Abstract

Perceiving a complex visual scene and encoding it into memory involves a hierarchical distributed network of brain regions, most notably the hippocampus (HIPP), parahippocampal gyrus (PHG), lingual gyrus (LNG), and inferior frontal gyrus (IFG). Lesion and imaging studies in humans have suggested that these regions are involved in spatial information processing as well as novelty and memory encoding; however, the relative contributions of these regions of interest (ROIs) are poorly understood. This study investigated regional dissociations in spatial information and novelty processing in the context of memory encoding using a 2 × 2 factorial design with factors Novelty (novel vs. repeated) and Stimulus (viewing scenes with rich vs. poor spatial information). Greater activation was observed in the right than left hemisphere; however, hemispheric effects did not differ across regions, novelty, or stimulus type. Significant novelty effects were observed in all four regions. A significant ROI × Stimulus interaction was observed—spatial information processing effects were largest effects in the LNG, significant in the PHG and HIPP and nonsignificant in the IFG. Novelty processing was stimulus dependent in the LNG and stimulus independent in the PHG, HIPP, and IFG. Analysis of the profile of Novelty × Stimulus interaction across ROIs provided evidence for a hierarchical independence in novelty processing characterized by increased dissociation from spatial information processing. Despite these differences in spatial information processing, memory performance for novel scenes with rich and poor spatial information was not significantly different. Memory performance was inversely correlated with right IFG activation, suggesting the involvement of this region in strategically flawed encoding effort. Stepwise regression analysis revealed that memory encoding accounted for only a small fraction of the variance (< 16%) in medial temporal lobe activation. The implications of these results for spatial information, novelty, and memory processing in each stage of the distributed network are discussed. Hum. Brain Mapping 11:117–129, 2000. © 2000 Wiley‐Liss, Inc.

Keywords: hippocampal formation, hippocampus, parahippocampal gyrus, lingual gyrus, prefrontal cortex, inferior frontal gyrus

INTRODUCTION

Perceiving a complex visual scene and encoding it for subsequent memory recall is a critical brain function involving a distributed network of brain structures [Felleman and Van Essen, 1991; Squire and Zola, 1997]. A basic network to accomplish these functions includes the lingual gyrus (LNG), parahippocampal gyrus (PHG), hippocampus (HIPP), and the inferior frontal gyrus (IFG). The PHG sits at the pinnacle of sensory processing [Amaral, 1999]; it receives convergent input from a number of high‐level visual areas, particularly the LNG. The entorhinal cortex in the PHG provides highly processed visual information into the hippocampus via the perforant pathway. The HIPP contribution to processing the sensory input is characterized by a unique feedback loop that projects output back into the entorhinal cortex [Buzsaki, 1996]. The HIPP is therefore tightly coupled to the PHG. Together, the PHG and HIPP are critically involved in higher order sensory processing and its transformation to memory. The HIPP and PHG have strong projections to the IFG and there is growing evidence from lesion studies that interaction between the hippocampal formation and PFC is critical for memory encoding [Parker and Gaffan, 1998].

One line of research exploring PHG and HIPP function in humans has drawn on prior electrophysiological recordings in animals. These studies focused on spatial and topographic aspects of visual scene analysis and implicated the HIPP, in particular, in formation of metastable spatial maps of the visual environment [O'Keefe et al., 1998]. In humans, hippocampal lesions have been shown to impair spatial navigation and spatial memory for object location [Milner et al., 1997; Pigott and Milner, 1993; Smith and Milner, 1981, 1989]. PET imaging studies have variously suggested that memory for object location is mediated by dorsal regions of prestriate cortex [Owen et al., 1996] or right mesial temporal regions [Johnsrude et al., 1999]. Human brain imaging studies have also variably suggested the involvement of the HIPP and PHG in processing, acquisition and recall of topographic information [Maguire, 1997; Maguire et al., 1996, 1997, 1998a, 1998b]. Epstein and Kanwisher [1998] proposed that the right parahippocampal cortex is a “place area” that codes for the spatial layout of the local visual environment. However, based on their findings of increased activation to buildings compared to other objects, Aguirre et al. [1998] proposed that the right LNG is critical for coding topographic landmarks and may be a more appropriate “place area.” Lesion studies have also variably pointed to the roles of the PHG and ventral‐temporal occipital cortex in topographic orientation [Bohbot et al., 1998; Habib and Sirigu, 1987; Milner et al., 1997]. These results leave unclear the relative profile of activation of the LNG, PHG, and HIPP to analysis of complex visuo‐spatial information.

A parallel line of research has investigated the role of these structures in novelty processing and memory encoding. Novelty processing involves distinguishing between new and familiar stimuli and has been used to operationalize memory encoding [Martin, 1999]. One common assumption in the literature is that novelty processing represents an early stage of memory encoding [Tulving et al., 1996]. Although novelty processing has been conflated with memory encoding, few studies have investigated LNG, PHG, and HIPP activation in relation to novelty processing and memory performance, and attempted to dissociate novelty processing and memory encoding. Activation to novel stimuli may primarily reflect novelty detection unrelated to memory encoding, perhaps resulting from increased attention or even arousal [Martin, 1999]. It is also possible that the effects of novelty on memory are confounded with other types of processing; few studies have addressed whether activation differs across conditions that are equally novel and whether such a difference might be related to memory performance.

Although the relationship between the two processes is poorly understood, human brain imaging studies have nevertheless been successful in demonstrating activation of the PHG and HIPP during the processing of novel visual scenes under a variety of experimental conditions. This data, however, has numerous discrepancies. PET studies have generally implicated the anterior HIPP in novelty processing [Lepage et al., 1998], while fMRI studies have implicated the posterior PHG [Schacter and Wagner, 1999]. Stern et al. [1996] reported fMRI activation in the right posterior PHG, HIPP, and LNG during processing of novel, compared to repeated, pictures when subjects were told to remember scenes for future recall. Greater activation to novel, compared to repeated, presentation of visual scenes has been reported in the right PHG during passive viewing conditions [Tulving et al., 1994, 1996], bilaterally in the PHG during an incidental categorization task [Gabrieli et al., 1997], and in the HIPP and PHG during encoding of novel picture‐word associations [Rombouts et al., 1997]. While these studies have reported either bilateral or right hemisphere activation, Montaldi et al. [1998] reported predominantly left HIPP/PHG activation during encoding of novel picture‐picture associations. Although encoding studies have mainly focused on the PHG and HIPP, researchers have also consistently reported novelty related activation outside this region. Most notably, such activation has also been reported in the temporo‐occipital cortex [Stern et al., 1996; Tulving et al., 1994], dorsolateral prefrontal cortex [Fletcher et al., 1997; Montaldi et al., 1998] and the posterior and inferior prefrontal cortex [Buckner et al., 1999; Wagner et al., 1998].

In summary, imaging studies to date have variously reported the involvement of the LNG, PHG, and HIPP in visuo‐spatial information processing as well as novelty detection; and the PHG, HIPP, and IFG in encoding the processed novel information into memory. However, no single study has investigated the relation between these processes within a single within‐subject experimental design. A logical next step would be to explore the relationship between novelty and spatial information (SI) processing in the context of memory encoding in these structures. In order to rigorously claim that a profile of activation is present in one region or hemisphere and not in the other, it is imperative to analyze the statistical interaction terms within the framework of a factorial design.

We investigated the profile of regional differences by analyzing the interaction between novelty and SI processing in the PHG, HIPP, LNG, and IFG. Novelty and the degree of SI processing were manipulated by presenting subjects with novel or repeated visual scenes that were rich or poor in SI. Our use of a factorial task design represents a methodological advancement over previous work and allows for a delineation of the relative contributions of these regions to SI and novelty processing and their overall relation to memory encoding.

Some of the questions the study sought to answer were: What is the relation between novelty and SI processing in these structures? What is the differential activation of these structures to visual scenes that are rich and poor in SI? Do differences in SI processing emerge in the LNG or do they appear further downstream in the PHG? Is novelty detection performed early in the visual stream before the information reaches the PHG and, if it is, in what way does it differ from novelty processing in the PHG and HIPP? To what extent is PHG activation dominated by SI processing, novelty processing, and memory encoding? What is the relation between LNG, PHG, HIPP, and PFC activation and overall memory performance? What is the joint predictive value of activation in the different regions to overall memory performance?

METHODS

Subjects

Thirteen healthy right‐handed subjects (5 males and 8 females, ages 16–23 years) rated the images that were used in the scanner. Twenty other healthy right‐handed subjects (11 males and 9 females, ages 16–30 years) participated in the fMRI study after giving written informed consent.

Stimuli

Natural, outdoor scenes were presented that were either rich or poor in SI (RSI or PSI). RSI scenes consisted of a visual environment rich in objects and landmarks—e.g., houses, buildings, trees, boats—which bore a distinct spatial relationship with each other (Fig. 1, top). These landmarks could enable subjects to make judgements about the relative position and scale of the objects to each other and assess their mutual spatial relationships. PSI scenes, on the other hand, consisted of large‐scale scenes with objects—e.g., mountains and clouds—that provided little information about the relative positions and scale of the objects with respect to each other (Fig. 1, bottom).

Figure 1.

Examples of outdoor scenes with rich and poor spatial information (RSI and PSI) used in the study. RSI scenes (top row) contained several identifiable objects that bore a distinct spatial relation and scale to each other (landmarks). PSI scenes (bottom row) contained objects—e.g., mountains and clouds—that provided little information about the relative positions and scale of the objects with respect to each other.

Stimulus rating

A group of 13 subjects who did not participate in the imaging component of the study rated the visual scenes that were used in the study. Subjects presented their answer on a Likert type scale, where 1 represented the lowest degree and 5 represented the highest. They answered four questions for every image: (1) “To what degree can you give a good approximation of the size of the objects in this picture?” (2) “To what degree can you give a good approximation of the distances between the objects in this image?” (3) “Knowing that a landmark is a familiar object which helps you understand the spatial relationships within a scene, how many landmarks can you identify in this scene?” (4) “How easy would it be for you to draw an accurate map of this scene with enough spatial information for someone else to be able to successfully navigate through it?”

Two‐tailed paired‐measures t‐tests indicated that subjects found it significantly easier (t(12) = 7.31; P = 9.0 andtimes; 10−6) to approximate the size of objects in RSI scenes (m = 3.72, s = 0.68) than in PSI (m = 1.94, s = 0.45) scenes. Subjects also found it significantly easier (t(12) = 8.69; P = 2 × 10−6) to approximate the distances between objects in the RSI (m = 3.31, s = 0.66) than PSI (m = 1.87, s = 0.54) scenes. In addition, subjects identified more landmarks in RSI than PSI scenes (t(12) = 5.16; P = 2.3 × 10−4); most subjects found between 6 and 15 landmarks in RSI (m = 2.50, s = 0.92) and between 0 and 5 (m = 1.29, s = 0.55) landmarks in a PSI scenes. Subjects found more spatial information that enabled easier navigation (t(12) = 4.99; P = 3.1 × 10−4) in the RSI (m = 3.22, s = 0.70) than PSI scenes (m = 1.86, s = 0.66). These results show that RSI scenes had significantly more spatial information than PSI scenes.

Experimental design

Subjects viewed photographs of natural, outdoor scenes presented in one of four conditions in a 2 × 2 factorial design with the factors consisting of (1) novelty (novel or repeated stimuli) and (2) stimuli (RSI or PSI scenes). In the novel condition, subjects viewed a new stimulus each time. In the repeated condition, the same stimulus was presented throughout the entire condition. The experiment began with a 30 sec rest epoch, followed by 12 24‐sec‐epochs of viewing images in each of the four conditions, and ended with a 30‐sec rest epoch (total time: 5 min, 48 sec). Having more replications per condition would have involved asking subjects to encode more stimuli of each condition. This would have decreased memory performance in the postscan test to chance levels thereby precluding analysis of the relation between memory and brain activation. During each 24‐sec epoch, eight scenes were presented with an ISI of 3 sec. The epochs alternated between presentation of novel RSI, repeated RSI, novel PSI, and repeated PSI scenes. The order of presentations was counterbalanced for novelty to eliminate any recency effects on memory performance and activation. Subjects were instructed to study and remember the pictures. Immediately following the scan, they performed a yes/no recognition task with 32 RSI and 32 PSI scenes. Two‐thirds of the scenes were chosen from the stimuli previously seen in the scanner; the remaining scenes were completely novel.

fMRI acquisition

Images were acquired on a 1.5T GE Signa scanner with Echospeed gradients using a custom‐built whole‐head coil that provided a 50% advantage in signal to noise ratio over that of the standard GE coil [Hayes and Mathias, 1996]. A custom‐built head holder was used to prevent head movement. Eighteen axial slices (6 mm thick, 1 mm skip) parallel to the anterior and posterior commissure covering the whole brain were imaged with a temporal resolution of 2 sec using a T2* weighted gradient echo spiral pulse sequence (TR = 2,000 msec, TE = 40 msec, flip angle = 89° and 1 interleave) [Glover and Lai, 1998]. The field of view was 240 mm and the effective inplane spatial resolution was 4.35 mm. To aid in localization of functional data, a high resolution T1 weighted spoiled grass gradient recalled (SPGR) 3D MRI sequence with the following parameters was used: TR = 24 msec; TE = 5 msec; flip angle = 40°; 24 cm field of view; 124 slices in coronal plane; 256 × 192 matrix.

fMRI analysis

fMRI data from each subject was analyzed using SPM96 (http://www.fil.ion.bpmf.ac.uk/spm). Prior to statistical analysis, images were corrected for movement using least square minimization without higher‐order corrections for spin history, normalized to stereotaxic Talairach coordinates [Talairach and Tournoux, 1988], resampled every 2 mm using sinc interpolation and smoothed with a 4 mm Gaussian kernel to eliminate spatial noise. For each subject, voxel‐wise activation during each of the four conditions compared to rest was determined using multivariate regression analysis with correction for temporal autocorrelations in the fMRI data [Friston et al., 1995]. Confounding effects of fluctuations in global mean were removed by proportional scaling and low frequency noise was removed with a high pass filter (0.5 cycles/min). A regressor waveform for each condition, convolved with a 6s delay Poisson function accounting for delay and dispersion in the haemodynamic response, was used to compute voxel‐wise t‐statistics which were then normalized to Z scores to provide a statistical measure of activation that is independent of sample size. Brain activation for each of the four experimental conditions, contrasted with the rest condition, was determined: (1) novel RSI, (2) novel PSI, (3) repeated RSI, and (4) repeated PSI. A threshold of Z > 2.33 (P < 0.01) was used to identify significantly activated voxels. The percentage of voxels activated in each ROI was then entered into an analysis of variance to determine task‐related differences in activation.

ROI

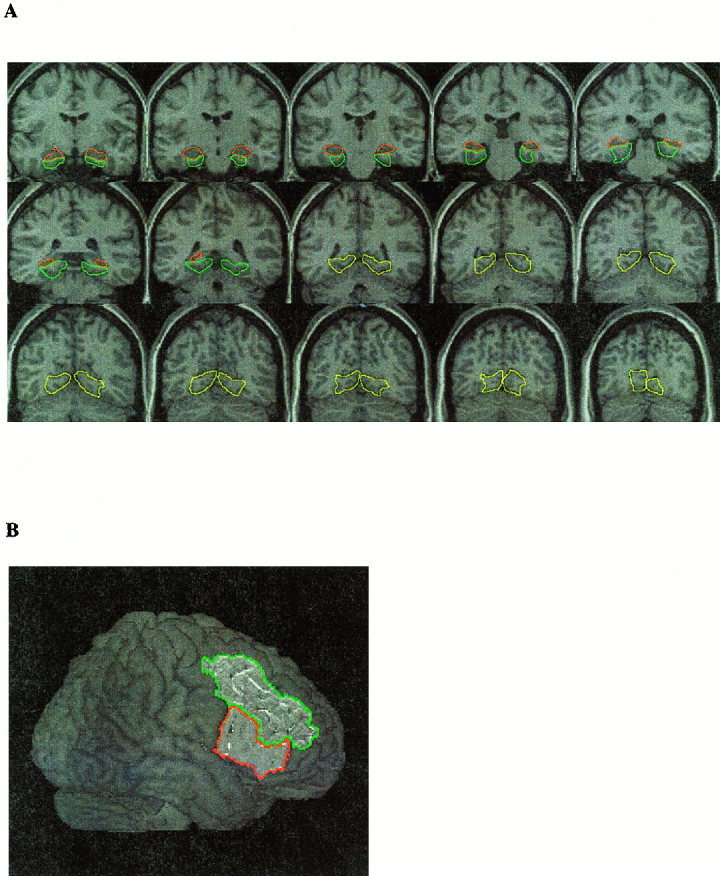

ROIs were demarcated in the left and right hemispheres from the average (n = 20 subjects) T1‐weighted Talairach normalized images (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Regions of interest (ROIs) were marked on average, Talairach‐normalized, high‐resolution structural images obtained from the 20 subjects used in the present study. (A) Left and right hemisphere lingual gyrus (shown in yellow), parahippocampal gyrus (shown in blue) and hippocampus (shown in red). (B) Inferior (shown in red) and middle frontal gyri (shown in blue). The protocol used to demarcate these structures is described in the text.

HIPP and PHG

Details of the protocol used for defining the hippocampus have been published elsewhere [Kates et al., 1997] and are based largely on the Duvernoy atlas [Duvernoy, 1998]. Briefly, the anterior slice of the HIPP was defined as the slice at which the temporal horn of the lateral ventricles points superiomedially, and was positioned so that the amygdala was located superior and the hippocampus inferior to the temporal horn. Posteriorly, the HIPP fuses with the fornix and was measured until it was no longer visible on coronal slices. The medial border was defined by the ambient cistern. The inferior border was marked by the collateral white matter, the subiculum and the PHG. The lateral border was marked by the temporal horn of the lateral ventricles and more superiorly by white matter. The anterior border of the PHG, separating it from the entorhinal cortex, was arbitrarily set at the same level as hippocampus. The posterior limit of the PHG was defined by the slice where the corpus callosum ends. Laterally, the PHG was separated from the fusiform gyrus by the collateral sulcus. In the anterior slices, the medio‐superior border was marked by the point where the subiculum extends horizontally to the most medial part of the temporal lobe. More posteriorly, the medio‐superior limit was defined by the anterior calcarine sulcus.

LNG

LNG is defined here as the combination of superior and inferior lingual gyri. There is no intrinsic anatomical distinction to allow separation of PHG from LNG. In the coronal plane, the most anterior slice of the LNG was defined as the one immediately following the PHG; that is, the first slice following the splitting of corpus collosum. The superior border of the LNG was marked by the anterior calcarine sulcus. The inferior border of the LNG was defined by the posterior transverse collateral sulcus. The medial mark was defined by a straight line joining the gray‐white border of the deepest points between calcarine and collateral sulcus.

IFG

Using a surface rendering of the average brain, the anterior border was identified by the junction of the lateral orbital sulcus and inferior frontal sulcus. The posterior border was defined by the precentral sulcus. The superior border was defined by the inferior frontal sulcus. The inferior border was defined by the lateral orbital sulcus until its end. For the most posterior part of the IFG, the inferior border was the horizontal ramus of the lateral fissure. Medially, the border was defined by a straight line joining the deepest point of the inferior frontal sulci and the deepest point of the lateral orbital sulci. These definitions closely followed surface sulci demarcated by Duvernoy [1991] and Ono et al. [1990].

MFG

An additional ROI covering the MFG was used for a limited set of post‐hoc tests. The superior frontal sulcus defined the medial boundary for this region. The frontomarginal sulcus and the inferior frontal sulcus defined the lateral boundary. At more posterior slices where the inferior frontal sulcus disappears, the superior precentral sulcus was used as the lateral boundary. The posterior boundary for this region was the precentral gyrus.

Statistical analysis of fMRI data

To statistically compare activation across novelty and stimulus types in the four ROIs and two hemispheres, a four‐way repeated measures ANOVA with factors ROI (HIPP, PHG, LNG, and IFG), HEMISPHERE (left, right), NOVELTY (novel, repeated) and SI (RSI, PSI) was undertaken. A standard analysis framework [Keppel and Zedeck, 1989] with the percent voxels activated in each ROI was used as the measure of activation. We used an alpha‐level for significance of P < 0.05 (two‐tailed). Nonsignificant trends (P < 0.1; two‐tailed) are also noted as such.

Behavioral data analysis

The percentage of correct and false alarm responses during the postscan recognition memory task were computed. Overall memory performance was indexed with Dprime [Hochhaus, 1972] using corrections for unequal variance between the correct and false alarm responses [Theodor, 1972].

Analysis of relation between fMRI data and recognition memory

Stepwise forward regression analyses were then utilized to measure the collective predictive value of activation in the eight ROIs to Dprime. A threshold of F ≥ 3.0 was used to determine inclusion or exclusion of variables.

RESULTS

Behavioral

Memory performance was assessed on a yes/no recognition task from 12 subjects following the scan. Mean recognition scores did not differ significantly (t(11) = 1.09; P = 0.30) between the RSI and PSI scenes. Subjects recognized 60.1% (s = 14.8) of RSI and 56.6% (s = 17.4) of PSI scenes. Although Dprime scores for the RSI scenes (m = 2.12, s = 0.83) exceeded scores for the PSI scenes (m = 1.62, s = 0.82), the difference was not statistically significant (t(11) = 1.83; P = 0.095). Reaction time (RT) for RSI scenes (m = 1224.50 msec, s = 94.51) and PSI scenes (m = 1180.92 msec, s = 93.18) did not differ significantly (t(11) = 1.02; P = 0.3).

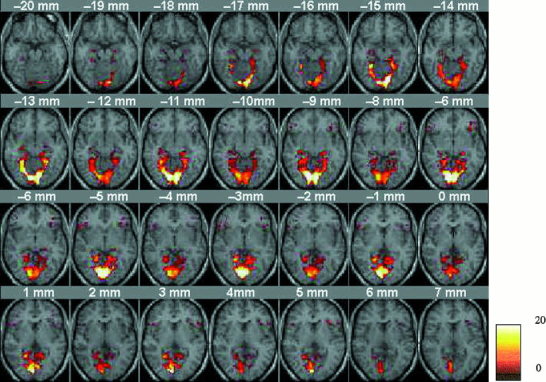

Activation

Figure 3 shows a composite map of activation to novel RSI, compared to rest, in the left and right LNG, PHG, HIPP, and IFG across the 20 subjects. To statistically compare activation across novelty and stimulus types in the four ROIs and two hemispheres, a four‐way repeated measures ANOVA was performed.

Figure 3.

Composite map of activation across 20 subjects, in the lingual gyrus, parahippocampal gyrus, hippocampus, and inferior prefrontal gyrus, to visual scenes that were rich in spatial information (RSI). The activation height of each voxel represents the number of subjects who activated that voxel. This map is shown for illustrative purposes. Statistical analysis of activation across conditions and subjects was conducted using an ANOVA on the percentage of voxels activated by each subject in each ROI.

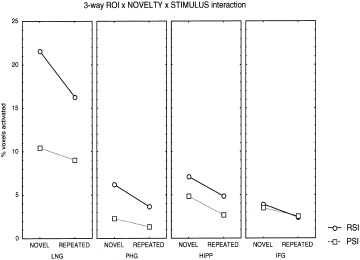

The results of the four‐way ANOVA are summarized in Table I. Significant main effects were found for all four factors: ROI (LNG > PHG, HIPP, IFG), HEMISPHERE (right > left), NOVELTY (novel > repeated) and STIMULUS (RSI >PSI). The analysis revealed a significant ROI × NOVELTY × STIMULUS interaction (P = 0.015). Figure 4 shows the plot of means for NOVELTY × STIMULUS interaction in each of the four ROI. Follow‐up analysis of NOVELTY × STIMULUS interaction in each ROI revealed significant interaction in the LNG (F(1,19) = 8.97; P = 0.008), a nonsignificant trend in the PHG (F(1,19) = 3.26; P = 0.08), but no significant interaction in the HIPP (F(1,19) = 0.01; P = 0.91), or the IFG (F(1,19) = 0.78; P = 0.38).

Table I.

Results of 4‐way ANOVA with factors ROI (LNG, PHG, HIPP and IFG), hemisphere (HEM) (left, right), novelty (novel, repeated), and spatial information (SI) (RSI, PSI scenes)

| Effect | df | F | p‐level |

|---|---|---|---|

| ROI | 3, 57 | 33.52 | <0.001 |

| HEM | 1, 19 | 9.09 | 0.007 |

| NOVELTY | 1, 19 | 14.15 | 0.001 |

| STIMULUS | 1, 19 | 34.90 | <0.001 |

| ROI × HEM | 3, 57 | 2.23 | 0.094 |

| ROI × NOVELTY | 3, 57 | 2.61 | 0.059 |

| HEM × NOVELTY | 1, 19 | 0.62 | 0.437 |

| ROI × STIMULUS | 3, 57 | 28.66 | <0.001 |

| HEM × STIMULUS | 1, 19 | 4.14 | 0.056 |

| NOVELTY × STIMULUS | 1, 19 | 5.34 | 0.032 |

| ROI × HEM × STIMULUS | 3, 57 | 0.33 | 0.799 |

| ROI × HEM × STIMULUS | 3, 57 | 2.52 | 0.066 |

| ROI × NOVEL × STIMULUS | 3, 57 | 3.77 | 0.015 |

| HEM × NOVELTY × STIMULUS | 1, 19 | 0.00 | 0.986 |

| ROI × HEM × NOVELTY × STIMULUS | 3, 57 | 0.35 | 0.787 |

Figure 4.

Plot of means showing significant three‐way ROI × NOVELTY × STIMULUS interaction. There was significant NOVELTY × STIMULUS interaction in the LNG but not in the HIPP, PHG, or IFG. Note the increasing trend towards nonsignificant interaction from the PHG to the HIPP. No interaction effects or main effects of spatial information processing were seen in the IFG.

We then directly compared activation to novel and repeated scenes in the different ROIs. Given the significant ROI × NOVELTY × STIMULUS interaction, we analyzed the ROI × NOVELTY interaction separately for the RSI and PSI scenes. For RSI scenes, there was a significant ROI × NOVELTY interaction (F(3,57) = 4.05; P = 0.011). Follow‐up analysis of this interaction showed that the largest differences between novel and repeated stimuli occurred in the LNG (F(1,19) = 17.05; P = 0. 0005), followed by the IFG (F(1,19) = 9.40; P = 0.006) and the PHG (F(1,19) = 8.50; P = 0.008). A nonsignificant trend was observed in the HIPP (F(1,19) = 3.34; P = 0.083). For PSI scenes, ROI × NOVELTY interaction was not significant (F(3,57) = 0.97; P = 0.408).

Next, we compared activation between RSI and PSI scenes in the different ROIs. Given the significant ROI × NOVELTY × STIMULUS interaction, we analyzed the ROI × STIMULUS interaction separately for novel and repeated scenes. For novel scenes, there was a significant ROI × STIMULUS interaction. Follow‐up analysis of this interaction showed that activation to novel RSI and PSI scenes differed significantly in the LNG (F(1,19) = 42.71; P = 0. 000003), PHG (F(1,19) = 13.41; P = 0.001) and HIPP (F(1,19) = 5.32; P = 0.032) but not the IFG (F(1,19) = 0.56; P = 0.463). For repeated scenes also, there was a significant ROI × STIMULUS interaction. Follow‐up analysis of this interaction showed that activation to repeated RSI and PSI scenes differed significantly in the LNG (F(1,19) = 30.44; P = 0. 00026), PHG (F(1,19) = 13.45; P = 0.001), and HIPP (F(1,19) = 7.95; P = 0.010) but not the IFG (F(1,19) = 0.09; P = 0.767).

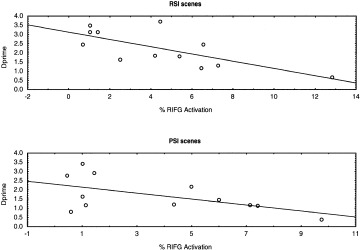

Relationship between activation and memory performance

Stepwise forward regression analyses were then utilized to measure the predictive value of activation in the eight ROIs to memory performance as indexed by Dprime. A threshold of F ≥ 3.0 was used to determine inclusion or exclusion of variables. For PSI scenes, activation in the right IFG was the only predictor of memory performance to approach significance (R2 = 0.32; P = 0.057), indicating that increased right IFG activation was related to lower performance (Table II).

Table II.

Stepwise multiple regression analysis of relation between activation in each ROI and overall memory performance as indexed by Dprime*

| Stimulus | Significant predictors | Beta | R2 | p‐value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (F to enter = 3.0) | ||||

| PSI scenes | Step 1: Right IFG | −0.56 | 0.32 | 0. 0573 |

| RSI scenes | Step 1: Right IFG | −0.87 | 0.51 | 0. 0013 |

| Step 2: Right PHG | 0.42 | 0.16 | 0. 0139 |

For each region that was entered in the model (F to enter = 3.0), beta weights and significance levels are provided. Contributions to variance explained are represented by the R‐squared values for each particular step.

For the more complex RSI scenes, activation in two regions accounted for a significant (R2 = 0.67, P = 0.007) proportion of the variance in Dprime. The first variable entered was activation in the right IFG (R2 = 0.51; P = 0.008); thus, activation in this region accounted for 51% of the variance in memory performance. A significant negative partial correlation indicated that increased activation in this region was associated with lower performance (see Table II). The second variable entered was activation in the right PHG (change in R2 = 0.16; P = 0.007); thus, activation in this region showed a significant positive partial correlation with Dprime and accounted for an additional 16% of the explained variance.

In summary, an inverse relation between recognition memory performance and activation was observed for both RSI and PSI scenes in the right IFG (Fig. 5). The magnitude of the correlation was greater for the more complex, RSI scenes. However, only for the RSI scenes was there a significant partial positive correlation in the right PHG.

Figure 5.

Inverse correlation between right IFG activation and overall memory performance as indexed by Dprime for scenes with rich (RSI, top) and poor (PSI, bottom) spatial information.

Middle frontal gyrus

In view of the unexpected finding of inverse correlation between IFG activation and memory performance, we conducted post‐hoc tests investigating the pattern of activation in the adjoining MFG. Activation in this region has been reported during memory encoding conditions in previous research [Montaldi et al., 1998]. There were no significant effects of hemisphere (F(1,19) = 0.30; P = 0.59) or stimulus (F(1,19) = 0.53; P = 0.47); but a nonsignificant trend for novelty was observed (F(1,19) = 4.10; P = 0.066). Further, no relation was found between right MFG activation and memory performance for either RSI (ρ = −0.358; P = 0.253) or PSI (ρ = −0.068; P = 0.834).

DISCUSSION

The current study represents a methodological advancement in the analysis of regional dissociations in a network of brain regions involved in processing spatial information and encoding it into memory. Spatial information processing, novelty, and memory encoding were found to differentially affect the profile of activation in the HIPP, PHG, LNG, and IFG as described below. Overall, there was larger activation of the right than left hemisphere; however, hemispheric effects did not differ across regions, novelty, or stimulus type.

Spatial information processing

There were salient regional differences in processing of RSI and PSI scenes as indicated by a highly significant ROI by Stimulus interaction. The LNG, PHG, and HIPP showed significantly greater activation to RSI than PSI scenes. The largest differences were seen in the LNG. No differences were found in the IFG and follow‐up analysis showed no differences in the MFG. These results indicate that the effects of visuo‐spatial complexity are limited to the LNG, PHG, and HIPP and do not extend to the prefrontal cortex. Both RSI and PSI showed greater activation in the right than left hemisphere. This is in agreement with lesion studies suggesting that right, but not left, PHG lesions result in topographic disorientation and discrimination of object‐place location [Bohbot et al., 1998; Milner et al., 1997; Pigott and Milner, 1993]. Our results of decreased sensitivity to stimulus features as one moves anteriorly through the distributed system are in good agreement with the perceptual properties of visually responsive neurons reported in the monkey literature [Xiang and Brown, 1999].

Our results address some of the discrepancies in the recent literature regarding SI processing. Contrary to reports of a unique “place area” in the PHG that responds to landmarks [Epstein and Kanwisher, 1998], we found greater changes related to processing of visuo‐spatial complexity in the LNG, as suggested by Aguirre et al. [1998]. However, the PHG also showed significant differences between processing scenes with rich and poor SI. Further, in agreement with some prior studies [Maguire, 1997], differences in SI processing were also found to extend to the HIPP. The present results are also consistent with the suggestion that the human PHG and HIPP are sensitive to the type of SI in the visual environment [Epstein and Kanwisher, 1998]. In summary, SI processing is initiated early in the visual stream and continues in the PHG and HIPP.

Novelty processing

All four ROIs showed significantly greater activation to novel, compared to repeated, spatial scenes. ROIs differed in the magnitude of novelty‐related activation to RSI, but not PSI, scenes. For RSI scenes, the largest novelty effects were observed in the LNG, with smaller but significant effects in the PHG, HIPP, and IFG. Although most prior studies of novelty processing have focused on the PHG and HIPP, our results indicate that this process is initiated earlier in the visual stream. There were no hemispheric differences in novelty processing as evidenced by a lack of Hemisphere × Novelty interaction. Further, this hemispheric symmetry did not vary across the ROIs as shown by a lack of ROI × Hemisphere × Novelty interaction. These results provide evidence that novelty processing is more widely distributed than SI processing across brain regions and hemispheres. Significant novelty effects were observed in the IFG but not the MFG, suggesting a regional specificity for novelty detection within the prefrontal cortex.

Memory encoding

Although postscan recognition memory for RSI and PSI scenes was not different, activation of the HIPP, PHG, and LNG was significantly greater during processing of RSI scenes. This suggests that there are significant components in the activation, not only in the LNG but also in the HIPP and PHG, that are not related to subsequent recognition memory per se. This observation is further clarified by our result that no ROI except the right IFG and right PHG showed significant correlation of brain activation with memory performance. Further, a stepwise forward multiple regression analysis suggested that memory performance accounts for a small fraction of the variance in the activation of the HIPP, PHG, and LNG. Thus, our results indicate that activation of these regions is not dominated by memory encoding processes per se, and further suggest that novelty processing cannot be conflated with memory encoding.

In spite of the lack of hemispheric differences in activation of the IFG, only the right IFG activation showed an inverse correlation with memory performance as indexed by Dprime. In other words, subjects who performed well tended to have lower activity in the right IFG. Further, the inverse relation appears to be specific to the IFG; a post‐hoc test revealed no such relation in the MFG. While there have been reports of inverse correlation between IFG activation and memory performance in the prefrontal cortex during retrieval [Tulving et al., 1999], this is the first report of an inverse correlation between activation during encoding conditions and memory performance. Schacter et al. [1996] also reported an inverse correlation between PFC activation and memory performance, interpreting the PFC activation as a reflection of retrieval attempt. In the present study, an inverse correlation was observed during the encoding phase when subjects were explicitly asked to remember the scenes. Our results suggest that subjects who performed poorly in the memory task may have tried harder to encode the stimuli than those who performed well. This is further supported by the fact that the magnitude of the inverse correlation was larger for the more complex, RSI scenes. Together, these findings provide further evidence for the involvement of the right IFG in strategically flawed encoding and retrieval effort.

It is possible that the inability of the present and several other studies [Maguire et al., 1996] to relate HIPP and PHG activation to memory encoding is due to the use of blocked designs where several correctly and incorrectly encoded trials are averaged together. Using event‐related designs, Brewer et al. [1998] and Wagner et al. [1998] found that the magnitude of focal activation in the inferior prefrontal cortex and bilateral PHG predicted which stimuli were remembered well. Fernandez et al. [1998] found that bilateral activation in the posterior HIPP correlated with successful encoding of words. However, even in event‐related designs, the magnitude of signal change in the PHG that can be attributed to memory encoding appears to be less than 25% of the overall signal change during processing of complex outdoor scenes (see Fig. 3 in Brewer et al., 1998). The remaining part of the signal change appears to be driven by processes not directly related to memory encoding. Although memory encoding accounts for a small fraction of the variance of activation in the PHG, when the contribution of the right IFG was factored out, the right PHG was the only region that showed a positive partial correlation with memory performance. Thus, the present results provide support for the suggestion that the PHG is involved in memory encoding to some extent. However, this relation was found only for RSI scenes, suggesting that PHG activation related to memory encoding depends on the spatial features of the information processed.

Implications for higher‐order processing and encoding of visual stimuli

Both SI and novelty processing are initiated early in the visual stream prior to input into the PHG. Indeed, in terms of magnitude in signal change, the strongest effects of both these factors were observed in the LNG. However, several new features emerge downstream from the LNG. The key to understanding downstream processing is the manner in which novelty and SI processing interact in each structure. Novelty × Stimulus interaction was significant in the LNG but not any other region. In the LNG, the effect of novelty on RSI scenes was significantly greater than on PSI scenes. In all other ROIs, novelty affected RSI and PSI scenes identically. Thus, novelty effects were stimulus dependent in the LNG and stimulus independent in the PHG, HIPP, and IFG. The emergence of stimulus invariant novelty processing in the PHG suggests that visual stimuli are transformed to a different representation in the PHG from the one in the LNG. This may enable the brain to develop higher order representations unconstrained by irrelevant details of environmental stimuli. These results provide additional support for the hypothesis that the PHG and HIPP may code relational characteristics of the information being processed [Cohen et al., 1999].

Our results suggest greater NOVELTY × STIMULUS interaction effects in the PHG than the HIPP. Together, these findings provide the first evidence for a hierarchical independence in processing of novel stimuli. Novelty processing becomes increasingly distinct from spatial information processing at each stage of the network leading from the LNG, to the PHG, and then to the HIPP. This trend toward increased independence reaches its pinnacle in the IFG where not only is the effect of novelty independent of the level of SI, there is no effect of SI processing at all. These results may also explain why previous studies have variably reported activation in the PHG and HIPP during tasks that involved processing of complex novel visual scenes [Maguire et al., 1997, 1998a; Stern et al., 1996]. Overall signal levels in the PHG and HIPP were not significantly different in the present study. Nevertheless, significant differences between the PHG and HIPP emerge at the level of interaction between novelty and SI processing.

The present study sheds further light on the role of the hippocampal formation and PFC in memory encoding. First, compared to novelty detection and SI processing, memory encoding accounted for a small and nonsignificant proportion of the variance in activation in all structures. Second, activation in the right IFG was inversely correlated with memory performance. Third, a relation between memory performance and activation was observed in the right PHG only when activation in the right IFG was factored out. The present study found an inverse relation between right IFG activation and overall memory performance. This finding may reflect strategic differences between subjects during memory encoding. Imaging studies have shown that activation in this region is related to task difficulty and effort [Barch et al., 1997] and lesions to the IFG and adjoining orbitofrontal cortex are known to result in confabulation and incorrect memory retrieval [Fischer et al., 1995; Moscovitch and Melo, 1997]. We hypothesize that right IFG dysfunction at the encoding stage may be related to either greater effort by subjects with poor memory or strategically incorrect processes that interfere with correct memory encoding. Further research is needed to elucidate the neuropsychological processes, and their functional correlates, underlying differences in strategy between subjects for correctly and incorrectly recognized events [Tulving et al., 1999].

Acknowledgements

It is a pleasure to thank Christine Blasey for statistical consultation and editorial advice, John Gabrieli for useful discussion, and Ingrid Johnsrude for helpful comments on the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Aguirre GK, Zarahn E, D'Esposito M (1998): An area within human ventral cortex sensitive to “building” stimuli: evidence and implications. Neuron 21: 373–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amaral DG (1999): What is where in the medial temporal lobe? Hippocampus 9: 1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohbot VD, Kalina M, Stepankova K, Spackova N, Petrides M, Nadel L (1998): Spatial memory deficits in patients with lesions to the right hippocampus and to the right parahippocampal cortex. Neuropsychologia 36: 1217–1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer JB, Zhao Z, Desmond JE, Glover GH, Gabrieli JD (1998): Making memories: brain activity that predicts how well visual experience will be remembered. Science 281: 1185–1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner RL, Kelley WM, Petersen SE (1999): Frontal cortex contributes to human memory formation. Nat Neurosci 2: 311–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buzsaki G (1996): The hippocampo‐neocortical dialogue. Cereb Cortex 6: 81–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen NJ, Ryan J, Hunt C, Romine L, Wszalek T, Nash C (1999): Hippocampal system and declarative (relational) memory: summarizing the data from functional neuroimaging studies. Hippocampus 9: 83–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duvernoy H (1991): The human brain: surface, three‐dimensional sectional anatomy. New York: Springer‐Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Duvernoy HM (1998): The human hippocampus: functional anatomy, vascularization and serial sections with MRI. New York: Springer‐Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein R, Kanwisher N (1998): A cortical representation of the local visual environment. Nature 392: 598–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felleman DJ, Van Essen DC (1991): Distributed hierarchical processing in the primate cerebral cortex. Cereb Cortex 1: 1–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez G, Weyerts H, Schrader‐Bolsche M, Tendolkar I, Smid HG, Tempelmann C, Hinrichs H, Scheich H, Elger CE, Mangun GR, Heinze HJ (1998): Successful verbal encoding into episodic memory engages the posterior hippocampus: a parametrically analyzed functional magnetic resonance imaging study. J Neurosci 18: 1841–1847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer RS, Alexander MP, D'Esposito M, Otto R (1995): Neuropsychological and neuroanatomical correlates of confabulation. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 17: 20–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher PC, Frith CD, Rugg MD (1997): The functional neuroanatomy of episodic memory. Trends Neurosci 20: 213–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friston KJ, Worsley K, Poline J‐P, Frith CD, Frackowiak RSJ (1995): Statistical parametric maps in functional imaging: A general linear approach. Hum Brain Mapp 2: 189–210. [Google Scholar]

- Gabrieli JDE, Brewer JB, Desmond JE, Glover GH (1997): Separate neural bases of two fundamental memory processes in the human medial temporal lobe. Science 276: 264–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaffan D, Harrison S (1989): Place memory and scene memory: effects of fornix transection in the monkey. Exp Brain Res 74: 202–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glover GH, Lai S (1998): Self‐navigated spiral fMRI: interleaved versus single‐shot. Magn Res Med 39: 361–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habib M, Sirigu A (1987): Pure topographical disorientation: a definition and anatomical basis. Cortex 23: 73–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes C, Mathias C (1996): Improved brain coil for fMRI and high resolution imaging. Paper presented at the ISMRM 4th annual meeting proceedings, New York.

- Hochhaus L (1972): A table for the calculation of d' and β. Psychol Bull 77: 375–376. [Google Scholar]

- Johnsrude IS, Owen AM, Crane J, Milner B, Evans AC (1999): A cognitive activation study of memory for spatial relationships. Neuropsychologia 37: 829–841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kates WR, Abrams MT, Kaufmann WE, Breiter SN, Reiss AL (1997): Reliability and validity of MRI measurement of the amygdala and hippocampus in children with fragile X syndrome. Psychiatry Res 75: 31–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keppel G, Zedeck S (1989): Data analysis for research designs: analysis of variance and multiple regression correlation approaches. New York: W. H. Freeman. [Google Scholar]

- Lepage M, Habib R, Tulving E (1998): Hippocampal PET activations of memory encoding and retrieval: the HIPER model. Hippocampus 8: 313–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguire EA (1997): Hippocampal involvement in human topographical memory: evidence from functional imaging. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 352: 1475–1480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguire EA, Burgess N, Donnett JG, Frackowiak RS, Frith CD, O'Keefe J (1998a): Knowing where and getting there: a human navigation network. Science 280: 921–924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguire EA, Frackowiak RS, Frith CD (1996): Learning to find your way: a role for the human hippocampal formation. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 263: 1745–1750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguire EA, Frackowiak RSJ, Frith CD (1997): Recalling routes around London: activation of the right hippocampus in taxi drivers. J Neurosci 17: 7103–7110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguire EA, Frith CD, Burgess N, Donnett JG, O'Keefe J (1998b): Knowing where things are parahippocampal involvement in encoding object locations in virtual large‐scale space. J Cogn Neurosci 10: 61–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin A (1999): Automatic activation of the medial temporal lobe during encoding: lateralized influences of meaning and novelty. Hippocampus 9: 62–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milner B, Johnsrude I, Crane J (1997): Right medial temporal‐lobe contribution to object‐location memory. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 352: 1469–1474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montaldi D, Mayes AR, Barnes A, Pirie H, Hadley DM, Patterson J, Wyper DJ (1998): Associative encoding of pictures activates the medial temporal lobes. Hum Brain Mapp 6: 85–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moscovitch M, Melo B (1997): Strategic retrieval and the frontal lobes: evidence from confabulation and amnesia. Neuropsychologia 35: 1017–1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Keefe J, Burgess N, Donnett JG, Jeffery KJ, Maguire EA (1998): Place cells, navigational accuracy, and the human hippocampus. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 353: 1333–1340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono M, Kubik S, Abernathey CD (1990): Atlas of the cerebral sulci. Stuttgart: Thieme Medical Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Owen AM, Milner B, Petrides M, Evans AC (1996): Memory for object features versus memory for object location: a positron‐emission tomography study of encoding and retrieval processes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 93: 9212–9217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker A, Gaffan D (1998): Interaction of frontal and perirhinal cortices in visual object recognition memory in monkeys. Eur J Neurosci 10: 3044–3057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pigott S, Milner B (1993): Memory for different aspects of complex visual scenes after unilateral temporal‐ or frontal‐lobe resection. Neuropsychologia 31: 1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rombouts SA, Machielsen WC, Witter MP, Barkhof F, Lindeboom J, Scheltens P (1997): Visual association encoding activates the medial temporal lobe: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Hippocampus 7: 594–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schacter DL, Alpert NM, Savage CR, Rauch SL, Albert MS (1996): Conscious recollection and the human hippocampal formation: evidence from positron emission tomography. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 93: 321–325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schacter DL, Wagner AD (1999): Medial temporal lobe activations in fMRI and PET studies of episodic encoding and retrieval. Hippocampus 9: 7–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith ML, Milner B (1981): The role of the right hippocampus in the recall of spatial location. Neuropsychologia 19: 781– 793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith ML, Milner B (1989): Right hippocampal impairment in the recall of spatial location: encoding deficit or rapid forgetting? Neuropsychologia 27: 71–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Squire LR, Zola SM (1997): Amnesia, memory and brain systems. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 352: 1663–1673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern CE, Corkin S, Gonzalez RG, Guimaraes AR, Baker JR, Jennings PJ, Carr CA, Sugiura RM, Vedantham V, Rosen BR (1996): The hippocampal formation participates in novel picture encoding: evidence from functional magnetic resonance imaging. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 93: 8660–8665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talairach J, Tournoux P (1988): Co‐planar stereotaxic atlas of the human brain: 3‐dimensional proportional system: an approach to cerebral imaging. Rayport M , translator. New York: Thieme Medical Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Theodor LH (1972): A neglected parameter: some comments on “A table for the calculation of d′ and β″. Psychol Bull 78: 260–261. [Google Scholar]

- Tulving E, Habib R, Nyberg L, Lepage M, McIntosh AR (1999): Positron emission tomography correlations in and beyond medial temporal lobes. Hippocampus 9: 71–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tulving E, Markowitsch HJ, Craik FE, Habib R, Houle S (1996): Novelty and familiarity activations in PET studies of memory encoding and retrieval. Cereb Cortex 6: 71–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tulving E, Markowitsch HJ, Kapur S, Habib R, Houle S (1994): Novelty encoding networks in the human brain: positron emission tomography data. Neuroreport 5: 2525–2528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner AD, Poldrack RA, Eldridge LL, Desmond JE, Glover GH, Gabrieli JD (1998): Material‐specific lateralization of prefrontal activation during episodic encoding and retrieval. Neuroreport 9: 3711–3717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang JZ, Brown MW (1999): Differential neuronal responsiveness in primate perirhinal cortex and hippocampal formation during performance of a conditional visual discrimination task. Eur J Neurosci 11: 3715–3724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]