Abstract

Recently, it has been suggested that backwardly masked, and thus subliminally presented, fearful eyes are processed by the amygdala. Here, we investigated in four functional magnetic resonance imaging experiments whether the amygdala responds to subliminally presented fearful eyes per se or whether an interaction of masked eyes with the masks or with parts of the masks used for backward masking might be responsible for the amygdala activation. In these experiments, we varied the mask as well as the position of the target eyes. The results show that the amygdala does not respond to masked fearful eyes per se but to an interaction between masked fearful eyes and the eyes of neutral faces used for masking. This finding questions the hypothesis that the amygdala processes context‐free parts of the human face without awareness. Hum Brain Mapp, 2010. © 2010 Wiley‐Liss, Inc.

Keywords: amygdala, fMRI, fear, eyes, faces, backward masking

INTRODUCTION

The processing of the eye region of faces is important for the adequate interpretation of emotional facial expressions [Adolphs et al., 2005]. Functional imaging studies indicated that “wide‐eyed” facial expressions such as fear and even only the eye region of these expressions activate the amygdala [Hardee et al., 2008; Morris et al., 2002, 1996; Whalen et al., 1998, 2004], a brain region supposed to be important for the processing of threat‐related but also other emotionally salient stimuli [Adams et al., 2003; LeDoux 1996; Quadflieg et al., 2008; Straube et al., 2004, 2006, 2007, 2008; Zald 2003].

Furthermore, a recent study [Whalen et al., 2004] showed that backwardly masked and thus consciously not perceived fearful schematic eyes induce stronger amygdala activation than masked happy eyes. The authors concluded that a context‐free, threat‐related part of the human face might be processed by the amygdala in the absence of visual awareness. This conclusion strongly depends on the validity of the experimental procedures used in this study. In this study, eyes were masked by neutral faces, in particular the eye region of neutral faces. If the activation of the amygdala to masked fearful eyes is a reliable effect, then this effect should also be observed when masks that do not show faces or when other parts of the face than eyes are used for masking the target eyes.

However, one has to consider that the results in the Whalen et al. [ 2004] study might have been affected by an interaction between masked eyes and the eyes of the mask. Neutral faces with “middle‐wide” eyes mask small happy eyes better than wide fearful eyes (see also Fig. 1). This, for example, might induce differential flicker effects in the eye region of the mask, which again possibly influences the response of the amygdala, since the amygdala is strongly involved in the processing of ambiguous information [Davis and Whalen, 2001] and subtle changes expressed in human eyes [Adams et al., 2003; Demos et al., 2008; Straube et al., in press].

Figure 1.

Examples of stimuli. (a) Fearful eyes. (b) Happy eyes. (c) Mask used in experiment 2. (d) Mask used in Experiments 1, 3, and 4.

In order to investigate whether the amygdala responds to subliminally presented fearful eyes per se or whether an interaction of masked eyes with the masks or with parts of the masks used for backward masking might be responsible for the amygdala activation, we conducted four functional magnetic resonance imaging experiments. In these experiments, we varied the mask as well as the position of the target eyes. Thus, subjects were briefly presented with fearful and happy eyes, which were immediately backward‐masked either by a neutral face or by pictures of flowers. In two experiments, the masked eyes were presented below the eyes of the neutral face used for masking. Only subjects who did not report any awareness of the masked stimuli or the masking procedure were included in the analysis. If the amygdala responds to subliminal fearful vs. happy eyes per se then this effect should be independent of the mask (face or no face) or the position of the masked eyes (behind or below the eyes of the mask).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

Altogether, 103 healthy volunteers with normal or corrected‐to‐normal vision were scanned. Forty‐three subjects were excluded from data analysis due to the following reasons: (1) conscious detection of any aspect of masked stimuli or masking procedure (Exp. 1‐4: 5, 4, 6, 22 subjects); (2) being an outlier in brain activation (see below; Exp. 1 and 2: in each case 1 subject; Exp. 3: 2 subjects; Exp. 4: 2 subjects); or (3) structural brain abnormalities (1 subject in Exp. 3). Thus, there were 60 finally included subjects (Experiments 1–4: 16, 16, 12, 16 subjects; mean age: 22.5, 21.5, 22.2, 22.3 years; females: 12, 10, 8, 10). For each experiment an independent sample was used. The study was approved by the ethics committee of the University of Jena and written informed consent was obtained from each participant prior to the experiment.

Experimental Procedures and Stimuli

Experiments and stimuli

We conducted four experiments. The design of each experiment followed the description of Whalen et al. [ 2004, 1998]. During two scanning runs, subjects were shown six 28 sec blocks (three per run) of masked fearful (F) or masked happy eyes (H) that alternated with 28‐s blocks showing a fixation cross. According to Whalen et al. [ 2004], masked stimuli and neutral face masks were black and white line drawings created by maximising the contrast of eight standardized gray‐scale images [Ekman and Friesen. 1976]. Pictures of eyes were created by removing all information from the face but the eyes (see Fig. 1). In Experiment 1, we exactly replicated the experiment of Whalen et al. [ 2004]. During MRI scanning, eye stimuli were backwardly masked by neutral faces. Each eye identity was masked by each of the other seven neutral face identities so that 56 target—mask pairs were presented in each block. In Experiment 2, we used the same methods as in Experiment 1 with the exception that another mask than a face was used. The new mask showed simple black and white drawings of eight different flowers sharing a part in the middle of the picture that masked the eyes (see Fig. 1). In Experiment 3, we investigated whether the amygdala activation to masked fearful eyes might also occur when the masked eyes are presented outside the eye region of the neutral face masks. Therefore, the target eyes were positioned 0.5 inches below the position of the eyes in Experiments 1 and 2 (see Fig. 1). To test the reliability of our findings we conducted a fourth experiment, in which the experimental conditions of Experiments 1 and 3 were combined, so that in each run either condition was presented. In this within‐subject investigation, we directly investigated possible interactions of category (fearful vs. happy) and position (behind vs. below the eyes of the mask) of masked eyes. Order of block category and masking condition were counterbalanced across subjects and runs.

Masked eyes were programmed to be shown for 16.7 ms (according to one cycle of a 60 Hz monitor) followed by the mask for 183 ms and by an inter stimulus interval (black screen) of 300 ms. Pictures were presented with Presentation software (version 9.81, Neurobehavioral Systems, USA) by means of a LCD data projector (TLP 710 E, Toshiba Corporation, Japan). Presentation time was checked with a photo diode (OPT101, Burr‐Brown, Tucson, AZ, USA). DASYLab 5 software (Datalog GmbH, Germany) was used to record luminance changes at a sampling rate of 2 kHz. BrainVision Analyzer 2.0 (Brain Products GmbH, Germany) was used to analyze the raw data. Picture onset was set as the point when luminance level was above 3 SD of baseline values [Wiens et al., 2004]. Picture offset was defined as the point when luminance dropped below this level. According to this test procedure pictures were presented with a mean presentation time of 16.16 ms with low variability (100 test trials, SD = 0.5 ms), suggesting that the intended presentation time was matched.

Debriefing and analysis of detection scores

Subjects' debriefing and analysis of objective detection sensitivity also followed the methods described by Whalen et al. [ 2004]. After the scanning session, subjects were asked to describe any aspects of the stimuli. Thereafter they were informed about the masking procedure and shown exemplars of the masked eyes. Subjects had to indicate whether they had seen anything similar during scanning and were included in the statistical analysis, if they reported not having seen any stimuli except the masks. In Experiment 4 a relatively huge number of participants had to be excluded. There are two reasons for this increased awareness of at least parts of the masking procedure: (1) Regions outside the eye region do not mask the eyes optimally, and (2) moving target positions (from the eyes of the mask to a more ventral part of the mask) increase either the conscious detection of a flicker, or of the masked eyes, or of other aspects of the masking procedure. After debriefing, subjects viewed 12 blocks (24 blocks in Experiment 4 due to the use of two different masking conditions) of masked stimuli (each four blocks showing masked fearful eyes, masked happy eyes or none) and, after each block, they indicated whether big eyes, small eyes, or no stimuli had preceded the neutral masks even when the decision was based on differential flicker effects. Subjects were asked for estimation of stimuli block by block to adopt the procedure of Whalen et al. [ 2004], where this method was chosen, since the resulting data would be better related to blocked stimulus presentations during scanning. Better than chance performance was estimated via the calculation of a detection sensitivity index (d′) that was based on the relative frequencies of trials a masked stimulus was detected when presented [“hits” (H)] less the relative frequencies of trials a masked stimulus was “detected” when not presented [“false alarms” (FA); d′ = z‐score (relative frequencies H)—z‐score (relative frequencies FA), chance performance = 0 ± 1.74; z‐scores were based on standard normal distribution]. To adjust for nonoccupied cells (hits and false alarms) a correction according to the log‐linear rule [Hautus 1995] was conducted. Therefore a value of 0.5 was added to any cell frequencies. Each subject's detection sensitivity was estimated separately for each category (big eyes, small eyes, none eyes which refers to fearful, happy, no eyes) and then averaged.

To investigate whether there is a relation between detection scores and amygdala activation in Experiments 1 and 4, several tests were conducted. In line with Whalen et al. [ 2004] subjects were rank‐ordered according to their performance in the forced choice task. The rank‐ordering of subjects was practically identical when A′ the nonparametric analogue of d′ was used [Macmillan and Creelman, 2005]. Subjects of Experiments 1 and 4 were then divided into “Chance performers” (Exp. 1: N = 6, M d′Mean = 0.71, SD = 0.47; Exp. 4: N = 9, M d′Mean = 0.75, SD = 0.57), and “Above Chance performers” (Exp. 1: N = 10, M d′Mean = 2.52, SD = 0.34; Exp. 4: N = 7, M d′Mean = 2.36, SD = 0.22).

Statistical analysis was mainly based on nonparametric tests except for the higher factorial Experiment 4, for which no suited, powerful nonparametric tests are available. In this case, a repeated measure ANOVA was used, which is fairly robust against violations of the assumption of normal distribution [Keselman, 1998; Keselman et al., 2001].

fMRI

In the 1.5 T scanner (“Magnetom Vision plus”, Siemens, Erlangen, Germany), two runs of 97 volumes were acquired (T2* weighted echo‐planar sequence; TE = 50 ms, flip angle = 90°, matrix = 64 × 64, FOV = 192 mm, TR = 2.98 s, 30 axial slices with 3 mm thickness). Analysis of functional data was performed using the Brain Voyager QX software (version 1.7; Brain Innovation, Maastricht, The Netherlands). Primarily, all volumes were realigned to the first volume in order to minimize artifacts due to head movements. Data preprocessing comprised spatial (8‐mm Gaussian kernel) as well as temporal (high pass filter: 0.01 Hz) smoothing. The anatomical and functional images were coregistered and normalized to the Talairach space [Talairach and Tournoux, 1988]. Statistical analysis was performed by multiple linear regression of the signal time course at each voxel. The expected blood oxygen level‐dependent signal change for each eye category (fear, happy) and eye position (in Experiment 4: normal vs. shifted) was modeled by a hemodynamic response function. Statistical comparisons were conducted within our ROI (bilateral amygdala; defined with the Talairach daemon software, http://www.talairach.org/daemon.html) and the whole brain using a mixed effect analysis, which considers intersubject variance and permits population‐level inferences. First, voxelwise statistical maps were generated and the relevant, planned contrasts of predictor estimates (β‐weights) were computed for each individual. Second, a random effect group analysis of these individual contrasts was performed. Statistical parametric maps resulting from voxelwise analyses were considered as statistically significant for clusters that survived a correction for multiple comparisons. We used the approach as implemented in Brain Voyager [Goebel et al., 2006], which is based on a 3D extension of the randomization procedure described by [Forman et al., 1995]. First, voxel‐level threshold was set at an uncorrected P < 0.005 (ROI) or P < 0.001 (whole brain). Thresholded maps were then submitted to a ROI‐ or whole‐brain‐based correction for multiple comparisons. The correction criterion was based on the estimate of the map's spatial smoothness and on an iterative procedure (Monte Carlo simulation) for estimating cluster‐level false‐positive rates. After 1,000 iterations, the minimum cluster size threshold that yielded a cluster‐level false‐positive rate of 5% was applied to the statistical maps. To avoid any artifactual brain activation, we excluded all outliers in amygdala activation from analysis (see above). To characterize outliers we used the mean differential activation of the amygdala. Subjects with more than two standard deviations above or below the mean were excluded.

RESULTS

Behavioral Data

Only subjects who did not recognize any aspect of the masking procedure were included in the analysis. For these included subjects, the forced choice detection experiment showed, in accordance with data of the previous study of Whalen et al. [ 2004], an average detection score greater than 1.74 for 10 out of 16 participants in Experiment 1. Furthermore, this result was found for 3 out of 16 participants in Experiment 2, for 8 out of 12 participants in Experiment 3, and for 7 out of 16 participants in Experiment 4. In Experiments 1 and 2, detection scores for fearful versus happy eyes did not differ (Exp. 1: M d′big = 1.83, SDd′big = 0.99, M d′small = 1.58, SDd′small = 1.22, Z = −1.61, P = 0.107, Wilcoxon test; Exp. 2: M d′big = 1.42, SDd′big = 1.12, M d′small = 0.97, SDd′small = 0.88, Z = −1.648, P = 0.099, Wilcoxon test). In Experiment 3, there was a difference between the detection scores for fearful versus happy eyes (M d′big = 1.87, SDd′big = 0.48, M d′small = 1.49, SDd′small = 0.63, Z = −2.99, P = 0.003, Wilcoxon test). An ANOVA for repeated measures analyzing the detection scores of Experiment 4 revealed no significant main effects of eye category (F(1, 15) = 0.017, P = 0.899) and position of the masked eyes (F(1, 15) = 3.4, P = 0.085), but a significant interaction effect (F(1, 15) = 7.53, P = 0.015), due to increased detection of fearful masked eyes when masked eyes were in the shifted as compared to the original position (original position: M d′big = 0.95, SDd′big = 1.69, M d′small = 1.24, SDd′small = 1.29; shifted position: M d′big = 1.94, SDd′big = 1.01, M d′small = 1.69, SDd′small = 0.88).

fMRI Data

Experiment 1

In accordance with the previous study of Whalen et al. [ 2004], we found increased activation in the left ventral amygdala to masked fearful vs. masked happy eyes (x, y, z: −24, −4, −23; t(15) = 4.69; cluster size: 594 mm3; P < 0.05, corrected for multiple comparisons; see Fig. 2). In the right amygdala, there was also a tendency of increased activation to fearful vs. happy eyes which, however, did not passed the cluster threshold (x, y, z: 19, −7, −18; t(15) = 3.53; cluster size: 54 mm3; P > 0.05, corrected for multiple comparisons).

Figure 2.

Amygdala activation in the first three experiments. There was stronger activation in the left ventral amygdala to fearful versus happy eyes when eyes were masked by the eye region of neutral faces (Experiment 1). Statistical parametric maps of the ROI analysis are overlaid on a T1 scan (radiological convention: left = right; y = −4). No differential amygdala activation was observed when eyes were masked by flowers (Experiment 2) or when the target eyes were positioned below the eyes of the mask (Experiment 3). Pictures show masked stimuli superimposed on the masks. Here, the black‐white masks were gray scaled to be distinguished from masked stimuli.

For completeness, whole brain analysis revealed increased as well as decreased activation in several areas as indicated in Table I.

Table I.

Whole brain analysis of brain activation

| Region | Side | x | y | z | t‐value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exp. 1 (fear > happy) | |||||

| STG | R | 43 | 11 | −21 | 5.87 |

| L | −43 | 16 | −26 | 5.46 | |

| MTG | R | 61 | −29 | −14 | 4.48 |

| Fusiform Gyrus | R | 50 | −6 | −24 | 5.17 |

| Cuneus | L | −20 | −76 | 9 | 4.38 |

| Parahippocampal Gyrus | R | 20 | −9 | −25 | 3.91 |

| Exp. 1 (happy > fear) | |||||

| DLPFC | L | −50 | 5 | 28 | 4.76 |

| STG | L | −52 | 8 | −3 | 4.34 |

| ACC | L | −10 | 15 | 36 | 4.75 |

| Posterior Insula | R | 37 | −17 | 13 | 4.59 |

| Postcentral gyrus | R | 49 | −24 | 36 | 3.98 |

| Putamen | L | −17 | 13 | 2 | 5.16 |

| Exp. 2 (happy > fear) | |||||

| MPFC | L/R | 3 | 34 | 37 | 4.74 |

| Postcentral gyrus | L | −53 | −14 | 17 | 4.92 |

| Postcentral gyrus | R | −56 | −18 | 32 | 4.96 |

| Exp. 3 (happy > fear) | |||||

| MFG | R | 22 | 33 | 41 | 5.08 |

| MPFC | R | 10 | 45 | 20 | 5.53 |

| PCC | R | 2 | −53 | 17 | 4.63 |

| Exp. 4 (fear > happy) | |||||

| IFG | L | −31 | 33 | 0 | 4.81 |

| Exp. 4 (fear > happy; normal > shifted position) | |||||

| MPFC | L | −8 | 57 | 22 | 4.82 |

| MPFC | R | 7 | 45 | 39 | 4.56 |

| Anterior Insula | L | −29 | 18 | −3 | 5.85 |

| MTG | R | 58 | −42 | −6 | 4.60 |

| Superior Parietal Lobule | L | −23 | −63 | 45 | 5.58 |

| Precuneus | R | 8 | −64 | 36 | 5.52 |

| Fusiform gyrus | L | −40 | −45 | −9 | 5.15 |

| Lingual gyrus | L | −12 | −87 | −13 | 5.10 |

| Midbrain | R | 10 | −6 | −1 | 6.59 |

All P < 0.05, corrected for multiple comparisons at cluster level.

MFG, medial frontal gyrus; IFG, inferior frontal gyrus; DLPFC, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex; STG, superior temporal gyrus; MPFC, medial prefrontal cortex; MTG, medial temporal gyrus; ACC, anterior cingulate gyrus; PCC, posterior cingulate gyrus.

Experiment 2

In Experiment 2, flowers instead of faces were used for masking (see Fig. 1). With this manipulation we did not find a significant activation of the amygdala (for the above coordinates x, y, z: −24, −4, −23; t(15) = −0.10, P = 0.92, uncorrected; see Fig. 2). Figure 2 indicates that there even is no tendency of amygdala activation to masked eyes. Even when using an uncorrected threshold P < 0.05, there were no significant voxels. The cluster (at least three voxels) with the highest probability within the amygdala was found in the right amygdala (x, y, z: −17, −5, −19; t(15) = 1.3; P = 0.28), which indicates no clear tendency of an effect. Thus, any amygdala effect seems to depend on the condition that a face is used for backward masking.

Whole brain analysis showed decreased activation to fear vs. happy eyes in the medial prefrontal cortex and bilateral in the postcentral gyrus (see Table I).

Experiment 3

In Experiment 3, the target eyes were positioned below the eye region of the masks (see Fig. 2). In contrast to Experiment 1, where fearful eyes were presented behind the eyes of the mask, Experiment 3 revealed no evidence for increased amygdala activation to masked fearful vs. masked happy eyes (for x, y, z: −24, −4, −23; t(11) = 0.34, P = 0.74, uncorrected; see Fig. 2). The cluster (at least three voxels) with the highest probability within the amygdala was found in the left amygdala (x, y, z: −15, −5, −17; t(11) = 0.6; P = 0.56), which does not indicate any tendency of an effect.

Whole brain analysis revealed decreased activation to fear vs. happy eyes in the prefrontal cortex and the posterior cingulate cortex (Table I).

Experiment 4

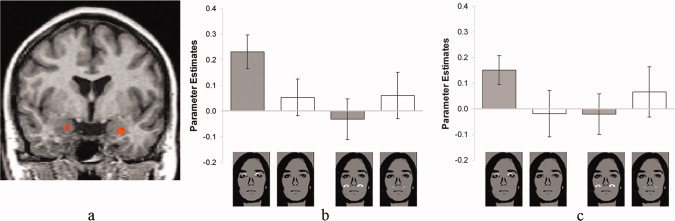

In this within‐subject investigation, we directly investigated possible interactions of category (fearful vs. happy) and position (behind vs. below the eyes of the mask) of masked eyes. Although there was no main effect of the category of masked eyes, we found increased activation bilaterally in the ventral amygdala to masked fearful vs. happy eyes for the original, as compared to the shifted position (left: x, y, z: −24, −4, −20; t(15) = 3.79; cluster size: 135 mm3; right: x, y, z: 22, −2, −16; t(15) = 3.08; cluster size: 81 mm3; in each case P < 0.05, corrected for multiple comparisons; see Fig. 3). This interaction was based on increased activation to fearful vs. happy eyes (left: t(15) = 3.73, right: t(15) = 3.14; all P < 0.05), while there was no differential effect to fearful vs. happy eyes for the shifted position (left: t(15) = −1.2, right: t(15) = −0.97; all P > 0.05).

Figure 3.

Amygdala activation in Experiment 4. (a) There was a stronger activation in the right and in the left ventral amygdala to fearful versus happy masked eyes at the original as compared with the shifted position. Statistical parametric maps of the ROI analysis are overlaid on a T1 scan (radiological convention: left = right; y = −4). (b and c) Mean signal change (beta ± SEM) of the maximally activated voxel in the right (b) and left (c) ventral amygdala for the four experimental conditions indicated by the pictures.

Whole brain analysis revealed no main effect of target position. There was a main effect of target category (fear > happy) in the inferior frontal gyrus (Table I). Furthermore, several areas showed increased activation to fearful vs. happy eyes in the original vs. the shifted condition, while there were no areas showing activation for fearful vs. happy eyes in the shifted vs. the original condition (see Table I).

Brain Activation and Postscanning Detection Scores

When comparing chance and above chance performers (based on the post‐scanning forced choice task), there was no difference in differential activation of the left amygdala (M ßdiff) between the two groups for either Experiment 1 (Chance performers: M ßdiff = 0.27, SD = 0.11; Above chance performers: M ßdiff = 0.14, SD = 0.18; t(14) = 1.6, P = 0.13) or Experiment 4 (Chance performers: M ßdiff = 0.22, SD = 0.33; Above chance performers: M ßdiff = 0.3, SD = 0.17; t(14) = −0.56, P = 0.58). A more conservative comparison was performed as well. On the basis of the lowest and the highest 25% of the rank ordering, subjects of Experiments 1 and 4 were divided into two groups of equal size (N = 4). Signal change did not differ between these two extreme groups of poorest detectors (Exp. 1: M ßdiff = 0.29, SD = 0.14; Exp. 4: M ßdiff = 0.32, SD = 0.20) versus best detectors (Exp.1: M ßdiff = 0.21, SD = 0.22; Exp. 4: M diff = 0.50, SD = 0.53; Exp.1: Z = −0.44, P = 0.66; Exp. 4: Z = 0, P = 1; Mann Whitney U test). Thus, comparable with the results reported by Whalen et al. [ 2004] the behavioral data indicate the lack of any systematic relation between the detection ability measured after the scanning session and the differential activation of the amygdala during the preceding passive viewing task.

DISCUSSION

The present study investigated whether the amygdala responds to subliminally presented fearful eyes per se or whether an interaction of masked eyes with the masks or with parts of the masks used for backward masking might be responsible for the amygdala activation. For this purpose we conducted four functional magnetic resonance imaging experiments. Taken together, the data show that masked fearful eyes do not induce stronger amygdala activation than masked happy eyes. Rather, an interaction of the masked eyes with the eye region of neutral faces used for backward masking is the critical mediator for the differential activation of the amygdala to masked eyes.

This is in contrast to the assumption that fearful eyes that are presented without any contextual face information are processed by the human amygdala, as suggested by a previous study [Whalen et al., 2004]. Here, we propose that other mechanisms are likely responsible for the effect found in the study of Whalen et al. [ 2004]. Clearly, the effect was based on specific masking conditions, in particular the interaction between masked eyes and eyes of the mask. One possible reason for this finding is that masked wide eyes, compared to small happy eyes, induce stronger flicker effects and greater ambiguity in the neutral eyes of the mask. The amygdala strongly responds to the amount of ambiguity expressed by eyes but also to subtle changes in the eyes [Adams et al., 2003; Demos et al., 2008]. Thus, even though subjects did not spontaneously report flicker effects, they partially may have used these effects to classify the type of masked eyes in the forced choice experiment. Alternative explanations might also be possible, such as some kind of summation effect between target and mask. However, each explanation needs to address the fact that the masked fearful eyes are associated with increased amygdala activation only within the context that the eye region of the neutral face mask is used to mask fearful and happy target eyes.

It should be noted that the present findings do not question the importance of the amygdala in processing information expressed by human eyes, since only the interaction between fearful masked eyes and eyes of the mask activated the amygdala. Thus, the results are in accordance with findings showing that the amygdala is strongly involved in automatic responding to human eyes per se [Adolphs et al., 2005; Spezio et al., 2007] and specific eye information such as ambiguity [Adams et al., 2003], size of eyes [Demos et al., 2008; Hardee et al., 2008] and gaze [Adams et al., 2003; Akiyama et al., 2007; Hadjikhani et al., 2008; Straube et al., in press]. For example, patients with amygdala lesions show disturbed attention to eye information and impaired attentional cuing effects by eye whites or eye gaze [Adolphs et al., 2005; Akiyama et al., 2007; Spezio et al., 2007]. Furthermore, consciously not recognized size of the pupil of eyes seems to be able to modulate the activation of the amygdala [Demos et al., 2008]. These findings suggest that the amygdala, besides its role in emotion, is relevant for attending to potentially salient information or ambiguous social signals provided by human eyes. On the basis of these facts, even very subtle changes expressed in human eyes can be expected to activate the amygdala. Our results suggest that this role of the amygdala is also evident in backward masking conditions, where masked stimuli induce subtle effects in neutral eyes of the mask. Further studies should test whether this interaction between masked targets and masks might at least partially be responsible for the neural effects under conditions where complete fearful faces, masked by neutral faces, have been shown to induce increased amygdala activation [Liddell et al., 2005; Whalen et al., 1998; but see Pessoa 2005; Pessoa et al., 2006; Phillips et al., 2004].

We found differential activation in both amygdalae. Although some authors suggest that especially the right amygdala might be involved in unconscious processing of threat [Morris et al., 1998], others suggest that the right amygdala might mediate general arousal to stimuli and the left amygdala might allow discrimination of stimuli, even unconsciously [Glascher and Adolphs, 2003]. In the present design, both amygdalae might respond to behavioral relevant (unconscious) ambiguity expressed by the neutral eyes of the mask. The left amygdala might be more strongly involved in potential discrimination of different eye flicker, while the right amygdala might mediate the arousal response. However, this remains to be investigated in future studies.

A limitation of this study is that our masking procedures induced somewhat bizarre conditions (eyes masked by flowers; eyes below the eyes of the mask) for the perceptual system, which might lead to general redistribution of resources. However, there was no indication, at least in terms of generally increased activation outside the amygdala, for a general difference between masking conditions. However, further studies with other kinds of masks should investigate this issue in more detail. Whole brain analysis showed generally decreased activation in the medial prefrontal cortex in accordance with the study of Whalen et al. [ 2004]. This, however, was not restricted to Experiment 1. Thus, also Experiments 2 and 3 led very likely to attentional cuing effects, which might also be based on a flicker in the masks, with deactivation of default areas [Raichle et al., 2001]. However, because of the absence of a face mask or of an interaction with the eyes of the mask there was no activation of the amygdala.

A further limitation might be the relatively low sample size in each experiment. It should be noted, however, that we report data of 60 finally included subjects and our conclusions are based on several experiments with independent samples. In fact, we show an independent replication of the (absence of) effects within one study.

In conclusion, we found no evidence that masked fearful eyes activate the amygdala. Rather, an interaction between masked eyes and eyes of the mask is the basis for the amygdala effect. This result suggests that the amygdala strongly responds to subtle changes in the eyes of the mask. Most importantly, our findings question the hypothesis that context‐free parts of the human face are processed by the human amygdala in the absence of visual awareness.

REFERENCES

- Adams RB, Gordon HL, Baird AA, Ambady N, Kleck RE ( 2003): Effects of gaze on amygdala sensitivity to anger and fear faces. Science 300: 1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adolphs R, Gosselin F, Buchanan TW, Tranel D, Schyns P, Damasio AR ( 2005): A mechanism for impaired fear recognition after amygdala damage. Nature 433: 68–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akiyama T, Kato M, Muramatsu T, Umeda S, Saito F, Kashima H ( 2007): Unilateral amygdala lesions hamper attentional orienting triggered by gaze direction. Cerebral Cortex 17: 2593–2600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demos KE, Kelley WM, Ryan SL, Davis FC, Whalen PJ ( 2008): Human amygdala sensitivity to the pupil size of others. Cerebral Cortex 18: 2729–2734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekman P, Friesen WV ( 1976): Pictures of Facial Affect. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press. [Google Scholar]

- Forman SD, Cohen JD, Fitzgerald M, Eddy WF, Mintun MA, Noll DC ( 1995): Improved assessment of significant activation in functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI): Use of a cluster‐size threshold. Magn Reson Med 33: 636–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glascher J, Adolphs R ( 2003): Processing of the arousal of subliminal and supraliminal emotional stimuli by the human amygdala. J Neurosci 23: 10274–10282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goebel R, Esposito F, Formisano E ( 2006): Analysis of functional image analysis contest (FIAC) data with brainvoyager QX: From single‐subject to cortically aligned group general linear model analysis and self‐organizing group independent component analysis. Hum Brain Mapp 27: 392–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadjikhani N, Hoge R, Snyder J, de Gelder B ( 2008): Pointing with the eyes: The role of gaze in communicating danger. Brain Cogn 68: 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardee JE, Thompson JC, Puce A ( 2008): The left amygdala knows fear: Laterality in the amygdala response to fearful eyes. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci 3: 47–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hautus MJ ( 1995): Corrections for extreme proportions and their biasing effects on estimated values of D′. Behav Res Methods Instruments Comput 27: 46–51. [Google Scholar]

- Keselman HJ ( 1998): Testing treatment effects in repeated measures designs: An update for psychophysiological researchers. Psychophysiology 35: 470–478. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keselman HJ, Algina J, Kowalchuk RK ( 2001): The analysis of repeated measures designs: A review. Br J Math Stat Psychol 54: 1–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeDoux JE ( 1996): The Emotional Brain. New York: Simon & Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Liddell BJ, Brown KJ, Kemp AH, Barton MJ, Das P, Peduto A, Gordon E, Williams LM ( 2005): A direct brainstem‐amygdala‐cortical ‘alarm’ system for subliminal signals of fear. Neuroimage 24: 235–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macmillan NA, Creelman CD ( 2005): Detection Theory: A User's Guide. Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Morris JS, Frith CD, Perrett DI, Rowland D, Young AW, Calder AJ, Dolan RJ ( 1996): A differential neural response in the human amygdala to fearful and happy facial expressions. Nature 383: 812–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JS, deBonis M, Dolan RJ ( 2002): Human amygdala responses to fearful eyes. Neuroimage 17: 214–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pessoa L ( 2005): To what extent are emotional visual stimuli processed without attention and awareness? Curr Opin Neurobiol 15: 188–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pessoa L, Japee S, Sturman D, Ungerleider LG ( 2006): Target visibility and visual awareness modulate amygdala responses to fearful faces. Cerebral Cortex 16: 366–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips ML, Williams LM, Heining M, Herba CM, Russell T, Andrew C, Bullmore ET, Brammer MJ, Williams SCR, Morgan M, Young AW, Gray JA ( 2004): Differential neural responses to overt and covert presentations of facial expressions of fear and disgust. Neuroimage 21: 1484–1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quadflieg S, Mohr A, Mentzel H‐J, Miltner WHR, Straube T ( 2008): Modulation of the neural network involved in the processing of anger prosody: The role of task‐relevance and social phobia. Biol Psychol 78: 129–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raichle ME, MacLeod AM, Snyder AZ, Powers WJ, Gusnard DA, Shulman GL ( 2001): A default mode of brain function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 676–682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spezio ML, Huang P‐YS, Castelli F, Adolphs R ( 2007): Amygdala damage impairs eye contact during conversations with real people. J Neurosci 27: 3994–3997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straube T, Kolassa IT, Glauer M, Mentzel HJ, Miltner WHR ( 2004): Effect of task conditions on brain responses to threatening faces in social phobics: An event‐related functional magnetic resonance Imaging study. Biol Psychiatry 56: 921–930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straube T, Mentzel H‐J, Miltner WHR ( 2006): Neural mechanisms of automatic and direct processing of phobogenic stimuli in specific phobia. Biol Psychiatry 59: 162–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straube T, Weiss T, Mentzel HJ, Miltner WHR ( 2007): Time course of amygdala activation during aversive conditioning depends on attention. Neuroimage 34: 462–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straube T, Pohlack S, Mentzel HJ, Miltner WHR ( 2008): Differential amygdala activation to negative and positive emotional pictures during an indirect task. Behav Brain Res 191: 285–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straube T, Langohr B, Schmidt S, Mentzel H‐J, Miltner WH: Increased amygdala activation to averted versus direct gaze in humans is independent of valence of facial expression Neuroimage. 2009. Oct 31. [Epub ahead print]. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Talairach J, Tournoux P ( 1988): Co‐Planar Stereotaxic Atlas of the Human Brain. Three‐Dimensional Proportional System: An Approach to Cerebral Imaging. Stutgart: Thieme. [Google Scholar]

- Whalen PJ, Kagan J, Cook RG, Davis FC, Kim H, Polis S, McLaren DG, Somerville LH, McLean AA, Maxwell JS, Johnstone T ( 2004): Human amygdala responsivity to masked fearful eye whites. Science 306: 2061–2061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whalen PJ, Rauch SL, Etcoff NL, McInerney SC, Lee MB, Jenike MA ( 1998): Masked presentations of emotional facial expressions modulate amygdala activity without explicit knowledge. J Neurosci 18: 411–418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiens S, Fransson P, Dietrich T, Lohmann P, Ingvar M, Ohman A ( 2004): Keeping it short—A comparison of methods for brief picture presentation. Psychol Sci 15: 282–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zald DH ( 2003): The human amygdala and the emotional evaluation of sensory stimuli. Brain Res Rev 41: 88–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]