Abstract

Dopamine (DA) modulates the response of the amygdala. However, the relation between dopaminergic neurotransmission in striatal and extrastriatal brain regions and amygdala reactivity to affective stimuli has not yet been established. To address this issue, we measured DA D2/D3 receptor (DRD2/3) availability in twenty‐eight healthy men (nicotine‐dependent smokers and never‐smokers) using positron emission tomography with [18F]fallypride. In the same group of participants, amygdala response to unpleasant visual stimuli was determined using blood oxygen level‐dependent (BOLD) functional magnetic resonance imaging. The effects of DRD2/3 availability in emotion‐related brain regions and nicotine dependence on amygdala response to unpleasant stimuli were examined by multiple regression analysis. We observed enhanced prefrontal DRD2/3 availability in those individuals with higher amygdala response to unpleasant stimuli. As compared to never‐smokers, smokers showed an attenuated amygdala BOLD response to unpleasant stimuli. Thus, individuals with high prefrontal DRD2/3 availability may be more responsive toward aversive and stressful information. Through this mechanism, dopaminergic neurotransmission might influence vulnerability for affective and anxiety disorders. Neuronal reactivity to unpleasant stimuli seems to be reduced by smoking. This observation could explain increased smoking rates in individuals with mental disorders. Hum Brain Mapp, 2010. © 2009 Wiley‐Liss, Inc.

Keywords: [18F]fallypride, PET, fMRI, amygdala, prefrontal cortex, emotion processing

INTRODUCTION

Dopamine (DA) modulates the response of the human amygdala [Kienast et al.,2008a; Tessitore et al.,2002]. Amygdala activation is potentially expressed by an inverted U‐shaped curve as a function of DA concentration [Salgado‐Pineda et al.,2005]. Accordingly, both hypodopaminergic and hyperdopaminergic states lead to decreased amygdala activation, and this dysregulation impairs the emotional evaluation of stimuli. Neuroimaging studies support this model. For example, patients suffering from Parkinson's disease demonstrate decreased amygdala reactivity to affective stimuli during hypodopaminergic state, which is restored in a DA replete‐state after dopamimetic treatment [Tessitore et al.,2002]. Moreover, the DA D2 receptor antagonist sultopride and the DA agonist levodopa both attenuate amygdala activation in healthy subjects [Delaveau et al.,2007; Takahashi et al.,2005].

Brain imaging studies combining functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and positron emission tomography (PET) show that emotional processing is associated with striatal and amygdala DA transmission [Kienast et al.,2008a,b; Siessmeier et al.,2006]. DA storage capacity in the amygdala measured with 6‐[18F]fluoro‐L‐DOPA (FDOPA), for example, is positively associated with amygdala BOLD response to aversive stimuli [Kienast et al.,2008a]. Moreover, reduced striatal DRD2/3 availability has been associated with affective disorders and substance abuse, and has been discussed as a vulnerability factor in this context [Denys et al.,2004; Fehr et al.,2008; Schneier et al.,2000,2008; Volkow et al.,1996; Wang et al.,1997].

Previous studies have focused on striatal and amygdala DA transmission. So far, the role of other emotion‐related brain regions, e.g. thalamus and prefrontal cortex (PFC), has not been examined. Yet, both structures are reciprocally connected to the amygdala [Llamas et al.,1977; Mcdonald et al.,1996; Price,2003] and might additionally mediate amygdala response. The connection between medial PFC (mPFC) and basolateral amygdala (BLA) is especially crucial for emotion processing. DA release in the mPFC modulates activity of mPFC neurons via D2‐ and D1‐like receptors expressed on pyramidal cells and GABAergic interneurons [Gaspar et al.,1995; Khan et al.,1998]. D2 receptor activity in the mPFC facilitates BLA‐driven excitation of mPFC pyramidal cells by reducing feedforward inhibition that the BLA normally exerts over mPFC neurons [Floresco and Tse,2007]. Therefore, prefrontal DA levels should influence amygdala response to affective stimuli. In line with this view, own studies investigating genetic variations of the catechol‐O‐methyltransferase (COMT), which metabolizes DA, also indicate a role of prefrontal DA levels in amygdala reactivity [Smolka et al.,2005,2007]. The met158 variant of COMT has a fourth of the activity of the val158 variant and is linked to increased prefrontal DA [Gogos et al.,1998]. Carriers of the met158 low‐activity alleles showed augmented amygdala response to aversive stimuli.

Overall, studies on DA and emotion processing suggest an association between amygdala function and DA neurotransmission in the striatum, frontal cortex, and amygdala as well as extensive anatomical connections between these structures. However, previous studies on DRD2/3 availability and emotion processing are very scarce. We hypothesize that DRD2/3 availability in brain regions related to emotion processing is associated with amygdala response elicited by affective stimuli. To investigate the association between amygdala response to affective stimuli and DRD2/3 availability in brain structures related to emotion processing, we examined 28 healthy males with fMRI and [18F]fallypride (FP) PET. Although our focus is on the amygdala as a structure of central importance for emotion processing, we also explore the influence of DRD2/3 availability on emotion processing in other brain regions. Because smoking affects availability of DRD1 as well as DRD2/3 [Dagher et al.,2001; Fehr et al.,2008], we additionally assessed the effects of nicotine dependence on amygdala reactivity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

The participants of this study were part of a previously published PET study in which the effects of nicotine dependence on D2/D3 receptor availability were investigated [Fehr et al.,2008]. Thirty‐seven male volunteers (19 never‐smokers and 18 nicotine‐dependent smokers) participated in the study after providing informed, written consent according to the declaration of Helsinki. The local ethics committee, the Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices (BfArM), and the Federal Office for Radiation Protection (BfS) approved this study. Participants were recruited by public announcement.

Never‐smokers had consumed no more than 20 cigarettes in their lives. Smokers were smoking a minimum of 15 cigarettes per day within 4 weeks prior to the study and fulfilled criteria for nicotine dependence according DSM IV. The Munich‐Composite International Diagnostic Interview [Wittchen et al.,1998] was used to exclude axis 1 psychiatric disorders. A urine screening test for illicit drugs was used. Participants did not take any medications on a regular basis. They had no current or past physical illness, substance abuse disorders, or any other psychiatric disorders. They had no family history of major psychiatric disorders in first degree relatives. Five never‐smokers and four smokers were excluded from the study because they did not fulfill all of the criteria after thorough screening (i.e., insufficient visual acuity, left‐handedness, ex‐smoker; n = 3), because they were not compliant with study requirements (i.e., in a state of nicotine withdrawal at the time of the fMRI scan and abortion of the fMRI scan; n = 2), or because their imaging data was not utilizable (due to fMRI movement artifacts, teeth implants that led to image distortion, or technical problems with the MRI goggles; n = 4).

Therefore, the final sample consisted of 14 never‐smokers and 14 smokers. All participants were right‐handed males. The age was 30.6 ± 6.5 (mean ± SD) years (smokers: 30.4 ± 8.2; never‐smokers: 30.9 ± 4.5). Smokers were heavily nicotine dependent according to the Fagerstrom test for nicotine dependence [Heatherton et al.,1991] scores of 5.6 ± 1.5. Smoking onset was at the age of 17.3 ± 2.3. They had smoked for 13.1 ± 8.6 years. The mean number of cigarettes per day was 20.5 ± 4.6. The time difference between PET scan and fMRI scan was 34.3 ± 48.5 days with a minimum of 4 days and a maximum of 177 days.

Positron Emission Tomography

PET data acquisition

Striatal and extrastriatal D2/D3 binding were measured using [18F]FP PET. The more commonly used radioligands [11C]raclopride and [123I]IBZM have moderate affinities for DA D2/D3 receptors and therefore permit accurate measurement of receptor levels only in the striatum, which has the highest DA D2/D3 receptor density in the brain [Hall et al.,1988; Kung et al.,1989]. In contrast, [18F]FP has a very high affinity for DA D2/D3 receptors, thereby allowing to quantify levels of striatal as well as extrastriatal DA D2/D3 receptors [Mukherjee et al.,1995,1999]. PET scans were acquired under resting conditions in dimmed ambient light with eyes closed using a Siemens ECAT EXACT scanner (CTI, Knoxville, TN) operating in 3D‐mode [Wienhard et al.,1992]. Images were reconstructed by filtered back projection using a Ramp filter and a Hamming filter (4 mm width). To correct for tissue attenuation, transmission scans were acquired with three rotating 68Ge sources prior to [18F]FP injection. Data acquisition comprised 39 time frames initiated immediately after bolus intravenous injection of 187 ± 19 MBq of [18F]FP. The scan duration increased progressively from 20 s to 10 min, resulting in a total scanning time of 180 min. Further methodological details including synthesis, physiologic behavior, and kinetics of the ligand can be found elsewhere [Siessmeier et al.,2005; Stark et al.,2007].

PET data analysis

Parametric maps of [18F]FP binding potential (BPND) were calculated on a voxel‐wise basis using the simplified reference tissue model [Gunn et al.,1997]. BPND refers to the ratio at equilibrium of specifically bound radioligand to that of nondisplaceable radioligand in tissue (k 3/k 4). The cerebellum was chosen as reference region, since it contains very few D2/3 receptors and shows only a negligible amount of specific binding [Christian et al.,2009; Mukherjee et al.,2002]. Prior to statistical analysis, BPND images were spatially normalized into the MNI space (Montreal Neurological Institute, McGill University, Montreal, Canada) to remove intersubject anatomical variability. For this purpose, integral images (the sum of frames between 4 and 8 min p.i.) were calculated and spatially normalized using SPM99 routines (Wellcome Department of Imaging Neuroscience, London, UK) and a ligand‐specific D2 template. Subsequently, transformation parameters of normalization were applied to respective individual BP images. An isotropic Gaussian filter was used to smooth the spatially normalized images with a full‐width at half‐maximum (FWHM) 12 mm kernel to improve the signal‐to‐noise ratio and to compensate for anatomical variability that was not corrected by SPM's normalization. Smoothing on raw PET prior to kinetic analysis is desirable when images are quantified by a method requiring arterial input function. This is the case, e.g., in Logan graphical analysis. The reference parametric mapping [Gunn,1997] is considered to be less sensitive to noise [Slifstein and Laruelle,2000]. Therefore, we did not smooth the images prior to kinetic analysis. The images were visually inspected for outlier voxels, no such voxels could be found. Our voxelwise modelling approach is in analogy with previously published FP PET studies [Buchsbaum et al.,2006; Christian et al.,2006; Gilbert et al.,2006; Werhahn et al.,2006].

BP values were extracted from the PFC, basal ganglia including the ventral and dorsal striatum (containing nucleus caudate and putamen) and neighboring globus pallidus (in the following referred to as striatum for simplification), the amygdala, and the thalamus. For extraction of prefrontal BPND we created a mask that covered those regions in the PFC that are associated with emotion processing, i.e., the medial, orbital, and medial orbital part of the superior frontal gyrus, the orbital part of the middle and inferior gyri, gyrus rectus, anterior cingulate, and paracingulate gyri using the tool MARINA (masks for region of interest analysis, Bender Institute of Neuroimaging, University of Giessen, Germany). The size of the prefrontal mask was 24,359 voxels (see Fig. 1B for masks). To differentiate functional significances of BPND in prefrontal subregions, we divided the mask into three subregions, the lateral OFC (composed of the orbital part of the SFG and the orbital part of the middle frontal gyrus), the ventromedial PFC (composed of the rectal gyrus and the medial orbital part of the SFG), and the dorsomedial PFC (composed of the anterior cingulate gyrus and the medial part of the SFG). Masks provided by the WFU Pickatlas (Department of Radiology, Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston‐Salem, NC) were used for extraction of BPND from the basal ganglia/striatum including caudate, putamen, and globus pallidus (size of mask: 4,602 voxels); the amygdala (size of mask: 319 voxels); and the thalamus (size of mask: 2,157 voxels). We extracted BPND data of all voxels from the regions of interests (ROIs) and averaged them using Matlab 7.1 (MathWorks, Sherborn, MA).

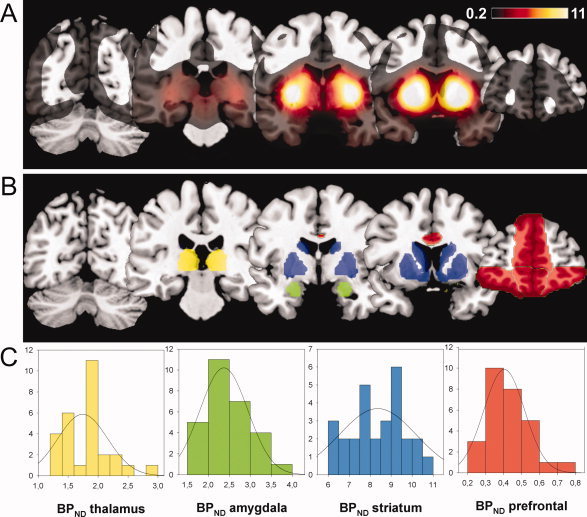

Figure 1.

(A) Mean BPND of all 28 subjects. In the regions of interest (ROIs), mean BPND was highest in the basal ganglia/striatum and lowest in the prefrontal cortex. (B) ROIs from which mean BPND were extracted. ROIs include the amygdala (green); emotion‐related parts of the frontal cortex (red); the basal ganglia/striatum including caudate, putamen, and globus pallidus (blue); and the thalamus (yellow). (C) Distributions of BPND in the ROIs. Mean BPND were normally distributed in all ROIs. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at www.interscience.wiley.com.]

Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Paradigm

Affectively unpleasant, pleasant, and neutral pictures were used to measure neural activity during processing of emotional stimuli. Pictures were taken from the International Affective Picture System (IAPS) [Lang et al.,2008] in which pictures are standardized with respect to valence, arousal, and dominance. Participants were instructed to passively view the stimuli, because even simple rating tasks can alter brain activation pattern [Taylor et al.,2003]. For each category, 40 slides were presented for 2,000 ms using an event‐related design.1 Pictures were arranged in an individually randomized order. The intertrial interval was randomized between two and three acquisition times (i.e., 6.6–9.9 s). During the intertrial interval a fixation cross was presented.

To control for attention, a memory test was conducted following the scan containing 15 previously presented and 15 new pictures. The overall recognition rate was 92.7 ± 6.2% and did not differ between categories or between smokers and never‐smokers.

fMRI data acquisition

Scanning was performed with a 1.5 T whole‐body tomograph (Magnetom VISION; Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) equipped with a standard head coil. For functional imaging, a standard EPI‐Sequence was used [TR (repetition time), 0.6 ms; TA (time for acquisition of a volume), 3,300 ms; TE (echo time), 60 ms; flip angle, 90°]. fMRI scans were obtained from 30 transversal slices, orientated axially parallel to the anterior commissure–posterior commissure line, with a thickness of 4 mm (1 mm gap), a field of view (FOV) of 220 mm, and an in‐plane resolution of 64 × 64 pixels resulting in a voxel size of 3.44 × 3.44 × 5 mm3. For anatomical reference a 3D T1‐weighted magnetization‐prepared rapid gradient echo (MPRAGE) image data set was acquired (TR = 11.4 ms, TE = 4.4 ms, FOV = 256 mm, 162 slices, 1 × 1 × 1 mm3 voxel size, flip angle = 12°).

Images were presented via goggles using MRI Audio/Video Systems (Resonance Technology, Northridge, CA). Task presentation and recording of the behavioral responses was performed using Presentation® software (Version 9.90, Neurobehavioral Systems, Albany, CA).

fMRI data analysis

Data were analyzed with Statistical Parametric Mapping (SPM5) implemented in Matlab 7.1. Prior to data analysis, functional data underwent preprocessing. The first five images were discarded to reduce T1 saturation effects. Data were temporally realigned to minimize temporal differences in slice acquisition. Spatial realignment was performed to correct for head motion over the course of the session. Participants with excessive head motion (>3 mm translation and >3 degrees rotation) were excluded from the analyses. Functional data were normalized to a standard EPI template and resampled with a voxel size of 3 × 3 × 3 mm3. Smoothing was performed using an isotropic Gaussian kernel (12‐mm FWHM).

Statistical analyses of fMRI and PET data

Statistical analyses were performed by modeling the different conditions (pleasant, unpleasant, and neutral pictures) as explanatory variables within the context of the general linear model on a voxel‐by‐voxel basis. We performed a region of interest analysis and restricted our focus of attention to the amygdala, because this brain structure is crucial for emotion processing and its function is known to be modulated by DA. The mean signal change of the amygdala was extracted from the individual contrast images (signal change unpleasant vs. neutral stimuli, and pleasant vs. neutral stimuli) applying the same amygdala mask as for extraction of BPND using Matlab. We calculated one sample t‐tests using SPSS 16.0 to test for significant amygdala activations in response to unpleasant versus neutral and pleasant versus neutral stimuli. Because amygdala signal change evoked by pleasant versus neutral stimuli was not significant (M ± SD: 0.14 ± 0.96; t(27) = 0.75, P = 0.23), further analyses were solely conducted with the contrast unpleasant versus neutral stimuli (see Table IB and Fig. 1B in the Supporting Information for brain regions activated during presentation of pleasant vs. neutral stimuli).

Table I.

Predictive values of prefrontal DRD2/3 availability, striatal DRD2/3 availability, and smoking status on amygdala BOLD response to unpleasant stimuli

| Side | Cluster sizea | MNI coordinates | T max | P FDR‐corr. | P uncorr. | Beta | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x | y | z | |||||||

| Prefrontal [18F]FP BPND (positive correlation) | L | 42 | −27 | −6 | −18 | 3.55 | 0.011 | 0.001 | 0.70 |

| R | 43 | 27 | −9 | −15 | 3.19 | 0.011 | 0.002 | 0.86 | |

| Striatal [18F]FP BPND (negative correlation) | L | 0 | −24 | −3 | −18 | −2.61 | 0.055 | 0.008 | −0.60 |

| R | 0 | 24 | −9 | −9 | −2.43 | 0.055 | 0.011 | −0.58 | |

| Smoking status (smokers < nonsmokers) | R | 49 | 24 | −9 | −15 | 3.08 | 0.023 | 0.003 | 0.56 |

| L | 45 | −24 | −3 | −21 | 2.90 | 0.023 | 0.004 | 0.52 | |

Number of voxels with P ≤ 0.05 FDR‐corrected.

SPSS was used to perform multiple linear regression analyses applying backward elimination (P for entry < 0.05 and for removal >0.1) to select the model that best predicted amygdala BOLD signal change elicited by unpleasant stimuli. (1) Prefrontal BPND, (2) striatal BPND, (3) amygdala BPND, (4) thalamic BPND, (5) smoking status (smoker vs. never‐smoker), and (6) time difference between PET scan and fMRI scan were regressed against amygdala BOLD signal change elicited by unpleasant versus neutral stimuli. To determine if binding potential in prefrontal subregions (ventromedial PFC, dorsomedial PFC, and lateral OFC) differentially influenced amygdala reactivity, we calculated three separate multiple regression analyses applying backward elimination to select the model that best predicted amygdala BOLD signal change to unpleasant pictures. Regressors were the same as in the abovementioned analysis, except that the regressor prefrontal BPND was replaced by BPND in each prefrontal subregion. Associations were regarded as significant if the probability (P) of a Type I error was <0.05.

To investigate the association between brain activation in the amygdala and other regions and the abovementioned predictors at voxel level, we conducted a second level whole brain multiple regression analysis in SPM5. Only those independent variables that best predicted amygdala BOLD signal change were included in the analysis. For our region of interest analysis (amygdala), associations were regarded as significant if the probability (P) of a Type I error was <0.05 (FDR‐corrected) in ten adjacent voxels. For any other brain region, the threshold was set to P < 0.001 (uncorrected) in ten adjacent voxels.

RESULTS

PET Data

Distributions of prefrontal, striatal, amygdala, and thalamic BPND are displayed in Figure 1C. Mean prefrontal BPND values ranged between 0.21 and 0.73 (M = 0.43; SD = 0.12) and differed significantly from 0 [t(27) = 18.75, P < 0.001]. This is in accordance with the data from another study reporting orbitofrontal BPs in the range of 0.2–0.4 [Mukherjee et al.,2002]. BPND was highest in the basal ganglia/striatum (caudate, putamen, and globus pallidus) with mean binding of 8.4 ± 1.25 (M ± SD; range 6.31–10.7). Thalamic BPND was 1.85 ± 0.40 (M ± SD; range 1.29–2.95); BPND in the amygdala was 2.44 ± 0.51 (M ± SD; range 1.67–3.64).

BPND in the PFC was correlated with BPND in the striatum (r = 0.67), in the thalamus (r = 0.72), and in the amygdala (r = 0.74). Striatal BPND was correlated with BPND in the amygdala (r = 0.82) and in the thalamus (r = 0.83). BPND in the amygdala was correlated with thalamic BPND (r = 0.85). BPND did not significantly differ between smokers and nonsmokers.

fMRI Data

Consistent with prior studies [Heinz et al.,2005a; Kienast et al.,2008a], the presentation of unpleasant versus neutral stimuli elicited significant activation in the right and left amygdala (x = 18, y = −6, z = −15, t = 4.31, P = 0.005 FDR‐corrected for volume of interest and x = −15, y = −6, z = −15, t = 3.43, P = 0.015 FDR‐corrected for volume of interest). Mean amygdala BOLD signal change elicited by unpleasant compared to neutral stimuli was 0.42 ± 0.97 [M ± SD; t(27) = 2.26, P = 0.016]. Moreover, unpleasant stimuli elicited significant brain activation in the visual system (fusiform gyrus, middle occipital gyrus, lingual gyrus, calcerine sulcus, superior parietal lobule, and precuneus), PFC (inferior frontal gyrus, medial frontal gyrus, gyrus rectus, middle frontal gyrus, inferior frontal/orbitofrontal gyrus), subcortical structures (thalamus, hippocampus), superior temporal gyrus, and anterior insula (P < 0.05 FDR‐corrected, see Table 1A and Fig. 1A in the Supporting Information).

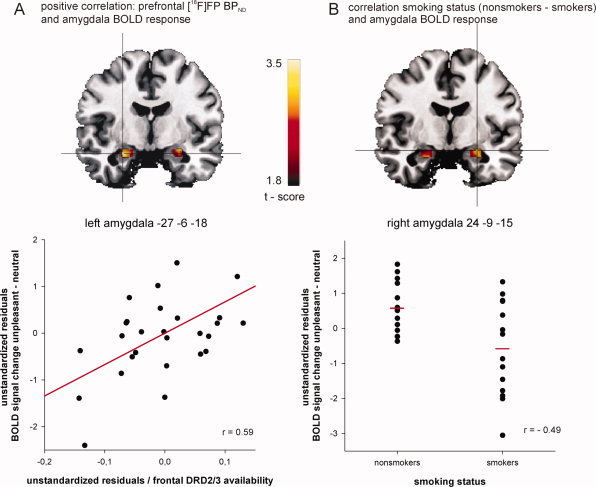

Association Between [18F]fallypride BPND and Amygdala BOLD Response

The model that best predicted amygdala BOLD signal change elicited by unpleasant compared to neutral stimuli included the regressors (1) smoking status, (2) prefrontal BPND, and (3) striatal BPND. There was no collinearity as indicated by the tolerance values between 0.46 and 0.83. This model revealed a significant main effect [F(3,24) = 3.88, P = 0.022] and accounted for 33% of the variation in amygdala response to unpleasant stimuli. Prefrontal BPND significantly predicted amygdala BOLD signal change in response to unpleasant versus neutral stimuli (t = 2.90, beta = 0.72, P = 0.008). Individuals with high prefrontal DA D2/D3 receptor availability showed enhanced amygdala activation to unpleasant stimuli (see Fig. 2A lower panel). Striatal BPND was negatively associated with amygdala activation elicited by unpleasant stimuli (t = −2.07, beta = −0.49, P = 0.049). Furthermore, there was a significant effect of smoking status (t = −2.82, beta = −0.52, P = 0.010). In response to unpleasant stimuli, smokers showed a reduced amygdala BOLD response (see Fig. 2B lower panel). BPND in the amygdala and in the thalamus, as well as the time difference between PET and fMRI experiments, did not explain any variance. Additional multiple regression analyses revealed that BPND in all of the three prefrontal subregions (i.e., ventromedial PFC, dorsomedial PFC and lateral OFC) significantly predicted amygdala BOLD signal change elicited by unpleasant stimuli, although BPND in the ventromedial PFC showed the best fit (ventromedial PFC: t = 3.06, beta = 0.74, P = 0.005; lateral OFC: t = 2.56, beta = 0.63, P = 0.017; dorsomedial PFC: t = 2.45, beta = 0.57, P = 0.022).

Figure 2.

Significant interactions from SPM multiple linear regression analysis: mean prefrontal dopamine receptor availability positively correlates with amygdala BOLD signal change (−27, −6, −18) in response to unpleasant stimuli (panel A). Nonsmokers compared to smokers showed enhanced amygdala BOLD response (24, −9, −15) to unpleasant stimuli (panel B). To illustrate these significant associations, the scatter plot in panel A shows the partial correlation of prefrontal [18F]FP binding potential (BPND) and amygdala BOLD signal change controlling for striatal [18F]FP BPND and smoking status: r = 0.59, P = 0.001. The scatter plot in panel B shows the semipartial correlation of smoking status and amygdala BOLD signal change controlling for prefrontal and striatal [18F]FP BPND: r = 0.49, P = 0.009. Note that unstandardized residuals are displayed. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at www.interscience.wiley.com.]

Multiple regression analysis in SPM confirmed the results of our multiple regression analysis (see Fig. 2A,B upper panels and Table I); however, the negative association of striatal BPND and amygdala BOLD response to unpleasant stimuli did not pass the predefined level of statistical significance (P = 0.055 FDR‐corrected). Furthermore, whole brain analysis revealed that prefrontal as well as striatal BPND predicted activation elicited by unpleasant stimuli, amongst others, in the insula, the superior frontal gyrus, the anterior cingulate gyrus, and the basal ganglia (see Supporting Information Table II).

DISCUSSION

The key finding of our study is that individuals with high prefrontal DRD2/3 availability showed increased activation in brain regions engaged in emotion processing including the amygdala, the insula, and the anterior cingulate gyrus in response to unpleasant stimuli. The association between prefrontal DRD2/3 availability and amygdala reactivity is consistent with studies highlighting the role of DA in regulating the prefrontal–amygdala circuit [Hariri et al.,2002; Inglis and Moghaddam,1999; Tessitore et al.,2002]. High prefrontal DRD2/3 availability in those participants with enhanced amygdala reactivity could indicate low prefrontal DA levels and an attenuated regulation of the amygdala via the PFC, resulting in increased amygdala reactivity to unpleasant stimuli. However, this interpretation is contradictory to genetic studies investigating the influence of the DA degrading COMT enzyme on emotion processing. Those studies found a relationship between high frontal DA levels denoted by the low‐activity met158 allele and enhanced emotional reactivity to aversive stimuli in the limbic system including the amygdala [Smolka et al.,2005]. Furthermore, individuals homozygous for the met158 allele of COMT displayed higher affective responses to pain and higher levels of anxiety [Enoch et al.,2003; Zubieta et al.,2003]. Alternatively, it is possible that heightened prefrontal DRD2/3 availability might indicate a very sensitive DA system that is characterized by increased receptor density and/or reduced DA‐induced receptor internalization leading to an excess of intracellular signaling produced by DA stimulation [Iizuka et al.,2007] rather than low prefrontal DA levels. Analysis of different prefrontal subregions revealed that ventromedial and dorsomedial, as well as lateral orbitofrontal BPND, significantly predicted amygdala reactivity to unpleasant pictures. Apparently, the BPND measure obtained from our analysis is not as independent and region‐specific as fMRI BOLD signal change and therefore not sensitive to distinguish between functionality of different prefrontal subregions.

In addition, our results showed a trend toward enhanced amygdala reactivity to unpleasant stimuli in individuals with low levels of striatal DRD2/3 availability. Previous studies reported increased amygdala reactivity to negative stimuli in patients with major depression, anxiety disorders including social phobia and specific phobia, and alcohol dependence [Etkin and Wager,2007; Gilman and Hommer,2008; Leppanen,2006] as well as in healthy individuals with elevated risk for depression and anxiety‐related temperamental traits [Heinz et al.,2005a; Pezawas et al.,2005]. Although increased amygdala activation has so far not been linked to characteristics of DA neurotransmission in these patient groups, reduced striatal DRD2/3 availability has also been found in individuals with social phobia, and substance dependence including alcohol, nicotine, and opiate dependence [Denys et al.,2004; Fehr et al.,2008; Schneier et al.,2000,2008; Volkow et al.,1996; Wang et al.,1997] but not in depressed patients [D'haenen and Bossuyt,1994; Hirvonen et al.,2008; Parsey et al.,2001].

Especially in the context of the development of substance dependence, reduced striatal DA receptor availability has been discussed as a vulnerability factor [Nader et al.,2006], whereas high levels of DA D2 receptors were suggested to serve as a protective factor against alcoholism [Volkow et al.,2006]. Enhanced emotional reactivity modulated by dopaminergic neurotransmission could be a mechanism that predisposes individuals to the development of psychiatric conditions associated with emotion regulation (e.g., anxiety disorder or depression) and/or to self‐administration of substances. In the latter case, the person might thereby regulate the pronounced responsiveness toward affective and potentially stressful information. In line with this, in our study, we found an attenuated amygdala response to unpleasant stimuli in smokers when controlling for frontal and striatal DA receptor availability. Thus, smoking might “normalize” enhanced responsiveness to aversive information. This is consistent with studies reporting beneficial effects of nicotine on affect and mood [Gilbert et al.,2004; Laje et al.,2001; Picciotto,1998] as well as the finding that cigarette smoke inhibits monoamine oxidase (MAO), thereby acting as an antidepressant [Fowler et al.,1996a,b]. Explorative correlation analyses revealed a significant negative correlation between CO level and right amygdala reactivity toward unpleasant stimuli (r = −0.53, P = 0.025). Although this finding should not be overestimated because of the small sample size (14 smokers), heavier smokers exhibited lower amygdala reactivity. Varying frequency of smoking among smokers could also explain higher variability in the amygdala response toward unpleasant stimuli in smokers than in never‐smokers (as seen in Fig. 2B lower panel). Moreover, it is possible that smoking as a mode to decrease reactivity to aversive information may not be effective in all individuals, as other factors, i.e. genetic predispositions, may come to play. Overall, we can only speculate whether this compensational effect is due to the acute effects of cigarette smoking or nicotine, a protective genetic predisposition, changes accompanying chronic nicotine consumption, or a combination of these factors. Future studies need to separately investigate these components. For example, to evaluate acute nicotine effects on emotion processing, future imaging studies could assess the effects of nicotine on nonsmokers.

While Kienast et al. [2008a] reported an association between amygdala reactivity to aversive stimuli and DA storage capacity in these nuclei, we did not observe an association between functional amygdala reactivity and amygdala DRD2/3 availability. However, DA storage capacity and BPND measure two different facets of DA function and are not necessarily correlated. In line with this, prior work demonstrated that (striatal) [18F]DOPA DA synthesis capacity and DRD2/3 availability measured with [18F]DMFP BPND seem to be two independent measures of DA function [Heinz et al.,2005b; Kienast et al.,2008b].

As previous research has almost exclusively focused on DA transmission in the striatum, where D2/D3 receptors are most abundant, studies on extrastriatal DA transmission are scarce. More research on extrastriatal DRD2/3 is necessary to better understand its influence on the processing of negative but also positive emotional information.

A limitation of the present study is the time lag between the PET and the fMRI scan, which varied considerably across participants ranging from less than a week to almost 6 months. Although we do not expect time‐specific influences on DA receptor availability and no influence of the time interval between PET and fMRI measurements on amygdala reactivity was observed, a shorter time interval would have been preferable. Moreover, we solely included male participants in this study. Future studies need to determine whether our findings can be generalized to females. Furthermore, from our findings one cannot establish the nature of the altered DRD2/3 availability. It may result from interindividual differences in a competitive displacement of [18F]FP by DA, a DA‐promoted receptor internalization in terms of a temporary translocation of D2 receptors from the cell surface to intracellular compartments [Ginovart et al.,2004], or a combination of both. In support of the first view, displacement PET studies found that [18F]FP was sensitive to endogenous variations of DA concentrations in both striatal and extrastriatal regions in humans [Riccardi et al.,2006,2008].

CONCLUSION

Overall, our results indicate an association between prefrontal DRD2/3 availability and brain activation in the amygdala and other limbic brain regions during processing of visual unpleasant stimuli. Healthy subjects with higher prefrontal DRD2/3 availability seem to be more responsive toward aversive and stressful information. Through this mechanism, dopaminergic neurotransmission might influence vulnerability for affective and anxiety disorders. Smoking might to some extent compensate this augmented reactivity to unpleasant stimuli, which could explain high smoking rates among individuals with mental disorders.

Supporting information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article.

Supplementary Figure 1

Supplementary Table 1: Brain regions activated during presentation of (A) unpleasant vs. neutral stimuli and (B) pleasant vs. neutral stimuli (p ≤ 0.05 FDR‐corrected).

Supplementary Table 2: Predictive values of prefrontal DRD2/3 availability, striatal DRD2/3 availability, and smoking status on whole brain BOLD responses to unpleasant stimuli (p ≤ 0.001 uncorrected)

Acknowledgements

We thank Christoph Strasser for his critical reading of the manuscript. This article is part of the PhD thesis of Andrea Kobiella.

Footnotes

IAPS catalog numbers were 1710, 1720, 1811, 2389, 4598, 4599, 4641, 4650, 4660, 4687, 5260, 5450, 5470, 5480, 5621, 5622, 5623, 5626, 5629, 5700, 5910, 8021, 8030, 8031, 8034, 8040, 8116, 8130, 8161, 8180, 8185, 8190, 8200, 8210, 8280, 8370, 8420, 8500, 8531, 9156 for pleasant pictures, 2352_2, 2900, 3010, 3015, 3030, 3051, 3060, 3071, 3080, 3110, 3130, 3150, 3160, 3170, 3261, 3350, 3400, 3500, 3530, 6230, 6250, 6260, 6313, 6510, 6530, 6560, 6570, 6838, 7380, 9006, 9250, 9421, 9520, 9560, 9570, 9630, 9800, 9830, 9910, 9920 for unpleasant pictures; and 2880, 5120, 5130, 5500, 5533, 5534, 5731, 7000, 7002, 7004, 7006, 7009, 7010, 7020, 7030, 7031, 7034, 7040, 7050, 7060, 7080, 7090, 7100, 7110, 7140, 7150, 7160, 7170, 7175, 7180, 7185, 7205, 7224, 7233, 7234, 7490, 7491, 7500, 7705, 7950 for neutral pictures.

REFERENCES

- Buchsbaum MS, Christian BT, Lehrer DS, Narayanan TK, Shi B, Mantil J, Kemether E, Oakes TR, Mukherjee J ( 2006): D2/D3 dopamine receptor binding with [F‐18]fallypride in thalamus and cortex of patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 85: 232–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christian BT, Lehrer DS, Shi B, Narayanan TK, Strohmeyer PS, Buchsbaum MS, Mantil JC ( 2006): Measuring dopamine neuromodulation in the thalamus: Using [F‐18]fallypride PET to study dopamine release during a spatial attention task. Neuroimage 31: 139–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christian BT, Vandehey NT, Fox AS, Murali D, Oakes TR, Converse AK, Nickles RJ, Shelton SE, Davidson RJ, Kalin NH ( 2009): The distribution of D2/D3 receptor binding in the adolescent rhesus monkey using small animal PET imaging. Neuroimage 44: 1334–1344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dagher A, Bleicher C, Aston JA, Gunn RN, Clarke PB, Cumming P ( 2001): Reduced dopamine D1 receptor binding in the ventral striatum of cigarette smokers. Synapse 42: 48–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaveau P, Salgado‐Pineda P, Micallef‐Roll J, Blin O ( 2007): Amygdala activation modulated by levodopa during emotional recognition processing in healthy volunteers: A double‐blind, placebo‐controlled study. J Clin Psychopharmacol 27: 692–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denys D, van der WN, Janssen J, De Geus F, Westenberg HG ( 2004): Low level of dopaminergic D2 receptor binding in obsessive–compulsive disorder. Biol Psychiatry 55: 1041–1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'haenen HA, Bossuyt A ( 1994): Dopamine D2 receptors in depression measured with single photon emission computed tomography. Biol Psychiatry 35: 128–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enoch MA, Xu K, Ferro E, Harris CR, Goldman D ( 2003): Genetic origins of anxiety in women: A role for a functional catechol‐O‐methyltransferase polymorphism. Psychiatr Genet 13: 33–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etkin A, Wager TD ( 2007): Functional neuroimaging of anxiety: A meta‐analysis of emotional processing in PTSD, social anxiety disorder, and specific phobia. Am J Psychiatry 164: 1476–1488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fehr C, Yakushev I, Hohmann N, Buchholz HG, Landvogt C, Deckers H, Eberhardt A, Klager M, Smolka MN, Scheurich A, Dielentheis T, Schmidt LG, Rosch F, Bartenstein P, Grunder G, Schreckenberger M ( 2008): Association of low striatal dopamine d2 receptor availability with nicotine dependence similar to that seen with other drugs of abuse. Am J Psychiatry 165: 507–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floresco SB, Tse MT ( 2007): Dopaminergic regulation of inhibitory and excitatory transmission in the basolateral amygdala–prefrontal cortical pathway. J Neurosci 27: 2045–2057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler JS, Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Pappas N, Logan J, MacGregor R, Alexoff D, Shea C, Schlyer D, Wolf AP, Warner D, Zezulkova I, Cilento R ( 1996a): Inhibition of monoamine oxidase B in the brains of smokers. Nature 379: 733–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler JS, Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Pappas N, Logan J, Shea C, Alexoff D, MacGregor RR, Schlyer DJ, Zezulkova I, Wolf AP ( 1996b): Brain monoamine oxidase A inhibition in cigarette smokers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93: 14065–14069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaspar P, Bloch B, Le Moine C ( 1995): D1 and D2 receptor gene expression in the rat frontal cortex: Cellular localization in different classes of efferent neurons. Eur J Neurosci 7: 1050–1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert DG, Sugai C, Zuo Y, Eau CN, McClernon FJ, Rabinovich NE, Markus T, Asgaard G, Radtke R ( 2004): Effects of nicotine on brain responses to emotional pictures. Nicotine Tob Res 6: 985–996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert DL, Christian BT, Gelfand MJ, Shi B, Mantil J, Sallee FR ( 2006): Altered mesolimbocortical and thalamic dopamine in Tourette syndrome. Neurology 67: 1695–1697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilman JM, Hommer DW ( 2008): Modulation of brain response to emotional images by alcohol cues in alcohol‐dependent patients. Addict Biol 13: 423–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginovart N, Wilson AA, Houle S, Kapur S ( 2004): Amphetamine pretreatment induces a change in both D2‐receptor density and apparent affinity: A [11C]raclopride positron emission tomography study in cats. Biol Psychiatry 55: 1188–1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gogos JA, Morgan M, Luine V, Santha M, Ogawa S, Pfaff D, Karayiorgou M ( 1998): Catechol‐O‐methyltransferase‐deficient mice exhibit sexually dimorphic changes in catecholamine levels and behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 9991–9996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunn RN, Lammertsma AA, Hume SP, Cunningham VJ ( 1997): Parametric imaging of ligand–receptor binding in PET using a simplified reference region model. Neuroimage 6: 279–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall H, Kohler C, Gawell L, Farde L, Sedvall G ( 1988): Raclopride, a new selective ligand for the dopamine‐d2 receptors. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 12: 559–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hariri AR, Mattay VS, Tessitore A, Fera F, Smith WG, Weinberger DR ( 2002): Dextroamphetamine modulates the response of the human amygdala. Neuropsychopharmacology 27: 1036–1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerstrom KO ( 1991): The Fagerstrom test for nicotine dependence: A revision of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. Br J Addict 86: 1119–1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinz A, Braus DF, Smolka MN, Wrase J, Puls I, Hermann D, Klein S, Grusser SM, Flor H, Schumann G, Mann K, Buchel C ( 2005a): Amygdala–prefrontal coupling depends on a genetic variation of the serotonin transporter. Nat Neurosci 8: 20–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinz A, Siessmeier T, Wrase J, Buchholz HG, Grunder G, Kumakura Y, Cumming P, Schreckenberger M, Smolka MN, Rosch F, Mann K, Bartenstein P ( 2005b): Correlation of alcohol craving with striatal dopamine synthesis capacity and D‐2/3 receptor availability: A combined [18F]DOPA and [18F]DMFP PET study in detoxified alcoholic patients. Am J Psychiatry 162: 1515–1520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirvonen J, Karlsson H, Kajander J, Markkula J, Rasi‐Hakala H, Nagren K, Salminen JK, Hietala J ( 2008): Striatal dopamine D‐2 receptors in medication‐naive patients with major depressive disorder as assessed with [C‐11]raclopride PET. Psychopharmacology 197: 581–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iizuka Y, Sei Y, Weinberger DR, Straub RE ( 2007): Evidence that the BLOC‐1 protein dysbindin modulates dopamine D2 receptor internalization and signaling but not D1 internalization. J Neurosci 27: 12390–12395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inglis FM, Moghaddam B ( 1999): Dopaminergic innervation of the amygdala is highly responsive to stress. J Neurochem 72: 1088–1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan ZU, Gutierrez A, Martin R, Penafiel A, Rivera A, De La CA ( 1998): Differential regional and cellular distribution of dopamine D2‐like receptors: An immunocytochemical study of subtype‐specific antibodies in rat and human brain. J Comp Neurol 402: 353–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kienast T, Hariri AR, Schlagenhauf F, Wrase J, Sterzer P, Buchholz HG, Smolka MN, Grunder G, Cumming P, Kumakura Y, Bartenstein P, Dolan RJ, Heinz A ( 2008a): Dopamine in amygdala gates limbic processing of aversive stimuli in humans. Nat Neurosci 11: 1381–1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kienast T, Siessmeier T, Wrase J, Braus DF, Smolka MN, Buchholz HG, Rapp M, Schreckenberger M, Rosch F, Cumming P, Gruender G, Mann K, Bartenstein P, Heinz A ( 2008b): Ratio of dopamine synthesis capacity to D2 receptor availability in ventral striatum correlates with central processing of affective stimuli. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 35: 1147–1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kung HF, Pan S, Kung MP, Billings J, Kasliwal R, Reilley J, Alavi A ( 1989): In vitro and in vivo evaluation of [123I]IBZM: A potential CNS D‐2 dopamine receptor imaging agent. J Nucl Med 30: 88–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laje RP, Berman JA, Glassman AH ( 2001): Depression and nicotine: Preclinical and clinical evidence for common mechanisms. Curr Psychiatry Rep 3: 470–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang PJ, Bradley MM, Cuthbert BN ( 2008): The International Affective Picture System (IAPS): Affective Ratings of Pictures and Instruction Manual. Technical Report A‐8. Gainesville, FL: University of Florida. [Google Scholar]

- Leppanen JM ( 2006): Emotional information processing in mood disorders: A review of behavioral and neuroimaging findings. Curr Opin Psychiatry 19: 34–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llamas A, Avendano C, Reinoso‐Suarez F ( 1977): Amygdaloid projections to prefrontal and motor cortex. Science 195: 794–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mcdonald AJ, Mascagni F, Guo L ( 1996): Projections of the medial and lateral prefrontal cortices to the amygdala: A Phaseolus vulgaris leucoagglutinin study in the rat. Neuroscience 71: 55–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee J, Yang ZY, Das MK, Brown T ( 1995): Fluorinated benzamide neuroleptics. 3. Development of (S)‐N‐[(1‐allyl‐2‐pyrrolidinyl)methyl]‐5‐(3‐[F‐18] fluoropropyl)‐2,3‐dimethoxybenzamide as an improved dopamine D‐2 receptor tracer. Nucl Med Biol 22: 283–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee J, Yang ZY, Brown T, Lew R, Wernick M, Ouyang X, Yasillo N, Chen CT, Mintzer R, Cooper M ( 1999): Preliminary assessment of extrastriatal dopamine D‐2 receptor binding in the rodent and nonhuman primate brains using the high affinity radioligand, 18F‐fallypride. Nucl Med Biol 26: 519–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee J, Christian BT, Dunigan KA, Shi B, Narayanan TK, Satter M, Mantil J ( 2002): Brain imaging of 18F‐fallypride in normal volunteers: Blood analysis, distribution, test–retest studies, and preliminary assessment of sensitivity to aging effects on dopamine D‐2/D‐3 receptors. Synapse 46: 170–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nader MA, Morgan D, Gage HD, Nader SH, Calhoun TL, Buchheimer N, Ehrenkaufer R, Mach RH ( 2006): PET imaging of dopamine D2 receptors during chronic cocaine self‐administration in monkeys. Nat Neurosci 9: 1050–1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsey RV, Oquendo MA, Zea‐Ponce Y, Rodenhiser J, Kegeles LS, Pratap M, Cooper TB, Van Heertum R, Mann JJ, Laruelle M ( 2001): Dopamine D‐2 receptor availability and amphetamine‐induced dopamine release in unipolar depression. Biol Psychiatry 50: 313–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pezawas L, Meyer‐Lindenberg A, Drabant EM, Verchinski BA, Munoz KE, Kolachana BS, Egan MF, Mattay VS, Hariri AR, Weinberger DR ( 2005): 5‐HTTLPR polymorphism impacts human cingulate–amygdala interactions: A genetic susceptibility mechanism for depression. Nat Neurosci 8: 828–834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picciotto MR ( 1998): Common aspects of the action of nicotine and other drugs of abuse. Drug Alcohol Depend 51: 165–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price JL ( 2003): Comparative aspects of amygdala connectivity. Ann N Y Acad Sci 985: 50–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riccardi P, Li R, Ansari MS, Zald D, Park S, Dawant B, Anderson S, Doop M, Woodward N, Schoenberg E, Schmidt D, Baldwin R, Kessler R ( 2006): Amphetamine‐induced displacement of [18F] fallypride in striatum and extrastriatal regions in humans. Neuropsychopharmacology 31: 1016–1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riccardi P, Baldwin R, Salomon R, Anderson S, Ansari MS, Li R, Dawant B, Bauernfeind A, Schmidt D, Kessler R ( 2008): Estimation of baseline dopamine D2 receptor occupancy in striatum and extrastriatal regions in humans with positron emission tomography with [18F] fallypride. Biol Psychiatry 63: 241–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salgado‐Pineda P, Delaveau P, Blin O, Nieoullon A ( 2005): Dopaminergic contribution to the regulation of emotional perception. Clin Neuropharmacol 28: 228–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneier FR, Liebowitz MR, Abi‐Dargham A, Zea‐Ponce Y, Lin SH, Laruelle M ( 2000): Low dopamine D(2) receptor binding potential in social phobia. Am J Psychiatry 157: 457–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneier FR, Martinez D, Abi‐Dargham A, Zea‐Ponce Y, Simpson HB, Liebowitz MR, Laruelle M ( 2008): Striatal dopamine D(2) receptor availability in OCD with and without comorbid social anxiety disorder: Preliminary findings. Depress Anxiety 25: 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siessmeier T, Zhou Y, Buchholz HG, Landvogt C, Vernaleken I, Piel M, Schirrmacher R, Rosch F, Schreckenberger M, Wong DF, Cumming P, Grunder G, Bartenstein P ( 2005): Parametric mapping of binding in human brain of D2 receptor ligands of different affinities. J Nucl Med 46: 964–972. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siessmeier T, Kienast T, Wrase J, Larsen JL, Braus DF, Smolka MN, Buchholz HG, Schreckenberger M, Rosch F, Cumming P, Mann K, Bartenstein P, Heinz A ( 2006): Net influx of plasma 6‐[18F]fluoro‐L‐DOPA (FDOPA) to the ventral striatum correlates with prefrontal processing of affective stimuli. Eur J Neurosci 24: 305–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slifstein M, Laruelle M ( 2000): Effects of statistical noise on graphic analysis of PET neuroreceptor studies. J Nucl Med 41: 2083–2088. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smolka MN, Schumann G, Wrase J, Grusser SM, Flor H, Mann K, Braus DF, Goldman D, Buchel C, Heinz A ( 2005): Catechol‐O‐methyltransferase val158met genotype affects processing of emotional stimuli in the amygdala and prefrontal cortex. J Neurosci 25: 836–842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smolka MN, Buhler M, Schumann G, Klein S, Hu XZ, Moayer M, Zimmer A, Wrase J, Flor H, Mann K, Braus DF, Goldman D, Heinz A ( 2007): Gene–gene effects on central processing of aversive stimuli. Mol Psychiatry 12: 307–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark D, Piel M, Hubner H, Gmeiner P, Grunder G, Rosch F ( 2007): In vitro affinities of various halogenated benzamide derivatives as potential radioligands for non‐invasive quantification of D(2)‐like dopamine receptors. Bioorg Med Chem 15: 6819–6829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi H, Yahata N, Koeda M, Takano A, Asai K, Suhara T, Okubo Y ( 2005): Effects of dopaminergic and serotonergic manipulation on emotional processing: A pharmacological fMRI study. Neuroimage 27: 991–1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SF, Phan KL, Decker LR, Liberzon I ( 2003): Subjective rating of emotionally salient stimuli modulates neural activity. Neuroimage 18: 650–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tessitore A, Hariri AR, Fera F, Smith WG, Chase TN, Hyde TM, Weinberger DR, Mattay VS ( 2002): Dopamine modulates the response of the human amygdala: A study in Parkinson's disease. J Neurosci 22: 9099–9103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Fowler JS, Logan J, Hitzemann R, Ding YS, Pappas N, Shea C, Piscani K ( 1996): Decreases in dopamine receptors but not in dopamine transporters in alcoholics. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 20: 1594–1598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Begleiter H, Porjesz B, Fowler JS, Telang F, Wong C, Ma Y, Logan J, Goldstein R, Alexoff D, Thanos PK ( 2006): High levels of dopamine D2 receptors in unaffected members of alcoholic families: Possible protective factors. Arch Gen Psychiatry 63: 999–1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang GJ, Volkow ND, Fowler JS, Logan J, Abumrad NN, Hitzemann RJ, Pappas NS, Pascani K ( 1997): Dopamine D2 receptor availability in opiate‐dependent subjects before and after naloxone‐precipitated withdrawal. Neuropsychopharmacology 16: 174–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werhahn KJ, Landvogt C, Klimpe S, Buchholz HG, Yakushev I, Siessmeier T, Muller‐Forell W, Piel M, Rosch F, Glaser M, Schreckenberger M, Bartenstein P ( 2006): Decreased dopamine D2/D3‐receptor binding in temporal lobe epilepsy: An [18F]fallypride PET study. Epilepsia 47: 1392–1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wicker B, Keysers C, Plailly J, Royet JP, Gallese V, Rizzolatti G ( 2003): Both of us disgusted in My insula: The common neural basis of seeing and feeling disgust. Neuron 40: 655–664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wienhard K, Eriksson L, Grootoonk S, Casey M, Pietrzyk U, Heiss WD ( 1992): Performance evaluation of the positron scanner ECAT EXACT. J Comput Assist Tomogr 16: 804–813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittchen HU, Lachner G, Wunderlich U, Pfister H ( 1998): Test–retest reliability of the computerized DSM‐IV version of the Munich‐Composite International Diagnostic Interview (M‐CIDI). Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 33: 568–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zubieta JK, Heitzeg MM, Smith YR, Bueller JA, Xu K, Xu Y, Koeppe RA, Stohler CS, Goldman D ( 2003): COMT val158met genotype affects mu‐opioid neurotransmitter responses to a pain stressor. Science 299: 1240–1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article.

Supplementary Figure 1

Supplementary Table 1: Brain regions activated during presentation of (A) unpleasant vs. neutral stimuli and (B) pleasant vs. neutral stimuli (p ≤ 0.05 FDR‐corrected).

Supplementary Table 2: Predictive values of prefrontal DRD2/3 availability, striatal DRD2/3 availability, and smoking status on whole brain BOLD responses to unpleasant stimuli (p ≤ 0.001 uncorrected)