Abstract

With event‐related functional MRI (fMRI) and with behavioral measures we studied the brain processes underlying the acquisition of native language literacy. Adult dialect speakers were scanned while reading words belonging to three different conditions: dialect words, i.e., the native language in which subjects are illiterate (dialect), German words, i.e., the second language in which subjects are literate, and pseudowords. Investigating literacy acquisition of a dialect may reveal how novel readers of a language build an orthographic lexicon, i.e., establish a link between already available semantic and phonological representations and new orthographic word forms. The main results of the study indicate that a set of regions, including the left anterior hippocampal formation and subcortical nuclei, is involved in the buildup of orthographic representations. The repeated exposure to written dialect words resulted in a convergence of the neural substrate to that of the language in which these subjects were already proficient readers. The latter result is compatible with a “fast” brain plasticity process that may be related to a shift of reading strategies. Hum Brain Mapp, 2007. © 2006 Wiley‐Liss, Inc.

Keywords: literacy acquisition, native language, second language, event‐related fMRI, left anterior hippocampal formation, brain plasticity, word reading

INTRODUCTION

Reading, the fundamental process of literacy acquisition, is an ability acquired through explicit schooling. Many factors, such as phonological processing, contribute to its acquisition [Swan and Goswami,1997; Habib,2000]. According to information‐processing models, reading involves a series of cognitive processes that include the visual analysis of letters and letter strings, the processing of word forms, the conversion of graphemic word forms into corresponding phonological word forms, and the access to the corresponding semantic representation. According to dual models of reading, single‐word reading may be carried out in two distinct ways: through a “direct” lexical and an “indirect” grapheme‐to‐phoneme conversion (GPC) pathway [Coltheart et al.,1993]. The “lexical” route is involved in converting the orthographic form of a word into its corresponding phonological word form, with or without intermediary access to the semantic representation of the word. This lexical route is involved in reading irregular and regular words, which are represented in the lexicon. On the other hand, the “indirect” or GPC pathway is responsible for reading pseudowords (i.e., nonexisting but pronounceable words, e.g., gint) that lack not only semantic reference, but also an entry in the orthographic and phonological lexicon. If real words are read via this route, words with regular GPC (e.g., mint) are correctly processed, but those with irregular GPC (e.g., pint) result in regularization errors.

It has been theorized that the GPC route is crucially involved in the acquisition of reading skills [Frith,1985; Scarborough,1990]. A key to the process of learning to read is the ability to identify the different phonological components of a word and to associate them with their orthographic counterparts. Phonological awareness is considered a crucial requirement for this process. This assumption is supported by the fact that many children with learning disabilities are deficient in their ability to process phonological information, i.e., to relate the letters of the alphabet to the sounds of language [Demonet et al.,2004; Lyon,1995]. In general, the processes of phonological awareness, including phonemic awareness, must be explicitly taught. Hence, according to the dual‐route theory of reading, normally developing infants go through a stage of using the GPC route, whereas adults use the direct lexical route for words they know [Ellis and Young,1988]. This has led to the hypothesis that there is a developmental shift from the GPC route to the lexical route. According to the framework of serial processing models, experienced readers rely almost exclusively on the faster and more efficient whole‐word (lexical) reading strategy, while a more analytical rule‐based form of reading (sublexical) involving GPC remains essential for the acquisition of novel words [Joubert et al.,2004]. In stage accounts, experienced readers activate both routes in parallel but the direct route results in faster output [Coltheart et al.,1993]. Alternative accounts emphasize the incremental acquisition of individual word representations, rather than discrete stages of acquisition [Perfetti,1992]. Both approaches share the assumption that phonological decoding is a key component of the acquisition of word‐specific orthographic representations, a proposal known as the “bootstrapping hypothesis” [Share,1995]. According to this hypothesis, attempting to decode an unfamiliar or novel word is a form of self‐teaching that allows the reader to acquire an orthographic representation for the word.

The neural bases of reading processes in adults have been investigated by means of functional neuroimaging. Since the landmark study of Peterson et al. [1988], these studies have outlined that single‐word reading is carried out through a prevalent left‐hemispheric network comprising frontal, temporal, occipito‐temporal, and parietal areas, involved in mapping orthographic representations into phonological and semantic representations [Fiez and Petersen,1998; Paulesu et al.,2000; Posner et al.,1999; Price,2000; Price et al.,1996; Price and Mechelli,2005; Tan et al.,2005]. Reading‐related visual information is transferred via a ventral pathway linking striate and extrastriate cortices to the so‐called “word form area” located in the left fusiform gyrus, where the interplay between orthographic and phonological codes may take place [Dehaene et al.,2001,2002; but see also Price and Devlin,2003]. In addition, a dorsal pathway including the left inferior parietal lobule, superior temporal gyrus, and the inferior frontal gyrus is engaged in retrieving and assembling phonological codes and in associating these to semantic representations [Shaywitz et al.,2002]. However, this reading‐related neural network may be constrained by the orthographic system of the language [Bolger et al.,2005]. For instance, in the case of Chinese logographic reading, brain activity within the left inferior frontal gyrus and left superior temporal gyrus is less prominent than in the case of alphabetic languages [Tan et al.,2005], whereas the left middle frontal gyrus (BA 9) and the posterior part of the left inferior parietal lobule are consistently activated [Tan et al.,2001,2003,2005].

While the neural basis of reading can thus be considered reasonably well known, much less is known about the neurological underpinnings of reading acquisition.

Several investigations have supported the crucial role of the phonological loop as a “language learning device,” supporting reading acquisition [Baddeley et al.,1998]. This position predicts a central role of the left perisylvian areas, which have been related to the phonological component of working memory [Paulesu et al.,1993]. This idea is supported by the results of a recent functional MRI (fMRI) investigation in a cross‐sectional population of subjects whose age ranged from 6–22 years [Turkeltaub et al.,2003]. The study reported two distinct patterns of neural changes associated with the maturation of reading skills. By comparing the brain activity of more experienced readers to that of younger readers, a prevalent brain activity in the left middle temporal and inferior frontal gyrus was found in adult readers. This change was paralleled by decreased activity in right inferotemporal areas. Even if very informative on the neural differences that may exist between younger and more experienced readers, the study of Turkeltaub et al. [2003] provides only indirect evidence on the neural structures involved in the early stages of literacy acquisition, characterized by the development of GPC mechanisms. Given the difficulties inherent to the longitudinal investigation of the changes in brain activity associated with learning to read in children, several other strategies have been employed in adult subjects.

One possibility is asking adult subjects to learn to read an unknown language. For example, Lee et al. [2003] investigated the changes in brain activity associated with learning to read Korean words by Japanese subjects. The main locus of learning‐associated changes was the left angular gyrus, which was similarly activated by Japanese and Korean words only when the subjects had learned the Korean words; this change was paralleled by a reduction in occipital activation, suggesting that the unfamiliar words were initially treated as visual objects, and only with learning became proper linguistic stimuli. Given the characteristics of the writing system used in this study, the authors propose that the left angular gyrus is involved in the association of syllabographic symbols to phonology. In other words, this learning effect appears to be quite specific for the orthographic systems used in the study.

Another strategy is to employ artificial language learning paradigms in adults. Such paradigms have been successfully employed to investigate grammar acquisition [Opitz and Friederici,2003,2004]. These studies have indicated the existence of learning‐related changes in brain activity. In particular, they have indicated a transition from a similarity‐based neural learning system in the left anterior hippocampus to a language‐related processing system in the left prefrontal cortex. The left hippocampus is also involved in the case of novel lexical learning (linking pseudowords to pictures of objects) [Breitenstein et al.,2005]. The associative learning was linearly related to a decrease in activation of the left hippocampus and fusiform gyrus, while the increasing proficiency was correlated with activation of the left inferior parietal lobule. Moreover, learning proficiency was predicted by decreasing suppression of hippocampal activity in each subject.

The present study attempts to investigate the neural correlates of reading acquisition in a more natural setting (i.e., by using the native language). To this aim, we studied the brain processes underlying literacy acquisition in a dialect.1 Dialects are considered languages lacking an orthographic lexicon but, contrary to pseudowords or artificial words, dialect words have semantic reference and phonological lexical representations. Hence, learning to read dialect words closely matches the processes of child reading acquisition, which requires the mapping of visual representations to an existing system of lexical‐semantic representations. The only difference is that the acquisition takes place in an adult brain, which has already mastered literacy acquisition in one or more other languages.

For this purpose, we carried out a behavioral and an event‐related fMRI study in dialect speakers from South Tyrol, a region in Northern Italy where subjects' first language is the local dialect. This is a German‐derived dialect generally acquired in infancy and only used in a spoken manner, with no orthographic counterpart. South Tyroleans generally learn to speak and read standard German at school, although the predominant language spoken at home and in the environment remains the local dialect.

In the behavioral study, voice onset times (VOTs) were recorded during reading of German words, dialect words, and pseudowords. In the imaging study subjects were scanned with the event‐related fMRI technique during identical conditions. Both studies consisted of several runs in order to detect practice and learning effects along the experiment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Stimulus Selection

A total of 79 dialect nouns commonly used in South Tyrol were selected. These words did not have any similarity to standard German words (i.e., pseudohomophones) either by adding or deleting graphemes (see Appendix). In a next step we presented the same 79 words for a familiarity judgment to a South Tyrolean high school population; 87 local high school students were asked to judge whether the dialect word given in the written presentation was of high familiarity, of medium familiarity, or low familiarity. For the present experiments we used dialect words that were judged as highly familiar by at least 85%. Sixty of the 79 presented words matched this criterion and were hence selected for the present investigation. A comparable number of pseudowords were created (n = 60) by changing two graphemes from the final set of dialect words. None of these pseudowords resulted in a real German or dialect word either by changing graphemes at any position or by adding or deleting one grapheme. This procedure avoided any orthographic similarity between the classes of stimuli as tested in the same high school population. Pseudowords were matched to the dialect words for the number of syllables (word length) and the number of consonant clusters.

Finally, standard German words were matched for the number of consonant clusters and for the number of syllables with the dialect and pseudowords. The mean length for all the 180 stimuli was 1.67 syllables per word (SD, 0.632; range, 1–3) with 42.2% of the stimuli consisting of one syllable, 48.9% of two, and 8.9% of three syllables. The mean number of consonant clusters was 1.04 (SD; 0.721, range, 0–2) with the following distribution: no cluster 23.9%, one cluster 47.8%, and two clusters 28.3%.

For the registration of reading latencies, the E‐Prime software, v. 1.0, from Psychology Software Tools (PST, Pittsburgh, PA) in combination with the PST Response Box and a notebook with a 12‐inch screen and an external microphone were used.

Behavioral Experiment

Subjects

Two different groups of subjects were investigated in the behavioral part of the experiment, the experimental group of 21 dialect speakers from South Tyrol and a control group consisting of 8 nondialect speakers from Germany. All subjects in the study were right‐handed as assessed with the Edinburgh Handedness Inventory.

Dialect speakers from South Tyrol.

No subject had a prior history of neurological and/or psychiatric diseases. Subjects were women with a minimum education of 13 years. The mean age was 35.9 years (range, 24–49 years). The experiment was conducted in South Tyrol.

Nondialect speakers from Germany.

In order to exclude that the selected dialect words have orthographic similarity with real German words, we conducted the same experiment with 8 German subjects with the same level of education and sex (mean age, 34.2 years; range, 22–50 years) but from another geographical region (Berlin) who had never been confronted with the South Tyrolean dialect. The procedure was the same as above. The experiment was conducted at the University of Potsdam in Germany.

Experimental paradigm and procedure

Subjects where instructed to read as carefully and as fast as possible single words that appeared on the screen. Subjects were invited to read aloud, to hold the microphone very close, and to avoid any other noise. In addition, they were informed that the word would disappear as soon as they started to speak the word. The experiment started after a total of 10 trial sessions to ensure the correct position of the microphone and to introduce the subjects to the experimental design. Subjects were sitting about 25 inches in front of the screen. Each single stimulus was presented alone and was blocked with five other items from the same stimulus category (Fig. 1). Stimuli were hence presented in miniblocks, each containing six items belonging to the same experimental condition (German, dialect, pseudowords). Each item was presented with 850 ms of ISI (interstimulus interval) between stimuli. The stimuli were centered and written in Courier New, font size 18, bold, black font against a white background, which disappeared when the microphone registered a response. Each stimulus was presented six times during the experiment. This resulted in a total of 1,080 stimuli, consisting of 60 standard German words (presented six times), 60 pseudowords (presented six times), and 60 dialect words (presented six times), that is, 6 times 180 words / dialect words / pseudowords. The order of presentation within each block of single items and of the blocks was random. The subjects were presented with a total of 10 blocks (with six single words for each block) for each type of stimuli or 30 blocks over all classes of stimuli for each single run. The single blocks had the same number of syllables or consonant clusters. The response latencies were registered electronically and statistically analyzed with SPSS (Chicago, IL). Response times that were too fast (less than 100 ms) and those that were too long (more than 2,000 ms longer than the total mean) were excluded from the analysis, since they were possibly caused by a missing response.

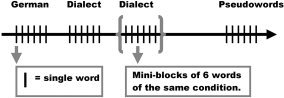

Figure 1.

The experimental paradigm. Words belonging to the same experimental condition were grouped in miniblocks of six items. Words within each miniblock and the order of miniblocks along each run were randomized (see text for further details).

fMRI Experiment

Subjects

A group of 12 right‐handed women as assessed with the Edinburgh Handedness Inventory (mean age, 24.5 years; range, 22–29 years) participated in the event‐related fMRI experiment. None of the subjects had a prior history of neurological and/or psychiatric diseases. All subjects were native speakers of the dialect under study and came from the same local area in South Tyrol where the stimuli were standardized. In order to also employ in the imaging study only novel dialect readers, none of the subjects participated in the aforementioned behavioral experiment. As in the behavioral experiment, the experimental protocol employed here followed the guidelines for human research developed by ethical committees of the participating institutions and conformed to the Helsinki Declaration, and was approved by the local ethical committee.

Experimental paradigm and procedure

As in the behavioral experiment, stimuli were presented in miniblocks each containing six items belonging to the same experimental condition (German, Dialect, Pseudowords). Each item was presented for 150 ms with an 850‐ms ISI between words. Hence, each miniblock lasted 6 s (6 × 850 ms ISI + 6 × 150 ms stimulus presentation) (Fig. 1). There were a total of four runs in the fMRI experiment. The total number of stimuli presented was 1,080, giving the possibility, due to the high number of observations within runs, to optimize the hemodynamic signal and to carry out comparisons between single runs.

Each run contained 45 miniblocks, 15 per condition (German, Dialect, Pseudowords), each consisting of six items of the same condition for a total of 90 stimuli of the same condition in each run. Hence, each single item was presented six times during the whole experiment (i.e., 1.5 times for each run). As in the behavioral experiment, the single blocks had the same number of syllables or consonant clusters and were randomly distributed over all the trials.

In order to optimize the hemodynamic response, we used a variable ISI between the miniblocks [for details, see Dale,1999]. Of the 44 ISI contained in each run, 25 were of 2,193 ms, 12 were of 3,871 ms, and 7 of 6,168 ms. The distribution of the ISIs was randomized along each run. A 2‐minute break was placed between the runs.

Subjects were instructed to read silently the stimuli presented on the monitor, which was back‐projected via a mirror‐system into the scanner. Subjects were not instructed to remember the items, but only to read them. However, at the end of the fMRI session a recall task of the words presented during the experiment was performed as a control session of performance. Subjects were invited to write as many items they remembered belonging to the three classes of stimuli.

Image acquisition and processing

We used the fMRI‐event‐related technique (GE, Milwaukee, WI; 1.5 T, flip angle 90°, TE = 60 ms, TR = 2000 ms, field of view (FOV) = 280 × 280, matrix 64 × 64; 16 slices per volume, 210 volumes per each run, slice thickness = 5 mm) and SPM2 (Wellcome Department of Cognitive Neurology, London, UK), running on Matlab 6.5 (MathWorks, Natick, MA) for all preprocessing steps and statistical analysis.

The first 10 volumes of each session were not considered in order to optimize the signal of the EPI images. Slice timing procedures were applied to all EPI images in order to correct for differences in acquisition time between slices. For each subject, all the acquired data were realigned to the first image of the first session in order to neutralize effects of intra‐ and intersession movements. The anatomical volume was realigned to the first EPI volume. The realigned images were “normalized” into Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) stereotactic space. The normalization parameters were estimated by matching the realigned anatomical volume with the customized T1 template created from the acquired brain anatomical volumes of the participants.

The parameters were then applied to the realigned functional and anatomical volumes, obtaining normalized volumes with a voxel size of 2 × 2 × 2 mm. All the images were then smoothed with a Gaussian kernel of 8 × 8 × 8 mm in order to increase the signal‐to‐noise ratio.

Statistical Analysis

The effects of the experimental design were assessed on a voxel‐by‐voxel basis using the General Linear Model (GLM). We used SPM2 to analyze functional imaging data and direct comparisons between the conditions were performed on a second‐level analysis (random effects) in order to generalize the results from our sample to the population [Friston et al., 1999]. The three simple main effects were false discovery rate (FDR)‐corrected and calculated at P < 0.01. Comparisons between conditions containing all respective runs were set at P < 0.001 and family‐wise error (FWE)‐corrected. For the evaluation of the temporal dynamics, comparisons between conditions in single runs were also set at P < 0.001 (uncorrected). An extent threshold of 10 contiguous voxels was applied to all main effects and comparisons. The following contrasts were performed: (1) Simple Main Effects for reading in German, Dialect, and Pseudowords; (2) Direct Comparisons between Dialect vs. German, Pseudowords vs. German, and Dialect vs. Pseudowords; and (3) direct comparisons between the following single runs: first run Dialect vs. first run German, fourth run Dialect vs. fourth run German; first run Pseudowords vs. first run German; fourth run Pseudowords vs. fourth run German, and first run Dialect vs. fourth run Dialect.

All the coordinates derived from the statistical analysis were converted from MNI to Talairach and Tournoux [1988] stereotaxic space.

In order to more accurately inspect temporal changes in activation along the four acquisition runs, we extracted comparison specific fitted hemodynamic time‐curves averaged over individual runs for each subject separately and then by averaging fitted values over subjects for each of the four runs. Information regarding the effect size of the statistical comparisons, along with its lag and duration, could thus be plotted over time, indicating the presence of increases or decreases of activation in a given brain region over the four runs. Time‐curves were extracted for three major regions of interest of the dialect vs. German statistical comparisons, namely, the left anterior hippocampus (x = −20, y = −16, z = −12), the left caudate nucleus (x = −16, y = 8, z = 4), and the left inferior frontal gyrus (x = −46, y = 26, z = 8).

RESULTS

Behavioral Results

South Tyrolean dialect speakers

The mean VOT over all word classes and trials was 569.43 and 341 ms per syllable. A 3 × 6 two‐factorial, univariate within‐subjects analysis of variance (ANOVA) with the three stimulus types (German, Dialect, and Pseudoword) and the six trials as the independent variables and the stimulus reaction times as the dependent variables showed a significant effect of stimulus type (F = 477, degrees of freedom (df) = 2, P ≤ 0.00), trial (F = 126, df = 5, P ≤ 0.00), and an interaction between trial and stimulus type (F = 15, df = 10, P ≤ 0.00). A post‐hoc comparison (Scheffé test) showed that 1) reaction times were significantly slower in Trial 1 than in any other trial (2–6); 2) reaction times to Trial 2 were slower than the reaction times in any of the following trials (3–6), at a P < 0.05 level; 3) the differences between the next trials were not statistically significant at this level. This means that for all the presented stimuli, after the second trial, there was no further significant reduction in the response latency. The same comparison in the case of real German words was statistically significant (P < 0.05 level) only for the first trial in comparison to all other trials, while the second trial did not differ from the following Trials 3–6. The post‐hoc comparison for dialect words showed a further improvement of the reaction times after the first stimulus presentation: again, Trial 1 differed significantly from all other trials, but Trial 2 also differed from Trials 5 and 6, but not from Trials 3 and 4 at a P = 0.05 level. For pseudowords, we found a faster response not just in Trial 2 in comparison to Trial 1 but also in Trials 3–6 in comparison to Trial 2. After Trial 3 there was no further improvement.

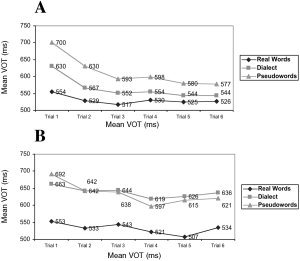

The single VOTs for the different stimulus types from Trials 1–6 are shown in Figure 2. While the dialect words were within the VOT range of the first presentation of real German words after as few as three runs, pseudowords never reached the German level. In Trial 6 pseudowords were still read slower than German words in Trial 1 (AM German Words Trial 1 = 554, AM pseudowords Trial 6 = 577; t‐paired sample test = 5.638, df = 1187, P < 0.00). On the other hand, even when dialect words in Trial 2 were still read slower than German words during Trial 1 (T = −2.599, df = 1187, P = 0.01), from Trial 3 they significantly reached the German VOTs of Trial 1 (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Mean voice onset time (VOT) in ms for different word classes (real German words, dialect words, and pseudowords) and Trials 1–6 in subjects (n = 21) from South Tyrol (A, top) and in a control group (n = 8) from Germany (B, bottom).

German nondialect speakers

As expected, a 3 × 6 ANOVA with the three stimulus types and the six trials as independent variables, and the VOT as the dependent variable, showed a significant main effect of stimulus type (F = 187, df = 2, P = 0.000), of trial (F = 11.06, df = 5, P = 0.000), and a nonsignificant effect of the interaction stimulus type/trial (F = 1.2, df = 10, P = 0.279). A post‐hoc Scheffé comparison resulted in significant differences (at a 0.05 level) between real words and pseudowords and between real words and dialect words. No significant difference was found between dialect words and pseudowords. This means that dialect words and pseudowords were processed with the same speed in this group of subjects (Fig. 2), excluding that dialect words bear a relevant similarity to standard German words.

Postscanning memory performance

In order to maintain a high level of attention through the experiment, the subjects were told that a behavioral testing would be carried out after the scanning. However, they were not explicitly told to memorize words. At the end of the scanning sessions subjects were invited to recall as many items belonging to the three different conditions as they could. Subjects recalled on average 10.5 dialect words, 3.5 German words, and 0.5 pseudowords.

fMRI Results

Pattern of brain activity

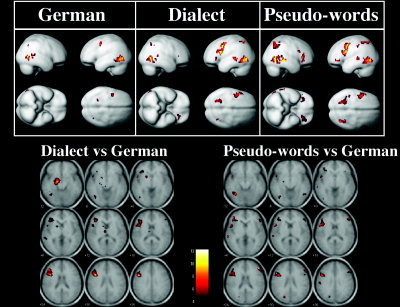

All three simple main effects (i.e., silent reading of German words, dialect words, and pseudowords) engaged similar networks of areas in the left hemisphere. These included the inferior frontal gyrus, the superior temporal sulcus, the posterior superior temporal gyrus, the inferior parietal lobule, and the temporo‐occipital junction encompassing the fusiform gyrus. This latter brain region was activated also in the right hemisphere (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Patterns of brain activity elicited by the simple main effects of the three conditions (German, dialect, and pseudowords, top row) and the direct comparisons (containing all respective runs, bottom row) between dialect vs. German (left) and pseudowords vs. German (right). The simple main effects are implemented on smoothed whole‐brain SPM templates. For representation purpose, brain activity localized on the inferior surface of the templates, such as in the fusiform gyrus, is reported on the lateral surface (see Results for anatomical localization of brain activity foci). As illustrated in the bottom row, important differences may be noted for each of the two comparisons. Reading dialect words as compared to German selectively elicited the left anterior hippocampus and subcortical structures such as the left caudate and left thalamus. Conversely, pseudoword reading compared to German resulted in a selective engagement of the left parietal‐occipital sulcus, the left middle occipital gyrus, and a more extensive engagement of the right hemisphere including the right inferior frontal gyrus and the right fusiform gyrus (see text and Table I for further details).

There were, however, clear differences in the pattern of brain activity as revealed by the direct comparison between dialect reading vs. German reading and pseudoword reading vs. German (Fig. 3, Table I). Both conditions when compared individually to German showed left hemispheric activations: the inferior frontal gyrus including Broca's area (both pars triangularis and opercularis), the middle frontal gyrus, the precuneus, the inferior parietal lobule, the anterior and posterior superior temporal gyrus (Wernicke's area), and the fusiform gyrus including the so‐called word form area. Additional brain activity was found also in the right middle frontal gyrus and the right precuneus.

Table I.

Direct comparisons between dialect and German reading and pseudowords and German reading at P < 0.001

| Anatomical location | x, y, z | Z‐value | Brodmann area |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dialect vs. German | |||

| L inferior frontal gyrus | −38, 8, 28 | 5.34 | 44 |

| −52, 10, 16 | 3.85 | 44 | |

| −40, 30, 12 | 4.13 | 45 | |

| −44, 26, 24 | 4.26 | 45 | |

| −32, 30, 0 | 3.49 | 47 | |

| L middle frontal gyrus | −44, 6, 36 | 5.07 | 9 |

| L precuneus | −24, −50, 48 | 3.93 | 7 |

| −28, −50, 56 | 3.71 | 7 | |

| L anterior hippocampal formation | −16, −10, −12 | 5.03 | 28/34 |

| −20, 2, −16 | 4.25 | 28/34 | |

| L anterior superior temporal gyrus | −50, 10, 0 | 4.03 | 22 |

| L posterior superior temporal gyrus | −54, −40, 8 | 3.94 | 22 |

| L fusiform gyrus | −42, −68, −4 | 4.06 | 37 |

| −40, −62, −12 | 3.60 | 37 | |

| L caudate | −18, 8, 0 | 3.85 | |

| L thalamus | −6, −10, 12 | 3.98 | |

| −2, −18, 12 | 3.81 | ||

| R middle frontal gyrus | 48, 34, 20 | 3.91 | 46 |

| R precuneus | 34, −64, 56 | 4.06 | 7 |

| Pseudowords vs. German | |||

| L superior frontal gyrus | −4, 20, 52 | 3.71 | 6/8 |

| L precentral gyrus | −46, 6, 48 | 4.28 | 6 |

| −46, 8, 36 | 4.23 | 6 | |

| L inferior frontal gyrus | −52, 14, 16 | 4.30 | 44 |

| −42, 18, 20 | 4.29 | 44 | |

| −40, 30, 8 | 3.94 | 45 | |

| −30, 30, 4 | 3.18 | 45 | |

| −44, 40, 4 | 4.34 | 46 | |

| L precuneus | −24, −48, 48 | 4.56 | 7 |

| L inferior parietal lobule | −46, −28, 48 | 4.29 | 40 |

| −44, −30, 44 | 4.29 | 40 | |

| L anterior superior temporal gyrus | −50, 8, 4 | 3.69 | 22 |

| −52, 4, 4 | 3.63 | 22 | |

| L posterior superior temporal gyrus | −62, −32, 4 | 4.08 | 22 |

| L fusiform gyrus | −34, −58, −12 | 4.32 | 37 |

| −46, −52, −12 | 3.31 | 37 | |

| L middle occipital gyrus | −40, −76, −4 | 3.66 | 19 |

| L parietal−occipital sulcus | −22, −74, 28 | 4.06 | 18/19 |

| R middle frontal gyrus | 54, 22, 32 | 3.99 | 9 |

| 50, 26, 32 | 3.92 | 9 | |

| 46, 34, 24 | 4.99 | 46 | |

| R inferior frontal gyrus | 50, 26, 8 | 3.92 | 45 |

| 42, 32, 4 | 3.29 | 45 | |

| R precuneus | 30, −68, 56 | 4.09 | 7 |

| R inferior parietal lobule | 34, −54, 52 | 3.59 | 40 |

| 40, −56, 56 | 3.51 | 40 | |

| R fusiform gyrus | 44, −62, −8 | 3.86 | 37 |

It is noteworthy that there were some brain areas that were specifically activated by each of these direct comparisons. Indeed, the direct comparison between dialect reading and German reading showed a selective activation of the left anterior hippocampal formation and of subcortical nuclei, namely, the left caudate and thalamus. This selective engagement of the left anterior hippocampal formation specific to reading dialect words was also confirmed by a direct comparison between dialect vs. pseudoword reading (data not shown).

On the other hand, the direct comparison between pseudowords and German resulted in a selective engagement of the left parietal‐occipital sulcus and the left middle occipital gyrus, and in a more extensive right hemispheric activation, involving the inferior frontal gyrus and the fusiform gyrus. Additional activity was also observed in the left precentral and superior frontal gyrus.

Direct comparisons of reading conditions in single runs were also performed in order to investigate learning effects (Table II, Fig. 4).

Table II.

Direct comparisons between single runs at P < 0.001. (first part = dialect vs. German; second part = pseudowords vs. German)

| Anatomical location | x, y, z | Z‐value | Brodmann area |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st run dialect vs. 1st run German | |||

| L precentral gyrus | −48, 2, 44 | 3.76 | 6 |

| L middle frontal gyrus | −50, 12, 36 | 4.99 | 9 |

| −46, 22, 28 | 4.53 | 46 | |

| L inferior frontal gyrus | −50, 14, 24 | 3.87 | 44 |

| −52, 12, 20 | 3.83 | 44 | |

| −40, 24, 16 | 4.44 | 45 | |

| −44, 28, 8 | 4.08 | 45 | |

| −40, 26, −4 | 3.52 | 47 | |

| L precuneus | −22, −54, 44 | 4.38 | 7 |

| −22, −64, 56 | 3.81 | 7 | |

| L inferior parietal lobule | −32, −54, 44 | 3.65 | 40 |

| L anterior hippocampal formation | −12, 2, −12 | 4.75 | 28/34 |

| −14, −4, −12 | 4.56 | 28/34 | |

| −24, 6, −16 | 3.93 | 28/34 | |

| L posterior superior temporal gyrus | −62, −36, 4 | 4.56 | 22 |

| L fusiform gyrus | −34, −62, −8 | 3.95 | 37 |

| L caudate | −18, 12, 0 | 5.11 | |

| −18, 8, 12 | 3.53 | ||

| L thalamus | −20, −6, 12 | 4.56 | |

| 4th Dialect run vs. 4th German | −6, −12, 16 | 3.52 | |

| L inferior frontal gyrus | −48, 6, 12 | 3.67 | 44 |

| −48, 10, 20 | 3.70 | 44 | |

| −42, 14, 28 | 3.50 | 44 | |

| L anterior superior temporal gyrus | −50, 8, −4 | 3.93 | 22 |

| 1st run pseudowords vs. 1st run German | |||

| L superior frontal gyrus | −4, 18, 48 | 3.77 | 6/8 |

| L precentral gyrus | −40, 4, 36 | 4.78 | 6 |

| L inferior frontal gyrus | −42, 14, 28 | 4.53 | 44 |

| −52, 12, 16 | 4.17 | 44 | |

| −32, 32, 4 | 4.42 | 45 | |

| −38, 28, 12 | 4.11 | 45 | |

| −44, 30, 4 | 4.07 | 45 | |

| L precuneus | −28, −42, 48 | 4.46 | 7 |

| −22, −54, 44 | 3.84 | 7 | |

| L inferior parietal lobule | −56, −22, 40 | 3.30 | 40 |

| L fusiform gyrus | −38, −62, −12 | 3.67 | 37 |

| L thalamus | −14, −8, 16 | 4.41 | |

| R middle frontal gyrus | 48, 14, 32 | 3.85 | 9 |

| R inferior frontal gyrus | 40, 28, 4 | 3.87 | 45 |

| R precuneus | 30, −60, 56 | 3.62 | 7 |

| 4th run pseudowords vs. 4th run German | |||

| L inferior frontal gyrus | −42, 18, 20 | 3.89 | 44 |

| −44, 32, 4 | 3.54 | 45 | |

| −40, 34, −4 | 3.49 | 47 | |

| L precuneus | −24, −50, 52 | 3.71 | 7 |

| L inferior parietal lobule | −46, −30, 44 | 4.08 | 40 |

| L inferior temporal/fusiform gyrus | −50, −50, −8 | 3.53 | 37 |

| L parietal occipital sulcus | −20, −74, 28 | 4.20 | 18/19 |

| −22, −76, 36 | 4.14 | 18/19 | |

| R precuneus | 30, −70, 56 | 3.62 | 7 |

| 40, −60, 56 | 3.28 | 7 | |

| R fusiform gyrus | 40, −60, −8 | 3.26 | 37 |

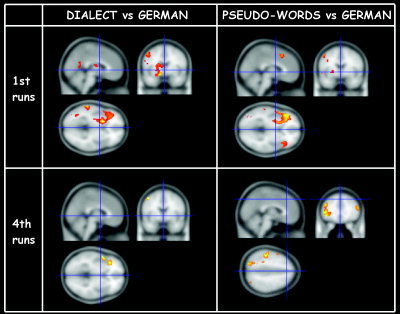

Figure 4.

Direct comparisons between single runs, first runs (top) and last runs (bottom) for dialect vs. German (left) and pseudowords vs. German (right). Only reading dialect words activated the left anterior hippocampal system and the left caudate nucleus. The involvement of the left anterior hippocampus was present only during the initial exposure to dialect words, which may suggest its role in learning and consolidating new written lexical entries. Moreover, following practice, the neural substrate of dialect reading converged to that of German reading as shown in the comparisons of the last runs (bottom).

The comparison between the first runs for dialect vs. German showed a pattern of left hemispheric brain activity in the precentral gyrus, middle and inferior frontal gyrus, including Broca's area, precuneus and inferior parietal lobule, the anterior hippocampal formation, posterior superior temporal gyrus, fusiform gyrus, and in the left caudate and thalamus. When comparing the last runs of the same condition (dialect vs. German), a significantly reduced pattern of brain activity resulted. Activation foci were limited to the left inferior frontal gyrus (Broca's area) and to the left anterior superior temporal gyrus. Direct comparison between the first vs. the last run of dialect reading (data not shown) confirmed the engagement of the left anterior hippocampal formation, the left middle and inferior frontal gyrus, the left superior temporal gyrus, the left fusiform gyrus, and the left caudate. Further activity was found in the right middle temporal gyrus.

The direct comparison between the first runs for pseudowords vs. German showed an extensive pattern of brain activation in the left hemisphere (precentral gyrus, superior, middle and inferior frontal gyri (including Broca's area), precuneus and inferior parietal lobule, fusiform gyrus, and the thalamus). On the right side, brain activity was observed in the middle and inferior frontal gyri and the precuneus. When comparing the last runs of pseudoword vs. German, this extended brain activity persisted, in contrast to the findings of the dialect vs. German last runs comparison (Fig. 4, Table II).

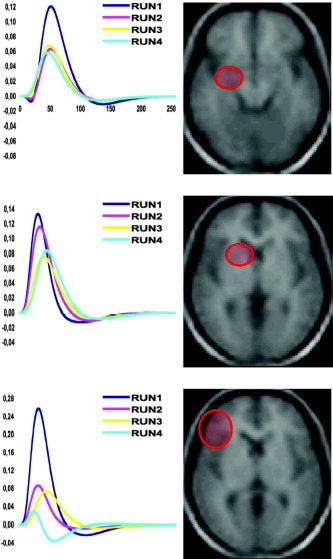

Peristimulus time‐fitted responses

Time‐curves were extracted for three major regions of interest of the dialect vs. German comparison: the left anterior hippocampus (x = −20, y = −16, z = −12), the left caudate nucleus (x = −16, y = 8, z = 4), and the left inferior frontal gyrus (x = −46, y = 26, z = 8). In all these regions a decrease in the amplitude of activation was observed from Run 1 to Run 4, underlining that dialect reading was less in need of these brain structures following exposure (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Average peristimulus time‐fitted responses for the four experimental runs are shown for three different stereotaxic coordinates before the dialect vs. German comparison. Fitted responses are plotted in terms of activation effect sizes (in percent) against resolution time bins (1 bin = 125 ms). Top row: the left anterior hippocampus (x = −20, y = −16, z = −12); middle row: the left caudate nucleus (x = −16, y = 8, z = 4); bottom row: the left inferior frontal gyrus (x = −46, y = 26, z = 8).

DISCUSSION

The main aim of this study was to investigate how readers of a novel language build up an orthographic lexicon, i.e., establish a link between a meaning, a phonological representation, and an orthographic word form. Behavioral measurements and an event‐related fMRI study were employed to investigate this issue. We discuss first the behavioral results and then the brain imaging results.

Behavioral Study

When children start learning to read, an orthographic lexicon for phonologically/semantically familiar words is not available to them. In stage models of reading acquisition [Ehri,1997; Frith,1985; Seymour,1997], the orthographic stage becomes established only after acquisition of GPC knowledge, as phonological processing is crucial to the establishment of the orthographic lexicon [Frith,1985]. Experienced readers directly access orthographic words forms and link them to phonological word forms, resulting in a faster and more efficient whole‐word (lexical) reading.

Learning to read dialect words may be considered as a comparable situation, in which the learner is confronted with novel printed words that have semantic as well as phonological representations. Printed dialect words can probably be read only through a GPC mechanism when the adult reader is first exposed to them. The availability of corresponding semantic and phonological representations results in a fast buildup of orthographic representations in a mature learner.

The present behavioral findings are in agreement with this assumption: following repeated exposure, the VOTs of dialect words converged to the German range of VOTs (Fig. 2). Initially, the dialect words were between the real German words and the pseudowords. However, only in the case of dialect speakers after three runs were the dialect words processed nearly as fast as German words. This was not the case, as expected, for the nondialect‐speaking group, or when dialect speakers processed pseudowords.

Our behavioral results may be accommodated by accounts which do not postulate stages of reading acquisition. For instance, Perfetti's [1992] Restrictive‐Interactive Hypothesis predicates that learning to read involves the acquisition of increasing numbers of word representations that can be accessed by their spelling, on the basis of changes in the specificity and redundancy of individual words' representations. As a child learns to read, her representations of words have increasingly specific letters in their correct positions (i.e., increased specificity) and these representations become phonologically redundant. Increasing specificity and redundancy allow high‐quality word representations, and individual words move from a so‐called “functional lexicon” consisting of words that can be read only with effort (such as the unfamiliar or novel words), to a so‐called “autonomous lexicon,” which includes words that can be read with minimal effort. Clear evidence for such a shift from a functional lexicon to a more autonomous lexicon may be demonstrated by the decreasing VOTs of dialect words observed after practice in the present study.

In Perfetti's model [1992], words rather than readers are considered to be in a “decoding stage.” The readers of the present study have already acquired GPC knowledge during childhood when they learned to read their second language (German). Hence, when confronted with novel words such as dialect words, they already knew how to use GPC mechanisms, even when the phonology of the dialect is not the same as that of German. Following Share's proposal [1995], readers skilled in phonological decoding are provided with a self‐teaching mechanism that, along with oral vocabulary knowledge and context, is useful for learning to read novel words that have not been previously encountered. After a few correct decodings these words can be recognized quite automatically and, therefore, a shift from a functional to an automatic lexicon is plausible. In other words, the present results may be considered to reflect the buildup of an automatic lexicon for dialect words during the time of the experiment.

fMRI Study

As for the imaging results, we observed in the first place the specific activation of a set of regions, including the left anterior hippocampal formation and subcortical nuclei, during the initial exposure to dialect words. Second, there was a convergence of the neural substrate underlying dialect reading to that of German reading (the second language in which the subjects were proficient readers). These two aspects may be inherent to two different processes when encountering novel printed words: (1) associating a meaning with a given word form, and hence the buildup of a new orthographic lexicon during the initial exposure to dialect words; and (2) changing the reading strategy after repeated exposure to dialect words. These two aspects will be discussed in detail.

Buildup of a New Orthographic Lexicon

The direct comparisons of the first runs between dialect vs. German revealed activations in the left anterior hippocampus and basal ganglia and along the left hemisphere in the middle and inferior frontal gyrus, precuneus, inferior parietal lobule, posterior superior temporal gyrus, and fusiform gyrus. Thus, the buildup of a new orthographic lexicon may be achieved through the interplay of these brain areas that subserve different aspects of reading and reading acquisition.

Among these cortical structures, the left inferior frontal gyrus, the left inferior parietal lobule, and the posterior superior temporal gyrus are considered the neural substrate of phonological working memory [Paulesu et al.,1993] and their role in reading is well described [Tan et al.,2005]. It should be underlined here that GPC reading mechanisms are by definition in need of greater involvement of phonological processing than lexically based reading. The graphemes of a novel word or of a pseudoword must be phonologically recoded and maintained in working memory before being assembled into a final pronunciation. A component of working memory, the phonological loop, has a crucial role in learning to read novel words [Gathercole,1999]. The brain activity in the left inferior frontal gyrus (BA 45 and 47) reported for reading irregular words and pseudoword supports the hypothesis that this region may be specifically involved in distinct sublexical mechanisms, such as orthography to phonology recoding and phonological assembly [Joubert et al.,2004, Pugh,1996]. Moreover, as evidenced by Joubert et al. [2004], these frontal areas are functionally linked to the posterior superior temporal gyrus, which is thought to contribute to a phonologically based form of reading [Fiez et al.,1999].

Activation changes were also found in the left fusiform gyrus and, in particular, in the left midfusiform area, an area labeled by some authors as the visual word form area [Cohen et al.,2002]. Even though the idea of a dedicated single brain area such as the word form area is not universally accepted, most authors agree that the left midfusiform gyrus is involved in visual word processing [Price and Devlin,2003; Price and Mechelli,2005; Tan et al.,2000,2005]. In our study, the left midfusiform area was more active for pseudoword and dialect word reading than for German, as outlined by the direct comparisons; furthermore, it was also more active in the first vs. fourth run comparison. This finding is in full agreement with the results of a recent study by Kronbichler et al. [2004], which reported a parametric inverse correlation between word familiarity and the activation of the left fusiform region. The engagement of this area was maximal for pseudowords and minimal for high‐frequency words. Studies that manipulated familiarity by repeated presentations of object pictures [Chao et al.,2002; van Turennout et al.,2000] and faces [Rossion et al.,2003] found that higher familiarity resulted in lower brain activation in the fusiform region. These authors conclude that this area specializes in extracting and storing abstract patterns from visual input, indicating that the left fusiform region is a repository for orthographic patterns.

During the initial exposure to dialect words the left hippocampal system was engaged. One possible interpretation of this finding is that this structure is responsible for the complex process of associating meanings to orthographic word‐forms. There is growing evidence that the hippocampal formation may play a critical role in specific aspects of language processing, such as memorization of words in the mental lexicon [Gabrieli et al.,1988] and learning rule‐governed combinations of words by mental grammar [Opitz and Friederici,2003]. The convergence of sensory information and the back‐projections from the hippocampus to the frontal, temporal, and temporoparietal cortex place the hippocampus in a unique position for binding information and consolidating new memories. These memories afterwards become independent of the hippocampus, relying solely on neocortical regions—in the case of language, on Broca's area, Wernicke's area, and surrounding areas. It is well known from lesion studies in amnesic patients and functional imaging studies in normal subjects that the hippocampus is critically involved in the acquisition of relational information [Eichenbaum,2004; Squire et al.,2004]. A large body of evidence suggests that the hippocampus encodes associations among stimuli, actions, and places that compose discrete events. In a study that directly compared the encoding of stimuli in combination or separately, greater hippocampal activation was present when subjects associated a person with a house, as compared to making independent judgments about the person and house [Henke et al.,1997]. There is also evidence that the hippocampus is more activated when subjects are required to link multiple encoded items to one another by systematic comparisons than using the rote rehearsal of individual items [Davachi and Wagner,2002]. It is noteworthy that in the present study the left hippocampal activation was not found in the pseudoword vs. German comparison, suggesting that the association process is specific for meaningful stimuli.

Furthermore, the magnitude of hippocampal activation during the linkage of items may also predict later success in recognition. Recent studies have reported hippocampal activity during the encoding of face‐name associations [Zeineh et al.,2003] and along the entire longitudinal extent of the hippocampus when subjects studied face‐name pairs that they later remembered with high confidence [Sperling et al.,2003]. This is in agreement with the finding that, even if our subjects were not asked to memorize the words during the reading experiment, they remembered significantly more dialect words than German or pseudowords.

A specific activation for dialect word reading was also observed in the left caudate nucleus. Several theories propose the left subcortical nuclei, chief among them the caudate nucleus, as part of a neural system regulating the release or selection of cortically generated lexical items for production after semantic monitoring [Cappa and Abutalebi,1999; Wallesch and Papagno,1988] or in the selective attentional engagement of the semantic network [Copland,2003]. It is interesting to note that damage to this circuit in humans was also associated with deficits in verbal learning and memory [Trepanier et al.,1998].

The hippocampus and basal ganglia have been conceptualized as two competing learning systems supporting, respectively, declarative vs. procedural memory [e.g., Packard et al.,1989; Packard and Knowlton,2002; Poldrack et al.,1999,2001]. While the hippocampus and the basal ganglia may each have distinct roles in the acquisition of new representation, they may work in orchestration for the final tuning of these representations [Frank et al.,2001]. The hippocampus can rapidly bind information into conjunctive representations (such as linking a meaning to a new word form), while the basal ganglia can help to modulate responses based on these newly acquired representations. Moreover, the basal ganglia may act as an adaptive gating mechanism to the prefrontal cortex since the latter must be updated rapidly with the new representations while also robustly maintaining other information [Frank et al.,2001] (see above for the role of the left prefrontal cortex in phonological working memory and its role in the GPC reading mechanism). Since the basal ganglia and the prefrontal cortex work together as a system via distinct anatomical loops [Alexander and Crutcher,1990], the modulatory action of the basal ganglia on newly acquired representations in the prefrontal cortex may become plausible [Atallah et al.,2004]. Following this line of reasoning, the activity observed in the left anterior hippocampal formation in our study may be directly linked to the acquisition of new representations (the buildup of the orthographic lexicon), whereas the engagement of the left caudate may be associated with modulatory effects.

Neural Convergence after Exposure

The left anterior hippocampal activation was present only during the initial exposure to dialect words, as indicated by the direct comparisons between the first runs (initial exposure) and the last runs, when reading was possibly mediated through a direct lexical pathway and/or through a more automatic lexicon (Fig. 4). Also, the run‐specific average hemodynamic curves calculated for the left anterior hippocampus showed a gradual decrease of the hemodynamic response through the four runs, indicating that dialect reading was no more in need of that brain structure after learning (Fig. 5).

A decrease of brain activity for dialect reading was observed along the experiment also in the left inferior frontal gyrus, the left posterior superior temporal gyrus, and the left inferior parietal lobule. During dialect reading brain activity within the left midfusiform area also converged after practice to that of German reading (Fig. 4, Table II). Hence, after learning to read the dialect words lexically (or, according to Perfetti's model [1992], when words moved from a functional to an automatic lexicon), these areas were less active. This was not the case when reading pseudowords, which were still processed through GPC mechanisms.

We propose that the neural substrate for dialect reading converged to that of German (for which reading is obviously mastered with a high degree of proficiency) after short‐term practice. It is well known that neural changes may be induced by specific practice. As outlined by Raboyeau et al. [2004], studies dealing with practice effects in language tasks may be classified into two main categories. First, there are studies aimed at investigating the effect of practice via task repetition. In these studies behavioral changes have been noted, including stereotypical and quicker responses for lexical tasks [Buckner et al.,2000; Cardebat et al.,2003] or semantic tasks [Raichle,1994; Simpson et al.,2001; Thompson‐Schill et al.,1999], and these changes are accompanied mainly by decrements of brain activation. The second type of study focused on the neural changes associated with the acquisition of language‐based rules or abilities after training. Studies devoted to this topic showed a large variability in the results. For example, decrease of activation [Fletcher et al.,1999; Opitz and Friederici,2003; Thiel et al.,2003], increase [Callan et al.,2003; Opitz and Friederici,2003; Wang et al.,2003], as well as recruitment of new areas [Callan et al.,2003; Wang et al.,2003] have been found, whatever the modality and the task. Both these aspects were at play in the present study. Reading acquisition is based both on task repetition and on rule learning. Accordingly, learning‐related changes in brain circuitry (i.e., from the left anterior hippocampus to left hemispheric cortical regions) as well as practice‐induced functional decrements over the left hemisphere were observed.

As to the relevance of the present findings for the neural correlates of reading acquisition in childhood, it is difficult to compare our study to Turkeltaub et al.'s [2003] cross‐sectional study, in which brain activity of more experienced adult readers was compared with that of younger readers. A prevalent brain activity in the left middle temporal and inferior frontal gyrus was found in adult readers, and a developmental change was observed by the decreasing activity in the right fusiform gyrus and right precuneus. Our study focused on the acquisition of novel printed words in highly skilled readers, and thus cannot be directly compared to Turkeltaub et al.'s [2003] findings. Considering the pattern of brain activity of the simple main effect of German reading (highly skilled reading) compared with that of dialect reading (less skilled reading), an involvement of the right fusiform gyrus and right precuneus was found only in the latter (Fig. 3). This in line with the main differences between the less skilled and the highly skilled readers in Turkeltaub's et al.'s study [2003]. Neural changes related to the more efficient processing of a newly acquired orthographic lexicon were paralleled in our study by a functional decrement over the left hemisphere. The neural correlates of dialect reading converged to that of the well‐mastered German orthographic lexicon.

The convergence phenomenon has been often described in functional neuroimaging studies focusing on language processing in bilinguals [Green,2003]. For bilinguals, increasing the proficiency in a second language that was previously mastered at a lower degree, or increasing the exposure to it, is paralleled by a neural convergence of its representation to that of the native language [Perani and Abutalebi,2005]. The convergence phenomena observed for dialect reading in our experiment may be due to the above‐mentioned switch of reading strategies. Following stage models of reading, a shift from a purely sublexical reading strategy to a lexical reading strategy may have taken place at the end of the experiment. According to nonstage models, a shift from a more effortful functional to a more automatic lexicon may have taken place. It may be surprising that the neural representation of dialect reading (i.e., the native language) converged to that of the second language of our subjects. However, dialect speakers generally acquire literacy only for the second language (also called the “standard language”) through formal schooling, while the native language is used only orally. In this specific case, reading the native language, acquired late in life, may be processed after practice through the same neural mechanism that supports reading of the second, more proficient, language. These results emphasize the adult brain's potential for neural plasticity.

CONCLUSIONS

Linking a meaning to a word form is a crucial step in literacy acquisition and in the present study we attempted to outline the neural dynamics of late literacy acquisition using a paradigm based on single‐word reading in adult dialect speakers. It is obvious that it is not possible to generalize from our study to the whole aspect of literacy acquisition. For instance, linking letter‐to‐sound is a different step of literacy acquisition, which generally precedes the buildup of the orthographic lexicon. Associating letters‐to‐sounds was recently investigated by Hashimoto and Sakai [2004], who reported functional changes over the left hemisphere, mainly in posterior auditory and visual associative areas that correlated with performance improvement of their adult subjects. However, when it comes to the next step, i.e., implementing a meaning to a given orthographic word form, the present study provides evidence that the left anterior hippocampal formation, as well as subcortical nuclei, are critically involved in the learning process of meaningful stimuli. Second, there is clear evidence of brain plasticity associated with the late acquisition of a language skill, as indicated by the convergence of brain activity patterns during reading the native and the already well‐mastered second language. The plastic neural changes we observed during the reading acquisition process are most likely related to a switch of reading strategies: following dual route models, from a purely sublexical mechanism to a lexical mechanism typical of experienced readers; and according to nonstage accounts, from a more effortful functional lexicon to a more automatic lexicon.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Paola Scifo and Massimo Danna for technical assistance.

Table .

Familiarity rating of the Dialect words used in the experiments (N = 79)

| Dialect words | Highly familiar |

|---|---|

| 1. Kaas | 99.9 |

| 2. Soal | 99.9 |

| 3. Rearl | 99.9 |

| 4. Goas | 99.9 |

| 5. Hangerle | 99.9 |

| 6. Toag | 99.9 |

| 7. Toal | 99.9 |

| 8. Gitsche | 99.9 |

| 9. Gigger | 99.9 |

| 10. Tschurtsche | 99.9 |

| 11. Pfearscher | 99.9 |

| 12. Fotze | 99.9 |

| 13. Paferle | 99.9 |

| 14. Hoor | 99.9 |

| 15. Kampl | 99.9 |

| 16. Schnaggler | 98.4 |

| 17. Scherpe | 98.4 |

| 18. Gugger | 98.4 |

| 19. Huder | 98.4 |

| 20. Kondl | 98.4 |

| 21. Holer | 98.4 |

| 22. Tschigg | 98.4 |

| 23. Gfries | 98.4 |

| 24. Notscher | 98.4 |

| 25. Tatl | 98.4 |

| 26. Graffl | 96.8 |

| 27. Kobis | 96.8 |

| 28. Glump | 96.8 |

| 29. Keschte | 96.8 |

| 30. Zoggler | 96.8 |

| 31. Lopp | 96.8 |

| 32. Potsch | 96.8 |

| 33. Focke | 96.8 |

| 34. Bsuff | 96.8 |

| 35. Pfoat | 95.2 |

| 36. Grantn | 95.2 |

| 37. Grattl | 95.2 |

| 38. Goggele | 95.2 |

| 39. Bloter | 93.7 |

| 40. Briegl | 93.7 |

| 41. Weimer | 93.7 |

| 42. Gotl | 93.7 |

| 43. Seicher | 93.7 |

| 44. Stieze | 93.7 |

| 45. Goasl | 92.1 |

| 46. Louter | 92.1 |

| 47. Piesele | 92.1 |

| 48. Riffl | 92.1 |

| 49. Potsche | 90.5 |

| 50. Tatte | 90.5 |

| 51. Roafe | 88.9 |

| 52. Riebler | 88.9 |

| 53. Gregge | 88.9 |

| 54. Knofl | 87.3 |

| 55. Wompe | 87.3 |

| 56. Scherm | 87.3 |

| 57. Knottl | 85.7 |

| 58. Blätsche | 85.7 |

| 59. Mune | 85.1 |

| 60. Tschurele | 85.1 |

| 61. Zegger | 82.5 |

| 62. Taase | 82.5 |

| 63. Gfrett | 79.4 |

| 64. Roan | 77.8 |

| 65. Ponze | 76.2 |

| 66. Wialer | 73 |

| 67. Knotte | 68.3 |

| 68. Tschoch | 68.3 |

| 69. Solder | 58.7 |

| 70. Wosn | 54 |

| 71. Glutsche | 49.2 |

| 72. Pragger | 47.6 |

| 73. Toas | 42.9 |

| 74. Huzer | 39.7 |

| 75. Haangl | 38.1 |

| 76. Gete | 38.1 |

| 77. Glatsch | 28.6 |

| 78. Schoper | 25.4 |

| 79. Zapin | 23.8 |

Footnotes

A dialect may be defined as a variant, or variety, of a standard language spoken in a certain geographical area that can be distinguished not only by vocabulary, but also by differences in grammar, phonology, and prosody (from the Webster Online Dictionary). Language varieties are often called dialects rather than languages solely because they are not literary languages. Dialects not only differ from a sociocultural angle from standard languages, but also from an educational and behavioral viewpoint. Indeed, dialects are generally acquired implicitly and informally without schooling, and hence used most commonly in a spoken manner. For this reason, the majority of dialects have no orthography, and hence reading a dialect is not a common task.

REFERENCES

- Alexander GE, Crutcher MD ( 1990): Functional architecture of basal ganglia circuits: neural substrates of parallel processing. Trends Neurosci 13: 266–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atallah HE, Frank MJ, O'Reilly RC ( 2004): Hippocampus, cortex, and basal ganglia: insights from computational models of complementary learning systems. Neurobiol Learn Mem 82: 253–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baddeley A, Gathercole S, Papagno C ( 1998): The phonological loop as a language learning device. Psychol Rev 105: 158–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger JD, Perfetti CA, Schneider W ( 2005): Cross‐cultural effect on the brain revisited: universal structures plus writing system variation. Hum Brain Mapp 25: 92–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breitenstein C, Jansen A, Deppe M, Foerster AF, Sommer J, Wolbers T, Knecht S ( 2005): Hippocampus activity differentiates good from poor learners of a novel lexicon. Neuroimage 25: 958–968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner R, Koustall W, Schacter D, Rosen B ( 2000): Functional MRI evidence for a role of frontal and inferior temporal cortex in amodal components of priming. Brain 123: 620–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callan DE, Tajima K, Callan AM, Kubo R, Masaki S, Akahane‐Yamada R ( 2003): Learning‐induced neural plasticity associated with improved identification performance after training of a difficult second language phonetic contrast. Neuroimage 19: 113–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cappa SF, Abutalebi J ( 1999): Subcortical aphasia In: Fabbro F, editor. The concise encyclopedia of language pathology. Oxford: Pergamon Press; p 319–327. [Google Scholar]

- Cardebat D, Demonet JF, De Boissezon X, Marie N, Marie RM, Lambert J, Baron JC, Puel M ( 2003): Behavioral and neurofunctional changes over time in healthy and aphasic subjects: a PET language activation study. Stroke 34: 2900–2906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao L, Weisberg J, Martin A ( 2002): Experience dependent modulation of category‐related cortical activity. Cereb Cortex 12: 545–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen L, Lehericy S, Chochon F, Lemer C, Rivard S, Dehaene S ( 2002): Language‐specific tuning of visual cortex? Functional properties of the visual word form area. Brain 125: 1054–1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coltheart M, Curtis B, Atkins P, Haller M ( 1993): Models of reading aloud: dual‐route and parallel‐distributed‐processing approaches. Psychol Rev 100: 589–608. [Google Scholar]

- Copland D ( 2003): The basal ganglia and semantic engagement: potential insights from semantic priming in individuals with subcortical vascular lesions, Parkinson's disease, and cortical lesions. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 9: 1041–1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale AM ( 1999): Optimal experimental design for event‐related fMRI. Hum Brain Mapp 8: 109–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davachi L, Wagner AG ( 2002): Hippocampal contributions to episodic encoding: insights from relational and item‐based learning. J Neurophysiol 88: 982–990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehaene S, Naccache L, Cohen L, Bihan DL, Mangin JF, Poline JB, Riviere D ( 2001): Cerebral mechanisms of word masking and unconscious repetition priming. Nat Neurosci 4: 752–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehaene S, Le Clec'H G, Poline JB, Bihan DL, Cohen L ( 2002): The visual word form area: a prelexical representation of visual words in the left fusiform gyrus. Neuroreport 13: 321–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demonet JF, Taylorm MJ, Chaix Y ( 2004): Developmental dyslexia. Lancet 363: 1451–1460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehri LC ( 1997): Learning to read and learning to spell are one and the same, almost In: Perfetti CA, Rieben L, Fayol LC, editors. Learning to spell: research, theory, and practice across languages. Mawah, NJ: Erlbaum; p 237–269. [Google Scholar]

- Eichenbaum H ( 2004): Hippocampus: cognitive processes and neural representations that underlie declarative memory. Neuron 44: 109–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis AW, Young AW ( 1988): Human cognitive neuropsychology. London: Erlbaum; p 191–239. [Google Scholar]

- Fiez JA, Petersen SE ( 1998): Neuro‐imaging studies of word reading. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 95: 914–921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiez JA, Balota DA, Raichle ME, Petersen SE ( 1999): Effects of lexicality, frequency, and spelling‐to‐sound consistency on the functional neuroanatomy of reading. Neuron 24: 205–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher P, Buchel C, Josephs O, Friston K, Dolan R ( 1999): Learning related neuronal responses in prefrontal cortex studied with functional neuroimaging. Cereb Cortex 9: 168–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank MJ, Loughry B, O'Reilly RC ( 2001): Interactions between the frontal cortex and basal ganglia in working memory: a computational model. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci 1: 137–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frith U ( 1985): Beneath the surface of developmental surface dyslexia In: Patterson KE, Marshall JC, Coltheart M, editors. Surface dyslexia. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul. [Google Scholar]

- Gabrieli JD, Cohen NJ, Corkin S ( 1988): The impaired learning of semantic knowledge following bilateral medial temporal‐lobe resection. Brain Cogn 7: 157–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gathercole SE ( 1999): Cognitive approaches to the development of short‐term memory. Trends Cogn Sci 3: 410–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green DW ( 2003): The neural basis of the lexicon and the grammar in L2 acquisition In: van Hout R, Hulk A, Kuiken F, Towell R, editors. The interface between syntax and the lexicon in second language acquisition. Amsterdam: John Benjamins; p 197–208. [Google Scholar]

- Habib M ( 2000): The neurological basis of developmental dyslexia: an overview and working hypothesis. Brain 123: 2373–2399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto R, Sakai KL ( 2004): Learning letters in adulthood: visualization of cortical plasticity a new link between orthography. Neuron 42: 311–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henke K, Buck A, Weber B, Wieser HG ( 1997): Human hippocampus establishes associations in memory. Hippocampus 7: 249–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joubert S, Beauregard M, Walter N, Bourgouin P, Beaudoin G, Leroux JM, Karam S, Roch Lecours A ( 2004): Neural correlates of lexical and sublexical processes in reading. Brain Lang 89: 9–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kronbichler M, Hutzler F, Wimmer H, Mair A, Staffen W, Ladurner G ( 2004): The visual word form area and the frequency with which words are encountered: evidence from a parametric fMRI study. Neuroimage 21: 946–953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HS, Fujii T, Okuda J, Tsukiura T, Umetsu A, Suzuki M, Nagasaka T, Takahashi S, Yamadori A ( 2003): Changes in brain activation patterns associated with learning of Korean words by Japanese: an fMRI study. Neuroimage 20: 1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyon GR ( 1995): Toward a definition of dyslexia. Ann Dyslexia 45: 3–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opitz B, Friederici AD ( 2003): Interactions of the hippocampal system and the prefrontal cortex in learning language‐like rules. Neuroimage 19: 1730–1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opitz B, Friederici AD ( 2004): Brain correlates of language learning: the neuronal dissociation of rule‐based versus similarity‐based learning. J Neurosci 24: 8436–8440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Packard M, Knowlton B ( 2002): Learning and memory functions of the basal ganglia. Annu Rev Neurosci 25: 563–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Packard MG, Hirsh R, White NM ( 1989): Differential effects of fornix and caudate nucleus lesions on two radial maze tasks: evidence for multiple memory systems. J Neurosci 9: 1465–1472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulesu E, Frith CD, Frackowiak RSJ ( 1993): The neural correlates of the verbal component of working memory. Nature 362: 342–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulesu E, McCrory E, Fazio F, Menoncello L, Brunswick N, Cappa SF, Cotelli M, Cossu G, Corte F, Lorusso M, Pesenti S, Gallagher A, Perani D, Price C, Frith CD, Frith U ( 2000): A cultural effect on brain function. Nat Neurosci 3: 3–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perani D, Abutalebi J ( 2005): Neural basis of first and second language processing. Curr Opin Neurobiol 15: 202–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perfetti CA ( 1992): The representation problem in reading acquisition In: Gough PB, Ehri LC, Treiman R, editors. Reading acquisition. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; p 145–174. [Google Scholar]

- Petersen SE, Fox PT, Posner MI, Mintum M, Raichle ME ( 1988): Positron emission tomography studies of the cortical anatomy of single‐word processing. Nature 331: 585–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poldrack RA, Prabakharan V, Seger C, Gabrieli J ( 1999): Striatal activation during cognitive skill learning. Neuropsychology 13: 564–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poldrack RA, Clark J, PareBlagoev EJ, Shohamy D, Moyano JC, Myers C, Gluck MA ( 2001): Interactive memory systems in the human brain. Nature 413: 546–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posner MI, Abdullaev Y, McCandliss BD, Sereno SE ( 1999): Neuroanatomy, circuitry and plasticity of word reading. Neuroreport 10: 12–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price CJ ( 2000): The anatomy of language: contributions from functional neuroimaging. J Anat 197: 335–359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price CJ, Devlin JT ( 2003): The myth of the visual word form area. Neuroimage 19: 473–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price CJ, Mechelli A ( 2005): Reading and reading disturbance. Curr Opin Neurobiol 15: 231–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price CJ, Wise RJ, Frackowiak RS ( 1996): Demonstrating the implicit process of visually presented words and pseudowords. Cereb Cortex 6: 62–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pugh KR, Shaywitz BA, Shaywitz SE, Constable RT, Skudlarski P, Fulbright RK, Bronen RA, Shankweiler DP, Katz L, Fletcher JM, Gore JC ( 1996): Cerebral organization of component processes in reading. Brain 119: 1221–1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raboyeau G, Marie N, Balduyck S, Gros H, Démonet JF, Cardebat D ( 2004): Lexical learning of the English language: a PET study in healthy French subjects. Neuroimage 22: 1808–1818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raichle ME ( 1994): Images of the mind: studies with modern imaging techniques. Annu Rev Psychol 45: 333–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossion B, Schiltz C, Crommelinck M ( 2003): The functionally defined right occipital and fusiform “face areas” discriminate novel from visually familiar faces. Neuroimage 19: 877–883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarborough HS ( 1990): Very early language deficits in dyslectic children. Child Dev 61: 1728–1743. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seymour PHK ( 1997): Foundations of orthographic development In: Perfetti C. Rieben L, Fayol M, editors. Learning to spell. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Share DL ( 1995): Phonological recoding and self‐teaching: sine qua non of reading acquisition. Cognition 55: 151–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaywitz BA, Shaywitz SE, Pugh KR, Mencl WE, Fulbright RK, Skudlarski P, Constable RT, Marchione KE, Fletcher JM, Lyon GR, Gore JC ( 2002): Disruption of posterior brain systems for reading in children with developmental dyslexia. Biol Psychiatry 52: 101–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson JR Jr, Snyder AZ, Gusnard DA, Raichle ME ( 2001): Emotion‐induced changes in human medial prefrontal cortex. I. During cognitive task performance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98: 683–687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperling R, Chua E, Cocchiarella A, Rand‐Giovannetti E, Poldrack R, Schacter DL, Albert M ( 2003): Putting names to faces: successful encoding of associative memories activates the anterior hippocampal formation. Neuroimage 20: 1400–1410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Squire LR, Stark CE, Clark RE ( 2004): The medial temporal lobe. Annu Rev Neurosci 27: 279–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swan D, Goswami U ( 1997): Picture naming deficits in developmental dyslexia: the phonological representation hypothesis. Brain Lang 56: 334–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan LH, Spinks JA, Gao JH, Liu HL, Perfetti CA, Xiong J, Stofer KA, Pu Y, Liu Y, Fox PT ( 2000): Brain activation in the processing of Chinese characters and words: a functional MRI study. Hum Brain Mapp 10: 16–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan LH, Feng CM, Fox PT, Gao JH ( 2001): An fMRI study with written Chinese. Neuroreport 12: 83–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan LH, Spinks JA, Feng CM, Siok WT, Perfetti CA, Xiong J, Fox PT, Gao JH ( 2003): Neural systems of second language reading are shaped by native language. Hum Brain Mapp 18: 155–166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan LH, Laird AR, Li K, Fox PT ( 2005): Neuroanatomical correlates of phonological processing of Chinese characters and alphabetic words: a meta‐analysis. Hum Brain Mapp 25: 83–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiel CM, Shanks DR, Henson RN, Dolan RJ ( 2003): Neuronal correlates of familiarity‐driven decisions in artificial grammar learning. Neuroreport 14: 131–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson‐Schill SL, D'Esposito M, Kan IP ( 1999): Effects of repetition and competition on activity in left prefrontal cortex during word generation. Neuron 23: 513–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trépanier L, Saint‐Cyr J, Lozano A, Lang A ( 1998): Hemisphere‐specific cognitive and motor changes after unilateral posteroventral pallidotomy. Arch Neurol 55: 881–883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turkeltaub PE, Gareau L, Flowers DL, Zeffiro TA, Eden GF ( 2003): Development of neural mechanisms for reading. Nat Neurosci 6: 767–773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Turennout M, Ellmore T, Martin A ( 2000): Long lasting cortical plasticity in the object naming system. Nat Neurosci 3: 1329–1334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallesch CW, Papagno C ( 1988): Subcortical aphasia In: Rose FC, Whurr R, Wyke MA, editors. Aphasia. London: Whurr; p 256–287. [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Sereno JA, Jongman A, Hirsch J ( 2003): fMRI evidence for cortical modification during learning of Mandarin lexical tone. J Cogn Neurosci 15: 1019–1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeineh MM, Engel SA, Thompson PM, Brookheimer SY ( 2003): Dynamics of the hippocampus during encoding and retrieval of face‐name pairs. Science 299: 577–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]