Abstract

Objective

Depression is underdiagnosed and thus undertreated. This study aimed to validate the French version of the PHQ-2 (Patient Health Questionnaire-2) and BDF-FS-Fr (Beck Depression Inventory-Fast Screen-France) on patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) living in France.

Method

A cross-sectional study was conducted on 109 patients of the Centre universitaire de maladies rénales, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire (CHU) de Caen (37 patients with CKD on pre-dialysis and grafting stage, 36 grafted patients, and 36 dialyzed patients).

Statistical Approach

Test parameters and statistical aspects of assessing diagnostic and screening tests were used, including knowledge of and ability to calculate, sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values, diagnostic odds ratios, and the use of ROC (receiver operating characteristic) curves.

Results

PHQ-2 and BDI-FS-Fr statistical parameters for depression tested very positively and had a satisfactory AUC (area under the curve). The PHQ-2 had a satisfactory AUC > 0.70, sensitivity > 0.60, and specificity > 0.80. The BDI-FS-Fr had a satisfactory area under the curve (0.859) with sensitivity (83%) and specificity (0.859); and internal consistency (α = 0.668). The PHQ-2 and BDI-FS-Fr showed good internal and external validity of structure, construct validity, criterion validity, discriminant validity, internal consistency, and factorial validity.

Conclusion

The French versions of the PHQ-2 and BDI-FS have highly favorable psychometric properties. These instruments are valid self-assessment tools for screening and evaluating depression, its intensity, and its evolution. The PHQ-2 and BDI-FS-Fr thus have very good psychometric properties and are useful tools for researchers and practitioners. Regarding clinical practice in the hospital, clinicians and nurses can use the PHQ-2 to screen quickly for depression during routine consultations, during hospitalization, and in dialysis centers. The 7 items of the BDI-FS-Fr enable us to assess the depressive state, thereby avoiding a false diagnosis of depression among CKD patients in a clinical setting.

Keywords: Chronic kidney disease, Depression, Screening, Diagnosis, PHQ-2, BDI-FS-Fr, Reliability, Validity, Scale, Psychometric characteristics, French

Introduction

Depression is commonly observed in chronic kidney disease (CKD) patients, especially in stage 5 disease [1, 2], where the prevalence is very high (20–30%) [1]. In dialysis patients, the prevalence varies between 10 and 50% according to studies, showing that depression is the most frequently observed mental disorder [3]. The negative effects of depression have been demonstrated in the CKD population [1, 4, 5], with one being poor adherence to medication [1]. There are little data in the literature describing depression and its effects on patients with a renal transplant and on patients with renal failure prior to renal replacement therapy [6]. Depression can be difficult to identify in CKD patients because many of the key symptoms such as fatigue, loss of appetite, memory, and concentration can also be attributed to kidney disease itself. Thus, difficulties in detecting and/or diagnosing depression can lead to false diagnoses of depression [2, 7].

According to Feinstein [7], HADS (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale) and BDI-FS (Beck Depression Inventory-Fast Screen) are the two best-constructed self-assessment scales to make this distinction. The reasons for validating the self-assessment instrument (BDI-FS), rather than using the HADS, are related to their psychometric characteristics. In fact, in the English version and French version tested on patients as well as students [8, 9], the BDI-FS shows good validity and reliability. The BDI-FS allows screening for the two DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criteria of depression, as well as a suicidal ideation and suicide risk. These are assessed in patients by observing items 2 (pessimism) and 7 (suicidal thoughts or desires), which are considered suicidal risk indicators [8, 10]. This tool is a measure of depressive cognition [8, 9] and does not interfere with clinical factors. Conversely, patients commented that the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) items are repetitive, and that two questions in the HADS were confusing during the interviews (question 5 and 7 depends on age and personal interest). We therefore need to create a rapid diagnostic tool to assess depression in the form of a short evaluation scale, which will be widely used for its simplicity of execution. For the aforementioned reasons, we wish to validate the BDI-FS in CKD patients.

Prior to diagnosis, prompt, effective, and systematic screening for early identification of depressive symptoms in CKD is essential. This screening is performed using two simple questions (Patient Health Questionnaire-2, PHQ-2). These two questions assess depressive mood and anhedonia (loss of interest and pleasure) [11, 12]. These two simple questions are validated for patents with multiple sclerosis [13] and were only translated by French researchers at the Neurology service, Pasteur Hospital, Nice [14]. They are also needed to screen for depression in chronic diseases [15].

The uniqueness of this study is that it has never been conducted in France. Since Beck developed BDI-FS in 2000 [10] and Spitzer et al. [11] PHQ-2 in 1999, these two tests (PHQ-2 and BDI-FS) have not been used to detect depression in a population with chronic diseases and/or chronic conditions, such as CKD, in France until now.

Objective

The main objective of this study is to validate and evaluate the effectiveness of the PHQ-2 as a depression screening tool as well as the effectiveness of the BDF-FS-Fr as a diagnostic tool identifying depression in CKD (patients with CKD on predialysis and grafting stage, grafted patients, and dialyzed patients) compared with BDI-II (reference tool).

Methods

Sample

The sample consisted of 109 patients (66 men and 43 women; 37 patients with CKD before the dialysis and / or grafting stage, 36 grafted patients and 36 dialyzed patients) from the Centre Hospitalier Universitaire (CHU) de Caen (Centre universitaire de maladies rénales au CHU de Caen) aged 19–92 years (age: mean = 63.48, SD = 15.73). Participation was voluntary.

Sample Statistical Power

Three groups of patients with CKD (patients with CKD before the dialysis and grafting stage, grafted patients, dialyzed patients) were included to validate the PHQ-2 and BDF-FS-Fr in a CKD population. There were at least 36 patients in each group. In order to ascertain whether either of these screening tools were useful, power calculations were also performed for subgroups. Cohen [16] reports that 35 participants provide 88% statistical power to detect a correlation of 0.50 to p < 0.05, or 98% of its power, to detect a correlation of 0.60 at the same value from p. So, we think that a sample of 36 patients in each subgroup (i.e., 109 patients) is necessary and sufficient to obtain a reliable result.

Recruitment Procedure

Nephrology or nurses from the nephrology department recruited patients with chronic renal failure and proposed them to participate in the study. Each patient was informed of the general theme of the research, as well as the protocol procedures (interview with self-administered questionnaires) and was given the letter of agreement. If the patient agreed to participate in the study, the neuropsychologist took care of them for the interview based on DSM-5TM diagnostic criteria and questionnaires. The questionnaires used were: PHQ-2, BDI-FS, BDI-II, HADS, RSES (Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale), and SWLS (Satisfaction with Life Scale). The flowchart below displays each steps of the data collection.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The study included all patients presenting with CKD (predialysis patients and/or grafting stage, grafted patients and dialyzed patients), and each patient signed a consent form to participate in the study. All patients were > 18 years old. We also excluded all patients who did not understand French or who presented any other conditions or disorders that would make it impossible for them to understand the study. To avoid the impact of age and other disorders as cognitive disorders, patients were administered self-scales in the presence of the neuropsychologist.

Measurement and Instruments

Demographic and Clinical Data Scale

Demographic, socioeconomic, academic, and clinical information such as age, sex, difficulty in waking up in the morning, economic situation, place of residence, education level, current living situation, duration of CKD, CKD-EPI, and diabetic nephropathy were collected to control the confounding factors according to recommendation of Skelly et al. [17].

Based on the studies [8, 18], we assessed the socioeconomic factors: economic situation, place of residence, and current living situation. The place of residence was assessed by a binary response (urban and semi-urban, rural and semi-rural), the economic situation on a Likert scale (good, moderate, bad), and current family status on a Likert scale (alone; with/without child; parent(s); couple, with/without child).

Patient Health Questionnaire-2

The PHQ-2 consists of 2 self-assessment items [11] taken from the 9 items of the PHQ-9. The psychometric properties of the PHQ-2 require assessment in French. The two items are set up to assess mood status in the previous 2 weeks, giving a maximum total score of 2 and a minimum of 0. The PHQ-2 can only provide 3 data points: 0, 1, or 2. The two specific elements on this measure include depressive mood and loss of pleasure (anhedonia). This step requires approximately 30 s. Diagnostic cut-off value for the PHQ-2 is ≥1 [14, 15]. The French version of the PHQ-2 is available from the first author.

Beck Depression Inventory-Fast Screen

The BDI-FS is a short version of the BDI-II. The BDI-FS [8, 9, 10] consists of 7 items of the 21 of self-assessment Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II) [19]. The BDI-II has already been translated and validated in French [8, 9, 10]. For its interpretation, the manual suggests that scores of 0–3 indicate minimal depression; 4–6 indicate mild depression; 7–9 indicate moderate depression; and 10–21 indicate severe depression [8, 9, 10, 20]. Diagnostic cut-off value for BDI-FS is ≥4 [8, 9, 10]. The French version of the BDI-FS-Fr is available from the first author.

The BDI-II performed well on adult patients and was used in nonmedical and medical studies [19, 20]. Beck et al. [19, 20] “suggested the following ranges of BDI-II cut-off scores for depression: 0–13 (minimal), 14–19 (mild), 20–28 (moderate), and 29–63 (severe) [20].” Possible cutoff score for BDI-II in patients with ESRD is > 14 to 16 [21, 22, 23, 24]. The majority of studies use 14 as cutoff score [8, 9, 17, 20, 25], but other studies use 16 as cutoff score [1]. Based on these studies [8, 9, 17, 20, 25], diagnostic cut-off value for BDI-II is ≥14. The chosen tool “as the gold standard,” is the BDI-II using 14 as a cut-off point for depression.

The BDI-II [26, 27], RSES [28], SWLS [29], and HADS [3] were also used.

Statistical Analysis

The psychometric property studied is the reliability of the tool, which includes the construct validity, criterion validity, internal consistency, and factorial validity. First, we calculated the mean, SD, and percent for all the data. Second, the convergent [30] and divergent validity was established through intercorrelation measurements (using Pearson's r) for the scores obtained from the PHQ-2, BDI-FS-Fr, BDI-II, HADS, SWLS, and RSES. Third, the following diagnostic values were calculated: sensitivity, specificity, prevalence, positive and negative predictive values, positive and negative likelihood ratio, diagnostic odds ratio, accuracy, ROC curve (receiver operating characteristic), and area under the curve (AUC). The values for sensitivity, specificity, and predictivity are considered low between 0.00 and 0.29, moderate between 0.30 and 0.69, and high between 0.70 and 1.00 [31]. Finally, the adequacy of the items and internal consistency of the scale were estimated by Cronbach's α, which is each dimension of the tool [30]; and data from the BDI-FS-Fr were also submitted for a factor analysis to check the structural validity. Statistical analysis was performed using the computer software environment R (programming language R version). This study set significance at p ≤ 0.05. There were no missing data.

Results

Preliminary Analysis: Descriptive Statistics and Characteristics of the Sample

We conducted a first phase of descriptive analysis, and the results are presented in Table 1. The demographic and clinical characteristics of patients are described using mean, SD, and percent (%). The rates of depression according to different questionnaires are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Analysis: descriptive statistics (n = 109)

| Age, years | 63.48 ± 15.73 |

| Sex | |

| Male | 66 (61%) |

| Female | 43 (39%) |

| Diabetic | 29/109 (26.6%) |

| CKD-EPI, mL/min | |

| CKD | 32.05 ± 16.29 |

| Graft | 50.56 ± 21.22a |

| PHQ-2 | 0.59 ± 0.77 |

| Rate of depression, PHQ-2 g ≥ 1 | 41.3 |

| Depression-BDI-FS-Fr | 2.52 ± 2.80 |

| Rate of depression, BDI-FS-Fr ≥ 4 | 27.5% |

| Depression-BDI-II | 10.28 ± 7.55 |

| Rate of depression, BDI-II ≥ 14 | 31.2% |

| Depression-HADS | 4.23 ± 2.89 |

| Rate of depression, HADS ≥ 8 | 16.5% |

| Anxiety-HADs | 5.86 ± 3.90 |

| Rate of Anxiety, HADS ≥ 8 | 27.5% |

| Self-esteem (RSES) | 33.3 ± 5.21 |

| Satisfaction with life scale (SWLS) | 27.12 ± 5.71 |

| Treatment | |

| Treatment for depression | 8% |

| Treatment for anxiety | 12% |

| Difficulties | |

| Difficulties getting up in the morning | 18% |

| Difficulties waking up in the morning | 6% |

| Negatively influence of these difficulties on the patient ' s general state | 6% |

| Nephropathy,n | |

| Glomerulonephritis | 25 |

| Miscellaneous | 20 |

| Diabetic | 19 |

| Uropathy | 11 |

| Polycystic disease | 8 |

| Vascular | 8 |

| Interstitial nephritis | 4 |

| Obstructive | 2 |

| Systemic disease | 2 |

| Unknown | 10 |

| Duration of CKD | 16.27 ± 12.39 (4 months to 70 years) |

| Duration of dialysis | 6.65 ± 10.45 (1 week to 43 years) |

| Patients on dialysis | 71/109 (65%) |

| Duration of graft | 10.89 ± 7.33 (1 month to 27 years) |

| Patients with graft | 44/109 (40%) |

| Education level,n | |

| No | 15 |

| College certificate | 62 |

| BAC and + | 32 |

| Current marital status,n | |

| Married/couple | 69 |

| Widower | 17 |

| Separated/divorced | 8 |

| Single | 12 |

| Other (paces) | 3 |

| Place of residence,n | |

| Urban, semi-urban | 50 |

| Rural, semi-rural | 59 |

| Economic situation,n | |

| Poor | 10 |

| Moderate | 47 |

| Good | 52 |

| Employment,n | |

| Housewife | 1 |

| Student | 1 |

| Unemployed | 4 |

| Other (disability) | 9 |

| Active | 26 |

| Retired | 68 |

Data are presented as mean ± SD or as stated.

8% stage 2; 38% stage 3; 51% stage 4; 3% end-stage.

Applicability

The length of the PHQ-2 test is ±30 s and ±2 min for the BDI-FS-Fr. The purpose of these two questionnaires is well-understood by patients: they quickly understand guidelines and the items.

Construct Validity (Convergent and Divergent Validity)

The relationships among PHQ-2, BDI-FS-Fr, BDI-II, D-HADS, and A-HADS (convergent validity), and among PHQ-2, BDI-FS-Fr, SWLS and RSES (divergent validity), were tested using Pearson's r correlations. Table 2 shows the intercorrelations between depression scores, anxiety, satisfaction with life, and self-esteem. The PHQ-2 and its items (Q1 and Q2), and the BDI-FS-Fr, are significantly correlated with depression scores (p < 0.01) and anxiety (p < 0.01), and are significantly and negatively correlated with the score for self-esteem and satisfaction with life (p < 0.01). These correlations confirm the convergent and divergent validity of the PHQ-2 and the BDI-FS-Fr. Therefore, the PHQ-2 and the BDI-FS-Fr show good construct validity (convergent and divergent validity) and good external validity of structure.

Table 2.

Intercorrelations between scale scores

| Questionnaires | Q1 | Q2 | PHQ-2 | BDI-FS-Fr | BDI-II | RSES | A-HADS | D-HADS | SWLS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 | 1.00 | 0.47** | 0.88*** | 0.56*** | 0.58*** | − 0.31** | 0.46** | 0.41** | − 0.21** |

| Q2 | 1.00 | 0.83*** | 0.62*** | 0.58*** | − 0.41** | 0.38** | 0.41** | − 0.38** | |

| PHQ-2 | 1.00 | 0.69*** | 0.68*** | − 0.41** | 0.49** | 0.48** | − 0.34** | ||

| BDI-FS-Fr | 1.00 | 0.83*** | − 0.53*** | 0.49** | 0.58*** | − 0.32** | |||

| BDI-II | 1.00 | − 0.54*** | 0.58*** | 0.66*** | − 0.39** | ||||

| RSES | 1.00 | − 0.29** | − 0.46** | 0.44** | |||||

| A-HADS | 1.00 | 0.29** | − 0.14* | ||||||

| D-HADS | 1.00 | − 0.26** | |||||||

| SWLS | 1.00 |

Q, question; D, depression; A, anxiety.

p < 0.001;

p < 0.01;

p < 0.05.

Characteristics of Screening and Diagnostic Tests: Analysis of the Sensitivity and Specificity of the PHQ-2 and BDI-FS-Fr with a Reference Test (BDI-II)

The gold standard for comparison of the PHQ-2 and the BDI-SF is BD-II. The characteristics of the screening (PHQ-2) and diagnostic (BDI-FS-Fr) tests, compared with BDI-II, are shown in Table 3. In our research, the sensitivity and specificity show that the PHQ-2 (screening test) and BDI-FS-Fr (diagnostic test) are highly reliable. To estimate the efficiency and discriminatory aspects of PHQ-2 and BDI-FS-Fr, we also used other criteria (Table 3). Thus, the results showed a good odds ratio (OR), indicating that the PHQ-2 (screening test) and BDI-FS-Fr (diagnostic test) are discriminatory. The result of the proportion of properly classified subjects (accuracy) and other criteria (Table 3) showed that the PHQ-2 is a screening test and BDI-FS-Fr is a diagnostic test.

Table 3.

Characteristics of screening and diagnostic tests in comparison to BDI-II (gold standard)

| PHQ-2 ≥ 1 (screening test) | PHQ-2 = 2 | PHQ-2: Q1 (depressive mood) | PHQ-2: Q2 (anhedonia) | BDI-FS-Fr and BDI-II (diagnostic test) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity, % | 64 | 79 | 63 | 79 | 83 |

| CI: 50–77 | CI: 57–91 | CI: 47–76 | CI: 60–91 | IC: 66–93 | |

| Specificity, % | 92 | 79 | 87 | 82 | 89 |

| CI: 83–97 | CI: 69–86 | CI: 77–93 | CI: 73–89 | IC:80–94 | |

| Likelihood ratios positive | 8.25 | 3.74 | 4.79 | 4.49 | 7.31 |

| CI: 3.46–19.67 | CI: 2.36–5.94 | CI: 2.49–9.22 | CI: 2.71–7.42 | IC: 3.88–13.81 | |

| Likelihood ratios negative | 0.39 | 0.27 | 0.43 | 0.25 | 0.19 |

| CI: 0.26–0.58 | CI: 0.11–0.64 | CI: 0.29–0.65 | CI: 0.12–0.56 | IC: 0.08–0.42 | |

| Diagnostics odds ratio | 21.39 | 14.01 | 11.11 | 17.73 | 38.89 |

| CI: 7.13–64.13 | CI: 4.164–47.16 | CI: 4.30–28.70 | CI: 5.72–5.01 | IC:11.89–127.16 | |

| Positive predictive value, % | 85.29 | 44.12 | 73.53 | 55.88 | 73.53 |

| CI: 69.87–93.55 | CI: 28.88–60.55 | CI: 56.88–85.40 | CI: 39.45–71.12 | IC: 56.88–85.40 | |

| Negative predictive value, % | 78.67 | 94.67 | 80.00 | 93.33 | 93.33 |

| CI: 68.12–86.42 | CI: 87.07–97.91 | CI: 69.58–87.49 | CI: 85.32–97.12 | IC: 85.3–97.12 | |

| Prevalence, % | 41.28 | 17.43 | 36.70 | 22.02 | 27.52 |

| Accuracy, % | 80.73 | 78.90 | 78.00 | 81.65 | 0.87 |

| Accuracy +, % | 73 | 57 | 68 | 66 | 0.78 |

| Accuracy −, % | 85 | 86 | 83 | 88 | 0.91 |

| Youden ' s index | 0.57 | 0.58 | 0.49 | 0.62 | 0.72 |

| Yule ' s Q coefficient | 0.91 | 0.87 | 0.83 | 0.89 | 0.95 |

| χ2 | 39.48 | 24.45 | 28.86 | 33.00 | 52.43 |

CI, confidence interval (95%).

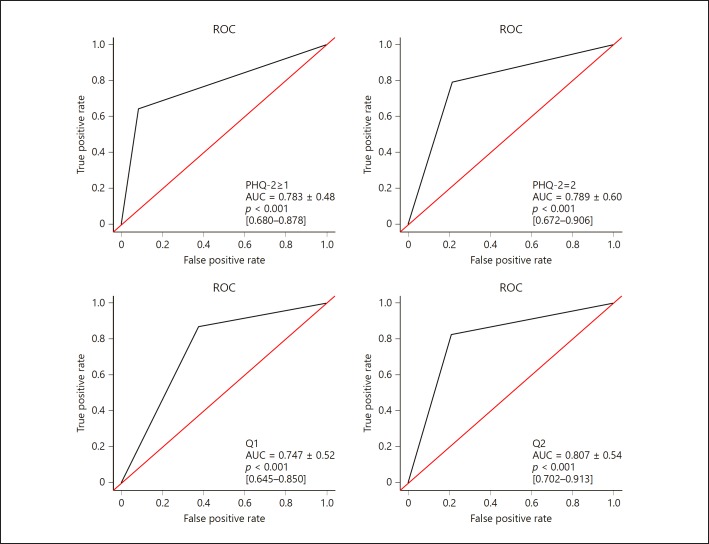

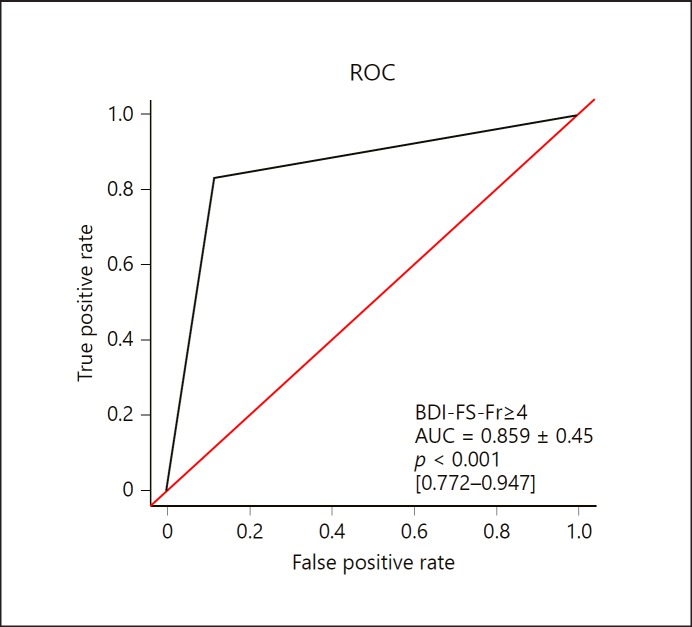

The ROC curves for the PHQ-2 and the BDI-FS-Fr are shown in Figures 1 and 2. The PHQ-2 and the BDI-FS-Fr show good ability to discriminate between depressive subjects and healthy subjects because the values of the two areas under the curve (AUC) are between 0.70 and 0.90 (criterion satisfactory according to Swets [32]). The ROC indicates that the instrument is very useful for predicting the presence or absence of depression.

Fig. 1.

ROC curve of the PHQ-2 compared with the BDI-II: sensitivity vs. 1 – specificity.

Fig. 2.

ROC curve of the BDI-FS-Fr compared with the BDI-II: sensitivity vs. 1 – specificity.

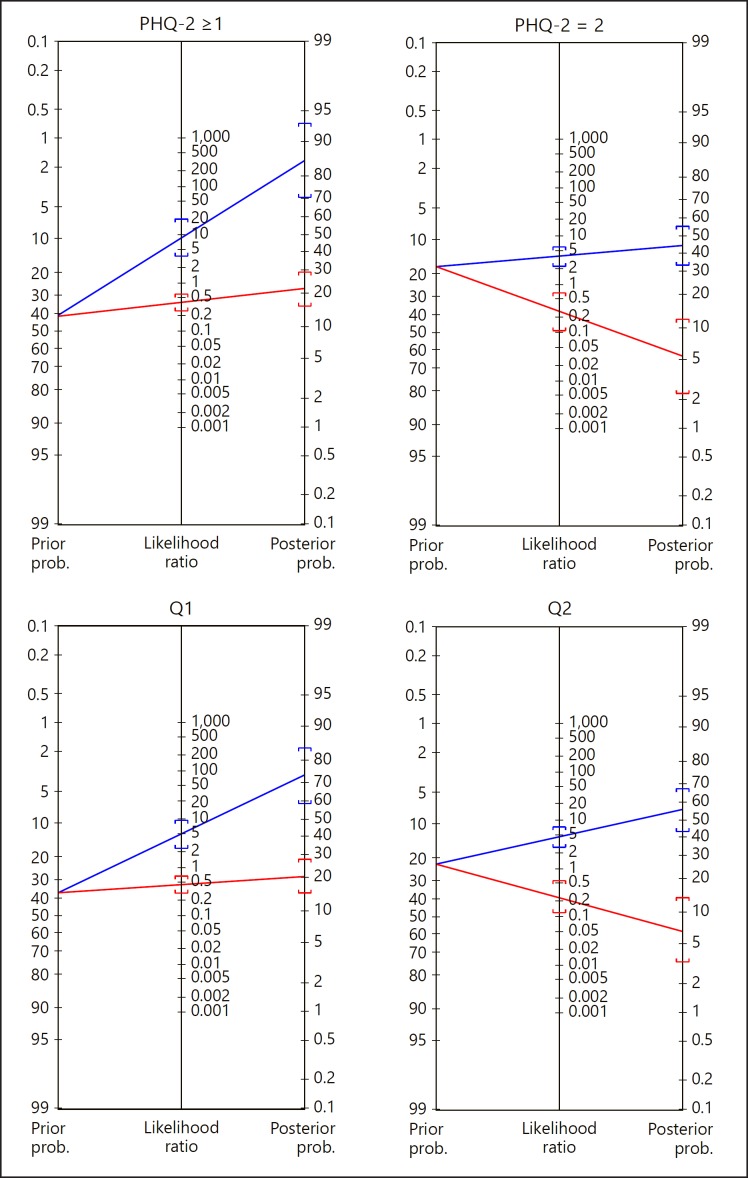

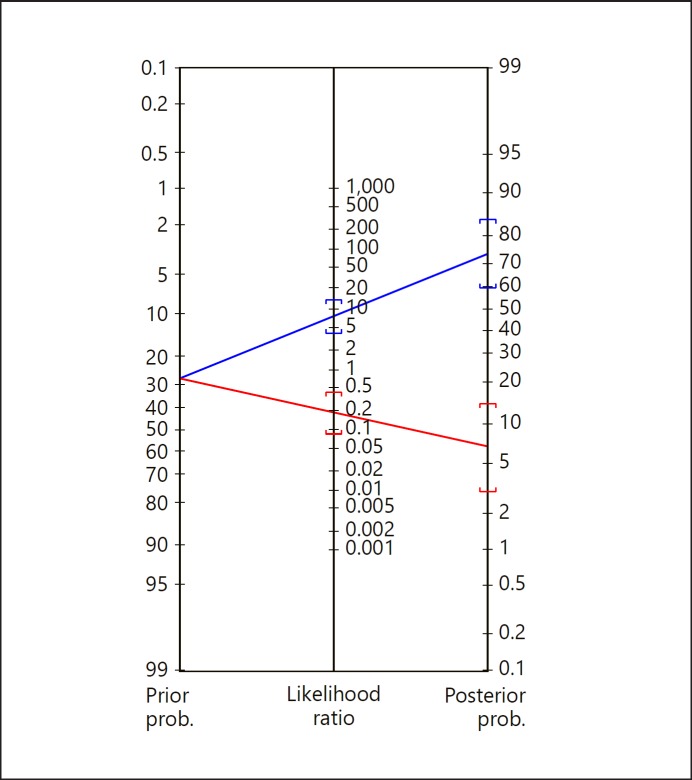

By applying Bayes' theorem [33] to this study, we can also determine the probability of depression according to different values of pretest probability for the PHQ-2 and BDI-FS-Fr (Fig. 3, 4). The posttest probability of the sample for a positive test is 74% (95% confidence interval [CI], 60–84%) between the BDI-FS-Fr and BDI-II. This result illustrates the importance of the influence of the prior probability on the posterior probability. The pretest probability for depression in the sample (prevalence) is very high (28%); the posttest probability for a negative test is 7% (95% CI, 3–14%) (Table 4). This finding illustrates the importance of determining the prior probability of disease in a patient (pretest probability of the individual) before carrying out a test and allows us to anticipate a posterior probability based on the test result. The step is to compare the pre- and posttest probability of the sample on one hand and the individual on the other.

Fig. 3.

Posttest probability of depression disease between the PHQ-2 and BDI-II.

Fig. 4.

Posttest probability of depression disease between the BDI-FS-Fr and BDI-II.

Table 4.

Sensitivity, specificity, and AUC from ROC analysis for different points of DBI-FS-Fr

| BDI-FS-Fr ≥ 3 | BDI-FS-Fr ≥ 4 | BDI-FS-Fr ≥ 5 | BDI-FS-Fr ≥ 6 | BDI-FS-Fr ≥ 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity, % | 90 | 83 | 86 | 81 | 77 |

| Specificity, % | 66 | 89 | 92 | 94 | 100 |

| AUC | 0.777 | 0.859 | 0.887 | 0.878 | 0.882 |

Receiver Operating Characteristics of DBI-FS-Fr

According to a study on patients suffering from end-stage renal disease (ESRD), the AUC for BDI-FS was 0.982 [1]. “Receiver operating characteristics showed the best balance between sensitivity and specificity for the BDI-FS cutoff value of ≥4 with a sensitivity of 97.2% (95% CI, 85.5–99.9%) and a specificity of 91.8% (95% CI, 84.5–96.4%)” [1]. In a study from a sleep disorders clinic [34], a threshold of BDI-FS ≥4, 5, 6, 7 has been analyzed based on sensitivity, specificity, and AUC.

In this study, the question that arises is: How was the cut-off score of 4 and above of BDI-FS-Fr selected to confirm the diagnosis of depression? To answer this question, different ROC curves and AUC based on different points were made, and then optimal value was selected (Table 4).

The BDI-FS-Fr has the ability to discriminate and identify major depressive episode. We identified a BDI-FS score ≥4 or 5 or 6, which is a higher threshold score than ≥3 or 7. We recommended score ≥4 as diagnostic cut-off value which was recommended by Beck et al. [10] in their original study.

Internal Consistency of BDI-FS-Fr

Regarding the internal consistency of the BDI-FS-Fr, the Cronbach α coefficient is 0.668 (0.531–0.753) for the BDI-FS-Fr score. The bisection (odd-even) is 0.578 (p < 0.0001) and the Spearman-Brown Prophecy coefficient is 0.734 (p < 0.0001).

Dimensionality

The results show that the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin test is 0.64, which is greater than 0.50; this result is confirmed by Bartlett's test with good significance (p < 0.001). The results of the exploratory factor analysis with 7 items of the BDI-FS-Fr and application of Kaiser Criteria with eigenvalues > 1 [32] allow us to retain two factors that represent 51.27% of the total variance of the BDI-FS-Fr. The saturation coefficients are satisfactory (Table 5).

Table 5.

Solution 2 factors of the BDI-FS-Fr with varimax rotation (n = 109)

| BDI-FS-Fr items | Component |

|

|---|---|---|

| factor 1: main component of depression | factor 2: cognitive component of depression | |

| Question 4: Anhedonia (loss of pleasure) | 0.863 | 0.011 |

| Question 1: Sadness | 0.805 | 0.037 |

| Question 2: Pessimism | 0.445 | 0.413 |

| Question 3: Past failure | 0.409 | 0.196 |

| Question 7: Thoughts or desires of suicide | − 0.206 | 0.729 |

| Question 5: Self-dislike | 0.272 | 0.727 |

| Question 6: Self-criticalness | 0.388 | 0.542 |

| Percent of the explained variance | 34.29% | 16.98% |

| Eigenvalues | 2.40 | 1.19 |

Exploratory factor analysis with varimax rotation.

Discussion

The primary objective of this study was to analyze the psychometric properties and validate the usefulness of the screening (PHQ-2) and diagnostic (BDI-FS-Fr) tests of depression on the CKD population sample of 109 French CKD patients. Depression is one of the most common psychological problems in this population. The present study demonstrates that the French version of the PHQ-2 and the BDI-FS-Fr have adequate psychometric characteristics to allow their use for CKD subjects with depressive disorders.

For the BDI-FS-Fr, the internal consistency (α = 0.668) is acceptable and is slightly lower than “α” Beck (α in the original study of Beck equal to 0.86 [19]). In a study by Healey et al. [35] on stroke survivors over 65 years old, Cronbach's α of the BDI-FS was equal to 0.75. Cronbach's α of the BDI-FS-Fr was equal to 0.74 with French students [9].

For convergent and divergent validity, the multiple correlations between depression scores and intensity of anxiety, satisfaction with life, and self-esteem are significant (p < 0.01). The PHQ-2 and BDI-FS-Fr are strongly correlated with the BDI-II. Thus, the correlation between the BDI-FS-Fr and other scales measuring depression (BDI-II and HADS) tells us that there is a significant link between the three measures (p < 0.001). In 1997, when Beck et al. [19], compared the BDI-FS with another standardized measure of depression, the BDI-FS was positively correlated at 0.62 and p < 0.001, demonstrating significant convergent validity [19]. According to the results, the PHQ-2 and the BDI-FS-Fr are sensitive and specific tests to measure depression compared with the BDI-II (the reference standard). The PHQ-2 and BDI-FS-Fr have satisfactory external structure validity. Regarding discriminant validity, the depressive patients had significantly higher scores than the nondepressive participants (p < 0.001).

The results of ROC and AUC are high and thus demonstrate that the PHQ-2 and the BDI-FS-Fr are reliable. In addition, the results of the screening characteristics and diagnostic tests (e.g., sensitivity, specificity, and diagnostics odds ratio) show that the PHQ-2 and BDI-FS-Fr are screening and diagnostics tools for depression in adult patients. According to Yule's Q coefficient, the intensity of the connection between the variables from the BDI-FS-Fr and BDI-II, as well as the PHQ-2 and BDI-II, is very strong. Finally, the diagnostic efficiency of the PHQ-2 and BDI-FS-Fr means that the results obtained in the test are good. In this study, the AUCs of the PHQ-2 and BDI-FS-Fr exceed 0.70. The ROC curve shows a good discrimination ability of the BDI-FS-Fr, which is compatible with the 2007 study by Golden et al. [36], as well as a good discrimination ability of the PHQ-2.

An exploratory factor analysis has identified two factors of BDI-FS-Fr. The validation of the French version of the BDI-FS-Fr with a sample of 109 patients shows a structure in two factors that does not correspond to what was proposed by Beck et al. [10] and by Alsaleh and Lebreuilly [8, 9], who indicated one factor in the structure in their study. In this study, the coefficients are greater than | 0.30 | and satisfactory.

In terms of applicability, the execution takes less time (±3 min for the two scales: PHQ-2 and BDI-FS-Fr) than the execution of other tools (15 min for the BDI-II and 10 min for the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale-21). Therefore, these two scales are not a burden for patients or for personnel to assess and are very easy.

Depression is treatable and is a very important factor for quality of life in CKD. Therefore, nephrologists must provide correct screening and diagnosis of depression while avoiding overlap with CKD symptoms. However, they have few opportunities to meet this challenge (avoiding false positive diagnoses and false negative diagnoses) during their routine consultation. To minimize false diagnoses, the two scales (PHQ-2 and BDI-FS-Fr) are useful for screening, diagnosis, and clinical trials. Nurses may be using these two scales, specifically the PHQ-2, to detect depression and alert physicians before confirmation of the diagnosis with BDI-FS-Fr.

Limitations and Future Research

As the BDI-II served as the gold standard, it would have been preferable to make a diagnosis of depression on the basis of DSM-V with a clinical interview.

Conclusions

The psychometric properties of the PHQ-2 and the BDI-FS-Fr (reliability, accuracy, and validity) are highly satisfactory. The results of this study suggest that the PHQ-2 and the BDI-FS-Fr are assessment tools for patients and can be useful for the evaluation of subjects with depressive disorders. This study provides strong evidence regarding the reliability of this quick questionnaire for the screening and diagnosis of depression.

Given the prevalence of depression in the population and the impact of the disease on the individual and social level, objective tools for measuring depression are important for therapeutic management and optimal clinical monitoring.

Finally, this study is the first to confirm the internal and external validity of the questionnaire and attests to its relevance in a French population with CKD.

Statement of Ethics

This study was approved by the Patient Protection Committee (CPP: Comité de Protection des Personnes Nord-Ouest III) in University Hospital of Caen. The human ethics committee approved the protocol on May 10, 2016 (No.: Réf. CPP: A17-D02-VOL.31). All participants in this study signed a consent form.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Neitzer A, Sun S, Doss S, Moran J, Schiller B. Beck Depression Inventory-Fast Screen (BDI-FS): an efficient tool for depression screening in patients with end-stage renal disease. Hemodial Int. 2012 Apr;16((2)):207–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-4758.2012.00663.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hackett ML, Jardine MJ. We Need to Talk about Depression and Dialysis: but What Questions Should We Ask, and Does Anyone Know the Answers? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017 Feb;12((2)):222–4. doi: 10.2215/CJN.13031216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Untas A, Aguirrezabal M, Chauveau P, Leguen E, Combe C, Rascle N. [Anxiety and depression in hemodialysis: validation of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)] Nephrol Ther. 2009 Jun;5((3)):193–200. doi: 10.1016/j.nephro.2009.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hedayati SS, Bosworth HB, Briley LP, Sloane RJ, Pieper CF, Kimmel PL, et al. Death or hospitalization of patients on chronic hemodialysis is associated with a physician-based diagnosis of depression. Kidney Int. 2008 Oct;74((7)):930–6. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Riezebos RK, Nauta KJ, Honig A, Dekker FW, Siegert CE. The association of depressive symptoms with survival in a Dutch cohort of patients with end-stage renal disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010 Jan;25((1)):231–6. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfp383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McKercher C, Sanderson K, Jose MD. Psychosocial factors in people with chronic kidney disease prior to renal replacement therapy. Nephrology (Carlton) 2013 Sep;18((9)):585–91. doi: 10.1111/nep.12138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feinstein A. Multiple sclerosis and depression. Mult Scler. 2011 Nov;17((11)):1276–81. doi: 10.1177/1352458511417835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alsaleh M. Analyse psychosociale et cognitive de la santé mentale chez les étudiants de première année: - Validation du questionnaire des pensées positives et négatives et du questionnaire de la dépression de Beck; - Effet des pensées positives et des facteurs psychosociaux. Thèse-Ecole Doctorale 556-CERReV; Laboratoire du CERReV (EA 3918), Université de Caen Normandie: 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alsaleh M, Lebreuilly R. Validation of the French translation of a short questionnaire Beck Depression (BDI-FS-Fr) AMPSY. 2017;175((7)):608–16. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. BDI-Fast Screen for medical patients. San Antonio (TX): Pearson; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders. Patient Health Questionnaire. JAMA. 1999 Nov;282((18)):1737–44. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.18.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: validity of a two-item depression screener. Med Care. 2003 Nov;41((11)):1284–92. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000093487.78664.3C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mohr DC, Hart SL, Julian L, Tasch ES. Screening for depression among patients with multiple sclerosis: two questions may be enough. Mult Scler. 2007 Mar;13((2)):215–9. doi: 10.1177/1352458506070926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lebrun C, Cohen M. [Depression in multiple sclerosis] Rev Neurol (Paris) 2009 Mar;165(Suppl 4):S156–62. doi: 10.1016/S0035-3787(09)72128-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fragoso YD, Adoni T, Anacleto A, da Gama PD, Goncalves MV, Matta AP, et al. Recommendations on diagnosis and treatment of depression in patients with multiple sclerosis. Pract Neurol. 2014 Aug;14((4)):206–9. doi: 10.1136/practneurol-2013-000735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cohen J. 2nd ed. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1988. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Skelly AC, Dettori JR, Brodt ED. Assessing bias: the importance of considering confounding. Evid Based Spine Care J. 2012 Feb;3((1)):9–12. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1298595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shamsuddin K, Fadzil F, Ismail WS, Shah SA, Omar K, Muhammad NA, et al. Correlates of depression, anxiety and stress among Malaysian university students. Asian J Psychiatr. 2013 Aug;6((4)):318–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2013.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beck AT, Guth D, Steer RA, Ball R. Screening for major depression disorders in medical inpatients with the Beck Depression Inventory for Primary Care. Behav Res Ther. 1997 Aug;35((8)):785–91. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(97)00025-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang YP, Gorenstein C. Assessment of depression in medical patients: a systematic review of the utility of the Beck Depression Inventory-II. Clinics (São Paulo) 2013 Sep;68((9)):1274–87. doi: 10.6061/clinics/2013(09)15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Craven JL, Rodin GM, Littlefield C. The Beck Depression Inventory as a screening device for major depression in renal dialysis patients. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1988;18((4)):365–74. doi: 10.2190/m1tx-v1ej-e43l-rklf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Watnick S, Wang PL, Demadura T, Ganzini L. Validation of 2 depression screening tools in dialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005 Nov;46((5)):919–24. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2005.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hedayati SS, Bosworth HB, Kuchibhatla M, Kimmel PL, Szczech LA. The predictive value of self-report scales compared with physician diagnosis of depression in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2006 May;69((9)):1662–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cohen SD, Norris L, Acquaviva K, Peterson RA, Kimmel PL. Screening, diagnosis, and treatment of depression in patients with end-stage renal disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007 Nov;2((6)):1332–42. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03951106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Poole H, White S, Blake C, Murphy P, Bramwell R. Depression in chronic pain patients: prevalence and measurement. Pain Pract. 2009 May-Jun;9((3)):173–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-2500.2009.00274.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory Second Edition (BDI-II) San Antonio: Psychological Corp: 1996 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Steer RA, Cavalieri TA, Leonard DM, Beck AT. Use of the Beck Depression Inventory for Primary Care to screen for major depression disorders. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1999 Mar-Apr;21((2)):106–11. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(98)00070-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rosenberg M. Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton (NJ): Princeton University Press; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Diener E, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, Griffin S. The Satisfaction With Life Scale. J Pers Assess. 1985 Feb;49((1)):71–5. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smith SC, Lamping DL, Banerjee S, Harwood R, Foley B, Smith P, et al. Measurement of health-related quality of life for people with dementia: development of a new instrument (DEMQOL) and an evaluation of current methodology. Health Technol Assess. 2005 Mar;9((10)):1–93. doi: 10.3310/hta9100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pina AA, Silverman WK, Alfano CA, Saavedra LM. Diagnostic efficiency of symptoms in the diagnosis of DSM-IV: generalized anxiety disorder in youth. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2002 Oct;43((7)):959–67. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Swets JA. Measuring the accuracy of diagnostic systems. Science. 1988 Jun;240((4857)):1285–93. doi: 10.1126/science.3287615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nendaz MR, Perrier A. [Bayes theorem and likelihood ratios] Rev Mal Respir. 2004 Apr;21((2 Pt 1)):394–7. doi: 10.1016/s0761-8425(04)71301-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Law M, Naughton MT, Dhar A, Barton D, Dabscheck E. Validation of two depression screening instruments in a sleep disorders clinic. J Clin Sleep Med. 2014 Jun;10((6)):683–8. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.3802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Healey AK, Kneebone II, Carroll M, Anderson SJ. A preliminary investigation of the reliability and validity of the Brief Assessment Schedule Depression Cards and the Beck Depression Inventory-Fast Screen to screen for depression in older stroke survivors. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008 May;23((5)):531–6. doi: 10.1002/gps.1933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Golden J, Conroy RM, O'Dwyer AM. Reliability and validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale and the Beck Depression Inventory (full and FastScreen scales) in detecting depression in persons with hepatitis C. J Affect Disord. 2007 Jun;100((1-3)):265–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]