Abstract

Human olfactory system is under‐studied using fMRI compared with other sensory systems. Because the perception (intensity, threshold, and valence) and detection of odors are tightly involved with respiration, the subject's respiration pattern modulates and interacts with the experimental paradigm, which presents difficulties for olfactory fMRI data acquisition, post‐processing, and interpretation. Based on our investigation on the interactions of odor presentation and subject's respiration, we propose a respiration‐triggered event‐related olfactory fMRI technique and a data post‐processing method that effectively captures precise onsets of olfactory blood‐oxygen‐level‐dependent (BOLD) signal in the primary olfactory cortex. We compared the olfactory BOLD signals from seventeen normal healthy adults with diverse respiratory patterns and showed that the subjects' respiratory patterns modulated the olfactory stimulation paradigm, which significantly confounded the BOLD signal. The presented experimental technique provides a simple and effective means for generating reliable olfactory fMRI results. Hum Brain Mapp 35:3616–3624, 2014. © 2013 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

Keywords: olfaction, respiration, fMRI, BOLD signal, odor stimulation, olfactory activation

INTRODUCTION

There has been a great interest in studying the central olfactory system using fMRI, because the central olfactory system, as an integral part of human limbic system, plays an important role in human emotions and homeostasis. Clinically, olfactory deficits are known to occur in a number of prevalent neurological and psychiatric disorders and diseases, such as Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, and post‐traumatic stress disorders [Doty, 1989; Serby et al., 1985; Vasterling et al., 2000]. However, the number of fMRI studies of the central olfactory system, is relatively small compared with all other sensory nervous systems. One reason limiting olfactory fMRI for clinical applications is the issue of delivering the odor to the recipient precisely in synchronization with the subject's respiration. This seemingly trivial issue, in effect, plays an important role in obtaining reliable and reproducible olfactory fMRI data. In fact, respiration is an integrated part of the odor detection and perception scheme of the olfactory system. Thus, accurate control of odor delivery with respect to respiration of the subject is a critical part of olfactory fMRI data acquisition and interpretation.

The blood‐oxygen‐level‐dependent (BOLD) signal change in fMRI typically ranges from 0.5 to 3%, dependent on the static magnetic field strength of the MR system and varies among brain regions and tasks. In an event‐related stimulation paradigm, the BOLD signal change in response to single event stimulation is usually close to or even <0.5% at 3 T. This signal change is close to the noise level of MR images, thus requiring multiple event repetitions to increase the image signal to noise ratio. In odor stimulation paradigm designs, subject's respiration rates increase the difficulty of achieving accurate stimulation onset. The relatively slow respiration frequency and its high variability among individuals confound the onset, duration, and intensity of odor delivery. Attempting to overcome this timing issue, a number of olfactory fMRI studies trained participants to follow visual or auditory cues for respiration and smelling [Krusemark and Li, 2012; Moessnang et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2010]. Despite improving the odor stimulation timing, such methods inevitably involve additional central nervous systems beyond the targeted olfactory system thus confounding data analysis. In individuals with neurological or psychiatric disorders, such visual and auditory cues may be ineffective eliminating any potential stimulation improvement due to lack of subject compliance.

Additional attempts to overcome the synchronization problem of subject's respiration with odor delivery by increasing the number of stimulus presentations will generate strong habituation effects. Such effects, notoriously known to olfaction, limit the number of repetitive exposures to the same odor in stimulating the olfactory system. Previous studies have shown that within a long, continuous odor presentation (more than 30 s), the BOLD signal in the primary olfactory cortex (POC) only persists for several seconds [Poellinger et al., 2001; Sobel et al., 2000; Tabert et al., 2007]. Thus, in general, block‐design paradigms are ineffective for olfactory fMRI studies [Boley et al., 1998; Furman and Koizuka, 1994; Loevner and Yousem, 1997; Sobel et al., 1998; Tabert et al., 2007; Zatorre et al., 1992]. To reduce the habituation effect, some investigators have attempted to sustain olfactory activation levels by switching odor concentrations and types during the same stimulation session [Gottfried et al., 2002; Krusemark and Li, 2012; Moessnang et al., 2011; Valdez et al., 2003; Wang et al., 2005, 2010]. Both methods complicate the data analysis and subsequent interpretation of the results. Given the considerations above, the event‐related stimulation (i.e., short odor stimulations with multiple repetitions) is a method of choice. The challenge with event‐related stimulation is to keep odor stimulation events consistent throughout the fMRI paradigm. To be able to quantify the brain activation responding to odor stimulation using event‐related fMRI, ideally the amount of odor stimulation, , with t = duration of odor presentation, needs to be constant and reproducible. This can be achieved when odor delivery is synchronized with the same phase of respiration cycles.

In this report, we demonstrate that the subject's respirations significantly interfere with olfactory fMRI data acquisition and confound further data analysis. We present a respiration‐triggered event‐related paradigm design for olfactory fMRI, without visual or auditory cues to control subject's respiration or sniffing, effectively removing timing errors caused by variations in subject's respiration patterns. In addition, we present a post‐processing tool that can retrospectively mitigate such timing errors during fixed‐timing fMRI data acquisition paradigm designs, and further improve respiration‐triggered stimulation paradigms.

METHODS

Odor Stimulation Paradigm

The odor stimulation paradigm was executed with a programmable olfactometer (Emerging Tech Trans, LLC, Hershey, PA), which delivers up to six different odors to subject's nostrils accurately without any optical, acoustic, thermal, or tactile cues to the subject. The olfactometer delivered constant airflow with 50% relative humidity at room temperature (22°C). The odor stimulation paradigm and MR image acquisition were synchronized using optical triggers from the MRI scanner. During the execution of the fMRI paradigm, timing of odor delivery onsets and image acquisitions were recorded and referenced with the subject's respiration trace. As shown in Figure 1, odor delivery onsets can be executed following the timing of the paradigm alone (fixed‐timing) or triggered by the respiration of the subject in reference to the timing of the paradigm (respiration‐triggered). In the latter case, the subject's respiration cycle was measured and a 1/2 cycle delay from the beginning of exhalation phase is added to the timing of the odor onset such that the odor delivery is initiated at the beginning of the inhalation phase. The delay time was adjusted by reference to the real‐time respiration trace before the execution of the odor stimulation paradigm. Lavender oil (Givaudan Flavors Corporation, East Hanover, NJ) diluted in 1,2‐propanediol (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) at 0.10% (volume/volume) was used as the olfactory stimulant. 0.10% of lavender oil in 1,2‐propanediol was chosen as a stimulus based upon its effectiveness in inducing fMRI activation in young adults [Grunfeld et al., 2005]. The stimulant was stored in six 300 ml glass jars, each holding 50 ml of the odorant. Lavender is one of the most effective olfactory stimulants with minimal to no propensity to stimulate the trigeminal system [Allen, 1936; Patton, 1960]. It is generally perceived by North American individuals as being pleasant and familiar.

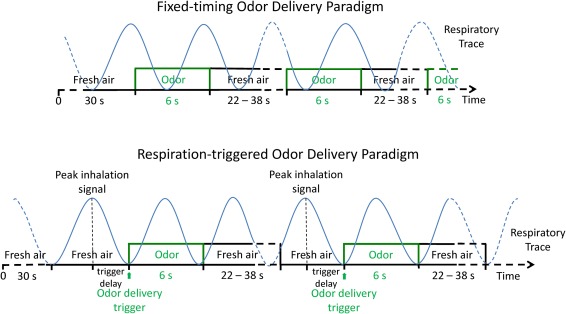

Figure 1.

Illustration of fixed‐timing odor delivery paradigm and the respiration‐triggered odor delivery paradigm. During the fixed‐timing paradigm (top), the onsets of odor delivery are predefined, thus it can happen at any time during a respiratory cycle. In contrast, with the respiration‐triggered paradigm (bottom), when the respiratory rhythm is relatively stable, the onsets of odor delivery can be synchronized with the inhalation phase of respiratory cycle. The trigger delay is the duration from the peak inhalation signal to the onset of odor delivery, which varies from 0.5 to 3 s. It is predetermined during the calibration of the synchronization of inhalation and odor delivery by the study administrator. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

In this study, each subject received the same odor simulation paradigm twice, with and without the respiration trigger in a randomized fashion. In the run without the respiration trigger the odor was delivered according to predetermined intervals in a fixed‐timing paradigm. A 6‐s odor presentation was repeated twelve times interleaved with 22 to 38‐s odorless fresh air (baseline) at a constant air flow of 6 L/min (3 L/min through the odorant chamber when the odorant was delivered) to the both nostrils simultaneously through Teflon tubing (inner diameter 6.35 mm) (Fig. 1 top). Each odorant channel would only open twice (6 s each time) during the execution of the 7 min 58 s paradigm to keep the odor concentration delivered consistent. The intervals between the odor deliveries were pseudo‐randomized to reduce anticipatory effect on the olfactory system. In the other run, odor delivery was triggered by the effective inhalation signal (i.e., respiration‐triggered odor delivery paradigm; Fig. 1 bottom). The subjects' respiration traces were monitored via a pneumatic respiration sensor and recorded at a frequency of 10 Hz together with the odor delivery onsets and timing of image acquisition by the olfactometer. During both runs air was constantly removed from the bore of the magnet through a venting pipe. Prior to the fMRI scan, subjects were instructed to breathe normally, and were instructed not to sniff at any time throughout the fMRI paradigm. To maximize the odor stimulation effect while minimizing the effect from sniffing and other olfactory related functions (e.g., anticipation and evaluation) during fMRI data acquisition, no cues for smell or respiration were given to the subject, nor were they asked to provide any response. After fMRI, the subjects confirmed that they sensed odors during the fMRI scans.

Human Subjects

Twenty healthy human subjects with no history of otorhinolaryngical, neurological or psychiatric conditions were recruited from local community by advertisement. All subjects gave written, informed consent consistent with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Pennsylvania State University College of Medicine institutional review board. Data from three subjects were excluded from analysis due to either excessive head movement (two subjects) or not being able to finish the fMRI study (sleeping during the execution of fMRI protocol, one subject). Data from remaining seventeen subjects (age 28.5 ± 6.8 years, 7 male, 2 left‐handed) with normal smell function [University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test (UPSIT, Sensonics, Haddon Heights, NJ) score 36.5 ± 1.9] were included in the data analysis.

fMRI Study Protocol

The fMRI study was performed on a Siemens 3.0 T system (Magnetom Trio, Siemens Medical Solutions, Erlangen, Germany) with an 8‐channel head coil for signal reception. The subjects were positioned in the supine position in a dark environment with their heads fit into a head restrainer to minimize motion and to provide precise positioning and comfort. The subjects' respiration and sniffing patterns were monitored to exclude sniffing and any irregular respiration changes. A BOLD signal sensitive T2*‐weighted EPI sequence was used for fMRI image acquisition with repetition time (TR)/echo time (TE)/flip angle (FA) = 2000 ms/30 ms/90°, field of view (FOV) = 220 × 220 mm2, acquisition matrix = 80 × 80, 30 axial slices with a slice thickness = 4 mm, iPAT acceleration factor (GRAPPA) = 2, number of repetitions = 239 with an acquisition time of 7 min 58 s for the fixed‐timing odor delivery paradigm and 269 repetitions for the respiration‐triggered paradigm with an acquisition time of 8 min 58 s. Anatomical images were acquired with a three‐dimensional MPRAGE method with TR/TE/FA = 2300/2.98 ms/9°, FOV = 256 × 256 × 160 mm3, acquisition matrix = 256 × 256 × 160, image resolution = 1 × 1 × 1 mm3, and iPAT factor = 2.

Data Processing and Analysis

The respiration trace data, odor delivery timing data, and image acquisition timing data were processed with a software tool, called ONSET (Olfactory Network Stimulation Editing Tool) for actual stimulation onset and duration vectors (http://www.pennstatehershey.org/web/nmrlab/resources/software). The software automatically detects the actual odor onset based on the timing of the paradigm and the respiration trace. Briefly, the recorded respiration traces were first smoothed with 1.1‐s moving window average, and then the inhalation and exhalation were identified using the sign of the derivatives of respiration trace. Both amplitude and duration were used to exclude the small fluctuations in the respiration trace in identifying the inhalation onsets and durations. The valid inhalation must be with duration ≥ 0.5 s and amplitude ≥ 1/5 of average inhalation amplitude of whole respiration trace. The actual stimulation onset was defined as the start time of each effective inhalation during the odor delivery time period (see Fig. 2). The effective inhalation is the inhalation during odor delivery. In addition, the respiration rate and volume were measured and compared between odor and odorless periods. The respiration volume is the area under each inhalation and exhalation phase pair.

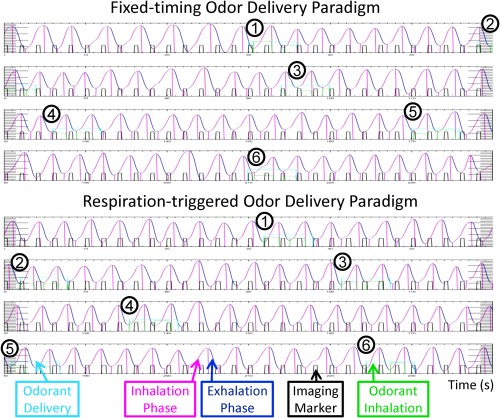

Figure 2.

An example of processed respiratory trace data by the ONSET. The first 240‐s of the fixed‐timing odor delivery paradigm (top) and respiration‐triggered odor delivery paradigm (bottom) from the same subject. The curve plot is the respiration trace data, with inhalation phase labeled in pink color and exhalation phase in dark blue. Each row is 60‐s long continuous to the next row. The bars in black color are the imaging markers that collected at the beginning of each image acquisition (2 s in this study). The time‐window for odor delivery is labeled in light blue color box. The duration of effective odor delivery (odor delivery during inhalation phase) is labeled in green color box. Synchronization of odor delivery and inhalation can be seen during respiration‐triggered odor delivery paradigm, that is, all six rounds of odor delivery happened at the beginning of the inhalation phase. In contrast, the odor delivery and inhalation during fixed‐timing paradigm was not synchronized. Out of the 6 rounds of odor delivery, twice (#1 and #6) happened in the middle of exhalation phase, once (#5) at the end of exhalation phase, and twice (#2 and #3) at the end of inhalation phase. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

The fMRI data were processed with SPM8 (Wellcome Trust Centre for Neuroimaging, University College London, UK) [Friston et al., 1994] following the standard procedure: (1) spatially realigned within the session to remove any minor head movements (movement < 2 mm, rotation < 1°); (2) coregistered with high‐resolution anatomical image; (3) normalized to the Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) brain template [Collins et al., 1998] in a spatial resolution of 2 × 2 × 2 mm3; and (4) smoothed with an 8 × 8 × 8 mm (full width at half maximum) Gaussian smoothing kernel. A statistical parametric map was generated at the individual level by fitting the stimulation paradigm to the functional data with a default 128‐s high pass filter, convolved with the canonical hemodynamic response function (uncorrected, P < 0.001, extent threshold = 10). Olfactory activation maps at the group level were generated separately for the fixed‐timing stimulation paradigm with predefined onset and duration vectors, and with actual onset and duration vectors for both the fixed‐timing paradigm and the respiration‐triggered paradigm (one‐sample t‐tests, uncorrected, P < 0.001, extent threshold = 10). The BOLD signals responding to the fixed‐timing paradigm and the respiration‐triggered paradigm were compared using paired t‐tests. The BOLD signal in the POC from each subject was recorded and averaged. The region of interest the POC, including the piriform cortex, anterior olfactory nucleus, olfactory tubercle, periamygdaloid cortex, entorhinal cortex, and corticomedial portion of amygdala was generated by the manual segmentation of T1‐weighted brain images from another group of 33 adults (Fig. 3A). The average BOLD signal at the POC responding to the fixed‐timing or respiration‐triggered paradigm was compared using a paired t‐test with SPSS Version 21.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY).

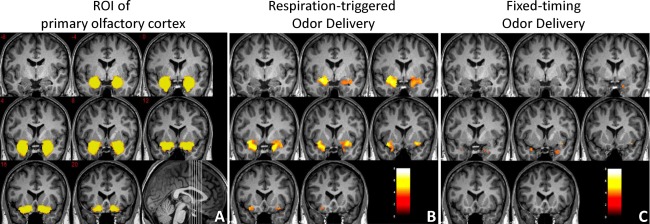

Figure 3.

The region of interest of POC (A) and its activation responding to respiration‐triggered odor delivery (B) or to fixed‐timing odor delivery and processed with predefined onset vectors (C). One‐sample t‐tests, n = 17, uncorrected, P < 0.001, extent threshold = 10, coronal view, MNI y = −8 to 20 mm. Color scale represents the significance of the activation (t‐value). [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

RESULTS

Figure 2 shows two typical time‐courses of fMRI data acquisition recording that include subject's respiration trace, odor onsets/durations, and image acquisition events. In the recordings, the actual odor onsets/durations generated with ONSET software were shown as green boxes. During the fixed‐timing paradigm (top of Fig. 2), the onsets of odor delivery are predefined, thus can happen at any time during a respiratory cycle. As indicated, the odor delivery events and the subject's inhalations were mismatched in various degrees randomly over the time course for the fixed‐timing odor delivery paradigm, yielding inconsistent odor onsets, and durations. In the demonstrated case, three onsets of the six odor events were mismatched with the inhalation phases during the fixed‐timing paradigm. In contrast, a precise synchronization of odor delivery with inhalation was achieved for the entire respiration‐triggered odor delivery paradigm (bottom of Fig. 2).

For the fixed‐timing odor delivery paradigm, the actual perceived odor strength was also modulated by inconsistent overlap of the respiration phases with odor events in the paradigm. These timing errors and inconsistent odor strength variations introduced significant variability into the fMRI data. Direct application of statistical parametric mapping with predefined odor onset vectors to the data acquired through fixed‐timing paradigm at the individual level (uncorrected, P < 0.001, extent threshold = 10) results in activation in only 60% of subjects (11 out of 17 subjects) and 24% of the subjects with POC activation (4 subjects). The subjects with significant activation results were those whose inhalation synchronized with odor deliveries by chance. Conversely, the respiration‐triggered odor delivery induced significant activation in the olfactory system (including bilateral POC, orbitofrontal cortex, inferior and anterior insular cortex, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, hippocampus, dorsal and ventral striatum, thalamus, and cingulate cortex) in all the participants (100%) at the same statistic threshold, with significant POC activation in 82% of the participants (14 subjects). Using ONSET retrospectively, the odor onset/duration errors were reduced by generating a new set of actual odor onset vectors according the subject's respiratory pattern during fixed‐timing odor delivery paradigm. With the actual stimulation vectors of onsets and durations, activation was observed in 76% of subjects (13 subjects), and POC activation was seen in 35% of subjects (6 subjects).

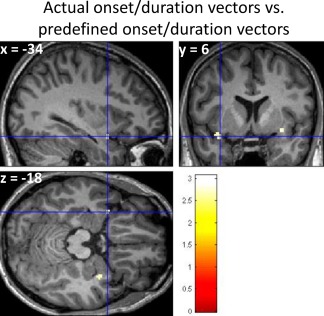

When the subjects were breathing freely and the odor delivery was triggered by respiration, significant activation was observed in the bilateral POC (Fig. 3B and Table 1). In contrast, when the fixed‐timing data processed using predefined odor onset/duration vectors yielded significantly less activation in the POC (Fig. 3C and Table 1). Accordingly, using actual stimulation onset and duration vectors with ONSET improved the detection of POC activation (Fig. 4 and Table 1).

Table 1.

POC activation results responding to 0.10% lavender with odor delivery triggered by respiration, with fixed‐timing odor delivery and actual onset/duration vectors, and with fixed‐timing odor delivery and predefined onset/duration vectors

| Method | MNI Coordinates (mm) | Activation size (voxels) | Cluster‐level | Voxel‐level | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x | y | z | P corrected | P uncorrected | P FDR‐corrected | P uncorrected | ||

| Odor delivery | −26 | −2 | −18 | 801 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| triggered by respiration | 24 | 4 | −24 | 625 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.000 |

| Fixed‐timing odor | 40 | 10 | −14 | 11 | 0.113 | 0.519 | 0.026 | 0.000 |

| delivery & predefined | −32 | 8 | −26 | 14 | 0.102 | 0.463 | 0.026 | 0.000 |

| onset/duration | 18 | 0 | −28 | 13 | 0.106 | 0.480 | 0.026 | 0.000 |

| vectors | 26 | 10 | −32 | 24 | 0.074 | 0.332 | 0.026 | 0.000 |

| Fixed‐timing odor | 26 | 8 | −30 | 56 | 0.013 | 0.031 | 0.015 | 0.000 |

| delivery & actual | 16 | 4 | −12 | 13 | 0.110 | 0.268 | 0.015 | 0.000 |

| onset/duration vectors | −18 | 4 | −18 | 27 | 0.049 | 0.117 | 0.015 | 0.000 |

One‐sample t‐test, n = 17, uncorrected, P < 0.001, extent threshold = 10. MNI coordinates are given in the left‐posterior‐inferior system.

Figure 4.

The actual onset and duration vectors acquired from ONSET processing significantly improved the detection of POC activation triggered by the fixed‐timing odor delivery. Paired t‐test, n = 17, uncorrected, P < 0.01, extent threshold = 10. Color scale represents the significance of the activation difference (t‐value). [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

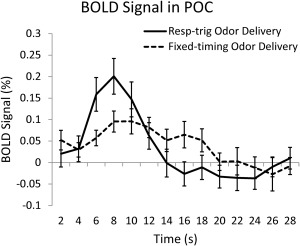

The timing variability for the duration of each run and across the cohort inevitably distorted the hemodynamic response function. Figure 5 shows the average BOLD signals in the POC obtained from the two paradigms. Because of the inconsistency in the timing of odor delivery due to respiration in the fixed‐timing paradigm, when it is averaged over time and within the cohort, the BOLD signal appeared to be “flattened and elongated”. The fixed‐timing odor delivery paradigm induced significantly weaker BOLD signal in the POC than the respiration‐triggered odor delivery (paired t‐test, n = 17, P = 0.028).

Figure 5.

The fixed‐timing odor delivery induced significantly weaker BOLD signal in the POC than the respiration‐triggered odor delivery (paired t‐test, n = 17, P = 0.028).

DISCUSSION

Respiration is an integral part of olfactory system because odorant administration is convolved with respiration; perception of a specific odor triggers the respiration response to dynamically adapt to the perceived odor intensity and/or valence (e.g., sniffing). Thus, in studying the function of the central olfactory system using fMRI, respiration data should be collected and incorporated into data analysis. Our data showed that it is critical to incorporate subjects' respiration data into both paradigm design and data processing in order to produce reliable olfactory fMRI data for scientific and clinical investigations. We demonstrated that with minimal anticipation effect by varying the intervals between odor presentations, the synchronization of a subject's inhalation with the odor presentation significantly improved olfactory fMRI data to a level comparable to that of other sensory systems (e.g., visual or somatosensory). The human olfactory system is known to be involved in many neurologic and psychological disorders [Doty, 1989]. One of our goals is to develop reliable olfactory fMRI methodologies such that it can be used as a biomarker for early diagnosis and quantitative evaluations of these neurological and psychiatric diseases. The sensitivity of olfactory fMRI as a biomarker largely depends on its sensitivity to odor stimulation and experimental reproducibility. The improvement in these aspects presented here is the first important step toward this goal.

From a neuroscientific point of view, the central olfactory system is an integral part of human limbic system playing an important role in human emotions and homeostasis. Study of human perception of odors using fMRI provides important information far beyond the olfactory system itself. However, perception of an odor includes intensity and valence, which are strongly modulated by, and behaviorally coupled with, respiration and sniffing. Thus, for the studies of the emotional attributes of odors and associated higher cognitive functions, it is essential to control odor intensity, which requires collection of respiration information during execution of the stimulation paradigm. In addition, previous literature has shown that variations in breathing depth and rate can introduce significant instability to the BOLD signals due to the associated physiological changes such as pulsation of blood and/or celebrospinal fluid and blood CO2 concentration change [Brosch et al., 2002; Raj et al., 2001]. The increase of respiration rate and depth can cause a BOLD signal drop while the decrease of breathing rate and depth can cause signal increase, with breath‐holding as an extreme case. Thus, when designing a stimulation paradigm for the study of the central olfactory system, incorporating visual and/or auditory cues that significantly alter natural respiration patterns should be carefully considered and avoided whenever possible. In all cases, the respiration data should be collected and correlation analysis between respiration and stimulation paradigm should be performed. If such correlation exists, the effect of respiration on the BOLD signal needs to be corrected. Several methods have been proposed for this purpose, for example, retrospective physiological motion correction [Glover et al., 2000] and respiration volume per time [Birn et al., 2006]. In our paradigm design, the subjects were instructed not to sniff and follow their own natural respiration patterns. During the execution of the stimulation paradigms, the subjects' respiration patterns were closely monitored. There was no significant airflow or pressure change during the respiration‐triggered paradigm, and no correlation between the respiration rate, volume, and the odor delivery paradigm. Under such conditions, experimental confounds were minimized in our olfactory fMRI data.

Previous chemosensory event‐related potential (CSERP) studies have shown that CSERP can be affected by both administration style and odor concentration [Lorig et al., 1996]. Interestingly, when odor was administered asynchronously with respiration in the cited study, the CSERP signal of the anterior part of the brain was stronger. The authors suggested a mechanism of subjective probability in the olfactory cognitive processing. Evidently, the odor events synchronized and unsynchronized with respiration involve different functional processes and may invoke significantly different brain activation patterns. Since the stimulation events in our fixed‐timing paradigm were presented repetitively and their synchronizations with respiration were random, the element of the “surprise” should be washed out over the paradigm. In addition, the intervals between odor events were varied to reduce the anticipatory effect. Thus, these potential confounding effects in our studies were minimized.

In this investigation, we focused on studying the activation in the primary olfactory brain structures responding to the odor stimulations. We did not give any cues to or asked the subjects to respond to odor stimulations during fMRI data collection to reduce potential confounding effects from additional cues. However, after fMRI we asked subjects to confirm that they smelled odors during fMRI data acquisition. Thus, we are certain that the observed activations were largely associated with odor stimulations. Conversely, the higher order brain activation would take place regardless of feedback from the subjects, and it is possible that some higher order activation (e.g., novelty, pleasantness) may not parallel the perception of odor, which may cause inter‐subject variations. For example, a weak perception of a specific odor may trigger a significantly strong cognitive function in some individuals. This may be a potential issue in studying the changes of brain activation in the neurodegenerative diseases, since the patients' olfactory functions for odor detection and perception may be impaired at different levels. Thus collecting subjects' feedback for odor detection, and subjective ratings of odor intensity and pleasantness in a separate run of the paradigm will be beneficial to detect such variations.

CONCLUSION

We presented a respiration‐triggered olfactory fMRI event‐related design and a data post‐processing method. Our experimental data demonstrated their utility in generating reliable olfactory fMRI results in subjects with normal smell functions. These methods can be valuable tools for the studies of olfactory deficits in central neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's disease and Parkinson's disease as it requires minimal participation from the subject during functional data acquisition.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Christopher W. Weitekamp and Jeffrey Vesek for assisting data acquisition, and Robert Mchugh for proof reading the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Allen W (1936): Studies on the level of anesthesia for the olfactory and trigeminal respiratory reflexes in dogs and rabbits. Am J Physiol 115:579–587. [Google Scholar]

- Birn RM, Diamond JB, Smith MA, Bandettini PA (2006): Separating respiratory‐variation‐related fluctuations from neuronal‐activity‐related fluctuations in fMRI. Neuroimage 31:1536–1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boley JC, Pontier JP, Smith S, Fulbright M (1998): Facial changes in extraction and nonextraction patients. Angle Orthod 68:539–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brosch JR, Talavage TM, Ulmer JL, Nyenhuis JA (2002): Simulation of human respiration in fMRI with a mechanical model. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng 49:700–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins DL, Zijdenbos AP, Kollokian V, Sled JG, Kabani NJ, Holmes CJ, Evans AC (1998): Design and construction of a realistic digital brain phantom. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 17:463–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doty RL (1989): Influence of age and age‐related diseases on olfactory function. Ann N Y Acad Sci 561:76–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friston KJ, Tononi G, Reeke GN, Jr., Sporns O, Edelman GM (1994): Value‐dependent selection in the brain: Simulation in a synthetic neural model. Neuroscience 59:229–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furman JM, Koizuka I (1994): Reorientation of poststimulus nystagmus in tilted humans. J Vestib Res 4:421–428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glover GH, Li TQ, Ress D (2000): Image‐based method for retrospective correction of physiological motion effects in fMRI: RETROICOR. Magn Reson Med 44:162–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottfried JA, O'Doherty J, Dolan RJ (2002): Appetitive and aversive olfactory learning in humans studied using event‐related functional magnetic resonance imaging. J Neurosci 22:10829–10837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunfeld R, Wang J, Meadowcroft M, Ansel L, Sun X, Eslinger PJ, Connor JR, Smith MB, Yang Q (2005): The responsiveness of fMRI signal to odor concentration; April 13‐17, 2005; Sarasota, FL: p A237–238. [Google Scholar]

- Krusemark EA, Li W (2012): Enhanced olfactory sensory perception of threat in anxiety: An event‐related fMRI study. Chemosens Percept 5:37–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loevner LA, Yousem DM (1997): Overlooked metastatic lesions of the occipital condyle: A missed case treasure trove. Radiographics 17:1111–1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorig TS, Matia DC, Peszka J, Bryant DN (1996): The effects of active and passive stimulation on chemosensory event‐related potentials. Int J Psychophysiol 23:199–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moessnang C, Frank G, Bogdahn U, Winkler J, Greenlee MW, Klucken J (2011): Altered activation patterns within the olfactory network in Parkinson's disease. Cereb Cortex 21:1246–1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton HD (1960): Taste, olfaction and visceral sensation In: Ruth TC, Fulton JF, editors. Medical Physiology and Biophysics. Philadelphia: Saunders. [Google Scholar]

- Poellinger A, Thomas R, Lio P, Lee A, Makris N, Rosen BR, Kwong KK (2001): Activation and habituation in olfaction‐‐an fMRI study. Neuroimage 13:547–560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raj D, Anderson AW, Gore JC (2001): Respiratory effects in human functional magnetic resonance imaging due to bulk susceptibility changes. Phys Med Biol 46:3331–3340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serby M, Corwin J, Conrad P, Rotrosen J (1985): Olfactory dysfunction in Alzheimer's disease and Parkinson's disease. Am J Psychiatry 142:781–782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobel N, Prabhakaran V, Desmond JE, Glover GH, Goode RL, Sullivan EV, Gabrieli JD (1998): Sniffing and smelling: Separate subsystems in the human olfactory cortex. Nature 392:282–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobel N, Prabhakaran V, Zhao Z, Desmond JE, Glover GH, Sullivan EV, Gabrieli JD (2000): Time course of odorant‐induced activation in the human primary olfactory cortex. J Neurophysiol 83:537–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabert MH, Steffener J, Albers MW, Kern DW, Michael M, Tang H, Brown TR, Devanand DP (2007): Validation and optimization of statistical approaches for modeling odorant‐induced fMRI signal changes in olfactory‐related brain areas. Neuroimage 34:1375–1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valdez RA, Rock MJ, Anderson AK, O'Rourke KI (2003): Immunohistochemical detection and distribution of prion protein in a goat with natural scrapie. J Vet Diagn Invest 15:157–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasterling JJ, Constans JI, Hanna‐Pladdy B (2000): Head injury as a predictor of psychological outcome in combat veterans. J Trauma Stress 13:441–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Eslinger PJ, Smith MB, Yang QX (2005): Functional magnetic resonance imaging study of human olfaction and normal aging. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 60:510–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Eslinger PJ, Doty RL, Zimmerman EK, Grunfeld R, Sun X, Meadowcroft MD, Connor JR, Price JL, Smith MB, Yang QX (2010): Olfactory deficit detected by fMRI in early Alzheimer's disease. Brain Res 1357:184–194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zatorre RJ, Jones‐Gotman M, Evans AC, Meyer E (1992): Functional localization and lateralization of human olfactory cortex. Nature 360:339–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]