Abstract

The Gram-negative bacterium Francisella tularensis secretes the siderophore rhizoferrin to scavenge necessary iron from the environment. Rhizoferrin, also produced by a variety of fungi and bacteria, comprises two citrate molecules linked by amide bonds to a central putrescine (diaminobutane) moiety. Genetic analysis has determined that rhizoferrin production in F. tularensis requires two enzymes: FslA, a siderophore synthetase of the non-ribosomal peptide synthetase-independent siderophore synthetase (NIS) family and a pyridoxal-phosphate dependent decarboxylase, FslC. To discern the steps in the biosynthetic pathway, we tested cultures of F. tularensis strain LVS and its ΔfslA and ΔfslC mutants for the ability to incorporate potential precursors into rhizoferrin. Unlike putrescine supplementation, supplementation with ornithine greatly enhanced siderophore production by LVS. Radioactivity from [L-U-14C] ornithine, but not from [1-14C] ornithine, was efficiently incorporated into rhizoferrin by LVS. Although neither the ΔfslA nor the ΔfslC mutant produced rhizoferrin, a putative siderophore intermediate labeled by both [U-14C] ornithine and [1-14C] ornithine was secreted by the ΔfslC mutant. Rhizoferrin was identified by liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry in LVS culture supernatants, while citryl-ornithine was detected as the siderophore intermediate in the culture supernatant of the ΔfslC mutant. Our findings support a three-step pathway for rhizoferrin production in Francisella; unlike the fungus Rhizopus delemar, where putrescine functions as a primary precursor for rhizoferrin, biosynthesis in Francisella preferentially starts with ornithine as the substrate for FslA-mediated condensation with citrate. Decarboxylation of this citryl ornithine intermediate by FslC is necessary for a second condensation reaction with citrate to produce rhizoferrin.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Francisella tularensis, the etiological agent of the disease tularemia, is a Gram-negative bacterium that is adapted to survive and replicate within the cytoplasm in a variety of host tissues1. Iron is an essential element for F. tularensis but is largely sequestered in the host environment, requiring the pathogen to express special mechanisms to acquire this nutrient. Like many bacteria, F. tularensis secretes a siderophore to capture ferric iron in the iron-limiting environment and then takes up the complex using a specialized cell surface receptor2–4.

The siderophore biosynthetic and transport functions in Francisella are encoded by genes of the fsl operon2,3. The Francisella siderophore, rhizoferrin, is a polycarboxylate with a relatively simple structure comprising two citrate moieties linked to a putrescine backbone through amide bonds2,5. First identified as a fungal siderophore of a Rhizopus microsporus isolate, rhizoferrin is also produced by a disparate group of microorganisms comprising fungi as well as bacteria5–9. The chiral carbon atoms of the fungal rhizoferrin adopt an R,R configuration10 while the bacterium Ralstonia pickettii produces S,S rhizoferrin11, suggesting that the biosynthetic pathways for these enantiomers may involve enzymes with different specificities. Rhizoferrin biosynthesis has only recently begun to be addressed with a report on a siderophore synthetase from Rhizopus delemar9. Siderophores are synthesized either by pathways involving non-ribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPS) or the more recently characterized NRPS-independent synthetases (NIS)12,13. NIS synthetases may be phylogenetically classified into 4 subfamilies possessing distinct signature carboxylic acid and amine or alcohol substrate specificities. The Type A’ NIS enzymes catalyze condensation of a prochiral carboxylate group of citric acid with an amine. The siderophore synthetase from R. delemar, Rfs, is a Type A’ enzyme that iteratively catalyzes condensation of two citrate moieties with the amine groups of putrescine to form rhizoferrin9, supporting the idea that fungal rhizoferrin biosynthesis requires only this one enzyme.

In F. tularensis, siderophore production requires enzymatic activities encoded by two genes of the fsl operon, fslA and fslC; deletion of either of these genes renders the bacteria siderophore-deficient 2,3,14. The sequence of FslA identifies it as a NIS siderophore synthetase of the Type A’ subfamily while FslC is a pyridoxal phosphate-dependent decarboxylase of the alanine racemase subfamily. A model with iterative condensation reactions using putrescine as substrate has been proposed for FslA13, assigning to it a similar activity as the Rhizopus enzyme. However, the requirement for a decarboxylase in addition to the NIS synthetase for Francisella rhizoferrin production suggests that the pathway could differ from the fungal one. In the current study, we investigated siderophore biosynthesis in F. tularensis using a combination of genetic and biochemical approaches and determined that Francisella has indeed evolved a different pathway for rhizoferrin production that may perhaps reflect an adaptation tailored to its environmental niche.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Ornithine is the primary precursor for rhizoferrin biosynthesis in Francisella.

We first tested if putrescine is a precursor for rhizoferrin synthesis in the F. tularensis strain LVS. Siderophore production in culture supernatants after growth in iron-limiting CDM was quantified using the chrome azurol-S (CAS) assay2,15. Supplementation of the medium with up to 20 mM putrescine had minimal effects on siderophore production by LVS cultures although a minor increase could be detected in isolated experiments with the higher putrescine concentrations (Fig. 1A). Putrescine supplementation had no perceptible effect on growth of the bacteria.

Fig. 1.

Siderophore levels with putrescine or ornithine supplementation. Cultures were grown in iron limiting medium (lo) supplemented with putrescine (P) or ornithine (O) as indicated, and supernatants were assayed for specific CAS activity as an index of siderophore production. A. Siderophore levels in LVS culture supernatants. B. Siderophore production by LVS, ΔfslA and ΔfsiC mutants. C. Complementation of ΔfslA mutant by R. delemar rfs gene. v represents control plasmid vector. Data points represent results from 2–8 independent experiments, with bar heights indicating the mean and error bars representing standard error of the mean. Statistical significance was assessed using one-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s post-hoc tests to compare individual groups with the unsupplemented lo control.

A series of papers in the 1960s described a “growth initiation substance” (GIS) in F. tularensis cultures that, based on biochemical characteristics, was likely to have been rhizoferrin16,17. GIS production was enhanced by addition of ornithine to the medium. In agreement with those early reports, we found that supplementation with 0.2 or 1 mM ornithine significantly enhanced siderophore production by LVS, suggesting that ornithine is the precursor of the Francisella siderophore (Fig. 1A).

We then compared siderophore production in supernatants of the ΔfslA and ΔfsiC mutants of LVS after growth with putrescine and ornithine supplementation. As might be expected, no siderophore activity was detected with the ΔfslA mutant or in the unsupplemented ΔfslC supernatants; however, a small increase in siderophore activity was detected in the ΔfslC supernatant with 1 mM putrescine supplementation (Fig. 1B). This change was variable between experiments with 1 mM putrescine, and showed a marginal increase when putrescine concentrations were raised to 20 mM. These results suggested to us that putrescine could potentially serve as precursor when present at high levels, but that ornithine is the preferred substrate in the normal course.

We then tested the ability of the Rhizopus synthetase Rfs to complement FslA function. Introduction of the rfs gene into the LVS ΔfslA mutant did not result in detectable siderophore activity in culture supernatants and was similar to the vector plasmid control. However, supplementation of the medium with putrescine led to robust siderophore production, as might be expected since putrescine is an identified substrate for Rfs9. Ornithine supplementation led to a modest increase in siderophore activity in isolated experiments, consistent with ornithine being a low affinity substrate for Rfs9. The insignificant siderophore production in the absence of putrescine supplementation would suggest that free putrescine is not abundant in LVS under normal growth conditions. In sum, these results indicated that the siderophore synthetase FslA of Francisella has a substrate preference for ornithine, unlike the putrescine preference of the Rhizopus enzyme.

Potential pathways to Francisella rhizoferrin biosynthesis.

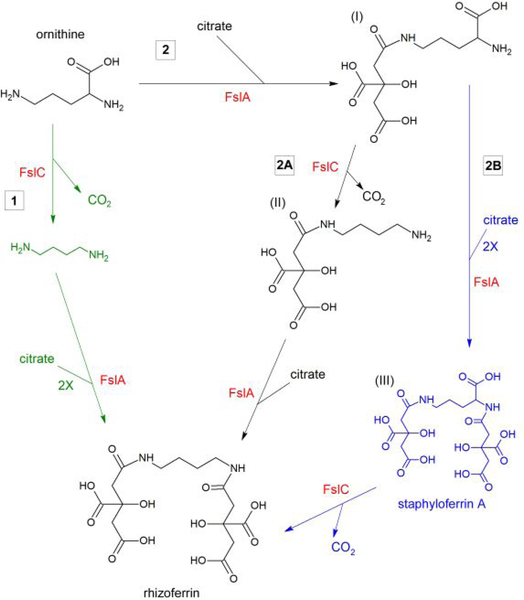

Three potential pathways involving the FslA and FslC enzymes (termed C-A-A, A-C-A, A-A-C based on order of reactions) formally exist for rhizoferrin biosynthesis from ornithine (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Potential pathways to Francisella rhizoferrin biosynthesis from ornithine.

In pathway 1 (C-A-A), decarboxylation of ornithine by FslC to form putrescine is the first step, followed by iterative FslA-mediated amide bond formation with citrate molecules at the two amino groups (as occurs in Rhizopus). FslC here would function as an ornithine decarboxylase (ODC) although an ODC is not annotated in the Francisella genome, and use of the ODC inhibitor difluoromethyl ornithine (DFMO) had no effect on siderophore production by LVS (data not shown). Results reported in Fig. 1 also argue against this pathway: were this pathway operational, the ΔfslC would be expected to display robust siderophore production with putrescine supplementation and the Rfs transformant would be expected to complement the ΔfslA mutant without need for additional putrescine supplementation. Ornithine would also be expected to stimulate siderophore production in the Rfs complemented strain. The poor ability of putrescine to promote siderophore production in LVS, the relatively low level of siderophore activity by the ΔfsiC mutant with putrescine supplementation and the ability of putrescine but not ornithine to promote siderophore production by Rfs in the ΔfslA strain suggest that pathway 1 (C-A-A) is not likely.

In pathway 2, the first step is FslA-mediated amide bond formation with the 8-amino group of ornithine to form intermediate (I), citryl ornithine. Pathway 2A (A-C-A) involves decarboxylation of (I) by FslC to generate intermediate (II) (citryl putrescine), opening up the second amino group for citrate linkage by FslA in a second condensation reaction to produce rhizoferrin. An alternate possibility would be pathway 2B (A-A-C), in which FslA adds on citrate to the second amino group of (I) to generate intermediate III (dicitryl ornithine). FslC would then act to decarboxylate (III) to generate rhizoferrin. (III) resembles the siderophore staphyloferrin A and is predicted to be CAS-active; however, a ΔfsiC mutant is siderophore-deficient. It is also unlikely that a single enzyme FslA could accommodate at its active site both a substrate with a free amino group and one with an additional carboxyl group in its vicinity. Staphyloferrin A synthesis requires two different NIS enzymes to act on the two amino groups18 while the structurally related corynebactin from Corynebacterium diphtheriae is thought to use a single enzyme CiuE with two different NIS synthetase domains to condense two citrates onto the different amino groups of lysine19. Pathway 2A is reminiscent of Staphyloferrin B biosynthesis, wherein the product of the first NIS enzyme needs to be decarboxylated by dedicated decarboxylase SbnH before the second NIS enzyme can act20.

Ornithine rather than putrescine is preferentially incorporated into siderophore by LVS.

To directly test which pathway leads to siderophore formation in LVS, we assessed the ability of the bacteria to incorporate 14C labeled putrescine and ornithine into rhizoferrin. 14C- labelled compounds were added into the labeling medium and 14C content in culture supernatant and cell pellets was determined after 48 hours of growth, at time of maximal siderophore accumulation in the medium. Rhizoferrin can be purified from the supernatant by AG1X-8 anion exchange chromatography; the siderophore is retained on the column, while putrescine and ornithine are not, and the bound siderophore may be eluted with 1.5 M ammonium formate.

CDM contains as a component the polyamine spermine at 200 μM concentration. To rule out the possibility that spermine may outcompete putrescine for uptake by the bacteria, we prepared iron-limiting CDM lacking spermine as the labeling medium and followed incorporation of 14C from [1,4-14C] putrescine (23.4 μM) by LVS. Surprisingly, only ~65% of input radioactivity was recovered after 48 hours (Fig. 3A). Of the recovered radiolabel, ~66% was in the culture supernatant. The supernatant was passed over an AG1X-8 column and ~18% of the radioactivity could be eluted with the siderophore fraction using 1.5 M ammonium formate (Fig. 3B). The cell pellet also retained an appreciable fraction (~33%) of the radioactivity, indicating that putrescine is channeled into other pathways such as, perhaps, polyamine biosynthesis in preference to rhizoferrin formation.

Fig. 3.

Incorporation of radiolabel from 14C putrescine and 14C ornithine into rhizoferrin by LVS. A. Recovery of input radiolabel from 14C- labeled compounds in 48-hour cultures. Absolute counts as cpm in cell pellets and culture supernatants were compared to input radioactivity. B. Distribution of counts from 14C putrescine and [U-14C] ornithine in LVS cultures. 14C in the different fractions is represented as % of radiolabel in the 48-hour cultures. C. HPLC of 14C labeled AG1X-8 eluate spiked with unlabeled siderophore. Fractions were assayed for siderophore activity (left Y axis) and 14C content (right Y axis).

We then tested incorporation from L-[U-14C] ornithine (10 μM) in the same labeling medium. Input radiolabel was quantitatively recovered after the 48-hour growth (Fig. 3A). Almost all the radioactivity remained in the supernatants of all the cultures, with minimal counts detected in the cell pellets (Fig. 3B). Close to 98% of the14C counts in the LVS supernatant were retained on the AG1X-8 column, and could be eluted with the siderophore fraction by 1.5M ammonium formate, reflecting efficient incorporation of the L-[U-14C] ornithine into rhizoferrin. The 14C labeled compound in the AG1X8 eluates co-eluted with purified rhizoferrin during ion-exchange HPLC on a Luna amino column (Fig. 3C). The almost quantitative incorporation of L-[U-14C] ornithine into rhizoferrin in contrast to 14C putrescine suggests that the two precursors have different fates in the cell, with ornithine being primarily channeled into the rhizoferrin biosynthetic pathway.

Radioactivity from [U-14C] ornithine is incorporated into an intermediate by LVS ΔfslC.

We then compared the incorporation of [U-14C] ornithine by LVS with its ΔfslA and ΔfslC mutants (Fig. 4A). Not surprisingly, most of the radioactivity from the culture supernatant of the ΔfslA mutant remained unbound by AG1X-8. 14C counts from the ΔfslC supernatant however, were partially retained on the column and the bound 14C was completely eluted by 1.5 M ammonium formate. However, this fraction remained inactive in a CAS assay, indicating that ornithine was converted to an anionic compound that had no siderophore activity. These results were consistent with the 2A pathway which predicts accumulation of (I) (citryl ornithine) in the ΔfslC mutant (Fig. 2).

Fig. 4.

Detection of siderophore intermediate in ΔfsIC supernatant. A. AG1X-8 binding by supernatants from [U-14C] ornithine labeled cultures. 14C content (cpm) was normalized to the load. B. AG1X-8 chromatography of LVS and ΔfsiC supernatants from [U-14C] ornithine labeled cultures. The supernatants were mixed with unlabeled LVS extract before loading on the column. Fractions were eluted first with 0.3 M and then 1.5 M ammonium formate. Fractions were assayed for siderophore activity in addition to radiolabel content determination (cpm). C. AG1X-8 chromatography of LVS and ΔfsiC supernatants from [1-14C] ornithine labeled cultures. The fractionation was carried out as in B. The radiolabeled ornithine used in each experiment is depicted at the top of the panel, with red asterisks indicating the radioactive atoms. L, load; F, flowthrough. Fractions collected at each salt concentration are indicated by numbers.

With one free amino group and fewer carboxylate groups than rhizoferrin, (I) is less anionic than the siderophore and is therefore predicted to be less tightly bound to the AG1X-8 column. We tested this prediction by attempting to elute the AG1X-8 bound radioactivity from LVS and the ΔfsiC supernatants with lower concentrations of ammonium formate. In keeping with our prediction, the bound 14C counts from the ΔfsiC supernatant could be eluted with 0.3 M ammonium formate; the bound siderophore fraction from the LVS supernatant required the higher 1.5 M salt for elution (Fig. 4B).

Radioactivity from [1-14C] ornithine is incorporated into an intermediate by LVS ΔfsiC.

To more definitively establish the nature of the ΔfsiC intermediate, 1-14C ornithine was added into media, and culture supernatants analyzed as before for AG1X-8 binding. A remarkable loss of counts over 48 hours was seen in the LVS culture, with only 19% of input radioactivity recovered, in contrast to 66% for the ΔfsiC mutant and a 100% for the ΔfsiA mutant (Fig. 3A). Moreover, most of the 14C that remained in the supernatant of LVS passed through AG1X-8 and no significant counts were associated with the siderophore activity eluted using 1.5 M ammonium formate (Fig. 4C). The ΔfsiC supernatant on the other hand, maintained a distinct AG1X-8 binding fraction that was eluted completely with 0.3 M salt. These findings completely support the A-C-A pathway for rhizoferrin biosynthesis, with formation of (I) that retains the single radiolabeled carboxyl group in the ΔfsiC mutant; this group would be lost by FslC-mediated decarboxylation in LVS to form (II) that would then be the substrate for a further condensation reaction by FslA to form rhizoferrin. This pathway would account for the loss of the 1-14C label in the medium of the LVS culture over time, while being largely retained in the ΔfsiC mutant.

Citryl ornithine, the predicted intermediate (I) can be detected in ΔfsiC supernatants.

To conclusively demonstrate the presence of the siderophore intermediate (I), supernatants from LVS, ΔfslA or ΔfsiC cultures in iron-limiting CDM were cleaned on XAD-2 and AG50W columns and passed over an AG1X-8 column. The bound fractions were eluted sequentially with 0.3 and 1.5 M ammonium formate. Each of the fractions was then analyzed by UPLC on a C18 column followed by MS/MS analysis on a qTOF mass analyzer. The strong 437.14 m/z rhizoferrin signal detected in the 1.5 M salt eluate of the LVS supernatant was, as expected, missing in the ΔfsiC extract (Fig. S1). However, a distinct 307.11 m/z ion, not obvious in the LVS and ΔfslA extracts was discernible in the ΔfsiC 0.3 M fraction (Fig. S2, Fig. 5A) and the MS/MS profile of this extracted ion was consistent with citryl ornithine predicted for intermediate (I) (Fig. 5B). No signal for staphyloferrin A (m/z 481.13), indicative of the A-A-C pathway, was detected in the LVS extracts.

Fig. 5.

LC-MS/MS for identification of siderophore intermediate (I). A. Ion chromatogram of AG1X-8 0.3M ammonium formate eluate of ΔfsiC strain supernatant. This fraction had a distinct peak corresponding to 307 m/z not observed in the LVS or ΔfslA supernatants. B. MS/MS of 307.11 m/z. The product ions are consistent with citryl ornithine as parent ion.

Our studies demonstrate that the A-C-A pathway leads to rhizoferrin production in Francisella, beginning with L-ornithine as the precursor for the first condensation reaction by the NIS synthetase FslA, followed by a FslC-dependent decarboxylation step and a second FslA-mediated step. Putrescine is the preferred substrate for the Rhizopus enzyme Rfs9 and is also thought to be the precursor in Legionella where the lbt operon responsible for rhizoferrin production encodes a single enzyme, LbtA8,21. A role for the related protein FrgA encoded elsewhere in the genome of Legionella is not clear22. In a BLAST search, a putative siderophore synthetase from the bacterial pathogen Coxiella burnettii is most closely related to FslA, but no siderophore production has been reported for this organism. A phylogenetic analysis of NIS enzymes known to synthesize the structurally related siderophores rhizoferrin, staphyloferrin A and corynebactin indicates that FslA is more closely related to LbtA and other bacterial NIS synthetases, and rather more distant from the fungal enzyme Rfs23. The FslC decarboxylase is annotated in GenBank as a diaminopimelate decarboxylase (FTL_1832), but is distinct from the actual diaminopimelate decarboxylase FTL_0272 encoded elsewhere in the genome of LVS. A similar decarboxylase is not encoded in the lbt operon of Legionella, suggesting that this enzyme is committed to rhizoferrin production uniquely in Francisella. The absence of a significant citryl-ornithine (I) peak and the absence of a detectable peak corresponding to (II) in LVS supernatants suggests that the intermediates do not accumulate and that the steps in the biosynthetic pathway may be coupled.

The siderophore biosynthetic genes are highly upregulated when F. tularensis is within the intracellular environment14,24, likely as a result of the iron limitation experienced in this niche. Rhizoferrin contributes to survival of F. tularensis within the host as one of two pathways that enable the pathogen to acquire essential iron25,26. Although use of putrescine as precursor substrate requires a single enzyme and therefore might be considered the simplest pathway to rhizoferrin biosynthesis, Francisella has evolved to use ornithine in conjunction with two enzymes. The organism has undergone genome reduction in the process of evolving as a pathogen, and has dispensed with many biosynthetic genes whose products may be available within the host27. Although it encodes enzymes that can convert arginine to putrescine, it is an arginine auxotroph and therefore reliant on the host to provide adequate levels of this amino acid. F. tularensis also lacks ornithine decarboxylase required to generate putrescine from ornithine. To fully satisfy polyamine requirements, the bacteria may therefore need to channel any available putrescine towards spermidine and spermine synthesis or alternately, rely on exogenous host stores of spermine. We speculate that access to an ample store of ornithine, either endogenous or acquired from the host cytoplasm, may perhaps have shaped the evolution of the Francisella rhizoferrin biosynthetic pathway.

METHODS

Bacterial strains and culture.

Francisella tularensis LVS (Live Vaccine Strain) (from K. Elkins, CBER) were grown at 37oC on modified Muller-Hinton agar (DIFCO) supplemented with ferric pyrophosphate, horse serum and 0.1% cysteine (MHA). Chamberlain’s Defined Media containing 2 μg mL−1 FeSO4 (CDM)28 or tryptic soy broth supplemented with 0.1% cysteine (TSB/C) were used for routine liquid culture. Chelex-treated CDM (che-CDM) 29 was supplemented with 0.1 μg mL−1 FeCl3 (0.37 μM) for iron-limiting CDM. Kanamycin, when used, was present at 15 μg mL-1. All solutions and media were prepared in milli-Q (Millipore) water.

Escherichia coli strain MC1061.1 (Δ(araA-leu)7697 araD139 Δ (lac)X74 galK16 galE15 mcrA mcrB1 rpsL150 spoT1 strr hsdR2 λ F- recA) grown in Luria Broth (LB) was used for routine cloning. Ampicillin, when needed, was added to liquid cultures at 50 μg mL−1, and to agar plates at 100 μg mL−1.

rfs clone for complementation of ΔfslA mutant.

The rfs gene of R. delemar was PCR amplified from a pET28 clone using primers 5’CTACTGGCTAGCTTTAAAGGAGTTTTTGATGCCTGTTGCCTCGAGTG 3’ and 5’ CTACTGGGATCCACGCGTGAGCTCTTAGATTGCCTCAGGAACACT 3’ using Q5 DNA polymerase (NEB) and cloned after digestion with enzymes NheI and BamH1 into the pFNLTP6- gro-GFP vector30. The resulting clone had the rfs gene under control of the Francisella groE promoter. After verifying the sequence, the rfs+ clone was introduced into LVS ΔfslA strain GR7 by electroporation and transformants selected on MHA containing15 μg mL−1 kanamycin.

Siderophore detection.

F. tularensis cultures were grown in iron-limiting che-CDM overnight and further diluted in iron-limiting che-CDM with and without supplementation with 1 mM putrescine or DL-ornithine unless otherwise stated. Kanamycin at 10 μg mL−1 was included for growth of the LVS ΔfslA mutant transformed with the rfs clone or control vector pFNLTP6 gro- GFP2. Production of siderophore in supernatants of cultures was detected by the chromazurol-S (CAS) assay adapted to a 96-well plate2,15, using che-CDM as reference blank, with at least three replicates. LVS and mutant assays were conducted after 44–48 hours of growth, whereas plasmid-bearing ΔfslA transformants were assayed after 24 hours of growth. Experiments were repeated from 2–6 times to confirm reproducibility of results. Results were analyzed with one-way ANOVA and Dunnett post-hoc tests using Graphpad Prism Version 6.

Radiolabeling of siderophore and potential intermediates.

LVS and the ΔfslA and ΔfslC mutants were grown for 24 hours in iron-limiting CDM. The bacteria were centrifuged at 8000g for 5 minutes and resuspended to an OD600 of 0.35 in 0.5 mL labeling medium separately in 3 tubes containing one of the 14C -labeled substrates: 10 μM [L- U 14C] ornithine (Amersham CFT180, 9.25 GBq/mmol), 23 μM [1,4-14C] putrescine (Amersham CFA301, 3.96 GBq/mmol) and 100 μM L- ornithine [1-14C] (MP Biomedical cat no. 1010750, 1.76 GBq/mmol). After 48 hours of growth, bacteria in the cultures were centrifuged, and the cell pellets washed once with PBS. The cell pellets were lysed in 0.5 mL 1% SDS for assessing incorporation of radiolabel in cells. Aliquots of supernatants were tested for retention on AG1X-8 beads, and radioactive content in column loads, flow throughs, washes and eluates with 1.5 M ammonium formate (in case of AG1X-8 beads) was assessed by liquid scintillation counting. Fractions were also assessed for CAS activity. In subsequent experiments, aliquots of supernatants bound on AG1X-8 beads were first eluted with 0.3 M ammonium formate, followed by higher salt elution. Aliquots of all fractions were counted in a Beckman liquid scintillation counter in Ecoscint fluor. Unlabeled LVS supernatant was included as “carrier” in some chromatography experiments to reduce background and to provide a marker for rhizoferrin.

HPLC of 14C-labeled siderophore.

AG1X-8 purified siderophore fraction from LVS was dried down and resuspended in water and filtered. 14C putrescine-labeled LVS eluate from an AG1X-8 column was mixed with the unlabeled LVS siderophore fraction for ion exchange HPLC using a Luna amino column (Phenomenex, 250 X 4 mm, 5 μm particles) slightly modified from our previously published protocol 2. The buffer used was 10 mM phosphate pH 7.0 and a sodium chloride gradient of 0–1 M applied from 12– 42 minutes at a flow rate of 0.5 mL/minute at room temperature. 0.5 mL fractions were collected; 0.1 mL aliquots of each fraction were used in CAS assays for siderophore and in parallel, an aliquot of each fraction was tested for radiolabel by scintillation counting.

Siderophore purification for LC-MS.

Cultures of LVS, and ΔfslA and ΔfsIC mutants were grown for 48 hours in iron-limiting CDM. Each culture was centrifuged to pellet cells and the supernatant was filter-sterilized. The supernatant was passed through a column of XAD-2 (Amberlite) beads that had been pre-wet in methanol, and washed with milli-Q water. The flow through was passed through a Dowex 50W-X8 column poured with water. The flow through of this column was brought to neutral pH with NaOH and then applied to an AG1-X8 (formate form) column (Bio-Rad) poured in water. The column was washed with 5 volumes of water and eluted in steps with 0.3 M and 1.5 M ammonium formate. The eluate was lyophilized and resuspended in water.

Mass spectrometry.

The AG1X-8 eluates were resuspended in water and dried down under vacuum 4 times to reduce the amount of the ammonium formate salt. The dried samples were resuspended in 50 μl of 95% water, 5% methanol. 1 μl was injected using an Acquity I-class chromatography system (Waters Corp., Beverly, MA) onto a 2.1mm x 15cm C18-XB column (Phenomenex, Torrance, CA) held at 50°C. Mobile phase A was water with 0.1% formic acid and mobile phase B methanol with 0.1% formic acid. The flow rate was 0.35 mL/min. The gradient consisted of an initial 1 min hold at 100% A for 1 min, then proceeded to 100% B over 8 min before equilibration back to the initial conditions. The eluate was directly analyzed by a Synapt G2-Si qTOF mass spectrometer using MSE, operating in positive ion mode acquiring MS data from 60 −1000 Da with the low energy function and 40 – 1000 Da with the high energy function. Leucine encephalin was used as the lockmass. Data was analyzed using MassLynx 4.1 and MassFragment.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

This work was supported by NIH grant AI067823 (GR) and grants from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (105704) and GlycoNet NCE (AM6) to MMM. NMP was supported in part by an NIH pre-doctoral training grant T32 AI055432.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest. None

References:

- (1).Sjöstedt A, and Sjostedt A. (2007) Tularemia: history, epidemiology, pathogen physiology, and clinical manifestations. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci 1105, 1–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Sullivan JTT, Jeffery EFF, Shannon JDD, and Ramakrishnan G. (2006) Characterization of the siderophore of Francisella tularensis and role of FslA in siderophore production. J. Bacteriol 188, 3785–3795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Deng K, Blick RJ, Liu W, and Hansen EJ (2006) Identification of Francisella tularensis genes affected by iron limitation. Infect. Immun 74, 4224–4236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Ramakrishnan G, Meeker A, and Dragulev B. (2008) fslE is necessary for siderophore-mediated iron acquisition in Francisella tularensis Schu S4. J. Bacteriol 190, 5353–5361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Drechsel H, Metzger J, Freund S, Jung G, Boelaert JR, and Winkelmann G. (1991) Rhizoferrin — a novel siderophore from the fungus Rhizopus microsporus var.rhizopodiformis. Biol. Met 4, 238–243. [Google Scholar]

- (6).Thieken A, and Winkelmann G. (1992) Rhizoferrin: A complexone type siderophore of the Mucorales and Entomophthorales (Zygomycetes). FEMS Microbiol. Lett 94, 37–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Holinsworth B, and Martin JD (2009) Siderophore production by marine-derived fungi. BioMetals 22, 625–632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Burnside DM, Wu Y, Shafaie S, and Cianciotto NP (2015) The Legionella pneumophila siderophore legiobactin is a polycarboxylate that is identical in structure to rhizoferrin. Infect. Immun 83, 3937–3945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Carroll CS, Grieve CL, Murugathasan I, Bennet AJ, Czekster CM, Lui H, Naismith J, and Moore MM (2017) The rhizoferrin biosynthetic gene in the fungal pathogen Rhizopus delemar is a novel member of the NIS gene family. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol 89, 136–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Drechsel H, Jung G, and Winkelmann G. (1992) Stereochemical characterization of rhizoferrin and identification of its dehydration products. BioMetals 5, 141–148. [Google Scholar]

- (11).Münzinger M, Taraz K, Budzikiewicz H, Drechsel H, Heymann P, Winkelmann G, and Meyer JM (1999) S,S-rhizoferrin (enantio-rhizoferrin) - a siderophore of Ralstonia (Pseudomonas) pickettii DSM 6297 - the optical antipode of R,R-rhizoferrin isolated from fungi. BioMetals 12, 189–193. [Google Scholar]

- (12).Challis GL (2005) A widely distributed bacterial pathway for siderophore biosynthesis independent of nonribosomal peptide synthetases. ChemBioChem 6, 601–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Oves-Costales D, Kadi N, and Challis GL (2009) The long-overlooked enzymology of a nonribosomal peptide synthetase-independent pathway for virulence-conferring siderophore biosynthesis. Chem. Commun 6530–6541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Thomas-Charles CA, Zheng H, Palmer LE, Mena P, Thanassi DG, and Furie MB (2013) FeoB-Mediated Uptake of Iron by Francisella tularensis. Infect Immun 81, 2828–2837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Schwyn B, and Neilands JB (1987) Universal chemical assay for the detection and determination of siderophores. Anal. Biochem 160, 47–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Halmann M, and Mager J. (1967) An endogenously produced substance essential for growth initiation of Pasteurella tularensis. J. Gen. Microbiol 49, 461–468. [Google Scholar]

- (17).Halmann M, Benedict M, and Mager J. (1967) Nutritional Requirements of Pasteurella tularensis for growth from small Inocula. J. Gen. Microbiol 49, 451–460. [Google Scholar]

- (18).Cotton JL, Tao J, and Balibar CJ (2009) Identification and characterization of the Staphylococcus aureus gene cluster coding for staphyloferrin A. Biochemistry 48, 1025–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Zajdowicz S, Haller JC, Krafft AE, Hunsucker SW, Mant CT, Duncan MW, Hodges RS, Jones DNM, and Holmes RK (2012) Purification and structural characterization of siderophore (corynebactin) from Corynebacterium diphtheriae. PLoS One 7, e34591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Cheung J, Beasley FC, Liu S, Lajoie GA, and Heinrichs DE (2009) Molecular characterization of staphyloferrin B biosynthesis in Staphylococcus aureus. Mol. Microbiol 74, 594–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Allard KA, Viswanathan VK, and Cianciotto NP (2006) lbtA and lbtB are required for production of the Legionella pneumophila siderophore legiobactin. J. Bacteriol 188, 1351–1363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Hickey EK, and Cianciotto NP (1997) An iron-and fur-repressed Legionella pneumophila gene that promotes intracellular infection and encodes a protein with similarity to the Escherichia coli aerobactin synthetases. Infect. Immun 65, 133–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Carroll CS, and Moore MM (2018) Ironing out siderophore biosynthesis: a review of non-ribosomal peptide synthetase (NRPS)-independent siderophore synthetases. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol 53, 356–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Wehrly TD, Chong A, Virtaneva K, Sturdevant DE, Child R, Edwards JA, Brouwer D, Nair V, Fischer ER, Wicke L, Curda AJ, Kupko JJ 3rd, Martens C, Crane DD, Bosio CM, Porcella SF, and Celli J. (2009) Intracellular biology and virulence determinants of Francisella tularensis revealed by transcriptional profiling inside macrophages. Cell Microbiol 11, 1128–1150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Pérez NM, and Ramakrishnan G. (2014) The reduced genome of the Francisella tularensis live vaccine strain (LVS) encodes two iron acquisition systems essential for optimal growth and virulence. PLoS One 9, e93558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Pérez N, Johnson R, Sen B, and Ramakrishnan G. (2016) Two parallel pathways for ferric and ferrous iron acquisition support growth and virulence of the intracellular pathogen Francisella tularensis Schu S4. MicrobiologyOpen 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Rohmer L, Fong C, Abmayr S, Wasnick M, Larson Freeman TJ, Radey M, Guina T, Svensson K, Hayden HS, Jacobs M, Gallagher LA, Manoil C, Ernst RK, Drees B, Buckley D, Haugen E, Bovee D, Zhou Y, Chang J, Levy R, Lim R, Gillett W, Guenthener D, Kang A, Shaffer SA, Taylor G, Chen J, Gallis B, D’Argenio DA, Forsman M, Olson MV, Goodlett DR, Kaul R, Miller SI, and Brittnacher MJ (2007) Comparison of Francisella tularensis genomes reveals evolutionary events associated with the emergence of human pathogenic strains. Genome Biol 8, R102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Chamberlain RE (1965) Evaluation of live tularemia vaccine prepared in a chemically defined medium. Appl. Microbiol 13, 232–235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Ramakrishnan G, Sen B, and Johnson R. (2012) Paralogous outer membrane proteins mediate uptake of different forms of iron and synergistically govern virulence in Francisella tularensis tularensis. J. Bio.l Chem 287, 25191–25202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Maier TM, Havig A, Casey M, Nano FE, Frank DW, and Zahrt TC (2004) Construction and characterization of a highly efficient Francisella shuttle plasmid. Appl. Env. Microbiol 70, 7511–7519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.