Abstract

We report the complete genome sequence of Zymomonas mobilis ZM4 (ATCC31821), an ethanologenic microorganism of interest for the production of fuel ethanol. The genome consists of 2,056,416 base pairs forming a circular chromosome with 1,998 open reading frames (ORFs) and three ribosomal RNA transcription units. The genome lacks recognizable genes for 6-phosphofructokinase, an essential enzyme in the Embden-Meyerhof-Parnas pathway, and for two enzymes in the tricarboxylic acid cycle, the 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase complex and malate dehydrogenase, so glucose can be metabolized only by the Entner-Doudoroff pathway. Whole genome microarrays were used for genomic comparisons with the Z. mobilis type strain ZM1 (ATCC10988) revealing that 54 ORFs predicted to encode for transport and secretory proteins, transcriptional regulators and oxidoreductase in the ZM4 strain were absent from ZM1. Most of these ORFs were also found to be actively transcribed in association with ethanol production by ZM4.

Supplementary information

The online version of this article (doi:10.1038/nbt1045) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Main

Growing environmental concerns over the use and depletion of nonrenewable energy resources, together with the recent price increases and instabilities in the international oil markets have stimulated an increasing interest in the use of fermentation processes for the large-scale production of alternative fuels such as ethanol. As such, ethanol-producing microorganisms, such as the Gram-negative bacterium Z. mobilis, have potential for the production of fuel ethanol.

Z. mobilis, which is used in the tropics to produce pulque and alcoholic palm wines, uses the Entner-Doudoroff (ED) pathway to metabolize glucose, which results in only 1 mole of ATP being produced per mole of glucose1. The potential advantages of using Z. mobilis for ethanol production include: (i) its high and specific rates of sugar uptake and ethanol production, (ii) its production of ethanol at yields close to the theoretical maximum with relatively low biomass formation, (iii) its high ethanol tolerance of up to 16% (vol/vol) and (iv) its facility for genetic manipulation2,3,4,5,6. However, wild strains of Z. mobilis can use only glucose, fructose and sucrose as carbon substrates, so recent research has focused on the development of recombinant strains capable of using pentose sugars7,8 for the conversion of cheaper lignocellulosic hydrolysates to ethanol. Improved mutants9,10,11 as well as the application of metabolic flux analysis, site-directed mutagenesis, specific gene deletion/insertion and metabolic engineering for strain developlment12,13 have also been reported. A physical map of Z. mobilis ZM4 genome and the ribosomal transcriptional unit have been previously reported14,15. In the current paper, the features of the complete sequence of the Z. mobilis ZM4 genome are presented and genomic characters are compared with those of another Z. mobilis strain, ZM1.

Results

General features

The complete genome of Z. mobilis ZM4 consists of a single circular chromosome of 2,056,416 bp with an average G+C content of 46.33% (Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1 online). The 1,998 predicted coding ORFs cover 87% of the genome, and each ORF has an average length of 898 bp. Among these, 1,346 (67.4%) could be assigned putative functions, 258 (12.9%) were matched to conserved hypothetical coding sequences of unknown function and the remaining 394 (19.7%) showed no similarities to known genes. The functions of the predicted ORFs were categorized by comparison with the COG database (Table 2).

Table 1.

General features of the Z. mobilis genome

| Length (bp) | 2,056,416 |

| G+C content (%) | 46.33 |

| Open reading frames | |

| Coding region of genome (%) | 87 |

| Total number of predicted ORFs | 1,998 |

| ORFs with assigned function | 1,346 (67.4%) |

| Conserved hypothetical protein | 258 (12.9%) |

| ORFs with no database match | 394 (19.7%) |

| RNA element | |

| Stable RNA (percent of genome) | 0.84% |

| 16S, 23S and 5S rRNA genes | 3 |

| tRNA | 51 |

Table 2.

Functional categories of predicted genes in Z. mobilis genome

| COG categories | No. of genes |

|---|---|

| Information storage and processing | |

| J. Translation, ribosomal structure and biogenesis | 141 |

| K. Transcription | 85 |

| L. DNA replication, recombination and repair | 87 |

| Cellular processes | |

| D. Cell cycle control, mitosis and meiosis | 20 |

| V. Defense mechanisms | 25 |

| T. Signal transduction mechanisms | 60 |

| M. Cell wall/membrane biogenesis | 120 |

| N. Cell motility | 40 |

| U. Intracellular trafficking and secretion | 47 |

| O. Post-translational modification, protein turnover, chaperones | 81 |

| Metabolism | |

| C. Energy production and conversion | 85 |

| G. Carbohydrate transport and metabolism | 76 |

| E. Amino acid transport and metabolism | 171 |

| F. Nucleotide transport and metabolism | 54 |

| H. Coenzyme transport and metabolism | 96 |

| I. Lipid transport and metabolism | 53 |

| P. Inorganic ion transport and metabolism | 93 |

| Q. Secondary metabolites biosynthesis, transport and catabolism | 32 |

| Poorly characterized | |

| R. General function prediction only | 198 |

| S. Function unknown | 104 |

| Not in COG | 539 |

| All genes were classified according to the COG classification. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/COG/ | |

Of the 0.84% of the genome that encodes stable RNA, 51 genes encode transfer RNAs, corresponding to 42 different isoacceptor-tRNA species. Of these ribosomal RNA transcriptional units, rrnA is located at coordinate 140,000, rrnB at 360,000 and rrnC at 520,000, all three being transcribed in the same predicted direction of replication.

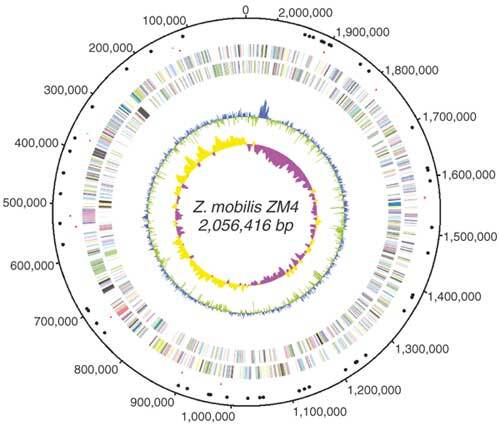

The replication origin predicted by calculating GC skew (G−C/G+C) values16 (Fig. 1) closely coincided with a 656-bp region containing one copy of a likely site (5′-GATCTNTTNTTTT-3′) for initial DNA unwinding, and eight copies of probable sites (5′-TTATNCANA-3′) for DnaA binding. We also found that genes such as parA and parB, which are involved in chromosome partitioning, and gidA and gidB, the glucose-inhibited division genes, were also located near the origin, which has often been observed in other bacterial genomes17.

Figure 1. Overall features of the Z. mobilis ZM4 genome.

The putative origin of replication is around 0 kb. The outer scale indicates the coordinates in base pairs. The distribution of genes is shown on the first two rings within the scale according to the direction of the reading frame. The locations of rRNA and tRNA genes are shown by green dots and black dots, respectively. Putative transposases are shown by red dots. The next circle shows GC content values. Cyan and green colors indicate positive and negative signs, respectively. The central circle shows GC-skew values (G−C/G+C) of the third bases of codons measured over the genome. Yellow and purple colors denote positive and negative signs, respectively. The window size was 10,000 nucleotides and the step size was 1,000 nucleotides.

Comparison with other sequenced genomes

Comparison of the Z. mobilis ZM4 ORFs (amino acid sequences) with those of other organisms revealed that 768 out of 1,668 ORFs listed in the COG database have the closest similarity to the corresponding ORFs of Novosphingobium aromaticivorans (Supplementary Table 2 online) in line with a previous phylogenetic study on Z. mobilis ZM4 based on the 16S ribosomal RNA sequence, where it was found that Z. mobilis ZM4 belonged to the Sphingomonas spp. group15. In particular, the ORFs classified into COG category J (translation, ribosomal structure and biogenesis) and category D (cell division and chromosome partitioning) showed high similarities to N. aromaticivorans. In contrast, only 2 out of 40 total ORFs classified into the COG category N (cell motility) and 5 out of 25 in category V (defense mechanisms) matched ORFs of N. aromaticivorans.

General metabolism

Z. mobilis uses glucose, fructose and sucrose anaerobically through the ED pathway, leading to the production of ethanol and CO2 (ref. 1). Analysis of the Z. mobilis genome sequence revealed the determinants of hexose-metabolizing enzymes such as invertase (ZMO0375, ZMO0942), levansucrase (ZMO0374), glucokinase (ZMO0369), glucose-6-phosphate isomerase (ZMO1212) and glucose-fructose oxidoreductase (ZMO0689) that would enable Z. mobilis to use sucrose, fructose and glucose as well as probably mannose, raffinose and sorbitol. However, there are no obvious genes for using lactose, maltose or cellobiose.

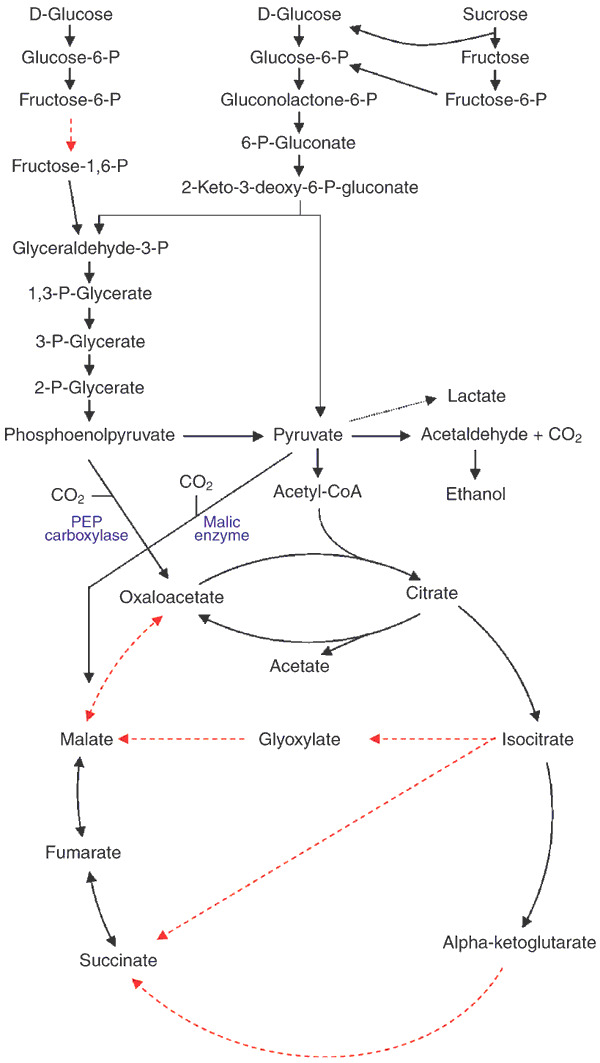

In the ED pathway, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (zwf, ZMO0367) oxidizes glucose-6-phosphate to 6-phosphonolactone. The lactone is dehydrated to 6-phosphogluconate by lactonase (ZMO1478). 6-phosphogluconate is dehydrated by 6-phosphogluconate dehydratase (edd, ZMO0368) to yield 2-keto-3-deoxy-6-phosphogluconate (KDPG). KDPG aldolase (eda, ZMO0997) cleaves KDPG to form pyruvate and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate (Fig. 2). Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate is then metabolized via the triose phosphate common to the Embden-Meyerhof-Parnass (EMP) pathway to yield ethanol and carbon dioxide. All the genes for all of the enzymes of the EMP pathway except 6-phosphofructokinase are present in Z. mobilis (Fig. 2). The zwf and edd genes are clustered with glf (ZMO0366; encodes facilitated diffusion protein for glucose) and glk (ZMO0369; glucokinase), whereas eda is separately located. This contrasts with Escherichia coli, in which zwf, edd and eda are closely linked although regulation of the zwf and edd-eda operon is independent17. By using the ED pathway instead of the EMP pathway, Z. mobilis yields only 1 mole of ATP per mole of fermented hexose, and produces ethanol at a theoretical yield of 2 moles/mole of substrate. Rapid production and high yield of ethanol as the only sugar fermentation product can be attributed to the presence of pyruvate decarboxylase (ZMO1360), an enzyme not frequently observed in bacteria, and two highly specific alcohol dehydrogenases (ZMO1236, ZMO1596).

Figure 2. Central metabolic pathways of sugars.

Enzymes missing from Z. mobilis are represented by red dotted arrows.

The genes encoding two enzymes in the tricarboxylic acid cycle—the 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase complex and malate dehydrogenase—were not found. However, all the key building blocks, including oxaloacetate, malate, fumarate and succinate have been detected by means of high-performance liquid chromatography, and Z. mobilis is known to be able to synthesize all essential amino acids except for lysine and methionine. These results strongly indicate that other metabolic pathways are involved in producing oxaloacetate, malate, fumarate and succinate. Oxaloacetate can be produced from phosphoenolpyruvate and CO2 by phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase (ZMO1496) or citrate lyase (ZMO0487: citrate ↔ oxaloacetate + acetate). Malate can be synthesized by pyruvate carboxylation with malic enzyme (ZMO1955). Fumarate can be produced by fumarate dehydratase (ZMO1307). However, evidence for an alternative metabolic pathway for succinate production, such as the glyoxylate cycle, has not yet been found.

Although most genes for the pentose phosphate pathway are missing, all genes encoding enzymes necessary for the synthesis of phosphoribosyl-pyrophosphate, a precursor for purine/pyrimidine metabolism, are present. We also identified all genes required for the de novo biosynthesis of RNA and DNA. Z. mobilis possesses a complete set of genes for the sulfate reduction pathway as well as all the genes required for the synthesis of all amino acids, except for one gene in the lysine (yfdZ) and one gene in the methionine (metB) pathways. For vitamins, all genes for riboflavin and folate synthesis and most genes for thiamin, ubiquinone, NAD+ and pyridoxal are present. The absence of genes for pantothenate and biotin biosynthesis genes is in accordance with the known nutritional requirement of Z. mobilis for these vitamins.

Transport systems and motility

We recognized 180 genes encoding transport-related membrane proteins, on the basis of a search of the Transport Protein Database (http://tcdb.ucsd.edu/index.php). The largest number (83) of these proteins were electrochemical potential-driven transporters (class 2), and included 20 involved in iron metabolism, 13 multi-drug resistance exporters, three members of the resistance nodulation cell-division family, eight permeases of the major facilitator superfamily, seven cation transporters, seven amino acid transporters, three nucleoside permeases and four sugar transporters. There are several ORFs for the sec-independent protein secretion pathway and others for the TonB-ExbB-ExbD/TolA-TolQ-TolR (TonB) family of auxiliary proteins for energization of outer membrane receptor–mediated active transport systems. The second most numerous class (55) contained primary active transporters (class 3), including 41 members of the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter superfamily. There were five ORFs for the sec-dependent general secretory pathway, two for type III secretory pathway proteins and four for the type IV secretory pathway. The third largest class (14 members) was the channels/pores (class 1), consisting of five capsule polysaccharide export proteins and two carbohydrate (glucose)-facilitated diffusion proteins. The four remaining classes were group translocators (class 4; 4 ORFs), transport electron carriers (class 5; 3 ORFs), accessory factors involved in transport (class 8; 1 ORF) and incompletely characterized transport systems (class 9; 20 ORFs).

The flagellar cluster consists of 32 ORFs (ZMO0602–ZMO0652: flgABCDEFGHIJKL, flhAB, fliDEFGHIKLMNPQRS, motAB) encoding flagellar structure proteins, motor proteins and biosynthesis proteins. Classical chemotaxis signal transduction genes (cheABDRWY) and methyl-accepting chemotaxis genes (mcpAJ), similar to those in E. coli, were present.

Oxidative stress and respiration

Z. mobilis is not an obligatory but a facultative anaerobe, implying that there must be a defense mechanism against oxidative stress. The most well-known reduction-oxidation cycling machinery is the glutathione system. Both glutathione reductase (ZMO1211) and glutathione synthase (ZMO1913) are present, as well as a Gamma-glutamylcysteine synthetase (ZMO1556). Genes encoding a catalase (ZMO0928), an iron-dependent superoxide dismutase (Fe-SOD; ZMO1060) and two kinds of peroxidases (ZMO1136, ZMO1573), which are thought to be responsible for protection from the toxic effects of superoxide and hydrogen peroxide in most aerobic organisms, are also present.

In addition to the genes that respond to oxidative stress, the genome contained several genes related to the electron transport system such as the Fe-S-cluster redox enzyme (ZMO1032), cytochrome b (ZMO0957), cytochrome c1 (ZMO0958), cytochrome c-type biogenesis proteins (ZMO1252–1256), electron transfer flavoprotein (ZMO1479, ZMO1480) and a ubiquinone biosynthesis protein (ZMO1189, ZMO1669). Genes for electron donor and receptor modules such as NADH dehydrogenase (ZMO1113) NADH:flavin oxidoreductase (ZMO1885), NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase complex (ZMO1809–1814), nitroreductase (ZMO0678) and fumarate reductase (ZMO0569) were also found. However, genes for cytochrome o and cytochrome d, which use oxygen as a final electron acceptor, appeared to be absent.

It was reported that Z. mobilis has a respiratory electron transport chain19 and that it shows elevated molar growth yield during exponential aerobic growth20. Relative to anaerobic conditions, this leads to a decrease in the yield of ethanol and an accumulation of other less reduced metabolites such as acetaldehyde, acetone and acetate21,22. These results indicate that some NADH is oxidized in the respiratory chain with the simultaneous participation of the alcohol dehydrogenase reaction in aerobic culture conditions.

Stress adaptation

Protein denaturation and aggregation, resulting from exposure to heat or other stresses such as ethanol, are severe problems for cells, and are combated by induction of highly conserved heat shock proteins, whose function is to remove or refold the damaged cellular proteins23. Z. mobilis, an efficient ethanol producer, exhibits very high ethanol tolerance3. The Z. mobilis contains ORFs for the complete sets of heat shock–responsive molecular chaperones, such as DnaK (ZMO0660), DnaJ (ZMO0661, ZMO1069, ZMO1545, ZMO1546, ZMO1690) and GrpE (ZMO0016) of the HSP-70 chaperone complex, GroES (ZMO1928; HSP-10), GroEL (ZMO1929; HSP-60) and HSP-33 (ZMO0410). ATP-dependent heat shock–responsive proteases, such as HslVU (ZMO0246, ZMO0247) and Clp (ZMO0948, ZMO0949, ZMO1424), were also found. As in the well-known E. coli system23, genes for alternative sigma factors, sigma-32 (σ32; ZMO0749) and sigma-E (σE; ZMO1404), for the pertinent responses against various stresses are present. It is known that sigma-32 of E. coli induces a 'classic' set of chaperones, proteases and other heat shock proteins, thereby playing a central role in heat shock responses, whereas sigma-E induces periplasmic protease, chaperone and sigma-32 factor by specific extracytoplasmic stress. It is also well known that the induction of sigma-32 factor is turned on when E. coli cells grown at 30 °C are shifted to 42 °C, whereas proteins encoded by the sigma-E regulon are rapidly induced when E. coli cells are exposed to a more extreme temperature (e.g., 50 °C) or 10% ethanol23. We suppose that sigma-E plays a key role in resisting high ethanol conditions in Z. mobilis. We also found genes for a sigma-E positive regulator (ZMO1842) and a transcriptional regulator of heat shock genes (ZMO0015), two tight regulators of heat shock gene expression.

The appropriate controls of gene expression are carried out by a combination of basic transcriptional machineries, including RNA polymerase and sigma factors. Genes for other sigma factors, σ70 (rpoD; ZMO1623), σ54 (rpoN; ZMO0274), and σ28 (fliA; ZMO0626) were also found in the genome of Z. mobilis. We also identified 54 transcriptional activators and repressors.

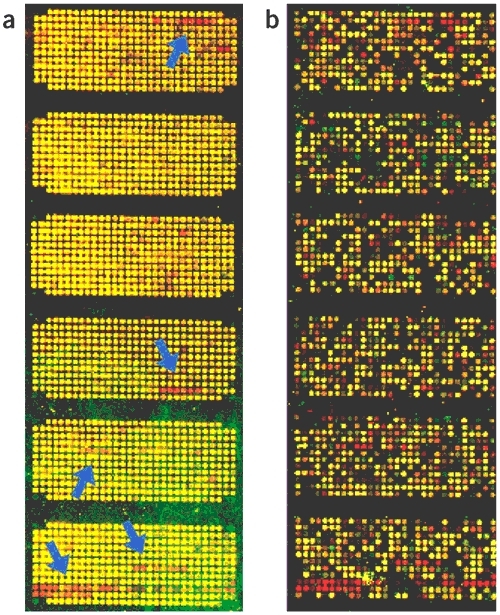

Higher G+C-content genes found only in strain ZM4

To compare the Z. mobilis ZM4 genome with the unsequenced type strain (ZM1: ATCC10988) of Z. mobilis, labeled ZM1 and ZM4 genomic DNA were cohybridized with DNA microarrays containing probes for all the ORFs of Z. mobilis ZM4. It was found that most of the probes on the microarray hybridized equally with both labeled genomic DNAs (Fig. 3a). In addition, the two strains showed similar patterns of gene expression in microarray analysis of cultures grown under various growth stages (data not shown). Probably the overall genome structure of ZM1 and ZM4 is very similar.

Figure 3. Comparison of genome structure and expression profiles between Z. mobilis ZM1 and ZM4.

(a) Cohybridization of cy3-labeled ZM1 genomic DNA (green) and cy5-labeled ZM4 genomic DNA (red) on a Z. mobilis microarray. Arrows indicate extra sequences in strain ZM4. (b) Cohybridization of cy3-labeled ZM1 cDNA (green) and cy5-labeled ZM4 cDNA (red) on a Z. mobilis microarray. Most ORFs in the extra sequence of strain ZM4 (same locations that arrows indicate on panel a) were actively expressed (red spot). RNAs were isolated at exponential growth phase.

However, it is interesting to note that strain ZM4 contains sequences that are absent from ZM1. These sequences consist of 54 genes that are clustered separately in five regions. Among the products of the 54 ORFs, there were four kinds of membrane transport proteins, and four kinds of proteins involved in a type IV secretory system, an oxidoreductase related to short chain alcohol dehydrogenase and several transcriptional regulators (Table 3). Two genes, bcbG (ZMO1299) and bcbE (ZMO1300), encoding capsular polysaccharide biosynthesis proteins, were also peculiar to strain ZM4. One of the five clusters, spanning from 1,984,100 nt to 2,009,434 nt (25.3 kb), contains 25 ORFs and shows a higher G+C content (61.0%) (Fig. 1) than the average (46.3%) for the full genome of ZM4. The 25.3-kb sequence contains some interesting ORFs: ZMO1930 for phage-related integrase, ZMO1941 for conjugal transfer TraF protein, ZMO1954 conjugal transfer TrbL protein, and ZMO1933 and ZMO1934 for type I restriction-modification enzyme S and M subunits, respectively.

Table 3.

Complete list of additional 54 ORFs in ZM4

| ZMO0045 | hypothetical protein |

| ZMO0046 | hypothetical protein |

| ZMO0047 | conserved hypothetical protein, transporter |

| ZMO0048 | hypothetical protein |

| ZMO0049 | hypothetical protein |

| ZMO0050 | transcriptional regulator, LysR family |

| ZMO0051 | hypothetical protein |

| ZMO0052 | cyanate permease |

| ZMO0053 | beta-ketoadipate enol-lactone hydrolase, putative |

| ZMO0054 | transcriptional regulator, MarR family |

| ZMO0055 | permeases, predicted |

| ZMO1299 | capsular polysaccharide biosynthesis protein, bcbG |

| ZMO1300 | capsular polysaccharide biosynthesis protein, bcbE |

| ZMO1301 | conserved hypothetical protein |

| ZMO1302 | lipoate-protein ligase B |

| ZMO1459 | transporter, putative |

| ZMO1460 | thiosulfate sulfurtransferase (rhodanese) family protein |

| ZMO1461 | conserved hypothetical protein |

| ZMO1462 | conserved hypothetical protein |

| ZMO1463 | TonB-dependent receptor, probable |

| ZMO1856 | putative transport protein |

| ZMO1857 | transcriptional regulator, probable |

| ZMO1858 | hypothetical protein |

| ZMO1859 | regulator of pathogenicity factors, carbohydrate-selective porin |

| ZMO1860 | similar to nodulin 21 |

| ZMO1861 | dioxygenases related to 2-nitropropane dioxygenase |

| ZMO1862 | hypothetical protein |

| ZMO1863 | putative phosphatase |

| ZMO1864 | transposase |

| ZMO1930 | phage-related integrase |

| ZMO1931 | conserved hypothetical protein |

| ZMO1932 | hypothetical protein |

| ZMO1933 | type I restriction-modification enzyme, S subunit |

| ZMO1934 | type I restriction-modification enzyme, M subunit |

| ZMO1935 | conserved hypothetical protein |

| ZMO1936 | conserved hypothetical protein |

| ZMO1937 | conserved hypothetical protein |

| ZMO1938 | conserved hypothetical protein |

| ZMO1939 | ATPases involved in chromosome partitioning |

| ZMO1940 | conserved hypothetical protein |

| ZMO1941 | type IV secretory pathway, conjugal transfer TraF transmembrane protein |

| ZMO1942 | type IV secretory pathway, VirD2 components (relaxase) |

| ZMO1943 | type IV secretory pathway, VirD2 components (relaxase) |

| ZMO1944 | transcriptional regulatory protein |

| ZMO1945 | predicted epimerase, PhzC/PhzF homolog |

| ZMO1946 | oxidoreductase (short-chain alcohol dehydrogenases) |

| ZMO1947 | translational inhibitor protein |

| ZMO1948 | conserved hypothetical protein |

| ZMO1949 | NAD(P)H quinone oxidoreductase, putative |

| ZMO1950 | aspartate/tyrosine/aromatic aminotransferase |

| ZMO1951 | demethylmenaquinone methyltransferase |

| ZMO1952 | 3-methyl-2-oxobutanoate hydroxymethyltransferase; PanB, probable |

| ZMO1953 | hypothetical protein |

| ZMO1954 | type IV secretory pathway, VirB10, conjugal transfer TrbL transmembrane protein |

Most of the additional 54 ORFs in ZM4 were actively transcribed during the exponential growth phase, when ethanol is vigorously produced (Fig. 3b). Global expression profiles of the ZM1 and ZM4 strains were analyzed in a sample taken when half of the glucose (50 g/l) in the medium had been consumed and the data showed that a total of 294 ORFs were upregulated more than twofold in ZM4 compared to ZM1, whereas 153 ORFs were expressed more than twice in ZM1 (Supplementary Tables 3 and 4 online).

It has been reported that strain ZM4 is more tolerant of higher alcohol concentration than the type strain ZM1 and that ZM4 shows higher specific rates for growth, ethanol production and glucose uptake5,24. Perhaps some of the genes peculiar to ZM4 and actively expressed at the higher glucose concentration will prove to be good target genes for constructing recombinant strains that ferment ethanol with higher productivity.

Discussion

Analysis of the complete sequence of the Z. mobilis ZM4 genome reveals why this is one of the most powerful ethanol-producing microbes described, and suggests potential means to improve the yield and rate of ethanol production. Because Z. mobilis produces only one mole of ATP per mol of glucose via the ED pathway, Z. mobilis requires almost twice as much glucose as microbes that use the EMP pathway to produce equivalent amounts of ATP. The higher rate for glucose utilization and ethanol production are also supported by the fact that pyruvate decarboxylase and alcohol dehydrogenases are very highly expressed in Z. mobilis.

The absence of 6-phosphoglucokinase and the consequent dependence of Z. mobilis on the ED pathway raises interesting questions about the evolution of carbohydrate metabolism. The ED pathway is active in most Gram-negative bacteria and many other microorganisms including some archeabacteria25. The ubiquity of the ED pathway suggests that it is of far greater importance in nature than was previously recognized and indeed an essay on the evolution of glycolytic pathways suggested that the ED pathway predates the EMP pathway26. Although it is also possible that Z. mobilis is not able to use the EMP pathway as a result of the loss of the gene encoding 6-phosphoglucokinase, considering the genome size and relatively simple metabolic pathways present in Z. mobilis, it is more likely that the EMP pathway present in other microorganisms is the result of acquiring the 6-phosphoglucokinase gene.

The absence of two genes for the tricarboxylic acid cycle, the 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase complex and malate dehydrogenase, suggests the existence of alternative pathways to the tricarboxylic acid cycle. Because essential metabolites for cell growth are provided from the tricarboxylic acid cycle, this provides an explanation for the low biomass formation of Z. mobilis compared with other microorganisms in which the tricarboxylic acid cycle is actively operating5.

The observation that Z. mobilis ZM4 contains extra DNA sequences encoding for a total of 54 ORFs, compared to the genome of the type strain ZM1, raises questions about the origin as well as the role of these ORFs. Given that 25 ORFs in these high G+C-content DNA sequences show very high identity with some genes found in phages, and that there is little sequence homology with genes from other bacteria, the possibility exists that the higher G+C content of the additional DNA sequences may have been horizontally transferred from phages. Plasmid exchange is another possible route, because the 3-kb sequence in the additional DNA sequence exhibits substantial homologous regions with the sequence of Ralstonia solanacearum that encodes conjugal proteins TraF and TraL. Transposon-mediated gene transfer is also a possibility considering that the sequences encoding TraF and TraL are also homologous with Ralstonia oxalatica transposon Tn4371.

Among the 54 predicted ORFs, four ORFs that encode transport proteins or permeases, and two genes for NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase (ZMO1949) and oxidoreductase (short-chain alcohol dehydrogenases; ZMO1946) were found to be very highly expressed. It is quite likely that these genes contribute to the higher rates of glucose uptake and ethanol production in the ZM4 strain. Two genes encoding capsular carbohydrate synthesis enzymes were also found to be actively expressed in the ZM4, and it is possible that they may contribute to resistance against osmotic pressure at the high concentration of glucose media and ethanol produced during fermentation. Thus, it is plausible that several of the characteristics of ZM4 that make it attractive as an ethanol producer may be attributable to DNA acquired comparatively recently.

Methods

Sequencing and assembly.

Genomic DNA from Z. mobilis ZM4 strain ATCC 31821 was sequenced using whole genome random shotgun methods27. Mechanically sheared 2-kb and 10-kb DNA fragments were isolated, inserted into pUC18 and cloned. Template preparation reactions were done using standard protocols. DNA sequencing reactions were carried out using PE BigDye Terminator chemistry, and sequencing ladders were analyzed on PE 3700 automated DNA sequencers. Approximately 40,000 reads with PHRED scores_20 were generated, providing a 14-fold genome coverage. These sequences were assembled by using the PHRED_PHRAP_CONSED software package28 (http://www.phrap.org/). Both ends of 292 fosmid clones with an average insert size of 40 kb were also sequenced, providing a validation check of the final assembly. Sequencing gaps were closed by primer walking on gap-spanning clones and combinatorial PCR-assisted contig extension29.

Genome annotation.

ORFs were predicted with the Glimmer software30, and functional annotation of predicted ORFs was carried out by an alignment search tool (Blastx) with a nonreviewed set database. Further analyses such as Pfam and COG (Clusters of Orthologous Genes)31 were carried out to find homologous protein domains and compare protein sequences between species.

Designing and spotting of oligonucleotides for microarrays.

We designed 50-mer oligonucleotide probes representing each Z. mobilis ORF, as follows: melting temperatures were normalized within 2 °C; the G+C content of designed oligonucleotide probes was restricted to 46 ± 2% matching the 46.33% G+C content of Z. mobilis; 'no sequence homology' to other regions of the genome was restricted to a maximum of 35 bp, with no exact sequence matches of more than 15 bp32. The 2,112 oligonucloetide probes and 48 control probes, whose concentrations were normalized to 50 μM (pmole/μl) in 50% DMSO, were spotted on CMT-GAP aminosilane-coated glass slides according to the order of the ORFs in the genome.

Labeling of genomic DNA and RNA.

Genomic DNAs isolated from Z. mobilis strains ZM1 and ZM4 were fluorescently labeled with random hexamers and either Cy3-labeled dCTPs or, Cy5-labeled dCTPs respectively, using the Klenow fragment of DNA polymerase. Total RNA was extracted using an RNeasy kit (Qiagen) with the RNA stabilizing solution, RNAlater (Ambion). We labeled 50 μg of total RNA from strain ZM1 with Cy3-labeled dCTPs, and 50 μg of total RNA from strain ZM4 was labeled with Cy5-labeled dCTPs, using reverse transcriptase (Superscript II; Invitrogen) with random hexamers33.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The sequence reported in this paper has been deposited in GenBank with accession number AE008692.

Microarray data.

Raw data files of microarray experiment are available at http://www.macrogen.com/zymomonas/microarray and EBI ArrayExpress DB with accession number E-MEXP-217.

Note: Supplementary information is available on the Nature Biotechnology website.

Supplementary information

Annotation of Z. mobilis genome (PDF 327 kb)

Distribution of ORFs with closest similarity (PDF 91 kb)

Overexpressed ORFs more than twofold in strain ZM4 (PDF 34 kb)

Overexpressed ORFs more than twofold in strain ZM1 (PDF 25 kb)

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to Peter L. Rogers and Keith Chater for thoughtful advice and discussions throughout the experimentation and manuscript preparation. H.S.K. would especially like to thank President Y.S. Song, for lending the automatic DNA sequencer Licor. This work was supported by an IMT-2000 grant from the Korean Ministry of Information and Communication and the Korean Ministry of Commerce, Industry and Energy [00016103]. J.S.L., S.J.J., H.W.U., H.J.L., S.J.O. and J.Y.K. were supported by a BK21 Research Fellowship from the Korean Ministry of Education and Human Resources Development.

Accession codes

Accessions

GenBank/EMBL/DDBJ

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Footnotes

Jeong-Sun Seo and Hyonyong Chong: These authors contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Jeong-Sun Seo, Email: jeongsun@macrogen.com.

Hyen Sam Kang, Email: khslab@snu.ac.kr.

References

- 1.Swings J, De Ley J. The biology of Zymomonas. Bacteriol. Rev. 1977;41:1–46. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.41.1.1-46.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rogers PL, Lee KJ, Tribe DE. Kinetics of alcohol production by Zymomonas mobilis at high sugar concentrations. Biotechnol. Lett. 1979;1:165–170. doi: 10.1007/BF01388142. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee KJ, Tribe DE, Rogers PL. Ethanol production by Zymomonas mobilis in continuous culture at high glucose concentration. Biotechnol. Lett. 1979;1:421–426. doi: 10.1007/BF01388079. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee KJ, Lefebvre M, Tribe DE, Rogers PL. High productivity ethanol fermentations with Zymomonas mobilis using continuous cell recycle. Biotechnol. Lett. 1980;2:487–492. doi: 10.1007/BF00129544. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee KJ, Skotnicki ML, Tribe DE, Rogers PL. Kinetic studies on a highly productive strain of Zymomonas mobilis. Biotechnol. Lett. 1980;2:339–344. doi: 10.1007/BF00138666. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rogers PL, Lee KJ, Skotnicki ML, Tribe DE. Ethanol production by Zymomonas mobilis. Adv. Biochem. Eng. 1982;23:37–84. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang M, Eddy C, Deanda K, Finkelstein M, Picataggio S. Metabolic engineering of a pentose metabolism pathway in ethanologenic Zymomonas mobilis. Science. 1995;267:240–243. doi: 10.1126/science.267.5195.240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deanda K, Zhang M, Eddy C, Picataggio S. Development of an arabinose-fermenting Zymomonas mobilis strain by metabolic pathway engineering. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1996;62:4465–4470. doi: 10.1128/AEM.62.12.4465-4470.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zaldivar J, Nielsen J, Olsson J. Fuel ethanol production from lignocellulose: a challenge for metabolic engineering and process integration. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2001;56:17–34. doi: 10.1007/s002530100624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ingram LO, et al. Enteric bacterial catalysts for fuel ethanol production. Biotechnol. Prog. 1999;15:855–866. doi: 10.1021/bp9901062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ingram LO, et al. Metabolic engineering of bacteria for ethanol production. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 1998;58:204–214. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0290(19980420)58:2/3<204::AID-BIT13>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hatzimanikatis V, Emmerling M, Sauer U, Bailey JE. Application of mathematical tools for metabolic design of microbial ethanol production. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 1998;58:154–161. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0290(19980420)58:2/3<154::AID-BIT7>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cornish-Bowden A, Cardenas ML. From genome to cellular phenotype–a role for metabolic flux analysis? Nat. Biotechnol. 2000;18:267–268. doi: 10.1038/73696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kang HL, Kang HS. A physical map of the genome of ethanol fermentative bacterium Zymomonas mobilis ZM4 and localization of genes on the map. Gene. 1998;206:223–228. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1119(97)00589-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee JS, Jin SJ, Kang HS. Molecular organization of the ribosomal RNA transcription unit and the phylogenetic study of Zymomonas mobilis ZM4. Mol. Cells. 2001;11:68–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lobry JR. Asymmetric substitution patterns in the two DNA strands of bacteria. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1996;13:660–665. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a025626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lewin B. Genes V. 1994. Creating the replication forks at an origin; pp. 594–597. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moat AG, Foster JW, Spector MP. Microbial physiology. 2002. Central pathways of carbohydrate metabolism; pp. 351–367. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Strohdeicher M, Neuss B, Bringeer-Meyer S, Sahm H. Electron transport chain of Zymomonas mobilis. Interaction with the membrane-bound glucose dehydrogenase and identification of ubiquinone 10. Arch. Microbiol. 1990;154:536–543. doi: 10.1007/BF00248833. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zikmanis P, Kruce R, Auzina L. An elevation of the molar growth yield of Zymomonas mobilis during aerobic exponential growth. Arch. Microbiol. 1997;167:167–171. doi: 10.1007/s002030050430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Viikari L. Carbohydrate metabolism in Zymomonas. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 1988;7:237–261. doi: 10.3109/07388558809146603. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kalnenieks U, Galinina N, Toma MM, Poole RK. Cyanide inhibits respiration yet stimulates aerobic growth of Zymomonas mobilis. Microbiology. 2000;146:1259–1266. doi: 10.1099/00221287-146-6-1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yura T. Regulation of heat shock response in bacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 1993;47:321–350. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.47.100193.001541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Skotnicki ML, Lee KJ, Tribe DE, Rogers PL. Genetic alteration of Zymomonas mobilis for ethanol production. Basic Life Sci. 1982;19:271–290. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4684-4142-0_22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Conway T. The Entner-Doudoroff pathway: history, physiology, and molecular biology. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 1992;9:1–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1992.tb05822.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Romano AH, Conway T. Evolution of carbohydrate metabolic pathways. Res. Microbiol. 1996;147:448–455. doi: 10.1016/0923-2508(96)83998-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fleischmann RD, et al. Whole-genome random sequencing and assembly of Haemophilus influenzae Rd. Science. 1995;269:496–512. doi: 10.1126/science.7542800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gordon D, Abajian C, Green P. Consed: a graphical tool for sequence finishing. Genome Res. 1998;8:195–202. doi: 10.1101/gr.8.3.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tettelin H, Radune D, Kasif S, Khouri H, Salzberg SL. Optimized multiplex PCR: efficiently closing a whole-genome shotgun sequencing project. Genomics. 1999;62:500–507. doi: 10.1006/geno.1999.6048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Delcher AL, et al. Improved microbial gene identification with GLIMMER. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:4636–4641. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.23.4636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tatusov RL, Galperin MY, Natale DA, Koonin EV. The COG database: a tool for genome-scale analysis of protein functions and evolution. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:33–36. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kane MD, et al. Assessment of the sensitivity and specificity of oligonucleotide (50 mer) microarrays. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:4552–4557. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.22.4552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Richmond CS, Glasner JD, Mau R, Jin H, Blattner FR. Genome-wide expression profiling in Escherichia coli K-12. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:3821–3835. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.19.3821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Annotation of Z. mobilis genome (PDF 327 kb)

Distribution of ORFs with closest similarity (PDF 91 kb)

Overexpressed ORFs more than twofold in strain ZM4 (PDF 34 kb)

Overexpressed ORFs more than twofold in strain ZM1 (PDF 25 kb)