Abstract

The neural basis of human attachment security remains unexamined. Using event‐related functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and simultaneous recordings of skin conductance levels, we measured neural and autonomic responses in healthy adult individuals during a semantic conceptual priming task measuring human attachment security “by proxy”. Performance during a stress but not a neutral prime condition was associated with response in bilateral amygdalae. Furthermore, levels of activity within bilateral amygdalae were highly positively correlated with attachment insecurity and autonomic response during the stress prime condition. We thereby demonstrate a key role of the amygdala in mediating autonomic activity associated with human attachment insecurity. Hum Brain Mapp, 2005. © 2005 Wiley‐Liss, Inc.

Keywords: fMRI, human attachment, semantic conceptual priming, amygdala, ventral striatum, middle temporal gyrus, insula, skin conductance level, XBAM

INTRODUCTION

Secure interpersonal attachment during primate infancy, the equivalent of vertebrate filial imprinting [Insel and Young,2001], is critical for the formation of enduring interpersonal relationships in adulthood [Kraemer,1992]. Whereas securely attached individuals possess greater self‐confidence and improved emotion regulation, insecurely attached individuals are more stress‐prone and inclined toward emotional disturbance [Lemche et al.,2004; Lovic et al.,2001; Spangler and Grossmann,1993; Spangler and Schieche,1998].

Heightened sympathetic nervous system activity (heart rate increase and cortisol secretion) has been established as a feature of insecure attachment [Spangler and Grossmann,1993; Spangler and Schieche,1998]. However, the neural basis of human attachment remains relatively unexplored. Previous findings indicate that mammalian attachment is mediated by the hormone oxytocin, which binds predominantly to the amygdala and ventral striatum [Ferguson et al.,2001; Insel and Young,2001; Loup et al.,1991; Tomizawa et al.,2003]. Furthermore, these structures have been postulated to correspond to the intermediate medial hyperstriatum ventrale, which mediates avian filial imprinting [Horn,1985; McCabe and Nicol,1999]. These findings therefore suggest a role for the amygdala and ventral striatum in human attachment [Insel,1997; Loup et al.,1991].

We aimed to examine the neurophysiological basis of human attachment security and in particular, to determine the roles of the amygdala and ventral striatum in this process. We simultaneously measured neural and autonomic responses (skin conductance levels) in healthy adults during performance of a semantic conceptual prime paradigm previously construct‐validated in two longitudinal cohort samples for the study of infantile and adult attachment [Maier et al.,2004]. This paradigm comprises two conditions, a neutral and a stress prime condition. Differential reaction times had been found to be discriminative of secure and insecure levels of attachment. Individuals view subliminal presentations of either stress sentence or neutral sentence primes, and then respond to statements describing self‐centered or other‐centered information, with which they agree or disagree by response button press. More insecurely attached individuals have been reported as demonstrating a greater difference in mean reaction time for the neutral minus the stress prime condition [Maier et al.,2004].

Previous studies have repeatedly highlighted the role of the amygdala in the response to emotionally salient material in humans [Calder et al.,2001; Morris et al.,1998; Whalen et al.,2001]. We therefore predicted that performance of the stress but not the neutral prime condition would be associated with a response within the amygdala in all individuals, irrespective of the level of attachment insecurity. However, after evidence from developmental research [Lemche et al.,2004; Lovic et al.,2001; Spangler and Grossmann,1993; Spangler and Schieche,1998] we predicted that the magnitude of the amygdalar response during performance of the stress prime condition would be positively correlated with the level of attachment insecurity, as measured by the mean reaction time difference between the two prime conditions, and positive correlations would occur between both of these measures and the magnitude of autonomic response, as measured by skin conductance level. We also predicted a positive correlation between the magnitudes of ventral striatal response, attachment insecurity, and autonomic response during the stress prime condition [Loup et al.,1991].

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Participants

Twelve healthy individuals (age, 27.25 ± 4.95 yr; education, 13.91 ± 2.02 yr; seven males) participated in the study. Right‐handedness was verified with the Edinburgh Handedness Inventory [Oldfield,1971]. All individuals also completed ratings of state and trait anxiety [Spielberger,1983] on the day of testing. Informed consent was obtained from all participants following the Declaration of Helsinki [World Medical Association, 1991]. The experimental procedure was approved by the Ethics Committee (Research) of the Institute of Psychiatry, London. All participants had normal vision, were not taking any medication, and had been negatively screened for psychiatric, neurologic, and substance abuse problems in the past and present.

Behavioral Task

Individuals were shown two series of 32 sentence statements describing self‐centered or other‐centered information, with which they were asked to agree or disagree by response button press (for examples, see Fig. 1). Before presentation of the target sentences, individuals were presented eight times with a subliminally displayed sentence prime. This sentence contained either nonsense information (neutral prime condition) or descriptions of unpleasant attachment experiences (stress prime condition). The two types of sentence had an identical number of words. Individuals were instructed in advance about the nature of the task but were unaware of the purpose of the study. The mean reaction time difference between performance of the two conditions, specifically the difference in mean reaction for the neutral minus the stress prime condition, has been demonstrated to possess concordant construct‐validity both with infantile attachment classification in the Strange Situation Procedure (SSP) and adult attachment representation in the Adult Attachment Interview (AAI). A greater difference in mean reaction time was associated with a greater level of attachment insecurity [Maier et al.,2004]. The initial sentence prime was presented subliminally for 30 ms followed by a checkerboard mask for 100 ms. This procedure was repeated on seven further occasions. For these stimuli, the previously determined perceptual threshold was 71.3 ms with a range of 45–165 ms [Maier et al.,2004]. The prime sequence was introduced as a “test for reading capacities” to subjects, and they were instructed to respond by button press once they were able to understand the content displayed. Because no button presses were recorded, we could be confident that individuals were unaware of the content of each prime sentence in each condition. Individual reaction times to visual presentation of 64 target sentences, each of 2‐s duration, were measured. Presentation order of the two conditions was counterbalanced randomly across individuals. The order of individual sentences was identical in both conditions to allow comparison of neural responses between conditions.

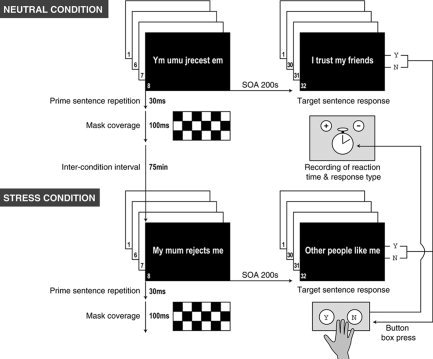

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the design of the attachment semantic priming task. The attachment priming task comprised two matching conditions differing only in the content of eight subliminally presented prime sentences (30 ms). Prime sentences in the stress condition (lower panel) were eight repetitions of a statement evoking separation distress. In the neutral condition (top panel), this was a nonsense anagram of the stress prime sentence. Prime sentences were backwardly masked by presentation of a checkerboard stimulus (100 ms). In each condition after the prime sentences, subjects responded (“yes” or “no”) by button press to 32 visually presented target sentences, each of 2‐s duration, evoking autobiographical recall of attachment‐related experiences. The interstimulus interval varied according to a Poisson distribution. Reaction times were measured. The presentation order of the two conditions was counterbalanced across subjects. The conditions were separated by a minimum of 60 m. The order of individual sentences was identical in both conditions to allow comparison of neural responses between conditions.

Stimulus Presentation

Stimuli were presented via back‐projection using an LCD projector and a semitransparent screen, which subjects watched through a mirror mounted on the magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) head coil (visual angle ≤ 8 degrees). All stimuli were presented in white upon a black computer screen in 60‐point Helvetica font. A maximum of eight letters appeared within presented words, and all single statements were composed of three‐ to four‐word sentences. The interstimulus interval (ISI) for presentation of the target sentences was varied according to a Poisson distribution (M = 5.09 s, range 2–10 s), whereas stimulus presentation was kept constant at 2 s, as in the validation study. During the ISI, subjects viewed a fixation cross in the middle of the computer screen. The total duration of the priming sequence was 61,532 ms and that of the target sentences was 180,596 ms. The mean stimulus onset asynchrony (SOA) between the priming sequence and target sentence blocks was 209.31 s (± 24.26 s, range 31–551 s). As in the validation study, both experimental conditions were kept apart for a minimum of 60 m, during which other functional MRI (fMRI) experiments were carried out.

Experimental Manipulation of Prime Content and Repetition

To ensure that the between‐condition reaction time differences were not caused by different levels of semantic processing per se, an additional condition with neutral sentence primes, comprising sentences with neutral rather than negative content, had been included in the original validation study. There were no associations between attachment insecurity measured by SSP, AAI, and differences in reaction time between performance of this neutral semantic prime condition and the neutral nonsense prime condition [Maier et al.,2004]. Furthermore, manipulation of the number of presentations of the sentence prime from one to sixteen had revealed that eight repetitions yielded the most consistent findings regarding the association between reaction time difference between the two conditions and measures of attachment insecurity [Maier et al.,2004].

Psychophysiological Data Acquisition

Measurement of skin conductance level (SCL) was made during task performance. Following standard procedures, skin conductance was recorded from the medial phalanges of index and middle fingers of the nondominant hand after individuals had undergone uniform soap hand‐washing procedures and thermal adaptation to the scanner environment. Standard AgCl electrodes and commercial K‐Y (Johnson & Johnson) isotonic electrode jelly were used, and electrodes were secured with surgical fixing bands.

Changes in SCL were recorded for all individuals during task performance inside the MRI scanner. Using a skin‐conduction coupler, analogue‐to‐digital conversion, and preamplification, the signal was processed by a PSYLAB (Cambridge, MA) SC5SA preamplifier, a SC5AL amplifier, and real‐time PSYLAB online signal processing software. These devices employ a 24‐bit A/D converter, filter the response signal at 10 Hz to prevent aliasing, and have an output range 0–100 MicroSiemens (μS). SCL was then sampled at 100 Hz without further compression and stored offline serially, including stimulus presentation points. Security measures were included to prevent electric shocks, radiofrequency (RF) burning, and to protect SCL signals from scanner‐induced magnetic distortion using screened cables. Shielding of the wires received a 5.6‐kΩ correction by resistors that produced a stable 1% shift of the signal. The cable was led from the magnetically shielded scanner environment through a Faraday cage, and the signal filtered at 1,000 pF by capacitors to a copper cap before signal processing. Due to computer malfunction, SCL data were lost for two individuals, so that SCL results are based on the data of 10 individuals.

Analysis of Psychophysiological Data

Latency windows of 0–2‐s poststimulus (target sentence) onset were used to ensure that SCL was not contaminated by nonspecific skin conductance responses. The rationale for using mean SCL was that this variable is more sluggish by nature and thus less prone to be influenced by nonspecific skin conductance responses, and that it can be mathematically normalized to account for interindividual variation of baselines and response magnitudes. The resulting measure, relative SCL, is thus a more veridical measure of arousal than are uncorrected electrodermal responses. The SCL within this duration was analyzed using a custom‐made software program, SC‐ANALYZE (Neuroimaging Research, Institute of Psychiatry, London, UK). Mean SCLs (in μS) per individual were averaged across all 2‐s periods after presentation onset of each target sentence in each condition. Relative SCL values were then computed to control for interindividual differences in SCL range by inclusion of individual minima and maxima through application of the formula:

where Φ is the corrected (relative) value, SCLx is the actual value, SCLmin is the minimal value, and SCLmax is the maximal value. Following standard methodology, each individual's relative SCL was log‐transformed to ensure normal distribution by adding a constant before logarithmic transformation ([20 + rSCL] • ln). These values were then used in all subsequent analyses.

Functional MR Image Acquisition

A 1.5‐Tesla GE Neurovascular Signa MR system (General Electric, Milwaukee, WI) fitted with 40 mT/m high‐speed gradients and a quadrature birdcage head‐coil for RF transmission and reception was used to acquire noncontiguous near‐axial multislice T2*‐weighted gradient‐echo echo‐planar image (EPI) data providing whole‐brain coverage (16 slices, in‐plane resolution 3.75 mm, slice thickness 7 mm, gap 0.7 mm, 642 matrix, field of view (FOV) 24 cm, echo time (TE) 40 ms, and flip angle α 70 degrees). The repetition time (TR) was 1,500 ms per volume. An automated shimming routine was used before the first EPI images were acquired to optimize magnetic field homogeneity. In each individual, 180 (prime) and 121 (target) image volumes were obtained in neutral and stress conditions, respectively. Asynchrony between stimulus presentations and scan volume acquisitions enabled jittered sampling of time points over the course of blood oxygen level‐dependent (BOLD) responses to each stimulus. A 43‐slice high‐resolution inversion recovery (EPI) data set was also acquired parallel to the intercommissural anterior–posterior commissure (AC–PC) line for subsequent Talairach mapping (TR 12,000 ms, TE 73 ms, 1282 matrix, FOV 24 cm, in‐plane resolution 1.5 mm, slice thickness 3 mm, interslice gap 0.3 mm, and α 90 degrees). Rigid body motion in three spatial dimensions during T2* data acquisition was estimated and corrected by a two‐stage procedure, realignment followed by regression [Bullmore et al.,1999].

Functional MRI Data Analyses

The statistical inference software package Brain Activation Mapping (XBAM; Brain Image Analysis Unit, Institute of Psychiatry; online at http://www.brainmap.it) was used to analyze the EPI images obtained in response to the target sentences in each condition. Due to distorting metallic artifact, fMRI data of one female participant had to be discarded. An event‐related analysis was carried out to identify differences in BOLD response to target sentences versus baseline in each condition, regressing the corrected time‐series data on a linear model produced by convolving each contrast vector to be studied with two Poisson functions parameterizing hemodynamic delays of 4 and 8 s.

Generic Brain Activation Maps

The distributions of the same statistics under the null hypothesis of no experimental effect were then calculated by Daubechies wavelet‐based resampling [Breakspear et al.,2003,2004] of the time series at each voxel and refitting the models to the resampled data [Bullmore et al.,2001; Fadili and Bullmore,2002]. This resulted in 10 parametric maps (for each individual at each plane) of the sum‐of‐square quotient (SSQ) estimated under the null hypothesis that SSQ is not determined by periodic stimulation. SSQ reflects a ratio measure of the model fit for BOLD signal against residual noise, similar to the F test in analysis of variance (ANOVA)‐type statistics. For each voxel in the observed image, its probability under the null hypothesis in terms of time series activity was combined with its probability under the null hypothesis in terms of time spatial clustering. Voxels with such a spatiotemporally combined probability of false positive activation of P < 0.0004 were regarded as activated in a resulting generic brain activation map (GBAM). All parametric maps of SSQ were then registered in the standard space of Talairach and Tournoux [1988] to produce median activation maps as described previously [Brammer et al.,1997].

Conjunction Analysis

Regions of activation significantly common to both conditions were determined using cluster conjunction analysis. The search volume for the conjunction analysis was limited to clusters activated during each of the two conditions. The voxel‐wise probability of false‐positive test was P < 0.0001, with one false‐positive voxel expected per whole brain volume (Table I).

Table I.

Regions activated during task performance

| Region | Side | No. voxels | BA | Talairach coordinates (x, y, z) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regions activated in both conditions | |||||

| Ventrolateral PFC | L | 9 | 47 | −52, 18, −2 | 0.0028 |

| Postcentral gyrus | L | 65 | 1–3 | −40, −19, 48 | 0.00010 |

| Precentral gyrus | L | 2 | 4 | −40, 7, 31 | 0.0033 |

| Inferior parietal lobule | L | 54 | 40 | −54, −22, 37 | 0.00079 |

| Middle occipital gyrus | R | 19 | 18 | 36, −78, −2 | 0.00063 |

| Lingual gyrus | R | 9 | 19 | 36, −77, −9 | 0.0011 |

| L | 11 | 19 | −42, −73, −3 | 0.00063 | |

| Superior temporal gyrus | L | 13 | 22 | −61, −37, 9 | 0.0030 |

| Middle temporal gyrus | L | 3 | 21 | −47, −44, 4 | 0.0035 |

| Dorsal mid‐anterior cingulate gyrus | R | 6 | 24 | 8, 20, 31 | 0.0044 |

| Stress prime condition only | |||||

| Dorsolateral PFC | L | 8 | 45 | −40, 20, 9 | 0.000007 |

| Ventrolateral PFC | R | 2 | 47 | 50, 20, −13 | 0.0011 |

| Middle occipital gyrus | L | 20 | 19 | −40, −60, −7 | 0.000007 |

| Cuneus | R | 6 | 31 | 4, −69, 9 | 0.00014 |

| Middle temporal gyrus | R | 4 | 21 | 47, −63, −2 | 0.00085 |

| Superior temporal gyrus | L | 14 | 22 | −53, −52, 15 | 0.000029 |

| Inferior parietal lobule | R | 3 | 40 | 53, −33, 31 | 0.00015 |

| Insula | L | 6 | — | −36, 20, 4 | 0.000007 |

| Putamen | L | 4 | — | −17, 5, −7 | 0.0016 |

| Amygdala | R | 3 | — | 15, −4, −13 | 0.00031 |

| L | 2 | — | −25, −7, −18 | 0.002 | |

| Neutral prime condition only | |||||

| Dorsolateral PFC | R | 6 | 9 | 17, 42, 18 | 0.0034 |

| Inferior frontal gyrus | L | 12 | 44 | −47, 4, 36 | 0.00023 |

| Precentral gyrus | R | 3 | 4 | 50, 0, 31 | 0.00048 |

| Fusiform gyrus | L | 35 | 20 | −25, −37, −18 | 0.0018 |

| Cuneus | R | 3 | 19 | 0, 73, 31 | 0.00032 |

| Middle occipital gyrus | L | 15 | 19 | −43, −69, −7 | 0.00023 |

| Middle temporal gyrus | L | 8 | 21 | −57, −50, 9 | 0.00006 |

| Superior temporal gyrus | L | 6 | 22 | −53, −39, 4 | 0.000029 |

| Thalamus | L | 8 | — | −4, −26, 4 | 0.00019 |

| Inferior parietal lobule | R | 2 | 40 | 40, −52, 42 | 0.0018 |

| Anterior insula | L | 4 | — | −40, 13, −2 | 0.00067 |

| Putamen | L | 3 | — | −21, −7, 4 | 0.00061 |

Talairach coordinates are for the cluster center, not for the peak of activation. The primary threshold for activation at each single voxel was set at P < 0.0004. In GBAMs (Stress prime condition only and Neutral prime condition only), cluster‐level threshold was P < 0.005.

BA, Brodmann area; PFC, prefrontal cortex.

Correlational Analyses

The mean reaction time difference for the neutral minus the stress prime conditions has been validated as a measure of attachment insecurity [Maier et al.,2004]. To examine neural regions whose magnitude of response correlated positively with this measure of attachment insecurity during performance of each condition, overlap maps were produced combining regions activated by performance of each condition, and regions correlating positively (P < 0.0001, fewer than one false‐activated voxel expected over the whole brain) with this measure of attachment insecurity. Similar correlational analyses were carried out to determine neural regions whose magnitude of response correlated positively with the measure of autonomic response, each individual's mean SCL value, corrected for individual maxima and minima. Correlational analyses were also carried out between measures of attachment insecurity and autonomic response, using as the measure of autonomic response each individual's mean SCL value, corrected for individual maxima and minima and log‐transformed to ensure normal distribution.

RESULTS

Reaction Time Data

For the neutral condition, the mean reaction time (mRT ± standard error of the mean [SEM[) was 1,122.41 ± 56.17 ms (range 821.53–1,453.59 ms). For the stress condition, the mRT was 1,122.06 ± 26.54 ms (range 1,006.28–1,329.94 ms). Mean RT difference (mean ΔRT) for the neutral minus the stress condition was 0.35 ± 61.22 ms (range −279.39–366.19 ms). These ranges of mRT and mean ΔRT were highly similar to those observed in the original validation study (see below), in which individuals with larger (positive) ΔRTs were those with greater attachment insecurity on the SSP and AAI [Maier et al.,2004]. The present sample resembled the two validation cohorts in subject characteristics, specifically with regard to age (27 vs. 20/23 yr) and gender distributions.

Examination of ΔRTs

The potential confounding effects of age, sex, socioeconomic status (SES), education level, and scanning date upon mean ΔRTs were examined. Age and education level were not significantly correlated with mean ΔRT. There was a near‐significant effect of sex upon (F[1,12] = 4.77, P = 0.05, r = 0.59) and a significant correlation with SES (r = 0.57, P < 0.03) with mean ΔRT. ANCOVA covarying for sex, SES, and presentation order of the two conditions (all nonsignificant), demonstrated a main effect of attachment status, defined as insecure versus secure using the cut‐off criterion derived from the SSP‐AAI and employed previously in the validation study, upon mean ΔRT (F[1,12] = 7.98, P < 0.04). Because the magnitude of the experimental effect and its significance in mean ΔRT was not altered after covarying for the above variables, the robustness of mean ΔRT against the possible confounding influences was thus demonstrated. We could therefore be confident that the magnitude of mean ΔRT reflected the degree of attachment security of participants in the current study, with those demonstrating larger mean ΔRT being more insecurely attached.

Validation Studies of the Attachment Task

The attachment priming task had been piloted and validated in two longitudinal developmental cohorts (initial investigations funded by the Volkswagen Foundation and the German Research Community, DFG, conducted by Drs. Klaus E. and Karin Grossmann) in Bielefeld and Regensburg, Germany [Maier et al.,2004]. In a subset of the Regensburg cohort (n = 19), sampled from birth in 1978, the present task was administered between April and June 1998. The attachment (secure/insecure) distributions for these subjects in SSP (SSP19 1979) and AAI (AAI19 1995) were 11/8 and 13/6, respectively. In the Bielefeld cohort (n = 38), sampled from birth in 1975, the present task was validated from August to October 1998. The attachment distributions for these subjects in the SSP38 (1976) and the AAI37 (1992/93) were 11/24 (+ 3 unclassified) and 20/17, respectively. There were some unclassified or missing cases, as well as changes in attachment status.

Experimental Details of the Validation Study

The two conditions of the task were presented 60 min apart. This temporal distance had been established to be optimal for discrimination among differential prime effects. In each condition, target sentences were presented 7 s after presentation of the eight prime sentences. As in the present experiment, prime presentation lasted 30 ms, followed by 100‐ms checkerboard masking. The ISI for the target sentences was 3 s. Each target sentence was presented for 2 s. Subjects viewed all stimuli on a 50 × 250 mm computer screen (refreshment rate: 75 Hz) from a distance of 70 cm. The mRT for all subjects in the neutral prime condition was 1,245.12 ms, and 1,253.33 ms in the stress prime condition. For stable insecure subjects (SSPins + AAIins), mRTstress = 1,175 ms and mRTneutral = 1,270 ms; for stable secure subjects (SSPstress + AAIstress), mRTstress = 1,175 ms and mRTneutral = 1,300 ms. The ΔmRT variability between stable secure and stable insecure subjects was >24 ms [Maier et al.,2004].

Replication of the Validation Study

In the validation cohort, a cut‐off value of ΔRT >24 ms was employed to discriminate individuals with insecure (infantile/adult) from those with secure (infantile/adult) attachment (see above). With this criterion, the present sample comprised seven putatively secure and five putatively insecure subjects, thus being in line with typical attachment distributions (∼60:40) found in general populations worldwide. Applying the cut‐off criterion, putatively insecure mRTs were 1,148.56 ± 30.14 ms and 1,079.01 ± 28.09 ms in neutral and stress conditions, respectively. Putatively secure had mRTs of 1,103.67 ± 41.23 ms in the neutral and 1,152.52 ± 37.34 ms in the stress condition. Mean ΔRT differences between the two conditions were 68.54 ±14.94 ms for putatively insecurely attached and −48.71 ± 38.74 ms for putative securely attached.

Psychophysiological Data

The mean SCL for the neutral condition was 1.36 ± 0.29 μS, and for the stress condition, 1.59 ± 0.41 μS. Minimum SCL were 1.21 ± 0.21 μS (neutral condition) and 1.26 ± 0.22 μS (stress condition). Maximum SCL were 1.38 ± 0.25 μS (neutral condition) and 1.56 ± 0.38 μS (stress condition). Relative SCL were 0.48 ± 0.08 μS (neutral condition) and 0.32 ± 0.04 μS (stress condition). There were significant correlations between the two conditions for mean SCL (r = 0.88, P < 0.008), minimum SCL (r = 0.85, P < 0.002), maximum SCL (r = 0.87, P < 0.001), and relative SCL (r = 0.66, P < 0.05). These variables were examined for the potential confounding effects of social (education, socioeconomic group), presentation order, and biological (sex, age, scanning date, time of data acquisition) factors. There were no significant effects of these factors upon any of the SCL variables.

Voxel‐Cluster Conjunction Analysis of Neural Responses for the Two Conditions

We wished to determine the activated regions common to both conditions, and those regions activated specifically during the stress and the neutral prime conditions. Generic brain activation maps [Brammer et al.,1997] representing group‐averaged neural responses during performance of both experimental conditions compared to baseline fixation cross were created with a voxel‐wise probability of false‐positive voxels (type I error) of P < 0.0004. At this level of statistical inference, we would expect one or fewer false‐positive voxels to be activated per slice of the generic brain activation map containing approximately 14,000 voxels. A voxel‐cluster conjunction analysis was carried out to examine generically activated regions common to both conditions (voxel‐wise probability of a false‐positive test: P < 0.0001, fewer than one false‐activated voxel expected over the entire brain volume). These regions included left precentral (Brodmann area [BA] 4) and postcentral (BA 1–3) gyri, left inferior parietal cortex (BA 39/40), bilateral visual (BA 17–19), and temporal cortical (BA 21/22), regions, left ventrolateral prefrontal cortex (BA 47), and right anterior cingulate gyrus (BA 24; Table I).

Between‐Condition Differences in Other Activated Regions

In addition to the above regions, regions activated during performance of the stress prime condition included bilateral amygdalae, left anterior insula, and left putamen. Areas within bilateral prefrontal (BA 45) and visual cortices not identified in the conjunction analysis, and the right middle temporal (BA 21) and inferior parietal (BA 40) cortices, were also activated during this condition (Table I). In addition to regions identified in the conjunction analysis, regions activated during performance of the neutral prime condition included left anterior insula, left putamen and left thalamus, right inferior parietal cortex (BA 40) and right precentral gyrus (BA 4), areas within bilateral prefrontal (BA 46), and visual cortices not identified in the conjunction analysis (Table I).

Correlational Analyses Between Attachment Insecurity and Neural Response

Regions whose magnitude of response during performance of the stress prime condition correlated positively (P < 0.0001, fewer than one false‐activated voxel expected over the whole brain) with the measure of attachment insecurity, the mean reaction time difference for the neutral minus the stress prime condition, included bilateral amygdalae, left putamen/nucleus accumbens, left ventrolateral prefrontal cortex (BA 47), right dorsal anterior cingulate gyrus (BA 24), left middle and superior temporal gyri (BAs 21/22), and left inferior parietal cortex (BA 40; Fig. 2 and see Fig 4A,B). During performance of the neutral prime condition, there were no regions in which the magnitude of response correlated positively with the measure of attachment insecurity. There were no significant correlations between the magnitudes of neural response in any regions and state or trait anxiety in either of the two conditions.

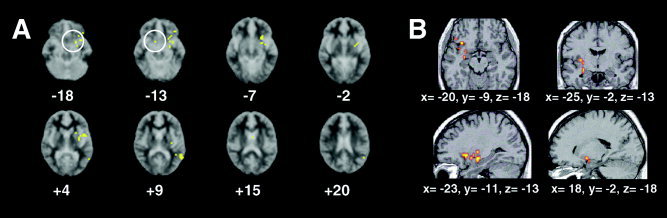

Figure 2.

Correlation between neural responses and attachment insecurity during performance of the stress prime condition. Correlation overlap images are demonstrated for neural regions whose magnitude of response during performance of the stress prime condition correlated positively with mean reaction time difference (ΔRT;) for the neutral minus the stress prime condition, the measure of attachment insecurity (yellow regions; P < 0.0001). In A (left) are axial slices displaying these regions. Numbers below each slice indicate Talairach z‐coordinates (in mm) from inferior (top left) to superior (bottom right) slices. Overlap regions (Talairach coordinates x, y, z) in the stress condition included bilateral amygdalae (encircled; −25, −7, −18, and 15, −4, −13), left ventral putamen/nucleus accumbens (−17, 5, −7), left ventrolateral prefrontal cortex (Brodmann area [BA] 47; −31, 16, −18), left superior temporal gyrus (BA 22; −61, −37, 9), and left middle temporal gyrus (BA 21; −47, −44, 4). Other regions not shown included left inferior parietal cortex (BA 40; −54, −22, 37) and right mid‐anterior cingulate gyrus (BA 24; 8, 20, 31). Sides are reversed in these slices according to radiological image format. In B (right) are 3‐D views predominantly of peaks of left‐sided amygdalar activation correlating positively with mean ΔRT (coordinates underneath each image). Top left and right, axial and coronal views, respectively. Bottom left and right: sagittal views of activation in left and right amygdala, respectively. Images are shown in neurological format.

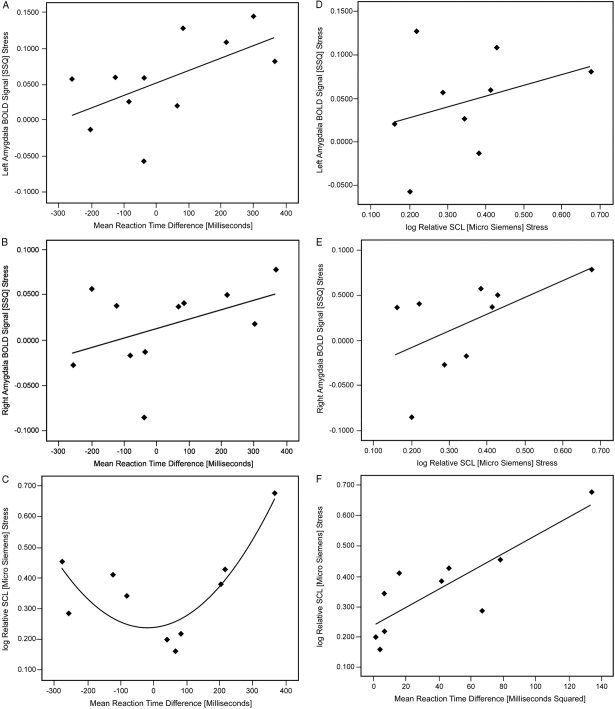

Figure 4.

Regression scatterplots demonstrating correlations between left and right amygdalar responses and mean reaction time difference (ΔRT;), mean ΔRT and log relative skin conductance level (rSCL), and between left and right amygdalar responses and log rSCL during performance of the stress prime condition. A: The scatterplot depicts left amygdala sum‐of‐square quotient (SSQ), the measure of blood oxygenation level‐dependent (BOLD) signal against residual noise, with magnitude of mean ΔRT, the measure of attachment insecurity (R = 0.34, r = 0.46, P < 0.079). B: The scatterplot displays SSQ in the right amygdala, the measure of BOLD signal against residual noise, with mean ΔRT, the measure of attachment insecurity (R = 0.19, r = 0.49, P < 0.063). These scatterplots demonstrate positive correlations between the magnitude of mean ΔRT and that of SSQ. C: The scatterplot depicts the U‐formed association between the magnitude of mean ΔRT and log rSCL, the measure of autonomic response (R = 0.72, r = 0.59, P < 0.006). This relationship can preferably be transformed into a linear relationship by squaring as depicted in F (R = 0.69, r = 0.84, P < 0.003). D, E: Scatterplots demonstrating positive correlations between SSQ in left (R = 0.11, r = 0.33, P < 0.019) and right (R = 0.32, r = 0.57, P < 0.056) amygdalae, respectively, and log rSCL.

Correlational Analyses Between Attachment Insecurity and Autonomic Response

During performance of the stress prime condition, there was a positive U‐formed association representing a quadratic trend between autonomic response, each individual's log‐transformed mean SCL value corrected for individual maxima and minima, and the previous measure of attachment insecurity within the group (R = 69, r = 0.84, P < 0.003, n = 10; see Fig. 4C,F). There was no correlation between these measures in the group during performance of the neutral prime condition. There were no significant correlations between this measure of autonomic response and state or trait anxiety in either of the two conditions.

Correlational Analyses Between Neural and Autonomic Response

Positive correlations between magnitudes of autonomic response (relative SCL) and neural response (P < 0.0001, fewer than one false‐activated voxel expected over the whole brain) were demonstrated within bilateral amygdalae, left‐sided ventrolateral prefrontal cortex (BA 47), middle temporal gyrus (BA 21), anterior insula, inferior parietal cortex (BA 40; Figs. 3 and 4D,E). Scatterplots as depicted in Figure 3A–F furthermore excluded the possibility that the reported correlations could be biased by outliers.

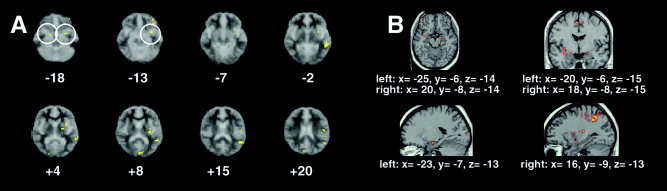

Figure 3.

Correlation between neural and autonomic responses during performance of the stress prime condition. Correlation overlap images are demonstrated for neural regions whose magnitude of response during performance of the stress prime condition correlated positively with log relative skin conductance level (rSCL), a measure of autonomic response (yellow regions; P < 0.0001). In A (left) are axial slices displaying these regions. Numbers below each slice indicate Talairach z‐coordinates (in mm) from inferior (top left) to superior (bottom right) slices. Overlap regions (x, y, z) in the stress condition included bilateral amygdalae (15, −4, −13, and −25, −7, −18), left ventrolateral prefrontal cortex (Brodmann area [BA] 47; −43, 27, −13), left anterior insula (−36, 20, 4), and left middle temporal gyrus (BA 21; −47, −44, 4). The other region not shown here was left inferior parietal cortex (BA 40; −54, −22, 37). In B (right) are 3‐D views predominantly of peaks of amygdalar activation correlating positively with log rSCL (coordinates underneath each image). Top left and right: axial and coronal views, respectively. Bottom left and right: sagittal views of activation in left and right amygdala, respectively. Images are presented in identical formats as those in Figure 2.

Between‐Condition Differences in BOLD Signal Changes

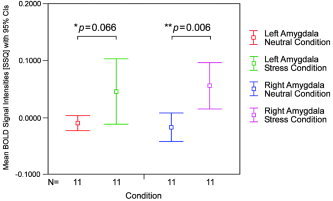

Differences in the fMRI signal were compared utilizing mean peak values in SSQ, the measure for BOLD signal against residual noise, in the left and right amygdalar voxel clusters between neutral and stress conditions, respectively (Fig. 5). The mean peak SSQ for the left amygdala in the neutral condition was −0.0088 ± 0.0059 and the mean peak SSQ for the left amygdala in the stress condition was 0.0466 ± 0.0256. The mean peak SSQ for the right amygdala in the neutral condition was −0.0162 ± 0.0112 and the mean peak SSQ for the right amygdala in the stress condition was 0.0562 ± 0.0181. The difference for SSQ in the left amygdala between neutral and stress conditions approached significance (95% CI, −0.0044–0.1151; paired Student's t[11] = 2.065, P = 0.066). The difference for SSQ in the right amygdala was significant (95% CI, −0.0924–0.0173; paired Student's t[11] = 3.481, P = 0.006). Similar results were obtained when using nonparametric Wilcoxon's signed‐rank test.

Figure 5.

Between‐condition differences in amygdalar blood oxygenation level‐dependent (BOLD) signal intensities. Mean values of sum‐of‐square quotient (SSQ), the measure of BOLD signal against residual noise, for bilateral amygdala clusters in the neutral and stress conditions. Error bars indicate upper and lower 95% confidence intervals. Between‐condition differences are close to or below significance levels in both hemispheres.

DISCUSSION

Although previous studies have implicated the amygdala and ventral striatum in mammalian attachment [Insel,1997; Loup et al.,1991], and have reported elevated autonomic responses in insecurely attached individuals [Spangler and Grossmann,1993; Spangler and Schieche,1998], the neurophysiological basis of human attachment remains relatively unexplored. In the current study, we used event‐related fMRI and online psychophysiological measurements to examine the neural basis of human attachment. The measure of attachment security employed was the reaction time difference in performance between two conditions on a semantic conceptual priming task of the neutral minus that for the stress prime condition. This measure has been validated with other measures of attachment security [Maier et al.,2004]. Previous findings allowed us to predict an amygdalar response during the stress but not the neutral condition in all individuals. Importantly, we predicted the involvement of amygdala and ventral striatum in the mediation of autonomic responses associated with attachment insecurity; specifically, we predicted positive correlations between the magnitudes of attachment insecurity, and autonomic, amygdalar, and ventral striatal responses during performance of the stress prime condition.

The findings of the current study supported the first of the above predictions: bilateral amygdalar responses were observed only during the stress prime condition, and not during the neutral prime condition. Our findings also supported our second prediction of the involvement of the amygdala and, in part, that of the ventral striatum in the mediation of autonomic responses associated with attachment insecurity. Specifically, our findings demonstrated that the magnitude of response within bilateral amygdalae and left ventral striatum (ventral putamen/nucleus accumbens) during the stress prime condition correlated positively with the measure of attachment insecurity, and the magnitude of response within bilateral amygdalae during this condition correlated positively with the magnitude of autonomic response. Magnitudes of attachment insecurity and autonomic response were also positively correlated during the stress prime condition.

Positive correlations were demonstrated between attachment insecurity and magnitudes of neural response in left ventrolateral prefrontal cortex, right dorsal anterior cingulate gyrus, left middle and superior temporal gyri, and left inferior parietal cortex. Positive correlations were also demonstrated between magnitudes of autonomic response and neural response within left ventrolateral prefrontal cortex, left middle temporal gyrus, left anterior insula, and left inferior parietal cortex. However, these regions were activated during performance of both stress and neutral prime conditions. The bilateral amygdalae were the only neural regions activated specifically during the stress prime condition whose magnitude of response correlated positively with measures of attachment insecurity and autonomic response. Together, these findings therefore suggest a role for the amygdala in the mediation of autonomic responses associated with attachment insecurity.

Susceptibility loss effects are possible in neuroimaging of the amygdaloid complex due to the neighboring sphenoid sinus and auditory canals; however, 1.5‐T gradient echo EPI is less prone to susceptibility artifacts than are higher magnetic fields. As amygdalar volume is usually 1.7 cm3, an anatomic in‐plane resolution of 1.5 mm in a 1282 matrix will provide optimal coverage of this structure. Voxel sizes such as those in the present study (98.4 μl) have been shown to reliably demonstrate amygdalar activity in response to emotive stimuli [e.g. Surguladze et al.,2003]. Furthermore, the positive finding of amygdalar activation in the present study speaks in favor of the reliability of signal detection in this study rather than against it. Moreover, it was possible to demonstrate significant differences in bilateral amygdalar signal intensities between both conditions, even when controlling for signal‐to‐noise ratio.

Our findings support those from studies in mammals implicating the role of the amygdala in attachment. In mammals, the neuropeptide oxytocin has been found to be crucially involved in both filial and between‐mate attachment [Carter,1998; Insel and Shapiro,1992]. In mice, the strongest expressions of oxytocin receptors have been reported in the amygdala, the hippocampus, and the caudate‐putamen [Tomizawa et al.,2003], and failure of oxytocin binding in the amygdala prevents the formation of kin recognition and memory. It is known that dopamine controls oxytocin receptor expression in the amygdala and that oxytocin infusion in the amygdala is related to both anxiety and sexuality [Bale et al.,2001]. Experimentally induced maternal separation in Octodon degus has been demonstrated to significantly reduce the pruning of dendritic spines in the lateral amygdalae and the hippocampus [Poeggel et al.,2003]. In addition, recent lesion studies in non‐human primates (Macaca mulatta) have revealed that point lesions in the amygdaloid complexes leading to shrinkage of neural tissue in these regions cause significant decreases in social interactions in adult monkeys [Amaral et al.,2003]. When applying the same insults to infant rhesus monkeys, amygdala‐lesioned but not hippocampus‐lesioned animals show fewer exploratory behaviors and increased bodily proximity to mothers during the infancy period, but do not display separation distress or protest vocalizations, and exhibit proximity avoidance in later development, all indicators of disorganized attachment in humans [Baumann et al.,2004]. These findings therefore suggest that in primates, the amygdalae not only modulate the amount of interaction, but also critically mediate behaviors known to be attachment specific in humans.

In humans, as in other mammals, oxytocin mediates reproductive and maternal care behaviors. Radiotracer studies on binding sites for oxytocin in the human brain have also revealed that the highest concentration of oxytocin receptors are within the amygdalae [Insel,1997; Loup et al.,1991] and ventral striatum [Loup et al.,1991]. Interestingly, neuroimaging data have revealed a relative decrease in amygdalar response to stimuli evoking maternal and romantic love [Bartels and Zeki,2004]. These findings are consistent with our above findings on the role of the amygdala in humans in the mediation of behaviors associated with attachment insecurity. However, when using a face‐familiarity paradigm to test parent‐to‐child attachment, activation of the right amygdala in the own‐ versus other‐child subtraction contrast and activation of the left amygdala in the familiar versus unfamiliar child subtraction contrast was found [Leibenluft et al.,2004].

Each test item within each condition necessarily evoked retrieval of autobiographic, and therefore emotionally salient, memories after semantic priming. The amygdala and hippocampus have been linked with a specific arousal‐evoking pathway during the processing of emotional memories [Kensinger and Corkin,2004]. In the current study, amygdalar responses were observed solely in the stress prime condition, making it unlikely that the amygdalar responses observed during this condition were the result of emotional memory recollection per se. The corpus of studies on amygdalar activation and skin conductance [e.g., Anders et al.,2004] shows that unilateral amygdala engagement and skin conductance responses are specific to faces (but not scenes) and follow fear or threat only. This is consistent with the notion that in our task, arousal associated with reminiscence of separation distress‐evoking autobiographic memory content is triggered and produces bilateral amygdalar activation.

Furthermore, conjunction analysis revealed that performance of both conditions was associated with activation in several regions, but not the amygdala, and predominantly within left precentral and postcentral gyri, bilateral visual regions, left inferior parietal lobule, middle temporal gyrus, left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, and right dorsal anterior cingulate gyrus. Other regions activated in both conditions, although not identified in the conjunction analysis, included other areas within bilateral prefrontal and visual cortices and right inferior parietal cortex. These regions have been implicated in sensorimotor and visuospatial processing, selective attention [Kiehl et al.,2000; Kristoff and Grabrieli,2000], and semantic processing [Dehaene et al.,1998; Henson,2001; Rossell et al.,2001; Vandenberghe et al.,2002], processes common to the performance of both conditions in the current study.

We predicted the involvement of the ventral striatum in the mediation of autonomic responses associated with attachment insecurity. Although we observed a positive correlation between left ventral striatal response and attachment insecurity during the stress prime condition, there was no positive correlation between this response and the magnitude of autonomic response during the stress prime condition. Furthermore, the left putamen responded to both stress and neutral prime conditions. These findings may therefore reflect the role of the putamen in the response to emotive or salient material, reported previously in other neuroimaging studies in humans [e.g., Pagnoni et al.,2002; Surguladze et al.,2003], but not in attachment in humans. Another region implicated in the response to emotive stimuli, the insula [e.g. Calder et al.,2001; Phillips et al.,1997; Surguladze et al.,2003], was also activated by both conditions.

As a caveat, the presented findings should be considered limited to this semantic conceptual priming task validated for attachment security. The relatively small sample size and the inability to control for AAI results in this fMRI study currently prevent a generalizability of the results. Ideally, neuroimaging studies using this paradigm should be conducted in larger developmental attachment cohort samples.

CONCLUSIONS

This study examines the neural basis of human attachment security, the human equivalent of vertebrate imprinting, using a novel but well‐validated experimental paradigm for the assessment of attachment security. In humans, the amygdala has been implicated repeatedly in the response to emotionally salient stimuli and contains high densities of receptors for oxytocin, a neuropeptide critical for mammalian attachment‐specific maternal, filial, and mating behaviors. Our findings highlight the important role of the amygdala in the mediation of autonomic responses associated with attachment insecurity in healthy adult humans.

REFERENCES

- Amaral DG, Capitanio JP, Lavenex P, Mason WA, Mauldin‐Jourdain ML, Mendoza SP (2003): The amygdala: is it an essential component of the neural network for social cognition? Neuropsychologia 41: 517–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anders S, Lotze M, Erb M, Grodd W, Birbaumer N (2004): Brain activity underlying emotional valence and arousal: a response‐related fMRI study. Hum Brain Mapp 23: 200–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bale TL, Davis AM, Auger AP, Dorsa DM, McCarthy MM (2001): CNS region‐specific oxytocin receptor expression: importance in regulation of anxiety and sex behavior. J Neurosci 21: 2546–2552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartels A, Zeki S (2004): The neural correlates of maternal and romantic love. Neuroimage 21: 1155–1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann MD, Lavenex P, Mason WA, Capitanio JP, Amaral DG (2004): The development of mother‐infant interactions after neonatal amygdala lesions in rhesus monkeys. J Neurosci 24: 711–721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brammer MJ, Bullmore ET, Simmons A, Williams SCR, Grasby PM, Howard RJ, Woodruff PWR, Rabe‐Hesketh S (1997): Generic brain activation mapping in functional magnetic resonance imaging: a nonparametric approach. Magn Reson Imaging 15: 763–770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breakspear M, Brammer MJ, Bullmore ET, Das P, Williams LM (2004): Spatiotemporal wavelet resampling for functional neuroimaging data. Hum Brain Mapp 23: 1–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breakspear M, Brammer MJ, Robinson PA (2003): Construction of multivariate surrogate sets from nonlinear data using the wavelet transform. Physica D 182: 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Bullmore ET, Brammer MJ, Rabe‐Hesketh S, Curtis VA, Morris RG, Williams SCR, Sharma T, McGuire PK (1999): Methods for diagnosis and treatment of stimulus‐correlated motion in generic brain activation studies using fMRI. Hum Brain Mapp 7: 38–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullmore ET, Long C, Suckling J, Fadili MJ, Calvert G, Zelaya F, Carpenter TA, Brammer MJ (2001): Color noise and computational inference in neurophysiological (fMRI) time series analysis: resampling methods in time and wavelet domains. Hum Brain Mapp 12: 61–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calder AJ, Lawrence AD, Young AW (2001): Neuropsychology of fear and loathing. Nat Rev Neurosci 2: 352–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter CS (1998): Neuroendocrine perspectives on social attachment and love. Psychoendocrinology 23: 779–818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehaene S, Naccache L, Le Clec HG, Koechlin E, Müller M, Dehaene‐Lambertz G, van de Moortele PF, Le Bihan D (1998): Imaging unconscious semantic priming. Nature 395: 597–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fadili MJ, Bullmore ET (2002): Wavelet‐generalized least squares: a new BLU estimator of linear regression models with 1/f errors. Neuroimage 15: 217–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson JN, Aldag JM, Insel TR, Young LJ (2001): Oxytocin in the medial amygdala is essential for social recognition in the mouse. J Neurosci 21: 8278–8285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henson RN (2001): Repetition effects for words and nonwords as indexed by event‐related fMRI: a preliminary study. Scand J Psychol 42: 179–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn G (1985): Memory, imprinting, and the brain: an inquiry into mechanisms. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press; 312 pp. [Google Scholar]

- Insel TR (1997): A neurobiological basis of social attachment. Am J Psychiatry 154: 726–735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Insel TR, Shapiro LE (1992): Oxytocin receptor distribution reflects social organization in monogamous and polygamous voles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 89: 5981–5985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Insel TR, Young LJ (2001): The neurobiology of attachment. Nat Rev Neurosci 2: 129–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kensinger EA, Corkin S (2004): Two routes for emotional memory: distinct neural processes for valence and arousal. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 3310–3315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiehl KA, Liddle PF, Hopfinger JB (2000): Error processing and the rostral anterior cingulate: an event‐related fMRI study. Psychophysiology 37: 216–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer GW (1992): A psychobiological theory of attachment. Behav Brain Sci 15: 493–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kristoff K, Grabrieli JD (2000): The frontopolar cortex and human cognition: evidence for a rostrocaudal hierarchical organization within the human prefrontal cortex. Psychobiology 28: 168–186. [Google Scholar]

- Leibenluft E, Gobbini MA, Harrison T, Haxby JV (2004): Mothers' neural activation in response to pictures of their children and other children. Biol Psychiatry 56: 225–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemche E, Klann‐Delius G, Koch R, Joraschky P (2004): Mentalizing language development in a longitudinal attachment sample: implications for alexithymia. Psychother Psychosom 73: 366–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loup F, Tribollet E, Dubois‐Dauphin M, Dreifuss JJ (1991): Localization of high‐affinity binding sites for oxytocin and vasopressin in the human brain. Brain Res 555: 220–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovic V, Gonzalez A, Fleming AS (2001): Maternally separated rats show deficits in maternal care in adulthood. Dev Psychobiol 39: 19–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maier MA, Bernier A, Pekrun R, Zimmermann P, Grossmann KE (2004): Attachment working models as unconscious structures: an experimental test. Int J Behav Dev 28: 180–189. [Google Scholar]

- McCabe BJ, Nicol AU (1999): The recognition memory of imprinting: biochemistry and electrophysiology. Behav Brain Res 98: 253–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JS, Friston KJ, Büchel C, Frith CD, Young AW, Calder AJ, Dolan RJ (1998): A neuromodulatory role for the human amygdala in processing emotional facial expressions. Brain 121: 47–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldfield RC (1971): The assessment and analysis of handedness: the Edinburgh Inventory. Neuropsychologia 7: 97–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagnoni G, Zink CF, Montague PR, Berns S (2002): Activity in human ventral striatum locked to errors of reward prediction. Nat Neurosci 5: 97–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips ML, Young AW, Senior C, Brammer MJ, Andrew CM, Calder AJ, Bullmore ET, Perret DI, Rowland D, Williams SCR, Gray JA, David AS (1997): A specific neural substrate for perceiving facial expressions of disgust. Nature 389: 495–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poeggel G, Helmeke C, Abraham A, Schwabe T, Friedrich P, Braun K (2003): Juvenile emotional experience alters synaptic composition in the rodent cortex, hippocampus, and lateral amygdala. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 16137–16142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossell SL, Bullmore ET, Williams SCR, David AS (2001): Brain activation during automatic and controlled processing of semantic relations: a priming experiment using lexical‐decision. Neuropsychologia 39: 1167–1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spangler G, Grossmann KE (1993): Biobehavioral organization in securely and insecurely attached infants. Child Dev 62: 1439–1450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spangler G, Schieche M (1998): Emotional and adrenocortical responses of infants to the Strange Situation: the differential function of emotional expression. Int J Behav Dev 22: 681–706. [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger CD (1983): Manual for the State‐Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI). Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 76 pp. [Google Scholar]

- Surguladze SA, Brammer MJ, Young AW, Andrew C, Travis MJ, Williams SCR, Phillips ML (2003): A differential modulation of visual cortical activation by displays of danger, reward and distress. Neuroimage 19: 1317–1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talairach J, Tournoux P (1988): Co‐planar stereotaxic atlas of the human brain. Stuttgart, Germany: Thieme Medical Publishers; 122 p. [Google Scholar]

- Tomizawa K, Iga N, Lu YF, Moriwaki A, Matsushita M, Li S‐T, Miyamoto O, Itano T, Matsui H (2003): Oxytocin improves long‐lasting spatial memory during motherhood through MAP kinase cascade. Nat Neurosci 6: 384–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandenberghe R, Nobre AC, Price CJ (2002): The response of left temporal cortex to sentences. J Cogn Neurosci 14: 550–560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whalen PJ, Shin LM, McInerney SC, Fischer H, Wright CI, Rauch SL (2001): A functional MRI study of human amygdala responses to facial expressions of fear versus anger. Emotion 1: 70–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Medical Association (1999): Code of ethics: declaration of Helsinki. British Medical Journal 302: 1194. [Google Scholar]