Abstract

Objective:

We aimed to investigate differences in fractional anisotropy (FA) between primary lateral sclerosis (PLS) and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and the relationship between FA and disease progression using tract‐based spatial statistics (TBSS).

Methods:

Two scanners at two different sites were used. Differences in FA between ALS patients and controls scanned in London were investigated. From the results of this analysis, brain regions were selected to test for (i) differences in FA between controls, patients with ALS and patients with PLS scanned in Oxford and (ii) the relationship between FA and disease progression rate in the Oxford patient groups.

Results:

London ALS patients showed a lower FA than controls in several brain regions. Oxford patients with PLS showed a lower FA than ALS patients and than controls in the body of the corpus callosum and in the white matter adjacent to the right primary motor cortex (PMC), while ALS patients showed reduced FA compared with PLS patients in the white matter adjacent to the superior frontal gyrus. Significant correlations were found between disease progression rate and (i) FA in the white matter adjacent to the PMC in PLS, and (ii) FA along the cortico‐spinal tract and in the body of the corpus callosum in ALS.

Conclusions:

We described significant FA changes between PLS and ALS, suggesting that these two presentations of motor neuron disease show different features. The significant correlation between FA and disease progression rate in PLS suggests the tissue damage reflected in FA changes contributes to the disease progression rate. Hum Brain Mapp, 2009. © 2008 Wiley‐Liss, Inc.

Keywords: MRI, diffusion, ALS

INTRODUCTION

One of the most informative measures derived from DTI is fractional anisotropy (FA), which reflects the degree to which the diffusion tensor is ‘anisotropic’. High FA is found in the brain regions which contain white matter fibres, along which the water molecules diffuse more freely [Pierpaoli and Basser, 1996]. A decrease in FA, which is quantified by DTI, has been shown to be related to axonal fibre degeneration and myelin breakdown [Beaulieu et al., 1996]. Several studies have investigated changes in FA between patients with neurological conditions and healthy controls, with the aim of improving diagnosis and monitoring disease progression [Horsfield and Jones, 2002]. We focus our study on patients with motor neuron disease, such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), which presents with a combination of upper motor neuron and lower motor neuron signs [Rowland and Shneider, 2001], and primary lateral sclerosis (PLS), which is characterised by upper motor neuron involvement without lower motor neuron signs.

Previous studies that employed a voxel‐based approach to investigate differences in FA between ALS patients and controls, reported that patients show a decrease in FA not only in the cortico‐spinal tract (CST), but also in the regions outside the main motor cortices and the CST [Sach et al., 2004; Sage et al., 2007]. However, these findings were not confirmed by other authors [Abe et al., 2004]. These previous investigations used a voxelwise statistical analysis, which consists of registering each subject's FA image into a standard space, and then performing a voxelwise comparison to localise FA differences in patients and controls. Although this type of approach, which is a development of voxel‐based morphometry (VBM), was initially created to find changes in grey matter density in T1 weighted images of healthy subjects [Ashburner and Friston, 2000], it has been widely used to investigate FA changes in ALS [Agosta et al., 2007; Sage et al., 2007]. The technique has limitations because it is dependent on the goodness of the registration algorithm and on the choice of the spatial smoothing [Jones et al., 2005]. In this article, we localise FA pathological changes in ALS and PLS using a novel method, called tract‐based spatial statistics (TBSS) (http://www.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl), which aims to overcome the current limitations of the standard VBM‐style analyses [Smith et al., 2006].

Primary lateral sclerosis (PLS) is considered to be part of the spectrum of motor neuron diseases and is characterised by isolated upper motor neuron involvement. However, the distinction between ALS and PLS is not so straightforward, since neuronal loss in the anterior horn has been widely reported in both conditions [Bruyn et al., 1995; Hainfellner et al., 1995; Hudson et al., 1993; Pringle et al., 1992]. The application of non‐conventional MRI techniques to patients with PLS has so far been very limited [Wang and Melhem, 2005], and a voxel‐based analysis of patients with PLS has not been reported. An important question is whether there are differences in FA within and outside the CST which distinguish patients with ALS from patients with PLS. This has clinical implications and, if confirmed, would suggest that DTI might be a useful tool to detect the distinct pathological features of these two presentations of motor neuron disease.

A key question is whether there is a relationship between the rate of disease progression and FA in either presentations of motor neuron disease. There is evidence of a significant correlation between FA with measures of disease severity in patients with ALS [Ellis et al., 1999]. Recent studies have reported significant correlations in ALS patients between disease severity and FA in the cranial parts of the CST using SPM2 [Sage et al., 2007], in the cerebral peduncle using TBSS [Smith et al., 2006], and in the internal capsule using regions of interest in the tractography‐derived tracts [Wang et al., 2006]. However, not all studies have confirmed such correlations [Ciccarelli et al., 2006; Hong et al., 2004; Toosy et al., 2003]. To date, the relationship between FA and disease severity in patients with PLS has not been investigated. Therefore, in this study we explored the relationship between FA and disease progression rate, which is an index that takes into account the disease duration in addition to the disease severity, in both the ALS and PLS patient groups.

Thus, in this study we used the novel TBSS approach and tested whether FA was reduced across the whole brain in patients with ALS compared to controls scanned in London on a 1.5‐Tesla scanner. From this analysis, we obtained brain regions in which differences in FA between patients with ALS and patients with PLS, and between these patient groups and controls scanned in Oxford on a 3‐T scanner, were investigated. We also assessed whether there were significant correlations between the FA of these brain regions and disease progression rate in both the patient groups scanned in Oxford.

METHODS

Brief Summary of the Study Design and Analysis

Two cohorts of patients were studied at two different sites. Patients with ALS and healthy subjects were recruited and scanned in London on a 1.5‐T scanner. Differences in FA between patients and healthy controls were investigated using TBSS. The significant results of the group comparisons were used to define brain regions affected by white matter pathology. These regions were then manually outlined on the images of subjects scanned in Oxford on a 3‐T scanner and used to test for differences in white matter FA (1) between patients with ALS and controls, (2) between patients with PLS and controls, and (3) between patients with ALS and patients with PLS. Furthermore, the same regions were used to explore the relationship between FA and the rate of disease progression in both patient groups scanned in Oxford.

Subjects

Subjects studied in London

Thirteen patients (mean age 54 years, SD 13, 12 men and 1 woman) with probable or definite ALS [Brooks et al., 2000], who attended the Motor Neuron Disease clinic at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London were studied. Their mean ALS functional rating scale (ALSFRS) [1996] was 31 (SD 5), and their mean disease duration was 21 months (SD 16). The mean rate of the disease progression, calculated according to a formula previously published [Ellis et al., 1999], was 0.72 units/month (SD 0.68). More details on patients' characteristics are given in our previous tractography article [Ciccarelli et al., 2006].

Twenty non‐age matched healthy controls (mean age 39.1 years, SD 10.7, 16 men and 4 women), were also studied.

Subjects studied in Oxford

Thirteen patients (mean age 56.8, SD 7, 11 men and 2 women) with probable or definite ALS were studied. Their mean ALSFRS was 31.4 (SD 6.2), and their mean disease duration was 24.8 months (SD 22.4). Their mean rate of disease progression was 0.56 units/month (SD 0.8).

Six patients (mean age 58.5, SD 5.8, all men) with PLS (according to the diagnostic criteria proposed by Pringle [Pringle et al., 1992] incorporating Santa Clara consensus [McBride, 2004]) were also recruited. Their mean ALSFRS was 31.5 (SD 5.7) and their mean disease duration was 88.7 months (SD 80.8). Their mean rate of disease progression was 0.17 units/month (SD 0.11). As expected by the diagnostic criteria, there was a significant difference in the disease duration between ALS and PLS patients (P = 0.001), while the disease progression and the ALSFRS did not differ between the two groups (using Mann‐Whitney U test). Twenty‐one age‐matched controls (mean age 54.6, SD 11.9, 13 men and 8 women) were studied.

All subjects attended the Motor Neuron Disease clinic at the John Radcliffe Hospital in Oxford and gave informed, written consent before the study, which was approved by the local research ethics committees.

MRI Protocol

MRI protocol in London

All subjects were imaged on a Signa Echospeed‐GE 1.5‐T scanner with maximum gradient strength of 22 mT m−1. The diffusion protocol consisted of a single shot DW‐EPI sequence with an echo time (TE) of 96 ms. The diffusion acquisition parameters were: FOV 220 × 220 mm2, matrix 96 × 96 reconstructed as 128 × 128, giving a final in‐plane resolution of 1.7 × 1.7 mm2, 60 contiguous axial slices, 2.3‐mm slice thickness. The diffusion gradients were applied along 54 directions (diffusion times of δ = 32 ms and Δ = 40 ms, maximum b‐factor b = 1,150 s mm−2) [Jones et al., 1999]. Six diffusion‐weighted volumes (b = 300 s mm−2) (the directions used were spatially distributed on a hemisphere according to [Jones et al., 1999]) and six volumes with no diffusion weighting were acquired. Cardiac gating was used to reduce motion artefacts due to pulsation of blood and cerebro‐spinal fluid [Wheeler‐Kingshott et al., 2002]. The diffusion data acquisition time was about 25 min. (depending on heart rate). Correction of eddy‐current distortions in DW‐EPI was performed using a two‐dimensional image registration technique [Symms, 1997].

MRI protocol in Oxford

All imaging in Oxford was performed on a Varian‐Siemens 3‐T scanner with maximum gradient strength of 22 mT m−1. The diffusion protocol consisted of a double refocused spin echo sequence [Reese et al., 2003] with a TE of 106 ms. The diffusion acquisition parameters were: FOV 240 × 240, matrix 62 × 96 reconstructed as 128 × 128, giving a final in‐plane resolution of 1.875 × 1.875 mm2, 60 contiguous axial slices, 2.5 mm slice thickness. The diffusion gradients were applied along 60 directions (diffusion times of δ = 14 ms and Δ = 53 ms, maximum b‐factor b = 1,000 s mm−2) [Jones et al., 1999] and three volumes with no diffusion weighting were acquired. Cardiac gating was used to minimise pulsatile motion artefacts [Nunes et al., 2005] and the acquisition time was about 20 min. (depending on heart rate). Two series were acquired in each patient and corrected for eddy‐current distortions and head motion using an affine registration to the reference image [Jenkinson and Smith, 2001]. Data from the two corrected datasets were then averaged to improve the SNR (as demonstrated by [Jones, 2004]). The Signal‐to‐Noise ratio (SNR) was calculated on the b0 images of a randomly chosen control by multiplying the mean signal intensity of a region of interest inside the brain (located within the sub‐cortical white matter) by 0.66, and dividing the result by the SD of a region of interest outside the brain (and away from any imaging artefacts) [Henkelman, 1985]. It was equal to 15.

TBSS

On the diffusion weighted images of the London and Oxford subjects the diffusion tensor was calculated on a voxel‐by‐voxel basis [Basser et al., 1994], and fractional anisotropy (FA) maps were obtained. TBSS (http://www.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl/tbss) was employed as described in detail in a previous article [Smith et al., 2006]. The main steps of the analysis were as follows:

Alignment of FA images to standard space

Each individual FA image was aligned into 1 × 1 × 1 mm MNI152 standard space in three steps:

-

1

by identifying a single subject FA ‘target’ image, to which every FA image was non‐linearly aligned,

-

2

by aligning the target image to the MNI152 standard space using affine transformation, and

-

3

by transforming each individual FA image into the MNI152 standard space using both the non‐linear and affine transformations estimated in the previous steps [Rueckert et al., 1999].

Creating the mean FA image and its skeleton

The transformed individual FA images were averaged to create a mean FA image. This mean image was then ‘thinned’ to create a FA skeleton, which represents the tracts that are ‘common’ to all subjects. Finally, this FA skeleton was threshold (using the voxelwise mean FA across subjects), to discard areas in which a good tract correspondence between subjects was not achieved, and to exclude all voxels which are primarily GM or CSF in the majority of subjects. The aim of this thresholding is to define the set of voxels to be included in the voxel‐wise cross‐subject statistics. Since the chosen threshold is specific to the skeletonised mean FA in each given study, it can vary between studies, although a value of FA between 0.2 and 0.3 has been found to be successful [Smith et al., 2006]. The threshold that we used was FA = 0.3 for the London cohort, and FA = 0.25 for the Oxford cohort.

Projecting individual FA maps onto the skeleton

Each subject's aligned FA image was in turn projected onto the mean FA skeleton, using the maximum FA value in a search perpendicular to the skeleton. This step resulted in a 4D image (‘skeletonised’), which has the subject ID as a fourth dimension; this image was then used in the voxel‐based statistics across subjects, as explained below.

Statistics and correction for multiple comparisons

-

1

In the London cohort: We investigated differences in FA between patients and controls using a two sample t‐test, after regressing out the effect of age (since the two groups were not age‐matched). Two contrasts, i.e., patients greater than controls and controls greater than patients, were estimated. The resultant statistical maps were threshold at P < 0.05 corrected at cluster level for multiple comparisons by using a permutation‐based approach [Nichols and Holmes, 2002]. In particular, a cluster‐forming threshold t > 1 was used, and the null distribution of maximum values (across the image) of the test statistic was estimated. The FA value of the significant voxels obtained with TBSS was extracted manually in each subject. The mean FA of these regions within the patient and control group was then calculated using SPSS 11.5 for Windows. For bilateral regions, e.g., the cerebral peduncle, the value of FA from the left and right side was averaged.

-

2

In the Oxford cohort: From the results of the comparison between London patients and controls, we defined regions of white matter affected by ALS. These regions were located along the CST and were as follows: (1) the cerebral peduncle, (2) the internal capsule, (3) the corona radiata, and (4) the white matter adjacent to the primary motor cortex (PMC). We also selected two additional regions outside the CST: (1) the body of the corpus callosum, since the bilateral primary motor cortices are connected by fibres that pass through the body of the corpus callosum, and collaterals of the CST pass through this callosal region, and (2) the white matter adjacent to the superior frontal gyrus, since the pre‐frontal region involvement in ALS is well known. Furthermore, these two regions have been reported to show significant differences between patients and controls in a previous VBM study [Sach et al., 2004]. These six pre‐selected regions of interest were then manually outlined on the basis of anatomical knowledge on the mean FA image of the Oxford cohort. They were placed bilaterally, with the exception of the body of the corpus callosum, and then masked with the mean FA skeleton to obtain the final regions of interest that were used in the following analysis.

Difference in FA between controls, patients with ALS, and patients with PLS.

The mean FA value (and the SD) of the regions manually drawn was obtained for each subject scanned in Oxford using SPSS 11.5 for Windows. For bilateral regions, e.g., the cerebral peduncle, the value of FA from the left and right side was averaged.

We tested the hypotheses that there were significant differences in FA (1) between patients with ALS and controls, (2) between patients with PLS and controls, and (3) between patients with ALS and patients with PLS. Since these two groups of patients were aged‐matched, and each group of patient was age‐matched to the control group, age was not included in the model. Four contrasts, i.e., ALS patients lower than controls, PLS patients lower than controls, PLS patients lower than ALS patients, and ALS lower than PLS, were estimated. Correction for multiple comparisons at cluster level (t > 1, P < 0.05) was performed within the regions of interest described earlier by using permutation‐based inference [Nichols and Holmes, 2002]. This multiple comparisons method uses permutation‐based (nonparametric) inference [Nichols and Holmes, 2002], and does not assume a random Gaussian field, therefore we consider it to be a valid approach. The mean FA value of the supra‐threshold voxels (i.e., voxels with associated P value <0.05) within regions of interest in each subject of the three groups (i.e., controls, patients with ALS, and patients with PLS) was calculated.

To compare the skeletonised mean FA between patients with ALS, patients with PLS and controls, the Kruskal‐Wallis test was used.

Relationship between FA and disease progression rate in PLS and ALS.

We also tested whether there was an inverse relationship between FA and the rate of disease progression in each patient group (i.e., ALS and PLS), by using a linear regression analysis. Correction for multiple comparisons at cluster level (t > 1, P < 0.05) within the regions of interest listed above was performed by using permutation‐based inference. The R‐square (Rsq), the mean FA, and the plot of the mean FA of the supra‐threshold voxels (P < 0.05) within regions of interest against the rate of disease progression, were obtained using SPSS 11.5 for Windows. It is important to note that these supra‐threshold voxels can differ from those derived from the comparisons of FA between groups, although they are located within the same regions of interest. Therefore the mean FA value of regions in which there was a correlation between FA and disease progression rate can be slightly different (i) from the mean FA of regions in which significant differences in FA between groups were found, and (ii) from the mean FA of the whole regions of interest.

RESULTS

Findings in the London Cohort

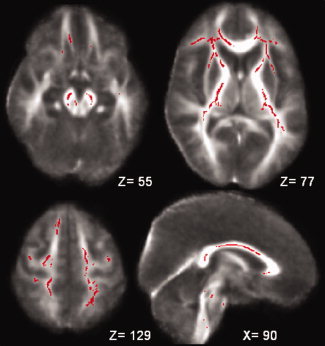

Patients had a significantly lower FA compared with controls in several regions within and outside the CST (all P values < 0.05). In particular, lower FA was found bilaterally in the cerebral peduncle, in the posterior limb of the internal capsule, in the corona radiata and in the white matter adjacent to the pre‐central gyrus (or PMC, Brodmann area 4) (Fig. 1, Table I). Patients also showed a significantly lower FA in the corpus callosum (including the body, genu, and splenium), in the anterior limbs of the internal capsule, in the external capsules, in the white matter adjacent to the right superior frontal gyrus (Brodmann area 8, 9, 10), the bilateral pre‐motor cortex (Brodmann area 6), the bilateral inferior and medial frontal gyrus (Brodmann area 45, 46, and 47), and the bilateral post‐central gyrus (or primary sensory cortex) (Fig. 1, Table I).

Figure 1.

Red voxels show the regions within and outside the CST where the FA was significantly reduced in patients with ALS when compared to controls scanned in London (all P values < 0.05, corrected at cluster level). These regions are: the cerebral peduncles (a), the anterior and posterior limb of the internal capsule, the external capsule, the white matter adjacent to the bilateral inferior frontal gyrus (b), the corona radiata, the white matter adjacent to the bilateral pre‐central gyrus (or primary motor cortex), the right superior frontal gyrus, the bilateral pre‐motor cortex and the post‐central gyrus (or primary sensory cortex) (c), and the corpus callosum (d). The background image is the mean FA and the coordinates are in MNI152 space.

Table I.

Mean FA (and SD) of clusters where there were significant differences between London patients and controls

| Regions | London ALS patients | London controls |

|---|---|---|

| Cerebral peduncle | 0.66 (0.06) | 0.72 (0.04) |

| Post. limb of internal capsule | 0.65 (0.05) | 0.70 (0.03) |

| Corona radiata | 0.60 (0.05) | 0.63 (0.03) |

| WM matter adjacent to the pre‐central gyrus | 0.40 (0.04) | 0.48 (0.03) |

| Body of corpus callosum | 0.66 (0.06) | 0.74 (0.04) |

| Genu of corpus callosum | 0.63 (0.04) | 0.68 (0.03) |

| Splenium of corpus callosum | 0.66 (0.08) | 0.75 (0.03) |

| Ant. limb of internal capsule | 0.53 (0.03) | 0.58 (0.02) |

| External capsule | 0.37 (0.05) | 0.42 (0.03) |

| WM adjacent to the right superior frontal gyrus | 0.43 (0.02) | 0.49 (0.03) |

| WM adjacent to the bilateral pre‐motor cortex | 0.46 (0.04) | 0.52 (0.03) |

| WM adjacent to the inferior frontal gyrus | 0.44 (0.06) | 0.51 (0.04) |

| WM adjacent to the middle frontal gyrus | 0.37 (0.03) | 0.41 (0.09) |

| WM adjacent to the post‐central gyrus | 0.39 (0.1) | 0.48 (0.03) |

WM = white matter.

Findings in the Oxford Cohort

Difference in FA between patients with ALS, patients with PLS, and controls

The FA values of the regions which were tested for significant differences in FA between the three subject groups are given in Table II.

Table 2.

Mean FA (and SD) of regions under investigation in the Oxford patient groups and controls

| Regions | Oxford PLS patients | Oxford ALS patients | Oxford controls |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cerebral peduncle | 0.62 (0.06) | 0.62 (0.07) | 0.63 (0.07) |

| Post. limb of internal capsule | 0.68 (0.05) | 0.66 (0.07) | 0.68 (0.05) |

| Corona radiata | 0.64 (0.06) | 0.63 (0.05) | 0.63 (0.05) |

| WM matter adjacent to the pre‐central gyrus | 0.39 (0.04) | 0.43 (0.04) | 0.47 (0.04) |

| Body of corpus callosum | 0.52 (0.06) | 0.60 (0.07) | 0.64 (0.08) |

| WM adjacent to the right superior frontal gyrus | 0.43 (0.04) | 0.43 (0.06) | 0.44 (0.07) |

WM = white matter.

Note: for bilateral regions, a mean of the left and right region was given.

We found that patients with ALS showed lower FA than controls in the white matter adjacent to the left pre‐central gyrus (ALS: mean FA 0.43 (SD 0.04) vs. controls: mean FA 0.50 (SD 0.06), P = 0.038).

Patients with PLS showed lower FA than controls in the three following areas: (1) the white matter adjacent to the left pre‐central gyrus (PLS: mean FA 0.39 (SD 0.07) vs. controls: mean FA 0.49 (SD 0.06) P = 0.009); (2) the white matter adjacent to the right pre‐central gyrus (or PMC) (PLS: mean FA 0.35 (SD 0.04), vs. controls 0.46 (SD 0.04), P = 0.01); (3) the body of the corpus callosum (PLS: mean FA 0.52 (SD 0.06) vs. controls: mean FA 0.63 (SD 0.08), P = 0.006).

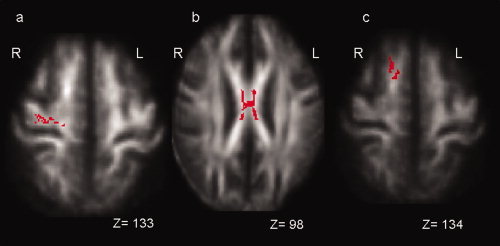

There were also significant differences in FA between patients with ALS and patients with PLS. Patients with ALS showed a significantly lower FA than patients with PLS in the white matter adjacent to the right superior frontal gyrus (ALS: mean FA 0.43 (SD 0.07) vs. PLS: mean FA 0.55 (SD 0.07); P = 0.014) (see Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Red voxels show the regions where there is a significant difference in FA between patients with PLS and patients with ALS scanned in Oxford (P < 0.05, corrected at cluster level within regions of interest). Patients with PLS showed lower FA than ALS patients in the white matter adjacent to the right primary motor cortex (P = 0.029) (a) and the body of the corpus callosum (P = 0.036) (b). Patients with ALS showed reduced FA than PLS patients in the white matter adjacent to the right superior frontal gyrus (P = 0.014) (c). The background image is the mean FA and the coordinates are in MNI152 space. Left = L and Right = R.

On the other hand, PLS patients showed a significantly lower FA than ALS patients in the white matter adjacent to the right pre‐central gyrus (or PMC) (PLS: mean FA 0.34 (SD 0.04) vs. ALS: mean FA 0.43 (SD 0.06); P = 0.029) and in the body of the corpus callosum (PLS: mean FA 0.50 (SD 0.07) vs. ALS: mean FA 0.59 (SD 0.08); P = 0.036) (see Fig. 2).

There was no significant difference in the mean skeletonised FA between controls (mean FA 0.45, SD 0.04), patients with PLS (mean FA 0.43, SD 0.02), and patients with ALS (mean FA 0.44, (SD 0.04)).

Relationship between FA and disease progression rate in PLS and ALS

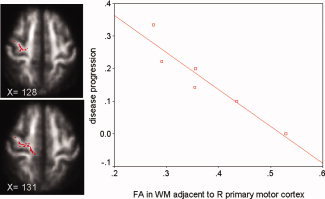

In patients with PLS, there was an inverse relationship between the FA of the white matter adjacent to the right pre‐central gyrus and the rate of disease progression (P = 0.05, Rsq 0.89, mean FA 0.38 (SD 0.09)) (see Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Voxels in red showed the white matter adjacent to the right primary motor cortex in which FA correlates with the disease progression rate in patients with PLS scanned in Oxford. The background image is the mean FA and the coordinate is in MNI152 space. The plot of the FA of this region versus the rate of disease progression (units/month) in 6 patients with PLS is displayed on the right side of the figure.

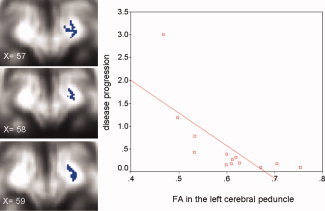

In patients with ALS, we found that the rate of disease progression correlated with FA in the following regions: (i) left cerebral peduncle (P = 0.0005, Rsq 0.52, mean FA = 0.60 (SD 0.08)) (see Fig. 4), (ii) right posterior limb of the internal capsule (P = 0.03, Rsq 0.3, mean FA 0.65 (SD 0.08)), (iii) right corona radiata (P = 0.008, Rsq 0.53, mean FA 0.53 (SD 0.05)), (iv) white matter adjacent to the right pre‐central gyrus (P = 0.02, Rsq 0.81, mean FA 0.44 (SD 0.06)), (v) body of the corpus callosum (P = 0.05, Rsq 0.31, mean FA 0.59 (SD 0.08)).

Figure 4.

Voxels in blue showed the left cerebral peduncle where FA correlates with disease progression rate in patients with ALS scanned in Oxford. The background image is the mean FA and the coordinate is in MNI152 space. The plot of the FA of this region versus the rate of disease progression (units/month) in 13 patients with ALS is displayed on the right side of the figure.

DISCUSSION

Using TBSS, we demonstrated that there were localised changes in FA between patients with PLS compared to patients with ALS, and found that some of these changes were clinically relevant because of their relationship with disease progression rate. These findings suggest that it is possible to distinguish between these two conditions using DTI and TBSS, and obtain more insights into their respective mechanisms of brain damage.

FA Changes in ALS Patients Compared With Controls Scanned in London and Oxford

We found that patients with established ALS scanned in London had reduced FA compared to controls in all regions along the CST, including the cerebral peduncle, the internal capsule, the corona radiata, and the white matter adjacent to the PMC, which is consistent with previous articles that employed standard VBM analyses [Agosta et al., 2007; Sach et al., 2004; Sage et al., 2007]. On the other hand, patients with ALS scanned in Oxford showed lower FA compared to controls only in one of the regions of interest investigated, i.e., the white matter adjacent to the left PMC. This raises two important points. First, the same post‐processing of scans acquired on different cohorts and with different scanners may not give the same results, confirming the need to standardize the DTI measurements across centers to allow translation of the results of imaging studies to the general population. Secondly, the white matter adjacent to the PMC, from which part of the cortico‐spinal fibres originate, seems to be consistently damaged in ALS. However, previous studies, using a region of interest approach, reported that reduced FA is more often detected lower down in the CST, such as the internal capsule [Ellis et al., 1999; Graham et al., 2004; Toosy et al., 2003] and the cerebral peduncle [Hong et al., 2004; Toosy et al., 2003].

We found that the London ALS patients also showed lower FA than controls in regions outside the motor network, such as the corpus callosum and the white matter underneath the pre‐motor, primary sensory, frontal and pre‐frontal cortex, confirming that established ALS is a multisystem degenerative disease [Agosta et al., 2007; Sach et al., 2004; Sage et al., 2007].

The most likely interpretation for lower FA in regions in the CST and in the white matter adjacent to the PMC, frontal cortex, pre‐motor cortex and primary sensory cortex in patients with ALS is that there is a ‘dying back’ degeneration of axonal fibres that contribute to the CST [Beaulieu et al., 1996; Pierpaoli et al., 2001; Schmierer et al., 2007]. This is consistent with the known loss of motor neurons with astrocytic gliosis [Brownell et al., 1970] and accumulation of intra‐neuronal inclusions in ALS [Chou and Huang 1988; Leigh et al., 1989].

One possible limitation of this study is that patients with ALS and controls scanned in London were not age matched. We attempted to correct for this by adjusting for age, but this analysis only allowed us to remove the first‐order effect of age and did not correct for the possible non‐linear effect of age on the FA. However, there is evidence that the decline in FA with age is linear from about 20 years of age onwards [Sullivan and Pfefferbaum, 2006], so we feel that the reported differences in FA between patients and controls is a real finding rather than related to age. On the other hand, we found less diffuse FA abnormalities when patients with ALS and aged matched controls scanned in Oxford were compared.

A limitation of the investigation of differences in FA between patients and controls using TBSS is that the more peripheral regions of the white matter are not included in the comparison. However, this ensures that the areas tested are those where the tracts have been reasonably well aligned to the skeleton and where there is not much cross‐subject variability. Whenever comparisons between ALS and controls are performed using a voxelwise approach, the possible bias, induced by the presence of brain atrophy in the patient group, should be considered, because brain atrophy can lead to a spatial shift of the brain structures. We have visually checked the results of the registration performed in this study and confirmed that they were correct.

FA Differences Between Patients with PLS and Patients with ALS Studied in Oxford

The most clinically interesting result of this article is that there were regional differences in white matter FA between patients with PLS and patients with ALS studied in Oxford. Interestingly, we did not find global differences in FA when the whole skeletonised FA was compared between controls, ALS and PLS patients, suggesting that the differences between groups are localised to specific white matter regions, rather than more diffusely distributed.

Patients with PLS showed a lower FA in the body of the corpus callosum and in the white matter adjacent to the right PMC compared with patients with ALS. In turn, patients with ALS did not have lower FA than controls in these areas (as discussed earlier), but in both these regions patients with PLS showed lower FA than controls. Furthermore, patients with PLS also showed lower FA than controls in the white matter underneath the left PMC. It has been reported that in both motor neuron diseases there is loss or shrinkage of the Betz cells in the PMC, but this feature is conspicuous in all cases of ALS, and cortical motor neurons seem to degenerate more in PLS than ALS [Hudson et al., 1993]. A previous imaging study demonstrated that PLS can be distinguished from ALS by more extensive focal cortical atrophy [Kuipers‐Upmeijer et al., 2001; Pringle et al., 1992], although the atrophy of the motor cortex is not an exclusive characteristic of PLS patients. Therefore, all these findings together support the hypothesis that the involvement of the PMC, at least on the right side, and the associated ‘dying back’ degeneration of neurons of the CST, is more prominent in PLS than ALS. Further, the degeneration of collaterals of the CST and of fibres that connect the corresponding regions of both hemispheres [Crosby et al., 1962] appears to be more pronounced in PLS, and leads to a lower FA in the body of the corpus callosum compared with ALS.

We found that patients with ALS had a reduced FA in the white matter adjacent to the right pre‐frontal cortex (e.g., superior frontal gyrus) when compared with PLS patients. This might reflect the degeneration of neurons originating in the atrophic pre‐frontal cortex [Chang et al., 2005; Ellis et al., 2001], and could be related to the findings of frequent cognitive impairment in ALS [Ringholz et al., 2005; Rippon et al., 2006] and normal intellectual function in PLS [Pringle et al., 1992]. However, the presence of a mild frontal lobe dysfunction has also been described in PLS [Caselli et al., 1995]. As we have not performed a systematic neuropsychological assessment, we cannot answer the question whether the ALS patients, who showed lower FA in the pre‐frontal regions, had a subtle frontal lobe dysfunction. A key issue to clarify in future longitudinal studies is the relationship between MRI changes, cognitive dysfunction and motor impairment in these two presentations of motor neuron disease.

Correlations Between FA and Disease Progression Rate in Patients with PLS and ALS Studied in Oxford

The significant correlations between FA and the rate of disease progression are of interest. In particular, we found that: (i) the FA in the white matter adjacent to the right PMC was lower in patients with PLS with more rapid disease progression, (ii) the FA in the left cerebral peduncle, right posterior limb of the internal capsule, right corona radiata, white matter underneath the right primary motor cortex, and body of the corpus callosum was lower in patients with ALS who showed a greater disease progression rate.

To date, significant correlations between FA and clinical scales in PLS have not been reported, and our results in this small cohort of patients suggest that it is worthwhile to continue assessing diffusion changes and correlations with disease progression rate in PLS. In particular, it will be interesting to see whether the region that showed the greater correlation with disease progression rate remains the white matter underneath the right PMC even with different cohorts and scanning protocols. Although the presence of a relationship between the FA in the CST and disease severity is expected in patients with ALS, it has not been always confirmed [Ciccarelli et al., 2006; Hong et al., 2004; Toosy et al., 2003]. This may be due to several reasons, such as the different qualities of diffusion images, different disease durations of the population studied, the use of different clinical scales, and the relative lack of sensitivity of the ALS rating scale to upper motor neuron involvement. It is interesting that a recent study has described the most significant correlation between disease severity and FA outside the CST (i.e., in the pre‐frontal lobe) [Sage et al., 2007], but we have not confirmed such a relationship in our cohort, although we described a significant correlation with the FA of the corpus callosum. The significant correlation found between FA in the cerebral peduncle and the disease progression rate in the ALS patients scanned in Oxford confirms the results of our previous investigation of ALS patients scanned in London using TBSS [Smith et al., 2006].

Finally, the significant differences in FA between the subject groups scanned in Oxford, as well as the significant correlations between FA and disease progression rate, appeared to be asymmetrical, since they were statistically significant only one side of the brain. These findings are in agreement with the report of asymmetry in motor neuron pathology [Swash et al., 1988] and previous imaging findings in ALS [Sage et al., 2007; Toosy et al., 2003].

In conclusion, future longitudinal studies investigating larger cohorts of patients with repeated clinical assessment and diffusion measures are needed to test whether FA can be used as a marker of disease progression in ALS and PLS. A fundamental question to address in future investigations is whether FA changes can distinguish between these two presentations of motor neuron disease early in the disease course.

Acknowledgements

Dr. Olga Ciccarelli is a Wellcome Trust Advanced Clinical Fellow. Dr. Tim Behrens is supported by the Medical Research Council. Dr. Heidi Johansen‐Berg is a Wellcome Trust Advanced Training Fellow. The authors thank the subjects for kindly agreeing to take part in this study. Part of this work was undertaken at UCLH/UCL who received a proportion of funding from the Department of Health's NIHR Biomedical Research Centres funding scheme.

REFERENCES

- The Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Functional Rating Scale. Assessment of activities of daily living in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. The ALS CNTF treatment study (ACTS) phase I–II Study Group. Arch Neurol (1996): 53: 141–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abe O,Yamada H,Masutani Y,Aoki S,Kunimatsu A,Yamasue H,Fukuda R,Kasai K,Hayashi N,Masumoto T,Mori H,Soma T,Ohtomo K. ( 2004): Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: Diffusion tensor tractography and voxel‐based analysis. NMR Biomed 17: 411–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agosta F,Pagani E,Rocca MA,Caputo D,Perini M,Salvi F,Prelle A,Filippi M. ( 2007): Voxel‐based morphometry study of brain volumetry and diffusivity in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients with mild disability. Hum Brain Mapp 28: 1430–1438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashburner J,Friston KJ ( 2000): Voxel‐based morphometry—The methods. Neuroimage 11: 805–821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basser PJ,Mattiello J,LeBihan D ( 1994): Estimation of the effective self‐diffusion tensor from the NMR spin echo. J Magn Reson B 103: 247–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaulieu C,Does MD,Snyder RE,Allen PS ( 1996): Changes in water diffusion due to Wallerian degeneration in peripheral nerve. Magn Reson Med 36: 627–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks BR,Miller RG,Swash M,Munsat TL ( 2000): El Escorial revisited: Revised criteria for the diagnosis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Other Motor Neuron Disord 1: 293–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownell B,Oppenheimer DR,Hughes JT ( 1970): The central nervous system in motor neurone disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 33: 338–357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruyn RP,Koelman JH,Troost D,de Jong JM ( 1995): Motor neuron disease (amyotrophic lateral sclerosis) arising from longstanding primary lateral sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 58: 742–744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caselli RJ,Smith BE,Osborne D ( 1995): Primary lateral sclerosis: A neuropsychological study. Neurology 45: 2005–2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang JL,Lomen‐Hoerth C,Murphy J,Henry RG,Kramer JH,Miller BL,Gorno‐Tempini ML. ( 2005): A voxel‐based morphometry study of patterns of brain atrophy in ALS and ALS/FTLD. Neurology 65: 75–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou SM,Huang TE ( 1988): Giant axonal spheroids in internal capsules of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis brains revisited. Ann Neurol 24: 168. [Google Scholar]

- Ciccarelli O,Behrens TE,Altmann DR,Orrell RW,Howard RS,Johansen‐Berg H,Miller DH,Matthews PM,Thompson AJ. ( 2006): Probabilistic diffusion tractography: A potential tool to assess the rate of disease progression in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Brain 129: 1859–1871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosby EC,Humphrey T,Laver EW ( 1962): Correlative Anatomy of the Nervous System. New York: Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis CM,Simmons A,Jones DK,Bland J,Dawson JM,Horsfield MA,Williams SC,Leigh PN. ( 1999): Diffusion tensor MRI assesses corticospinal tract damage in ALS. Neurology 53: 1051–1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis CM,Suckling J,Amaro E Jr,Bullmore ET,Simmons A,Williams SC,Leigh PN. ( 2001): Volumetric analysis reveals corticospinal tract degeneration and extramotor involvement in ALS. Neurology 57: 1571–1578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham JM,Papadakis N,Evans J,Widjaja E,Romanowski CA,Paley MN,Wallis LI,Wilkinson ID,Shaw PJ,Griffiths PD. ( 2004): Diffusion tensor imaging for the assessment of upper motor neuron integrity in ALS. Neurology 63: 2111–2119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hainfellner JA,Pilz P,Lassmann H,Ladurner G,Budka H ( 1995): Diffuse Lewy body disease as substrate of primary lateral sclerosis. J Neurol 242: 59–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henkelman RM ( 1985): Measurement of signal intensities in the presence of noise in MR images. Med Phys 12: 232–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong YH,Lee KW,Sung JJ,Chang KH,Song IC ( 2004): Diffusion tensor MRI as a diagnostic tool of upper motor neuron involvement in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurol Sci 227: 73–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horsfield MA,Jones DK ( 2002): Applications of diffusion‐weighted and diffusion tensor MRI to white matter diseases—A review. NMR Biomed 15: 570–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson AJ,Kiernan JA,Munoz DG,Pringle CE,Brown WF,Ebers GC ( 1993): Clinicopathological features of primary lateral sclerosis are different from amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Brain Res Bull 30: 359–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkinson M,Smith S ( 2001): A global optimisation method for robust affine registration of brain images. Med Image Anal 5: 143–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones DK ( 2004): The effect of gradient sampling schemes on measures derived from diffusion tensor MRI: A Monte Carlo study. Magn Reson Med 51: 807–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones DK,Horsfield MA,Simmons A ( 1999): Optimal strategies for measuring diffusion in anisotropic systems by magnetic resonance imaging. Magn Reson Med 42: 515–525. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones DK,Symms MR,Cercignani M,Howard RJ ( 2005): The effect of filter size on VBM analyses of DT‐MRI data. Neuroimage 26: 546–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuipers‐Upmeijer J,de Jager AE,Hew JM,Snoek JW,van Weerden TW ( 2001): Primary lateral sclerosis: Clinical, neurophysiological, and magnetic resonance findings. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 71: 615–620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leigh PN,Dodson A,Swash M,Brion JP,Anderton BH ( 1989): Cytoskeletal abnormalities in motor neuron disease. An immunocytochemical study. Brain 112 (Part 2): 521–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride G ( 2004): Is PLS part of the ALS spectrum or not? Neurol Today 4: 39–43. [Google Scholar]

- Nichols TE,Holmes AP ( 2002): Nonparametric permutation tests for functional neuroimaging: A primer with examples. Hum Brain Mapp 15: 1–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunes RG,Jezzard P,Clare S ( 2005): Investigations on the efficiency of cardiac‐gated methods for the acquisition of diffusion‐weighted images. J Magn Reson 177: 102–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierpaoli C,Barnett A,Pajevic S,Chen R,Penix LR,Virta A,Basser P. ( 2001): Water diffusion changes in Wallerian degeneration and their dependence on white matter architecture. Neuroimage 13: 1174–1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierpaoli C,Basser PJ ( 1996): Toward a quantitative assessment of diffusion anisotropy. Magn Reson Med 36: 893–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pringle CE,Hudson AJ,Munoz DG,Kiernan JA,Brown WF,Ebers GC ( 1992): Primary lateral sclerosis. Clinical features, neuropathology and diagnostic criteria. Brain 115 (Part 2): 495–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reese TG,Heid O,Weisskoff RM,Wedeen VJ ( 2003): Reduction of eddy‐current‐induced distortion in diffusion MRI using a twice‐refocused spin echo. Magn Reson Med 49: 177–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ringholz GM,Appel SH,Bradshaw M,Cooke NA,Mosnik DM,Schulz PE ( 2005): Prevalence and patterns of cognitive impairment in sporadic ALS. Neurology 65: 586–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rippon GA,Scarmeas N,Gordon PH,Murphy PL,Albert SM,Mitsumoto H,Marder K,Rowland LP,Stern Y. ( 2006): An observational study of cognitive impairment in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Arch Neurol 63: 345–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowland LP,Shneider NA ( 2001): Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. N Engl J Med 344: 1688–1700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rueckert D,Sonoda LI,Hayes C,Hill DL,Leach MO,Hawkes DJ ( 1999): Nonrigid registration using free‐form deformations: Application to breast MR images. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 18: 712–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sach M,Winkler G,Glauche V,Liepert J,Heimbach B,Koch MA,Büchel C,Weiller C. ( 2004): Diffusion tensor MRI of early upper motor neuron involvement in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Brain 127: 340–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sage CA,Peeters RR,Gorner A,Robberecht W,Sunaert S ( 2007): Quantitative diffusion tensor imaging in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neuroimage 34: 486–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmierer K,Wheeler‐Kingshott CA,Boulby PA,Scaravilli F,Altmann DR,Barker GJ,Tofts PS,Miller DH. ( 2007): Diffusion tensor imaging of post mortem multiple sclerosis brain. Neuroimage 35: 467–477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SM,Jenkinson M,Johansen‐Berg H,Rueckert D,Nichols TE,Mackay CE,Watkins KE,Ciccarelli O,Cader MZ,Matthews PM,Behrens TE. ( 2006): Tract‐based spatial statistics: Voxelwise analysis of multi‐subject diffusion data. Neuroimage 31: 1487–1505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan EV,Pfefferbaum A ( 2006): Diffusion tensor imaging and aging. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 30: 749–761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swash M,Scholtz CL,Vowles G,Ingram DA ( 1988): Selective and asymmetric vulnerability of corticospinal and spinocerebellar tracts in motor neuron disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 51: 785–789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Symms MR,Barker GJ,Franconi F,Clark CA ( 1997): Correction of eddy‐current distortions in diffusion‐weighted echo‐planar images with a two‐dimensional registration technique. Proc Int Soc Magn Reson Med 3: 1723. [Google Scholar]

- Toosy AT,Werring DJ,Orrell RW,Howard RS,King MD,Barker GJ,Miller DH,Thompson AJ. ( 2003): Diffusion tensor imaging detects corticospinal tract involvement at multiple levels in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 74: 1250–1257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S,Melhem ER ( 2005): Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and primary lateral sclerosis: The role of diffusion tensor imaging and other advanced MR‐based techniques as objective upper motor neuron markers. Ann NY Acad Sci 1064: 61–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S,Poptani H,Woo JH,Desiderio LM,Elman LB,McCluskey LF,Krejza J,Melhem ER. ( 2006): Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: Diffusion‐tensor and chemical shift MR imaging at 3.0 T. Radiology 239: 831–838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler‐Kingshott CM,Boulby PA,Symms M,Barker GJ ( 2002): Optimised cardiac gating for high‐resolution whole brain DTI on a standard scanner. Proc Intl Soc Mag Reson Med 10: 1118 (Ref Type: Abstract). [Google Scholar]