Abstract

The level of familiarity of a given stimulus plays an important role in memory processing. Indeed, the novelty/familiarity of learned material has been proven to affect the pattern of activations during recognition memory tasks. We used visually presented words to investigate the neural basis of recognition memory for relatively novel and familiar stimuli in schizophrenia. Subjects were 34 healthy volunteers and 19 schizophrenia spectrum patients. Two experimental cognitive conditions were used: 1 week and again 1 day prior to the PET imaging subjects had to thoroughly learn a list of 18 words (well‐learned memory). Subjects were also asked to learn another set of 18 words presented 1 min before the PET experiment (novel memory). During the PET session, subjects had to recognize the list of 18 words among 22 new (distractor) words. Subjects also performed a control task (reading words). A nonparametric randomization test and a statistical t‐mapping method were used to determine between‐ and within‐group differences. In patients the recognition of novel material produced relatively less flow in several frontal areas, superior temporal gyrus, insular cortex, and parahippocampal areas, and relatively higher activity in parietal areas, visual cortex, and cerebellum, compared to controls. No significant differences in flow were seen when comparing well‐learned memory activations between groups. These results suggest that different neural pathways are engaged during novel recognition memory in patients with schizophrenia compared to healthy individuals. During recognition of novel material, patients failed to activate frontal/limbic regions, recruiting a set of posterior perceptual brain regions instead. Hum. Brain Mapping 12:219–231, 2001. © 2001 Wiley‐Liss, Inc.

Keywords: schizophrenia, memory, recognition, limbic system, tomography, PET

INTRODUCTION

Since the first descriptions of the illness, cognitive abnormalities have been considered by many to be a fundamental trait of schizophrenia [Bleuler, 1950; Kraepelin, 1971; Saykin et al., 1991; Gold et al., 1992]. Based on a Bleulerian concept of schizophrenia emphasizing the importance of “thought disorder,” recent theories posit that the phenotype of schizophrenia can be defined by impairment in a fundamental cognitive process [Frith et al., 1988; Braff et al., 1993; Goldman‐Rakic, 1994; Andreasen et al., 1996]. This core cognitive abnormality would lead to a subsequent malfunction in one or several other cognitive processes (e.g., attention, memory, language, and emotion). If this model proves to be correct, a thorough investigation of neural substrates of cognitive domains in schizophrenia might provide relevant information about pathophysiological mechanisms of the illness.

The level of novelty/familiarity with a given stimulus plays an important role in memory processing. Whereas memory for novel stimuli may primarily activate neural mechanisms involved in the early stages of memory processing (i.e., encoding and effortful retrieval), well‐learned memory may instead more strongly activate neural systems used in later stages of memory processing (i.e., consolidation, storage, and less effortful retrieval) [Wiser et al., 2000]. Functional imaging studies have demonstrated that the novelty level of learned material affects the pattern and the size of brain activations engaged during memory tasks [Raichle et al., 1994; Andreasen et al., 1995a; Wiser et al., 2000]. A multinodal network including frontal subregions, limbic/paralimbic structures (i.e., anterior cingulate, insular cortex), parietal cortex, and cerebellum is involved in the processing of novel memory in healthy volunteers [Wiser et al., 2000]. It is of note that a disturbance of the complex functional interactions between the limbic/paralimbic system (i.e., medial temporal cortex, anterior cingulate, insula) and frontal regions has been hypothesized to be involved in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia [Seidman et al., 1991; Weinberger et al., 1992; Csernansky and Bardgett, 1998; Crespo‐Facorro et al., 2000a]. Furthermore, cognitive studies in schizophrenia have demonstrated deficiencies in the early stages of memory processing [Saccuzzo and Braff, 1981; Knight et al., 1985]. Heckers et al., [1999] reported differences between deficit and nondeficit syndrome patients with schizophrenia in frontal blood flow during memory retrieval tasks. When attempting to retrieve poorly encoded material the nondeficit group activated the left frontal lobe to a greater extent than did the deficit patients.

Using [15O] water positron emission tomography (PET), we have previously conducted a series of cognitive studies (e.g., recall memory of complex narratives or word lists, recognition memory of words) in order to examine the neural circuitry mediating different components of memory in healthy volunteers and schizophrenic patients [Andreasen et al., 1995b, 1995c, 1996; O'Leary et al., 1994; Wiser et al., 1998; Crespo‐Facorro et al., 1999; Kim et al., 1999]. These studies have consistently revealed dysfunction in a cortico‐cerebellar‐thalamic‐cortical circuit (CCTCC) in schizophrenia that appears to be involved in multiple cognitive processes [Andreasen et al., 1999]. The present study extends our investigation of the neural mechanisms underlying memory functions in schizophrenia by exploring the brain regions differentially involved in recognition memory for novel and well‐learned information. We hypothesize that patients with schizophrenia would show a different pattern of brain activations, reflecting a disturbance in fronto‐ cerebellar regions.

METHODS

Subjects

Subjects were 19 DSM‐IV schizophrenia spectrum patients (18 patients with schizophrenia and one patient with psychotic disorder not otherwise specified) and 34 healthy control subjects. The healthy volunteers were recruited by newspaper advertisement. They were screened to rule out psychiatric, neurological, or general medical illness by using a structured interview: a short version of the Comprehensive Assessment of Symptoms and History (CASH) [Andreasen et al., 1992a]. Twenty‐one were female, 13 were male, and all were right handed; their mean age was 26.3 (SD 7.8) and their mean educational achievement was 14.3 years (SD 1.8). The socioeconomic status (SES) of their parents (on a scale of 1–5) was 2.79 (SD 0.55).

Fourteen of the patients were male and 5 were female. Fifteen were right handed, 3 were left handed, and one was ambidextrous. Their mean age was 29.6 (SD 9.63) and their mean educational achievement was 13.1 years (SD 2.22). The SES of their parents was 3.05 (SD 0.71). Patients were either drug naive (n = 8) or had been medication free for 3 weeks before PET imaging (n = 11). Clinical symptoms were rated using the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS) [Andreasen, 1983] and the Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS) [Andreasen, 1984b]. These rating instruments were used to summarize psychopathology in three dimensions (negative, disorganized, and psychotic); mean negative symptom dimension score was 2.53 (SD 1.19), mean psychotic symptom dimension score was 2.55 (SD 1.43), and mean disorganized symptom dimension score was 1.26 (SD 1.24).

Subjects were matched as a group for age and educational achievement. All subjects gave written informed consent to a protocol approved by the Human Subjects Institutional Review Board of the University of Iowa.

Cognitive tasks

The experimental tasks consisted of two recognition memory conditions, long‐term or familiar and short‐term or novel verbal recognition memory for words. A control task consisting of reading words controlled for visual input and vocal output. For the task referred to as recognition of familiar words, 1 week prior to the PET experiment, subjects were taught to remember a list of 18 words in a single training session. Subjects were given successive study‐and‐test trials, with self‐paced item presentation on a video monitor, until they reached a perfect performance level. Subjects were not given instructions about learning strategies. In a test session provided on the day before the PET experiment, subjects were asked to recognize the 18 words by responding “yes” or “no” to indicate whether the word presented on the monitor had been previously learned or was one of the intermixed distractors. If they made any errors, they were exposed to the original lists until perfect recognition was again achieved. For the condition referred to as recognition of novel words, the subjects were instructed to remember a new list of 18 words, which were presented on a video monitor in a single session at a rate of one item every 2 sec; the last item was shown to the subjects 60 sec prior to the yes/no recognition test given during PET data acquisition. The novel and familiar conditions were identical except for the retention interval (1 min instead of 1 week) and the level of familiarity with the material (list seen once instead of thoroughly learned).

The recognition tasks were designed so that stimulation and output were as similar as possible across tasks during PET data acquisition; all stimuli were presented visually on a video monitor 12 inches above the nose of subject for 500 msec at 2.5 sec intervals. All target and distractor words consisted of one‐ or two‐syllable concrete nouns of comparable frequency of usage [Thorndike and Lorge, 1944] and were presented as black letters (0.5 inch high × maximum 2.5 inches long) on a light gray background. We chose not to counterbalance word lists across subjects with the result that all subjects received the same lists of novel and familiar words in the same order. The reading words baseline task consisted of reading aloud a new list of 40 common concrete English nouns of the same length and frequency as words used for the memory conditions. It was used to control articulatory motor activity and visual activation.

During the tasks, subjects were asked to respond with “yes” or “no” to indicate whether the word seen on the monitor was one of 18 targets learned previously or one of 22 intermixed distractors. To ensure that blood flow would be measured during an intense phase of the cognitive effort, the protocol was designed so that the proportion of targets was 80% during the 40‐sec acquisition time window centered on the arrival of the bolus of [15O] water in the brain [Hurtig et al., 1994]. The total duration of every task was 120 sec. The control task required the subjects to read the words out loud.

During the well‐learned condition the two groups did not differ significantly in the number of correct responses (rate of hits in controls was 17.5 (SD 0.92), which corresponds to 97.2% correct; rate of hits in patients was 16.2 (SD1.69), which corresponds to 90.0% correct; t = 1.86; P > .05). On the other hand, patients recognized significantly fewer words during the novel memory condition when compared to controls (rate of hits in controls was 80.5% (mean = 14.5 (SD 2.97)); rate of hits in patients was 64.4% (mean = 11.6 (SD 3.22)); t = 3.06; P < 0.001).

PET and MR data acquisition

The PET data were acquired with a bolus injection of 75 mCi of [15O] water in 5‐7 mL saline, using a GE 4096‐plus 15‐slice whole‐body scanner. Arterial blood sampling and imaging began at the time of tracer injection and continued for 100 sec (ten 10‐sec or twenty 5‐sec frames). The time from injection to bolus arrival in the brain was measured on each injection for each subject. Based on the time‐activity curves, the frames reflecting the 40 sec after bolus transit were summed [Hurtig et al., 1994]. The summed image was reconstructed into 2‐mm voxels in a 128 × 128 matrix by using the Butterworth filter (order = 6, cut‐off frequency = 0.35 Nyquist interval). Using the blood curve (expressed in PET counts) and an assumed brain/blood partition coefficient of 0.90, cerebral blood flow was calculated on a voxel‐by‐voxel basis by the autoradiographic method [Herscovitch et al., 1983]. Injections were repeated at approximately 15‐min intervals.

MR scans, to be used for anatomic localization of functional activity, were obtained for each subject with a standard T1‐weighted 3D SPGR sequence on a 1.5 Tesla GE Signa scanner (TE = 5 ms, TR = 24 ms, flip angle = 40°, NEX = 2, FOV = 26, matrix = 256 × 192, slice thickness = 1.5 mm).

Image analysis

The quantitative PET blood flow images and MR images were transferred to the Image Processing Laboratory of the University of Iowa Mental Health Clinical Research Center for analysis using the locally developed software package BRAINS (Brain Research: Analysis of Images, Networks, and Systems) [Andreasen et al., 1992b].

The outline of the brain is identified on the MR images by a combination of edge detection and manual tracing. MR scans are volume‐rendered; the anterior commissure‐posterior commissure (AC_PC) line is identified and used to realign the brains of all subjects to a standard position. The MR images from each group of subjects are averaged using a bounding box technique, so that the functional activity visualized by the PET studies can be localized on coregistered MR and PET images, where the MR image represents the “average brain” of the subjects in the study [Cizadlo et al., 1994]. The coregistered images are resampled into a 128 × 128 × 80 matrix and simultaneously visualized in all three orthogonal planes, thereby permitting 3D checking of anatomical localization of activity with a higher level of accuracy and detail than is provided by the Talairach atlas alone [Cizadlo et al., 1994].

Statistical analysis

A randomization analysis was used to conduct statistical tests to compare the two groups of subjects on the two experimental tasks. Randomization analysis is a nonparametric test, which is ideal for complex between‐group comparisons in PET studies because, unlike techniques that rely on the General Linear Model for between‐group comparison, it makes much fewer assumptions about the data [Arndt et al., 1996; Holmes et al., 1996]. In particular it is unaffected by the difference in variance across groups that often occurs in normal controls and patients with schizophrenia. The randomization analysis relies on comparisons across both tasks and groups and can therefore be difficult to interpret. It requires a double subtraction (novel minus well‐learned memory in patients) minus (novel minus well‐learned memory in controls). To assist in the interpretation of the randomization analysis we also analyzed the within–group (across cognitive tasks) differences. The within‐group comparisons of the reading words task subtracted from each of the two recognition memory conditions permits verification of the relative increases or decreases in flow, observed during the direct subtraction of the two memory tasks. Those statistical comparisons are established using the theory of Gaussian random fields developed by Worsley and colleagues [1992]. This technique corrects for the large number of voxel by voxel t‐tests performed, the lack of independence between voxels, and the resolution of the processed PET images. A within‐subject subtraction of relevant injections was performed followed by across subject averaging of the subtraction images and computation of voxel‐by‐voxel t‐tests of the rCBF changes. Significant regions of activation are calculated on the t‐map images. A t value of 3.61 was considered to be statistically significant (P < . 0005, one‐tailed, uncorrected). A size threshold was set at 50 contiguous voxels, in order to omit isolated outlying values.

RESULTS

Randomization analysis of novel and well‐learned recognition memory

This analysis revealed that patients had a relative decrease in blood flow, as compared to controls, bilaterally in ventral, lateral, and medial frontal regions, and also in the right superior temporal gyrus, the left insular cortex, the right putamen, and bilateral parahippocampal areas (Table I and Fig. 1). Relatively higher blood flow is distributed in superior parietal, striate and extrastriate, and bilateral cerebellar regions in patients (Table II and Fig. 1).

Table I.

Brain regions showing relatively lower blood flow in patients with schizophrenia, compared to healthy volunteers during novel recognition memory based on between‐group randomization analysis comparing the novel minus well‐learned subtraction in both groups

| Brain region (Brodmann Area)a | Tmax | Voxels | Talairach coordinates (mm) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x | y | z | |||

| R straight gyrus (BA14) | −4. 4481 | 497 | 7 | 40 | −28 |

| R orbitofrontal (BA11) | −5. 2310 | 1411 | 31 | 50 | −14 |

| L orbitofrontal (BA13) | −3. 3087 | 156 | −15 | 12 | −20 |

| L superior frontal (BA8) | −3. 6356 | 539 | −13 | 30 | 35 |

| R superior frontal (BA8) | −3. 6254 | 259 | 17 | 16 | 44 |

| R infer/middle frontal (BA46/10) | −2. 9411 | 129 | 27 | 45 | 3 |

| R/L rostral anterior cingulate (BA24/32) | −4. 9614 | 2553 | 6 | 42 | 20 |

| L precentral gyrus (BA6) | −3. 9310 | 414 | −27 | −5 | 42 |

| L insular cortex | −3. 4113 | 193 | −28 | 2 | −11 |

| R post superior temporal (BA22) | −3. 2776 | 162 | 44 | −32 | 6 |

| R inferior temporal (BA37) | −3. 1806 | 94 | 38 | −15 | −37 |

| R parahippocampal gyrus (BA20/37) | −3. 5024 | 186 | 33 | −25 | −28 |

| L parahippocampal gyrus (BA20) | −3. 1865 | 107 | −27 | −27 | −24 |

| R putamen | −3. 1530 | 58 | 20 | 7 | −3 |

L = left; R = right.

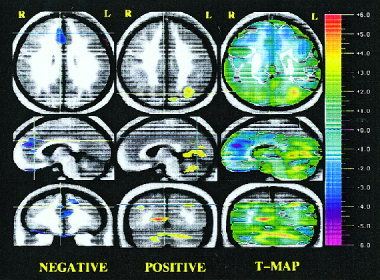

Figure 1.

Randomization analysis of novel recognition minus well‐learned subtraction in schizophrenia patients compared to healthy volunteers: Negative activations (left column), positive activations (middle column), and statistical t‐map of activations (right column). Three orthogonal views are shown: transaxial, sagittal, and coronal. Crosshairs are used to show the location of the slice. Statistical (randomization) maps of the PET data are superimposed on a composite magnetic resonance (MR) image derived by averaging the MR scans from the subjects. The “t‐map” (right column of the image) represents the value of t for all voxels in the image and shows the general geography of the activations. Color bar on the right shows the t statistic values. The “peak map” (left and middle columns of the image) provides a descriptive picture of areas where all contiguous voxels exceed negatively (left) and positively (middle), the predefined threshold for statistical significance. Orange and red colors portray a relative increase in blood flow; blue and purple colors portray a relative decrease in blood flow. On the left column, the slices were chosen to show several frontal areas (e.g., superior frontal gyrus, anterior cingulate, orbitofrontal cortex, and straight gyrus) with a relative decrease in flow during the novel memory. The crosshairs point to the right anterior cingulate. On the middle column, the view of the three planes indicates that blood flow in the parietal cortex, occipital cortex, and cerebellum was significantly higher in patients.

Table II.

Brain regions showing relatively higher blood flow in patients with schizophrenia, compared to healthy volunteers during novel recognition memory based on between‐group randomization analysis comparing the novel minus well‐learned subtraction in both groups

| Brain region (Brodmann area)a | Tmax | Voxels | Talairach coordinates (mm) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x | y | z | |||

| L posterior/middle temporal (BA21) | 2.914 | 75 | −50 | −40 | −3 |

| L superior parietal (BA7) | 4.209 | 461 | −29 | −70 | 34 |

| R superior parietal (BA19/7) | 3.567 | 230 | 35 | −75 | 28 |

| L fusiform gyrus (BA37) | 3.311 | 132 | −41 | −44 | −21 |

| R precuneus (BA31) | 3.136 | 127 | 4 | −62 | 23 |

| L cuneus (BA16) | 3.955 | 619 | −14 | −88 | 17 |

| R lingual gyrus (BA18/19) | 3.057 | 121 | 24 | −62 | −12 |

| R lingual gyrus (BA17/18) | 5.927 | 3394 | 13 | −70 | 7 |

| L cerebellum/tonsil | 3.451 | 406 | −6 | −51 | −40 |

| R superior cerebellum | 4.081 | 442 | 45 | −50 | −31 |

| L/R superior cerebellum | 4.458 | 3862 | −15 | −69 | −24 |

L = left; R = right.

Within‐group activations during novel recognition memory

Two t‐map analyses, novel memory minus well‐learned memory and novel memory minus reading words subtractions, were performed separately for the patient and control groups to analyze novel memory activations (novel minus well‐learned rCBF increases). Healthy volunteers showed a pattern of novel activations that exclusively encompasses frontal lobe areas: bilateral orbitofrontal cortex (OFC), left anterior cingulate, and bilateral insular cortex (Table III and Fig. 2). Instead, patients activated left parietal areas, bilateral visual cortex, and the left cerebellum. Overall, a lateralized pattern of positive activations encompassing predominantly left side areas was seen in patients. Smaller positive activations were also found in the left supplementary motor area (SMA) and right insular cortex. Additionally, relative decreases in blood flow were observed in the left inferior temporal gyrus, bilateral middle temporal gyrus, and the right cuneus in the control group during novel recognition memory. Patients with schizophrenia showed a relative decrease in flow in the right straight gyrus (SG) and the OFC (Table IV and Fig. 2).

Table III.

Within‐group analysis of novel minus well‐learned recognition memory in healthy volunteers and schizophrenic patients—positive t‐values*

| Healthy volunteers | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tmax | Voxels | Talairach coordinates (mm) | Brain region (BA)a | ||

| x | y | z | |||

| 7.746 | 1772 | 29 | 45 | −11 | R orbitofrontal (BA11) |

| 4.976 | 895 | −31 | 45 | −14 | L orbitofrontal (BA11) |

| 4.706 | 250 | −17 | 12 | −17 | L orbitofrontal (BA13) |

| 4.335 | 181 | 14 | 8 | −22 | R orbitofrontal (BA13) |

| 5.767 | 770 | −2 | 24 | 29 | L anterior cingulate (BA24) |

| 4.395 | 109 | −25 | −9 | 44 | L precentral gyrus (BA6) |

| 5.047 | 569 | 33 | 14 | 4 | R anterior insular cortex |

| 3.888 | 69 | −32 | 10 | −9 | L anterior insular cortex |

| Schizophrenic patients | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tmax | Voxels | Talairach coordinates (mm) | Brain region (BA)a | ||

| x | y | z | |||

| 4.333 | 93 | −5 | −13 | 52 | L SMA (BA6) |

| 3.988 | 59 | 30 | 23 | 0 | R anterior insular cortex |

| 5.898 | 823 | −3 | −76 | 43 | L parietal (BA7) |

| 5.708 | 676 | −36 | −70 | 46 | L superior parietal (BA40) |

| 5.361 | 232 | −49 | −32 | 49 | L postcent/parietal (BA2/40) |

| 4.577 | 188 | 11 | −69 | 7 | R cuneus (BA17/18) |

| 4.541 | 147 | −15 | −86 | 18 | L cuneus (BA18) |

| 4.744 | 619 | −26 | −70 | −29 | L cerebellum |

All of the regions in the had higher blood flow in the novel than in the well‐learned condition. All of these regions also showed higher blood flow in the novel than in the reading baseline condition.

L = left; R = right; BA = Brodmann's areas.

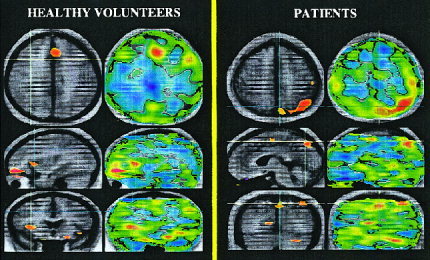

Figure 2.

Positive activations in healthy volunteers and patients with schizophrenia during novel memory activations (novel minus well‐learned increases in rCBF). (a) This figure shows the subtraction of novel minus well‐learned conditions in healthy volunteers. Regions in yellow/red tones indicate higher flow during the novel condition (novel memory activations). Novel activations encompass bilateral insular cortex, the orbitofrontal cortex, and the rostral anterior cingulate. (b) This figure shows the subtraction of novel minus well‐learned conditions in patients. Yellow/red tones indicate a relative increase in flow in patients during the novel condition (novel memory activations). The sagittal and coronal planes indicate a relative increase in flow in the SMA, left superior cerebellum, the right lingual gyrus, and the left parietal cortex.

Table IV.

Within‐group analysis of novel minus well‐learned recognition memory in healthy volunteers and schizophrenic patients—negative t‐values*

| Healthy volunteers | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tmax | Voxels | Talairach coordinates (mm) | Brain region (BA) | ||

| x | y | z | |||

| −4. 9109 | 304 | −38 | −42 | −19 | L fusiform gyrus (BA37) |

| −4. 7229 | 203 | −42 | −61 | 1 | L middle temporal (BA21) |

| −4. 1108 | 86 | 47 | −51 | 6 | R middle temporal (BA21/22) |

| −3. 9138 | 57 | 12 | −67 | 6 | R lingual/cuneus (BA17/18) |

| Schizophrenic patients | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tmax | Voxels | Talairach coordinates (mm) | Brain region (BA) | ||

| x | y | z | |||

| −4. 5845 | 264 | 6 | 47 | −29 | R straight gyrus (BA14) |

| −4. 6018 | 132 | 40 | 34 | −18 | R orbitofrontal (BA11) |

Negative t‐values during novel recognition memory indicate brain regions that showed relatively higher blood flow in the well‐learned than in the novel condition.

a L = left; R = right; BA = Brodmann's areas.

Within‐group activations during well‐learned recognition memory

Two t‐map analyses, novel memory minus well‐learned memory and well‐learned memory minus reading words subtractions, were performed separately for the patient and control groups to analyze well‐learned activations (novel minus well‐learned rCBF decreases). In healthy individuals, brain areas with relatively higher activity during the well‐learned recognition condition were located in the left angular gyrus, the right superior parietal cortex, and bilateral posterior cingulate gyrus (retrosplenial section) (Table V). On the other hand, a striking lack of significant well‐learned activations was observed when the novel and the well‐learned condition were subtracted in patients. Nonetheless, the well‐learned memory minus reading words subtraction revealed a relative increase in posterior brain regions (parietal, occipital, and cerebellar regions) when recognizing well‐learned words. Interestingly, these brain regions represent a subset of those brain regions engaged during the novel memory condition (Table VI and Fig. 3).

Table V.

Within‐group positive activations during well‐learned recognition memory in healthy volunteers*

| Tmax | Voxels | Talairach coordinates (mm) | Brain region (BA)a | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x | y | z | |||

| −4. 6347 | 455 | −51 | −46 | 13 | L inferior parietal (BA39) |

| −6. 3594 | 448 | 49 | −40 | 51 | R superior parietal (BA40) |

| −4. 5130 | 384 | 1 | −55 | 23 | R/L post cingulate (BA23/30) |

Positive activations during well‐learned recognition memory correspond to brain regions that showed a relative decrease in blood flow in the novel minus well‐learned subtraction, which also showed a relative increase in blood flow in the well–learned minus reading subtraction.

L = left; R = right; BA = Brodmann's areas.

Table VI.

Brain regions showing a relative increase in blood flow in the well‐learned minus reading subtraction and in the novel minus reading subtraction in patients with schizophrenia

| Well‐learned minus reading | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tmax | Voxels | Talairach coordinates (mm) | Brain region (BA)a | ||

| x | y | z | |||

| 4.857 | 488 | 41 | −54 | −36 | R superior parietal (BA40) |

| 4.808 | 384 | 7 | −70 | 49 | R precuneus (BA31) |

| 4.684 | 157 | 46 | −47 | −27 | R superior cerebellum |

| Novel minus reading | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tmax | Voxels | Talairach coordinates (mm) | Brain region (BA)a | ||

| x | y | z | |||

| 5.348 | 1076 | 31 | 34 | −9 | R anterior insular cortex |

| 4.629 | 690 | 40 | −52 | 39 | R superior parietal (BA40) |

| 5.280 | 947 | 0 | −75 | 37 | R/L precuneus (BA31) |

| 4.633 | 495 | 7 | −70 | 9 | R cuneus (BA17/18) |

| 5.685 | 575 | 46 | −50 | −29 | R superior cerebellum |

| 3.943 | 58 | −27 | −63 | −30 | L cerebellum |

L = left; R = right; BA = Brodmann's areas.

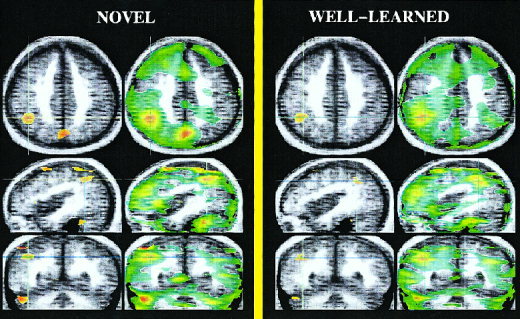

Figure 3.

Positive activations during the novel condition (left) and during the well‐learned condition (right) compared to a reading task in patients with schizophrenia. Brain regions activated by patients with schizophrenia during the novel condition are shown on the left figure. Patients showed an increase in flow in the superior cerebellum, the occipital and the parietal cortex when novel and reading words conditions are subtracted. Interestingly, patients display a similar subset of brain activations when well‐learned and reading words are subtracted. However, smaller activation sizes were observed in the well‐learned minus reading subtraction compared to those found in the novel‐reading subtraction.

DISCUSSION

This study examined the neural correlates of recognition memory for relatively novel and well‐learned words in individuals with schizophrenia. Patients with schizophrenia showed impairment in novel memory performance that was associated with a failure to engage frontal and limbic/paralimbic (i.e., cingulate, insula, parahippocampo) regions. Instead, a set of compensatory brain regions encompassing posterior perceptual areas was activated.

Patients with schizophrenia failed to activate several frontal regions, mainly orbitomedial regions, when they attempted to recognize newly encoded verbal material. A pattern of widely distributed activations in the frontal lobes has been demonstrated during novel recognition memory in healthy individuals [McIntosh et al., 1996; Kim et al., 1999; Wiser et al., 2000]. These studies have pointed out that ventral/inferior subregions of the prefrontal cortex are particularly involved in novel memory. Lesion studies in monkeys have demonstrated the participation of the OFC in the retention of a newly encoded stimulus [Meunier et al., 1997]. Interestingly, the OFC plays a critical role in neural processes that allow for adaptations to shifting context or stimulus contingencies [Nobre et al., 1999]. Our previous PET work has consistently shown lower activity in the dorsolateral and ventral prefrontal regions both at rest and when performing different cognitive tasks in patients with schizophrenia [Andreasen et al., 1997; Crespo‐Facorro et al., 1999]. Structural abnormalities in orbitomedial regions (i.e., OFC and straight gyrus) have been demonstrated in first‐episode patients with schizophrenia [Crespo‐Facorro et al., 2000a]. Our results herein provide new evidence to implicate ventral prefrontal regions in neural mechanisms underlying the pathophysiology of the illness.

Relatively lower blood flow was also found in the anterior cingulate in patients compared to healthy volunteers during the novel memory task (see Table I). It has also been proposed that, in combination with the OFC, the anterior cingulate may contribute to the recognition of newly learned material [Meunier et al., 1997]. On the other hand, the role of the anterior cingulate in emotional and attentional mechanisms has been consistently described [Mesulam, 1981; Paus et al., 1998]. Healthy individuals showed increased activation in the anterior cingulate cortex during the performance of novel tasks that require higher attentional demand [Andreasen et al., 1995c; Paus et al., 1993; McIntosh et al., 1996; Wiser et al., 2000]. Lower than normal activity in the anterior cingulate has been reported in patients with schizophrenia during several cognitive tasks [Cullum et al., 1993; Dolan et al., 1995; Carter et al, 1997; Crespo‐Facorro et al., 1999]. The lack of anterior cingulate activation in schizophrenia may reflect an inability to activate relevant regions of an “attentional system” when attentional demands are high.

Patients also showed relatively lower flow in the insular cortex during the recognition of novel verbal material. The insula is a major component of the limbic brain [Yakovlev, 1948] and is highly connected to subcortical and cortical regions involved in memory functions (i.e., entorhinal cortex) [Mesulam and Mufson, 1982; Insausti et al., 1987]. It is a multimodal sensory integration region that is involved in semantic encoding, short‐term storage of auditory‐verbal material, and internal phonological processing of written words [Paulesu et al., 1993; Augustine, 1996; Abdullaev and Posner, 1998]. Likewise, the right insular cortex has been implicated in the process of recognizing novel nonverbal material [Wiser et al., 2000]. The lack of activation in the insula in patients with schizophrenia is consistent with previous studies that have shown functional and structural abnormalities in the insular cortex in schizophrenia [Curtis et al., 1998; Crespo‐Facorro et al., 2000]. The observed small activation in the putamen strengthens the large body of evidence showing abnormalities in the basal ganglia and their connections with cortical areas in schizophrenia [Busatto and Kerwin, 1997].

Relatively lower flow was also seen bilaterally in posterior parahippocampal areas in patients. Parahippocampal cortices are higher‐order polymodal associational areas that contribute importantly to normal visual memory function [Suzuki et al, 1993]. The left parahippocampal gyrus appears to be specifically engaged during encoding experiences that are later well remembered [Brewer et al., 1998; Wagner et al., 1998]. Based on studies of novelty detection, Tulving et al. [1996] proposed that the hippocampal region plays a role in retrieving relevant stored information in order to recognize novel information. Our results herein suggest that the bilateral lack of activation in the parahippocampal region during novel‐memory task in schizophrenia may reflect a failure in the complex interactions between encoding and retrieval required to accurately recognize newly encoded information. Structural and functional abnormalities in the hippocampal/parahippocampal region have been demonstrated in schizophrenia [Nelson et al., 1998; Heckers, 1999].

In addition to brain areas with relatively lower blood flow, patients displayed a relative increase in flow in the superior parietal cortex, striate and extrastriate areas, and the cerebellum during novel memory. Increases in blood flow may be interpreted as compensatory brain regions recruited to accomplish a given cognitive function in patients. Impairment in cognitive performance may arise from the engagement of those nonspecialized systems to perform cognitive tasks. Indeed, in our study, patients showed a marked inability to recognize newly learned material as compared to controls. It is of note that healthy volunteers, in addition to fronto‐limbic activations, also engaged parietal, visual association, and cerebellar areas when recognizing novel nonverbal material [Wiser et al., 2000]. Posterior activations in perception and association cortical areas during novel recognition tasks have been related to perceptual components of visual information processing [McIntosh et al., 1996; Wiser et al., 2000]. Activations in extrastriate regions of the occipital lobe have been associated with visual presentation of words [Petersen et al., 1990]. We hypothesize that because of an inability to utilize refined and elaborate cognitive networks comprised of frontal and limbic regions, schizophrenic patients tend to recruit more perceptual neural mechanisms to recognize verbal material. This hypothesis is compatible with cognitive studies showing that patients with schizophrenia exhibit a selective impairment of elaborative processing of novel information, whereas automatic perceptual priming is spared [Gras‐Vincendon et al., 1994; Huron et al., 1995]. It is noteworthy that an increase in flow in the bilateral posterior parietal cortex (BA40) has also been found in patients with intact memory in graded memory studies [Fletcher et al., 1998].

The abnormality in cerebellar blood flow in schizophrenia was an expected finding. Based on our previous PET work, we have proposed that “cognitive dysmetria” is the primary mental impairment in schizophrenia. This model posits that a dysfunction in the normal connectivity in cortico‐cerebellar circuits may lead to a malfunction in the sequencing or timing component of normal cognition [Andreasen et al., 1996]. The cerebellum has been demonstrated to play a key role coordinating higher cognitive processes by updating feedforward commands to the frontal cortex via dentatothalamic projections [Schmahmann and Pandya, 1995; Desmond et al., 1997]. Cerebellar hyperfunction may reflect an attempt to compensate for a hypofunction or dysfunction in any other node of cortico‐cerebellar feedback loops. Previous functional studies of our group have provided strong support for the idea that the cerebellum plays a crucial role in the neural mechanisms involved in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia [Andreasen et al., 1996; Wiser et al., 1998; Crespo‐Facorro et al., 1999]. These previous studies have usually shown lower activity in the cerebellum when performing cognitive tasks and an increase in flow at rest. Further investigations are required to map the functions of the cerebellum in cognition and its role in schizophrenia.

The within‐group analysis revealed a relative increase in flow in the left angular gyrus, the right superior parietal, and bilateral posterior cingulate (retrosplenium) during the well‐learned memory task in healthy volunteers (see Table V). Posterior midline cortical regions (including posterior cingulate, retrosplenial, precuneus, and cuneus), the parietal cortex, and the cerebellum have been consistently activated during retrieval of well‐learned verbal material [Shallice et al., 1994; Kapur et al., 1995; Moscovitch et al., 1995]. On the other hand, the within‐group analysis (well‐learned minus reading) showed relatively higher flow in the right superior parietal cortex, precuneus, and superior cerebellum during the well‐learned memory task in patients (see Table VI). However, when the novel minus well‐learned subtraction was analyzed, no regions with higher flow in the well‐learned condition were found in patients. Intriguingly, the analysis of the well‐learned minus reading and the novel minus reading subtractions revealed that a similar subset of brain regions were activated during the novel and the well‐learned conditions in patients (see Table VI and Fig. 3). Consequently, no positive well‐learned activations were seen after directly subtracting the novel and the well‐learned tasks. However, brain regions activated during the performance of well‐learned tasks were smaller in size than novel activations. Smaller activations during the well‐learned condition could be explained based on the fact that long‐term memory tasks have shown the reduction in size of activations, as automatic processing occurs more efficiently [Raichle et al., 1994; Andreasen et al., 1995a]. Taken collectively, our results suggest that patients seem to accurately recognize well‐learned verbal material and that to accomplish this cognitive task they recruit a similar set of brain regions, as do healthy volunteers.

Limitations of the present study

Differences between patients and controls in the pattern of brain activation are always difficult to interpret when there are substantial between‐group differences in behavioral performance. Because patients often perform more poorly on cognitive tasks, as they did in the novel condition, it has been debated whether observed differences in rCBF and task performance could simply be caused by poor motivation and cooperation. Nonetheless, the lack of performance differences between patients and controls when recognizing the well‐learned list of words make it unlikely that differences in brain activation patterns are the result of patients failing to engage in the task. Therefore, rCBF and performance differences found in the novel condition may reflect a disturbance in brain mechanisms involved in the accomplishment of this particular cognitive task.

A second factor that complicates the interpretation of the present findings relates to differences in handedness and gender in the patient and control groups. The group of 19 patients included 4 with left‐ or mixed handedness, whereas all of the controls were right‐handed. Additionally, the patient group included a higher percentage of male subjects than did the control group. The relatively large number of right‐handed schizophrenic subjects in the study suggests that differences in rCBF due to handedness are likely to be relatively minor. Nevertheless, conclusions concerning the laterality of between‐group findings should be made cautiously. Differences in the gender composition of the patient and control group also suggest that the findings be interpreted with caution, although there is little or no basis in the literature to expect gender differences in rCBF during recognition of novel words.

CONCLUSION

In summary, patients with schizophrenia compared to healthy volunteers appear to have a redistribution of brain activations with lower than normal activity in frontal/limbic regions and higher activity in posterior perceptual processing areas when recognizing novel words. We speculate that this shift in the pattern of brain activations in schizophrenia could be understood in terms of an inability to accurately activate “higher” brain systems during a challenging novel recognition memory task, with a compensatory recruitment of less “sophisticated” cognitive routes comprised of perceptual posterior brain areas. However, cognitive deficits may arise from the engagement of those nonspecialized systems. Our results support the concept of disrupted neural systems in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia and provide new information about the increasingly important role of the cerebellum and its connections with the frontal cortex in schizophrenia. These new data enhance our capacity to comprehend the brain mechanisms underlying cognitive processes in schizophrenia and, therefore, constitute a step forward toward identification of a fundamental cognitive deficit that arises from abnormalities in particular neural systems and defines the phenotype of the illness.

Acknowledgements

This study was performed at the University of Iowa, Iowa City, Iowa. Grant sponsor: National Institute of Mental Health.

REFERENCES

- Abdullaev YG, Posner MI (1998): Event‐related brain potential imaging of semantic encoding during processing single words. Neuroimage 7: 1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen NC (1983): Scale for the assessment of negative symptoms (SANS). Iowa City, University of Iowa.

- Andreasen NC (1984): Scale for the assessment of positive symptoms (SAPS). Iowa City, University of Iowa.

- Andreasen NC, Flaum M, Arndt S (1992a): The Comprehensive Assessment of Symptoms and History (CASH). An instrument for assessing diagnosis and psychopathology. Arch Gen Psychiatry 49: 615–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen NC, Cohen G, Harris G, Cizadlo T, Parkkinen J, Rezai K, Swayze VW (1992b): Image processing for the study of brain structure and function: problems and programs. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 4: 125–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen NC, O'Leary D, Arndt S, Cizadlo T, Hurtig R, Rezai K, Watkins GL, Boles Ponto L, Hichwa RD (1995a): Short‐term and long‐term verbal memory: a positron emission tomography study. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 92: 5111–5115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen NC, O'Leary DS, Arndt S, Cizadlo T, Rezai K, Watkins GL, Boles Ponto LL, Hichwa RD (1995b): PET studies of memory: novel and practiced free recall of complex narratives. Neuroimage 2: 284–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen NC, O'Leary DS, Cizadlo T, Arndt S, Rezai K, Watkins GL, Boles Ponto LL, Hichwa RD (1995c): PET studies of memory: novel versus practiced free recall of word list. Neuroimage 2: 296–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen NC, O'Leary DS, Cizadlo T, Arndt S, Rezai K, Boles Ponto LL, Watkins GL, Hichwa RD (1996): Schizophrenia and cognitive dysmetria: a positron‐emission tomography study of dysfunctional prefrontal‐thalamic‐cerebellar circuitry. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93: 9985–9990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen NC, O'Leary DS, Flaum M, Nopoulos P, Watkins GL, Boles Ponto LL, Hichwa RD (1997): Hypofrontality in schizophrenia: distributed dysfunctional circuits in neuroleptic‐naive patients. Lancet 349: 1730–1734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen NC (1999): A unitary model of schizophrenia: Bleuler's “fragmented phrene” as schizencephaly. Arch Gen Psychiatry 56: 781–787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arndt S, Cizadlo T, Andreasen NC, Heckel D, Gold S, O'Leary DS (1996): Tests for comparing images based on randomization and permutation methods. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 16: 1271–1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Augustine JR (1996): Circuitry and functional aspects of the insular lobe in primates including humans. Brain Res Rev 22: 229–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleuler E (1950): Dementia praecox of the group of schizophrenias. Zinkin J, translator. New York: International Universities Press. [Google Scholar]

- Braff DL (1993): Information processing and attention dysfunctions in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 19: 233–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer JB, Zhao Z, Desmond JE, Glover GH, Gabrieli JDE (1998): Making memories: brain activity that predicts how well visual experience will be remembered. Science 281: 1185–1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busatto GF, Kerwin RW (1997): Schizophrenia, psychosis, and basal ganglia. Psychiatr Clin North Am 20: 897–910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter CS, Mintun M, Nichols T, Cohen JD (1997): Anterior cingulate gyrus dysfunction and selective attention deficits in schizophrenia: [15O] H2O PET study during single‐trial Stroop task performance. Am J Psychiatry 154: 1670–1675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cizadlo T, Andreasen NC, Zeien G, Rajarethinam R, Harris G, O'Leary DS, Swayze V, Arndt S, Hichwa R, Ehrhardt J, Yuh TC (1994): Image registration issues in the analysis of multiple‐injection [15O] H2O PET studies: BRAINFIT. Int Soc Opt Eng 2168: 423–4430. [Google Scholar]

- Crespo‐Facorro B, Paradiso S, Andreasen NC, O'Leary DS, Watkins GL, Boles Ponto L, Hichwa RD (1999): Recalling word list reveals a “cognitive dysmetria” in schizophrenic patients: a PET study. Am J Psychiatry 156: 386–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crespo‐Facorro B, Kim JJ, Andreasen NC, O'Leary D, Magnotta V (2000a): Regional frontal abnormalities in schizophrenia. A quantitative gray matter volume and cortical surface size study. Biol Psychiatry 48: 110‐119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crespo‐Facorro B, Kim JJ, Andreasen NC, O'Leary D, Bockholt J, Magnotta V (2000b): Insular cortex structural abnormalities in first‐episode schizophrenic patients. A regional quantitative gray matter volume and cortical surface size study. Schizophr Res (in press). [Google Scholar]

- Csernansky JG, Bardgett ME (1998): Limbic‐cortical neuronal damage and the pathophysiology of schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 24: 231–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullum CM, Harris JG, Waldo MC, Smernoff E, Madison A, Nagamoto HT, Griffith J, Adler LE, Freedman R (1993): Neurophysiological and neuropsychological evidence for attentional dysfunction in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 10: 131–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis VA, Bullmore ET, Brammer MJ, Wright IC, Williams SC, Morris RG, Sharma TS, Murray RM, McGuire PK (1998): Attenuated frontal activation during a verbal fluency task in patients with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 155: 1056–1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desmond JE, Gabrieli JDE, Wagner AD, Ginier BL, Glover GH (1997): Lobular patterns of cerebellar activation in verbal working‐memory and finger‐tapping tasks revealed by functional MRI. J Neurosci 17: 9675–9685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolan RJ, Fletcher P, Frith CD, Friston KJ, Frackowiack RS, Grasby PM (1995): Dopaminergic modulation of impaired cognitive activation in the anterior cingulate cortex in schizophrenia. Nature 378: 180–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher PC, McKenna PJ, Frith CD, Grasby PM, Friston KJ, Dolan RJ (1998): Brain activations in schizophrenia during a graded memory task studied with functional neuroimaging. Arch Gen Psychiatry 55: 1001–1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frith CD, Done DJ (1988): Towards a neuropsychology of schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry 153: 437–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold JM, Randolph C, Carpenter CJ, Goldberg TE, Weinberger DR (1992): Forms of memory failure in schizophrenia. J Abnorm Psychol 101: 487–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman‐Rakic PS (1994): Working memory dysfunction in schizophrenia. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 6: 348–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gras‐Vincendon A, Danion JM, Grange D, Bilik M, Willard‐Schroeder D, Sichel JP, Singer L (1994): Explicit memory, repetition priming and cognitive skill learning in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 13: 117–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckers S, Goff D, Schacter DL, Savage CR, Fischman AJ, Alpert NM, Rauch SL (1999): Functional imaging of memory retrieval in deficit vs nondeficit schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 56: 1117–1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herscovitch P, Markham J, Raichle ME (1983): Brain blood flow measured with intravenous [15O] H2O. I. Theory and error analysis. J Nucl Med 24: 782–789. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes AP, Blair RC, Watson JDG, Ford I (1996): Nonparametric analysis of statistics images from functional mapping experiments. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 16: 7–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huron C, Danion JM, Giacomoni F, Grange D, Robert P, Rizzo L (1995): Impairment of recognition memory with, but not without, conscious recollection in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 152: 1737–1742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurtig RR, Hichwa RD, O'Leary DS, Boles LL, Narayana S, Watkins GL, Andreasen NC (1994): The effects of timing and duration of cognitive activation in [15O] water PET studies. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 14: 423–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Insausti R, Amaral DG, Cowan WM (1987): The entorhinal cortex of the monkey: II. Cortical afferents. J Comp Neurol 264: 356–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapur S, Craik FIM, Jones C, Brown GH, Houle S, Tulving E (1995): Functional roles of prefrontal cortex in retrieval of memories: A PET study. Neuroreport 6: 1880–1884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JJ, Andreasen NC, O'Leary DS, Wiser AK, Boles‐Ponto LL, Watkins GL, Hichwa RD (1999): Direct comparison of the neural substrates of recognition memory for words and for faces. Brain 122: 1069–1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight RA, Elliott DS, Freedman EG (1985): Short‐term visual memory in schizophrenics. J Abnorm Psychol 94: 427–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraepelin E (1971): Dementia praecox and paraphrenia (1919). Barclay RM, translator; Robertson GM, editor. New York: Robert E. Krieger. [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh AR, Grady CL, Haxby JV, Ungerleider LG, Horwitz B (1996): Changes in limbic and prefrontal interactions in a working memory task for faces. Cereb Cortex 6: 571–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesulam MM (1981): A cortical network for directed attention and unilateral neglect. Ann Neurol 10: 309–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesulam MM, Mufson EJ (1982): Insula of the old world monkey. I: Architectonics in the insulo‐orbito‐temporal component of the paralimbic brain. J Comp Neurol 212: 1–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meunier M, Bachevalier J, Mishkin M (1997): Effects of orbitofrontal and anterior cingulate lesions on object and spatial memory in rhesus monkeys. Neuropsychologia 35: 999–1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moscovitch C, Kapur S, Kohler S, Houle S (1995): Distinct neural correlates of visual long‐term memory for spatial location and object identity: a positron emission tomography (PET) study in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 92: 3721–3725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson MD, Saykin AJ, Flashman LA, Riordan HJ (1998): Hippocampal volume reduction in schizophrenia as assessed by magnetic resonance imaging: a meta‐analytic study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 55: 433–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nobre AC, Coull JT, Frith CD, Mesulam MM (1999): Orbitofrontal cortex is activated during breaches of expectation in tasks of visual attention. Nature Neurosci 2: 11–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Leary DS, Andreasen NC, Hurting RR (1994): A PET study of regional cerebral blood flow during long‐ and short‐term verbal memory. Soc Neurosci Abstract 20: 1294. [Google Scholar]

- Paus T, Petrides M, Evans AC, Meyer E (1993): Role of the human anterior cingulate cortex in the control of oculomotor, manual, and speech responses: a positron emission tomography study. J Neurophysiol 70: 453–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paus T, Koski L, Caramanos Z, Westbury C (1998): Regional differences in the effects of task difficulty and motor output on blood flow response in the human anterior cingulate cortex: a review of 107 PET activation studies. Neuroreport 9: 37–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulesu E, Frith CD, Frackowiak RSJ (1993): The neural correlates of the verbal component of working memory. Nature 362: 342–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen SE, Fox PT, Snyder AZ, Raichle ME (1990): Activation of extrastriate and frontal cortical areas by visual words and word‐like stimuli. Science 249: 1041–1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raichle ME, Fiez JA, Videen TO, MacLeod AMK, Pardo JV, Fox PT, Petersen SE (1994): Practice‐related changes in human brain functional anatomy during nonmotor learning. Cereb Cortex 4: 8–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saccuzzo DP, Braff DL (1981): Early information processing deficit in schizophrenia: New findings using schizophrenic subgroups and manic control subjects. Arch Gen Psychiatry 38: 175–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saykin AJ, Gur RC, Gur RE, Mozley PD, Resnick SM, Kester DB, Stafiniak P (1991): Neuropsychological function in schizophrenia: selective impairment in memory and learning. Arch Gen Psychiatry 48: 618–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmahmann JD, Pandya DN (1995): Prefrontal cortex projections to the basilar pons: Implications for the cerebellar contribution to higher function. Neurosci Lett 199: 175–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidman LJ, Talbot NL, Kalinowski AG, McCarley RW, Faraone SV, Kremen WS, Pepple JR, Tsuang MT (1991): Neuropsycological probes of frontal‐limbic system dysfunction in schizophrenia. Olfactory identification and Wisconsin Card Sorting performance. Schizophr Res 6: 55–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shallice T, Fletcher P, Frith CD, Grasby P, Frackowiack RSJ, Dolan RJ (1994): Brain regions associated with acquisition and retrieval of verbal episodic memory. Nature 368: 633–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki WA, Zola‐Morgan S, Squire LR, Amaral DG (1993): Lesions of the perirhinal and parahippocampal cortices in the monkey produce long‐lasting memory impairment in the visual and tactual modalities. J Neurosci 13: 2430–2451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorndike EL, Lorge I (1944): The teacher's word book of 30,000 words. New York: Columbia Univiversity Teachers College, Bureau of Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Tulving E, Markowitsch HJ, Craik FIM, Habib R, Houle S (1996): Novelty and familiarity activations in PET studies of memory encoding and retrieval. Cereb Cortex 6: 71–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner AD, Schacter DL, Rotte M, Koutstaal W, Maril A, Dale AM, Rosen BR, Buckner RL (1998): Building momories: remembering and forgetting of verbal experiences as predicted by brain activity. Science 281: 1188–1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger DR, Berman KF, Suddath R, Torrey EF (1992): Evidence of dysfunction of a prefrontal‐limbic network in schizophrenia: a magnetic resonance imaging and regional cerebral blood flow study of discordant monozygotic twins. Am J Psychiatry 149: 890–897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiser AK, Andreasen NC, O'Leary DS, Watkins GL, Boles Ponto L, Hichwa RD (1998): Dysfunctional cortico‐cerebellar circuits cause “cognitive dysmetria” in schizophrenia. Neuroreport 9: 1895–1899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiser AK, Andreasen NC, O'Leary DS, Crespo‐Facorro B, Boles Ponto LL, Watkins GL, Hichwa R (2000): Novel versus well‐practiced memory for faces: a positron emission tomography study. J Cogn Neurosci 12: 1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worsley K, Evans A, Marret S, Neelin P (1992): A three‐dimensional statistical analysis for CBF activation studies in human brain. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 12: 900–918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yakovlev PI (1948): Motility, behavior and the brain. J Nerv Ment Dis 107: 313–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]