Abstract

Visual perception can be strongly biased due to exposure to specific stimuli in the environment, often causing neural adaptation and visual aftereffects. In this study, we investigated whether adaptation to certain body shapes biases the perception of the own body shape. Furthermore, we aimed to evoke neural adaptation to certain body shapes. Participants completed a behavioral experiment (n = 14) to rate manipulated pictures of their own bodies after adaptation to demonstratively thin or fat pictures of their own bodies. The same stimuli were used in a second experiment (n = 16) using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) adaptation. In the behavioral experiment, after adapting to a thin picture of the own body participants also judged a thinner than actual body picture to be the most realistic and vice versa, resembling a typical aftereffect. The fusiform body area (FBA) and the right middle occipital gyrus (rMOG) show neural adaptation to specific body shapes while the extrastriate body area (EBA) bilaterally does not. The rMOG cluster is highly selective for bodies and perhaps body parts. The findings of the behavioral experiment support the existence of a perceptual body shape aftereffect, resulting from a specific adaptation to thin and fat pictures of one's own body. The fMRI results imply that body shape adaptation occurs in the FBA and the rMOG. The role of the EBA in body shape processing remains unclear. The results are also discussed in the light of clinical body image disturbances. Hum Brain Mapp 34:3233–3246, 2013. © 2012 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

Keywords: adaptation, body image, body shape, fMRI, fusiform body area, middle occipital gyrus, extrastriate body area, eating disorders, body image disturbances

INTRODUCTION

In its psychophysical meaning, adaptation is the prolonged exposure to a specific stimulus or several similar stimuli. Such an adaptation often leads to alterations and biases in visual perception, causing an aftereffect. Earlier studies investigating aftereffects were restricted to low‐level properties of visual objects like movement [Levinson and Sekuler, 1976], color [McCollough, 1965] or line orientation [Gibson and Radner, 1937]. The authors of these studies found that adaptation to a specific stimulus resulted in a perceptual bias in the opposite direction of the adaptation stimulus. Thus aftereffects strongly influence perception and “reveal a gap between appearance and reality, and remind us that what we see is determined by how visual information is coded in the brain, and not simply by how things ‘really are’” [Georgeson, 2004, p R751].

However, aftereffects are not restricted to low‐level stimulus properties. Yet, there have been many studies investigating aftereffects in the field of face perception. These studies found that adaptation to a specific facial property like gender [Little et al., 2005; Webster et al., 2004], ethnicity [Ng et al., 2008; Webster et al., 2004] or emotional expression [Fox and Barton, 2007; Webster et al., 2004] also causes property‐specific aftereffects.

There have also been studies investigating visual adaptation to unfamiliar bodies, especially to pictures of thin and fat body shapes. Winkler and Rhodes 2005 found that the most attractive and most normal appearing bodies became thinner after adaptation to thin bodies (i.e., narrowed photographs of unfamiliar bodies). The most normal looking bodies changed after adaptation to fat bodies, while the most attractive bodies did not. Glauert et al. 2009 could replicate these findings using more realistic body pictures (i.e., computer‐generated models of a female body representing certain body mass indexes). These results show that body perception can be easily manipulated via adaptation, demonstrating a possible mechanism for the development and perpetuation of clinical body image disturbances (see below).

The generally accepted explanation for aftereffects is that detector neurons tuned to the perception of a specific stimulus adapt as a result of prolonged exposure to this specific stimulus and consequently reduce their activity and/or change their tune [for a review, see Thompson and Burr, 2009]. Proof for this has been found for basic visual stimuli [for a review, see Kohn, 2007] as well as for more complex stimuli, especially for faces [e.g., Fang et al., 2007; Furl et al., 2007; Ng et al., 2006]. These modulations of neural activity due to face adaptation were found in face selective brain areas or in brain areas associated with complex visual object processing (downstream of V1/V2). It has also been shown that adaptation to specific properties of face stimuli like ethnicity, gender or even gaze direction causes dissociable modulations in neural activity [Calder et al., 2007; Ng et al., 2006].

Studies investigating face aftereffects via neuroimaging methods demonstrate that adaptation to higher order visual stimuli leads to changes in neural activity in brain areas sensitive for the respective stimuli, raising the question whether there are also adaptation effects in brain areas responsible for the perception of the human body. These brain areas are the extrastriate body area [EBA, Downing et al., 2001] in the lateral occipitotemporal cortex and the fusiform body area [FBA, Peelen and Downing, 2005; Schwarzlose et al., 2005] in the fusiform gyrus.

In fact, there have been several studies investigating adaptation to bodily properties in the EBA and FBA. For example, Aleong and Paus 2010 found higher right versus left hemispheric neural responses in the EBA and FBA among women but not men, demonstrating a gender specific functional lateralization with regard to body perception. Ewbank et al. 2011 found neural adaptation effects in the EBA and FBA for identical pictures of the same body that were unaffected by changes in body size or view. Their analyses of effective connectivities suggest that these effects are mostly driven by changes in top–down modulation (FBA‐to‐EBA). Taylor et al. 2007 could show that EBA and FBA also adapt to identical views of the same body pose, although these adaptation effects were eliminated when the body stimuli were followed by a pattern mask.

A distorted body image is a diagnostic criteria for several mental diseases in DSM‐IV‐TR [American Psychiatric Association, 2000], especially for eating disorders like anorexia nervosa (AN) and bulimia nervosa (BN) as well as for body dismorphic disorders. Anorectic and bulimic patients usually exhibit an overestimation of the own body size or body shape [Cash and Deagle, 1997]. The exact mechanism behind this aberrant perception of the own body in clinical disorders still needs to be clarified [for a discussion, see Smeets and Kosslyn, 2001; Smeets et al., 2009]. However, there is growing evidence from neuroimaging studies that patients with AN and BN process pictures of their own bodies and pictures of unfamiliar bodies differently than healthy controls [Miyake et al., 2010; Mohr et al., 2009, 2011; Spangler and Allen, 2011; Uher et al., 2005; Vocks et al., 2010; Wagner et al., 2003].

As mentioned above, visual perception can be strongly affected by adaptation and aftereffects. Dependent on adaptation duration, such experimentally induced perceptual aftereffects could bias the visual experience for a long time, e.g., more than 2 weeks for the tilt aftereffect [Wolfe and Connell, 1986] or one month for color sensitization [Tseng et al., 2004]. Furthermore, there is increasing evidence that aftereffects can be strongly affected by selective attention [e.g., Liu et al., 2007] and even that they can solely be induced by mental imagery [Mohr et al., 2009]. Thus, a possible mechanism to induce a persistent body image distortion of clinical relevance could be a perceptual aftereffect, caused by ongoing selective attention toward disorder‐relevant stimuli like body shape or size [for a review of selective attention in eating disorders, see Dobson and Dozois, 2004; Williamson et al., 1999].

If the neural correlates of adaptation to bodily properties like shape can be identified in healthy subjects, and if—in a subsequent step—certain similarities or differences concerning the neural adaptation in specific brain areas can be found in healthy subjects and participants suffering from eating disorders, this might shed light on the nature of body image disturbances in terms of eating disorders.

In regard to the aforementioned findings and the relevance of the own body shape in eating disorders, the aim of this study with a healthy sample was to examine whether a psychophysical adaptation to thin and fat pictures of one's own body (1) biases the perception and judgment of the own body shape and (2) also leads to a specific neural adaptation, especially in visual brain areas selective for bodies (EBA and FBA). We decided to use pictures of the participants' own bodies for both adaptation and test stimuli to keep the variability between both stimulus categories at a minimum.

We designed a behavioral experiment to test for similar perceptual biases due to adaptation to thin and fat bodies as found by Winkler and Rhodes 2005 and Glauert et al. 2009. While the aforementioned studies used pictures of unfamiliar bodies as adaptation and test stimuli, we used pictures of the participants' own bodies as adaptation and test stimuli. We argue for the hypothesis that the enduring exposure to thin or fat pictures of the own body alters the way a participant perceives and judges subsequently shown pictures of her or his own body in terms of an aftereffect: after adaptation to a thin picture a participant should perceive subsequently shown pictures of her or his own body as being fatter than actual and vice versa.

In the main experiment, healthy participants adapted to distorted pictures of the own body while undergoing functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) measurements. Importantly, the adaptation stimuli in this fMRI experiment were completely comparable to those used in the aforementioned behavioral experiment. In this way, a possible neural adaptation to similar stimuli which evoked behavioral aftereffects in the first experiment should be observable. We hypothesized that a specific adaptation to thin and fat pictures of the own body should lead to a decreased activity in body selective areas (EBA and FBA). For this reason, we performed a whole brain analysis as well as a specific regions‐of‐interest (ROI) analysis to identify perceptual brain areas associated with body shape adaptation and processing.

To our knowledge, this is the first attempt to investigate neural adaptation to specific body shapes. In the following methods section we will first focus on the behavioral experiment. After that, the methods of the main (fMRI) experiment are presented in separate subsections.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Behavioral Experiment

Fourteen healthy adult volunteers (five males) were recruited and participated in the behavioral experiment. The mean age was 22.6 years (SD = 4.4, range = 19–36 years). For each participant the body mass index (BMI) was calculated, which resulted in a mean BMI of 20.8 (SD = 1.4, range = 18.1–23.6). All participants had normal or corrected‐to‐normal vision. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants after written and verbal briefing concerning task instructions. Both experiments (behavioral and fMRI) have been approved by the ethics commission of the Goethe University Medical School, Frankfurt, Germany, and are in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

A digital photograph of each participant was created on a monotonous, white‐colored background in a standardized pose (standing upright, feet approximately as wide as the shoulders, arms spread horizontally). The photograph showed the participant's whole body but omitted the head. Feet and forearms were also cropped as these body parts were not manipulated by the software (see below). Participants wore standardized clothes, namely a black t‐shirt and black leggings. The clothes were available in several sizes to make sure they would fit tightly to the body shape.

We used the software “Body Form Imaging” [Sands et al., 2004] to manipulate the digital picture of each participant. Different body “zones” (shoulders, chest, belly, hips, thighs, and calves) were jointly distorted in several steps. In the behavioral experiment we created the following pictures for each participant: 10 fatter pictures (distortion from +1 to +10 steps of the original picture) and 10 thinner pictures (distortion from −1 to −10 steps of the original picture) as well as the original picture, resulting in a total of 21 pictures.

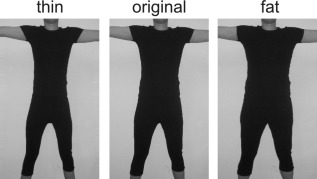

For these body pictures one step resembles ∼1% increase or decrease of the body surface shown in a picture. To maintain a preferably realistic proportioned body shape (although a participant was depicted unrealistically thin or fat), the used software package for manipulating the body pictures could not provide pictures with a distinct step width for the body shape as a whole (i.e., an exact percentage of surface increase or decrease). Nonetheless, the stimuli used in this study have been proven to be useful and adequate stimuli in previous experiments [Mohr et al., 2009, 2011]. Figure 1 displays the adaptation stimuli as well as the original picture of one sample participant.

Figure 1.

Examples for the adaptation stimuli in comparison with the original picture.

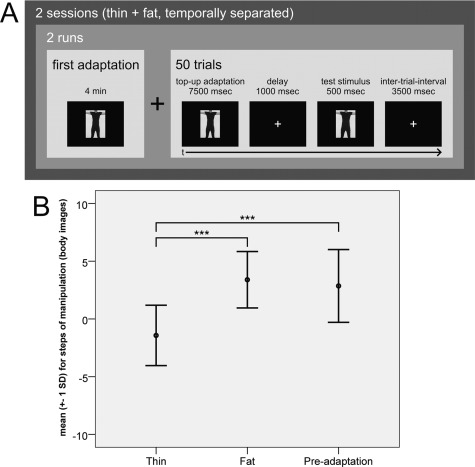

Each participant completed two adaptation sessions (thin adaptation and fat adaptation, temporally separated). Each adaptation session consisted of two runs and each run included an initial adaptation phase (4 min) and 50 rating trials. One trial included a top‐up adaptation (7,500 ms), a delay with fixation cross (1,000 ms), a test stimulus (500 ms) and an intertrial interval with fixation cross (3,500 ms). A top‐up adaptation of several seconds is common in adaptation experiments and has been used in studies investigating adaptation to bodily properties [Glauert et al. 2009; Winkler and Rhodes, 2005] and face adaptation [e.g., Fox and Barton, 2007; Webster and MacLin, 1999; Webster et al., 2004]. Test stimuli presentation had such a short duration to avoid adaptation effects other than those caused by the adaptation stimuli. We chose to include an initial adaptation of long duration to enhance possible adaptation effects. The design of the behavioral experiment with stimulus durations etc. is depicted in Figure 3A (see Results section). The adaptation stimuli were the participant's own body pictures at +8 steps of distortion (fat adaptation) or −8 steps of distortion (thin adaptation), respectively. These two sessions were temporally separated by at least one week to minimize possible adaptation effects from the first session during the second session. The order of adaptation sessions was counterbalanced.

Figure 3.

Design and results of the behavioral adaptation experiment. A: Design of the experiment (initial adaptation +50 trials = one run; two runs = one session) and of one trial in particular. B: Means (SD) of the participants' rating in the three experimental conditions. Significant one‐sampled t‐tests for thin adaptation vs. fat adaptation (n = 14, t = ‐8.274, P < 0.001) and for thin adaptation vs. preadaptation rating (n = 14, t = −5.326, P < 0.001) but not for fat adaptation vs. preadaptation rating (n = 14, t = 0.620, P = 0.546).

Using a staircase paradigm, the 21 body pictures were integrated into two alternating staircases, one starting with the body picture at +8 steps of distortion and the other starting with the body picture at −8 steps of distortion. After each test stimulus the participants judged whether they were actually fatter or thinner than the test stimulus by pressing one of two response buttons. By taking the turning points (a turning point is reached each time a participant changes her or his response direction) and their corresponding pictures from the raw data, we could identify the pictures which were judged to be the most realistic by the participants by calculating the median of all turning points per condition. We chose to report the median because we could not guarantee distinct step widths for the manipulated body pictures (see above).

To minimize aftereffects generated solely by low‐level properties, the stimuli for first adaptation and later top‐up adaptation were tilted 0°, ±2°, ±4°, ±6°, ±8°, and ±10° clockwise or counterclockwise, respectively. In the initial adaptation the tilt degree randomly changed within a temporal scale from 2,000 to 3,450 ms. In this way, the retinal image changed every few seconds. In the top‐up adaptation the tilt degree changed four times randomly every 1,875 ms. Furthermore, there were no restrictions to eye movements. Participants were told in advance that they would examine and rate more or less distorted pictures of their own bodies. The experiment was programmed and presented using the software “Presentation” (Neurobehavioral Systems, Albany, USA).

According to our hypothesis, after adaptation to a thinner than actual body picture, participants should perceive subsequently shown test stimuli as fatter than they really are and consequently judge a thinner than actual test stimulus to be the most realistic and vice versa. Thus, the pictures judged to be the most realistic ones should differ significantly as a result of adaptation direction and turning points should generally correspond to thinner body pictures after adaptation to the thin body picture than after adaptation to the fat body picture.

All participants also completed an additional task in which they had to rate their own body pictures without any previous adaptation, consisting of 100 rating trials in a staircase‐paradigm. This task always was accomplished prior to the adaptation experiment and was similar to the latter, except for omitting the adaptation. We will refer to the results of this task as the preadaptation rating. To exclude any training effects or the like, half of the participants completed this preadaptation rating prior to the first session and the other half prior to the second session. We hypothesized that the preadaptation rating should lie between the seemingly most realistic body pictures after adaptation to thin or fat body pictures and should furthermore significantly differ from both of these.

Participants in the fMRI Experiment

Sixteen healthy adult volunteers (four males) participated in the fMRI experiment. Three participants (two males) had also completed the former behavioral experiment. The mean age was 25.0 years (SD = 5.5 years, range = 20–44 years). Participants had a mean BMI of 22.1 (SD = 3.0, range = 18.2–28.7). Furthermore, all participants of the fMRI experiment completed the German version of the Eating Disorder Examination‐Questionaire [EDE‐Q, Hilbert and Tuschen‐Caffier, 2006]. This questionnaire has been included because body image disturbances are a major aspect in eating disorders like Anorexia nervosa or Bulimia nervosa [Bruch, 1962; Cash and Deagle, 1997]. The validity of the German version in comparison to the English version by Fairburn and Beglin 1994 has been approved by Hilbert et al. 2006. The mean for the total score of the EDE‐Q was 0.67 (SD = 0.37, range = 0.11–1.68), indicating that none of the participants suffered from an eating disorder (Anorexia nervosa, Bulimia nervosa, or atypical eating disorder).

All participants had normal or corrected‐to‐normal vision. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants after a written and verbal briefing concerning MRI safety and task instructions.

Stimuli

For each participant of the fMRI experiment, the following three pictures were created in the same way as in the behavioral experiment (see above): one thinner than actual picture (distortion at −8 steps of the original picture) and one fatter than actual picture (distortion at +8 steps of the original picture) as well as the original picture, resulting in a total of three pictures (see Fig. 1).

Adaptation Experiment

Each participant completed two adaptation sessions. The adaptation stimuli were the participant's own body pictures at +8 steps of distortion (fatter than actual) or −8 steps of distortion (thinner than actual), respectively. Importantly, these were the same adaptation stimuli as used in the behavioral experiment. The two sessions were temporally separated by at least 1 week to minimize possible adaptation effects from the first session during the second session. The order of adaptation sessions was counterbalanced.

The adaptation experiment in each of the two sessions consisted of six runs. Runs 1, 3, and 5 were pure adaptation runs and in the following we will refer to these runs as “initial adaptation runs.” Runs 2, 4, and 6 contained a recurring top‐up adaptation and the test conditions and in the following we will refer to these runs as “test runs.” In each adaptation session, the respective adaptation stimulus stayed the same throughout the initial adaptation and test runs. For example, if a participant adapted to her or his thinner than actual body picture (−8 steps), then this picture was presented as the adaptation stimulus in the initial adaptation runs (1, 3, and 5) and as a top‐up adaptation in the test runs (2, 4, and 6). In the test conditions of each test run either the thinner than actual body picture (now adapted condition) or the fatter than actual body picture (now nonadapted condition) was presented. We therefore have a 2 × 2 experimental design, including factors condition (thin and fat) and state (adapted and nonadapted). Although this design is rather uncommon [for a review of fMRI adaptation designs, see Weigelt et al., 2008], we chose this particular design to comprise a strong psychophysical adaptation (i.e., long initial adaptation runs interleaved with test runs including a recurring top‐up adaptation) and to maximize neural adaptation in case that these neural adaptation effects might be generally weak. To this end, we chose a block design and included the initial adaptation runs and the temporal break between adaptation sessions. Moreover, separating the experimental conditions into two factors gave us the opportunity to search for possible interactions of body shapes and neural response.

In the initial adaptation runs, a body picture (adaptation stimulus) of the respective participant was constantly presented for 4 min. This body picture could either be the thinner than actual or the fatter than actual picture, respectively, depending on the adaptation session. To minimize aftereffects generated solely by low‐level properties, the stimuli for initial adaptation and later top‐up adaptation were tilted 0°, ±2°, ±4°, ±6°, ±8°, and ±10° clockwise or counterclockwise, respectively. In the initial adaptation runs, the tilt degree of the adaptation stimulus randomly changed within a temporal scale from 1,000 to 1,726 ms. That way, the retinal image changed every few seconds. Participants were instructed to fixate a fixation cross or—if no fixation cross was presented—the center of the screen. To control for the participants' attention, the original (not manipulated) body picture was pseudorandomly presented 11 times in each initial adaptation run among the tilted versions of the adaptation stimuli. The participants were instructed to press a response button every time they saw this original picture. We chose this task to maintain the participants' attention specifically on the presented body shapes. No fMRI measurements were taken during the initial adaptation runs.

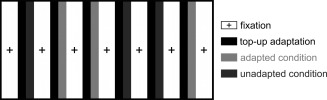

For the test runs we used a block design with 13 blocks in each run. Each block lasted for 24 s. Blocks 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, and 13 were fixation blocks, showing a black fixation cross on a monotonous white background. Blocks 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12 were test blocks. Here, the same adaptation stimulus as used in the initial adaptation runs was presented during the first half of each test block (first 12 s) as a top‐up adaptation. During the second half of each test block (last 12 s) either the thinner than actual or the fatter than actual body picture was presented as a test stimulus (adapted vs. nonadapted). The second halves represent the test conditions. Figure 2 shows an exemplary configuration of a test run.

Figure 2.

Example for a test run in the fMRI adaptation experiment. Stimulation blocks are interleaved with fixation blocks. The first half of each block serves as a top‐up adaptation while the second half of each block represents the test condition.

The test conditions (second half of each test block) were presented pseudorandomly. Again, the orientation of the adaptation and test stimuli changed every 1,090 ms in the same tilt degrees as used in the initial adaptation runs. The attention task also was the same as in the initial adaptation runs: the original body picture was pseudorandomly presented one time during the first half, the second half or both halves of each block (in total eight times in one run). Participants were instructed that they would observe more or less distorted pictures of their own bodies and that they had to press a button every time the original picture was presented. Both the adaptation experiment as well as the localizer experiment (see below) were programmed and presented using the software “Presentation” (Neurobehavioral Systems, Albany, USA).

Localizer Experiment

The localizer experiment for identifying brain areas sensitive to visual body perception was of a block design and consisted of two identical runs, each containing 26 blocks. The stimulus categories were (a) pictures of bodies (photographs, line drawings, 3D models, all spearing the head), (b) scrambled pictures of the same bodies (mixing up each picture in squares of 30 × 30 pixels), (c) pictures of emotionally neutral faces, and (d) German body shape related words (e.g., thin, fat, voluptuous, and skinny). These body shape related words were included for further investigations concerning a behavioral experiment accomplished in our workgroup (unpublished results). Because these experiments were associated with other components of the body image, the results of the word condition are not discussed in the present article. Each block lasted for 18 s. Blocks 1, 6, 11, 16, 21, and 26 were fixation blocks, presenting a black fixation cross on a monotonous white background. The remaining blocks were stimulation blocks, showing 24 stimuli for 300 ms each with an interstimulus interval (ISI) of 450 ms. All pictures were converted to gray scale and matched for picture size across stimulus categories. The sequence of the stimulus blocks was pseudorandomized. To control for attention, participants had to press a response button every time a stimulus (picture or word) was consecutively presented twice (one‐back task). This pseudorandomly happened twice in each block. The localizer experiment was completed after the adaptation experiment in one of the two sessions.

MRI Procedure

Visual images were projected onto a removable screen at the rearmost end of the MR bore (Sony data beamer, VPL‐XP20, 1400 ANSI). MR images were acquired using a 3T Siemens Magnetom Allegra Scanner (Siemens Medical Systems, Erlangen, Germany) using a standard eight‐channel head coil. During the adaptation and localizer experiments, 20 oblique axial slices (in‐plane resolution = 3.3 × 3.3 mm, slice thickness = 5 mm, interslice distance = 1 mm) covering the entire cortical volume were acquired using a T2*‐weighted echo planar imaging (EPI) sequence [repetition time (TR) = 1,200 ms, echo time (TE) = 30 ms, flip angle (FA) = 85°, field of view = 192 mm]. We obtained 270 functional volumes for each test run in the adaptation experiment (resulting in a total of 1,620 volumes for the adaptation experiments of both sessions) and 400 functional volumes for each run in the localizer experiment (resulting in a total of 800 volumes for the localizer experiment). The first two volumes of each functional run were discarded to account for T1 saturation effects. High‐resolution anatomical volumes using a T1‐weighted three‐dimensional (3D) magnetization prepared rapid acquisition gradient echo (MP‐RAGE) sequence (TR = 2,250 ms, TE = 2.6 ms, resolution = 1 mm3, 144 or 160 slices) were acquired prior to the first initial adaptation run for co‐registration with the functional data.

Data Analysis

The functional and anatomical images were analyzed using the “Brainvoyager QX” software package (Brain Innovation, Maastricht, The Netherlands). Data preprocessing included a slice scan time correction using syncinterpolation, 3D motion correction using rigid body transformations, spatial smoothing with a 4‐mm Gaussian kernel (full‐width at half‐maximum), temporal high‐pass filtering to remove low‐frequency nonlinear drifts of two or fewer cycles per time course and linear trend removal. The functional data were subsequently co‐registered with the anatomical scans and transformed into Talairach space [Talairach and Tournoux, 1988] for each subject.

For the localizer experiment fixed effect (FFX) general linear models (GLMs) were computed from the two localizer volume time courses (two localizer runs) for each participant separately. The blood oxygen level‐dependent (BOLD) was modeled using a two‐gamma hemodynamic response function (HRF). Four conditions or predictors were defined, representing the four stimulus categories used in the experiment (bodies, scrambled bodies, faces, and words). A specific contrast of bodies (+1) vs. faces (−0.5) and scrambled bodies (−0.5) were used to locate brain areas sensitive to visual body perception, namely the EBA and FBA. We chose this contrast and the inclusion of faces over a more common contrast (e.g., bodies vs. objects) with the intention to identify voxels that are clearly body selective and thus are significantly more activated by bodies than by faces. In this way, we hoped to locate clusters consistent of voxels which would be selective for the processing of strict bodily properties like body shape. More precisely, the FBA has been shown to overlap with the fusiform face area (FFA). However, both functional ROIs can be separated by their specific response to bodies or faces, respectively [see Schwarzlose et al., 2005]. For each of these three areas (left and right EBA and right FBA), a cluster of about the most significant 200 voxels was identified as a ROI in each participant. The criteria for these ROIs were both spatial proximity to reference anatomical areas in the literature [e.g., Downing et al., 2001; Peelen and Downing, 2005; Schwarzlose et al., 2005] and an interpretable BOLD signal time course for every type of stimulus. In this way, we obtained ROIs for the left and right EBA in all participants and the FBA (right hemisphere) in all but two participants, resulting in a total of 46 ROIs.

For the adaptation experiment a second‐level random effects (RFX) GLM was calculated from 96 volume time courses (16 participants × 3 runs × 2 sessions). BOLD again was modeled using a two‐gamma HRF. The top‐up adaptation (first half of each block) was set to a separate predictor to exclude it from the baseline (fixation blocks), but was not used for further analyses. The analysis of the second‐level RFX GLM was based on the factors condition (thin and fat) and state (adapted and nonadapted). We conducted F‐tests for a main effect of state and for an interaction of condition x state (a main effect for condition was not further analyzed because we did not formulate a specific hypothesis for such an effect). Statistical threshold was set to P < 0.001, uncorrected, cluster size threshold at 5 voxels. We also calculated a whole brain RFX GLM for the localizer scans across all 16 participants to test for body selectivity in clusters which would be revealed by the whole brain RFX GLM of the adaptation experiment.

For a further ROI analysis, we obtained the raw BOLD signal for each predictor from each of the 46 ROIs defined. Again, a repeated measures 2 × 2 ANOVA with F‐tests for a main effect of state and for an interaction of condition x state as well as post‐hoc t‐tests were performed on the extracted raw signals using SPSS Statistics 19 (IBM Corp., Armonk, USA). The ANOVA was accomplished for left and right EBA and the FBA separately.

RESULTS

Behavioral Experiment

We obtained the median for the turning points of each adaptation session from each participant, resulting in 28 median values for the adaptation conditions and 14 additional median values for the preadaptation rating. As Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests turned out to be not significant for each variable (all P > 0.5), we assumed normal distribution and used parametric statistics for further analyses.

The mean of the 14 medians for the “thin” adaptation condition was −1.4 steps (SD = 2.6), indicating that the participants judged a picture on which they were actually depicted thinner to be the most realistic. For the “fat” adaptation condition the mean of the 14 medians was +3.4 steps (SD = 2.4), indicating that the participants judged a picture on which they were actually depicted fatter to be the most realistic. The mean for the preadaptation rating was +2.9 steps (SD = 3.2). The results are also shown in Figure 3B.

A repeated measures ANOVA with the factor condition (thin, fat, and preadaptation) turned out to be significant [n = 14, F(2,26) = 24.179, P < 0.001]. A priori planned one‐sampled t‐tests revealed significant differences for thin adaptation vs. fat adaptation (n = 14, t = −8.274, P < 0.001) and for thin adaptation vs. preadaptation rating (n = 14, t = −5.326, P < 0.001) but not for fat adaptation vs. preadaptation rating (n = 14, t = 0.620, P = 0.546). There were no significant correlations between BMI and the medians of the tested conditions.

Localizer Experiment

In the localizer experiment participants had to respond whenever a certain stimulus (picture or word) appeared twice in a row (one‐back task), which pseudorandomly happened twice in each block. The participants' mean accuracy for this task was 89%.

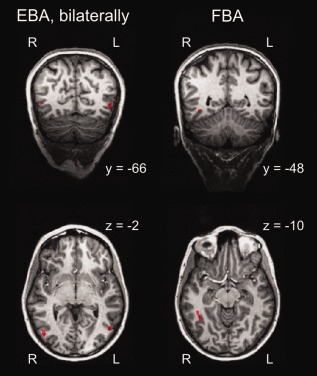

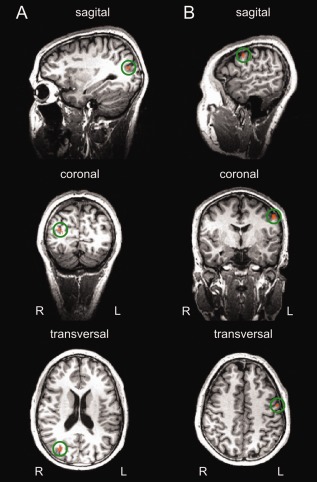

We identified the left and the right EBA in all participants and the FBA in all but two participants, using a contrast of bodies (+1) > faces (−0.5) and scrambled bodies (−0.5). Table 1 shows the respective mean values for the ROIs. Example ROIs of one participant are shown in Figure 4.

Table 1.

ROIs obtained via the localizer experiment

| ROI | Talairach coordinates | Cluster size (voxel) | Anatomical area | Brodmann area | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x | y | z | ||||

| Right EBA | 45 (6) | −68 (7) | −1 (5) | 202 (9) | Inferior temporal gyrus | 37 |

| Left EBA | −44 (5) | −70 (6) | 1 (6) | 200 (10) | Inferior temporal gyrus | 37 |

| FBA | 40 (6) | −48 (10) | −13 (3) | 198 (9) | Fusiform gyrus | 37 |

Shown are the respective mean values for each of the three brain areas for the contrast bodies > faces, scrambled bodies. SDs are given in parentheses.

Figure 4.

Example ROIs of one participant. The left side of the figure depicts the right EBA (Talairach coordinates: x = 47, y = −70, z = 0, 192 voxels) and the left EBA (Talairach coordinates: x = −49, y = −65, z = −1, 204 voxels). On the right side of the figure, the FBA (Talairach coordinates: x = 41, y = −47, z = −9, 215 voxels) is shown.

fMRI Adaptation Experiment, Behavioral Data

In the adaptation experiment, participants were instructed to watch the presented body pictures carefully and indicate the recognition of the original (not manipulated) body picture via button press. In each initial adaptation run, the original body picture was presented 11 times and participants reached a mean accuracy of 78% for all initial adaptation runs (two sessions × three runs). In each test run, the original body picture appeared eight times and participants reached a mean accuracy of 76% for all test runs (two sessions × three runs).

fMRI Adaptation Experiment, Whole Brain Analysis (RFX GLM)

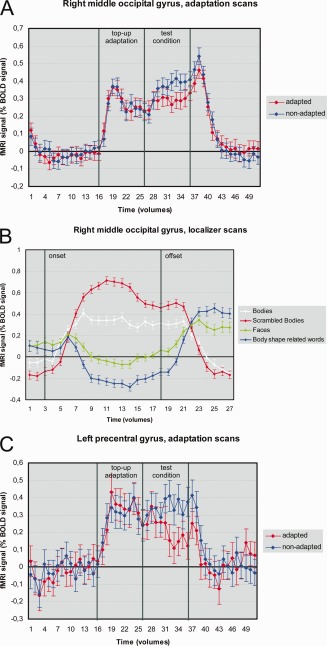

The aim of the whole brain analysis was to identify brain areas specifically adapting to pictures of thin and fat bodies. For this reason, we calculated F‐tests based on a second‐level RFX GLM for a main effect of state (adapted and nonadapted) and an interaction of condition (thin and fat) x state (adapted and nonadapted), statistical threshold at P < 0.001, uncorrected, cluster size threshold at 5 voxels. Two clusters showed a lower BOLD signal for the adapted state (adapted < nonadapted): one cluster in the right middle occipital gyrus [rMOG; x = 31, y = −75, z = 20 (Talairach coordinates), Brodmann area 19, size = 164 voxels] and one cluster in the left precentral gyrus [lPG; x = −53, y = −6, z = 41 (Talairach coordinates), Brodmann area 4, size = 121 voxels]. These clusters are also shown in Figure 5. The BOLD signal change for the main effect of state (adapted and nonadapted) in these clusters is depicted in Figure 6A,C. There were neither significant clusters for the contrary contrast (adapted > nonadapted) nor for the interaction analysis.

Figure 5.

Significant activations for the contrast adapted < nonadapted at threshold P < 0.001, uncorrected (cluster size threshold at 5 voxels). A: Cluster in the rMOG (164 voxels). B: Cluster in the lPG (121 voxels). Clusters are indicated by a green circle.

Figure 6.

BOLD signals for the rMOG and the lPG. A: BOLD signal for the main effect of state (adapted vs. nonadapted) in the rMOG. B: BOLD signal for the localizer conditions in the rMOG. C: BOLD signal for the main effect of state (adapted vs. nonadapted) in the lPG. Vertical bars indicate onsets and offsets of the experimental conditions. Error bars indicate SEs.

We also tested the cluster in the rMOG for selectivity for bodies using a RFX GLM from the functional localizer scans of all 16 subjects. We found a significant effect for the contrast bodies vs. faces (n = 16, t = 7.121, P < 0.001), indicating a higher activation for bodies in comparison to faces. There also was a significant effect for the contrast scrambled bodies vs. bodies (n = 16, t = −4.930, P < 0.001), indicating a higher activation for scrambled bodies in comparison to bodies. The overall activity pattern in the rMOG cluster is: scrambled bodies > bodies > faces (see Fig. 6B). In fact, the presentation of faces resulted in a deactivation in this brain area. A similar analysis for the precentral gyrus was omitted because this cluster is located in the primary motor area (M1) and does not represent a visually perceptive brain area.

fMRI Adaptation Experiment, ROI Analysis

Raw BOLD signal time courses were entered into a repeated measures of ANOVA for each ROI (right EBA, left EBA, FBA) separately. The ANOVAs included two factors: condition (adapted and nonadapted) and state (thin and fat). We did not analyze a main effect of condition (thin and fat) because we did not formulate a hypothesis for this effect.

In the right EBA we neither found a significant main effect for state [n = 16, F(1,15) = 1.095, P = 0.312, Greenhouse–Geisser correction] nor a significant interaction effect of state and condition [n = 16, F(1,15) = 1.620, P = 0.222, Greenhouse–Geisser correction].

In the left EBA there was no main effect for state [n = 16, F(1,15) = 0.197, P = 0.663, Greenhouse–Geisser correction] and no significant interaction [n = 16, F(1,15) = 0.110, P = 0.745, Greenhouse–Geisser correction].

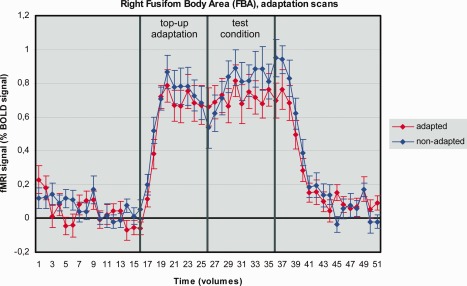

In the FBA there was a significant main effect for state [n = 14, F(1,13) = 12.121, P = 0.004, Greenhouse–Geisser correction], indicating a higher BOLD signal for nonadapted in comparison to adapted, resembling a neural adaptation (Fig. 7). We found no interaction effect [n = 14, F(1,13) = 3.666, P = 0.078, Greenhouse–Geisser correction].

Figure 7.

BOLD signals for the main effect of state (adapted vs. nonadapted) in the right FBA. Vertical bars indicate onsets and offsets of the experimental conditions. Error bars indicate SEs.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we were able to demonstrate that the perception of the own body shape is affected by preceding adaptation to thin and fat pictures of the own body. Furthermore, similar psychophysical adaptation to thin and fat body shapes also leads to neural adaptation in visual brain areas selective for bodies, namely the FBA and the rMOG.

Behavioral Experiment

The behavioral experiment clearly demonstrated that a psychophysical adaptation changes a participant's judgment of her or his own body picture concerning the body shape. After adapting to a picture of one's own thin body, participants perceive subsequently shown pictures of their own bodies as being fatter than actual and vice versa. Thus, due to this perceptual bias in the opposite direction of the adaptation stimulus, a thinner or fatter than actual picture of the own body is perceived as the most realistic picture, dependent on adaptation direction.

However, contrary to the thin adaptation condition, there was no significant difference between the preadaptation rating and the fat adaptation condition. This could argue for a rather unidirectional effect caused only by the thin adaptation condition. An explanation for these differing results could be the strength of adaptation evoked by the used adaptation stimuli. We used a −8 steps picture for thin adaptation, which has a difference of 10.9 steps to the mean of the preadaptation rating of 2.9 steps. For the fat adaptation stimulus of +8 steps the difference to the mean of the preadaptation rating was only 5.1 steps. Because the +8 steps body picture is already closer to the mean of the preadaptation rating, there is a certain possibility that it represents a weaker adaptation stimulus compared to the −8 steps body picture.

An alternative explanation for this asymmetric effect could be a difference in emotional valence between the two adaptation stimuli. As a thin body shape is often idealized in western society, the thin adaptation stimulus in our experiments would represent a more desirable body image than the fat adaptation stimulus. Therefore, the found results could be due to some sort of an imbalance of attention toward the adaptation stimuli.

fMRI Experiment

To summarize the results of the fMRI adaptation experiment, a whole brain group‐level analysis identified two brain areas showing neural adaptation to thin and fat bodies: the rMOG and the lPG. The cluster in the rMOG also exhibited a significant preference for bodies and pictures of scrambled bodies over faces. In a subsequent ROI analysis we found that the EBA (bilaterally) does not adapt to thin and fat bodies. However, in the FBA we found significant neural adaptation to thin and fat bodies. The cluster found in the rMOG represents an extrastriate visual brain area and turned out to be highly selective for bodies and especially for pictures of scrambled bodies. Remarkably, this rMOG cluster (Talairach coordinates: x = 31, y = −75, z = 20) was not co‐localized with the right EBA as localized in this study (mean Talairach coordinates: x = 45, y = −68, z = −1) and in other studies investigating visual body perception [Astafiev et al., 2004; Chan et al., 2004; Downing et al., 2004, 2001; Ewbank et al., 2011; Peelen and Downing, 2005; Urgesi et al., 2004, 2007] and was located more medial and superior than the right EBA. Nonetheless, it shares the same anatomical region (middle occipital gyrus) and Brodmann area (19) as commonly identified right EBA.

At first view, the strong preference for pictures of scrambled bodies in this cluster seems curious. It is therefore noteworthy that the pictures of scrambled bodies—although disassembled and re‐assembled in random patterns—still contained some distinguishable body parts like hands, feet etc. To our knowledge, the classic EBA localizers usually contrast pictures of bodies against pictures of inanimate objects like chairs or tools [e.g., Chan et al., 2004; Downing et al., 2006; Ewbank et al., 2011]. In subsequent ROI analyses, various stimulus sets have been contrasted, including pictures of body parts [e.g., Downing et al., 2004, 2001]. Possibly, the rMOG cluster found in this study represents a brain area with a preference of body parts over whole bodies and a feed‐forward connection to the EBA. In a recent study Orlov et al. 2010 also identified topographically organized body part maps in the occipitotemporal cortex with distinct clusters showing a clear preference for specific body parts.

Taylor et al. 2007 found a gradual activity increase in the EBA for the amount of presented body parts (i.e., a hand produces more activity than a finger, an arm produces more activity than a hand etc.) while the FBA shows a significant preference for whole bodies with no significant selectivity for individual body parts. The authors conclude that the EBA analyzes bodies on the basis of body parts while the FBA analyzes bodies in their entirety. It might be speculated whether the rMOG cluster found in this study functions as a body part detector upstream of the (r)EBA, so that a possible functional path for visual body processing might be rMOG‐to‐(r)EBA‐to‐FBA. To further clarify the possible role of the rMOG in body perception, it would be necessary to design localizer experiments for contrasting bodies against body parts and see if a similar cluster in the rMOG would be revealed. Analyses of effective connectivity like dynamic causal modeling [DCM, see Friston et al., 2003] would be appropriate ways to investigate the functional relationship between rMOG and EBA.

The question remains why this cluster selectively adapts to a thin and fat body shape. In an fMRI adaptation study, Ng et al. 2008 found that several brain areas adapted to certain facial properties (i.e., ethnicity, gender, and identity). Remarkably, these brain areas were not co‐localized with areas activated by traditional face area localizer scans. Furthermore, Hodzic et al. 2009 found that the EBA does not differentiate between familiar and unfamiliar bodies while these distinctions seem to depend on other brain areas like the prefrontal cortex, the inferior parietal cortex and the FBA, indicating a distributed processing of specific bodily properties. It could be speculated whether the rMOG not only responds to body parts but also processes specific properties of these body parts like proportions. Further studies investigating the rMOG's possible role in detecting and distinguishing specific body properties are needed to clarify its contribution to visual body perception and the effects found in the present behavioral experiment.

Given the fact that the cluster in the lPG is located in the primary motor area (M1), it is unlikely that it represents an area sensitive to visual adaptation. Ebisch et al. 2008 found activations in the lPG when participants watched video clips showing intentional or accidental touch of inanimate or animate objects and argued that this activity might reflect polymodal motion processing [see Bremmer et al., 2001]. Nonetheless, because the only visible motion of the stimuli used in this study was the change of tilt orientation which occurred in all conditions (adapted as well as nonadapted) and because there was no information about touch, it is unlikely that polymodal motion processing can explain the activity found in the lPG. For the time being, we have no explanation or valid interpretation for the neural adaptation to thin and fat body pictures in this brain region.

In the ROI analyses of the EBA we found no neural adaptation to body shapes, indicating that the EBA does not show neural adaptation to specific body shapes. In this regard, the results of this study differ from those of previous studies of fMRI adaptation to body stimuli, where the authors were able to detect neural adaptation to identity [Ewbank et al., 2011] or viewpoint [Taylor et al., 2010] of bodies in the EBA. However, these studies utilized other experimental designs as in this study and also investigated different properties of bodies. Furthermore, EBA and FBA were localized due to different contrasts (i.e., bodies > objects) which might have resulted in ROIs consisting of neurons with slightly different processing features, hindering a direct comparison of their results with results of this study.

In contrary to the EBA, in the FBA we found significant neural adaptation, implying that the FBA adapts to specific body shapes and thus might be responsible for the behavioral effects and perceptual biases found in this study and perhaps other studies [Glauert et al., 2009; Winkler and Rhodes, 2005]. Given the fact that the FBA analyzes bodies rather in their entirety [Taylor et al., 2007], a neural adaptation to properties related to whole bodies like body shape seems plausible in this brain region.

Clinical Implications

It could be hypothesized that subjects suffering from brain damage in the fusiform gyrus (e.g., after stroke) exhibit difficulties during tasks demanding detection or discrimination of whole body properties like differing body shapes. A first glance in this direction is a study by Righart and de Gelder 2007 where the authors found that subjects suffering from developmental prosopagnosia with neural impairments in the fusiform gyrus have difficulties not only when recognizing faces but also bodies. Furthermore, as body image disturbances are a core symptom of eating disorders like Anorexia nervosa and Bulimia nervosa [Bruch, 1962; Cash and Deagle, 1997], the FBA might be a candidate brain region to search for a neurophysiological basis of these pathological biases concerning the perception of the own body.

The body shape aftereffect found in this study possibly provides a potential neurocognitive mechanism for the development of clinically relevant body image distortions in psychiatric disorders. It could be speculated that due to different factors like, e.g., low self‐esteem, thoughts about body shape as a means to social acceptance by others etc. [Fairburn et al., 2003], a thin body shape reaches a high emotional importance and visual attention is increasingly captured by specific emotionally relevant stimuli like, e.g., pictures of thin models in daily life [Dobson and Dozois, 2004; Williamson et al., 1999]. Given this permanent exposure specifically to thin bodies, a body shape aftereffect could occur, probably caused by adaptation of body image processing neurons in the FBA and/or rMOG, so that the own body is perceived as fatter than it really is. This perceptual bias could in turn induce even more negative emotional responses and an ongoing capturing of visual attention by emotionally relevant stimuli.

Evidence that at least the right fusiform gyrus might play a crucial role in clinical body image disturbances comes from fMRI studies investigating body shape perception in patients with eating disorders and healthy controls. In a study by Seeger et al. 2002 three AN patients manipulated pictures of their own bodies (target) or of unfamiliar bodies (nontarget) to their individual maximum unacceptability. The authors found greater activation of the right fusiform gyrus for distorted pictures of their own bodies than for pictures of unfamiliar bodies. This activity cluster was in close proximity to the FBA as localized in this study. However, these findings could not be replicated using a larger sample including AN patients as well as healthy control participants [Wagner et al., 2003]. Uher et al. 2005 presented patients suffering from AN or BN and healthy control participants with line drawings of underweight, normal weight and overweight female bodies and found less activation of the fusiform gyrus bilaterally in response to these pictures, regardless of displayed weight/shape of the drawings. Furthermore, the activity in the left fusiform gyrus correlated negatively with the aversion against the presented pictures as indicated by the patients and control participants: the higher the aversion against the pictures, the lesser the activation of the left fusiform gyrus. In a well designed study by Miyake et al. 2010 the authors tested patients with restrictive type of Anorexia nervosa (AN‐R), binge‐purging type of Anorexia nervosa (AN‐BP) and bulimic patients (BN) as well as healthy control participants and presented them with distorted and real pictures of their own bodies and unfamiliar bodies. They found greater activation of the fusiform gyrus—predominantly in the right hemisphere—in response to distorted pictures compared to real pictures in patients with AN‐R, AN‐BP and control participants, but not in patients with BN. Vocks et al. 2010 presented AN patients, BN patients and control participants with unmanipulated pictures of their own bodies and pictures of an unfamiliar woman's body. They found that presentation of the own body leads to less activity of the left fusiform gyrus in AN patients compared to control participants, while presentation of an unfamiliar body leads to stronger activation of the fusiform gyrus bilaterally in AN patients than in healthy controls. Again, similar to the results of Miyake et al. 2010, there were no such findings for bulimic patients. None of the aforementioned studies found activations in close proximity to the coordinates of the rMOG as defined in this study.

These results suggest that with regard to the fusiform gyrus (1) patients suffering from eating disorders generally process body shapes differently than healthy control participants [Uher et al., 2005], (2) ED patients and healthy controls show distinguishable activations when comparing pictures of the own body and pictures of an unfamiliar body [Seeger et al., 2002; Vocks et al., 2010; Wagner et al., 2003], and (3) there seem to be differences between patients suffering from AN and those suffering from BN [Miyake et al., 2010; Vocks et al., 2010]. The question remains as to how patients with eating disorders respond to a prolonged exposure to certain body shapes and whether this prolonged exposure might play a role in the development and perpetuation of clinical body image disturbances (see above). Further studies are clearly needed to address this issue.

There are some limitations to this study. First, in both experiments there were considerably more female participants. As physical appearance has a greater impact on women than on men, there might have been differences concerning the attention toward the stimuli leading to stronger activation in women. Moreover, Aleong and Paus 2010 found that women showed greater BOLD response to pictures of bodies in the right hemisphere compared with the left hemisphere. This is quite interesting as we found adaptation effects in the middle occipital gyrus only in the right hemisphere. However, we did not account for hemispheric differences or gender effects in our analyses. For future studies, care should be taken to investigate a sample balanced in gender.

Second, both experiments examined separate samples, thus preventing investigations of possible relationships between the behavioral and neural adaptation effects on an individual basis. In future studies, behavioral and neural adaptation effects should both be obtained in each individual, comprising one sample for both methods.

CONCLUSION

To conclude, we found significant behavioral as well as neurophysiological effects of adaptation to certain body shapes. The neural adaptation was found in the rMOG and in the FBA. It could be speculated that the rMOG and the FBA are related to the perception of body size and shape. In contrary, the EBA seems not to be included in a network specifically processing body shape. We furthermore suggest that these neural adaptation effects are strongly related to the perceptual biases found in behavioral experiments and maybe also to body image disturbances in terms of eating disorders like Anorexia nervosa and Bulimia nervosa.

REFERENCES

- Aleong R, Paus T (2010): Neural correlates of human body perception. J Cogn Psychol 22:482–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association (2000).Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders DSM‐IV‐TR.Washington DC:American Psychiatric Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Astafiev SV, Stanley CM, Shulman GL, Corbetta M (2004): Extrastriate body area in human occipital cortex responds to the performance of motor actions. Nat Neurosci 7:542–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bremmer F, Schlack A, Shah NJ, Zafiris O, Kubischick M, Hoffmann K, Zilles K, Fink GR. (2001): Polymodel motion processing in posterior parietal and premotor cortex: A human fMRI study strongly implies equivalencies between humans and monkeys. Neuron 29:287–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruch H (1962): Perceptual and conceptual disturbances in Anorexia nervosa. Psychosom Med 24:187–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calder AJ, Beaver JD, Winston JS, Dolan RJ, Jenkins R, Eger E, Henson RN. (2007): Separate coding of different gaze directions in the superior temporal sulcus and inferior parietal lobule. Curr Biol 17:20–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cash TF, Deagle EA (1997): The nature and extent of body‐image disturbances in Anorexia nervosa and Bulimia nervosa: A meta‐analysis. Int J Eat Disord 22:107–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan AW, Peelen MV, Downing PE (2004): The effect of viewpoint on body representation in the extrastriate body area. Neuroreport 15:2407–2410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobson KS, Dozois DJ (2004): Attentional biases in eating disorders: A meta‐analytic review of Stroop performance. Clin Psychol Rev 23:1001–1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downing PE, Bray D, Rogers J, Childs C (2004): Bodies capture attention when nothing is expected. Cognition 93:B27–B38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downing PE, Chan AW‐Y, Peelen MV, Dodds CM, Kanwisher N (2006): Domain specificity in visual cortex. Cereb Cortex 16:1453–1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downing PE, Jiang Y, Shuman M, Kanwisher N (2001): A cortical area for visual processing of the human body. Science 293:2470–2473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebisch SJH, Perrucci MG, Ferretti A, del Gratta C, Romani GL, Gallese V (2008): The sense of touch: Embodied simulation in a visuotactile mirroring mechanism for observed animate and inanimate touch. J Cogn Neurosci 20:1611–1623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewbank MP, Lawson RP, Henson RN, Rowe JB, Passamonti L, Calder AJ (2011): Changes in “top‐down” connectivity underlie repetition suppression in the ventral visual pathway. J Neurosci 31:5635–5642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG, Beglin SJ (1994): The assessment of eating disorders: Interview or self‐report questionnaire? Int J Eat Disord 16:363–370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG, Cooper Z, Shafran R (2003): Cognitive behaviour therapy for eating disorders: A “transdiagnostic” theory and treatment. Behav Res Ther 41:509–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang F, Murray SO, He S (2007): Duration‐dependent fMRI adaptation and distributed viewer‐centered face representation in human visual cortex. Cereb Cortex 17:1402–1411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox CJ, Barton JJS (2007): What is adapted in face adaptation? The neural representations of expression in the human visual system. Brain Res 1127:80–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friston KL, Harrison L, Penny W (2003): Dynamic causal modelling. Neuroimage 19:1273–1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furl N, van Rijsbergen NJ, Treves A, Dolan RJ (2007): Face adaptation aftereffects reveal anterior medial temporal cortex role in high level category representation. Neuroimage 37:300–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgeson M (2004): Visual Aftereffects: Cortical Neurons change their tune. Curr Biol 14:R751–R753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson JJ, Radner M (1937): Adaptation after‐effect and contrast in the perception of tilted lines. J Exp Psychol 20:453–467. [Google Scholar]

- Glauert R, Rhodes G, Byrne S, Fink B, Grammer K (2009): Body dissatisfaction and the effects of perceptual exposure on body norms and ideals. Int J Eat Disord 42:443–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilbert A, Tuschen‐Caffier B (2006):Eating Disorder Examination‐Questionaire:Deutschsprachige Übersetzung. Münster: Verlag für Psychotherapie. [Google Scholar]

- Hilbert A, Tuschen‐Caffier B, Karwautz A, Niederhofer H, Munsch S (2007): Eating Disorder Examination‐Questionaire: Evaluation der deutschsprachigen Übersetzung. Diagnostica 53:144–154. [Google Scholar]

- Hodzic A, Kaas A, Muckli L, Stirn A, Singer W (2009): Distinct cortical networks for the detection and identification of human body. Neuroimage 45:1264–1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohn A (2007): Visual adaptation: Physiology, mechanisms, and functional benefits. J Neurophysiol 97:3155–3164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levinson E, Sekuler R (1976): Adaptation alters perceived direction of motion. Vis Res 16:779–781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little AC, DeBruine LM, Jones BC (2005): Sex‐contingent face after‐effects suggest distinct neural populations code male and female faces. Proc Roy Soc B 272:2283–2287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu T, Larsson J, Carassco M (2007): Feature‐based attention modulates orientation‐selective responses in human visual cortex. Neuron 55:313–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCollough C (1965): The conditioning of color‐perception. Am J Psychol 78:362–378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohr HM, Linder NS, Linden DEJ, Kaiser J, Sireteanu R (2009): Orientation‐specific adaptation to mentally generated lines in human visual cortex. Neuroimage 47:384–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohr HM, Röder C, Zimmermann J, Hummel D, Negele A, Grabhorn R (2011): Body image distortions in bulimia nervosa: Investigating body size overestimation and body size satisfaction by fMRI. Neuroimage 56:1822–1831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohr HM, Zimmermann J, Röder C, Lenz C, Overbeck G, Grabhorn R (2009): Separating two components of body image in aniorexia nervosa using fMRI. Psychol Med 17:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyake Y, Okamoto Y, Onoda K, Kurosaki M, Shirao N, Okamoto Y, Yamawaki S (2010): Brain activation during the perception of distorted body images in eating disorders. Psychiatry Res 181:183–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng M, Boynton GM, Fine I (2008): Face adaptation does not improve performance on search or discrimination tasks. J Vis 8:1–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng M, Ciaramitaro VM, Anstis S, Boynton GM, Fine I (2006): Selectivity for the configural cues that identify the gender, ethnicity, and identity of faces in human cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103:19552–19557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orlov T, Makin TR, Zohary E (2010): Topographic representation of the human body in the occipitotemporal cortex. Neuron 68:586–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peelen MV, Downing PE (2005): Selectivity for the human body in the fusiform gyrus. J Neurophys 93:603–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Righart R, de Gelder B (2007): Impaired face and body perception in developmental prosopagnosia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104:17234–17238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sands R, Maschette W, Armatas C (2004): Measurement of body image satisfaction using computer manipulation of a digital image. J Psychol 138:325–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeger G, Braus DF, Ruf M, Goldberger U, Schmidt MH (2002).Body image distortion reveals amygdala activation in patients with anorexia nervosa—A functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Neurosci Lett 326:25–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzlose RF, Baker CI, Kanwisher N (2005): Separate face and body selectivity on the fusiform gyrus. J Neurosci 25:11055–11059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smeets MAM, Klugkist IG, van Rooden S, Anema HA, Postma A (2009): Mental body distance comparison: A tool for assessing clinical disturbances in visual body image. Acta Psychol 132:157–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smeets MAM, Kosslyn SM (2001): Hemispheric differences in body image in anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord 29:409–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spangler D, Allen M (2011): An fMRI investigation of emotional processing of body shape in Bulimia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord 45:17–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talairach T, Thournoux P. 1988A Coplanar Stereotactic Atlas of the Human Brain.Stuttgart:Thieme Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor JC, Wiggett AJ, Downing PE (2007): Functional MRI analysis of body and body part representations in the extrastriate and fusiform body areas. J Neurophysiol 98:1626–1633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor JC, Wiggett AJ, Downing PE (2010): fMRI‐adaptation studies of viewpoint tuning in the extrastriate and fusiform body areas. J Neurophys 103:1467–1477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson P, Burr D (2009): Visual aftereffects. Curr Biol 19:R11–R14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng CH, Gobell JL, Sperling G (2004): Long‐lasting sensitization to a given colour after visual search. Nature 428:557–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uher R, Murphy T, Friederich HC, Dalgleish T, Brammer MJ, Giampietro V, Phillips ML, Andrew CM, Ng VW, Williams SCR, Campbell IC, Treasure J (2005): Functional neuroanatomy of body shape perception in healthy and eating‐disordered women. Biol Psychiatry 58:990–997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urgesi C, Berlucchi G, Aglioti SM (2004): Magnetic stimulation of extrastriate body area impairs visual processing of nonfacial body parts. Curr Biol 23:2130–2134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urgesi C, Candidi M, Ionta S, Aglioti SM (2007): Representation of body identity and body actions in extrastriate body area and ventral premotor cortex. Nat Neurosci 10:30–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vocks S, Busch M, Grönemeyer D, Schulte D, Herpertz S, Suchan B (2010): Neural correlates of viewing photographs of one's own body and another woman's body in anorexia and bulimia nervosa: An fMRI study. J Psychiatry Neurosci 35:163–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner A, Ruf M, Braus DF, Schmidt MH (2003): Neuronal activity changes and body image distortion in anorexia nervosa. Neuroreport 14:2193–2197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster MA, Kaping D, Mizokami Y, Duhamel P (2004): Adaptation to natural facial categories. Nature 428:557–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster MA, MacLin OH (1999): Figural aftereffects in the perception of faces. Psychon Bull Rev 6:647–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weigelt S, Muckli L, Kohler A (2008): Functional magnetic resonance adaptation in visual neuroscience. Rev Neurosci 19:363–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson DA, Muller SL, Reas DL, Thaw JM (1999): Cognitive bias in eating disorders: Implications for theory and treatment. Behav Modif 23:556–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkler C, Rhodes G (2005): Perceptual adaptation affects attractiveness of female bodies. Brit J Psychol 96:141–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe JM, O'Connell KM (1986): Fatigue and structural change: Two consequences of visual pattern adaptation. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 27:538–543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]