Abstract

The participation of the inferior temporal cortex in visual word perception and recognition raises several questions: Is there a directed processing stream proceeding anteriorly by continuous cortical processing? How fast are words processed within such an inferior temporal stream? Does this stream support implicit or explicit memory? To answer these questions, we analyzed the spatio‐temporal relationship of event‐related potentials, recorded directly from the inferior temporal cortex in epilepsy patients performing a continuous visual word recognition paradigm. Event‐related potentials elicited an inferior temporal positivity in a strip along the left collateral sulcus. This potential exhibited a linear (r = 0.74) peak latency progression from posterior to anterior inferior temporal regions (≈15 cm/sec), indicating a directed, intracortical processing stream. Peak amplitudes and latencies showed reliable old/new effects with smaller amplitudes and shorter latencies for old as opposed to new words. Although the amplitude‐old/new‐effect occurred for all repeated words (e.g., implicit memory), the latency‐old/new‐effect occurred for correctly recognized old words only (e.g., explicit recognition). These results seem to dissociate two distinct mnemonic processes. The graded decrease of mean ITP peak amplitudes and latencies, however, does not allow us to exclude a single trace model as assumed for explicit recognition memory based on familiarity (Mandler [1980]: Psychol Rev 87:252–271). Regardless whether there is a dissociation between implicit and explicit memory in inferior temporal cortex or not, our findings are in accordance with an integrated inferior temporal processing stream for words that performs continuously semantic and mnemonic operations supporting both implicit and explicit memory. Hum. Brain Mapping 14:251–260, 2001. © 2001 Wiley‐Liss, Inc.

Keywords: memory, ERP, recognition, priming, human

INTRODUCTION

The inferior temporal (IT) cortex is the final route of the ventral visual pathway, analyzing visually perceived object features hierarchically, from simple features in occipital cortex to progressively more complex features in anterior IT regions [Ungerleider and Mishkin, 1982]. Such a pathway has been confirmed in humans [Haxby et al., 1991; Lerner et al. 2001], and polymodal verbal processing seems to be part of that pathway in the language dominant hemisphere [Büchel et al., 1998].

Intracranial recordings of event‐related potentials (ERPs) in patients with epilepsy have made important contributions to the investigation of IT processes in humans due to their high anatomical specificity, optimal temporal resolution, and favorable signal‐to‐noise ratio. For instance, intracranial ERP data has been interpreted as showing two functional nodes of word processing within the ventral visual pathway. A presemantic, perceptual node has been identified in the inferior occipital cortex by Nobre et al. [1994], which preferentially processes words and non‐word letter strings. It does not differentiate, however, between these two types of stimuli or between words differing by their novelty or semantic category (e.g., content words versus grammatical function words). This presemantic operation of word form perception is electrophysiologically characterized by a negative field potential peaking at about 170 to 200 msec (N200) after stimulus onset [Allison et al., 1994; Nobre et al., 1994, 1998]. A second word specific node was thought to be located in anterior IT cortex and characterized by a distinct ERP component with a positive polarity, henceforth called inferior temporal positivity (ITP) [Allison et al., 1999; Elger et al., 1997; Fernández et al., 1999; Grunwald et al., 1995, 1998a; Halgren et al., 1994; McCarthy et al., 1995; Nobre et al., 1994; Nobre and McCarthy, 1995; Smith et al., 1986]. The ITP reflects semantic as well as mnemonic processing. It shows highly variable peak latencies across subjects and studies ranging from 190 to 460 msec [Allison et al., 1999; Elger et al., 1997; Fernández et al., 1999; Grunwald et al., 1995, 1998a; Halgren et al., 1994; McCarthy et al., 1995; Nobre et al., 1994; Nobre and McCarthy, 1995; Smith et al., 1986], calling the idea of one circumscribed node operating at a certain point in space and time into question. ITP shows a local polarity inversion in depth recordings from within the anterior parahippocampal gyrus, just opposite to the cortical layer. This negativity is called anterior medial temporal lobe N400 (AMTL‐N400) [McCarthy et al., 1995], and the polarity inversion indicates that the ITP and the AMTL‐N400 have a common and local generator, probably within the perirhinal cortex [McCarthy et al., 1995], which mainly covers the anterior half of the collateral sulcus [Amaral and Insausti, 1990].

The identification of an early ERP component related to visuo‐perceptual processing and a later component related to semantic processing indicates that word form perception is accomplished earlier in the inferior occipital region than semantic‐conceptual processing in IT cortex. As noted by Nobre et al. [1994], it remains unclear whether additional nodes in language specific regions of the dominant superior temporal lobe may be interposed between these two nodes. As an alternative explanation, they proposed a continuous pathway within the ventral visual stream, which allows direct access to perceptual and conceptual representations. The large variability of ITP peak latencies (≈190–460 msec) may indicate the existence of several generators, whose successive activity contributes to a processing stream proceeding anteriorly from posterior to anterior IT regions.

To test this hypothesis, one would need ITP recordings from different points along the posterior‐anterior IT axis and a correlation between ITP peak latencies and the anatomical localization of their recording site. So far, several studies have recorded ITPs related to words, but they have not analyzed the temporal‐spatial relationship of the recorded potentials [Allison et al., 1999; Elger et al., 1997; Fernández et al., 1999; Grunwald et al., 1995, 1998a; Halgren et al., 1994; McCarthy et al., 1995; Nobre et al., 1994; Nobre and McCarthy, 1995; Smith et al., 1986]. The primary goal of this study was to answer the question whether the ITP characterizes a posterior‐anterior processing stream connecting posterior with anterior IT regions and to estimate the speed of such a presumed processing stream.

A secondary goal was to elucidate whether this stream supports explicit recognition memory, implicit memory or both [Graf and Schacter, 1985]. In monkeys and humans, IT neurons respond maximally to the first presentation of a given stimulus, but less so to its repetition [Brown, 1996; Buckner and Koutstaal, 1998; Desimone, 1996; Miller et al., 1991]. The behavioral correlate of this repetition suppression effect has not been well defined yet.

It has been repeatedly shown that the ITP and the AMTL‐N400 exhibit repetition suppression effects, they have smaller amplitudes for correctly recognized old than new items in explicit recognition memory tasks [Elger et al., 1997; Grunwald et al., 1998a; Guillem et al., 1995, 1999; Heit et al., 1988, 1990; Nobre et al., 1994; Puce et al., 1991; Smith et al., 1986]. No study, however, has differentiated between simple repetition effects, which might be related to implicit memory and effects specifically correlated with explicit recognition memory [Rugg et al., 1998; Rugg and Nagy, 1989]. Moreover, the AMTL‐N400 is as well smaller in amplitude for primed than unprimed items in a semantic categorization task [Nobre and McCarthy, 1995], supporting the idea of a relation between IT activity and implicit memory. Thus, it remains unclear whether the repetition suppression effect of the ITP reflects a correlate of explicit or implicit memory.

In general, one influential view of the repetition suppression effect of IT neurons is that it indicates repetition priming, a form of implicit memory, making stimulus processing more efficient but not enabling explicit, conscious recognition [Buckner and Koutstaal, 1998]. In monkeys, however, correct recognition is associated with IT‐repetition suppression effects [Brown, 1996]. These tasks, however, might be solved by stimulus familiarity [Aggleton and Brown, 1999; Li et al., 1993]. In human neuropsychology, familiarity implies a conscious feeling of knowing that an item has been experienced before without remembering any contextual detail [Mandler, 1980]. We can neither confirm nor refute conscious awareness in nonhuman animals, however, and hence, we can draw no conclusion from animal experiments about the question whether or not less IT activity for repeated rather than novel items supports a conscious form of memory in humans.

A straightforward way of dissociating explicit and implicit memories uses event related brain responses during a recognition memory test and conducts two contrasts: One between responses to new items and old items recognized correctly (explicit memory) and another between new items and old items misclassified as new (implicit memory) [Rugg et al., 1998]. These contrasts based on ITP measures may provide initial insights into the issue whether the presumed IT processing stream supports explicit recognition memory, implicit memory or both.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

We analyzed ERP data sets of 48 patients (26 women, mean age: 30 ± 8.87 years) with well defined ITPs in left IT recordings. All patients had medically intractable epilepsy (mean duration of illness: 11 ± 8.9 years) and were being evaluated for possible surgery. Because seizure onset could not be determined unequivocally by noninvasive investigations, electrodes were implanted according to clinical requirements. The ERP investigation, employing a continuous visual word recognition paradigm [Rugg and Nagy, 1989], is part of our presurgical work‐up, providing predictors of seizure control and verbal memory performance after temporal lobe surgery [Grunwald et al., 1998b; 1999a]. All patients were right hand dominant (self‐reported) and native German speakers. At the time of the investigation, they received only one anticonvulsive drug, almost invariably carbamazepine, with plasma levels within the so‐called therapeutic range. No other centrally acting drug was administered and no seizure had occurred within 24 hr before the investigation.

Electrode Placement

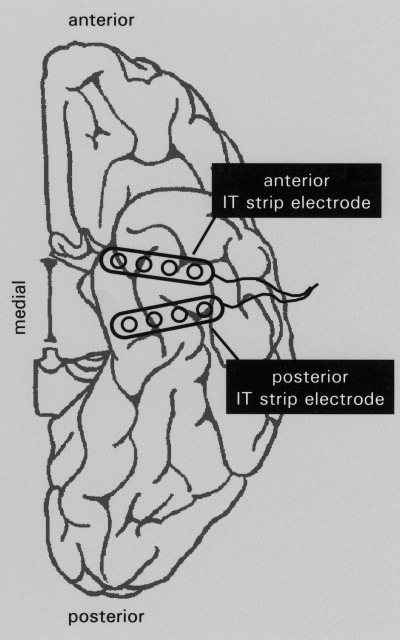

We used silastic strip electrodes carrying four contacts in line over a distance of 3 cm (AD Tech Medical Instrument Corp., Racine, WI). After induction of general anesthesia the electrode placement was performed according to clinical requirements in individual patients (Fig. 1). Bilaterally, a linear, vertical incision was made in front of the ear and an enlarged burrhole of about 9 × 18 mm was placed on the temporal squama superior to the root of the zygoma. After opening of the dura, a first (posterior) electrode was introduced perpendicularly to the longitudinal axis of the temporal lobe, sliding over its inferior surface, with the electrode tip reaching the medial part of the temporal lobe. Secondly, at an angle of about 45° to the posterior electrode, an anterior electrode was passed over the anterior aspect of the IT lobe. Finally, the dura was loosely adapted and the electrodes were anchored to the scalp to allow a non‐surgical removal after recording sufficient ictal EEG activity. Invasive monitoring lasted 1 to 2 weeks. Because of bridging veins or brain‐dura adhesions, electrodes experience deviations from their intended paths and their actual position exhibits considerable variability across patients as shown by routinely performed postoperative CT or MR images.

Figure 1.

Schematic drawing showing posterior and anterior IT strip electrodes in place carrying four contacts each. Note that the actual position of electrodes exhibits a wide variability across patients.

Experimental Paradigm

In a continuous visual word recognition paradigm [Rugg and Nagy, 1989], 300 common German nouns were presented sequentially in uppercase letters (white against black background), in central vision (horizontal visual angle 3.0°), and for a duration of 200 msec (randomized interstimulus interval: mean: 1,800 msec, range: 1,400–2,200 msec). Half of these words were repeated after 3 ± 1 (early) or 14 ± 4 (late) intervening stimuli. Patients were asked to indicate whether an item was new or old by pressing one of two buttons of a computer mouse in their dominant hand. Because earlier studies have revealed no reliable differences between ERPs to early and late repetitions in medial IT recordings [Grunwald et al., 1998a; Guillem et al., 1999], averages were collapsed across both lags for the present analysis.

ERP Recording and Analysis

ERP recordings were obtained concurrently with EEG and behavioral video recording used to determine the localization and behavioral correlates of seizure onset. EEG was referenced to linked mastoids, bandpass‐filtered (0.03 to 85 Hz, 6 dB per octave), and recorded with a sampling rate of 173 Hz (12‐bit analog‐digital conversion). Each averaging epoch lasted 1.2 sec, including 0.2 sec before stimulus onset. ERPs were quantified with respect to the prestimulus baseline as peak amplitudes and with respect to stimulus onset as peak latencies of a well defined positivity recorded by anterior or posterior IT strip electrodes. Positivities occurring between 100 and 600 msec, with amplitudes of at least 20 μV and 100% larger amplitudes than the envelope of the remaining ERP were regarded as well defined. Because of volume conduction, adjacent electrode contacts within the same strip electrode (medial‐lateral axis) may have partially sampled the same neural activity. Therefore, if adjacent contacts within the same strip electrode recorded ITPs also, only measurements from the contact exhibiting the largest ITP amplitude were entered into our analysis.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging: Acquisition and Analysis

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed on a 1.5 T scanner (Gyroscan ACS‐II, Philips Medical Systems, Best, The Netherlands). Patients were studied after electrode insertion with a standardized protocol including sagittal T1‐weighted spin echo (repetition time: 650 msec; echo time: 16 msec; number of slices: 19; slice thickness: 5 mm; interslice gap: 0.5 mm), axial FLAIR (inversion time 1,900 msec/6,000/21/5/1), axial T2‐weighted fast spin echo (2,876/120/21/5/1), axial T1‐weighted spin echo (500/12/21/5/1), and coronal T2‐weighted fast spin echo (3,719/120/29/2/0.3) sequences. Slices were routinely angulated along (axial) or perpendicular (coronal) to the longitudinal axis of the IT plane.

To correlate electrode localizations across subjects with ITP peak latencies, it was necessary to determine the actual localization of each electrode contact along the anterior‐posterior IT axis. Following the suggestion made by Amaral and Insausti [1990] for the localization of certain anatomical areas in human IT cortex, we measured the anterior‐posterior distance between each electrode and the orthogonal projection of the temporal tip onto the IT plane after transforming the images into an averaged brain of the patient sample. In the medial‐lateral axis, localizations were not measured, they were plotted according to their actual position in relation to sulci and gyri, because there was considerable across subject variation in the configuration of sulci and gyri leading to errors in apparent electrode localization.

RESULTS

Within Subject Analyses

For within subject analysis it was necessary to have anterior and posterior ITP recordings. In 22 patients (14 women, mean age: 34 years, range: 15–52 years), recordings from both left posterior and anterior strip electrodes exhibited well defined ITPs. On average, these patients classified 220 of 300 new words (73.3 ± 21.6%) and 102 of 150 old words (68.0 ± 18.6%) correctly.

Peak Latency

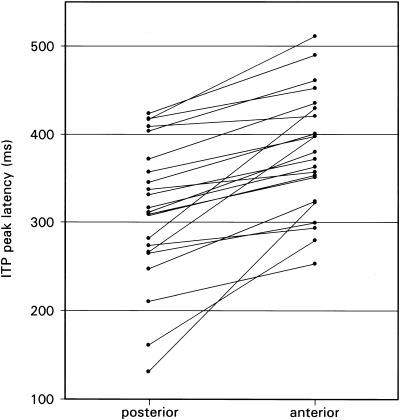

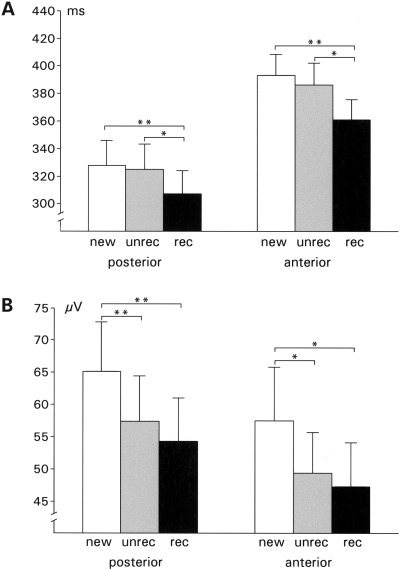

Within each and every patient, mean peak latencies of the ITP were shorter for recordings from the posterior than from the anterior strip electrode (mean difference: 60.3 ± 45.8 msec; Fig. 2). A two‐way repeated measure ANOVA of peak‐latencies with the factors of memory (new vs. unrecognized old vs. recognized old) and localization (anterior vs. posterior) revealed reliable main effects for each factor (memory: F(2,20) = 18.55, P < 0. 0001; localization: F(1,21) = 38.09, P < 0. 0001), but no interaction between the two (F < 1, NS). In posterior and anterior recordings (Fig. 3), ERPs exhibited shorter peak latencies to correctly classified old words than to genuinely new words (posterior: t = 4.1, P < 0.001; anterior: t = 4.7, P < 0. 0001) as well as to old words misclassified as new ones (posterior: t = 2.4, P < 0.05; anterior: t = 2.3, P < 0.05). In contrast, peak latencies did not differ significantly between ERPs to old words misclassified as new and genuinely new words (posterior: t < 1, NS; anterior: t < 1, NS).

Figure 2.

Diagram relating ITP peak latencies with electrode localization within subjects (n = 22).

Figure 3.

Within subject analysis (n = 22): Mean ITP peak latencies (A) and peak amplitudes (B) with the standard error of the mean of ERPs to correctly classified new words (white bars), misclassified old words (gray bars), and correctly classified old words (black bars). Data are shown separately for recordings from posterior (left group) and anterior (right group) strip electrodes. Significant differences of the means (paired sample t‐test) are indicated by brackets (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.001).

These findings confirm a reliable posterior‐anterior latency increase, indicating a sequential processing wave from posterior to anterior IT regions, and longer ITP peak latencies for words classified as new, regardless of the correctness of classification than for words correctly classified as old.

Peak Voltage

Comparing peak voltages with a two‐way repeated measure ANOVA (memory: new vs. unrecognized old vs. recognized old × localization: anterior vs. posterior) revealed a reliable main effect of the factor memory (F(2,20) = 9.42, P < 0.001). Subsidiary, paired sample t‐tests confirmed larger ITP amplitudes to initially presented as opposed to repeated words regardless of the correctness of the recognition judgment in posterior as well as anterior recordings (posterior: new vs. unrecognized old: t = 4.1, P < 0.001; new vs. recognized old: t = 3.9, P < 0.001; anterior: new vs. unrecognized old: t = 2.8, P < 0.05; new vs. recognized old: t = 3.3, P < 0.01). These results confirm a reliable old/new effect, but this old/new effect occurred irrespective of the fact whether the patient was able to recognize the old item or not.

The electrode localization along the posterior‐anterior axis did neither influence ITP amplitudes in general (main effect localization: F < 2, NS) nor the amplitude of old/new effects (memory × localization interaction: F < 0.1, NS). Hence, similar amounts of perceptual/semantic and mnemonic operations seemed to occur in posterior and anterior IT cortex.

Across Subject Analyses

Several recordings sites covering the posterior‐anterior axis would be necessary to estimate the speed of the process indexed by the ITP. Our patients, however, did not receive more than one anterior and one posterior strip electrode in each hemisphere. Therefore, the progress of the ITP along the IT surface could not be studied in individuals. To gain more insight into the temporo‐spatial dynamics of posterior to anterior ITP spread, we performed an across subject analysis in a highly homogeneous sample. To reduce poorly controllable effects on ERP latencies introduced by the seizure origin zone [Elger et al., 1997; Grunwald et al., 1995, 1999b; Guillem et al., 1995; Puce et al., 1989], we selected patients with an epileptic focus within the right hemisphere who remained seizure‐free after resection of this focus (mean follow‐up: 43 months, range: 25–59 month). Complete seizure control after right temporal lobe surgery served as proof of the fact that the left temporal lobe investigated here was unaffected by epilepsy. Furthermore, data sets without documentation of electrode localization by MRI were excluded (n = 2). In our department, electrodes are much more often implanted in patients with an epileptic focus in the left than in the right hemisphere, because left temporal lobe surgery may induce severe memory impairment [e.g., Helmstaedter and Elger, 1996], and intracranially recorded ERPs are the most reliable predictor of memory performance after such surgical procedures [Grunwald et al., 1998b]. Thirteen out of 48 patients (7 women, mean age: 32 years, range: 19–49 years) met the described criteria of epileptic focus lateralization and availability of MRI after electrode insertion. Six of these 13 patients had well defined ITP in anterior as well as posterior IT recordings and seven patients had well defined ITP only in anterior or posterior IT recordings. On average, these patients classified 244 of 300 new words (81.3 ± 8.7%) and 129 of 150 old words (86.0 ± 8.3%) correctly.

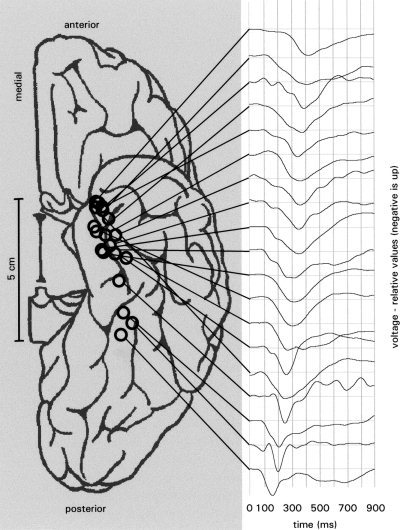

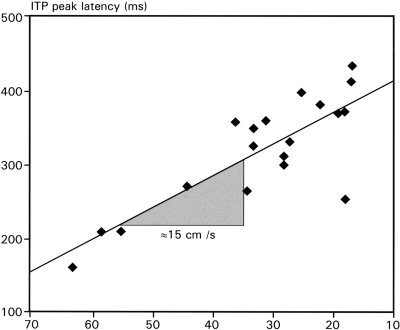

Critical electrodes covered a narrow strip, 4.6 cm in length, along both banks of the left collateral sulcus (Fig. 4). Mean ITP peak latencies, collapsed across ERPs to old and new words, linearly decreased with the distance between their recording sites and the orthogonal projection of the temporal tip onto the IT plane (Spearman correlation: r = −0.74, P < 0. 0001; Figs. 4, 5). The slope of the fitted line in the scatter plot (Fig. 5) is about 15 cm/sec, estimating the speed by which neural processing, reflected by the ITP, proceeds anteriorly through IT cortex.

Figure 4.

The inferior surface of the left hemisphere of a normalized brain (the cerebellum has been removed to reveal the IT cortex). Circles represent recording sites in individual patients with maximal ITP peak amplitudes in the across subject analysis. The ERP plots depict single subject ERPs collapsed across old and new words from these 19 recording sites in all 13 patients of this analysis. The ERPs are ordered according to their ITP peak latencies.

Figure 5.

Scatterplot of individual ITP peak latencies of the across subject analysis and the distances between their recording sites and the orthogonal projection of the temporal tip onto the temporal plane.

DISCUSSION

IT Processing Stream for Words

Our data reveals the course of a cortical processing stream for visually perceived words from posterior to anterior IT cortex by the temporal activation profile of this cortical region. When synaptic activity is sufficiently synchronous and spatially aligned, as might be expected at a certain stage of information processing [e.g., Arieli et al., 1995; Prut et al., 1998], the net extracellular current produces a field that can be recorded locally as an intracranial ERP [Halgren et al., 1994]. The maximum peak of a specific ERP component, like the ITP, is hence an averaged marker for the point in time and space when and where such a process takes place.

The relationship between ITP peak latencies and the anatomical localization of their recording sites, shown here within and across subjects, provides a reliable point of evidence for a processing stream proceeding from posterior to anterior IT regions over time. Our data are not necessarily explained by a traveling wave of synchronous activation within IT cortex. The anterior progress of synchronous neural activation, might occur in a more saltatory fashion. Such a saltatory pattern would be consistent with the modular structure of the cortex [Swindale, 1990]. Nevertheless, the uniformity of the ITP pattern may suggest the existence of a single active cortical module with an intrinsic processing stream.

The finding of proceeding IT activity is in line with unit recordings in non‐human primates during visual object perception [for review: Ungerleider and Haxby, 1994]. There, increasing neuronal response latencies and increasing complexity of response properties from striate cortex to anterior IT regions indicate that low‐level inputs are transformed into more cognitively useful representations of behaviorally relevant stimuli through successive stages of processing [e.g., Milner and Goodale, 1995]. A similar processing hierarchy from letter percept to word semantics seems to exist for word processing in humans [i.e., Allison et al., 1994; Breier et al., 1999; Cohen et al., 2000; Hagoort et al., 1999; Indefrey et al., 1997; Puce et al., 1996; Ricci et al., 1999; Tarkiainen et al., 1999; Vandenberghe et al., 1996] and it might be reflected by the ITP.

Electrodes, from which ITP recordings were obtained, covered a narrow strip on both banks of the left collateral sulcus. Most ITP recordings in our sample are therefore consistent with a rhinal, probably a perirhinal generator [Amaral and Insausti, 1990]. But posterior electrode contacts (Fig. 4), recording an ITP, seem to be located over the parahippocampal cortex [Amaral and Insausti, 1990; Burwell et al., 1996], indicating a uniformly organized IT system for word processing comprising parahippocampal and rhinal cortices of the language dominant hemisphere.

The speed of 15 cm/sec for this processing stream is just a rough estimation, because the duration of the ITP itself becomes longer with longer peak latencies (Fig. 4). Hence, the time required by the processes to reach anterior IT regions may exhibit increasing variability during the posterior‐anterior transit. As shown by the ITP onset latencies in anterior recordings (Fig. 4), some items or some item features seem to be processed in anterior IT regions as early as about 200 msec after stimulus onset, because ERPs from anterior recordings start to deflect from baseline at this point. Moreover, it is important to note that the estimation of the processing speed is based on an across subject correlation and not on actual measurements. Nevertheless, the speed of 15 cm/sec suggests that numerous synaptic transmissions take place, hence there seems to be continuous processing from posterior to anterior IT regions and not a mono‐ or oligosynaptic information transfer.

Integrated Mnemonic Function

During its IT transit, the ITP is accompanied by two distinct old/new effects, one of peak amplitudes and one of peak latencies. The old/new effect of peak amplitudes occurred regardless of the correctness of the recognition judgment for all repeated items, and the one of peak latencies occurred only for words correctly recognized as old. This dissociation may indicate a distinction between mnemonic operations subserving either implicit (e.g., repetition priming) or explicit memory (e.g., conscious recognition) [Graf and Schacter, 1985]. The relationship between repetition suppression and repetition priming is in line with numerous imaging studies in humans showing less IT activity for repeated rather than new items [Buckner and Koutstaal, 1998; but see James et al., 2000].

We can not rule out, however, that the old/new effect between new words and old words misclassified as new may represent weak explicit memory operations that are not sufficiently strong to lead to a positive recognition judgment [Rugg et al., 1998]. Such a speculation might be even supported by the overall pattern of our results: Without being reliable for each step, the mean ITP peak amplitudes and latencies decrease in a stepwise fashion (Fig. 3) from new words, through unrecognized old words to correctly recognized old words. This idea would be in line with a single trace model as assumed for explicit recognition memory based on familiarity [Mandler, 1980]. Juola et al. [1971] assumed that the familiarity measure on which subjects base their judgments of prior occurrence is a continuous scale, and that all items whose familiarity values fall above a specified high criterion are called ‘old’ and those which fall below a low criterion are called ‘new’. Thus, If this holds true, the limiting factor for recognition would be the speed of neuronal operations (peak latency) rather than the amount of IT activity (peak amplitudes), because only peak latencies and not peak amplitudes interacted significantly with the correctness of recognition judgments. Our data, however, is open to other interpretations. The amplitude modulation alone might, for instances, be related to repetition priming, and a combination of a small ITP amplitude and a short latency could be related to explicit recognition memory. Such an interpretation would also be consistent with the idea of a single trace model supporting both implicit priming and explicit recognition.

Neuropsychological studies of brain damaged patients, however, would support the notion that ITP old/new effects recorded from medial anterior IT cortex are related to explicit rather than implicit memory, because damage to this brain region leads to severe recognition memory impairments [e.g., Aggleton and Shaw, 1996; Buffalo et al., 1998; Bohbot et al., 2000], but leaves priming intact [e.g., Graf et al., 1984]. Although such a dissociation between priming and recognition memory has been frequently shown, an investigation of a large patient sample correlating the extent of medial temporal damage with performance in such tasks showed that both priming and recognition are adversely affected by damage to the medial temporal lobe including the rhinal cortex [Jernigan and Ostergaard, 1993]. Hence, implicit item‐ and explicit recognition memory may at least in part be mediated by the same processing system in a single trace model as also outlined by Mayes et al. [1997]. Our data seems to be supportive of such a missing dissociation between an implicit and an explicit memory system, but it does not clarify this issue conclusively.

The idea that human IT cortex supports recognition memory integrated with perceptual/semantic operations is in accordance with the dual process theory of recognition memory [Mandler, 1980], where the process underlying familiarity is assigned to a perceptual process. Such an integration of perceptual and mnemonic operations is as well in accordance with a model derived from data in nonhuman primates: Murray and Bussey [1999] proposed that the perirhinal cortex and its surrounding area are the final stage of the ventral visual stream representing the conjunction of perceptual features. It supports recognition memory by reacting differently to an initial as opposed to a repeated perception of a given stimulus. Thus, the perirhinal cortex of nonhuman primates represents a unitary, integrated system that supports recognition memory by differential perceptual processing of new and familiar items. Our data indicates that such an integration also exits in the medial anterior IT cortex in humans. This integrated system may perform semantic and mnemonic operations in one unitarily organized process during its anterior progress. In doing so, it may support explicit recognition memory based on stimulus familiarity.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Indira Tendolkar, Peter Klaver, and Markus Reuber for detailed comments on earlier versions of this manuscript. This work was supported by the German Research Council (DFG FE 479/4‐1) and the BONFOR, the intramural research support program of the University of Bonn.

REFERENCES

- Aggleton JP, Brown MW (1999): Episodic memory amnesia and the hippocampal‐anterior thalamic axis. Behav Brain Sci 22: 425–489. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aggleton JP, Shaw C (1996): Amnesia and recognition memory: a re‐analysis of psychometric data. Neuropsychologia 34: 51–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arieli A, Shoham D, Hildesheim R, Grinvald A (1995): Coherent spatio‐temporal patterns of ongoing activity revealed by real‐time optical imaging coupled with single‐unit recording in the cat visual cortex. J Neurophysiol 73: 2072–2093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allison T, McCarthy G, Nobre A, Puce A, Belger A (1994): Human extrastriate visual cortex and the perception of faces words numbers and colors. Cereb Cortex 4: 544–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allison T, Puce A, Spencer DD, McCarthy G (1999): Electrophysiological studies of human face perception. I. Potentials generated in the occipitotemporal cortex by face and non‐face stimuli. Cereb Cortex 9: 415–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amaral DG, Insausti R (1990): Hippocampal formation In: Paxinos G, editor. The human nervous system. San Diego: Academic Press; p 711–755. [Google Scholar]

- Bohbot VD, Allen JJ, Nadel L (2000): Memory deficits characterized by patterns of lesions to the hippocampus and parahippocampal cortex. Ann NY Acad Sci 911: 355–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breier JI, Simos PG, Zouridakis G, Papanicolaou AC (1999): Temporal course of regional brain activation associated with phonological decoding. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 21: 465–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown MW (1996): Neuronal responses and recognition memory. Semin Neurosci 8: 23–32. [Google Scholar]

- Büchel C, Price C, Friston K (1998): A multimodal language region in the ventral visual pathway. Nature 394: 274–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner RL, Koutstaal W (1998): Functional neuroimaging studies of encoding priming and explicit memory retrieval. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 891–898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buffalo EA, Reber PJ, Squire LR (1998): The human perirhinal cortex and recognition memory. Hippocampus 8: 330–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burwell RD, Suzuki WA, Insausti R, Amaral DG (1996): Some observations on the perirhinal and parahippocampal cortices in the rat monkey and human brains In: Ono T, McNaughton BL, Molotchnikoff S, Rolls ET, Nishijo H. editors. Perception memory and emotion: frontiers in neuroscience. Cambridge: Elsevier Science; p 95‐110. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen L, Dehaene S, Naccache L, Lehericy S, Dehaene‐Lambertz G, Henaff MA, Michel F (2000): The visual word form area: spatial and temporal characterization of an initial stage of reading in normal subjects and posterior split‐brain patients. Brain 123: 291–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desimone R (1996): Neural mechanisms for visual memory and their role in attention. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93: 13494–13499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elger CE, Grunwald T, Lehnertz K, Kutas M, Helmstaedter C, Brockhaus A, Van Roost D, Heinze HJ (1997): Human temporal lobe potentials in verbal learning and memory processes. Neuropsychologia 35: 657–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández G, Effern A, Grunwald T, Pezer N, Lehnertz K, Dümpelmann M, Van Roost D, Elger CE (1999): Real‐time tracking of memory formation in the human rhinal cortex and hippocampus. Science 285: 1582–1585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graf P, Schacter DL (1985): Implicit and explicit memory for new associations in normal and amnesic subjects. J Exp Psychol Learn Mem Cogn 11: 501–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graf P, Squire LR, Mandler G (1984): The information that amnesic patients do not forget. J Exp Psychol Learn Mem Cogn 10: 164–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunwald T, Elger CE, Lehnertz K, Van Roost D, Heinze HJ (1995): Alterations of intrahippocampal cognitive potentials in temporal lobe epilepsy. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 95: 53–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunwald T, Lehnertz K, Heinze HJ, Helmstaedter C, Elger CE (1998a): Verbal novelty detection within the human hippocampus proper. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 3193–3197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunwald T, Lehnertz K, Helmstaedter C, Kutas M, Pezer N, Kurthen M, Van Roost D, Elger CE (1998b): Limbic ERPs predict verbal memory after left‐sided hippocampectomy. Neuroreport 9: 3375–3378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunwald T, Lehnertz K, Pezer N, Kurthen M, Van Roost D, Schramm J, Elger CE (1999a): Prediction of postoperative seizure control by hippocampal event‐related potentials. Epilepsia 40: 303–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunwald T, Beck H, Lehnertz K, Blümcke I, Pezer N, Kutas M, Kurthen M, Karakas HM, Van Roost D, Wiestler OD, Elger CE (1999b): Limbic P300s in temporal lobe epilepsy with and without Ammon horn sclerosis. Eur J Neurosci 11: 1899–1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillem F, N'Kaoua B, Rougier A, Claverie B (1995): Effects of temporal vs. temporal plus extra‐temporal lobe epilepsies on hippocampal ERPs: physiopathological implications for recognition memory studies in human. Cogn Brain Res 2: 147–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillem F, Rougier A, Claverie B (1999): Short‐ and long‐delay intracranial ERP repetition effects dissociate memory systems in the human brain. J Cogn Neurosci 11: 437–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagoort P, Indefrey P, Brown C, Herzog H, Steinmetz H, Seitz RJ (1999): The neural circuitry involved in the reading of German words and pseudowords: a PET study. J Cogn Neurosci 11: 383–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halgren E, Baudena P, Heit G, Clarke M, Marinkovic K (1994): Spatio‐temporal stages in face and word processing. I. Depth recorded potentials in the human occipital and parietal lobes. J Physiol (Paris) 88: 1–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haxby JV, Grady CL, Horwitz B, Ungerleider LG, Mishkin M, Carson RE, Herscoviych P, Shapiro MB, Rapoport SI (1991): Dissociation of object and spatial visual processing pathways in human extrastriate cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 88: 1621–1625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heit G, Smith ME, Halgren E (1988): Neural encoding of individual words and faces by the human hippocampus and amygdala. Nature 333: 773–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heit G, Smith ME, Halgren E (1990): Neuronal activity in the human medial temporal lobe during recognition memory. Brain 113: 1093–1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmstaedter C, Elger CE (1996): Cognitive consequences of two‐thirds anterior temporal lobectomy on verbal memory in 144 patients: a 3‐month follow‐up study. Epilepsia 37: 171–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Indefrey P, Kleinschmidt A, Merboldt KD, Kruger G, Brown C, Hagoort P, Frahm J (1997): Equivalent responses to lexical and nonlexical visual stimuli in occipital cortex: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Neuroimage 5: 78–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James TW, Humphrey GK, Gati JS, Menon RS, Goodale MA (2000): The effects of visual object priming on brain activation before and after recognition. Curr Biol 10: 1017–1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jernigan TL, Ostergaard AL (1993): Word priming and recognition memory are both affected by mesial temporal lobe damage. Neuropsychology 7: 14–26. [Google Scholar]

- Juola JF, Fischler I, Wood CT, Atkinson RC (1971): Recognition time for information stored in long‐term memory. Precept Psychophys 10: 8–14. [Google Scholar]

- Lerner Y, Hendler T, Ben‐Bashat D, Harel M, Malach R (2001): A hierarchical axis of object processing stages in the human visual cortex. Cereb Cortex 11: 287–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Miller EK, Desimone R (1993): The representation of stimulus familiarity in anterior inferior temporal cortex. J Neurophysiol 69: 1918–1929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandler D (1980): Recognizing: the judgment of previous occurrence. Psychol Rev 87: 252–271. [Google Scholar]

- Mayes AR, Gooding PA, van Eijk R (1997): A new theoretical framework for explicit and implicit memory. Psyche 3 http://psyche.cs.monash.edu.au. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy G, Nobre AC, Bentin S, Spencer DD (1995): Language‐related field potentials in the anterior‐medial temporal lobe: I. intracranial distribution and neural generators. J Neurosci 15: 1080–1089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller EK, Li L, Desimone R (1991): A neural mechanism for working and recognition memory in inferior temporal cortex. Science 254: 1377–1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milner AD, Goodale MA (1995): The visual brain in action. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Murray EA, Bussey TJ (1999): Perceptual‐mnemonic functions of the perirhinal cortex. Trends Cogn Sci 3: 142–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nobre AC, McCarthy G (1995): Language‐related field potentials in the anterior‐medial temporal lobe. II. Effects of word type and semantic priming. J Neurosci 15: 1090–1098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nobre AC, Allison T, McCarthy G (1994): Word recognition in the human inferior temporal lobe. Nature 372: 260–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nobre AC, Allison T, McCarthy G (1998): Modulation of human extrastriate visual processing by selective attention to colors and words. Brain 121: 1357–1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prut Y, Vaadia E, Bergman H, Haalman I, Slovin H, Abeles M (1998): Spatio‐temporal structure of cortical activity: properties and behavioral relevance. J Neurophysiol 79: 2857–2874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puce A, Kalnins RM, Berkovic SF, Donnan GA, Bladin PF (1989): Limbic P3 potentials seizure localization and surgical pathology in temporal lobe epilepsy. Ann Neurol 26: 377–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puce A, Andrewes DG, Berkovic SF, Bladin PF (1991): Visual recognition memory. Neurophysiological evidence for the role of temporal white matter in man. Brain 114: 1647–1666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puce A, Allison T, Asgari M, Gore JC, McCarthy G (1996): Differential sensitivity of human visual cortex to faces letter strings and textures: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study. J Neurosci 16: 5205–5215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricci PT, Zelkowicz BJ, Nebes RD, Meltzer CC, Mintun MA, Becker JT (1999): Functional neuroanatomy of semantic memory: Recognition of semantic associations. Neuroimage 9: 88–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rugg MD, Nagy ME (1989): Event‐related potentials and recognition memory for words. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 72: 395–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rugg MD, Mark RE, Walla P, Schloerscheidt AM, Birch CS, Allan K (1998): Dissociation of the neural correlates of implicit and explicit memory. Nature 392: 595–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith ME, Stapleton JM, Halgren E (1986): Human medial temporal lobe potentials evoked in memory and language tasks. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 63: 145–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swindale NV (1990): Is the cerebral cortex modular? Trends Neurosci 13: 487–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarkiainen A, Helenius P, Hansen PC, Cornelissen PL, Salmelin R (1999): Dynamics of letter string perception in the human occipitotemporal cortex. Brain 122: 2119–2132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ungerleider LG, Mishkin M (1982): Two cortical visual systems In: Ingle DJ, Goodale MA, Mansfield RJW, editors. Analysis of visual behavior. Cambridge: MIT Press; p 549–586. [Google Scholar]

- Ungerleider LG, Haxby JV (1994): 'What' and 'where' in the human brain. Curr Opin Neurobiol 4: 157–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandenberghe R, Price C, Wise R, Josephs O, Frackowiak RSJ (1996): Functional anatomy of a common semantic system for words and pictures. Nature 383: 254–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]