALA and S′S′ individuals deviates from a normative sample but in the case of our study aim may have enhanced our ability to detect differences between genotype groups. Our sample size is moderate to large compared to other studies evaluating 5‐HTTLPR effects on response to emotional faces but still smaller than suggested sample sizes [Murphy et al., 2013]. By maximizing shared covariance, PLS, and other such multivariate approaches, identify effects that capture large proportions of covariance. True effects within small regions will be difficult to identify because they capture a smaller proportion of total covariance. Alternatively, distinguishing such effects from false‐positives would prove difficult in a univariate framework. Our paradigm did not include an exhaustive set of emotional valences (e.g., happy faces) and therefore provides limited insight into 5‐HTTLPR effects on emotional faces. Previous evidence for valence‐dependent 5‐HTTLPR effects suggests that applying PLS to an emotional faces fMRI dataset including additional valences would provide a more comprehensive estimate of 5‐HTTLPR effects on emotion‐specific brain responses [Dannlowski et al., 2010; Heinz et al., 2005].

In summary, we provide evidence that 5‐HTTLPR genotype has significant condition‐specific effects on the response of a distributed set of brain regions to an emotionally salient faces paradigm. Our findings suggest a dissociable response between LALA and S′ carriers to fearful faces. Additionally, 5‐HTTLPR significantly predicted differences in the response to fear and angry faces across brain areas critically involved in emotional and face processing. These findings provide novel insight into how this polymorphism, putatively through effects on neural pathways and serotonin signaling, contributes to individual variability in emotionally relevant brain function, which may affect risk for neuropsychiatric disorders.

Supporting information

Supplementary Information

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Collection of data that was included in the study was supported by the Lundbeck Foundation Center of Excellence Cimbi [R90‐A7722]. The authors would like to acknowledge the Simon Spies Foundation for the donation of the Siemens Trio MRI scanner. The authors thank the Hasholt‐Nørremølle laboratory in the Section of Neurogenetics at the Department of Cellular and Molecular Medicine, University of Copenhagen, for their assistance with genotyping. We thank Sussi Larsen, Julian Macoveanu, Pernille Iversen, and Peter Jensen for assistance in data collection and management.

Conflicts of Interest: GMK has received honoraria as Field Editor of the International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology and as scientific advisor for H. Lundbeck A/S. All other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

REFERENCES

- Borg J, Henningsson S, Saijo T, Inoue M, Bah J, Westberg L, Lundberg J, Jovanovic H, Andrée B, Nordstrom AL, Halldin C, Eriksson E, Farde L (2009): Serotonin transporter genotype is associated with cognitive performance but not regional 5‐HT1A receptor binding in humans. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 12:783–792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canli T, Omura K, Haas BW, Fallgatter A, Constable RT, Lesch KP (2005): Beyond affect: A role for genetic variation of the serotonin transporter in neural activation during a cognitive attention task. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102:12224–12229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Hariri AR, Holmes A, Uher R, Moffitt TE (2010): Genetic sensitivity to the environment: The case of the serotonin transporter gene and its implications for studying complex diseases and traits. Am J Psychiatry 167:509–527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dannlowski U, Konrad C, Kugel H, Zwitserlood P, Domschke K, Schoning S, Ohrmann P, Bauer J, Pyka M, Hohoff C, Zhang W, Baune BT, Heindel W, Arolt V, Suslow T (2010): Emotion specific modulation of automatic amygdala responses by 5‐HTTLPR genotype. Neuroimage 53:893–898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dannlowski U, Ohrmann P, Bauer J, Deckert J, Hohoff C, Kugel H, Arolt V, Heindel W, Kersting A, Baune BT, Suslow T (2008): 5‐HTTLPR biases amygdala activity in response to masked facial expressions in major depression. Neuropsychopharmacology 33:418–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deichmann R, Gottfried JA, Hutton C, Turner R (2003): Optimized EPI for fMRI studies of the orbitofrontal cortex. Neuroimage 19:430–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efron B (1981): Nonparametric estimates of standard error: The jackknife, the bootstrap and other methods. Biometrika 68:589–599. [Google Scholar]

- Etkin A, Klemenhagen KC, Dudman JT, Rogan MT, Hen R, Kandel ER, Hirsch J (2004): Individual differences in trait anxiety predict the response of the basolateral amygdala to unconsciously processed fearful faces. Neuron 44:1043–1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firk C, Siep N, Markus CR (2013): Serotonin transporter genotype modulates cognitive reappraisal of negative emotions: A functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Social Cogn Affective Neurosci 8:247–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher PM, Ewers HM, Jensen CG, Frokjaer VG, Siebner HR, Knudsen GM (2015): Fluctuations in [11C]SB207145 PET binding associated with change in threat‐related amygdala reactivity in humans. Neuropsychopharmacology 40:1510–1518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher PM, Hariri AR (2012): Linking variability in brain chemistry and circuit function through multimodal human neuroimaging. Genes Brain Behav 11:633–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher PM, Holst KK, Adamsen D, Klein AB, Frokjaer VG, Jensen PS, Svarer C, Gillings N, Baare WF, Mikkelsen JD, Knudsen GM (2014a): BDNF Val66met and 5‐HTTLPR polymorphisms predict a human in vivo marker for brain serotonin levels. Hum Brain Mapp 36:313–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher PM, Madsen MK, Mc Mahon B, Holst KK, Andersen SB, Laursen HR, Hasholt LF, Siebner HR, Knudsen GM (2014b): Three‐week bright‐light intervention has dose‐related effects on threat‐related corticolimbic reactivity and functional coupling. Biol Psychiatry 76:332–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grady CL, Siebner HR, Hornboll B, Macoveanu J, Paulson OB, Knudsen GM (2013): Acute pharmacologically induced shifts in serotonin availability abolish emotion‐selective responses to negative face emotions in distinct brain networks. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 23:368–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall H, Lundkvist C, Halldin C, Farde L, Pike VW, McCarron JA, Fletcher A, Cliffe IA, Barf T, Wikstrom H, Sedvall G (1997): Autoradiographic localization of 5‐HT1A receptors in the post‐mortem human brain using [3H]WAY‐100635 and [11C]way‐100635. Brain Res 745:96–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hariri AR, Mattay VS, Tessitore A, Kolachana B, Fera F, Goldman D, Egan MF, Weinberger DR (2002): Serotonin transporter genetic variation and the response of the human amygdala. Science 297:400–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hariri AR, Holmes A (2006): Genetics of emotional regulation: The role of the serotonin transporter in neural function. Trends Cogn Sci 10:182–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haxby JV, Hoffman EA, Gobbini MI (2000): The distributed human neural system for face perception. Trends Cogn Sci 4:223–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haxby JV, Hoffman EA, Gobbini MI (2002): Human neural systems for face recognition and social communication. Biol Psychiatry 51:59–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heils A, Teufel A, Petri S, Seemann M, Bengel D, Balling U, Riederer P, Lesch KP (1995): Functional promoter and polyadenylation site mapping of the human serotonin (5‐HT) transporter gene. J Neural Transm Gen Sect 102:247–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinz A, Braus DF, Smolka MN, Wrase J, Puls I, Hermann D, Klein S, Grusser SM, Flor H, Schumann G, Mann K, Buchel C (2005): Amygdala‐prefrontal coupling depends on a genetic variation of the serotonin transporter. Nat Neurosci 8:20–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes A (2008): Genetic variation in cortico‐amygdala serotonin function and risk for stress‐related disease. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 32:1293–1314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornboll B, Macoveanu J, Rowe J, Elliott R, Paulson OB, Siebner HR, Knudsen GM (2013): Acute serotonin 2A receptor blocking alters the processing of fearful faces in the orbitofrontal cortex and amygdala. J Psychopharmacol 27:903–914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu XZ, Lipsky RH, Zhu G, Akhtar LA, Taubman J, Greenberg BD, Xu K, Arnold PD, Richter MA, Kennedy JL, Murphy DL, Goldman D (2006): Serotonin transporter promoter gain‐of‐function genotypes are linked to obsessive‐compulsive disorder. Am J Human Genetics 78:815–826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jedema HP, Gianaros PJ, Greer PJ, Kerr DD, Liu S, Higley JD, Suomi SJ, Olsen AS, Porter JN, Lopresti BJ, Hariri AR, Bradberry CW (2010): Cognitive impact of genetic variation of the serotonin transporter in primates is associated with differences in brain morphology rather than serotonin neurotransmission. Mol Psychiatry 446:512–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonassen R, Endestad T, Neumeister A, Foss Haug KB, Berg JP, Landrø NI (2012): Serotonin transporter polymorphism modulates N‐back task performance and fMRI BOLD signal intensity in healthy women. PLoS ONE 7:e30564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalbitzer J, Erritzoe D, Holst KK, Nielsen FA, Marner L, Lehel S, Arentzen T, Jernigan TL, Knudsen GM (2010): Seasonal changes in brain serotonin transporter binding in short serotonin transporter linked polymorphic region‐allele carriers but not in long‐allele homozygotes. Biol Psychiatry 67:1033–1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalbitzer J, Frokjaer VG, Erritzoe D, Svarer C, Cumming P, Nielsen FA, Hashemi SH, Baare WF, Madsen J, Hasselbalch SG, Kringelbach ML, Mortensen EL, Knudsen GM (2009): The personality trait openness is related to cerebral 5‐HTT levels. Neuroimage 45:280–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick L, Cahill L (2003): Amygdala modulation of parahippocampal and frontal regions during emotionally influenced memory storage. Neuroimage 20:2091–2099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan A, Williams LJ, McIntosh AR, Abdi H (2011): Partial Least Squares (PLS) methods for neuroimaging: A tutorial and review. Neuroimage 56:455–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JD Kruschwitz, M Walter, D Varikuti, J Jensen, MM Plichta, L Haddad, O Grimm, S Mohnke, L Pohland, B Schott, A Wold, TW Muhleisen, A Heinz, S Erk, N Romanczuk‐Seiferth, SH Witt, MM Nothen, M Rietschel, A Meyer‐Lindenberg, H Walter (2014): 5‐HTTLPR/rs25531 polymorphism and neuroticism are linked by resting‐state functional connectivity of amygdala and fusiform gyrus. Brain Struct Funct Epub ahead of print. DOI: 10.1007/s00429-014-0782-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukic AS, Wernick MN, Strother SC (2002): An evaluation of methods for detecting brain activations from functional neuroimages. Artif Intell Med 25:69–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundqvist D, Flykt A, Ohman A (1998) The Karolinska Directed Emotional Faces ‐ KDEF. In: CD ROM from Department of Clinical Neuroscience, Psychology section, Karolinska Institutet.

- Maldjian JA, Laurienti PJ, Kraft RA, Burdette JH (2003): An automated method for neuroanatomic and cytoarchitectonic atlas‐based interrogation of fMRI data sets. Neuroimage 19:1233–1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh AR, Bookstein FL, Haxby JV, Grady CL (1996): Spatial pattern analysis of functional brain images using partial least squares. Neuroimage 3:143–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh AR, Lobaugh NJ (2004): Partial least squares analysis of neuroimaging data: Applications and advances. Neuroimage 23:S250–S263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JS, Friston KJ, Buchel C, Frith CD, Young AW, Calder AJ, Dolan RJ (1998): A neuromodulatory role for the human amygdala in processing emotional facial expressions. Brain 121 (Pt 1):47–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy SE, Norbury R, Godlewska BR, Cowen PJ, Mannie ZM, Harmer CJ, Munafo MR (2013): The effect of the serotonin transporter polymorphism (5‐HTTLPR) on amygdala function: A meta‐analysis. Mol Psychiatry 18:512–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murthy NV, Selvaraj S, Cowen PJ, Bhagwagar Z, Riedel WJ, Peers P, Kennedy JL, Sahakian BJ, Laruelle MA, Rabiner EA, Grasby PM (2010): Serotonin transporter polymorphisms (SLC6A4 insertion/deletion and rs25531) do not affect the availability of 5‐HTT to [11C] DASB binding in the living human brain. Neuroimage 52:50–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsey RV, Hastings RS, Oquendo MA, Hu X, Goldman D, Huang YY, Simpson N, Arcement J, Huang Y, Ogden RT, Van Heertum RL, Arango V, Mann JJ (2006): Effect of a triallelic functional polymorphism of the serotonin‐transporter‐linked promoter region on expression of serotonin transporter in the human brain. Am J Psychiatry 163:48–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pessoa L, Adolphs R (2010): Emotion processing and the amygdala: From a 'low road' to 'many roads' of evaluating biological significance. Nat Rev Neurosci 11:773–783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pezawas L, Meyer‐Lindenberg A, Drabant EM, Verchinski BA, Munoz KE, Kolachana BS, Egan MF, Mattay VS, Hariri AR, Weinberger DR (2005): 5‐HTTLPR polymorphism impacts human cingulate‐amygdala interactions: A genetic susceptibility mechanism for depression. Nat Neurosci 8:828–834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips ML, Drevets WC, Rauch SL, Lane R (2003): Neurobiology of emotion perception I: The neural basis of normal emotion perception. Biol Psychiatry 54:504–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Praschak‐Rieder N, Kennedy J, Wilson AA, Hussey D, Boovariwala A, Willeit M, Ginovart N, Tharmalingam S, Masellis M, Houle S, Meyer JH (2007): Novel 5‐HTTLPR allele associates with higher serotonin transporter binding in putamen: A [(11)C] DASB positron emission tomography study. Biol Psychiatry 62:327–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team (2013) R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. [Google Scholar]

- Reimold M, Smolka MN, Schumann G, Zimmer A, Wrase J, Mann K, Hu XZ, Goldman D, Reischl G, Solbach C, Machulla HJ, Bares R, Heinz A (2007): Midbrain serotonin transporter binding potential measured with [11C]DASB is affected by serotonin transporter genotype. J Neural Transm 114:635–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruhe HG, Booij J, Veltman DJ, Michel MC, Schene AH (2011): Successful pharmacologic treatment of major depressive disorder attenuates amygdala activation to negative facial expressions: A functional magnetic resonance imaging study. J Clin Psychiatry 73:451–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson PD, Streissguth AP, Barr HM, Bookstein FL (1989): Neurobehavioral effects of prenatal alcohol: Part II. Partial least squares analysis. Neurotoxicol Teratol 11:477–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selvaraj S, Godlewska BR, Norbury R, Bose S, Turkheimer F, Stokes P, Rhodes R, Howes O, Cowen PJ (2011): Decreased regional gray matter volume in S' allele carriers of the 5‐HTTLPR triallelic polymorphism. Mol Psychiatry 16:471–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein MB, Simmons AN, Feinstein JS, Paulus MP (2007): Increased amygdala and insula activation during emotion processing in anxiety‐prone subjects. Am J Psychiatry 164:318–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stollstorff M, Munakata Y, Jensen APC, Guild RM, Smolker HR, Devaney JM, Banich MT (2013): Individual differences in emotion‐cognition interactions: Emotional valence interacts with serotonin transporter genotype to influence brain systems involved in emotional reactivity and cognitive control. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuhrmann A, Suslow T, Dannlowski U (2011): Facial emotion processing in major depression: A systematic review of neuroimaging findings. Biol Mood Anxiety Disord 1:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surguladze SA, Elkin A, Ecker C, Kalidindi S, Corsico A, Giampietro V, Lawrence N, Deeley Q, Murphy DG, Kucharska‐Pietura K, Russell TA, McGuffin P, Murray R, Phillips ML (2008): Genetic variation in the serotonin transporter modulates neural system‐wide response to fearful faces. Genes Brain Behav 7:543–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varnas K, Nyberg S, Halldin C, Varrone A, Takano A, Karlsson P, Andersson J, McCarthy D, Smith M, Pierson ME, Soderstrom J, Farde L (2011): Quantitative analysis of [11C]AZ10419369 binding to 5‐HT1B receptors in human brain. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 31:113–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varnas K, Hall H, Bonaventure P, Sedvall G (2001): Autoradiographic mapping of 5‐HT1B and 5‐HT1D receptors in the post mortem human brain using [3H]GR 125743. Brain Research 915:47–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Information