Abstract

Gestures are an important component of interpersonal communication. Especially, complex multimodal communication is assumed to be disrupted in patients with schizophrenia. In healthy subjects, differential neural integration processes for gestures in the context of concrete [iconic (IC) gestures] and abstract sentence contents [metaphoric (MP) gestures] had been demonstrated. With this study we wanted to investigate neural integration processes for both gesture types in patients with schizophrenia. During functional magnetic resonance imaging‐data acquisition, 16 patients with schizophrenia (P) and a healthy control group (C) were shown videos of an actor performing IC and MP gestures and associated sentences. An isolated gesture (G) and isolated sentence condition (S) were included to separate unimodal from bimodal effects at the neural level. During IC conditions (IC > G ∩ IC > S) we found increased activity in the left posterior middle temporal gyrus (pMTG) in both groups. Whereas in the control group the left pMTG and the inferior frontal gyrus (IFG) were activated for the MP conditions (MP > G ∩ MP > S), no significant activation was found for the identical contrast in patients. The interaction of group (P/C) and gesture condition (MP/IC) revealed activation in the bilateral hippocampus, the left middle/superior temporal and IFG. Activation of the pMTG for the IC condition in both groups indicates intact neural integration of IC gestures in schizophrenia. However, failure to activate the left pMTG and IFG for MP co‐verbal gestures suggests a disturbed integration of gestures embedded in an abstract sentence context. This study provides new insight into the neural integration of co‐verbal gestures in patients with schizophrenia. Hum Brain Mapp, 2013. © 2012 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

Keywords: co‐verbal gestures, metaphoric gestures, iconic gestures, integration, schizophrenia

INTRODUCTION

Gestures are an important component of interpersonal communication [McNeill, 1992] and have a huge impact on speech perception [Kelly et al., 2010; Wu and Coulson, 2010], memory [Straube et al., 2009,2011b] and their underlying brain processes [Dick et al., 2009; Green et al., 2009; Kircher et al., 2009; Ozyurek et al., 2007; Straube et al., 2009,2010,2011a,b; Willems and Hagoort, 2007; Willems et al., 2007,2009]. There is evidence suggesting that patients with schizophrenia have dysfunctions in the perception and production of gestures [Bucci et al., 2008; Grüsser et al., 1990; Matthews et al., 2011]. However, up to now gesture perception and especially the neural correlates of speech and gesture integration in schizophrenia received very little attention.

The ability to combine information from multiple sensory modalities into a single, unified percept is a key element in an person's ability to interact with the external world [Stevenson et al., 2011]. Even on low complexity levels, e.g., integrating articulatory lip movements with the auditory speech input (phonological), it has been shown that patients with schizophrenia have a deficit in combining visual and auditory information (e.g., congruent vs. incongruent lip movements, facial expression; Surguladze et al., 2001; Szycik et al., 2009). It was suggested that abnormalities in the structure and function of brain regions involved in multimodal processing provide a possible common etiology for integration deficits seen in a number of clinical populations, including individuals with autism spectrum disorder, dyslexia, and schizophrenia [Stevenson et al., 2011]. Although lip movements transport predominantly phonetic information, gestures performed by arms and hands predominantly communicate semantic information [McNeill, 1992]. This is especially true for gestures in context of abstract sentences [Straube et al., 2011a]. However, extraction of such semantic information of speech and gesture might require intact processing of complex actions, which also has been shown to be impaired in patients with schizophrenia [Takahashi et al., 2010]. Although all this evidence suggests that patients with schizophrenia would also show dysfunctions in the comprehension of meaningful arm/hand gestures in context of speech, the neural correlates of speech–gesture integration in patients with schizophrenia are unknown.

There is an increasing evidence that language and gesture comprehension in healthy subjects rely on partially overlapping brain networks (for a review, see Willems and Hagoort, 2007; Xu et al., 2009). Recent functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) investigations in healthy subjects have focused on the interaction between speech and gesture, using different types of speech‐associated gestures such as beat gestures, emblematic gestures, iconic (IC) gestures and metaphoric (MP) gestures [Green et al., 2009; Holle et al., 2008,2010; Hubbard et al., 2009; Kircher et al., 2009; Straube et al., 2009,2010,2011a,b; Willems et al., 2007,2009]. Different types of gestures vary in their relation to language [McNeill, 1992]. IC gestures refer to the concrete content of sentences, whereas MP gestures illustrate abstract information. For example, in the sentences “He gets down to business” (drop of the hand) or “The politician builds a bridge to the next topic” (depicting an arch with the hand), abstract content is illustrated by a MP gesture. However, the same gestures can be IC (drop of the right hand or depicting an arch with the right hand) when paired with the sentences “The man goes down the hill” or “There is a bridge over the river” as they illustrate concrete physical features of the world [Straube et al., 2011a].

In a previous fMRI study in healthy subjects, we demonstrated common and unique integration processes related to the integration of IC and MP gestures [Straube et al., 2011a]. Although the posterior temporal cortex was involved in the integration of both gesture types, the left inferior frontal gyrus (IFG) was specifically related to the integration of MP co‐verbal gestures. Activation of the IFG may be interpreted as an unification process [Hagoort et al., 2009] responsible for making inferences [e.g., Bunge et al., 2009], relational reasoning [e.g., Wendelken et al., 2008] and the building of analogies [e.g., Bunge et al., 2005; Green et al., 2006a,b; Luo et al., 2003]. Those processes may also be involved in the comprehension of metaphors or ambiguous communications and consistently activate the left IFG [Eviatar and Just, 2006; Rapp et al., 2004,2007; Stringaris et al., 2007]. In contrast, integration within the posterior temporal lobe appears to rely more on perceptual matching processes, such as those that are engaged in the identification of tool sounds [Amedi et al., 2005; Beauchamp et al., 2004,2008; Lewis, 2005,2006], action words [e.g., Kable and Chatterjee, 2006; Kable et al., 2005] or high familiar and over‐learned stimulus associations [Hein et al., 2007; Naumer et al., 2009]. These representations may be readily available in memory [Hagoort et al., 2009]. As supported by an increasing number of studies in healthy subjects integration processes occurring in posterior temporal areas seem to be sufficient for the semantic integration of IC gestures in the context of concrete sentences [Green et al., 2009; Holle et al., 2008,2010; Straube et al., 2011a]. For the processing of MP co‐verbal gestures, in contrast, constructive unification processes related to the IFG seem to be necessary [Kircher et al., 2009; Straube et al., 2009,2011a].

A main feature of thought and language disturbance in schizophrenia is concretism, i.e., the inability to understand the figurative meaning of proverbs or metaphors, humor or abstract concepts [de Bonis et al., 1997; Kircher et al., 2007]. Concretism has been related to dysfunctions in the left IFG [Kircher et al., 2007]. Thus, besides the assumption of a general dysfunction in gesture production and comprehension in patients with schizophrenia [Berndl et al., 1986; Bucci et al., 2008; Martin et al., 1994,2006; Troisi et al., 1998], one may assume that integration processes related to abstract utterances accompanied by MP gestures are disturbed in schizophrenia.

In this study, we directly compared the processing of videos of natural IC and MP co‐verbal gestures in patients with schizophrenia. To investigate bimodal processing we compared the bimodal speech and gesture items with unimodal control conditions. Thus, in the context of this study we define integration as the increased neural activity due to bimodal (as opposed to unimodal) processing of speech and gesture. The paradigm has previously been applied in healthy participants [Straube et al., 2011a]. In that study, two different integration processes were related to two distinct brain regions: perceptual matching to the posterior temporal lobe and unification to the left IFG [Hagoort et al., 2009]. Applying this paradigm in patients with schizophrenia allows for disentangling the contributions of these two different neural correlates in distinct integration processes.

Despite some reports about dysfunctional integration of visual and auditory information in patients with schizophrenia that was shown on predominantly phonological levels [Surguladze et al., 2001; Szycik et al., 2009], we hypothesized that perceptual matching processes are basically intact in patients with schizophrenia. Therefore, we expected that the integration of concrete speech semantic and IC gestures in patients with schizophrenia – similar to the results of the healthy subject sample – mainly relies on integration processes located in the posterior temporal lobe [Green et al., 2009; Holle et al., 2008,2010; Straube et al., 2011a]. In contrast to intact perceptual matching processes for the processing of IC gestures, we hypothesized that unification processes necessary for the integration of MP gestures are disturbed in patients with schizophrenia. Consequently, we anticipated that the processing of MP gestures will not show increased neural activity in response to bimodal (as opposed to unimodal) processing of speech and gestures especially in inferior frontal brain regions [Kircher et al., 2009; Kircher et al., 2007; Straube et al., 2011a].

METHODS

Participants

Sixteen patients (six female) diagnosed with schizophrenia (F20) participated in the study (mean age = 38 years, range: 19–53 years). Patients were recruited from and diagnosed by clinicians according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition (DSM‐IV) criteria at the Department of Psychiatry, Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, RWHT Aachen University Hospital, Germany.

All participants were free of visual and auditory deficits, additional neurological and medical impairments as well as any cerebral abnormality, as assessed by a T1‐weighted MRI. All patients reported that they were right handed and German was their primary language. Symptom ratings in patients were recorded using the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS; Kay et al., 1987) and the Schedule for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS; Andreasen, 1984) and Negative Symptoms (SANS; Andreasen, 1983). The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the RWTH Aachen University. All participants gave written informed consent and were paid 20 Euro for participation.

Clinical characteristics

Patients were moderately ill with an average total PANSS score of 64 (SD = 19), with positive subscore of 16 (SD = 8), negative subscore of 16 (SD = 7) and general subscore of 32 (SD = 9). Symptoms as assessed by the (SAPS) scored 37 (SD = 27) and by the SANS scored 22 (SD = 27). All patients were on stable doses of atypical antipsychotic medication (mean dose in Haloperidol equivalents = 9.62 mg/day, SD = 4.26; Andreasen et al., 2010).

Healthy control group

The 16 patients were compared with 16 healthy controls, previously published in Human Brain Mapping [Straube et al., 2011a]. Sixteen right‐handed healthy male volunteers participated in this previous study, all native German speakers (mean age = 27.9 years, range: 19–47 years) with no impairments of vision or hearing. None of the participants had any medical, neurological or psychiatric illness, past or present. All participants gave written informed consent and were paid 20 Euro for participation. The study was approved by the local ethics committee.

Stimulus Construction

The stimulus material consisted of video clips (each with a duration of 5 s) that presented an actor performing different combinations of speech and gestures (for detailed description see Straube et al., 2011a): (1) IC co‐verbal gestures (concrete sentence content), (2) MP co‐verbal gestures (MP; abstract sentence content) and two control conditions including (3) sentences without gestures (S; concrete sentence content) and (4) gestures without sentences (G). The gestures in the IC condition illustrate the form, size or movement of something concrete that is mentioned in the accompanying speech [McNeill, 1992], whereas those in the MP condition illustrate the form, size or movement of something abstract that is mentioned in the associated speech [McNeill, 1992]. The sentences in the control condition (S) are similar to the concrete sentences accompanied by IC gestures. Concrete sentences were used to control for general speech input processing. The G condition contains isolated gestures that were naturally associated with concrete sentence content, i.e., IC.

A male actor was instructed to speak each sentence in combination with the associated gesture in the IC and MP conditions and without any arm or hand movement in the S condition. Sentences of this paradigm were selected to be easy to understand and conventional to ensure that comprehension is feasible even in patients groups.

Experimental Design

Thirty stimuli from each of the four experimental conditions were presented in a block design. Each block consisted of five videos of the same condition and was 25 s in length (5 videos × 5 s). In total, six blocks of each condition were presented in a pseudorandomized order and separated by a baseline condition (grey background with a fixation cross) with a duration of 15 s, during which the fixation cross shortly disappeared two times (about every 5 s). Although scanning each participant saw 120 video clips which lasted 17 min in total.

Subjects were instructed to watch the videos and to respond each time they saw a new picture appear (either the video or baseline fixation cross) by pressing a button with the left index finger. This was done to ensure that they paid attention during all conditions and baseline. This implicit encoding task was chosen to focus participants' attention on the middle of the screen and enabled us to investigate implicit speech and gesture processing. Before the scanning session each participant was administered at least 10 practice trials outside the scanner that were different from those used in the experiment. During the overview scans, additional clips were presented to adjust the volume so that the sentences could be well heard. Presentation software (Version 9.2, 2005) was used for stimulus presentation and response measurement in the fMRI experiment.

After the fMRI experiment, half of the patients performed a comprehension task to test adequate understanding of the presented videos. All videos of the fMRI experiment were presented again and the patients had to explain the meaning of each single video to the experimenter. The experimenter documented each response and rated its appropriateness on the following scale: (1) Complete and correct understanding, (2) unclear or partly correct description, and (3) wrong explanation or no comprehension.

fMRI Data Acquisition

MRI was performed on a 1.5T Philips scanner (Philips MRT Achieva series). Functional data were acquired with echo planar images in 31 transversal slices (repetition time [TR] = 2,800 ms; echo time [TE] = 50 ms; flip angle = 90; slice thickness = 3.5 mm; interslice gap = 0.35 mm; field of view [FoV] = 240 mm, and voxel resolution = 3.75 mm × 3.75 mm). Slices were positioned to achieve whole brain coverage. 360 volumes were acquired during the functional run. After the functional run, an anatomical scan was acquired for each participant using a high‐resolution T1‐weighted 3D‐sequence consisting of 140 transversal slices (TR = 7,670 ms; TE = 3.500 ms; FoV = 256 mm; slice thickness = 1 mm; inter slice gap = 1 mm). The experimental setup including the paradigm, scanner and scanning parameters used in this study was identical to the one applied in our previous study in healthy subjects [Straube et al., 2011a].

Data Analysis

MR images were analyzed using standard routines for first and second level analyses in Statistical Parametric Mapping 8 (SPM 8; http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk) implemented in MATLAB 7 (Mathworks, Sherborn, MA). The first five volumes of each functional run were discarded from the analysis to minimize T1‐saturation effects. To correct for different acquisition times, the signal measured in each slice was shifted relative to the acquisition time of the middle slice using a slice interpolation in time. All images of one session were realigned to the first image of a run to correct for head movement and normalized into standard stereotactic anatomical MNI‐space by using the transformation matrix calculated from the first EPI‐scan of each subject and the EPI‐template. Afterwards, the normalized data with a resliced voxel size of 4 mm × 4 mm × 4 mm were smoothed with a 10 mm full‐width at half‐maximum (FWHM) isotropic Gaussian kernel to accommodate for intersubject variation in brain anatomy. A high pass filter (128 s cut of period) was applied to remove low frequency fluctuations in the BOLD signal.

The expected hemodynamic response was modeled 1.5 s after the onset of each block with a duration of 22 s by a canonical hemodynamic response function [Friston et al., 1998]. The function was convolved with the block sequence in a general linear model, which also included the six movement nuisance regressors to account for movement during the scan interval.

A group analysis was performed by entering contrast images into a flexible factorial analysis as implemented in SPM8, in which subjects are treated as random variables. For comparison of patients data with the data of the healthy subject's group (see contrasts of interest) contrast images of both groups were entered into a flexible factorial analysis. To account for the significant differences in RTs between patients and controls in the control task, we included RTs as covariate of no‐interest in the statistical model.

To correct the fMRI results for multiple comparisons we employed a Monte‐Carlo simulation of the brain volume to establish an appropriate voxel contiguity threshold [Slotnick et al., 2003; Straube et al., 2011a]. This correction is more sensitive to smaller effect sizes while still correcting for multiple comparisons across the whole brain volume. The procedure is based on the fact that the probability of observing clusters of activity due to voxel‐wise Type I error (i.e., noise) decreases systematically as cluster size increases. Therefore, the cluster extent threshold can be determined to ensure an acceptable level of corrected cluster‐wise Type I error. We ran a Monte‐Carlo simulation to model the brain volume (http://www2.bc.edu/_slotnics/scripts.htm; with 1,000 iterations) using the same parameters as in our study (i.e., acquisition matrix, number of slices, voxel size, resampled voxel size, and FWHM). Assuming an individual voxel type I error of P < 0.05, a cluster extent of 17 contiguous resampled voxels was indicated as necessary to correct for multiple voxel comparisons at P < 0.05. We applied this cluster threshold to all reported analyses (this is exactly the same procedure as previously applied to the identical paradigm in healthy subjects, see Straube et al., 2011a).

The reported voxel coordinates of activation peaks are located in MNI space. The functional data were referenced to probabilistic cytoarchitectonic maps for the anatomical localisation [Eickhoff et al., 2005].

Statistical analyses of data other than fMRI were performed using SPSS version 15.0 for Windows (SPSS, Chicago, IL). Statistical analyses are two‐tailed with α‐levels of significance of P < 0.05.

Contrasts of Interest

Parallel to our previous analyses in healthy subjects [Straube et al., 2011a], we computed particular contrasts of interest to test our hypotheses. We analyzed activation patterns of all four conditions against baseline to obtain an overview of the general brain regions involved in isolated and combined speech and gesture processing (Baseline Contrasts: IC, S, G, and MP). To test our hypothesis that there would be differences in the processing of IC versus MP co‐verbal gestures we calculated difference contrasts between both conditions (IC vs. MP and vice versa).

In the context of this study we define integration as the increased neural activity due to bimodal (as opposed to unimodal) processing of speech and gesture. To identify bimodal integration activity we calculated the conjunction (testing a logical AND, Nichols et al., 2005) of bimodal in contrast to both unimodal conditions ([IC > S ∩ IC > G] and [MP > S ∩ MP > G]). To confirm that the revealed regions do in fact receive input from both unimodal conditions (see Calvert, 2001) we further restricted this analysis to regions activated during both unimodal conditions when compared with baseline. Therefore we calculated the following contrast for the IC co‐verbal gesture condition: [(IC > S ∩ IC > G) inclusively masked by S ∩ G], and the following conjunction for MP co‐verbal gesture condition: [(MP > S ∩ MP > G) inclusively masked by S ∩ G].

Finally, we were interested in the direct comparison of the patient data with our previous healthy subject data [Straube et al., 2011a]. Therefore, we reanalyzed the data of the healthy subject group in accordance to patient group (using SPM8 for first and second level procedure) and performed the following contrasts in a single whole brain group analysis:

First, we investigated the overlap between the previous defined conjunction analyses in patients (P) and controls (C) for the IC ([(P‐IC > P‐S ∩ P‐IC > P‐G) inclusively masked by P‐S ∩ P‐G] ∩ [(C‐IC > C‐S ∩ C‐IC > C‐G) inclusively masked by C‐S ∩ C‐G]) and MP gesture condition ([(P‐MP > P‐S ∩ P‐MP > P‐G) inclusively masked by P‐S ∩ P‐G] ∩ [(C‐MP > C‐S ∩ C‐MP > C‐G) inclusively masked by C‐S ∩ C‐G]).

Second, we calculated the interaction between group (P, C) and co‐verbal gesture condition (IC and MP) to support our assumption of a selective dysfunction for the processing of MP co‐verbal gestures.

Finally, we explored additional processes stronger activated for the processing of co‐verbal gesture conditions in the patient group compared with the healthy control group (P‐IC > C‐IC; P‐MP > C‐MP).

RESULTS

Behavioral Results

Behavioral data revealed continuous responses over the whole session with no differences in numbers of responses (IC m = 89.27%, SD = 21.61%; G m = 87.80%, SD = 22.06%; S m = 90.07%, SD = 20.22%; MP m = 89.87%, SD = 18.92%; F(3, 42) = 1.045, P = 0.368, within‐subject ANOVA) and reaction times across conditions (IC m = 1,034 ms, SD = 1,050 ms; G m = 912 ms, SD = 816 ms; S m = 938 ms, SD = 989 ms; MP m = 965 ms, SD = 829 ms; F(3, 42) = 1.110, P = 0.339, within‐subject ANOVA). The reaction times of the patient sample were significant slower compared with the healthy control group as indicated by an significant main effect group (patient: m = 527 ms, SE = 36 ms; controls: m = 962 ms, SE = 43 ms; F(1,24) = 88.061, P = 0.001). However, there is no significant interaction between group and condition (F(3,22) = 0.502, P = 0.658) indicating a general slower response behavior independent of gesture condition.

Data of the retelling task revealed high comprehension performances, with complete and correct understanding of above 90% for utterances of the IC (m = 98.33%, SD = 4.71%) and MP condition (m = 95.42%, SD = 3.05%).

In the subsequent memory task (see Straube et al., 2011a for detail) patients did not show any memory effect as indicated by nonsignificant differences between hits and false alarms for all conditions [IC: t(13) = 0.535, P < 0.535; MP: t(13) = 0.576, P = 0.574; S: t(13) = 0.635, P = 0.536]. However, direct comparisons between the patient and the control group did not lead to any significant main [F(1,25) = 2.480, P < 0.128] or interaction effects with regard to the group factor [group × condition: F(2,25) = 0.877, P = 0.422; group × hits‐false alarms: F(1,25) = 4.030, P = 0.058; group × condition × hits‐false alarms: F(2,50) = 0.917, P = 0.406] in an analyses of variance (ANOVA), possibly due to the small sample sizes and the high variation in memory performance.

fMRI Results

We firstly calculated the following analyses for the patient group: (A) we present the results of the direct contrasts of each condition against baseline (fixation cross), then, we directly compare the processing of IC and MP gestures. Finally, the conjunction analyses designed to reveal activations related to natural semantic integration processes are presented for IC and MP speech–gesture processing.

In a second step, whole brain group comparisons were performed. First, we investigated the overlap between the previous defined conjunction analyses in patients (P) and controls (C) for the IC and MP gesture condition. Second, we calculated the interaction between group (P and C) and co‐verbal gesture condition (IC and MP) to support our assumption of a selective dysfunction for the processing of MP co‐verbal gestures. Finally, we explored additional processes in the patient group compared with the healthy control group indicated by stronger activation for the processing of co‐verbal gesture conditions (P‐IC > C‐IC; P‐MP > C‐MP). All differential contrasts were inclusively masked by the minuend condition to avoid results based on deactivation (<baseline).

Conditions in Comparison to Low‐Level Baseline (Fixation Cross)

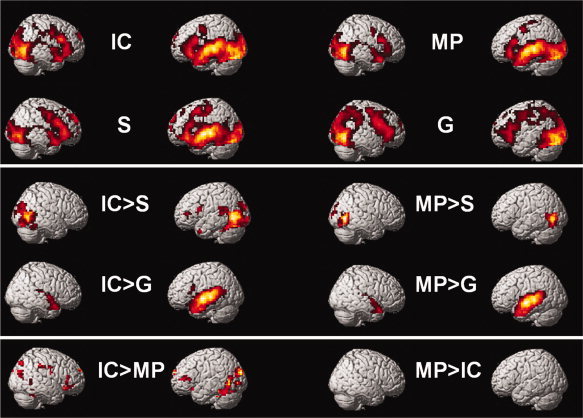

In patients with schizophrenia, we found for all auditory conditions (IC, S, and MP) versus baseline (fixation cross) we found an extended network of bi‐hemispheric medial and lateral temporal and left inferior frontal activity. The data set of one patient had a small extinction of signal in the right inferior temporal lobe, which led to an extinction of activation on the group level, too. As exclusion of this patient did not change the general result pattern, we did not exclude this patient from the sample in the final analysis. In the gesture conditions (IC, G, and MP), activation clusters extended into the occipital lobes and the cerebellum (see Fig. 2). Gesture conditions without speech showed less activation in the temporal lobes than did conditions with auditory input (see Fig. 2).1

Figure 2.

Activation patterns for each condition in contrast to baseline (fixation cross +) and in comparison to each other in patients with schizophrenia. Activation patterns for each of the four conditions in contrast to baseline (fixation cross), the bimodal conditions in contrast to the unimodal conditions (IC > S; IC > G; MP > S; MP > G) and the direct contrasts of the processing of iconic (IC) and metaphoric (MP) co‐verbal gestures (IC > MP; MP > IC; see Table I). IC: iconic co‐verbal gesture condition (concrete); MP: metaphoric co‐verbal gestures condition (abstract); S: speech without gesture; G: gesture without speech. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

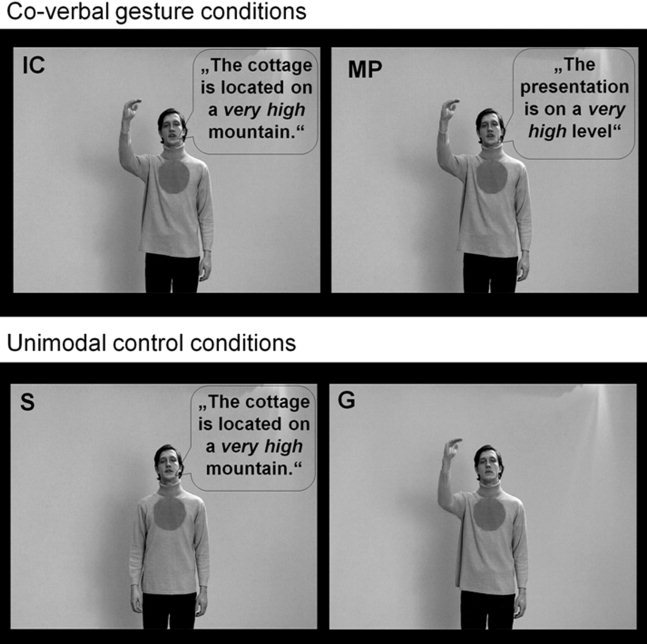

Figure 1.

Examples of the four experimental conditions [Straube et al. 2011a]. The stimulus material consisted of videos of an actor performing iconic (IC) and metaphoric (MP) co‐verbal gestures as well as two unimodal control conditions (spoken sentences without gestures [S] and gestures without sentences [G]). A screenshot of a typical video is shown for each condition. For illustrative purposes the spoken German sentences were translated into English and written in speech bubbles.

IC versus MP Co‐Verbal Gestures

The direct comparison of IC versus MP speech–gesture pairs [IC > MP] in patients with schizophrenia resulted in large activation clusters in distributed temporal–occipital and prefrontal regions bilaterally (see Table I and Fig. 2). In contrast, the reverse comparison [MP > IC] resulted in no significant activation (see Table I and Fig. 2).

Table I.

Iconic vs. metaphoric co‐verbal gesture processing in patients with schizophrenia

| Coordinates | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anatomical region | Cluster extent | x | y | z | t‐Value | P‐Value | No. of voxels |

| Patients: IC > MP | |||||||

| Left lingual gyrus | Fusiform gyrus, IOG, calcarine gyrus, cerebellum, precuneus, post. cingulum, hippocampus | −28 | −68 | −4 | 4.33 | 0.000 | 1131 |

| Right insula | Rol.OP, postcentral gyrus, supramarginal gyrus, inferior parietal lobe, putamen | 36 | −24 | 28 | 4.06 | 0.000 | 70 |

| Left SFG | Middle frontal gyrus | −20 | 64 | 24 | 3.87 | 0.000 | 28 |

| Right OFC | 32 | 36 | −8 | 3.20 | 0.001 | 36 | |

| Left IFG | Middle frontal gyrus, insula | −40 | 40 | 8 | 2.97 | 0.002 | 26 |

| Left OFC | Insula | −28 | 20 | −16 | 2.64 | 0.005 | 17 |

| Left ACC | Nucleus caudatus | −12 | 32 | 4 | 2.64 | 0.005 | 17 |

| Right MOG | Superior occipital gyrus, MTG, cuneus | 36 | −76 | 28 | 2.63 | 0.005 | 37 |

| Right SPL | Superior occipital gyrus, cuneus | 28 | −76 | 48 | 2.60 | 0.005 | 18 |

| Right IFG | Inferior and middle OFC, insula | 48 | 32 | 4 | 2.48 | 0.007 | 17 |

| Right postcentral gyrus | Supramarginal gyrus, Rol.OP, precentral gyrus, insula | 56 | −8 | 24 | 2.44 | 0.008 | 21 |

| Patients: IC > MP | |||||||

| n.s. | |||||||

Coordinates (MNI), cluster extent and t‐values of the difference contrasts of iconic versus metaphoric gestures. Cluster level corrected at P < 0.05. MTG, middle temporal gyrus; IFG, inferior frontal gyrus; STG, superior temporal gyrus; IOG, inferior occipital gyrus; MOG, middle occipital gyrus; SFG, superior frontal gyrus; OFC, orbitofrontal cortex; SPL, superior parietal lobe; MFG, medial frontal gyrus; ITG, inferior temporal gyrus; Rol.OP, rolandic operculum; OL, occipital lobe; HC, hippocampus; SMA, supplemental motor area.

Multimodal Integration of IC and MP Co‐Verbal Gestures in Schizophrenia

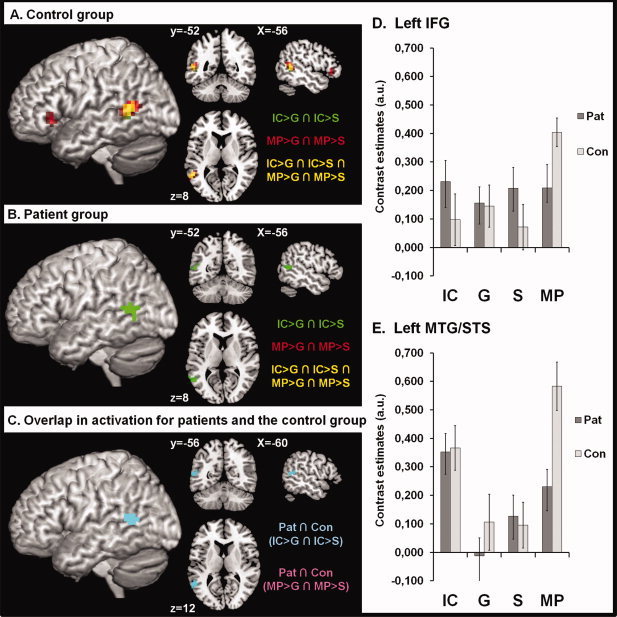

For bimodal integration processes in the IC co‐verbal gesture condition (conjunction analysis [(IC > S ∩ IC > G) inclusively masked by S ∩ G]) we observed activation of the left posterior middle temporal gyrus (pMTG; MTG/STG: MNIx,y,z = [−60, −60, 8], t = 2.16, number of voxels = 19; P < 0.05 corrected; see Fig. 3 green). The corresponding analyses for MP co‐verbal gestures [(MP > S ∩ MP > G) inclusively masked by S ∩ G] revealed no sig. activation (see Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Group comparison of integration processes. (A) shows brain regions with increased activation for bimodal (IC: green; MP: red; IC ∩ MP: yellow) in contrast to unimodal processing of speech and gesture, as identified through conjunction analyses in the healthy control group. Green = iconic: [(IC > S ∩ IC > G) inclusively masked for S ∩ G], red = metaphoric: [(MP > S ∩ MP > G) inclusively masked for S ∩ G]. Yellow = overlap: [(IC > S ∩ IC > G) ∩ (MP > S ∩ MP > G) inclusively masked for S ∩ G]. (A) shows results from healthy subjects previously published [Straube et al. 2011a], now analyzed using SPM8. (B) shows brain regions with increased activation for bimodal (IC: green; MP: red; IC ∩ MP: yellow) in contrast to unimodal processing of speech and gesture, as identified through conjunction analyses in patients with schizophrenia. The contrasts and color coding are identical to (A). For patients with schizophrenia only the posterior temporal lobe is significantly activated for iconic co‐verbal gestures in contrast to the unimodal control conditions. (C) Overlap in conjunctional activation in patients (IC > S ∩ IC > G) and healthy subjects (IC > S ∩ IC > G) illustrated in light blue (for statistics see result section). For the MP condition no overlap was found. Bar graphs (D and E) illustrate contrast estimates for the left IFG and posterior MTG based on the extracted eigenvariate of the respective activation clusters. Error bars represent the standard errors of the mean. IC: iconic co‐verbal gesture condition (concrete); MP: metaphoric co‐verbal gestures condition (abstract); S: speech without gesture; G: gesture without speech; Pat: patient group; Con: control group. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

Group Comparison of Integration Processes

To compare integration processes of patients with schizophrenia with those of the healthy control we calculated the overlap (conjunction) between the previous defined conjunction analyses in patients (P) and controls (C) for the IC ([(P‐IC > P‐S ∩ P‐IC > P‐G) inclusively masked by P‐S ∩ P‐G] ∩ [(C‐IC > C‐S ∩ C‐IC > C‐G) inclusively masked by C‐S ∩ C‐G]) and MP gesture condition ([(P‐MP > P‐S ∩ P‐MP > P‐G) inclusively masked by P‐S ∩ P‐G] ∩ [(C‐MP > C‐S ∩ C‐MP > C‐G) inclusively masked by C‐S ∩ C‐G]).

For the integration contrast of the IC conditions we found a small overlap of conjunctional activation for patients and control subjects in the left MTG/STS (MNIx,y,z = [−60, −56, 12], t = 1.96, number of voxels = 12; P < 0.05; see Fig. 3C light blue). The overlap is a result of an slightly more anterior located activation in the healthy subject group (MNIx,y,z = [−56, −52, 8], t = 3.20, number of voxels = 29; P < 0.05 corrected; see Fig. 3A green/yellow) and a more posterior located activation in the patient group (see above and Fig. 3B).

For the integration contrast of the MP conditions we obtained no significant effect due to absent activation in the patient group in the conjunction analyses (see above). By contrast healthy subjects activated the left IFG (MNIx,y,z = [−52, 28, 0], t = 2.94, number of voxels = 17; P < 0.05 corrected; see Fig. 3A red) and the posterior MTG/STS (MNIx,y,z = [−56, −52, 12], t = 4.09, number of voxels = 46; P < 0.05 corrected; see Fig. 3A red). The bar graphs in Figure 3 indicate comparable activations in the posterior MTG/STS with regard to the IC, G, and S condition in patients and the healthy control group, but differences with regard to the MP condition.

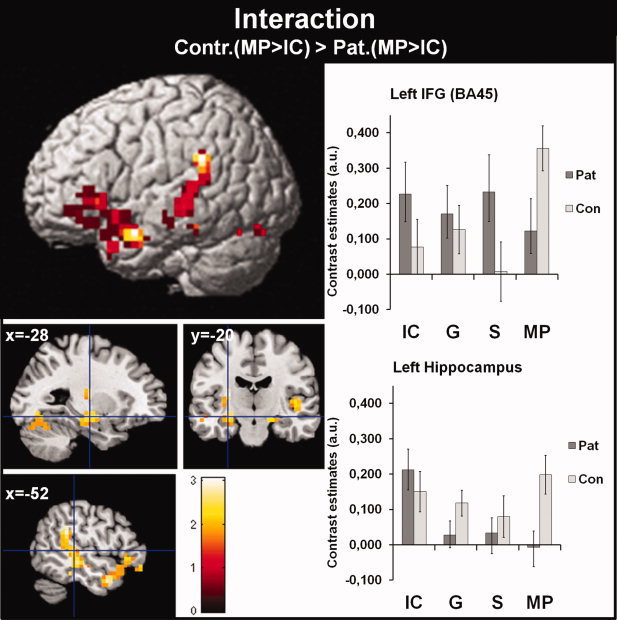

Interaction of Group (P and C) and Gesture Condition (IC and MP)

To test for a specific aberrant processing of MP co‐verbal gestures in patients with schizophrenia, we calculated the interaction between group (P and C) and gesture condition (IC and MP). For the interaction (C‐MP > C‐IC) > (P‐MP > P‐IC) we obtained activation distributed across left hemispheric and bilateral brain regions, including the left IFG, anterior and posterior activations of the MTG/STS/STG and the bilateral hippocampus (see Fig. 4 and Table II). The contrast estimates for the left IFG and left hippocampus (see Fig. 4), which are representative for the whole activation pattern, indicate that the significant interaction is predominantly driven by a reduced activation for the MP condition in patients. The interaction is relatively stable and a highly comparable activation pattern remains even after exclusion of female patients and including age as co‐variate of no interest.

Figure 4.

Interaction of group (P, C) and gesture condition (IC, MP). This figure illustrates the significant interaction of group (P, C) and gesture condition (C‐MP > C‐IC) > (P‐MP > P‐IC). Bar graphs on the right represent the contrast estimates for activation of the left IFG (BA45) and hippocampus, which are representative for the whole activation pattern. Bar graphs are based on the extracted eigenvariate from predefined ROIs of the BA45 and the left Hippocampus (including all subregions). ROIs are created by the use of the Anatomy Toolbox (Eickhoff et al. 2005). Error bars represent the standard error of the mean. The opposite contrast revealed no significant activation (C‐MP > C‐IC) < (P‐MP > P‐IC). IC: iconic co‐verbal gesture condition (concrete); MP: metaphoric co‐verbal gestures condition (abstract); S: speech without gesture; G: gesture without speech; Pat: patient group; Con: control group. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

Table II.

Interaction of group and gesture condition (C‐MP > C‐IC) > (P‐MP > P‐IC)

| Coordinates | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anatomical region | Cluster extent | x | y | z | t‐Value | P‐value | No. of voxels |

| Right lingual gyrus | Thalamus, hippocampus, parahippocampus, amygdala | 8 | −32 | 0 | 3.06 | 0.001 | 69 |

| Left insula | Putamen, hippocampus, heschls gyrus, pallidum | −28 | −20 | 16 | 2.97 | 0.002 | 82 |

| Left supramarginal gyrus | STG, MTG, STS, ITG, Rol.OP | −52 | −44 | 28 | 2.89 | 0.002 | 110 |

| Left MTG | IFG (BA45), ITG, temporal pole, STG, STS, | −52 | 0 | −24 | 2.82 | 0.003 | 116 |

| Right STG | Heschls gyrus, insula, Rol.OP | 44 | −24 | 4 | 2.58 | 0.006 | 47 |

| Left fusiform gyrus | Lingual gyrus, MOG, cerebellum | −24 | −76 | −4 | 2.56 | 0.006 | 24 |

| Right fusiform gyrus | ITG, cerebellum, IOG | 40 | −48 | −16 | 2.28 | 0.012 | 22 |

Coordinates (MNI), cluster extent and t‐values of the difference contrasts of iconic versus metaphoric gestures. Cluster level corrected at P < 0.05. MTG, middle temporal gyrus; IFG, inferior frontal gyrus; STG, superior temporal gyrus; IOG, inferior occipital gyrus; MOG, middle occipital gyrus; SFG, superior frontal gyrus; OFC, orbitofrontal cortex; SPL, superior parietal lobe; MFG, medial frontal gyrus; ITG, inferior temporal gyrus; Rol.OP, rolandic operculum; OL, occipital lobe; HC, hippocampus; SMA, supplemental motor area.

The interaction in the opposite direction (C‐MP > C‐IC) < (P‐MP > P‐IC) revealed no significant activation.

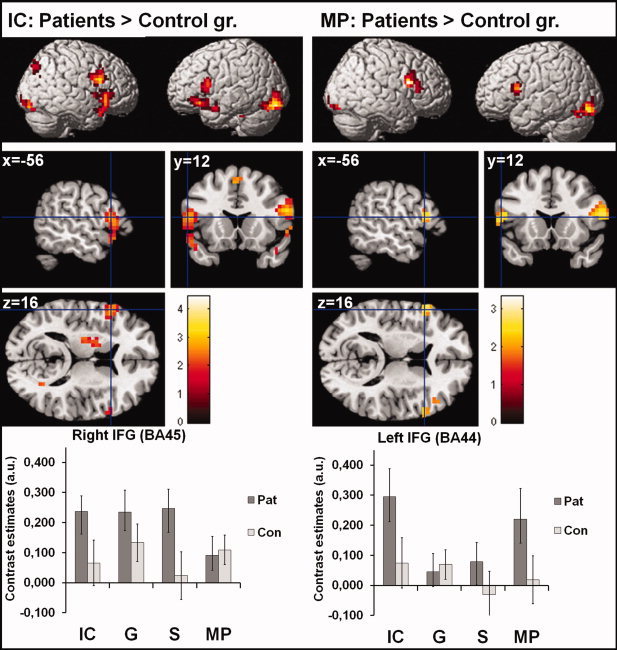

Additional Processes for the Processing of IC and MP in Patients with Schizophrenia

Finally, we explored additional processes in the patient group compared with the healthy control group indicated by stronger activation for the processing of co‐verbal gestures (P‐IC > C‐IC; P‐MP > C‐MP). For both gesture–speech conditions we found more activation in bilateral frontal and occipital structures (with extensions to the cerebellum) for patient compared with control subjects. For the IC condition additional activation in the left putamen and the SMA were found (see Fig. 5 and Table III). The activation of the left IFG in both contrasts is more superior and posterior than the IFG activation of the interaction analyses (see above). Group differences are stable and remain even after exclusion of female patients and including age as covariate of no interest.

Figure 5.

Processing of IC and MP in patients in contrast to controls. This figure illustrate the additional processes, indicated by stronger activation for the processing of co‐verbal gestures, in the patient group compared with the healthy control group (P‐IC > C‐IC; P‐MP > C‐MP). For both gesture–speech conditions we found more activation in bilateral frontal and occipital structures (see Table III). The activation of the left IFG in both contrasts is more superior and posterior that the IFG activation of the interaction analyses (see Fig 4). Bar graphs at the right represent the contrast estimates for activation of the left IFG (BA44) and right IFG (BA45), which are representative for the whole activation pattern. Bar graphs are based on the extracted eigenvariate from predefined ROIs of the right BA45 and the left BA44. ROIs were created by means of the Anatomy Toolbox (Eickhoff et al. 2005). Error bars represent the standard errors of the mean. The opposite contrasts revealed no significant activation [(C‐MP > P‐MP) and (C‐IC > P‐IC)]. IC: iconic co‐verbal gesture condition (concrete); MP: metaphoric co‐verbal gestures condition (abstract); S: speech without gesture; G: gesture without speech; Pat: patient group; Con: control group. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

Table III.

Increased activation for patients in contrast to controls

| Coordinates | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anatomical region | Cluster extent | x | y | z | t‐Value | P‐value | No. of voxels |

| IC: Patients > controls | |||||||

| Left lingual gyrus | Fusiform gyrus, cerebellum, IOG, MOG | −36 | −88 | −20 | 4.46 | 0.000 | 166 |

| Right cerebellum | Lingual gyrus, IOG, calcarine gyrus | 12 | −88 | −20 | 3.29 | 0.001 | 77 |

| Left temporal pole | IFG, MTG, STS, STG, precentral gyrus | −44 | 0 | −20 | 3.21 | 0.001 | 159 |

| Right IFG | Middle frontal gyrus | 56 | 12 | 24 | 3.19 | 0.001 | 95 |

| Left SMA | Medial and superior frontal gyrus | −8 | 8 | 56 | 3.05 | 0.001 | 22 |

| Left cerebellum | −24 | −40 | −32 | 2.70 | 0.004 | 18 | |

| Right inferior frontal operculum | IFG, middle frontal gyrus, Rol.OP, insula | 56 | 16 | 0 | 2.64 | 0.005 | 125 |

| Left pallidum | Putamen, thalamus, caudatus, insula | −16 | 0 | 4 | 2.48 | 0.007 | 133 |

| Right superior occipital gyrus | MOG, cuneus, precuneus, SPL | 28 | −68 | 20 | 2.44 | 0.008 | 57 |

| Right hippocampus | Thalamus, putamen, parahippocampus | 20 | −20 | −8 | 2.00 | 0.024 | 17 |

| MP: Patients > controls | |||||||

| Left IOG | Cerebellum, fusiform gyrus, lingual gyrus, MOG | −48 | −72 | −20 | 3.34 | 0.001 | 76 |

| Left IFG | Precentral gyrus | −56 | 12 | 16 | 2.81 | 0.003 | 24 |

| Right IFG | Precentral gyrus, middle frontal gyrus, insula | 56 | 12 | 20 | 2.73 | 0.004 | 65 |

| Right IOG | Lingual gyrus, fusiform gyrus, calcarine gyrus | 36 | −88 | −12 | 2.10 | 0.019 | 17 |

Coordinates (MNI), cluster extent and t‐values of the difference contrasts of iconic versus metaphoric gestures. Cluster level corrected at P < 0.05. MTG, middle temporal gyrus; IFG, inferior frontal gyrus; STG, superior temporal gyrus; IOG, inferior occipital gyrus; MOG, middle occipital gyrus; SFG, superior frontal gyrus; OFC, orbitofrontal cortex; SPL, superior parietal lobe; MFG, medial frontal gyrus; ITG, inferior temporal gyrus; Rol.OP, rolandic operculum; OL, occipital lobe; HC, hippocampus; SMA, supplemental motor area.

DISCUSSION

Interpersonal communication and especially speech gesture interaction has received increased interest from the field of neuroscience. But so far most of the studies were limited to healthy subjects. The few behavioral studies including patients with schizophrenia have suggested that these patients have deficits in the comprehension of communicative gestures [Berndl et al., 1986; Bucci et al., 2008; Grüsser et al., 1990; Matthews et al., 2011]. Further, patients exhibit problems with the understanding of abstract sentences, clinically termed “concretism” [Bergemann et al., 2008; Iakimova et al., 2010; Kircher et al., 2007].

In our study, we directly compared the processing of two important co‐verbal gesture types in patients with schizophrenia to reveal the roles of specific brain regions in dysfunctional integration of speech and gesture. Our data suggest intact integration processes for IC co‐verbal gestures in patients with schizophrenia as reflected in activation of the left pMTG, similar to healthy subjects [Green et al., 2009; Holle et al., 2008,2010; Straube et al., 2011a]. By contrast, the neural integration of gesture meaning into an abstract sentence context (MP gestures), which in healthy subjects activated the left pMTG/STS and IFG [Kircher et al., 2009; Straube et al., 2009,2011a], is disturbed in patients with schizophrenia. This is evident in the results of absent activation for MP co‐verbal gestures in contrast to unimodal control conditions.

The aberrant processing of MP in contrast to IC co‐verbal gestures in patients with schizophrenia is further supported by the interaction of activation of the factors group and gesture condition, in the bilateral hippocampus, the left MTG, STS, and STG as well as the inferior part of the BA45 of the left IFG. These data suggest processing differences between patients with schizophrenia and healthy controls with regard to the abstractness of multimodal communication. Additional bilateral frontal and occipital activations in patients in contrast to controls might reflect increased integration effort [Green et al., 2009; Willems et al., 2007] for gestures in an abstract sentence context (see below).

The general activation of each condition in contrast to low level baseline resembled the typical activation patterns in response to our speech–gesture stimuli, including visual, auditory and language related networks [Green et al., 2009; Kircher et al., 2009; Straube et al., 2010,2011a,b]. Thus, we did not find a schizophrenia‐associated general dysfunction in brain regions relevant for the processing of speech and gesture (especially the left pMTG/STS and IFG).

In line with our hypotheses and findings from healthy subjects [Straube et al., 2011a] IC co‐verbal gestures in contrast to the isolated control conditions were associated with increased activity in the pMTG/STS (BA 37) in patients with schizophrenia. This region was also active during conditions of speech and gesture alone. Therefore, we consider this area responsible for the integration of speech and gesture information. This interpretation is supported by other research on speech and gesture integration in healthy subjects [Dick et al., 2009; Green et al., 2009; Holle et al., 2008,2010; Kircher et al., 2009; Straube et al., 2011a]. However, for MP gestures in contrast to the two isolated control conditions we did not find any significant activation in patients with schizophrenia. This is interpreted as disturbed integration of MP co‐verbal gestures, because integration processes of MP co‐verbal gestures in healthy subjects previously were identified in the pMTG as well as in the left IFG [Kircher et al., 2009; Straube et al., 2009,2011a]. Our data provide first evidence of a selective dysfunction in the neural integration of MP co‐verbal gestures, whereas integration of IC co‐verbal gestures within the posterior temporal lobe remains intact.

Several studies report the posterior temporal lobe (STS/MTG) as an important multimodal integration site (e.g., Amedi et al., 2005; Calvert, 2001; Hein et al., 2007). However, the IFG has also been proposed to play a role in multimodal integration, especially when the congruency and novelty of picture and sound was modulated [Hein et al., 2007]. Despite previous reports about dysfunctional visual [Silverstein et al., 2009] and multisensory integration in patients with schizophrenia [Surguladze et al., 2001; Szycik et al., 2009], we found that the left pMTG/STS was activated in patients with schizophrenia when IC co‐verbal gestures were compared with unimodal control conditions – as previously demonstrated for healthy control subjects. This finding is remarkable because the connection of speech and gesture is performed on a semantic level, in contrast to for example the phonetic mapping of articulatory mouth movements and single sounds or syllables [Surguladze et al., 2001; Szycik et al., 2009]. For integration of MP gestures it is important to build an abstract relation between concrete visual and abstract verbal information. To build this relation additional online integration or unification processes within the IFG seem to be relevant [Straube et al., 2011a] and are likely to be disturbed in patients with schizophrenia [Kircher et al., 2007].

These results and interpretations are in agreement with a recent claim about the separation of semantic integration and semantic unification processes during semantic comprehension [Hagoort et al., 2009], which suggests that both components are specifically involved in the processing of IC and MP co‐verbal gestures. In a study about integration of IC and pantomime gestures and speech, it has been suggested that integration in pSTS/MTG involves the matching of two input streams for which there is a relatively stable common object representation, whereas integration in LIFG is better characterized as the on‐line construction of a new and unified representation of the input streams [Willems et al., 2009]. Other studies on the processing of IC gestures discussed left and bilateral IFG activations with regard to mirror neuron and related “observation‐execution matching” processes [e.g., Dick et al., 2009; Holle et al., 2008; Skipper et al., 2007]. It has been proposed that when speech perception is accompanied by gesture, this “observation‐execution matching” process plays a role in disambiguating semantic aspects of speech by simulating motor programs involved in gesture production [Dick et al., 2009; Holle et al., 2008; Skipper et al., 2007; Willems and Hagoort, 2007; Willems et al., 2007]. However, because our and previous studies about speech and gesture processing did not include a gesture production condition, we cannot make strong claims about observation‐execution matching in integration processes related to speech and gesture.

Our data from healthy subjects suggest that integration processes (the activation of an already available common memory representation) appear to be all that is necessary for the processing of IC gestures in the context of concrete sentences [Straube et al., 2011a]. In contrast, unification processes (a constructive process in which a semantic representation that is not already available in memory is constructed) are necessary for the processing of MP co‐verbal gestures. The fact that IC and MP co‐verbal gesture processing in healthy subjects do not differ in their posterior temporal activation patterns agrees with the assumption that a dynamic relationship between left IFG and left MTG/STS/STG is necessary for successful semantic unification [Hagoort et al., 2009]. Therefore, our patient data suggest that even in patients with schizophrenia IC co‐verbal gestures seem to activate directly the common memory representation of concrete speech and gesture information (e.g., “round bowl” and the corresponding round gesture). In contrast, constructive processes (unification processes) within the left IFG for the integration of gesture information (e.g., depicting an arch with the right hand) in the context of abstract sentences (e.g., “The politician build a bridge to the next topic”) appear to be absent/dysfunctional in patients with schizophrenia.

One may assume a common impairment within the left IFG underlies difficulties of patients with schizophrenia in the comprehension of metaphors [Kircher et al., 2007] and aberrant integration processes for MP co‐verbal gestures. However, it is important to note that utterances selected for our experiment were easy to understand even for patients with schizophrenia. Accordingly, the patients' comprehension scores indicate a nearly perfect understanding of both concrete (IC) and abstract utterances (MP). Therefore, absent bimodal (opposed to unimodal) activation in response to MP co‐verbal gestures is unlikely to be a result of a general lack of understanding, but rather indicates a dysfunctional unification process for semantics derived from both modalities.

The differential processing of MP in contrast to IC co‐verbal gestures in patients with schizophrenia is further supported by the interaction of activation of the factors group and gesture condition, in the bilateral hippocampus, the left MTG, STS, and STG as well as the inferior part of the BA45 of the left IFG. These data suggest processing differences between patients with schizophrenia and healthy controls with regard to the abstractness of multimodal communication. In addition to the previous discussed fronto‐temporal contribution to speech and gesture integration, we found the hippocampus activated in this contrast. The reduced activation of the hippocampus for gestures in an abstract sentence context (MP) is in line with previous reports about hippocampal dysfunctions in patients with schizophrenia reflected in aberrant activity in working memory [Luck et al., 2010], episodic memory [Leube et al., 2003; Nestor et al., 2007] or free‐associative verbal fluency tasks [Kircher et al., 2008]. In healthy subjects, we could demonstrate that especially the successful binding of gesture information into the abstract sentence context is related to hippocampal activation [Straube et al., 2009]. Thus, reduced activity in the bilateral hippocampus indicates reduced binding of MP gestures and abstract speech information in the patient sample.

In addition, patients demonstrated stronger bilateral frontal and occipital activations in contrast to controls, which might reflect the inability to integrate speech and gesture information on an abstract level. However, in context of the left lateralized network in healthy control subjects (in the conjunction as well as the interaction analyses), this finding of bilateral activation is also in line with previous evidence about a reduced language lateralization in patients with schizophrenia [Crow, 2000; Kircher et al., 2002; Szycik et al., 2009; van Veelen et al., 2011]. Important to note are the regional difference of activations within the IFG found in the specific analyses. Whereas the interaction analyses suggest that the inferior part of the left IFG (BA45) is less activated in patients than in controls, the direct comparisons revealed that a more superior/posterior portion of the left IFG (BA44) is more activated in patients than in controls. These data indicate an aberrant balance in activation of specific sub‐regions of the left IFG (especially BA44 vs. 45) in patients with schizophrenia. Increased activation in BA44 might indicate compensation processes or increased integration effort. In line with this interpretation left [Willems et al., 2007] and bilateral [Green et al., 2009] frontal activation had been found for speech and gesture stimuli which are difficult to integrate (e.g., if speech and gesture were unrelated). Thus, bilateral frontal activation might reflect increased integration effort or increased motor‐stimulation processes [Green et al., 2009] as compensation strategy for patients in contrast to the control group.

However, Dick et al. [ 2009] found in a group of healthy subjects that the left BA45 responded more strongly to gestures during audiovisual discourse relative to auditory‐only discourse, but it was not more activated for meaningless hand movements than for meaningful hand movements. By contrast, the right BA44 and (to a lesser degree) right BA45 demonstrated more activity for meaningless hand movements than for meaningful hand movements. Thus, our finding of reduced left BA45 activity and increased right BA44/45 activity in patients in contrast to controls might suggest that patients interpreted or processed gestures in the MP condition as meaningless or unrelated. Future studies are necessary to understand the functional relevance of this aberrant neural processing of MP co‐verbal gestures in patients with schizophrenia.

A limitation of this study is that the patient sample was not directly matched to the previously investigated sample of healthy male subjects regarding age and gender [Straube et al., 2011a]. However, even more intriguing is that despite these differences between samples, we found a high correspondence of the results for IC co‐verbal gestures within the pMTG/STS for the patient sample and the previously reported healthy subject samples [Dick et al., 2009; Green et al., 2009; Holle et al., 2008,2010; Kircher et al., 2009; Straube et al., 2009,2011a]. Furthermore, this study lacks behavioral evidence for dysfunctional integration of speech and gesture in the patient group. Data of the subsequent memory task, where patients had to decide if an auditory presented sentence was old or new, revealed a general impairment in subsequent memory. This is in line with previous reports of memory dysfunctions in patients with schizophrenia [Allen et al., 2011; Bonner‐Jackson et al., 2008; Soriano et al., 2008; Weiss et al., 2009], but do not support our assumption of dysfunctional integration of speech and gesture. Further studies should implement other behavioral tasks, which are sensitive for behavioral differences in the integration of speech and gesture [e.g., priming tasks, Bernardis et al., 2008; Wu and Coulson, 2007]. A further limitation refers to the control task during the fMRI experiment. Even if the task is independent of our speech–gesture manipulations and we did not instruct participant/patients to respond as fast as possible, we cannot exclude an additional attentional demand on schizophrenic subjects due to the control task (as indicated by longer reaction times). However, with regard to the differences in RTs, we found no interaction between group and conditions, suggesting a general slower response‐behavior in patients. To account for those differences in our fMRI analysis, we included RT as covariate of no‐interest in the analyses.

This study compared for the first time in patients with schizophrenia different kinds of illustrative and elaborative gestures that differed in their relation to speech. Our data indicate intact neural integration processes for IC co‐verbal gestures in patients with schizophrenia and specific aberrant activation for MP co‐verbal gestures. This indicates intact perceptual‐matching processes within the pMTG/STS and dysfunctional higher order relational processes in the left IFG. Especially the finding of intact integration of IC gestures in patients with schizophrenia can be relevant for future treatment, e.g., if gestures in concrete sentence context will be used to compensate for, or for training of, language and social dis/abilities in patients with schizophrenia. Thus, future research may focus on the functional relevance of co‐verbal gestures for comprehension, communication and social interaction in patients with schizophrenia.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all the subjects and patients who participated in this study and Georg Eder, André Schüppen and the IZKF service team for support acquiring the data. The data were collected in Aachen (K.S., A.K., A.G., and B.S.), the data analyses and the writing of the manuscript were performed in Marburg (T.K., B.S.).

REFERENCES

- Allen P, Seal ML, Valli I, Fusar‐Poli P, Perlini C, Day F, Wood SJ, Williams SC, McGuire PK ( 2011): Altered prefrontal and hippocampal function during verbal encoding and recognition in people with prodromal symptoms of psychosis. Schizophr Bull 37: 746–756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amedi A, von Kriegstein K, van Atteveldt NM, Beauchamp MS, Naumer MJ ( 2005): Functional imaging of human crossmodal identification and object recognition. Exp Brain Res 166: 559–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen NC ( 1983): Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS). Iowa City, IA: University of Iowa. [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen NC ( 1984). Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS). Iowa City, IA: University of Iowa. [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen NC, Pressler M, Nopoulos P, Miller D, Ho BC ( 2010). Antipsychotic dose equivalents and dose‐years: A standardized method for comparing exposure to different drugs. Biol Psychiatry 67: 255–262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauchamp MS, Argall BD, Bodurka J, Duyn JH, Martin A ( 2004): Unraveling multisensory integration: Patchy organization within human STS multisensory cortex. Nat Neurosci 7: 1190–1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauchamp MS, Yasar NE, Frye RE, Ro T ( 2008): Touch, sound and vision in human superior temporal sulcus. Neuroimage 41: 1011–1020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergemann N, Parzer P, Jaggy S, Auler B, Mundt C, Maier‐Braunleder S ( 2008): Estrogen and comprehension of metaphoric speech in women suffering from schizophrenia: Results of a double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial. Schizophr Bull 34: 1172–1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernardis P, Salillas E, Caramelli N ( 2008): Behavioural and neurophysiological evidence of semantic interaction between iconic gestures and words. Cogn Neuropsychol 25: 1114–1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berndl K, von Cranach M, Grüsser OJ ( 1986): Impairment of perception and recognition of faces, mimic expression and gestures in schizophrenic patients. Eur Arch Psychiatry Neurol Sci 235: 282–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonner‐Jackson A, Yodkovik N, Csernansky JG, Barch DM ( 2008. Episodic memory in schizophrenia: The influence of strategy use on behavior and brain activation. Psychiatry Res 164: 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucci S, Startup M, Wynn P, Baker A, Lewin TJ ( 2008): Referential delusions of communication and interpretations of gestures. Psychiatry Res 158: 27–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunge SA, Helskog EH, Wendelken C ( 2009): Left, but not right, rostrolateral prefrontal cortex meets a stringent test of the relational integration hypothesis. Neuroimage 46: 338–342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunge SA, Wendelken C, Badre D, Wagner AD ( 2005): Analogical reasoning and prefrontal cortex: Evidence for separable retrieval and integration mechanisms. Cereb Cortex 15: 239–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvert GA ( 2001): Crossmodal processing in the human brain: Insights from functional neuroimaging studies. Cereb Cortex 11: 1110–1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crow TJ ( 2000): Schizophrenia as the price that homo sapiens pays for language: A resolution of the central paradox in the origin of the species. Brain Res Brain Res Rev 31: 118–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Bonis M, Epelbaum C, Deffez V, Féline A ( 1997): The comprehension of metaphors in schizophrenia. Psychopathology 30: 149–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dick AS, Goldin‐Meadow S, Hasson U, Skipper JI, Small SL ( 2009): Co‐speech gestures influence neural activity in brain regions associated with processing semantic information. Hum Brain Mapp 30: 3509–3526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eickhoff SB, Stephan KE, Mohlberg H, Grefkes C, Fink GR, Amunts K, Zilles K ( 2005): A new SPM toolbox for combining probabilistic cytoarchitectonic maps and functional imaging data. Neuroimage 25: 1325–1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eviatar Z, Just MA ( 2006): Brain correlates of discourse processing: An fMRI investigation of irony and conventional metaphor comprehension. Neuropsychologia 44: 2348–2359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green A, Straube B, Weis S, Jansen A, Willmes K, Konrad K, Kircher T ( 2009): Neural integration of iconic and unrelated coverbal gestures: A functional MRI study. Hum Brain Mapp 30: 3309–3324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green AE, Fugelsang JA, Dunbar KN ( 2006a): Automatic activation of categorical and abstract analogical relations in analogical reasoning. Mem Cognit 34: 1414–1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green AE, Fugelsang JA, Kraemer DJ, Shamosh NA, Dunbar KN ( 2006b): Frontopolar cortex mediates abstract integration in analogy. Brain Res 1096: 125–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grüsser OJ, Kirchhoff N, Naumann A ( 1990): Brain mechanisms for recognition of faces, facial expression, and gestures: Neuropsychological and electroencephalographic studies in normals, brain‐lesioned patients, and schizophrenics. Res Publ Assoc Res Nerv Ment Dis 67: 165–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagoort P, Baggio G, Willems R ( 2009): Semantic unification In: Gazzaniga M, editor. The Cognitive Neurosciences IV. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hein G, Doehrmann O, Müller NG, Kaiser J, Muckli L, Naumer MJ ( 2007): Object familiarity and semantic congruency modulate responses in cortical audiovisual integration areas. J Neurosci 27: 7881–7887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holle H, Gunter TC, Ruschemeyer SA, Hennenlotter A, Iacoboni M ( 2008): Neural correlates of the processing of co‐speech gestures. Neuroimage 39: 2010–2024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holle H, Obleser J, Rueschemeyer SA, Gunter TC ( 2010): Integration of iconic gestures and speech in left superior temporal areas boosts speech comprehension under adverse listening conditions. Neuroimage 49: 875–884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard AL, Wilson SM, Callan DE, Dapretto M ( 2009): Giving speech a hand: Gesture modulates activity in auditory cortex during speech perception. Hum Brain Mapp 30: 1028–1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iakimova G, Passerieux C, Denhière G, Laurent JP, Vistoli D, Vilain J, Hardy‐Baylé MC ( 2010): The influence of idiomatic salience during the comprehension of ambiguous idioms by patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res 177: 46–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kable JW, Chatterjee A ( 2006): Specificity of action representations in the lateral occipitotemporal cortex. J Cogn Neurosci 18: 1498–1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kable JW, Kan IP, Wilson A, Thompson‐Schill SL, Chatterjee A ( 2005): Conceptual representations of action in the lateral temporal cortex. J Cogn Neurosci 17: 1855–1870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA ( 1987): The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 13: 261–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly SD, Ozyürek A, Maris E ( 2010): Two sides of the same coin: Speech and gesture mutually interact to enhance comprehension. Psychol Sci 21: 260–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kircher T, Straube B, Leube D, Weis S, Sachs O, Willmes K, Konrad K, Green A ( 2009): Neural interaction of speech and gesture: Differential activations of metaphoric co‐verbal gestures. Neuropsychologia 47: 169–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kircher T, Whitney C, Krings T, Huber W, Weis S ( 2008): Hippocampal dysfunction during free word association in male patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 101: 242–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kircher TT, Leube DT, Erb M, Grodd W, Rapp AM ( 2007): Neural correlates of metaphor processing in schizophrenia. Neuroimage 34: 281–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kircher TT, Liddle PF, Brammer MJ, Williams SC, Murray RM, McGuire PK ( 2002): Reversed lateralization of temporal activation during speech production in thought disordered patients with schizophrenia. Psychol Med 32: 439–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leube DT, Rapp A, Buchkremer G, Bartels M, Kircher TT, Erb M, Grodd W ( 2003): Hippocampal dysfunction during episodic memory encoding in patients with schizophrenia—An fMRI study. Schizophr Res 64: 83–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis JW ( 2006): Cortical networks related to human use of tools. Neuroscientist 12: 211–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis JW, Brefczynski JA, Phinney RE, Janik JJ, DeYoe EA ( 2005): Distinct cortical pathways for processing tool versus animal sounds. J Neurosci 25: 5148–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luck D, Danion JM, Marrer C, Pham BT, Gounot D, Foucher J ( 2010): Abnormal medial temporal activity for bound information during working memory maintenance in patients with schizophrenia. Hippocampus 20: 936–948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Q, Perry C, Peng D, Jin Z, Xu D, Ding G, Xu S ( 2003): The neural substrate of analogical reasoning: An fMRI study. Brain Res Cogn Brain Res 17: 527–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin P, Tewesmeier M, Albers M, Schmid G, Scharfetter C ( 1994): Investigation of gestural and pantomime performance in chronic schizophrenic inpatients. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 244: 59–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews N, Gold BJ, Sekuler R, Park S ( 2011): Gesture imitation in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeill D, editor ( 1992): Hand and Mind: What Gestures Reveal About Thought. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mittal VA, Tessner KD, McMillan AL, Delawalla Z, Trotman HD, Walker EF ( 2006): Gesture behavior in unmedicated schizotypal adolescents. J Abnorm Psychol 115: 351–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naumer MJ, Doehrmann O, Müller NG, Muckli L, Kaiser J, Hein G ( 2009): Cortical plasticity of audio‐visual object representations. Cereb Cortex 19: 1641–1653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nestor PG, Kubicki M, Kuroki N, Gurrera RJ, Niznikiewicz M, Shenton ME, McCarley RW ( 2007): Episodic memory and neuroimaging of hippocampus and fornix in chronic schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res 155: 21–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols T, Brett M, Andersson J, Wager T, Poline JB ( 2005): Valid conjunction inference with the minimum statistic. Neuroimage 25: 653–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozyurek A, Willems RM, Kita S, Hagoort P ( 2007): On‐line integration of semantic information from speech and gesture: Insights from event‐related brain potentials. J Cogn Neurosci 19: 605–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapp AM, Leube DT, Erb M, Grodd W, Kircher TT ( 2004): Neural correlates of metaphor processing. Brain Res Cogn Brain Res 20: 395–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapp AM, Leube DT, Erb M, Grodd W, Kircher TT ( 2007): Laterality in metaphor processing: Lack of evidence from functional magnetic resonance imaging for the right hemisphere theory. Brain Lang 100: 142–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein SM, Berten S, Essex B, Kovács I, Susmaras T, Little DM ( 2009): An fMRI examination of visual integration in schizophrenia. J Integr Neurosci 8: 175–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skipper JI, Goldin‐Meadow S, Nusbaum HC, Small SL ( 2007): Speech‐associated gestures, Broca's area, and the human mirror system. Brain Lang 101: 260–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slotnick SD, Moo LR, Segal JB, Hart J Jr ( 2003): Distinct prefrontal cortex activity associated with item memory and source memory for visual shapes. Brain Res Cogn Brain Res 17: 75–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soriano MF, Jiménez JF, Román P, Bajo MT ( 2008): Cognitive substrates in semantic memory of formal thought disorder in schizophrenia. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 30: 70–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson RA, VanDerKlok RM, Pisoni DB, James TW ( 2011): Discrete neural substrates underlie complementary audiovisual speech integration processes. Neuroimage 55: 1339–1345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straube B, Green A, Bromberger B, Kircher T( 2011a): The differentiation of iconic and metaphoric gestures: Common and unique integration processes. Hum Brain Mapp 32: 520–533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straube B, Green A, Chatterjee A, Kircher T ( 2011b): Encoding social interactions: The neural correlates of true and false memories. J Cogn Neurosci 23: 306–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straube B, Green A, Jansen A, Chatterjee A, Kircher T ( 2010): Social cues, mentalizing and the neural processing of speech accompanied by gestures. Neuropsychologia 48: 382–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straube B, Green A, Weis S, Chatterjee A, Kircher T ( 2009): Memory effects of speech and gesture binding: Cortical and hippocampal activation in relation to subsequent memory performance. J Cogn Neurosci 21: 821–836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stringaris AK, Medford NC, Giampietro V, Brammer MJ, David AS ( 2007): Deriving meaning: Distinct neural mechanisms for metaphoric, literal, and non‐meaningful sentences. Brain Lang 100: 150–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surguladze SA, Calvert GA, Brammer MJ, Campbell R, Bullmore ET, Giampietro V, David AS ( 2001): Audio‐visual speech perception in schizophrenia: An fMRI study. Psychiatry Res 106: 1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szycik GR, Münte TF, Dillo W, Mohammadi B, Samii A, Emrich HM, Dietrich DE ( 2009): Audiovisual integration of speech is disturbed in schizophrenia: An fMRI study. Schizophr Res 110: 111–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi H, Kato M, Sassa T, Shibuya T, Koeda M, Yahata N, Matsuura M, Asai K, Suhara T, Okubo Y ( 2010): Functional deficits in the extrastriate body area during observation of sports‐related actions in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 36: 642–647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troisi A, Spalletta G, Pasini A ( 1998): Non‐verbal behaviour deficits in schizophrenia: An ethological study of drug‐free patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand 97: 109–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Veelen NM, Vink M, Ramsey NF, Sommer IE, van Buuren M, Hoogendam JM, Kahn RS ( 2011): Reduced language lateralization in first‐episode medication‐naive schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 127: 195–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss AP, Ellis CB, Roffman JL, Stufflebeam S, Hamalainen MS, Duff M, Goff DC, Schacter DL ( 2009): Aberrant frontoparietal function during recognition memory in schizophrenia: A multimodal neuroimaging investigation. J Neurosci 29: 11347–11359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendelken C, Nakhabenko D, Donohue SE, Carter CS, Bunge SA ( 2008): “Brain is to thought as stomach is to ??”: Investigating the role of rostrolateral prefrontal cortex in relational reasoning. J Cogn Neurosci 20: 682–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willems RM, Hagoort P ( 2007): Neural evidence for the interplay between language, gesture, and action: A review. Brain Lang 101: 278–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willems RM, Ozyurek A, Hagoort P ( 2007): When language meets action: The neural integration of gesture and speech. Cereb Cortex 17: 2322–2333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willems RM, Ozyurek A, Hagoort P ( 2009): Differential roles for left inferior frontal and superior temporal cortex in multimodal integration of action and language. Neuroimage 47: 1992–2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu YC, Coulson S ( 2007): Iconic gestures prime related concepts: An ERP study. Psychon Bull Rev 14: 57–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu YC, Coulson S ( 2010): Gestures modulate speech processing early in utterances. Neuroreport 21: 522–526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Gannon PJ, Emmorey K, Smith JF, Braun AR ( 2009): Symbolic gestures and spoken language are processed by a common neural system. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 20664–20669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]