Abstract

Objective:

To assess the availability and price of naloxone as well as pharmacy staff knowledge of the standing order for naloxone in Pennsylvania pharmacies.

Methods:

We conducted a telephone audit study from 12/2016 to 4/2017 in which staff from Pennsylvania pharmacies were surveyed to evaluate naloxone availability, staff understanding of the naloxone standing order, and out-of-pocket cost of naloxone.

Results:

Responses were obtained from 682 of 758 contacted pharmacies (90% response rate). Naloxone was stocked (i.e. available for dispensing) in 306 (45%) pharmacies surveyed. Of the 376 (55%) pharmacies that did not stock naloxone, 118 (31%) stated that they could place an order for naloxone for pickup within one business day. Responses by pharmacy staff to questions about key components of the standing order for naloxone were collected from 581 of the 682 pharmacies who participated in the survey (85%). Of the 581 pharmacy staff members who stated that they either stocked or could order naloxone, 64% correctly answered all questions pertaining to understanding of the naloxone standing order. The respective median out-of-pocket prices stated in the audit varied by formulation and ranged from $50 to $4000. Staff from national pharmacies were significantly more likely than staff from regional/local chain and non-chain pharmacies to correctly answer that a prescription was not required to obtain naloxone (68.5%, 57.7%, and 52.4% respectively, (p=0.0045).

Conclusions:

Multiple barriers to naloxone access exist in pharmacies across a large, diverse state, despite the presence of a standing order to facilitate such access. Limited availability of naloxone in pharmacies, lack of knowledge or understanding by pharmacy staff of the standing order, and variability in out-of-pocket cost for this drug are among these potential barriers. Regulatory or legal incentives for pharmacies or drug manufacturers, education efforts directed toward pharmacy staff members, or other interventions may be needed to increase naloxone availability in pharmacies.

Keywords: Naloxone, harm reduction, opioids, pharmacies

Introduction

Recent years have seen a precipitous rise in morbidity and mortality related to opioid use. Opioids, prescription and illicit, are the main driver of drug overdose deaths in the US. (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2016a). Between 1999 and 2016, opioid overdose deaths increased five-fold, and over 350,000 people died from an overdose involving an illicit or prescription opioid (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2016c). The spectrum of opioids implicated in fatal overdoses has also undergone changes, as have patterns of opioid use and related adverse outcomes. For example, from 2010 to 2015, methadone overdose death rates declined by 9.1%, while rates of death involving other opioids, in particular heroin and synthetic opioids like fentanyl, increased dramatically. In 2015, age-adjusted death rates due to natural or semisynthetic opioids increased by 2.6%, whereas death rates increased by 20.6% for heroin and 72.2% for synthetic opioids with the exception of methadone (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2016b).

One of the most urgent requirements of the comprehensive response to opioid-related harm is the prevention of deaths due to opioid overdoses. To this end, new policies have been developed to increase availability of the medication naloxone, an opioid antagonist that can reverse potentially fatal opioid overdoses when administered emergently. Naloxone is available in several formulations including a generic pre-loaded syringe with an attachable atomizer for nasal insufflation, a branded nasal spray (Narcan®, Adapt Pharm; Radnor, PA), and auto-injectors for intramuscular injection.

Naloxone education has been shown to improve comfort with naloxone use and ability to reverse opioid overdoses among participants from different populations, including people who use heroin and their family members (Pade et al., 2017; Lewis et al., 2016; Wagner et al., 2016; Ashrafioun et al., 2016). The implementation of naloxone education and distribution programs has also been associated with decreased mortality from opioid overdoses (Bird et al., 2016; Walley et al., 2013). Although more research is needed to assess the impact of naloxone education and distribution programs on risk behaviors for opioid overdose, one 2005 pilot study found that 24 people who use injection opioids and received training in cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and naloxone administration witnessed 20 heroin overdoses and administered naloxone in 15 of those overdoses over a six-month follow-up period. All overdose victims survived in these cases (Seal et al., 2005). Despite the demonstrated and potential benefits of naloxone, an older study conducted by Wheeler et al. in 2012 demonstrated that many states with high drug overdose death rates do not have naloxone distribution programs at that time.

As of June 2016, all but five states had created standing orders which allow anyone to obtain naloxone from pharmacies without a personal prescription from a medical provider (The Network for Public Health Law, 2016). However, pharmacies are under no legal obligation to stock or dispense naloxone under these standing orders, and studies investigating whether pharmacy staff are aware of or adhering to important aspects of the standing orders are lacking. Furthermore, previous studies have demonstrated that attitudinal barriers and/or perceptions by pharmacy staff members of opioid use as immoral or undesirable negatively impact access to naloxone (Rudski, 2016; Freeman et al., 2017; Mitchell et al., 2016). It remains unclear to what extent pharmacy staff are aware of the existence of standing orders and understand their implications for naloxone access.

Pennsylvania is a large state with urban and rural centers that is impacted significantly by the opioid overdose crisis (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2017). The objectives of this study were to assess availability of naloxone in Pennsylvania pharmacies, assess pharmacy staff members’ understanding of key components of the standing order for naloxone, and to evaluate out-of-pocket cost for various naloxone formulations.

Methods

Study design

Naloxone availability and price and pharmacy staff knowledge of the standing order for naloxone were assessed using an audit or “secret shopper” study conducted across Pennsylvania. This study was approved by the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board.

Pharmacies were selected from a comprehensive list of pharmacies in Pennsylvania (n = 2285) made available online by a major national insurer (United Healthcare, 2016). We used a skewed random sampling strategy such that in counties with very few pharmacies, a greater proportion of the pharmacies were contacted than in counties with many pharmacies. For example, in rural counties with between one and five pharmacies on the list, 100% of the pharmacies were contacted whereas in highly populous counties with more than 150 pharmacies, between 12% and 13% of pharmacies were contacted. See supplement table S2 for sampling percentages.

We used established methods for the conduct of audit studies (Fix et al., 1993; The Medicaid Access Study Group, 1994; Asplin et al., 2005; Bisgaier et al., 2011). Trained interviewers, posing as customers interested in obtaining naloxone, called 758 (33%) pharmacies on the list over a period from December 2016 to April 2017 seeking information about the availability and price of naloxone. Interviewers used a typed, standardized interview script to initiate the query with a member of the pharmacy staff (the pharmacist, technician, or associate). Interviewers identified and documented the following: 1) professional role of the pharmacy staff member with whom they spoke, 2) whether naloxone was immediately available and, if so, in what formulation; or, if not, whether it could be ordered and within what time frame, 3) if naloxone could be obtained at all from that pharmacy without a prescription, 4) if naloxone could be obtained by a friend or family member of a person at risk for opioid overdose, and 5) the out-of-pocket (without insurance) price for any and all naloxone formulation(s) that were immediately available or could be ordered by the pharmacy. The interview script is included in supplement table 1.

Pharmacy classification

Pharmacies were classified as national chains, regional or local chains, or non-chains. National chain pharmacies were defined as those with presence in greater than 50% of states. Regional or local chain pharmacies were defined as those that either a) have multiple locations within one state, b) have multiple locations in a regional distribution which includes fewer than 50% of states or c) consist of groups of pharmacies with different names owned by the same parent company with locations in fewer than 50% of states. Non-chain pharmacies included single, independently-owned stores. The 2013 Rural-Urban Continuum Codes (RUCCs) from the US Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service ranging in value from 1 (most urban) to 9 (most rural) were used to determine the urbanicity of the counties in which pharmacies were located. County-level drug overdose death rates were determined using the 2015 DEA Drug Overdose Report for Pennsylvania (U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration, 2015).

Statistical analysis

Chi-square statistics were calculated to determine whether differences in naloxone availability and pharmacy staff responses to questions about the standing order were significantly different among different types of pharmacies, in counties with different degrees of urbanicity, and in counties with different opioid overdose death rates. Summary statistics were calculated for the prices of the various naloxone formulations. To detect a 20–25% difference in naloxone availability between pharmacy type, urbanicity, and opioid overdose death rates, using 80% power and alpha set at 0.05, we chose to sample a third of the pharmacies on the list (n = 758).

Results

Pharmacy characteristics and pharmacy staff member roles

Data was collected from 682 (90%) of the 758 pharmacies contacted. Calls in which pharmacy staff refused to answer questions or hung up (n = 13, 2%) or in which the number contacted was no longer in service (n = 63, 8%) were excluded from analysis. Of the pharmacies for which data were collected, 447 (65.5%) were national chains and 479 (70.2%) were located in urban or suburban counties (RUCCs of 1–3). Pharmacy staff members with whom interviewers spoke included 580 (85.0%) pharmacists and 102 (15.0%) technicians or associates. Pharmacy characteristics and pharmacy staff member roles are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1|.

Characteristics of Pennsylvania pharmacies and pharmacy staff contacted during naloxone availability audit study from December, 2016 to April, 2017

| Characteristic | N | (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Survey responders | 682 | |

| Professional role | ||

| Pharmacist | 580 | (85.0%) |

| Associate or technician | 102 | (15.0%) |

| Pharmacy type | ||

| National chain | 447 | (65.5%) |

| Regional or local chain | 94 | (13.8%) |

| Non-chain | 141 | (20.7%) |

| Rural urban continuum codes | ||

| 1 to 3 | 479 | (70.2%) |

| 4 to 6 | 144 | (21.1%) |

| 7 to 9 | 59 | (8.7%) |

| County overdose death rate | ||

| <25th percentile | 108 | (15.8%) |

| 25–75th percentile | 327 | (48.0%) |

| >75th percentile | 247 | (36.2%) |

Naloxone availability

Naloxone availability responses are summarized in Table 2. Naloxone was immediately available for dispensing in 306 (45%) pharmacies, of which 202 (30%) carried only Narcan brand nasal spray, 45 (7%) carried only generic naloxone pre-loaded syringe with or without atomizer, and 47 (7%) carried multiple naloxone formulations. Of the 376 (55%) pharmacies that did not have naloxone immediately available, 207 (30%) reported that they could place an order for naloxone from a supplier or manufacturer, of which 118 (17%) pharmacies stated that the naloxone would be available within one business day. 140 (21%) pharmacies that did not have naloxone available for immediate dispensing stated that naloxone could not be ordered.

Table 2|.

Availability of naloxone in Pennsylvania pharmacies and pharmacy staff responses to key components of standing order for naloxone from December, 2016 to April, 2017

| Naloxone availability | N=682 | (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Pharmacies with naloxone immediately available | 306 | (45%) |

| Intranasal formulation (Narcan brand) | 202 | (30%) |

| Pre-loaded syringe with or without atomizer | 45 | (7%) |

| Auto-injector | 2 | (0%) |

| Unknown or non-specific | 10 | (1%) |

| Multiple | 47 | (7%) |

| Pharmacies without naloxone immediately available | 376 | (55%) |

| Stated that naloxone couldn’t be ordered | 140 | (21%) |

| Stated that naloxone could be ordered for pickup | 207 | (30%) |

| within 1 business day | 118 | (17%) |

| within 2 business days | 30 | (4%) |

| within 3–4 business days | 27 | (4%) |

| within 5 or more business days | 6 | (1%) |

| other or unknown | 26 | (4%) |

| Pharmacy staff member unsure whether naloxone could be ordered | 29 | (4%) |

| Pharmacy staff knowledge of naloxone standing order | N=581 | (%) |

| Standing order knowledge assessment (“Is a prescription required to obtain naloxone?”) | ||

| Correct (Answered “no”) | 373 | (64%) |

| Incorrect (Answered “yes”) | 166 | (29%) |

| Responded “I don’t know.” | 42 | (7%) |

| Third party knowledge assessment (“Can a friend, family member of someone at risk for opioid overdose obtain naloxone?”) | ||

| Correct (Answered “yes”) | 370 | (64%) |

| Incorrect (Answered “no”) | 135 | (23%) |

| Responded “I don’t know.” | 76 | (13%) |

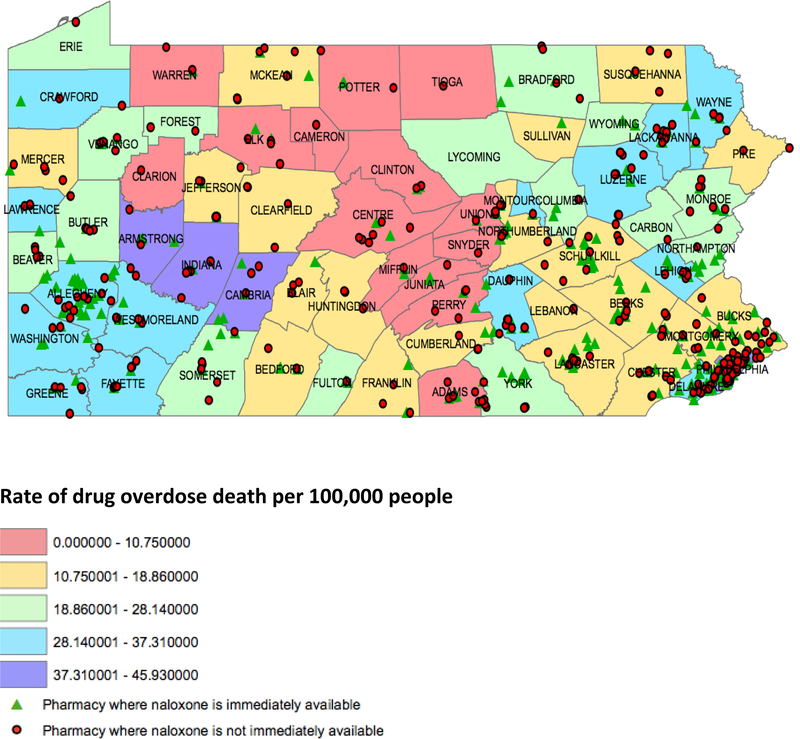

Table 3 shows differences in naloxone availability among different types of pharmacies, counties with different RUCCs, and counties with different opioid overdose death rates. National pharmacies were more likely than regional/local chain and non-chain pharmacies to have naloxone in stock, with 49.9% of national chains stocking naloxone versus 42.6% of regional/local chains and 30.5% of non-chain pharmacies (p=0.0002). There was no statistically significant difference in availability of naloxone in regional/local chain pharmacies versus non-chain pharmacies. The urbanicity and opioid overdose death rate of the counties in which the pharmacies were located did not significantly influence naloxone availability. Figure 1 shows a map of naloxone availability by county opioid overdose death rate.

Table 3|.

Naloxone Availability and Pharmacy Staff Responses to Standing Order Questions by Pharmacy Type, County Urbanicity, and County Opioid Overdose Death Rate in Pennsylvania from December, 2016 to April, 2017

| Naloxone in stock N = 682 |

Correct answer to question 3 (Need prescription to get naloxone?) N = 581 |

Correct answer to question 4 (Can get naloxone for third party?) N = 581 |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Stock naloxone |

%a | p | Total surveyedb |

Correct response |

%c | p | Correct response |

% | p | |

| Pharmacy type | |||||||||||

| National chain | 447 | 223 | 49.9% | 0.0002 | 400 | 274 | 68.5% | 0.0045 | 275 | 68.8% | 0.0008 |

| Regional/local chain | 94 | 40 | 42.6% | 78 | 45 | 57.7% | 42 | 53.9% | |||

| Non-chain | 141 | 43 | 30.5% | 103 | 54 | 52.4% | 53 | 51.5% | |||

| County urbanicity (RUCC) | |||||||||||

| 1 to 3 | 479 | 222 | 46.3% | 0.3924 | 414 | 276 | 66.7% | 0.195 | 270 | 65.2% | 0.53 |

| 4 to 6 | 144 | 63 | 43.8% | 118 | 68 | 57.6% | 70 | 59.3% | |||

| 7 to 9 | 59 | 21 | 35.6% | 49 | 29 | 59.2% | 30 | 61.2% | |||

| County opioid overdose death rate (deaths per 100k population) | |||||||||||

| <17 | 218 | 99 | 45.4% | 0.978 | 192 | 122 | 63.5% | 0.95 | 117 | 60.9% | 0.63 |

| 17–22.9 | 136 | 61 | 44.9% | 112 | 70 | 62.5% | 69 | 61.6% | |||

| 23–33.9 | 124 | 73 | 43.5% | 107 | 74 | 69.2% | 76 | 71.0% | |||

| >34 | 204 | 73 | 45.6% | 170 | 106 | 62.4% | 108 | 63.5% | |||

% in this case was calculated using the number of pharmacies within a particular category that carried naloxone and the total number pharmacies meeting that criteria. For example, 223 of the 447 national chain pharmacies carry naloxone, yielding naloxone stocking rate of 49.9%.

Total surveyed was the same for questions 3 and 4.

% in this case was calculated using the number of pharmacy staff at pharmacies within each category who were administered the naloxone standing order survey questions and the number of those staff that got the answer correct.

Figure 1:

Immediate availability of naloxone in Pennsylvania retail pharmacies (map icons) from December, 2016 to April, 2017 in the context of drug overdose death rate by county (map color).

Pharmacy staff knowledge of the standing order for naloxone

Table 2 reflects how pharmacy staff members responded to questions about two key components of the naloxone standing order. 581 of the 682 pharmacy staff contacted responded to questions regarding the standing order for naloxone (response rate = 85%). Pharmacy staff knowledge of the standing order was not assessed at 101 (15%) pharmacies that both did not stock naloxone and stated that they could not order the drug. 166 (29%) of the pharmacy staff members surveyed incorrectly answered question 3 (i.e. stated that a prescription was required to obtain naloxone), and 135 (23%) incorrectly answered question 4 (i.e. stated that third parties could not obtain naloxone).

Table 3 shows differences in responses to questions about the naloxone standing order among staff at different types of pharmacies, in counties with different RUCCs, and in counties with different opioid overdose death rates. Staff from national pharmacies were significantly more likely (p=0.0045) than staff from regional/local chain and non-chain pharmacies to correctly answer that a prescription was not required to obtain naloxone (68.5%, 57.7%, and 52.4% respectively). Staff from national pharmacies were also more likely (p=0.0008) to respond that third parties could obtain naloxone for another person at risk of opioid overdose (68.8%, 53.9%, and 51.5% respectively). Differences in pharmacy staff knowledge of these two key aspects of the standing order was not significantly different between regional/local chain pharmacies and non-chain pharmacies. The urbanicity and opioid overdose death rates of the of the counties in which the pharmacies were located also did not significantly influence the rate of correct responses by pharmacy staff to questions about the standing order for naloxone.

Pharmacy staff responses to questions about the standing order for naloxone are summarized in Table 2. Comparison of rates of correct responses by pharmacy staff at different types of pharmacies is summarized in Table 3.

Out-of-pocket cost of naloxone formulations

Pharmacy staff were asked to provide the out-of-pocket prices of any and all naloxone formulations that were immediately available or could be ordered by their pharmacies. A total of 502 prices were reported, including 20 auto-injector prices (4%), 362 Narcan prices (72%), and 120 naloxone pre-loaded syringe prices (24%). These prices varied significantly. The median price of Narcan brand nasal spray was $145.00 (IQR $135.00 to $160.00). The median price for naloxone pre-loaded syringe with or without atomizer was $50.00 (IQR $40.00 to $72.00), and the median price for the naloxone auto-injector was $4000.00 ($2,850.00 to $4,550.00).

Discussion

This study has four main findings. First, despite the existence of a standing order for naloxone and a significant public health need, naloxone availability in Pennsylvania pharmacies varies significantly. Second, there are clear deficits in pharmacy staff members’ expressed knowledge of key aspects of Pennsylvania’s standing order for naloxone. Third, national pharmacies are significantly more likely than other types of pharmacies both to carry naloxone and employ staff who express understanding of the naloxone standing order. Finally, out-of-pocket prices for the different formulations of naloxone are markedly variable.

The results of this study demonstrate that, as of May 21, 2017, in Pennsylvania, a large and diverse state with a high rate of opioid overdose fatalities, naloxone is available for immediate dispensing in only 45% of surveyed pharmacies, despite the existence of a standing order for naloxone. A 2016 study by Jones et al found that there was a 1170% increase in naloxone dispensing from US retail pharmacies between the fourth quarter of 2013 and the second quarter of 2015 (Jones et al., 2016). This data, in conjunction with our results, suggests that, although progress has been made in recent years, significant deficits in naloxone availability remain. Our results also show that the opioid overdose rate and the urbanicity of the county in which a pharmacy is located are not associated with naloxone availability. This finding suggests that high opioid overdose death rates at the county level may not be appropriately triggering the policy changes necessary to increase availability of critical resources like naloxone.

Our study also shows that national chains are more likely to carry naloxone than regional/local chains or independent pharmacies in Pennsylvania, and that staff in national chain pharmacies are more likely to correctly answer questions about the standing order for naloxone. This finding reinforces findings from other studies which have demonstrated that pharmacy-based interventions directed at the needs of people who use drugs illicitly are effective at changing staff practices at national or chain pharmacies. For example, multiple studies have found that chain pharmacies are significantly more likely to provide non-prescription syringes to reduce disease transmission among people who inject drugs than independent pharmacies (Cooper et al., 2010; Fuller et al., 2007; Diebert et al., 2006; Farley et al., 1999). We know of no previous published studies that have examined the characteristics of non-chain pharmacies that stock naloxone.

The findings of this study also suggest that there are significant gaps in pharmacy staff members’ knowledge and comprehension of the standing order for naloxone. Only 64% of pharmacy staff correctly answered questions about the two central components of the standing order: that individuals are able to obtain naloxone without a personal prescription and that third parties are able to obtain naloxone on behalf of others. Differences in pharmacy staff knowledge of the naloxone standing order may reflect important attitudinal barriers toward patients with substance use disorder. Our study was not sufficiently powered to assess whether knowledge and comprehension of standing orders was superior among pharmacists as compared to associates or technicians. However, an individual calling for information about naloxone might speak with any member of the pharmacy team, and, in 15% of the calls in this study, associates and technicians fielded questions about naloxone. Thus, we believe that a picture that reflects knowledge of the member of the pharmacy team who ultimately provided information about naloxone to the caller, regardless of their role, is of value. Increased awareness of opioid use disorder and overdose deaths may create a social climate in which pharmacy chains with a national presence have greater incentive to provide training and implement standards for naloxone availability. For pharmacists operating out of smaller pharmacies, the incentive to stock naloxone and work to proactively provide naloxone for those at risk for opioid overdose may require additional community education and public health efforts.

Cost may also present a barrier to naloxone access. Even the most commonly available naloxone formulations can be quite expensive without insurance, and prices range widely overall. Insurance coverage for naloxone varies among different insurance plans, and the way in which a pharmacist processes the order for naloxone can further impact the cost. To bill insurance for naloxone, pharmacists in Pennsylvania are required to fill the prescription for the “patient of record” (i.e. the person at risk for opioid overdose). Thus, while a prescription is not required for third parties to obtain naloxone under the standing order, insurance may not cover the cost of naloxone for these customers. Furthermore, for legal and insurance reasons, pharmacists can only process orders for naloxone on a “one patient per dose” basis. This can present issues for purchasers who may work or live at institutions such as halfway or recovery houses where multiple residents may be at higher risk for opioid overdose.

Given the current atmosphere of uncertainty surrounding the state of health care coverage, questions of cost are particularly important. An analytic model designed by Coffin et al to estimate the cost-effectiveness of distributing naloxone to people who use heroin demonstrated that, even under markedly conservative assumptions, naloxone distribution is both cost-effective and likely to reduce overdose deaths (Coffin et al., 2013). Although naloxone distribution has been shown to be cost-effective even under conservative estimates, increasing prices may decrease naloxone availability for individuals of lower socioeconomic status. Each formulation of naloxone essentially has one supplier, and all manufacturers have increased their prices in recent years, with the newest, easiest-to-use formulations like Narcan and the auto-injector being the most expensive (Gupta et al., 2006).

There are limitations to this study, many inherent to the methods of an audit study. Not disclosing status as academic researchers limits ability to clarify questions and may provide less incentive for pharmacy staff to ensure accuracy of answers to questions. It is possible that some survey answers may not have reflected true knowledge but rather alternative motivators, such as a desire to avoid conducting business with people who have opioid use disorder. Furthermore, we were only able to assess out-of-pocket naloxone prices. Responses to survey questions may also have been different if the survey had been conducted in person, or may have varied among staff within individual pharmacies, and thus it is unknown if responses reflect true availability and cost across all surveyed pharmacies. Despite these limitations, similar telephone-based audit methods have been used before to demonstrate other important aspects of care available and access (Fix et al., 1993; The Medicaid Access Study Group, 1994; Asplin et al., 2005; Bisgaier et al., 2011; Rhodes et al., 2017).

Conclusions

Our study demonstrates that, as of May 21, 2017, 55% of pharmacies in Pennsylvania currently do not stock naloxone and that many pharmacy staff members do not know the basic tenets of the standing order for naloxone. Pennsylvania may be able to improve availability of naloxone by increasing the number of pharmacies that carry naloxone for immediate dispensing and by improving education about the standing order for naloxone among pharmacy staff members. Lessons may be learned from the practices of national pharmacy chains, as these were the only pharmacies that our study showed were more likely than other pharmacies to carry naloxone and whose staff were more likely to correctly respond to questions about the naloxone standing order. Implementation of naloxone distribution and education efforts may be most effective if targeted to areas of the state with the highest rates of opioid overdose, as these areas are currently no more likely than others to have access to naloxone through retail pharmacies than in less vulnerable areas.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Richard Ost RPh, George Down PharmD, and Jeffrey Hom MD, MPH, and representatives from the Pennsylvania Department of Health for their insight, collaboration, counsel. We would also like to thank research assistants Lauren Castellana, Elizabeth Feeney, Ruby Guo, Hareena Kaur, Sharon Kim, Afaf Moustafa, and Kirsten Myers for their hard work conducting pharmacy staff interviews.

Funding

This project was supported in part by the University of Pennsylvania Department of Emergency Medicine Center for Emergency Care Policy Research (CECPR) and by the Center for Health Economics of Treatment Interventions for Substance Use Disorders, HCV, and HIV (CHERISH), a National Institute of Drug Abuse Center of Excellence, NIDA P30DA04050.

References

- Ashrafioun L, Gamble S, Herrmann M, Baciewicz G. Evaluation of knowledge and confidence following opioid overdose prevention training: a comparison of types of training participants and naloxone administration methods. Subst Abus 2016;37(1):76–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asplin BR, Rhodes KV, Levy H, et al. Insurance status and access to urgent ambulatory care follow-up appointments. JAMA 2005;294:1248–1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird SM, McAuley A, Perry S, Hunter C. Effectiveness of Scotland’s national naloxone programme for reducing opioid-related deaths: a before (2006–10) versus after (2011–13) comparison. Addiction 2016;111(5):883–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisgaier J, Rhodes KV. Access to specialty care for children with public versus private insurance. N Engl J Med 2011;364:2324–2333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Drug overdose death data. December 16, 2016. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/data/statedeaths.html. Accessed November 3, 2017.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Increases in drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths – United States, 2010-2015. December 30, 2016. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/65/wr/mm655051e1.htm. Accessed June 4, 2018.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prescription opioid overdose data. June 1, 2016. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/epidemic/index.html. Accessed April 20, 2017.

- Coffin PO, Sullivan SD. Cost-effectiveness of distributing naloxone to heroin users for lay overdose reversal. Ann Intern Med 2013;158(1):1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper EN, Dodson C, Stopka TJ, Riley ED, Garfein RS, Bluthenthal RN. Pharmacy participation in non-prescription syringe sales in Los Angeles and San Francisco counties, 2007. J Urban Health 2010;87(4):543–552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diebert R, Goldbaum G, Parker T, et al. Increased access to unrestricted pharmacy sale of syringes in Seattle-King County, Washington: structural and individual level changes. Am J Public Health 2006;96(8):1347–1353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farley TA, Niccolai LM, Billeter M, Kissinger PJ, Grace M. Attitude and practices of pharmacy managers regarding needle sales to injection drug users. J Am Pharm Assoc 1999;39(1):23–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fix M, Struyk RJ. Clear and convincing evidence: measurement of discrimination in America. Washington, DC: Urban Institute Press, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman PR, Goodin A, Troske S, Strahl A, Fallin A, Green TC. Pharmacists’ role in opioid overdose: Kentucky pharmacists’ willingness to participate in naloxone dispensing. J Am Pharm Assoc 2017;57(2S):S29–S33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller C, Galea S, Caceres W, Blaney S, Sisco S, Vlahov D. Multilevel community-based intervention to increase access to sterile syringes among injection drug users through pharmacy sales in New York City. Am J Public Health 2007;97(1):117–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta R, Shah ND, Ross JS. The rising price of naloxone—risks to efforts to stem overdose deaths. N Engl J Med 2006;375:2213–2215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones CM, Lurie PG, Compton WM. Increase in naloxone prescriptions dispensed in US retail pharmacies since 2013. Am J Public Health 2016;106(4):689–690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis DA, Park JN, Vail L, Sine M, Welsh C, Sherman SG. Evaluation of the overdose education and naloxone distribution program of the Baltimore student harm reduction coalition. Am J Pubic Health 2016;106(7):1243–1246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell KD, Higgins LJ. Combating opioid overdose with public access to naloxone. J Addic Nurs 2016;27(3):160–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pade P, Fehling P, Collins S, Martin L. Opioid overdose prevention in a residential care setting: naloxone education and distribution. Subst Abus 2017;38(1):113–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes KV, Basseyn S, Friedman AB, Kenney GM, Wissoker D, Polsky D. Access to primary care appointments following 2014 insurance expansions. Ann Fam Med 2017;15(2):107–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudski J Public perspectives on expanding naloxone access to reverse opioid overdoses. Subst Use Misuse 2016;51(13):1771–1780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seal KH, Thawley R, Gee L, et al. Naloxone distribution and cardiopulmonary resuscitation training for injection drug users to prevent heroin overdose death; a pilot intervention study. J Urban Health 2005;82(2):303–311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Medicaid Access Study Group. Access of Medicaid recipients to outpatient care. N Engl J Med 1994;330:1426–1430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Network for Public Health Law. Legal interventions to reduce overdose mortality: naloxone access and overdose good samaritan laws. July, 2017. Available at: https://www.networkforphl.org/_asset/qz5pvn/naloxone-_FINAL.pdf. Accessed August 3, 2017.

- U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration. Analysis of drug-related overdose deaths in Pennsylvania, 2015. July, 2016. Available at: https://www.dea.gov/divisions/phi/2016/phi071216_attach.pdf. Accessed April 16, 2017.

- United Healthcare. 2016 pharmacy directory. September 18, 2015. Available at: https://www.uhcretiree.com/content/dam/UCP/Group/2016/pharmacy-directories/2016_GroupRetiree_PDP_PharmacyDirectory-Pennsylvania.pdf. Accessed August 21, 2016.

- Wagner KD, Bovet LJ, Haynes B, Joshua A, Davidson PJ. Training law enforcement to respond to opioid overdose with naloxone: impact on knowledge, attitudes, and interactions with community members. Drug Alcohol Depend 2016;165:22–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walley AY, Xuan Z, Hackman HH, Quinn E, Doe-Simkins M, Sorensen-Alawad A, Ruiz S, Ozonoff A. Opioid overdose rates and implementation of overdose education and nasal naloxone distribution in Massachusetts: interrupted time series analysis. BMJ 2013;346:f174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler E, Davidson PJ, Jones TS, Irwin WK. Community-based opioid overdose prevention programs providing naloxone—United States, 2010. CDC MMWR 2012;61(6):101–105. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wide-ranging online data for epidemiologic research (WONDER) [database online]. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2016. Updated November 2, 2017. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.