Abstract

Background

Behçet's disease is a chronic inflammatory vasculitis that can affect multiple systems. Mucocutaneous involvement is common, as is the involvement of many other systems such as the central nervous system and skin. Behç̧et's disease can cause significant morbidity, such as loss of sight, and can be life threatening. The frequency of oral ulceration in Behçet's disease is thought to be 97% to 100%. The presence of mouth ulcers can cause difficulties in eating, drinking, and speaking leading to a reduction in quality of life. There is no cure for Behçet's disease and therefore treatment of the oral ulcers that are associated with Behçet's disease is palliative.

Objectives

To determine the clinical effectiveness and safety of interventions on the pain, episode duration, and episode frequency of oral ulcers and on quality of life for patients with recurrent aphthous stomatitis (RAS)‐type ulceration associated with Behçet's disease.

Search methods

We undertook electronic searches of the Cochrane Oral Health Group Trials Register (to 4 October 2013); the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library 2013, Issue 9); MEDLINE via Ovid (1946 to 4 October 2013); EMBASE via Ovid (1980 to 4 October 2013); CINAHL via EBSCO (1980 to 4 October 2013); and AMED via Ovid (1985 to 4 October 2013). We searched the US National Institutes of Health trials register (http://clinicaltrials.gov) and the World Health Organization (WHO) Clinical Trials Registry Platform for ongoing trials. There were no restrictions on language or date of publication in the searches of the electronic databases. We contacted authors when necessary to obtain additional information.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that looked at pre‐specified oral outcome measures to assess the efficacy of interventions for mouth ulcers in Behçet's disease. The oral outcome measures included pain, episode duration, episode frequency, safety, and quality of life. Trials were not restricted by outcomes alone.

Data collection and analysis

All studies meeting the inclusion criteria underwent data extraction and an assessment of risk of bias, independently by two review authors and using a pre‐standardised data extraction form. We used standard methodological procedures expected by Cochrane.

Main results

A total of 15 trials (n = 888 randomised participants) were included, 13 were placebo controlled and three were head to head (two trials had more than two treatment arms). Eleven of the trials were conducted in Turkey, two in Japan, one in Iran and one in the UK. Most trials used the International Study Group criteria for Behçet's disease. Eleven different interventions were assessed. The interventions were grouped into two categories, topical and systemic. Only one study was assessed as being at low risk of bias. It was not possible to carry out a meta‐analysis. The quality of the evidence ranged from moderate to very low and there was insufficient evidence to support or refute the use of any included intervention with regard to pain, episode duration, or episode frequency associated with oral ulcers, or safety of the interventions.

Authors' conclusions

Due to the heterogeneity of trials including trial design, choice of intervention, choice and timing of outcome measures, it was not possible to carry out a meta‐analysis. Several interventions show promise and future trials should be planned and reported according to the CONSORT guidelines. Whilst the primary aim of many trials for Behç̧et's disease is not necessarily reduction of oral ulceration, reporting of oral ulcers in these studies should be standardised and pre‐specified in the methodology. The use of a core outcome set for oral ulcer trials would be beneficial.

Plain language summary

Interventions for managing oral ulcers in Behçet's disease

Review question

This review has been conducted to assess the effects of different interventions, administered systemically or topically, for the prevention or treatment of oral ulcers in people with Behçet's disease. The interventions could be compared with an alternative intervention, no intervention or the administration of a placebo.

Background

Behçet's disease is a chronic disease characterised by a multitude of signs and symptoms including oral and genital ulcerations, skin lesions and inflammatory vascular involvement of the central nervous system and gastrointestinal tract. Although the underlying cause of Behçet’s disease is unknown it is thought to involve a genetic predisposition combined with environmental factors.

Behçet's disease most commonly presents in the third decade. The disease is rare in individuals older than age 50 years and during childhood. Although both sexes are equally affected, it is thought that the disease has a more severe course amongst men.

The oral ulceration that occurs in Behçet's disease can be painful and slow to heal. At its worst, this can cause significant difficulties in eating and drinking.

Study characteristics

Authors from Cochrane Oral Health carried out this review of existing studies and the evidence is current up to 4 October 2013. The review includes 15 studies published from 1980 to 2012 in which 888 participants were randomised. Eleven of the trials were conducted in Turkey, two in Japan, one in Iran, and one in the UK. Thirteen different interventions were assessed, administered either topically or systemically.

Topical interventions: sucralfate, interferon–alpha (different doses), cyclosporin A, triamcinolone acetonide ointment, phenytoin syrup mouthwash.

Systemic interventions: aciclovir, thalidomide (different doses), corticosteroids, rebamipide, etanercept, colchicine, interferon–alpha, cyclosporin.

Key results

There was insufficient evidence to support or refute the use of any included intervention with regard to pain, episode duration or episode frequency associated with oral ulcers, or the safety of the interventions.

Quality of the evidence

The quality of the evidence ranged from moderate to very low.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

Behçet's disease is a chronic, relapsing, multisystem inflammatory vasculitis (Chams‐Davatchi 2010). It affects both the large and small blood vessels (including veins and arteries) (Mat 2013). It is characterised by a multitude of systemic signs and symptoms. Oral and genital ulcerations, skin lesions, uveitis, and inflammatory vascular involvement of the central nervous system and gastrointestinal tract are common (Dalvi 2012). Although the aetiology of Behçet’s disease is unknown it is thought to involve a genetic predisposition combined with environmental factors (Yazici 2012).

The genetic risk factor most strongly associated with Behçet's disease is the human leukocyte antigen (HLA)‐B51 allele. HLA‐B51 occurs in around 60% of Behçet's disease patients (Gul 2007; Kose 2012; Yazici 1980).

Behçet's disease is more frequent in the countries along the 'Silk Road', an ancient trading route, where the prevalence of HLA‐B51 is relatively high compared with the other parts of the globe (Yurdakul 2010).

Behçet's disease most commonly presents in the third decade. The disease is rare in individuals older than age 50 years and during childhood. Although both sexes are equally affected, it is thought that the disease has a more severe course amongst men (Yazici 1984).

Diagnosis

Previously, the International Study Group (ISG) Guidelines for the Classification of Behçet's disease were generally accepted as a diagnostic tool (ISG 1990).

The criteria included recurrent oral 'aphthae' (at least three episodes within 12 consecutive months) plus two of the following: recurrent genital ulcers; uveitis or retinal vasculitis; skin lesions that are classified as erythema nodosum (EN)‐like lesions, acneiform lesions, pustulosis, or pseudofolliculitis; and a positive pathergy test.

More recently a large group involving people from 32 countries attempted to establish new international guidelines (Davatchi 2012). Following a prospective, international, multicentre, diagnostic accuracy study, data from over 2556 Behçet's patients from 27 different countries were reviewed. A new diagnostic scoring system was developed. As with the previous diagnostic criteria, oral lesions scored highly along with ocular and genital lesions. In fact 98% of Behçet's patients had oral aphthous ulceration as a feature (Davatchi 2004).

Oral ulceration in Behçet's disease

The oral ulceration that occurs in Behçet's disease resembles recurrent aphthous stomatitis (RAS). In the oral medicine and dental literature RAS is now commonly used as a term to indicate a primary condition where ulceration is not in association with a systemic disease such as Behçet's. Where a relevant systemic disease is present, various terms including RAS‐type ulceration would be used instead. In the general medical literature however, this division of nomenclature is not widely used and the oral ulceration in Behçet's is indistinguishable in appearance and natural history from RAS. It remains unclear whether the ulceration in RAS and RAS‐type ulceration shares a common pathogenesis. The term for oral ulceration in association with Behcet's disease in the international guidelines criteria includes oral aphthosis (ISG 1990) and oral aphthous lesions (Davatchi 2012). For the purposes of this review we have reviewed studies where aphthous ulceration is clearly the type of mouth ulceration being investigated, regardless of which precise terminology is used.

RAS is the most common form of oral ulceration with prevalence in the different populations ranging between 5% and 60% (Jurge 2006).

RAS‐type ulceration in association with a systemic disease is common. Systemic diseases featuring RAS‐type ulceration can include, but are not limited to, coeliac disease, Crohn's disease, vitamin B12 deficiency, iron deficiency anaemia, human immunodeficiency virus infection/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS), cyclic neutropenia, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), and Behçet's disease (Baccaglini 2011).

The frequency of RAS‐type ulceration in Behçet's disease is 97% to 100% (Yurdakul 2008). There are a variety of Beḩcet's diagnostic criteria used over many years. Since 1990, the ISG have been most commonly but not exclusively used. Whichever criteria are used, RAS‐type ulceration is a major feature with high prevalence.

According to Bagan 1991, there are three recognised forms of RAS (and hence also RAS‐type ulceration).

Minor aphthae, typically round and less than 10 mm in diameter. These are generally pale in colour with an erythematous border and commonly affect non‐keratinised mucosa including the labial and buccal mucosa, the borders of the tongue, and the floor of the mouth. Minor aphthae can occur in isolation but multiple presentations are also common. Healing is spontaneous and usually takes 7 to 10 days. Episodes of ulceration are usually followed by an ulcer‐free period lasting a few days to several weeks before the next episode occurs (Thornhill 2007).

Major aphthae are similar to minor aphthae but are larger, usually exceeding 10 mm in diameter, and deeper. Consequently healing can take longer (20 to 30 days) and may result in scarring (Bagan 1991).

Herpetiform ulcers are less than 1 mm in diameter and often occur in multiples, from 1 to 100. There is a tendency for adjacent ulcers to merge.

In Behçet's disease, minor aphthae‐type lesions are the most commonly seen type, whereas major and herpetiform types are rare (Hamuryudan 1998; Melikoglu 2005; Yurdakul 2001). This mirrors the frequency of the different forms of aphthae in RAS patients.

Description of the intervention

The cause of RAS is not known; therefore the aims of treatment are primarily pain relief and the reduction of inflammation (Scully 2006). The cause of RAS‐type oral ulceration in Behçet's disease is also poorly understood and, therefore, treatment aimed primarily at the oral ulceration in Behç̧et's disease is also targeted at pain relief and the promotion of healing to reduce the duration of the disease or reduce the rate of recurrence. A variety of topical and systemic therapies have been utilised (Porter 1998) but few studies have demonstrated efficacy. Empirically, effective treatments include the use of corticosteroids, immunosuppressants, and topical barriers (Eisen 2001). Topical interventions can include mouthrinses, pastes, gels, sprays, injections, laser, and locally dissolving tablets. Many of the topical treatments are available without prescription. Systemic immunomodulators such as mycophenolate mofetil, pentoxyphylline, colchicine, dapsone, and thalidomide have also been used but with some caution due to their potential for adverse effects.

How the intervention might work

As the aetiopathogenesis of RAS‐type ulceration in Behçet's disease is not fully understood, the precise mechanisms of how the various topical and systemic interventions influence the disease process are unclear.

Topical interventions for oral ulceration range from inert barriers to active treatments. Providing a barrier for the ulcer (for example with a mucoadhesive paste) should allow the breach in the mucosa to temporarily be protected and therefore noxious stimulants are less likely to sensitise nerve endings. This in theory should provide pain relief. The addition of active compounds to the barrier can potentially give an immunomodulatory effect. Due to the nature of the mucosal layer, there is great variability in the penetration of active compounds through the mucosal barrier, and as such there is great variability in the efficacy of the topical treatments.

Systemic interventions include immunomodulators (colchicine, azathioprine, cyclosporin, thalidomide), corticosteroids, biological agents (interferon; anti‐TNF agents such as infliximab, etanercept, adalimumab), and other drugs such as dapsone and daclizumab. As previously stated, the precise mode of action of these interventions is often unclear.

Many of the systemic treatments used in Behçet's disease are given to control the underlying disease process and not primarily for the oral ulceration. Nevertheless, these systemic treatments may also improve the severity and frequency of episodes of RAS‐type ulceration in these patients. Where systemic treatments are being used primarily for control of RAS‐type ulceration, the risk‐benefit ratios are important and may be different to those when trying to control widespread or critical disease. In practice, a combination of systemic therapy for the underlying disease and topical therapy for symptomatic treatment of acute attacks of oral ulceration are frequently used.

Why it is important to do this review

All three clinical types of RAS and RAS‐type ulceration are associated with varying degrees of morbidity, including pain and difficulties in function. RAS (and RAS‐type) ulceration is a chronic episodic oral mucosal condition which can impact upon the experiences of daily life, such as physical health and functioning (Riordain 2011).

A recent Cochrane review (Brocklehurst 2012) evaluated the evidence for systemic interventions for RAS and an ongoing review by the same author group is evaluating topical interventions for RAS (Taylor 2013). Both of these reviews have specifically excluded trials of interventions for oral ulcers in patients with systemic disease. This therefore excludes trials involving Behçet's patients.

There is, therefore, a population of patients in whom oral ulcers are the most common presenting feature and for whom we have no formal evaluation of the evidence base on which to guide our clinical treatments for them. An evaluation of the evidence for interventions for oral ulcers in this group of patients is therefore essential.

Objectives

The objectives of this review are to determine the clinical effectiveness and safety of interventions on the pain, episode duration, and episode frequency of oral ulcers and on quality of life for patients with recurrent aphthous stomatitis (RAS)‐type ulceration associated with Behçet's disease.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) investigating the effects of interventions for the management of recurrent aphthous stomatitis (RAS)‐type ulceration in Behçet's disease were included. We also included RCTs of a cross‐over design provided that the trial included a suitable washout period and no carry‐over effects were evident. Split‐mouth studies were also to be included if it was apparent that there was no risk of contamination of the intervention from one part of the mouth to another (this would be more likely for any topical interventions that was physically applied and retained in one part of the mouth rather than a mouthwash for example).

Studies looking at interventions for the management of any systemic manifestations of Behçet's disease and which also reported on oral ulcers as an outcome measure were included. The oral outcome measures should have been pre‐specified in the methodology.

Types of participants

Participants with Behçet's disease with a history of recurrent oral aphthous‐type ulcers that were diagnosed clinically were included. Where additional systemic diseases were reported in studies, these were noted.

Types of interventions

Active treatment included any preventive, palliative, or curative interventions administered systemically or topically. Comparators were either standard care, no active treatment, or the administration of a placebo; head to head trials of different interventions were also included.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Pain associated with oral ulcers.

Episode duration associated with oral ulcers.

Episode frequency associated with oral ulcers.

Safety of the intervention including adverse effects.

Secondary outcomes

Any patient‐reported outcomes that measured a change in the patients' quality of life or in morbidity (e.g. function), or both.

Search methods for identification of studies

For the identification of studies included or considered for this review, we developed detailed search strategies for each database searched. These were based on the search strategy developed for MEDLINE (Ovid) but revised appropriately for each database (Appendix 1). We combined this search strategy with the Cochrane highly sensitive search strategy (CHSSS) for identifying RCTs in MEDLINE: sensitivity maximising version, as referenced in Chapter 6.4.11.1 and detailed in box 6.4.c of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We linked the searches of EMBASE and CINAHL to the Cochrane Oral Health Group filters for identifying RCTs.

Electronic searches

The following electronic databases were searched:

Cochrane Oral Health Group Trials Register (to 4 October 2013) (see Appendix 2);

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library 2013, Issue 9) (see Appendix 3);

MEDLINE via Ovid (1946 to 4 October 2013) (see Appendix 1);

EMBASE via Ovid (1980 to 4 October 2013) (see Appendix 4);

CINAHL via EBSCO (1980 to 4 October 2013) (see Appendix 5);

AMED via Ovid (1985 to 4 October 2013) (see Appendix 6).

There were no restrictions on language or date of publication in the searches of the electronic databases.

Searching other resources

Unpublished trials

We screened the bibliographies of included papers and relevant review articles were checked for studies not identified by the search strategies above.

We searched the following databases for ongoing trials (see Appendix 7):

US National Institutes of Health trials register (clinicaltrials.gov);

World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (apps.who.int/trialsearch/).

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (Jennifer Taylor (JT) and Anne‐Marie Glenny (AMG)) independently screened the titles and abstracts obtained from the initial electronic searches. Reports from the studies that fulfilled the inclusion criteria were obtained. When there were insufficient data in the study title to determine whether a study fulfilled the inclusion criteria, the full report was obtained and assessed independently by the same review authors. Disagreements were resolved by discussion.

Data extraction and management

At least two review authors (JT, AMG, Tanya Walsh (TW), Paul Brocklehurst (PB), and Philip Riley (PR)) independently extracted data from each included study using a tool developed for the review. All studies meeting the inclusion criteria underwent data extraction and an assessment of risk of bias using a pre‐standardised data extraction form. Studies rejected at this and subsequent stages were recorded in the table 'Characteristics of excluded studies'. Differences were resolved by discussion. If a single publication reported two or more separate studies, then the data from each study were extracted separately. If the findings of a single study were spread across two or more publications, then the publications were extracted as one. For each study with more than one control or comparison group for the intervention, the results were extracted for each intervention arm.

For each trial the following data were recorded.

Year of publication, country of origin, and source of study funding.

Details of the participants including demographic characteristics and criteria for inclusion.

Details on the type of intervention and comparisons.

Details on the study design.

Details on the outcomes reported, including methods and timings of assessments, and adverse outcomes.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

All review authors assessed the risk of bias in the included studies using the Cochrane's tool for assessing risk of bias. The domains that were assessed for each included study were:

sequence generation (selection bias);

allocation concealment (selection bias);

blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias);

blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias);

completeness of outcome data (attrition bias);

selective outcome reporting (reporting bias);

risk of other potential sources of bias (other bias).

We tabulated a description of the above domains for each included trial, along with a judgement of the risk of bias (low, high, or unclear), based on the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011).

An example of a risk of bias judgement, based on allocation concealment only, is shown below:

low risk of bias (adequate concealment of the allocation (e.g. sequentially numbered, sealed, opaque envelopes or centralised or pharmacy‐controlled randomisation));

unclear risk of bias (unclear about whether the allocation was adequately concealed (e.g. where the method of concealment was not described or not described in sufficient detail to allow a definite judgement));

high risk of bias (inadequate allocation concealment (e.g. open random number lists or quasi‐randomisation such as alternate days, date of birth, or case record number)).

We provided a summary assessment of the risk of bias for the primary outcomes across the studies (Higgins 2011). For each study, we assessed the overall risk of bias according to the following rationales:

low risk, when there is a low risk of bias across all seven key domains;

unclear risk of bias, when there is an unclear risk of bias in one or more of the seven key domains;

high risk of bias, when there is a high risk of bias in one or more of the seven key domains.

If high risk of bias is present in one of the seven domains then it took precedence.

Measures of treatment effect

For dichotomous outcomes (for example presence or absence of pain), we expressed the estimate of effect of an intervention as risk ratio (RR) together with 95% confidence interval (CI). For continuous outcomes (for example pain on a visual analogue scale), we used mean differences (MDs) and 95% CIs to summarise the data; in the event that different studies measured outcomes using different scales, we would have expressed the estimate of effect of an intervention as standardised mean difference (SMD) and 95% CI.

Unit of analysis issues

If cluster randomised trials had been included, we would have undertaken data analysis, whenever feasible, at the same level as the randomisation, or at the individual level accounting for the clustering.

Analysis of cross‐over studies should take into account the two‐period nature of the data using, for example, a paired t‐test (Elbourne 2002). We would have entered log RRs or MDs (or SMDs) and standard errors into Review Manager (RevMan) software (Review Manager 2012) using the generic inverse variance method (Higgins 2011).

Dealing with missing data

We contacted trial authors for missing data if the report was published from the year 2000 or onwards. We considered it unfeasible to obtain data for trials published prior to this cut‐off date. We used methods as outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions to estimate missing standard deviations (Higgins 2011).

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed clinical and methodological heterogeneity. We further assessed the significance of any discrepancies in the estimates of the treatment effects from the different trials by means of Cochran's Chi2 test for heterogeneity; heterogeneity would have been considered significant if P < 0.1 (Higgins 2011). We also used the I2 statistic, which describes the percentage total variation across studies that is due to heterogeneity rather than chance, to quantify heterogeneity; with I2 over 50% being considered substantial heterogeneity (Higgins 2011).

Assessment of reporting biases

If there had been a sufficient number of trials (more than 10) included in any meta‐analysis, we would have assessed publication bias according to the recommendations on testing for funnel plot asymmetry as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011).

Data synthesis

If data had allowed, we would have performed meta‐analysis of studies assessing the same comparisons and outcomes. We would combine RRs for dichotomous outcomes, and MDs (or SMDs if different scales were used) for continuous outcomes, using a random‐effects model where there were four or more studies, or a fixed‐effect model if there were less than four studies. We would have included data from split‐mouth or cross‐over studies in any meta‐analysis using the generic inverse variance method described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011), combining them with parallel studies using the methods described in Elbourne 2002. As meta‐analysis was not possible, we presented data in an additional table.

Sensitivity analysis

If the number of studies had allowed, we would have undertaken a sensitivity analysis for each intervention and outcome by limiting the analysis to studies at overall low risk of bias.

Presentation of main results

We developed a 'Summary of findings' table for the main outcomes. We assessed the quality of the body of evidence with reference to the overall risk of bias of the included studies, the directness of the evidence, the inconsistency of the results, the precision of the estimates, the risk of publication bias, and the magnitude of the effect. We categorised the quality of the body of evidence of each of the main outcomes as high, moderate, low, or very low.

Results

Description of studies

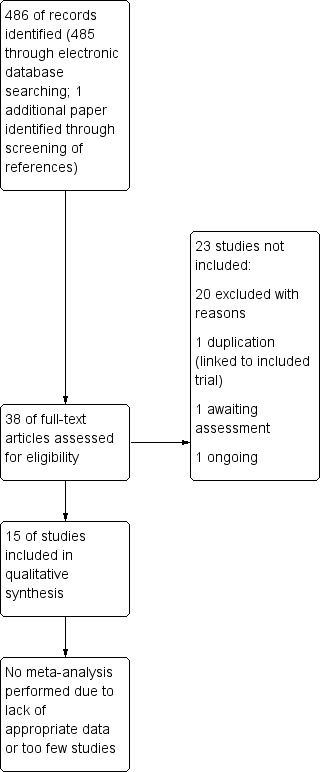

A total of 486 articles were identified through our search strategy. Of these, 38 articles appeared to be potentially relevant and full copies were obtained. Following screening of full papers, 15 studies were identified for inclusion (Figure 1). One trial had been completed but had not been fully published as yet (NCT00866359), one trial is ongoing (NCT01441076), and one trial was duplicated and linked to a subsequent included study (Masuda 1989). Twenty studies were excluded (Characteristics of excluded studies).

1.

Study flow diagram.

Results of the search

A total of 15 trials were included in the review (n = 888 randomised participants; 780 evaluated) (Characteristics of included studies).

Included studies

The studies varied in sample size, ranging from 24 to 116. Eleven of the trials were conducted in Turkey, two in Japan, one in Iran, and one in the UK.

One trial was a cross‐over design with a washout period (Davies 1988) and the remaining 14 were designed as parallel studies.

The funding source was not stated in six of the trials. Six trials received pharmaceutical company funding and three further trials received funding from research facilities.

The diagnosis of Behçet's disease was not described clearly in all of the studies. Most trials used the International Study Group criteria for Behç̧et's disease (ISG 1990). The two studies from Japan used the Japanese diagnostic criteria, which were only described in detail in one of the trials, and one trial used the O'Duffy criteria (Aktulga 1980).

Six of the trials evaluated topical interventions applied directly to the ulcers and nine evaluated systemic interventions. The interventions used within the trials were diverse, and the mode of action with regard to the management of oral ulcers was often unclear.

Topical interventions

The six trials evaluating topical interventions assessed five main comparisons (five placebo controlled; two head to head).

Sucralfate versus placebo (Alpsoy 1999; Koc 1992).

Interferon–alpha (different doses) versus placebo (Hamuryudan 1991; Kilic 2009).

Cyclosporin A versus placebo (Ergun 1997).

Triamcinolone acetonide ointment versus phenytoin syrup mouthwash (Fani 2012).

Interferon–alpha 1000 IU versus interferon–alpha 2000 IU (Kilic 2009).

Systemic interventions

The nine trials evaluating systemic interventions assessed nine main comparisons (eight placebo controlled; one head to head).

Aciclovir versus placebo (Davies 1988).

Thalidomide (different doses) versus placebo (Hamuryudan 1998).

Corticosteroids versus placebo (Mat 2006).

Rebamipide versus placebo (Matsuda 2003).

Etanercept versus placebo (Melikoglu 2005).

Colchicine versus placebo (Aktulga 1980; Yurdakul 2001).

Interferon–alpha versus placebo (Alpsoy 2002).

Thalidomide 300 mg versus 100 mg versus placebo (Hamuryudan 1998).

Cyclosporin versus colchicine (Masuda 1989).

Six of the 15 studies were primarily looking at interventions for oral ulceration (Ergun 1997; Fani 2012; Hamuryudan 1991; Kilic 2009; Koc 1992; Matsuda 2003). Five studies had the management of Behç̧et's disease as the main aim (Aktulga 1980; Alpsoy 2002; Masuda 1989; Melikoglu 2005; Yurdakul 2001). The remaining studies looked at orogenital ulceration or genital ulceration (Alpsoy 1999; Davies 1988; Hamuryudan 1998; Mat 2006).

A wide range of outcomes were assessed, making comparison across trials difficult. For example, oral ulcers were measured using the following:

number of oral ulcers;

mean frequency of ulcers or number of episodes;

mean duration of ulcers;

ulcer healing time;

severity of ulcers;

size of ulcers;

time to initial response;

recurrence of ulcers;

time to recurrence of ulcers;

complete response, defined as absence of any oral ulcer of any size during treatment period;

percentage change in a patient's total ulcer burden;

monthly aphthae count.

Pain measurements included:

pain (e.g. scale of 0 to 3 (0: absent; 1: mild; 2: moderate; and 3: severe));

number of painful days;

ratio of painful days to days with ulcers;

total monthly pain scores.

Nine of the 15 studies did not report on pain as an outcome measure (Aktulga 1980; Ergun 1997; Fani 2012; Hamuryudan 1991; Masuda 1989; Mat 2006; Melikoglu 2005; Yurdakul 2001; Hamuryudan 1998).

The study by Kilic 2009 stated that pain was an outcome but did not describe how it would be measured and did not report any pain data in the results (Kilic 2009).

Other reported outcomes included measures of 'overall response' or 'positive response' (not specified), 'other disease features', laboratory abnormalities, number and severity of genital ulcers, response of eye disease to treatment, ocular complications, patient‐reported general well‐being, global disease severity, amount of suppression of pathergy and midstream specimen of urine (MSU) tests, and attacks of arthritis.

Three out of 15 trials failed to report adverse events (Fani 2012; Hamuryudan 1991; Koc 1992). None of the studies reported on issues of cost or reduction of morbidity. One trial described the use of a quality of life assessment tool but did not report any data on quality of life (Kilic 2009).

Excluded studies

Twenty trials were excluded (Characteristics of excluded studies). The main reason for exclusion was that following access to the full paper the study did not actually fulfil the criteria for being a RCT (eight studies) (lack of randomisation, no control group). Three cross‐over studies were excluded because of: lack of a washout period, one presented on topical only treatments for genital ulcers, and one reported oral ulcer outcomes but this was ad hoc reporting and not pre‐specified. Two papers was rejected as they were letters with insufficient information reported. Both letters were published longer than 10 years ago and we therefore did not obtain any further information from the authors (Convit 1984; Scheinberg 2002).

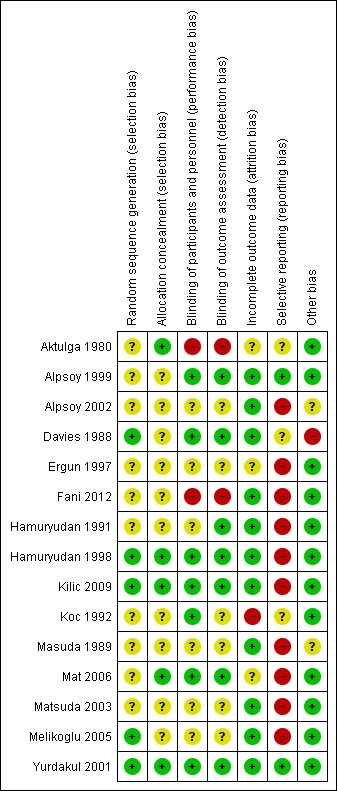

Risk of bias in included studies

A summary of the risk of bias for each study is presented in Figure 2 and the ‘Characteristics of included studies’ table.

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Only one trial was assessed as being at low risk of bias (Yurdakul 2001). One of the trials was assessed as having overall unclear risk of bias (Alpsoy 1999). The remaining 13 trials were assessed as at overall high risk of bias.

Allocation

Three of the 15 trials were given an overall low risk of bias for selection bias (both for sequence generation and allocation concealment) (Hamuryudan 1998; Kilic 2009; Yurdakul 2001). Twelve of the 15 were assessed as at overall unclear risk of bias for allocation. Of these 12, the random sequence generation was at low risk of bias for two trials (Davies 1988; Melikoglu 2005) and allocation concealment was at low risk of bias for two (Aktulga 1980; Mat 2006).

Blinding

Six trials were shown to be at low risk of bias for blinding (Alpsoy 1999; Davies 1988; Hamuryudan 1998; Kilic 2009; Mat 2006; Yurdakul 2001). Seven trials had an overall unclear risk of bias, of which one had a low risk for detection bias (Hamuryudan 1991) and one had a low risk for performance bias (Koc 1992). Two trials had a high risk of bias for blinding as the interventions used were different in appearance and delivery method (Aktulga 1980; Fani 2012).

Incomplete outcome data

One trial was assessed as at high risk of bias due to incomplete data (Koc 1992) as all six dropouts were from the intervention arm and insufficient reasons were presented. Three trials were assessed as at unclear risk of bias (Aktulga 1980; Ergun 1997; Mat 2006). The remaining 11 trials were deemed low risk of bias.

Selective reporting

Only two of the 15 trials were given low risk of bias for selective reporting (Alpsoy 1999; Yurdakul 2001). Three trials (Aktulga 1980; Davies 1988; Koc 1992) were judged to be at unclear risk of bias and the remaining 10 trials were at high risk of bias. The most frequent reason for allocation of a high risk of bias was failure to report outcome data fully (Alpsoy 2002; Ergun 1997; Hamuryudan 1998; Masuda 1989; Matsuda 2003). Some trials presented only a selection of the pre‐specified outcome measures (Kilic 2009) or presented outcomes that were not pre‐specified (Mat 2006). One trial did not present the results for the outcomes pre‐specified in the trial protocol (Fani 2012). Some trials presented means with no standard deviations (Davies 1988; Kilic 2009) or only a P value (Davies 1988). Some trials carried out further analyses to support the findings, however the analyses were not presented (Hamuryudan 1991; Melikoglu 2005).

Other potential sources of bias

Twelve out of 15 trials were thought to have low risk for other potential sources of bias. Two trials were at unclear risk of bias (Alpsoy 2002; Masuda 1989). In one of these trials (Alpsoy 2002) it was unclear if both the intervention group and the control group received additional analgesia, which in turn could potentially affect the pain outcomes. In the other (Masuda 1989) it was unclear if additional topical therapies had been used. One trial was judged to be at high risk of bias due to concomitant systemic interventions being used (Davies 1988).

Effects of interventions

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Summary of findings: topical interventions.

| Topical interventions compared to placebo for managing oral ulcers in Behç̧et's disease | |

|

Patient or population: people with Behçet's disease Settings: primary care Intervention: topical interventions Comparison: placebo | |

| Outcomes | Comments |

| Pain associated with oral ulcers | 5 placebo‐controlled trials evaluated topical interventions (sucralfate suspension (2 trials), interferon–alpha (2 trials), cyclosporin A (1 trial). The quality of the evidence ranged from low to very low1 and there is insufficient evidence to support or refute the use of any evaluated intervention for oral ulcers in Behçet’s disease |

| Episode duration associated with oral ulcers | |

| Episode frequency associated with oral ulcers | |

| Safety of the intervention including adverse effects | |

1Studies downgraded for risk of bias and imprecision. Applicability, indirectness and publication bias were not considered to be of concern.

Summary of findings 2. Summary of findings: systemic interventions.

| Systemic interventions compared to placebo for managing oral ulcers in Behçet's disease | |

|

Patient or population: people with Behçet's disease Settings: primary care Intervention: systemic interventions Comparison: placebo | |

| Outcomes | Comments |

| Pain associated with oral ulcers | 8 placebo‐controlled trials evaluated topical interventions (aciclovir (1 trial), thalidomide (1 trial), corticosteroids (1 trial), rebamipide (1 trial), etanercept (1 trial), colchicine (2 trials), interferon–alpha (1 trial)). The quality of the evidence ranged from moderate1 to very low2 and there is insufficient evidence to support or refute the use of any evaluated intervention for oral ulcers in Behçet’s disease |

| Episode duration associated with oral ulcers | |

| Episode frequency associated with oral ulcers. | |

| Safety of the intervention including adverse effects | |

1Yurdakul 2001 downgraded for imprecision alone. 2Studies downgraded for risk of bias and imprecision. Applicability, indirectness and publication bias were not considered to be of concern.

Topical interventions

Six of the 15 included trials involved topical interventions. Five were placebo controlled (Table 1) and one made a head‐to‐head comparison.

Placebo‐controlled trials

Sucralfate

Two trials looked at sucralfate suspension versus placebo (Alpsoy 1999; Koc 1992). We were unable to pool the results as the mode of delivery of sucralfate differed between the studies (in one it was used as a mouthwash and in the other it was applied topically to ulcers). The trial by Alpsoy 1999 compared sucralfate suspension versus placebo suspension to be used as a mouthwash for two to four minutes after routine oral care and before bed. It included 40 participants and analysed results for 30. It had an unclear risk of selection bias (both for random sequence generation and allocation concealment). The results showed that sucralfate significantly decreased the mean frequency, healing time, and pain in comparison to baseline. However, no statistically significant differences were observed between the intervention and placebo for any of the oral ulcer outcomes at either end of treatment (three months) or end of follow‐up (six months) (Table 3). The trial by Koc 1992 included 41 participants (data evaluated for 35) and was at high risk of bias due to incomplete outcome data. It compared the sucralfate suspension and placebo suspension applied to oral ulcers four times a day. No statistically significant differences in number of painful days, number of episodes, or mean duration of episodes were seen at either the end of treatment or end of follow‐up (Table 3).

1. Sucralfate versus placebo (topical application).

| Sucralfate | Placebo | |||||||||

| Study | Outcome | Time point | Mean | Standard deviation | N | Mean | Standard deviation | N | Mean difference [95% CI] | P value |

| Alpsoy 1999 | Frequency of oral ulcer | End of treatment | 3.56 | 1.3 | 16 | 4.36 | 2.2 | 14 | ‐0.80 [‐2.12, 0.52] | 0.23 |

| End of follow up | 3.81 | 2.1 | 16 | 3.57 | 1.9 | 14 | 0.24 [‐1.19, 1.67] | 0.74 | ||

| Alpsoy 1999 | Healing time | End of treatment | 7.19 | 1.9 | 16 | 8.28 | 2.3 | 14 | ‐1.09 [‐2.61, 0.43] | 0.16 |

| End of follow up | 8.31 | 2.5 | 16 | 9.28 | 2.9 | 14 | ‐0.97 [‐2.92, 0.98] | 0.33 | ||

| Alpsoy 1999 | Pain | End of treatment | 0.69 | 0.5 | 16 | 1.07 | 0.8 | 14 | ‐0.38 [‐0.87, 0.11] | 0.12 |

| End of follow up | 1.47 | 0.5 | 16 | 1.28 | 0.6 | 14 | 0.19 [‐0.21, 0.59] | 0.35 | ||

| Koc 1992 | Number of painful days | End of treatment | 37.5 | 17.6 | 24 | 28.5 | 19.0 | 11 | 9.00 [‐4.25, 22.25] | 0.18 |

| End of follow up | 38.5 | 19.5 | 24 | 34.9 | 23.2 | 11 | 3.60 [‐12.17, 19.37] | 0.65 | ||

| Koc 1992 | Number of episodes | End of treatment | 6.4 | 2.5 | 24 | 5.0 | 2.0 | 11 | 1.40 [‐0.15, 2.95] | 0.08 |

| End of follow up | 6.5 | 2.0 | 24 | 5.5 | 1.3 | 11 | 1.00 [‐0.11, 2.11] | 0.08 | ||

| Koc 1992 | Mean duration of episodes | End of treatment | 10.3 | 8.3 | 24 | 11.3 | 5.6 | 11 | ‐1.00 [‐5.69, 3.69] | 0.68 |

| End of follow up | 8.9 | 6.9 | 24 | 8.2 | 2.99 | 11 | 0.70 [‐2.56, 3.96] | 0.68 | ||

There was insufficient evidence to support or refute the use of sucralfate suspension for oral ulcers in Behcet’s disease.

Interferon‐alpha

Two placebo‐controlled trials studied the effect of topical interferon‐alpha (Hamuryudan 1991; Kilic 2009). Both had a high risk of bias for selective reporting. The trial of 63 patients (61 evaluated) by Hamuryudan 1991 compared interferon–alpha 2c as a hydrogel versus placebo hydrogel. Patients applied a thin layer on any ulcer three times a day for 24 weeks. A similar application was made to the upper and lower lip mucosa irrespective of the presence of ulcers. No statistically significant difference was shown for the total number of ulcers throughout the treatment period (Table 4).

2. Interferon‐alpha versus placebo (topical).

| Interferon‐alpha | Placebo | |||||||||

| Study | Outcome | Time point | Mean | Standard deviation | n | Mean | Standard deviation | n | Mean difference [95% CI] | P value |

| Hamuryudan 1991 | Total ulcers | Duration of treatment (24 weeks) | 41.8 | 24.5 | 30 | 40.3 | 23.0 | 31 | 1.50 [‐10.43, 13.43] | 0.81 |

The Kilic 2009 trial compared two different dosages of interferon‐alpha lozenges (1000 IU versus 2000 IU) versus placebo in 84 patients. The data presented did not allow for analysis, however the authors reported no statistically significant difference between the total ulcer burden of the intervention (at either evaluated dosage) and placebo groups.

There was insufficient evidence to support the use of interferon‐alpha as a topical treatment for oral ulcers in Behçet’s disease.

Cyclosporin A

The trial by Ergun 1997 compared cyclosporin A in orabase (70 mg/g of orabase) versus placebo (orabase) in 24 patients. It had a high risk of reporting bias. No data were presented, however the authors reported no clinical improvement in the number, size, and healing time for either group. No adverse effects were seen.

There was insufficient evidence to support or refute the use of cyclosporin A in orabase as a treatment for oral ulcers in Behçet’s disease at the dose evaluated.

Head‐to‐head trials

The trial by Fani 2012 included 60 participants and it compared triamcinolone acetonide 0.1% ointment versus phenytoin syrup mouthwash (30 mg in 5 ml). The triamcinolone group applied the ointment to the lesions three times a day. The phenytoin group used two teaspoons of syrup in half a glass of warm water as a mouthwash for four to five minutes, three times a day. The trial had a high risk of reporting bias. The outcome measure of 'positive response' was not described, however a statistically significant difference was shown in favour of triamcinolone acetonide over phenytoin syrup (risk ratio (RR) 1.63, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.13 to 2.34; P = 0.009) (Table 5).

3. Triamicinolone acetonide versus phenytoin.

| Triamicinolone acetonide | Phenytoin | |||||||

| Study | Outcome | Time point | Number with event | N | Number with event | N | RR (95% CI) | P value |

| Fani 2012 | Positive response | 7 days | 26 | 30 | 16 | 30 | 1.63 [1.13, 2.34] | 0.009 |

There was insufficient evidence from this single study to support or refute the use of either phenytoin syrup mouthwash or triamcinolone acetonide as a treatment for oral ulcers in Behçet’s disease.

Systemic interventions

Nine of the 15 trials evaluated systemic interventions. Eight out of the nine were placebo controlled (Table 2) and one trial was head to head.

Placebo‐controlled trials

Aciclovir

One trial of 36 patients compared acyclovir versus placebo (Davies 1988). The patients were given 800 mg of acyclovir five times a day for one week, followed by 400 mg twice a day for 11 weeks. Patients also received various concomitant treatments. The trial had a high risk of reporting bias. Data weren't presented in a usable format, however the authors reported no statistically significant difference in frequency of oral ulcers between groups.

There was insufficient evidence to support or refute the use of acyclovir as a treatment for oral ulcers in Behcet’s disease at the dose evaluated.

Thalidomide

One trial recruiting 101 patients compared thalidomide 300 mg daily versus 100 mg daily versus daily placebo (Hamuryudan 1998). It had a high risk of reporting bias. It included only male patients. The authors reported a significant effect on mean numbers of minor oral ulcers from week four of treatment in both thalidomide groups, however oral ulcer data were not presented separate from genital ulcer data. The treatment effect diminished on stopping treatment. There was no reported difference between the 100 mg and 300 mg dosages on oral ulcers. There were significant adverse effects including severe sedation, polyneuropathy, loss of libido, and weight gain. A greater number of adverse events was seen for the higher dose of thalidomide. Four patients withdrew from the study due to side effects (all from the intervention arm).

There was insufficient evidence to support or refute the use of thalidomide (at either 300 mg or 100 mg daily) as a treatment for oral ulcers in Behçet’s disease.

Corticosteroids

One trial compared intramuscular depot injections of corticosteroids versus saline placebo injections in 86 patients (Mat 2006). The primary aim of the study was to manage genital ulceration in Behçet’s disease however they did report on oral ulcers. Patients received 40 mg methylprednisolone by intramuscular injection versus a placebo intramuscular injection every 3 weeks for 27 weeks. The trial had a high risk of reporting bias. Various concomitant treatments were used including colchicine, amitriptyline, non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs, and thalidomide. No statistically significant difference between groups was shown with regard to oral ulceration (Table 6).

4. Depot corticosteroids versus placebo (systemic).

| Depot corticosteroids | Placebo | |||||||||

| Study | Outcome | Time point | Mean | Standard deviation | N | Mean | Standard deviation | N | Mean difference [95% CI] | P value |

| Mat 2006 | Mean number of oral ulcers | End of treatment (week 27) | 1.8 | 1.0 | 41 | 1.8 | 1.2 | 44 | 0.00 [‐0.47, 0.47] | 1.00 |

| End of follow‐up (week 35) | 1.9 | 1.6 | 34 | 2.0 | 2.3 | 40 | ‐0.10 [‐0.99, 0.79] | 0.83 | ||

There was insufficient evidence to support or refute the use of intramuscular depot injections of corticosteroids, at the dose evaluated, as a treatment for oral ulcers in Behçet’s disease.

Rebamipide

One trial of 35 patients compared 300 mg daily rebamipide versus placebo (Matsuda 2003). It had a high risk of reporting bias. Concomitant treatments were allowed but insufficient details were presented to allow full interpretation of the results. The authors stated that rebamipide improved the global evaluation aphthae count and global evaluation pain score in Behçet’s disease; data were not presented in a form to confirm or refute this statement.

There was insufficient evidence to support or refute the use of rebamipide, at the dose evaluated, as a treatment for oral ulcers in Behçet’s disease.

Etanercept

The trial by Melikoglu 2005 included 40 participants who received either etanercept 25 mg subcutaneously or placebo subcutaneously twice a week for four weeks. It included only males. There was a high risk of reporting bias. The authors reported a statistically significant difference in mean number of oral ulcers with etanercept (weeks one, two, three, and four). The data presented did not allow this statistically significant result to be confirmed at week four. The statistically significant effects disappeared in the follow‐up period.

There was insufficient evidence to support or refute the use of etanercept as a treatment for oral ulcers in Behçet’s disease at the dose evaluated.

Colchicine

Two trials compared colchicine with placebo. One trial of 116 patients compared colchicine (0.5 mg, dose adjusted per weight in kg) versus placebo (Yurdakul 2001). The trial was at overall low risk of bias. The trial authors provided additional data; and no significant difference was noted on the outcome of oral ulcers (Table 7). An earlier trial, of 35 patients compared 0.5 mg colchicine, three times a day for six months, with placebo. The colchicine capsule also contained 60 mg of amidone and 40 mg lactose. The placebo contained a diarrhoea producing agent, phenolphtalein. No difference was shown with regard to improvement in RAS (Table 7).

5. Colchicine versus placebo (systemic).

| Colchicine | Placebo | |||||||||

| Study | Outcome | Time point | Mean | Standard deviation | N | Mean | Standard deviation | N | Mean difference [95% CI] | P value |

| Yurdakul 2001* | Total number of ulcers | 24 months | 23.2 | 17.1 | 57 | 20.9 | 14.0 | 58 | 2.30 [‐3.42, 8.02] | 0.43 |

| Study | Outcome | Time point | Number with event | N | Number with event | N | RR (95% CI) | P value | ||

| Aktulga 1980 | Improvement in oral ulcer score | 6 months | 9 | 14 | 12 | 14 | 0.75 [0.48, 1.17] | 0.21 | ||

*data supplied by author

There was insufficient evidence to support or refute the use of colchicine as a treatment for oral ulcers in Behçet’s disease.

Interferon‐alpha

The trial by Alpsoy 2002 compared subcutaneous injections of interferon–alpha (6 x 106 IU) versus placebo subcutaneous injections in 50 patients. The treatment was given three times a week for three months and the patients were followed up for a further three months. The trial had a high risk of reporting bias. Data were not presented in a useable format, however the authors reported a statistically significant decrease in the duration and pain of oral ulceration. There was a high rate of adverse events including alopecia, leukopenia, and diarrhoea and 18 out of 23 patients experienced mild flu like symptoms in the treatment arm.

There was insufficient evidence to support or refute the use subcutaneous Interferon–alpha as a treatment for oral ulcers in Behçet’s disease at the dose evaluated.

Head‐to‐head trials

One trial compared cyclosporin (10 mg/kg per day) to colchicine (1 mg daily) for 16 weeks for the management of ocular manifestations of Behçet’s disease (Masuda 1989). It included 96 patients (92 evaluated) and also reported on oral ulcers. It had a high risk of reporting bias. The results showed that cyclosporin alleviated oral aphthous ulceration in 70% compared to 20% in the colchicine group (RR 3.3, 95% CI 1.85 to 5.88; P < 0.0001). There were multiple adverse events in the cyclosporin arm and three patients withdrew and nine had a dose reduction as a result (Table 8).

6. Cyclosporin versus colchicine (systemic).

| Ciclosporin | Colchicine | |||||||

| Study | Outcome | Time point | Number with event | N | Number with event | N | RR (95% CI) | P value |

| Masuda 1989 | Alleviation of oral aphthous ulcers | Unclear | 33 | 46 | 10 | 46 | 3.3 [1.85, 5.88] | <0.0001 |

There was insufficient evidence to support or refute the use of cyclosporin (10 mg/kg per day) or colchicine (1 mg daily) as a treatment for oral ulcers in Behçet’s disease at the doses evaluated.

Discussion

Summary of main results

Fifteen randomised controlled trials (RCTs) were included in this review, evaluating the effectiveness of 13 different interventions for the management of oral ulcers in Behçet’s disease. There was considerable heterogeneity in the types of interventions evaluated and the way in which the interventions were used. Many of the trials specifically looked at oral ulcers as the primary outcome (six out of 15 trials), however for some of the studies the primary outcomes were related to other manifestations of Behçet's disease or the holistic management of Behçet's disease and the oral aspects were only reported as a secondary outcome.

The outcome measures evaluated and the timing of outcome measures varied widely. Some studies reported on individual ulcer data (size and number of ulcers), some on episodes (number of episodes, number of days with ulcers, number of days with no ulcers), and not all trials reported on pain as an outcome. Three of the 15 trials did not report adverse events or side effects and therefore the safety of the intervention used could not be assessed. Some studies reported data at the end of treatment and some at the end of follow‐up. This is of particular clinical relevance as many of the interventions were shown to be beneficial whilst actively on treatment, but on stopping treatment the positive results were not sustained. This would mean that patients would potentially require long‐term active treatment.

Twelve of the 15 trials were placebo controlled. There were three head‐to‐head trials. In the head‐to‐head trial by Fani et al (Fani 2012) no placebo was used. It is possible that the triamcinolone acetonide ointment was being used as an 'active placebo' or as a 'standard treatment' or 'usual treatment' arm, however there is no clear evidence from this review that triamcinolone is any better than placebo or no treatment for recurrent aphthous stomatitis (RAS)‐type ulceration in Behçet's disease. Without a placebo arm to the trial, it is theoretically possible that the benefit shown by the triamcinolone acetonide ointment was because the phenytoin syrup made the symptoms of the RAS‐type ulcers worse. Further evidence for the use of topical steroids including triamcinolone acetonide for the management of RAS will be available in the ongoing Cochrane review 'Topical interventions for the management of recurrent aphthous stomatitis' (Taylor 2013).

There was insufficient evidence to support or refute the use of any evaluated interventions for the management of oral ulcers in Behçet's disease.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

The diagnosis of Beḩcet's disease was not described clearly in all of the studies. Most trials used the International Study Group criteria for Behçet's disease (ISG 1990). The two studies from Japan used the Japanese diagnostic criteria, which were only described in detail in one of the trials. One trial used the O'Duffy criteria (Aktulga 1980).

Eleven of the trials were from Turkey and seven of these were from Istanbul, Turkey. Although this may represent the high prevalence of Behçet's disease in that area it also gives a heavy weighting to the evidence from one particular group.

As stated previously, many RCTs are carried out for the treatment of Behç̧et's disease and not all of them report on the oral outcomes. Where a study reported an oral outcome but this was not pre‐specified in the methodology, the study was excluded. This was to avoid ad hoc reporting of results after the trial was finished. It is important that as much information as possible is available for clinicians so they can plan their treatments appropriately. The heterogeneity of outcome measures used in trials for Behçet's disease was recently systematically reviewed by Hatemi et al (Hatemi, 2014). In the 18 included RCTs that they reviewed there were nine different oral outcome measurements used. This level of heterogeneity of outcome measures was also a feature in our review and meant that meta‐analysis was impossible.

There may be many treatments currently used for Behçet's disease which have a beneficial effect on oral ulcers, however until we have further evidence we can't recommend them for treating the oral ulcers of Behçet's disease.

There was a paucity of RCTs looking at anti‐TNF (tumour necrosis factor) treatments. Many of the anti‐TNF treatments have been evaluated in open studies. Anti‐TNF treatments have the potential to be used to manage the more serious and life threatening or organ threatening aspects of Behçet's disease. As a result of this, the oral aspects of Behçet's disease may not be reported as readily.

Oral ulceration is the most common sign and symptom of Behçet's disease and often pre‐dates other systemic involvement. As a result of this, many of the trials were primarily aimed at the management of oral ulceration (six out of the 15 trials). Of these six trials, five were for topical treatments. Whilst the oral aspects of Beḩcet's disease are not considered to be life threatening, they can cause significant morbidity and reduction of quality of life. None of the trials reported on these aspects.

Four of the studies looking at systemic interventions were aimed at orogenital disease and the remaining five studies were for the management of Behçet's disease. There are multiple trials of systemic treatments for Behçet's disease which did not fulfil our criteria for inclusion in this review as they did not report the oral aspects with pre‐specified oral outcome measures.

One trial has recently been completed and shows promising results for apremilast compared with placebo for oral ulcers (NCT00866359). Once fully available, the results of this trial will be incorporated in future updates of this review.

Quality of the evidence

One of the 15 trials was assessed as being at low risk of bias (Yurdakul 2001). One was at unclear risk of bias (Alpsoy 1999). The remainder were deemed as at high risk of bias. Of the 13 high risk of bias studies, 10 had a high risk of bias for reporting bias. The main issues with reporting bias were related to inadequate or incomplete reporting. Some studies did not report the pre‐specified outcomes, others reported a global evaluation of the outcomes but with no detailed data provided. Inappropriate use of graphs and tables which did not contain useable data was common. Some studies reported that separate analyses were carried out which confirmed their findings, but the separate analyses were never presented.

In previous times the space restrictions from some journals meant authors were required to condense their findings to conform to the limits stipulated. Fortunately in recent times there is the availability of an online supplement which means that all authors can make all the results available to the reader. In many of the studies a high risk of bias label for reporting bias could have been avoided if additional raw data had been available to this review group.

For topical interventions the quality of the evidence ranged from low to very low; for systemic interventions the quality of the evidence ranged from moderate to very low. The quality of the body of evidence was downgraded due to risk of bias and imprecision.

Potential biases in the review process

The review authors followed the guidelines for conducting this systematic review under the strictest of conditions (Higgins 2011). All abstracts were independently dual screened, and all papers were assessed and had the risk of bias assessment carried out by at least two independent authors. All papers were subsequently reviewed by five of the review authors. The findings were then discussed at a meeting with five of the authors including the three clinical authors.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

A previous Cochrane review has looked at pharmacotherapy for Beḩcet's syndrome (Saenz 1998). They included five trials for oral ulceration, four of which are included in this review. The fifth trial (Benamour 1991) was considered to be a controlled clinical trial and therefore not eligible for inclusion in this review. The review by Saenz et al also concluded that there was "insufficient evidence either to support or to refute some of the classic treatments for Behçet's syndrome". The current recommendations for the management of Behçet's disease were written by the EULAR (European League Against Rheumatism) group and published in 2008 (Hatemi, 2008). This multidisciplinary expert committee carried out a systematic review and presented their findings and recommendations according to the system involved in the disease. The management of oral ulcers is contained in the mucocutaneous section and states that "oral ulcers may be managed with topical preparations". The RCTs included in this review are all noted by the group, and additionally they make recommendations based on various open studies. Colchicine is a readily used systemic treatment in Beḩcet's disease and the authors state "Colchicine is widely used without any solid proof of its efficacy", which confirms the findings of the colchicine study included in this review (Yurdakul 2001)

Another recent review, 'Behçet's syndrome: Facts and Controversies' (Mat 2013), summarises the RCTS available and comments on the EULAR recommendations. Many of the RCTs described were carried out in the same department that the authors are from (Cerrahpsa medical facility, Istanbul). They also report that data from the open studies on the use of biologic agents is promising (interferon‐alpha, anti‐TNF). They conclude that "Local treatment for oral and genital ulcers is sufficient".

The findings of our systematic review indicate uncertainty on the effectiveness and safety of local and systemic treatment for oral ulcers.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Whilst there is no 'gold standard treatment' for the management of oral ulcers in Behçet's disease, there are a number of treatments which are currently used in practice.

In practice, topical treatments are generally used as first line therapy, however it is often necessary to consider systemic treatments for many patients. When patients have manifestations of Behçet's disease that may cause severe morbidity (for example blindness) or they have multiple morbidities, or they are life threatening, the clinical reasoning for stepping up the treatment to include potentially harmful systemic interventions may be justified. It may be a secondary beneficial outcome that the patient's oral symptoms also improve in these cases. However, there are some patients who do not have this level of severity of Behçet's disease but they do have severe oral ulceration which can cause significant morbidity and reduction of quality of life (eating, drinking, and speaking). For these patients, it is important that we have the best evidence to guide our clinical decision making.

This review found insufficient evidence to support or refute the use of any of the included topical or systemic interventions for the management of oral ulcers in Behçet's disease.

Implications for research.

This review was limited by the poor methodology of many of the trials, which in turn led to huge heterogeneity of outcome measures and timing of outcome measures, and inadequate reporting of results.Future trials for Beḩcet's disease should be appropriately planned, executed, and reported according to the CONSORT guidelines (www.consort‐statement.org). The interventions evaluated should be clinically relevant and the controls used should be appropriate. Cross‐over trials should have a washout period.

As oral ulcers are the most common feature of Behçet's disease, appropriate pre‐specified oral outcome measures should be used for all trials of interventions for Beḩcet's disease. The development of a set of standardised outcome measures for oral ulcer trials is registered with COMET (www.comet‐initiative.org). The use of an oral ulcer core outcome set when planning trials will allow homogeneity of outcomes for future systematic reviews. Hatemi et al are leading a group who are currently developing a core set of outcome measures for Behçet's disease (Hatemi, 2014), however there is no planned involvement of an oral ulcer related specialty in that group (that is oral medicine, oral surgery, or dentistry).

The inclusion of a quality of life assessment tool such as the Chronic Oral Mucosal Diseases Questionnaire (Riordain 2011) would be advantageous.

As many of the patients will require long term active treatment, the inclusion of an appropriate economic evaluation of the interventions would be appropriate. This could assess the cost effectiveness of treatments.

Further research into the following interventions is warranted:

thalidomide;

rebapamide;

etanercept;

and interferon‐alpha.

Further research would most likely change current clinical practice.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 21 November 2019 | Review declared as stable | This Cochrane Review is currently not a priority for updating. However, following the results of Cochrane Oral Health's latest priority setting exercise and if a substantial body of evidence on the topic becomes available, the review would be updated in the future. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 3, 2014 Review first published: Issue 9, 2014

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 12 August 2014 | Amended | Following peer review the wording around the definition of recurrent aphthous stomatitis (RAS) and RAS‐type ulceration has been clarified. This is an amendment to the protocol. |

Notes

This Cochrane Review is currently not a priority for updating. However, following the results of Cochrane Oral Health's latest priority setting exercise and if a substantial body of evidence on the topic becomes available, the review would be updated in the future

Acknowledgements

The review team would like to acknowledge Anne Littlewood, Jo Weldon, and Janet Lear for their help with the management of this review. We would also like to thank authors of trials for additional data provided.

Appendices

Appendix 1. MEDLINE (Ovid) search strategy

1. Behcet syndrome/ 2. (Behcet adj2 (syndrome$ or disease)).ti,ab. 3. ("triple‐complex syndrome$" or "triple‐complex disease$").ti,ab. 4. or/1‐3 5. Stomatitis, aphthous/ 6. ((aphthous or apthous or mouth$ or oral$) adj3 (ulcer$ or lesion$ or stomatitis)).ti,ab.˜ 7. (aphthae or apthae).ti,ab. 8. "canker sore$".ti,ab. 9. "herpetiform ulcer$".ti,ab. 10. "periadenitis mucosa necrotica recurrens".ti,ab. 11. or/5‐10 12. 4 and 11

The above subject search was linked with the Cochrane Highly Sensitive Search Strategy (CHSSS) for identifying randomised trials in MEDLINE: sensitivity maximising version (2008 revision) as referenced in Chapter 6.4.11.1 and detailed in box 6.4.c of theCochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011] (Higgins 2011).

1. randomized controlled trial.pt. 2. controlled clinical trial.pt. 3. randomized.ab. 4. placebo.ab. 5. drug therapy.fs. 6. randomly.ab. 7. trial.ab. 8. groups.ab. 9. or/1‐8 10. exp animals/ not humans.sh. 11. 9 not 10

Appendix 2. The Cochrane Oral Health Group Trials Register search strategy

(((Behcet* and disease*) or (Behcet* and syndrome*)):ti,ab) AND (INREGISTER)

((("triple‐complex syndrome*" or "triple‐complex disease*")):ti,ab) AND (INREGISTER)

MeSH DESCRIPTOR Behcet Syndrome

(#1 or #2 or #3) AND (INREGISTER)

Appendix 3. The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) search strategy

#1 [mh "Behcet syndrome"] #2 (behcet near/2 syndrome*) or (behcet near/2 disease*) #3 ("triple‐complex syndrome*" or "triple‐complex disease*") #4 {or #1‐#3} #5 [mh "Stomatitis, aphthous"] #6 ((aphthous or apthous or mouth* or oral*) and (ulcer* or lesion* or stomatitis)) #7 (aphthae or apthae) #8 "canker sore*" #9 "herpetiform ulcer*" #10 "periadenitis mucosa necrotica recurrens" #11 {or #5‐#10} #12 #4 and #11

Appendix 4. EMBASE (Ovid) search strategy

1. Behcet disease/ 2. (Behcet adj2 (syndrome$ or disease)).ti,ab. 3. ("triple‐complex syndrome$" or "triple‐complex disease$").ti,ab. 4. or/1‐3 5. Stomatitis, aphthous/ 6. ((aphthous or apthous or mouth$ or oral$) adj3 (ulcer$ or lesion$ or stomatitis)).ti,ab. 7. (aphthae or apthae).ti,ab. 8. "canker sore$".ti,ab. 9. "herpetiform ulcer$".ti,ab. 10. "periadenitis mucosa necrotica recurrens".ti,ab. 11. or/5‐10 12. 4 and 11

The above subject search was linked to the Cochrane Oral Health Group filter for identifying RCTs in EMBASE via OVID:

1. random$.ti,ab. 2. factorial$.ti,ab. 3. (crossover$ or cross over$ or cross‐over$).ti,ab. 4. placebo$.ti,ab. 5. (doubl$ adj blind$).ti,ab. 6. (singl$ adj blind$).ti,ab. 7. assign$.ti,ab. 8. allocat$.ti,ab. 9. volunteer$.ti,ab. 10. CROSSOVER PROCEDURE.sh. 11. DOUBLE‐BLIND PROCEDURE.sh. 12. RANDOMIZED CONTROLLED TRIAL.sh. 13. SINGLE BLIND PROCEDURE.sh. 14. or/1‐13 15. (exp animal/ or animal.hw. or nonhuman/) not (exp human/ or human cell/ or (human or humans).ti.) 16. 14 NOT 15

Appendix 5. CINAHL (EBSCO) search strategy

S1 (MH "Beḩcet's Syndrome") S2 (behcet N2 syndrome*) or (behcet N2 disease*) S3 ("triple‐complex syndrome*" or "triple‐complex disease*") S4 S1 or S2 or S3 S5 (MH "Stomatitis, Aphthous") S6 ((aphthous or apthous or mouth* or oral*) and (ulcer* or lesion* or stomatitis)) S7 (aphthae or apthae) S8 "canker sore*" S9 "herpetiform ulcer*" S10 "periadenitis mucosa necrotica recurrens" S11 S5 or S6 or S7 or S8 or S9 or S10 S12 S4 and S11

The above subject search was linked to the Cochrane Oral Health Group filter for identifying RCTs in CINAHL via EBSCO:

S1 MH Random Assignment or MH Single‐blind Studies or MH Double‐blind Studies or MH Triple‐blind Studies or MH Crossover design or MH Factorial Design S2 TI ("multicentre study" or "multicenter study" or "multi‐centre study" or "multi‐center study") or AB ("multicentre study" or "multicenter study" or "multi‐centre study" or "multi‐center study") or SU ("multicentre study" or "multicenter study" or "multi‐centre study" or "multi‐center study") S3 TI random* or AB random* S4 AB "latin square" or TI "latin square" S5 TI (crossover or cross‐over) or AB (crossover or cross‐over) or SU (crossover or cross‐over) S6 MH Placebos S7 AB (singl* or doubl* or trebl* or tripl*) or TI (singl* or doubl* or trebl* or tripl*) S8 TI blind* or AB mask* or AB blind* or TI mask* S9 S7 and S8 S10 TI Placebo* or AB Placebo* or SU Placebo* S11 MH Clinical Trials S12 TI (Clinical AND Trial) or AB (Clinical AND Trial) or SU (Clinical AND Trial) S13 S1 or S2 or S3 or S4 or S5 or S6 or S9 or S10 or S11 or S12

Appendix 6. AMED (Ovid) search strategy

1. ((behcet and syndrome$) or (behcet and disease$)).ti,ab. 2. ("triple‐complex syndrome$" or "triple‐complex disease$").ti,ab. 3. or/1‐2 4. ((aphthous or apthous or mouth$ or oral$) adj3 (ulcer$ or lesion$ or stomatitis)).ti,ab. 5. (aphthae or apthae).ti,ab. 6. "canker sore$".ti,ab. 7. "herpetiform ulcer$".ti,ab. 8. "periadenitis mucosa necrotica recurrens".ti,ab. 9. or/4‐8 10. 3 and 9

Appendix 7. US National Institutes of Health Trials Register (ClinicalTrials.gov) and WHO Clinical Trials Registry Platform search strategy

Behcet* and oral and ulcer* Behcet* and mouth and ulcer* Behcet* and stomatitis

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Aktulga 1980.

| Methods | Study design: RCT parallel Trial MD: NS Conducted in: Turkey Number of centres: 1 Recruitment period: NS Sample size calculation undertaken and met: not mentioned |

|

| Participants | Source of recruitment: NS Age GrA: 34.2 years ±7.2 Age GrB: 33 years ±12.8 Gender (overall sample): 6F/22M Gender GrA: 5F/9M Gender GrB: 1F/13M Inclusion criteria: well defined Behcet’s disease according to the O’Duffy criteria Exclusion criteria: NS Number randomised: 35 Number evaluated: 28 |

|

| Interventions |

Comparison: colchicine versus placebo GrA (n = 14): capsules containing colchicine 0.5 mg, lactose 40 mg, amidone, 60 mg taken tds GrB (n = 14): placebo capsules containing phenolphthalein 60 mg, lactose 40 mg tds (decreased to bd if diarrhoea a problem) |

|

| Outcomes | Primary outcomes (patients seen monthly): semiquantitative assessment of 0‐3 for aphthous stomatitis Carried out monthly for 6 months No reporting of adverse events, quality of life or cost |

|

| Funding | Supported in part by Turkish and Technical research council (TAG 386) | |

| Notes | Comparable groups at baseline: no information in study | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: "were randomised" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "the code was known to a local pharmacist who dispensed the medication according to our instructions" |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | Quote: "identical capsules" Placebo group were informed to decrease dose from 3 times a day to twice daily if diarrhoea a problem |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | Given different instructions provided to the 2 treatment arms, blinding unlikely |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | 7 dropouts no details given (evenly distributed) |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient details given for outcome measurements, who was assessing and interassessor calibration |

| Other bias | Low risk | None apparent |

Alpsoy 1999.

| Methods | Study design: RCT (parallel) Trial ID: NS Conducted in: Turkey Number of centres: NS Recruitment period: NS Sample size calculation undertaken and met: NS |

|

| Participants | Source of recruitment: NS Age (overall sample): 33.4 years (SD 7.61) Age GrA: 33.0 years (SD 9.0) Age GrB: 34.1 years (SD 5.3) Gender (overall sample): 14 F/16 M Gender GrA: 8 F/8 M Gender GrB: 6 F/8 M Inclusion criteria: diagnosed according to the criteria of International Study Group for Behçet's disease Exclusion criteria: active eye disease or organ involvement requiring systemic therapy or received recent systemic therapy for at least 12 weeks and topical therapy for at least 4 weeks prior to the study Number randomised: 40 (20:20) Number evaluated: 30 (16:14) |

|

| Interventions |

Comparison: sucralfate suspension versus placebo GrA (n = 16): 5 mL of sucralfate to use as an oral rinse for 1 to 2 minutes after routine mouth care and before sleep GrB (n = 14): as for sucralfate 3 months treatment; 3 months follow‐up |

|

| Outcomes | Mean frequency of lesion Healing time Pain (scale of 0 to 3 (0, absent; 1, mild; 2, moderate; and 3, severe)) Adverse events No reporting of quality of life or cost |

|

| Funding | NS | |

| Notes | Comparable groups at baseline: yes Treatment for oral and genital lesions |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient information |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient information |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Quote: "The clinical investigator (H.E.) and patients were unaware of the specific drugs that the patients were taking during the course of the study" Comment: placebo identical in appearance |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Quote: "The clinical investigator (H.E.) and patients were unaware of the specific drugs that the patients were taking during the course of the study" |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Quote: "The clinical investigator (H.E.) and patients were unaware of the specific drugs that the patients were taking during the course of the study" |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | 10 patients (4 sucralfate‐treated patients and 6 placebo‐treated patients) failed to complete the study. In all patients, medication use was well tolerated, and no patients were withdrawn from the study because of adverse events. High dropout but reasons and numbers similar across groups |

| Other bias | Low risk | None apparent |

Alpsoy 2002.