Abstract

Green plants (Viridiplantae) include around 450,000–500,000 species1,2 of great diversity and have important roles in terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems. Here, as part of the One Thousand Plant Transcriptomes Initiative, we sequenced the vegetative transcriptomes of 1,124 species that span the diversity of plants in a broad sense (Archaeplastida), including green plants (Viridiplantae), glaucophytes (Glaucophyta) and red algae (Rhodophyta). Our analysis provides a robust phylogenomic framework for examining the evolution of green plants. Most inferred species relationships are well supported across multiple species tree and supermatrix analyses, but discordance among plastid and nuclear gene trees at a few important nodes highlights the complexity of plant genome evolution, including polyploidy, periods of rapid speciation, and extinction. Incomplete sorting of ancestral variation, polyploidization and massive expansions of gene families punctuate the evolutionary history of green plants. Notably, we find that large expansions of gene families preceded the origins of green plants, land plants and vascular plants, whereas whole-genome duplications are inferred to have occurred repeatedly throughout the evolution of flowering plants and ferns. The increasing availability of high-quality plant genome sequences and advances in functional genomics are enabling research on genome evolution across the green tree of life.

Subject terms: Molecular evolution, Adaptive radiation, Phylogenomics, Plant evolution

The One Thousand Plant Transcriptomes Initiative provides a robust phylogenomic framework for examining green plant evolution that comprises the transcriptomes and genomes of diverse species of green plants.

Main

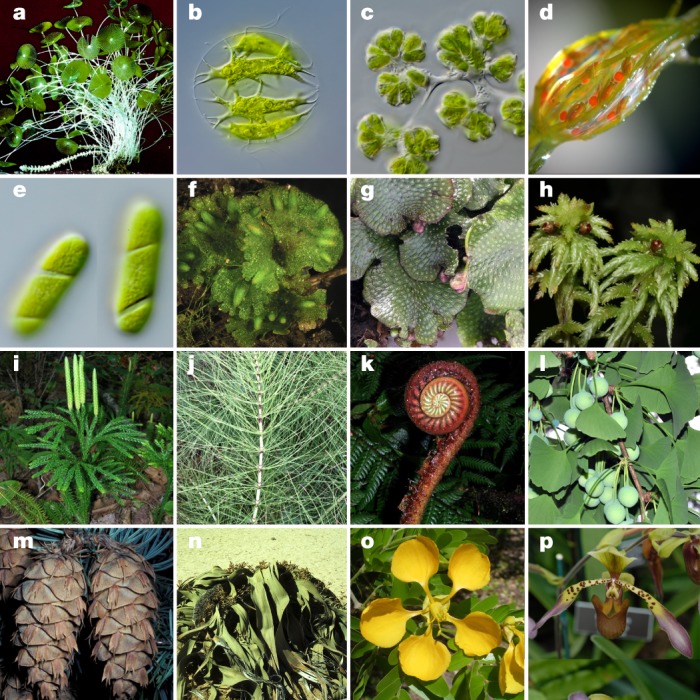

Viridiplantae comprise an estimated 450,000–500,000 species1,2, encompass a high level of diversity and evolutionary timescales3, and have important roles in all terrestrial and most aquatic ecosystems. This ecological diversity derives from developmental, morphological and physiological innovations that enabled the colonization and exploitation of novel and emergent habitats. These innovations include multicellularity and the development of the plant cuticle, protected embryos, stomata, vascular tissue, roots, ovules and seeds, and flowers and fruit (Fig. 1). Thus, plant evolution ultimately influenced environments globally and created a cascade of diversity in other lineages that span the tree of life. Plant diversity has also fuelled agricultural innovations and growth in the human population4.

Fig. 1. Diversity within the Viridiplantae.

a–e, Green algae. a, Acetabularia sp. (Ulvophyceae). b, Stephanosphaera pluvialis (Chlorophyceae). c, Botryococcus sp. (Trebouxiophyceae). d, Chara sp. (Charophyceae). e, ‘Spirotaenia’ sp. (taxonomy under review) (Zygnematophyceae). f–p, Land plants. f, Notothylas orbicularis (Anthocerotophyta (hornwort)). g, Conocephalum conicum (Marchantiophyta (thalloid liverwort)). h, Sphagnum sp. (Bryophyta (moss)). i, Dendrolycopodium obscurum (Lycopodiophyta (club moss)). j, Equisetum telmateia (Polypodiopsida, Equisetidae (horsetail)). k, Parablechnum schiedeanum (Polypodiopsida, Polypodiidae (leptosporangiate fern)). l, Ginkgo biloba (Ginkgophyta). m, Pseudotsuga menziesii (Pinophyta (conifer)). n, Welwitschia mirabilis (Gnetophyta). o, Bulnesia arborea (Angiospermae, eudicot, rosid). p, Paphiopedilum lowii (Angiospermae, monocot, orchid). a, Photograph reproduced with permission of Thieme Verlag, Stuttgart66. b–e, Photographs courtesy of M. Melkonian. f–j, l–n, p, Photographs courtesy of D.W.S. k, Photograph courtesy of R. Moran. o, Photograph courtesy of W. Judd.

Phylogenomic approaches are now widely used to resolve species relationships5 as well as the evolution of genomes, gene families and gene function6. We used mostly vegetative transcriptomes for a broad taxonomic sampling of 1,124 species together with 31 published genomes to infer species relationships and characterize the relative timing of organismal, molecular and functional diversification across green plants.

We evaluated gene history discordance among single-copy genes. This is expected in the face of rapid species diversification, owing to incomplete sorting of ancestral variation between speciation events7. Hybridization8, horizontal gene transfer9, gene loss following gene and genome duplications10 and estimation error can also contribute to gene-tree discordance. Nevertheless, through rigorous gene and species tree analyses, we derived robust species tree estimates (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Figs. 1–3). Gene-family expansions and genome duplications are recognized sources of variation for the evolution of gene function and biological innovations11,12. We inferred the timing of ancient genome duplications and large gene-family expansions. Our findings suggest that extensive gene-family expansions or genome duplications preceded the evolution of major innovations in the history of green plants.

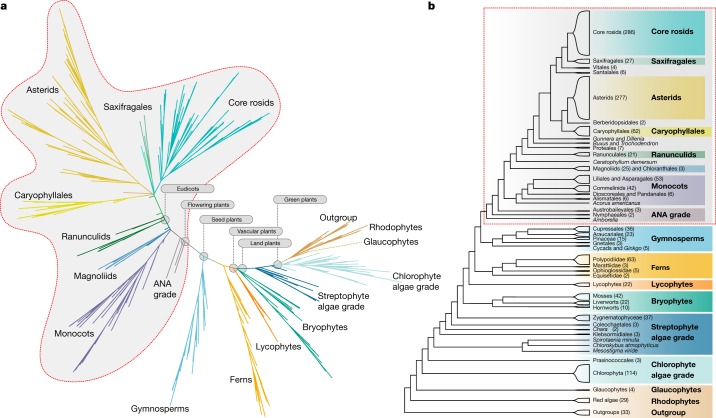

Fig. 2. Phylogenetic inferences of major clades.

Phylogenetic inferences were based on ASTRAL analysis of 410 single-copy nuclear gene families extracted from genome and transcriptome data from 1,153 species, including 1,090 green plant (Viridiplantae) species (Supplementary Table 1). a, Phylogram showing internal branch lengths proportional to coalescent units (2Ne generations) between branching events, as estimated by ASTRAL-II15 v.5.0.3. b, Relationships among major clades with red box outlining flowering plant clade. Species numbers are shown for each lineage. Most inferred relationships were robust across data types and analyses (Supplementary Figs. 1–3) with some exceptions (Supplementary Fig. 6). Data and analysis scripts are available at 10.5281/zenodo.3255100.

Integrated analysis of genome evolution

Because genome sizes vary by 2,340-fold in land plants13 and 4,680-fold in chlorophyte and streptophyte green algae14, we used a reduced-representation sequencing approach to reconstruct gene and species histories. Specifically, we generated 1,342 transcriptomes representing 1,124 species across Archaeplastida, including green plants, glaucophytes and red algae. Comparing phylogenetic inferences based on nuclear and plastid genes (Figs. 2, 3 and Supplementary Figs. 1–3), we obtained well-supported, largely congruent results across diverse datasets and analyses. Resolution of some relationships, however, was confounded by gene-tree discordance (Fig. 3), which is attributable to factors that include rapid diversification, reticulate evolution, gene duplication and loss, and estimation error.

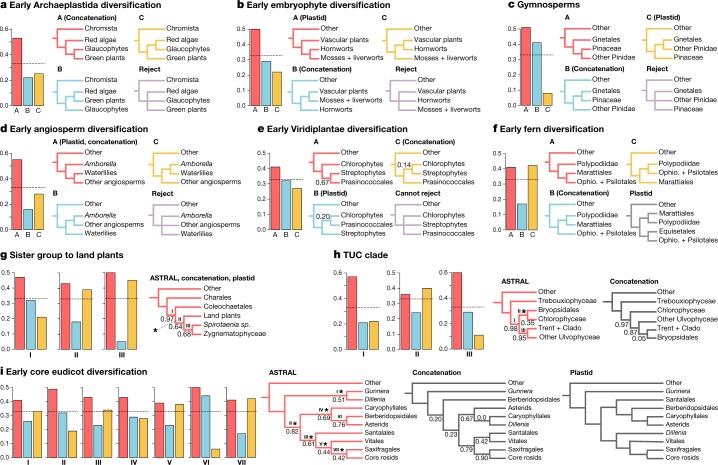

Fig. 3. Alternative branching orders for contentious relationships.

Local posterior probabilities (shown only when below 1.0) and gene-tree quartet frequencies (bar graphs) for alternative branching orders for contentious relationships in the plant phylogeny (see text). a, Early Archaeplastida diversification. b, Early embryophyte diversification. c, Gymnosperms. d, Early angiosperm diversification. e, Early Viridiplantae diversification. f, Early fern diversification. g, The sister lineage to land plants. h, Trebouxiophyceae, Ulvophyceae and Chlorophyceae. i, Eudicot diversification. Red bars represent the ASTRAL topology; blue and yellow trees and bars represent the frequencies of alternative branching orders in ASTRAL. The topologies recovered in the concatenated supermatrix analysis and plastid gene analyses are also indicated. Dashed horizontal lines mark expectation for a hard polytomy (purple). In g–i, panels include more than 4 tips, so nodes are delineated with Roman numerals and bar graphs are shown for each node and asterisks above branches indicate failure to reject the hypothesis that the node is a polytomy. Data and analysis scripts are available at 10.5281/zenodo.3255100.

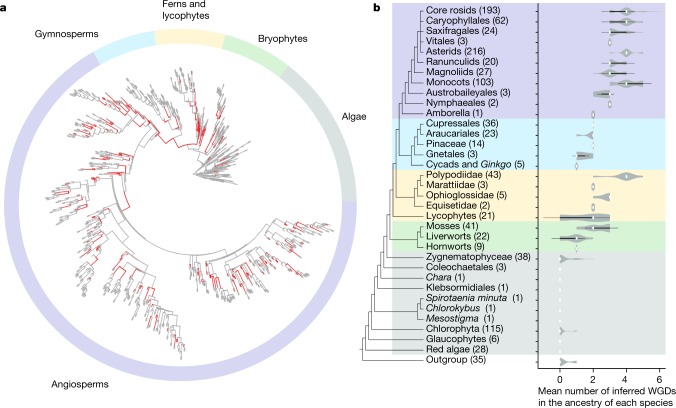

Inferred whole-genome duplications (WGDs; that is, polyploidy) across the gene-tree summary phylogeny estimated using ASTRAL15 were not uniformly distributed (Fig. 4, Supplementary Fig. 8 and Supplementary Table 2). Comparing distributions of gene duplication times for each species16 (Supplementary Table 3) and orthologue divergence times17 (Supplementary Table 4) with gene-tree analyses18 (Supplementary Tables 5, 6), we inferred 244 ancient WGDs across Viridiplantae (Supplementary Fig. 8 and Supplementary Table 2). Although there are limitations to the inference of WGD events using this approach, we found that comparisons of these results with 65 overlapping published genome-based WGD inferences revealed 6 false-negative results in our tree-based estimates and no false-positive results (Supplementary Table 2). Analyses based on whole-genome sequences are needed for further resolution of WGD events.

Fig. 4. The distribution of inferred ancient WGDs across lineages of green plants.

a, The locations of estimated WGDs are labelled red in the phylogeny of all 1000 Plants (1KP) samples. b, The number of inferred ancient polyploidization events within each lineage is shown in the violin plots. The white dot indicates the median, the thick black bars represent the interquartile range, the thin black lines define the 95% confidence interval and the grey shading represents the density of data points. The sample sizes for each lineage are shown within parentheses along with taxon names on the phylogeny. The phylogenetic placement of inferred WGDs is illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 8 and data supporting each WGD inference are provided in Supplementary Table 2.

With the exception of most Selaginella species and some liverworts (Fig. 1g), our analyses implicated at least one ancient WGD in the ancestry of every land plant lineage. By contrast, most algal lineages showed no evidence of WGD. Notably, the predicted sister clade of land plants (Fig. 2), Zygnematophyceae (Fig. 1e), exhibited the highest density of WGDs among algal lineages (Fig. 4), although the apparent increase in WGD was largely restricted to the desmid clade (Desmidiales) within Zygnematophyceae.

Increased diversification rates did not precisely co-occur with WGDs on the phylogeny. WGDs are expected to contribute to the evolution of novel gene function11,12. For example, novel functions among duplicate MADS-box genes that arose through WGD have been linked to the origin of flowering plants19,20 and core eudicots21, and functional diversification of gene families after WGD has contributed to the evolution of fruit colour in tomato species22,23 and to nodule development within legumes22,24. Consistent with previous studies with less extensive taxon sampling24–27, however, we inferred lags between WGDs and increased species diversity. Integrated phylogenomic and functional investigations are required to gain a mechanistic understanding of the lag between WGD, the evolution of novel gene functions and their potential influence on diversification rates.

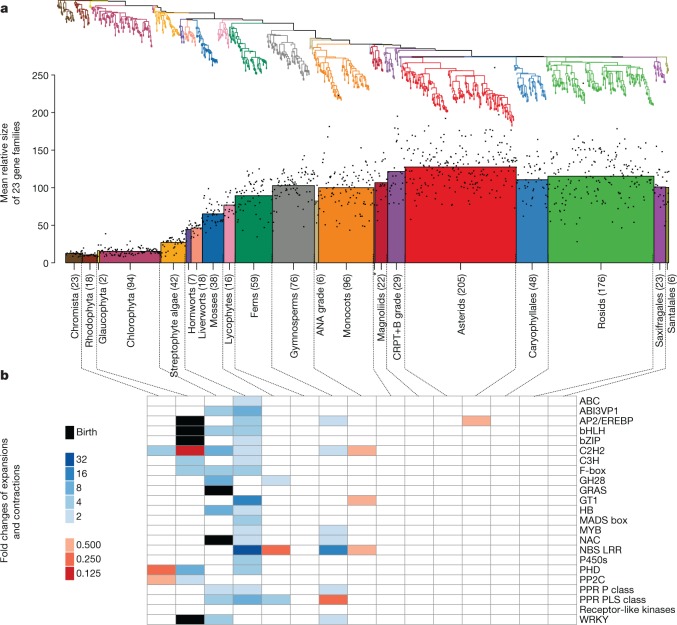

Gene-family expansions (and contractions) contribute to the dynamic evolution of metabolic, regulatory and signalling networks28,29. Given the inherent limitations of transcriptome data, we searched for large-fold changes in 23 of the largest gene families in Arabidopsis thaliana30 that are involved in many important functions (such as transcriptional regulation, enzymatic and signalling function, and transport; Fig. 5 and Supplementary Tables 7, 8). Although our RNA-sequencing-based sampling of expressed genes is incomplete, the median representation of universally conserved genes31 was 80–90% for taxa across Viridiplantae (Extended Data Fig. 3a, b). Furthermore, there was a strong correlation (r = 0.95) between gene-family sizes in our transcriptomes (focusing on the largest gene families) and those of fully sequenced genomes (Extended Data Fig. 3c–f). We identified gene-family expansions and contractions, including some that have been described previously32–34. Specifically, the AP2, bHLH, bZip and WRKY transcription factor families were inferred to be present in the last common ancestor of Viridiplantae, whereas the origin of GRAS and NAC genes occurred in early streptophytes after divergence from the chlorophyte algal lineage (Fig. 5). The highest concentration of expansion events was inferred along the ‘spine’ of the phylogeny between the origins of Viridiplantae and vascular plants (Fig. 5b and Supplementary Table 7). Expansions of some focal gene families also continued after the origin of embryophytes; however, no expansions occurred in association with the origin and radiation of angiosperms (Fig. 5). Gene-family expansions and functional diversification may have contributed to the adaptations required for life in terrestrial habitats, but the sizes of these focal gene families apparently stabilized in the face of continued gene duplication and loss throughout the evolution of vascular plants.

Fig. 5. Assessment of significant expansions and contractions of largest plant gene families.

a, Weighted average gene-family size for species groups (normalized to account for differences in gene-family sizes, weight = 1/(maximum observed gene-family size)). The ANA grade comprises Amborellales, Nymphaeales and Austrobaileyales, successive sister lineages to a clade with the remaining extant angiosperms; the ‘CRPT+B’ grade includes Ceratophyllales, Ranunculales, Proteales lineages and a Trochodendrales + Buxales clade in the ASTRAL tree (Fig. 2). Sample sizes are proportional to bar widths (from left to right, n = 23 (Chromista), 18 (Rhodophyta), 2 (Glaucophyta), 94 (Chlorophyta), 42 (streptophyte algae), 7 (hornworts), 18 (liverworts), 38 (mosses), 16 (lycophytes), 59 (ferns; monilophytes), 76(gymnosperms), 6 (ANA grade), 96 (monocots), 1 (*representing Chloranthales), 22 (magnoliids), 29 (CRPT+B grade), 205 (asterids), 48 (caryophyllids), 176 (rosids), 23 (Saxifragales) and 6 (Santalales). b, Gene families exhibiting significant copy number changes (two-sided Kolmogorov–Smirnov test; P < 1 × 10−6; gene-family expansions represent a gain of more than 50% and contractions represent a loss of more than 33%) with colour codes showing the magnitude of the observed fold changes. Data and analysis scripts are available at https://github.com/GrosseLab/OneKP-gene-family-evo.

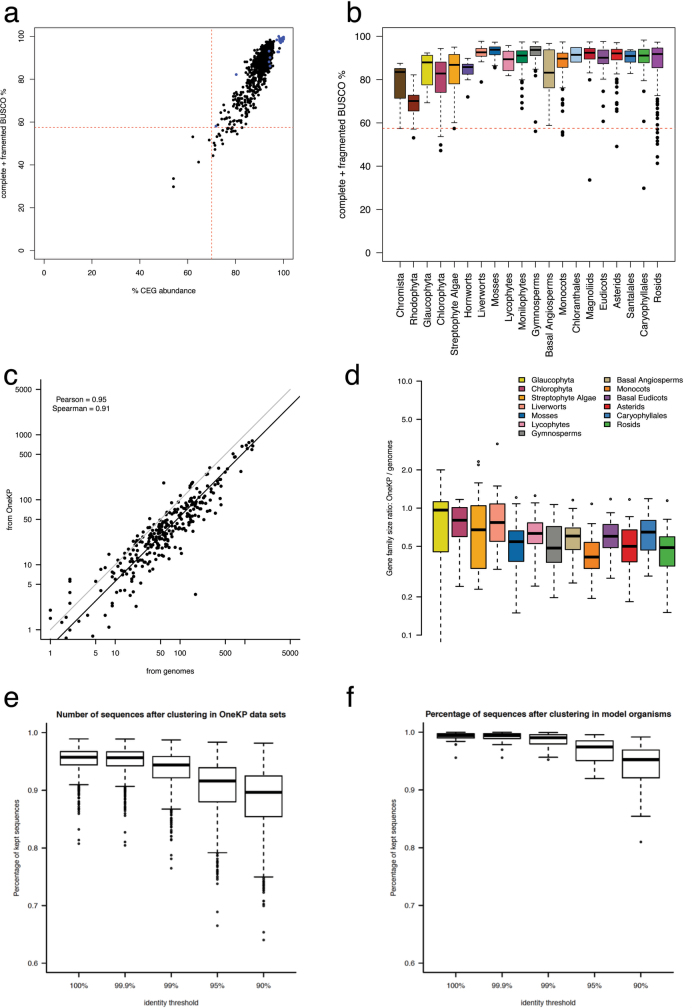

Extended Data Fig. 3. Assessments of transcriptome assembly gene-family representation relative to gene-family members identified in annotated genomes.

a, BUSCO versus CEGMA (CEG) gene occupancy for each sample. BUSCO transcriptome completeness is given as ‘complete plus fragmented’ BUSCO percentage using the eukaryota_odb9 database. CEGMA transcriptome completeness is given as conditional reciprocal best BLAST hits (see Supplementary Methods). Dotted line represents 57.5% (BUSCO) and 70% (CEGMA) gene occupancy threshold. Black dots represent 1KP samples (n = 1,020) and blue dots annotated plant genomes (n = 30). b, BUSCO gene occupancy for each major clade. Boxes represent lower and upper quartiles; the black bold line represents the median and whiskers extend to the most-extreme data points. Sample sizes: Chromista, n = 23; Rhodophyta, n = 18; Glaucophyta, n = 2; Chlorophyta, n = 94; streptophyte algae, n = 42; hornworts, n = 7; liverworts, n = 18; mosses, n = 38; lycophytes, n = 16; monilophytes, n = 59; gymnosperms, n = 76; ANA grade, n = 6; monocots, n = 96; Chloranthales, n = 1; magnoliids, n = 22; CRPT grade, n = 29; asterids, n = 205; Caryophyllales, n = 48; rosids, n = 176; Saxifragales, n = 23; Santalales, n = 6. Dotted line represents 57.5% (BUSCO) gene occupancy threshold. c, Scatterplot of gene-family sizes in transcriptomes versus genomes on a logarithmic scale. The grey line indicates x = y, the black line indicates a linear regression fitted to the data (n = 299; 23 gene families in 13 species groups). Pearson and Spearman correlation coefficients (n = 299) are indicated. d, Box plot of transcriptome:genome ratios of gene-family sizes for each species group. Boxes indicate upper and lower quartiles with median; whiskers extend to data points no more than 1.5× the interquartile range (n = 23) with outliers plotted as individual data points. e, f, Number of remaining sequences after filtering with cd-hit and a threshold of 100%, 99.9%, 99%, 95% or 90% in transcriptome sequences and reference genomes (Supplementary Table 8). Boxes indicate upper and lower quartiles with median; whiskers extend to data points no more than 1.5× the interquartile range (e, n = 1,451; f, n = 32) with outliers plotted as individual data points.

Primary acquisition of the plastid

The primary acquisition of the plastid in an ancestor of extant Archaeplastida was a pivotal event in the history of life. All possible relationships among Viridiplantae, Glaucophyta and Rhodophyta have been hypothesized, with alternative implications for the gain and loss of characters35 in the early history of the three lineages. Strong support for the sister relationship of Viridiplantae and Glaucophyta35 (Figs. 2, 3a) found here indicates that ancestral red algae lost flagella and peptidoglycan biosynthesis, perhaps associated with a reduction in genome size36. Peptidoglycan biosynthesis was independently lost early in the evolution of Chlorophyta37 and within angiosperms38.

The history of Viridiplantae

The origin of Viridiplantae is marked by the loss of light-harvesting phycobilisomes composed of phycobiliproteins, the evolution of the accessory photosynthetic pigment chlorophyll b, which has a distinct light-absorption spectrum relative to chlorophyll a, and intraplastidial starch synthesis and deposition. Viridiplantae are consistently recovered as monophyletic, with early diverging Chlorophyta and Streptophyta lineages39–41. However, the placement of the picoplanktonic algal lineage Prasinococcales was unstable in our analyses (Fig. 3e).

Diversification within Chlorophyta

All nuclear-gene analyses resolved a grade of largely marine unicellular lineages subtending the core clade consisting of Trebouxiophyceae, Ulvophyceae and Chlorophyceae42 (Fig. 1a–c and Supplementary Figs. 1–3). The nuclear supermatrix and ASTRAL trees placed Trebouxiophyceae as sister to a clade containing Chlorophyceae and Ulvophyceae42,43. However, whereas the supermatrix trees supported Ulvophyceae as monophyletic, the ASTRAL tree resolved Ulvophyceae as a grade and Bryopsidales is poorly supported as sister to Chlorophyceae (Fig. 3h). All tree estimates suggest that there were multiple origins of multicellularity within Ulvophyceae. Only 12 out of 119 sampled chlorophyte species exhibited evidence of a WGD in their ancestry, and most of these putative WGDs were restricted to single clades.

Streptophyta

The evolution of streptophytes was associated with several adaptations to terrestrial habitats44–46. All analyses recovered Mesostigma, Chlorokybus and Spirotaenia minuta in a clade that is sister to the remainder of Streptophyta39 with successive divergence of Klebsormidiales, Charophyceae (Fig. 1d), Coleochaetophyceae and Zygnematophyceae (Fig. 1e) relative to Embryophyta. However, with greatly increased taxon sampling relative to our previous work39, internal branch lengths are diminished, and we could not reject the possibility of a true radiation giving rise to Coleochaetales, Zygnematophyceae and embryophyte lineages (land plants; Figs. 1f–p, 3g(II)). Although quartet support for a clade of Coleochaetales and Zygnematophyceae as sister to embryophytes was similar to support for Zygnematophyceae as sister to embryophytes, a clade consisting of Coleochaetales and land plants was not supported.

Embryophyta

Land plants include many of the most familiar green plants (for example, bryophytes (Fig. 1f–h), lycophytes (Fig. 1i), ferns (Fig. 1j, k) and seed plants (Fig. 1l–p)). They exhibit key innovations, including protected reproductive organs (archegonia and antheridia) and the development of the zygote within an archegonium into an embryo that receives maternal nutrition. Resolving relationships among bryophytes (mosses, liverworts and hornworts) and their relationships to the remaining land plants has long been problematic, but is critical for understanding the evolution of fundamental innovations within land plants, including the tolerance to desiccation, shifts in the dominance of multicellular haploid and diploid generations, and parental retention of a multicellular embryo.

Bryophytes have sometimes been resolved as a grade47,48, with liverworts, mosses and hornworts as successive sister groups to Tracheophyta (vascular plants; Fig. 1i–p). We recovered extant bryophytes as monophyletic in the ASTRAL analysis of nuclear gene trees (Fig. 3b) and plastome analyses, with hornworts sister to a moss and liverwort clade. All analyses rejected the hypothesis that liverworts are sister to all other extant land plant lineages39,49.

The largest number of gene-family expansions in our analyses was associated with the origin of land plants and the evolution of bryophytes (transition between streptophyte algae and bryophytes in Fig. 5b). By contrast, we found no evidence of WGD on the stem branch for land plants (Supplementary Tables 5, 6).

Vascular plants

Within the vascular plants, lycophytes are supported as the sister group of Euphyllophyta (ferns and seed plants). We found no evidence of pan-vascular-plant or ancestral euphyllophyte WGDs, but some gene-family expansions were associated with the origin of vascular plants (Fig. 5b).

Within ferns (Polypodiopsida), plastid data weakly support Equisetales as sister to Psilotales and Ophioglossales (Supplementary Fig. 3), whereas nuclear gene analyses robustly place Equisetales sister to the remaining ferns50. The supermatrix and plastome-based trees placed Marattiales sister to the leptosporangiate ferns50 (Polypodiidae), but ASTRAL recovers nearly equal quartet support for this hypothesis or for Marattiales as sister to Psilotales and Ophioglossales (Fig. 3f). Leptosporangiate ferns (Fig. 1k) experienced more WGD events than any other lineage of Viridiplantae outside the angiosperms, with an average of 3.79 inferred WGDs in the history of each sampled species (Fig. 4). WGD was inferred in an ancestor of all extant ferns and an additional 19 putative WGDs were implicated in the ancestry of fern subclades (Ophioglossaceae and Polypodiaceae; Fig. 4, Supplementary Fig. 8 and Supplementary Tables 2, 5, 6). Considering the high chromosome numbers of some ferns, our discovery that they exhibit one of the highest frequencies of palaeopolyploidization among green plants is not unexpected51.

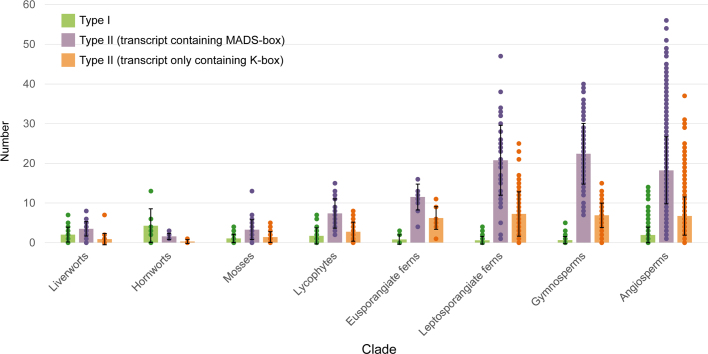

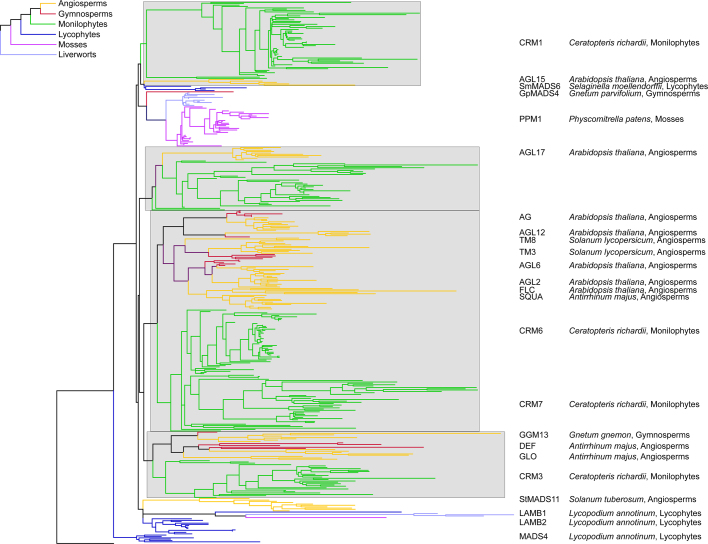

Whereas none of our focal gene families exhibited significant expansion in ferns, significantly more MIKC-type MADS-box genes—involved in specification of ovule and flower development in seed plants52—were observed in leptosporangiate ferns relative to all other green plant lineages, other than seed plants (Extended Data Fig. 1). The ancestral number of MIKC-type MADS-box genes for ferns and seed plants was 4 or 5, and gene numbers increased independently within leptosporangiate ferns and seed plants (Extended Data Figs. 1, 2).

Extended Data Fig. 1. Mean number of MADS-box genes in the transcriptomes of different plant clades.

Type I genes are shown in green; type II genes are shown in purple and orange. Transcripts in which only a K-box was identified (which are probably partial transcripts of type II genes) are shown in orange. Data are mean ± s.d. Dots indicate the numbers of MADS-box genes in individual transcriptomes. Sample sizes (n) are as follows: liverworts, n = 26; hornworts, n = 7; mosses, n = 37; lycophytes, n = 22; eusporangiate ferns, n = 10; leptosporangiate ferns, n = 62; gymnosperms, n = 84; and angiosperms, n = 820. A total of 1,068 transcriptomes were analysed for this figure.

Extended Data Fig. 2. RAxML phylogeny of classic type II MIKCc MADS-box genes of liverworts, mosses, lycophytes, monilophytes (ferns) and spermatophytes (seed plants).

CgMADS1 from Chara globularis was used as a representative of the outgroup. Branches leading to genes from the different phyla are coloured according to the simplified phylogeny of land plants that is shown in the top left corner. The phylogenetic position of some known type II MIKCc MADS-box genes111 representative of previously described clades of MADS-box genes are indicated on the right together with the species and phylum in which these genes have been identified. The four clades of MIKCc MADS-box genes that trace back to the most recent common ancestor of Euphyllophytes are shaded in grey.

Seed plants

A WGD in the ancestry of all extant seed plants has been inferred previously18,53 but remains contested54. Gene-tree18 analyses revealed significantly more gene duplications on the branch leading to extant seed plants than expected from background gene birth and death rates (analyses D1 (P < 2.0 × 10−18) and D2 (P < 8.9 × 10−16) in Supplementary Table 5). Numerous gene-family expansions were also associated with the origin of seed plants, and only one contraction was detected among the gene families analysed (Fig. 5b). Type II MIKC-type MADS-box genes exhibited a nearly twofold expansion independent of their expansion in ferns (Extended Data Figs. 1, 2).

Extant gymnosperms (approximately 1,000 species) are sister to flowering plants, and all of our analyses recovered Cycadales and Ginkgo (Fig. 1l) as a sister clade to the remaining gymnosperms (Fig. 3c). The placement of Gnetales conflicts strongly among the ASTRAL, supermatrix and plastome-based trees. Plastid data strongly support the ‘Gnecup’ hypothesis, with Gnetales as sister to a clade comprising Araucariales and Cupressales47, whereas the supermatrix analysis of nuclear genes supports a ‘Gnepine’ hypothesis with Gnetales as sister to Pinales55,56. ASTRAL analyses strongly support the ‘Gnetifer’ hypothesis, with conifers (Araucariales, Cupressales and Pinales) sister to Gnetales57. The short internal branches in the ASTRAL tree suggest rapid diversification (Fig. 2). However, the uneven frequencies of gene-tree quartets—which support the alternative Gnecup and Gnepine hypotheses—suggest that gene-tree estimation biases58 associated with increased substitution rates in Gnetales59 or gene flow are possible sources of gene-tree discordance8. Previously inferred WGDs in ancestors of Welwitschia, Pinaceae and Cupressales18 are supported, as is a new inference of WGD in the ancestry of Podocarpaceae (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Tables 2, 5, 6).

Angiosperms are by far the largest clade of green plants (more than 370,000 species2) and are marked by multiple key innovations, including the carpel, double fertilization, endosperm, and for most angiosperms, vessel elements. Both nuclear and plastid phylogenomic analyses agree with previous studies39 in providing strong support for angiosperm monophyly and in placements of Amborellales, Nymphaeales and Austrobaileyales as successive sisters to all other angiosperms (Figs. 2, 3). Chloranthales and magnoliids comprise a clade in the ASTRAL and supermatrix analyses, but were resolved with poor support as successive sister lineages to all other Mesangiospermae (monocots, Ceratophyllum and eudicots) in the plastome-based tree. Whereas Ceratophyllum is sister to eudicots in the ASTRAL and plastome trees, it is poorly supported as sister to monocots in the supermatrix tree (Supplementary Figs. 1–3). All analyses suggest short time intervals between branching of the monocots, Magnoliidae, Chloranthales, Ceratophyllales and eudicot lineages in early mesangiosperm history (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Figs. 1–3).

Pentapetalae (70% of all angiosperms) are marked by the evolution of the pentamerous flower. Substantial gene-tree discordance was observed for relationships among core rosids, Saxifragales, Vitales, Dillenia, Santalales, Berberidopsidales, Caryophyllales, asterids and Gunnerales (the sister group of Pentapetalae; Fig. 3i). Short internal branches and poor support in the ASTRAL tree at the base of the core eudicots (Figs. 2, 3i) indicate rapid diversification following two rounds of WGD that resulted in palaeohexaploidy preceding the origin of the clade60,61 (Supplementary Fig. 8). The supermatrix and plastid trees conflict with the poorly supported ASTRAL branching order (Fig. 3i). With the exception of the Berberidopsidales and core asterid clade, we were not able to reject the possibility of polytomies at the evaluated nodes in ASTRAL analyses (Fig. 3i).

Genomic and phylogenomic analyses have identified numerous WGDs throughout angiosperm history62,63. We found evidence that extant flowering plants descend from a polyploid common ancestor19,53. Gene-tree analyses detected a significantly larger-than-background number of gene duplications on the branch leading to the last common ancestor of extant angiosperms after divergence from the extant gymnosperm clade (analyses E1 (P < 1.8 × 10−41) and E2 (1.4 × 10−24) in Supplementary Table 5). Furthermore, the numbers of inferred duplications on the stem branch of angiosperms were consistent with expectations for WGD (analyses E1 and E2 in Supplementary Table 6). We inferred over 180 WGDs within flowering plants, including 132 in eudicots and 35 in monocots (Supplementary Table 2).

The origin of the angiosperms was preceded by three focal gene-family contractions and no expansions (Fig. 5b), consistent with the hypothesis that the innovations in angiosperms may have involved the functional co-option of genes that were duplicated earlier in the evolution of seed plants19. We find that orthologues of some floral homeotic MADS-box genes originated in the stem group of extant seed plants approximately 300 million years ago (Extended Data Fig. 2), supporting the hypothesis that the origin of the angiosperm flower involved recruitment of developmental regulators that already existed in their seed plant ancestors19,64.

Synthesis

These analyses establish a foundation for advancing our understanding of the overall phylogenetic framework of green plants and the genetic changes that were responsible for the characteristic traits associated with major evolutionary transitions in Viridiplantae. Portions of the species tree reported here remain unresolved. Phylogenetic analyses of genes extracted from a broad sampling of whole-genome sequences may improve gene family circumscriptions and resolve the species tree further. Expanded genome sequencing may also help to accurately account for interspecific gene flow, and orthology in the face of gene duplications and losses. However, for some nodes in the species tree, extensive discordance among inferred gene histories suggests that rapid diversification may not always conform to strict bifurcation of ancestral species into two descendent species.

Gene and genome duplications have long been considered a source of evolutionary novelty11,12, producing an expanded molecular repertoire for adaptive evolution of key pathways and shifts in plant development and ecology. However, the direct connections between key innovations and specific gene duplications are rarely known, due in part to lag times between duplications and such inovations25–27. Phylogenetically informed experimental investigations of changes in gene content and function will improve our understanding of the roles of gene and genome duplications in the evolution of key innovations. Such efforts are underway, drawing on an expanding number of experimental model species distributed across the green plant tree of life65.

Methods

Data reporting

No statistical methods were used to predetermine sample size. The experiments were not randomized, although simulations included in the genome duplication analyses did include drawing from random distributions. The investigators were not blinded to allocation during experiments and outcome assessment.

Transcriptome sequencing

RNA was isolated from young vegetative tissue from all of the species that were included in our phylogenomic analyses as described elsewhere39,67,68. Reproductive tissues were also included for some species (Supplementary Table 1). Transcript assembly, contaminant identification and gene-family circumscription were also performed as described previously39 and are described in more detail in the Supplementary Methods.

Phylogeny reconstruction

Analyses were performed on single-copy gene trees using ASTRAL to account for variation among gene trees owing to incomplete lineage sorting15,69. ASTRAL analyses were performed on gene trees estimated from unbinned amino acid alignments, first and second codons, statistically binned supergenes with unweighted bins70,71 and filtered taxon sets (excluding ‘rogue’ taxa as described below), with filtering of gene-tree bootstrap support thresholds of up to 33% to see whether the effects of gene-tree estimation error could be reduced (Supplementary Fig. 6). Binning left the majority of genes in singleton bins and had minimal effects on the overall species tree. Unless otherwise specified, we use ‘ASTRAL topology’ to refer to the tree inferred from 410 unbinned amino acid alignments in which branches with 33% or less support are contracted. In addition, supermatrix analyses were performed on concatenated nuclear gene alignments and concatenated plastid gene alignments compiled using previously described methods72. All scripts used to perform analyses on the nuclear gene data are available at 10.5281/zenodo.3255100.

Multiple sequence alignment and data filtering

We built a multiple sequence alignment based on predicted amino acid sequences of each gene and forced DNA sequences to conform to the amino acid alignment. We first divided sequences in each gene into two subsets, full-length and abnormal sequences, and then used PASTA73 with default settings to align full-length sequences and UPP74 to add abnormal sequences to the full-length alignment. We designated as abnormal any sequence that was 66% shorter or 66% longer than the median length of the full-length gene sequences. Once UPP alignments were obtained, we removed from them all unaligned (that is, insertion) sites. DNA alignments were then derived from amino acid sequence alignments (FAA2FNA) and third codon positions were removed owing to extreme among-species variation in GC content (Supplementary Fig. 7). To reduce running time, we then masked all sites from the alignment that contained more than 90% gaps. Finally, because the inclusion of fragmentary data in gene-tree estimation can be problematic75, we removed any sequence that had a gap for at least 67% of the sites in the site-filtered alignment (the 67% threshold was chosen based on simulation results75). Gene sequence occupancy for 410 single-copy genes in the 1,178 accessions used in our analyses is displayed as a frequency histogram (Supplementary Fig. 4) and a heat map (Supplementary Fig. 5).

In addition to filtering gappy sites and fragmentary sequences, we identified and removed sequences that were placed on extremely long branches on their respective gene trees. To identify these, we used the initial alignments to build gene trees (see below). We then rooted each gene tree by finding the bipartition that separated the largest exclusive group of outgroup or red algae taxa. If red algae were entirely missing for the gene, we used Glaucophyta, Prasinococcales, prasinophytes, Volvox carteri, Chlamydomonas reinhardtii or Klebsormidium nitens. We then removed any sequences that had a root-to-tip distance that was four standard deviations longer than the median root-to-tip distance in each gene tree. Once these sequences on long branches were removed, alignments were re-estimated using the same approach described above, and new gene trees were estimated.

Gene-tree estimation

To estimate gene trees, we used RAxML v.8.1.1776, with one starting tree for building initial trees (used for long-branch filtering) and 10 different starting trees for final gene trees. Support was assessed with 100 replicates of bootstrapping. For DNA analyses, the GTR substitution model and the GAMMA-distributed site rates were used. For amino acid sequences, we used a Perl script adapted from the RAxML website to search among 16 different substitution models on a fixed starting tree per gene and chose the model with the highest likelihood (JTT, JTTF or JTTDCMUT were selected for 349 out of 410 genes). For amino acid trees, we also used the GAMMA-distributed site rates.

Species tree estimation

We used ASTRAL-II15 v.5.0.3 to estimate the species tree on the basis of all 410 genes; using 384 genes that each included at least half of the species changed only 3 low-support branches. We used multi-locus bootstrapping77,78 and the built-in local posterior probabilities of ASTRAL to estimate branch support69 and to test for polytomies79, drawn on species trees estimated based on the maximum-likelihood gene trees. We also used the built-in functionality of ASTRAL (version 4.11.2) to compute the percentage of gene trees that agreed with each branch in the species tree, by finding the average number of gene-tree quartets defined around the branch (choosing one taxon from each side) that were congruent with the species tree and used DiscoVista80 to visualize them (Fig. 4). Median representation of each species across the 410 single-copy gene trees was 82.4% with 88.2% and 67.1% of species having assemblies for at least 50% or 75% of the 410 single-copy genes, respectively. A large body of work on phylogenetic methodologies has established that gene and species tree estimation can be robust to missing data, particularly with dense taxon sampling75,81,82. Recent papers have even established statistical consistency under missing data83. Similar evidence of robustness also exists in the context of concatenated analyses84–86.

All supermatrix analyses are based on the filtered amino acid and first and second codon position alignments that included at least half of the species for 384 genes. The (1) unfiltered supermatrices used the gene alignments as is; the (2) eudicot supermatrices retained only eudicot species in the supermatrix; and the (3) supermatrices with eight ‘rogue’ taxa removed (Dillenia indica, Tetrastigma obtectum, Tetrastigma voinierianum, Vitis vinifera, Cissus quadrangularis, ‘Spirotaenia’ sp., Ceratophyllum demersum and Prasinococcus capsulatus) that varied in placement among our full ASTRAL, supermatrix and plastid genome analyses. Well-supported branching orders were stable among analyses (Supplementary Fig. 6).

Maximum-likelihood supermatrix analyses were performed using ExaML v.3.0.1487. Similar to the gene-tree analyses, the GAMMA model of rate heterogeneity across sites was used for all maximum-likelihood supermatrix analyses. To better handle model heterogeneity across genes, we divided the supermatrix into partitions. For the amino acid alignments, the protein model selected for each gene family in the gene-tree estimation process was used to group genes into partitions, creating one partition per substitution model. For the nucleotide alignments, we estimated the GTR transition rate parameters and the alpha shape parameter for each codon position (first and second positions) of each alignment using RAxML v.8.1.2176. We then projected the maximum-likelihood parameter values for each gene into a two-dimensional plane using principal component analysis88. We performed k-means clustering89 in R90 to group the codon positions into partitions, selecting k = 8, which accounted for 80% of the variation. Trees derived from nucleotide alignments can be found at 10.5281/zenodo.3255100).

To examine the influence of the starting tree on the likelihood of the final tree, we performed preliminary analyses on an earlier version of our supermatrices. We generated nine different maximum-parsimony starting trees using RAxML v.8.1.21 and one maximum-likelihood starting tree using FastTree-2 v.2.1.591. We then ran ExaML on each of the starting trees, noting the final maximum-likelihood score. We found that in all cases, the ExaML maximum-likelihood tree using the FastTree-2 maximum-likelihood starting tree had a better maximum-likelihood score than any of the ExaML maximum-likelihood trees using maximum-parsimony starting trees. Thus, for all of the supermatrix analyses, we used FastTree-2 to generate our initial starting tree. Support was inferred for the branches of the final tree from 100 bootstrap replicates.

Outgroup taxa from outside Archaeplastida were used to root all species trees estimated using nuclear genes (all ASTRAL and supermatrix analyses). The plastome supermatrix tree for Viridiplantae was rooted using Rhodophyta as outgroup.

Inferring and placing WGDs

DupPipe analyses of WGDs from transcriptomes of single species

For each transcriptome, we used the DupPipe pipeline to construct gene families and estimate the age distribution of gene duplications16,17. We translated DNA sequences and identified reading frames by comparing the Genewise92 alignment to the best-hit protein from a collection of proteins from 25 plant genomes from Phytozome93. For all DupPipe runs, we used protein-guided DNA alignments to align our nucleic acid sequences while maintaining the reading frame. We estimated synonymous divergence (Ks) using PAML with the F3X4 model94 for each node in the gene-family phylogenies. We identified peaks of gene duplication as evidence of ancient WGDs in histograms of the age distribution of gene duplications (Ks plots). We identified species with potential WGDs by comparing their paralogue age distribution to a simulated null using a Kolmogorov–Smirnov goodness of fit test95. We then used mixture modelling and manual curation to identify significant peaks consistent with a potential WGD and to estimate their median paralogue Ks values. Significant peaks were identified using a likelihood ratio test in the boot.comp function of the package mixtools in R96.

Estimating orthologous divergence

To place putative WGDs in relation to lineage divergence, we estimated the synonymous divergence of orthologues among pairs of species that may share a WGD based on their phylogenetic position and evidence from the within-species Ks plots. We used the RBH Orthologue pipeline17 to estimate the mean and median synonymous divergence of orthologues and compared those to the synonymous divergence of inferred paleopolyploid peaks. We identified orthologues as reciprocal best blast hits in pairs of transcriptomes. Using protein-guided DNA alignments, we estimated the pairwise synonymous divergence for each pair of orthologues using PAML with the F3X4 model94. WGDs were interpreted to have occurred after lineage divergence if the median synonymous divergence of WGD paralogues was younger than the median synonymous divergence of orthologues. Similarly, if the synonymous divergence of WGD paralogues was older than that orthologue synonymous divergence, then we interpreted those WGDs as shared.

MAPS analyses of WGDs from transcriptomes of multiple species

To infer and locate putative WGDs in our datasets, we used a gene-tree sorting and counting algorithm, the multi-taxon paleopolyploidy search (MAPS) tool18. For each MAPS analysis, we selected at least two species that potentially share a WGD in their ancestry as well as representative species from lineages that may phylogenetically bracket the WGD. MAPS uses this given species tree to filter collections of nuclear gene trees for subtrees consistent with relationships at each node in the species tree. Using this filtered set of subtrees, MAPS identifies and records nodes with a gene duplication shared by descendant taxa. To infer and locate a potential WGD, we compared the number of duplications observed at each node to a null simulation of background gene birth and death rates97,98. A Fisher’s exact test, implemented in R90, was used to identify locations with significant increases in gene duplication compared with a null simulation (Supplementary Table 5). Locations with significantly more duplications than expected were then compared to a simulated WGD at this location. If the observed duplications were consistent with this simulated WGD using Fisher’s exact test, we identified the location as a WGD if it was consistent with inferences from Ks plots and orthologue divergence data. In some cases, MAPS inferred significant duplications without apparent signatures in Ks plots or previously published research. In these cases, we recognized the event as a significant burst of gene duplication.

Each MAPS analysis was designed to place focal WGDs near the centre of a species tree to minimize errors in WGD inference. Errors in transcriptome or genome assembly, gene-family clustering and the construction of gene-family phylogenies can result in topological errors in gene trees99. Previous studies have suggested that errors in gene trees can lead to biased placements of duplicates towards the root of the tree and losses towards the tips of the tree100. For this reason, we aimed to put focal nodes for a particular MAPS analysis test in the middle of the phylogeny. To further decrease potential error in our inferences of gene duplications, we required at least 45% of the ingroup taxa to be present in all subtrees analysed by MAPS97. If this minimum requirement of ingroup taxa numbers is not met, the gene subtree will be filtered out and excluded from our analysis. Increasing taxon occupancy leads to a more accurate inference of duplications and reduces some of the biases in mapping duplications onto a species tree100,101. To maintain sufficient gene-tree numbers for each MAPS analysis, we used collections of gene-family phylogenies for six to eight taxa to infer ancient WGDs.

For each MAPS analysis, the transcriptomes were translated into amino acid sequences using the TransPipe pipeline17. Using these translations, we performed reciprocal protein BLAST (BLASTp) searches among datasets for the MAPS analysis using a cut-off of E = 1 × 10−5. We clustered gene families from these BLAST results using OrthoFinder under the default parameters102. Using a custom Perl script (https://bitbucket.org/barkerlab/maps), we filtered for gene families that contained at least one gene copy from each taxon in a given MAPS analysis and discarded the remaining OrthoFinder clusters. We used PASTA73 for automatic alignment and phylogeny reconstruction of gene families. For each gene-family phylogeny, we ran PASTA until we reached three iterations without an improvement in likelihood score using a centroid breaking strategy. Within each iteration of PASTA, we constructed subset alignments using MAFFT103, used Muscle104 for merging these subset alignments and RAxML76 for tree estimation. The parameters for each software package were the default options for PASTA (https://bitbucket.org/barkerlab/1kp). We used the best-scoring PASTA tree for each multi-species nuclear gene family to collectively estimate the numbers of shared gene duplications on each branch of the given species.

To generate null simulations, we first estimated the mean background gene duplication rate (λ) and gene loss rate (μ) with WGDgc98 (Supplementary Tables 5, 11). Gene count data were obtained from OrthoFinder102 clusters associated with each species tree (Supplementary Table 5). λ and μ were estimated using only gene clusters that spanned the root of their respective species trees, which has been shown to reduce biases in the maximum-likelihood estimates98 of λ and μ. We chose a maximum gene-family size of 100 for parameter estimation, which was necessary to provide an upper bound for numerical integration of node states98. We provided a prior probability distribution on the number of genes at the root of each species tree, such that ancestral gene-family sizes followed a shifted geometric distribution with mean equal to the average number of genes per gene family across species (Supplementary Table 5).

Gene trees were then simulated within each MAPS species trees using the GuestTreeGen program from GenPhyloData105. For each species tree, we simulated 3,000 gene trees with at least one tip per species: 1,000 gene trees at the λ and μ maximum-likelihood estimates, 1,000 gene trees at half the estimated λ and μ, and 1,000 trees at three times λ and μ. For all simulations, we applied the same empirical prior used for estimation of λ and μ. We then randomly resampled 1,000 trees without replacement from the total pool of gene trees 100 times to provide a measure of uncertainty on the percentage of subtrees at each node. For positive simulations of WGDs, we simulated gene trees using the same approach used to generate null distributions (Supplementary Table 5) but incorporated a WGD at the test branch. Previous empirical estimates of paralogues retained following a plant WGD are 10% on average106. To be conservative for inferring WGDs in our MAPS analyses, we allowed at least 20% of the genes to be retained following the simulated WGD to account for biased gene retention and loss. For WGDs that might have a lower gene retention rate, we used an additional simulation using 15% gene retention (Supplementary Table 6).

Gene-family evolution

Transcriptome-based gene-family size estimation

To robustly estimate gene-family sizes from transcriptomic data, we needed to overcome three major challenges: (1) the fragmentation of transcript sequences; (2) the absence of low-abundance transcripts; and (3) the over-prediction of gene-family sizes due to assembly duplications and biological isoforms. We dealt with these challenges as follows.

Fragmentation of data

The multiple sequence alignments used to construct the domain-specific profile hidden Markov models (HMMs) ranged from 23 to 463 amino acids in length; 78% of these alignments were shorter than 120 amino acids, and 84.6% of the assembled and translated transcripts were longer than 120 amino acids. By mainly characterizing gene families using single domains (Supplementary Table 9), we limited the effect of the fragmentation of transcripts from the assembly of short read data. HMMs used for gene-family classification and decision rules obtained from either published work107 or gene-family experts are given in Supplementary Table 9; 12 out of 23 gene families were classified by a single ‘should’ rule, 2 out of 23 were defined by a XOR ‘should’ rule, which also classifies a sequence by the presence of a single domain, 8 out of 23 gene families were classified by a more complex rule set including ‘should not’ rules. The only gene family for which multiple domains needed to be present was the PLS subfamily of the PPR gene family.

Loss of low abundance transcripts

To account for possible bias in the sampling of the gene space, all species that showed low levels of transcriptome completeness were removed. The lowest value of transcriptome completeness obtained from 30 annotated plant genomes was used as the lower exclusion limit. We removed all samples in which more than 42.5% of BUSCO31 sequences were missing using default settings and the eukaryotic dataset as the query database.

Gene-family over-prediction

We clustered assembled protein sequences by sequence similarity and merged sequences that showed at least 99% identity. To check for the possibility of merging sequences that should be counted separately, different identity cut-offs were compared between the 1KP datasets and 32 annotated plant genomes.

Extended Data Figure 3c, d shows the average gene-family sizes for 23 gene families and 13 clades obtained from 1KP samples and 32 annotated plant genomes. These gene-family sizes show a high Pearson correlation (r = 0.95) between 1KP samples and plant genomes, and therefore a linear relationship between the two approaches is indicated. The results from the 1KP dataset are on average smaller by a factor of 2.3. Although this is a clear underestimate, the scale factor by which the estimate is too small is relatively consistent, especially as the gene-family sizes increase.

Sequence clustering

We used cdhit v.4.5.7108,109 to reduce the number of protein sequence duplications in the dataset. We assessed 100%, 99.5%, 99%, 95% and 90% sequence identity thresholds. The percentage of remaining sequences for the 1KP samples and 32 reference genomes is displayed in Extended Data Fig. 3f. We chose 99% sequence identity as the value to use for this study.

Estimation of gene-family size

Gene-family experts provided the knowledge to classify protein sequences as members of gene families with profile HMMs. In total, 46 HMMs representing 23 large gene families30 were used to estimate gene-family sizes in the analysed species. Classification rules and HMMs for 14 gene families that have been published previously107 were converted to HMMER3 format and used in this study. Gene-family classification rules and HMMs for the remaining nine families can be found in Supplementary Table 8. HMMs were taken from the Pfam database (accessed 12 May 2016) or were provided by gene-family experts (Supplementary Table 8). HMMER110 (v.3.1b2) was used to scan for matches in the filtered 1KP dataset. Where available, gathering thresholds were used; otherwise an E-value cut-off was applied to indicate domain presence. If the E value is not noted in Supplementary Table 9, the default E value of 10 was applied. The results on the species level are listed in Supplementary Table 10s.

Statistical test for expansions and contractions

To assess whether a gene family expanded or contracted in a lineage, we compared a weighted average of gene numbers in adjacent clades and grades (Fig. 4). We also checked for expansions and contractions within clades but did not find any statistically significant shifts. The counts of gene-family members from two clades or grades were compared with a Kolmogorov–Smirnov test with a P-value threshold of 1 × 10−6 in R90. The tests conducted in this study are listed in Supplementary Table 7. Fold changes were computed using the trimmed arithmetic mean in which the top and bottom 5% of the data were discarded. Only expansions larger than 1.5 fold (or contractions smaller than 2/3) are reported.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this paper.

Online content

Any methods, additional references, Nature Research reporting summaries, source data, extended data, supplementary information, acknowledgements, peer review information; details of author contributions and competing interests; and statements of data and code availability are available at 10.1038/s41586-019-1693-2

Supplementary information

This file contains the Supplementary Methods which include detailed descriptions of methods for transcriptome data generation and assessment, phylogenetic analyses, inference of whole genome duplications (WGDs) and gene family expansions. Supplementary Results are also included with additional details for results of phylogenetic and WGD analyses. Supplementary Figures 1-8 are included at the end of the file.

Supplementary Table 1 Sample list including 1KP indices, species names and lineage taxonomy, RNA seq data volumes, assembly assessments (BUSCO and TransRate scores) and SRA submission indices.

Supplementary Table 2 Summary of 244 inferred ancient WGDs from the 1KP analyses. WGD ID codes are organized in alphabetical order. The phylogenetic placement of each inferred ancient WGD is provided in Extended Data Fig. 4. An * indicates presence and absence of WGDs from cited syntenic analyses of whole genome data.

Supplementary Table 3 Summary of Ks distributions of duplicate gene pairs for each species. Species name and median Ks for each histogram of the age distribution of gene duplications (Ks plots available at https://bitbucket.org/barkerlab/1kp), and p-values of the two-sided K-S goodness of fit test is provided for each taxon. The median Ks value, the number of WGD peak inferred from Ks plots range from Ks 0 to 2 and 0 to 5 using mixture models from mixtools R package are reported. The sample size used to estimate the median Ks value, n=number of gene duplications, was calculated from the total number of gene duplications for each species multiplied by the percent contribution of a particular peak by mixtools. The number of inferred WGD in the ancestry of each species is also reported.

Supplementary Table 4 Summary of the synonymous ortholog divergence analyses. The mean, median, and standard deviation of synonymous ortholog divergence (Ks) for each inferred ancient WGD is reported. These statistics are based on the number of ortholog pairs identified for each species pair comparison. The sampling information with taxon code and WGD code is also reported.

Supplementary Table 5 Summary statistics and null simulations (no WGDs) for 72 Multi-tAxon Paleopolyploidy Search (MAPS) analyses. For each node of 72 MAPS analyses percentage of subtrees with shared inferred gene duplications and numbers of gene duplications in simulations without WGDs are reported along with the p-value for a one-sided Fisher’s exact test used to detect nodes with a significantly higher proportion of inferred gene duplications compared to the null distribution. An * indicates a significant node. Results are organized in tabs for each major green plant taxon.

Supplementary Table 6 Summary statistics and power simulations with WGDs for 72 MAPS analyses. As with Supplementary Table 5, for each lineage in each MAPS tree percentages of subtrees with shared inferred gene duplications is reported along with expectations bases on simulations with 20% (or 15% for six selected analyses) paralog retention following WGDs. Tables contains the p-value for a one-sided Fisher’s exact test used to detect nodes with a significantly lower proportion of mapping subtrees compared to our simulation. Results are organized in tabs for each major green plant taxon.

Supplementary Table 7 Gene family expansion counts for each taxon and gene family shown in Fig. 5.

Supplementary Table 8 Reference genomes used in phylogenetic analyses, Orthofinder gene family circumscription, and gene family size analyses.

Supplementary Table 9 Description of gene family HMMs and gene family experts.

Supplementary Table 10 Gene family HMM search statistics for each of the samples listed in Supplementary Table 1.

Supplementary Table 11 Rates of gene duplication (λ) and gene loss (μ) used in null and positive simulations (Supplementary Tables 5-6). Rates of gene duplication (λ) and gene loss (μ) were estimated using gene counts from OrthoFinder clusters associated with each MAPS analysis. Values correspond to global Maximum Likelihood Estimates (MLEs) and mean rates for simulations. The prior mean is the mean of the geometric probability distribution applied to the root of each species tree for optimizing MLEs of λ and μ as well as simulating gene trees with and without WGDs.

Acknowledgements

The 1KP initiative was funded by the Alberta Ministry of Advanced Education and Alberta Innovates AITF/iCORE Strategic Chair (RES0010334) to G.K.-S.W., Musea Ventures, The National Key Research and Development Program of China (2016YFE0122000), The Ministry of Science and Technology of the People’s Republic of China (2015BAD04B01/2015BAD04B03), the State Key Laboratory of Agricultural Genomics (2011DQ782025) and the Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of core collection of crop genetic resources research and application (2011A091000047). Sequencing activities at BGI were also supported by the Shenzhen Municipal Government of China (CXZZ20140421112021913/JCYJ20150529150409546/JCYJ20150529150505656). Computation support was provided by the China National GeneBank (CNGB), the Texas Advanced Computing Center (TACC), WestGrid and Compute Canada; considerable support, including personnel, computational resources and data hosting, was also provided by the iPlant Collaborative (CyVerse) funded by the National Science Foundation (DBI-1265383), National Science Foundation grants IOS 0922742 (to C.W.d., P.S.S., D.E.S. and J.H.L.-M.), IOS-1339156 (to M.S.B.), DEB 0830009 (to J.H.L.-M., C.W.d., S.W.G. and D.W.S.), EF-0629817 (to S.W.G. and D.W.S.), EF-1550838 (to M.S.B.), DEB 0733029 (to T.W. and J.H.L.-M.), and DBI 1062335 and 1461364 (to T.W.), a National Institutes of Health Grant 1R01DA025197 (to T.M.K., C.W.d. and J.H.L.-M.), Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft grants Qu 141/5-1, Qu 141/6-1, GR 3526/7-1, GR 3526/8-1 (to M.Q. and I.G.) and a Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada Discovery grant (to S.W.G.). We thank all national, state, provincial and regional resource management authorities, including those of province Nord and province Sud of New Caledonia, for permitting collections of material for this research.

Reviewer information

Nature thanks Paul Kenrick, Magnus Nordborg, Patrick Wincker and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Extended data figures and tables

A list of participants and their affiliations appears in the online version of the paper.

Author contributions

Framing of research and writing was carried out by J.H.L.-M., M.S.B., E.J.C., M.K.D., M.A.G., S.W.G., I.G., Z.L., M. Melkonian, S.M., M.P., M.Q., S.A.R., D.E.S., P.S.S., D.W.S., K.K.U., N.J.W. and G.K.-S.W. Samples were collected and RNA was prepared by L.D., P.P.E., I.E.J.-T., S.J., T.L., B.M., N.W.M., L.P., C.Q., P.T., J.C.V., M.M.A., M.S.B., M.D.B., R.S.B., D.J.B., R.M.B., E.B., S.F.B., D.O.B., J.N.B., K.P.B., V.B.-S., A.L.C., S.B.C., Z.Ç., Y.C., C. Chater, J.M.C., T.C., N.D.C., H. Clayton, S. Covshoff, B.J.C.-S., H. Cross, C.W.d., J.P.D., R.D., R.C.D., V.S.D.S., S.E., E.F., N.F., K.J.F., D.A.F., P.M.F., S.K.F., B.F., N.G., G.G., M.A.G., G.T.G., F.Q.Y.G., S. Greiner, A.H., J. M. Heaney, K.E.H., K.H., J. M. Hibberd, R.G.J.H., P.M.H., M.T.J.J., R.J., B.J., M.V.K., E.K., E.A.K., M.A.K., M.V.K., K.K., T.M.K., V.L., A.L., A.R.L., R. Lentz, F.-W.L., A.J.L., M.L., P.S.M., E.M., M.K.M., M. McKain, T.M., J.R.M., R.E.M., M.N.N., Y.P., P.R., D.R., C.W.R., M.R., R.F.S., A.K.S., M.S., E.E.S., E.-M.S., H.S., S.S., E.B.S., A.J.S., S.W.S., E.M.S., C.S., A.G.S., A.S., C.N.S., J.R.S., P.S., J.A.T., H.T., D.T., M.V., C.-N.W., S.G.W., M.W., S. Weststrand, J.H.W., D.F.W., N.J.W., S. Wu, A.S.W., Y.Y., D.Z., C.Z., J.Z., M.W.C., M.K.D., S.W.G., J.H.L.-M., M. Melkonian, J.C.P., C.J.R., D.E.S., P.S.S., D.W.S. and J.Y. (jointly led by M.W.C., M.K.D., S.W.G., J.H.L.-M., M. Melkonian, J.C.P., C.J.R., D.E.S., P.S.S., D.W.S. and J.Y.; major contributions by L.D., P.P.E., I.E.J.-T., S.J., T.L., B.M., N.W.M., L.P., C.Q., P.T. and J.C.V.). RNA sequencing and transcriptome assembly were carried out by E.J.C., C. Chen, L.C., S. Cheng, J.L., R. Li, X.L., H.L., Y.O., X.S., X.T., J.T., Z.T., F.W., J.W., X.W., G.K.-S.W., X.X., Z.Y., F.Y., X.Z., F.Z., Y. Zhu and Y. Zhang. (led by Y. Zhang; major contributions by E.J.C.). Samples were validated and contaminants were filtered by J.Y., S.A., M.S.B., T.J.B., E.J.C., S.W.G., J.H.L.-M., T.L., S.M., N.-p.N., X.S., K.K.U. and S. Wu. (led by S. Wu.; major contributions by J.Y.). Gene-family circumscription and phylogenetic analyses were carried out by S.M., N.-p.N., M.A.G., S.A., J.P.D., N.M., D.R.N., E.S., D.E.S., P.S.S., D.W.S., E.K.W., R.L.W., N.J.W., C.W.d., S.W.G., J.H.L.-M. and T.W. (jointly led by S.M., C.W.d., S.W.G., J.H.L.-M. and T.W.; major contributions by: S.M.). Genome duplication analyses were carried out by Z.L., H.A., N.A., A.E.B., S. Galuska, S.A.J., T.I.K., H.K., P.L.-I., H.E.M., X.Q., C.R.R., E.B.S., B.L.S., G.P.T., S.R.W., R.Y., S.Z. and M.S.B. (led by M.S.B.; major contributions by Z.L.). Gene-family expansion analyses were carried out by M.P., K.K.U., L.G., M. Melkonian, D.R.N., G.T., G.K.-S.W., I.G., S.A.R. and M.Q. (jointly led by I.G., S.A.R. and M.Q.; major contributions by M.P. and K.K.U.).

Data availability

All raw sequence reads have been posted in the NCBI SRA database under BioProject accession PRJEB4922. SRA entries for each assembly are listed in Supplementary Table 1. All sequence, gene tree and species tree data can be accessed through CyVerse Data Commons at 10.25739/8m7t-4e85. In addition, gene-family nucleotide and amino acid FASTA files can also be found at http://jlmwiki.plantbio.uga.edu/onekp/v2/; multiple sequence alignments, gene trees and species trees for single-copy nuclear genes included in phylogenomic analyses are also at 10.5281/zenodo.3255100; Ks plots, alignments and trees used for WGD analyses can be found at https://bitbucket.org/barkerlab/1kp; and data used for gene-family expansion analyses can be found at https://github.com/GrosseLab/OneKP-gene-family-evo.

Code availability

Scripts used for phylogenomic species tree analyses are available at 10.5281/zenodo.3255100. Scripts used for MAPS analyses of WGDs are available at https://bitbucket.org/barkerlab/maps and scripts used for gene-family expansion analyses are available at https://github.com/GrosseLab/OneKP-gene-family-evo. All script files are also accessible through CyVerse Data Commons at 10.25739/8m7t-4e85.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Eric J. Carpenter, Matthew A. Gitzendanner, Zheng Li, Siavash Mirarab, Martin Porsch, Kristian K. Ullrich, Lisa DeGironimo, Patrick P. Edger, Ingrid E. Jordon-Thaden, Steve Joya, Tao Liu, Barbara Melkonian, Nicholas W. Miles, Lisa Pokorny Montero, Charlotte Quigley, Philip Thomas, Juan Carlos Villarreal

These authors jointly supervised this work: James H. Leebens-Mack, Michael S. Barker, Michael K. Deyholos, Sean W. Graham, Ivo Grosse, Michael Melkonian, Siavash Mirarab, Marcel Quint, Stefan A. Rensing, Douglas E. Soltis, Pamela S. Soltis, Dennis W. Stevenson, Claude W. dePamphilis, Mark W. Chase, J. Chris Pires, Carl J. Rothfels, Jun Yu, Yong Zhang, Tandy Warnow, Shuangxiu Wu, Gane Ka-Shu Wong

Contributor Information

One Thousand Plant Transcriptomes Initiative:

James H. Leebens-Mack, Michael S. Barker, Eric J. Carpenter, Michael K. Deyholos, Matthew A. Gitzendanner, Sean W. Graham, Ivo Grosse, Zheng Li, Michael Melkonian, Siavash Mirarab, Martin Porsch, Marcel Quint, Stefan A. Rensing, Douglas E. Soltis, Pamela S. Soltis, Dennis W. Stevenson, Kristian K. Ullrich, Norman J. Wickett, Lisa DeGironimo, Patrick P. Edger, Ingrid E. Jordon-Thaden, Steve Joya, Tao Liu, Barbara Melkonian, Nicholas W. Miles, Lisa Pokorny, Charlotte Quigley, Philip Thomas, Juan Carlos Villarreal, Megan M. Augustin, Matthew D. Barrett, Regina S. Baucom, David J. Beerling, Ruben Maximilian Benstein, Ed Biffin, Samuel F. Brockington, Dylan O. Burge, Jason N. Burris, Kellie P. Burris, Valérie Burtet-Sarramegna, Ana L. Caicedo, Steven B. Cannon, Zehra Çebi, Ying Chang, Caspar Chater, John M. Cheeseman, Tao Chen, Neil D. Clarke, Harmony Clayton, Sarah Covshoff, Barbara J. Crandall-Stotler, Hugh Cross, Claude W. dePamphilis, Joshua P. Der, Ron Determann, Rowan C. Dickson, Verónica S. Di Stilio, Shona Ellis, Eva Fast, Nicole Feja, Katie J. Field, Dmitry A. Filatov, Patrick M. Finnegan, Sandra K. Floyd, Bruno Fogliani, Nicolás García, Gildas Gâteblé, Grant T. Godden, Falicia (Qi Yun) Goh, Stephan Greiner, Alex Harkess, James Mike Heaney, Katherine E. Helliwell, Karolina Heyduk, Julian M. Hibberd, Richard G. J. Hodel, Peter M. Hollingsworth, Marc T. J. Johnson, Ricarda Jost, Blake Joyce, Maxim V. Kapralov, Elena Kazamia, Elizabeth A. Kellogg, Marcus A. Koch, Matt Von Konrat, Kálmán Könyves, Toni M. Kutchan, Vivienne Lam, Anders Larsson, Andrew R. Leitch, Roswitha Lentz, Fay-Wei Li, Andrew J. Lowe, Martha Ludwig, Paul S. Manos, Evgeny Mavrodiev, Melissa K. McCormick, Michael McKain, Tracy McLellan, Joel R. McNeal, Richard E. Miller, Matthew N. Nelson, Yanhui Peng, Paula Ralph, Daniel Real, Chance W. Riggins, Markus Ruhsam, Rowan F. Sage, Ann K. Sakai, Moira Scascitella, Edward E. Schilling, Eva-Marie Schlösser, Heike Sederoff, Stein Servick, Emily B. Sessa, A. Jonathan Shaw, Shane W. Shaw, Erin M. Sigel, Cynthia Skema, Alison G. Smith, Ann Smithson, C. Neal Stewart, Jr, John R. Stinchcombe, Peter Szövényi, Jennifer A. Tate, Helga Tiebel, Dorset Trapnell, Matthieu Villegente, Chun-Neng Wang, Stephen G. Weller, Michael Wenzel, Stina Weststrand, James H. Westwood, Dennis F. Whigham, Shuangxiu Wu, Adrien S. Wulff, Yu Yang, Dan Zhu, Cuili Zhuang, Jennifer Zuidof, Mark W. Chase, J. Chris Pires, Carl J. Rothfels, Jun Yu, Cui Chen, Li Chen, Shifeng Cheng, Juanjuan Li, Ran Li, Xia Li, Haorong Lu, Yanxiang Ou, Xiao Sun, Xuemei Tan, Jingbo Tang, Zhijian Tian, Feng Wang, Jun Wang, Xiaofeng Wei, Xun Xu, Zhixiang Yan, Fan Yang, Xiaoni Zhong, Feiyu Zhou, Ying Zhu, Yong Zhang, Saravanaraj Ayyampalayam, Todd J. Barkman, Nam-phuong Nguyen, Naim Matasci, David R. Nelson, Erfan Sayyari, Eric K. Wafula, Ramona L. Walls, Tandy Warnow, Hong An, Nils Arrigo, Anthony E. Baniaga, Sally Galuska, Stacy A. Jorgensen, Thomas I. Kidder, Hanghui Kong, Patricia Lu-Irving, Hannah E. Marx, Xinshuai Qi, Chris R. Reardon, Brittany L. Sutherland, George P. Tiley, Shana R. Welles, Rongpei Yu, Shing Zhan, Lydia Gramzow, Günter Theißen, and Gane Ka-Shu Wong

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41586-019-1693-2.

References

- 1.Corlett RT. Plant diversity in a changing world: status, trends, and conservation needs. Plant Divers. 2016;38:10–16. doi: 10.1016/j.pld.2016.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lughadha EN, et al. Counting counts: revised estimates of numbers of accepted species of flowering plants, seed plants, vascular plants and land plants with a review of other recent estimates. Phytotaxa. 2016;272:82–88. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kumar S, Stecher G, Suleski M, Hedges SB. TimeTree: a resource for timelines, timetrees, and divergence times. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2017;34:1812–1819. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msx116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schery, R. W. Plants for Man 2nd edn (Prentice-Hall, 1972).

- 5.Philippe H, Delsuc F, Brinkmann H, Lartillot N. Phylogenomics. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2005;36:541–562. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eisen JA. Phylogenomics: improving functional predictions for uncharacterized genes by evolutionary analysis. Genome Res. 1998;8:163–167. doi: 10.1101/gr.8.3.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Degnan JH, Rosenberg NA. Gene tree discordance, phylogenetic inference and the multispecies coalescent. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2009;24:332–340. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2009.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Solís-Lemus C, Yang M, Ané C. Inconsistency of species tree methods under gene flow. Syst. Biol. 2016;65:843–851. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/syw030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang Z, et al. Horizontal gene transfer is more frequent with increased heterotrophy and contributes to parasite adaptation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2016;113:E7010–E7019. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1608765113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rasmussen MD, Kellis M. Unified modeling of gene duplication, loss, and coalescence using a locus tree. Genome Res. 2012;22:755–765. doi: 10.1101/gr.123901.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ohno, S. Evolution by Gene Duplication (Springer-Verlag, 1970).

- 12.Force A, et al. Preservation of duplicate genes by complementary, degenerative mutations. Genetics. 1999;151:1531–1545. doi: 10.1093/genetics/151.4.1531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leitch, I. J. & Leitch, A. R. in Plant Genome Diversity Vol. 2 (eds Greilhuber, J. et al.) 307–322 (Springer, 2013).

- 14.Kapraun DF. Nuclear DNA content estimates in green algal lineages: chlorophyta and streptophyta. Ann. Bot. 2007;99:677–701. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcl294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mirarab S, Warnow T. ASTRAL-II: coalescent-based species tree estimation with many hundreds of taxa and thousands of genes. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:i44–i52. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barker MS, et al. Multiple paleopolyploidizations during the evolution of the Compositae reveal parallel patterns of duplicate gene retention after millions of years. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2008;25:2445–2455. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msn187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barker MS, et al. EvoPipes.net: Bioinformatic Tools for Ecological and Evolutionary Genomics. Evol. Bioinform. Online. 2010;6:143–149. doi: 10.4137/EBO.S5861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li Z, et al. Early genome duplications in conifers and other seed plants. Sci. Adv. 2015;1:e1501084. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1501084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Amborella Genome Project The Amborella genome and the evolution of flowering plants. Science. 2013;342:1241089. doi: 10.1126/science.1241089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ruelens P, et al. The origin of floral organ identity quartets. Plant Cell. 2017;29:229–242. doi: 10.1105/tpc.16.00366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vekemans D, et al. Gamma paleohexaploidy in the stem lineage of core eudicots: significance for MADS-box gene and species diversification. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2012;29:3793–3806. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mss183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vanneste K, Maere S, Van de Peer Y. Tangled up in two: a burst of genome duplications at the end of the Cretaceous and the consequences for plant evolution. Phil. Trans. R. Soc.B. 2014;369:20130353. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2013.0353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.The Tomato Genome Consortium The tomato genome sequence provides insights into fleshy fruit evolution. Nature. 2012;485:635–641. doi: 10.1038/nature11119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cannon SB, et al. Multiple polyploidy events in the early radiation of nodulating and nonnodulating legumes. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2015;32:193–210. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msu296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schranz ME, Mohammadin S, Edger PP. Ancient whole genome duplications, novelty and diversification: the WGD Radiation Lag-Time Model. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2012;15:147–153. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2012.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tank DC, et al. Nested radiations and the pulse of angiosperm diversification: increased diversification rates often follow whole genome duplications. New Phytol. 2015;207:454–467. doi: 10.1111/nph.13491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Landis JB, et al. Impact of whole-genome duplication events on diversification rates in angiosperms. Am. J. Bot. 2018;105:348–363. doi: 10.1002/ajb2.1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maere S, et al. Modeling gene and genome duplications in eukaryotes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:5454–5459. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501102102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hanada K, Zou C, Lehti-Shiu MD, Shinozaki K, Shiu S-H. Importance of lineage-specific expansion of plant tandem duplicates in the adaptive response to environmental stimuli. Plant Physiol. 2008;148:993–1003. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.122457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nelson D, Werck-Reichhart D. A P450-centric view of plant evolution. Plant J. 2011;66:194–211. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04529.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Simão FA, Waterhouse RM, Ioannidis P, Kriventseva EV, Zdobnov EM. BUSCO: assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:3210–3212. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bowman JL, et al. Insights into land plant evolution garnered from the Marchantia polymorpha genome. Cell. 2017;171:287–304. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Catarino B, Hetherington AJ, Emms DM, Kelly S, Dolan L. The stepwise increase in the number of transcription factor families in the Precambrian predated the diversification of plants on land. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2016;33:2815–2819. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wilhelmsson PKI, Mühlich C, Ullrich KK, Rensing SA. Comprehensive genome-wide classification reveals that many plant-specific transcription factors evolved in streptophyte algae. Genome Biol. Evol. 2017;9:3384–3397. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evx258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rodríguez-Ezpeleta N, et al. Monophyly of primary photosynthetic eukaryotes: green plants, red algae, and glaucophytes. Curr. Biol. 2005;15:1325–1330. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.06.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Qiu H, Price DC, Yang EC, Yoon HS, Bhattacharya D. Evidence of ancient genome reduction in red algae (Rhodophyta) J. Phycol. 2015;51:624–636. doi: 10.1111/jpy.12294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van Baren MJ, et al. Evidence-based green algal genomics reveals marine diversity and ancestral characteristics of land plants. BMC Genomics. 2016;17:267. doi: 10.1186/s12864-016-2585-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grosche C, Rensing SA. Three rings for the evolution of plastid shape: a tale of land plant FtsZ. Protoplasma. 2017;254:1879–1885. doi: 10.1007/s00709-017-1096-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wickett NJ, et al. Phylotranscriptomic analysis of the origin and early diversification of land plants. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:E4859–E4868. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1323926111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lewis LA, McCourt RM. Green algae and the origin of land plants. Am. J. Bot. 2004;91:1535–1556. doi: 10.3732/ajb.91.10.1535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Becker B, Marin B. Streptophyte algae and the origin of embryophytes. Ann. Bot. 2009;103:999–1004. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcp044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marin B. Nested in the Chlorellales or independent class? Phylogeny and classification of the Pedinophyceae (Viridiplantae) revealed by molecular phylogenetic analyses of complete nuclear and plastid-encoded rRNA operons. Protist. 2012;163:778–805. doi: 10.1016/j.protis.2011.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cocquyt E, Verbruggen H, Leliaert F, De Clerck O. Evolution and cytological diversification of the green seaweeds (Ulvophyceae) Mol. Biol. Evol. 2010;27:2052–2061. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msq091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Delaux P-M, et al. Algal ancestor of land plants was preadapted for symbiosis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:13390–13395. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1515426112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]