Abstract

Swine dysentery and necrotic enteritis are a bane to animal husbandry worldwide. Some countries have already banned the use of antibiotics as growth promoters in animal production. Surfactin is a potential alternative to antibiotics and antibacterial agents. However, the antibacterial activity of Bacillus species-derived surfactin on Brachyspira hyodysenteriae and Clostridium perfringens are still poorly understood. In the current study, the antibacterial effects of surfactin produced from Bacillus subtilis and Bacillus licheniformis on B. hyodysenteriae and C. perfringens were evaluated. Results showed that multiple surfactin isoforms were detected in B. subtilis, while only one surfactin isoform was detected in B. licheniformis fermented products. The surfactin produced from B. subtilis exhibited significant antibacterial activity against B. hyodysenteriae compared with surfactin produced from B. licheniformis. B. subtilis-derived surfactin could inhibit bacterial growth and disrupt the morphology of B. hyodysenteriae. Furthermore, the surfactin produced from B. subtilis have the highest activity against C. perfringens growth. In contrast, B. licheniformis fermented product-derived surfactin had a strong bacterial killing activity against C. perfringens compared with surfactin produced from B. subtilis. These results together suggest that Bacillus species-derived surfactin have potential for development as feed additives and use as a possible substitute for antibiotics to prevent B. hyodysenteriae and C. perfringens-associated disease in the animal industry.

Keywords: Antibacterial activity, Bacillus licheniformis, Brachyspira hyodysenteriae, Clostridium perfringens, Surfactin

Introduction

Swine dysentery (SD) caused by Brachyspira hyodysenteriae is a highly contagious disease of grower and finisher pigs. SD causes severe mucohemorrhagic diarrhea, resulting in decreased feed efficiency and increased morbidity (Alvarez-Ordóñez et al. 2013). Antibiotics, such as tiamulin and carbadox, are widely used for prevention and treatment of SD due to their relatively short withdrawal periods and the high susceptibility of Brachyspira species (van Duijkeren et al. 2014). However, accumulating evidence suggests that B. hyodysenteriae resistance to antibiotics is commonly observed (Mirajkar et al. 2016; Hampson et al. 2019).

Necrotic enteritis (NE) caused by Clostridium perfringens is characterized by high mortality in poultry with bloody diarrhea, and sudden death (Kaldhusdal and Løvland 2000; Lee et al. 2011). Predisposing factors for necrotic enteritis have been proposed, such as coccidiosis, stress, and nutritional factors (M’Sadeq et al. 2015). Bacitracin has been commonly used worldwide as an antibiotic growth promoter for prophylactic treatment of C. perfringens-induced NE in poultry (M’Sadeq et al. 2015; Caly et al. 2015). However, the European Union has already banned antibiotics used in animal production, resulting in increased NE outbreaks in broilers in European countries (Van der Sluis 2000; Van Immerseel et al. 2004).

Several antibiotic alternatives have been proposed for prophylactic treatment of diseases, such as probiotics (Abudabos et al. 2013, 2017; Cheng et al. 2018, 2019). In recent years, fermented products produced from Bacillus subtilis and Bacillus licheniformis have gained attention as probiotic supplements in animal feed due to the production of thermostable and low pH resistant spores (Cheng et al. 2018; Lin et al. 2019). B. subtilis and B. licheniformis have been identified from the gastrointestinal tract of broilers with antimicrobial activity (Barbosa et al. 2005; Cheng et al. 2018; Lin et al. 2019). Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that Bacillus species are able to produce a variety of antimicrobial peptides (Sumi et al. 2015). The surfactin, Bacillus-derived cyclic lipopeptide, is an important antimicrobial peptide with antibacterial activity through disruption of the bacterial membrane (Carrillo et al. 2003; Chen et al. 2008). However, whether B. subtilis and B. licheniformis-derived surfactin has antibacterial activity against B. hyodysenteriae and C. perfringens still remain to be elucidated.

SD and NE are prevalent and important enteric diseases, which lead to enormous economic losses in animal husbandry worldwide (Van der Sluis 2000; Timbermont et al. 2011; Card et al. 2018). The restrictions placed on the prophylactic use of antibiotics in animal production and the prevalence of multidrug resistant bacteria, mean that alternative solutions to prevent and treat SD and NE are an urgent unmet need in animal husbandry. In the present study, we investigated the antibacterial activity of Bacillus species-derived surfactin on B. hyodysenteriae and C. perfringens. The results provide valuable knowledge for understanding the antibacterial potential of surfactin-producing Bacillus species as a substitute for antibiotics.

Materials and methods

All experiments were performed in accordance with the approved guidelines.

Preparation of Bacillus species-derived surfactin

Bacillus subtilis-derived surfactin is a commercially available product (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). The B. licheniformis-derived surfactin was extracted from solid-state fermented products. The B. licheniformis was purchased from the Food Industry Research and Development Institute (ATCC 12713, Hsinchu, Taiwan). Details of B. licheniformis-fermented product preparation were as described in a previous study (Lin et al. 2019). After thawing, the B. licheniformis was inoculated into an Erlenmeyer flask containing tryptic soy broth (TSB; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and incubated at 30 °C for 18 h with shaking at 160 rpm. The solid-state fermentation substrates in a space bag were inoculated with 4% (v/w) inoculum of B. licheniformis and incubated at 30 °C in a chamber with free oxygen and relative humidity above 80% for 6 days. The fermented products were dried at 50 °C for 2 days and homogenized by mechanical agitation. The fermented powder was then stored at 4 °C prior to analysis.

Extraction and analysis of surfactin

The supernatant of B. licheniformis-fermented products was adjusted to pH 2.0 with concentrated HCl and incubated overnight at 4 °C. The precipitate was dissolved in distilled water and extracted with methanol. The mixture was shaken vigorously and the organic phase was concentrated at reduced pressure at 40 °C. The extract was further filtered using a syringe filter with a 0.22 μm membrane. The surfactin concentration in the filtrate was quantified and measured using high performance liquid chromatography. The SPD-10A system (Shimadzu, Columbia, MD, USA) with a programmable UV detector (10A VP, Shimadzu, Columbia, MD, USA) and a reverse phase RP-18 column (LiChrospher 100 RP-18 endcapped, 5 μm) was used throughout the experiments. Samples were injected into the HPLC column. The mobile phase consisted of 3.8 mM trifluoroacetic acid: acetonitrile (20:80, v/v). The flow rate was 1 ml/min. Surfactin was determined at a wavelength of 210 nm by use of a UV detector. The recorder was set to 30 min.

Test bacteria

Brachyspira hyodysenteriae (ATCC 27164) was cultured in brain heart infusion broth (BHIB, EMD Millipore, Danvers, MA, USA). Clostridium perfringens (ATCC13124) was cultured in Gifu anaerobic medium (GAM; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). After two successive transfers of the test organisms in specific culture media, the activated culture was inoculated into specific culture media for further quantification.

Confocal microscopy

BHIB containing different dilutions of B. subtilis-derived surfactin (concentration range from 9.31 to 500 μg/ml) was incubated with B. hyodysenteriae (104 CFU/ml) at 42 °C for 0.5 h and 1 h, respectively. GAM containing different dilutions of B. subtilis-derived surfactin (concentration range from 7.8 to 500 μg/ml) was incubated with C. perfringens (104 CFU/ml) at 37 °C for 0.5 h and 1 h, respectively. After incubation, SYBR Green I, propidium iodide and Hoechst 33342 were added to each well and then stained at 37 °C for 30 min in the dark. The stained samples were examined under a confocal laser-scanning microscope (ZEISS LSM800, Jena, Germany). For the detection of the SYBR Green I stained cells, 497 nm excitation wavelengths and 520 nm emission wavelengths were used. For the detection of the propidium iodide stained cells, 530 nm excitation wavelengths and 620 nm emission wavelengths were applied. For the detection of the Hoechst 33342 stained cells, 335 nm excitation and 460 nm emission were used. The number of live (green) or dead (red) cells were viewed and counted manually using the ImageJ software.

Agar-well diffusion assay

The B. subtilis and B. licheniformis-derived surfactin were serially diluted (concentration range from 7.8 to 500 μg/ml) and transferred into a well in tryptic soy agar (TSB; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) containing 5% goat blood (collected from healthy goat in experimental farm of National Ilan University) and B. hyodysenteriae (1 × 104 CFU/ml), or Gifu anaerobic medium agar (GAM agar; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) containing the C. perfringens (1 × 104 CFU/ml), respectively. For measurement of the inhibition zone of B. hyodysenteriae, the plates were incubated at 42 °C for 24 h. For measurement of the inhibition zone of C. perfringens, the plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. The antibacterial activity of surfactin was determined by measuring the diameter of this zone of inhibition using the ImageJ software (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA).

Antibacterial assay

The antibacterial activity of surfactin was studied by employing a microdilution method. The B. subtilis and B. licheniformis-derived surfactin were serially diluted (concentration range from 31.25 to 500 μg/ml). One hundred microliters of BHIB containing different dilutions were distributed in 96-well plates. Each well was inoculated with B. hyodysenteriae (104 CFU/ml) and incubated anaerobically at 42 °C for 0.5 h and 1 h, respectively. One hundred microliters of GAM containing different dilutions were distributed in 96-well plates. Each well was inoculated with C. perfringens (104 CFU/ml) and incubated anaerobically at 37 °C for 0.5 h and 1 h, respectively. All experiments were performed in triplicate. The bacterial survival analyzed by turbidity was detected using optical density at 600 nm (EMax Plus Microplate Reader, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). Data were normalized by absorbance and by negative controls, with untreated sample set at 100% survival.

Scanning electron microscopy

BHIB containing different dilutions of B. subtilis-derived surfactin (concentration range from 10 to 250 μg/ml) was incubated with B. hyodysenteriae (104 CFU/ml) at 42 °C for 1 h, respectively. The cells were fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 6.8) overnight at 4 °C, and then washed three times with 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 6.8). Dehydration was performed in different concentrations of ethanol (50–100%) for 10 min each and the samples were dried in a critical point drier (CPD 030, Bal-Tec AG, Balzers, Liechtenstein). Specimens were coated under vacuum with gold: palladium (60:40) in a sputter coater (Bal-Tec AG, Balzers, Liechtenstein), and examined using a scanning electron microscope (JSM-6300, JEOL Ltd., Tokyo, JAPAN).

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed by one‐way ANOVA using the GLM procedure of the SAS software package (Version 9.4; SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Replicates were considered the experimental units. Results were expressed as mean ± SD. Means were compared by employing Tukey’s HSD test at a significance level of P < 0.05.

Results

Identification of surfactin from B. subtilis and B. licheniformis

The chromatographic peak of B. subtilis and B. licheniformis-derived surfactin is presented in Fig. 1. Results showed that multiple retention peaks were detected in the B. subtilis-derived surfactin (Fig. 1a). However, only a single peak of surfactin from B. licheniformis fermented products was detected which had a chromatogram identical to surfactin C in B. subtilis-derived surfactin (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1.

HPLC chromatogram of surfactin. a The chromatographic peak of B. subtilis-derived surfactin and b B. licheniformis-fermented product-derived surfactin

Antibacterial activity of Bacillus species-derived surfactin on B. hyodysenteriae

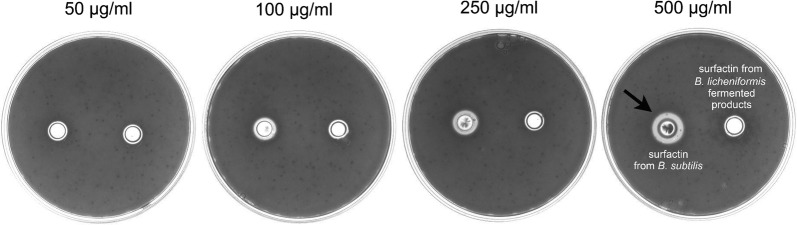

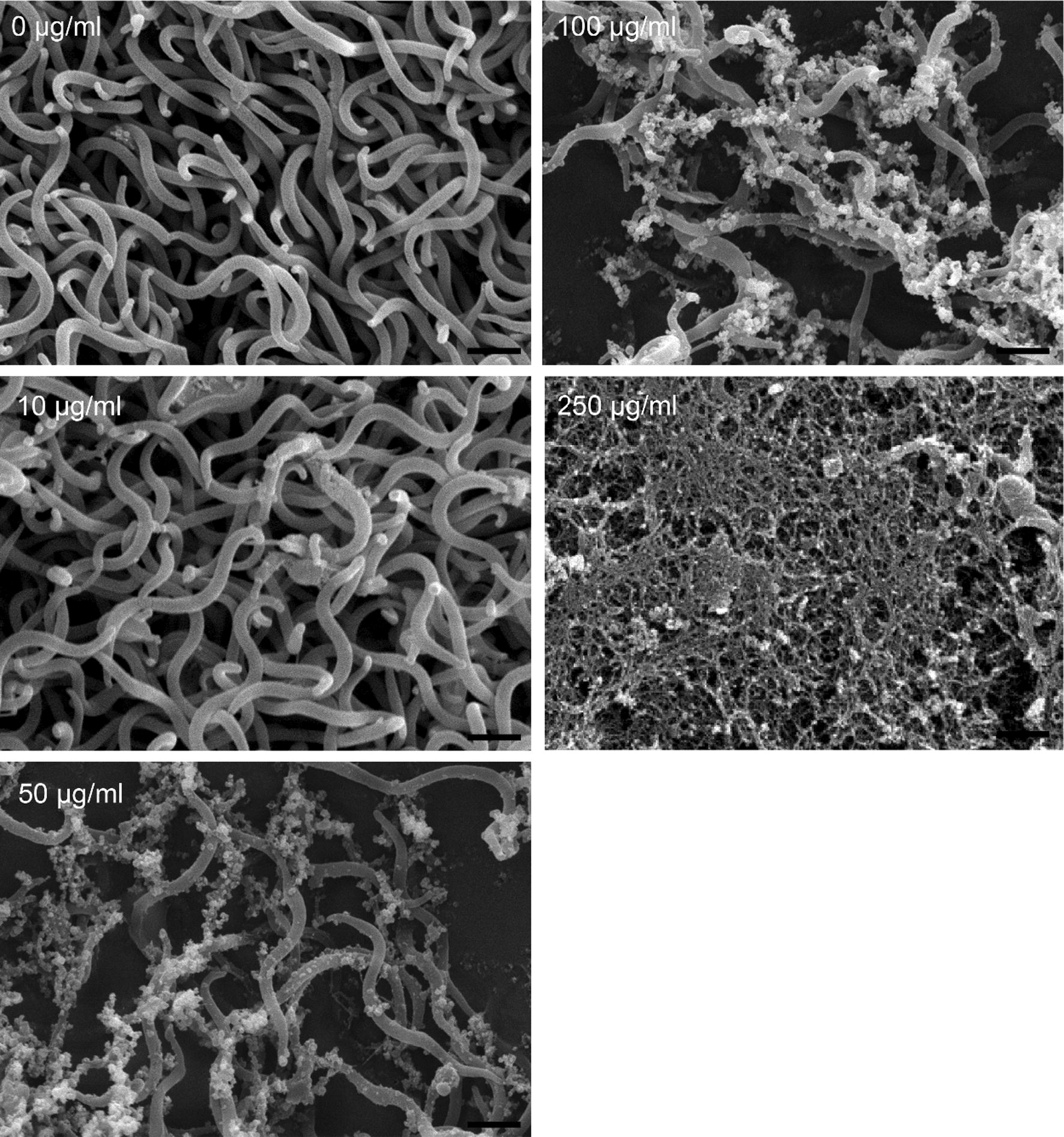

Results of confocal microscopy examinations showed that B. subtilis-derived surfactin is able to cause the death of B. hyodysenteriae in a dose dependent manner (Fig. 2a). A longer duration (1 h) of B. subtilis-derived surfactin treatment could increase the death rate of B. hyodysenteriae (P < 0.05, Fig. 2a). Similarly, the surfactin from B. licheniformis fermented products also caused the death of B. hyodysenteriae in a dose dependent manner (Fig. 2b). Duration of treatment of B. licheniformis-derived surfactin did not affect the death rate of B. hyodysenteriae except with 9.31 μg/ml treatment (Fig. 2b). Relative to the surfactin from B. licheniformis fermented products, B. subtilis-derived surfactin had the highest antibacterial activity against B. hyodysenteria (Fig. 2a, b). Results of bacterial survival analysis by turbidity examinations showed that B. subtilis-derived surfactin significantly caused the death of B. hyodysenteriae in a dose dependent manner after 0.5 h treatment (P < 0.05, Table 1). However, prolonged treatment (1 h) of different concentrations of B. subtilis-derived surfactin did not further promote the death of B. hyodysenteriae. Results of agar-well diffusion assay revealed that B. subtilis-derived surfactin exhibited a significant inhibition zone compared with B. licheniformis fermented product-derived surfactin (Fig. 3). The results of quantification of the inhibition zone are presented in Table 2. Results showed that the B. subtilis-derived surfactin caused the inhibition of B. hyodysenteriae growth in a dose dependent manner (P < 0.05). Similarly, B. licheniformis fermented products also had a dose dependent inhibitory effect on B. hyodysenteriae growth (P < 0.05). The zone of inhibition of B. subtilis-derived surfactin on B. hyodysenteriae growth was greater than B. licheniformis fermented products-derived surfactin (P < 0.05). Furthermore, results of scanning electron microscopy showed that B. subtilis-derived surfactin could disrupt the morphology of B. hyodysenteriae in a dose dependent manner after 1 h treatment compared with the untreated group (Fig. 4).

Fig. 2.

Killing activity of surfactin against B. hyodysenteriae. a B. hyodysenteriae were incubated with different concentrations (9.31, 18.63, 37.25, 62.5, 125, 250, 500 μg/ml) of the B. subtilis-derived surfactin for 0.5 and 1 h. b B. hyodysenteriae were incubated with different concentrations (9.31, 18.63, 37.25, 62.5, 125, 250, 500 μg/ml) of the B. licheniformis-fermented product-derived surfactin for 0.5 and 1 h. The error bars represent the mean ± standard deviations from triplicate assays (n = 3). *P < 0.05 comparing data of 0.5 h versus 1 h

Table 1.

Percentage survival rate of B. hyodysenteriae in response to B. subtilis-derived surfactin treatment

| Concentration (μg/ml) | 0.5 h | 1 h | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survival rate (%) | ||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| 0 | 100a,d | 0 | 100a | 0 |

| 10 | 95.2a | 5.1 | 92.4a | 3.8 |

| 50 | 63.7b | 8.3 | 53.1b | 4.6 |

| 100 | 42.5bc | 3.5 | 38.2b | 7.4 |

| 250 | 12.8c | 6.7 | 12.4c | 5.2 |

a–cMeans within a column with no common superscript are significantly different (P <0.05)

dValues are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3)

Fig. 3.

Growth inhibitory zone of surfactin against B. hyodysenteriae using agar-well diffusion assay. B. hyodysenteriae were grown in the different concentrations (50, 100, 250, 500 μg/ml) of surfactin produced from B. subtilis (left) and B. licheniformis-fermented products (right) for 24 h. The black arrow indicates inhibition zone. Three experiments were conducted, and one representative result is presented

Table 2.

Measurement of zone of inhibition of surfactin on B. hyodysenteriae growth at different concentrations

| Concentration (μg/ml) | Surfactin from B. subtilis | Surfactin from B. licheniformis fermented products | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zone of inhibition (cm) | ||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| 50 | 0.3a,x,d | 0.02 | 0.2a,y | 0.01 |

| 100 | 0.6b,x | 0.03 | 0.2a,y | 0.01 |

| 250 | 0.9bc,x | 0.02 | 0.4b,y | 0.01 |

| 500 | 1.4c,x | 0.04 | 0.5b,y | 0.02 |

a–cMeans within a column with no common superscript are significantly different (P <0.05)

x–yMeans within a row with no common superscript are significantly different (P <0.05)

dValues are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3)

Fig. 4.

Scanning electron microscope images of B. hyodysenteriae illustrating the antibacterial activity of different concentrations (10, 50, 100, 250 μg/ml) of the commercial surfactin after incubating for 1 h. Three experiments were conducted, and one representative result is presented

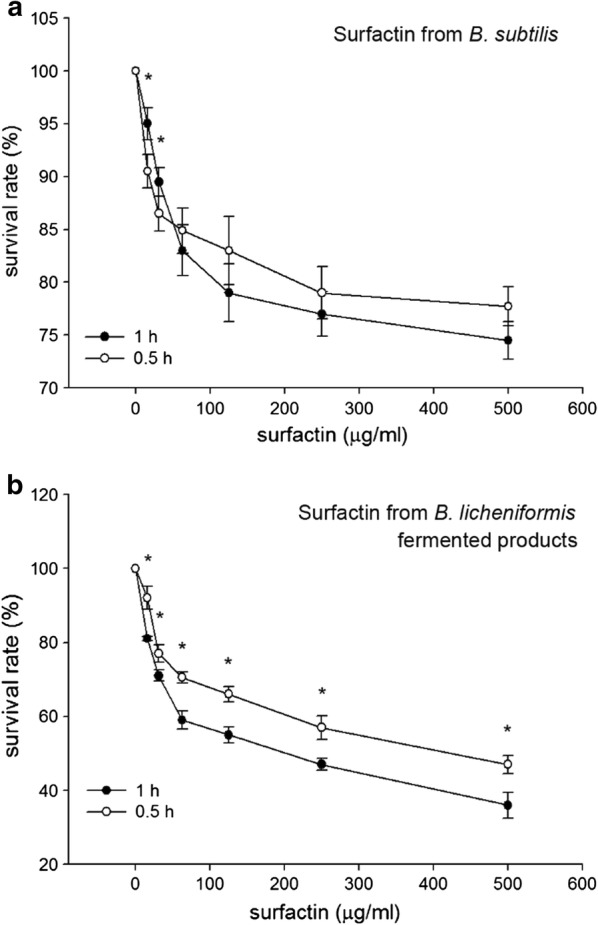

Antibacterial activity of Bacillus species-derived surfactin on C. perfringens

Results of confocal microscopy examinations showed that B. subtilis-derived surfactin is able to cause the death of C. perfringens in a dose dependent manner (Fig. 5a). A longer duration (1 h) of B. subtilis-derived surfactin treatment could increase the death rate of C. perfringens except at 7.8 and 15.62 μg/ml (P < 0.05, Fig. 5a). The surfactin from B. licheniformis fermented products also caused the death rate of C. perfringens to increase in a dose dependent manner (Fig. 5b). Similarly, a longer (1 h) duration of B. licheniformis fermented product-derived surfactin treatment could increase the death of C. perfringens (P < 0.05, Fig. 5b). Relative to B. subtilis-derived surfactin, surfactin from B. licheniformis fermented products had the highest antibacterial activity against C. perfringens (Fig. 5a, b). Results of bacterial survival analysis by turbidity examinations showed that B. subtilis-derived surfactin significantly caused the death of C. perfringens in a dose dependent manner after 0.5 h treatment (P < 0.05, Table 3). Prolonged treatment (1 h) of different concentrations of B. subtilis-derived surfactin could further promote the death of C. perfringens (P < 0.05). Results of agar-well diffusion assay showed that B. subtilis-derived surfactin exhibited a significant inhibition zone (250 μg/ml and 500 μg/ml) compared with B. licheniformis fermented product-derived surfactin (Fig. 6). The results of quantification of the inhibition zone are presented in Table 4. Results showed that B. subtilis-derived surfactin caused the inhibition of C. perfringens growth in a dose dependent manner (P < 0.05). Similarly, B. licheniformis fermented product-derived surfactin also had a dose dependent inhibitory effect on C. perfringens growth (P < 0.05). In addition, the zone of inhibition of B. subtilis-derived surfactin on C. perfringens growth was greater than B. licheniformis fermented product-derived surfactin (P < 0.05).

Fig. 5.

Killing activity of surfactin against C. perfringens. a C. perfringens were incubated with different concentrations (7.8, 15.62, 31.25, 62.5, 125, 250, 500 μg/ml) of the B. subtilis-derived surfactin for 0.5 and 1 h. b C. perfringens were incubated with different concentrations (7.8, 15.62, 31.25, 62.5, 125, 250, 500 μg/ml) of the B. licheniformis-fermented products-derived surfactin for 0.5 and 1 h. The error bars represent the mean ± standard deviations from triplicate assays (n = 3). *P < 0.05 comparing data of 0.5 h versus 1 h

Table 3.

Percentage survival rate of the C. perfringens in response to B. subtilis-derived surfactin treatment

| Concentration (μg/ml) | 0.5 h | 1 h | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survival rate (%) | ||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| 0 | 98.0a,x,d | 2.8 | 95a,x | 2.2 |

| 31.25 | 89.1a,x | 9.2 | 83ab,x | 3.8 |

| 62.5 | 81.3ab,x | 10.3 | 72b,x | 3.4 |

| 125 | 72.1ab,x | 1.2 | 57c,y | 2.1 |

| 250 | 68.4b,x | 5.4 | 52c,y | 7.9 |

a–cMeans within a column with no common superscript are significantly different (P <0.05)

x–yMeans within a row with no common superscript are significantly different (P <0.05)

dValues are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3)

Fig. 6.

Growth inhibitory zone of surfactin against C. perfringens using agar-well diffusion assay. C. perfringens were grown in the different concentrations (50, 100, 250, 500 μg/ml) of the surfactin produced from B. subtilis (top left) and B. licheniformis-fermented products (bottom left), blank (top right), and ampicillin (bottom right) for 24 h. The black arrow indicates the inhibition zone. Three experiments were conducted, and one representative result is presented

Table 4.

Measurement of zone of inhibition of surfactin on C. perfringens growth at different concentrations

| Concentration (μg/ml) | Surfactin from B. subtilis | Surfactin from Bacillus licheniformis fermented products | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zone of inhibition (cm) | ||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| 31.25 | 0.6a,x,e | 0.04 | 0.5a,y | 0.00 |

| 62.5 | 0.6a,x | 0.02 | 0.5a,y | 0.01 |

| 125 | 0.9b,x | 0.02 | 0.6b,y | 0.03 |

| 250 | 1.0c,x | 0.05 | 0.6b,y | 0.03 |

| 500 | 1.3d,x | 0.03 | 1.1c,y | 0.03 |

a–dMeans within a column with no common superscript are significantly different (P <0.05)

x–yMeans within a row with no common superscript are significantly different (P <0.05)

eValues are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3)

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated that surfactin either from B. subtilis or B. licheniformis fermented products is able to inhibit the growth of B. hyodysenteriae and C. perfringens. The B. subtilis-derived surfactin exhibited the greatest bacterial killing activity against B. hyodysenteriae. In contrast, B. licheniformis fermented product-derived surfactin had the highest bacterial killing activity against C. perfringens.

Surfactin as a secondary metabolite was first found in B. subtilis and consists of multiple isoforms (Haddad et al. 2008; Sousa et al. 2014; Sumi et al. 2015). The structure of surfactin is a seven amino acid peptide loop and a hydrophobic fatty acid chain (Kowall et al. 1998). It has been reported that surfactin has a broad spectrum of antimicrobial activity against pathogenic microbes (Chen et al. 2008; Sumi et al. 2015). Our previous study demonstrated that B. subtilis-fermented products with the highest surfactin concentration show antibacterial activity against Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, Salmonella typhimurium and C. perfringens in vitro (Cheng et al. 2018). A previous study showed that surfactin produced by different strains of B. subtilis exhibited diverse antibacterial activity (Sabaté and Audisio 2013). Since most Bacillus species can produce two or three types of lipopeptides (Sumi et al. 2015). It has been demonstrated that commercial surfactin (Sigma-Aldrich), produced from B. subtilis, has six isoforms (Sousa et al. 2014). Similarly, we also found that multiple isoforms of surfactin were identified in the commercial surfactin in the present study. Environmental and nutritional conditions are critical factors for determining the surfactin isoforms of B. subtilis (Peypoux and Michel 1992; Kowall et al. 1998). Thus, it is possible that a proportion of surfactin isoforms might exhibit differential antibacterial property in B. subtilis. However, the effect of surfactin isoforms isolated from Bacillus species and any interaction between surfactin isoforms on antibacterial activity have not been studied.

In addition to B. subtilis, B. licheniformis also has the ability to synthesize antimicrobial substances, such as surfactin (Pecci et al. 2010; Sumi et al. 2015). This antimicrobial substance shows antibacterial activity against a wide range of Gram-positive bacteria, such as Listeria monocytogenes and Methicillin-resistant S. aureus, but does not cause hemolysis or inhibit the growth of Gram-negative bacteria (Dischinger et al. 2009; Abdel-Mohsein et al. 2011). To date, the isoforms of surfactin and antibacterial activity in B. licheniformis have rarely been studied. Here, we demonstrated for the first time that the major isoform of surfactin in B. licheniformis was surfactin C. Furthermore, surfactin C extracted from B. licheniformis fermented products had antibacterial activity against B. hyodysenteriae and C. perfringens. Our previous study has demonstrated that B. licheniformis-fermented products were able to inhibit the growth of C. perfringens and S. aureus in vitro (Lin et al. 2019). Taken together, these findings indicate that the antibacterial activity of B. licheniformis might be mediated by producing surfactin C.

Brachyspira-associated diseases, such as SD, are effectively treated with macrolides, lincosamides, and carbadox (Hampson et al. 2019). Morbidity in finishing pigs with SD ranges from 50 to 90% (Burrough 2016). Trends of decreasing susceptibility among B. hyodysenteriae for the macrolides and pleuromutilins have been well documented (Rugna et al. 2015; Mirajkar et al. 2016). It has been reported that B. subtilis is able to inhibit the growth of B. hyodysenteriae in vitro (Klose et al. 2010). Here, we further demonstrated that commercial surfactin produced from B. subtilis and B. licheniformis fermented product-derived surfactin had antibacterial activity against B. hyodysenteriae. Furthermore, the morphology of B. hyodysenteriae was disrupted after B. subtilis-derived surfactin treatment. Several antimicrobial mechanisms of surfactin have been proposed and characterized, including insertion into lipid bilayers, membrane solubilization, destabilization of membrane permeability by channel formation and chelating of mono-and divalent cations (Seydlová and Svobodová 2008). However, the precise mechanisms through which surfactin exerts antibacterial activity on B. hyodysenteriae need further investigation.

Our previous study demonstrated that B. subtilis and B. licheniformis-fermented products can inhibit the growth of C. perfringens in vitro (Cheng et al. 2018; Lin et al. 2019). We further found that surfactin isolated from B. licheniformis-fermented products exerts antibacterial activity against C. perfringens, implying that the most important antibacterial factor is surfactin in B. licheniformis-fermented products. Interestingly, differential antibacterial activity against C. perfringens between surfactin from B. subtilis and B. licheniformis was demonstrated in the present study. Commercial surfactin extracted from B. subtilis consists of multiple isoforms, while a sole isoform of surfactin (C) was identified in B. licheniformis-fermented products; however, whether there is any interaction among the surfactin isoforms which affects antibacterial activity remains to be elucidated.

In conclusion, this paper provides evidence that surfactin has antibacterial activity against B. hyodysenteriae and C. perfringens. The surfactin produced from B. subtilis have the highest activity against B. hyodysenteriae and C. perfringens growth. The B. subtilis-derived surfactin exhibited better bacterial killing activity against B. hyodysenteriae. In contrast, B. licheniformis fermented product-derived surfactin showed stronger bacterial killing activity against C. perfringens.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Authors’ contributions

YHC and YHY designed the experiments; YBH, AD, FSHH and YHY performed experimental research and data analysis. YBH, YHY and YHC wrote and edited the manuscript text. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology (Grant Nos. MOST 107-2321-B-197-002 and MOST 108-2321-B-197-001) in Taiwan.

Availability of data and materials

Please contact to the authors for all request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All the animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of National Ilan University, Yilan, Taiwan.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Yi-Bing Horng and Yu-Hsiang Yu contributed equally to this work

References

- Abdel-Mohsein H, Sasaki T, Tada C, Nakai Y. Characterization and partial purification of a bacteriocin-like substance produced by thermophilic Bacillus licheniformis H1 isolated from cow manure compost. Anim Sci J. 2011;82:340–351. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-0929.2010.00835.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abudabos AM, Alyemni AH, Al Marshad MBA. Bacillus Subtilis PB6 based probiotic (CLOSTATTM) improves intestinal morphological and microbiological status of broiler chicken under Clostridium perfringens challenge. Int J Agric Biol. 2013;15:978–982. [Google Scholar]

- Abudabos AM, Alyemni AH, Dafalla YM, Khan RU. Effect of organic acid blend and Bacillus subtilis alone or in combination on growth traits, blood biochemical and antioxidant status in broilers exposed to Salmonella typhimurium challenge during the starter phase. J Appl Anim Res. 2017;45:538–542. doi: 10.1080/09712119.2016.1219665. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Ordóñez A, Martínez-Lobo FJ, Arguello H, Carvajal A, Rubio P. Swine dysentery: aetiology, pathogenicity, determinants of transmission and the fight against the disease. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2013;10:1927–1947. doi: 10.3390/ijerph10051927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa TM, Serra CR, La Ragione RM, Woodward MJ, Henriques AO. Screening for Bacillus isolates in the broiler gastrointestinal tract. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71:968–978. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.2.968-978.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burrough ER. Swine dysentery. Vet Pathol. 2016;54:22–31. doi: 10.1177/0300985816653795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caly DL, D’Inca R, Auclair E, Drider D. Alternatives to antibiotics to prevent necrotic enteritis in broiler chickens: a microbiologist’s perspective. Front Microbiol. 2015;6:1336. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.01336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Card RM, Stubberfield E, Rogers J, Nunez-Garcia J, Ellis RJ, AbuOun M, Strugnell B, Teale C, Williamson S, Anjum MF. Identification of a new antimicrobial resistance gene provides fresh insights into pleuromutilin resistance in Brachyspira hyodysenteriae, aetiological agent of swine dysentery. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:1183. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrillo C, Teruel JA, Aranda FJ, Ortiz A. Molecular mechanism of membrane permeabilization by the peptide antibiotic surfactin. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2003;1611:91–97. doi: 10.1016/S0005-2736(03)00029-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Wang L, Su CX, Gong GH, Wang P, Yu ZL. Isolation and characterization of lipopeptide antibiotics produced by Bacillus subtilis. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2008;47:180–186. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2008.02412.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng YH, Zhang N, Han JC, Chang CW, Hsiao FSH, Yu YH. Optimization of surfactin production from Bacillus subtilis in fermentation and its effects on Clostridium perfringens-induced necrotic enteritis and growth performance in broilers. J Anim Physiol Anim Nutr. 2018;102:1232–1244. doi: 10.1111/jpn.12937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng YH, Hsiao FSH, Wen CM, Wu CY, Dybus A, Yu YH. Mixed fermentation of soybean meal by protease and probiotics and its effects on growth performance and immune response in broilers. J Appl Anim Res. 2019;47:339–348. doi: 10.1080/09712119.2019.1637344. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dischinger J, Josten M, Szekat C, Sahl HG, Bierbaum G. Production of the novel two-peptide lantibiotic lichenicidin by Bacillus licheniformis DSM 13. PLoS ONE. 2009;4(8):e6788. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haddad NI, Liu X, Yang S, Mu B. Surfactin isoforms from Bacillus subtilis HSO121: separation and characterization. Protein Pept Lett. 2008;15:265–269. doi: 10.2174/092986608783744225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampson DJ, Lugsomya K, La T, Phillips ND, Trott DJ, Abraham S. Antimicrobial resistance in Brachyspira—an increasing problem for disease control. Vet Microbiol. 2019;229:59–71. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2018.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaldhusdal M, Løvland A. The economical impact of Clostridium perfringens is greater than anticipated. World Poult. 2000;16:50–51. [Google Scholar]

- Klose V, Bruckbeck R, Henikl S, Schatzmayr G, Loibner AP. Identification and antimicrobial susceptibility of porcine bacteria that inhibit the growth of Brachyspira hyodysenteriae in vitro. J Appl Microbiol. 2010;108:1271–1280. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2009.04521.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowall M, Vater J, Kluge B, Stein T, Franke P, Ziessow D. Separation and characterization of surfactin isoforms produced by Bacillus subtilis OKB 105. J Colloid Interface Sci. 1998;204:1–8. doi: 10.1006/jcis.1998.5558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee KW, Lillehoj HS, Jeong W, Jeoung HY, An DJ. Avian necrotic enteritis: experimental models, host immunity, pathogenesis, risk factors, and vaccine development. Poult Sci. 2011;90:1381–1390. doi: 10.3382/ps.2010-01319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin ER, Cheng YH, Hsiao FSH, Proskura WS, Dybus A, Yu YH. Optimization of solid-state fermentation conditions of Bacillus licheniformis and its effects on Clostridium perfringens-induced necrotic enteritis in broilers. R Bras Zootec. 2019;48:e20170298. doi: 10.1590/rbz4820170298. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mirajkar NS, Davies PR, Gebhart CJ. Antimicrobial susceptibility patterns of Brachyspira species isolated from swine herds in the United States. J Clin Microbiol. 2016;54(8):2109–2119. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00834-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- M’Sadeq SA, Wu S, Swick RA, Choct M. Towards the control of necrotic enteritis in broiler chickens with in-feed antibiotics phasing-out worldwide. Anim Nutr. 2015;1:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.aninu.2015.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pecci Y, Rivardo F, Martinotti MG, Allegrone G. LC/ESI-MS/MS characterisation of lipopeptide biosurfactants produced by the Bacillus licheniformis V9T14 strain. J Mass Spectrom. 2010;45:772–778. doi: 10.1002/jms.1767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peypoux F, Michel G. Controlled biosynthesis of Val7- and Leu7-surfactins. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1992;36:515–517. doi: 10.1007/BF00170194. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rugna G, Bonilauri P, Carra E, Bergamini F, Luppi A, Gherpelli Y, Magistrali CF, Nigrelli A, Alborali GL, Martelli P, La T, Hampson DJ, Merialdi G. Sequence types and pleuromutilin susceptibility of Brachyspira hyodysenteriae isolates from Italian pigs with swine dysentery: 2003–2012. Vet J. 2015;203:115–119. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2014.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabaté DC, Audisio MC. Inhibitory activity of surfactin, produced by different Bacillus subtilis subsp. subtilis strains, against Listeria monocytogenes sensitive and bacteriocin-resistant strains. Microbiol Res. 2013;168:125–129. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2012.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seydlová G, Svobodová J. Review of surfactin chemical properties and the potential biomedical applications. Cent Eur J Med. 2008;3:123–133. doi: 10.2478/s11536-008-0002-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sousa M, Dantas IT, Feitosa FX, Alencar AEV, Soares SA, Melo VMM, Gonçalves LRB, Sant’ana HB. Performance of a biosurfactant produced by Bacillus subtilis LAMI005 on the formation of oil/biosurfactant/water emulsion: study of the phase behaviour of emulsified systems. Braz J Chem Eng. 2014;31:613–623. doi: 10.1590/0104-6632.20140313s00002766. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sumi CD, Yang BW, Yeo IC, Hahm YT. Antimicrobial peptides of the genus Bacillus: a new era for antibiotics. Can J Microbiol. 2015;61:93–103. doi: 10.1139/cjm-2014-0613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timbermont L, Haesebrouck F, Ducatelle R, Van Immerseel F. Necrotic enteritis in broilers: an updated review on the pathogenesis. Avian Pathol. 2011;40:341–347. doi: 10.1080/03079457.2011.590967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Sluis W. Clostridial enteritis is often an underestimated problem. World Poult. 2000;16:42–43. [Google Scholar]

- van Duijkeren E, Greko C, Pringle M, Baptiste KE, Catry B, Jukes H, Moreno MA, Pomba MC, Pyörälä S, Rantala M, Ružauskas M, Sanders P, Teale C, Threlfall EJ, Torren-Edo J, Törneke K. Pleuromutilins: use in food-producing animals in the European Union, development of resistance and impact on human and animal health. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2014;69:2022–2031. doi: 10.1093/jac/dku123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Immerseel F, De Buck J, Pasmans F, Huyghebaert G, Haesebrouck F, Ducatelle R. Clostridium perfringens in poultry: an emerging threat for animal and public health. Avian Pathol. 2004;33:537–549. doi: 10.1080/03079450400013162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Please contact to the authors for all request.