Abstract

Event‐related functional magnetic resonance imaging was used to investigate the localization of syntactic processing in sentence comprehension. Matched pairs of sentences containing identical lexical items were compared. One member of the pair consisted of a syntactically simpler sentence, containing a subject relativized clause. The second member of the pair consisted of a syntactically more complex sentence, containing an object relativized clause. Ten subjects made plausibility judgments about the sentences, which were presented one word at a time on a computer screen. There was an increase in BOLD hemodynamic signal in response to the presentation of all sentences compared to fixation in both right and left occipital cortex, the left perisylvian cortex, and the left premotor and motor areas. BOLD signal increased in the left angular gyrus when subjects processed the complex portion of syntactically more complex sentences. This study shows that a hemodynamic response associated with processing the syntactically complex portions of a sentence can be localized to one part of the dominant perisylvian association cortex. Hum. Brain Mapping 15:26–38, 2001. © 2001 Wiley‐Liss, Inc.

Keywords: localization of syntactic processing

INTRODUCTION

Syntactic structures are mental representations that constitute a basic feature of language. These structures allow the meanings of words to be related to one another to convey who is accomplishing or receiving an action, which adjectives are related to which nouns, and other “propositional” aspects of meaning. Understanding how the brain processes syntactic structures would shed light on a distinctly human cognitive capability.

There is very strong evidence from deficit‐lesion correlational studies that the assignment of syntactic form in sentence comprehension is largely carried out in the dominant perisylvian association cortex. Most of these studies have found deficits in this ability after lesions throughout this cortex and in association with all aphasic syndromes [Berndt et al., 1996; Caplan et al., 1985, 1996, 1997] suggesting that syntactic processing is based in a widely distributed neural net or is localized differently in different individuals. Some researchers have argued that one syntactic operation is affected solely by lesions in and around Broca's area [Grodzinsky, 2000; Swinney et al., 1996; Swinney and Zurif, 1995; Zurif et al., 1993]. This operation connects noun phrases to distant grammatical positions that determine their thematic roles. For instance, the head noun of a relative clause is related to a grammatical position in the relative clause that determines the role it plays around the verb of the relative clause. This is illustrated in the sentence, “The boy who the girl chased t fell down,” in which the boy is related to the position of the object of the verb chased (marked by t, standing for “trace,” in Chomsky's [1981, 1986, 1995] syntactic theory) and plays the thematic role of theme of chased. The claim that this operation connecting noun phrases to distant syntactic positions, called “the co‐indexation of traces,” occurs in Broca's area is hotly contested [Balogh et al., 1998; Berndt and Caramazza, 1999; Blumstein et al., 1998; Caplan, 1995, 2000, 2001; Caramazza et al., 2001; Drai et al., 2001; Drai and Grodzinsky, 1999; Grodzinsky et al., 1999].

Functional neuroimaging studies using PET and fMRI are beginning to provide data regarding the localization of syntactic processing in sentence comprehension.

Several studies that have compared reading and listening to sentences with fixation, processing words, and other simple baseline tasks have found activation in a relatively wide region of the perisylvian cortex. These studies all have significant limitations with respect to their interpretation.

Mazoyer et al. [1993] used PET to compare rCBF when native speakers of French were at rest with rCBF when they listened to lists of French words, stories in a foreign language, a French story with pseudowords instead of content words, a French story with semantically anomalous content words, and a story in normal French. They found left sided perisylvian activation in the conditions with comprehensible sentences, and anterior temporal foci in conditions that involved syntactically well‐formed stimuli. They concluded that the left anterior temporal lobe was involved in syntactic processing. This conclusion, however, is premature for two reasons. First, the conditions that activated the left anterior temporal lobe also consisted of stimuli with normal French intonational contours, so it is possible that the activation seen in this region reflects assigning intonational, not syntactic, structure. Second, the authors did not report comparisons of PET activity across the various activation conditions, only comparisons of each condition against a resting baseline. Much of their interpretation of their data, however, rests on claims about differences across conditions, the statistical reliability of which is not established.

Bookheimer et al. [1993], using fMRI, compared subjects' judgments of whether sentences were the same in meaning when they contained the same words but differed in word order with the control conditions of monitoring sentences for a phoneme change, listening to identical pairs of sentences, and resting. They reported increased rCBF in Broca's area and in the left hippocampus. The comparison of the “word order change” condition against the “identity” condition is more likely to highlight memory for sentence meaning and verbatim short‐term memory than syntactic processing or sentence comprehension per se.

Using PET, Stowe et al. [1994] compared reading sentences word by word to rest and found several activated left perisylvian sites. Bavelier et al. [1997] used high magnetic field (4 Tesla) fMRI to compare rCBF when subjects read sentences vs. consonant strings presented item by item. They found patchy activation throughout the left perisylvian cortex whose location varied in different individuals. Chee et al. [1999] found activation throughout the left perisylvian cortex, as well in frontal and occipital regions and, to a lesser extent, in the right hemisphere, in an fMRI study in fluent English/Mandarin bilinguals that compared sentence comprehension in both languages against fixation and nonsense character baselines, with some individual differences in the exact areas of activation across subjects but a high degree of overlap of activations in the two languages within each subject. Using fMRI, Carpenter et al. [1999] found increased BOLD signal in temporal and parietal lobe during the sentence reading portion of a sentence‐picture matching task that required verification of spatial relations. These studies involve comparisons of sentence‐level processing against very low‐level baselines, and any number of operations may have been responsible for the patterns of activation seen.

Nichelli and Grafman [1995] used a variant of the subtraction approach, in which task demands were varied whereas sentence structure was held constant. These researchers compared detection of a syntactic anomaly against detection of a word in a different font, presenting the same sentences in the two conditions. They found right inferior frontal, cingulate, and left precentral activation in the [syntax minus font] subtraction. The approach of presenting the same stimuli in different tasks, however, does not create a situation in which there is a simple difference between the operations involved in the experimental and baseline conditions. These results are hard to integrate with others and, because of the interpretive difficulty inherent in the comparison, their implications for the functional neuroanatomy of syntactic processing are unclear.

Overall, these studies indicate that sentence comprehension involves the dominant hemisphere, and suggest that areas both within and outside the perisylvian cortex may be involved in this function. The experiments, however, were not designed to isolate syntactic processing and their implications for the functional neuroanatomy of syntactic processing are therefore limited.

A number of controlled experiments have focused more narrowly on syntactic processing. Table I summarizes the results of studies of this sort.

Table I.

Areas of increased vascular response related to aspects of sentence processing

| Study | Conditions | Operation/comments | Areas activated (Talairach x, y, z, if reported) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Studies varying task | |||

| Nichelli and Grafman, (1995) | Detection of a word in a different font | Syntactic monitoring | R. BA 44 |

| Subjects read fables | |||

| Detection of syntactic anomaly | |||

| Dapretto and Bookheimer, | Rest | Syntactic processing | L. BA 44 |

| (1999) | Synonymity judgment for sentences with different words | (−44, 22, 10) | |

| Synonymity judgment for sentences with different syntactic structures | Semantic processing | L. BA 47 | |

| (−48, 20, −4) | |||

| Studies varying sentence type within task | |||

| Stowe et al., (1994) | Reading unambiguous sentences | Processing ambiguity | Broca's area |

| Reading ambiguous sentences | |||

| Stromswold et al., (1996) | Written plausibility judgment | Memory load associated | pars opercularis (BA 45) |

| subject‐object relative clauses | with assigning more | (−46.5, 9.8, 4.0) | |

| object‐subject relative clauses | distant antecedent of a trace, or increased number of syntactic integrations | ||

| Just et al., (1996) | Question answering | As in Stromswold et al., (1996) | L. superior and middle temporal gyri |

| Conjoined sentences | |||

| Subject subject relatives | Memory for sentence | (BA 22, 42, 21) | |

| Subject object relatives | content needed | L. inferior frontal gyrus | |

| (BA 44, 45) | |||

| R. homologues of above | |||

| Caplan et al., (1998) | Written plausibility judgment | As in Stromswold et al., (1996) | Pars opercularis (BA 45) |

| Subject‐object relative clauses | (−42, 18, 24) | ||

| Object‐subject relative clauses | Cingulate (BA 32) | ||

| (−2, 6, 40) | |||

| Medial frontal gyrus | |||

| (10, 6, 52) | |||

| Caplan et al., (1999) | Auditory plausibility judgment | As in Stromswold et al., (1996) | Pars triangularis (BA 44) |

| Cleft object sentences | (−52, 18, 24) | ||

| Cleft subject sentences | Superior parietal lobe (BA 7) | ||

| (−18, −48, 44) | |||

| Medial frontal gyrus (BA 6) | |||

| (−2, 18, 48) | |||

| Caplan et al., (2000) | Written plausibility judgment | As in Stromswold et al., (1996) | Pars opercularis (BA 45) |

| with concurrent articulation | (−46, 36, 40) | ||

| Subject‐object relative clauses | Evidence against rehearsal | L centromedian nucleus | |

| Object‐subject relative clauses | determining rCBF effect | (−14, −20, 4) | |

| Cingulate (BA 31) | |||

| (−10, −36, 40) | |||

| Medial frontal gyrus (BA 10) | |||

| (0, 56, 8) | |||

| Other designs | |||

| Stowe et al., (1998) | a) Words | a < b < c < d (sentence processing load) | (L) BA 21, 22 |

| Conditions weighted to measure psycholinguistic operations | b) Simple sentences | (−34, −58, 4) | |

| c) Syntactically complex sentences | b < c = a < d (complex memory load | (L) BA 44, 45 | |

| d) Syntactically ambiguous sentences | (38, 14, 12) | ||

| Ni et al., (2000) | Odd‐ball detection | Syntactic processing | BA 44, 45, 47; more superior |

| Detection of syntactic anomaly | (syntax − semantics) | frontal (BA 8) | |

| Detection of semantic anomaly | Semantic processing | B21, 22, 37, 39, 24, 31 | |

| Well formed sentences | (semantics − syntax) | ||

Stromswold et al. [1996] contrasted more complex subject object (SO) sentences (e.g., The juice that the child spilled stained the rug) with less complex object subject (OS) sentences (e.g., The child spilled the juice that stained the rug). Eight right‐handed young male subjects read a sentence and made a speeded decision as to whether it was plausible or not. Stromswold et al. [1996] reported an increase in rCBF in the pars opercularis of Broca's area when PET activity associated with OS sentences was subtracted from that associated with SO sentences. Caplan et al. [1998] replicated this study with eight young female subjects, ages 21–31 years and also reported an increase in rCBF in the pars opercularis of Broca's area in the SO minus OS comparison. Caplan et al. [1999] utilized cleft object (CO) sentences (e.g., It was the juice that the child spilled) and baseline cleft subject (CS) sentences (e.g., It was the child that spilled the juice) with auditory presentation in 16 young right‐handed male and female subjects. They reported an increase in rCBF in the pars triangularis of Broca's area in the CO minus CS comparison. Caplan et al. [2000] repeated the Stromswold et al. [1996] and Caplan et al. [1998] experiments under conditions of concurrent articulation (saying the word “double” at a rate of one utterance per minute, paced metronomically), which engages the articulatory loop and prevents its use for rehearsal [Baddeley et al., 1975]. In 11 young right‐handed male and female subjects, they continued to find an increase in rCBF in the pars opercularis of Broca's area in the SO minus OS comparison. Using fMRI, Dapretto and Bookheimer [1999] had subjects make synonymity judgments about pairs of sentence that differed in syntactic structure (e.g., The policeman arrested the thief, The thief was arrested by the policeman). They found increased BOLD signal in Brodmann's area 44 compared to both a baseline resting condition and to a condition in which synonymity was based upon word meanings.

These experiments present a consistent picture according to which Broca's area is involved in processing more complex relative clauses and passive sentences. The fact that the activation in Broca's area associated with more complex relative clauses persisted under concurrent articulation conditions strongly suggests that Broca's area is involved in some aspect of syntactic processing that differs in the two sentence types, not simply in rehearsing the more complex sentences more than the simple ones. No other regions of the perisylvian association cortex were activated in these experiments, suggesting that Broca's area plays a special role in processing these structures in this population. Both relative clauses and passive sentences contain traces in Chomsky's theory, so these results are consistent with the hypothesis that Broca's area is involved in co‐indexation of traces. More specifically, they are consistent with the claim that Broca's area increases its vascular response when subjects process sentences in which the co‐indexation of a trace involves a greater memory or processing load.

The conclusion, however, that Broca's area is the sole area that supports syntactic processing associated with sentences in which the co‐indexation of a trace is more demanding appears to be contradicted by a study by Just et al. [1996]. These authors reported an fMRI study in which subjects read and answered questions about conjoined, subject–subject and subject–object sentences. These authors reported an increase in rCBF in both Broca's area and in Wernicke's area of the left hemisphere, as well as smaller but reliable increases in rCBF in the homologous regions of the right hemisphere, when subjects were presented with the more complex subject‐subject and subject‐object sentences. The stimuli in the Just et al. [1996] study involve relative clauses that include the same structural contrasts as those in the studies by Stromswold et al. [1996] and Caplan et al. [1998, 1999, 2000], and therefore these studies provide evidence that increasing the processing load associated with the co‐indexation of traces increases vascular responses in areas of the brain other than Broca's area.

A second study that suggests that this is the case is that of Stowe et al. [1998]. Stowe and her colleagues measured PET activity when subjects read lists of words, simple sentences, syntactically complex sentences, and syntactically ambiguous sentences, and performed linear regression analyses on the PET data based on weights for the conditions that simulated different psychological processes. The combination of weights related to what they called “sentence processing load” (list < simple sentences < complex sentences < ambiguous sentences) predicted rCBF in the posterior left temporal lobe. This study is less easily interpreted than the studies by Caplan and his colleagues and Just et al. [1996], because the different conditions are quite heterogeneous, and the operations and mechanisms that make for increased processing demands in the factor termed “sentence processing load” are not clear.

Finally, we note that Broca's area has been activated by two studies that required syntactic operations other than processing of relative clauses. Ni et al. [2000] used the odd‐ball technique, presenting semantically anomalous (e.g., Trees can eat) or syntactically ill‐formed sentences (e.g., Trees can grew) occasionally in a sequence of well‐formed sentences (e.g., Trees can grow). Compared to well‐formed sentences, the syntactic anomalies strongly activated the left inferior frontal lobe, with lesser activation in the posterior language areas, which arose bilaterally. This study provides evidence that Broca's area is involved in detecting agreement violations. In addition to their main experimental results, Stowe et al. [1994] also mention a comparison of PET activity associated with syntactically ambiguous sentences against activity associated with unambiguous sentences expressing one of the meanings of the ambiguous sentences that contained almost the same words as the ambiguous stimuli (part of their experiment 2). This comparison yielded increased rCBF in Broca's area. This study suggests that Broca's area may be involved in syntactic processes related to ambiguity resolution, though, without knowing the exact sentence types used in that study, it is impossible to be more specific about what these processes may be.

Experimental designs are limited in potentially important ways in standard MRI and PET. Sentences must be blocked by type, raising the possibility that subjects may use task‐specific strategies to understand sentences in these experiments [Carpenter et al., 1999]. The activation results reflect both plausible and implausible sentences in plausibility judgment tasks, and include processing the assertions to be verified and recalling the stimulus sentences in question‐answering tasks. In addition, neither PET nor conventional fMRI can measure activation associated with specific parts of sentences. The recently developed method of event‐related fMRI offers significant advantages in experimental design, such as allowing intermixing of stimulus types, and allows for the measurement of the time course of activity associated with specified types of sentences and with specific parts of sentences [Rosen et al., 1998]. We used event‐related fMRI to study vascular activity associated with processing relative clauses.

We examined two sentence types with relative clauses that differ in the difficulty they pose for syntactic analysis: a simpler “subject subject” (SS) sentence type (The reporter who admired the photographer appreciated the award), and a more complex “subject object” (SO) sentences (The reporter who the photographer admired appreciated the award). We tested the hypothesis that BOLD signal would increase in association with the relative clause of the SO compared to the SS sentences.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

Nineteen subjects took part in a pilot experiment, and 10 (mean age 24.8 years, range 18–31; mean years of education 17, range 12–21) in the fMRI experiment. All subjects were right‐handed. All gave informed consent.

Materials

We presented 144 pairs of matched subject object (SO) and subject subject (SS) sentences. In the simpler SS sentence type (The reporter who admired the photographer appreciated the award), the head noun of the relative clause (the reporter) and the verb of the relative clause (admired) occur without an intervening noun that can play a thematic role around a verb. In the more complex SO sentences (The reporter who the photographer admired appreciated the award), subjects need to maintain the head noun of the relative clause (the reporter) in a memory buffer while they encounter another noun that can play a thematic role around a verb (the photographer) before they encounter the verb of the clause. This increases the memory load during the relative clause in SO compared to SS sentences [Gibson, 1998] and this increased load affects the processing of both the verb of the relative clause and that of the following main clause [King and Just, 1991].

Each pair of sentences began with the same words, and ended with either an SS or an SO clause. The initial identical portion of the sentences consisted of a noun phrase followed by a five‐word participial phrase (e.g., The reporter covering the big story carefully). The participial phrase (covering the big story carefully) was “padding,” introduced to create stimuli that were identical for a period, during which hemodynamic responses were not expected to differ across the two sentence types, that could be compared against a portion of the sentence in which the syntactic structure of the two sentences differed, where hemodynamic response differences were expected to be found. The sentence then continued with either an SS relative clause (who admired the photographer) or an SO relative (who the photographer admired), and ended with a predicate (appreciated the award). Despite their syntactic differences, the SS and SO sentences contained the same words, so that differences in lexical items were not responsible for any rCBF effects.

Half the sentences were plausible and half were implausible. Implausibility was created by an incompatibility between the animacy or humanness features of a noun phrase and the requirements of a verb, as in The reporter…who the photograph admired…. Subjects made a plausibility judgment as quickly as they could following each sentence.

Psycholinguistic Methods

Before the fMRI experiment, we presented these stimuli in a self‐paced word‐by‐word reading experiment. Stimuli were presented via an Apple Macintosh G3 computer using the Psyscope development and presentation package. Subjects viewed each word and pushed a response key interfaced with the computer to trigger the presentation of each subsequent word. Reading times were recorded for each word. At the end of each sentence, subjects made a timed plausibility judgment.

In the fMRI experiment, the materials were presented using word‐by‐word rapid serial visual presentation (RSVP). Word exposure durations were 500 msec, based upon the reading time data obtained in the pilot study (the longest mean reading time for any word in the self‐paced study). Subjects made a plausibility judgment after each sentence. Stimuli were presented via an Apple Macintosh G3 computer. Visual images were projected to subjects (Sharp 2000 color LCD projector) through a collimating lens (Buhl Optical). A screen attached to the standard General Electric quadrature head coil received the projected images. A custom‐designed magnet‐compatible key press interfaced with the Apple Macintosh G3 was used to record subject performance and reaction times. Subjects' heads were immobilized with pillows, cushions, and a restraining strap to reduce motion artifact. Nine blocks of four baseline fixations and 16 sentences were presented in each of two sessions. Each sentence trial was 14 words long, beginning with 500 msec of fixation and 500 msec of a blank screen and followed by 4 sec of a blank screen. Stimuli were pseudorandomized so as to meet the requirements for analysis of event‐related fMRI data [Dale and Buckner, 1997].

Imaging Methods

Functional imaging was performed on a 3.0T General Electric scanner with an echo planar (EP) imaging upgrade (Advanced NMR Systems). A series of whole brain EP images (16 slice, 3.125 mm in‐plane resolution, 7 mm thickness, skip 1 mm between slices, acquisition aligned to the plane intersecting the anterior and posterior commissures) were collected to provide functional images sensitive to blood‐oxygen‐level‐dependent (BOLD) contrast. These consisted of an automated shim procedure to improve B0 magnetic field homogeneity [Reese et al., 1995] and T2*‐weighted functional image runs using a gradient echo sequence (TR = 2 sec; TE = 30 msec; flip angle = 90). A series of conventional structural images, consisting of a high resolution rf‐spoiled GRASS sequence (SPGR; 60 slice sagittal, 2.8 mm thickness) and a set of T1 flow‐weighted anatomic images in plane with the functional EP images (16 slices, 1.6 mm in‐plane resolution, 7 mm thickness, skip 1 mm between slices), were collected on a 1.5T GE scanner to provide detailed anatomic information. The automated Talairach registration procedure developed and distributed by the Montreal Neurological Institute [Collins et al., 1994; Talairach and Tournoux, 1988] was used to compute the transformation matrix from the high‐resolution T1‐weighted scans. Data from individual fMRI runs were normalized to correct for signal intensity changes and temporal drift by scaling of whole‐brain signal intensity to a fixed value of 1,000, removal of linear slope on a voxel‐by‐voxel basis to counteract effects of drift [Bandettini et al., 1993], spatial filtering with a 1.5‐voxel radius Hanning filter, and removal of the mean signal intensity on a voxel‐by‐voxel basis. Normalized data were selectively averaged for each subject across runs in relation to the beginning of each trial type. The selectively averaged data were resam‐ pled into Talairach space. Normalized fMRI runs were selectively averaged within each subject such that ten mean images (20 sec at TR = 2 sec) were retained for each trial type as well as the variance for each of the ten images per trial type [Burock et al., 1998; Dale and Buckner, 1997]). Statistical activation maps were generated based on the difference between trial types using a t‐statistic [Dale and Buckner, 1997]. Peak activation coordinates in the Talairach and Tournoux atlas space were generated for the group.

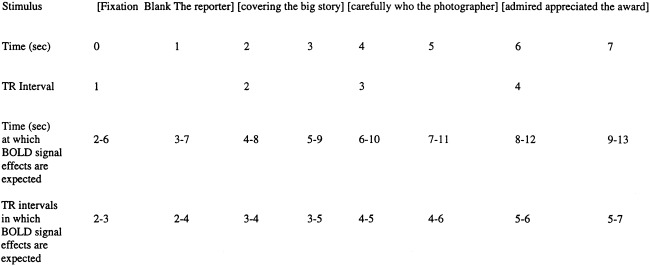

Analysis of BOLD activity in all sentence conditions vs. the fixation conditions was performed at TR intervals selected to correspond to time points at which vascular responses were expected to be related to the first perception of the sentence, processing of the sentence, and preparing and making the motor response indicating the plausibility judgment regarding the sentence. BOLD signal changes follow electrophysiological events associated with elementary sensory stimuli and simple motor functions by as little as 2 sec, and the BOLD signal response to elementary sensory or motor events is usually well established by 4–6 sec [Bandettini, 1993; Turner et al., 1997]. The relationship between the TR interval at which particular words of the stimulus sentences were presented and the TR interval in which the BOLD signal response that corresponded to those words is expected, is shown in Figure 1. Based on this expected relationship, the “all vs. fixation” comparisons were conducted at TR intervals 4, 8, and 12 sec after the onset of each trial. BOLD activity in these comparisons was considered significant if it reached the threshold of P < 10−10, a significance level that corrects for the number of tests that were made in these comparisons.

Figure 1.

Time course of presentation of stimulus sentences and TR intervals in which BOLD signal associated with portions of the sentence is likely to be detected.

Eight regions of interest in which there was reliable BOLD signal for sentence vs. fixation trials that was significant at P < 10−10 were selected for analysis: bilateral visual cortex (Brodmann areas 17–19), left posterior superior temporal gyrus (BA 22), left angular gyrus (BA 39), left supramarginal gyrus (BA 40), Broca's area pars opercularis (BA 44), Broca's area pars triangularis (BA 45), left premotor cortex (BA 6), and middle left motor cortex (at the level of the representation of the hand: BA 4). ROIs were defined in Talairach space by one of the authors (DC). Voxels for each run for each subject in each ROI were selected for analysis based on a functional threshold consisting of a difference in BOLD signal for sentence vs. fixation trials that was significant at P < 10−2. The difference between BOLD activity in SO and SS sentences was compared for late time periods against early time periods. In the late time periods, the hemodynamic response was expected to reflect processing the relative clause, which differed across sentence types and was more complex in SO sentences. In the early time periods, the hemodynamic response was expected to reflect processing portions of the sentences that did not differ across the two sentence types. Based on the estimates of onset and maximum of BOLD activity relative to the presentation of each word in the stimulus, we grouped the 2 TR intervals preceding stimulus onset (included to establish a baseline) and the first 3 TR intervals from stimulus onset in the “early” time period (TR intervals −2, −1, 1, 2, 3), and the next 4 TR intervals in the “late” time period (TR intervals 4, 5, 6, 7).

RESULTS

Behavioral Results: Pilot Study

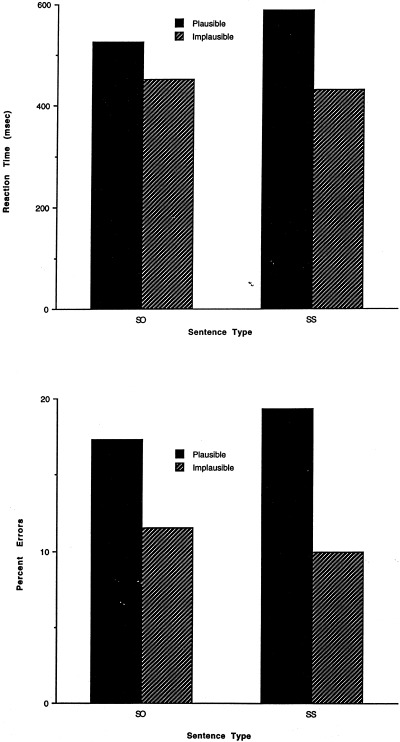

Reaction times and percent errors for each sentence type are shown in Figure 2. Reaction times to the plausibility judgment that were more than three standard deviations above and below each subject's mean for each condition were eliminated. Accuracy and the resulting reaction times for the plausibility judgments were analyzed in 2 (sentence type: SO, SS) × 2 (plausibility: plausible; implausible) ANOVA. There was an effect of plausibility (for reaction times, F[1,18] = 11.34, P < 0.01; for accuracy F[1,18] = 5.0, P < 0.05). Subjects responded faster and made fewer errors on the implausible sentences. There was no effect of sentence type, and no interaction between sentence type and plausibility.

Figure 2.

RT and percent errors for sentence types in pilot self‐paced reading study.

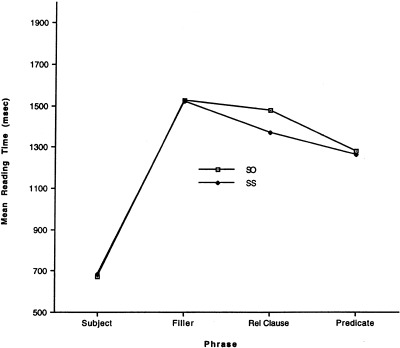

For the reading time data, reading times more than 3 SD above and below each subject's mean for each phrase in each condition were eliminated. Because reading times were affected by semantic anomalies, only the resulting reading times for acceptable sentences to which subjects responded correctly were analyzed in a 2 (sentence type: SO, SS) × 4 (phrase: SUBJ, FILLER, RELATIVE CLAUSE, PREDICATE) ANOVA. There was a significant interaction between sentence type and phrase (F[3,54] = 2.9, P < 0.05). Reading times were longer for the words of the relative clause of the SO than for those of the SS sentences, indicating an increase in processing load at the expected point in the SO sentences (see Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Reading times for phrases of plausible sentences to which subjects responded correctly in pilot self‐paced reading study.

Behavioral Results: fMRI Study

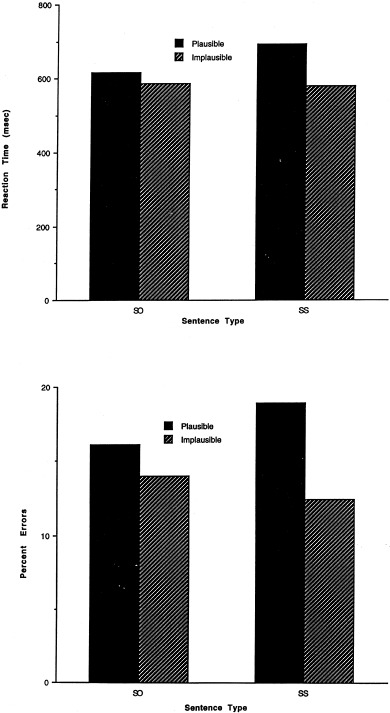

Mean percent errors and reaction times to the plausibility judgments are shown in Figure 4. Reaction times that were more than three standard deviations above and below each subject's mean for each condition were eliminated. Accuracy and resulting reaction times were analyzed in 2 (sentence type: SO, SS) × 2 (plausibility: plausible; implausible) ANOVA. There was an effect of plausibility in the reaction time data (F[1,9] = 7.6, P < 0.01). Subjects responded faster to the implausible sentences. There was no effect of sentence type, and no interaction between sentence type and plausibility.

Figure 4.

RT and percent errors for sentence types in rapid serial visual presentation (RSVP) MR study.

BOLD Signal Results

Figure 5 shows BOLD signal activity associated with processing the two sentence types compared to that associated with simple visual fixation at TR intervals 4, 8 and 12 sec after the onset of each stimulus. As noted above, these are points in time at which BOLD signal effects are expected to be associated with the first perception of the sentence, processing of the sentence, and preparing and making the motor response indicating the plausibility judgment regarding the sentence. At the 4‐sec delay, BOLD signal was seen in both occipital regions. At the 8‐sec delay, BOLD signal occurred in the left perisylvian association cortex, and at the 12‐sec delay it appeared in the left premotor and left motor regions. The location of these BOLD signal changes is consistent with what is known about the localization of the visual, linguistic, and motor planning and execution aspects of the task. The time course of activation of these regions can be related to the sequence of perceptual, linguistic and motor functions required by the task. This latter interpretation of these data, however, must be viewed cautiously because of different patterns of vascular responsivity in different brain regions.

Figure 5.

Mosaic of BOLD signal increases for processing of all sentences compared to visual fixation, showing voxels with a probability of activation of P < 10−10. The color scale represents −log10 (P). Images are shown in coronal section. The top line of each figure represents posterior brain regions, and subsequent lines show more anterior regions. Within each line, images are shown in a posterior‐to‐anterior sequence from left to right. The first line of each figure shows coronal sections that correspond approximately to Talairach y‐axis sections from −72 to −50; the second line to Talairach y‐axis sections from −50 to −28; the third line to Talairach y‐axis sections from −28 to −6; the second line to Talairach y‐axis sections from −6 to +16; the fifth line to Talairach y‐axis sections from +16 to +38. A: Shows activation 4 sec after the onset of the first word of the sentences. Because of the lag in hemodynamic response, this period reflects BOLD signal associated with viewing first words in the sentence. BOLD signal is seen at this time bilaterally in occipital cortex. B: Shows activation 8 sec after the onset of the first word of the sentences, when the hemodynamic response reflects processing the sentence. BOLD signal continues to be seen bilaterally in occipital cortex and also involves the left perisylvian association cortex. C: Shows activation 12 sec after the onset of the first word of the sentences. The sentence presentation has been over for 5 sec and the hemodynamic response reflects making the plausibility judgment by a button‐press using the right hand. BOLD signal is less visible in occipital cortex and now is seen prominently in left motor and pre‐motor regions.

BOLD signal increased in a small number of midline structures in the fixation minus sentences comparison.

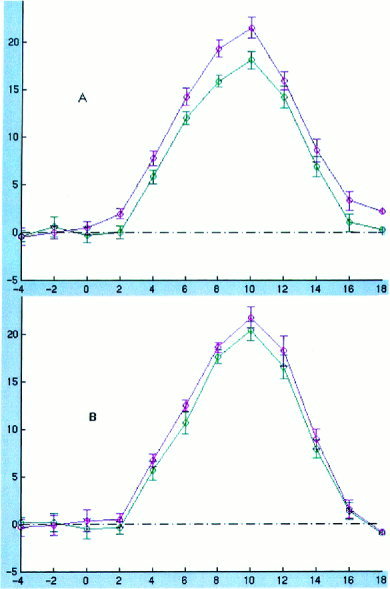

To investigate the location of the brain regions involved in syntactic processing, we compared the time course of BOLD signal for the more complex SO and less complex SS sentences. BOLD signal effects related to processing the more complex region of the SO sentences would be expected to occur approximately 7–13 sec after the onset of the stimulus, as shown in Figure 1. We subtracted BOLD signal in each TR interval associated with the less complex SS sentences from that associated with the more complex SO sentences, and compared these difference scores in early and late TR intervals, as described above. For plausible sentences, both analysis revealed a significantly greater BOLD signal for the SO sentences in the late time period in the left angular gyrus and a trend toward such an increase in the adjacent portion of the first temporal gyrus (Wernicke's area) (in BA 39, t = 3.2, P = 0.005; in BA22, t = 1.8, P = 0.08). The time course of BOLD signal response to the two sentence types in these regions is shown in Figure 6. There were no areas in which BOLD signal was increased in the comparison of implausible SO sentences minus implausible SS sentences, or in which BOLD signal was reduced in the comparison of SO minus SS sentences. Analysis of the time curves in individual subjects did not show any areas in which these analyses of the difference in BOLD signal responses between sentence types yielded significant results.

Figure 6.

Time course of BOLD signal for SO sentences (magenta) and SS sentences (green). The abscissa represents TR intervals; the ordinate represents intensity normalized BOLD signal. There is a reliable increase in BOLD signal late in the time course of sentence processing in the angular gyrus (A) and a trend toward this effect in Wernicke area (B), indicating increased hemodynamic response to processing the more complex portion of syntactically more complex sentences in these regions of cortex.

DISCUSSION

The behavioral results show several effects worth noting.

Plausibility judgments were faster to implausible than to plausible sentences in both the self‐paced and the RSVP conditions. This is likely to be due the fact that anomaly could be detected before the end of most anomalous sentences but sentences could not be judged to be plausible until their last word. Accuracy was also higher on implausible sentences. This suggests that subjects adopted stringent criteria for accepting a sentence as being plausible, or benefited from the time available after an implausibility occurred to become certain of their judgments.

The results of the pilot self‐paced reading study indicate that subjects found the relative clause portion of plausible SO sentences more difficult to process than the corresponding portion of the SS sentences. The location of this processing difficulty is expected, given current models of the syntactic and semantic processing involved in these sentences [Gibson, 1998]. End‐of‐sentence plausibility judgments did not differ in for SO and OS sentences terms of RTs and accuracy in either the self‐paced or the RSVP conditions. The fact that, despite the local increase in reading times at the relative clause of SO sentences, end‐of‐sentence plausibility judgments did not differ for SO and OS sentences, indicates that subjects succeeded in assigning the structure and meaning of the relative clauses in both sentence types. In the self‐paced pilot study, they did so by spending more time processing the phrases with higher processing demands in the SO sentences when these phrases occurred, and in the RSVP MR experiment, they were given sufficient time to process each phrase at it occurred.

This study demonstrates the sensitivity of event related fMRI to hemodynamic changes in regions of the brain involved in sentence processing. For the comparison of all sentences against fixation, the location of BOLD signal corresponded to present knowledge regarding gross functional neuroanatomy: bi‐occipital activation, reflecting perception of the visually presented stimuli; left perisylvian activation, reflecting language processing; and left motor and premotor activation reflecting the subjects' manual responses with their right hands. In addition, the time course of activation of these regions can be related to the sequence of perceptual, linguistic and motor functions required by the task. As noted above, however, this interpretation of the temporal course of these vascular responses must be viewed cautiously because of different patterns of vascular responsivity in different brain regions.

We were also able to identify a pattern of BOLD signal specifically associated with syntactic processing. For plausible sentences, BOLD signal increased in the left angular gyrus and marginally increased in the adjacent first temporal gyrus at a point in time that corresponds to the processing of the syntactically complex portion of the more complex sentences. This demonstration of a regional increase in BOLD signal associated with processing the more syntactically complex portion of a sentence provides strong evidence that one aspect of syntactic processing can be localized to this region.

Considering first the psycholinguistic determinants of this activity, there are several possible operations and processes that make assigning the structure of the relative clause and using that structure to determine sentence meaning more demanding in SO compared to SS sentences [see Gibson, 1998, for discussion]. The relative clause in an SO sentence makes greater demands on a syntactically‐relevant memory system for two reasons. One is that, when the relative pronoun (who) is encountered, the prediction that an embedded verb must occur can be made and, if such a prediction is made, it must be maintained for a longer period of time in SO than in SS relative clauses. Second, when the verb of the relative clause is encountered, it must be related to the head noun of the relative clause, which is more distant in SO than in SS sentences. A second source of greater processing load in SO than in SS sentences is that a larger number of integration operations occur at the verb of the relative clause in SO than in SS sentences. In SS sentences, the verb of the relative clause can be related to (“integrated with”) its subject, whereas in SO sentences it can be related to both its subject and its object. A third source of greater processing load in SO than in SS sentences is that, in SO but not SS sentences, a new referential item occurs between the head noun of the relative clause and the verb. This increases load at the level of discourse representation. It is impossible to say which of these sources of load is responsible for the increase in BOLD signal (or rCBF) seen in this and in other studies using relative clauses; studies of other constructions that systematically vary each of these features are needed to investigate these possibilities.

Turning to the localization of this activity, the posterior portion of the perisylvian language‐related association cortex, the left angular gyrus (and, marginally, the adjacent first temporal gyrus), that was activated in this study was activated in some previous experiments, but not all. The superior left temporal lobe was activated in the studies by Just et al. [1996] and Stowe et al. [1998], but studies from our lab have not shown activation in this region [Caplan et al., 1998, 1999, 2000; Stromswold et al., 1996]. There are several possible reasons why these posterior language regions were activated in some studies and not others.

One possibility is that differences in stimulus materials led to the these different results. The sentences contrasted in our er‐fMRI study and in Just et al. [1996] were SO sentences and SS sentences, whereas the sentences contrasted in the studies by Caplan and his colleagues were SO and OS sentences. The SO–OS contrast involves more of a memory load difference than the SO–SS contrast, because, in addition to the processing load associated with object relativization, SO and OS sentences differ inasmuch as the head noun of the relative clause must also be related to the main verb in both the SO and SS sentences whereas, in the OS sentences the head noun of the relative clause is the object of the main verb and is immediately adjacent to that verb. These differences, however, cannot explain the different patterns of vascular reactivity, because they would be expected to lead to a situation in which all areas activated by the SO–SS contrast are also activated by the SO–OS contrast, which was not what was found.

A second possible explanation of the differences between the results of this study and the Just et al. [1996] study, on the one hand, and our PET studies, on the other, is that the SO/SS contrast necessarily involves presenting sentences that differ in meaning, whereas the SO/OS (and CO/CS) materials we used allow sentence pairs to be contrasted that have identical meanings and that differ only in syntactic structure. Though possible, this seems very unlikely given the nouns, verbs, and thematic roles that were used in these studies.

A third possible explanation of the difference in results is that both our er‐fMRI study and the study by Just et al. [1996] have greater task demands than our PET studies. Our er‐fMRI study imposed a high task‐related (as opposed to sentence‐related) memory load because of the way the stimuli were presented in slow RSVP form and because of the length of the sentences, with their “padding” materials. In the Just et al. [1996] study, subjects read an SO or an SS sentence and then read a second sentence, and had to indicate whether the second sentence expressed part of the meaning of the first. This also imposes a high task‐related memory load. The Stowe et al. [1998] study, which also activated left superior temporal lobe, stratified the independent variables in the regression analyses along lines of this external type of memory load. The possibility that task‐related verbal memory load is partially responsible for the increase in vascular responses in the posterior language area receives support from other functional neuroimaging studies that have related vascular responses in this area to short‐term storage of verbal stimuli [Smith et al., 1998] and from the effects of lesions in the inferior parietal lobe, which are associated with reduced ability to store such material [Vallar and Shallice, 1990]. It is important to note, however, that the task‐related memory load is the same in both the SO and the SS conditions used in both our er‐fMRI study and the Just et al. [1996] study. Therefore, if this mechanism is to be invoked, it must be the case that it is the combination of a syntactic processing load and higher task demands for retention of words or propositional content in short‐term memory that leads to increases in hemodynamic responses in this area. One way these factors might combine is if subject review more complex sentences to a greater extent when task‐related memory load is high.

A final possibility is that there are individual differences in the location of the neural tissue that supports aspects of syntactic processing. Just as some right‐handed individuals are right‐hemisphere dominant for language, indicating that there is variability with respect to the inter‐hemispheric lateralization of language functions even in what appears to be a neurobiologically homogeneous population, it may be the case that there is some degree of variability in the intra‐hemispheric localization of language processing operations. This possibility is consistent with the variable effects of strokes in particular portions of the dominant perisylvian cortex on syntactic processing and other functions [Caplan, 1994, 2001; Caplan et al., 1996].

In summary, this study documents an increase in vascular responsivity (BOLD signal) that is temporally associable with processing the more demanding portion of syntactically more complex relative clauses. The location of this increase in BOLD signal, in the left inferior parietal lobe, is consistent with effects of lesions in this region. It differs from some previous results of functional neuroimaging studies, raising a number of questions about the exact mechanisms that determine it that can only be answered by further detailed studies.

REFERENCES

- Baddeley AD, Thomson N, Buchanan M (1975): Word length and the structure of short‐term memory. J Verbal Learn Verbal Behav 14: 575–589. [Google Scholar]

- Balogh J, Zurif EB, Prather P, Swinney D, Finkel L (1998): Gap filling and end of sentence effects in real‐time language processing: implications for modeling sentence comprehension in aphasia. Brain Lang 61: 169–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandettini P (1993): MRI studies of bain activation: temporal characteristics In: Functional MRI of the brain (Workshop syllabus). Berkeley, CA: Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine; p. 143–151. [Google Scholar]

- Bandettini P, Jesmanowicz A, Wond E, Hyde J (1993): Processing strategies for time‐course data sets in functional MRI of the human brain. Magn Reson Med 30: 161–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bavelier D, Corina D, Jezzard P (1997): Sentence reading: a functional MRI study at 4 Tesla. J Cogn Neurosci 9: 664–686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berndt R, Mitchum C, Haendiges A (1996): Comprehension of reversible sentences in agrammatism: a meta‐analysis. Cognition 58: 289–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berndt R, Caramazza A (1999): How “regular” is sentence comprehension in Broca aphasia? It depends on how you select the patients. Brain Lang 67: 242–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bookheimer SY, Zeffiro TA, Gallard W, Theodore W (1993): Regional cerebral blood flow changes during the comprehension of syntactically varying sentences. Neuroscience Society Abstracts 347.5: 843. [Google Scholar]

- Blumstein S, Byma G, Kurowski K, Hourihan J, Brown T, Hutchinson A (1998): On‐line processing of filler‐gap constructions in aphasia. Brain Lang 61: 149–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burock MA, Buckner RL, Woldorff MG, Rosen BR, Dale AM (1998): Randomized event‐related experimental designs allow for extremely rapid presentation rates using functional MRI. Neuroreport 9: 3735–3739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caplan D (1994): Language and the brain In: Gernsbacher M, editor. Handbook of psycholinguistics. New York: Academic Press; p. 1023–1053. [Google Scholar]

- Caplan D (1995): Issues arising in contemporary studies of disorders of syntactic processing in sentence comprehension in agrammatic patients. Brain Lang 50: 325–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caplan D (2000): Lesion location and aphasic syndrome do not tell us whether a patient will have an isolated deficit affecting the co‐indexation of traces. Behav Brain Sci 23: 25–27. [Google Scholar]

- Caplan D (2001): The neural basis of syntactic processing: a critical look In: Hillis A, editor. Handbook of adult language disorders: neurolinguistic models, neuroanatomical substrates, and rehabilitation. New York: Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Caplan D, Baker C, Dehaut F (1985): Syntactic determinants of sentence comprehension in aphasia. Cognition 21: 117–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caplan D, Hildebrandt N, Makris N (1996): Location of lesions in stroke patients with deficits in syntactic processing in sentence comprehension. Brain 119: 933–949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caplan D, Waters G, Hildebrandt N (1997): Determinants of sentence comprehension in aphasic patients in sentence‐picture matching tasks. J Speech Hear Res 40: 542–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caplan D, Alpert N, Waters G (1998): Effects of syntactic structure and propositional number on patterns of regional cerebral blood flow. J Cogn Neurosci 10: 541–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caplan D, Albert N, Waters G (1999): PET studies of sentence processing with auditory sentence presentation. Neuroimage 9: 343–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caplan D, Alpert N, Waters G, Olivieri A (2000): Activation of Broca area by syntactic processing under conditions of concurrent articulation. Hum Brain Mapp 9: 65–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caramazza A, Capitani E, Rey A, Berndt RS (2001): Agrammatic Broca aphasia is not associated with a single pattern of comprehension performance. Brain Lang 76: 158–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter PA, Just MA, Keller TA, Eddy WF, Thulborn KR (1999): Time course of fMRI‐activation in language and spatial networks during sentence comprehension. Neuroimage 10: 216–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chee MWL, Caplan D, Soon CS, Sriram N, Tan EWL, Thiel T, Weekes B (1999): Processing of visually presented sentences in Mandarin and English studied with fMRI. Neuron 23: 127–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky N (1981): Lectures on government and binding. Dordrecht: Foris. [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky N (1986): Knowledge of language. New York: Praeger. [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky N (1995): Barriers. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Collins LD, Neelin P, Peters TM, Evans AC (1994): Automatic 3D inter‐subject registration of MR volumetric data in standardized Talairach space. J Comput Assist Tomogr 18: 192–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale AM, Buckner RL (1997): Selective averaging of rapidly presented individual trials using fNMRI. Hum Brain Mapp 5: 329–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dapretto M, Bookheimer SY (1999): Form and content: dissociating syntax and semantics in sentence comprehension. Neuron 24: 427–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drai D, Grodzinksy Y (1999): Comprehension regularity in Broca aphasia? There's more of it than you ever imagined. Brain Lang 70: 139–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drai D, Grodzinsky Y, Zurif E (2001): Agrammatic Broca aphasia is associated with a single pattern of comprehension performance. Brain Lang 76: 185–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson E (1998): Linguistic complexity: locality of syntactic dependencies. Cognition 68: 1–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grodzinsky Y (2000): The neurology of syntax: language use without Broca area. Behav Brain Sci 23: 47–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grodzinsky Y, Pinango MM, Zurif EA, Drai D (1999): The critical role of group studies in neuropsychology: comprehension regularities in Broca aphasia. Brain Lang 67: 134–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Just MA, Carpenter PA, Keller TA, Eddy WF, Thulborn KR (1996): Brain activation modulated by sentence comprehension. Science 274: 114–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King J, Just MA (1991): Individual differences in syntactic processing: the role of working memory. J Mem Lang 30: 580–602. [Google Scholar]

- Mazoyer B, Tzourio N, Frak V, Syrota A, Murayama N, Levrier O, Salamon G (1993): The cortical representation of speech. J Cogn Neurosci 5: 467–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni W, Constable RT, Mencl WE, Pugh KR, Fulbright RK, Shaywitz SE, Shaywitz BA, Gore JC, Shankweiler D (2000): An event‐related neuroimaging study distinguishing form and content in sentence processing. J Cogn Neurosci 12: 120–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichelli P, Grafman J (1995): Where the brain appreciates the moral of a story, Neuroreport 6: 2309–2313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reese TG, Davis TL, Weisskoff RM (1995): Automated shimming at 1.5T using echo‐planar image frequency maps. J Magn Reson Imaging 5: 739–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen BR, Buckner RL, Dale AM (1998): Event‐related functional MRI: past, present, and future. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 773–780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith EE, Jonides J, Marshuetz C, Koeppe RA (1998): Components of verbal working memory: Evidence from neuroimaging. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 876–882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stromswold K, Caplan D, Alpert N, Rauch S (1996): Localization of syntactic comprehension by positron emission tomography. Brain Lang 52: 452–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stowe LA, Wijers AA, et al. 1994. PET‐studies of language: an assessment of the reliability of the technique. J Psycholing Res 23: 499–527. [Google Scholar]

- Stowe LA, Broere CAJ, Paans AM, Wijers AA, Mulder G, Vallburg W, Zwarts F (1998): Localizing components of a complex task: sentence processing and working memory. Neuroreport 9: 2995–2999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swinney D, Zurif E (1995): Syntactic processing in aphasia. Brain Lang 50: 225–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swinney D, Zurif E, Prather P, Love T (1996): Neurological distribution of processing resources underlying language comprehension. J Cogn Neurosci 8: 174–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talairach J, Tournoux P (1988): Co‐planar stereotaxic atlas of the human brain. New York: Thieme Medical Publishers, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Turner R, Howseman A, Rees G, Josephs O (1997): Functional imaging with magnetic resonance In: Frackowiac RSJ, Friston KJ, Frith CD, Dolan RJ, Mazziotta JC, editors. Human brain functions. New York: Academic Press; p. 467–486. [Google Scholar]

- Vallar G, Shallice T (1990): The impairment of auditory‐verbal short‐term storage In: Vallar G, Shallice T, editors. Neuropsychological impairments of short‐term memory. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; p. 11–53. [Google Scholar]

- Zurif E, Swinney D, Prather P, Solomon J, Bushell C (1993): An on‐line analysis of syntactic processing in Broca and Wernicke aphasia. Brain Lang 45: 448–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]