Abstract

Although memory dysfunction is not a prominent feature of the behavioral variant of frontotemporal dementia (bv‐FTD), there is evidence of specific deficits of episodic memory in these patients. They also have problems monitoring their memory performance. The objective of the present study was to explore the ability to consciously retrieve own encoding of the context of events (autonoetic consciousness) and the ability to monitor memory performance using feeling‐of‐knowing (FOK) in bv‐FTD. Analyses of the patients' cerebral metabolism (FDG‐PET) allowed an examination of whether impaired episodic memory in bv‐FTD is associated with the frontal dysfunction characteristic of the pathology or a dysfunction of memory‐specific regions pertaining to Papez's circuit. Data were obtained from eight bv‐FTD patients and 26 healthy controls. Autonoetic consciousness was evaluated by Remember responses during the recognition memory phase of the FOK experiment. As a group, bv‐FTD patients demonstrated a decline in autonoetic consciousness and FOK accuracy at the chance level. While memory monitoring was impaired in most (seven) patients, four bv‐FTD participants had individual impairment of autonoetic consciousness. They specifically showed reduced metabolism in the anterior medial prefrontal cortex, the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (near the superior frontal sulcus), parietal regions, and the posterior cingulate cortex. These findings were tentatively interpreted by considering the role of the metabolically impaired brain regions in self‐referential processes, suggesting that the bv‐FTD patients' problem consciously retrieving episodic memories may stem at least partly from deficient access to and maintenance/use of information about the self. Frontal and posterior cingulate metabolic impairment in the behavioral variant of frontotemporal dementia with impaired autonoetic consciousness Hum Brain Mapp, 2011. © 2011 Wiley‐Liss, Inc.

Keywords: frontotemporal dementia, episodic memory, autonoetic consciousness, monitoring, FOK, FDG‐PET, cingulate cortex

INTRODUCTION

Frontotemporal dementia (FTD) is a heterogeneous spectrum of diseases. The most frequent presentations are the behavioral variant (bv‐FTD), progressive aphasia, semantic dementia and corticobasal degeneration [Kertesz et al., 2007; McKhann et al., 2001]. At the cognitive level, the bv‐FTD profile mainly consists of a disruption of attention and executive functions, as well as decision‐making difficulties [Hodges and Miller, 2001]. Although this does not constitute a prominent deficit, there is also evidence of an impairment of episodic memory function in bv‐FTD patients [Mendez and Cummings, 2003].

Episodic memory is defined as memory for events that have been personally experienced in a particular spatiotemporal context, the retrieval of which is accompanied by the subjective feeling of travelling in time to relive the events. This particular feeling, which implies the awareness of the self as a continuous entity across time, is called autonoetic consciousness [Tulving, 2002]. Autonoetic consciousness is frequently assessed by means of the Remember/Know procedure [Gardiner, 1988], in which participants report whether memory retrieval is accompanied by the recollection of the encoding context (Remember judgments, reflecting autonoetic consciousness) or by a mere feeling of knowing that the information is old (Know judgments, based on noetic consciousness). Evidence of a decreased ability to re‐experience past events in bv‐FTD comes from studies showing a lack of autonoetic consciousness in the retrieval of autobiographical memories [Matuszweski et al., 2006; Piolino et al., 2007]. To date, only one study has explored the consciousness states associated with memory for recently learned items in a mixed group of FTD patients [Söderlund et al., 2008]. In this study, FTD patients and healthy controls were presented with humorous definitions and corresponding words in the auditory or visual modality. At test, the words had to be retrieved in a cued recall test (with the definition as the cue) and in a recognition memory test. For recognized items, participants further indicated whether the item had previously been heard or read (source memory) and what their subjective experience was when retrieving the item (Remember/Know judgments). The results showed that, in addition to cued recall, recognition and source memory deficits, FTD patients gave fewer Remember responses than controls. Moreover, in order to relate the decline in Remember responses to structural changes in the patients' brains, Söderlund et al. [ 2008] searched for correlations between Remember scores and grey matter volume in regions of interest. They found that the grey matter volume of the left medial temporal lobe was positively correlated with the number of Remember judgments in the patients, whereas the grey matter volume of the left inferior parietal cortex was positively correlated with familiarity judgments. Thus, this study demonstrated that FTD patients find it difficult to consciously re‐experience an earlier encounter with a stimulus, and that this impairment is related to atrophy in the medial temporal lobe.

Autonoetic consciousness is a complex phenomenon involving the retrieval of events with self‐experienced contextual details [Tulving, 2002]. Metamemory refers to a domain of high‐order processing involving self‐knowledge, self‐awareness, self‐monitoring, and control of one's own memory functioning [Dunlosky and Bjork, 2008]. Given the lack of insight observed early in the course of bv‐FTD [Neary et al., 1998; Salmon et al., 2008], the investigation of the different facets of metamemory in bv‐FTD should clarify the mechanisms responsible for this prominent symptom. In bv‐FTD, the ability to monitor one's own performance in a memory task (self‐monitoring) has been measured by the accuracy of judgments about performance when they are made after exposure to the material (for instance, to predict, after studying a list of words, how many words will be subsequently remembered, or to assess how well a particular task was performed after its completion). Previous findings suggested that bv‐FTD patients have difficulty monitoring their memory performance, in post‐study predictions of recall performance [Souchay et al., 2003] and in post‐task assessments [Banks and Weintraub, 2008; Eslinger et al., 2005]. More recently, Rosen et al. [ 2010] found that a heterogeneous group, including patients with probable Alzheimer's disease (AD), patients with Mild Cognitive Impairment and FTD patients, overestimated their cognitive abilities in post‐task assessments, and that cognitive self‐appraisal was correlated with grey matter volume of the ventromedial prefrontal cortex, independently of the diagnosis. However, self‐monitoring measures based on global predictions or post‐task performance assessments has been criticized because normal participants often fail to predict their performance accurately, due to lack of experience with the experimental tasks and a tendency to anchor predictions near the midpoint of the possible range of performance [Connor et al., 1997]. To avoid this confounding factor, methods requesting item‐by‐item predictions, such as the feeling‐of‐knowing (FOK) paradigm, have been emphasized in cognitive psychology [Dunlosky and Bjork, 2008]. In the episodic FOK procedure, participants study cue‐target word pairs and then try to recall the target associated with each cue. Moreover, they have to predict whether they will recognize it later. Using this paradigm, participants' self‐monitoring is measured by their ability to make accurate FOK predictions for the non‐recalled items. Indeed, when making predictions, it is thought that participants monitor the contents of their memory, assessing how familiar the cue is or whether partial information remains accessible in order to determine whether they feel they can recognize the target. To our knowledge, the FOK paradigm has never been used in bv‐FTD.

The purpose of the present study was to explore autonoetic consciousness and self‐monitoring in patients with the behavioral variant of FTD and to examine the neural correlates of conscious recollection by comparing the brain metabolism of bv‐FTD patients with that of healthy controls using 18Ffluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) and PET. So bv‐FTD patients and healthy participants performed an episodic FOK task, which assessed recall, prediction of recognition and recognition performance for word pairs. The states of consciousness accompanying recognition were explored via the Remember/Know procedure. Self‐monitoring abilities were assessed by the accuracy of FOK judgments. Based on previous work [Banks and Weintraub, 2008; Eslinger et al., 2005; Söderlund et al., 2008; Souchay et al., 2003], bv‐FTD patients were expected to show a decrease in Remember responses and inaccurate item‐by‐item predictions. Moreover, if the impairment of episodic memory in bv‐FTD reflects a dysfunction of strategic encoding and retrieval processes [Mendez and Cummings, 2003], bv‐FTD with poor autonoetic consciousness may present with reduced metabolic activity in the frontoparietal regions supporting executive functions [Collette and Van der Linden, 2002]. Alternatively, the decrease in Remember responses may be related to altered memory representations as a result of the dysfunction of memory‐specific regions such as the medial temporal lobes, as Söderlund et al. [ 2008] found.

METHODS

Participants

The data reported here were part of a multidisciplinary evaluation of self‐awareness (including questionnaires about behavioral and cognitive functioning, and an FOK task, see below) and cognitive functioning (including measures of episodic memory and executive function) in neurodegenerative diseases. The whole evaluation was performed in two sessions of about 2 hours each, with an FDG‐PET scan after the first session and a structural MRI scan, when applicable, after the second one. The FOK task described in the present study was administered at the beginning of the first session. The first session also included executive tasks and the Memory Awareness Rating Scale [Clare et al., 2002].

A group of 15 patients (4 women and 11 men) consecutively referred by neurologists and presenting with a clinical diagnosis of FTD [McKhann et al., 2001] underwent this evaluation. After 2 years of follow‐up, hospital records confirmed progressive deterioration in all patients and clarified the diagnosis: 2 patients were eventually found to have AD, 11 patients met the criteria for bv‐FTD, 1 showed a dysexecutive syndrome together with aphasic features, and 1 had clinical characteristics compatible with corticobasal degeneration. The patients with AD, language disorders and corticobasal degeneration were excluded from the study, so as to retain only patients with bv‐FTD [McKhann et al., 2001; Neary et al., 1998]. Upon inclusion, behavioral disturbances were confirmed by the presence of at least one symptom on the Neuropsychiatric Inventory [NPI; Cummings et al., 1994] and by significant changes in behavior reported by an informant on a questionnaire requesting behavior prediction in social and emotional situations [Ruby et al., 2007] (see Table I). On average, the disease duration of the bv‐FTD patients was 2.7 years ± 1.3. The study also included 26 healthy control participants (17 women and 9 men). During an interview with each participant and a close relative, we ensured that control participants had no psychiatric or neurological problems, were free of medication that could affect cognitive functioning, and were in good health. According to the Declaration of Helsinki BMJ 1991;302:1194, all participants and their relatives gave their written consent to participate in the study, which was approved by the ethics committee of the University Hospital of Liège.

Table I.

Participants' demographic and clinical characteristics and scores on neuropsychological tests (mean and standard deviation)

| Bv‐FTD patients (n = 11) | Controls | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 64.6 (12.0)* | 72.8 (7.2) |

| Years of education | 11.6 (3.5)a | 12.8 (2.8) |

| Mill Hill vocabulary test (max. 33) | 21.6 (5.5) | 24.8 (7.2) |

| Mattis DRS | 125.0 (13.1)** | 138.1 (5.9) |

| Neuropsychiatric inventory | 17.4 (10.5) | Not done |

| Behavioral changesb | 46.9% (18.9)** | 20.3% (17.7) |

| Reading span (no. correct responses) | 11.8 (8.7)* | 16.4 (6.0) |

| Hayling test (errors) | 14.7 (8.1)* | 8.6 (4.9) |

| Cognitive estimation (deviation score) | 9.45 (3.8)*** | 7.2 (3.2) |

| Memory Awareness Rating Scalec | 7.5 (12.2)**** | 0.2 (4.9) |

Significant difference between the four bv‐FTD patients with poor Remember scores (8.4 years of education on average) and the four bv‐FTD patients with high Remember scores (13.2 years of education on average, P < 0.05).

Percent of divergence between the informant's assessment of the patient's past (10 years ago) and present behavior in social and emotional situations [see Ruby et al., 2007, for details on the questionnaire]. Divergence scores of the control group were comparable to those of the healthy elderly participants in Ruby et al. [ 2007].

Discrepancy score between self‐rating and relative's rating of memory abilities (a high positive score indicates overestimation of memory functioning).

P < 0.01;

**P < 0.001;

P < 0.08;

P < 0.05.

The demographic and clinical characteristics of the bv‐FTD and control groups are presented in Table I. The groups were matched in terms of education and vocabulary performance [Mill Hill test; Deltour, 1993]. However, the patients were younger than the controls. On the Mattis Dementia Rating Scale [DRS; Mattis, 1973], the bv‐FTD patients performed worse than the controls.

Neuropsychological tests assessing aspects of executive functioning included a dual task in working memory with the Reading span [Daneman and Carpenter, 1980; Desmette et al., 1995], inhibition using the Hayling test [Andrés and Van der Linden, 2000; Burgess and Shallice, 1996] and cognitive estimation [Levinoff et al., 2006]. The bv‐FTD patients were impaired on the Hayling task and showed marginally poorer performance on the Reading span and cognitive estimation tasks. When comparing the participant's and the relative's answers on the Memory Awareness Rating Scale, the discrepancy scores revealed unawareness of memory impairment in bv‐FTD patients (Table I).

Three patients had incomplete data for the experimental task that is the focus of the current investigation. Thus, the analyses were performed on the remaining eight bv‐FTD patients. The excluded patients did not differ from those who were included in terms of age, education, dementia severity, behavioral disturbances, vocabulary, executive performance or anosognosia for cognitive impairment.

Materials and Procedure

The episodic FOK task was adapted from Souchay et al. [ 2007]. The stimuli consisted of 40 target French words, each paired with a weakly associated word, which served later as a cue. The stimuli were randomly divided into two sets of 20 items, in order to create two versions of the task. All participants were tested individually and were randomly assigned one version of the task. Stimuli were presented in the centre of a computer screen.

The FOK procedure consisted of a study phase, a cued‐recall/FOK judgment phase and a recognition phase. After a practice illustrating the whole procedure with three cue‐target pairs, participants were told that the main task would involve 20 pairs.

In the study phase, participants were presented with 20 cue‐target pairs. The cue word was printed in lowercase letters next to the target word, which was printed in capital letters. Participants were instructed to try and remember the pairs because their memory for the second (target) word would later be tested by using the first word as a cue. The pairs were shown in random order and each remained on the screen for 5 seconds.

After a short delay filled with instructions, the cued recall phase began. The cues were presented in random order. The participants were asked to recall the target word that was associated with each cue during the study phase. Whatever their response (correct target word, incorrect answer or omission), they had next to give a feeling‐of‐knowing judgment. More specifically, they were asked whether they thought they would be able to recognize the target in a later forced‐choice recognition test. The feeling‐of‐knowing judgment was made with a “yes” or “no” response.

Finally, a five‐alternative forced‐choice recognition phase was administered. Each of the 20 target words was presented with four semantically related distracter words. The participants had to indicate which word they had seen in the study phase. Moreover, for each response, they were asked to give a Remember/Know/Guess judgment. Participants were instructed that a Remember response corresponded to the recollection of specific information relative to the stimulus encoded at the study phase; that a Know response referred to recognition on the basis of familiarity without recollection; and that a Guess response could be used when they were unsure about their response. In order to check the validity of Remember, Know and Guess judgments, participants were asked to justify each answer and were reminded of the distinction between the types of judgments when necessary.

FDG‐PET Image Acquisition and Analysis

PET images were acquired on an ECAT EXACT HR+ Siemens scanner during quiet wakefulness with eyes closed and ears unplugged after intravenous injection of 2‐[18F]fluoro‐2‐deoxy‐d‐glucose (130–265 MBq) [Lemaire et al., 2002]. Images of tracer distribution in the brain were used for analysis: scan start time was 30 min after tracer injection and scan duration was 20 min. Images were reconstructed using filtered backprojection including correction for measured attenuation and scatter using standard software. FDG‐PET image analyses were performed using SPM8 (Wellcome Department of Cognitive Neurology, London, UK). The PET data were subjected to an affine and nonlinear spatial normalisation onto the SPM8 PET brain template. Images were then smoothed with a 12‐mm full width at half‐maximum filter. A correction of partial volume effect could not be applied because two bv‐FTD patients were unable to undergo a structural MRI scan due to metallic implants. As a first step, PET images of all patients were compared with those of controls using proportional scaling by cerebral global mean values to control for individual variation in global FDG uptake. Age, number of years of education and gender were introduced as confounding variables. Brain regions with preserved metabolism in bv‐FTD patients were identified by a contrast showing areas with relatively increased activity in bv‐FTD patients compared to controls [Yakushev et al., 2008]. In this contrast, the region with the highest t‐value was the sensorimotor cortical region (P < 0.05 FWE corrected for multiple comparisons at the voxel level). Raw individual FDG uptake values in this cluster were extracted using MarsBar [Brett et al., 2002]. Then, SPM analyses were performed on images that were proportionally scaled to the sensorimotor activity. These analyses are described in the following section.

Statistical Analyses

Behavioral analyses

Behavioral data from the experimental task were analyzed using parametric statistical procedures because the variables were normally distributed. Given that the groups differed in terms of age, the scores were entered into analyses of variance with age introduced as a covariable. FOK accuracy, that is, the relationship between FOK judgments and recognition performance, was measured by the Gamma index [G = (ad − bc)/(ad + bc)] and the Hamann index [H = ((a + d) − (b + c))/((a + d) + (b + c))] calculated for omissions, where “a” is the proportion of correct yes predictions, “d” is the proportion of correct no predictions, “b” is the proportion of incorrect yes predictions, and “c” is the proportion of incorrect no predictions [Schraw, 1995]. Moreover, we corrected the proportions of “a,” “b,” “c,” and “d” by adding 0.5 to each and then dividing them by N + 1 (N is the number of yes or no judgments) so that the Gamma index is not undetermined if one of the four possible outcomes is not observed in a subject [Snodgrass and Corwin, 1988].

To examine the relationship between the ability to make accurate FOK judgments and conscious recollection of the encoding context, a correlation was computed between FOK indices and Remember responses. In the control group, Pearson correlations were calculated, whereas in the bv‐FTD group, we used a nonparametric Spearman correlation, which is more appropriate for small samples. In the bv‐FTD group, we also computed Spearman correlations between Remember responses and FOK indices on the one hand and anosognosia for memory (as measured by the patient‐relative discrepancy score on the Memory Awareness Rating Scale) on the other hand.

Cerebral metabolic analyses

To explore the brain changes specifically associated with impaired autonoetic consciousness in bv‐FTD, we created a factorial design including the PET images of the control group, a subgroup of four bv‐FTD patients with poor Remember scores (as measured by low Remember scores compared to controls, i.e., 1.5 standard deviations from the controls' mean), and a subgroup of four bv‐FTD patients with high Remember scores (within the normal range). A similar analysis could not be done for self‐monitoring ability, as the feeling‐of‐knowing measure was deficient in all patients except one. Age was introduced as a covariable, as were the number of years of education (because the two bv‐FTD subgroups differed in terms of education) and gender (because the women/men ratio differed between the control and patient groups). Since the two subgroups did not differ significantly in terms of disease duration, this variable was not introduced as a confounding covariable. Three types of analyses were planned. First, the brain metabolism of all bv‐FTD patients was compared to that in healthy controls in order to identify a set of hypometabolic regions associated with bv‐FTD in general. Second, brain changes specifically associated to decreased autonoetic consciousness in bv‐FTD were explored via the “patients with poor Remember scores < controls” contrast, masked (exclusive mask at P < 0.05 uncorrected) by the “patients with high Remember scores < controls” contrast. Third, the specificity of the results was further checked by looking at the reverse contrast: “Patients with high Remember scores < controls,” masked exclusively by “patients with poor Remember scores < controls.” For all comparisons, the probability threshold was set at P < 0.05 FWE corrected for multiple comparisons at the voxel level, with a threshold for minimum spatial extent of 20 contiguous voxels.

RESULTS

Memory and metamemory performance

Memory performance

Cued recall phase

For the bv‐FTD and control groups, the proportions of words correctly recalled on the basis of the cue are presented in Table II, together with the proportions of missing responses (omissions) and incorrect responses (intrusions). Bv‐FTD patients recalled fewer words than the controls, F (1,31) = 6.03, P < 0.05, and committed more intrusion errors, F (1,31) = 7.52, P < 0.05. In contrast, they said they could not recall the target (omissions) as often as healthy controls did, F (1,31) = 0.89, P > 0.35.

Table II.

Memory and metamemory performance expressed in mean proportions (and standard deviations) as a function of group

| bv‐FTD | Controls | |

|---|---|---|

| Cued recall phase | ||

| Correct cued recall | 0.18 (0.26)* | 0.33 (0.22) |

| Omissions | 0.59 (0.26) | 0.56 (0.21) |

| Intrusions | 0.23 (0.17)* | 0.11 (0.10) |

| Recognition phase | ||

| Correct recognition | 0.65 (0.17)* | 0.77 (0.20) |

| FOK | ||

| Gamma index | 0.09 (0.39) | 0.17 (0.57) |

| Hamann index | 0.14 (0.39) | 0.25 (0.48) |

Significant difference at P < 0.05.

Recognition phase

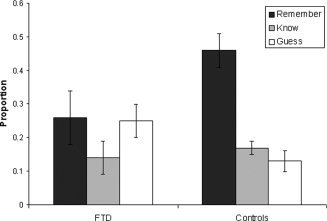

Table II shows the proportions of correct recognitions of bv‐FTD patients and control participants. Bv‐FTD patients correctly recognized fewer words than the controls, F (1,31) = 4.59, P < 0.05. The judgments associated with correct recognition in each group are presented in Figure 1. The analyses of Remember/Know/Guess responses indicated that the bv‐FTD patients produced fewer Remember responses, F (1,31) = 5.79, P < 0.05. No group difference appeared for Know responses (P > 0.61). Patients also tended to give more Guess responses than the controls, F (1,31) = 3.74, P < 0.063. With regard to false recognitions, there was no significant group difference in the proportions of Remember and Know responses (Ps > 0.38), and only a trend for patients to make more Guess judgments for false recognitions than controls (P < 0.086). Most false recognitions were associated with a Guess (bv‐FTD: 0.26 ± 0.19, controls: 0.17 ± 0.18) or a Know judgment (bv‐FTD: .06 ± 0.08, controls: 0.04 ± 0.05). There were very few false Remember responses (bv‐FTD: 0.02 ± 0.03, controls: 0.02 ± 0.04).

Figure 1.

Proportions of Remember, Know, and Guess responses given to old words in the bv‐FTD patients and the control group.

Feeling‐of‐knowing accuracy

The Gamma and Hamann indices obtained by each group are presented in Table II. No group difference was found on any index (Gamma: F (1,31) = 0.04, P > 0.82; Hamann: F (1,31) = 0.37, P > 0.54). However, in the bv‐FTD group, neither index was significantly different from zero (Gamma, t (7) = 0.71, P > 0.49; Hamann, t (7) = 1.03, P > 0.33), which corresponds to a lack of association between the predictions and the recognition performance. In contrast, in the control group, although the Gamma index did not differ from zero, the Hamann index was significantly greater than zero, t (25) = 2.61, P < 0.05, suggesting that control participants were able to accurately predict their future recognition performance.

Correlations

The correlation between the Hamann index and Remember responses was positive in the control group (r = 0.46, P < 0.05), but not significant in the bv‐FTD group.

In the bv‐FTD group, FOK indices indicating prediction of recognition (but not Remember responses) were negatively correlated with the level of anosognosia for daily memory impairment obtained with the Memory Awareness Rating Scale (r = −0.72, P < 0.05).

PET Image Analyses

Comparison between the bv‐FTD group and the control group

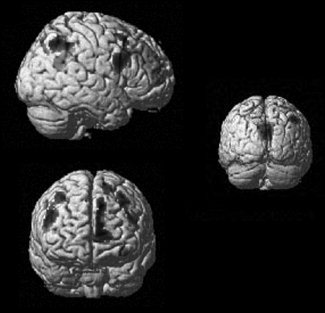

Bv‐FTD patients showed hypometabolism in bilateral frontal regions as well as in the anterior cingulate/medial frontal cortex, the right inferior parietal gyrus and the posterior cingulate cortex (see Fig. 2, peak coordinates are reported in Table III). Given that impaired metabolic activity in the posterior cingulate cortex is unusual in bv‐FTD, we checked whether this finding was due to an outlier who dragged the value of this region down. In fact, most patients had reduced activity in this region.

Figure 2.

Results of the SPM analysis comparing the brain glucose metabolism of the bv‐FTD group and the control group rendered on a single subject brain (top left: sagittal view, bottom left: frontal view; right: posterior coronal view).

Table III.

Brain regions with decreased metabolic activity in the bv‐FTD group compared with the control group

| Regions | BA | MNI coordinates | z‐Score | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x | y | z | |||

| Anterior cingulate | 32 | −8 | 30 | 30 | 5.25 |

| Left middle frontal | 8 | −38 | 20 | 46 | 5.33 |

| Left inferior frontal | 11 | −36 | 36 | −12 | 4.32 |

| Left superior frontal | 6 | −16 | 18 | 62 | 5.02 |

| Right middle frontal | 9 | 48 | 6 | 28 | 5.10 |

| Right superior frontal | 6 | 20 | 14 | 62 | 5.23 |

| Right inferior parietal | 40 | 48 | −58 | 46 | 4.65 |

| Posterior cingulate | 31 | −8 | −52 | 30 | 5.13 |

P < 0.05 FWE corrected for multiple comparisons.

BA, Brodmann area.

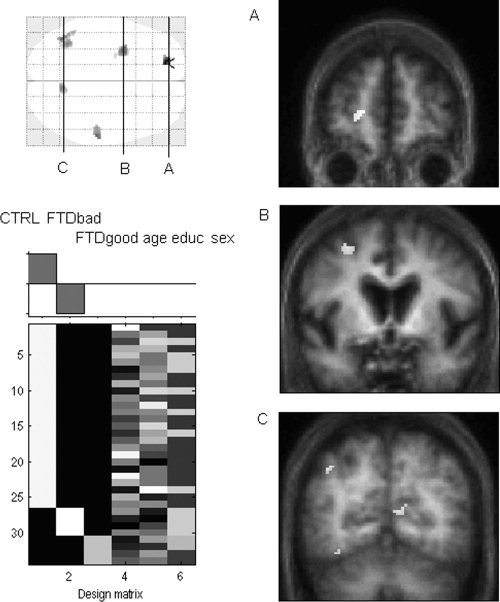

Brain hypometabolism associated with decreased autonoetic consciousness

Figure 3 presents the results of the SPM analysis that sought regions with impaired activity specifically in the four bv‐FTD patients with deficient conscious retrieval of the encoding context, with a mask excluding regions showing reduced activity in the four bv‐FTD patients with high Remember scores. The results indicated that bv‐FTD patients with low Remember responses were characterized by brain hypometabolism in the left anterior medial frontal cortex (BA10), the left middle frontal cortex near the superior frontal sulcus (BA6), the right postcentral gyrus (BA2), the left inferior parietal cortex (BA40), and the posterior cingulate cortex (BA23). It should be noted that the analysis of regions with reduced activity in the bv‐FTD patients with higher Remember scores did not yield any significant result at the selected statistical threshold, suggesting that bv‐FTD patients with preserved ability to retrieve episodic information did not show the same brain changes as patients with impaired autonoetic consciousness.

Figure 3.

Results of the SPM analysis examining brain changes associated with decreased autonoetic consciousness in bv‐FTD (P < 0.05 FWE corrected): “patients with poor Remember scores < controls,” masked exclusively by “patients with high Remember scores < controls” on the SPM glass brain. Regions with reduced activity in patients with decreased autonoetic consciousness are shown on coronal sections of the average of six patients' MRI images (A: left anterior frontal region; B: left lateral frontal region; C: posterior cingulate cortex).

DISCUSSION

In this study, the ability to consciously recollect the prior occurrence of certain information was investigated in a sample of bv‐FTD patients using the Remember/Know procedure. Recent findings had indicated that Remember responses decrease in FTD [Söderlund et al., 2008]. Here we looked for the functional cerebral changes associated with the reduction in Remember responses in bv‐FTD, via FDG‐PET. In this way, we could examine whether the deficit of episodic memory in bv‐FTD is related to reduced metabolic activity in the frontoparietal regions supporting executive functions [Collette and Van der Linden, 2002] or to a dysfunction of memory‐specific regions pertaining to Papez's circuit [Söderlund et al., 2008]. Moreover, the feeling‐of‐knowing procedure allowed us to measure the participants' ability to monitor their own memory functioning.

At the behavioral level, the results showed that bv‐FTD patients had reduced cued recall performance, as previously reported [Mendez and Cummings, 2003; Söderlund et al., 2008]. Moreover, their recognition performance was characterized by a specific reduction of Remember judgments. In contrast, familiarity‐based recognition (Know responses) appeared to be preserved in the patients. This confirms that autonoetic consciousness is altered in bv‐FTD and that the patients' memory deficit consists mainly in altered recollection of the specific context in which an event was initially experienced. Moreover, bv‐FTD patients had difficulty predicting their future recognition performance, as shown by the lack of association between their FOK judgments and their actual performance. This inability to monitor their memory performance may represent another aspect of the lack of insight characteristic of the pathology, as suggested by the fact that poorer prediction accuracy correlated with a greater level of anosognosia for memory functioning in everyday life. In order to make episodic FOK judgments, participants are thought to determine the likelihood that the target word is still in memory on the basis of partial information retrieved during the recall search process [Koriat, 1993]. More specifically, Souchay et al. [ 2007] proposed that autonoetic consciousness constitutes the partial information that generates an episodic feeling‐of‐knowing. Indeed, the subjective feeling of remembering part of an event, with access to some contextual details, supports the metacognitive judgment that this event will be retrievable later. This is probably what happened in the control participants, as shown by the positive correlation between FOK accuracy and Remember responses. In contrast, bv‐FTD patients did not seem to use the accessibility of contextual information as a cue for making FOK judgments, but rather based their predictions on other types of information. The nature of the latter remains to be determined; it may include, for example, beliefs about their memory function in general.

Analyses of the FDG‐PET images indicated that bv‐FTD patients had reduced metabolic activity in regions typically associated with the disease: bilateral prefrontal cortex and medial frontal regions extending to the anterior cingulate cortex [see Schroeter et al., 2008, for a meta‐analysis], as well as parietal regions [Ishii et al., 1998; Jeong et al., 2005]. More surprising was the consistent finding of a regional decrease of metabolism in the posterior cingulate cortex in the group. Given that this kind of brain dysfunction is characteristic of AD [Herholz et al., 2002; Kawachi et al., 2006; Minoshima et al., 1997], one might wonder whether the bv‐FTD group included patients with atypical AD who manifested initial behavioral and dysexecutive symptoms [Johnson et al., 1999]. However, longitudinal follow‐up evaluations of the patients were not compatible with this hypothesis. In fact, atrophy or hypoperfusion in posterior brain regions has been described increasingly often in some forms of FTD [Le Ber et al., 2008; Rohrer et al., 2010; Whitwell et al., 2009a], and in particular, in a subtype of FTD involving ubiquitin and TDP‐43 (TAR DNA‐binding protein 43) immunoreactive neuronal inclusions [Mackenzie et al., 2008]. Recently, Whitwell et al. [ 2009b] identified a subtype of patients with grey matter loss in the temporal and parietal lobes, posterior cingulate gyrus and medial frontal regions. At the neuropathological level, half of these patients were diagnosed with TDP‐43 pathology. Consequently, it may be that several patients in our sample belonged to this temporofrontoparietal subtype of FTD.

This study is the first attempt to relate the bv‐FTD patients' deficit affecting autonoetic consciousness for recently learned information to metabolic brain function. The only previous study to examine Remember responses in an anterograde memory task found a positive correlation with grey matter volume in a left medial temporal region of interest [Söderlund et al., 2008]. In the present study, in which the functional changes in the brain activity of patients with decreased Remember responses were analyzed by voxel‐wise statistical parametric mapping, the main finding was that bv‐FTD patients with impaired autonoetic consciousness specifically showed reduced metabolism in the left anterior medial frontal cortex, the left middle frontal cortex near the superior frontal sulcus, the right postcentral gyrus, the left inferior parietal cortex, and the posterior cingulate cortex. Despite the small sample, the results were highly significant.

The anterior medial prefrontal cortex has been claimed to be related to the introspective evaluation of internal mental states [Christoff and Gabrieli, 2000]. This process is at the core of the Remember/Know procedure, which requires a subjective judgment of the mental states accompanying recognition. Bv‐FTD patients with impaired autonoetic consciousness also had reduced metabolic activity in the left superior frontal sulcus and parietal regions including the right postcentral gyrus. These regions have been found to be related to self‐referential processing [Wicker et al., 2003] and first‐person perspective [Vogeley et al., 2004], and may form a frontoparietal network supporting the manipulation and monitoring of internally generated information [Christoff and Gabrieli, 2000]. More generally, bv‐FTD patients seem to lose the ability to apprehend mental states, either their own or others, as indicated by their deficit in Theory‐of‐Mind tasks [Adenzato et al., 2010]. Such a deficit may underlie some of the clinical features of bv‐FTD, such as the difficulty understanding social situations [Kipps and Hodges, 2006]. Consistently, bv‐FTD patients failed to adequately perceive their memory functioning in everyday life and tended to overestimate their memory abilities on the Memory Awareness Rating Scale [Clare et al., 2002].

The most innovative aspect of the findings concerns the posterior cingulate hypometabolism in the bv‐FTD patients with impaired autonoetic consciousness. In the brain organisation, the posterior cingulate cortex seems to occupy a special position given its high level of connectivity with parietal, frontal and temporal cortices [Buckner et al., 2009; Greicius et al., 2009]. It is involved in the retrieval of information from episodic memory [Skinner and Fernandes, 2007] and in self‐referential processing [Northoff and Bermpohl, 2004], and more generally in the default mode network [Buckner et al., 2009]. Recently, it has been suggested that the posterior cingulate cortex may be more involved in processes implying reference to one's own person than in episodic memory per se [Cavanna and Trimble, 2006; Sajonz et al., 2010]. In Remember responses, both dimensions are interconnected as these responses are given when participants consciously reactivate a personally experienced episode in all its richness. The difficulty some bv‐FTD patients have in consciously retrieving a past event may stem at least partly from their altered sense of self [Miller et al., 2001], which deprives their memory retrieval of any elaborated personal engagement.

Altogether, the findings are consistent with the impact of a dysfunction of a frontoparietal network on the bv‐FTD patients' episodic memory, but also showed the crucial role of the posterior cingulate cortex, suggesting that deficient access to, monitoring and maintenance of information about the self contributed to impaired autonoetic consciousness.

At a more clinical level, FDG‐PET has been considered as an important biomarker in diagnosing bv‐FTD versus AD, with bv‐FTD being characterized by hypometabolism in anterior regions (frontal and anterior cingulate), whereas AD is typically accompanied by posterior abnormalities (posterior temporoparietal association cortex and posterior cingulate cortex) [Foster et al., 2007]. The current results call for caution in considering posterior cingulate hypometabolism as a specific marker of AD.

One limitation of the analyses of the PET data is the lack of correction for partial volume effects due to the MRI incompatibility of some patients, so that it is not clear how much atrophy contributed to the dysfunction of the frontal and posterior cortical regions in bv‐FTD.

In conclusion, our small sample included patients with clinical features of bv‐FTD, showing specific recollection disturbances, and posterior medial cortex hypometabolism coexisting with the typical frontal alteration. Although the involvement of the posterior cingulate cortex is not typical of bv‐FTD, it has been reported in some forms of the disease. We have proposed the existence of a relationship between episodic memory disturbances and posterior cingulate and frontoparietal self‐related dysfunction in bv‐FTD.

The work was performed at the Cyclotron Research Centre, University of Liège, Belgium.

REFERENCES

- Adenzato M, Cavallo M, Enrici I ( 2010): Theory of mind ability in the behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia: An analysis of the neural, cognitive, and social levels. Neuropsychologia 48: 2–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrés P, Van der Linden M ( 2000): Age‐related differences in supervisory attentional system functions. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 55: 373–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks S, Weintraub S ( 2008): Self‐awareness and self‐monitoring of cognitive and behavioral deficits in behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia, primary progressive aphasia and probable Alzheimer's disease. Brain Cogn 67: 58–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brett M, Anton JL, Valabreque R, Poline JB ( 2002): Region of interest analysis using an SPM toolbox. Abstract presented at the 8th International Conference on Functional Mapping of the Human Brain; June 2–6; Sendai, Japan. Neuroimage 16: 2 (CD‐ROM). [Google Scholar]

- Buckner RL, Sepulcre J, Talukdar T, Krienen FM, Liu H, Hedden T, Andrews‐Hanna JR, Sperling RA, Johnson KA ( 2009): Cortical hubs revealed by intrinsic functional connectivity: Mapping, assessment of stability, and relation to Alzheimer's disease. J Neurosci 29, 1860–1873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess PW, Shallice T ( 1996): Response suppression, initiation and strategy use following frontal lobe lesions. Neuropsychologia 34: 263–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanna AE, Trimble MR ( 2006): The precuneus: A review of its functional anatomy and behavioural correlates. Brain 129: 564–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christoff K, Gabrieli JDE ( 2000): The frontopolar cortex and human cognition: Evidence for a rostrocaudal hierarchical organization within the human prefrontal cortex. Psychobiology 28: 168–186. [Google Scholar]

- Clare L, Wilson BA, Carter G, Roth I, Hodges JR ( 2002): Assessing awareness in early‐stage Alzheimer's disease: Development and piloting of the Memory Awareness Rating Scale. Neuropsychol Rehabil 12: 341–362. [Google Scholar]

- Collette F, Van der Linden M ( 2002): Brain imaging of the central executive component of working memory. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 26: 105–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor LT, Dunlosky J, Hertzog C ( 1997): Age‐related differences in absolute but not relative metamemory accuracy. Psychol Aging 12: 50–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings JL, Mega M, Gray K, Rosenberg‐Thompson S, Carusi DA, Gornbein J ( 1994): The Neuropsychiatric Inventory: comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology 44: 2308–2314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daneman M, Carpenter PA ( 1980): Individual differences in working memory and reading. J Verb Learn Verb Behav 19: 450–466. [Google Scholar]

- Deltour JJ ( 1993): Echelle de vocabulaire de Mill Hill de J.C. Raven. Adaptation française et normes comparées du Mill Hill et du Standard Progressive Matrices (PM 38). Manuel. Braine‐le‐Château: Editions l'Application des Techniques Modernes.

- Desmette D, Hupet M, Van der Linden M ( 1995): Adaptation en langue française du ‘Reading span test’ de Daneman et Carpenter (1980). L'Année Psychologique 95: 459–482. [Google Scholar]

- Dunlosky J, Bjork RA ( 2008): Handbook of Metamemory and Memory. New York: Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Eslinger PJ, Dennis K, Moore P, Antani S, Hauck R, Grossman M ( 2005): Metacognitive deficits in frontotemporal dementia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 76: 1630–1635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster NL, Heidebrink JL, Clark CM, Jagust WJ, Arnold SE, Barbas NR, DeCarli CS, Turner RS, Koeppe RA, Higdon R, Minoshima S ( 2007): FDG‐PET improves accuracy in distinguishing frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer's disease. Brain 130: 2616–2635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner JM ( 1988): Functional aspects of recollective experience. Mem Cogn 16: 309–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greicius MD, Supekar K, Menon V, Dougherty RF ( 2009): Resting‐state functional connectivity reflects structural connectivity in the default mode network. Cereb Cortex 19: 72–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herholz K, Salmon E, Perani D, Baron JC, Holthoff V, Frolich L, Schonknecht P, Ito K, Mielke R, Kalbe E, Zündorf G, Delbeuck X, Pelati O, Anchisi D, Fazio F, Kerrouche N, Desgranges B, Eustache F, Beuthien‐Baumann B, Menzel C, Schröder J, Kato T, Arahata Y, Henze M, Heiss WD ( 2002): Discrimination between Alzheimer dementia and controls by automated analysis of multicenter FDG PET. Neuroimage 17: 302–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges JR, Miller B ( 2001): The neuropsychology of frontal variant frontotemporal dementia and semantic dementia. Introduction to the special topic papers: Part II. Neurocase 7: 113–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii K, Sakamoto S, Sasaki M, Kitagaki H, Yamaji S, Hashimoto M, Imamura T, Shimomura T, Hirono N, Mori E ( 1998): Cerebral glucose metabolism in patients with frontotemporal dementia. J Nucl Med 39: 1875–1878. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong Y, Cho SS, Park JM, Kang SJ, Lee JS, Kang E, Na DL, Kim SE ( 2005): 18F‐FDG PET findings in frontotemporal dementia: an SPM analysis of 29 patients. J Nucl Med 46: 233–239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JK, Head E, Kim R, Starr A, Cotman CW ( 1999): Clinical and pathological evidence for a frontal variant of Alzheimer's disease. Arch Neurol 56: 1233–1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawachi T, Ishii K, Sakamoto S, Sasaki M, Mori T, Yamashita F, Matsuda H, Mori E ( 2006): Comparison of the diagnostic performance of FDG‐PET and VBM‐MRI in very mild Alzheimer's disease. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 33: 801–809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kertesz A, Blair M, McMonagle P, Munoz DG ( 2007): The diagnosis and course of frontotemporal dementia. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 21: 155–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kipps CM, Hodges JR ( 2006): Theory of mind in frontotemporal dementia. Soc Neurosci 1: 235–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koriat A ( 1993): How do we know that we know? The accessibility model of the feeling of knowing. Psychol Rev 100: 609–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Ber I, Camuzat A, Hannequin D, Pasquier F, Guedj E, Rovelet‐Lecrux A, Hahn‐Barma V, van der Zee J, Clot F, Bakchine S, Puel M, Ghanim M, Lacomblez L, Mikol J, Deramecourt V, Lejeune P, de la Sayette V, Belliard S, Vercelletto M, Meyrignac C, Van Broeckhoven C, Lambert JC, Verpillat P, Campion D, Habert MO, Dubois B, Brice A; French research network on FTD/FTD‐MND ( 2008): Phenotype variability in progranulin mutation carriers: A clinical, neuropsychological, imaging and genetic study. Brain 131: 732–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemaire C, Damhaut P, Lauricella B, Mosdzianowski C, Morelle JL, Monclus M, Van Naemen J, Mulleneers E, Aerts J, Plenevaux A, Brihaye C, Luxen A ( 2002): Fast [18 F]FDG synthesis by alkaline hydrolysis on a low polarity solid phase support. J Lab Compd Radiopharm 45: 435–447. [Google Scholar]

- Levinoff EJ, Phillips NA, Verret L, Babins L, Kelner N, Akerib V, Chertkow H ( 2006): Cognitive estimation impairment in Alzheimer disease and mild cognitive impairment. Neuropsychology 20: 123–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackenzie IRA, Foti D, Woulfe J, Hurwitz TA ( 2008): Atypical frontotemporal lobar degeneration with ubiquitin‐positive, TDP‐43‐negative neuronal inclusions Brain 131: 1282–1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattis S ( 1973): Dementia Rating Scale. Windsor, UK: NFER‐Nelson. [Google Scholar]

- Matuszweski V, Piolino P, De La Sayette V, Lalevée C, Pélerin A, Dupuy B, Viader F, Eustache F, Desgranges B ( 2006): Retrieval mechanisms for autobiographical memories: Insights from the frontal variant of frontotemporal dementia. Neuropsychologia 44: 2386–2397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKhann GM, Albert MS, Grossman M, Miller B, Dickson D, Trojanowski JQ ( 2001): Clinical and pathological diagnosis of frontotemporal dementia. Report of the work group on frontotemporal dementia and Pick's disease. Arch Neurol 58: 1803–1809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendez MF, Cummings JL ( 2003): Dementia: A Clinical Approach. Philadelphia, PA: Butterworth‐Heinemann (Elsevier). [Google Scholar]

- Miller BL, Seeley WW, Mychack P, Rosen HJ, Mena I, Boone K ( 2001): Neuroanatomy of the self: Evidence from patients with frontotemporal dementia. Neurology 57: 817–821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minoshima S, Giordani B, Berent S, Frey KA, Foster NL, Kuhl DE ( 1997): Metabolic reduction in the posterior cingulate cortex in very early Alzheimer's disease. Ann Neurol 42: 85–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neary D, Snowden JS, Gustafson L, Passant U, Stuss D, Black S, Freedman M, Kertesz A, Robert PH, Albert M, Boone K, Miller BL, Cummings J, Benson DF ( 1998): Frontotemporal lobar degeneration: A consensus on clinical diagnostic criteria. Neurology 51: 1546–1554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Northoff G, Bermpohl F ( 2004): Cortical midline structures and the self. Trends Cogn Sci 8: 102–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piolino P, Chételat G, Matuszweski V, Landeau B, Mézenge F, Viader F, De La Sayette V, Eustache F, Desgranges B ( 2007): In search of autobiographical memories: A PET study in the frontal variant of frontotemporal dementia. Neuropsychologia 45: 2730–2743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohrer JD, Ridgway GR, Modat M, Ourselin S, Mead S, Fox NC, Rossor MN, Warren JD ( 2010): Distinct profiles of brain atrophy in frontotemporal lobal degeneration caused by progranulin and tau mutations. Neuroimage 53: 1070–1076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen HJ, Alcantar O, Rothlind J, Sturm V, Kramer JH, Weiner M, Miller BL ( 2010): Neuroanatomical correlates of cognitive self‐appraisal in neurodegenerative disease. Neuroimage 49: 3358–3364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruby P, Schmidt C, Hogge M, D'Argembeau A, Collette F, Salmon E ( 2007): Social mind representation: Where does it fail in frontotemporal dementia? J Cogn Neurosci 19: 1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sajonz B, Kahnt T, Margulies D, Park SQ, Wittmann A, Stoy M, Ströhle A, Heinz A, Northoff G, Bermpohl F ( 2010): Delineating self‐referential processing from episodic memory retrieval: Common and dissociable networks. Neuroimage 50: 1606–1617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salmon E, Perani D, Collette F, Feyers D, Kalbe E, Holthoff V, Sorbi S, Herholz K ( 2008): A comparison of unawareness in frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer's disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 79: 176–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schraw G ( 1995): Measures of feeling of knowing accuracy: A new look at an old problem. Appl Cogn Psychol 9: 321–332. [Google Scholar]

- Schroeter ML, Raczka K, Neumann J, von Cramon DY ( 2008): Neural networks in frontotemporal dementia: A meta‐analysis. Neurobiol Aging 29: 418–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner EI, Fernandes MA ( 2007): Neural correlates of recollection and familiarity: A review of neuroimaging and patient data. Neuropsychologia 45: 2163–2179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snodgrass JG, Corwin J ( 1988): Pragmatics of measuring recognition memory: Applications to dementia and amnesia. J Exp Psychol Gen 117: 34–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Söderlund H, Black SE, Miller BL, Freedman M, Levine B ( 2008): Episodic memory and regional atrophy in frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Neuropsychologia 46: 127–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souchay C, Isingrini M, Pillon B, Gil R ( 2003): Metamemory accuracy in Alzheimer's disease and frontotemporal lobe dementia. Neurocase 9: 482–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souchay C, Moulin CJA, Clarys D, Taconnat L, Isingrini M ( 2007): Diminished episodic memory awareness in older adults: Evidence from feeling‐of‐knowing and recollection. Conscious Cogn 16: 769–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tulving E ( 2002): Episodic memory: From mind to brain. Ann Rev Psychol 53: 1–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogeley K, May M, Ritzl A, Falkai P, Zilles K, Fink GR ( 2004): Neural correlates of first‐person perspective as one constituent of human self‐consciousness. J Cogn Neurosci 16: 817–827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitwell JL, Jack CR, Boeve BF, Senjem ML, Baker M, Rademakers R, Ivnik RJ, Knopman DS, Wszolek ZK, Petersen RC, Josephs KA ( 2009a) Voxel‐based morphometry patterns of atrophy in FTLD with mutations in MAPT or PGRN. Neurology 72: 813–820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitwell JL, Przybelski SA, Weigand SD, Ivnik RJ, Vemuri P, Gunter JL, Senjem ML, Shiung MM, Boeve BF, Knopman DS, Parisi JE, Dickson DW, Petersen RC, Jack CR Jr, Josephs KA ( 2009b) Distinct anatomical subtypes of the behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia: A cluster analysis study. Brain 132: 2932–2946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wicker B, Ruby P, Royet JP, Fonlupt P ( 2003): A relation between rest and the self in the brain? Brain Res Rev 43: 224–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yakushev I, Landvogt C, Buchholz HG, Fellgiebel A, Hammers A, Scheurich A, Schmidtmann I, Gerhard A, Schreckenberger M, Bartenstein P ( 2008): Choice of reference area in studies of Alzheimer's disease using positron emission tomography with fluorodeoxyglucose‐F18. Psychiatry Res Neuroim 164: 143–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]