In the recent paper by Chu and colleagues,1 the potential role of microbiota-related metabolites in the progression of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease is discussed. This topic has been studied in the context of chronic kidney disease (CKD), characterised by changes in gut microbiota composition,2 accumulation of microbiota-derived metabolites,3 interruption of intestinal barrier function and chronic inflammation.4 In line with this, we focused, in a cohort of 17 patients with end-stage kidney disease (ESKD), on the role of gut microbiota in the generation of precursors of specific uraemic toxins which are associated with negative outcomes in these patients.5 By collecting multiple samples over time, assessment of variability within and between patients in relation to disease progress and clinical variables was possible. Faecal and serum samples were collected at eight time-points over a 4-month period (online supplementary table 1). Uraemic metabolites and microbial profiling were determined by HPLC and 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing, respectively (see Supplementary data). Variation in microbial profiles of patients with ESKD was compared with that of 1106 subjects from a population-based cohort, the Flemish Gut Flora Project (FGFP),6 which have a similar genetic and environmental background as well as to a subset of age-matched controls of comparable health status (n=32).

gutjnl-2018-317561supp001.pdf (980.1KB, pdf)

In this longitudinal study, within-patient analyses showed that variations in peripheral levels of p-cresyl conjugates (the composite of p-cresyl sulfate (pCS)/glucuronide (pCG); pC), indoxyl sulfate (IxS), indole acetic acid and creatinine7 significantly correlated with faecal microbial community dissimilarity (at 0.05 level after Benjamini-Hochberg correction). Moreover, the composition of the gut microbiota was found to be diverse among patients with ESKD without a common microbial signature. A significantly higher variability of the patients’ microbiome was observed in comparison to average subject-to-subject differences, even when matching for age and health status (both p<0.0001) (online supplementary figure S1). Projecting the patients’ samples on the PCoA plot of the FGFP confirmed that these patients do not cluster in a specific area but rather are dispersed over the entire space of the control population (online supplementary figure S2).

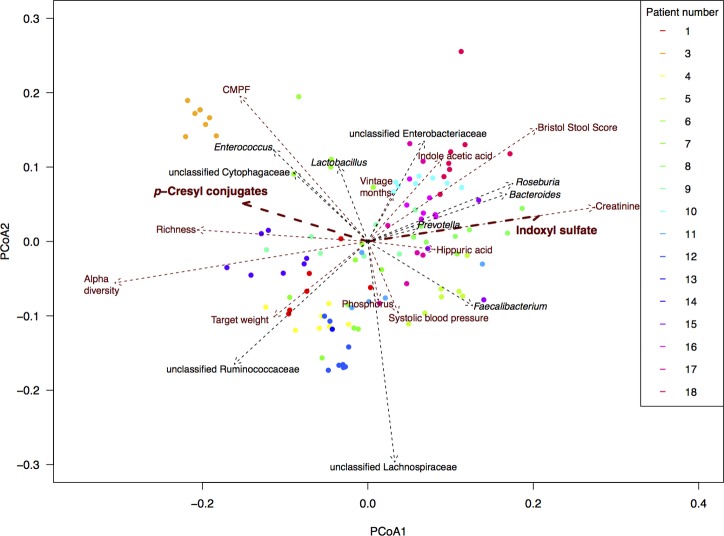

Covariate analyses of the intestinal microbiota composition in ESKD resulted in non-redundant parameters that significantly correlated with the overall composition, with length of scaled arrows reflecting correlation as depicted in figure 1 (list of covariates in online supplementary table 2 and figure S3). When focusing on the relationships between uraemic retention molecules and gut microbiota, significant correlations of two main uraemic toxins, IxS and pC, to the overall bacterial community composition (p<0.05 after multiple testing correction) stand out. Specifically, since they are associated with contrasting types of gut microbiota, as the arrows for IxS and pC pointed into an opposite direction. This, for the first time, provides a possible working hypothesis on the reported discordant effects of prebiotics, probiotics and synbiotics on circulating levels of these two toxins.8–10

Figure 1.

Main covariates of the faecal microbiota composition of patients with ESKD. Final selected numeric metadata in addition to top 10 taxa correlating with PCoA eigenvectors (ie, with overall community composition). Biplot computed with Bray Curtis dissimilarity on rarefied read counts. Length of arrows reflects correlation with overall community composition. Per patient, a different colour is used. CMPF, 3-carboxy-4-methyl-5-propyl-2-furanpropanoic acid; ESKD, end-stage kidney disease.

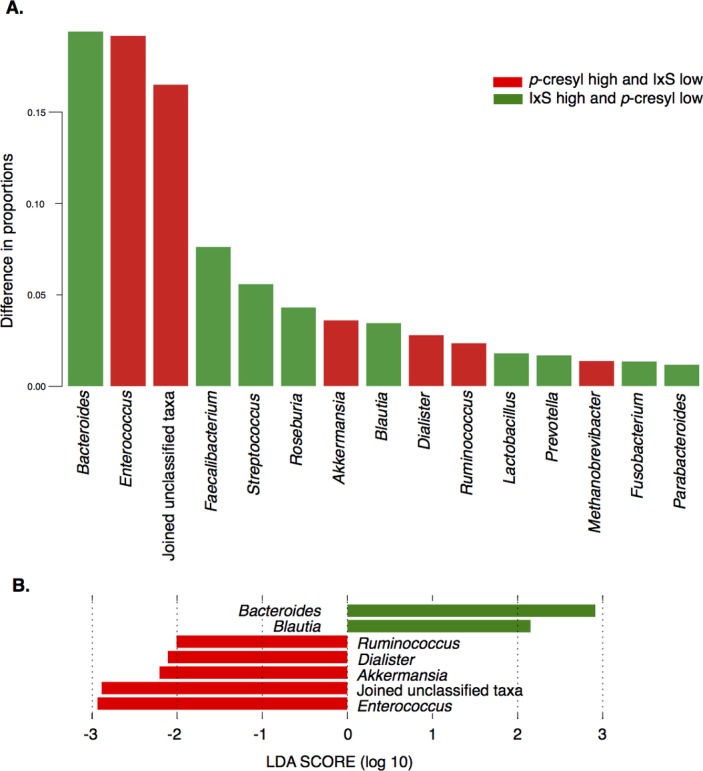

When further comparing samples of patients with highest pC and lowest IxS to samples with lowest pC and highest IxS serum concentrations in this cohort, the microbial composition of their faecal samples differed significantly. Taxon proportions that differed between both groups are visualised in figure 2A. The LEfSe method confirmed that both datasets were different and identified in total six significantly different taxa together with their effect sizes (figure 2B), all six overlapping with the top 10 taxa that we identified earlier.

Figure 2.

Associations between p-cresyl conjugates and indoxyl sulfate and intestinal microbiota, subcohort analysis. Faecal microbiota composition of samples with highest p-cresyl (pCS+pCG) and lowest IxS concentrations (group 1 in red) was compared with that of samples with highest IxS and lowest pC concentrations (group 2 in green). (A): The top 15 taxa with the largest difference between the two groups. Group-specific taxon proportion vectors were obtained by fitting the Dirichlet Multinomial distribution to each sample set (using R package HMP, function DM.MoM). The HMP package function Xmcupo.sevsample (Generalised Wald-type statistics) was used to compute whether the difference between the two taxon proportion vectors (highest pC/lowest IxS vs lowest pC/highest IxS) was significant (p<0.0001). (B) Effect sizes of genera that differed significantly between the datasets using LDA effect size (LEfSe). The length of the bar represents a log10 transformed LDA score. The colours represent in which group those taxa were found to be more abundant compared with the other group. Absolute values of the effect sizes should be used to interpret the scale of the difference between both groups. LDA, linear discriminant analysis.

Our results illustrate the implications of gut microbiota dynamics on chronic disease and underscore the potential difficulties with attempts to alter circulating levels of intestinally generated uraemic toxins and their corresponding toxicity through specific microbiota modulation. Nevertheless, six taxa are identified and can now be explored as microbial targets to lower uraemic toxin concentrations and to improve outcome of patients with CKD.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Maria Van Landschoot, Sophie Lobbestael, Tom Mertens and Leen Rymenans (partly supported by the same project grant) for their technical assistance, Willem Delrue (master student) for the assistance in the sample collection and Leo Lahti for health matching in the FGFP dataset. The authors also thank the dialysis patients of the Ghent University Hospital for their effort to take part in this study.

Footnotes

MJ, KF, TG, JR and GG contributed equally.

Contributors: GG, JR, MJ and GRBH made substantial contributions to conception and design of the study. TG, SE, ES, AD, AP and GG were involved in the acquisition of data. KF, MJ, TG, ATLN, JW and SV-S made substantial contributions to the analysis of the data. MJ, TG, GF, MV, GRBH, JR and GG were involved in the interpretation of the data. MJ, TG, KF and GG drafted the article. All authors critically revised the draft and made important intellectual contributions. All co-authors approved the final version to be published and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding: This study is supported by a project grant of the Research Foundation Flanders (FWO Vlaanderen; G0A4614N and G017815N). TG is a PhD student on this project. MJ is supported by a fellowship and AP is postdoctoral researcher of the Research Foundation-Flanders (FWO). The Raes lab is supported by KU Leuven, Flemish Life Science Research Institute (VIB) and the Rega Institute.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: Ethics Committee UZ Ghent (Approval Ref. 2012/063, B670201214999).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; internally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Chu H, Duan Y, Yang L, et al. Small metabolites, possible big changes: a microbiota-centered view of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Gut 2019;68:359–70. 10.1136/gutjnl-2018-316307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Vaziri ND, Wong J, Pahl M, et al. Chronic kidney disease alters intestinal microbial flora. Kidney Int 2013;83:308–15. 10.1038/ki.2012.345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Vanholder R, Glorieux G. Gut-derived metabolites and chronic kidney disease: the Forest (F)or the trees? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2018;13:1311–3. 10.2215/CJN.08200718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Anders HJ, Andersen K, Stecher B. The intestinal microbiota, a leaky gut, and abnormal immunity in kidney disease. Kidney Int 2013;83:1010–6. 10.1038/ki.2012.440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Barreto FC, Barreto DV, Liabeuf S, et al. Serum indoxyl sulfate is associated with vascular disease and mortality in chronic kidney disease patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2009;4:1551–8. 10.2215/CJN.03980609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Falony G, Joossens M, Vieira-Silva S, et al. Population-level analysis of gut microbiome variation. Science 2016352:560–4. 10.1126/science.aad3503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Eloot S, Van Biesen W, Roels S, et al. Spontaneous variability of pre-dialysis concentrations of uremic toxins over time in stable hemodialysis patients. PLoS One 2017;12:e0186010 10.1371/journal.pone.0186010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Meijers BK, De Preter V, Verbeke K, et al. p-Cresyl sulfate serum concentrations in haemodialysis patients are reduced by the prebiotic oligofructose-enriched inulin. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2010;25:219–24. 10.1093/ndt/gfp414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hida M, Aiba Y, Sawamura S, et al. Inhibition of the accumulation of uremic toxins in the blood and their precursors in the feces after oral administration of Lebenin, a lactic acid bacteria preparation, to uremic patients undergoing hemodialysis. Nephron 1996;74:349–55. 10.1159/000189334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rossi M, Johnson DW, Morrison M, et al. Synbiotics Easing Renal Failure by Improving Gut Microbiology (SYNERGY): a randomized trial. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2016;11:223–31. 10.2215/CJN.05240515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

gutjnl-2018-317561supp001.pdf (980.1KB, pdf)