Abstract

Attentional switching has shown to involve several prefrontal and parietal brain regions. Most cognitive paradigms used to measure cognitive switching such as the Wisconsin Card Sorting Task (WCST) involve additional cognitive processes besides switching, in particular working memory (WM). It is, therefore, questionable whether prefrontal brain regions activated in these conditions, especially dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC), are involved in cognitive switching per se, or are related to WM components involved in switching tasks. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) was used to examine neural correlates of pure switching using a paradigm purposely designed to minimize WM functions. The switching paradigm required subjects to switch unpredictably between two spatial dimensions, clearly indicated throughout the task before each trial. Fast, event‐related fMRI was used to compare neural activation associated with switch trials to that related to repeat trials in 20 healthy, right‐handed, adult males. A large cluster of activation was observed in the right hemisphere, extending from inferior prefrontal and pre‐ and postcentral gyri to superior temporal and inferior parietal cortices. A smaller and more caudal cluster of homologous activation in the left hemisphere was accompanied by activation of left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC). We conclude that left DLPFC activation is involved directly in cognitive switching, in conjunction with parietal and temporal brain regions. Pre‐ and postcentral gyrus activation may be related to motor components of switching set. Hum. Brain Mapp.21:247–256, 2004. © 2004 Wiley‐Liss, Inc.

Keywords: set switching, set shifting, cognitive flexibility, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC)

INTRODUCTION

The ability to shift or switch set is a fundamental component of executive functions that, together with set maintenance, interference and attentional control, inhibition, planning, and working memory, contributes toward efficient self‐regulation. In behavioral studies, cognitive flexibility has been measured traditionally using the Wisconsin Card Sorting Task (WCST). This task involves matching a target with other stimuli based on a given dimension, usually color or shape, until feedback indicates that the given dimension is no longer correct and an alternative one should be used, thus requiring a switch or shift in attentional focus or cognitive set. Because patients with prefrontal lesions have difficulties with this task it is assumed that the prefrontal cortex is involved in set switching [Milner, 1963; Stuss et al., 2000].

Imaging studies of switching function using tasks based upon the WCST support this assumption, revealing activation of inferior frontal cortex (Brodmann's area [BA] 44/45) in the left [Lauber et al., 1996] and right hemispheres [Berman et al., 1995; Konishi et al., 1998; Nagahama et al., 1998]. Activation has also been found in predominantly right [Berman et al., 1995; Fukuyama et al., 1997; Nagahama et al., 1998, 1999, 2001; Monchi et al., 2001] but also left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) (BA9/46) [Lauber et al., 1996].

Other brain regions that have been activated using tasks based on the WCST include parietal, [Berman et al., 1995; Lauber et al., 1996; Monchi et al., 2001], premotor and anterior cingulate cortices [Konishi et al., 1998, 1999, 2002; Lauber et al., 1996], and the cerebellum [Berman et al., 1995; Lauber et al., 1996; Nagahama et al., 1998].

Nagahama et al. [ 1998] found DLPFC regions to be activated consistently regardless of the number of sets across which to shift, including right middle and inferior frontal gyri (BA 46 and 44), anterior cingulate and also right parietooccipital cortex (BA 39 and 19). There has, however, been some debate concerning DLPFC and inferior prefrontal cortex and their function during attentional switching within the WCST paradigm. Nagahama et al. [ 1998] found that both inferior frontal cortex and DLPFC were related to set shifting and instruction shifting, although only DLPFC was activated during set shifting. Other studies, however, found right and left inferior frontal cortex to be related to the task‐switching component of the WCST [Konishi et al., 1999; Monchi et al., 2001], whereas DLPFC was found to be related to the working memory (WM) components of the task [Monchi et al., 2001].

The above studies have focused upon adaptations of the WCST as a measure of set shifting. Although originally developed to measure cognitive flexibility [Berg, 1948], this task does not measure cognitive switching exclusively, but co‐measures other functions, such as general intelligence, abstract reasoning, and WM. In the WCST, a subject has to sort stimuli according to three different stimulus dimensions and is informed of a switch in stimulus dimension by negative feedback. The subject then has to search for a different stimulus dimension rule to hold in WM. The prefrontal cortex thus contributes to task switching by rapidly updating activation states representing different information (i.e., stimulus dimension rules) in response to feedback, possibly by a gating mechanism that controls updating of these activation‐based working memories [O'Reilly et al., 2002; Rougier and Reilly, 2002]. To isolate further cognitive switching from other basic cognitive functions such as WM, there has been an attempt to use more specific paradigms.

Reversal tasks, for example, also require set shifting, but reduce the load on WM compared to the WCST, as they require simple reversing between two different stimulus‐response associations. A study using a reversal task in event‐related functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) isolated brain activation in correlation with switch trials in left and right dorsolateral and inferior prefrontal cortices, anterior insula, supplementary motor area (SMA) and pre‐SMA regions, posterior cingulate gyrus, and thalamus [Dove et al., 2000].

An alternative approach to isolating the activation associated with cognitive switching is the use of “pure” switching tasks, where rather than using feedback as an indicator for switching as in the WCST, explicit instructions regarding current set are displayed throughout the task. These pure switch tasks reduce the load on WM and are more likely to target switching functions such as inhibition of conflict and interference from non‐active sets [DiGirolamo et al., 2001]. A recent study of pure switching required classification of a display of digits for either value or frequency, indicated by a colored cue, whereas a control condition required no switching because classification remained constant throughout a block of trials [DiGirolamo et al., 2001]. The contrast of switch trials with non‐switch trials in block design fMRI revealed activation of bilateral dorsolateral, inferior prefrontal (BA 44, 45, 46, and 47) and medial frontal cortices (BA 24, 32, and 6) [DiGirolamo et al., 2001]. Luks et al. [ 2002] used a similar paradigm, and under conditions where trial status was unpredictable, activation was greater in left DLPFC for switch trials compared to that for repeat trials. This increase was not seen, however, where subjects were informed beforehand whether a trial would be a repeat or switch.

Switch tasks described above involve arbitrary associations between indicators and sets, so that one color may be designated as the prompt to attend to a given set whereas another color acts as the prompt for an alternative set. These Colour‐set pairings are not hard‐wired but are learned in training. They must therefore be held on‐line for the duration of the task, so that although the load on WM is reduced by displaying instructions throughout the task, the instruction set pairings must be kept on‐line within working memory.

Dove et al. [ 1999] developed an event‐related fMRI version of a pure switching task [Meiran, 1996] where a cue in the form of the letter “V” or “H” (representing either the vertical or the horizontal plane, respectively) displayed throughout the task would indicate either a switch between these two perceptual dimensions or a repeat trial. WM load in this task was therefore reduced by the continuous display of a symbol representing the perceptual dimension that had to be attended to. Activation was found in left inferior prefrontal sulcus, anterior cingulate, pre‐SMA and left precentral gyrus, anterior insula, and the basal ganglia.

We wanted to isolate further the brain activation related to pure switching, independent of WM functions. For this purpose, we used a further modification of the Meiran switch task [Meiran, 1996], where a continuous and explicitly related display using arrows indicated whether subjects had to switch their motor response to the horizontal or the vertical dimensions. As opposed to the WCST, there was only a need for a switch between two different activation states within the same stimulus dimension, i.e., the vertical and horizontal spatial dimensions. Furthermore, there was no need to search for activation states based on feedback, as the instructions were displayed continuously with every single trial. This switch task version should have thus reduced learning and WM requirements to a minimal level.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Subjects

Study subjects (20 male right‐handed adults; mean age, 28 years 8 months; age range, 20–43 years) were recruited through advertisements. Consent was obtained for all subjects and the study was approved by the local Ethical Committee. All subjects achieved an intelligence quotient (IQ) score above the 10th percentile (mean, 74th percentile) using the Ravens Standard Progressive Matrices [Raven et al., 1998] and were without history of neurologic or psychiatric disease.

Switching Paradigm

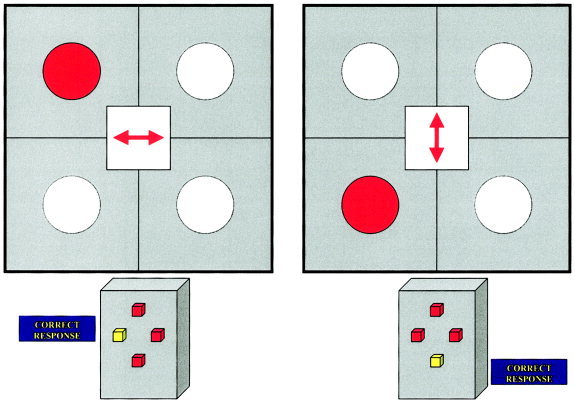

Subjects were trained on the task before scanning. The switch task used in this study was based upon a task developed by Meiran [ 1996] and was presented on a mirror within the MRI scanner during the scan (see Fig. 1). Subjects used a keypad with four buttons in a diamond configuration to make responses. Subjects were presented with a grid divided into four squares in the center of which was a double‐headed arrow positioned either horizontally or vertically. The grid with the double‐headed arrow was presented for 1,600 msec. At 200 msec after presentation of the grid and arrows, a red dot appeared for 1,400 msec in any one of four squares of the grid. A horizontally pointing double‐headed arrow indicated that the subject had to confirm whether the circle was in either of the two left or two right squares of the grid by pressing the left or right button. After 1,600 msec of presentation time, there was a blank screen for 800 ms, in which subjects could make their button response. This presentation was repeated for several trials with a total interstimulus interval (ISI) of 2.4 sec. A minimum of four repeat trials were followed by a switch trial where the double‐headed arrows in the middle of the grid changed to a vertical position, and the subject had to indicate whether the circle was in either of the two upper or two lower squares of the grid by pressing the upper or lower button. This presentation pattern was maintained for several repeat trials followed by a switch trial where the arrow changed back to a horizontal position. Subjects thus had to switch their attention and response between the horizontal dimension (the dot on the left or right side of the grid) and the vertical dimension (dot on the upper or lower part of the grid). The switch trials were separated by a minimum of four repetition times apart from each other (TR = ISI = 2.4 sec) to allow optimal separation of the hemodynamic response. Switch trials thus appeared pseudorandomly either after 4 (15 times), 5 (14 times), or 6 repeat trials (3 times) (i.e., every 9.6, 12, 14.4 sec) to avoid predictability. The 6‐min task consisted of 152 trials with 120 high‐frequency repeat trials (79%) interspersed with 32 low‐frequency switch trials (21%); on average, one in five trials was a switch trial. A rapid mixed trial event‐related fMRI design was used [Dale and Buckner, 1997], allowing a mean ISI of 2.4 sec. The event‐related analysis contrasted activation associated with switch trials with that of repeat trials.

Figure 1.

Illustration of switch task and correct response.

fMRI Image Acquisition and Analysis

Gradient‐echo echoplanar MR imaging (EPI) data were acquired on a GE Signa 1.5T Horizon LX System (General Electric, Milwaukee, WI) retrofitted magnet with Advanced nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) hardware and software (ANMR, Woburn, MA) at the Maudsley Hospital, London. Consistent image quality was ensured by a semiautomated quality control procedure. A quadrature birdcage head coil was used for radio frequency (RF) transmission and reception. In each of 16 non‐contiguous planes parallel to the anterior‐posterior commissure, 152 T2*‐weighted MR images depicting blood oxygen level‐dependent (BOLD) contrast covering the whole brain were acquired (TE = 40 msec, TR = 2.4 sec, flip angle = 90 degrees, in‐plane resolution = 3.1 mm, slice thickness = 7 mm, slice‐skip = 0.7 mm). At the same time, a high‐resolution inversion recovery echo‐planar image of the whole brain was acquired in the intercommissural plane (TE = 40 msec, TI = 180 msec, TR = 16,000 msec, in‐plane resolution = 1.5 mm, slice thickness = 3 mm, slice‐skip = 0.3 mm). This EPI dataset provided almost complete brain coverage.

Individual Analysis

The data were first realigned [Bullmore et al., 1999] to minimize motion‐related artefacts and smoothed using a Gaussian filter (full‐width half‐maximum [FWHM] 7.2 mm). Responses to the experimental paradigms were then detected by time series analysis using γ variate functions (peak responses at 4 and 8 sec) to model the BOLD response. The analysis was implemented as follows. First, each experimental condition was convolved separately with the 4‐ and 8‐sec Poisson functions to yield two models of the expected hemodynamic response to that condition. The weighted sum of these two convolutions that gave the best fit (least‐squares) to the time series at each voxel was then computed. This weighted sum effectively allowed voxel‐wise variability in time to peak hemodynamic response. After this fitting operation, a goodness‐of‐fit statistic was computed at each voxel. This was the ratio of the sum of squares of deviations from the mean intensity value due to the model (fitted time series) divided by the sum of squares due to the residuals (original time series minus model time series). This statistic is called the sum of squares ratio (SSQ) ratio. To sample the distribution of SSQ ratio under the null hypothesis that observed values of SSQ ratio were not determined by experimental design (with minimal assumptions), the time series at each voxel was permuted using a wavelet‐based resampling method described in detail in Bullmore et al. [ 2001]. This process was repeated 10 times at each voxel and the data combined over all voxels, resulting in 10 permuted parametric maps of SSQ ratio at each plane for each subject. The same permutation strategy was applied at each voxel to preserve spatial correlational structure in the data during random assortment. Combining the randomly assorted data over all voxels yielded the distribution of SSQ ratio under the null hypothesis. Voxels activated at any desired level of type I error can then be determined obtaining the appropriate critical value of SSQ ratio from the null distribution. For example, SSQ ratio values in the observed data lying above the 99th percentile of the null distribution have a probability under the null hypothesis of ≤0.01. We have shown that this permutation method gives very good type I error control with minimal distributional assumptions.

Group Mapping

To extend inference to the group level, the observed and randomly assorted SSQ ratio maps were transformed into standard space by a two‐stage process involving first a rigid body transformation of fMRI data into a high‐resolution inversion recovery image of the same subject, followed by an affine transformation onto a Talairach template [Brammer et al., 1997]. By applying the two spatial transformations computed above for each subject to the statistic maps obtained by analyzing the observed and wavelet‐randomized data, a generic brain activation map (GBAM) could be produced for each experimental condition. This GBAM was produced by testing the median observed SSQ ratio over all subjects at each voxel (median values were used to minimize outlier effects) at each intracerebral voxel in standard space [Talairach and Tournoux, 1988] against a critical value of the permutation distribution for median SSQ ratio ascertained from spatially transformed wavelet‐permuted data [Brammer et al., 1997]. To increase sensitivity and reduce the multiple comparison problem encountered in fMRI, hypothesis testing was carried out at the cluster level using the method developed by Bullmore et al. [ 1999], initially for structural image analysis, and subsequently shown to give excellent cluster‐wise type I error control in both structural and functional fMRI analysis. When applied to fMRI data, the method estimated the probability of occurrence of clusters under the null hypothesis using the distribution of median SSQ ratios computed from spatially transformed data obtained from wavelet permutation of the time series at each voxel (see above). Image‐wise expectation of the number of false positive clusters under the null hypothesis was set for each analysis at <1. In this particular analysis, zero false positive activated clusters were expected at a P < 0.01 at both voxel‐ and cluster‐levels.

RESULTS

Performance Data

There were no differences in the success rate of responses to switch trials and repeat trials (mean [SD] switch percentage success, 92.2 [21.8]; repeat success, 92.1 [21.9]; t = −0.11, df = 19, P = 0.92), but there was an effect of response time cost for switch trials, with increased reaction times being associated with switch trials (mean [SD] switch reaction time, 823 [81] msec; repeat reaction time, 721 [70] msec; t = 5.6, df = 19, P = 0.000). These performance data confirmed that all subjects were well able to carry out the task correctly but, as expected, recruited executive attentional processes to a greater degree in switch compared to that in repeat trials, leading to increased response times.

Brain Activation

Switch

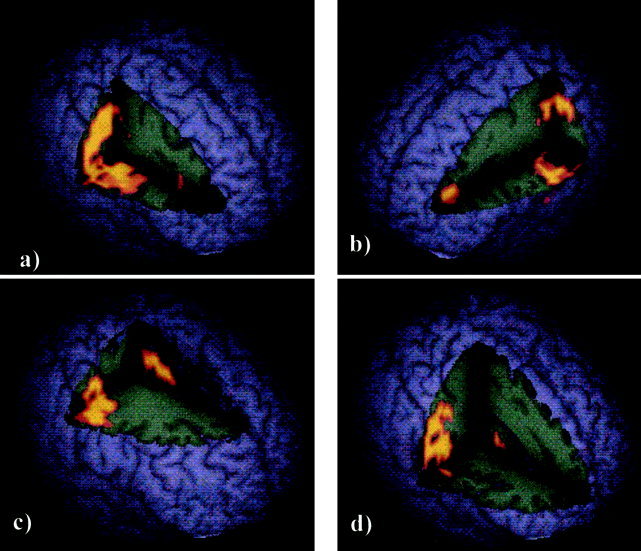

Brain activation correlating with successful switch trials was contrasted with activation correlating with successful repeat trials. The main cluster of activation was observed in the right hemisphere spreading from the borders of the right inferior frontal gyrus, through pre‐ and postcentral gyri, to superior temporal gyrus and inferior parietal lobe. A similarly large but more caudal cluster of activation was seen in the left hemisphere spreading from postcentral gyrus to superior temporal gyrus and inferior parietal lobe. Smaller foci of activation were observed in the SMA and anterior cingulate, in left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and in right putamen (Table I, Fig. 2).

Table I.

Brain areas that showed significant activation in the contrast of dimensional switching trials with repeat trials

| Brain region | Talairach coordinates | Brodmann's area | Voxels (n) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x | y | z | |||

| Right hemisphere | |||||

| Inferior prefrontal/insula/ | 32 | 14 | 9 | 45/6/1/2 | 84 |

| Pre‐ and postcentral gyrus | 46 | −19 | 37 | ||

| Inferior parietal lobe | 46 | −19 | 20 | 40 | 85 |

| Superior temporal lobe | 38 | −8 | 4 | 22 | 70 |

| SMA/Anterior cingulate | 3 | −17 | 48 | 6/24 | 38 |

| Putamen | 39 | 4 | 7 | 6 | |

| Left hemisphere | |||||

| Postcentral gyrus | −38 | −14 | 26 | 1/2/3 | 22 |

| Inferior parietal lobe | −42 | −25 | 33 | 40 | 164 |

| Superior temporal lobe | −43 | −14 | 9 | 22/42 | 18 |

| Medial prefrontal lobe (DLPFC) | −28 | 47 | 17 | 10/46 | 11 |

Figure 2.

Regions of brain activation associated with switch contrasted with repeat trials. a: Whole brain cut away to reveal large activation cluster in the right hemisphere extending from inferior prefrontal lobe, pre‐ and post‐central gyri to middle temporal gyrus. b: Whole brain cut away to reveal activation cluster in the left hemisphere including DLPFC, post‐central gyrus, and superior temporal gyrus. c: Whole brain cut away to reveal activation in anterior cingulate gyrus and right hemispheric precentral and superior temporal activation (also seen in a). d: Whole brain cut away to reveal putamen activation and right hemisphere activation of post‐central gyrus (also seen in a).

Repeat

Brain activation correlating with successful repeat trials when contrasted with activation correlating with successful switch trials was mainly in anterior cingulate and SMA (BA 8/32/6; Talairach coordinates 2/29/39, 145 voxels), with minor foci in left and right medial prefrontal (BA 8; Talairach coordinates left, −38/11/45, 49 voxels; right, 45/15/33, 15 voxels) and orbitofrontal cortices (BA 47; Talairach coordinates left, −30/20/−6, 26 voxels; right, 49/28/2, 21 voxels) and right insula (Talairach coordinates 24/−0/−9, 20 voxels).

DISCUSSION

The event‐related analysis of switching between two spatial dimensions compared to repeat trials showed a widespread activation pattern. The strongest cluster of activation during switch compared to repeat trials was found at the border of right inferior frontal gyrus in pre‐ and postcentral gyrus extending to inferior parietal lobes and superior temporal lobes. A similar, slightly more caudal cluster of activation was observed in homologous left hemisphere brain regions. Further brain regions of activation were seen in left DLPFC, anterior cingulate, SMA, and right putamen.

The extensive activation in pre‐and postcentral gyrus most likely reflects the motor switch component of the task. A diamond‐shaped keypad was used for the button response in the two dimensional directions. When subjects had to switch between the two spatial dimensions, they also had to switch their thumb positions between left/right button position and top/bottom button position. During repeat trials, however, thumb positions remained relatively stable. Besides a cognitive switch between two dimensions, therefore, switch trials also required a motor switch to different thumb positions. An association has been found between right precentral gyrus and the merging of visual and motor coordinates required to produce a hand movement [Iacoboni et al., 1997]. The only other pure switching task carried out previously with event‐related fMRI using a diamond configuration response box that, like the one used in this study, required a change in digit position, also revealed very similar activation in right precentral gyrus [Dove et al., 1999]. In support of this finding, unpredictable compared to fixed sequences of finger motor movements activated precentral gyrus [Jancke et al., 2000].

The strongest activation was in bilateral inferior parietal lobes, with a larger activation cluster in the left hemisphere. This finding was consistent with the literature, because the inferior parietal lobes have been related consistently to cognitive switching within a WCST paradigm [Berman et al., 1995; Lauber et al., 1996; Nagahama et al., 2001], within pure switch tasks [DiGirolamo et al., 2001; Dove et al., 2000; Le et al., 1998], more complex attentional set shifting tasks [Dreher et al., 2002; Gurd et al., 2002; Kimberg et al., 2000; Sohn et al., 2000], and in relation to switching between movements [Jancke et al., 2000]. It is interesting to note that inferior parietal lobe activation turned out to be the strongest activation cluster in a switch task that was designed to keep WM requirements to a minimum. The parietal lobes may have a stronger role than assumed previously for cognitive switching, when other cognitive functions usually co‐measured in switch tasks have been reduced.

SMA and anterior cingulate have also been related previously to task switching [DiGirolamo et al., 2001; Dove et al., 1999, 2000; Konishi et al., 1998, 1999, 2002; Lauber et al., 1996]. The combination of inferior parietal and mesial prefrontal cortex activation has been found to be associated with increased load on a visuospatial attentional network [Baker et al., 1996; Coull et al., 1996; Mesulam et al., 2001; Suchan et al., 2002], which is likely to be in greater demand during switch compared to repeat trials. In particular, a meta‐motor attention function has been attributed to anterior cingulate, which includes response selection [Devinsky et al., 1995; Elliott and Dolan, 1998; Paus et al., 1993; Peterson et al., 1999], conflict processing [Botvinick et al., 1999; Carter et al., 1998], outcome uncertainty [Critchley et al., 2001], and attentional switching between tasks [Dove et al., 1999; Koechlin et al., 1998; Konishi et al., 1998; Lauber et al., 1996; Nagahama et al., 1998, 1999, 2001; Rubia et al., 1998]. Interestingly, Critchley et al. [ 2000] found that blood pressure as a physiologic index of effort correlated with right anterior cingulate activation regardless of the task, which suggests that this region may integrate autonomic states with cognitive demand.

DLPFC activation as seen here has been found often in studies using the WCST [Berman et al., 1995; Fukuyama et al., 1997; Konishi et al., 1998; Lauber et al., 1996; Nagahama et al., 1998, 2001]. As mentioned above, however, the WCST involves many cognitive processes other than switching, such as problem solving and WM [Cepeda et al., 2000], which could account for the DLPFC activation in these studies. The possibility that DLPFC may be associated with WM functions co‐measured in switching tasks was supported by an fMRI study by Monchi et al. [ 2001], where activation during positive feedback (non‐switch trials) was compared to activation during negative feedback (switch trials) within a WCST paradigm. DLPFC activation was seen during feedback on both types of trial, whereas more ventral areas of left and right prefrontal cortex (BA 47/12) together with subcortical structures were activated only with negative feedback, requiring an attentional switch. The authors attributed DLPFC activation to WM because it was required under both conditions in their task, whereas ventral prefrontal activation was associated specifically with switching. In line with this is a study by Konishi et al. [ 1999] who found activation in right and left inferior frontal sulci, (BA 45, 44) and to a lesser degree, right and left supramarginal gyrus (BA 40) and anterior cingulate gyrus (BA 24, 32) in association with switch blocks in the WCST.

The task presented here has attempted to minimize WM function. This may explain why the DLPFC activation is relatively small compared to that seen in previous studies. It also suggests, however, that some left DLPFC activation is in fact associated with pure switching. This extends previous findings of Nagahama et al. [ 1999], where DLPFC was specifically associated with attentional switching, whereas inferior prefrontal cortex was also involved in a shift in instructions. The study used an attentional set shifting task, requiring a shift between color or shape sets, whereas an non‐set shifting task required the subject to indicate whether targets were either the same or a different color to one of two references, thus requiring shifts between two instructions. The two conditions showed similar levels of significant inferior frontal activation and so the authors concluded that activation in this region might be associated with a switch in instruction rather than attentional set. They found significantly increased activation in DLPFC when switching set compared to switching instruction and concluded that this may be the location associated specifically with attentional shift [Nagahama et al., 1998, 1999]. This finding was later supported by a replication of the same study [Nagahama et al., 2001] where both instruction shifting conditions and set shifting conditions produced common activation in right inferior and DLPFC, but a peak of activation in DLPFC was seen only in the set shifting condition. What made this conclusion problematic is that in this study there was a potential confounding variable of WM load, because set shifting in their task design probably required more WM than did instruction shifting. The switch task used in this study was designed specifically to optimally minimize WM functions. Our finding of left DLPFC activation under conditions where switching processes are isolated is therefore in line with the hypothesis that DLPFC activation is related directly to a switching function. This also supports recent findings of Luks et al. [ 2002] and Sohn et al. [ 2000], who found significantly more DLPFC activation for unpredictable compared to predictable switch trials. Because WM may be assumed to be comparable in these two conditions, DLPFC activation might be attributable to a central role within the switching process, which in this case the authors define as attentional control, to activate new tasks under conditions of uncertainty.

Interestingly, DLPFC activation found in this study, like that observed in Lauber et al. [ 1996], was seen in the left hemisphere, although most studies have shown right DLPFC activation [Berman et al., 1995; Fukuyama et al., 1997; Monchi et al., 2001; Nagahama et al., 1998, 1999, 2001]. As well as left DLPFC, we also found activation of right inferior prefrontal cortex. Activation in this region related to isolated switching processes where WM has been kept to a minimum has been found by others [DiGirolamo et al., 2001; Dove et al., 1999, 2000]. Interestingly, Konishi et al. [ 2002] suggested that middle and inferior frontal gyri in the left hemisphere might be involved in the updating of cognitive set, whereas homologous areas in the right hemisphere could be associated with inhibition. Set switching involves inhibition of previous stimulus‐response associations to change to newly defined ones. In support of this finding, right inferior prefrontal cortex has been shown to be involved in motor inhibition in go/no‐go and stop tasks [Rubia et al., 2001]. Furthermore, a recent study that aimed to isolate successful inhibitory control from other non‐inhibitory functions usually co‐measured in inhibition tasks, found right inferior prefrontal cortex to emerge as the crucial brain region for inhibitory motor control [Rubia et al., 2003]. Although switching is a more cognitive form of inhibitory control compared to motor response inhibition, both motor and cognitive inhibitory control could be mediated by the same brain regions. In fact, Konishi et al. [ 1999] found identical right inferior prefrontal activation focus in a go–no/go and a WCST task, suggesting a common neural mechanism for cognitive and motor inhibition.

The superior temporal cortex activation seen here connecting parietal and pre‐ and postcentral cortices within each hemisphere is associated probably with preparation of potential action [Passingham and Toni, 2001; Thoenissen et al., 2002; Toni et al., 2002], which is likely to be stronger in switch trials. Within a go/no–go paradigm, where required responses were preceded by cues that allowed the subject to predict with varying levels of confidence a given outcome, superior temporal gyrus was activated where a required motor response breached the predominant rule given by the preceding cue [Thoenissen et al., 2002]. Passingham and Toni [ 2001] describe a stimulus‐response network as spreading from temporal cortex, where the stimulus is assessed, to parietal and precentral cortex where action is selected. It seems likely that this network will show stronger activation under switching conditions where the predominant action pattern is challenged. Furthermore, superior temporal brain regions have also been found to be activated in oddball tasks [Alho et al., 1998; Jemel et al., 2002] suggesting a role for temporal lobe in mediating selective attention. It is likely that the dimensional switching during the switch trials required a higher load on selective attention compared to that in the repeat trials.

Of interest in this study is the activation found in right putamen during switch trials. Activation of the basal ganglia has been found by other studies involving switching [DiGirolamo et al., 2001; Dove et al., 1999; Monchi et al., 2001]. This finding is in line with the association found between poor performance upon the WCST and reduced striatal volume in a sample of schizophrenic subjects [Stratta et al., 1997]. Woodward et al. [ 2002] also showed that Parkinsonism patients with damage to the basal ganglia demonstrated deficits in the switching component of an adapted switch‐Stroop task. It has been suggested that the basal ganglia are responsible for the generation of cognitive and motor patterns that serve to organize neural activity underlying aspects of action‐oriented cognition [Graybiel, 1997; Menon et al., 2000]. This kind of function is more likely required during switch trials, where change in action is required, rather than during repeat trials where a constant action required. It has even been proposed by Passingham and Toni [ 2001] that if subjects are overtrained in response selection tasks, inferior prefrontal activation may be reduced or even disappear and actions might be guided instead by basal ganglia and inferotemporal cortex, which may explain the small focus of inferior frontal activation seen in this study.

Brain activation related to task repetition was mainly in SMA and anterior cingulate, with additional foci in bilateral medial and orbital prefrontal cortices reaching the insula in the right hemisphere. The findings of SMA, prefrontal, and insula activation for repeat trials are very similar to the activation foci for task repetition in the study of Dove et al. [ 1999]. Contrary to the study of Dove et al. [ 1999], we did not find that the same brain regions involved in switching were also involved in task repetition, only to a greater extent in switch trials. We found that different brain regions were activated in switching compared to task repetition. The main focus of activation for task switching in pre‐ and postmotor, superior temporal, and parietal brain regions was not observed during the repetition trials. Furthermore, the focus in anterior cingulate during switch trials was in a more dorsal location compared to the relatively ventral anterior cingulate region activated during task switching. Likewise, the orbital prefrontal activation during task repetition was in a more ventral location compared to the inferior prefrontal activation during switching, whereas the medial prefrontal activation during the repeat trials was more dorsal compared to the rostro‐lateral location observed during switch trials. It thus seems that within the prefrontal cortex, different parts are involved in task switching compared to task repetition whereas posterior frontal, temporal, and parietal brain regions are exclusively involved in task switching.

CONCLUSIONS

We combined event‐related fMRI with a pure switching task requiring cognitive switching between two spatial dimensions. The main brain regions related to task switching were in bilateral pre‐ and postcentral, inferior parietal, and temporal brain regions, although some minor activation foci were observed in left DLPFC, right inferior prefrontal cortex, anterior cingulate gyrus, and right putamen. We speculate that the cognitive shift was mediated by left DLPFC and bilateral posterior parietal and temporal cortices, right putamen, SMA, and anterior cingulate gyrus. The strong bilateral activation in pre‐ and postcentral gyri may be related to uncontrolled motor components of the dimensional switching required by the task.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by a grant from the Wellcome Trust.

REFERENCES

- Alho K, Connolly JF, Cheour M, Lehtokoski A, Huotilainen M, Virtanen J, Aulanko R, Ilmoniemi RJ ( 1998): Hemispheric lateralization in preattentive processing of speech sounds. Neurosci Lett 258: 9–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker SC, Frith CD, Frackowiak RSJ, Dolan RJ ( 1996): The neural substrate of active memory for shape and spatial location in man. Cereb Cortex 6: 612–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg EA ( 1948): A simple objective technique for measuring flexibility of thinking. J Gen Psychol 39: 15–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman KF, Ostrem JL, Randolph C, Gold J, Goldberg TE, Coppola R, Carson RE, Herscovitch P, Weinberger DR ( 1995): Physiological activation of a cortical network during performance of the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test: a positron emission tomography study. Neuropsychologist 33: 1027–1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botvinick M, Nystrom L, Fissell K, Carter CS, Cohen JD ( 1999): Conflict monitoring versus selection for action in anterior cingulate cortex. Nature 402: 179–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brammer MJ, Bullmore ET, Simmons A, Williams SC, Grasby PM, Howard RJ, Woodruff PW, Rabe‐Hesketh S ( 1997): Generic brain activation mapping in functional magnetic resonance imaging: a nonparametric approach. Magn Reson Imaging 15: 763–770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullmore E, Long C, Suckling J, Fadili J, Calvert G, Zelaya F, Carpenter TA, Brammer M ( 2001): Colored noise and computational inference in neurophysiological (fMRI) time series analysis: resampling methods in time and wavelet domains. Hum Brain Mapp 12: 61–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullmore ET, Suckling J, Overmeyer S, Rabe‐Hesketh S, Taylor E, Brammer MJ ( 1999): Global, voxel, and cluster tests, by theory and permutation, for a difference between two groups of structural MR images of the brain. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 18: 32–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter C, Braver TS, Barch DM, Botvinick MM, Noll D, Cohen JD ( 1998): Anterior cingulate cortex, error detection and the on‐line monitoring of performance. Science 280: 747–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cepeda NJ, Cepeda ML, Kramer AF ( 2000): Task switching and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Abnorm Child Psychol 28: 213–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coull JT, Frith CD, Frackowiak RS, Grasby PM ( 1996): A fronto‐parietal network for rapid visual information processing: a PET study of sustained attention and working memory. Neuropsychologia 34: 1085–1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Critchley HD, Mathias CJ, Dolan RJ ( 2001): Neural activity in the human brain relating to uncertainty and arousal during anticipation. Neuron 29: 537–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Critchley HD, Corfield DR, Chandler MP, Mathias CJ, Dolan RJ ( 2000): Cerebral correlates of autonomic cardiovascular arousal: a functional neuroimaging investigation in humans. J Physiol 523: 259–270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale AM, Buckner RL ( 1997): Selective averaging of rapidly presented individual trials using fMRI. Hum Brain Mapp 5: 329–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devinsky O, Morrell MJ, Vogt BA ( 1995): Contributions of anterior cingulate cortex to behaviour. Brain 118: 279–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiGirolamo GJ, Kramer AF, Barad V, Cepeda NJ, Weissman DH, Milham MP, Wszalek TM, Cohen NJ, Banich MT, Webb A, Belopolsky AV, McAuley E ( 2001): General and task‐specific frontal lobe recruitment in older adults during executive processes: a fMRI investigation of task‐switching. Neuroreport 12: 2065–2071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dove A, Schubert T, Pollmann S, Norris D, von Cramon DY ( 1999): Event related fMRI of task switching. Neuroimage 9( Suppl): 332. [Google Scholar]

- Dove A, Pollmann S, Schubert T, Wiggins CJ, von Cramon DY ( 2000): Prefrontal cortex activation in task switching: an event‐related fMRI study. Brain Res Cogn Brain Res 9: 103–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreher JC, Koechlin E, Ali SO, Grafman J ( 2002): The roles of timing and task order during task switching. Neuroimage 17: 95–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott R, Dolan RJ ( 1998): Activation of different anterior cingulate foci in association with hypothesis testing and response selection. Neuroimage 8: 17–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friston KJ, Fletcher P, Josephs O, Holmes A, Rugg MD, Turner R ( 1998): Event‐related fMRI: characterizing differential responses. Neuroimage 7: 30–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuyama H, Nagahama Y, Sadato N, Yonekura Y, Shibasaki H ( 1997): Relationship of the set‐shifting rate with the cerebral blood flow activation in the prefrontal cortex. Neuroimage 5( Suppl): 91. [Google Scholar]

- Graybiel AM ( 1997): The basal ganglia and cognitive pattern generators. Schizophr Bull 23: 459–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurd JM, Amunts K, Weiss PH, Zafiris O, Zilles K, Marshall JC, Fink GR ( 2002): Posterior parietal cortex is implicated in continuous switching between verbal fluency tasks: an fMRI study with clinical implications. Brain 125: 1024–1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacoboni M, Wood RP, Lenzi GL, Mazziotta JC ( 1997): Merging of the oculomotor and somatomotor space coding in human right precentral gyrus. Brain 120: 1635–1645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jancke L, Himmelbach M, Jon Shah N, Zilles K ( 2000): The effect of switching between sequential and repetitive movements on cortical activation. Neuroimage 12: 528–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jemel B, Achenbach C, Muller BW, Ropcke B, Oades RD ( 2002): Mismatch negativity results from bilateral asymmetric dipole sources in the frontal and temporal lobes. Brain Topogr 15: 13–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimberg DY, Aguirre GK, D'Eposito M. ( 2000): Modulation of task‐related neural activity in task‐switching: an fMRI study. Brain Res Cogn Brain Res 10: 189–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koechlin E, Basso G, Pietrini P, Panzer S, Grafman J ( 1998): Maintenance, switching and branching: charting the functional topography of the prefrontal cortex with fMRI. Neuroimage 7( Suppl): 13. [Google Scholar]

- Konishi S, Hayashi T, Uchida I, Kikyo H, Takahashi E, Miyashita Y ( 2002): Hemispheric asymmetry in human lateral prefrontal cortex during cognitive set shifting. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99: 7803–7808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konishi S, Nakajima K, Uchida I, Kikyo H, Kameyama M, Miyashita Y ( 1999): Common inhibitory mechanism in human inferior prefrontal cortex revealed by event‐related functional MRI. Brain 122: 981–991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konishi S, Nakajima K, Uchida I, Kameyama M, Nakahara K, Sekihara K, Miyashita Y ( 1998): Transient activation of inferior prefrontal cortex during cognitive set shifting. Nature Neuroscience 1: 80–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauber EJ, Meyer DE, Evans JE, Rubinstein J, Gmeindl L, Junck L, Koeppe RA ( 1996): The brain areas involved in the executive control of task switching as revealed by PET. Neuroimage 3( Suppl): 247. [Google Scholar]

- Le TH, Pardo JV, Ziaoping H ( 1998): 4T fMRI study of nonspatial shifting of selective attention: cerebellar and parietal contributions. J Neurophysiol 79: 1535–1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luks TL, Simpson GV, Feiwell RJ, Miller WL ( 2002): Evidence for anterior cingulate cortex involvement in monitoring preparatory attentional set. Neuroimage 17: 792–802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meiran N ( 1996): Reconfiguration of processing mode prior to task performance. J Exp Psychol Learn Mem Cogn 22: 1423–1442. [Google Scholar]

- Menon V, Anagnoson RT, Glover GH, Pfefferbaum A ( 2000): Basal ganglia involvement in memory‐guided movement sequencing. Neuroreport 11: 3641–3645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesulam MM, Nobre AC, Kim YH, Parrish TB, Gitelman DR ( 2001): Heterogeneity of cingulate contributions to spatial attention. Neuroimage 13: 1065–1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milner B ( 1963): Effects of different brain lesions of card sorting. Arch Neurol 9: 90–100. [Google Scholar]

- Monchi O, Petrides M, Petre V, Worsley K, Dagher A ( 2001): Wisconsin Card Sorting revisited: distinct neural circuits participating in different stages of the task identified by event‐related functional magnetic resonance imaging. J Neurosci 21: 7733–7741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagahama Y, Okada T, Yamauchi H, Katsumi Y, Hayashi T, Fukuyama H, Shibasaki H ( 1999): Transient activity in the inferior frontal sulci may not be specific to attention set shift. Neuroimage 9( Suppl): 759. [Google Scholar]

- Nagahama Y, Okada T, Katsumi Y, Hayashi T, Yamauchi H, Oyanagi C, Konishi J, Fukuyama H, Shibasaki H ( 2001): Dissociable mechanisms of attentional control within the human prefrontal cortex. Cereb Cortex 11: 85–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagahama Y, Sadato N, Yamauchi H, Katsumi Y, Hayashi T, Fukuyama H, Kimura J, Yonekura Y ( 1998): Neural activity during attention shifts between object features. Neuroreport 9: 2633–2638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Reilly RC, Noelle DC, Braver TS, Cohen JD ( 2002): Prefrontal cortex and dynamic categorization tasks: representational organization and neuromodulatory control. Cereb Cortex 12: 246–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passingham RE, Toni I ( 2001): Contrasting the dorsal and ventral visual systems: guidance of movement versus decision making. Neuroimage 14( Suppl): 125–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paus T, Petrides M, Evans AC, Meyer E ( 1993): Role of the human anterior cingulate cortex in the control of oculomotor, manual, and speech responses: a positron emission tomography study. J Neurophysiol 70: 453–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson BS, Skudlarski P, Gatenby JC, Zhang H, Anderson AW, Gore JC ( 1999): An fMRI study of Stroop word‐color interference: evidence for cingulate subregions subserving multiple distributed attentional systems. Biol Psychiatry 45: 1237–1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raven J, Raven JC, Court JH ( 1998): Manual for Raven's progressive matrices and vocabulary scales, section 3. The standard progressive matrices. San Antonio, Texas: The Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Rougier NP, O'Reilly RC ( 2002): Learning representations in a gated prefrontal cortex model of dynamic task switching. Cogn Sci 26: 503–520. [Google Scholar]

- Rubia K, Smith AB, Brammer MJ, Taylor E ( 2003): Right inferior prefrontal cortex mediates response inhibition while mesial prefrontal cortex is responsible for error detection. Neuroimage 20: 351–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubia K, Russell T, Overmeyer S, Brammer M, Bullmore E, Sharma T, Simmons A, Williams S, Giampietro V, Andrew C, Taylor E ( 2001): Mapping motor inhibition: conjunctive brain activations across different versions of go/no‐go and stop tasks. Neuroimage 13: 250–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubia R, Overmeyer S, Taylor E, Brammer M, Williams S, Simmons A, Andrew C, Bullmore E ( 1998): Prefrontal involvement in “temporal bridging” and timing movement. Neuropsychologia 36: 1283–1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohn MH, Ursu S, Anderson JR, Stenger VA, Carter CS ( 2000): The role of prefrontal cortex and posterior parietal carter in task switching. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 13448–13453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stratta P, Mancini F, Mattei P, Daneluzzo E, Casacchia M, Rossi A ( 1997): Association between striatal reduction and poor Wisconsin card sorting test performance in patients with schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry 42: 816–820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuss DT, Levine B, Alexander MP, Hong J, Palumbo C, Hamer L, Murphy KJ, Izukawa D ( 2000): Wisconsin Card Sorting Test performance in patients with focal frontal and posterior brain damage: effects of lesion location and test structure on separable cognitive processes. Neuropsychologia 38: 388–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suchan B, Yaguez L, Wunderlich G, Canavan AG, Herzog H, Tellmann L, Homberg V, Seitz RJ ( 2002): Neural correlates of visuospatial imagery. Behav Brain Res 131: 163–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talairach J, Tournoux P ( 1988): Co‐planar stereotaxic atlas of the brain. New York: Thieme. [Google Scholar]

- Thoenissen D, Zilles K, Toni I ( 2002): Differential involvement of parietal and precentral regions in movement preparation and motor intention. J Neurosci 22: 9024–9034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toni I, Shah NJ, Fink GR, Thoenissen D, Passingham RE, Zilles K ( 2002): Multiple movement representations in the human brain: an event‐related fMRI study. J Cogn Neurosci 14: 769–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodward TS, Bub DN, Hunter MA ( 2002): Task switching deficits associated with Parkinson's disease reflect depleted attentional resources. Neuropsychologia 40: 1948–1955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]