Abstract

Terminalia Linn, a genus of mostly medium or large trees in the family Combretaceae with about 250 species in the world, is distributed mainly in southern Asia, Himalayas, Madagascar, Australia, and the tropical and subtropical regions of Africa. Many species are used widely in many traditional medicinal systems, e.g., traditional Chinese medicine, Tibetan medicine, and Indian Ayurvedic medicine practices. So far, about 39 species have been phytochemically studied, which led to the identification of 368 compounds, including terpenoids, tannins, flavonoids, phenylpropanoids, simple phenolics and so on. Some of the isolates showed various bioactivities, in vitro or in vivo, such as antitumor, anti HIV-1, antifungal, antimicrobial, antimalarial, antioxidant, diarrhea and analgesic. This review covers research articles from 1934 to 2018, retrieved from SciFinder, Wikipedia, Google Scholar, Chinese Knowledge Network and Baidu Scholar by using “Terminalia” as the search term (“all fields”) with no specific time frame setting for the search. Thirty-nine important medicinal and edible Terminalia species were selected and summarized on their geographical distribution, traditional uses, phytochemistry and related pharmacological activities.

Keywords: Terminalia, Combretaceae, Ethnomedicine, Traditional uses, Phytochemistry, Hydrolyzable tannins, Pharmacology

Introduction

Terminalia Linn, comprising about 250 species in the world mostly as medium or large trees, is the second largest genus in the family Combretaceae. The name “Terminalia” is derived from Latin word “terminus”, which means the leaves are located at the tip of the branch. The bark of Terminalia plants usually has cracks and branches tucked into layers. Most of the Terminalia plants’ leaves are large, leathery with solitary or clustered small green white flowers. Their fruits are yellow, dark red or black; drupe, usually angular or winged. Some fruits are edible, highly nutritious and possess medicinal values.

Terminalia species are widely distributed in the southern Asia, Himalayas, Madagascar, Australia, and the tropical and subtropical regions of Africa. Terminalia plants in southern Asia have been intensively studied phytochemically due to their wide usage in Asian (India, Tibetan, and Chinese) traditional medicine systems [1]. For example, the fruits of Terminalia bellirica and Terminalia chebula, together with Phyllanthus emblica (Euphorbiaceae) which form the herbal remedy, Triphala, in Tibetan medicine, have received much attention because of its extensive and remarkable effectiveness in the treatment of anticancer, antifungal, antimicrobial, antimalarial, antioxidant.

So far, 39 Terminalia species have been investigated for their phytochemical constituents, which resulted in the identification of terpenes, tannins, flavonoids, lignans and simple phenols, amongst others. Pharmacological studies suggest that they have exhibited activity on liver and kidney protection, antibacterial, antiinflammatory, anticancer, and have displayed a positive effect on immune regulation, cardiovascular disease and diabetes, and acceleration of wound healing.

This paper features 39 important medicinal and edible Terminalia species and summarizes their traditional usage, geographical distribution, structures of isolated chemical constituents and pharmacological activities.

Species’ Description, Distribution and Traditional Uses

So far, 50 Terminalia species have been documented, 39 of which have been reported to possess medicinal properties and/or being edible. Among them, eight species and four varieties including T. argyrophylla, T. bellirica, T. catappa, T. chebula, T. franchetii, T. hainanensis, T. myriocarpa, T. intricate, T. chebula var. tomentella, T. franchetii var. membranifolia, T. franchetii var. glabra, and T. myriocarpa var. hirsuta are distributed in China (Yunnan, southeast Tibet, Taiwan, Guangdong, south Guangxi and southwest Sichuan). Their distribution and traditional applications are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Local names, distributions and traditional uses of Terminalia plants

| No. | Plants | Local names | Distributions | Traditional uses |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | T. alata | Unknown | Southern Vietnam [2, 3] | Anti-diarrhea, ulcer, diuretics, supplements [3] |

| T2 | T. amazonia | White olive | Southern Costa Rica [4] | Wood |

| T3 | T. arborea | Jaha Kling | Indonesia | Cardiovascular disease, myocardial infarction, atherosclerosis, diabetes, cancer, stroke, cataract, shoulder stiffness, cold allergy, hypertension, senile dementia, inflammation, gum disease (e.g. gingivitis, pneumonia), Alzheimer’s, skin conditions [5] |

| T4 | T. arjuna | Arjuna, White Marudah, Koha | India, South Asia, Sri Lanka [6] |

Cardiotonic, sores, bile infection, poison antidote [6] Coughs, dysentery, fractures, contusions, ulcers, hypertension ischaemic heart diseases [23] |

| T5 | T. argyrophylla | Silver leaves Chebula, Xiao Chebula (Yunnan), Manna (Yunnan Dai language) | China (Yunnan) [7] | Autoimmune diseases [7] |

| T6 | T. australis | Tanimbu, palo amarillo | Punta Lara, Argentina (Buenos Aires) [8] | Hemostasis |

| T7 | T. avicennioides | kpayi, Kpace, baushe | Nigeria [9, 10] | Malaria, worms, gastric peptic ulcer [9], scorpion bites [10], tuberculosis, cough [90] |

| T8 | T. bellirica | Beleric | China (southern Yunnan), Vietnam, Laos, Thailand, Cambodia, Myanmar, India (except West), Malaysia, Indonesia |

Laxative, edible Edema, diarrhea, leprosy, bile congestion, indigestion, headache [11] Fever, diarrhea, cough, dysentery, skin diseases [12] Wine, palm sugar [23] Diarrhea [94] |

| T9 | T. bentzoe | Unknown | Rodrigues [13] | Essential oil [13] |

| T10 | T. bialata | Indian silver greywood | India, South Asia | Wood [14] |

| T11 | T. brachystemma | Kalahari cluster leaf | Southern Africa | Shistosomiasis, gastrointestinal disorders [15] |

| T12 | T. brownii | kuuku, muvuku (Kamba, Kenya), koloswa (northern region, Kenya), weba (Ethiopia), lbukoi (Samburu, Kenya), orbukoi (Maasai, Tanzania), and mbarao or mwalambe, in Kiswahili | Southern and central Africa |

Diarrhea, stomach pain, gastric ulcer, colic, heartburn Genitourinary infection, urethral pain, endometritis, cystitis, leucorrhea, syphilis, gonorrhea, malaria, dysmenorrhea, nervousness, hysteria, epilepsy, athlete’s foot, indigestion, stomach pain, gastric ulcer, colitis, cough, vomiting, hepatitis, jaundice, cirrhosis, yellow fever [16] |

| T13 | T. bursarina | Yellow wood | Australia, South Asia [17] | Unknown |

| T14 | T. calamansanai | Phillipine almond, Anarep | Philippines, Southeast Asia | Lithontriptic [18], horticultural plant [102] |

| T15 | T. calcicola | Unknown | Madagascar Rain Forest [19] | Unknown |

| T16 | T. catappa | Indian almond, umbrella tree, tropical almond | China (Guangdong, Taiwan, SE Yunnan), Australia and SE Asia, Africa, South America Tropical Coast |

Blood stasis, liver injury [20] Diarrhea, dysentery, biliary inflammation [23], dermatitis, hepatitis [106] |

| T17 | T. chebula | Black Mytrobalan, Inknut, Chebulic Myrobalan | Nepal, northern India, Myanmar, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Bangladesh, China (Yunnan), Himalayan | Digestion appetizers, vomiting, infertility, asthma, sore throat, vomiting, urticaria, diarrhea, dysentery, bleeding, ulcers, gout, bladder disease [21] |

| T18 | T. chebula var. tomentella | Weimaohezi (variant) | China (western Yunnan), Myanmar | Unknown |

| T19 | T. citrina | Manahei, Yellow myrobalan | India, Bangladesh [22] | Dysmenorrhea, bleeding, heart disease, dysentery, constipation [22] |

| T20 | T. elliptica | Indian laurel | SE Asia, India, Bangladesh, Laos, Myanmar, Nepal, Thailand, Cambodia, Vietnam |

Wine, palm sugar Ulcers, fractures, bleeding, bronchitis, diarrhea [23] |

| T21 | T. franchetii | Dianlanren | SW China [24] | Unknown |

| T22 | T. franchetii var. membranifolia | Baoyedianlanren (variant) | China [western Guangxi (Longlin), central to SE Yunnan] | Unknown |

| T23 | T. franchetii var. glabra | Guang yedianlanren (variant) | China (Sichuan and Yunnan Jinsha River Basin) | Unknown |

| T24 | T. ferdinandiana | Gubinge, Bbillygoat plum, Kakadu plum, green plum, salty plum, murunga, mador | Australia [25] | Dietary supplements, skin care [25] |

| T25 | T. glaucescens | Unknown | Nigeria [26] |

Amenorrhea, vaginal infections, syphilis, sores, neurological disorders Anti-plasma, antiparasitic, antiviral, antimicrobial [26, 27] |

| T26 | T. hainanensis | Ji zhenmu, Hainan lanren | China (Hainan) | Antioxidant [28] |

| T27 | T. intricate | Cuozhilanren | China (NW Yunnan and SW Sichuan) | Unknown |

| T28 | T. ivorensis | Idigbo, Black Afara, Shingle Wood, Brimstone Wood, Blackbark | Cameroon, West Africa, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Nigeria, Sierra Leone, Ghana |

Rheumatism, gastroenteritis, psychotic analgesics [29] Syphilis, burns and bruises [30] |

| T29 | T. kaernbachii | Okari Nut | Solomon Islands, Papua New Guinea | α-Glucosidase inhibitor activity [31] |

| T30 | T. kaiserana | Unknown | Tanzania | Diarrhea, gonorrhea vomiting [44] |

| T31 | T. laxiflora | Unknown | West Africa, Sudan Savannah |

Malaria, cough [32] Fumigant, rheumatic pain, smoothen skin, body relaxation [33] |

| T32 | T. macroptera | Bayankada | Tropical (West Africa) | Wound, hepatitis, malaria, fever, cough, diarrhea, tuberculosis, skin diseases [34] |

| T33 | T. mantaly | Unknown | Africa, Madagascar | Dysentery |

| T34 | T. mollis | Bush willow | Africa | Diarrhea, gonorrhea, malaria, AIDS adjuvant therapy [35] |

| T35 | T. muelleri | Ketapang kencana | Indonesia, SE Asia, South Asia | Antibacterial [36], antioxidants [37] |

| T36 | T. myriocarpa | Qianguolanren | China [Guangxi (Longjin), Yunnan (central to the south), and Tibet (Medog)], northern Vietnam, Thailand, Laos, northern Myanmar, Malaysia, NE India, Sikkim | Antioxidant, liver protection [38] |

| T37 | T. myriocarpa var. hirsuta | Yingmaoqianguolanren (variant) | Yunnan, China; Thailand | Unknown |

| T38 | T. oblongata | Rose wood, yellow wood | Central Queensland [39] | Unknown [39] |

| T39 | T. paniculata | Vellamaruth | India | Cholera, mumps, menstrual disorders, cough, bronchitis, heart failure, hepatitis, diabetes, obesity [40] |

| T40 | T. parviflora | Tropical almond, umbrella tree, Indian almond | Sri Lanka and India [41] | Diarrhea [41] |

| T41 | T. prunioides | Hareri, Sterkbos, Purple pod Terminalia, Mwangati | Southern Africa | Postnatal abdominal pain |

| T42 | T. sambesiaca | Unknown | Southern Africa |

Cancer, gastric ulcer, appendicitis Bloody diarrhea [45] |

| T43 | T. schimperiana | Idi odan | Africa, Sierra Leone, Guinea, Uganda, Ethiopia | Local burns, bronchitis, dysentery [42] |

| T44 | T. sericea | Monakanakane, Mososo, Mogonono, Amangwe, Vaalboom, Mangwe, Silver clutter-leaf | Northern South Africa, Botswana (except central Kalahari), southern Mozambique, Tanzania, Namibia, Zimbabwe, Northern Democratic Republic of Congo, tropical Africa [43] |

Diarrhea, sexually transmitted infections, rash, tuberculosis [43] Fever, high blood pressure [44] |

| T45 | T. spinosa | Musosahwai, spiny cluster leaf, Kasansa | Southern Africa |

Malaria, fever [46] Epilepsy, poisoning [47] |

| T46 | T. stenostachya | Rosette leaf Terminalia | Southern Africa | Epilepsy, poisoning [47] |

| T47 | T. stuhlmannii | Unknown | Acacia [48] | Unknown |

| T48 | T. superba | Limba | Tropical Western Africa | Gastroenteritis, diabetes, female infertility, abdominal pain, bacteria/fungi/viral infections [49], diabetes remedies, anesthetic, hepatitis [50] |

| T49 | T. triflora | Lanza, lanza amarilla, amarillo derío, paloamarillo |

Tropical (South America) Northern and Northwest Argentina [149] |

Making posts, furniture, weapons, fuel [149] |

| T50 | T. tropophylla | Unknown | Madagascan [51] | Unknown |

SE southeastern, NE northeastern, SW southwestern, NW northwestern

Terminalia species are broadly used in many aspects. Some are employed as drugs, while others can provide high quality wood, tannin or dyes. For example, fruits of T. ferdinandiana, a species largely distributed in Australia, are rich in vitamin C, and possess strong antioxidant activity [25]. T. bellirica and T. chebula are not only recorded in every version of Chinese pharmacopoeia, but are also the important and most commonly applied drugs in Han, Tibetan, Mongolian and many other folk medicinal systems in India, Burma, Thailand, Malaysia, Vietnam and other southeast asian countries. T. catappa is a commonly used medicinal plant for liver protection in China [20].

Chemical Composition

Since 1930s, the chemical compositions of the genus Terminalia have been vastly studied. T. arjuna, T. bellirica, T. catappa and T. chebula, having been frequently used in the Ayurvedic, Chinese and Tibetan medicines, attracted scholars’ attention. To date, 368 compounds, largely terpenoids (1–104), tannins (105–196), flavonoids (197–241), lignans (242–265), phenols and glycosides (268–318) were reported from the genus (Tables 2, 3).

Table 2.

Chemical constituents isolated from the genus Terminalia and the studied plant organs

| No. | Compounds | Plants | Organs | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Triterpenes (86) | ||||

| 1 | 2α,3β,19α-Trihydroxyolean-12-en-20-oic acid 3-O-β-d-galactosyl-(1 → 3)-β-d-glucoside | T1 | R | [3] |

| 2 | 2α,3β,19α-Trihydroxyolean-12-en-28-oic acid methylester 3β-O-rutinoside | T1 | R | [53] |

| 3 | 2α,3β,19β,23-Tetrahydroxyolean-12-en-28-oic acid 3β-O-β-d-galactosyl-(1 → 3)-β-d-glucoside-28-O-β-d-glucoside | T1 | R | [52] |

| 4 | 3-Acetylmaslinic acid | T1 | RB | [54] |

| 5 | Arjunic acid |

T1 T4 T17 T25 T28 T32 T44 |

B SB, F F SB B B R |

[146] [130] [132] [145] [133] |

| 6 | Arjunoside I | T4 | SB | [61] |

| 7 | Arjunoside II | T4 | SB | [61] |

| 8 | Arjunoside III | T4 | R | [62, 63] |

| 9 | Arjunoside IV | T4 | R | [62, 63] |

| 10 | Arjunetin |

T1 T4 T8, T16, T17, T20, T39 |

B B, L, S, R, F B, L, S, R, F |

[23] |

| 11 | Oleanolic acid |

T1 T9 T4, T16, T20 T8, T17 T39 T28 T36 |

H L B, L, S, R, F B, L, S, R L, S, R, F B B |

[56] [97] [23] [23] [23] [132] [140] |

| 12 | Ursolic Acid |

T4, T16, T20 T8, T17 T39 |

B, L, S, R, F L, S, R B, L, S, F |

[23] [23] [23] |

| 13 | Maslinic acid |

T1 T9 T17 T36 |

H L F B |

[56] [97] [140] |

| 14 | 2α,3α,24-Trihydroxyolean-11,13(18)-dien-28-oic acid | T33 | SB | [158] |

| 15 | Terminoside A | T4 | B | [58] |

| 16 | Arjungenin |

T4 T25 T12 T8, T16, T20, T39 T17 T25 T28 T32 T33 T44 |

SB,L,R,F R B B, L, S, R, F B, L, S, R, F R, SB B B SB RB |

[60] [99] [23] [132] [145] [158] |

| 17 | Hypatic acid | T25 | R | [69] |

| 18 | Arjunglucoside I |

T4 T17 T50 T32 |

B, R F R B |

[146] [72] [145] |

| 19 | Sericoside |

T4 T25 T28 T44 T32 T50 |

B SB B R, L, SB B R |

[71] [130] [145] [72] |

| 20 | Crataegioside |

T4 T17 |

B F |

[75] [146] |

| 21 | 23-O-neochebuloylarjungenin 28-O-β-d-glycosyl ester | T17 | F | [146] |

| 22 | 23-O-4′-epi-neochebuloylarjungenin | T17 | F | [146] |

| 23 | 23-O-galloylarjunic acid |

T39 T32 |

B B |

[144] [145] |

| T17 | F | [146] | ||

| 24 | Quercotriterpenoside I | T32 | B | [145] |

| T17 | F | [146] | ||

| 25 | Sericic acid |

T28 T32 T44 |

B B R |

[132] [145] [150] |

| 26 | 24-Deoxy-sericoside | T32 | B | [138] |

| 27 | Arjunolic acid |

T1 T4 T7 T9 T8 T16, T17, T20, T39 T34 T36 |

B, H B, H, L, S, R, F RB L B, L, S, R B, L, S, R, F L B |

[97] [23] [23] [35] [140] |

| 28 | Terminolic acid |

T1 T17 T7, T16, T31 T25 T32 |

H F H H, Rl H, B |

[56] [146] [128] [128] |

| 29 | Arjunglucoside II |

T4 T17 |

B F |

[146] |

| 30 | 23-O-galloylarjunolic acid | T17 | F | [146] |

| 31 | 23-O-galloylarjunolic acid 28-O-β-d-glucosyl ester | T17 | F | [146] |

| 32 | 23-O-galloylterminolic acid 28-O-β-d-glucosyl ester | T17 | F | [146] |

| 33 | Arjunolitin | T4 | SB | [80] |

| 34 | Terminolitin | T4 | F | [80] |

| 35 | Arjunglucoside III | T4 | B | [74] |

| 36 | Methyl oleanate | T4 | R, F | [80, 124] |

| 37 | Olean-3α,22β-diol-12 en-28-oic acid 3-O-β-d-glucosyl-(1 → 4)-β-d-glucoside | T4 | B | [81, 84] |

| 38 | Arjunetoside | T4 | R, SB | [82] |

| 39 | Olean 3β,6β,22α-triol-12en-28-oic acid-3-O-β-d-glucosyl-(1 → 4)-β-d-glucoside | T4 | B | [84] |

| 40 | 2α,19α,Dihydroxy-3-oxo-olean-12-en-28-oic acid-28-O-β-d-glucoside | T4 | R | [85] |

| 41 | Ivorengenin A (2α,19α,24-trihydroxy-3-oxoolean-12-en-28-oic acid) | T28 | B | [132] |

| 42 | Chebuloside I | T17 | F | [115] |

| 43 | Chebuloside II |

T17 T32 |

F B |

[115] [138] |

| 44 | Arjunglucoside |

T17 T44 T33 |

F R, SB SB |

[115] [133] [158] |

| 45 | Glaucescic acid (2α,3α,6α,23-tetrahydroxyolean-2-en-28-oic acid) | T25 | R | [69] |

| 46 | Glaucinoic acid (2α,3β,19α,24-tetrahydroxyolean-12-en-30-oic acid) | T25 | SB | [130] |

| 47 | Termiarjunoside I (olean-1α,3β,9α,22α-tetraol-12-en-28-oic acid-3-β-d-glucoside) | T4 | SB | [156] |

| 48 | Termiarjunoside II (olean-3α,5α,25-triol-12-en-23,28-dioic acid-3α-d-glucoside) | T4 | SB | [156] |

| 49 | β-Amyrin |

T25 T36 |

SB B |

[129] [140] |

| 50 | Ivorenoside A | T28 | B | [131] |

| 51 | Ivorenoside B | T28 | B | [131] |

| 52 | Ivorenoside C | T28 | B | [131] |

| 53 | Ivorengenin B (4-oxo-19α-hydroxy-3,24-dinor-2,4-secoolean-12-ene-2,28-dioic acid) | T28 | B | [132] |

| 54 | 1α,3β-Hydroxyimberbic acid 23-O-α-l-4-acetylrhamnoside | T47 | SB | [48] |

| 55 | 1α,3β,3,23-Trihydroxy-olean-12-en-29-oate-23-O-α-[4-acetoxyrhamnosyl]-29-α-rhamnoside | T47 | SB | [48] |

| 56 | 2α,3β-Dihydroxyolean-12-en-28-oic acid 28-O-β-d-glucoside | T48 | SB | [49] |

| 57 | 2α,3β,21β-Trihydroxyolean-12-en-28-oic acid 28-O-β-d-glucoside | T48 | SB | [49] |

| 58 | 2α,3β,29-Trihydroxyolean-12-en-28-oic acid 28-O-β-d-glucoside | T48 | SB | [49] |

| 59 | 2α,3β,23,27-Tetrahydroxyolean-12-en-28-oic acid 28-O-β-d-glucoside | T48 | SB | [49] |

| 60 | Terminaliaside A ((3β,21β,22α)-3-O-(3′-O-angeloylglucosyl)-21,22-dihydroxy-28-O-sophorosyl-16-oxoolean-12-ene) | T50 | R | [72] |

| 61 | 2, 3, 23-Trihydroxylolean-12-ene | T7 | RB | [91] |

| 62 | 2α,3β,23-Trihydroxylolean-12-en-28-oic acid | T48 | SB | [49] |

| 63 | 23-O-galloylpinfaenoic acid 28-O-β-d-glucosyl ester | T17 | F | [146] |

| 64 | Pinfaenoic acid 28-O-β-d-glucosyl ester |

T4 T17 |

B F |

[76] [146] |

| 65 | 2α,3β-Dihydroxyurs-12,18-dien-28-oic acid 28-O-β-d-glucosyl ester | T4 | B | [76] |

| 66 | Quadranoside VIII | T4 | B | [76] |

| 67 | Kajiichigoside F1 | T4 | B | [76] |

| 68 | 2α,3β,23Trihydroxyurs-12,19-dien-28-oic acid 28-O-β-d-glucosyl ester | T4 | B | [76] |

| 69 | α-Amyrin | T7 | RB | [91] |

| 70 | 2α,3β,23-Trihydroxy-urs-12-en-28-oic acid | T34 | L | [35] |

| 71 | 2α-Hydroxyursolic acid |

T34 T17 |

L F |

[35] |

| 72 | Ursolic acid | T11 | L | [35] |

| 73 | 2α-Hydroxymicromeric acid | T17 | F | [115, 116] |

| 74 | Betulinic acid |

T1 T11 T12 T4, T16, T17, T20, T39 T8 T25 T28 T36 |

B L B B, L, S, R, F B, L, S, R SB B B |

[55] [35] [99] [23] [23] [129] [132] [140] |

| 75 | Terminic acid | T4 | R, H | [57, 62] |

| 76 | Lupeol |

T4 T25 T44 |

SB SB SB, R |

[80] [129] [43] |

| 77 | Monogynol A | T12 | B | [99] |

| 78 | Triterpenes |

T25 T44 |

SB R, SB |

[129] [133] |

| 79 | Friedelin |

T4 T7 T25 T34 |

F RB SB SB |

[83] [93] [35] |

| 80 | Maslinic lactone | T1 | H | [56] |

| 81 | Terminalin A | T25 | SB | [129] |

| 82 | Arjunaside A | T4 | B | [68] |

| 83 | Arjunaside B | T4 | B | [68] |

| 84 | Arjunaside C | T4 | B | [68] |

| 85 | Arjunaside D | T4 | B | [68] |

| 86 | Arjunaside E | T4 | B | [68] |

| Mono- (14) and sesqui- (4) terpendoids | ||||

| 87 | α-Pinene | T9 | L | [13] |

| 88 | Sabinene | T9 | L | [13] |

| 89 | Myrcene | T9 | L | [13] |

| 90 | β-Pinene | T9 | L | [13] |

| 91 | 1,8-Cineole | T9 | L | [13] |

| 92 | Linalool | T9 | L | [13] |

| 93 | Menthone | T9 | L | [13] |

| 94 | γ-Terpineol | T9 | L | [13] |

| 95 | α-Terpineol | T9 | L | [13] |

| 96 | Limonene | T9 | L | [13] |

| 97 | Neral | T9 | L | [13] |

| 98 | Geraniol | T9 | L | [13] |

| 99 | Thymol | T9 | L | [13] |

| 100 | Isomenthone | T9 | L | [13] |

| 101 | β-Copaene | T9 | L | [13] |

| 102 | β-Caryophyllene | T9 | L | [13] |

| 103 | Caryophyllene | T9 | L | [13] |

| 104 | α-Humulene | T9 | L | [13] |

| Hydrolysable (89) and condensed tannins (2) | ||||

| 105 | 1,2,3,6-Tetra-O-galloyl-β-d-glucose | T17 | F | [159] |

| 106 | Gallotannin (1,2,3,4,6 penta galloyl glucose) |

T4 T17 T19 T30 T45, T46 |

SB, L F F R L |

[86] [120] [133] [133] |

| 107 | 1,3,4,6-Tetra-O-galloyl-β-d-glucose | T17 | F | [159] |

| 108 | 2,3,4,6-Tetra-O-galloyl-d-glucose |

T3 T4 |

F SB, L |

[154] [86] |

| 109 | 1,2,6-Tri-O-galloyl-β-d-glucose | T31 | R | [101] |

| 110 | Sanguiin H-1 | T14 | L | [102] |

| 111 | 1,6-Di-O-galloyl-β-d-glucose |

T3 T17 T40 |

F F B |

[154] [41] |

| 112 | 1,3,6-Tri-O-galloyl-β-d-glucose |

T3 T40 T19 T17 |

F B F F |

[154] [41] [120] [159] |

| 113 | Methyl 3,6-di-O-galloyl-β-d-glucoside | T40 | B | [41] |

| 114 | 4,6 Bis hexahydroxydiphenyl-1-galloyl-glucose | T4 | SB, L | [86] |

| 115 | Sanguiin H-4 | T14 | L | [18, 102] |

| 116 | Corilagin |

T3 T31 T16 T17 T19 T24 T32 |

F R L, B F F F L |

[154] [101] [120] [126] |

| 117 | Tercatain |

T16 T17 |

B, L F |

[159] |

| 118 | 1,3-Di-O-galloyl-β-d-glucose | T17 | F | [159] |

| 119 | 2,3-O-(S)-HHDP-d-glucose |

T3 T14 T4 T16 T40 T36 |

F L B B, L B L |

[154] [102] [104] [41] [38] |

| 120 | 2,3-(S)-HHDP-6-O-galloyl-d-glucose |

T3 T4 T40 T32 |

F B B B |

[154] [104] [41] [137] |

| 121 | 3,6-Di-O-galloyl-d-glucose |

T3 T40 T17 |

F B F |

[154] [41] [159] |

| 122 | 3,4-Di-O-galloyl-d-glucose | T3 | F | [154] |

| 123 | 6-O-galloyl-d-glucose | T17 | F | [159] |

| 124 | 3,4,6-Tri-O-galloyl-d-glucose | T17 | F | [159] |

| 125 | Tellimagrandin I |

T35 T17 |

L F |

[139] [159] |

| 126 | Gemin D | T17 | F | [159] |

| 127 | Arjunin |

T4 T17 |

L F |

[115] |

| 128 | Punicalin |

T3 T4 T14 T40 T16 T17 T28 T49 |

F L, B L B L L, F SB L |

[154] [102] [41] [29] [149] |

| 129 | Casuarinin |

T4 T16 T17 |

L, B B F |

[41] |

| 130 | Casuariin | T4 | B | [90, 104] |

| 131 | Terchebulin |

T3 T4 T7 T12 T17 T31 |

F B SB B F W |

[154] [92] [100] [21] [134] |

| 132 | Castalagin |

T4 T16, T40 |

B B |

[41] |

| 133 | Grandinin | T16, T40 | B | [41] |

| 134 | Castalin | T16, T40 | B | [41] |

| 135 | α/β-Punicalagin |

T3 T7 T4 T11 T12 T31 T14 T16 T17 T40 T19 T28 T32 T35 T36 T38 |

F SB B L B R L B L, F B F SB B L L L |

[154] [92] [104] [35] [100] [101] [41] [41] [120] [29] [137] [139] [38] [39] |

| 136 | 1-α-O-galloylpunicalagin | T14 | L | [18, 102, 103] |

| 137 | 6′-O-methyl neochebulagate | T17 | F | [159] |

| 138 | Dimethyl neochebulagate | T17 | F | [159] |

| 139 | Neochebulagic acid | T17 | F | [159] |

| 140 | Dimethyl 4′-epi-neochebulagate | T17 | F | [159] |

| 141 | Methyl chebulagate | T17 | F | [159] |

| 142 | Chebulagic acid |

T3 T4 T8 T17 T16 T39 T20 T19 T32 T35 |

F B, L, S F, B, L, S F, B, L, S, R F, B, L, S, R F, B, L, S, R F, B, L, R F L L |

[154] [23] [23] [23] [23] [120] [139] |

| 143 | Chebulinic acid |

T3 T4, T8, T16, T20, T39 T17 T32 T35 |

F F, B, L, S, R F, B, L, S, R L L |

[154] [23] [23] |

| 144 | Chebulanin |

T34, T11 T17 |

L F |

[35] |

| 145 | 1,3-Di-O-galloyl-2,4-chebuloyl-β-d-glucose | T3 | F | [154] |

| 146 | 1,6-Di-O-galloyl-2,4-chebuloyl-β-d-glucose | T17 | F | [155, 159] |

| 147 | 2-O-galloylpunicalin |

T14 T40 T32 T49 |

L B B L |

[18] [41] [137] [149] |

| 148 | 1-Desgalloyleugeniin |

T14 T16 |

L L |

[102] [107] |

| 149 | Eugeniin | T14 | L | [102] |

| 150 | Rugosin A | T14 | L | [102] |

| 151 | 1(α)-O-galloylpedunculagin | T14 | L | [102] |

| 152 | Praecoxin A | T14 | L | [102] |

| 153 | Calamansanin | T14 | L | [102] |

| 154 | Calamanin A | T14 | L | [102] |

| 155 | Calamanin B | T14 | L | [102] |

| 156 | Calamanin C | T14 | L | [102] |

| 157 | Terflavin C |

T4 T14 T17 |

B L L |

[104] [103] [21] |

| 158 | Terflavin A |

T16 T17 T32 |

L F B |

[21] [137] |

| 159 | Terflavin B |

T16 T17 T32 |

L L, F B |

[137] |

| 160 | 3-Methoxy-4-hydroxyphenol-1-O-β-d-(6′-O-galloyl)-glucoside | T16 | B | [41] |

| 161 | 3,5-Di-methoxy-4-hydroxyphenol-1-O-β-d-(6′-O-galloyl)-glucoside | T16 | B | [41] |

| 162 | Acutissimin A | T16 | B | [41] |

| 163 | Eugenigrandin A | T16 | B | [41] |

| 164 | Catappanin A | T16 | B | [41] |

| 165 | Castamollinin | T40 | B | [41] |

| 166 | Tergallagin | T16 | L | [106, 107] |

| 167 | Geraniin | T16 | L | [107] |

| 168 | Granatin B | T16 | L | [107] |

| 169 | Gallotannic (tannic acid) |

T17,T8 T38 |

F L |

[113] [141] |

| 170 | Chebulin | T17 | F | [113, 114] |

| 171 | Terchebin | T17 | F | [113, 119] |

| 172 | Neochebulinic acid |

T3 T17 |

F F |

[154] |

| 173 | Chebumeinin A | T17 | F | [118] |

| 174 | Chebumeinin B | T17 | F | [118] |

| 175 | Isoterchebulin | T32 | B | [137] |

| 176 | Punicacortein C |

T3 T32 T17 |

F B F |

[154] [137] [159] |

| 177 | Punicacortein D | T17 | F | [159] |

| 178 | 4,6-O-Isoterchebuloyl-d-glucose | T32 | B | [137] |

| 179 | Trigalloyl-β-d-glucose | T35 | L | [139] |

| 180 | Tetragalloyl-β-d-glucose | T35 | L | [139] |

| 181 | Pentagalloyl-β-d-glucose | T35 | L | [139] |

| 182 | 1,2,3-Tri-O-galloyl-6-O-cinnamoyl-β-d-glucose | T17 | F | [159] |

| 183 | 1,2,3,6-Tetra-O-galloyl-4-O-cinnamoyl-β-d-glucose | T17 | F | [159] |

| 184 | 1,6-Di-O-galloyl-2-O-cinnamoyl-β-d-glucose | T17 | F | [159] |

| 185 | 1,2-Di-O-galloyl-6-O-cinnamoyl-β-d-glucose | T17 | F | [159] |

| 186 | 4-O-(2′′, 4′′-di-O-galloyl-α-l-rhamnosyl) ellagic acid | T17 | F | [159] |

| 187 | 4-O-(4′′-O-galloyl-α-l-rhamnosyl) ellagic acid | T17 | F | [159] |

| 188 | 4-O-(3′′, 4′′-di-O-galloyl-α-l-rhamnosyl) ellagic acid | T17 | F | [159] |

| 189 | 1′-O-methyl neochebulanin | T17 | F | [159] |

| 190 | Dimethyl neochebulinate | T17 | F | [159] |

| 191 | Phyllanemblinin E | T17 | F | [159] |

| 192 | 1′-O-methyl neochebulinate | T17 | F | [159] |

| 193 | Phyllanemblinin F | T17 | F | [159] |

| 194 | Procyanidin B-1 | T16 | B | [41] |

| 195 | 3′-O-galloyl procyanidin B-2 | T16 | B | [41] |

| Flavonoids (45) | ||||

| 196 | 5,7,2′-Tri-O-methylflavanone4′-O-α-l-rhamnosyl-(1 → 4)-β-d-glucoside | T1 | R | [52] |

| 197 | Arjunone | T4 | B, F | [83, 89] |

| 198 | 8-Methyl-5,7,2′,4′-tetramethoxy-flavanone |

T1 T39 |

R B |

[53] [144] |

| 199 | Naringin |

T4 T8 T17 T39 T20 |

L, S, F B, F L, R, F R, F B, L, S, R |

[23] [23] [23] [23] [23] |

| 200 | Eriodictyol |

T4, T8, T17, T20, T39 T16 |

B, L, S, R, F L, S, R, F |

[23] [23] |

| 201 | Hesperitin | T24 | F | [122] |

| 202 | Flavanone | T24 | F | [122] |

| 203 | Arjunolone (6,4-dihydroxy-7-methoxy flavone) | T4 | SB | [64] |

| 204 | Bicalein (5,6,7-trihydroxy flavone) | T4 | SB | [64] |

| 205 | Scutellarein |

T4 T8, T17, T20 T16 T39 |

B, R B, L, S, R, F L, F B, L, R, F |

[23] [23] [23] [23] |

| 206 | Luteolin |

T4 T8, T20 T17 T16 T39 T24 |

B, L L, S R, L L L, S, F F |

[23] [23] [23] [23] [122] |

| 207 | Apigenin |

T4 T8, T16, T17, T20, T39 |

B, L, S, R, F B, L, S, R, F |

[23] |

| 208 | Isoorientin |

T11 T4, T8, T17, T16, T20, T39 T35 T36 |

L B, L, S, R, F L L |

[35] [23] [139] [38] |

| 209 | Orientin |

T11 T4 T8 T17 T16 T39 T20 T35 T36 |

L L, F B, S B, L, S, R, F L, R, F B, S, F L, S, F, R L L |

[35] [23] [23] [23] [23] [23] [23] [139] [38] |

| 210 | Isovitexin |

T11 T4 T17 T16 T39 T20 T35 T36 |

L L, F L, R, F L S, F L, S, F L L |

[35] [23] [23] [23] [23] [139] [38] |

| 211 | Apigenin-6-C-(2″-O-galloyl)-β-d-glucoside | T16 | L | [105] |

| 212 | Apigenin-8-C-(2″-O-galloyl)-β-d-glucoside |

T16 T34 |

L L |

[105] [35] |

| 213 | Vitexin |

T4, T17, T20 T8 T16 T39 T35 T36 |

B, L, S, R, F B, L, S, R L, S, R, F B, L, S, F L L |

[23] [23] [23] [23] [139] [38] |

| 214 | Amentoflavone |

T8 T17 T20 |

L, S L, R, F L |

[23] [23] [23] |

| 215 | Neosaponarin | T36 | L | [38] |

| 216 | (−)-Epicatechin | T4 | B | [76] |

| 217 | Epicatechin |

T4, T8, T17, T20, T39 T16 T34 |

B, L, S, R, F L, S, R, F SB |

[23] [23] [35] |

| 218 | Catechin |

T34 T11 T4, T8, T16, T17, T20, T39 T44 |

SB L B, L, S, R, F R |

[35] [35] [23] [133] |

| 219 | Catechin–epicatechin | T44 | R | [43] |

| 220 | Catechin–epigallocatechin | T44 | R | [43] |

| 221 | Epigallocatechin | T34 | SB | [35] |

| 222 | (−)-Epicatechin-3-O-gallate | T16 | B | [41] |

| 223 | (−)-Epigallocatechin-3-O-gallate | T16 | B | [41] |

| 224 | Flavanol | T24 | F | [122] |

| 225 | Gallocatechin |

T34 T24 |

SB F |

[35] [126] |

| 226 | Quercetin |

T4 T8 T17 T16 T39 T20 T24 T49 |

B, L, R R S, R, F L, S, F L, B F F L |

[23] [23] [23] [23] [23] [124] [124] |

| 227 | Kaempferol |

T4 T8 T16, T17 T20, T39 T24 |

B, L, S, R, F B, L, S, F B, L, S, R, F L, S, R, F F |

[23] [23] [23] [122] |

| 228 | Kaempferol-3-O-β-d-rutinoside |

T4, T8, T17 T16 T39 T20 T36 |

B, L, S, R, F L, S, F L, R, F L, S, R L |

[23] [23] [23] [23] [38] |

| 229 | Afzelin (kaempferol 3-O-rhamnoside) | T49 | L | [124] |

| 230 | Rutin |

T4, T16 T8 T17, T39 T20 T32 T36 |

B, L, S, F L, S B, L, S, R, F L, S, F L L |

[23] [23] [23] [23] [38] |

| 231 | Narcissin | T32 | L | [135, 136] |

| 232 | Quercetin-3,4′-di-O-glucoside |

T4 T8 T16, T17, T20, T39 |

B, L, S, F B, S, F B, L, S, R, F |

[23] [23] [23] |

| 233 | Quercetin-7-O-rhamnoside | T4 | F | [80] |

| 234 | 2-O-β-glucosyloxy-4,6,2′,4′-tetramethoxychalcone | T1 | R | [53] |

| 235 | Cerasidin | T4 | F | [80] |

| 236 | Genistein |

T4 T8, T16, T17, T20, T39 |

B, L, S, R, F B, L, S, R, F |

[23] |

| 237 | Cyaniding | T4 | B | [66] |

| 238 | Pelargonidin | T4 | B | [66] |

| 239 | Leucocyanidin | T4 | B | [80] |

| 240 | 7-Hydroxy-3′,4-(methylenedioxy)flavan | T8 | FR | [12] |

| Lignan (27) | ||||

| 241 | Termilignan |

T8 T39 |

FR B |

[12] [144] |

| 242 | Anolignan B |

T8 T44 |

FR R |

[12] |

| 243 | Thannilignan | T8 | FR | [12] |

| 244 | Termilignan B | T44 | R | [133] |

| 245 | Ferulic acid dehydrodimer | T24 | F | [125] |

| 246 | (7S,8R,7′R,8′S)-4′-hydroxy-4-methoxy-7,7′-epoxylignan | T48 | SB | [50] |

| 247 | Meso-(rel7S,8R,7′R,8′S)-4,4′-dimethoxy-7,7′-epoxylignan | T48 | SB | [50] |

| 248 | 4′-O-cinnamoyl cleomiscosin A | T50 | R | [72] |

| 249 | Diethylstilbestrol monosulphate | T24 | F | [126] |

| 250 | Terminaloside A | T19 | L | [22] |

| 251 | Terminaloside B | T19 | L | [22] |

| 252 | Terminaloside C | T19 | L | [22] |

| 253 | Terminaloside D | T19 | L | [22] |

| 254 | Terminaloside E | T19 | L | [22] |

| 255 | Terminaloside F | T19 | L | [22] |

| 256 | Terminaloside G | T19 | L | [22] |

| 257 | Terminaloside H | T19 | L | [22] |

| 258 | Terminaloside I | T19 | L | [22] |

| 259 | Terminaloside J | T19 | L | [22] |

| 260 | Terminaloside K | T19 | L | [22] |

| 261 | 2-Epiterminaloside D | T19 | L | [22] |

| 262 | 6-Epiterminaloside K | T19 | L | [22] |

| 263 | Terminaloside L | T19 | L | [121] |

| 264 | Terminaloside M | T19 | L | [121] |

| 265 | Terminaloside N | T19 | L | [121] |

| 266 | Terminaloside O | T19 | L | [121] |

| 267 | Terminaloside P | T19 | L | [121] |

| Phenols and glycosides (52) | ||||

| 268 | Ellagic acid |

T1 T7 T10, TM, TT T12 T40 T4, T8, T20 T17 T16 T39 T24 T25 T31 T28, T32 T35 T42 T30, T44 T36, T45, T46 T48 T49 |

B SB SB B B B, L, S, R, F L, SB, R F SB, L, R, F B, L, S, R, F, H F B, R, Rl B H L, F R, SB R L SB L |

[55] [14] [100] [41] [123] [128] [133] [133] [133] [50] [124] |

| 269 | Methyl ellagic acid | T4 | B | [90] |

| 270 | 3-O-methylellagic acid | T33 | SB | [158] |

| 271 | 3,3′-Di-O-methylellagic acid |

T28 T39 T48 |

SB H,B SB |

[29] [50] |

| 272 | 3,3′-Di-O-methylellagic acid 4-mono glucoside | T39 | H | [147, 148] |

| 273 | Tetra-O-methyl ellagic acid | T39 | H | [148] |

| 274 | 3,3′-Di-O-methylellagic acid 4-O-β-d-glucosyl-(1 → 4)-β-d-glucosyl-(1 → 2)-α-l-arabinoside | T1 | R | [52] |

| 275 | 3,4,3′-Tri-O-methylflavellagic acid |

T7 T12 T24 T25 T31 T28 T32 T39 |

B B F L, B, R, Rl B SB, H H, B H |

[126] [100] [126] [127] |

| 276 | 3,3′,4-O-trimethyl-4′-O-β-d-glucosylellagic acid | T28 | SB | [29] |

| 277 | 3,3′-Di-O-methyl ellagic acid 4′-O-β-d-xyloside | T48 | SB | [50] |

| 278 | 3,4′-Di-O-methylellagic acid 3′-O-β-d-xyloside | T48 | SB | [153] |

| 279 | 4′-O-galloy-3,3′-di-O-methylellagic acid 4-O-β-d-xyloside | T48 | SB | [153] |

| 280 | Flavogallonic acid |

T7 T40 T31 T12 T36 |

SB B W R L |

[92] [41] [134] [101] [38] |

| 281 | Methyl (S)-flavogallonate | T36 | L | [38] |

| 282 | Vanillic acid 4-O-β-d-(6′-O-galloyl) glucoside | T32 | B | [138] |

| 283 | 3-O-methylellagic acid 4′-O-α-l-rhamnoside |

T4 T34 T33 |

B SB SB |

[76] [35] [158] |

| 284 | Eschweilenol C (ellagic acid 4-O-α-l-rhamnoside) |

T12 T17 |

B F |

[100] [164] |

| 285 | 3-O-methylellagic acid 4′-O-xyloside | T31 | R | [101] |

| 286 | Brevifolincarboxylic acid | T35 | L | [139] |

| T17 | F | [159] | ||

| 287 | Terflavin D | T17 | L | [21] |

| 288 | Gallic acid |

T3 T4, T8, T20, T39 T10, TM, TT T17 T16 T34 T12 T31 T40 T24 T30 T35 T36 T38 T42 T44 T45, T46 T48 T49 |

F B, L, S, R, F SB SB, F, R, L SB, F, R, L L B R, W B F R L L L R, SB R L SB L |

[154] [14] [35] [100] [41] [133] [139] [38] [141] [133] [133] [133] [50] [124] |

| 289 | Phyllemblin (ethyl gallate isomers1 progallin A) |

T4 T8 T24 T28 T36 |

B F F SB L |

[86] [126] [29] [38] |

| 290 | Monogalloyl glucose |

T3 T8 T17 T31 |

F F F R |

[154] [113] [21] [101] |

| 291 | Methyl gallate |

T14 T8 T32 T36 T48 T49 |

L F L L SB L |

[18] [113] [38] [50] [124] |

| 292 | Shikimic acid | T32 | L | [135, 136] |

| 293 | 5-O-galloyl-(−)-shikimic acid |

T3 T17 |

F F |

[118] |

| 294 | 4-O-galloyl-(−)-shikimic acid | T17 | F | [159] |

| 295 | 3,5-Di-O-galloyl-(−)-shikimic acid | T3 | F | [154] |

| 296 | Digallic acid | T17 | F | [159] |

| 297 | Ethyl gallate isomers2 | T24 | F | [126] |

| 298 | Ethyl gallate isomers3 | T24 | F | [126] |

| 299 | Dimethyl gallic acid | T35 | L | [139] |

| 300 | Chebulic acid |

T3 T17 T24 T35 |

F F F L |

[154] [139] |

| 301 | 6′-O-methyl chebulate | T17 | F | [159] |

| 302 | 7′-O-methyl chebulate | T17 | F | [159] |

| 303 | Chebulic acid trimethyl ester | T32 | L | [135, 136] |

| 304 | Terminalin | T38 | L | [39] |

| 305 | Decarboxyellagic acid | T3 | F | [154] |

| 306 | 3-O-galloyl-d-glucose | T3 | F | [154] |

| 307 | 6-O-galloyl-d-glucose |

T3 T17 |

F F |

[154] [159] |

| 308 | Vanillic acid |

T4, T8, T20, T39 T17 T16 T44 |

B, L, S, R, F B S, R, B, F R |

[23] [23] [43] |

| 309 | Benzoic acid |

T44 T24 |

R F |

[43] [122] |

| 310 | Hydrocinnamic acid | T44 | R | [43] |

| 311 | Gentisic acid | T16 | L | [108] |

| 312 | Protocatechuic acid | T4, T8, T16, T17, T20, T39 | B, L, S, R, F | [23] |

| 313 | 2,3-Di-hydroxyphenyl β-d-glucosiduronic acid | T24 | F | [125] |

| 314 | Quinic acid |

T4, T8, T16, T17, T20, T39 T24 |

B, L, S, R, F |

[23] [125] |

| 315 | p-Coumaric acid |

T17 T44 |

WP R |

[117] [43] |

| 316 | Caffeic acid |

T4, T8 T17 T16 T39 T20 T44 |

L, S L, S, R L B, L, S, R, F B R |

[23] [23] [23] [23] [23] [43] |

| 317 | Chlorogenic acid |

T4 T17 T16, T39 T20 |

L, S S, R, F, L L B |

[23] [23] [23] [23] |

| 318 | Ferulic acid |

T4 T8, T17, T20, T39 T16 |

B, L, S, F B, L, S, R, F L, S, R |

[23] [23] [23] |

| 319 | Sinapic acid |

T4, T16, T20, T39 T8 T17 |

B, L, S, R, F S, R, F B, S, R, F |

[23] [23] [23] |

| Steroids (8), polyols (9) and esters (6) | ||||

| 320 | β-Sitosterol |

T1 T4 T8 T12 T16 T48 T25 T36 T39 T44 |

B, H S, F F F B, SB H H SB B H, SB, R |

[99] [128] [128] [129] [140] |

| 321 | β-Sitosterol-3-acetate | T44 | SB, R | [43] |

| 322 | β-Sitosteryl palmitate |

T16 T25, T31 |

SB, H L,F |

[128] [128] |

| 323 | Stigmasterol 3-O-β-d-glucoside |

T4 T33 |

F SB |

[80] [158] |

| 324 | Stigmasterol |

T12 T25 T33 T44 |

B SB SB RB |

[99] [129] [158] |

| 325 | Stigma-4-ene-3-one | T44 | RB | [43] |

| 326 | 16,17-Dihydroneridienone 3O-β-d-glucosyl-(1 → 6)-O-β-d-galactoside | T4 | R | [59] |

| 327 | Cannogenol 3-O-β-d-galactosyl-(1 → 4)-O-α-l-rhamno-side | T8 | Se | [94] |

| 328 | 2-Hexanol | T9 | L | [13] |

| 329 | Octanol | T9 | L | [13] |

| 330 | Methoxycarbonyloxymethyl methylcarbonate | T24 | F | [125] |

| 331 | Ribonolactone | T24 | F | [125] |

| 332 | Apionic acid | T24 | F | [125] |

| 333 | Ascorbic acid | T24 | F | [125] |

| 334 | Gluconolactone | T24 | F | [125] |

| 335 | Glucohepatonic acid-1,4-lactone | T24 | F | [125] |

| 336 | Galacturonic acid | T44 | R | [43] |

| 337 | Geranyl formate | T9 | L | [13] |

| 338 | Citronellyl acetate | T9 | L | [13] |

| 339 | Geranyl acetate | T9 | L | [13] |

| 340 | Geranyl tiglate | T9 | L | [13] |

| 341 | Laxiflorin | T31 | RB | [127] |

| 342 | (1S,5R)-4-oxo-6,8-dioxabicyclo[3.2.1]oct-2-ene-2-carboxylic acid | T24 | F | [125] |

| Others (26) | ||||

| 343 | Glucuronic acid | T24 | F | [125] |

| 344 | Coumarin | T45 | L | [133] |

| 345 | Eujavonic acid | T24 | F | [125] |

| 346 | Purine | T24 | F | [125] |

| 347 | 5-(4-Hydroxy-2,5-dimethylphenoxy)-2,2-dimethylpentanoic acid (gemfibrozil M1) | T24 | F | [125] |

| 348 | p-Hydroxytiaprofenic acid | T24 | F | [125] |

| 349 | Cis-polyisoprene | T32 | L | [135] |

| 350 | Arachidic acid | T17 | F | [113] |

| 351 | Behenic acid | T8, T17 | F | [113] |

| 352 | Arjunaphthanoloside | T4 | SB | [87] |

| 353 | Resveratrol (3′,4,5′-trihydroxystilbene) |

T24 T44 |

F R |

[126] [43] |

| 354 | Resveratrol glucoside (piceid) |

T24 T44 |

F RB |

[126] [152] |

| 355 | Resveratrol-β-d-glucoside | T44 | RB | [152] |

| 356 | Combretastatin | T24 | F | [126] |

| 357 | Combretastatin A1 | T24 | F | [126] |

| 358 | (Z)-Stilbene | T44 | R | [133] |

| 359 | (E)-Stilbene | T44 | R | [133] |

| 360 | 3′5′-Dihydroxy-4-(2-hydroxyethoxy) resveratrol-3-O-β-rutinoside | T44 | R, RB | [43, 152] |

| 361 | Resveratrol-3-β-rutinoside glycoside | T44 | R, RB | [43, 152] |

| 362 | 1,4-Cineole | T9 | L | [13] |

| 363 | Terpinen-4-ol | T9 | L | [13] |

| 364 | Terminalianone | T12 | B | [98] |

| 365 | Termicalcicolanone A | T15 | WP | [19] |

| 366 | Termicalcicolanone B | T15 | WP | [19] |

| 367 | Mangiferin |

T4 T8 T17 T16 T39 T20 |

B, S, F B, R, F B, L, S, R, F L, R, F B, L, S, F L, S, R |

[23] [23] [23] [23] [23] [23] |

| 368 | Benzoyl-β-d-(4′ → 10″geranilanoxy)-pyranoside | T8 | F | [160] |

R root, SB stem bark, B bark, F fruit, S stem, H heartwood, RB root bark, Rl rootlet, Se seed, FR fruit rind, WP whole plant, T1–T50 plants from Table 1, TM T. manii, TT T. tomentosa

Table 3.

The numbers and main types of compounds reported from different Terminalia species

| No. | Plant | Plant organs | Numbers | Main types |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | T. alata | Roots, barks | 18 | Triterpenes |

| T3 | T. arborea | Fruits | 24 | Hydrolysable tannin |

| T4 | T. arjuna | Whole plants | 93 | Triterpenes, tannins, flavonoids |

| T7 | T. avicennioides | Barks | 10 | Triterpenes, tannins |

| T8 | T. bellirica | Fruits, barks | 45 | Triterpenes, flavonoids, lignin, simple phenols |

| T9 | T. bentzoe | Leaves | 29 | Monoterpenoids, sesquiterpenoid |

| T11 | T. brachystemma | Leaves | 8 | Flavonoids |

| T12 | T. brownii | Leaves | 13 | Triterpenes |

| T14 | T. calamansanai | Leaves | 18 | Hydrolysable tannin |

| T16 | T. catappa | Whole plants | 64 | Triterpenes, tannins, flavonoids, simple phenols |

| T17 | T. chebula | Whole plants | 120 | Triterpenes, tannins, flavonoids, simple phenols |

| T19 | T. citrina | Fruits, leaves | 23 | Lignan |

| T20 | T. elliptica | Whole plants | 36 | Flavonoids |

| T24 | T. ferdinandiana | Fruits | 35 | Flavonoids, simple phenols, polyols |

| T25 | T. glaucescens | Barks | 19 | Triterpenes |

| T28 | T. ivorensis | Barks | 18 | Triterpenes |

| T31 | T. laxiflora | Roots | 13 | Tannins |

| T32 | T. macroptera | Whole plants | 28 | Triterpenes, tannins, simple phenols |

| T33 | T. mantaly | Stem barks | 7 | Triterpenes, simple phenols |

| T34 | T. mollis | Barks | 12 | Triterpenes, flavonoids |

| T35 | T. muelleri | Leaves | 16 | Hydrolysable tannin, flavonoids, simple phenols |

| T36 | T. myriocarpa | Leaves, barks | 21 | Triterpenes, flavonoids, simple phenols |

| T39 | T. paniculata | Barks | 43 | Triterpenes, flavonoids, simple phenols |

| T40 | T. parviflora | Barks | 16 | Tannins |

| T44 | T. sericea | Roots | 32 | Triterpenes, simple phenols, other compounds |

| T48 | T. superba | Barks | 15 | Triterpenes, simple phenols |

Chemical components identified from the other 12 species, including T. bialata (T10), T. calcicola (T15), T. kaiserana (T30), T. manii (TM), T. macroptera (T32), T. oblongata (T38), T. sambesiaca (T42), T. spinosa (T45), T. stenostachya (T46), T. stuhlmannii (T47), T. triflora (T49), T. tropophylla (T50) were less than 6 compounds

Terpenoids

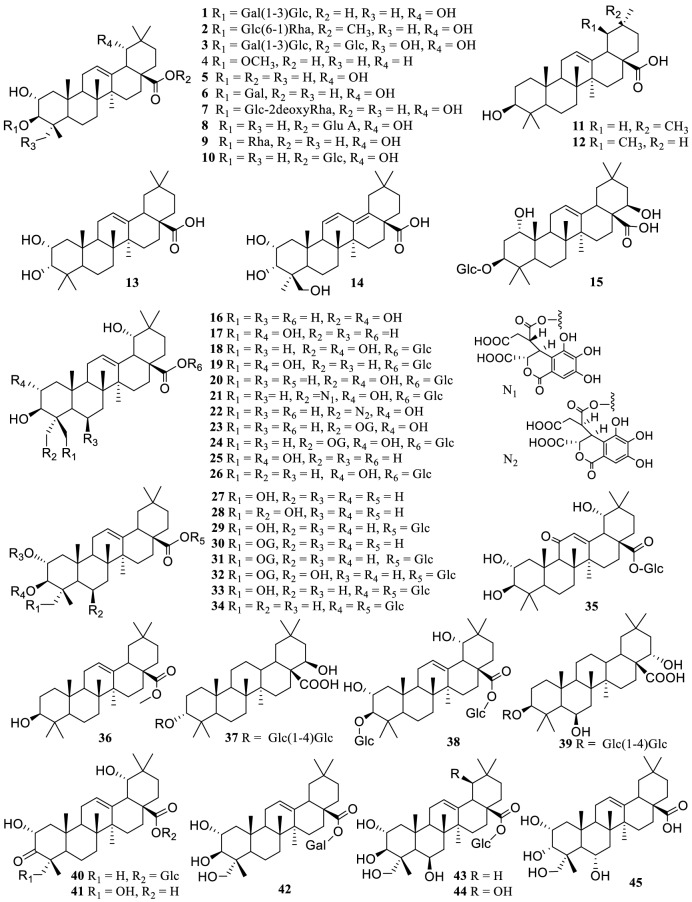

So far, 104 terpenoids (Fig. 1) including 86 triterpenes (1–86), 14 monoterpenes (87–100), 4 sesquiterpenes (101–104) have been reported from the genus Terminalia. The triterpenoids are mainly oleanane, ursane and lupine types, and their glycosides. Particularly, Atta-ur-Rahman et al. isolated a new seco-triterpene terminalin A (81) possessing a novel rearranged seco-glutinane structure with a pyran ring-A and an isopropanol moiety from the stem barks of T. glaucescens [129]. Ponou et al. found two dimeric triterpenoid glucosides, ivorenosides A and B (49–50) possessing an unusual skeleton [131], and two new oleanane type triterpenes, 3-oxo-type ivorengenin A (41) and 3,24-dinor-2,4-secooleanane-type ivorengenin B (53) from the barks of T. ivorensis [132]. Compounds 41, 49 and 53 showed significant anticancer activities. Wang et al. isolated five new 18,19-secooleanane type triterpene glycosyl esters, namely arjunasides A–E (82–86) from the MeOH extract of T. arjuna’s barks, TaBs [68]. Moreover, five ursane type triterpene glucosyl esters (64–68) were also obtained for the first time [76]. From the fruits of T. chebula, 23-O-neochebuloylarjungenin 28-O-β-d-glycosyl ester (21) and 23-O-4′-epi-neochebuloylarjungenin (22) with novel substituents at C-23 were reported, in addition to compounds 23–24, 30–32 and 63, whose C-23 substituents were gallate. Compounds 30 and 31 had strong hypoglycemic effect [146]. Furthermore, compound 40 was obtained from the barks of T. arjuna [85], while friedelin (79) with 3-oxo moiety was reported from the fruits of T. arjuna [83], the root barks of T. avicennioides [93], and the stem barks of T. glaucescens [130] and T. mollis [35].

Fig. 1.

The structures of terpenoids 1–104

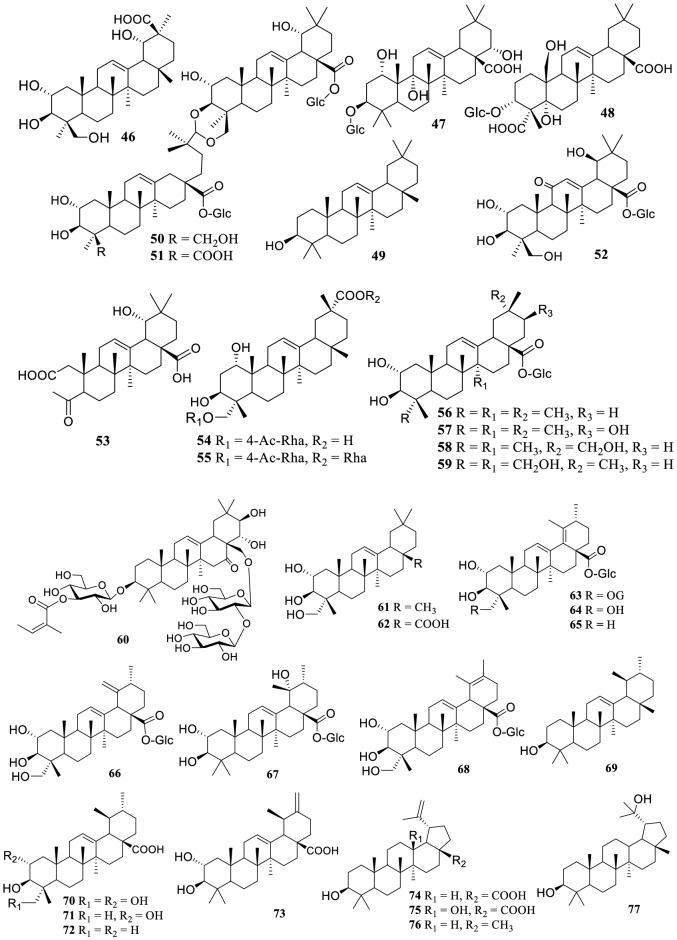

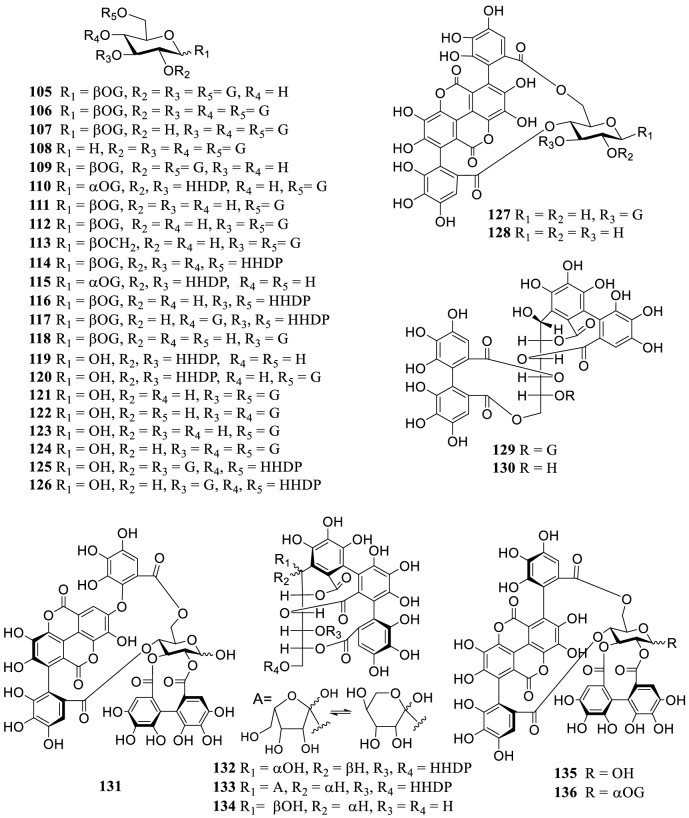

Tannins

As the main secondary metabolites, 91 tannins (105–195) were reported from the genus Terminalia (Fig. 2), including ellagitannins, gallotannins, dimeric, and trimeric tannins. Four cinnamoyl-containing gallotannins (182–185) were discovered firstly from the fruits of T. chebula, and 1,2,3,6-tetra-O-galloyl-4-O-cinnamoyl-β-d-glucose (183) and 4-O-(2″,4″-di-O-galloyl-α-l-rhamnosyl) ellagic acid (186) showed significant inhibitory activity on α-glucosidase with IC50 values of 2.9 and 6.4 μM, respectively [159].

Fig. 2.

The structures of tannins 105–195

Tannins possess not only liver and kidney protection properties, but also anti-diarrhea, anticancer, antibacterial and hypoglycemic activities [133]. However, a condensed tannin terminalin (186) from T. oblongata was reported to have severe hepatorenal toxicity and even caused renal necrosis [39].

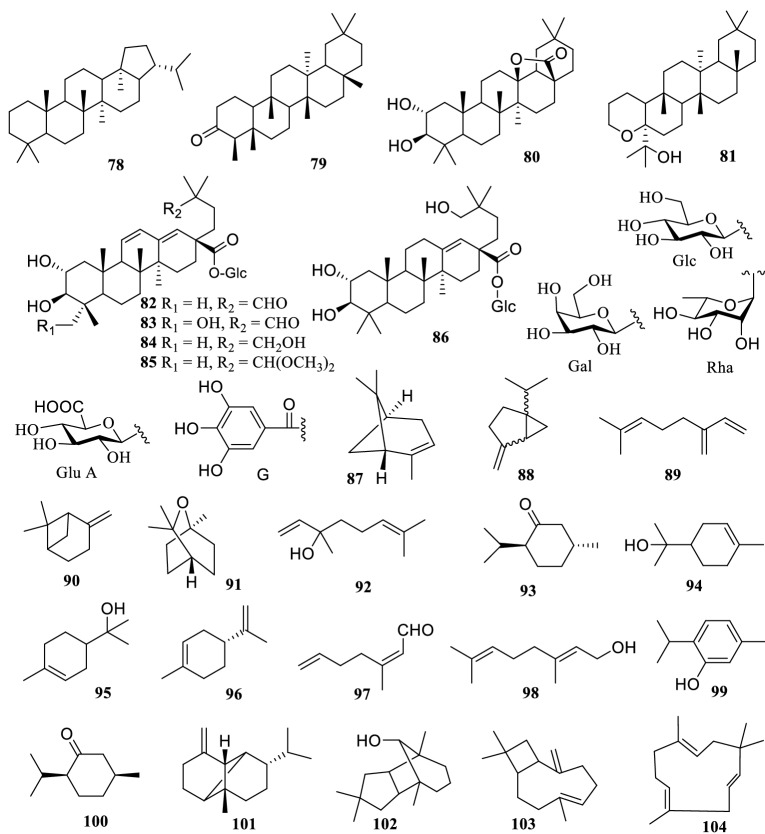

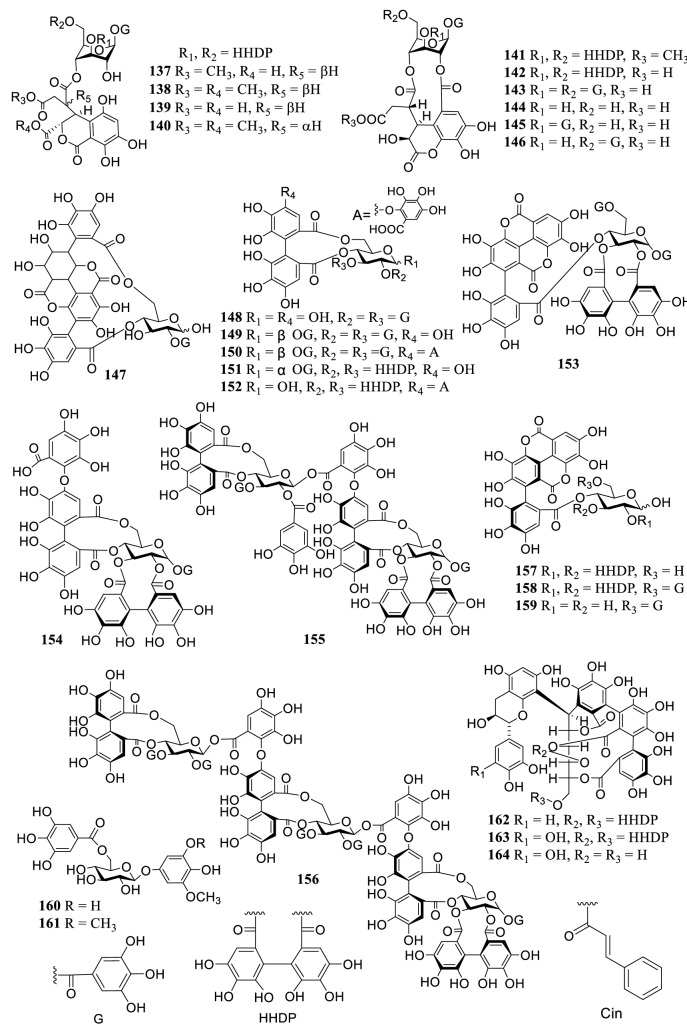

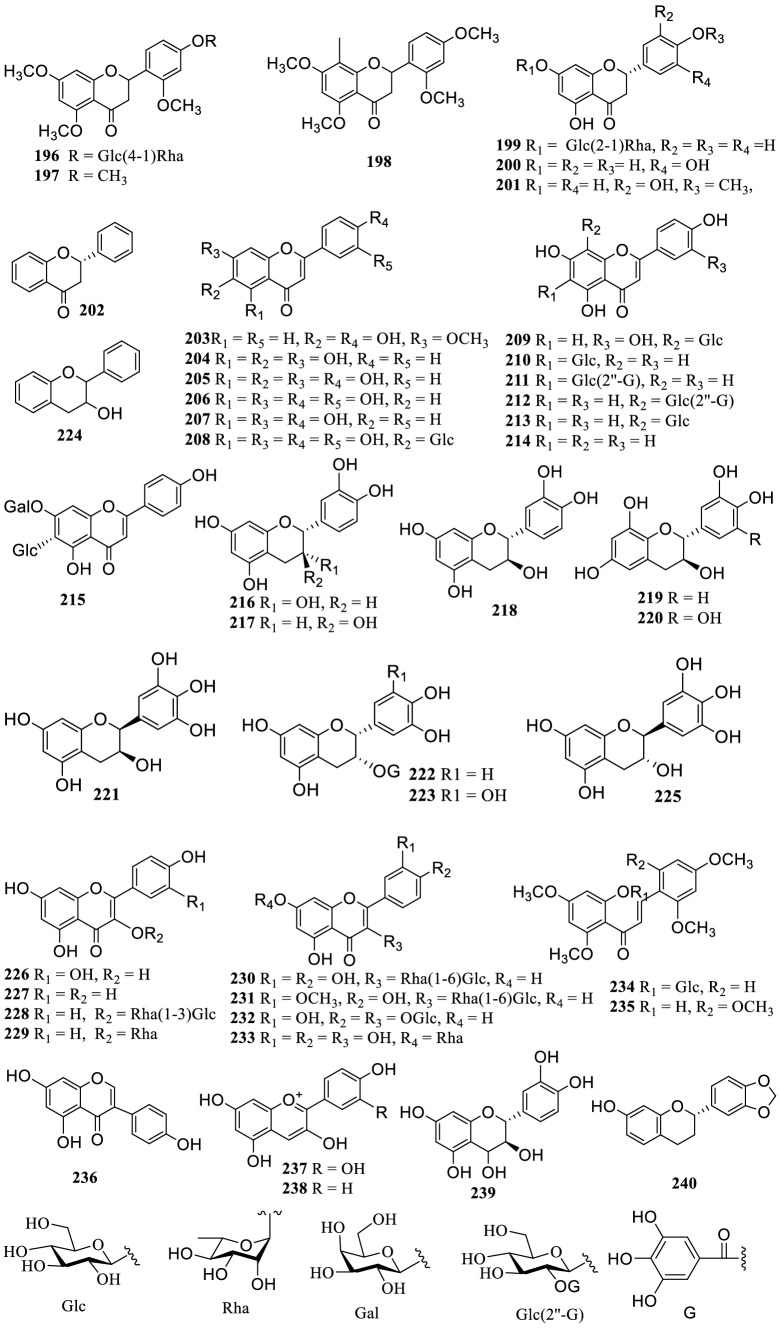

Flavonoids

The Terminalia genus are rich in flavonoids (Fig. 3) comprising of flavanones (196–202), flavones (203–215), flavan-3-ols (216–225), and flavonols (226–233). Among them, cerasidin (235) of chalcone, genistein (236) of isoflavone, and leucocyanidin (239) of flavan-3,4-diol from T. arjuna [80] were described as rare structural types in the Terminalia genus. Moreover, a new chalcone glycoside 2-O-β-glucosyloxy-4,6,2′,4′-tetramethoxychalchone (234) was reported from the roots of T. alata [53]. In addition, anthocyanidin cyanidin (237) and pelargonidin (238), flavanoid 7-hydroxy-3′,4-(methylenedioxy)flavan (240) and other structure were reported [12, 23, 66]. Compounds 209–213, 215 were C-glycosides at C-6 or C-8 of ring A.

Fig. 3.

The structures of flavonoids 197–240

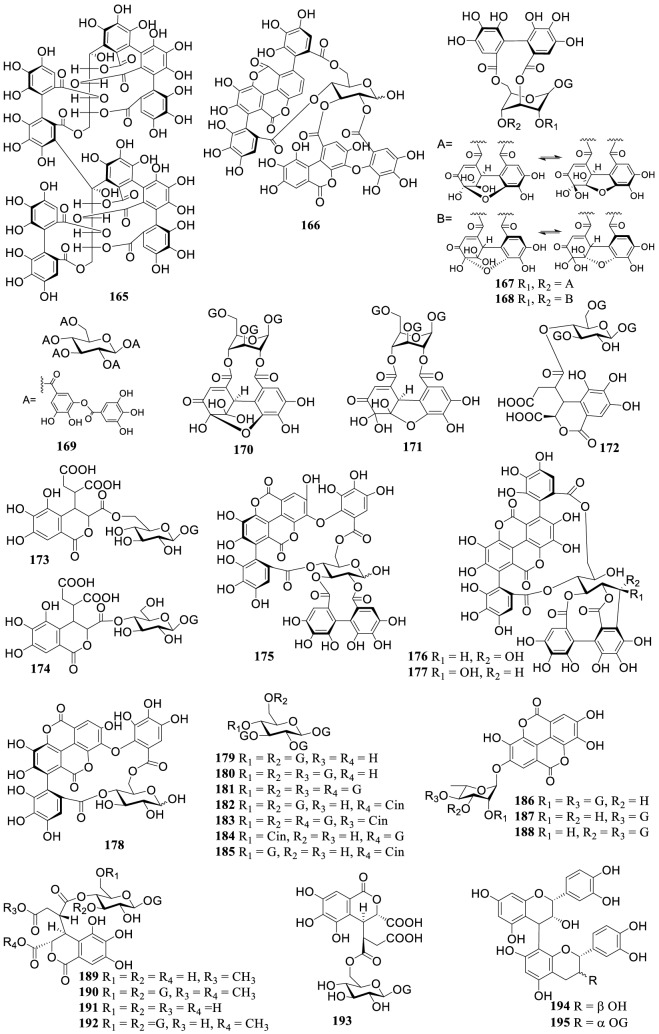

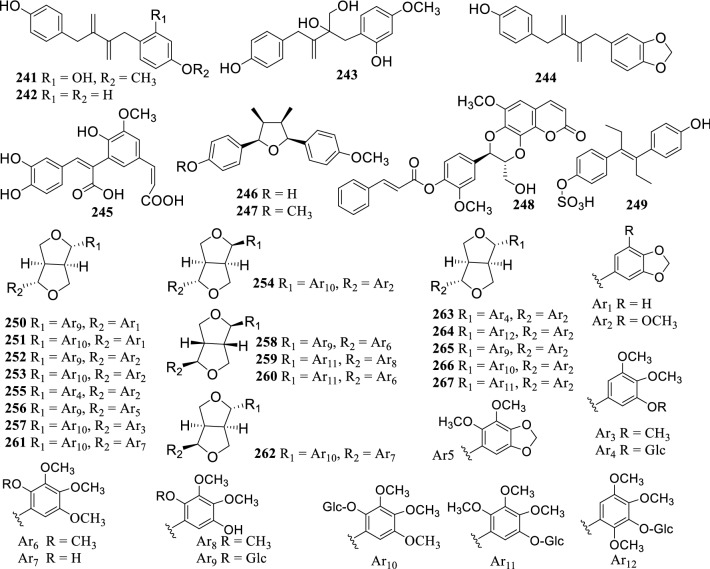

Lignans

Twenty-seven lignans (241–267) were reported from the genus Terminalia (Fig. 4). A new lignan 4′-O-cinnamoyl cleomiscosin A (248) was reported from the ethanol extract of T. tropophylla roots [72]. Moreover, 13 new furofuran lignan glucosides, terminalosides A–K (250–260), 2-epiterminaloside D (261), 6-epiterminaloside K (262) and 5 new polyalkoxylated furofuranone lignan glucosides, terminalosides L–P (263–267) were obtained from the leaves of T. citrina. All of them were tested for their estrogenic and/or antiestrogenic activities using estrogen responsive breast cancer cell lines T47D and MCF-7, and showed varying degrees of inhibitory activity. Among them, terminalosides B (251), G (256), L (263) and M (264) inhibited cell growth by up to 90% at a minimum concentration of 10 nM [22, 121].

Fig. 4.

The structures of lignans 241–267

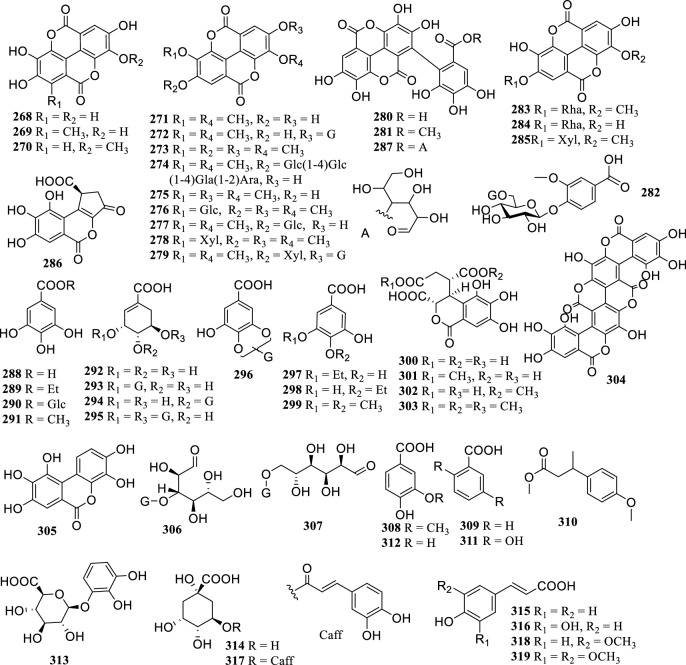

Phenols and Glycosides

There are 52 phenols and glycosides reported in the Terminalia genus (Fig. 5), in which ellagic acid (268) and gallic acid (289) are present in almost all species. Studies have shown that most of the simple phenolic compounds have antioxidant, antibacterial, hypoglycemic, liver and kidney protection [23].

Fig. 5.

The structures of phenols and glycosides (268–319)

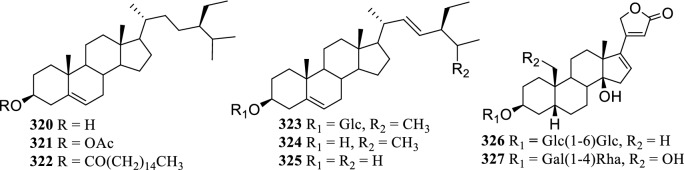

Sterols and Cardiac Glycosides

Only 6 sterols (320–325) and 2 cardiac glycosides (326-327) were isolated from the genus Terminalia before 2001 (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

The structures of steroids (320–325) and cardiac glycosides (326–327)

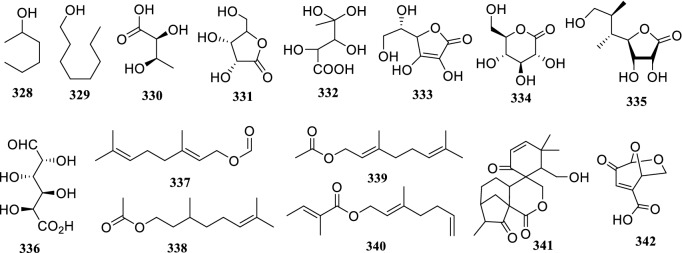

Polyols and Esters

Polyols and lipids were reported to be abundant in the genus Terminalia and concentrated mainly in fruits and leaves [125]. So far, 9 polyol (328–336) and 6 esters (337–342) have been documented (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

The structures of polyols and esters (328–342)

Other Compounds

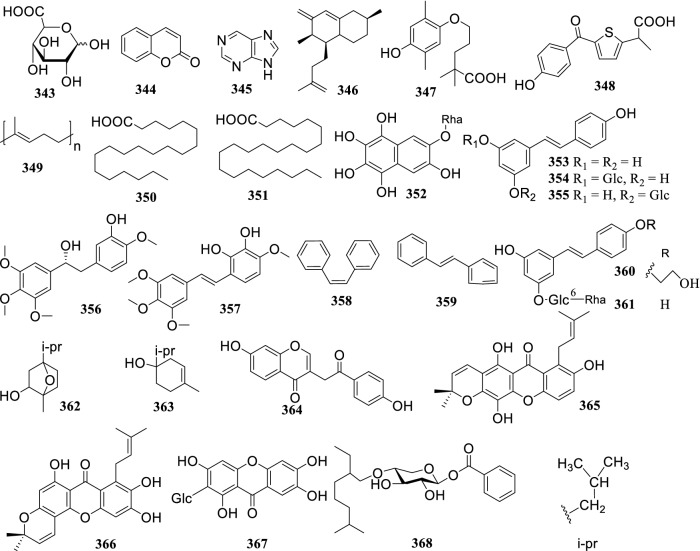

Other compounds featured in the Terminalia genus are shown in Fig. 8 and are mostly styrenes. Cao et al. isolated two new cytotoxic xanthones - termicalcicolanone A (365), termicalcicolanone B (366) in T. calcicola, and found an inhibitory effect on ovarian cancer [19]. Hiroko Negishi et al. obtained a new chromone derivative - terminalianone (364) from the barks of Terminalia brownii [98]. Ansari et al. isolated the novel compound, 4′-substituted benzoyl-β-d glycoside (368), from the fruits of T. bellirica and illustrated its potential for anticoagulation [160].

Fig. 8.

The structures of other compounds (343–368)

Moreover, chlorophyll and various vitamins were reported from the genus Terminalia.

Pharmacological Activities

The pharmacological activities of the genus Terminalia, mainly including antimicrobial, antioxidant, cytotoxicity, anti-inflammatory, hypoglycemic, cardiovascular, mosquitocidal and antiviral, have been extensively studied.

Antimicrobial

Extracts of several Terminalia species exhibit antimicrobial activity against various microbes. For example, methanol and aqueous extracts of T. australis were demonstrated antimicrobial activity against Ca. albicans (MIC = 180 and 250 µg/mL, resp.) and Ca. kruzzei (MIC = 250 and 300 µg/mL, resp.) [8]. Aqueous extracts of the stem barks, woods and whole roots of T. brownii showed antibacterial activity against standard strains of Sta. aureus (14.0 ± 1.1 µg/mL), Escherichia coli, Ps. aeruginosa (12.0 ± 1.1 µg/mL), Klebsiella pneumonia (6.0 ± 1.0 µg/mL), Sa. typhi and Bacillus anthracis (13.0 ± 1.0 µg/mL), as well as fungi Ca. albicans (12.3 ± 1.5 µg/mL) and Cr. neoformans (9.7 ± 1.1 µg/mL) [16]. Ethanol extracts of the root barks and leaves of T. schimperiana were against Sta. aureus, Ps. aeruginosa and Sa. typhi (MIC = 0.058–2.089 mg/mL), with inhibition zone diameters (IZDs) of 17.2 to 10.0 mm, compared to gentamicin (IZD = 21.8–10 mm). The results supported the efficacy of the extracts in the folkloric treatment of burns wounds, bronchitis and dysentery, respectively [42]. Antibacterial tests on Mycobacterium smegmatis ATCC 14468 showed that methanol extract of T. sambesiaca roots and stem barks had promising effects (MIC = 1.25 mg/mL, both) [133].

Ellagitannin punicalagin (133) obtained from the stem barks of T. mollis demonstrated crucial activity against Ca. parapsilosis and Ca. krusei (MIC = 6.25 μg/mL), as well as Ca. albicans (MIC = 12.5 μg/mL) [35]. 7-Hydroxy-3′,4′-(methylenedioxy) flavan (240), termilignan (241), anolignan B (242) and thannilignan (243) isolated from the fruit rinds of T. bellirica displayed significant antifungal activity against Penicillium expansum (MIC = 1.0, 2.0, 3.0 and 4.0 µg/mL, resp.), also with 240 and 241 against Ca. albicans at 10 and 6 µg/mL, resp. [12]. The antimycobacterial activity of friedelin (79) furnished from the root barks of T. avicennioides was 4.9 μg/mL in terms of MIC value [93]. β-Arjungenin (16), betulinic acid (74), sitosterol (319) and stigmasterol (323) from T. brownii were proved to possess antibacterial activity, with 74 the most active against A. niger and S. ipomoea (MIC = 50 μg/ml) [99].

Antioxidant

Terminalia species have also illustrated some interesting antioxidant properties [161]. By a 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) radical scavenging assay, relatively high anti-oxidant activities of the methanol extracts of T. alata, T. bellirica and T. corticosa trunk-barks were found (IC50 = 0.24, 1.02 and 0.25 mg/mL, resp.), compared to the positive control, l-ascorbic acid (IC50 = 0.24 mg/mL) [2].

Flavonoid glycosides, apigenin-6-C- (211) and apigenin-8-C- (212) (2″-O-galloy1)-β-d-glucoside, isolated from dried fallen leaves of T. catappa, showed significant antioxidative effects (IC50 = 2.1 and 4.5 µM, resp.) on Cu2+/02-induced low density lipoprotein lipid peroxidation, with probucol (IC50 = 4.0 µM) as positive control [105].

Arjunaphthanoloside (351), isolated from the stem barks of T. arjuna showed potent antioxidant activity and inhibited nitric oxide (NO) production in lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-stimulated rat peritoneal macrophages [87], while ivorenosides B (51) and C (52), two triterpenoid saponins from T. ivorensis, exhibited scavenging activities against DPPH and ABTS+ radicals [131].

The antioxidant potential of T. paniculata (TPW) was investigated by DPPH, ABTS2−, NO, superoxide (O2−), Fe2+ chelating and ferric reducing/antioxidant power (FRAP) assays. TPW showed maximum superoxide, ABTS2−, NO, DPPH inhibition, and Fe2+-chelating property at 400 µg/mL, resp. FRAP value was 4.5 ± 0.25 µg Fe(II)/g, which demonstrated the efficacy of aqueous barks extract of T. paniculata as a potential antioxidant and analgesic agent [142].

TaB contains various natural antioxidants and has been used to protect animal cells against oxidative stress. The alleviating effect of TaB aqueous extract against Ni toxicity in rice (Oryza sativa L.) suggested that TaB extract considerably alleviated Ni toxicity in rice seedlings by preventing Ni uptake and reducing oxidative stress in the seedlings [162]. Behavioral paradigms and PCR studies of TaB extract against picrotoxin-induced anxiety showed that TaB supplementation increased locomotion towards open arm (EPM), illuminated area (light–dark box test), and increased rearing frequency (open field test) in a dose dependent manner, compared to picrotoxin (P < 0.05). Furthermore, alcoholic extract of TaB showed protective activity against picrotoxin in mice by modulation of genes related to synaptic plasticity, neurotransmitters, and antioxidant enzymes [174].

Cytotoxicity

70% Acetone extracts of T. calamansanai leaves inhibited the viability of human promyelocytic leukemia HL-60 cells. Sanguiin H-4 (115), 1-α-O-galloylpunicalagin (136), punicalagin (135), 2-O-galloylpunicalin (147) and methyl gallate (290) were the main components isolated from T. calamansanai with the IC50 values of 65.2, 74.8, 42.2, 38.0 and > 100 µM, respectively, for HL-60 cells. Apoptosis of HL-60 cells treated with 1-α-O-galloylpunicalagin, 115, 135, and 147 was noted by the appearance of a sub-G1 peak in flow cytometric analysis and DNA fragmentation by gel electrophoresis. 115 and 147 induced a decrease of the human poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) cleavage-related procaspase-3 and elevated activity of caspase-3 in HL-60 cells, but not normal human peripheral blood mononuclear cells, PBMCs [18].

Terminaliaside A (60), an oleanane-type triterpenoid saponin isolated from the roots of T. tropophylla showed antiproliferative activity against the A2780 human ovarian cancer cell line with an IC50 value of 1.2 µM [72]. The 70% methanolic extract of T. chebula fruits was found to decrease cell viability, inhibit cell proliferation, and induce cell death of human (MCF-7) and mouse (S115) breast cancer, human osteosarcoma (HOS-1), human prostate cancer (PC-3) and a non-tumorigenic, immortalized human prostate (PNT1A) cell lines. Flow cytometry and other analyses showed that some apoptosis was induced by the extract at lower concentrations, but at higher concentrations, necrosis was the major mechanism of cell death. Chebulinic acid (143) and ellagic acid (186) were tested by ATP assay on HOS-1 cell line in comparison with three known antigrowth phenolics of Terminalia, gallic acid (287), methyl gallate (290), luteolin (206), and tannic acid (169). Results showed that the most growth inhibitory phenolics in T. chebula fruits were chebulinic acid (IC50 = 53.2 µM ±/0.16) >/tannic acid (IC50 = 59.0 mg/mL ±/0.19) > ellagic acid (IC50 = 78.5 µM ±/0.24) [111].

Aqueous and ethanolic extracts of T. citrina fruits were revealed to exhibit significant mutagenicity in tested strains of baby hamster kidney cell line (BHK-21). Ethanolic extract showed higher mutagenicity in TA 100 strain, whereas aqueous extract exhibited higher mutagenicity in TA 102 strain than TA 100. Both extracts showed dose-dependent mutagenicity. Fifty percent cell viability was exhibited by 260 and 545 μg/mL of ethanolic and aqueous extracts respectively [169]. Moreover, ivorenoside A (50) showed antiproliferative activity against MDA-MB-231 and HCT116 human cancer cell lines with IC50 values of 3.96 and 3.43 µM, respectively [131].

Anti-inflammatory

Inflammation has been considered as a major risk factor for various kinds of human diseases. Macrophages play substantial roles in host defense against infection. It can be activated by LPS, the major component of the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria. An investigation was carried out to determine anti-inflammatory potential of ethyl acetate fraction isolated from T. bellirica (EFTB) in LPS stimulated RAW 264.7 macrophage cell lines. EFTB (100 μg/mL) inhibited all inflammatory markers in dose dependent manner. Moreover, EFTB down regulated the mRNA expression of TNF-α, IL-6, COX-2 and NF-κB against LPS stimulation. These results demonstrated that EFTB is able to attenuate inflammatory response possibly via suppression of ROS and NO species, inhibiting the production of arachidonic acid metabolites, proinflammatory mediators and cytokines release [165].

Anolignan B (242) isolated from roots of T. sericea was tested for anti-inflammatory activity using the cyclooxygenase enzyme assays (COX-1 and COX-2) It showed activity against both COX-1 (IC50 = 1.5 mM) and COX-2 (IC50 = 7.5 mM) enzymes [151]. Termiarjunosides I (47) and II (48) isolated from stem barks of T. arjuna inhibited aggregation of platelets and suppressed the release of NO and superoxide from macrophages [156].

The anti-inflammatory activities of a polyphenol-rich fraction (TMEF) obtained from T. muelleri was assessed using carrageenan-induced paw edema model by measuring PGE2, TNF-α, IL-1b, and IL-6 plasma levels as well as the paw thickness. The group treated with 400 mg/kg of TMEF showed a greater inhibition in the number of writhes (by 63%) than the standard treated group (61%). TMEF pretreatment reduced the edema thickness by 48, 53, and 62% at the tested doses, respectively. TMEF administration inhibited the carrageenan-induced elevations in PGE2 (by 34, 43, and 47%), TNF-α (18, 28, and 41%), IL-1β (14, 22, and 29%), and IL-6 (26, 31, and 46%) [166].

Hypoglycemic

Some species and isolates from Terminalia have indicated possession of α-glucosidase inhibitory capabilities. Gallic acid (287) and methyl gallate (290), from stem barks of T. superba, showed significant activity (IC50 = 5.2 ± 0.2 and 11.5 ± 0.1 μM, resp.). Arjunic acid (5) and glaucinoic acid (46) from stem barks of T. glaucescens showed significant β-glucuronidase inhibitory activity with IC50 value 80.1 and 500 μM, resp., against β-glucuronidase [130].

In a study to investigate α-glucosidase inhibition of extracts and isolated compounds from T. macroptera leaves, chebulagic acid (142) showed an IC50 value of 0.05 µM towards α-glucosidase and 24.9 ± 0.4 µM towards 15-lipoxygenase (15-LO), in contrast to positive controls (acarbose: IC50 = 201 ± 28 µM towards α-glucosidase, quercetin: IC50 = 93 ± 3 µM towards 15-LO). Corilagin (116) and narcissin (231) were good 15-LO and α-glucosidase inhibitors. Rutin (230) was a good α-glucosidase inhibitor (IC50 ca. 3 µM), but less active towards 15-LO [136].

From the fruits of T. chebula, 23-O-galloylarjunolic acid (30) and 23-O-galloylarjunolic acid 28-O-β-d-glucosyl ester (31) were afforded and showed potent inhibitory activities with IC50 values of 21.7 (30) and 64.2 (31) µM, resp., against Baker’s yeast α-glucosidase, compared to the positive control, acarbose (IC50 174.0 µM) [146].

Hydrolyzable tannins, 1,2,3,6-tetra-O-galloyl-4-O-cinnamoyl-β-d-glucose (183) and 4-O-(2″,4″-di-O-galloyl-α-l-rhamnosyl) ellagic acid (186) from the fruits of T. chebula, showed significant α-glucosidase inhibitory activities with IC50 values of 2.9 and 6.4 µM, resp. In addition, inhibition kinetic studies showed that both compounds have mixed-type inhibitory activities with the inhibition constants (Ki) of 1.9 and 4.0 µM, respectively [159].

Cardiovascular

A few species of Terminalia have demonstrated cardiovascular activities. It was reported that the barks of T. arjuna possessed significant inotropic and hypotensive effect, mild diuretic, antithrombotic, prostaglandin E2 enhancing and hypolipidaemic activities [66].

Ethanolic extract of T. pallida fruits (TpFE) were studied to determine their cardioprotection against isoproterenol (ISO)-administered rats. The supplementation of TpFE dose-dependently exerts notable protection on myocardium by virtue of its strong antioxidant activity. It could be used as a medicinal food for the treatment of cardiovascular ailments [163].

Mosquitocidal

Insect-borne diseases remain to this day a major source of illness and can cause death worldwide. The resistance to chemical insecticides among mosquito species has been a major problem in vector control. The larvicidal and ovicidal activities of crude benzene, hexane, ethyl acetate, chloroform and methanol extracts of T. chebula were tested for their toxicity against three important vector mosquitoes, viz., Anopheles stephensi, Aedes aegypti and Culex quinquefasciatus. All extracts showed moderate larvicidal effects, the highest larval mortality was found in the methanol extract of T. chebula against the larvae of A. stephensi, A. aegypti, and C. quinquefasciatus with the LC50 values of 87.13, 93.24 and 111.98 ppm, respectively. Mean percent hatchability of the ovicidal activity was observed 48 h post treatment. All the five solvent extracts showed moderate ovicidal activity. The maximum egg mortality (zero hatchability) was observed in the methanol extract of T. chebula at 200 and 250 ppm against A. stephensi, while A. aegypti and C. quinquefasciatus showed 100% mortality at 300 ppm. No mortality was observed in the control group. The finding of the investigation revealed that the leaf extract of T. chebula possesses remarkable larvicidal and ovicidal activity against medically important vector mosquitoes [167, 168].

Antiviral

Termilignan (241) and anolignan B (242), obtained from T. bellirica exhibited antimalarial activity against the chloroquine-susceptible strain 3D7 of Plasmodium falciparum (IC50 = 9.6 ± 1.2 μM)[12]. Casuarinin (129), chebulagic acid (142) from the fruits of T. chebula possessed hepatitis C virus inhibition activities (IC50 = 9.6 and 5.2 μM, resp.) [118]. Punicalin (128) and 2-O-galloylpunicalin (147), isolated from aqueous extract of T. triflora leaves, showed inhibitory activity on HIV-1 reverse transcriptase with IC50 of 0.11 μg/mL (0.14 μM) and 0.10 μg/mL (0.11 μM), resp. [149].

In vitro anti-HIV-1 activity of acetone and methanol extracts of T. paniculata fruits was studied by Durge A. et al. Cytotoxicity tests were conducted on TZM-bl cells and PBMCs, the CC50 values of both extracts were ≥ 260 μg/mL. By using TZM-bl cells, the extracts were tested for their ability to inhibit replication of two primary isolates HIV-1 (X4, Subtype D) and HIV-1 (R5, Subtype C). The activity against HIV-1 primary isolate (R5, Subtype C) was confirmed by using activated PBMC and quantification of HIV-1 p24 antigen. Both the extracts showed anti-HIV-1 activity in a dose-dependent manner. The EC50 values of the acetone and methanol extracts of T. paniculata were ≤ 10.3 μg/mL. Furthermore, the enzymatic assays were performed to determine the mechanism of action which indicated that the anti-HIV-1 activity might be due to inhibition of reverse transcriptase (≥ 77.7% inhibition) and protease (≥ 69.9% inhibition) enzymes [172].

Kesharwani A. et al. investigated anti-HSV-2 activity of T. chebula extract and its constituents, chebulagic acid (142) and chebulinic acid (143). Cytotoxicity assay using Vero cells revealed CC50 = 409.71 ± 47.70 μg/mL for the extract whereas 142 and 143 showed more than 95% cell viability up to 200 μg/mL. The extract from T. chebula (IC50 = 0.01 ± 0.0002 μg/mL), chebulagic (IC50 = 1.41 ± 0.51 μg/mL) and chebulinic acids (IC50 = 0.06 ± 0.002 μg/mL) showed dose dependent in vitro anti-viral activity against HSV-2, which can also effectively prevent the attachment and penetration of the HSV-2 to Vero cells. In comparison, acyclovir showed poor direct anti-viral activity and failed to significantly (p > 0.05) prevent the attachment as well as penetration of HSV-2 to Vero cells when tested up to 50 μg/mL. Besides, in post-infection plaque reduction assay, T. chebula extract, chebulagic and chebulinic acids showed IC50 values of 50.06 ± 6.12, 31.84 ± 2.64, and 8.69 ± 2.09 μg/mL, resp., which were much lower than acyclovir (71.80 ± 19.95 μg/mL) [173].

Others

Terminalia species were also reported to be used in the treatment of diarrhea [95], Alzheimer’s disease [112], psoriasis [164], liver disease [170], kidney disease [171], etc. Terminalosides A–K (249–259) from the leaves of the Bangladeshi medicinal plant T. citrina possess estrogen-inhibitory properties. Among them, Terminaloside E (253) showed inhibitory activity against the T47D cell line, such terminalosides C (252), F (255), and I (258). Besides, 6-epiterminaloside K (262) displayed antiestrogenic activity against MCF-7 cells [22].

Conclusion and Future Prospects

The genus Terminalia contains not only a large number of tannins, simple phenolics, but also a lot of terpenoids, flavonoids, lignans and other compounds. Most tannins, simple phenolics and flavonoids have antioxidation, antibacterial, antiinflammatory and anticancer activities. The plants of the genus Terminalia have exhibited positive effect on immune regulation, cardiovascular disease and diabetes, and can accelerate wound healing [157]. Therefore, the Terminalia genus has great medicinal potential. However, most of the chemical composition of species is still unknown, we should use modern advanced technology such as LC–MS to continue to isolate its compounds, and determine their pharmacological activities and mechanism of action, to explore other possible greater medicinal value.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Key Projects of Yunnan Science and Technology, and Yunnan Key Laboratory of Natural Medicinal Chemistry (S2017-ZZ14).

Abbreviations

- A.

Aspergillus

- BCG

Bacillus Calmette Guerin

- BMM

Broth microdilution method

- Ca.

Candida

- Cr.

Cryptococcus

- CC50

Cytotoxic concentration of the extracts to cause death to 50% of host’s viable cells

- DPPH

2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl

- E.

Escherichia

- EC50

Half maximal effective concentration

- FRAP

Ferric reducing/antioxidant power

- GABA

Neurotransmitter gamma-aminobutyric acid

- IC50

Minimum inhibition concentration for inhibiting 50% of the pathogen

- K.

Klebsiella

- MIC

Minimum inhibitory concentration

- MTT

3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide

- Ps.

Pseudomonas

- Sa.

Salmonella

- Sta.

Staphylococcus

- Str.

Streptomyces

Conflict of interest

All authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.McGaw LJ, Rabe T, Sparg SG, Jäger AK, Eloff JN, van Staden J. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2001;75:45–50. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(00)00405-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nguyen Q, Nguyen VB, Eun J, Wang S, Nguyen DH, Tran TN, Ngugen AD. Res. Chem. Intermed. 2016;42:5859–5871. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Srivastava SK, Chouksey BK, Srivastava SD. Fitoterapia. 2001;72:191–193. doi: 10.1016/s0367-326x(00)00262-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arias D, Calvo-Alvarado J, de Richter DB, Dohrenbusch A. Biomass Bioenergy. 2011;35:1779–1788. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Y. Noboru, I. Ayako, K. Chika, S. Keisuke, JP2001098264 A 20010410 (2001)

- 6.Yadav RN, Rathore K. Phytochem. Commun. 2001;72:459–461. doi: 10.1016/s0367-326x(00)00337-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.S. Fangwen, P. Raoji, CN105232959 A 20160113 (2016)

- 8.Carpano SM, Spegazzini ED, Rossi JS, Castro MT, Debenedetti SL. Fitoterapia. 2003;74:294–297. doi: 10.1016/s0367-326x(03)00026-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Omonkhua AA, Cyril-Olutayo MC, Akanbi OM, Adebayo OA. Parasitol. Res. 2013;112:3497–3503. doi: 10.1007/s00436-013-3530-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zanna H, Ahmad S, Abdulmalik B. Tasi’u M, Abel GO, Musa HM. Adv. Biochem. 2014;2:55–59. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chopra RN, Nayar SL, Chopra IC. Glossary of Indian Medicinal Plants. New Delhi: CSIR; 1956. p. 241. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Valsaraj R, Pushpangadan P, Smitt UW, Adsersen A, Christensen SB, Sittie A, Nyman U, Nielsen C, Olsen CE. J. Nat. Prod. 1997;60:739–742. doi: 10.1021/np970010m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gurib-Fakim A. J. Essent. Oil Res. 1994;6:533–534. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khatoon S, Singh N, Srivastava N, Rawat A, Mehrotra S. J. Planar Chromatogr. 2008;21:167–171. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gelfand M. The Traditional Medical Practitioner in Zimbabwe, His Principles of Practice and Pharmacopoeia. Gweru: Mambo Press; 1985. pp. 58–61. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mbwambo ZH, Moshi MJ, Masimba PJ, Kapingu MC, Nondo RS. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2007;7:9. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-7-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McIntosh KS. Qld Agric. J. 1934;42:727–729. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen LG, Huang WT, Lee LT, Wang CC. Toxicol. Vitro. 2009;23:603–609. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2009.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cao S, Brodie PJ, Miller JS, Randrianaivo R, Ratovoson F, Birkinshaw C, Andriantsiferana R, Rasamison VE, Kingston DGI. J. Nat. Prod. 2007;70:679–681. doi: 10.1021/np060627g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin Y, Kuo Y, Shiao M, Chen C, Ou J. J. Chin. Chem. Soc. 2000;47:253–256. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bag A, Bhattacharyya SK, Chattopadhyay RR. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2013;3:244–252. doi: 10.1016/S2221-1691(13)60059-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Muhit MA, Umehara K, Moriyasumoto K, Noguchi H. J. Nat. Prod. 2016;79:1298–1307. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.5b01042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Singh A, Bajpai V, Kumar S, Kumar B, Srivastava M, Rameshkumar KB. Ind. Crop Prod. 2016;87:236–246. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang T, Sun H. J. Plant. Res. 2011;124:63–73. doi: 10.1007/s10265-010-0360-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Konczak I, Maillot F, Dalar A. Food Chem. 2014;151:248–256. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.11.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koudou J, Roblot G, Wylde R. Planta Med. 1995;61:490–491. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-958153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Okpekon T, Yolou S, Gleye C, Roblot F, Loiseau P, Bories C, Grellier P, Frappier F, Laurens A, Hocquemiller R. J. Ethnopharmcol. 2004;90:91–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2003.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O. Nobuhiko, S. Shizu, C. Nuan, JP2007099733 A 20070419 (2007)

- 29.Adiko VA, Attioua BK, Tonzibo FZ, Assi KM, Siomenan C, Djakouré LA. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2013;12:4393–4398. [Google Scholar]

- 30.J. Hutchinson, J.M. Dalziel, Appendix to the Flora of West Tropical Africa (Published on behalf of the Governments of Nigeria, Ghana, Sierra Leone and the Gambia by the Crown Agents for Oversea Governments and Administrations, London, 1936), p. 81

- 31.Anam K, Widharna RM, Kusrini D. Int. J. Pharmacol. 2009;5:277–280. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Musa MS, Abdelrasool FE, Elsheikh EA, Ahmed LA, Mahmoud ALE, Yagi SM. J. Med. Plants Res. 2011;5:4287–4297. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ogbazghi W, Bein E. Drylands Coord. Group Rep. 2006;40:26–27. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zou Y, Ho GTT, Malterud KE, Le NHT, Inngjerdingen KT, Barsett H, Diallo D, Michaelsen TE, Paulsen BS. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014;155:1219–1226. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2014.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu M, Katerere DR, Gray AI, Seidel V. Fitoterapia. 2009;80:369–373. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2009.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Anam K, Suganda AG, Sukandar EY, Kardono LBS. Res. J. Med. Plant. 2010;4:197–205. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bajpai M, Pande A, Tewari SK, Prakash D. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2005;56:287–291. doi: 10.1080/09637480500146606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marzouk MSA, El-Toumy SAA, Moharram FA. Planta Med. 2002;68:523–527. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-32549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oelrichs PB, Pearce CM, Zhu J, Filippich LJ. Nat. Toxins. 1994;2:144–150. doi: 10.1002/nt.2620020311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Malekzadeh F, Ehsanifar H, Shahamat M. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2001;18:85–88. doi: 10.1016/s0924-8579(01)00352-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lin TC, Hsu FL. J. Chin. Chem. Soc. 1999;46:613–618. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nmema EE, Anaele EN. J. Appl. Sci. Environ. Manag. 2013;17:595. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mongalo NI, McGaw LJ, Segapelo TV, Finnie JF, Van Staden J. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2016;194:789–802. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2016.10.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fyhrquist P, Mwasumbi L, Haeggstrom CA, Vuorela H, Hiltunen R, Vuorela P. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2002;79:169–177. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(01)00375-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chhabra SC, Mahunnah RLA, Mshiu EN. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1989;25:339–359. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(89)90038-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.B. Heine, M. Brenzinger, Plants of the Borana (Ethiopia and Kenya), Plant Concepts and Plant Use: An Ethno-botanical Survey of the Semi-arid and Arid Lands of East Africa: Part 4 (Verlag Brentenbach, 1988), p. 23

- 47.Ndamba J, Lemmich E, Mølgaard P. Phytochemistry. 1994;35:95–98. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(00)90515-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Katerere DR, Gray AI, Nash RJ, Waigh RD. Phytochemistry. 2003;63:81–88. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(02)00726-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tabopda TK, Ngoupayo J, Tanoli SAK, Mitaine-Offer AC, Ngadjui BT, Ali MS, Luu B, Lacaille-Dubois MA. Planta Med. 2009;75:522–527. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1185328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wansi JD, Lallemand MC, Chiozem DD, Toze FAA, Mbaze LMA, Naharkhan S, Iqbal MC, Fomum ZT. Phytochemistry. 2007;68:2096–2100. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2007.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jono T. Curr. Herpetol. 2015;34:85–88. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Srivastava SK, Srivastava SD, Chouksey BK. Fitoterapia. 2001;72:106–112. doi: 10.1016/s0367-326x(00)00261-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Srivastava SK, Srivastava SD, Chouksey BK. Fitoterapia. 1999;70:390–394. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Anjaneyulu ASR, Reddy AVR, Mallavarapu RG, Chandrasekhara RS. Phytochemistry. 1986;25:2670–2671. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mallavarapu GR, Rao SB, Syamasundar KV. J. Nat. Prod. 1986;49:549–550. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mallavarapu GR, Muralikrishna E. J. Nat. Prod. 1983;46:930–931. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Anjaneyulu ASR, Prasad AVR. Phytochemistry. 1983;22:993–998. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ali A, Kaur G, Hamid H, Abdullah T, Ali M, Niwa M, Alam MS. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 2003;5:137–142. doi: 10.1080/1028602031000066834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yadav RN, Rathore K. Fitoterapia. 2001;72:459–461. doi: 10.1016/s0367-326x(00)00337-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Honda T, Murae T, Tsuyuki T. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1976;24:178–180. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Honda T, Murae T, Tsuyuki T, Takahashi T, Sawai M. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1976;49:3213–3218. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Anjaneyulu ASR, Prasad ASR. J. Chem. 1982;21B:530–533. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Anjaneyulu ASR, Prasad AVR. Phytochemistry. 1982;21:2057–2060. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sharma PN, Shoeb PN, Kapil RS. Indian J. Chem. 1982;21:263–264. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pettit GR, Hoard MS, Doubek DL, Schmidt JM, Pettit RK, Tackett LP, Chapuis JC. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1996;53:57–63. doi: 10.1016/S0378-8741(96)01421-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dwivedi S. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2007;114:114–129. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2007.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Row LR, Murty PS, Rao GS, Sastry CP, Rao KVJ. Indian J. Chem. 1970;8:772–775. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wang W, Ali Z, Li XC, Shen Y, Khan IA. Planta Med. 2010;76:903–908. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1240841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Aiyelaagbe O, Olaoluwa O, Oladosu I, Gibbons S. Rec. Nat. Prod. 2014;8:7–11. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kalola J, Rajani M. Chromatographia. 2006;63:475–481. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bombardelli E, Martinelli EM, Mustich G. Phytochemistry. 1974;13:2559–2562. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cao S, Brodie PJ, Callmander M, Randrianaivo R, Rakotobe E, Rasamison VE, Kingston DG. Phytochemistry. 2010;71:95–99. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2009.09.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Nandy AK, Podder G, Sahu NP, Mahato SB. Phytochemistry. 1989;28:2769–2772. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tsuyuki T, Hamada Y, Honda T, Takahashi T, Matsushita K. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1979;52:3127–3128. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Jung SW, Shin MH, Jung JH, Kim ND, Im KS. Arch. Pharmacal Res. 2001;24:412–415. doi: 10.1007/BF02975185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]