Abstract

It is well known that most odorants stimulate both the olfactory system and the trigeminal system. However, the overlap between the brain processes involved in each of these sensorial perceptions is still poorly documented. This study aims to compare fMRI brain activations while smelling two odorants of a similar perceived intensity and pleasantness: phenyl ethyl alcohol (a pure olfactory stimulus) and iso‐amyl‐acetate (a bimodal olfactory‐trigeminal stimulus) in a homogeneous sample of 15 healthy, right‐handed female subjects. The analysis deals with the contrasts of brain activation patterns between these two odorant conditions. The results showed a significant recruitment of the right insular cortex, and bilaterally in the cingulate in response to the trigeminal component. These findings are discussed in relation to the characteristics of these odorants compared with those tested in previous studies. Hum Brain Mapp, 2009. © 2008 Wiley‐Liss, Inc.

Keywords: trigeminal, olfaction, smell, fMRI

INTRODUCTION

Numerous cerebral structures are used when humans smell (Lledo et al.,2005; Savic,2001). During the past decade, functional neuroimaging has found that odor perception activates the piriform, enthorinal cortex, and amygdala. The orbito‐frontal cortex, insula, hippocampus, and thalamus are also involved (Brand et al.,2001; Gottfried,2006; Levy et al.,1997; Royet and Plailly,2004; Royet et al.,2003; Savic,2002). However, the overlap between olfactory and trigeminal input remains poorly documented. It is well known that most odorants are bimodal: they stimulate not only the olfactory nerve (CN I), via receptors of the olfactory epithelium, but also the trigeminal nerve (CN V), via free nerve endings and specific receptors located within the respiratory and olfactory epithelium (Brand,2006; Cometto‐Muniz and Cain,1998; Doty et al.,1978).

Few studies have focused on functional neuroimaging dealing with the processes of olfactory versus trigeminal perception. Yousem et al. (1997) compared brain activations between two functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) sessions, one with olfactory stimuli (eugenol, geraniol, methylsalicylate) and the second one with bimodal odorants (ylang‐ylang, patchouli, rosemary). The authors concluded that trigeminal stimulation produced additional cingulate, temporal, cerebellar, and occipital activation compared with olfactory stimulation. Bengtsson et al. (2001) compared activations between males and females when smelling a pure olfactory stimulus (vanillin) and four bimodal stimuli. One (butanol) was unpleasant, the others (cedar oil, lavender oil, eugenol) were pleasant. Savic et al. (2002) in a PET study evaluated brain activations with vanillin (olfactory stimulus) and acetone or butanol (olfactory and trigeminal stimulus). The additional activation caused by trigeminal stimuli was widespread, including in particular the insular cortex, the anterior cingulum, the somato‐sensory cortex, and parts of the thalamus and cerebellum. A recent fMRI study investigated brain activations due to stimulation with puffs of CO2, a non‐odorous trigeminal stimulus, in anosmic subjects compared with normosmic control subjects. Main activations for anosmic subjects were localized in the cerebellum, superior temporal and inferior frontal gyri, and parietal sub‐gyrus (Iannilli et al.,2007). Another recent fMRI study focused on primary olfactory cortex to compare the contrasts due to irritation and hedonic valence between olfactory and bimodal stimuli. The subjects were asked to sniff the odors repeatedly. The main activation due to the irritation was found in the right olfactory tubercle (Zelano et al.,2007).

The varying results found in these studies could be explained by differences in experimental procedure. More particularly, the hedonic valence of a stimulus is a crucial factor in brain activation and could be exacerbated with trigeminal stimuli that are known to induce stinging, irritation or burning. Therefore, differences between the neural networks activated by olfactory and bimodal stimuli could be obscured by emotional responses to the stimuli. The aim of our study was to compare the neural networks activated by olfactory or bimodal stimuli by controlling both the emotional factor and other factors such as age, sex and handedness of subjects.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Subjects

The subjects were 15 right‐handed females, undergraduate students (aged 20–23 years). They were nonsmokers and screened for any possible smell dysfunctions prior to the study. The study was reviewed and approved by the local ethic committee and conducted according to French regulations on biomedical experiments on healthy volunteers. Participation required a medical examination and written informed consent form.

fMRI Data Acquisition

Functional MRI was performed to measure blood‐oxygen‐level‐dependent (BOLD) contrast on a 3‐Tesla (G.E. Healthcare Signa H.D, Milwaukee, WI) MR‐system with a standard 40 mT/m gradient (MRI Unit, Department of Radiology, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Besançon, France). Foam cushions were used to minimize movements of the head within the coil. The entire experience consisted first of the acquisition of a high‐resolution T1‐weighted three‐dimensional anatomical scan. This scan was acquired in 188 slices with 1 mm × 1 mm × 1 mm resolution (GE SPGR SPoiled GRadient echo sequence, 256 × 256 matrix, 256 mm field of view, time of acquisition circa 6 min 12 s). Secondly, BOLD images, parallel to the anterior–posterior commissure line, were obtained covering the entire cerebrum and most of the cerebellum (24 slices) using an echo planar imaging (EPI) sequence (144 measurements; TR = 3000 ms; TE = 35 ms, matrix = 128 × 128; Flip Angle: 90°; FoV = 260 mm; slice thickness = 5.9 mm). fMRI acquisition lasted 7 min 12 s.

Olfactory Stimulant Delivery

Olfactory stimuli was delivered to the subject using a custom‐built olfactometer (adapted from Popp et al.,2004) with a continuous flow rate (2.5 l/min) passing through bottles with cotton pads soaked in distilled water (odorless condition) or in the odorants (iso‐Amyl‐Acetate or Phenyl‐Ethyl‐Alcohol: Sigma–Aldrich, France). Phenyl‐ethyl‐alcohol (PEA: rose‐like odor) and iso‐amyl‐acetate (AA: banana‐like odor) are two common odorants, without painful implications. The former is considered as a selective olfactory stimulus and the latter a mixed olfactory‐trigeminal (bimodal) stimulus (Doty et al.,1978). Furthermore, both stimuli are slightly pleasant (Dravnieks et al.,1984; Hummel et al.,1997).

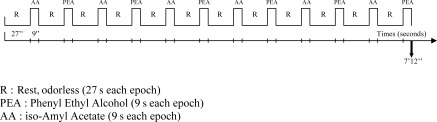

The air flow from odorless or odorant bottles was selected with a designated switch by the experimenter in order to select either odorless or odorant stimulation following the experimental procedure described below. The air flow was delivered from each of the three bottles through separate Teflon tubing (diameter: 1.5 mm) to a commercially available mask. The output end of each of the three tubes was adjusted in the mask to have a distance of 3 cm from the subject's nose. During fMRI, 12 odorless epochs (27 s each) were alternated with 12 epochs with odor (9 s each) as an experimental paradigm. This duration of 9 s was chosen with reference to Poellinger et al. (2001) to minimize habituation with PEA. Brain processes linked to the duration of trigeminal stimulations are still largely unknown. The two odorants were alternated during the whole fMRI session (Fig. 1). The subjects were unaware of the order of presentation of odorants. They were asked to breathe as normal through the nose, without active sniffing (see Sobel et al.,1998) throughout the whole scanning session and to focus on the odors, without performing any other tasks.

Figure 1.

Experimental procedure: Each of the 15 subjects participated in one functional scan of 7 min 12 s with each of the two odorants alternating with odorless epochs. Subjects were asked to breathe regularly throughout the scan. R, rest; odorless (27 s each epoch); PEA, phenyl ethyl alcohol (9 s each epoch); AA, iso‐amyl acetate (9 s each epoch).

Prior to fMRI sessions the concentrations of odorants delivered by the olfactometer were adjusted so that a panel of five trained women (age 20–23 years old) considered the perceived intensities as approximately equal across both odorants (Zelano et al.,2007). The olfactory/trigeminal characteristics of the odorants were also assessed by this same control group by a lateralization task (Stuck et al.,2006). A total of 40 stimuli for each odor were applied to the right or left nasal chamber (20 stimuli each in a random sequence) of the blindfolded subjects (interstimulus interval of approximately 30 s). The other nasal chamber received an equal amount of non‐odorized air. The same olfactometer and concentrations as those used in the fMRI session were used for this purpose except that the tubes arrived separately in each nasal chamber (one with odorless air, one with the odorant). Chi square tests showed correct lateralization judgments for AA (χ2 = 15.68; P < 0.01; df = 1) but not for PEA (χ2 = 2.42; P > 0.1; df = 1). This demonstrated the trigeminal properties of the AA as used in this study.

After fMRI scanning, the subjects were required to describe the intensity and hedonicity of the two odors and to grade them on two perceptual scales from 1 (low intensity, unpleasant) to 10 (high intensity, pleasant).

fMRI Data Analysis

Functional MRI data were statistically analyzed using Brain Voyager™ QX version 1.8 software package (http://www.brainvoyager.com) (Goebel,1996). Three dimensional data preprocessing included head movement assessment, high frequency filtering, spatial (4 mm) and temporal Gaussian smoothing and removal of linear trends. Functional and anatomical images of all participants were transformed into a standard space (Talairach and Tournoux,1988). The differences between rest (odorless air) and odorant conditions, or between two odorant conditions, were statistically evaluated using a general linear model (multi‐study) corresponding to a delayed boxcar design considering the hemodynamic response function (Boynton et al.,1996). The correlation maps were computed according to Friston et al. (1995). Volumetric analysis was performed at a threshold of P = 0.001 (corrected or uncorrected depending on the contrasts). To minimize the risk of false‐positive findings, a minimal cluster size of 50 voxels was systematically selected.

RESULTS

Ratings of Intensity and Hedonicity

The mean scores for perceived intensity by the subjects were 6.87 (SD = 1.30) for AA and 6.2 (SD = 1.15) for PEA. Concerning hedonicity, the mean scores of ratings were 6.93 (SD = 1.83) for AA and 6.13 (SD = 1.25) for PEA. Paired sampled student's t tests demonstrated that the differences were significant neither for intensity (t = 1.79; df = 14, P > 0.05) nor for hedonicity (t = 1.25; df = 14, P > 0.05).

Imaging Data

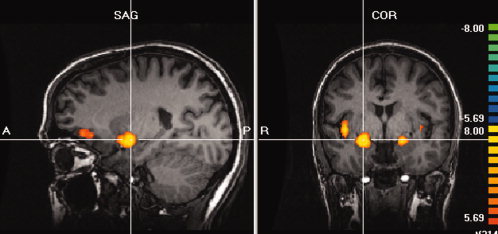

A first contrast (PEA + AA‐air contrast) showed the cerebral activations with both odorants using air as reference (Fig. 2, Table I). Main activations were seen bilaterally with a right predominance in the amygdala and neighboring cortex (i.e. entorhinal and piriform cortices), in the insula (anterior and part of the posterior insula), and in parts of the right anterior and posterior orbital gyrus.

Figure 2.

Cerebral activations with the two odorants, iso‐amyl‐acetate and phenyl‐ethyl‐alcohol, using air as reference (AA + PEA‐air contrast). Main clusters are seen bilaterally in the amygdala and neighboring cortex and in the right insula and orbital gyrus (P < 10−6; corrected).

Table I.

Cerebral activations with both odorants using air as reference

| Brain regions | Talairach coordinates x,y,z (mm) | Cluster size (in voxels) | Significance (P value) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amygdala and neighboring cortex | 23,3,−12 | 914 | <10−6 |

| Amygdala and neighboring cortex | −19,−3,−11 | 602 | <10−6 |

| Insula | 38,0,−3 | 753 | <10−6 |

| Anterior, posterior orbital gyrus | 25,35,−4 | 531 | <10−6 |

| Anterior insula | 34,22,7 | >1,000 | <10−6 |

| Anterior insula | −32,18,7 | 283 | <10−6 |

| Middle and inferior frontal gyrus | 40,38,22 | 863 | <10−6 |

| Superior frontal gyrus | 4,5,54 | 131 | <10−6 |

AA + PEA‐air contrast, PBonferoni = 0.001.

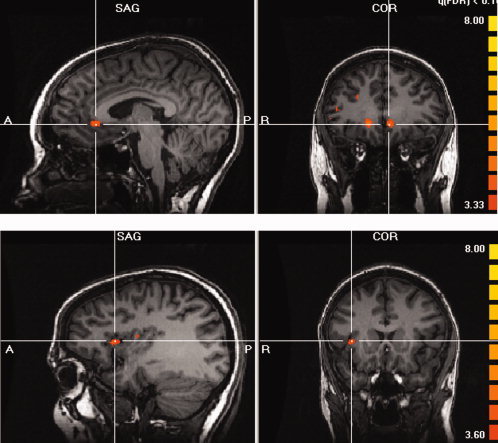

Then a second contrast (AA‐PEA contrast) showed brain activations located mainly in the right hemisphere and were located mainly in the right insula and bilaterally in the anterior cingulate gyrus (Fig. 3, Table II). Cortical gyri (particularly frontal and parietal) were also recruited. For these previous areas, Table II shows activations obtained with the AA‐air contrast. Only three areas identified by the first contrast were not activated in this second contrast, namely the left medial orbital gyrus and the right and left cingulate cortex.

Figure 3.

Cerebral activations with iso‐amyl‐acetate using phenyl‐ethyl‐alcohol as reference (AA‐PEA contrast). Main clusters are seen bilaterally in the anterior cingulate (images in the top) and in the right anterior insula (images in the bottom) (P = 0.001, uncorrected).

Table II.

Cerebral activations with iso‐amyl‐acetate using phenyl‐ethyl‐alcohol as reference (AA‐PEA contrast) (P = 0.001, uncorrected) and activations with AA using air as reference (AA‐air contrast) for the same Talairach coordinates (P = 0.001, uncorrected)

| Brain regions | Talairach coordinates x,y,z (mm) | Cluster size (in voxels) | Significance (P value) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AA‐PEA | AA‐air | AA‐PEA | AA‐air | ||

| Inferior temporal gyrus | 40,−2,−29 | 167 | 149 | 0.00048 | 0.00071 |

| Medial orbital gyrus | −12,43,−14 | 110 | 0 | 0.0005 | |

| Putamen | 17,4,−9 | 156 | >1,000 | 0.00058 | 0.00005 |

| Anterior cingulate | 16,32,−6 | 375 | 0 | 0.00033 | |

| Anterior cingulate | −5,32,−4 | 427 | 0 | 0.00029 | |

| Posterior insula | 37,0,0 | 54 | >1,000 | 0.00072 | 0.00001 |

| Frontal inferior gyrus | 51,35,3 | 106 | 608 | 0.00079 | 0.0003 |

| Frontal inferior gyrus | 31,52,8 | 138 | 540 | 0.00050 | 0.00001 |

| Anterior insula | 34,14,8 | 514 | >1,000 | 0.00039 | 0.00001 |

| Posterior insula | 37,−8,14 | 324 | 779 | 0.0003 | 0.00013 |

| Precentral gyrus | 52,−9,17 | 278 | 670 | 0.00045 | 0.00022 |

| Precentral gyrus | 49,1,25 | 174 | >1,000 | 0.00056 | 0.00012 |

| Superior parietal gyrus | 41,−48,27 | 164 | 593 | 0.00061 | 0.00027 |

| Supramarginal gyrus | 54,−46,39 | 267 | >1,000 | 0.00059 | 0.00009 |

With a third contrast (PEA‐AA contrast), these activations were rarely present with a less right‐hemisphere dominance (Table III). The main clusters of activations were localized in the right inferior occipital gyrus and in the left postcentral gyrus. Table III also shows that for these areas the activations observed with the PEA‐air contrast were only present in the cerebellum.

Table III.

Cerebral activations with phenyl‐ethyl‐alcohol using iso‐amyl‐acetate as reference (PEA‐AA contrast) (P = 0.001, uncorrected) and activations with PEA using air as reference (PEA‐air contrast) for the same Talairach coordinates (P = 0.001, uncorrected)

| Brain regions | Talairach coordinates x,y,z (mm) | Cluster size (in voxels) | Significance (P value) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEA‐AA | PEA‐air | PEA‐AA | PEA‐air | ||

| Cerebellum (vermis) | −6,−66,−35 | 55 | 313 | 0.00058 | 0.000637 |

| Cerebellum | 14,−79,−34 | 51 | 34 | 0.00007 | 0.000844 |

| Inferior occipital gyrus | 31,−82,−22 | 107 | 0 | 0.00072 | |

| Inferior occipital gyrus | 46,−75,−14 | 389 | 0 | 0.00033 | |

| Posterior insula | −40,−24,7 | 70 | 0 | 0.00663 | |

| Postcentral gyrus | −21,−39,60 | 208 | 0 | 0.00055 | |

| Precentral gyrus | 26,−20,64 | 52 | 0 | 0.00076 | |

DISCUSSION

The contrast obtained with both odorants using air as reference (AA + PEA‐air contrasts) shows that with the present experimental conditions we obtained activations similar to those usually mentioned for odorants which are not purely olfactory selective stimulants (Levy et al.,1997; Sobel et al.,2003; Zatorre et al.,1992). Activations of the right medial orbito‐frontal cortex and bilaterally in the anterior insula are also noted by Boyle et al. (2007b) in the case of an “artificial” bimodal odor (PEA and CO2).

The contrast obtained with AA using PEA as reference (AA‐PEA) reveals the brain areas either exclusively recruited or more activated by the trigeminal component of the odorant in the current experimental conditions. Activations were mainly observed in the right insula, and bilaterally in the anterior cingulate.

Activations of the right insula have also been noted by Bengtsson et al. (2001) in an analysis similar to the current one (olfactory‐bimodal odorants contrast) with right‐handed females. Their results are explained by discriminatory tasks, spontaneously executed by the subjects, between the four bimodal odorants used in their study. Savic et al. (2002) observed activations in the insula and claustrum, but in the left hemisphere. This laterality could be due to the strong negative emotional valence of the odorant used (acetone compared with AA in our study) which implies a major involvement of the left hemisphere (Royet and Plailly,2004). However in recent studies, Boyle et al., (2007a) and Iannilli et al. (2007) found a high predominant activity in the right hemisphere (including insula) in normosmic subjects smelling CO2 (described as virtually odorless). The previous results were extended to show that the right insula is part of the perception process even in the case of a moderate trigeminal stimulation with a pleasant valence and without discriminatory tasks operated by the subjects. The involvement of the right insula as a characteristic of a trigeminal stimulation compared with an olfactory one would not be surprising considering its role in the integration of usual sensorial cues: auditory, visual and also somesthesic and gustatory perceptions. Although patients with right insular lesions show low responses to bilateral tactile stimulation, no such impairment was noticed in the case of left insular lesions (Manes et al.,1999). It could be noted that limbic structures have extended interconnections with the anterior part of the insula (Mesulam and Mufson,1982) which was activated in our study.

Activations of the anterior part of the cingulate cortex are mentioned in studies dealing with trigeminal stimulations and they are usually explained by the processing of nociceptive information (Iannilli et al.,2007; Savic et al.,2002). A relatively pleasant stimulus was used in our study and activations in the same brain region are observed. The anterior cingulate is involved in mood induction processes (Habel et al.,2005) and also in attentional processing (Sobel et al.,2003). Furthermore, our results show that this area appears no more activated when the olfactory component of the bimodal stimulation is present (AA‐air contrast). It seems that this area is recruited in trigeminal perception (whatever its pleasantness) perhaps due to an involvement of attentional shift, but less involved in the case of a simultaneous pleasant olfactory stimulation. Thus, its degree of activation during odorant perception could be the result of the integration of several processes: attention due to the mere stimulation or to cognitive tasks (Royet et al.,2001), relative intensities and valence of olfactory and trigeminal components of the stimulation.

In our study, a part of the medial orbital gyrus did not also appear activated in AA‐air contrast. This area is putatively a source of inputs for the anterior cingulate cortex (Cavada et al.,2000). Although right orbitofrontal activation is the usual rule in olfaction imagery, a greater activation in the left than right orbitofrontal cortex has been highlighted only in the case of aversive olfactory stimulation (Royet et al.,2000; Zald and Pardo,1997). Neither anterior cingulate gyri, nor the left orbital gyrus were found to be activated in stimulation with PEA with a similar duration of 9 s in a previous study (Poellinger et al.,2001). The recruitment of these areas would need to be examined while taking into account the hedonic valence and the relative intensity of trigeminal component in bimodal odorants.

As in previous studies (Iannilli et al.,2007; Yousem et al.,1997), we found scattered activities in precentral gyrus (areas associated with facial motor control) and in supplementary sensorial cortex (parietal lobule). The other cortical areas (parts of right inferior temporal and right inferior frontal gyri) can be considered as involved in supplementary cognitive processes specific to the evocative properties of the odorant used (Sobel et al.,2003).

Considering the contrast obtained with PEA using AA as reference (PEA‐AA), it can be assumed that this activity resulted from deactivation caused by the trigeminal component and/or the interaction between the olfactory and trigeminal components (Bengtsson et al.,2001; Savic et al.,2002). Taking into account the results from the other contrast (PEA‐air), it appears that this deactivation by a trigeminal stimulation concerned areas involved in the process of smelling pure odorant (cerebellum) and other areas which are poorly relevant to this task (no activations observed in the PEA‐air contrast: parts of left insula, of occipital, pre‐ and post‐central gyri).

Activations of cerebellum have been previously observed in some olfactory studies (Herz et al.,2004; Qureshy et al.,2000; Savic,2002) and its role in emotion processing has also been acknowledged (Schmahmann,2000). Hence, these localized activations in the cerebellum do not appear linked to a specific type of odorant. It can be thought that the slight difference between the perceived intensities of the two odorants (although it was not significant) was sufficient to produce a difference in the motor control of smelling: sniff volume would be inversely proportional to perceived concentration (Sobel et al.,2003).

Deactivations restricted to the left hemisphere (parietal cortex) have already been noted by Bengtsson et al. (2001) in a similar situation (olfactory‐bimodal odorants contrast). Savic et al. (2002) mentioned largely widespread deactivations in the temporal, parietal and occipital cortex in an analogous contrast (vanillin‐acetone). Our results confirm that trigeminal stimulation produces deactivation not only in areas involved in olfaction but also in areas involved in other sensory or cognitive processes. This widespread effect also appears for a moderate and rather pleasant trigeminal stimulus as it is the case in our study.

Given the method used, and particularly the duration of stimulation by odorants, our study did not attempt to reveal all the areas involved in olfactory and trigeminal perception. Brain areas activated by pure olfactory stimulations differ according to the durations of stimulations (Poellinger,2001) and our study focused on the only areas previously de‐activated by the trigeminal component. Potential modifications of brain activations due to habituation in trigeminal perception are largely unknown in the literature. Only two odorants were used in our study. Although these odorants did not differ significantly in perceived intensity and pleasantness, they each have intrinsic qualities: evocative properties depending on origin and subjects' experience. These slight variations between odorants may be the cause of some scattered cerebellar or cortical activities as mentioned above. The results nevertheless suggested different and complementary pathways characteristic of each of the two sensorial cues (CN I and CN V). The most salient result of our study was a major recruitment of a part of the right insula and of the cingulate in both hemispheres in response to the trigeminal component of a bimodal odorant. The recruitment of these areas appears systematic, whatever the type of trigeminal stimulation and does not seem related to any supplementary emotional (painful), attentional implications or cognitive tasks operated by subjects.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Frances Sheppard for her language assistance in the manuscript. We wish to give special thanks to the Conseil Régional de Franche‐Comté for its financial support allowing the use of the RMI‐3T Scanner for this research.

REFERENCES

- Bengtsson S, Berglund H, Gulyas B, Cohen E, Savic I (2001): Brain activations during odor perception in males and females. Neuroreport 12: 2027–2033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle JA, Heinke M, Gerber J, Frasnelli J, Hummel T (2007a): Cerebral activation to intranasal chemosensory trigeminal stimulation. Chem Senses 32: 343–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle JA, Frasnelli J, Gerber J, Heinke M, Hummel T (2007b): Cross‐modal integration of intranasal stimuli: An fMRI study. Neuroscience 149: 223–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boynton GM, Engel SE, Glover GH, Heeger DJ (1996): Linear systems analysis of functional magnetic resonance imaging in human V1. J Neurosci 16: 4207–4221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand G (2006): Olfactory/trigeminal interactions in nasal chemoreception. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 30: 908–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand G, Millot JL, Henquell D (2001): Complexity of olfactory lateralization processes revealed by cerebral imagery. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 25: 159–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavada C, Company T, Tejedor J, Cruz‐Rizzolo RJ, Reinoso Suarez F (2000): The anatomical connections of the macaque monkey: A review. Cereb Cortex 10: 220–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cometto‐Muniz JE, Cain WE (1998): Trigeminal and olfactory sensitivity comparison of modalities and methods of measurement. Internat Arch Occup Environ Health 71: 105–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doty RL, Brugger WPE, Jurs PC, Orndorff MA, Snyder PJ, Lowry LD (1978): Intranasal trigeminal stimulation from odorous volatiles: psychometric responses from anosmic and normal humans. Physiol Behav 20: 175–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dravnieks A, Masurat T, Lamm RA (1984): Hedonics of odors and odor descriptors. J Air Pollution Control Assoc 34: 752–755. [Google Scholar]

- Friston KJ, Frith CD, Turner R, Frackowiak RS (1995): Characterizing evoked hemodynamics with fMRI. Neuroimage 2: 157–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goebel R (1996): Brainvoyager: A program for analyzing and visualizing functional and structural magnetic resonance data sets. Neuroimage 3: 604. [Google Scholar]

- Gottfried JA (2006): Smell central nervous processing. Adv Oto‐rhino‐laryngol 63: 44–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habel U, Klein M, Kellermann T, Shah J, Schneider F (2005): Same or different? Neural correlates of happy and sad mood in healthy males. Neuroimage 26: 206–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herz RS, Eliassen J, Beland S, Souza T (2004): Neuroimaging evidence for the emotional potency of odor‐evoked memory. Neuropsychologia 42: 371–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hummel T, Sekinger B, Wolf SR, Pauli E, Kobal G (1997): “Sniffing” sticks: Olfactory performance assessed by the combined testing of odor identification, odor discrimination and olfactory threshold. Chem Senses 22: 39–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iannilli E, Gerber J, Frasnelli J, Hummel T (2007): Intranasal trigeminal function in subjects with and without an intact sense of smell. Brain Res 1139: 235–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy LM, Henkin RH, Hutter A, Lin CS, Martins D, Schellinger D (1997): Functional MRI of human olfaction. J Comp Assist Tomogr 21: 849–856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lledo JM, Gheusi G, Vincent JD (2005): Information processing in the mammalian olfactory system. Physiol Rev 85: 281–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manes F, Paradiso S, Springer A, Lamberty G, Robinson R (1999): Neglect after right insular cortex infarction. Stroke 30: 946–948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesulam MM, Mufson E (1982): Insula of the old word monkey. JComparative Neurol 212: 23–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poellinger A, Thomas R, Lio P, Lee A, Makris N, Rosen BR, Kwong KK (2001): Activation and habituation in olfaction: An fMRI study. Neuroimage 13: 547–560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popp R, Sommer M, Müller J, Hajak G (2004): Olfactometry in fMRI studies: Odor presentation using nasal continuous positive airway pressure. Acta Neurobiol Exp 64: 171–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qureshy A, Kawashima R, Imran MB, Sugiura M, Goto R, Okada K, Inoue K, Itoh M, Schormann T, Zilles K, Fukuda H (2000): Functional mapping of human brain in olfactory processing: A PET study. J Neurophysiol 84: 1656–1666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royet JP, Plailly J (2004): Lateralization of olfactory processes. Chem Senses 29: 731–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royet JP, Zald D, Versace R, Costes N, Lavenne F, Koenig O, Gervais R (2000): Emotional responses to pleasant and unpleasant olfactory, visual and auditory stimuli: A positron emission tomography study. J Neurosci 20: 7752–7759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royet JP, Hudry J, Zald DH, Godinot D, Grégoire MC, Lavenne F, Costes N, Holley A (2001): Functional anatomy of different olfactory judgments. Neuroimage 13: 506–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royet JP, Plailly J, Delon‐Martin C, Kareken DA, Segebarth C (2003): fMRI of emotional responses to odors: Influence of hedonic valence and judgment, handedness and gender. Neuroimage 20: 713–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savic I (2001): Processing of odorous signals in humans. Brain Res Bull 54: 307–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savic I (2002): Brain imaging studies of the functional organization of human olfaction. Neuroscientist 8: 204–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savic I, Gulyas B, Berglund H (2002): Odorant differentiated pattern of cerebral activation: Comparison of acetone and vanillin. Hum Brain Mapping 17: 17–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmahmann JD (2000): The role of the cerebellum in affect and psychosis. J Neurolinguist 13: 189–214. [Google Scholar]

- Sobel N, Prabhakaran V, Desmond JE, Glover GH, Goode RL, Sullivan EV, Gabriel JDE (1998): Sniffing and smelling: Separate subsystems in the human olfactory cortex. Nature 392: 282–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobel N, Johnson BN, Mainland J, Yousem D (2003): Functional neuroimaging of human olfaction In: Doty RL, editor. Handbook of Olfaction and Gustation, 2nd ed. New York: Dekker; pp 251–273. [Google Scholar]

- Stuck BA, Frey S, Freiburg C, Hormann K, Zahnert T, Hummel T (2006): Chemosensory event‐related potentials in relation to side of stimulation, age, sex, and stimulus concentration. Clin Neurophysiol 117: 1367–1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talairach J, Tournoux P (1988): Co‐Planar Stereotaxic Atlas of the Human Brain. 3‐Dimensional Proportional System: An Approach to Cerebral Imaging. New York: Thieme Medical. [Google Scholar]

- Yousem DM, Williams SCR, Howard RO, Andrew C, Simmons A, Allin M, Geckle RJ, Suskind D, Bullmore ET, Brammer MJ, Doty RL (1997): Functional MR imaging during odor stimulation: Preliminary data. Radiology 204: 833–838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zald DH, Pardo JV (1997): Emotion, olfaction, and the human amygdala: Amygdala activation during aversive olfactory stimulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94: 4119–4124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zatorre RJ, Jones‐Gotman M, Evans AC, Meyer E (1992): Functional localization and lateralization of human olfactory cortex. Nature 360: 339–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zelano C, Montag J, Johnson B, Khan R, Sobel N (2007): Dissociated representations of irritation and valence in human primary cortex. J Neurophysiol 97: 1969–1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]