Abstract

Kin recognition, an evolutionary phenomenon ubiquitous among phyla, is thought to promote an individual's genes by facilitating nepotism and avoidance of inbreeding. Whereas isolating and studying kin recognition mechanisms in humans using auditory and visual stimuli is problematic because of the high degree of conscious recognition of the individual involved, kin recognition based on body odors is done predominantly without conscious recognition. Using this, we mapped the neural substrates of human kin recognition by acquiring measures of regional cerebral blood flow from women smelling the body odors of either their sister or their same‐sex friend. The initial behavioral experiment demonstrated that accurate identification of kin is performed with a low conscious recognition. The subsequent neuroimaging experiment demonstrated that olfactory based kin recognition in women recruited the frontal‐temporal junction, the insula, and the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex; the latter area is implicated in the coding of self‐referent processing and kin recognition. We further show that the neuronal response is seemingly independent of conscious identification of the individual source, demonstrating that humans have an odor based kin detection system akin to what has been shown for other mammals. Hum Brain Mapp 2009. © 2008 Wiley‐Liss, Inc.

Keywords: kin recognition, self‐referent processing, neuroimaging, body odor

INTRODUCTION

The ability to identify kin is ubiquitous among phyla (Lieberman et al.,2007). Ranging from microbes (Mehdiabadi et al.,2006) to humans (Porter and Moore,1981), species have developed intricate mechanisms to distinguish kin from non kin. Kin recognition is thought of as a vital evolutionary tool to promote one's genes by facilitating both nepotism and inbreeding avoidance (Ables et al.,2007). Research in animals demonstrates that kin recognition mechanisms have emerged within several senses, lending further support to its evolutionary importance (Baglione et al.,2003; Parr and de Waal,1999; Sharp et al.,2005; Sinervo et al.,2006).

It has long been known and is a well established fact that humans are capable of distinguishing kin from non kin based solely on cues originating from body odors (Porter and Moore,1981; Porter et al.,1985; Schaal and Marlier,1998; Weisfeld et al.,2003). Using event related potentials, Pause et al. (2006) recently demonstrated a clear difference in the electro cortical response when an individual smells body odors originating from genetically similar and dissimilar individuals. This processing difference occurred in the absence of a behavioral response, thereby demonstrating the ability of the human brain to discriminate between different individuals' perceptually similar body odors. This was the first study to demonstrate that the human brain can extract and process genetic information from body odors. Similarly, it was recently demonstrated that body odors are processed by a neuronal network largely separate from the common olfactory system (Lundstrom et al.,2008). Body odors did not activate what is commonly referred to as primary and secondary olfactory cortex, the piriform and orbitofrontal cortex (Zatorre et al.,1992). Instead, body odors activated cortical areas known to process emotional stimuli, as well as an area regarded as an important node in the formation of the body percept. The perceptually similar control odor evoked activation in olfactory cortices. This clear separation in neuronal processing between perceptually similar odors indicates that human body odors contain signals capable of triggering processes outside the common perceptual spectra. To date, however, no attempts have been made to map the neuronal substrates of human kin recognition in the absence of conscious identification of the individual.

Experimentally isolating and assessing kin recognition using auditory and visual stimuli is problematic in humans owing to the ease with which one can readily identify the individual. This high degree of conscious recognition leads to memories associated with the identified individual, and processing the associated conscious memories is thought to mask the neuronal responses of a more biologically mediated kin recognition process. Behavioral data show, however, that correct identification of an individual's body odor is performed with a low level of conscious awareness (Lundstrom et al.,2008). Thus, it should be possible to assess the human kin recognition network with limited involvement of conscious cognitive processes using body odor.

We sought to explore the mechanisms underlying olfactory kin recognition in two consecutive experiments, both using the same cohort of participating women. In Experiment 1, we assessed the participants' ability to recognize body odors originating from either a sister or a longtime friend. In Experiment 2, we sought to determine and map the neuronal substrates of olfactory kin recognition. The use of H2O15 positron emission tomography (PET) allowed us the unique opportunity to capture images while presenting the participants directly with unaltered body odors originating from either their sister or their longtime friend. The results of previous body odor studies have tentatively indicated that self‐referent processing may mediate body odor identification (Lundstrom et al.,2008; Pause et al.,1999). Based on those findings, we hypothesized that areas previously implicated in self‐referent processing, such as the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex and precentral gyrus (Northoff et al.,2006; Platek et al.,2005), would be recruited during kin recognition processing.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experiment 1

Participants

Twelve healthy, right‐handed, nulliparous, nonsmoking women (mean age 24 years; SD ± 2.8) with an absence of nasal congestion, sinus infection, allergies, or decreased olfactory function underwent a behavioral experiment (Experiment 1) and a PET imaging experiment (Experiment 2). Only self‐described exclusively heterosexual women participated, either as “full participants” or as odor donors. Moreover, participants were not allowed to invite odor donors with a known history of diabetes, using psychopharmaca, or using hormonal substances, excluding oral contraceptives. These inclusion criteria were used because preference for body odors and their production are influenced by sex, sexual orientation, certain medications, and diabetes (Martins et al.,2005; Wysocki and Preti,2000). Participants were part of a previously reported body odor neuroimaging experiment in our lab (Lundstrom et al.,2008) and were thus familiar with all procedures. Detailed written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to enrollment, and the experimental protocols were approved by the local Research Ethics Board.

Odor stimuli

Body odors were collected from each participant's biological sister (mean age 23 years; SD ± 4.0) and close woman friend (mean age 22 years; SD ± 2.7) of long‐standing (mean length of friendship, 50 months) without being roommates. A Student's t‐test indicated that there was no significant difference in age between the two odor donor categories, t (11) = 0.97, P > 0.35. To collect the body odors, each odor donor slept for seven consecutive nights alone in their bed wearing a tight cotton t‐shirt in which odorless cotton nursing pads (Ultra‐Thin Nursing Pads, Gerber Inc., ON, Canada) had been sewn into the underarm area. The t‐shirt was used to prevent the cotton pads from being contaminated by external odor sources and to ensure a close fit of the pads in the armpit. When not worn in bed, the t‐shirts were stored in a closed zip‐lock bag. Prior to insertion of the pads, the t‐shirts and any bedding used by the participants were washed with a nearly odor‐free detergent provided by the experimenters. All odor donors followed strict instructions that regulated their personal hygiene and diet to ensure that the collected samples were not contaminated. To prevent identification of an individual's body odor due to dietary choices (Wysocki and Preti,2000), eating spicy food, garlic, or asparagus was prohibited during the whole study period. After behavioral testing, as described later, the pads were sealed in individual odor‐free freezer bags and deep frozen (−80°C) until the morning of the day of scanning (Experiment 2) to prevent further biological degradation of the stimuli.

Behavioral testing session

Participants returned the t‐shirts on the morning of the eighth day when an experimenter removed the pads and subsequently screened them for any contamination of residual, nonbody odor related odors. None of the t‐shirts were deemed to be contaminated. That all participants possessed a functional olfactory sense was initially assessed using a five‐item olfactory identification test consisting of easily identifiable items selected from the Sniffin' Sticks test (Hummel et al.,1997). All subjects had four or more correct identifications, indicating a functional sense of smell. Ability to identify individual body odors was assessed in a counterbalanced order using a psychophysical testing paradigm. A three‐alternative, no feedback, forced‐choice task with nine repetitions for each body odor category (sister and friend), with body odors from strangers as foils, was administered. The body odor of strangers were those collected from other participants. On each trial, participants indicated how confident they were in their answer using a six point scale ranging from “guessing” to “absolutely sure”.

Statistical analyses

Behavioral identification performance above chance value (3) for each body odor category was assessed with separate one‐sample Student's t‐tests.

Experiment 2

Participants

Participants were those described for Experiment 1.

Odor stimuli

The same body odors used in Experiment 1, except for the body odor of strangers, were used in Experiment 2. In addition, an odor control was used. The odor control was a mixture of cumin oil, anise oil, and indole, all dissolved in diethyl phthalate (DEP) down to a concentration of 1% v/v (chemicals obtained from Sigma‐Aldrich, Canada). The stock solution consisted of 60% v/v of the cumin oil solution, 14% v/v of the anise oil solution, and 36% v/v of the indole solution. None of these chemicals can be found naturally in human sweat. This mixture was described as close to a natural body odor in its quality when rated by a pilot group (n = 8) and deemed to be similar to natural body odors in pleasantness, intensity, and irritability. A 10% v/v concentration of this mixture was applied to cotton nursing pads identical to those containing the natural body odors; these cotton pads were subject to similar handling as the pads containing natural body odors.

PET scanning session

The PET session consisted of four conditions [odor‐free baseline, odor control, sister's body odor (sister), and friend's body odor (Friend)], each repeated twice in a pseudo‐randomized order yielding a total of 8 individual scans, each 60 s long. Participants were informed that all body odors within each scan would originate from the same category, i.e., body odors from only one individual were presented in any given scan. The cotton pads were positioned inside wide‐mouth glass jars and presented during scanning by placing the bottle ∼10 mm under the participant's nose. Stimulus onset was 10 s prior to bolus onset and ended ∼10 s after scanning termination. Stimuli were presented for 3 s with 5 s interstimulus intervals of no odor, thereby yielding a total of 10 stimulus presentations in each scan. This intermittent stimulus presentation was performed to limit the degree of natural adaptation to the odor sources. Scanning was performed with eyes open so that the participants would be able to synchronize their breathing with the onset of the stimulus presentation. Presentation of the different stimuli was identical, and only the odor contained on the pad inside the jar varied across presentations. Participants were instructed to focus their gaze on a designated mark located inside a circumference of the camera directly above their heads and to breathe normally and consistently throughout all scans, regardless of the valence or intensity of the stimuli. In addition, to ensure that participants focused on the stimuli, they were asked during each presentation to indicate with a mouse click whether the stimulus was perceived as stronger or weaker than the previous one. No emphasis was placed on the speed of their response. To prevent sniffing behavior that might activate cortical areas associated with olfactory search, participants were informed when a blank stimulus would be presented (odor‐free baseline) and were instructed to respond with a random click during each stimulus presentation in this condition. Breathing was monitored with chest and abdominal respiratory belts, and no significant differences in either amplitudes or respiratory rates between scans were observed. At the end of each scan, the stimulus was rated for perceived pleasantness and intensity using a verbal 10 point scale. Lastly, participants were asked to identify the body odors used in the scan by selecting one of the following categories: Sister, friend, stranger, or common odor. The choice of Stranger was included to enable participants to respond according to the potential sensation of ‘a nonidentifiable body odor’. Each scan was followed by a minimum of 10 min rest to prevent olfactory adaptation.

Acquiring of images and data analyses

PET scans were obtained with a Siemens Exact HR+ tomograph operating in three‐dimensional acquisition mode using H2O15 water bolus. T1‐weighted structural MRI scans (160 1 mm slices) were obtained for each subject with a 1.5 T Siemens Sonata to provide anatomical detail. PET images were reconstructed using a 14 mm Hanning filter and processed using conventional methods (Zatorre et al.,1999). Statistical imaging analyses were done using the in‐house program “DOT” as described in detail elsewhere (Worsley et al.,1992). The presence of significant changes in cerebral blood flow (CBF) was initially established on the basis of an exploratory global search for which the t‐value criterion was set at >3.5. This value corresponds to an uncorrected P‐value of < 0.0002 for a whole‐brain search volume. Because of the conservative nature of conjunction analyses (Nichols et al.,2005), we established the presence of significant changes of CBF in the conjunction analysis based on a t‐value criterion of >3.0, corresponding to an uncorrected P‐value of < 0.001 for a whole‐brain search volume. Specifics of the conjunction analyses are explained later.

Potential differences in perceived intensity and pleasantness of the odor categories (friend, sister, and odor control) were assessed with individual repeated measures analyses of variance (rm‐ANOVA). Alpha‐level was set at 0.05 in all analyses using Greenhouse‐Geisser correction on variables failing Mauchly's test of sphericity.

RESULTS

Experiment 1—Behavioral Identification of Body Odor

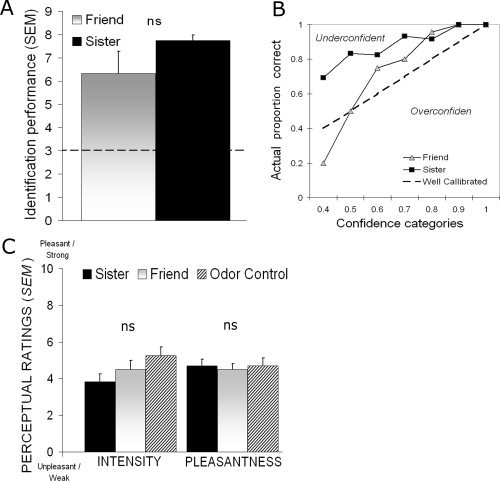

Participants were able to correctly identify their sister's [mean value = 7.7, SD ± 0.67; t (11) = 20.77, P < 0.01] and their friend's body odor [mean value = 6.5, SD ±3.26; t (11) = 3.71, P < 0.01] above chance values when compared with the body odors of strangers (Fig. 1A) in a three alternative, force‐choice task with nine repetitions. A paired samples Student's t‐test indicated that there was no significant difference in identification performance between the two body odor categories (sister or friend), t(11) = 1.14, P > 0.28. One assumption of the design was that identification of the body odors would be made with a low degree of conscious recognition. We are here defining conscious recognition to mean correctly identifying the individual from whom the odor originated and being aware of making a correct identification. To explore this issue, we evaluated the agreement between participants' conscious judgment and their behavioral performance on the identification task by calculating an over or underconfidence score (O/U). Confidence is commonly measured in the meta‐cognitive literature as the difference between the mean subjective probability of being correct, P, and the actual proportion of correct discriminations, C (Bjorkman et al.,1993); this difference, P—C, is expressed as an O/U score. Responses are said to be calibrated to the extent that the proportion of correct choices matches the subjective probability, i.e., an O/U score of 0, and a large mismatch between actual performance and subjective confidence, i.e., underconfidence, is thought of as a measure of nonconscious processing (Bjorkman et al.,1993; Juslin et al.,1999). As can be seen in Figure 1B, identification of sisters was poorly calibrated with conscious awareness of actual identification performance (O/U = −0.24), whereas there was a better agreement, albeit still quite low, for friends (O/U = −0.13). This demonstrates that correct identification of the body odors of kin was performed with low conscious recognition. The low level of conscious awareness of their abilities was further evident during the behavioral testing. Many subjects expressed frustration with the seemingly impossible task of identifying someone based on their body odor although they unknowingly were able to perform the task with good accuracy.

Figure 1.

A: Average identification performance in each body odor category in Experiment 1. The dotted line represents chance performance and error bars denote standard error of the mean (SEM). B: Confidence judgments plotted against actual proportion of correct answers for the two body odor categories. The dotted line represents perfect calibration, indicating that subjective experience is well matched to actual performance. Values above the line indicate underconfidence in performance, whereas values below the line indicate overconfidence. Note the relationship between excellent identification performance and large underconfidence when subjects were identifying body odors from sister. C: Group averaged ratings of perceived intensity and pleasantness of the three experimental odors in Experiment 2. Error bars in graph denote standard error of the mean (SEM).

To explore further whether identification performance was modulated by degree of familiarity with the body odors, we correlated the length of friendship with accuracy in identifying a friend. There was no significant correlation between length of friendship and identification performance according to a bivariate Pearson correlation analysis, r(12) = 0.279, P > 0.38.

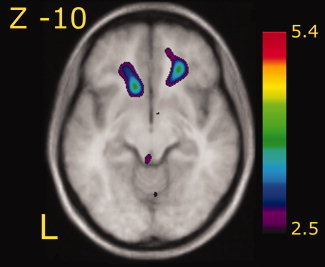

Experiment 2—Neural Mapping

Cortical processing of odorous stimuli often elicits weak regional cerebral blood flow (rCBF) activity in comparison with other sensory stimuli. To verify that our paradigm had enough power to evoke increased neuronal activity in areas commonly thought to process olfactory stimuli, we contrasted the odor control versus baseline. This contrast revealed that the odor control, consisting of a mixture perceptually similar to body odors, elicited clear bilateral activation of the orbitofrontal cortex (see Fig. 2), an area known to process olfactory stimuli (Gottfried and Zald,2005; Zatorre et al.,1992).

Figure 2.

A statistical parametric map (t statistics as represented by the color scale) showing group averaged rCBF response to the processing of the odor control [contrast odor control vs. baseline] superimposed on group averaged anatomical MRI. Significant increase of rCBF is seen bilaterally in the orbitofrontal cortex (x, y, z: −13, 22, −14; t = 3.68 and 23, 34, −8; t = 3.81). Coordinates in figure and figure legend denotes slice and peak activations expressed according to the MNI coordinates system. Left in figure represents left side (L).

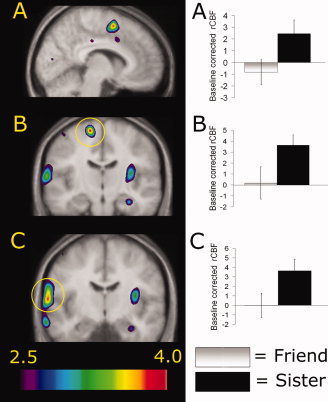

To identify the neuronal substrates of kin recognition, we contrasted activations obtained while smelling sister with activations obtained while smelling Friend (Table IA), two familiar stimuli originating from individuals of the same sex. This contrast yielded increased rCBF above threshold in the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex, frontal‐temporal junction, intraparietal lobula, precentral gyrus, postcentral gyrus, occipital gyrus, and in the culmen (see Fig. 3). As this is the first neuroimaging study to map the neuronal substrates of olfactory kin recognition, comparison of these results with previous studies is not possible. Therefore, in an effort to apply a more conservative approach, we performed a conjunction analysis to explore regions that were commonly activated in the two kin detection contrasts [sister vs. friend + sister vs. baseline (Table IB)]. Conjunction analyses identify activations consistently found in all individually included images within the contrast, whereas subtraction analyses rely only on the average contrast (Nichols et al..2005). Hence, conjunction analyses provide a more conservative measure of the variable of interest. The resulting activations from the conjunction analyses were similar to those of the aforementioned contrast, with the main exception of activations in the insular cortex and the precuneus (Table II).

Table I.

Significant peaks of increased rCBF for kin detection

| A: Sister vs friend (kin detection) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Area | x | y | z | t‐value |

| Frontal lobe | ||||

| Precentral gyrus | −62 | 3 | 15 | 4.0 |

| Superior frontal gyrus/SMA | −14 | −18 | 66 | 3.8 |

| Dorsomedial prefrontal cortex | −7 | 5 | 55 | 3.8 |

| Frontal‐temporal junction | −65 | −11 | 10 | 3.7 |

| Parietal lobe | ||||

| Intraparietal lobula | −65 | −43 | 36 | 3.9 |

| Postcentral gyrus | −43 | −26 | 63 | 3.7 |

| Postcentral gyrus | 25 | −42 | 66 | 3.5 |

| Occipital lobe | ||||

| Occipital cortex | −19 | −100 | −5 | 3.6 |

| Cerebellum | ||||

| Culmen | 4 | −62 | −17 | 3.9 |

| B: Sister vs baseline | ||||

| Area | x | y | z | t‐value |

| Frontal lobe | ||||

| Medial cingulate cortex | −5 | 15 | 35 | 4.3 |

| Anterior cingulate cortex | −5 | 32 | 9 | 4.2 |

| Superior frontal gyrus | −12 | −19 | 64 | 4.0 |

| Medial cingulate cortex | −9 | −14 | 42 | 3.8 |

| Posterior Medial frontal gyrus | 39 | −2 | 32 | 3.8 |

| Dorsomedial prefrontal cortex | −8 | 6 | 54 | 3.7 |

| Fronto‐temporal junction | −64 | −7 | 9 | 3.7 |

| Parietal lobe | ||||

| Postcentral gyrus | −44 | −33 | 60 | 5.3 |

| Posterior cingulate cortex | −9 | −42 | 34 | 4.3 |

| Angular gyrus | 27 | −50 | 48 | 4.1 |

| Posterior cingulate cortex/Pre‐Cuneus | −12 | −52 | 36 | 4.0 |

| Occipital lobe | ||||

| Occipital cortex | −17 | −100 | −12 | 5.2 |

| Peri‐insular regions | ||||

| Parietal operculum | 39 | −33 | 28 | 4.0 |

| Insular cortex | 32 | −14 | 11 | 3.5 |

| Cerebellum | ||||

| Culmen | 3 | −64 | −17 | 4.4 |

Anatomical labels follow the nomenclature of the Mai atlas. Positive values denote a right‐sided activation, whereas negative values denote a left‐sided activation. Peak locations are expressed in MNI coordinates.

Figure 3.

Statistical parametric maps (t statistics as represented by the color scale) of group averaged rCBF responses to kin recognition [contrast sister vs. friend] superimposed on group averaged anatomical MRI. Graphs represent extracted baseline‐corrected rCBF values within the activation peak in question, using a 7 mm volume of interest (VOI) search sphere, in each odor category. Error bars represent standard error of the mean (SEM). All statistical parametric maps are thresholded at t = 2.5. A: Increased rCBF in the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex (X = −7). B: Increased rCBF in the superior frontal gyrus (SMA) as marked by the yellow circle (Y = −18). C: Increased rCBF in the frontal‐temporal junction as marked by the yellow circle (Y = −11). Left in figure represents left side.

Table II.

Significant peaks of increased rCBF for conjunction analyses

| Kin detection [conjunction analyses] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Area | x | y | z | t‐value |

| Frontal lobe | ||||

| Superior frontal gyrus/SMA | −15 | −18 | 65 | 3.8 |

| Frontal‐temporal junction | −63 | −9 | 9 | 3.6 |

| extending into Precentral gyrus | −63 | 0 | 17 | 3.6 |

| Dorsomedial prefrontal cortex | −8 | 6 | 54 | 3.2 |

| Parietal lobe | ||||

| Postcentral gyrus | −43 | −26 | 63 | 3.7 |

| Medial postcentral gyrus | −13 | −38 | 60 | 3.2 |

| Precuneus | −15 | −50 | 37 | 3.1 |

| Occipital lobe | ||||

| Occipital cortex | −19 | −100 | −5 | 3.6 |

| Peri‐insular regions | ||||

| Insular cortex | 34 | −14 | 13 | 3.1 |

| Cerebellum | ||||

| Culmen | 4 | −62 | −17 | 3.9 |

Anatomical labels follow the nomenclature of the Mai atlas. Positive values denote a right‐sided activation, whereas negative values denote a left‐sided activation. Peak locations are expressed in MNI coordinates

Previous studies of body odor processing have implied that self‐referent processing might mediate body odor identification in a nonconscious manner (Lundstrom et al.,2008; Pause et al.,1999). We did not obtain confidence judgments during scanning because of the free identification task. Moreover, only two repetitions were performed of each odor category, which put limits on the use of inference statistics. However, in an effort to explore potential differences in identification performance between sister and friend scans and to assess potential involvement of conscious identification of sisters, we first performed a paired samples Student's t‐test, which demonstrated a statistical tendency for better identification of sisters during scanning, t(11) 1.91, P < 0.10. We thereafter explored whether the activation in the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex (Fig. 3A), an area known to be active during self‐referent tasks (Gusnard et al.,2001; Northoff et al.,2006), was modulated by an awareness that the odor was originating from one's sister. We extracted normalized rCBF values from the peak activation in sister scans only, using volume of interest analyses with a 7 mm search sphere corresponding to half the full width of the spatial smoothing filter. We then divided the scans into two categories, scans in which subjects had correctly identified their sister, and scans in which the odor was incorrectly identified as either their friend, a stranger, or as a nonbody odor. There was no significant difference in rCBF when subjects correctly identified the body odor (mean rCBF = 129.17; SEM ± 1.7) compared with when they did not (mean rCBF = 130.44; SEM ± 1.7), as assessed by a two‐tailed independent samples Student's t‐test, t(22) = 0.40, P > 0.69. Similar negative results were obtained from the other activations reported in the sister versus friend contrast, indicating that these results were obtained without conscious identification of the sisters. In addition, in an attempt to access a potential influence of familiarity, scans correctly identified as sister were compared with scans incorrectly identified as Friend with a similar negative outcome. This indicates a limited influence of familiarity. However, it should be noted that participants were not instructed to attempt to identify the odors during scanning. They were directed to focus on intensity differences during scanning and first after each odor block asked to identify the stimulus presented to them. The lack of significant differences among the three odor categories in both perceived intensity, F(2, 22) = 3.72, P > 0.07, and pleasantness, F(2, 22) = 0.33, P > 0.72, when rated inside the scanner further indicates that the odor categories were perceived consciously as similar in their basic percept (Fig. 1C).

DISCUSSION

We can here for the first time delineate the neuronal network responsible for olfactory based kin recognition. Dorsomedial and posterior parts of the prefrontal cortex, postcentral gyrus, and the peri‐insular region seem to work conjunctly with an area surrounding the frontal‐temporal junction to mediate kin detection in the human brain.

The underlying mechanism of kin recognition is thought to depend on either an automatic self‐referent phenotype matching, or an explicitly learned response to one's relatives (Waldman,1988). Recent data indicate that kin recognition judgments seem to be mediated by self‐referent phenotype matching in several species (Mateo and Johnston,2000,2003; Villinger and Waldman,2008). Interestingly, the results of the present study are generally consistent with studies attempting to map the neuronal substrates of self‐referential mental tasks (Gusnard et al.,2001; Northoff et al.,2006). The dorsomedial prefrontal cortex has repeatedly been demonstrated to serve as an important node in tasks demanding self‐referential assessments (Goldberg et al.,2006), and a recent meta‐analysis of self‐referent processing in different sensory modalities provides further support to this notion (Northoff et al.,2006). One should note, however, that the exact location of the peak activation reported in this study is slightly more dorsolateral (x = −8, y = 6, z = 54) than the large cluster reported by Northoff et al. (2006) in their recent meta‐analysis (x = −2, y = 9, z = 49) although still within our smoothing field. Nevertheless, the dorsal parts of the frontal cortex demonstrate widespread interconnections and both afferent and efferent connectivity with large parts of the brain (Pandya and Yeterian,1996; Petrides,2005) with rich connections to regions responsible for emotional processing, memory functions, performance monitoring, and sensory processing (Petrides and Pandya,2006). This extensive connectivity suggests that the medial prefrontal cortex is particularly well suited to regulate behavior and direct responses to environmental stimuli. From this, one can postulate that the medial prefrontal cortex acts as an important node in the neuronal network processing of olfactory kin detection. However, we would like to stress that additional investigations comparing body odor processing to a task that explicitly demands self‐referent processing is needed to confirm this notion. Moreover, whether this neuronal network is specific for odor based kin recognition or whether it is modality independent remains to be determined by comparisons among modalities.

None of the two body odor categories activated either primary or secondary olfactory cortices, the piriform and the orbitofrontal cortex, respectively (Zatorre et al.,1992). However, the perceptually similar odor control did significantly activate the orbitofrontal cortex bilaterally, confirming the reliability of the results. The absence of activity in the piriform cortex in response to odor stimulation is not unusual in PET imaging; to date, several studies using PET report a lack of activity in the piriform cortex (Dade et al.,2001; Djordjevic et al.,2005; Royet et al.,1999,2001; Zald and Pardo,1997; Zatorre and Jones‐Gotman,2000). A possible explanation is that rapid habituation, known to occur in this area (Poellinger et al.,2001; Wilson,2000), creates a transient response to which the PET technique might not be sensitive to.

Visual and auditory stimuli of high social and ecological importance have been shown to be processed in the brain by specialized neuronal networks (Morris et al.,1998; New et al.,2007; Seifritz et al.,2003). We recently demonstrated that endogenous odors receives similar specialized treatment (Lundstrom et al.,2006,2008). These so‐called evolutionary relevant stimuli, which are processed with a low conscious awareness, recruit additional cortical and subcortical areas not commonly active in the processing of stimuli with low evolutionary relevance (Morris et al.,1999; Whalen et al.,1998). Further support of a separation in neuronal processing between odor categories comes from studies on olfactory receptor functions. It was recently demonstrated that the rodent olfactory system consists of at least two separate functional groups of olfactory receptor neurons; one is dedicated to the processing of common odors while another produces innate responses to endogenous odors (Kobayakawa et al.,2007). The behavioral responses might, in addition, be modulated via GABA dependent presynaptic inhibition of the olfactory receptor neurons to correspond with the ecological needs of the individual (Root et al.,2008). Interestingly, a recent study demonstrated that body odors do not activate higher olfactory cortices such as the orbitofrontal cortex (Lundstrom et al.,2008). Whereas a perceptually similar nonbody odor activated, body odors deactivated the orbitofrontal cortex. This implies that ecologically important odors are processed primarily outside of higher order olfactory cortices also in humans, akin to what has previously been demonstrated for visual stimuli (Weiskrantz,1996). In line with this notion is our finding that areas in the frontal cortex, such as the medial prefrontal cortex, and not the known olfactory cortices, play an important role in olfactory based kin recognition.

Platek et al. (2005) recently reported results for a visual self‐referential task judging artificially created kin. Among others, increased activations were observed in the precentral gyrus, the medial prefrontal cortex, the precuneus, and several peri‐hippocampal areas. Several similarities exist between our results and those presented by Platek et al. (2005), such as activation in the precentral gyrus and precuneus. However, some notable discrepancies can be noted. Olfactory kin recognition among sisters activated the insular cortex which has been implicated in numerous perceptual and cognitive phenomena and recently also in facial self‐resemblance (Platek et al.,2008). Facial self‐resemblance has been hypothesized to tap kin recognition mechanisms; however, the insular cortex has previously been involved in the processing of body odors (Lundstrom et al.,2008). Whether the insular cortex is involved in kin recognition judgments or merely responds to body odors per se remains to be elucidated. Interestingly, several of Platek et al. (2005) reported activations occur in or around the hippocampal formation, which was not activated in the present study. Because the hippocampus plays a major role in memory formation and retrieval, this can be interpreted as an increased taxation of memory functions in the task used by Platek and colleagues. The absence of hippocampal activation in our study can be viewed as further evidence that the activation is independent of conscious recognition. Moreover, the medial prefrontal activation reported by Platek et al. is located more posteriorly than ours. Whether this discrepancy in peak location is modality‐dependent remains to be determined. We are, however, able to extend their results in two important ways. First, we demonstrate that the results are not mediated by participants' perceptual evaluation of the stimuli in that they were deemed to be both iso‐intense and of equal pleasantness. Second, our results seem to be independent of the participants' conscious identification of the source of the body odor. Although they performed well in behavioral testing, the participants expressed a large underconfidence in their ability to identify the body odors. Moreover, there was no difference in rCBF activity in the prefrontal cortex between scans in which participants successfully identified their sisters and scans in which sister was incorrectly labeled. In other words, we demonstrate a neuronal network responsible for olfactory kin recognition that is seemingly independent of conscious identification, and therefore indicative of a process performed with a low conscious awareness as previously demonstrated for other sensory stimuli (Morris et al.,1999; Whalen et al.,1998).

We are here able to demonstrate the neuronal substrates of olfactory kin recognition only in women. In an effort to minimize the perceived qualitative differences, no men were included. Although we have no reason to believe that any vast sex difference exists in the neuronal processing of a basic biological task such as kin recognition, we would like to stress that we do not infer that these results are directly generalizable to men. As mentioned earlier, the exact underlying mechanism of kin recognition is yet to be determined. Although one can assume that kin recognition of individual family members is performed in a similar manner, the influence, if any, of implicit learning on the process and whether differences exist in kin recognition between siblings versus between children‐parents are currently unknown. We opted to study kin recognition in biological sisters to reduce the number of redundant variables and for the general availability in our sample population. However, of special interest for future studies would be to study the neuronal response of kin recognition between a mother and her child or between monozygotic twins. Because of their identical genetic composition, monozygotic twins have nearly identical body odors, and behavioral studies have demonstrated that humans cannot discriminate between monozygotic twins' body odors (cf. Roberts et al.,2005). Differences in the cerebral activation of monozygotic twins processing their own body odor and that of their noncohabitant twin compared with that of another sibling would therefore be attributable to an implicit learning of the inevitable minute differences in body odor quality caused by dietary choices and hygiene products. From this, one could infer the degree implicit learning and innate mechanisms play in olfactory kin recognition.

In conclusion, we demonstrate that kin recognition in women is mediated by a distinct neuronal network. The emerging view in the animal literature represents nonhuman kin recognition as mediated by self‐referent phenotype matching (Mateo and Johnston,2003; Villinger and Waldman,2008). Based on our results, we suggest that human kin recognition also may be mediated by self‐referent phenotype matching. In addition to delineating the neuronal substrates of olfactory based kin recognition, these findings are important for several reasons. First, we demonstrate for the first time that kin recognition operates seemingly independent of conscious identification of kin, thereby indicating that this response is an ongoing nonconscious process. Second, we address the controversial existence of a human equivalent to the mechanisms of kin recognition in other animals. We demonstrate using behavioral and neuronal evidence that humans, similarly to other animals, have a kin detection system operating outside conscious awareness by processing signals hidden within the body odor cocktail, seemingly dependent on self‐referential matching.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank the personnel at the McConnell Brain Imaging Center for valuable help, and Amy Gordon for helpful comments on previous versions of this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Ables EM,Kay LM,Mateo JM ( 2007): Rats assess degree of relatedness from human odors. Physiol Behav 90: 726–732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baglione V,Canestrari D,Marcos JM,Ekman J ( 2003): Kin selection in cooperative alliances of carrion crows. Science 300: 1947–1949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjorkman M,Juslin P,Winman A ( 1993): Realism of confidence in sensory discrimination: the underconfidence phenomenon. Percept Psychophys 54: 75–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dade LA,Zatorre RJ,Evans AC,Jones‐Gotman M ( 2001): Working memory in another dimension: Functional imaging of human olfactory working memory. Neuroimage 14: 650–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djordjevic J,Zatorre RJ,Petrides M,Boyle JA,Jones‐Gotman M ( 2005): Functional neuroimaging of odor imagery. Neuroimage 24: 791–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg II,Harel M,Malach R ( 2006): When the brain loses its self: Prefrontal inactivation during sensorimotor processing. Neuron 50: 329–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottfried JA,Zald DH ( 2005): On the scent of human olfactory orbitofrontal cortex: Meta‐analysis and comparison to non‐human primates. Brain Res Brain Res Rev 50: 287–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gusnard DA,Akbudak E,Shulman GL,Raichle ME ( 2001): Medial prefrontal cortex and self‐referential mental activity: Relation to a default mode of brain function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 4259–4264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hummel T,Sekinger B,Wolf SR,Pauli E,Kobal G ( 1997): ‘Sniffin’ sticks': olfactory performance assessed by the combined testing of odor identification, odor discrimination and olfactory threshold. Chem Senses 22: 39–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juslin P,Wennerholm P,Olsson H ( 1999): Format dependence in subjective probability calibration. J Exp Psychol Learn Mem Cogn 25: 1038–1052. [Google Scholar]

- Kobayakawa K,Kobayakawa R,Matsumoto H,Oka Y,Imai T,Ikawa M,Okabe M,Ikeda T,Itohara S,Kikusui T,Mori K,Sakano H ( 2007): Innate versus learned odour processing in the mouse olfactory bulb. Nature 450: 503–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman D,Tooby J,Cosmides L ( 2007): The architecture of human kin detection. Nature 445: 727–731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundstrom JN,Olsson MJ,Schaal B,Hummel T ( 2006): A putative social chemosignal elicits faster cortical responses than perceptually similar odorants. Neuroimage 30: 1340–1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundstrom JN,Boyle JA,Zatorre RJ,Jones‐Gotman M ( 2008): Functional neuronal processing of body odors differ from that of similar common odors. Cereb Cortex 18: 1466–1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martins Y,Preti G,Crabtree CR,Runyan T,Vainius AA,Wysocki CJ ( 2005): Preference for human body odors is influenced by gender and sexual orientation. Psychol Sci 16: 694–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mateo JM,Johnston RE ( 2000): Kin recognition and the ‘armpit effect’: Evidence of self‐referent phenotype matching. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 267: 695–700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mateo JM,Johnston RE ( 2003): Kin recognition by self‐referent phenotype matching: Weighing the evidence. Anim Cogn 6: 73–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehdiabadi NJ,Jack CN,Farnham TT,Platt TG,Kalla SE,Shaulsky G,Queller DC,Strassmann JE ( 2006): Social evolution: Kin preference in a social microbe. Nature 442: 881–882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JS,Ohman A,Dolan RJ ( 1998): Conscious and unconscious emotional learning in the human amygdala. Nature 393: 467–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JS,Ohman A,Dolan RJ ( 1999): A subcortical pathway to the right amygdala mediating “unseen” fear. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96: 1680–1685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- New J,Cosmides L,Tooby J ( 2007): Category‐specific attention for animals reflects ancestral priorities, not expertise. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 16598–16603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols T,Brett M,Andersson J,Wager T,Poline J‐B ( 2005): Valid conjunction inference with the minimum statistic. Neuroimage 25: 653–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Northoff G,Heinzel A,de Greck M,Bermpohl F,Dobrowolny H,Panksepp J ( 2006): Self‐referential processing in our brain—A meta‐analysis of imaging studies on the self. Neuroimage 31: 440–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandya DN,Yeterian EH ( 1996): Comparison of prefrontal architecture and connections. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 351: 1423–1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parr LA,de Waal FBM ( 1999): Visual kin recognition in chimpanzees. Nature 399: 647–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pause BM,Krauel K,Sojka B,Ferstl R ( 1999): Body odor evoked potentials: A new method to study the chemosensory perception of self and non‐self in humans. Genetica 104: 285–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pause BM,Krauel K,Schrader C,Sojka B,Westphal E,Muller‐Ruchholtz W,Ferstl R ( 2006): The human brain is a detector of chemosensorily transmitted HLA‐class I‐similarity in same‐ and opposite‐sex relations. Proc Biol Sci 273: 471–478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrides M ( 2005): Lateral prefrontal cortex: Architectonic and functional organization. Proc Biol Sci 360: 781–795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrides M,Pandya DN ( 2006): Efferent association pathways originating in the caudal prefrontal cortex in the macaque monkey. J Comp Neurol 498: 227–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platek SM,Keenan JP,Mohamed FB ( 2005): Sex differences in the neural correlates of child facial resemblance: An event‐related fMRI study. Neuroimage 25: 1336–1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platek SM,Krill AL,Kemp SM ( 2008): The neural basis of facial resemblance. Neurosci Lett 437: 76–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poellinger A,Thomas R,Lio P,Lee A,Makris N,Rosen BR,Kwong KK ( 2001): Activation and habituation in olfaction—An fMRI study. Neuroimage 13: 547–560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter RH,Moore JD ( 1981): Human kin recognition by olfactory cues. Physiol Behav 27: 493–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter RH,Cernoch JM,Balogh RD ( 1985): Odor signatures and kin recognition. Physiol Behav 34: 445–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts SC,Gosling LM,Spector TD,Miller P,Penn DJ,Petrie M ( 2005): Body odor similarity in noncohabiting twins. Chem Senses 30: 651–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Root CM,Masuyama K,Green DS,Enell LE,Nässel DR,Lee C ( 2008): A presynaptic gain control mechanism fine‐tunes olfactory behavior. Neuron 59: 311–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royet JP,Koenig O,Gregoire MC,Cinotti L,Lavenne F,Le Bars D,Costes N,Vigouroux M,Farget V,Sicard G,Holley A,Mauguiere F,Comar D,Froment JC ( 1999): Functional anatomy of perceptual and semantic processing for odors. J Cogn Neurosci 11: 94–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royet JP,Hudry J,Zald DH,Godinot D,Gregoire MC,Lavenne F,Costes N,Holley A ( 2001): Functional neuroanatomy of different olfactory judgments. Neuroimage 13: 506–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaal B,Marlier L ( 1998): Maternal and paternal perception of individual odor signatures in human amniotic fluid—Potential role in early bonding? Biol Neonate 74: 266–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seifritz E,Esposito F,Neuhoff JG,Luthi A,Mustovic H,Dammann G,von Bardeleben U,Radue EW,Cirillo S,Tedeschi G,Di Salle F ( 2003): Differential sex‐independent amygdala response to infant crying and laughing in parents versus nonparents. Biol Psychiatry 54: 1367–1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp SP,McGowan A,Wood MJ,Hatchwell BJ ( 2005): Learned kin recognition cues in a social bird. Nature 434: 1127–1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinervo B,Chaine A,Clobert J,Calsbeek R,Hazard L,Lancaster L,McAdam AG,Alonzo S,Corrigan G,Hochberg ME ( 2006): Self‐recognition, color signals, and cycles of greenbeard mutualism and altruism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 7372–7377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villinger J,Waldman B ( 2008): Self‐referent MHC type matching in frog tadpoles. Proc Royal Soc B Biol Sci 275: 1225–1230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldman B ( 1988): The Ecology of kin recognition. Ann Rev Ecol Syst 19: 543–571. [Google Scholar]

- Weisfeld GE,Czilli T,Phillips KA,Gall JA,Lichtman CM ( 2003): Possible olfaction‐based mechanisms in human kin recognition and inbreeding avoidance. J Exp Child Psychol 85: 279–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiskrantz L ( 1996): Blindsight revisited. Curr Opin Neurobiol 6: 215–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whalen PJ,Rauch SL,Etcoff NL,McInerney SC,Lee MB,Jenike MA ( 1998): Masked presentations of emotional facial expressions modulate amygdala activity without explicit knowledge. J Neurosci 18: 411–418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson DA ( 2000): Odor specificity of habituation in the rat anterior piriform cortex. J Neurophysiol 83: 139–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worsley KJ,Evans AC,Marrett S,Neelin P ( 1992): A three‐dimensional statistical analysis for CBF activation studies in human brain. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 12: 900–918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wysocki CJ,Preti G ( 2000): Human body odors and their perception. Jpn J Taste Smell 7: 19–42. [Google Scholar]

- Zald DH,Pardo JV ( 1997): Emotion, olfaction, and the human amygdala: Amygdala activation during aversive olfactory stimulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94: 4119–4124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zatorre RJ,Jones‐Gotman M ( 2000): Functional imaging of the chemical senses In: Toga AW,Mazziotta JC, editors. Brain Mapping: The Applications. San Diego: Academic Press; pp 403–424. [Google Scholar]

- Zatorre RJ,Jones‐Gotman M,Evans AC,Meyer E ( 1992): Functional localization and lateralization of human olfactory cortex. Nature 360: 339–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zatorre RJ,Mondor TA,Evans AC ( 1999): Auditory attention to space and frequency activates similar cerebral systems. Neuroimage 10: 544–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]