Abstract

Anxiety arising during pain expectancy can modulate the subjective experience of pain. However, individuals differ in their sensitivity to pain expectancy. The amygdale and hippocampus were proposed to mediate the behavioral response to aversive stimuli. However, their differential role in mediating anxiety‐related individual differences is not clear. Using fMRI, we investigated brain activity during expectancy to cued or uncued thermal pain applied to the wrist. Following each stimulation participants rated the intensity of the painful experience. Activations in the amygdala and hippocampus were examined with respect to individual differences in harm avoidance (HA) personality trait, and individual sensitivity to expectancy, (i.e. response to cued vs. uncued painful stimuli). Only half of the subjects reported on cued pain as being more painful than uncued pain. In addition, we found a different activation profile for the amygdala and hippocampus during pain expectancy and experience. The amygdala was more active during expectancy and this activity was correlated with HA scores. The hippocampal activity was equally increased during both pain expectancy and experience, and correlated with the individual's sensitivity to expectancy. Our findings suggest that the amygdala supports an innate tendency to approach or avoid pain as reflected in HA trait, whereas the hippocampus mediates the effect of context possibly via appraisal of the stimulus value. Hum Brain Mapp, 2010. © 2009 Wiley‐Liss, Inc.

Keywords: fMRI, harm avoidance, personality, anxiety

INTRODUCTION

During the anticipation of an aversive event, a host of affective and cognitive processes are activated. A major component of these processes is an emotional state of anxiety, involving increased vigilance, arousal, and focused attention, allowing the organism to prepare for and properly cope with the prospective aversive event [Lang et al.,2000]. Although anticipating a negative event is usually adaptive, it may become dysfunctional if recruited excessively or inappropriately, as in the cases of phobia or social anxiety [Nitschke et al.,2006]. In an attempt to characterize the neural mechanism of anxiety in humans, studies have focused either on populations suffering from anxiety disorders, or on healthy individuals in the context of anxiogenic stimuli, such as an induced shock or pain [Chua et al.,1999; Reiman et al.,1989]. Indeed it has been shown that during anticipation of a painful stimulus, the mere awareness that pain is about to be encountered gives rise to anxiety. Such anxiety is manifested physiologically by heart rate acceleration and a subsequent heightened subjective pain response [Fairhurst et al.,2007; Ploghaus et al.,2001]. This context‐related enhancement of perceived pain intensity is in accordance with early behavioral studies showing that uncertainty about impending noxious stimulation increases pain unpleasantness and decreases pain tolerance [Leventhal et al.,1979; Staub et al.,1971]. Moreover, it was shown that high anxiety before a medical procedure leads to increased postprocedural pain [Schupp et al.,2005], and that expectation of pain by itself may be an important factor in the development of chronic pain syndromes [Crombez et al.,1996]. Thus, elevated anxiety during pain expectancy, characterized by enhanced risk assessment or behavioral inhibition, may lead to a heightened pain response.

However, people differ in the way they attend to pain, and in the way they deal with pain expectancy [Snow‐Turek et al.,1996]. This variability may be attributed to certain innate traits which determine the a‐priori affective predisposition of the individual toward unpleasant stimuli in the environment. For example, the harm avoidance (HA) personality trait was proposed to reflect the individual's tendency to inhibit behaviors mediated by pessimistic worry or avoidance [Cloninger,1994]. Accordingly, HA was found to be correlated with individual sensitivity to painful stimuli and with a greater increase in the pain threshold in response to morphine [Granot,2005; Pud et al.,2004,2006]. HA reflects the individual's tendency toward inhibition of behaviors, such as pessimistic worry or avoidance of punishment [Cloninger,1994]. According to Cloninger's proposition, individuals with high HA score tend to be fearful and anticipate harm even under supportive circumstances and tend to be inhibited by unfamiliar situations. Accordingly, HA was shown to be associated with several psychiatric disorders, such as generalized anxiety disorder [Starcevic et al.,1996], PTSD [Richman and Frueh,1997], and depression [Farmer et al.,2003]. This might be related to the finding of a relation between HA and serotonergic functions in both healthy and psychiatric populations [Gerra et al.,2000; Hansenne and Ansseau1999; Zohar et al.,2003]. Hence, individual differences in HA personality trait may affect the way one reacts to pain expectancy and by that also change the subjective experience of pain.

A theoretical formulation regarding the neural mechanism involved in the processing of aversive stimuli was suggested by Gray and McNaughton [2000]. They postulated that the hippocampus and the amygdala, two core structures of the limbic system, are part of the brain's behavioral inhibition system (BIS), a set of structures that respond to warnings of punishment or nonreward, inhibiting ongoing behavior, and increasing arousal and attention when facing fear‐related stimuli. Gray and McNaughton [2000] proposed that the hippocampus sends amplification signals to the neural representation of an aversive event, and by that biases the organism toward a behavior that is adaptive to the worst possible outcome. The amygdala's role is to promote the arousal reaction of the BIS, in accordance with its critical role in the acquisition of fear responses [Davis and Shi2000; LeDoux 1996].

Indeed, accumulating imaging data suggest that activation in the hippocampus and the amygdala mediates both the anticipation and the experience of an aversive stimulus [Bechara et al.,1995; Bornhovd et al.,2002; Buchel et al.,1998; Nitschke et al.,2006; Price,2000]. For example, Ploghaus et al. [Ploghaus et al.,2001] have found an association between activity in the hippocampal network and exacerbation of pain by anxiety. Other studies have shown that the hippocampus is also recruited in anticipation of other aversive emotional stimuli, such as tones or pictures [Nitschke et al.,2006] and in contextual modulation of conditioned fear [Anagnostaras et al.,2001]. The amygdala, in addition to its role in the expression of a fear‐conditioned response [Phelps et al.,2001], is known to be active in conditions of uncertainty and expectancy processes [Bornhovd et al.,2002; Kahn et al.,2002] and is also related to the emotional processing of painful stimuli [Buchel et al.,1998; LaBar et al.,1998] including fear, stress, and expectation‐induced analgesia [Borszcz and Streltsov,2000; Fields,2000]. In addition to their involvement in aversive expectancy processes, several studies have shown that the amygdala and the hippocampus are associated with individual differences in anxiety‐related personality traits such as trait anxiety and HA trait [Barros‐Loscertales et al.,2006; Buchel et al.,2002; Etkin et al.,2004; Hariri et al.,2006; Iidaka et al.,2006]. However, these studies leave open the question regarding the association between personality traits and amygdala and hippocampus activity during anticipation to aversive stimuli. In addition, though several neuroimaging studies examined the role of trait differences in anticipating and processing of aversive events [Berns et al.,2006; Herwig et al.,2007; Ochsner et al.,2006], it is currently not known whether HA trait level is associated with brain responsiveness during anticipation of an aversive event such as pain.

The purpose of this study was to examine the contribution of the amygdala and hippocampus to individual differences during expectancy and experience of a painful stimulus. Expectancy was manipulated using a cue period, indicating that a painful stimulus is about to come. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) was employed to examine brain regional activity in relation to the cue (expectancy) period and the cued and uncued pain experience periods. To explore individual differences, the difference in the intensity rating of cued and uncued pain was calculated for each subject, representing the individual's sensitivity to pain expectancy [i.e., Pain Expectancy Sensitivity, (PES)]. In addition, each subject completed Cloninger's tridimensional personality questionnaire (TPQ), from which HA trait score was obtained. It was hypothesized that there would be a positive correlation between HA and PES, and that individual differences in HA and PES would be associated with increased activity in the hippocampus and the amygdala during pain expectancy and experience.

METHODS

Subjects

Twelve subjects (seven female and five male, 11 right‐handed), aged 20–31 years (mean, 24.5) participated in the study. Subjects suffering from pain, diseases causing potential neural damage (e.g., diabetes mellitus), systemic illnesses, skin lesions of any kind, head injury, and neurological or psychiatric disorders were excluded from the experiment. The study was approved by the Tel‐Aviv Sourasky Medical Center Ethics Committee and all participants gave written, informed consent after receiving a full explanation of the goals and protocols of the study.

Stimuli

Thermal stimuli were delivered using a Peltier‐based computerized thermal stimulator (TSA 2001, Medoc Ltd., Israel), with a 3 × 3 cm2 contact probe. The principles of the Peltier stimulator were described in detail elsewhere [Fruhstorfer et al.,1976; Verdugo and Ochoa,1992; Wilcox and Giesler1984]. Briefly, a passage of current through the Peltier element produces temperature changes at rates determined by an active feedback system. As soon as the target temperature is attained, probe temperature actively reverts to a preset adaptation temperature by passage of an inverse current. The adaptation (baseline) temperature was set to 32°C and the rate of temperature change was adjusted so that the stimulus duration (from beginning to end) was identical for all the intensities used. The thermal stimulator produces controlled thermal stimuli, such that their duration, intensity, and increasing rate can easily be modulated by the experimenter.

Pre‐Experiment Training and Assessment

Before the experiment, the temperature level to be used as painful stimulus for each subject was determined by slowly increasing the stimulus temperature with continuous monitoring of pain rating. Each subject rated 10 gradually ascending heat stimuli (38–52°C, 3‐s duration, ISI 24 s) applied to the left arm, according to the Magnitude Estimation Method [Gescheider1988]. The purpose of the pre‐experimental training session was to find for each subject a stimulus level of 5–6/10 (when 0 = “no pain” and 10 = “worst imaginable pain”), so that all subjects would receive the same subjectively painful stimulus during the functional imaging session.

Paradigm Design

The experiment design was modeled after a study by Ploghaus et al. [1999], which allows to distinguish the brain's response to pain with and without anticipation preceding it. Each subject received a sequence of 12 intense pain stimuli (rated as level of 5–6/10 in the training session) at random order. This individual pain intensity value ranged between 43c and 52c for the whole group. Half of the subjects received the stimuli to the left wrist and half to the right wrist. Six of the intense pain stimuli were preceded by a cue signal and six were not. The cue was the phrase “Get ready!” in red letters, presented on a screen which could be viewed through a mirror in the magnet bore, and preceded the onset of the thermal stimulation by an interval of 9–15 s. The intense pain, which was preceded by either expectancy period or by rest period, lasted 9 s. After the stimulus, participants rated the pain intensity of the hot stimulus on a 10‐point computerized visual analog scale (VAS), presented on the screen ahead of them for 15 s, using a response box with their free hand. The rating epoch was followed by a variable rest period (3–12 s), in which the subject viewed a fixation point on a gray background, until the end of the trial (see Fig. 1). The experiment consisted of 16 trials—six consisted of a painful stimulus preceded by a cue, six consisted of the same painful stimulus without a cue preceding it, and four consisted of a warm stimulus (control condition). The warm stimuli were two different nonpainful stimuli, one of them was preceded by a cue, and three were not (fixed for all subjects). Before the fMRI scan and after the training session, the subjects were told that they are about to receive several trials of heat stimulation, ranging from mild to very painful ones. They were also told that some of the stimuli would be preceded by a cue whereas some stimuli would not, and that after each stimulus they will be asked to rate its intensity using the response box. In fact, 75% of the stimuli given (12/16) were of the same intensity (which the subject rated at the training session as level of 5–6/10). This allowed us to examine whether pain expectancy causes two identical stimuli to be perceived as different.

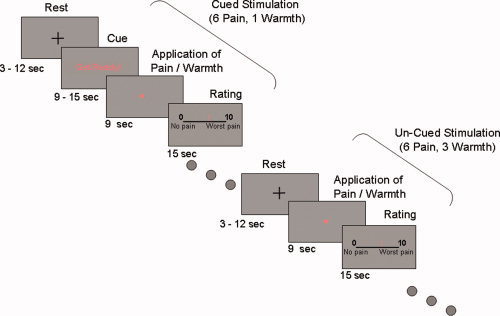

Figure 1.

Experimental paradigm. A sequence of twelve pain stimuli and four warm non painful stimuli, each lasted 9 s, were administrated to the wrist, at random order. Painful stimulus was defined by a pre‐experimental assessment of the individual pain magnitude sensitivity (see Methods). Six of the painful stimuli and one out of the four warm stimuli were preceded by a warning signal lasting between 9 and 15 s. After each stimulus, participants rated its intensity on a 10‐point computerized moving Visual Analog Scale (VAS), presented for 15 s independent of response time. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at www.interscience.wiley.com.]

Functional Imaging

MR data was acquired using a 3T GE Excite scanner (General Electric). All images were acquired using a standard quadrature head coil, and the subjects lay in the scanner with foam head restraint pads to minimize any movement associated with the painful stimulation. The scanning session included anatomical and functional imaging: T1 sequence (TR/TE = 440/8 ms, FOV = 20, matrix: 256 × 256) and 3D sequence spoiled gradient (SPGR) echo sequence, with high resolution 1‐mm slice thickness (FOV = 20 × 18, matrix: 256 × 256, TR/TE = 55/13 ms) was acquired for each subject. Functional T2*‐weighted images (TR = 3 s, TE = 30 ms, flip angle = 90°, FOV = 20, 64 × 64 matrix) were acquired (38 axial slices, thickness: 3 mm, gap: 0 mm, covering the entire brain) in runs of 130 images per slice.

PES Assessment

To explore the interindividual differences in the response to pain expectancy we calculated for each subject the PES index, defined as the difference between the averaged VAS rating of the six cued painful stimuli and the average VAS ratings of the six uncued painful stimuli.

Harm Avoidance Assessment

Harm avoidance was assessed using the Hebrew version of the Tridimensional Personality Questionnaire (TPQ): [Cloninger et al.,1991], a self‐report inventory based on Cloninger's personality model. This model suggests three temperamental dimensions which are defined in terms of individual differences in response to novelty, danger or punishment, and reward, each of which was hypothesized to be linked to a specific neurotransmitter system [Cloninger,1987]. HA is defined as a tendency to respond intensely to signals of aversive stimuli and to learn passively to avoid punishment and novelty, and is a frequently measured anxiety‐related personality trait [Cloninger et al.,1993]. Test‐retest reliability for the HA scale is 0.92 for the English version [Cloninger,1987], and 0.83 for the Hebrew version [Zohar et al., 2001].

Data Analysis

fMRI data was processed using a BrainVoyager 4.6 and QX software packages [Goebel et al.,1998].

For each subject, functional images were superimposed and incorporated into the 3D data sets through trilinear interpolation. The complete data set was transformed into Talairach space [Talairach and Tournoux,1988] with a voxel size of 3.125 × 3.125 × 3 mm3. Preprocessing of functional scans included high pass filtering to remove low‐frequency artifacts, motion correction and spatial smoothing (with 6‐mm Gaussian filter). 3D statistical parametric maps were calculated using a general linear model (GLM) which consisted of five conditions: three stimuli conditions (cued painful, uncued painful, and warm stimuli), an expectancy condition (the presentation of the cue signal), and a rating condition. The predictors for GLM were obtained by convolving the time course of the stimuli with a hemodynamic response function. In addition, to allow for T2* equilibration effects, the first six images of each functional scan were rejected. A three‐part analysis of the functional imaging data was performed. First, random effects multi subject general linear model (GLM) analyses were used to identify brain activation associated with pain (contrasting the two painful stimulus conditions versus baseline), and with pain expectancy (contrasting the expectancy condition versus baseline). After finding the overall main effect of pain and pain expectancy, we conducted a second whole brain analysis, with the PES and the HA parameters serving as covariates for each subject. This allowed the identification of the neural network related to interindividual differences in response to pain expectancy. Finally, a region of interest (ROI) analysis was applied to the amygdala and the hippocampus. Because the fMRI signal in these two sub‐cortical structures is not robust, especially during pain related paradigms, we decided to use a P value of 0.007, which was the highest value in which limbic activity was detected. In addition, based on the notion that falsely activated voxels should be randomly dispersed, we set a minimum cluster size of 50 voxels. It is unlikely that a cluster of 50 adjacent voxels would all be significant because of chance.

The ROIs were anatomically marked out of a general functional cluster that was obtained from the ANCOVA analysis. For each region, time courses were collected from all subjects and the beta weights were analyzed within each of the conditions, using Excel and SPSS software version 14.

RESULTS

Behavioral Results

The effect of pain expectancy on perceived pain intensity

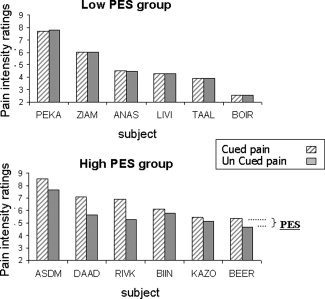

On average, on the basis of individual VAS scores, the cued painful stimuli were rated as more painful than uncued stimuli of identical intensity (Wilcoxon signed ranks test, two‐tailed, Z = −2.192; P < 0.05). The PES score of half of the subjects (n = 6, two males) was higher than the median PES (mean score = 0.93, range: 0.34–1.63, median score for the entire sample: 0.22), indicating high sensitivity to the expectancy manipulation (High PES group). The other half of the subjects (n = 6, three males) were indifferent to the expectancy manipulation, as reflected by very low PES scores (mean score = −0.01, range: −0.1 to 0.06, Low PES group, see Fig. 2). A paired sample t‐test confirmed that in the high PES subgroup the ratings of the cued pain stimuli were significantly different from the ratings of the uncued pain stimuli (t [5] = 3.99, P = 0.01), whereas in the low PES group the ratings of the cued and uncued pain stimuli were not significantly different (t [5] = 0.5, n.s.). Notably, the temperature of the painful stimulus in each participant's experiment (rated by that participant as pain intensity of 5–6/10 in the practice session) was not significantly different between the two PES groups (t [9] = 1.3, n.s.). Side of stimulated hand had no effect on the mean PES scores (t [10] = 0.38, P = 0.71, n.s.).

Figure 2.

Group characterization by pain expectancy sensitivity (PES): Bars indicate the perceived intensity of cued (striped) and uncued (full) painful stimuli in every subject. Grouping for high and low PES was based on whether an individual score was above or below the median value. PES, perceived intensity of cued pain minus perceived intensity of uncued pain.

Harm avoidance and response to pain

To examine whether PES scores were related to the level of HA, we classified subjects into two subgroups according to the group's median HA score. Thus, five subjects (three males) were classified as high‐HA individuals, and seven subjects (two males) were classified as low‐HA individuals. The two groups did not differ in the PES index score or in the average temperature of the painful stimuli (t[10] = 0.46, P = 0.66, n.s., and t[9] = 1.35, P = 0.21, n.s., respectively). HA scores were not related to the individual's subjective pain perception, as indicated by nonsignificant correlations between HA scores and the various measures of subjective pain (rating of the expected pain: r = 0.23; unexpected pain: r = 0.21, PES: r = 0.124, all n.s.). Nor were HA scores correlated with the temperature of the painful stimuli (r = 0.4, n.s.). It is unlikely that the lack of correlation is due to a restricted range of HA scores because the HA values in the sampled group (range, 1–20; mean, 11.8; SD, 5.5; median, 12) were very similar to those obtained in a different, larger, sample (n = 43) of healthy participants drawn from the same population (range, 2–32; mean, 12.3; SD, 6.3; median, 12).

fMRI Results

Whole brain analyses

Overall pain effect

Because of strong head movement‐related artifacts, two female subjects had to be excluded from the fMRI analysis, and were included only in the behavioral data analysis. Thus, the fMRI analysis included ten subjects (five males). First, to confirm that application of the thermal stimulus elicited a neural response in pain‐related areas, we compared brain response to the pain conditions (cued and uncued) with brain response to the baseline condition. A random effects GLM group analysis (q(FDR) < 0.05) revealed activation of the classic pain matrix, as well as activation that reflects motor preparation of the VAS ratings [Davis2000; Hsieh et al.,1996; Peyron et al.,1999; Rainville et al.,1997] including the anterior cingulate cortex (BA 24), bilateral insula and putamen, bilateral thalamus, bilateral precentral gyrus, bilateral medial frontal gyrus (BA 6), bilateral inferior parietal cortex, and left superior temporal gyrus (see Table I for details).

Table I.

Pain main effect: pain > baseline (random effects, q(FDR) < 0.05, minimum cluster size 50 voxels)

| ROI | Coordinate | # Voxels | Avg. P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X | Y | Z | |||

| Inferior parietal lobule BA40 R | 53 | −36 | 36 | 185 | 0.002 |

| Inferior parietal lobule BA40 L | −57 | −27 | 27 | 250 | 0.002 |

| Precentral gyrus BA6 R | 52 | 1 | 44 | 1,837 | 0.001 |

| Precentral gyrus BA6 L | −36 | −8 | 40 | 116 | 0.002 |

| Medial frontal gyrus BA6 L | −5 | 3 | 48 | 3,899 | 0.0007 |

| Medial frontal gyrus BA6 R | 5 | 3 | 51 | 2,935 | 0.0004 |

| Anterior cingulate cortex BA24 R | 3 | 2 | 36 | 1,896 | 0.001 |

| Anterior cingulate cortex BA24 L | −5 | 5 | 45 | 1,510 | 0.001 |

| Insula BA13 R | 38 | 13 | 11 | 7,794 | 0.0005 |

| Insula BA13 L | −36 | 17 | 16 | 9,515 | 0.0005 |

| Putamen R | 23 | 6 | 8 | 2,036 | 0.0005 |

| Putamen L | −23 | 11 | 5 | 3,044 | 0.0004 |

| Thalamus R | 13 | −10 | 11 | 1,248 | 0.001 |

| Thalamus L | −11 | −11 | 7 | 1,727 | 0.001 |

| Superior temporal gyrus BA42 L | −64 | −11 | 8 | 159 | 0.002 |

Expectancy and personality effects

To examine whether there is an overall main effect of expectancy, across all subjects, a whole brain analysis was conducted, with the expectancy condition as a positive predictor versus baseline. This analysis revealed increased activity in various visual areas, such as the inferior and middle occipital gyri, probably in response to the visual warning signal “Get Ready”.

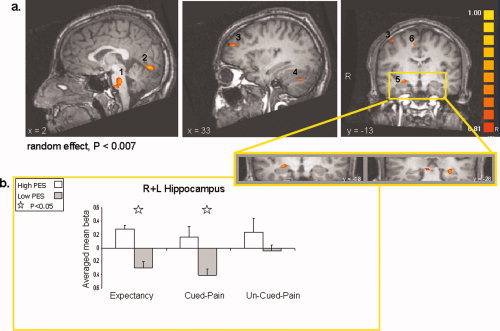

To examine the differences in the subjects response to the cue (as reflected by the rating of the intensity of cued pain versus that of uncued pain), we conducted a whole brain analysis with all conditions defined as positive predictors versus baseline, and the PES parameter serving as a covariate. This voxel‐based correlation analysis revealed distributed activation including the right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, right supplementary motor area (SMA), right postcentral gyrus, right superior temporal gyrus, right lingual gyrus, bilateral uncus and hippocampus, brainstem, and right cerebellum (Table II, Fig. 3a). This activity map reveals areas that are related to the individual's sensitivity to pain expectancy; the higher an individual's PES score, the more active these regions are.

Table II.

Whole brain analysis (all conditions vs. baseline) with PES as covariate (random effects, P < 0.007, minimum cluster size 50 voxels)

| ROI | Coordinate | # Voxels | Avg. P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X | Y | Z | |||

| Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex BA9/10 R | 33 | 45 | 26 | 167 | 0.005 |

| SMA BA6 R | 7 | −13 | 49 | 57 | 0.005 |

| Postcentral gyrus BA3 (S1) R | 50 | −20 | 56 | 392 | 0.004 |

| Lingual gyrus BA18 R | 1 | −76 | −7 | 850 | 0.003 |

| Uncus BA28 R | 26 | 4 | −26 | 163 | 0.004 |

| Uncus BA28 L | −29 | 3 | −25 | 64 | 0.006 |

| Hippocampus R | 25 | −16 | −11 | 358 | 0.003 |

| Hippocampus L | −27 | −29 | −7 | 135 | 0.005 |

| Brainstem (Pons) | 0 | −25 | −30 | 1392 | 0.003 |

| Cerebellum R | 33 | −61 | −29 | 127 | 0.004 |

Figure 3.

(a) Slice views obtained from a whole brain analysis, with individual pain expectancy sensitivity scores (PES) serving as covariate (random effects, P < 0.007, uncorrected). Selected regions that showed increased activation are indicated by numbers. 1, Pons; 2, Right Lingual gyrus; 3, Right Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex; 4, Right Cerebellum; 5, Bilateral Hippocampus; 6, Right Supplementary motor area. (b) Averaged beta weights obtained from region of interest analysis in the left and right hippocampus (shown in an enlarged view). Activation is denoted per PES group (high = white, low = black) and experimental condition period: expectancy, cued pain, and un‐cued pain. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at www.interscience.wiley.com.]

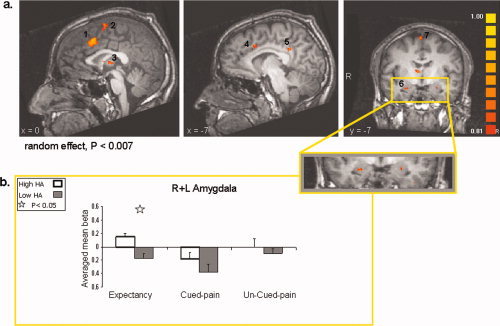

A similar whole‐brain correlation analysis was conducted with the individual's HA score as a covariate. Correlating whole brain activity with the HA scores demonstrated increased activation in the bilateral medial frontal gyrus, bilateral premotor cortex, right precentral gyrus, left anterior cingulate cortex, bilateral posterior cingulate cortex, left middle temporal gyrus, right thalamus, right lateral globus pallidus, and bilateral amygdala (Table III, Fig. 4a). This distributed activation reflects brain response to pain expectancy and pain processing while taking into account the variability in the individual's HA trait score. The higher the HA score, the more active these regions are.

Table III.

Whole brain analysis (all conditions vs. baseline) with HA as covariate (random effects, P < 0.007, minimum cluster size 50 voxels)

| ROI | Coordinate | # Voxels | Avg. P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X | Y | Z | |||

| Medial frontal gyrus BA6 R | 2 | 13 | 42 | 672 | 0.002 |

| Medial frontal gyrus BA6 L | −2 | 15 | 42 | 636 | 0.003 |

| Anterior cingulate gyrus BA32 L | −9 | 14 | 35 | 164 | 0.005 |

| Premotor cortex BA6 R+L | 2/−2 | −6 | 67 | 274 | 0.005 |

| Precentral gyrus BA4 R | 38 | −27 | 60 | 175 | 0.005 |

| Posterior cingulate cortex BA31 R | 9 | −54 | 29 | 146 | 0.005 |

| Posterior cingulate cortex BA31 L | −6 | −42 | 30 | 147 | 0.004 |

| Middle temporal gyrus BA39 L | −43 | −70 | 17 | 101 | 0.004 |

| Middle temporal gyrus BA21 L | −36 | 0 | −32 | 326 | 0.004 |

| Thalamus R | 6 | −7 | 11 | 210 | 0.004 |

| Lateral globus pallidus R | 23 | −19 | 1 | 152 | 0.004 |

| Amygdala R | 27 | −8 | −16 | 50 | 0.005 |

| Amygdala L | −24 | −7 | −15 | 72 | 0.005 |

Figure 4.

(a) Slice views obtained from a whole brain analysis, with individual harm avoidance (HA) scores serving as covariate (random effects, P < 0.007, uncorrected). Selected regions that showed increased activation are indicated by numbers. 1, Bilateral Medial frontal gyrus; 2, Bilateral Premotor cortex; 3, Right Thalamus; 4, Left Dorsal anterior cingulate cortex; 5, Left Posterior cingulate cortex; 6, Bilateral Amygdala; 7, Right Premotor cortex. (b) Averaged beta weights obtained from region of interest analysis in the left and right amygdala (shown in an enlarged view). Activation is denoted per HA group (high = white, low = black) and experimental condition period: expectancy, cued pain, and uncued pain. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at www.interscience.wiley.com.]

Region of Interest Analyses

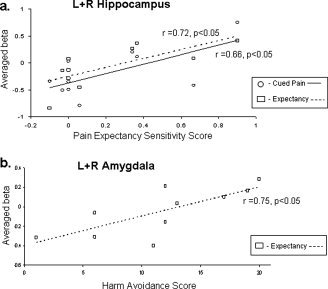

Following our a‐priori hypothesis, we looked at activations within regions of interest in the hippocampus and amygdala. To determine whether the hippocampus and the amygdala were associated with pain expectancy or with the actual response to the painful stimuli, we calculated the regional signal change during the different paradigm conditions (see Methods). Because in both the hippocampus and the amygdala no differences were found between the activity patterns of the right versus the left sides, we report here on the averaged activity in each ROI. Examining averaged right and left hippocampus activity for high and low‐PES sub‐groups revealed that the activity in the hippocampus differentiated between high and low PES groups only during the expectancy and cued pain conditions (t[8] = 3.36, P = 0.01, and t[8] = 2.45, P = 0.04, respectively), but not during the uncued pain condition (t[8] = 0.99, n.s., see Fig. 3b). We then explored the averaged signal change in the left and right amygdala for high‐HA and low‐HA sub‐groups, during the different paradigm conditions. We found that the difference in amygdala activity between the high and low‐HA subjects was significant only during the expectancy condition (t[8] = 2.62, P = 0.03) but not during the cued and uncued pain conditions (t[8] = 0.93, n.s. and t[8] = 0.63, n.s., respectively, see Fig. 4b). Notably, the high and low‐HA sub‐groups did not differ in hippocampus activity, and the high and low‐PES subgroups did not differ in amygdala activity, in any condition.

Taken together, these findings suggest that whereas hippocampal activity differs between the low and high‐PES subjects during the expectancy as well as during the cued pain condition, the amygdala appears to be more active among subjects with high HA scores only during the expectancy condition.

Correlating each subject's PES and HA scores with the activity in the hippocampus and amygdala during each condition revealed a similar result—a significant positive correlation was found between PES scores and hippocampus activity during the expectancy and cued pain conditions (right hippocampus: r = 0.74, P = 0.007, and r = 0.69, P = 0.01; left hippocampus: r = 0.64, P = 0.02, and r = 0.55, P = 0.05, respectively, see Fig. 5a). HA scores and amygdala activity revealed a significant positive correlation only during the expectancy condition (right amygdala: r = 0.64, P = 0.02; left amygdala: r = 0.78, P = 0.004, Fig. 5b).

Figure 5.

(a) Correlation between PES scores and averaged left and right hippocampus activity during the expectancy (squares) and cued pain (circles) periods. (b) Correlation between HA scores and averaged left and right amygdala activity during the expectancy period.

DISCUSSION

Our results demonstrate that pain expectancy increases the subjective painful experience of a noxious stimulus in some, but not all, individuals, and that this expectancy sensitivity is not related to HA trait score. At the level of brain activity, our results provide a distinction between the involvement of the amygdala and the hippocampus in the processing of pain expectancy. Although both structures are associated with individual differences in response to an upcoming aversive event, the hippocampus is related to PES, whereas the amygdala is associated with the anxiety‐related personality trait of HA. Specifically, during the period of pain expectancy participants with high‐harm avoidance score manifested more amygdala activity than subjects with low‐harm avoidance score. Conversely, subjects with high sensitivity to pain expectancy showed greater hippocampal activity than subjects with low sensitivity to pain expectancy, during both the expectancy and experience of pain.

The Effect of Expectancy on the Subjective Experience of Pain

On an average, pain expectancy caused a noxious stimulus to be experienced as more painful, relative to an unexpected noxious stimulus of the same intensity. This finding is in accordance with previous behavioral pain studies showing that expectation up‐regulates the perceived pain intensity [Fairhurst et al.,2007; Ploghaus et al.,2001]. This known “expectation effect” is attributed to an emotional state of elevated arousal and anxiety, evoked by the manipulated expectation of pain. In their review, Ploghaus et al. [2003] argue that expectation plays an important role in the modulation of acute and chronic pain, and claim that an important variable is the degree of certainty associated with the expectation. Accordingly, perception of expectation as either certain or uncertain can lead to different emotional and behavioral consequences. In our study, the cue indicated that a painful stimulus is imminent, but the subject did not know exactly how painful it would be. Thus, the expectation was of the “uncertain” type (uncertainty about pain intensity), which, according to Ploghaus et al. is usually associated with the emotional state of anxiety, and causes increase in the perceived intensity of the following pain (i.e. hyperalgesia).

Contrary to the studies cited above, several studies have shown that unpredictable aversive events can enhance anxiety, relative to predictable (cued) stimuli [Carlsson et al.,2006; Grillon et al.,2008]. For example, in a recent work by Grillon et al. [2008], panic disorder patients were found to be more vulnerable to unpredictability, showing greater anxiety when facing unpredictable (uncued) unpleasant stimuli. Similarly, in our study only half of the subjects showed enhanced sensitivity to the expectancy manipulation, rating the aversive stimuli that were preceded by a cue as more painful than the uncued aversive stimuli. Thus, for some individuals the cue results in sensitization, whereas others appear oblivious to the fact that unpleasantness is about to occur. This can be explained by personality differences which modulate the emotional reaction to the cues, thus influencing some—but not other—individuals' subjective experience of pain. Several human studies examined individual differences in responding to expectation of aversive stimuli [Berns et al.,2006; Herwig et al.,2007; Ochsner et al.,2006; Kumari et al.,2007; Pud et al.,2004]. In these studies the behavioral and neural responses to the expectancy state were found to be related to individual differences in trait factors such as neuroticism, dread, depressiveness, anxiety, and harm avoidance. However, contrary to our prediction, in our study the PES scores and HA trait scores were not correlated. This lack of correlation may be due to the small sample in our study. In contrast, it could be that although both PES and HA are related to anxiety processes during the expectancy of an upcoming aversive event, they are associated with a different aspect of this reaction. In accordance with this idea, it is reasonable to expect that these two measures would be associated with two different brain networks.

Neural Correlates of PES

At the neural level, the individual PES scores correlated with activation in cortical and subcortical regions such as the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, SMA, S1, superior temporal gyrus, lingual gyrus, cerebellum, the pons, and the hippocampus (see Table II). With regard to cortical regions, previous imaging studies demonstrated that increased activity in the SMA, S1, and the right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex is associated with attention‐related processes during pain experience [Coghill et al.,2003; Peyron et al.,2000; Porro et al.,2003; Tracey et al.,2005]. This is in line with a recent fMRI study which examined the neural correlates of waiting for a cutaneous electric shock, focusing on individual differences in the expressed fear (i.e. dread) while waiting for the next unpleasant stimulus [Berns et al.,2006]. It was shown that the level of “dread” was correlated with posterior elements of the pain matrix including the SI, SII, posterior insula, and the caudal ACC. These regions are known as the attention‐related division of the neural pain matrix, in contrast to the emotion‐related division (i.e., dorsal anterior cingulate cortex, anterior insula, amygdala) [Tracy and Mantyh2007]. Therefore, the authors suggested that the phenomenon of “dread” is driven by directing focus of attention toward the expected pain stimulus rather than by evoked anxiety. Following this idea, the cortical activation related to the PES scores might represent individual variability in the tendency to direct the focus of attention to the impending unpleasant event. We suggest that high‐PES individuals manifest an enhanced focus of attention toward the upcoming painful event and as a consequence have a heightened pain response. However, we propose that the heightened focus of attention is in fact related to enhanced anxiety in high‐PES subjects. High levels of anxiety are associated with increased attentional bias for affective information [Bar‐Haim et al.,2005]. Thus, pain expectancy may have elicited an amplified anxiety state which in turn caused heightened attention, resulting in a more vivid perception of the coming painful stimulus. The finding that the activity of the hippocampus but not the amygdala was correlated with increased PES scores is in accordance with this explanation. Indeed, several functional imaging studies demonstrated a role for the hippocampus in pain experience processing [Bingel et al.,2002; Peyron et al.,1999; Schneider et al.,2001]. The hippocampus role in pain processing has been attributed to its known involvement in context‐specific behavioral inhibition [Ploghaus et al.,2001], and in aversive conditioning [Buchel et al.,1999]. More specifically, it was proposed that the hippocampus is involved in the resolution of conflict between competing tendencies to approach or withdrawal behavior when facing an aversive stimulus [Gray and McNaugton,2000]. According to this model, the hippocampus outputs a signal that increases the weight of affectively negative information, thereby reducing or inhibiting the tendency to approach the goal. We suggest that in this study, when viewing the cue “Get Ready,” subjects with high PES score directed more attention to the upcoming painful stimulus, possibly as a result of a heightened evoked anxiety state. Interestingly, in our study the amplified reaction was correlated with greater hippocampal activity during expectancy as well as during the actual experiencing of the cued pain, probably affecting the pain experience itself. A possible limitation of our study is the lack of an independent anxiety measure during the experiment, such as a heart rate measure or a state‐anxiety questionnaire. However, the intensity rating of each painful stimulus immediately after it has been applied enables us to infer the emotional influence of the expectancy manipulation.

Neural Correlates of Harm‐Avoidance Trait

In a whole brain analysis we found that HA was correlated with distributed activation including the medial prefrontal cortex, premotor cortex, dorsal ACC, posterior cingulate cortex, the thalamus, and amygdala nuclei. Because HA reflects an inherent tendency of a heightened emotional response toward aversion and punishment [Cloninger,1987], it is not surprising that HA was found to be related to activity in these regions that are known to be involved in emotional processing and self‐related processing [Phillips et al.,2003]. To date, there are only few imaging studies that examined the neural correlates of the HA trait [Most et al.,2006; O'Gorman et al.,2006; Schweinhardt et al.,2009; Sugiura et al.,2000; Turner et al.,2003]. In line with our results, amygdala activity was found to be positively correlated with HA in two other studies [Iidaka et al.,2006; Most et al.,2006]. In addition to HA, amygdala activation is known to be correlated also with other anxiety‐related personality traits such as introversion and trait anxiety [Haas et al.,2007; Kumari et al.,2004; Mobbs et al.,2005]. This is in agreement with the amygdala's known involvement in the modulation of vigilance in the face of threat or fear‐related events in the environment [Whalen et al.,1998]. Our results suggest that individuals with high scores of HA, who are more fearful and inhibited, are more vigilant throughout the entire experiment, but especially when expecting pain, thus manifesting an enhanced emotional response toward the warning cues, possibly mediated via increased amygdala activity.

The Differential Role of the Hippocampus and the Amygdala in Processing Anxiety‐Provoking Stimuli

According to Gray and McNaugton's model [Gray and McNaugton2000], both the septo‐hippocampal system and the amygdala serve as the neural substrate for the Behavioral Inhibition System (BIS), a hypothetical physiological construct that mediates anxiety in animals and humans and is activated by warning signals of punishment or nonreward. In addition to the BIS, the theory postulates the existence of a behavioral approach system (BAS), which is activated by appetitive stimuli and mediates the emotion of anticipatory pleasure, and a fight‐flight‐freeze system (FFFS), which mediates fear and is activated by threatening stimuli that need not be faced, but can simply be avoided. The results of our study support Gray and McNaugton's model, by showing that pain expectancy is related to activity in the hippocampus and in the amygdala, albeit in relation to different aspects of aversion‐related behavior. Although the hippocampus is driven by the appraised painful value of a stimulus, the amygdala might be part of an innate tendency to cope with or avoid possible unpleasantness.

When interpreting our results one should consider a limitation of the design, in which the painful event is inescapable. The subject knows he is about to receive a painful stimulus but cannot do anything in order to avoid it. This may affect the emotional response during the anticipation period, leading to a state of anxiety rather than fear. Indeed, Gray and McNaughton claim that threats that must be faced are dealt with by the BIS, and threats that need not be faced are dealt with by the FFFS. Thus, by using unavoidable painful stimuli in our study, we probably probed the anxiety‐related mechanism of the BIS. In addition, the BIS is postulated to generate outputs related to attention and arousal, leading to orienting toward threat, as opposed to fear, which is associated with orientation away from threat [McNaughton and Corr2004]. It is for future studies to discriminate fear from anxiety mechanisms, possibly by manipulating escapable and inescapable aversive events.

We suggest that the activity of both the amygdala and the hippocampus is associated with increased arousal during pain expectancy. However, this increased arousal is also maintained during the actual experiencing of the expected pain only in the high PES subjects (possibly as a result of excessive involvement of the hippocampus in context learning), thus leading to a heightened response to the expected pain stimuli.

In contrast, subjects with high HA manifest more amygdala activity and increased arousal only during pain expectancy (possibly due to the amygdala's role in threat detection, during the initial stages of aversive conditioning), and hence is not associated with a heightened pain response.

In conclusion, the current fMRI study contributes to our understanding of the neural mechanisms underlying individual differences in processing anticipated threatening stimuli of pain. Our finding suggest that two core limbic structures—the amygdala and hippocampus—are related to different aspects of individual variability when anticipating aversive stimuli; innate vigilance and learned context, respectively. Further unveiling of the neural mechanism that underlies such inter individual differences during anticipation for an aversive stimulus and their relation to anxiety state, might contribute to the development of better therapeutic approaches to anxiety disorders.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institute for Psychobiology, core facility grant. We thank Valery Shternberg for her help in conducting the fMRI experiments, Dafna Ben‐Bashat for assistance with data acquisition, Roman Rozengurt for helping with the behavioral data analysis, and Oren Levin for technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- Anagnostaras SG,Gale GD,Fanselow MS ( 2001): Hippocampus and contextual fear conditioning: Recent controversies and advances. Hippocampus 11: 8–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar‐Haim Y,Lamy D,Glickman S ( 2005): Attentional bias in anxiety: A behavioral and ERP study. Brain Cogn 59: 11–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barros‐Loscertales A,Meseguer V,Sanjuan A,Belloch V,Parcet MA,Torrubia R,Avila C ( 2006): Behavioral Inhibition System activity is associated with increased amygdala and hippocampal gray matter volume: A voxel‐based morphometry study. Neuroimage 33: 1011–1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechara A,Tranel D,Damasio H,Adolphs R,Rockland C,Damasio AR ( 1995): Double dissociation of conditioning and declarative knowledge relative to the amygdala and hippocampus in humans. Science 269: 1115–1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berns GS,Chappelow J,Cekic M,Zink CF,Pagnoni G,Martin‐Skurski ME ( 2006): Neurobiological substrates of dread. Science 312: 754–758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bingel U,Quante M,Knab R,Bromm B,Weiller C,Buchel C ( 2002): Subcortical structures involved in pain processing: Evidence from single‐trial fMRI. Pain 99( 1/2): 313–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornhovd K,Quante M,Glauche V,Bromm B,Weiller C,Buchel C ( 2002): Painful stimuli evoke different stimulus‐response functions in the amygdala, prefrontal, insula and somatosensory cortex: A single‐trial fMRI study. Brain 125( Part 6): 1326–1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borszcz GS,Streltsov NG ( 2000): Amygdaloid‐thalamic interactions mediate the antinociceptive action of morphine microinjected into the periaqueductal gray. Behav Neurosci 114: 574–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchel C,Morris J,Dolan RJ,Friston KJ ( 1998): Brain systems mediating aversive conditioning: An event‐related fMRI study. Neuron 20: 947–957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchel C,Dolan RJ,Armony JL,Friston KJ ( 1999): Amygdala‐hippocampal involvement in human aversive trace conditioning revealed through event‐related functional magnetic resonance imaging. J Neurosci 19: 10869–10876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchel C,Bornhovd K,Quante M,Glauche V,Bromm B,Weiller C ( 2002): Dissociable neural responses related to pain intensity, stimulus intensity, and stimulus awareness within the anterior cingulate cortex: A parametric single‐trial laser functional magnetic resonance imaging study. J Neurosci 22: 970–976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlsson K,Andersson J,Petrovic P,Petersson KM,Ohman A,Ingvar M ( 2006): Predictability modulates the affective and sensory‐discriminative neural processing of pain. Neuroimage 32: 1804–1814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chua P,Krams M,Toni I,Passingham R,Dolan R ( 1999): A functional anatomy of anticipatory anxiety. Neuroimage 9( Part 1): 563–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloninger CR ( 1987): A systematic method for clinical description and classification of personality variants. A proposal. Arch Gen Psychiatry 44: 573–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloninger CR ( 1994): Temperament and personality. Curr Opin Neurobiol 4: 266–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloninger CR,Przybeck TR,Svrakic DM ( 1991): The Tridimensional Personality Questionnaire: U.S. normative data. Psychol Rep 69( Part 1): 1047–1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloninger CR,Svrakic DM,Przybeck TR ( 1993): A psychobiological model of temperament and character. Arch Gen Psychiatry 50: 975–990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coghill RC,McHaffie JG,Yen YF ( 2003): Neural correlates of interindividual differences in the subjective experience of pain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 8538–8542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crombez G,Vervaet L,Baeyens F,Lysens R,Eelen P ( 1996): Do pain expectancies cause pain in chronic low back patients? A clinical investigation. Behav Res Ther 34( 11/12): 919–925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis KD ( 2000): The neural circuitry of pain as explored with functional MRI. Neurol Res 22: 313–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis M ( 1992): The role of the amygdala in fear and anxiety. Annu Rev Neurosci 15: 353–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis M,Shi C ( 2000): The amygdale. Curr Biol 10: R131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etkin A,Klemenhagen KC,Dudman JT,Rogan MT,Hen R,Kandel ER,Hirsch J ( 2004): Individual differences in trait anxiety predict the response of the basolateral amygdala to unconsciously processed fearful faces. Neuron 44: 1043–1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairhurst M,Wiech K,Dunckley P,Tracey I ( 2007): Anticipatory brainstem activity predicts neural processing of pain in humans. Pain 128( 1/2): 101–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer A,Mahmood A,Redman K,Harris T,Sadler S,McGuffin P ( 2003): A sib‐pair study of the temperament and character inventory scales in major depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 60: 490–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fields HL ( 2000): Pain modulation: expectation, opioid analgesia and virtual pain. Prog Brain Res 122: 245–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fruhstorfer H,Lindblom U,Schmidt WC ( 1976): Method for quantitative estimation of thermal thresholds in patients. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 39: 1071–1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerra G,Zaimovic A,Timpano M,Zambelli U,Delsignore R,Brambilla F ( 2000): Neuroendocrine correlates of temperamental traits in humans. Psychoneuroendocrinology 25: 479–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gescheider GA ( 1988): Psychophysical scaling. Annu Rev Psychol 39: 169–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goebel R,Khorram‐Sefat D,Muckli L,Hacker H,Singer W ( 1998): The constructive nature of vision: Direct evidence from functional magnetic resonance imaging studies of apparent motion and motion imagery. Eur J Neurosci 10: 1563–1573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granot M ( 2005): Personality traits associated with perception of noxious stimuli in women with vulvar vestibulitis syndrome. J Pain 6: 168–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray JA,McNaughton NJ ( 2000): The neuropsychology of anxiety. Oxford: Oxford Medical Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Grillon C,Lissek S,Rabin S,McDowell D,Dvir S,Pine DS ( 2008): Increased anxiety during anticipation of unpredictable but not predictable aversive stimuli as a psychophysiologic marker of panic disorder. Am J Psychiatry 165: 898–904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas BW,Omura K,Constable RT,Canli T ( 2007): Emotional conflict and neuroticism: Personality‐dependent activation in the amygdala and subgenual anterior cingulate. Behav Neurosci 121: 249–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansenne M,Ansseau M ( 1999): Harm avoidance and serotonin. Biol Psychol 51: 77–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hariri AR,Drabant EM,Weinberger DR ( 2006): Imaging genetics: Perspectives from studies of genetically driven variation in serotonin function and corticolimbic affective processing. Biol Psychiatry 59: 888–897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herwig U,Kaffenberger T,Baumgartner T,Jancke L ( 2007): Neural correlates of a ‘pessimistic’ attitude when anticipating events of unknown emotional valence. Neuroimage 34: 848–858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh JC,Stahle‐Backdahl M,Hagermark O,Stone‐Elander S,Rosenquist G,Ingvar M ( 1996): Traumatic nociceptive pain activates the hypothalamus and the periaqueductal gray: A positron emission tomography study. Pain 64: 303–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iidaka T,Matsumoto A,Ozaki N,Suzuki T,Iwata N,Yamamoto Y,Okada T,Sadato N ( 2006): Volume of left amygdala subregion predicted temperamental trait of harm avoidance in female young subjects. A voxel‐based morphometry study. Brain Res 1125: 85–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn I,Yeshurun Y,Rotshtein P,Fried I,Ben‐Bashat D,Hendler T ( 2002): The role of the amygdala in signaling prospective outcome of choice. Neuron 33: 983–994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumari V,ffytche DH,Williams SC,Gray JA ( 2004): Personality predicts brain responses to cognitive demands. J Neurosci 24: 10636–10641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumari V,ffytche DH,Das M,Wilson GD,Goswami S,Sharma T ( 2007): Neuroticism and brain responses to anticipatory fear. Behav Neurosci 121: 643–652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBar KS,Gatenby JC,Gore JC,LeDoux JE,Phelps EA ( 1998): Human amygdala activation during conditioned fear acquisition and extinction: A mixed‐trial fMRI study. Neuron 20: 937–945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang PJ,Davis M,Ohman A ( 2000): Fear and anxiety: Animal models and human cognitive psychophysiology. J Affect Disord 61: 137–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal H,Brown D,Shacham S,Engquist G ( 1979): Effects of preparatory information about sensations, threat of pain, and attention on cold pressor distress. J Pers Soc Psychol 37: 688–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNaughton N,Corr PJ ( 2004): A two‐dimensional neuropsychology of defense: Fear/anxiety and defensive distance. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 28: 285–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mobbs D,Hagan CC,Azim E,Menon V,Reiss AL ( 2005): Personality predicts activity in reward and emotional regions associated with humor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 16502–16506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Most SB,Chun MM,Johnson MR,Kiehl KA ( 2006): Attentional modulation of the amygdala varies with personality. Neuroimage 31: 934–944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitschke JB,Sarinopoulos I,Mackiewicz KL,Schaefer HS,Davidson RJ ( 2006): Functional neuroanatomy of aversion and its anticipation. Neuroimage 29: 106–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Gorman RL,Kumari V,Williams SC,Zelaya FO,Connor SE,Alsop DC,Gray JA ( 2006): Personality factors correlate with regional cerebral perfusion. Neuroimage 31: 489–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochsner KN,Ludlow DH,Knierim K,Hanelin J,Ramachandran T,Glover GC,Mackey SC ( 2006): Neural correlates of individual differences in pain‐related fear and anxiety. Pain 120( 1/2): 69–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peyron R,Garcia‐Larrea L,Gregoire MC,Costes N,Convers P,Lavenne F,Mauguiere F,Michel D,Laurent B ( 1999): Haemodynamic brain responses to acute pain in humans: Sensory and attentional networks. Brain 122( Part 9): 1765–1780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peyron R,Laurent B,Garcia‐Larrea L ( 2000): Functional imaging of brain responses to pain. A review and meta‐analysis (2000). Neurophysiol Clin 30: 263–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelps EA,O'Connor KJ,Gatenby JC,Gore JC,Grillon C,Davis M ( 2001): Activation of the left amygdala to a cognitive representation of fear. Nat Neurosci 4: 437–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips ML,Drevets WC,Rauch SL,Lane R ( 2003): Neurobiology of emotion perception. I. The neural basis of normal emotion perception. Biol Psychiatry 54: 504–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ploghaus A,Tracey I,Gati JS,Clare S,Menon RS,Matthews PM,Rawlins JN ( 1999): Dissociating pain from its anticipation in the human brain. Science 284: 1979–1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ploghaus A,Narain C,Beckmann CF,Clare S,Bantick S,Wise R,Matthews PM,Rawlins JN,Tracey I ( 2001): Exacerbation of pain by anxiety is associated with activity in a hippocampal network. J Neurosci 21: 9896–9903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ploghaus A,Becerra L,Borras C,Borsook D ( 2003): Neural circuitry underlying pain modulation: Expectation, hypnosis, placebo. Trends Cogn Sci 7: 197–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porro CA,Cettolo V,Francescato MP,Baraldi P ( 2003): Functional activity mapping of the mesial hemispheric wall during anticipation of pain. Neuroimage 19: 1738–1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price DD ( 2000): Psychological and neural mechanisms of the affective dimension of pain. Science 288: 1769–1772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pud D,Eisenberg E,Sprecher E,Rogowski Z,Yarnitsky D ( 2004): The tridimensional personality theory and pain: Harm avoidance and reward dependence traits correlate with pain perception in healthy volunteers. Eur J Pain 8: 31–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pud D,Yarnitsky D,Sprecher E,Rogowski Z,Adler R,Eisenberg E ( 2006): Can personality traits and gender predict the response to morphine? An experimental cold pain study. Eur J Pain 10: 103–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rainville P,Duncan GH,Price DD,Carrier B,Bushnell MC ( 1997): Pain affect encoded in human anterior cingulate but not somatosensory cortex. Science 277: 968–971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiman EM,Fusselman MJ,Fox PT,Raichle ME ( 1989): Neuroanatomical correlates of anticipatory anxiety. Science 243( Part 1): 1071–1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richman H,Frueh BC ( 1997): Personality and PTSD. II. Personality assessment of PTSD‐diagnosed Vietnam veterans using the cloninger tridimensional personality questionnaire (TPQ). Depress Anxiety 6: 70–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider F,Habel U,Holthusen H,Kessler C,Posse S,Muller‐Gartner HW,Arndt JO ( 2001): Subjective ratings of pain correlate with subcortical‐limbic blood flow: An fMRI study. Neuropsychobiology 43: 175–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schupp CJ,Berbaum K,Berbaum M,Lang EV ( 2005): Pain and anxiety during interventional radiologic procedures: Effect of patients' state anxiety at baseline and modulation by nonpharmacologic analgesia adjuncts. J Vasc Interv Radiol 16: 1585–1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweinhardt P,Seminowicz DA,Jaeger E,Duncan GH,Bushnell MC ( 2009): The anatomy of the mesolimbic reward system: A link between personality and the placebo analgesic response. J Neurosci 29: 4882–4887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snow‐Turek AL,Norris MP,Tan G ( 1996): Active and passive coping strategies in chronic pain patients. Pain 64: 455–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starcevic V,Uhlenhuth EH,Fallon S,Pathak D ( 1996): Personality dimensions in panic disorder and generalized anxiety disorder. J Affect Disord 37( 2/3): 75–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staub E,Tursky B,Schwartz GE ( 1971): Self‐control and predictability: Their effects on reactions to aversive stimulation. J Pers Soc Psychol 18: 157–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiura M,Kawashima R,Nakagawa M,Okada K,Sato T,Goto R,Sato K,Ono S,Schormann T,Zilles K,Fukud H ( 2000): Correlation between human personality and neural activity in cerebral cortex. Neuroimage 11( Part 1): 541–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talairach J,Tournoux P ( 1988): Co‐planar Stereotaxic Atlas of the Human Brain. New York: Thieme Tracey I (2005): Nociceptive processing in the human brain. Curr Opin Neurobiol 15: 478–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tracy I,Mantyh PW ( 2007): the cerebelar signature for pain perception and its modultion. Neuron 55: 377–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner RM,Hudson IL,Butler PH,Joyce PR ( 2003): Brain function and personality in normal males: A SPECT study using statistical parametric mapping. Neuroimage 19: 1145–1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdugo R,Ochoa JL ( 1992): Quantitative somatosensory thermotest. A key method for functional evaluation of small calibre afferent channels. Brain 115( Part 3): 893–913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whalen PJ,Rauch SL,Etcoff NL,McInerney SC,Lee MB,Jenike MA ( 1998): Masked presentations of emotional facial expressions modulate amygdala activity without explicit knowledge. J Neurosci 18: 411–418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox GL,Giesler GJ Jr ( 1984): An instrument using a multiple layer Peltier device to change skin temperature rapidly. Brain Res Bull 12: 143–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zohar AH,Dina C,Rosolio N,Osher Y,Gritsenko I,Bachner‐Melman R,Benjamin J,Belmaker RH,Ebstein RP ( 2003): Tridimensional personality questionnaire trait of harm avoidance (anxiety proneness) is linked to a locus on chromosome 8p21. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet B 117: 66–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]