Abstract

Near infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) is a functional imaging technique allowing measurement of local cerebral oxygenation. This modality is particularly adapted to critically ill neonates, as it can be used at the bedside and is a suitable and noninvasive tool for carrying out longitudinal studies. However, NIRS is sensitive to the imaged medium and consequently to the optical properties of biological tissues in which photons propagate. In this study, the effect of the neonatal fontanel was investigated by predicting photon propagation using a probabilistic Monte Carlo approach. Two anatomical newborn head models were created from computed tomography and magnetic resonance images: (1) a realistic model including the fontanel tissue and (2) a model in which the fontanel was replaced by skull tissue. Quantitative change in absorption due to simulated activation was compared for the two models for specific regions of activation and optical arrays simulated in the temporal area. A correction factor was computed to quantify the effect of the fontanel and defined by the ratio between the true and recovered change. The results show that recovered changes in absorption were more precise when determined with the anatomical model including the fontanel. The results suggest that the fontanel should be taken into account in quantification of NIRS responses to avoid misinterpretation in experiments involving temporal areas, such as language or auditory studies. Hum Brain Mapp, 2013. © 2011 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

Keywords: near infrared spectroscopy, magnetic resonance imaging, light propagation, Monte Carlo approach, neonate, fontanel, partial volume error

INTRODUCTION

Preterm newborn infants present a particular neurological susceptibility (developing brain). The number of preterm infants is constantly increasing with a current incidence of 6.2% of all births in France. According to recent studies, 36–60% of preterm newborns born before 30 weeks of gestation subsequently develop neurological sequelae such as motor disorders, language disabilities, and subsequent school progress‐related deficits (Larroque et al.,2004). Subsequent detailed analysis of the mechanisms of cerebral maturation to prevent, or at least more effectively manage these neurological anomalies, constitutes a health policy priority.

Term newborns also occasionally develop epileptic seizures related to brain injuries. In 75% of cases, electroencephalography (EEG) provides sufficient information to localize the origin of epileptic activity, determines severity criteria, and consequently establishes a prognosis. However, in 25% of cases, this tool is not sufficient to establish objective prognostic criteria, emphasizing the need for subsequent development of more precise and more powerful diagnostic tools.

Near infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) is a functional neuroimaging modality allowing estimation of local changes in hemoglobin concentration and tissue oxygenation (Jöbsis et al., 1977). NIRS can be used to assess local hemodynamic variations at the bedside allowing investigation of critically ill neonates without the need for transportation. In particular, NIRS can be performed on term and preterm newborns in intensive care units. This technique was first used in premature infants by Brazy et al. to monitor cerebral tissue oxygen saturation (Brazy et al.,1985). Several groups are currently using NIRS for neonatal brain investigation. For example, Hintz et al. used NIRS to image neonates with intracranial (IC) hemorrhage (Hintz et al.,1999). Optical images were compared with those acquired by ultrasound (US), computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), establishing a correlation between the four modalities. NIRS has also been used to analyze local changes in hemodynamics and oxygenation during evoked responses to visual (Karen et al.,2008; Meek et al.,1998), olfactory (Bartocci et al.,2000,2001), and auditory (Bortfeld et al.,2007; Kotilahti et al.,2010; Peña et al.,2003; Zaramella et al.,2001) stimulation and during seizures (Roche‐Labarbe et al.,2008a,b; Wallois et al.,2009; for review see Wallois et al.,2010). Optical imaging can also be used to generate three‐dimensional (3D) tomographic images of changes in hemoglobin concentration (Hebden et al.,2002).

Previous studies of the optical properties of neonatal tissues (van der Zee et al.,1991; van der Zee et al.,1993) have demonstrated that the near infrared (NIR) window allows detection of light across the whole infant brain. However, cerebral tissues are still developing at this age, and the skull is still in the process of ossification. During this period, a membrane called the fontanel, corresponding to a type of nonossified cartilage, fills the space between two sutures. The transparency of the fontanel also allows the anatomical study of certain areas of the brain by transcranial US imaging. Because of the heterogeneous composition of the skull, comprising fontanels and bones, temporal variations in oxygenation assessed by NIRS can be altered.

Newborns have six fontanels: bregmatic (anterior), lambdatic (posterior), pteric (temporal anterior), asteric (temporal posterior), and sphenoid fontanels. Temporal fontanels are particularly interesting because they cover a part of the temporal lobe that is involved in the development of language (Bortfeld et al.,2007,2009; Gervain et al.,2008; Minagawa‐Kawai et al.,2007; Peña et al.,2003; Wallois et al.,2011). In addition, temporal lobes are likely to be the most epileptogenic region of the brain to generate seizures (Bartolomei et al.,2008; Roche‐Labarbe et al.,2008a,b; Wallois et al.,2009,2010), Through optical imaging, Gervain et al. recently showed with optical imaging that newborns are sensitive to certain speech structures in the auditory domain that may facilitate later language development (Gervain et al.,2008). In addition, Peña et al. concluded that neonates are born with left hemisphere superiority to process specific properties of speech (Peña et al.,2003). Previously, we showed that the temporal fontanels had an impact on source localization in EEG in premature neonates (Roche‐Labarbe et al.,2008a). The present NIRS study, therefore, focuses on the temporal fontanels, which may be responsible for errors of interpretation of data concerning the spatial organization of physiological or pathological local hemodynamic responses, particularly in language studies. The goal of this study was to assess the effect of the fontanel on near‐infrared spectroscopy measurements. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that quantifies the effect of the neonatal fontanel on NIRS measurement.

In this study, CT and magnetic resonance (MR) images were combined to create two anatomical head models: (1) a realistic head model describing the fontanel and (2) a model in which the fontanel was replaced by skull tissue. Monte Carlo methods were then used to simulate light propagation in the two anatomical head models. Changes in the absorption coefficient due to an activation recovered for each head model were compared, and correction factors defined by the ratio between the true and recovered change were computed. The effect of the fontanel on NIRS measurements was then quantified in terms of additional partial volume error. As the optical properties of the fontanel have not been reported in the literature, those of cartilage (Youn et al.,2000) were considered an appropriate reference.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subject and Data Acquisition

The neonatal model was derived from a multimodal combination of high‐quality MR (T1‐ and T2‐weighted) and CT images of a female subject. The selected subject was at a gestational age of 40 weeks at the scanning date. Careful examination by an experienced pediatric neuroradiologist described normal anatomy with no detectable cerebral abnormality.

MR images were obtained using a 3T General Electric scanner at the Centre Hospitalier Universitaire (CHU) Amiens North Hospital in France. The structural 3D volumetric T1‐weighted imaging sequence was acquired using the following parameters: repetition time (TR) = 12.02 ms, echo time (TE) = 4.06 ms, and inversion time (TI) = 450 ms, with an acquisition matrix of 256 × 256 pixels, a data matrix of 256 × 256 pixels and a voxel size of 1 × 0.6 × 1 mm3. The 3D volumetric T2‐weighted image was acquired using the following parameters: TR = 3,000 ms, TE = 121.92 ms, and TI = 0 ms with an acquisition matrix of 256 × 256 pixels, a data matrix of 512 × 512 pixels and a voxel size of 1 × 0.47 × 0.47 mm3. The number of slices for sagittal acquisition was 92. High‐resolution MR imaging allowed visualization and identification of small tissue structures. The images were then resliced to 0.5 × 0.5 × 0.5 mm3. The corresponding 3D CT image was obtained using a General Electric scanner. Each slice consisted of 512 × 512 pixels which were obtained from a 256 × 256 acquisition matrix resulting in a voxel size of 0.28 × 0.28 × 0.63 mm3. Nonaxial images were reoriented in the axial plane.

Head model Creation

The construction of the head models from MR and CT images consisted of two main steps: (1) the coregistration of MR and CT images and (2) tissue segmentation.

Coregistration of MR and CT images

During this procedure, CT and MR images were coregistered and then normalized to the GRAMFC neonatal brain atlas template (Kazemi et al.,2007). In the first part of this procedure, T1‐ and T2‐weighted MR images were coregistered with rigid‐body mapping included in the Statistical Parametric Mapping (SPM5) software (Wellcome Trust Centre for Neuroimaging, UCL, London) (Collignon et al.,1995). In the second step, the CT image was coregistered to the corresponding T1‐weighted MR image by extracting an intracranial (IC) mask from the CT image and the MR images (Kazemi et al.,2009a,b). The IC mask from the MR image was obtained as the binary sum of the extracted brain and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) mask. The IC mask from the CT image was then registered to the corresponding MR mask by rigid‐body mapping included in the SPM5 software. Finally, in the third step, the T1‐weighted MR image was normalized to the neonatal brain template with an SPM5‐based technique, and the normalization parameters were applied to the coregistered CT image.

Tissue segmentation

A unified segmentation method (Ashburner and Friston,2005) in conjunction with a priori neonatal information (Prastawa et al.,2005) was used to segment the IC tissues including the CSF and the gray (GM) and white (WM) matter tissues from the T1‐weighted image. The probabilistic gray level masks of CSF, GM, and WM were then converted to binary masks by selecting the highest probability tissue for each voxel. A variational level set method (Kazemi et al., 2009b) was then used to segment the cranial bone (skull) and fontanel from the CT image. Finally, removal of the combined WM, GM, CSF, fontanel, and cranial bone masks from the MR image yielded the scalp mask. These three steps resulted in an anatomical model measuring 108 × 134 × 96 mm3 consisting of isotropic voxels of 0.5 × 0.5 × 0.5 mm3. The model was then manually corrected to eliminate noise and was anatomically verified by an expert.

Two specific anatomical head models were subsequently created: (1) the model in which the fontanel was described (including scalp, skull, fontanel, CSF, gray, and white matters) and (2) the model in which the fontanel voxels were replaced by skull voxels. The second model is mostly used in the literature (e.g., Heiskala et al.,2009) due to the difficulty of precisely determining the neonatal fontanel on standard images.

Optical Properties

The baseline optical properties selected to simulate photon propagation were taken from Fukui et al. at 800 nm, namely the absorption coefficient μa (mm−1), scattering coefficient μs (mm−1), anisotropy factor g, and refractive index n (see Table I; Fukui et al.,2003). The optical properties of the neonatal fontanel tissue were assumed to correspond to those of cartilage (Youn et al.,2000), as no data are available in the literature. This choice may not be optimal but provided a realistic framework for light propagation in the fontanel, as the structure of the fontanel, a tissue in a process of ossification, can be considered similar to that of cartilage. Three different optical absorption coefficients of the fontanel were also investigated and are described in Table II. The absorption coefficients from sets A and B were selected to mimic absorption coefficients of CSF and skull tissues, respectively. The absorption coefficient from set B was identical to the skull absorption coefficient although coupled to a different scattering coefficient. The absorption coefficient from set C corresponded to that of cartilage.

Table I.

Baseline optical properties of different tissues: absorption coefficient μa (mm−1), scattering coefficient μs (mm−1), anisotropy factor g, and refractive index n

| Tissue/property | μa (mm−1) | μs (mm−1) | g | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scalp | 0.018 | 19 | 0.9 | 1.3 |

| Skull | 0.016 | 16 | 0.9 | 1.3 |

| CSF | 0.0041 | 0.32 | 0.9 | 1.3 |

| Gray matter | 0.048 | 5.0 | 0.9 | 1.3 |

| White matter | 0.037 | 10 | 0.9 | 1.3 |

| Fontanel | 0.04 | 22 | 0.9 | 1.3 |

Table II.

Three sets of optical properties of the fontanel chosen to test probable and extreme cases: absorption coefficient μa (mm−1) and scattering coefficients μs (mm−1)

| Fontanel property | Set A | Set B | Set C |

|---|---|---|---|

| μa (mm−1) | 0.0064 | 0.016 | 0.04 |

| μs (mm−1) | 0.32 | 16 | 22 |

Set A corresponds to CSF‐like absorption, Set B to a skull‐like, and Set C corresponds to the case of a cartilage‐like absorption coefficient.

Optical Array Configurations

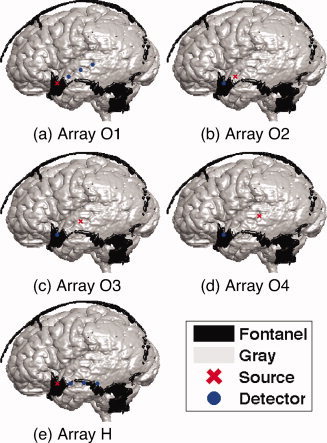

One source and three detectors were placed on the left temporal area in order to cover part of the temporal fontanel. Monte Carlo simulations of photon propagation were performed with two different optical array configurations in either a horizontal (array H from Fig. 1e) or an oblique direction. In the oblique array configuration, the position of the source was shifted by 10 mm from O1 to O4 as shown in Figure 1a–d.

Figure 1.

Optical array configurations: (a)–(d) oblique (O1–O4) and (e) horizontal (H) arrays with a distance of 10, 20, or 30 mm between sources and detectors. In the oblique arrays, the position of the source is permuted by 10 mm from O1 to O4. Sources and detectors are shown in red crosses and blue dots, respectively. Gray matter and fontanel tissues are shown in gray and black, respectively. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

Regions of Activation

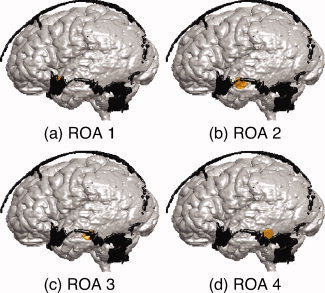

Four different positions of the region of activation (ROA) were simulated. The center of the ROA was shifted by 10 mm from case 1 to 4 as shown in Figure 2a–d, respectively. The ROA was a half‐sphere with a radius of 5 mm similar to that defined in Heiskala et al. (2009). Regions of activation included both gray and white matter voxels in which the absorption coefficients were subject to change. In the NIR spectrum for wavelengths from 650 to 950 nm, the dominant chromophores in tissues are oxyhemoglobin (HbO) and deoxyhemoglobin (HbR). Assuming that changes in hemoglobin concentration during cerebral activation correspond to an increase in HbO of 9 μmol/L and a decrease in HbR of 3 μmol/L (Huppert et al.,2006), change in absorption Δμa were computed such that

| (1) |

where E HbO(λ) and E HbR(λ) are the extinction coefficients at wavelength λ (Prahl,2002). According to Equation (1), change in absorption Δμa = 1.2 × 10−3 mm−1 was simulated in both gray and white matter voxels.

Figure 2.

(a)–(d) Regions of activation (ROA) 1–4. Each ROA is separated by an interval of 10 mm from anterior to posterior. Gray matter, fontanel, and region of activation are shown in gray, black and yellow, respectively. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

Monte Carlo Simulations

All simulations were performed using a Monte Carlo technique described in (Boas et al.,2002; Wang et al.,1995). This technique simulates light propagation in the segmented neonatal head models with spatially varying optical properties for each tissue (see Table I). The modulation frequency was zero, and emitted light was simulated at 800 nm (Fukui et al.,2003). Light propagation was simulated in the two anatomical models for baseline and activated optical properties. One hundred million photon packets were launched from the source for all simulations (Boas et al.,2002; Heiskala et al.,2009).

Quantitative Recovery of Change in Absorption

The modified Beer–Lambert law was used to quantify the effect of the fontanel on NIRS measurements. The light intensity ϕ(λ) for a particular wavelength λ is generally a function of the absorption coefficient μa(λ) such that

| (2) |

where ϕ0(λ) is the initial light intensity and DPL(λ) is the differential pathlength (Cope and Delpy,1988; Delpy et al.,1988). The Monte Carlo method allowed tracking of each photon in each tissue type providing quantified and accurate DPL(λ) (Boas et al.,2002). The modified Beer–Lambert law [Eq. (2)] can be written for a set of M discrete volume elements (i.e., voxels r j) and the sensitivity map between a source (r ) and a detector (r ) position can be computed from the Rytov approximation (Arridge, 1999; Boas et al.,2004), such that

| (3) |

for the ith measurement. Synthetic measurements were generated only with the anatomical model including the fontanel to mimic a real experimental measurement and change in optical density (ΔODF) was then computed with

| (4) |

where subscripts A and B represent “activation” and “baseline” state, respectively, while superscript F means “fontanel” (there is no measurement generated from the model with no fontanel). Changes in absorption (Δμa) were then recovered using baseline partial pathlength PPLB of detected light only in the ROA (Hiraoka et al.,1993) for both anatomical head models, such that

| (5) |

where the superscript NF means “no fontanel.”

RESULTS

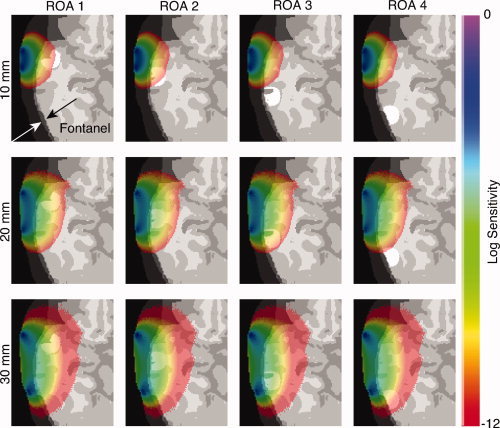

Figure 3 depicts an axial view of the sensitivity map superimposed on the anatomical head model including the fontanels, which are described as cartilage. The rows correspond to the source‐detector channels of 10, 20, and 30 mm while the columns represent the region of action 1–4 (in white) for the horizontal configuration. The thickness of the skull and the fontanel are similar (1.5 – 2.5 mm), but the distribution of the fontanel is not uniform in the temporal area. Arrows in the top left image indicate a relevant part of the fontanel. Sensitivity maps are shown for a magnitude of 60 dB in signal loss (Boas et al.,2002; Culver et al.,2005). High (respectively, low) values are mapped by violet (respectively, red) voxels. Computing these sensitivity maps validated the selection of the source‐detector channels shown subsequently in Figures 4 and 5. To ensure that a significant number of photons have experienced the absorption change, the sensitivity map must spatially include the ROA concerned. Figure 3 (first row) shows that ROAs 3 and 4 are not included in the sensitivity maps for the source‐detector distance of 10 mm. A similar result was also observed (second row) for the source‐detector distance of 20 mm with respect to ROA 4. In these particular cases, the change in absorption Δμa is very small indicating almost no difference between activated and baseline state. These optical channels were not included in the subsequent analysis. Conversely, Figure 3 (third row) shows that a distance of 30 mm between the source and the detector is sufficient for the sensitivity maps to include each ROA.

Figure 3.

Sensitivity maps superimposed on the anatomical model including the fontanel with the region of activation shown in white. Rows correspond to the source‐detector distances and columns represent the regions of activation. All sensitivity maps correspond to a magnitude of 60 dB of signal loss. As indicated by the color code bar on the right, sensitivity is coded from red for low values to violet for high values. Arrows in top left image indicate a relevant part of the fontanel. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

Figure 4.

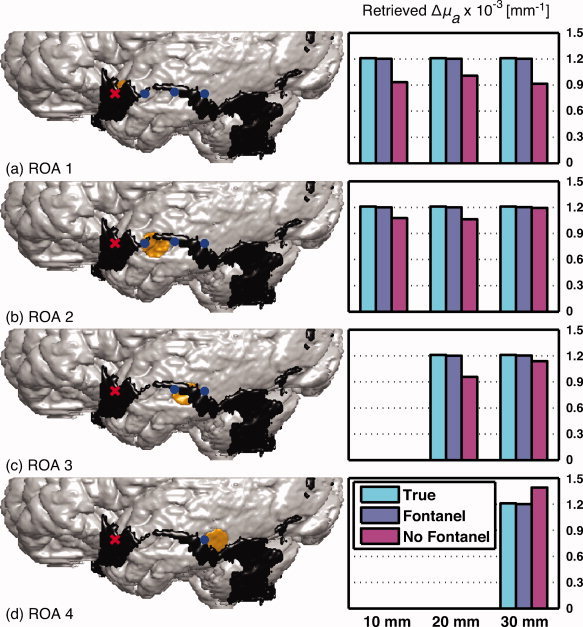

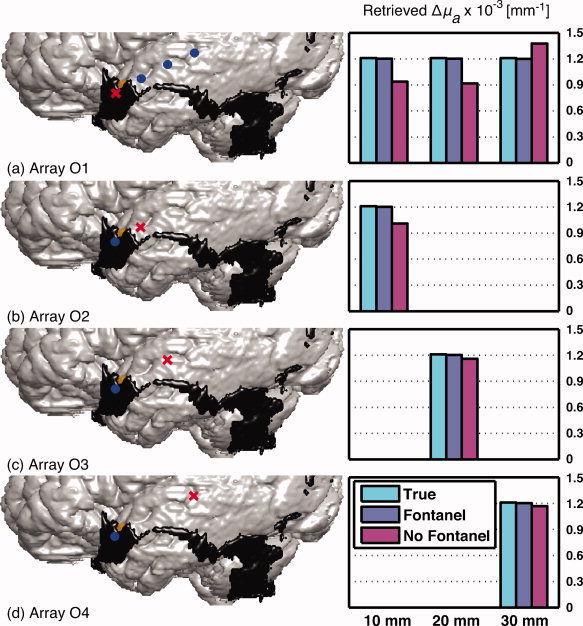

(a)–(d) 3D anatomical representation of the segmented gray matter, the fontanel and the region of activation superimposed by the optical array (left panel). Corresponding recovered changes in absorption computed for the horizontal optical array H with respect to regions of activation 1–4, respectively (right panel). The values represented in the column diagrams on the right correspond to the source‐detector distances. Three values are depicted: (cyan) the true change (1.2 × 10−3 mm−1) simulated in the region of activation, (purple) the recovered change in absorption Δμ estimated with the head model describing the fontanel, and (magenta) the recovered change in absorption Δμ estimated with no fontanel. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

Figure 5.

(a)–(d) 3D anatomical representation of the segmented gray matter, the fontanel and the region of activation superimposed by the optical array (left panel). Corresponding recovered changes in absorption computed for the oblique optical arrays O1–O4 with respect to region of activation 1, respectively (right panel). The values represented in the column diagrams on the right correspond to the source‐detector distances. Three changes in absorption are presented: (cyan) the true change (1.2 × 10−3 mm−1) simulated in ROA 1, (purple) the recovered change in absorption using the model in which the fontanel was modeled, and (magenta) the recovered change in absorption using the model with no fontanel. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

Recovered changes in absorption Δμa are shown in Figure 4 for different regions of activation and Figure 5 in which the source position was moved. In each figure, panel (a)–(d) presented the combination of a 3D sagittal view of the fontanel (black) and the ROA (in yellow) superimposed by the optical array (left image) and the corresponding recovered changes in absorption (right bar graph). Red crosses and blue dots represented sources and detectors, respectively. The graph illustrated three different changes in absorption: (cyan) the true change (1.2 × 10−3 mm−1) simulated in the ROA, (purple) the recovered change in absorption Δμ estimated with the head model describing the fontanel, and (magenta) the recovered change in absorption Δμ estimated with no fontanel. For each panel, source‐detector channels were selected according to the previous sensitivity analysis. In both figures, recovered changes were generally underestimated with respect to the true value. Correction factors were computed by the ratio of the true and recovered change in absorption and are provided in Table III. A value around 1 means an accurate recovery.

Table III.

Correction factors (no unit) computed by the ratio between the true and the recovered change in absorption for optical configurations detailed in Figures 4 and 5

| Fontanel | No Fontanel | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Optical configuration | Reference | 10 mm | 20 mm | 30 mm | 10 mm | 20 mm | 30 mm |

| ROA 1 |

Figure 4a |

1.01 | 1.01 | 1.01 | 1.30 | 1.20 | 1.32 |

| ROA 2 |

Figure 4b |

1.01 | 1.01 | 1.01 | 1.12 | 1.14 | 1.01 |

| ROA 3 |

Figure 4c |

— | 1.01 | 1.01 | — | 1.26 | 1.06 |

| ROA 4 |

Figure 4d |

— | — | 1.01 | — | — | 0.87 |

| Array O1 |

Figure 5a |

1.01 | 1.01 | 1.01 | 1.29 | 1.32 | 0.88 |

| Array O2 |

Figure 5b |

1.01 | — | — | 1.20 | — | — |

| Array O3 |

Figure 5c |

— | 1.01 | — | — | 1.05 | — |

| Array O4 |

Figure 5d |

— | — | 1.01 | — | — | 1.04 |

In Figure 4a–d, recovered change in absorption with the head model including the fontanel is ∼99% of the true change, but between 75 and 94% with no fontanel (excluding situation distance of 30 mm from ROA 2 in Fig. 4d). Corresponding correction factors in the presence of the fontanel are roughly 1.01, while from 0.85 to 1.32 with the model in which the fontanel was not described. Globally, the recovery was more accurate when the fontanel was described in the head model.

Figure 5a–d presents change in absorption recovered when the position of the source was moved in an oblique anterior–posterior direction. These changes represented 99% of the true change when using the model describing the fontanel while ranged between 75 and 96% when the fontanel was not taken into account. Corresponding correction factors computed when the fontanel was modeled are around 1.01 while from 0.87 to 1.32 with no fontanel.

In Table IV, correction factors are shown in the situation where two foci of activation were simultaneously considered. Two cases are presented: ROAs 1 and 3 and ROAs 2 and 4. When retrieved with the model including the fontanel, change in absorption was generally 99% of the true change, whereas between 77 and 99% for the head without fontanel.

Table IV.

Correction factors (no unit) computed for optical configurations combining two foci: ROAs 1 and 3 and ROAs 2 and 4, respectively

| Fontanel | No Fontanel | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Optical configuration | Reference | 10 mm | 20 mm | 30 mm | 10 mm | 20 mm | 30 mm |

| ROAs 1 and 3 | — | 1.01 | 1.01 | 1.01 | 1.30 | 1.23 | 1.10 |

| ROAs 2 and 4 | — | 1.01 | 1.01 | 1.01 | 1.12 | 1.14 | 1.01 |

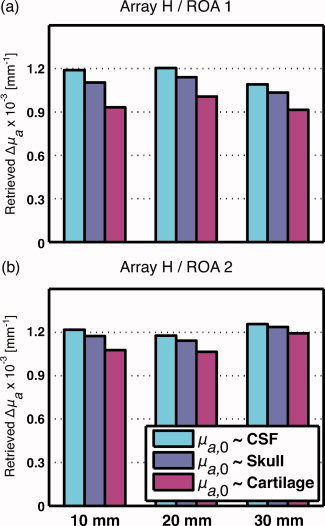

Figure 6 depicts two histograms showing recovered optical absorption coefficients Δμ at distances of 10, 20, and 30 mm (x‐axis) when the horizontal optical array and regions of activation 1 and 2 were simulated. Three different sets of baseline optical absorption coefficients of the fontanel from Table II were compared (bars) when simulating the photon propagation. Recovered changes decrease as baseline coefficient of absorption of the fontanel is modified from low to high value, i.e., from set A (CSF‐like), through set B (skull‐like), to set C (cartilage‐like).

Figure 6.

Recovered brain absorption coefficients Δμ computed with the horizontal optical array H and regions of activation 1 and 2, respectively. Recovered values are shown with respect to the optical absorption of the fontanel taken from set A (CSF‐like), B (skull‐like), and C (cartilage‐like) from Table II. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

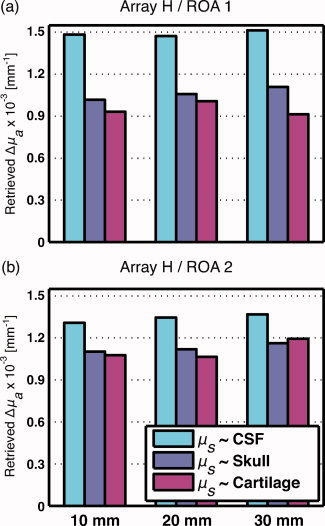

The effect of modifying the scattering coefficient of the fontanel was investigated by considering three different values (Table II) corresponding to CSF, skull, and cartilage tissues (Fig. 7). Change in absorption Δμ was retrieved for ROA 1 and 2 for the horizontal optical configuration H. When considering the fontanel as a low‐scattering tissue (CSF‐like), retrieved change in absorption was overestimated compared to underestimated for both skull‐ and cartilage‐like scattering coefficients.

Figure 7.

Recovered brain absorption coefficients Δμ computed with the horizontal optical array H and regions of activation 1 and 2, respectively. Scattering coefficients of the fontanel were taken from set A (CSF‐like), B (skull‐like), and C (cartilage‐like) from Table II to recover absorption changes. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

DISCUSSION

Recovery Improved With the Model Including the Fontanel

The methodology (Dehaes et al.,2011; Strangman et al.,2003) used in this study demonstrated its ability to recover change in absorption whether the fontanel was modeled in the head model or not. Recovered change in absorption was better estimated when using the head model including the fontanel than with the model in which the fontanel was not described. This result was illustrated in Figures 4 and Figure 5 and Tables III and IV, showing the benefit of describing the fontanel in the anatomical head model. When the fontanel was taken into account, the change in absorption was recovered at a maximum of 99% of the true change (1.2 × 10−3 mm−1) while between 75 and 99% with no fontanel. Globally, correction factors were lower when the fontanel was modeled. This observation was also found when considering multifoci activation. These results demonstrated the necessity of modeling the fontanel when performing a NIRS study in the temporal lobe within neonates.

The recovering method presented in this study was based on the computation of a change in absorption due to perturbing the baseline state (Strangman et al.,2003). The change in absorption in the ROA was assumed uniform (1.2 × 10−3 mm−1) but in fact, the brain activation is occurring in a small‐localized volume of tissue with a spatially nonconstant intensity (Boas et al.,2004). In general, this volume is unknown and the true pathlength strongly depends on the source and the detector positions, the optical properties of the tissues traversed by the light and their anatomical descriptions. In a simulation configuration as in this study, these parameters are known and the sensitivity analysis (Fig. 3) provides information of the spatial distribution of the light in the segmented tissues allowing the selection of the source‐detector separations. The Monte Carlo method (Boas et al.,2002) also helps to estimate this pathlength with more precision by tracking each photon in each voxel. Therefore, simulation work performed prior the experimentation might help in designing the optical probe and the study protocol.

Limitations and Future Work

Because of progressive ossification of the neonatal fontanel, the shape and site of the fontanel vary in time and can prevent longitudinal analysis during the development of the infant. The method developed in this study could potentially be used in other specific cortical areas, underlying other fontanels (e.g., the anterior fontanel) by using similar optical arrays. However, pathlengths and recovered absorption coefficients as well as correction factors provided in this study are only valid for this particular anatomical structure and for the set of optical properties as well as for optical configurations tested. Although there is variability in the size and shape of the head as well as in tissue description in neonates, we think that error would have a similar trend when considering another head model of age matched.

This study only reports correction factors and errors in comparisons with and without the fontanel. There is no relationship established by using real NIRS measurements. However, the fontanel was anatomically described with accurate and real CT and MR imaging data from a neonate.

The choice of the segmentation technique used in this study was justified by our previous work (Kazemi et al.,2007,2009a,b). Because there is no gold standard segmentation tool for application in neonatal population, the use of existing tools, generally suited for adult application, was selected. It is difficult to measure quantitatively the quality of the process and therefore, possible segmentation errors may occur. We also considered tissue as piecewise homogeneous volume but this not necessarily true.

Future studies are needed to investigate the absorption recovery by varying the refractive index, as the water content of cartilage is higher than that of bone (Youn et al.,2000). In addition, the use of a high‐density grid should improve the recovery by increasing the number of multidistance measurements (Heiskala et al.,2009). However, the random effects of noise may have significant effect on the reconstructed changes in absorption even with a large number of measurements.

CONCLUSIONS

Over the last two decades, significant improvements have been made in the field of neonatal brain imaging using NIRS. These advances have also contributed to a reduction of neonatal morbidity, which has been achieved due to the combined efforts undertaken by neuroscience research and clinical practice. In particular, NIRS has provided a major contribution to the understanding of cerebral oxygenation in neonates. Therefore, it is important to define the limits of this technique.

In this study, we investigated the effect of the fontanel on NIRS measurements. The results showed that the fontanel had an influence on the recovered changes in absorption. The correction factor was lower when the head model included the fontanel tissue than when it did not. Published results concerning the impact of the fontanel on electrical propagation in preterm infants (Roche‐Labarbe et al.,2008a) also apply to photon propagation. As expected, the fontanels interact with photons, which should therefore be taken into account in studies designed to localize the origin of local hemodynamic changes.

REFERENCES

- Ashburner J, Friston K ( 2005): Unified segmentation. Neuroimage 26: 839–851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartocci M, Winberg J, Papendieck G, Mustica T, Serra G, Lagercrantz H ( 2001): Cerebral hemodynamic response to unpleasant odors in the preterm newborn measured by near‐infrared spectroscopy. Pediatr Res 50: 324–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartocci M, Winberg J, Ruggiero C, Bergqvist L, Serra G, Lagercrantz H ( 2000): Activation of olfactory cortex in newborn infants after odor stimulation: A functional near‐infrared spectroscopy study. Pediatr Res 48: 18–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartolomei F, Chauvel P, Wendling F ( 2008): Epileptogenicity of brain structures in human temporal lobe epilepsy: A quantified study from intracerebral EEG. Brain 31( Pt 7): 1818–1830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boas D, Dale A, Franceschini M ( 2004): Diffuse optical imaging of brain activation: Approaches to optimizing image sensitivity, resolution, and accuracy. Neuroimage 23: S275–S288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boas D, Culver J, Scott J, Dunn A ( 2002): Three dimensional Monte Carlo code for photon migration through complex heterogeneous media including the adult human head. Opt Express 10: 159–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brazy J, Lewis D, Mitnick M, Jöbsis vander Vliet F ( 1985): Noninvasive monitoring of cerebral oxygenation in preterm infants: Preliminary observations. Pediatrics 75: 217–225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bortfeld H, Wruck E, Boas D ( 2007): Assessing infants' cortical response to speech using near‐infrared spectroscopy. Neuroimage 34: 407–415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bortfeld, H , Fava, E , Boas, D ( 2009). Identifying cortical lateralization of speech processing in infants using near‐infrared spectroscopy. Dev Neuropsychol 34: 52–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collignon A, Maes F, Delaere D, Vandermeulen D, Suetens P, Marchalet G ( 1995): Automated multi‐modality image registration based on information theory. Info Proc Info Process Med Imaging (IPMI'95): 263–274. [Google Scholar]

- Cope M, Delpy D ( 1988): System for long‐term measurement of cerebral blood and tissue oxygenation on newborn infants by near infra‐red transillumination. Med Biol Eng Comp 26: 289–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culver J, Siegel A, Franceschini M, Mandeville J, Boas D ( 2005): Evidence that cerebral blood volume can provide brain activation maps with better spatial resolution than deoxygenated hemoglobin. Neuroimage 27: 947–959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehaes M, Gagnon L, Lesage F, Pélégrini‐Issac M, Vignaud A, Valabrègue R, Grebe R, Wallois F, Benali H ( 2011): Quantitative investigation of the effect of the extra‐cerebral vasculature in diffuse optical imaging: A simulation study. Biomed Opt Express 2: 680–695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delpy D, Cope M, van der Zee P, Arridge S, Wray S, Wyatt J ( 1988): Estimation of optical pathlength through tissue from direct time of flight measurement. Phys Med Biol 33: 1433–1442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukui Y, Ajichi Y, Okada E ( 2003): Monte Carlo prediction of near‐infrared light propagation in realistic adult and neonatal head models. Appl Optics 42: 2881–2887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heiskala J, Hiltunen P, Nissilä I ( 2009). Significance of background optical properties, time‐ resolved information and optode arrangement in diffuse optical imaging of term neonates. Phys Med Biol 54: 535–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gervain J, Macagno F, Cogoi S, Peña M, Mehler J ( 2008) The neonate brain detects speech structure. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 14222–14227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hintz S, Cheong W‐F, van Houten JP, Stevenson DK, Benaron DA ( 1999) Bedside imaging of intracranial hemorrhage in the neonate using light: Comparison with ultrasound, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging. Pediatr Res 45: 54–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebden JC, Gibson AP, Yusof RM, Everdell N, Hillman EM, Delpy DT, Austin T, Meek J, Wyatt JS ( 2002) Three‐dimensional optical tomography of the premature infant brain. Phys Med Biol 47: 4155–4166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiraoka M, Firbank M, Essenpreis M, Cope M, Arridge S, van der Zee P, Delpy D ( 1993) A Monte Carlo investigation of optical pathlength in inhomogeneous tissue and its application to near‐infrared spectroscopy. Phys Med Biol 38: 1859–1876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huppert T, Hoge R, Diamond S, Franceschini M, Boas D ( 2006): A temporal comparison of BOLD, ASL, and NIRS hemodynamic responses to motor stimuli in adult humans. Neuroimage 29: 368–382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jöbsis F, ( 1977) Noninvasive, infrared monitoring of cerebral and myocardial oxygen sufficiency and circulatory parameters. Science 198: 1264–1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karen T, Morren G, Haensse D, Bauschatz A, Bucher H, Wolf M ( 2008): Hemodynamic response to visual stimulation in newborn infants using functional near‐infrared spectroscopy. Hum Brain Mapp 29: 453–460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazemi K, Gadimi S, Abrishami Moghaddam H, Grebe R, Wallois F, Golshaeyan N, Gondry‐Jouet C ( 2009a): Automatic model based brain and CSF extraction from structural neonatal MR images. Neuroimage 47(Supplement 1):S50.

- Kazemi K, Gadimi S, Lyaghat A, Tarighati A, Golshaeyan N, Abrishami Moghaddam H, Grebe R, Gondry‐Jouet C, Wallois F ( 2009b): Automatic fontanel extraction from newborn's CT images using variational level set. CAIP, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, Volume 5702/2009, 639–646.

- Kazemi K, Abrishami Moghadam H, Grebe R, Gondary‐Jouet C, Wallois F ( 2007): A neonatal atlas template for spatial normalization of whole‐brain magnetic resonance images of newborns: Preliminary results. Neuroimage 37: 463–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotilahti K, Nissilä I, Näsi T, Lipiäinen L, Noponen T, Meriläinen P, Huotilainen M, Fellman V ( 2010): Hemodynamic responses to speech and music in newborn infants. Hum Brain Mapp 31: 595–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larroque B, Bréart G, Kaminski M, Dehan M, André M, Burguet A, Grandjean H, Ledésert B, Lévêque C, Maillard F, Matis J, Rozé JC, Truffert P, Epipage study group ( 2004): Survival of very preterm infants: Epipage, a population based cohort study. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 89: F139–F144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minagawa‐Kawai Y, Mori K, Naoi N, Kojima S ( 2007). Neural attunement processes in infants during the acquisition of a language‐specific phonemic contrast. J Neurosci 27: 315–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meek JH, Firbank M, Elwell CE, Atkinson J, Braddick O, Wyatt JS ( 1998): Regional hemodynamic responses to visual stimulation in awake infants. Pediatr Res 43: 840–843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peña M, Maki A, Kovacić D, Dehaene‐Lambertz G, Koizumi H, Bouquet F, Mehler J ( 2003): Sounds and silence: An optical topography study of language recognition at birth. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 11702–11705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prahl S ( 2002): Optical absorption of hemoglobin. Available at: http://omlc.ogi.edu/spectra/hemoglobin/

- Prastawa M, Gilmore J, Lin W, Gerig G ( 2005): Automatic segmentation of MR images of the developing newborn brain. Med Image Anal 9: 457–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roche‐Labarbe N, Aarabi A, Kongolo G, Gondry‐Jouet C, Dümpelmann M, Grebe R, Wallois F ( 2008a): High‐resolution electroencephalography and source localization in neonates. Hum Brain Mapp 29: 167–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roche‐Labarbe N, Zaaimi B, Nehlig A, Berquin P, Grebe R, Wallois F ( 2008b): NIRS‐measured oxy‐and deoxyhemoglobin changes associated with EEG spike and waves discharges in children. Epilepsia 49: 1871–1880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strangman G, Franceschini MA, Boas D.A ( 2003): Factors affecting the accuracy of near‐infrared spectroscopy concentration calculations for focal changes in oxygenation parameters. Neuroimage 18: 865–879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Zee P, Cope M, Arridge SR, Essenpreis M, Potter LA, Edwards AD, Wyatt JS, McCormick DC, Roth SC, Reynolds EOR, Delpy DT ( 1991): Experimentally measured optical pathlengths for the adult head, calf and forearm and the head of the newborn infant as a function of inter‐optode spacing. Adv Exp Med Biol 316: 143–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Zee P, Essenpreis M, Delpy, D.T ( 1993): Optical properties of brain tissue. Proceedings of SPIE 1888: 454–465. [Google Scholar]

- Villringer A, Planck J, Hock C, Schleinkofer L, Dirnagl U ( 1993): Near infrared spectroscopy (NIRS): A new tool to study hemodynamic changes during activation of brain function in human adults. Neurosci Lett 154: 101–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallois F, Mahmoudzadeh M, Patil A, Grebe R ( 2011): Usefulness of simultaneous EEG–NIRS recording in language studies. Brain Lang, doi:10.1016/j.bandl.2011.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallois F, Patil A, Héberlé C, Grebe R ( 2010): EEG‐NIRS in epilepsy in children and neonates. Neurophysiol Clin 40: 281–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallois F, Patil A, Kongolo G, Goudjil S, Grebe R ( 2009): Haemodynamic changes during seizure‐like activity in a neonate: A simultaneous AC EEG‐SPIR and high‐resolution DC EEG recording. Neurophysiol Clin 39: 217–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Jacques S, Zheng L ( 1995): MCML‐Monte Carlo modeling of light transport in multi‐layered tissues. Comput Methods Programs Biomed 47: 131–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youn J, Telenkov S, Kim E, Bhavaraju N, Wong B, Valvano J, Milner T ( 2000): Optical and thermal properties of nasal septal cartilage. Laser Surg Med 27: 119–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaramella P, Freato F, Amigoni A, Salvadori S, Marangoni P, Suppjei A, Schiavo B, Chiandetti L ( 2001): Brain auditory activation measured by near‐infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) in neonates. Pediatr Res 49: 213–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]