Abstract

Near infrared optical topography (OT) is the simultaneous acquisition of hemoglobin absorption from an array of optical fibers on the scalp to construct maps of cortical activity. We demonstrate that OT can be used to determine lateralization of prefrontal areas to a language task that has been validated by functional MRI (fMRI). Studies were performed on six subjects using a visually presented language task. Laterality was quantified by the relative number of activated pixels in each hemisphere for fMRI, and the total hemoglobin responses in each hemisphere for OT. All subjects showed varying degrees of left hemisphere language dominance and the mean laterality indices for subjects who underwent both OT and fMRI were in good agreement. These studies demonstrate that OT gives predictions of hemispheric dominance that are consistent with fMRI. Due to the ease of use and portable nature of OT, it is anticipated that optical topography will be valuable tool for neurological examinations of cognitive function. Hum. Brain Mapping 16:183–189, 2002. © 2002 Wiley‐Liss, Inc.

Keywords: near infrared spectroscopy, fMRI, epilepsy, Wada test

INTRODUCTION

Imaging techniques such as functional MRI (fMRI) have become an important tool in basic neuroscience, allowing investigation of a wide range of cognitive functions. One area of potential value is the use of non‐invasive imaging methods to obtain information about language lateralization and localization [Demonet et al., 1992] that is currently obtained by more invasive procedures such as the Wada test [Wada and Rasmussen, 1960] and direct electrical stimulation [Malow et al., 1996] of cerebral cortex. Desmond reported fMRI and Wada results in seven patients (three right hemisphere dominant) [Desmond et al., 1995]. Their fMRI task used visually presented words, and required a perceptual or semantic judgment about the objects. The resulting activation of the inferior frontal gyrus and neighboring cortex (BA 45, 46, and 47) during fMRI was concordant with the Wada result in all seven cases. Binder also reported a strong correlation between Wada test results and fMRI [Binder et al., 1996]. In their sample of 22 consecutive epilepsy patients, the correlation between Wada results and a fMRI single word activation task also suggested that language lateralization was a continuous, rather than a dichotomous, variable. Most recently our own group has shown excellent correspondences between fMRI, cortical stimulation, and Wada testing [Carpentier et al., 2001].

It has long been known that light is sensitive to hemoglobin concentration and oxygenation state in living tissue [Milliken, 1942]. In neuroscience applications, the imaging of reflected light as a measure of neural activity has widespread use in the investigation of functional architecture of the cortex [Frostig et al., 1990; Mayhew et al., 1998]. Transcranial near infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) allows the non invasive differentiation between tissues that possess different absorption or scatter and provides spectroscopic information on chromophore concentrations such as hemoglobin and cytochrome oxidase [Hebden and Delpy, 1997; Jobsis, 1977]. NIRS methods have been successfully employed to monitor global brain oxygenation changes associated with hypoxia [Cope and Delpy, 1988] and local hemoglobin oxygenation changes associated with neural activity [Chance et al., 1993; Hoshi et al., 1993; Kato et al., 1993; Maki et al., 1995; Obrig et al., 2000; Villringer et al., 1993]. Near infrared optical topography (OT) was proposed as a new method for visualizing brain activity by using an array of optical fibers to obtain a spatial map of absorption changes using reflected light from the cortical surface [Koizumi et al., 1999; Maki et al., 1995, 1996]. OT devices have been used to monitor spatio‐temporal blood volume and oxygenation changes in cortex during sensory stimulation [Maki et al., 1996], cognitive function [Koizumi et al., 1999], and epileptic seizures [Watanabe et al., 2000] and its facility can allow non‐invasive measurement of human brain function under a variety of conditions with little subject restriction. Watanabe et al. [1998] have shown good correlation between the OT predictions of language dominance and the Wada test in a population of epilepsy patients using a Japanese language task. In the case of control subjects the authors showed that there was good correlation between the laterality and subject handedness, however there was no independent validation of the result because the Wada test was not performed [Watanabe et al., 1998]. The purpose of the following study is to use OT to determine language lateralization in a control population using an English language task that has been used extensively in fMRI studies [Carpentier et al., 2001; Kang et al., 1999; Ni et al., 2000]. The accuracy of the optical technique to determine the laterality of the hemodynamic response will be compared to fMRI studies on the same subjects using the same task.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

The sample was composed of six healthy volunteers (1–6) without neurological impairment: four right‐handed males, one right‐handed female, and one left‐handed male. Ages ranged from 21–39 years. Subjects were recruited on a voluntary basis, and gave informed consent according to institutional guidelines. Studies received prior approval by the institutional human research review committee.

Tasks

Language tasks were designed that required visual comprehension and processing of syntactic and semantic dimensions to judge sentence accuracy. Half of the sentences contained either syntactic or semantic errors such as nonsense noun or nonsense verb associations (babies can fly, baby can crying, and half were well formed sentences. Further details on the stimuli are discussed elsewhere in the context of event related fMRI studies [Kang et al., 1999; Ni et al., 2000]. In current work the stimuli are grouped in a block design for comparison across modalities [Carpentier et al., 2001]. Subjects were required to respond via a button press if sentences (presented every 2.5 sec) were fully correct, or either semantically‐syntactically incorrect. One hundred sentences of three words (subject, verb, and complement) were presented visually. Words were matched for length and number of syllables.

Control tasks were designed to direct subjects' attention to the physical characteristics of nonlinguistic stimuli (a line decision task). It is known that a variety of general‐purpose nonlinguistic functional systems are activated during most language behaviors, and that an “automatic” processing of linguistic stimuli takes place at phonological and semantic levels regardless of the behavioral situation [Price et al., 1996]. Activation from motor systems, visual systems, auditory systems, short‐term memory systems, and attention‐arousal networks are minimized in this study because our nonlinguistic control baselines were designed to engage these general‐purpose nonlinguistic systems, and to accomplish this with minimal phonological and semantic “automatic” processing. The duration of each task block was 24 sec of control task and 24 sec of the language task. Data analysis was performed using the block design in which the average 24 sec linguistic stimulation period was compared to the average 24 sec block of line decision tasks. The individual responses within each block was not discriminated by task performance. It has been shown previously that in event related studies the detection of syntactic errors usually showed preferential left lateralization whereas detection of semantic errors gave right lateralization relative to a control reading condition. The visual language task in this study compared visually presented sentences against non linguistic cross‐match line decisions. It has been shown that in a block design the syntactic and semantic tasks both preferentially activate the language dominant hemisphere relative to the non linguistic line decision task. [Carpentier et al., 2001].

Optical Topography

Near infrared optical topography was performed using a 48‐channel spectrometer operating at 780 and 830 nm (Hitachi ETG‐100) that is capable of mapping 24 cortical regions simultaneously [Koizumi et al., 1999; Maki et al., 1995, 1996]. Total hemoglobin changes were mapped using two 6 cm × 6 cm arrays covering a portion of the left and right frontal hemispheres. Figure 1 shows the arrangement of the transmission (open circles) and detection (filled circles) fibers as two arrays placed on homologous bilateral areas of the skull. Fibers are mounted on a deformable plastic helmet that is fitted to the subject and held by adjustable straps. Each pair of adjacent transmission and detection fibers define a single optode unit. The 24 measurement positions shown correspond to the central zone of the light path between the transmission and detection fibers. This configuration allows sufficient light to penetrate the cerebral cortex while maintaining reasonable spatial discrimination. The exact optical pathlength of the light is not known, which limits the spatial resolution in this configuration to 3 cm. The depth sensitivity of optical topography is not quantified in the whole brain but previous studies have shown that the current optical system is sensitive to signal changes as deep as 1 cm in cortex [Kennan et al., 2000; Koizumi et al., 1999]. To obtain the optode signals simultaneously, each transmission fiber is frequency modulated, and the detected signals are passed through lock‐in amplifiers to avoid crosstalk. High temporal resolution (100 msec) is possible because simultaneous detection of frequency modulated laser signals does not require optical switching [Maki et al., 1995]. By measuring the optical absorption data at two wavelengths during stimulation the hemodynamic parameters can be determined for each optode position to generate a two dimensional map. This map is then interpolated to produce the final optical image. The interfiber spacing is ∼3 cm that is sufficient to ensure cerebral penetration of the light while maintaining good sensitivity for hemoglobin detection [Hebden and Delpy, 1997]. Further details of the experimental apparatus and procedure are given elsewhere [Maki et al., 1995; Watenabe et al., 2000]. From previous fMRI studies using the same visual language task it has been shown that language activation occurs largely in the inferior frontal (Broca area, posterior temporal (Wernicke area) and basal temporal language regions [Carpentier et al., 2001; Kang et al., 1999; Ni et al., 2000]. Based on anatomic MR images the optode array was mounted to cover the inferior frontal areas [Talairach and Tournoux, 1988]. This arrangement neglects posterior regions such as Wernicke area, but allows simultaneous bilateral detection in the more anterior regions.

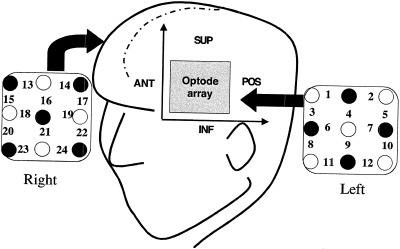

Figure 1.

Optode arrangement and positioning. Open circles denote light transmission fibers, filled circles denote detection fibers and numbers refer to the effective optode position for each fiber pairing. A dual hemisphere arrangement is used in which two 6 × 6 cm arrays are positioned on the head; posterior, anterior, superior, and inferior orientations are shown.

Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging

MR scanning was conducted at 1.5 T on a General Electric (Milwaukee, WI) Signa scanner. Sixteen coronal oblique slices (8 mm thick, 1 mm gap) were acquired, orthogonal to the Sylvian fissure. Functional imaging was performed using gradient‐echo‐EPI sequence (128 EPI images for each slice and for each run) with 50 msec echo time, 20 × 20 cm FOV and 64 × 64 matrix. Additional higher resolution T1‐weighted anatomical reference images were performed in the same region to provide anatomical localization (conventional spin echo imaging, FOV = 20 cm, matrix 256 × 192, 2 averages, TE/TR = 11/500 msec). Data were corrected for motion using SPM99 followed by a t‐test to detect activated voxels. All maps were thresholded at t > 1.5 (P uncorrected <0.01 determined using the bootstrap method [Efron and Tibshirani, 1993]. EPI data were analyzed with MatLab software using a Student's t‐test on a voxel‐by‐voxel basis.

FMRI Language Lateralization Scoring

The fMRI laterality index is given by [Carpentier et al., 2001],

| (1) |

where N denotes the number of MRI voxels (with t‐value > 1.5) in left (L) and right (R) hemispheres showing significant positive activation of the language task relative to the control task [Dapretto and Bookheimer, 1999; Carpentier et al., 2001; Kang et al., 1999]. Results range from −100 (right speech) to +100 (left speech). Statistical analyses to compare language laterality scores were performed using the Student's paired t‐test. For comparison with optical mapping, the laterality index was determined for the six most anterior slices, which correspond to the position of the optode arrays.

OT Language Lateralization Scoring

The nature of the BOLD fMRI signal is complex (it depends of blood flow, blood volume and metabolism changes as well as vessel orientation and size) [Kennan et al., 1994; Ogawa et al., 1993] therefore a statistical thresholding approach with pixel counting is used to determine laterality. This approach is not appropriate in OT because the spatial resolution is low (24 voxels in total). For optical topography we exploit the quantitative ability of the system to measure hemoglobin changes directly. The laterality index for OT is thus determined from the total hemoglobin changes in each hemisphere as,

| (2) |

where ΔCtotal denotes the total hemoglobin change in left (L) and right (R) hemispheres for all optodes that showed positive activation during the language task relative to the control task. Regions that deactivated during the language task were not included in the determination of language laterality.

RESULTS

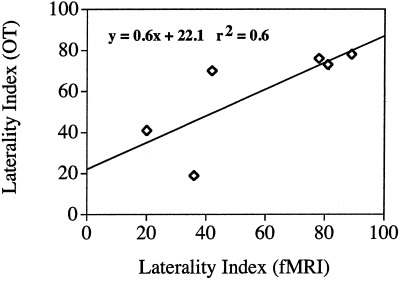

Figure 2 shows the fMRI activation for a single subject in the 6 most anterior imaging slices. These slices were chosen to span the area covered by the optical helmet. Figure 3a–c shows configuration of the OT helmet on a subject and the corresponding total hemoglobin response maps from the inferior frontal region overlaid on the brain surface for clarity. The registration was roughly determined by projection of the OT helmet onto the brain surface and is intended only for illustrative purposes. In both cases shown there is significantly greater positive response in the left hemisphere. In general, all subjects showed left hemisphere dominance to varying degrees as summarized in Table I. The areas of strongest hemoglobin responses were recorded in optodes 6, 7, and 8 of the left hemisphere. These are most likely associated with Broca area and pre motor cortex. Table I and Figure 4 show a comparison of fMRI and OT. As expected, there is good agreement across modalities. The closeness of the mean laterality indices is perhaps fortuitous but it is interesting to note that the degree of laterality response is qualitatively consistent across modalities with a reasonable correlation coefficient, r 2 = 0.6. In the three subjects with very strong lateralization in fMRI (LIfMRI > 80) there was also strong lateralization in the optical method (LIOT > 70) whereas in two of the subjects with the weakest fMRI lateralization (Subjects 1 and 6) the lateralization was weakest in OT. Subject 4 showed significantly stronger left lateralization in fMRI than in OT. Furthermore, the subjects who showed more posterior activation in fMRI also had more posterior activation in the optical method. Watanabe et al. [1998] showed that there was good correlation between laterality and subject handedness, which was observed in five of six cases in this study. In one case the subject (2) was left handed and still demonstrated left hemisphere language dominance in both the OT and fMRI studies. Although we unfortunately did not find any right hemisphere dominant subjects in this small sample population it is apparent that OT and fMRI give qualitatively similar predictions in magnitude and spatial distribution of hemodynamic response to the language stimuli.

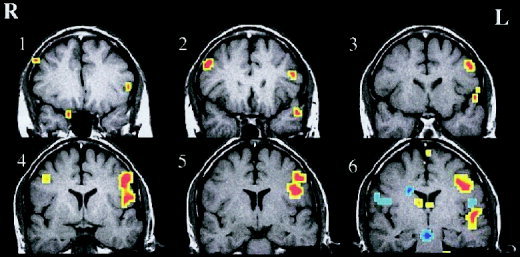

Figure 2.

FMRI activations (t > 1.5) for the six most anterior slices in a single subject (2). Red denotes regions of signal increases during the language task, blue denotes signal decreases.

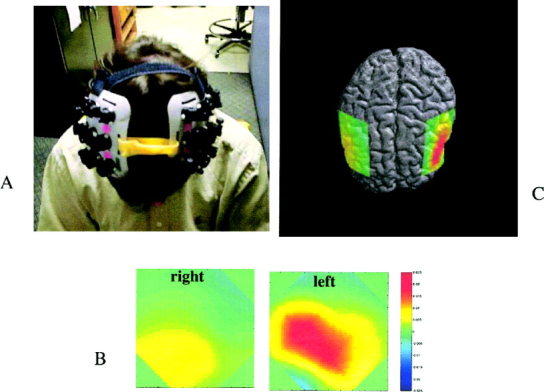

Figure 3.

a: Photograph of subject wearing OT helmet. b: OT maps from left and right hemisphere. c: Projection of OT total hemoglobin maps onto brain surface. Red regions denote increase in total hemoglobin.

Table I.

Laterality index, LI, as determined by fMRI and OT*

| Subject | LIfMRI | Max slice | LIOT | Max optode |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 36 | 4 | 19 | 6 |

| 2 | 89 | 4 | 78 | 6 |

| 3 | 78 | 3 | 76 | 7 |

| 4 | 42 | 1 | 70 | 8 |

| 5 | 81 | 4 | 73 | 6 |

| 6 | 20 | 2 | 41 | 8 |

| Average | 58 ± 28 | 59 ± 24 |

Four subjects. Max slice, slice position with most active pixels (relative to most posterior slice, Max optode, optode position with largest total Hb response.

Figure 4.

Correlation of laterality indices across modalities.

Our findings demonstrate that near infrared optical topography gives predictions of hemispheric dominance that are consistent with fMRI. It has been noted that there may be important differences between the determination of laterality by imaging methods and direct means such as the Wada test. In particular, direct methods determine the hemispheric systems which are crucial to language, whereas imaging methods identify all language related systems without necessarily determining those that are most important. To fully explore this question, further studies are needed that correlate specific regional differences in imaging to Wada test results. Given the excellent correlation observed between imaging and direct methods to date, there is good reason to expect that this problem will be solved. In future studies it may be necessary to extend OT mapping over larger cortical regions for the study language processing systems in both normal subjects and patient groups. This can easily be accomplished by using more optical fibers and hence larger optode arrays to map cognitive responses over a greater area.

A unique advantage of the optical system is that experiments can be performed under more natural conditions, which can provide considerable freedom in task design. Furthermore the studies can be performed quickly (the mean study time including setup was approximately 30 min) and without the need for specialized rooms. Therefore these methods are well suited to longitudinal studies, which could be extremely useful for staging brain response to therapy or training. Because the OT system is optically coupled to the subject it is possible to perform simultaneous measurements with other modalities such as EEG, which could provide source localization [Kennan et al., 2001]. To obtain precise spatial registration across modalities it will be necessary to use more advanced image processing techniques using models of light diffusion [Schweiger et al., 1999] to project the optical maps onto the brain surface. Another potential development is the use quantitative optical methods, which yield absolute hemoglobin and cytochrome‐oxidase changes during stimulation [Cooper et al., 1997] that can be directly compared across patient groups.

CONCLUSIONS

Near infrared optical topography gives predictions of hemispheric dominance in response to a language task that are consistent with fMRI. Although the spatial resolution and penetration depth of the optical method is limited by light absorption and scattering [Hebden and Delpy, 1997], this study clearly demonstrates that OT is sensitive enough to determine language lateralization that is comparable to more sophisticated and expensive imaging methods. The ability to utilize non‐invasive optical systems to map cognitive responses in an open environment should allow the development of more complex task designs. Given the system utility and ease of use, it is anticipated that optical topography will be valuable addition to neurological examinations as well as general studies of cognitive function.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Hitachi Medical Corporation for use of the ETG‐100 Optical Topography unit.

REFERENCES

- Binder JR, Swanson SJ, Hammeke TA, Morris GL, Mueller WM, Fischer M, Benbadis S, Frost JA, Rao SM, Haughton VM (1996): Determination of language dominance using functional MRI. Neurology 46: 978–984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpentier A, Pugh KR, Westervelt M, Studholme C, Skrinjar O, Thompson JL, Spencer DD, Constable RT (2001): Functional MRI of language processing: dependence on input modality and temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsia 42: 1241–1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chance B, Zhuang Z, Unah C, Alter C, Lipton L (1993): Cognition‐activated low frequency modulation of light absorption in human brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 90: 3770–3774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper CE, Cope M, Quaresima V., Ferrari M, Nemoto E, Springett R, Matcher S, Amess P, Penrice J, Tyszczuk L, Wyatt J, Delpy DT (1997): Measurement of cytochrome oxidase redox state by near infrared spectroscopy. Adv Exp Med Biol 413: 63–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cope M, Delpy DT (1988): System for long‐term measurement of cerebral blood and tissue oxygenation on newborn infants by near intra‐red transillumination. Med Biol Eng Comput 26: 289–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dapretto M, Bookheimer SY (1999): Form and content: dissociating syntax and semantics in sentence comprehension. Neuron 24: 427–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demonet JF, Chollet F, Ramsay S, Cardebat D, Nespoulous JL, Wise R, Rascol A, Frackowiak R (1992): The anatomy of phonological and semantic processing in normal subjects. Brain 115: 1753–1768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desmond JE, Sum JM, Wagner AD, Demb JB, Shear PK, Glover GH, Gabrieli JD, Morrell MJ (1995): Functional MRI measurement of language lateralization in Wada‐tested patients. Brain 118: 1411–1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efron B, Tibshirani RJ (1993): An introduction to the bootstrap. New York: Chapman and Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Frostig RD, Lieke EE, Ts'o DY, Grinwald A (1990): Cortical functional architecture and local coupling between neuronal activity and microcirculation revealed by in vivo high‐resolution optical imaging of intrinsic signals. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 87: 6082–6086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebden JC, Delpy DT (1997): Diagnostic imaging with light. Br J Radiol 70: S206–S214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoshi M, Tamura M (1993): Detection of dynamic changes in cerebral oxygenation coupled to neuronal function during mental work in man. Neurosci Lett 150: 5–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jobsis FF (1977): Noninvasive infrared monitoring of cerebral and myocardial oxygen sufficiency and circulatory parameters. Science 198: 1264–1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang AM, Constable RT, Gore JC, Avrutin S (1999): An event‐related fMRI study of implicit phrase‐level syntactic and semantic processing. NeuroImage 10: 555–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato T, Kamei A, Takashima S, Ozaki T (1993): Human visual cortical function during photic stimulation monitoring by means of near infrared spectroscopy. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 13: 516–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennan RP, Zhong J, Gore JC (1994): Intravascular susceptibility contrast mechanisms in tissue. Magn Reson Med 31: 9–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennan RP, Maki A, Yamamoto Y, Yamashita Y, Ochi H, Yamamoto T, Koizumi H (2000): Simultaneous mapping of sensorimotor cortex by fMRI and near IR optical topography (Abstract 857). International Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 8th Annual Meeting, Denver, Colorado.

- Koizumi H, Yamashita Y, Maki A, Yamamoto T, Ito Y, Itagaki H, Kennan R (1999): Higher order brain function analysis by transcranial dynamics near‐infrared spectroscopy imaging. J Biomed Opt 4: 403–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maki A, Yamashita Y, Ito Y, Watanabe E, Mayanagi Y, Koizumi H (1995): Spatial and temporal analysis of human motor activity using non‐invasive NIR topography. Med Phys 22: 1997–2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maki A, Yamashita Y, Watanabe E, Koizumi H (1996): Visualizing human motor activity by using non‐invasive optical topography. Front Med Biol Eng 7: 285–297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malow BA, Blaxton TA, Sato S, Bookheimer SY, Kufta CV, Figlozzi CM, Theodore WH (1996): Cortical stimulation elicits regional distinctions in auditory and visual naming. Epilepsia 37: 245–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayhew J, Zhao L, Hou Y, Berwick J, Askew S, Zheng Y, Coffey P (1998): Spectroscopic investigation of reflectance changes in the barrel cortex following whisker stimulation. Adv Exp Med Biol 454: 139–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milliken GA (1942): The oximeter, an instrument for measuring continuously the oxygen saturation of arterial blood in man. Rev Sci Instr 13: 434–444. [Google Scholar]

- Ni W, Constable RT, Mencl WE, Pugh KR, Fullbright RK, Shaywitz BA, Shaywitz SE, Gore JC, Shankweiler D. 2000. An event related neuroimaging study: distinguishing form and content in sentence processing. J Cogn Neurosci 12: 1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obrig H, Wenzel R, Kohl M, Horst S, Wobst P, Steinbrink J, Thomas F, Villringer A (2000): Near‐infrared spectroscopy: does it function in functional activation studies of the adult brain. Int J Psychophysiol 35: 125–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa S, Menon RS, Tank DW, Merkle H, Ellerman JM, Ugurbil K (1993): Functional brain mapping by blood oxygenation level dependent contrast magnetic resonance imaging, Biophys. J., 64, 803–812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price CJ, Wise RJS, Warburton EA, Moore CJ, Howard D, Patterson K, Frackowiak RSJ, Friston KJ (1996): Hearing and saying: the functional neuro‐anatomy of auditory word processing. Brain 119: 919–931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweiger M, Arridge SR (1999): Optical tomographic reconstruction in a complex head model using a priori region boundary information. Phys Med Biol 44: 2703–2721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talairach J, Tournoux P (1988): Referentially oriented cerebral MRI anatomy: atlas of stereotaxic anatomical correlations for gray and white matter. New York: Thieme. [Google Scholar]

- Villringer A, Planck J, Hock C, Schleinkofer L, Dirnagl U (1993): Near infrared spectroscopy (NIRS): a new tool to study hemodynamic changes during activation of brain function in human adults. Neurosci Lett 154: 101–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wada J, Rasmussen T (1960): Intracarotid injection of sodium Amytal for the lateralization of speech dominance: experimental and clinical observations. J Neurosurg 17: 266–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe E, Maki A, Kawaguchi F, Yamashita Y, Koizumi H, Mayanagi Y (1998): Non‐ invasive assessment of language dominance with near‐infrared spectroscopic mapping. Neurosci Lett 256: 49–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe E, Maki A, Kawaguchi F, Yamashita Y, Koizumi H, Mayanagi Y (2000): Non‐ invasive cerebral blood volume measurement during seizures using multichannel near infrared spectroscopic topography. J Biomed Opt 5: 287–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]