Abstract

For patients with primary or metastatic brain tumors, radiation therapy plays a central role in treatment. However, despite its efficacy, cranial radiation is associated with a range of side effects ranging from mild cognitive impairment to overt brain necrosis. Given the negative effects on patient quality of life, radiation-induced neurotoxicities have been the subject of intense study for decades.

Photon-based therapy has been and largely remains the standard of care for the treatment of brain tumors. This is particularly true for patients with metastatic tumors who may need treatment to the whole brain or those with very aggressive tumors and a limited life expectancy. Particle therapy is now becoming more widely available for clinical use with the two most common particles used being protons and carbon ions. For patients with favorable prognoses, particularly childhood brain tumors, proton therapy is increasingly used for treatment. This is, in part, driven by the desire to reduce the potential for radiation-induced side effects, including lasting cognitive impairment, which may potentially be achieved by reducing dose to normal tissues using the unique physical properties of particle therapy. There is also interest in using carbon ion therapy for the treatment of aggressive brain tumors, as this form of particle therapy not only spares normal tissues but may also improve tumor control.

The biological effects of particle therapy, both proton and carbon, may differ substantially from those of photon radiation. In this review, we briefly describe the unique physical properties of particle therapy that produce differential biological effects. Focusing on the effects of various radiation types on brain parenchyma, we then describe biological effects and potential mechanisms underlying these, comparing to photon studies and highlighting potential clinical implications.

Keywords: proton, carbon, normal tissue toxicity, brain, CNS

Introduction: The Physics Underlying Unique Biological Effects

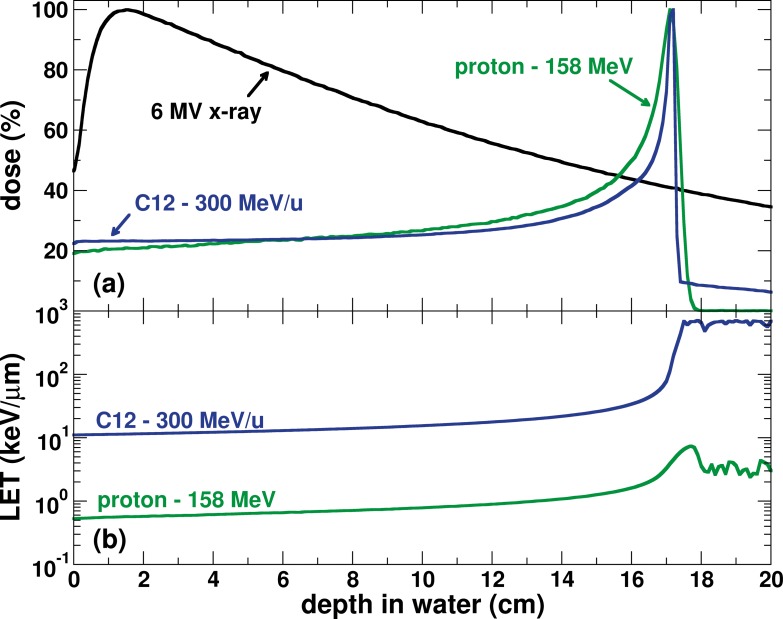

To understand biological differences between radiation types it is essential to have a basic understanding of the physical properties of particle beams and how these differ from photons. Particle therapy using beams such as proton and carbon ions have physical properties that can be used to produce highly compact dose distributions that considerably reduce exposures of normal tissue relative to conventional photon radiotherapy. This spares normal tissues distal to the target volume. Particle beam dose depositions follow the so-called Bragg curve as a function of tissue depth (Figure 1A). Not only the elimination of exit dose but also lower entrance doses can produce superior conformal dose distributions to the target volume compared with photons.

Figure 1.

(A) Dose as a function of depth in water of protons, carbon ions, and x-rays. (B) Fluence-weighted linear energy transfer of protons and carbon ions as functions of depth. X-ray data are from measurements. Proton and carbon ion data are from Monte Carlo simulations using TOPAS.

Proton therapy is the most commonly used particle therapy, followed by carbon ion therapy. Given the favorable dose distributions and decreasing costs for implementation, proton therapy usage is expanding rapidly. In comparison to photon therapy, the number of patients treated with either therapy is miniscule. However, interest in therapy with carbon ions is also growing, as carbon ion therapy is less dependent on hypoxic conditions, is less dependent on cell cycle phase, and has a higher relative biological effectiveness (RBE) than x-rays or protons [1–3], Heavy ions, such as carbon, have improved physical properties compared with photons and protons, namely a sharper penumbra and distal edge [4, 5]. The combined physical and resultant biologic properties have raised hopes that carbon ions will be advantageous for treating radiation-resistant tumors, and initial outcomes are enticing [6, 7].

It is important to highlight that particle therapy, because of the higher density of ionization events along the tracks, is a fundamentally different form of radiation in terms of its biological effects. Especially for proton therapy, this area of research has been understudied in large part due to the prevailing enthusiasm and a line of thought that the translation of decades of photon clinical practice would be straightforward [8]. As particle beams penetrate tissue, their energy deposited per unit path (or linear energy transfer [LET]) increases as a function of depth. For tumor control, radiation-induced DNA damage decreases the proliferative potential of cancerous cells. At the tumor, particle beams inherently have a high LET. Because it relates to the type, complexity, and clustering of radiation-induced DNA damage, LET is an essential factor in determining tumor response. Intrinsically, carbon ions are different from protons and photons because they have a much larger LET range from the entrance to the end of their range. Protons, in contrast, have relatively high LET values only at and just distal to the Bragg peak.

This may offer advantages over photons and protons in that the inherently high LET at the tumor location for carbon ions (Figure 1B), results in greater biological effectiveness and cell kill [9].

The high LET values associated with carbon ion therapy must be accounted for in treatment planning. For example, physical dose may be reduced in distal high LET regions in order to form a uniform biologically effective dose distribution along the beam path. For proton therapy, in clinical practice it has historically been assumed that because high LET regions are restricted to a relatively small portion at the very distal edge of the beam, LET and hence RBE variability can be ignored as long as the distal edge of the beam is not placed in a critical normal tissue. This assumption is increasingly questioned in the literature [10, 11].

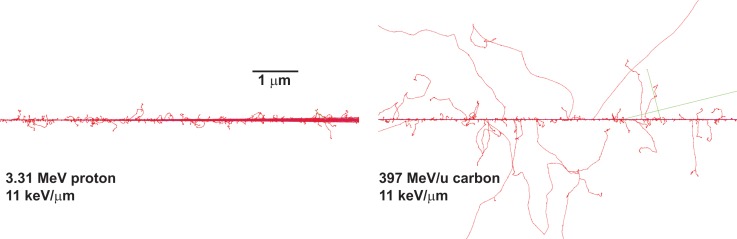

In understanding biological effects, it is useful to consider how dose is deposited at the microscopic level. Each particle track is characterized by its own spatial pattern of energy deposition or track structure. At the core of the track the average ionization density is high. Low-energy particles have a very packed pattern of energy deposition compared with high-energy particles (Figure 2). This is because the secondary electrons have much shorter ranges compared with the ranges of secondary electrons produced by a high Z particle with the same LET (Figure 2). Therefore, the probability of damage in close proximity to each other (clustered damage) is higher for low-energy particles [12]. Therefore, low Z particles with the same LET as an energetic high Z particle have the probability of inducing more localized and clustered damage because the spatial pattern of energy deposition is sparsely distributed for the high Z/energy particle compared with the low Z/energy particle (Figure 2). Consequently, low and high Z particles with the same LET are expected to produce different biological responses.

Figure 2.

Track structure of proton and carbon ion generated using Monte Carlo simulations (TOPAS, version 3.0.1) to illustrate that at the microscopic level the spatial pattern of energy deposition widely differ for particles with different charges but the same linear energy transfer. Perl J; Shin J; Schuemann S; Faddegon BA and Paganetti H: TOPAS - An innovative proton Monte Carlo platform for research and clinical applications. Medical Physics 2012 39: 6818–6837.

The implications of LET variations have received considerable attention in the laboratory, particularly for carbon ions and increasingly so for protons. However, the majority of studies have focused on DNA damage, as this likely relates to tumor control. For radiation-induced brain toxicities, particularly cognitive dysfunction, the relation of DNA damage and subsequent cell loss may not fully describe the toxicities observed. Moreover, for radiation-induced brain parenchymal damage, using beams of clinically relevant energies and fractionated doses, very little is known. However, as described in this article, the number of relevant studies is increasing rapidly, and new biological mechanisms are being explored.

Effects of Particle Therapy on Cognition

Clinically, both adults and children are vulnerable to radiation-induced cognitive dysfunction. However, children are especially sensitive to these adverse effects, a fact that has driven much of the rapid expansion in proton therapy. In the clinical practice of pediatric radiation oncology for brain tumors, patients may be roughly divided into 2 groups, those requiring only focal radiation or those that require radiation to the craniospinal axis (CSI). The unique physical properties of protons are ideally suited for each group. For patients receiving focal radiation, particle therapy spares much brain tissue distal to the target volume and thus may help improve cognitive outcomes. For patients requiring CSI, beams used to treat the spine stop before exposing organs at risk, such as heart and bowel. thereby reducing or eliminating the potential for radiation-induced heart disease and secondary visceral malignancies. However, for patients treated for diseases such as medulloblastoma, where CSI is used, the entire brain is still included in the target volume, and, as such, patients remain at risk for long-term cognitive decline [13, 14].

While studies directly comparing the effects of radiation types on brain parenchyma using clinically relevant beam energies and doses are limited, much can be learned from investigations of studies conducted with protons and heavier ions delivered at differing dose rates and high energies. Such studies have been designed to be relevant to the exposures astronauts might receive on an extended mission, such as a Mars mission. Regarding the effects of particle radiation on cognition, in a recent study examining the effects of galactic cosmic radiation, low doses of gamma radiation were compared with high-energy protons and heavy ions [15]. Detailed animal behavioral testing was performed with assessments of memory, anxiety, and other measures up to 12 months following exposure. Comparing gamma- and proton-treated animals experiencing the same physical low dose exposure of 1 Gy, both groups had deficits in recognition memory at 9 months, with proton-treated animals also showing deficits at 5 months. While this study was not specifically designed to directly compare radiation types (ie, to develop an RBE for cognitive decline), it suggests that the negative effects of protons on cognition may be qualitatively similar to that for photons, even at low doses. Because many pediatric patients treated with protons will require CSI, cognitive deficits should still be expected, and a more detailed investigation comparing radiation types and mechanisms underlying radiation-induced changes is warranted. This is particularly true for carbon ions, which have not historically been used in the treatment of pediatric patients.

The RBE for Clonogenic Survival: Neurogenesis

For decades, clonogenic survival has been the “gold standard” for studies of radiation effectiveness including comparing radiation modalities and the effects of drugs. The idea of radiation-induced cell kill has also been extrapolated in an attempt to describe the adverse effects of radiation on cognition. Indeed, it has been well established that cranial irradiation does indeed reduce the proliferation of neuronal precursors in the hippocampus [16–18]. Similar to photon exposure, high-energy proton exposure (again relevant to space radiation but not clinical energies), even at low doses, resulted in a loss of proliferative potential in the dentate gyrus and subgranular zone [19]. In vitro work has also shown sensitivity of neuronal precursor cells to photon and proton irradiation, accompanied by radiation-induced oxidative stress [20]. Modeling studies also suggest that heavy ion irradiation, including carbon ions, will likely lead to sustained deficits in neurogenesis [21].

Impact of Particles on Neuronal Structure and Function

It is now generally accepted that deficits in neurogenesis alone may not fully describe the negative effects of radiation on cognition. For normal tissues, numerous cell types are involved in the response to radiation. New evidence indicates that surviving cells, including neurons, contribute to cognitive dysfunction after brain radiation. Neurons process and transmit information in the brain and are therefore responsible for cognition. Although neurons survive therapeutic doses of radiation therapy, changes in their ability to transmit information can have profound consequences on the function and long-term survival of nearly all cell types in the brain [22].

Drugs that prevent cognitive decline in experimental models may not protect against deficits in neurogenesis or chronic brain inflammation, and very little neurogenesis occurs in the adult brain [23]. Intriguingly, recent studies report long-term changes in neuronal structure after radiation [24, 25]. Specifically, both acute and long-term alterations in dendritic structure have been reported [26]. Dendritic spines are small, actin-rich protrusions that house most excitatory synapses in the central nervous system. Changes in dendritic spine structure and density of dendritic spines generally correlate with changes in synaptic number and strength. Similar to photon treatments, low-dose (1 Gy) proton exposure in mice results in persistent changes in the number, density, and structural properties of dendritic spines [27]. Such changes may also be modulated through the manipulation of oxidative stress [28]. Additionally, heavy charged particles, such as oxygen delivered at doses as low as 5 cGy, may exhibit similar impacts on dendritic structure [29].

While imaging of neuronal structure provides a useful measure, it is also possible to directly interrogate the functional properties of synapses using electrophysiological recordings. Synaptic plasticity refers to the concept that brief periods of use provoke long-lasting changes in synaptic efficacy, a phenomenon widely believed to underlie learning and memory. One form of synaptic plasticity is long-term potentiation (LTP), in which brief high-frequency stimulation leads to long-lasting increases in synaptic efficacy [30, 31]. Conversely, long-term depression is induced by prolonged low-frequency stimulation. In the hippocampus, AMPA (α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid)-type ionotropic glutamate receptors mediate fast excitatory synaptic signaling, and NMDA (N-methyl-d-aspartate)-type ionotropic glutamate receptors direct changes in synaptic plasticity [32, 33].

For photon radiation, Pellmar and colleagues [34, 35] were the first to document acute radiation-induced changes in basal synaptic transmission in the CA1 region of the hippocampus. However, synaptic plasticity was not examined. Investigators studying the role of neuronal stem cells in learning and memory have used radiation as a tool to deplete proliferative cells and in doing so have documented long-term effects on synaptic function, including diminished LTP [36]. Inhibition of LTP has also been demonstrated to occur within 30 minutes of radiation exposure, and there appears to be distinct age dependence in determining the persistence of radiation-induced LTP deficits [37, 38]. Exploring potential mechanisms underlying long-term deficits in synaptic plasticity, Shi et al [39] were the first to directly study the long-term effects of radiation on glutamate receptor expression. In adult animals, spatial learning was impaired 12 months after fractionated whole-brain radiation, and altered expression of NMDA receptors subunits GluN1 and GluN2A were identified. Other researchers have revealed clear abnormalities in glutamate uptake both in neurons and astrocytes after radiation [40]. Given the increasing use of protons clinically, as well as the potential implications for space travel, recent work has also investigated the effects of proton therapy on synaptic transmission. Following whole-body exposure to 150 MeV protons at a low dose (0.5 Gy, relevant to space travel), an enhanced release of the inhibitory neurotransmitter GABA (gamma-aminobutyric acid) that is specific to certain neuronal subpopulations was noted [41]. Similar low-dose proton exposures have also been performed in transgenic mouse models of Alzheimer's disease, where it was observed that following proton exposure, genotype dependent alterations in synaptic efficacy occur, including alterations in presynaptic function [42].

Particle Therapy Induced Neuroinflammation and Effects on Glial Support Cells

Photon-based studies have shown that radiation induces sustained changes in the brain microenvironment [43, 44]. Brain irradiation initiates an inflammatory response mediated by glial and endothelial cells, which compromises the blood-brain barrier, results in demyelination, reduces proliferation and initiates a chronic inflammatory milieu [45, 46]. Cranial radiation induces an increase in tumor necrosis factor–α and nuclear factor–κB signaling and a decrease in brain-derived neurotropic factor levels in the brain after treatment with single and fractionated CRT [47–50]. Brain-derived neurotropic factor plays a key role in supporting neuronal development and function, so this phenomenon may be clinically relevant. A recent report showed preliminary evidence that reduction in neuroinflammation might be one of the effects of voluntary exercise that works toward ameliorating the radiation-induced cognitive decline observed in a rodent model of cranial irradiation [51]. This persistent neuroinflammation may also be in part responsible for shunting remaining viable neuronal precursor cells toward a glial fate [52, 53].

With proton exposures, microglial activation similar to that caused by photon treatments has been recorded [54]. Interestingly, when proton exposures were combined with heavy ion exposure (Fe-ion), differential expression of cytokines, including interleukin (IL)-12, IL-4, IL-6 and tumor necrosis factor–alpha, were recorded. While Fe-ion radiation is not used clinically, this raises the question of whether ions heavier than protons, such as carbon, may have similar differential properties.

Radiation-Induced Brain Necrosis with Particle Therapy

Radiation-induced brain necrosis represents one of the most serious adverse effects and may lead to neurologic decline or even death. Within the pediatric neuro-oncology field there has been concern that patients treated with proton therapy experience higher rates of radiation necrosis. This is increasingly realized in the literature. In 1 published study, when restricted to posterior fossa tumors, 12.5% of patients age <5 years treated with proton therapy had symptomatic brainstem injury [55]. However, it is important to note that in the absence of studies directly randomizing between photon and proton therapy, assessing differences in the incidence of radiation necrosis between patient populations is problematic. Such concerns prompted a workshop in May 2016, cohosted by the Children's Oncology Group and the National Cancer Institute [56]. At the workshop it was noted that rates of symptomatic necrosis remain low in the setting of careful treatment planning and the use of strict brainstem constraints. However, it was also accepted that the high LET regions of the proton beam likely have increased biological effectiveness and that there exists a need to better understand and exploit the biologic effects of such regions [56].

Our own group has documented increased rates of post-radiotherapy imaging changes in patients treated with focal proton therapy compared with photons [57]. Imaging changes reflect early parenchymal damage. It is important to note that with current proton treatment planning techniques, beam regions that may have higher LET and hence RBE values greater than 1.1 are nearly always within normal tissues just distal to the target volume. This differs substantially from treatment planning for carbon ion therapy where the very high LET variations and values necessitate the incorporation of predicted biologic effects into the planning process. In order to provide clinical data suggesting an LET effect, we analyzed pediatric ependymoma patients treated with proton therapy. Fourteen patients who developed imaging changes after proton therapy were recalculated using Monte Carlo to generate dose and LET distributions [10]. These distributions where then correlated with regions of image change using a voxel-level analysis [10]. It was found that higher LET values, not only dose, were associated with damage to normal brain parenchyma. Limitations of such studies obviously include the small number of patients and the lack of information on potential radiation sensitivities of individuals as a function of genotype (an area not discussed here). However, such results do indicate additional study is warranted.

Radiation necrosis is a complex toxicity with an ambiguous etiology likely stemming from multiple factors. The fact that there are no reported in vitro models with which to study this serious side effect may be indicative that such a disease cannot be reproduced in overly simplified in vitro models. Recently developed animal models consist of a large single radiation fraction with long-term monitoring. Most often advanced imaging techniques are utilized to quantify signal changes, often in the setting of attempts to differentiate tumor recurrence from radiation necrosis [58, 59].

The prevailing hypotheses regarding the etiology of radiation necrosis include damage to endothelial and glial support cells [60], This may include damage to oligodendrocytes with subsequent demyelination. Endothelial cell damage and dysfunction, accompanied by ischemia and abnormal angiogenesis, may in part explain the efficacy of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor in the prevention or treatment of radiation-induced necrosis [61, 62], Each of these changes is also accompanied by ongoing neuroinflammation and a release of inflammatory cytokines as well as hypoxia-induced activation of hypoxia-inducible factor–1α expression [61, 63],

Animal models studying proton-induced brain necrosis are surprisingly sparse. In 1 study investigators utilized proton or helium ion beams to irradiate the right hemisphere of mouse brains with large single-fraction doses. Animals were then followed with serial magnetic resonance imaging [64]. Imaging demonstrated late changes on T2-weighted magnetic resonance images consistent with clinical changes seen in patients, and histologic analysis confirmed the presence of necrotic changes. Similar studies have been conducted with carbon ions [65], Here the delivery of a physical dose of 50 Gy in a single fraction resulted in histologically proven radiation necrosis at earlier time points than observed in the work centering on proton therapy. Such experimental setups are challenging; however, the use of fractionated radiation and spatial correlation of imaging and histologic changes with both dose and LET could provide novel data on proton-induced neurotoxicity.

Summary

Particle therapy is fundamentally different from photon radiation both in terms of physical factors and biological effects. Data comparing the effects of various radiation types on brain parenchyma is surprisingly limited. While there are a considerable number of publications reporting on low-dose, high-energy, or high-LET exposures, these may not be directly clinically relevant. Equally as important, very few, if any, studies of normal tissue toxicity following particle therapy have attempted to relate biological outcomes to physical factors beyond just dose. As described previously, energy deposition patterns differ greatly as a function of ion type and energy, and factors such as LET may be incorporated into the treatment planning process. In the design of future studies, it will be important to include variations in dose and LET in assessing various biological responses. Moreover, given the trend for hypofractionation with carbon therapy, assessment of various fractionation schemes will be essential.

Regardless of the limitations, in the available literature, both similarities and differences can be observed in the response of brain parenchyma to various radiation types. Clinically, it is becoming more apparent that for proton therapy, LET should be implicitly incorporated into the treatment planning process. With newer proton delivery modalities, such as intensity modulated proton therapy delivered with pristine scanned proton beams, we have the opportunity to vary the placement of high LET regions. Such techniques are already in use for carbon ion therapy. However, for both protons and carbon ions, the choice of appropriate biologic effect models to use in the treatment planning process remains unclear. If high-quality biologic response data can be generated that describe the effects of various radiation types on neurotoxicities, this can be used to develop biologic effect models for treatment planning in order to improve clinical outcomes.

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION AND DECLARATIONS

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Acknowledgments: This work was supported by the Cancer Prevention Research Institute of Texas RP140430, NIH CA208535 (to DRG), NIH MH086119 (to JGD).

References

- 1.Schlaff CD, Krauze A, Belard A, O'Connell JJ, Camphausen KA. Bringing the heavy: carbon ion therapy in the radiobiological and clinical context. Radiat. Oncol. 2014;9:88. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-9-88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kamada T, Tsujii H, Blakely EA, Debus J, Neve WD, Durante M, Jäkel O, Mayer R, Orecchia R, Pötter R, Vatnitsky S, Chu WT. Carbon ion radiotherapy in Japan: an assessment of 20 years of clinical experience. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:e93–100. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70412-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Durante M, Loeffler JS. Charged particles in radiation oncology. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2010;7:37–43. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2009.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Suit H, DeLaney T, Goldberg S, Paganetti H, Clasie B, Gerweck L, Niemierko A, Hall E, Flanz J, Hallman J, Trofimov A. Proton vs carbon ion beams in the definitive radiation treatment of cancer patients. Radiother Oncol. 2010;95:3–22. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2010.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tessonnier T, Mairani A, Brons S, Haberer T, Debus J, Parodi K. Experimental dosimetric comparison of (1)H, (4)He, (12)C and (16)O scanned ion beams. Phys Med Biol. 2017;62:3958–82. doi: 10.1088/1361-6560/aa6516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rieken S, Habermehl D, Haberer T, Jaekel O, Debus J, Combs SE. Proton and carbon ion radiotherapy for primary brain tumors delivered with active raster scanning at the Heidelberg Ion Therapy Center (HIT): early treatment results and study concepts. Radiat Oncol. 2012;7:41. doi: 10.1186/748-717X-7-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hirohiko T, Tadashi K, Masayuki B, Hiroshi T, Hirotoshi K, Shingo K, Shigeru Y, Shigeo Y, Takeshi Y, Hiroyuki K, Ryusuke H, Naotaka Y, Junetsu M. Clinical advantages of carbon-ion radiotherapy. New J Phys. 2008;10:075009. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paganetti H, Niemierko A, Ancukiewicz M, Gerweck LE, Goitein M, Loeffler JS, Suit HD. Relative biological effectiveness (RBE) values for proton beam therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;53:407–21. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(02)02754-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hall EJ. Radiobiology for the Radiologist Vol 1. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins;; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peeler CR, Mirkovic D, Titt U, Blanchard P, Gunther JR, Mahajan A, Mohan R, Grosshans DR. Clinical evidence of variable proton biological effectiveness in pediatric patients treated for ependymoma. Radiother Oncol. 2016;121:295–401. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2016.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Unkelbach J, Botas P, Giantsoudi D, Gorissen BL, Paganetti H. Reoptimization of intensity modulated proton therapy plans based on linear energy transfer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2016;96:1097–106. doi: 10.16/j.ijrobp.2016.08.038. Epub Sep 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Friedland W, Schmitt E, Kundrát P, Dingfelder M, Baiocco G, Barbieri S, Ottolenghi A. Comprehensive track-structure based evaluation of DNA damage by light ions from radiotherapy-relevant energies down to stopping. Sci Rep. 2017;7:45161. doi: 10.1038/srep45161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kahalley LS, Ris MD, Grosshans DR, Okcu MF, Paulino AC, Chintagumpala M, Moore BD, Guffey D, Minard CG, Stancel HH, Mahajan A. Comparing intelligence quotient change after treatment with proton versus photon radiation therapy for pediatric brain tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:1043–9. doi: 10.200/JCO.2015.62.1383. Epub 2016 Jan 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Antonini TN, Ris MD, Grosshans DR, Mahajan A, Okcu MF, Chintagumpala M, Paulino A, Child AE, Orobio J, Stancel HH, Kahalley LS. Attention, processing speed, and executive functioning in pediatric brain tumor survivors treated with proton beam radiation therapy. Radiother Oncol. 2017;124:89–97. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2017.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Patel R, Arakawa H, Radivoyevitch T, Gerson SL, Welford SM. Long-term deficits in behavior performances caused by low- and high-linear energy transfer radiation. Radiat Res. 2017;188:672–80. doi: 10.1667/RR14795.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Monje ML, Mizumatsu S, Fike JR, Palmer TD. Irradiation induces neural precursor-cell dysfunction. Nat Med. 2002;8:955–62. doi: 10.1038/nm749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tada E, Parent JM, Lowenstein DH, Fike JR. X-irradiation causes a prolonged reduction in cell proliferation in the dentate gyrus of adult rats. Neuroscience. 2000;99:33–41. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00151-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mizumatsu S, Monje ML, Morhardt DR, Rola R, Palmer TD, Fike JR. Extreme sensitivity of adult neurogenesis to low doses of X-irradiation. Cancer Res. 2003;63:4021–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sweet TB, Panda N, Hein AM, Das SL, Hurley SD, Olschowka JA, Williams JP, O'Banion MK. Central nervous system effects of whole-body proton irradiation. Radiat Res. 2014;182:18–34. doi: 10.1667/RR13699.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tseng BP, Lan ML, Tran KK, Acharya MM, Giedzinski E, Limoli CL. Characterizing low dose and dose rate effects in rodent and human neural stem cells exposed to proton and gamma irradiation. Redox Biol. 2013;1:153–62. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2013.01.008. :10.1016/j.redox.2013.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cacao E, Cucinotta FA. Modeling heavy-ion impairment of hippocampal neurogenesis after acute and fractionated irradiation. Radiat Res. 2016;186:624–37. doi: 10.1667/RR14569.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Deisseroth K, Singla S, Toda H, Monje M, Palmer TD, Malenka RC. Excitation–neurogenesis coupling in adult neural stem/progenitor cells. Neuron. 2004;42:535–52. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00266-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Conner KR, Forbes ME, Lee WH, Lee YW, Riddle DR. AT1 receptor antagonism does not influence early radiation-induced changes in microglial activation or neurogenesis in the normal rat brain. Radiat Res. 2011;176:71–83. doi: 10.1667/rr2560.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Parihar VK, Limoli CL. Cranial irradiation compromises neuronal architecture in the hippocampus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:12822–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1307301110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chakraborti A, Allen A, Allen B, Rosi S, Fike JR. Cranial irradiation alters dendritic spine density and morphology in the hippocampus. PLoS One. 2012 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040844. 7:e40844. Epub 2012 Jul 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Duman JG, Dinh J, Zhou W, Cham H, Mavratsas VC, Paveskovic M, Mulherkar S, McGovern SL, Tolias KF, Grosshans DR. Memantine prevents acute radiation-induced toxicities at hippocampal excitatory synapses. Neuro Oncol. 2018;20:655–65. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nox203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Parihar VK, Pasha J, Tran KK, Craver BM, Acharya MM, Limoli CL. Persistent changes in neuronal structure and synaptic plasticity caused by proton irradiation. Brain Struct Funct. 2015;220:1161–71. doi: 10.007/s00429-014-0709-9. Epub 2014 Jan 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chmielewski NN, Caressi C, Giedzinski E, Parihar VK, Limoli CL. Contrasting the effects of proton irradiation on dendritic complexity of subiculum neurons in wild type and MCAT mice. Environ Mol Mutagen. 2016;57:364–71. doi: 10.1002/em.22006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parihar VK, Allen BD, Caressi C, Kwok S, Chu E, Tran KK, Chmielewski NN, Giedzinski E, Acharya MM, Britten RA, Baulch JE, Limoli CL. Cosmic radiation exposure and persistent cognitive dysfunction. Sci Rep. 2016;6:34774. doi: 10.1038/srep34774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Malenka RC, Nicoll RA. Long-term potentiation—a decade of progress? Science. 1999;285:1870–4. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5435.1870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Collingridge GL, Isaac JT, Wang YT. Receptor trafficking and synaptic plasticity. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:952–62. doi: 10.1038/nrn1556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.MacDonald JF, Jackson MF, Beazely MA. Hippocampal long-term synaptic plasticity and signal amplification of NMDA receptors. Crit Rev Neurobiol. 2006;18:71–84. doi: 10.1615/critrevneurobiol.v18.i1-2.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu L, Wong TP, Pozza MF, Lingenhoehl K, Wang Y, Sheng M, Auberson YP, Wang YT. Role of NMDA receptor subtypes in governing the direction of hippocampal synaptic plasticity. Science. 2004;304:1021–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1096615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pellmar TC, Lepinski DL. Gamma radiation (5-10 Gy) impairs neuronal function in the guinea pig hippocampus. Radiat Res. 1993;136:255–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pellmar TC, Schauer DA, Zeman GH. Time- and dose-dependent changes in neuronal activity produced by X radiation in brain slices. Radiat Res. 1990;122:209–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Snyder JS, Kee N, Wojtowicz JM. Effects of adult neurogenesis on synaptic plasticity in the rat dentate gyrus. J Neurophysiol. 2001;85:2423–31. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.85.6.2423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu PH, Coultrap S, Pinnix C, Davies KD, Tailor R, Ang KK, Browning MD, Grosshans DR. Radiation induces acute alterations in neuronal function. PLoS One. 2012 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037677. 7:e37677. Epub 2012 May 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Zhang D, Zhou W, Lam TT, Weng C, Bronk L, Ma D, Wang Q, Duman JG, Dougherty PM, Grosshans DR. Radiation induces age-dependent deficits in cortical synaptic plasticity. Neuro Oncol. 2018 doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noy052. ePub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Shi L, Adams MM, Long A, Carter CC, Bennett C, Sonntag WE, Nicolle MM, Robbins M, D'Agostino R, Brunso-Bechtold JK. Spatial learning and memory deficits after whole-brain irradiation are associated with changes in NMDA receptor subunits in the hippocampus. Radiat Res. 2006;166:892–9. doi: 10.1667/RR0588.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sanchez MC, Benitez A, Ortloff L, Green LM. Alterations in glutamate uptake in NT2-derived neurons and astrocytes after exposure to gamma radiation. Radiat Res. 2009;171:41–52. doi: 10.1667/RR361.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee SH, Dudok B, Parihar VK, Jung KM, Zoldi M, Kang YJ, Maroso M, Alexander AL, Nelson GA, Piomelli D, Katona I, Limoli CL, Soltesz I. Neurophysiology of space travel: energetic solar particles cause cell type-specific plasticity of neurotransmission. Brain Struct Funct. 2017;222:2345–57. doi: 10.1007/s00429-016-1345-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rudobeck E, Bellone JA, Szucs A, Bonnick K, Mehrotra-Carter S, Badaut J, Nelson GA, Hartman RE, Vlkolinsky R. Low-dose proton radiation effects in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer's disease - Implications for space travel. PloS one. 2017;12:e0186168. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0186168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hong JH, Chiang CS, Campbell IL, Sun JR, Withers HR, McBride WH. Induction of acute phase gene expression by brain irradiation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1995;33:619–26. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(95)00279-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee WH, Sonntag WE, Mitschelen M, Yan H, Lee YW. Irradiation induces regionally specific alterations in pro-inflammatory environments in rat brain. Int J Radiat Biol. 2010;86:132–44. doi: 10.3109/09553000903419346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gaber MW, Naimark MD, Kiani MF. Dysfunctional microvascular conducted response in irradiated normal tissue. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2003;510:391–5. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-0205-0_65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yuan H, Gaber MW, McColgan T, Naimark MD, Kiani MF, Merchant TE. Radiation-induced permeability and leukocyte adhesion in the rat blood-brain barrier: modulation with anti-ICAM-1 antibodies. Brain Res. 2003;969:59–69. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)02278-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gaber MW, Sabek OM, Fukatsu K, Wilcox HG, Kiani MF, Merchant TE. Differences in ICAM-1 and TNF-alpha expression between large single fraction and fractionated irradiation in mouse brain. Int J Radiat Biol. 2003;79:359–66. doi: 10.1080/0955300031000114738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wilson CM, Gaber MW, Sabek OM, Zawaski JA, Merchant TE. Radiation-induced astrogliosis and blood-brain barrier damage can be abrogated using anti-TNF treatment. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;74:934–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.02.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rodgers SP, Trevino M, Zawaski JA, Gaber MW, Leasure JL. Neurogenesis, exercise, and cognitive late effects of pediatric radiotherapy. Neural Plast. 2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/698528. 2013:698528. Epub 2013 Apr 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 50.Rodgers SP, Zawaski JA, Sahnoune I, Leasure JL, Gaber MW. Radiation-induced growth retardation and microstructural and metabolite abnormalities in the hippocampus. Neural Plast. 2016 doi: 10.1155/2016/3259621. 2016:3259621. Epub 2016 May 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.Sahnoune I, Inoue T, Kesler SR, Rodgers SP, Sabek OM, Pedersen SE, Zawaski JA, Nelson KH, Ris MD, Leasure JL, Gaber MW. Exercise ameliorates neurocognitive impairments in a translational model of pediatric radiotherapy. Neuro Oncol. 2018;20:695–704. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nox197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Monje ML, Toda H, Palmer TD. Inflammatory blockade restores adult hippocampal neurogenesis. Science. 2003;302:1760–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1088417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jenrow KA, Brown SL, Lapanowski K, Naei H, Kolozsvary A, Kim JH. Selective inhibition of microglia-mediated neuroinflammation mitigates radiation-induced cognitive impairment. Radiat Res. 2013;179:549–56. doi: 10.1667/RR3026.1. Epub 2013 Apr 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Raber J, Allen AR, Sharma S, Allen B, Rosi S, Olsen RH, Davis MJ, Eiwaz M, Fike JR, Nelson GA. Effects of proton and combined proton and (56)Fe radiation on the hippocampus. Radiat Res. 2016;185:20–30. doi: 10.1667/RR14222.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Indelicato DJ, Flampouri S, Rotondo RL, Bradley JA, Morris CG, Aldana PR, Sandler E, Mendenhall NP. Incidence and dosimetric parameters of pediatric brainstem toxicity following proton therapy. Acta Oncol. 2014;53:1298–304. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2014.957414. Epub 2014 Oct 3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Haas-Kogan D, Indelicato D, Paganetti H, Esiashvili N, Mahajan A, Yock T, Flampouri S, MacDonald S, Fouladi M, Stephen K, Kalapurakal J, Terezakis S, Kooy H, Grosshans D, Makrigiorgos M, Mishra K, Poussaint TY, Cohen K, Fitzgerald T, Gondi V, Liu A, Michalski J, Mirkovic D, Mohan R, Perkins S, Wong K, Vikram B, Buchsbaum J, Kun L. National Cancer Institute Workshop on Proton Therapy for Children: Considerations Regarding Brainstem Injury. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2018;101:152–68. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2018.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gunther JR, Sato M, Chintagumpala M, Ketonen L, Jones JY, Allen PK, Paulino AC, Okcu MF, Su JM, Weinberg J, Boehling NS, Khatua S, Adesina A, Dauser R, Whitehead WE, Mahajan A. Imaging changes in pediatric intracranial ependymoma patients treated with proton beam radiation therapy compared to intensity modulated radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2015;93:54–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2015.05.018. Epub May 16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang S, Tryggestad E, Zhou T, Armour M, Wen Z, Fu DX, Ford E, van Zijl PC, Zhou J. Assessment of MRI parameters as imaging biomarkers for radiation necrosis in the rat brain. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;83:e431–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.12.087. Epub 2 Apr 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhou J, Tryggestad E, Wen Z, Lal B, Zhou T, Grossman R, Wang S, Yan K, Fu DX, Ford E, Tyler B, Blakeley J, Laterra J, van Zijl PC. Differentiation between glioma and radiation necrosis using molecular magnetic resonance imaging of endogenous proteins and peptides. Nature Med. 2011;17:130–4. doi: 10.1038/nm.2268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Furuse M, Nonoguchi N, Kawabata S, Miyatake S, Kuroiwa T. Delayed brain radiation necrosis: pathological review and new molecular targets for treatment. Med Mol Morphol. 2015;48:183–90. doi: 10.1007/s00795-015-0123-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yoritsune E, Furuse M, Kuwabara H, Miyata T, Nonoguchi N, Kawabata S, Hayasaki H, Kuroiwa T, Ono K, Shibayama Y, Miyatake S. Inflammation as well as angiogenesis may participate in the pathophysiology of brain radiation necrosis. J Radiat Res. 2014;55:803–11. doi: 10.1093/jrr/rru017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jiang X, Engelbach JA, Yuan L, Cates J, Gao F, Drzymala RE, Hallahan DE, Rich KM, Schmidt RE, Ackerman JJ, Garbow JR. Anti-VEGF antibodies mitigate the development of radiation necrosis in mouse brain. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:2695–702. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-1941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yang R, Duan C, Yuan L, Engelbach JA, Tsien CI, Beeman SC, Perez-Torres CJ, Ge X, Rich KM, Ackerman JJH, Garbow JR. Inhibitors of HIF-1alpha and CXCR4 nitigate the development of radiation necrosis in mouse brain. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2018;100:1016–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2017.12.257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kondo N, Sakurai Y, Takata T, Takai N, Nakagawa Y, Tanaka H, Watanabe T, Kume K, Toho T, Miyatake S, Suzuki M, Masunaga S, Ono K. Localized radiation necrosis model in mouse brain using proton ion beams. Appl Radiat Isot. 2015;106:242–6. doi: 10.1016/j.apradiso.2015.07.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sun XZ, Takahashi S, Kubota Y, Zhang R, Cui C, Nojima K, Fukui Y. Experimental model for irradiating a restricted region of the rat brain using heavy-ion beams. J Med Invest. 2004;51:103–7. doi: 10.2152/jmi.51.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]