Abstract

Ventral anterior cingulate cortex (vACC) is a highly interconnected brain region considered to reflect the sometimes competing demands of cognition and emotion. A reciprocal relationship between vACC and dorsal ACC (dACC) may play a role in maintaining this balance between cognitive and emotional processing. Using functional MRI in association with a cognitively‐demanding visuospatial task (mental rotation), we found that only women demonstrated vACC suppression and inverse functional connectivity with dACC. Sex differences in vACC functioning—previously described under conditions of negative emotion—are extended here to cognition. Consideration of participant sex is essential to understanding the role of vACC in cognitive and emotional processing. Hum Brain Mapp, 2007. © 2007 Wiley‐Liss, Inc.

Keywords: fMRI, functional neuroimaging, functional connectivity, sex differences, gender, ventromedial prefrontal cortex, subgenual, Brodmann area 25, mental rotation, visuospatial

INTRODUCTION

The ventral or subgenual portion of anterior cingulate cortex (vACC), a part of ventromedial prefrontal cortex, is involved in integrating and responding to motivationally‐relevant internal and external information [Bush et al., 2000; Devinsky et al., 1995]. In contrast to the dorsal portion of ACC (dACC), which is active during effortful, cognitive tasks and has been shown to mediate such attention‐requiring processes as response selection and error monitoring [Botvinick et al., 2004], activity in vACC is considered to be suppressed during cognition [Bush et al., 2000; Drevets and Raichle, 1998; Simpson et al., 2001b]. Increased vACC activity has instead been associated with conditions of negative emotion [Bush et al., 2000; Drevets and Raichle, 1998; Phan et al., 2002]. Abnormalities in vACC structure and function have been linked to disorders of emotion including major depression [Drevets et al., 1997]. Importantly, this understanding of vACC as reflecting a balance between cognition and emotion is based primarily on functional imaging studies performed on mixed‐sex participant groups, without specific attention to possible sex differences.

Participant sex is now known to be a crucial factor that contributes significantly to results of functional neuroimaging studies [Cahill, 2005]. Using fMRI, we recently showed that vACC activity was significantly greater in women than in men during an experimental condition of instructed fear, when uncomfortable electrodermal stimulation was expected [Butler et al., 2005]. This finding is in accord with multiple reports of greater vACC activity in women as compared to men under other conditions of negative emotion [Derbyshire et al., 2002; Wrase et al., 2003] including a metaanalysis of 65 neuroimaging studies [Wager et al., 2003]. The apparent association of increased vACC activity with negative emotion [Bush et al., 2000; Drevets and Raichle, 1998; Phan et al., 2002], rather than representing a general phenomenon, may therefore be driven primarily by female participants. Is the association of decreased ventral ACC activity with cognition [Bush et al., 2000; Drevets and Raichle, 1998; Simpson et al., 2001b] similarly sex‐specific? To answer this question, we performed a focused analysis of an existing fMRI dataset [Butler et al., 2006] to examine sex differences in vACC activity and vACC/dACC functional connectivity during performance of mental rotation, a visuospatial task commonly used to study sex differences [Voyer et al., 1995].

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

Thirty two participants were scanned as part of this study, which was approved by the Weill‐Cornell Institutional Review Board. All participants were strongly right‐handed, free from medical, neurological, and psychiatric disease, and taking no medications. Acceptable data were obtained from 13 women (mean age = 28.6, std = 7.5) and 12 men (mean age = 30.1, std = 5.9). Reasons for excluding participants from final analyses were: MRI ghosting artifact greater than 5% (one woman, two men); head movement greater than 1/3 of a voxel based on examination of realignment parameters (two women, one man); and failure to perform the task in the scanner (one man).

Experimental Task

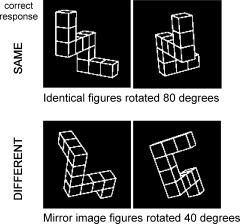

Redrawn versions [Peters et al., 1995] of Shepard and Metzler [1971] original cube figure were presented in pairs (Fig. 1). Figures were white on a black background. Stimuli pairs were either the same, but rotated with respect to one another (“same” trials) or they were mirror images of each other (“different” trials). Stimuli were rotated with respect to one another around their vertical axis. Presentation of stimuli in the scanner was controlled by the integrated functional imaging system (IFIS; MRI Devices, Gainesville, FL) by means of Eprime software (Psychology Software Tools, Pittsburgh, PA).

Figure 1.

Examples of mental rotation stimuli. Participants were instructed to mentally rotate figures into alignment in order to decide if they were the same or different.

The mental rotation activation condition consisted of pairs of figures which were either identical (same) or mirror images (different) rotated by 40°, 80°, 120°, or 160° with respect to one another. Participants were instructed to mentally rotate figures into alignment in order to decide if they were the same or different. Accuracy and reaction time (RT) were recorded.

An active control condition consisted of pairs of figures which were either identical or mirror images which were not rotated with respect to one another. Participants were instructed that in this condition, there was no need to try to rotate figures into alignment. This condition controlled for visual properties of the stimuli, the saccades and evaluation process required to reach a same or different decision, and the motor act of pressing a button.

In the context of a block design paradigm, stimuli pairs at each angle of rotation were grouped into blocks of five trials each. Each trial lasted 7.5 s, resulting in blocks lasting 37.5 s. Each trial consisted of an orienting signal (a fixation cross in the center of the screen) for 500 ms, followed by a pair of stimuli presented for 7 s. Participants responded to stimuli by pressing a button with their right index finger for a “same” response or right middle finger for a “different” response. There were a total of 16 mental rotation blocks and 12 control (unrotated) blocks which were interspersed with a resting baseline condition (visual fixation) of 24.5 s. Additional details of this paradigm are available elsewhere [Butler et al., 2006; Voyer et al., 2006].

Image Acquisition

Image data were acquired on one of two identical GE Signa 3 Tesla MRI scanner (max gradient strength 40 mT/m, max gradient slew rate 150 T/m/s; General Electric Company, Waukesha, WI) using blood oxygen level dependent (BOLD) fMRI. Approximately equal numbers of men and women were scanned on each scanner. After shimming to maximize homogeneity, a series of fMRI scans was collected using gradient echo‐planar imaging (EPI) (TR = 2000; TE = 30; flip angle = 70°; FoV = 240 mm; 27 slices; 5‐mm thickness with 1‐mm inter‐slice space; matrix = 64 × 64). Images were acquired over the whole brain parallel to the AC‐PC plane. The first six volumes of each epoch were discarded. A reference T1 weighted anatomical image with the same slice placement and thickness and a matrix of 256 × 256 was acquired immediately preceding the EPI acquisition. A high‐resolution T1 weighted anatomical image was acquired using a spoiled gradient recalled echo sequence with a resolution of 0.9375 × 0.9375 × 1.5 mm3.

Image Processing and Analysis

Image processing performed within a customized statistical parametric mapping (SPM) 99 software package (http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm) included manual AC‐PC reorientation of all anatomical and EPI images; realignment of functional EPI images based on intracranial voxels to correct for slight head movement between scans; coregistration of functional EPI images to corresponding high‐resolution anatomical image for each participant; stereotactic normalization to the standardized coordinate space of Talairach and Tournoux (Montreal Neurological Institute, MNI average of 152 T1 brain scans) based on the high‐ resolution anatomical image; and spatial smoothing of the normalized EPI images with an isotropic Gaussian kernel (FWHM = 7.5 mm).

A voxel‐by‐voxel univariate multiple linear regression model at the participant level determined the extent to which each voxel's activity correlated with the principal regressor, which consisted of stimulus onset times and duration convolved with a prototypical hemodynamic response function. The temporal global fluctuation estimated as the mean intensity within brain region of each volume was removed through proportional scaling. The first order temporal derivative of the principal regressor, temporal global fluctuation, realignment parameters, and scanning periods were incorporated as covariates of no interest. This first level analysis resulted in a set of contrast images of condition‐specific effects for each participant, which were entered into second‐level random‐effects analyses to best account for interparticipant variability and allow population‐based inferences to be drawn [McGonigle et al., 2000].

A group‐level random‐effects analysis examined sex differences during mental rotation using contrast images corresponding to the active mental rotation condition (all angles combined). Participant age and scanner were entered as covariates of no interest in an ANCOVA setting. Results were assessed at an initial threshold of P < 0.01 uncorrected, and considered significant at a threshold of P < 0.05 corrected for multiple comparisons within a vACC region of interest (ROI) consisting of a 1,500 mm3 sphere centered on vACC coordinates of x = 0, y = 24, z = −6 derived from Drevets et al. [1997]. This sphere included the region of vACC sex difference identified in our prior study using an instructed fear paradigm [Butler et al., 2005].

Another group‐level random‐effects analysis assessed vACC functional connectivity with dACC in men, in women, and in women as compared to men. For this analysis, a multiple regression model was employed within SPM using the block‐specific activation level in vACC as the regressor of interest. Each participant's contrast image from each mental rotation block was the dependent variable, and the participant factor, participant age, and scanner used were covariates of no interest. Results were assessed at an initial threshold of P < 0.01 uncorrected, and considered significant at threshold of P < 0.05 corrected for multiple comparisons within a standard bilateral ACC ROI [Tzourio‐Mazoyer et al., 2002].

RESULTS

Behavioral Results

Men and women took equal amounts of time to perform mental rotation [mean RT for men = 4.11 s (std = 0.68); for women = 3.96 s (std = 0.65); F(1,23) = 0.48, P = 0.5]. Men performed mental rotation nonsignificantly more accurately than women [accuracy for men = 83% (std = 17); for women = 75% (std = 16); F(1,23) = 2.04, P = 0.17]. This trend for better male performance was not apparent when omitted trials (3.2% of trials for women, 4.8% of trials for men) were counted as incorrect and included in the analysis [F(1,23) = 0.29, P = 0.59].

fMRI Results

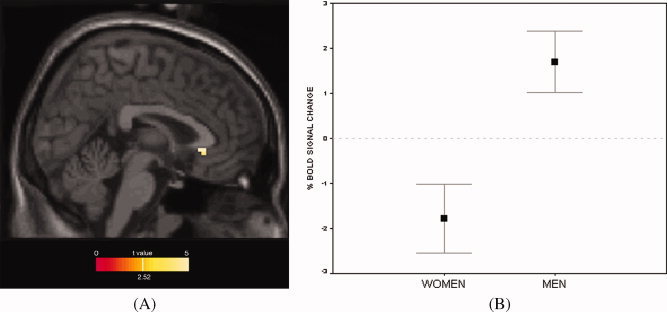

During mental rotation, there was significantly greater activity in men than in women in bilateral vACC (x = 3, y = 24, z = −3; Z‐score = 2.83; p unc = 0.002/p corr = 0.049; cluster volume = 270 mm3) as shown in Figure 2A. As shown in Figure 2B, this sex difference was driven by suppressed vACC activity in women (as compared to a resting baseline), and increased vACC activity in men. A stepwise regression analysis with age, scanner used, and overall mental rotation performance accuracy as covariates of no interest revealed that none of these confounding factors explained the difference in vACC activation [only 1.7% of the variance was accounted for by age (p = 0.46), 0.4% by performance (p = 0.75), and less than 0.01% by scanner (p = 0.98)]. Sex accounted for 33.1% of the unique variance (p = 0.003).

Figure 2.

(A) Greater vACC activity in men as compared to women during mental rotation. Results within a vACC ROI mask are overlaid onto a canonical T1 sagittal section (x = 3) and displayed at a voxelwise threshold of p < 0.01 (for illustration purposes; peak vACC voxel survives correction for multiple comparisons). (B) Plot showing sex‐specific activity of peak vACC voxel shown in panel A (x = 3, y = 24, z = −3). Note vACC suppression in women during mental rotation; vACC activation in men. Zero corresponds to a resting baseline. Shown with standard error bars.

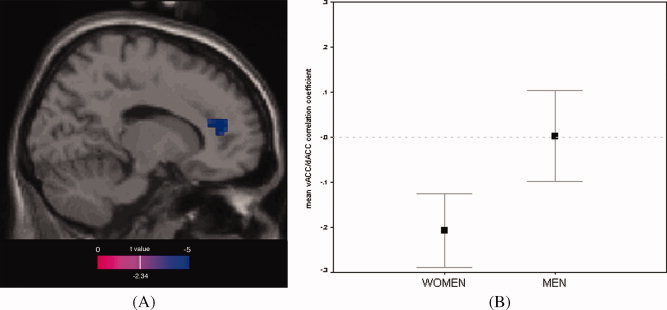

Using the voxel of maximal vACC sex difference as a “seed” to assess functional connectivity within the ACC ROI during performance of mental rotation, activity in dACC (Brodmann area 32; x = 9, y = 39, z = 27; Z‐score = −3.35; p unc < 0.0001/p corr = 0.059; cluster volume = 378 mm3) was found in women to correlate inversely with activity in vACC. In men, there were no regions anywhere in the ACC in which activity correlated inversely with vACC activity (p unc > 0.2). Between‐sex comparison confirmed a significant sex difference in functional connectivity between vACC and dACC, with only women showing inverse connectivity (x = 15, y = 39, z = 15; Z‐score = −4.07; p unc < 0.0001/p corr = 0.006; cluster volume = 2,052 mm3), as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

(A) Inverse functional connectivity between dACC (Brodmann area 32) and vACC in women as compared to men. Results within a standard ACC ROI mask are overlaid onto a canonical T1 sagittal section (x = 15) and displayed at a voxelwise threshold of p < 0.01 (for illustration purposes; peak dACC voxel survives correction for multiple comparisons). (B) Plot showing average correlation coefficient between peak dACC voxel shown in panel A (x = 15, y = 39, z = 15) and vACC (x = 3, y = 24, z = −3) for men and women during mental rotation. Only women demonstrate a negative correlation, corresponding to inverse vACC/dACC functional connectivity. Shown with standard error bars.

Although this study focuses on the ACC ROI, whole‐brain fMRI results for men vs. women during mental rotation can be found in [Butler et al., 2006]. Whole‐brain vACC functional connectivity results are presented in Table I. Of note, there was highly significant positive functional connectivity between vACC and left amygdala/extended amygdala in women (x = −15, y = 0, z = −9; Z‐score = 6.61; p corr < 0.0001).

Table I.

Brain regions in which activity was positively or negatively correlated with activity in vACC (x = 3, y = 24, z = −3) during mental rotation

| Cluster volume (cm3) | Peak coordinate in MNI Space | Corrected p‐value | Z‐score | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x | y | z | ||||

| Women (positive correlation) | ||||||

| SEED VOXEL*: bilateral vACC (subgenual) | 37.4 | 3 | 24 | −3 | <0.0001 | >8 |

| Pre‐genual ACC | (subcluster) | 0 | 42 | 3 | >8 | |

| −9 | 45 | −3 | >8 | |||

| L anterior insula/inferior frontal gyrus | (subcluster) | −30 | 15 | −12 | >8 | |

| L amygdala/extended amygdala (discussed in text) | (subcluster) | −15 | 0 | −9 | 6.61 | |

| −18 | −6 | −12 | 5.52 | |||

| R extended amygdale | (subcluster) | 27 | 9 | −12 | 5.34 | |

| L temporal (BA 41)/posterior insula (BA 13) | 0.2 | −33 | −27 | 12 | 0.001 | 5.47 |

| L posterior parahippocampus (BA 30) | 0.2 | −15 | −33 | −6 | 0.004 | 5.14 |

| Women (inverse correlation) | ||||||

| R lateral orbitofrontal cortex (BA 47) | 0.9 | 45 | 33 | −12 | <0.0001 | −6.74 |

| L superior temporal gyrus | 0.3 | −30 | 9 | −24 | <0.0001 | −6.47 |

| L temporal (subcortical) | 0.4 | −39 | −18 | −9 | <0.0001 | −5.83 |

| Bilateral middle/superior frontal gyri | 1.6 | 36 | 51 | 21 | <0.0001 | −6.29 |

| 0.8 | −24 | 63 | 18 | <0.0001 | −5.71 | |

| Dorsal ACC/medial frontal gyri (discussed in text) | 0.4 | 0 | 33 | 36 | 0.007 | −5.00 |

| Men (positive correlation) | ||||||

| SEED VOXEL*: bilateral vACC (subgenual) | 36.1 | 3 | 24 | −3 | <0.0001 | >8 |

| L frontal | (subcluster) | −18 | 30 | 0 | >8 | |

| L frontal extending to head of caudate | (subcluster) | −12 | 24 | 12 | >8 | |

| R frontal extending to head of caudate | (subcluster) | 15 | 27 | 12 | 6.64 | |

| Pre‐genual ACC | (subcluster) | 3 | 48 | 0 | 5.85 | |

| Bilateral cerebellum | 0.6 | −24 | −42 | −42 | <0.0001 | 6.74 |

| 0.3 | 21 | −45 | −42 | 0.006 | 5.04 | |

| Bilateral paracentral lobule/precuneus (BA 5/7) | 1.0 | −3 | −45 | 78 | <0.0001 | 6.34 |

| 3.3 | 3 | −39 | 57 | <0.0001 | 5.99 | |

| Midline brainstem | 0.2 | 0 | −48 | −54 | 0.001 | 5.42 |

| Men (inverse correlation) | ||||||

| Bilateral lateral orbitofrontal | 1.8 | −48 | 27 | 15 | <0.0001 | −7.09 |

| 0.2 | 57 | 24 | −6 | 0.004 | −5.10 | |

| R insula | 3.1 | 39 | −6 | −6 | <0.0001 | −6.66 |

| 0.3 | 36 | −18 | 6 | 0.002 | −5.22 | |

| L insula | 1.0 | −36 | −6 | −3 | <0.0001 | −6.02 |

| R anterior superior temporal gyrus | 0.5 | 30 | 9 | −30 | <0.0001 | −5.54 |

| Bilateral occipital (BA 18) | 1.1 | 6 | −87 | 18 | 0.002 | −5.31 |

| L pons | 0.2 | −12 | −24 | −24 | 0.006 | −5.03 |

Listed clusters survived correction for multiple comparisons across the entire brain (search volume = 1612 cm3) with extent threshold >6 voxels (0.16 cm3).

There was expected, extensive, positive “self‐correlation” of the vACC seed voxel with contiguous voxels (expected based on local neuronal connectivity and spatial smoothing used in image processing). Highly‐significant local submaxima within the self‐correlation cluster are listed.

DISCUSSION

During performance of an effortful, visuospatial cognitive task, activity and functional connectivity of vACC differed significantly between healthy men and women. Only women demonstrated the typically‐described pattern of activity based on the conception of vACC as a region important for emotional processing that is suppressed during cognition [Bush et al., 2000; Drevets and Raichle, 1998; Simpson et al., 2001b]. Sex‐specific patterns of vACC activity were not due to slight, nonsignificant differences in behavioral performance between men and women, or to other confounding factors. The theory of reciprocal activity of dACC and vACC [Bush et al., 2000; Drevets and Raichle, 1998]—a theory not previously (to our knowledge) tested via functional connectivity analysis—was supported in women but not in men.

These results reinforce the increasingly acknowledged fact that sex matters in functional imaging studies [Cahill, 2005], and highlight vACC as a key brain region important for understanding why this is the case. When current results are considered along with prior findings of sex‐specific vACC activity during emotional processing [Butler et al., 2005; Derbyshire et al., 2002; Wager et al., 2003; Wrase et al., 2003], a complex pattern of vACC functioning critically dependant upon both the nature of the task and the sex of the participant becomes apparent. Results from this study provide a framework for further investigation of sex‐ and task‐specific vACC functioning. In particular, this first demonstration of sex‐specific vACC activity and connectivity during cognitive processing could be examined using other types of cognitive tasks (including tasks not expected to produce behavioral sex differences), to determine whether current results are specific to visuospatial tasks such as the mental rotation task used in this study, or reflect fundamental sex differences in vACC‐related neural circuitry involved generally in effortful cognitive processing.

Current results demonstrate that vACC suppression during effortful cognitive processing—previously considered a general phenomenon [Bush et al., 2000; Drevets and Raichle, 1998; Simpson et al., 2001b]—may actually be present only in women. This is analogous to evidence that the vACC activation associated with negative emotion in multiple prior studies [Bush et al., 2000; Drevets and Raichle, 1998; Phan et al., 2002] may actually be present only in women [Butler et al., 2005], or to a significantly greater extent in women as compared to men [Derbyshire et al., 2002; Wager et al., 2003; Wrase et al., 2003]. Taken together, these findings suggest that models of vACC function based on results from mixed‐sex subject groups may correspond more closely to the female pattern of activity. Since it seems unlikely that female subjects are numerically overrepresented in functional imaging studies in general, these results cannot be easily explained, and will require further investigation. They may relate in some way to sex differences in difficult‐to‐measure factors such as task engagement or intensity of feeling, or to hormone‐related differences in hemodynamic response, since estrogen has been associated with a stronger BOLD signal [Dietrich et al., 2001] (though this effect would not be expected to be regional‐specific to the ventral ACC.)

In addition to emphasizing the general importance of attention to sex differences in functional neuroimaging, and raising an interesting question about why results from mixed‐sex functional neuroimaging studies appear to reflect a female pattern of vACC activity, current findings raise the key question of what might sex‐specific vACC activity and functional connectivity mean? While a satisfactory answer to this question will require much additional work, a plausible explanation for present results is that vACC suppression relates to cognitive effort, and that women devoted more cognitive effort to the mental rotation task, resulting in greater vACC suppression during task performance. Decades of behavioral research documenting better mental rotation performance by men [Voyer et al., 1995], provide some support for the idea that mental rotation may be more effortful for women than for men. Also in accord with this explanation are our recent findings (based on the same dataset) that despite similar bilateral frontal, parietal, occipitotemporal, and occipital activation in both men and women during performance of mental rotation [Butler et al., 2006], women show greater activation of dorsal medial prefrontal cortex and other high‐order cortical regions consistent with a “top‐down” approach, while men appear to utilize a more automatic, “bottom‐up” neural strategy involving subcortical structures and a visual/vestibular network [Butler et al., 2006].

However, several limitations of the above explanation must be noted: Broadly similar behavioral results in men and women, including increasing RT with increasing angle of rotation for men and women in general [Shepard and Metzler, 1971; Voyer et al., 2006; Voyer et al., 1995] and for the participants scanned for this study [Butler et al., 2006], suggest that mental rotation is a difficult, attention‐requiring task for both men and women. In addition, the fact that this study did not include rigorous measures of subjective cognitive effort renders this explanation speculative. To determine whether sex differences in cognitive effort represent a full or partial explanation for observed sex differences in vACC activity, future studies will need to incorporate careful attention to measures of perceived task difficulty and/or effort exerted.

It should be noted that sex differences in vACC activity during mental rotation were due not only to greater vACC suppression in women, but to increased vACC activity in men (as compared to a resting baseline, as shown in Fig. 1B). This unexpected male pattern of vACC activity is opposite to the traditional model, which posits that vACC should be suppressed during cognitive processing and active during emotional processing [Bush et al., 2000; Drevets and Raichle, 1998]. Given that subjective anxiety has been shown to modulate ventral ACC activity [Simpson et al., 2001a], it is conceivable that greater task‐related anxiety in men could account for their elevated vACC activity. However, men are generally considered to be less anxious than women during cognitive task performance [Payne et al., 1983], making this explanation less likely. It is also possible that mens' greater reliance upon an egocentric neural processing strategy (involving a visual‐vestibular brain network also active during actual or imagined self movement, discussed in detail in Butler et al. [2006]) could perhaps be reflected in greater ventral ACC activity, as this and other midline brain region have been implicated in processing of self‐relevant information [Northoff, 2005]. Additional studies will be needed to replicate and further investigate this result.

The finding in women (but not men) of significant positive functional connectivity between vACC and left amygdala matches a recent resting state positron emission tomography study [Kilpatrick et al., 2006]. Womens' greater vACC coupling with left amygdala may therefore be state‐independent, possibly reflecting structural brain differences. The amygdala's role in emotional processing in animals and humans is well established [LeDoux, 2000]. Additional studies examining sex‐specific vACC/amygdala functional connectivity under other experimental conditions, and using structural neuroimaging techniques such as diffusion tensor imaging, could provide additional information about the neural basis of sex differences in the balance between emotion and cognition.

CONCLUSION

In sum, results indicate that vACC functions differently in men and women during mental rotation. Sex‐specific vACC functioning may relate to sex differences in cognitive effort exerted during task performance, though additional work would be needed to directly test this idea. Taken together with prior evidence of sex differences in this region under conditions of negative emotion, present findings identify vACC as a key brain region especially important for understanding sex differences in cognitive and emotional processing, and add to mounting evidence that subject sex must be considered when designing and interpreting functional imaging studies. Recent exploration of vACC (Brodmann area 25) neurostimulation as a treatment for major depression [Mayberg et al., 2005]—a disorder significantly more common in women than in men [Weissman and Klerman, 1977]—highlights the importance of understanding this region's sex‐specific role in regulating emotion and cognition.

REFERENCES

- Botvinick MM,Cohen JD,Carter CS ( 2004): Conflict monitoring and anterior cingulate cortex: An update. Trends Cogn Sci 8: 539–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush G,Luu P,Posner MI ( 2000): Cognitive and emotional influences in anterior cingulate cortex. Trends Cogn Sci 4: 215–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler T,Pan H,Epstein J,Protopopescu X,Tuescher O,Goldstein M,Cloitre M,Yang Y,Phelps E,Gorman J,Ledoux J,Stern E,Silbersweig D ( 2005): Fear‐related activity in subgenual anterior cingulate differs between men and women. Neuroreport 16: 1233–1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler T,Imperato‐McGinley J,Pan H,Voyer D,Cordero J,Xhu Y,Stern E,Silbersweig D ( 2006): Sex differences in mental rotation: Top down versus bottom up processing. Neuroimage 32: 445–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahill L ( 2005): His brain, her brain. Sci Am 292: 40–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derbyshire SW,Nichols TE,Firestone L,Townsend DW,Jones AK ( 2002): Gender differences in patterns of cerebral activation during equal experience of painful laser stimulation. J Pain 3: 401–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devinsky O,Morrell MJ,Vogt BA ( 1995): Contributions of anterior cingulate cortex to behaviour. Brain 118 (Part 1): 279–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich T,Krings T,Neulen J,Willmes K,Erberich S,Thron A,Sturm W ( 2001): Effects of blood estrogen level on cortical activation patterns during cognitive activation as measured by functional MRI. Neuroimage 13: 425–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drevets WC,Raichle ME ( 1998): Reciprocal suppression of regional cerebral blood flow during emotional versus higher cognitive processes: Implications for interactions between emotion and cognition. Cogn Emotion 12: 353–385. [Google Scholar]

- Drevets WC,Price JL,Simpson JR Jr,Todd RD,Reich T,Vannier M,Raichle ME ( 1997): Subgenual prefrontal cortex abnormalities in mood disorders. Nature 386: 824–827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick LA,Zald DH,Pardo JV,Cahill LF ( 2006): Sex‐related differences in amygdala functional connectivity during resting conditions. Neuroimage 30: 452–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeDoux JE ( 2000): Emotion circuits in the brain. Annu Rev Neurosci 23: 155–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayberg HS,Lozano AM,Voon V,McNeely HE,Seminowicz D,Hamani C,Schwalb JM,Kennedy SH ( 2005): Deep brain stimulation for treatment‐resistant depression. Neuron 45: 651–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGonigle DJ,Howseman AM,Athwal BS,Friston KJ,Frackowiak RS,Holmes AP ( 2000): Variability in fMRI: An examination of intersession differences. Neuroimage 11 (6 Part 1): 708–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Northoff G. ( 2005): Emotional‐cognitive integration, the self, and cortical midline structures. Behav Brain Sci 28: 211. [Google Scholar]

- Payne BD,Smith JE,Payne DA ( 1983): Grade, sex, and race differences in test anxiety. Psychol Rep 53: 291–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters M,Laeng B,Latham K,Jackson M,Zaiyouna R,Richardson C ( 1995): A redrawn Vandenberg and Kuse mental rotations test: Different versions and factors that affect performance. Brain Cogn 28: 39–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phan KL,Wager T,Taylor SF,Liberzon I ( 2002): Functional neuroanatomy of emotion: A meta‐analysis of emotion activation studies in PET and fMRI. Neuroimage 16: 331–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepard RN,Metzler J ( 1971): Mental rotation of three‐dimensional objects. Science 171: 701–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson JR Jr,Drevets WC,Snyder AZ,Gusnard DA,Raichle ME ( 2001a): Emotion‐induced changes in human medial prefrontal cortex: II. During anticipatory anxiety. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 688–693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson JR Jr,Snyder AZ,Gusnard DA,Raichle ME ( 2001b): Emotion‐induced changes in human medial prefrontal cortex: I. During cognitive task performance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 683–687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzourio‐Mazoyer N,Landeau B,Papathanassiou D,Crivello F,Etard O,Delcroix N,Mazoyer B,Joliot M ( 2002): Automated anatomical labeling of activations in SPM using a macroscopic anatomical parcellation of the MNI MRI single‐subject brain. Neuroimage 15: 273–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voyer D,Voyer S,Bryden MP ( 1995): Magnitude of sex differences in spatial abilities: A meta‐analysis and consideration of critical variables. Psychol Bull 117: 250–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voyer D,Butler T,Cordero J,Brake B,Silbersweig D,Stern E,Imperato‐McGinley J ( 2006): The Relation between computerized and paper‐and‐pencil mental rotation tasks: A validation study. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 28: 928–939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wager TD,Phan KL,Liberzon I,Taylor SF ( 2003): Valence, gender, and lateralization of functional brain anatomy in emotion: A meta‐analysis of findings from neuroimaging. Neuroimage 19: 513–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman MM,Klerman GL ( 1977): Sex differences and the epidemiology of depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 34: 98–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wrase J,Klein S,Gruesser SM,Hermann D,Flor H,Mann K,Braus DF,Heinz A ( 2003): Gender differences in the processing of standardized emotional visual stimuli in humans: A functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Neurosci Lett 348: 41–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]