Abstract

Patients with Parkinson's disease (PD) can develop mild cognitive impairment (PD‐MCI), frequently progressing to dementia (PDD). Here, we aimed to elucidate the relationship between white matter alteration and cognitive status in PD and dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) by using diffusion tensor imaging. We also compared the progression patterns of white and gray matter and the cerebral perfusion. We enrolled patients with PD cognitively normal (PD‐CogNL, n = 32), PD‐MCI (n = 28), PDD (n = 25), DLB (n = 29), and age‐ and sex‐matched healthy control subjects (n = 40). Fractional anisotropy (FA) map of a patient group was compared with that of control subjects by using tract‐based spatial statistics. For the patient cohort, intersubject voxel‐wise correlation was performed between FA values and Mini‐Mental Status Examination (MMSE) scores. We also evaluated the gray matter and the cerebral perfusion by conducting a voxel‐based analysis. There were significantly decreased FA values in many major tracts in patients with PD‐MCI, PDD, and DLB, but not in PD‐CogNL, compared with control subjects. FA values in the certain white matter areas, particularly the bilateral parietal white matter, were significantly correlated with MMSE scores in patients with PD. Patients with PDD and DLB had diffuse gray matter atrophy. All patient groups had occipital and posterior parietal hypoperfusion when compared with control subjects. Our results suggest that white matter damage underlies cognitive impairment in PD, and cognitive impairment in PD progresses with functional alteration (hypoperfusion) followed by structural alterations in which white matter alteration precedes gray matter atrophy. Hum Brain Mapp, 2011. © 2011 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

Keywords: lewy body disease, diffusion tensor imaging, tomography, emission‐computed, single‐photon, dementia

INTRODUCTION

Lewy body disease is comprised of Parkinson's disease (PD) and dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB). PD has been considered, until recently, to be a pure motor disorder without cognitive impairment since it's first description by James Parkinson [Parkinson, 1817]. Now it is recognized that patients with PD can develop mild cognitive impairment (PD‐MCI) [Caviness et al., 2007], frequently progressing to PD with dementia (PDD). Cognitive impairment is one of the important nonmotor features of PD. The accumulative risk of dementia in patients with PD is six times higher than that in healthy people [Emre et al., 2007]. In contrast, DLB is defined as dementia which precedes or coincides within 1 year of the development of motor symptoms, along with concomitant features such as fluctuation of cognitive symptoms and visual hallucination [McKeith et al., 2005].

The pathological substrate for cognitive impairment in Lewy body disease remains to be elucidated. While cortical Lewy bodies, Alzheimer's disease‐type pathologies such as neurofibrillary tangles, amyloid plaque deposition, and degeneration of nucleus basalis of Meynert are suggested to play roles, there remains a discrepancy in the results [Braak et al., 2005; Colosimo et al., 2003; Mattila et al., 2000; Sabbagh et al., 2009]. Among cerebral structures, the white matter is particularly vulnerable to the postmortem effect because it contains abundant protease such as calcium‐activated neutral proteinases. In addition, neuropathological studies mainly evaluate patients with end‐stage disease, rather than patients with early‐stage or mid‐stage disease. These points limit the conclusions that can be drawn from human autopsy studies, especially for white matter pathology. Therefore, in vivo quantitative studies of white matter based on cross‐sectional and/or longitudinal design are required to examine progressive diseases such as Lewy body disease. Recently, diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) has been used to evaluate white matter in vivo in various neurological diseases based on the assumption that DTI reflects the microstructural alteration of the white matter [Dineen et al., 2009; Sage et al., 2009].

While previous DTI studies disclose various white matter alterations in Lewy body disease by using region of interest (ROI) analysis [Gattellaro et al., 2009], tract specific analysis [Ota et al., 2009], and statistical parametrical mapping (SPM) analysis [Lee et al., 2010b], their results were not comparable among subgroups of Lewy body disease. Therefore, we enrolled patients with either PD or DLB who were classified according to their cognitive status, and compared neuroimaging patterns among subgroups of Lewy body disease as a cross‐sectional study. We used a new method, tract‐based spatial statistics (TBSS), which was specifically developed to analyze DTI data. TBSS is an objective method that requires neither prespecification nor prelocalization of the ROI and automatically performs voxel‐based analyses for the whole brain between two groups. This is the first time that TBSS analysis is applied to Lewy body disease.

We also evaluated gray matter volume and cerebral perfusion by obtaining MRI structural data and iodine‐123‐N‐isopropyl‐p‐iodoamphetamine (123I‐IMP) single‐photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) data to assess the cortical thickness and the functional status of the cortex via blood circulation, respectively. While previous studies also showed alteration of white and gray matter and the cerebral perfusion in Lewy body disease, they were evaluated in separate studies, and the results could not be directly compared. Therefore, we evaluated white and gray matter and the cerebral perfusion in the same cohort to directly compare neuroimaging patterns.

In this study, we aimed to elucidate the relationship between white matter alteration and cognitive status in Lewy body disease. In addition, we compared the progression patterns of white and gray matter and the cerebral perfusion in groups with different levels of cognitive impairment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

Patients were consecutively recruited from patients attending Kanto Central Hospital in Tokyo, Japan. Healthy control subjects were recruited among friends and spouses of patients included in this study by putting up a poster. All subjects were evaluated for general and neurological examination as well as Mini‐Mental State Examination (MMSE). Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) was scored after a semistructured interview for patients and caregivers or control subjects by neurologists who were blinded to imaging data. (T.H. and S.O.).

Inclusion criteria were defined as follows. PD was diagnosed according to the clinical diagnostic criteria of the Parkinson's Disease United Kingdom Brain Bank [Hughes et al., 1992]. Information regarding memory complaint or other subjective cognitive deficits was gathered by means of a caregiver‐based interview for all patients. The diagnosis of PD‐cognitively normal (PD‐CogNL) was made based on normal cognitive function such as MMSE score ≥ 26 and CDR score = 0. These subjects did not meet criteria for PD‐MCI, PDD, or DLB as outlined below. PD‐MCI was diagnosed according to the criteria [Petersen et al., 2001]; these subjects also fulfilled MMSE score ≥ 24 and CDR score = 0.5 and did not meet the criteria for PDD and DLB outlined below. PDD and DLB were diagnosed according to the clinical diagnosis criteria for probable PDD [Emre et al., 2007] and the third consortium criteria for probable DLB [McKeith et al., 2005], respectively; these subjects also fulfilled MMSE score ≤ 26 and CDR score ≥ 0.5. The cognitive fluctuations and visual hallucinations, which were typically well formed, recurrently occurred and not attributable to other factors, were evaluated based on a careful clinical interview for DLB patient and caregivers. Normal control subjects were selected based on normal neurological examinations and normal cognitive function such as MMSE score ≥ 28 and CDR score = 0.

Exclusion criteria were defined as follows. Subjects with focal brain lesions or white matter abnormalities outside the normal range were excluded by reviewing axial fluid‐attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) scans of each subject. Patients with images that showed motion artifact were excluded. Subjects who had other brain disorders, or underlying diseases that could affect the brain such as uncontrolled hypertension and chronic kidney diseases, were excluded.

Based on the aforementioned inclusion and exclusion criteria, we enrolled 32 patients with PD‐CogNL, 28 with PD‐MCI, 25 with PDD, and 29 with DLB for the magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and SPECT studies, as well as age‐ and sex‐matched control subjects for the MRI study (n = 40) (Table I) and age‐ and sex‐matched control subjects for the SPECT study (n = 30; including 11 subjects who were also in the control group for the MRI study; age (mean ± standard deviation): 76.5 ± 6.9 years old; male:female ratios: 8:22; education: 13.6 ± 3.9 years; MMSE score: 29.2 ± 0.9; CDR score: 0; hypertension: 36.7%; diabetes mellitus: 10%; dyslipidemia: 13.3%). The Lewy body disease group included all patients with PD and DLB. All enrolled patients were examined for Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) score, classified by Hoehn‐Yahr stage (H‐Y), and evaluated by using MRI (DTI and structural data) and by using 123I‐IMP‐SPECT (the cerebral perfusion images). All clinical and neuroradiological evaluations were performed within a 6‐month interval.

Table I.

Demographic and clinical data for patients with Lewy body disease and control subjects

| Characteristics | A | B | C | D | E | P value | Post‐hoc significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (n = 40) | PD‐CogNL (n = 32) | PD‐MCI (n = 28) | PDD (n = 25) | DLB (n = 29) | |||

| Age (year) | 76.9 (4.9) | 75.9 (2.0) | 76.3 (6.4) | 80.0 (4.5) | 79.1 (5.0) | 0.037 | B,C < D* |

| Gender: M/F | 18/22 | 12/20 | 16/12 | 13/12 | 16/13 | 0.52 | |

| Disease duration (year) | NA | 5.8 (4.6) | 6.3 (4.3) | 7.8 (6.2) | 2.7 (2.9) | <0.001 | C > E*, D > E** |

| Education (year) | 14.4 (3.5) | 13.2 (3.3) | 12.2 (2.3) | 13.3 (3.3) | 15.5 (4.1) | 0.154 | |

| MMSE score | 29.0 (0.8) | 27.8 (1.5) | 25.2 (1.7) | 20.1 (3.9) | 20.7 (6.8) | <0.001 | A > B,C,D,E***, B > C,D,E***,C > D***, C > E* |

| CDR score | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 1.2 (0.5) | 1.3 (0.8) | <0.001 | A, B < C,D,E***, C < D,E*** |

| UPDRS I score | NA | 1.2 (1.3) | 2.4 (1.4) | 3.5 (2.5) | 6.5 (3.6) | <0.001 | B < C**, B < D,E***, C < E***, D < E** |

| UPDRS II score | NA | 9.3 (5.0) | 11.9 (4.9) | 14.2 (7.1) | 11.8 (10.5) | 0.108, 0.034† | B < D† |

| UPDRS III score | NA | 20.0 (8.4) | 23.9 (9.1) | 27.5 (8.9) | 23.7 (15.4) | 0.055, 0.015† | B < D†† |

| UPDRS IV score | NA | 1.3 (1.2) | 2.4 (2.6) | 1.9 (1.7) | 1.0 (1.0) | 0.205 | |

| Hoehn–Yahr stage | NA | 2.7 (0.8) | 2.7 (0.7) | 3.3 (1.1) | 2.6 (1.6) | 0.291 | |

| Vascular risk factors | |||||||

| Hypertension (%) | 35.1 | 9.4 | 17.9 | 16.0 | 27.6 | 0.89 | |

| Diabetes mellitus (%) | 5.4 | 3.1 | 0.0 | 4.0 | 13.8 | 0.19 | |

| Dyslipidemia (%) | 10.8 | 18.8 | 0.0 | 4.0 | 13.8 | 0.26 |

Results are presented as mean (standard error).

n, number; NA, not applicable; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 in the analysis comparing all groups. † P < 0.05, †† P < 0.01 in the analysis comparing PD‐CogNL, PD‐MCI, and PDD only.

Written informed consent was obtained from all patients and control subjects, and this study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Kanto Central Hospital, Japan.

MRI Acquisition Protocol

All MRI scans were acquired on the same 1.5 Tesla clinical scanner (Symphony; Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) using the standard circularly polarised quadrature birdcage coil. The DTI data was obtained with a single shot echo planar sequence (repetition time (TR) = 8,200 ms, echo time (TE) = 119 ms, b factor = 1,000 s/mm2, 12 different axes motion probing gradients, field of view (FOV) = 230 mm × 230 mm, matrix = 128 × 128, slice spacing = 3 mm with no gap, averaging = 4, number of slices = 44, total acquisition time = 7 min 31 s). A structural data, three‐dimensional‐T1 weighted (3D‐T1) MRI image, was obtained by using magnetization prepared rapid acquisition gradient echo (MPRAGE) sequence (TR = 2,150 ms, TE = 3.93 ms, TI = 1,100 ms, flip angle = 15, FOV = 230 mm × 230 mm, matrix = 256 × 256, 1 mm sagittal slices, number of slices = 160, total acquisition time = 5 min 3 s). Head motion was minimized using tightly padded clamps attached to the head coil.

SPECT Acquisition Protocol

SPECT images of subjects were obtained using a double‐head rotating gamma camera (ECAM; Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) equipped with a fan beam collimator, approximately 15 min after the bolus intravenous injection of 167 MBq of 123I‐IMP. Imaging time was 15 min (25 s/step, 36 steps). The scanner's energy setting was set at 159 keV ± 20%, and its matrix size was 128 × 128. The image voxel size was 3.30 mm/pixel with 3.59 mm slice thickness. Tomographic slices were reconstructed using a filtered back projection algorithm (butterworth filter of order 8 with a cut‐off frequency of 0.61 cycles/cm) with Chang attenuation correction.

DTI Image Processing Using TBSS

Voxel‐based analysis of the DTI data was carried out using TBSS [Smith et al., 2006] implemented in the FMRIB Software Library 4.1.5 (FSL) [Smith et al., 2004]. FA images were created after correcting the DTI images for motion and eddy current effect by using 12‐parameter affine registration to the nondiffusion volumes (b = 0). FA images of all subjects were aligned in the 1 × 1 × 1 mm3 standard Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI152) space via the FMRIB58_FA template using nonlinear registration. The mean FA image was created and thinned to create the mean FA skeleton, which represented the centers of all tracts common to the groups. This skeleton was thresholded at FA > 0.20. Each subject's aligned FA map was then projected onto this skeleton by assigning each point on the skeleton with the maximum FA in a plane perpendicular to the local skeleton structure. The resulting skeletons were fed into voxel‐wise statistic. The number of permutations was set to 5,000. Further, specific details of the analyses are given in previous report [Smith et al., 2006].

Structural Image Processing Using VBM

Structural images were analyzed with voxel‐based morphometry (VBM) implemented in FSL [Smith et al., 2004]. Nonbrain tissues were deleted from the structural images using Brain Extraction Tool (BET) [Smith, 2002] with a brain extraction factor of 0.3, and then tissue‐type segmentation was carried out using FAST4 [Zhang et al., 2001]. The resulting gray‐matter partial volume images were then aligned to MNI152 standard space using the affine registration tool FLIRT [Jenkinson et al., 2002; Jenkinson and Smith 2001], followed by nonlinear registration using FNIRT, which uses a b‐spline representation of the registration warp field [Rueckert et al., 1999]. The resulting images were averaged to create a study‐specific template, to which the native gray matter images were then nonlinearly reregistered. The registered partial volume images were modulated to correct for local expansion or contraction by dividing by the Jacobian of the warp field. The modulated segmentated images were then smoothed with an isotropic Gaussian kernel with a sigma of 3 mm. Finally, a voxelwise general linear model was applied using permutation‐based nonparametric testing, correcting for multiple comparisons across space. The number of permutations was set to 5,000.

SPECT Image Processing Using 3D‐SSP Analysis

The detailed of three‐dimensional stereotactic surface projection (3D‐SSP) is summarized elsewhere [Minoshima et al., 1995]. The 123I‐IMP SPECT data were normalized to mean global activity. The images of each patients group were compared with control subjects or other patients groups using Neurostat/3D‐SSP using an image‐analysis software, iSSP version 3.5. Two‐sample t‐tests were performed on a pixel‐by‐pixel basis and then transformed to Z values by probability integral transformation to assess the difference in regional cerebral perfusion.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis of demographic and clinical data was performed using analysis of variance with post‐hoc Turkey's HSD test for continuous variables, Kruskal–Wallis test with post‐hoc Mann–Whitney U‐tests for noncontinuous variables, and χ2 test for categorical data, by using Scientific Package for Social Sciences version 11 (SPSS, Chicago, IL). The criterion of statistical significance was P < 0.05.

FA maps and structural data of patients were compared with those of control subjects by using TBSS analysis and FSL‐VBM analysis, respectively. FA maps and structural data were compared among patients groups; age and disease duration were included in the model as covariates of no interest because there was significant difference for age and disease duration among patients groups. The significance criterion for between‐group differences was set at corrected P < 0.05; P values were corrected for multiple comparisons across voxels using the threshold‐free cluster‐enhancement (TFCE) in the “randomize” permutation‐testing tool in FSL.

For patients groups with PD, DLB, or Lewy body disease (including both PD and DLB), intersubject voxel‐wise correlation was performed between skeletal voxel FA values and MMSE scores; age and disease duration were included in the model as covariates of no interest because there was significant difference for age and disease duration among patients groups. A corrected P < 0.05 using TFCE for multiple comparisons was considered statistically significant.

In the TBSS analysis of FA maps, major connecting fibers such as the superior longitudinal fasciculus, inferior longitudinal fasciculus, inferior fronto‐occipital fasciculus, uncinate fasciculus, cingulum, and corticospinal tract were identified by using the white matter atlas that was developed at John Hopkins University and integrated into FSLView (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

TBSS analysis of FA map in Lewy body disease. All images are displayed in Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) space. The mean FA skeleton is shown in green. (A) White matter atlas. The representative mean FA skeleton was superimposed on the atlas. Copper, superior longitudinal fascicle; red, inferior longitudinal fasciculus; yellow, inferior fronto‐occipital fasciculus; dark blue, uncinate fasciculus; light blue, cingulum; purple, corticospinal tract. (B–E) Areas of significantly decreased FA values. Areas of significantly decreased FA values in patients with PD‐MCI (B), PDD (C), and DLB (D) compared with control subjects, and in patients with PDD compared with patients with PD‐CogNL (E) are shown by colors ranging from red to yellow (P < 0.05, corrected for multiple comparison by using TFCE). All images are oriented according to radiological convention (i.e., the left hemisphere of the brain corresponds to the right side of the image).

The 123I‐IMP SPECT data of each patients group was compared with that of control subjects and other patients groups by using 3D‐SSP analysis. In the SPECT study, a Z score > 3.0 (P < 0.001, uncorrected for multiple comparisons) was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Demographic and Clinical Features

The demographic and clinical features of patients and control subjects are listed in Table I. As expected from the selection procedure for control subjects, the age and gender of the control subjects were not significantly different to those of subjects in each of the patient groups. Patients with PDD were significantly older than patients with PD‐CogNL (P = 0.014) or PD‐MCI (P = 0.037). The disease duration of patients with DLB was significantly shorter than that of patients with PD‐MCI (P = 0.02) or PDD (P = 0.001). There were no significant differences in gender, education years, vascular risk factors (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and dyslipidemia) among the groups. The UPDRS part I scores were significantly higher in patients with PDD (P < 0.001), DLB (P < 0.001), and PD‐MCI (P = 0.001) compared to patients with PD‐CogNL, and in patients with DLB compared to patients with PD‐MCI (P < 0.001) or PDD (P = 0.004). The UPDRS scores for II, III, and IV and Hoehn–Yahr stage did not differ significantly among disease groups. However, the UPDRS part II and III scores were significantly higher (P = 0.017 and P = 0.006, respectively) in patients with PDD compared to patients with PD‐CogNL, when they were compared among patients with PD‐CogNL, PD‐MCI, and PDD.

White Matter Alteration Assessed by TBSS

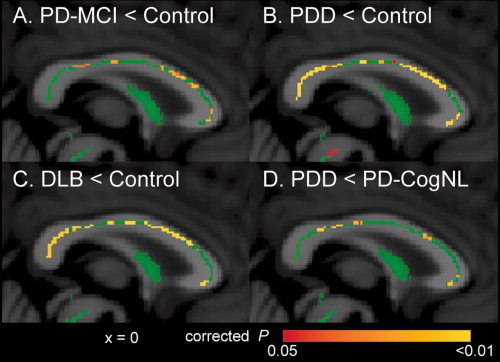

FA values were not significantly altered in the cerebral white matter in patients with PD‐CogNL compared with control subjects. In contrast, FA values were significantly decreased in the superior longitudinal fasciculus, inferior longitudinal fasciculus, inferior fronto‐occipital fasciculus, uncinate fasciculus, and cingulum in patients with PD‐MCI, PDD, and DLB compared with control subjects, and in the anterior limb of the internal capsule and substantia nigra in patients with PDD compared with control subjects (Fig. 1). FA values were significantly decreased in parts of the corpus callosum in patients with PD‐MCI, and in broad areas of the corpus callosum in patients with PDD and DLB (Fig. 2). When patients with PDD were compared with patients with PD‐CogNL, FA values were significantly decreased in the superior longitudinal fasciculus, inferior longitudinal fasciculus, inferior fronto‐occipital fasciculus, uncinate fasciculus, cingulum, and corpus callosum (Figs. 1 and 2). In contrast, FA values in the corticospinal tract were not significantly altered in any of the patients groups when compared with control subjects. There was no significant difference in FA values between patients with PD‐CogNL and PD‐MCI, between patients with PD‐MCI and PDD, or between patients with PDD and DLB.

Figure 2.

TBSS analysis of FA map in the corpus callosum in Lewy body disease. The mean FA skeleton is shown in green. Areas with significantly decreased FA values in patients with PD‐MCI (A), PDD (B), and DLB (C), compared with control subjects, and in patients with PDD compared with patients with PD‐CogNL (D) are shown by colors ranging from red to yellow (P < 0.05, corrected for multiple comparisons).

Identification of White Matter Areas Where FA Values Were Correlated With MMSE Scores

In patients with PD, significant correlations were identified between FA values and MMSE scores at the following locations: parts of the corpus callosum, superior longitudinal fasciculus, inferior longitudinal fasciculus, inferior fronto‐occipital fasciculus, uncinate fasciculus, and cingulum (Fig. 3). In patients with DLB, there were no white matter areas where FA values were correlated with MMSE scores. In patients with Lewy body disease (including both PD and DLB), significant correlations were identified between FA values and MMSE scores in almost the same areas with those listed for patients with PD above (data not shown). In particular, FA values in the bilateral parietal white matter tended to correlate strongly with MMSE scores in patients with PD and in patients with Lewy body disease.

Figure 3.

The white matter areas where FA values correlated with MMSE scores in patients with PD. (A) The mean FA skeleton is shown in green. The white matter areas where FA values were significantly correlated with Mini‐Mental State Examination (MMSE) scores in patients with PD are shown by color ranging from red to yellow (P < 0.05, corrected for multiple comparisons). All images are oriented according to radiological convention (i.e., the left hemisphere of the brain corresponds to the right side of the image). (B) Rendered version of (A).

Gray Matter Atrophy Assessed by FSL‐VBM

There was no significant gray matter atrophy in patients with PD‐CogNL or PD‐MCI compared with control subjects. In contrast, there was significant gray matter atrophy in parts of the cerebellum, bilateral thalami, insular cortex, and the parietal and occipital cortex, and in broad areas of the temporal and frontal cortex in patients with PDD and DLB when compared with control subjects (see Fig. 4). There was no significant difference in gray matter atrophy between patients with PDD and DLB.

Figure 4.

Gray matter atrophy in PDD or DLB. Areas with significant gray matter atrophy in patients with PDD (A) and DLB (B), compared with control subjects, are shown by colors ranging from red to yellow (P < 0.05, corrected for multiple comparisons). All images are oriented according to radiological convention (i.e., the left hemisphere of the brain corresponds to the right side of the image).

Cerebral Hypoperfusion Assessed by 3D‐SSP

There was significant hypoperfusion in the bilateral occipital lobe and the posterior parietal lobe in all patients groups when compared with control subjects (P < 0.001, uncorrected, Fig. 5). In addition, patients with PDD and DLB had significant hypoperfusion in the precuneus and anterior and posterior cingulate gyrus. When SPECT images of patients with DLB were compared with those of patients with PDD, the hypoperfusion in the right parietal lobe was significantly greater in patients with DLB (P < 0.001, uncorrected, Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Cerebral hypoperfusion in Lewy body disease. Areas with hypoperfusion are shown in patients with PD‐CogNL (A), PD‐MCI (B), PDD (C), and DLB (D) compared with control subjects, and in patients with DLB compared with patients with PDD (E). A Z‐score of > 3.00 (P < 0.001, uncorrected for multiple comparisons) was considered to indicate statistical significance.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first cross‐sectional study of Lewy body disease that has been conducted using TBSS analysis. This study showed progressive patterns of white matter alteration and have identified certain white matter areas, particularly the bilateral parietal white matter, where FA values were correlated with MMSE scores in patients with PD. In addition, this is also the first multimodal neuroimaging study that has evaluated white and gray matter and cerebral perfusion in the same cohort to directly compare their progression patterns. The underlying pathologies and clinical relevance are discussed later.

Decreased FA Values and Its Relevant Pathology

DTI evaluates the microstructural alterations of the white matter via water diffusion. FA values are mainly determined by the axonal membrane, and the cytoskeleton of neurofilaments and microtubules, in white matter in vivo [Beaulieu, 2002]. In general, decreased FA values indicate loss of structural integrity of white matter: that is, white matter damage. Although the pathology of white matter damage in Lewy body disease is not well elucidated, previous neuropathological studies disclose a multifaceted process of white matter damage.

First, there are small Lewy pathologies such as Lewy neurites and Lewy axons in the cerebral white matter in Lewy body disease [Braak et al., 1999; Saito et al., 2003]. In addition, there is accumulation of axonal transported substances (e.g., amyloid protein precursor, synaptophysin, chromogranin‐A and synphilin‐1) in cortical Lewy bodies, suggesting that impaired axonal transport is associated with the formation of Lewy pathology in DLB [Katsuse et al., 2003]. The above accumulated Lewy pathologies and impaired axonal transport may alter the axonal structure: for example, swelling and retrograde and/or anterograde degeneration of the axonal projection. Second, there is a significant increase in the number of neurons immunoreactive for nonphosphorylated neurofilament in the frontal and temporal cortex of patients with DLB compared with those of control subjects or patients with Alzheimer's disease [Shepherd et al., 2002]. Neurofilament proteins play an important role in maintaining axonal structure, and their altered expression may cause the abnormal axonal structure in patients with DLB. Third, there are spongiform changes in the medial temporal lobe [Saito et al., 2003], as well as demyelination, reactive gliosis, and spongiform change in the cerebrum, predominantly in the occipital white matter, in patients with DLB [Higuchi et al., 2000]. Although these findings are not always observed in both patients with PD and DLB, these multifaceted pathologies may underlie the decreased FA values in Lewy body disease.

Progression Patterns in Multimodal Neuroimaging and Its Relevant Pathology

The degenerative process in Lewy body disease remains to be elucidated. In contrast to the small number of Lewy bodies, there is an enormous number of small α‐synuclein aggregates predominantly at presynaptic terminals, as well as a complete loss of dendritic spines at the postsynaptic areas in DLB [Kramer and Schulz‐Schaeffer, 2007]. Loss of dendritic spines in postsynaptic areas is also observed in striatal medium spiny neurons in PD [Zaja‐Milatovic et al., 2005], as well as in medium spiny neurons in DLB [Zaja‐Milatovic et al., 2006]. Moreover, accumulation of axonal transported substances occurs in the initial‐stage of cortical Lewy body formation, and continues through the development of cortical Lewy body in DLB [Katsuse et al., 2003]. Alpha‐synuclein aggregates are accumulated in the distal axons of the cardiac sympathetic nervous system in the early phase of PD, followed by the accumulation of Lewy pathologies in the proximal axon or neuronal somata in the late phase of PD [Orimo et al., 2008]. These accumulating evidences support the recent hypothesis that damage in the presynaptic terminals, impaired axonal transport, and/or altered axonal structure precedes cell body damage [Mukaetova‐Ladinska and McKeith, 2006; Saito et al., 2003]. This process is also known as the “dying back” pattern of degeneration. Our neuroimaging results showed that, within the patients with PD, there was broad white matter alteration in patients with PD‐MCI and PDD, and gray matter atrophy in patients with PDD only, suggesting that white matter alteration precedes gray matter atrophy in PD. These results are consistent with the recent hypothesis of pathological progression in Lewy body disease.

Cerebral perfusion SPECT evaluates regional blood circulation, which reflects the functional status of the cortex. Here, all patients with PD groups showed occipital and posterior parietal hypoperfusion. In particular, patients with PD‐CogNL had regional hypoperfusion without significant white or gray matter alteration, suggesting that the cerebral hypoperfusion precedes the structural alteration in PD. The pathophysiology of occipital and parietal hypoperfusion in Lewy body disease is still unknown. Neuropathological studies show that the occipital and parietal cortex are relatively spared from Lewy bodies and Lewy neurites in PD [Braak et al., 2003]. However, one study using antibody for phosphorylated α‐synuclein, a sensitive and specific marker of Lewy body disease, demonstrates the presence of Lewy threads and Lewy dots with the cortical spongiosis in the occipital cortex in DLB, suggesting disrupted synaptic transmission [Saito et al., 2003]. Thus, we speculate that the presence of synaptic dysfunction, which cannot be detected by TBSS analysis in patients with PD‐CogNL, as well as white matter alteration, which was detected here by TBSS analysis in patients with PD‐MCI, PDD, or DLB, may underlie, at least in part, the occipital and posterior parietal hypoperfusion. Further, studies are needed to confirm the relationship between presynaptic dysfunction/white matter alteration and cerebral hypoperfusion.

Taken together, our results suggest that cognitive impairment in PD progresses with functional alteration (hypoperfusion) followed by structural alterations in which white matter alteration precedes gray matter atrophy.

Substrate of Cognitive Impairment in Lewy Body Disease

The pathological substrate for cognitive impairment in Lewy body disease remains to be elucidated. Although the role of cortical Lewy pathologies and/or Alzheimer's disease‐type pathologies has been suggested in many studies, there remains a discrepancy in the results [Braak et al., 2005; Colosimo et al., 2003; Mattila et al., 2000; Sabbagh et al., 2009]. As far as we know, there have been no neuropathological studies investigating the relationship between white matter damage and cognitive status in Lewy body disease. Although some MRI studies have investigated the relationship between white matter hyperintensities (WMHs) and cognitive status in Lewy body disease, the results of these studies have also been inconclusive: for example, two studies show a significant relationship between WMHs and cognitive status in PD [Beyer et al., 2006; Lee et al., 2010d], but other study shows no such relationship [Dalaker et al., 2009].

We clearly demonstrated the relationship between cognitive status and FA values in white matter in certain regions in PD. In particular, FA values in the bilateral parietal white matter were strongly correlated with MMSE scores in patients with PD. Our results support those of a previous study showing a correlation between FA values in the left parietal white matter and executive functions evaluated by Wisconsin card sorting test in patients with PD [Matsui et al., 2007]. On the other hand, FA values were not significantly correlated with MMSE scores in patients with DLB. This is presumably due to small sample size and less intragroup variability of FA values and cognitive status in DLB patients group which only includes demented subjects. Further studies, including subjects with earlier stage of DLB, are needed. As discussed earlier, it is plausible that decreased FA values indicate altered axonal structure with or without synaptic dysfunction and impaired axonal transport. Taken together, white matter alteration may underlie, at least in part, cognitive impairment in PD via the cortical–(sub)cortical disconnection, including the parietal cortex.

In addition to white matter alteration, there was significant gray matter atrophy in patients with PDD and DLB. Although our volumetric study for PD‐MCI did not show significant gray matter atrophy, some previous studies showed regional gray matter atrophy in patients with PD‐MCI [Beyer et al., 2007a; Lee et al., 2010c]. Gray matter atrophy indicates cortical cell loss. Gray matter atrophy may also be one substrate of cognitive impairment in Lewy body disease.

White Matter Alteration and Its Anatomical Identification

We used the corticospinal tract as an internal control because the corticospinal tract and motor cortex are relatively unaffected in Lewy body disease [Braak et al., 2003]. Here, FA values in the corticospinal tract were not significantly altered in any of the patients groups compared with control subjects, confirming the validity of our methodology.

White matter consists of many tracts that interconnect parts of the brain, and it play Specific roles in higher brain functions. Thus, identification of altered tracts is important to elucidate the pathophysiology of various deficits in higher brain functions in Lewy body disease. We identified decreased FA values at the following locations: the corpus callosum, superior longitudinal fasciculus, inferior longitudinal fasciculus, inferior fronto‐occipital fasciculus, uncinate fasciculus, and cingulum in patients with PD‐MCI, PDD, and DLB, as well as the anterior limb of internal capsule and substantia nigra in patients with PDD. To date, many previous studies also demonstrate decreased FA values in Lewy body disease such as in the corpus callosum and superior longitudinal fasciculus in patients with PD [Gattellaro et al., 2009], in the cingulum in patients with PD [Gattellaro et al., 2009], in the substantia nigra in patients with PD [Vaillancourt et al., 2009], in the inferior longitudinal fasciculus in patients with DLB [Kantarci et al., 2010; Ota et al., 2009], and in the corpus callosum, pericallosal areas and the frontal, parietal and occipital white matter in patients with DLB [Bozzali et al., 2005]. These results are consistent with those of our study. Clinical relevance of altered FA values is also reported in some studies: for example, decreased FA values in the parietal white matter are associated with executive dysfunction in PD [Matsui et al., 2007], as discussed earlier, and decreased FA values in the inferior longitudinal fasciculus are associated with hallucinations in DLB [Kantarci et al., 2010]. This is the first study that identified white matter areas where FA values were significantly correlated with MMSE scores in patients with PD. Further, studies are needed to elucidate the relationship between various clinical phenotype and tract specific damage in Lewy body disease.

Comparison of PDD and DLB

Recent comparative study shows that there is a gradation of neuropathologic and neurochemical characteristics in PDD and DLB and no arbitrary cut‐off between the two disorders, supporting that PDD and DLB are in the same spectrum [Ballard et al., 2006]. Although patients with PDD and DLB did not differ in the extent of white and gray matter alteration, the patients with DLB showed a trend toward having more severe gray matter atrophy than the patients with PDD, despite of their shorter disease duration. In addition, the hypoperfusion in the right parietal lobe was significantly greater in patients with DLB than in patients with PDD. To date, there are some comparative neuroimaging studies for PDD and DLB. A previous DTI study shows that FA values are significantly lower in patients with DLB than patients with PDD, in bilateral posterior temporal, posterior cingulate, and bilateral visual association fibers extending into occipital areas [Lee et al., 2010b]. The results of previous VBM studies for PDD and DLB are inconsistent: for example, one study shows no significant difference in amount of gray matter atrophy [Burton et al., 2004], but other studies show that DLB patients have significantly more gray matter atrophy than do patients with PDD [Beyer et al., 2007b; Lee et al., 2010a]. These discrepancies may be related to the different cohort characteristics (age, disease duration, disease severity, and cognitive status), or different imaging techniques and postprocessing processes in the studies. In this study, patients with PDD and DLB showed similar neuroimaging patterns with significant difference (i.e., greater hypoperfusion in the right parietal lobe in patients with DLB than patients with PDD), suggesting that PDD and DLB represent two distinct subtypes of Lewy body disease under the same pathological spectrum.

Limitations

Some limitations in our study should be addressed. First, the diagnosis of Lewy body disease was not pathologically confirmed, so there are some possibilities of misdiagnosis. Second, we did not assess detailed neuropsychological status of patients such as executive, amnestic, visuospatial, attention, and language deficits. Thus, we did not define patients with PD‐MCI based on 1.5 standard deviation below mean score in neuropsychological tests, but we defined PD‐MCI based on CDR score = 0.5. Third, although we examined white and gray matter alteration and cerebral perfusion within the same cohort, each of the methodologies used (DTI, VBM, and 3D‐SSP) has a different sensitivity and specificity for detecting abnormalities. This may limit the comparability of the findings from these different neuroimaging modalities. Further studies, such as magnetization transfer imaging to evaluate the microstructure in the gray matter, are needed to confirm our results. Fourth, while all patients were evaluated in both the MRI study and the cerebral perfusion study, only 11 control subjects were evaluated in both studies. Nineteen control subjects were independently evaluated for the cerebral perfusion study. Although it is possible that these control subjects have different cerebral perfusion from the control subjects in the MRI study, it is unlikely because these control subjects were also selected based on the same selection criteria used for the MRI study. Fifth, while this is a cross‐sectional study, longitudinal studies are also needed in order to further elucidate the progression patterns of neuroimaging in Lewy body disease.

CONCLUSIONS

This study demonstrates that Lewy body disease can have significant microstructural alteration in the cerebral white matter. In some regions of white matter, particularly the bilateral parietal white matter, FA values were significantly correlated with MMSE scores in patients with PD. These results suggest that white matter damage underlies, at least in part, cognitive impairment via the cortical‐(sub)cortical disconnection in PD.

The multimodal neuroimaging studies for PD showed occipital and posterior parietal hypoperfusion in all patients with PD groups, broad white matter alteration in PD‐MCI and PDD, and gray matter atrophy in PDD. These results suggest that cognitive impairment in PD progresses with functional alteration (hypoperfusion) followed by structural alteration in which white matter alteration precedes the gray matter atrophy. These neuroimaging findings are consistent with the recent hypothesis of pathological progression: that is, the damage in presynaptic terminal and/or neurites precedes cell body damage in PD.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Satoru Ishibashi of the Department of Neurology and Neurological Sciences, Graduate School at Tokyo Medical and Dental University for discussions. We thank the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, and Technology “Comprehensive Brain Science Network” for providing us with a good environment in which to have discussions.

REFERENCES

- Ballard C, Ziabreva I, Perry R, Larsen JP, O'Brien J, McKeith I, Perry E, Aarsland D ( 2006): Differences in neuropathologic characteristics across the Lewy body dementia spectrum. Neurology 67: 1931–1934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaulieu C ( 2002): The basis of anisotropic water diffusion in the nervous system—A technical review. NMR Biomed 15: 435–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyer MK, Aarsland D, Greve OJ, Larsen JP ( 2006): Visual rating of white matter hyperintensities in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord 21: 223–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyer MK, Janvin CC, Larsen JP, Aarsland D ( 2007a): A magnetic resonance imaging study of patients with Parkinson's disease with mild cognitive impairment and dementia using voxel‐based morphometry. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 78: 254–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyer MK, Larsen JP, Aarsland D ( 2007b): Gray matter atrophy in Parkinson disease with dementia and dementia with Lewy bodies. Neurology 69: 747–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozzali M, Falini A, Cercignani M, Baglio F, Farina E, Alberoni M, Vezzulli P, Olivotto F, Mantovani F, Shallice T, Scotti G, Canal N, Nemni R ( 2005): Brain tissue damage in dementia with Lewy bodies: An in vivo diffusion tensor MRI study. Brain 128: 1595–1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braak H, Sandmann‐Keil D, Gai W, Braak E ( 1999): Extensive axonal Lewy neurites in Parkinson's disease: A novel pathological feature revealed by alpha‐synuclein immunocytochemistry. Neurosci Lett 265: 67–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braak H, Del Tredici K, Rub U, de Vos RA, Jansen Steur EN, Braak E ( 2003): Staging of brain pathology related to sporadic Parkinson's disease. Neurobiol Aging 24: 197–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braak H, Rub U, Jansen Steur EN, Del Tredici K, de Vos RA ( 2005): Cognitive status correlates with neuropathologic stage in Parkinson disease. Neurology 64: 1404–1410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton EJ, McKeith IG, Burn DJ, Williams ED, O'Brien JT ( 2004): Cerebral atrophy in Parkinson's disease with and without dementia: A comparison with Alzheimer's disease, dementia with Lewy bodies and controls. Brain 127: 791–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caviness JN, Driver‐Dunckley E, Connor DJ, Sabbagh MN, Hentz JG, Noble B, Evidente VG, Shill HA, Adler CH ( 2007): Defining mild cognitive impairment in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord 22: 1272–1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colosimo C, Hughes AJ, Kilford L, Lees AJ ( 2003): Lewy body cortical involvement may not always predict dementia in Parkinson's disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 74: 852–856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalaker TO, Larsen JP, Dwyer MG, Aarsland D, Beyer MK, Alves G, Bronnick K, Tysnes OB, Zivadinov R ( 2009): White matter hyperintensities do not impact cognitive function in patients with newly diagnosed Parkinson's disease. Neuroimage 47: 2083–2089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dineen RA, Vilisaar J, Hlinka J, Bradshaw CM, Morgan PS, Constantinescu CS, Auer DP ( 2009): Disconnection as a mechanism for cognitive dysfunction in multiple sclerosis. Brain 132: 239–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emre M, Aarsland D, Brown R, Burn DJ, Duyckaerts C, Mizuno Y, Broe GA, Cummings J, Dickson DW, Gauthier S, Goldman J, Goetz C, Korczyn A, Lees A, Levy R, Litvan I, McKeith I, Olanow W, Poewe W, Quinn N, Sampaio C, Tolosa E, Dubois B ( 2007): Clinical diagnostic criteria for dementia associated with Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord 22: 1689–1707; quiz 1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gattellaro G, Minati L, Grisoli M, Mariani C, Carella F, Osio M, Ciceri E, Albanese A, Bruzzone MG ( 2009): White matter involvement in idiopathic Parkinson disease: A diffusion tensor imaging study. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 30: 1222–1226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higuchi M, Tashiro M, Arai H, Okamura N, Hara S, Higuchi S, Itoh M, Shin RW, Trojanowski JQ, Sasaki H ( 2000): Glucose hypometabolism and neuropathological correlates in brains of dementia with Lewy bodies. Exp Neurol 162: 247–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes AJ, Daniel SE, Kilford L, Lees AJ ( 1992): Accuracy of clinical diagnosis of idiopathic Parkinson's disease: A clinico‐pathological study of 100 cases. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 55: 181–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkinson M, Smith S ( 2001): A global optimisation method for robust affine registration of brain images. Med Image Anal 5: 143–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkinson M, Bannister P, Brady M, Smith S ( 2002): Improved optimization for the robust and accurate linear registration and motion correction of brain images. Neuroimage 17: 825–841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantarci K, Avula R, Senjem ML, Samikoglu AR, Zhang B, Weigand SD, Przybelski SA, Edmonson HA, Vemuri P, Knopman DS, Ferman TJ, Boeve BF, Petersen RC, Jack CR, Jr. ( 2010): Dementia with Lewy bodies and Alzheimer disease: Neurodegenerative patterns characterized by DTI. Neurology 74: 1814–1821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katsuse O, Iseki E, Marui W, Kosaka K ( 2003): Developmental stages of cortical Lewy bodies and their relation to axonal transport blockage in brains of patients with dementia with Lewy bodies. J Neurol Sci 211: 29–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer ML, Schulz‐Schaeffer WJ ( 2007): Presynaptic alpha‐synuclein aggregates, not Lewy bodies, cause neurodegeneration in dementia with Lewy bodies. J Neurosci 27: 1405–1410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JE, Park B, Song SK, Sohn YH, Park HJ, Lee PH ( 2010a): A comparison of gray and white matter density in patients with Parkinson's disease dementia and dementia with Lewy bodies using voxel‐based morphometry. Mov Disord 25: 28–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JE, Park HJ, Park B, Song SK, Sohn YH, Lee JD, Lee PH ( 2010b): A comparative analysis of cognitive profiles and white‐matter alterations using voxel‐based diffusion tensor imaging between patients with Parkinson's disease dementia and dementia with Lewy bodies. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 81: 320–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JE, Park HJ, Song SK, Sohn YH, Lee JD, Lee PH ( 2010c): Neuroanatomic basis of amnestic MCI differs in patients with and without Parkinson disease. Neurology 75: 2009–2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SJ, Kim JS, Yoo JY, Song IU, Kim BS, Jung SL, Yang DW, Kim YI, Jeong DS, Lee KS ( 2010d): Influence of white matter hyperintensities on the cognition of patients with Parkinson disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 24: 227–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsui H, Nishinaka K, Oda M, Niikawa H, Komatsu K, Kubori T, Udaka F ( 2007): Wisconsin card sorting test in Parkinson's disease: Diffusion tensor imaging. Acta Neurol Scand 116: 108–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattila PM, Rinne JO, Helenius H, Dickson DW, Roytta M ( 2000): Alpha‐synuclein‐immunoreactive cortical Lewy bodies are associated with cognitive impairment in Parkinson's disease. Acta Neuropathol 100: 285–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKeith IG, Dickson DW, Lowe J, Emre M, O'Brien JT, Feldman H, Cummings J, Duda JE, Lippa C, Perry EK, Aarsland D, Arai H, Ballard CG, Boeve B, Burn DJ, Costa D, Del Ser T, Dubois B, Galasko D, Gauthier S, Goetz CG, Gomez‐Tortosa E, Halliday G, Hansen LA, Hardy J, Iwatsubo T, Kalaria RN, Kaufer D, Kenny RA, Korczyn A, Kosaka K, Lee VM, Lees A, Litvan I, Londos E, Lopez OL, Minoshima S, Mizuno Y, Molina JA, Mukaetova‐Ladinska EB, Pasquier F, Perry RH, Schulz JB, Trojanowski JQ, Yamada M ( 2005): Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: Third report of the DLB Consortium. Neurology 65: 1863–1872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minoshima S, Frey KA, Koeppe RA, Foster NL, Kuhl DE ( 1995): A diagnostic approach in Alzheimer's disease using three‐dimensional stereotactic surface projections of fluorine‐18‐FDG PET. J Nucl Med 36: 1238–1248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukaetova‐Ladinska EB, McKeith IG ( 2006): Pathophysiology of synuclein aggregation in Lewy body disease. Mech Ageing Dev 127: 188–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orimo S, Uchihara T, Nakamura A, Mori F, Kakita A, Wakabayashi K, Takahashi H ( 2008): Axonal alpha‐synuclein aggregates herald centripetal degeneration of cardiac sympathetic nerve in Parkinson's disease. Brain 131: 642–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ota M, Sato N, Ogawa M, Murata M, Kuno S, Kida J, Asada T ( 2009): Degeneration of dementia with Lewy bodies measured by diffusion tensor imaging. NMR Biomed 22: 280–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkinson J ( 1817): An Essay on the Shaking Palsy. London: Sherwood, Neely, and Jones. [Google Scholar]

- Petersen RC, Smith GE, Waring SC, Ivnik RJ, Tangalos EG, Kokmen E ( 1999): Mild cognitive impairment: Clinical characterization and outcome. Arch Neurol 56: 303–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rueckert D, Sonoda LI, Hayes C, Hill DL, Leach MO, Hawkes DJ ( 1999): Nonrigid registration using free‐form deformations: Application to breast MR images. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 18: 712–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabbagh MN, Adler CH, Lahti TJ, Connor DJ, Vedders L, Peterson LK, Caviness JN, Shill HA, Sue LI, Ziabreva I, Perry E, Ballard CG, Aarsland D, Walker DG, Beach TG ( 2009): Parkinson disease with dementia: comparing patients with and without Alzheimer pathology. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 23: 295–297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sage CA, Van Hecke W, Peeters R, Sijbers J, Robberecht W, Parizel P, Marchal G, Leemans A, Sunaert S ( 2009): Quantitative diffusion tensor imaging in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: Revisited. Hum Brain Mapp 30: 3657–3675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito Y, Kawashima A, Ruberu NN, Fujiwara H, Koyama S, Sawabe M, Arai T, Nagura H, Yamanouchi H, Hasegawa M, Iwatsubo T, Murayama S ( 2003): Accumulation of phosphorylated alpha‐synuclein in aging human brain. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 62: 644–654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd CE, McCann H, Thiel E, Halliday GM ( 2002): Neurofilament‐immunoreactive neurons in Alzheimer's disease and dementia with Lewy bodies. Neurobiol Dis 9: 249–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SM ( 2002): Fast robust automated brain extraction. Hum Brain Mapp 17: 143–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SM, Jenkinson M, Woolrich MW, Beckmann CF, Behrens TE, Johansen‐Berg H, Bannister PR, De Luca M, Drobnjak I, Flitney DE, Niazy RK, Saunders J, Vickers J, Zhang Y, De Stefano N, Brady JM, Matthews PM ( 2004): Advances in functional and structural MR image analysis and implementation as FSL. Neuroimage 23 ( Suppl 1): S208–S219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SM, Jenkinson M, Johansen‐Berg H, Rueckert D, Nichols TE, Mackay CE, Watkins KE, Ciccarelli O, Cader MZ, Matthews PM, Behrens TE ( 2006): Tract‐based spatial statistics: Voxelwise analysis of multi‐subject diffusion data. Neuroimage 31: 1487–1505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaillancourt DE, Spraker MB, Prodoehl J, Abraham I, Corcos DM, Zhou XJ, Comella CL, Little DM ( 2009): High‐resolution diffusion tensor imaging in the substantia nigra of de novo Parkinson disease. Neurology 72: 1378–1384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaja‐Milatovic S, Milatovic D, Schantz AM, Zhang J, Montine KS, Samii A, Deutch AY, Montine TJ ( 2005): Dendritic degeneration in neostriatal medium spiny neurons in Parkinson disease. Neurology 64: 545–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaja‐Milatovic S, Keene CD, Montine KS, Leverenz JB, Tsuang D, Montine TJ ( 2006): Selective dendritic degeneration of medium spiny neurons in dementia with Lewy bodies. Neurology 66: 1591–1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Brady M, Smith S ( 2001): Segmentation of brain MR images through a hidden Markov random field model and the expectation‐maximization algorithm. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 20: 45–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]