Summary

With increasing childhood obesity rates and type 2 diabetes developing in younger age groups, many schools have initiated policies to support healthy eating and active living. Policy interventions can influence not only health behaviours in students but can also impact these behaviours beyond the school walls into the community. We articulate a policy story that emerged during the data collection phase of a study focused on building knowledge and capacity to support healthy eating and active living policy options in a small hamlet located in the Canadian Arctic. The policy processes of a local school food policy to address unhealthy eating are discussed. Through 14 interviews, decision makers, policy influencers and health practitioners described a policy process, retrospectively, including facilitators and barriers to adopting and implementing policy. A number of key activities facilitated the successful policy implementation process and the building of a critical mass to support healthy eating and active living in the community. A key contextual factor in school food policies in the Arctic is the influence of traditional (country) foods. This study is the first to provide an in-depth examination of the implementation of a food policy in a Canadian Arctic school. Recommendations are offered to inform intervention research and guide a food policy implementation process in a school environment facing similar issues.

Keywords: school health, food policy, healthy eating, policy adoption and implementation, Arctic

INTRODUCTION

Schools are an ideal setting to influence students’ behaviour, well-being and academic performance due to the number of hours students spend there (Holland et al., 2016). Viewed through a socio-cultural lens (Vygotsky, 1978), schools are not only a place of learning but also a space in which new sociocultural norms are created, social capital is gained and lost through interactions with peers and youth gain exposure to many different family practices such as food choices. For many children certain kinds of food become ‘cool’ and being associated with ‘cool’ food may mean acquiring social capital among new groups of peers. One way of disrupting and changing children’s’ eating habits is through implementing school food policy. Policy implementation facilitates the conscious creation of a complex supportive environment and influences behaviour that goes well beyond the school walls to ripple out into multiple spheres.

In Canadian Arctic Indigenous communities, local schools are challenged to support healthy culturally adapted foods. Geography, climate and changes to cultural traditions have led to a decrease in accessing and consuming traditional foods. As a result, there is now more of a dependency on commercial foods sold in local community stores (Gracey and King, 2009). These foods tend to consist of non-perishable or energy-dense, and nutrient-poor food (potato chips, biscuits, cakes, chocolate, cookies) and sugar-sweetened beverages (sweetened juices with added sugar, energy drinks, sports drinks, pop, ‘slushies’) (Sheehy et al., 2013), which tend to be ‘inexpensive, good tasting and convenient’ [(Drewnowski and Darmon, 2005), p. 266S]. Consequently, children in these Arctic communities have greater access to energy-dense and nutrient-poor foods. With increasing childhood obesity rates and type 2 diabetes developing in younger age groups, many schools in Canada are implementing school food policies to support healthy eating by reducing unhealthy food intake during school hours (Cargo et al., 2006). [For the purpose of this article, unhealthy food is defined as any food or drink high in calories, fat, sugar or salt (Health Canada, 2007).]

In this article, we articulate a school food policy story based on a qualitative study from a kindergarten to grade 12 public school located in the Canadian Arctic. A story is a way of knowing and capturing the nuances and richness of human experience that may otherwise go unknown (Shkedi, 2005). Stories are also a way to communicate to policy makers, researchers and practitioners the results, successes, lessons learned and challenges of policy change that engage the reader in recognizing patterns similar to our own experiences. Policy adoption is understood to be the decision to use a policy (Rogers, 2003). We refer to implementation as the extent to which a policy is applied as intended or implemented with fidelity and maintenance as ‘the extent to which a program or policy becomes institutionalized or part of the routine organizational practices and policies’ [(Jilcott et al., 2007), p. 106]. To date, there has been no in-depth examination of how local school level policies addressing food environments are being implemented or maintained within the context of Indigenous communities. We outline a number of recommendations for successful policy implementation in other Indigenous contexts that are facing similar concerns and may benefit from the policy story articulating the process of adoption to implementation to maintenance. The local school food policy was named a ‘Junk Food Policy’, which represents the way in which community members viewed and discussed unhealthy food products.

CURRENT STUDY

Methods

The policy story is drawn from an exploratory case study that was conducted during November 2015 to August 2016 in Aklavik, Northwest Territories (NT), an isolated community of approximately 600 people in the Canadian Arctic. The overall purpose of the study was to build knowledge and capacity to support policy interventions related to healthy eating and active living. The research question that guided the development of the policy story was: What are the stories from decision makers, policy influencers and health practitioners in Aklavik about their experiences in the policy process related to healthy eating and active living? The primary focus of this case study is to articulate the actions taken that facilitate the successful implementation and maintenance of the school food policy for policy learning.

Participants

Fourteen participants were recruited through purposeful sampling based on the principle of obtaining different functional perspectives on the subject of healthy eating and active living policy adoption and implementation. From the fourteen participants, four participants had in-depth knowledge of the school food policy and as a result, the researchers focused more specific questions with each of these four participants exploring the formulation, adoption, implementation and maintenance of the policy. Inclusion criteria for our study were persons in a position to influence the policy environment, and/or who have been employed as a senior administrator (policy advisor, decision maker, manager) in the community for a minimum of one year.

Procedure and interviews

A list of potential participants was generated based on criteria developed with the local co-researcher. The co-researcher was a ‘cultural guide’ (Roe et al., 1995) who advised on the best approach to contact individuals in leadership positions in a respectful way and in accordance with local cultural practices. Individuals were invited to participate in a single in-depth face-to-face 30–60-min interview. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim by the first author. The initial interview questions were broad exploring the types of health issues they see in their community and how the health issue is being addressed or should be addressed in their community. Questions then focused on existing policies in their community that are helping to prevent the identified health issues (in the previous question). It was during this stage in the interviews were the policy story emerged regarding how the local school had implemented a school food policy that they described as a ‘junk food policy’ was adopted, implemented and has been maintained for more than a decade. As the policy story developed through the interviews, the research team also contacted the school principal to provide further details regarding the implementation of the policy. Since Moose Kerr School (in Aklavik) was the first school in the Beaufort Delta School District with such a policy and it has remained in effect for almost 15 years, we were interested in learning about the process of implementing and maintaining a school food policy as the case study. For the purposes of anonymity and to uphold confidentiality among participants in this small community, neither individuals nor their roles are identified in the citations that offer evidence for the policy story.

Data analysis

Data were analysed using matrix methodology described by Miles and Huberman. Data analysis flowed from two analytical processes: data reduction, and conclusion drawing and verification (Miles and Huberman, 1994). Data reduction, a process to focus and simplify the data, occurred through written summaries of meetings between the two field researchers as well as field notes, and through a coding process iteratively constructed from the raw data of the interviews. Conclusion drawing and verification occurred throughout the analysis. Following this process, we began to focus on the policy story that was emerging regarding the ‘Junk Food Policy’ at the local school regarding the adoption, implementation and maintenance of the policy.

Context

Between the months of November and April each year, residents of Aklavik and companies operating in the North rely on winter roads to bring food into the community via trucks. In the warmer months between May and October, the only options for food delivery are by air or shipping container via the Arctic waterways. Geography therefore dictates accessibility to, and availability of, food and as a result food affordability. Distance of travel, seasonal availability and quantity of species (Simoneau and Receveur, 2000), lack of time for hunting due to increased involvement in the wage economy, high cost of hunting equipment, ammunition and fuel, a decline in communal food sharing networks (Sharma, 2010) and colonization (Power, 2008) have all been reported as factors that have led to a decrease in the consumption of traditional foods in the Arctic communities.

Moose Kerr School

Moose Kerr School is a kindergarten to grade 12 school, with a student population of 161 pupils and a teaching complement of seven local Indigenous staff and seven Southern staff (South or Southern refers to anyone south of Yellowknife, NT, usually indicating a non-Indigenous person.). In 2002 when the ‘junk food policy’ was implemented, the school had a student population of 225 pupils and a staff of 15 teachers, 4 support staff and 2 local Indigenous language instructors comprising 50% Indigenous teaching staff and support staff and 50% Southern teaching staff Indigenous. Teachers from the South work on 2- to 5-year contracts and leave during the summer vacation while the Indigenous staff members are from the local community. Historically, the school principal came from the South on a two-year contract. However, this practice changed in 1999 when the current principal took on the role. The school participates in a breakfast and snack program that includes healthy food through Food First Foundation a nationally registered charity focusing on supporting nutrition education programs in the Canadian Arctic region. They also have a very active after school program that includes physical activity such as basketball and volleyball.

RESULTS

Policy formulation and adoption

In 2002, Moose Kerr School implemented a comprehensive ban on unhealthy food. Interviewees in the study, reflecting on the previous 15 years, recalled that teachers observed behaviour differences between the students who did and did not consume unhealthy food. Interviewees recounted teachers stating that children were not able to focus, and had mood swings, jitteriness and poor academic performance. As reported by one interviewee, ‘the teachers connected these behaviours to sugar as they observed students on a daily basis, while on the school grounds, consuming large amounts of sugar sweetened beverages in the form of “slushies” and Gatorade and eating large amounts of candy’. Similarly, another interviewee reflecting on student behaviour stated, ‘the students who did not consume these food products did not have the same behavioural or performance issues’. Upon witnessing students consuming unhealthy food and beverages and connecting behavioural and performance issues in the classroom, the teaching staff brought forward their concerns to the principal at a staff meeting and worked as a collective to address these issues. One interviewee articulated the impetus for the policy:

Staff over several staff meetings brought up the concern of student’s inattentiveness, and unfocused attention after the recess break or shortly after lunch hour when consuming sugary foods or junk food. The staff saw a direct co-relation to when students consumed and didn’t consume sugary food or junk food.

Teachers’ concerns not only centred on the educational impact but also on the social and economic impact that consuming unhealthy products had on children in school. The teachers and staff continued to meet over several weeks to discuss how best to address the consumption of unhealthy food. Concerned staff decided that they would address the issue with a ‘Junk Food Policy’.

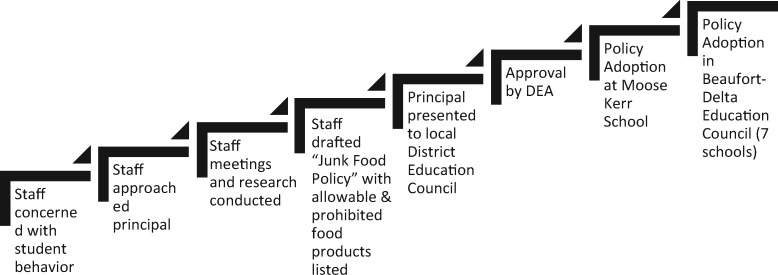

Once the connection between the consumption of sugar and the behavioural and performance issues was identified at the school level, the principal took the concerns of the teachers to the local District Education Authority (DEA) for consideration. A number of presentations were conducted for the local DEA about the proposed policy option. Raising awareness among the local DEA board members about the health and learning issues was a key activity that helped push the policy idea into adoption. The local DEA supported the adoption of the policy at Moose Kerr School, which lead to the diffusion of the policy to other schools in the Beaufort Delta Region. The policy that was adopted in 2002 included a list of permitted and prohibited food and beverages. The steps to policy adoption have been articulated in Figure 1.

Fig. 1:

Steps to policy adoption. This figure illustrates the process taken to formally adopt the food policy at Moose Kerr School.

Policy implementation

While the teachers were engaged in creating the ‘Junk Food Policy’, they also were key actors in the implementation process of the policy. As the policy was being implemented, regular staff meetings occurred to discuss emerging issues and solutions. Following implementation, the meetings also served as a place to discuss how the policy was being enforced and to resolve issues with compliance. According to Smit ‘how policy is viewed, understood, and experienced only becomes real when teachers attempt to implement policy’ [(Smit, 2005), p. 298].

Once the policy was formally adopted, teachers realized the students would need time to adjust socially and psychologically to the change before pushing the policy into full effect. At a staff meeting, teachers decided a 4-month transition period was needed in which parameters were placed around the policy. First, staff agreed it would be best to start with a policy that would not directly say ‘junk food was banned’. While the list of acceptable and prohibited food and beverages was included in the policy, teachers believed that allowing some unhealthy food at events or activities would support the policy implementation process.

We put some parameters around what events or activities would be unacceptable and acceptable. For example, although junk food was banned from the classroom, it would be allowed if there was a classroom party.

In some way, the result of modifying the policy during the 4-month transition time was a harm reduction approach that did not rigidly prohibit unhealthy food but allowed for some instances when it would be allowed. As well, alternative food choices that are still considered unhealthy but with less sugar (e.g. granola bar) were also allowed during the transition time. Additionally, during the transition time, enforcement strategies were less severe compared to when the policy was fully implemented. One interviewee stated:

We provided student warnings and would hold junk food until students were dismissed and the junk food returned. Parents were also called. After four months, students were made aware that the junk food would be confiscated and thrown out.

However, there was still push back from junior and senior high students during the transition time. ‘The older students were buying slushies and pop because they wanted something outside of water to drink. So it was agreed to allow some approved drinks even though they might be high in sugar at the outset’.

During the implementation process a concerted effort was made to ensure students and families were aware of the policy. Presentations by the principal and the DEA secretary occurred in each classroom to discuss the new policy and provide time for questions. Analogy was used to help the students understand the reasons for the policy.

I reference community signs like a stop sign and their meaning to help students understand that school rules are similar to a stop sign that they exist for safety and protection. I would say “We need you to be here as a good learner. And too much sugar is not being a good learner. The junk food policy is to help us be more focused/concentrated on the important things about school like learning and paying attention daily.

However, at the secondary level a different approach was needed. While presentations still continued in junior and senior high, the policy needed to be modified to support student buy-in. ‘The first step with the high school students was to allow some “approved” beverages even though they might have been high in sugar’. In conjunction with classroom presentations, communication to families and the broader community occurred through newsletters distributed over several months prior to and during the implementation of the policy. These newsletters provided background information about why the policy was being implemented and what would change as a result. ‘Surprisingly a lot of support came from parents especially those in Kindergarten to grade five as they felt it was a positive message to give our students in terms of living a healthier lifestyle’. However, as many community members spoke their local language, opportunities to discuss the new policy with parents face to face were also given for those who could not read English or their local language. Parents were given the opportunity to ask questions and to express their perspective about the policy. Support from parents with children in the higher grades evolved over time. Now that the policy has been implemented for more than a decade:

Our parents/guardians now understand that when it comes to our annual classroom parties, parents are providing healthier varieties of food. This indicates to us a solid buy in from parents and shows respect to the school for the effort to make their child/children’s lives a bit healthier in terms of what is acceptable food at these types of events.

Once the policy was in full effect (post 4-month transition), the push back from the older students continued. ‘They would be defiant in terms of making efforts to bring in junk food into the school/class. They would also stay outdoors and be purposely late to class because they wanted to finish their junk food before entering through the school doors’. However, enforcement was consistent with issuing reminders, confiscating the unhealthy food or beverages and calling parents when students violated the policy. ‘For the most part parents were understanding and put the responsibility back on their child’. Partnerships with local stakeholders were key in countering the push back from students.

The number of students engaged in the consumption or breaking the junk food policy has decreased over time due to a number of partnerships. The Community Health Representative, school counsellor and teachers along with our school wide support with March Nutrition month, November Diabetes month and the annual Drop the Pop campaign have provided students with health information.

Changes to the policy have become a necessity as new evidence regarding sugar has surfaced and been discussed during staff meetings. For example, at one of their regular staff meetings the prohibited food list was reviewed and ‘teachers identified high sugar content in juice so decided to switch to milk’. The essence of the policy has remained constant over time, and yet adaptable and responsive to new knowledge about unhealthy foods.

Maintenance of the policy

Sustaining the food policy for more than a decade has come about through the process of building a critical mass. A critical mass is developed when a majority of people believe in a new idea, innovation or change, make the change or adopt the new idea and influence others to make the change (Rogers, 2003). As the critical mass is established, a new norm is created and in this sense we observe, experience and eventually can measure social change (Rogers, 2003). However, in order to create a critical mass, actions taken at the school level alone are not enough to sustain the food policy. Increasing the sphere of influence of the policy is required, so that a new norm of healthy eating beyond the school walls to the broader community is created. Multiple actions taken concurrently with a variety of stakeholder groups between Moose Kerr School and the community have facilitated the building of the critical mass. Key actions have included working with community partners, working with the neighbourhood store manager, enforcing the policy after hours with community groups and acquiring a food vending machine containing ‘healthier’ food such as granola bars, crackers, pretzels, Sun Chips (depending on availability at the local store). These actions are embedded within a complex network of stakeholder groups and reflects relational aspects about the school.

Working with community partners

The partnership between the school, the community health representative (CHR) and the NT’s Department of Health and Social Services facilitated the maintenance of the food policy through support and encouragement for healthy lifestyles.

We've got good partnerships with the CHR. She comes to the school often and teaches the students about diabetes so that's right in their face about health. It opens their eyes to their own self care. Also participating in the NT’s yearly ‘Drop the Pop’ campaign works together to support the no junk food policy and reinforces the importance of the policy.

The community partnerships have supported the efforts of the school by getting the same message out to students, parents and the community, reinforcing the value of making healthier choices in all areas of their lives and benefiting everyone collectively. ‘My daughter came home one day from school and told me I needed to stop drinking pop, that it was bad for my health. I participated in not drinking pop for one month. Since then I have decreased the amount of pop I drink since that time’.

Working with the neighbourhood store manager

Across the street from the school stands one of two local stores. During the initial implementation of the junk food policy the store manager was asked not to sell extra-large-sized drinks (‘slushies’), energy drinks and anything else on the ‘junk food’ policy list. The initial reaction from the manager reinforced the store’s place as a profit-making business. However, when the manager learned how the high amounts of sugar influenced student behaviour and lowered learning capacity there was more willingness to become a partner. The manager at the time agreed and supported student learning in a positive light. He understood that there would still be profit but over a more controlled time span for the benefit of the students, that is, the policy would only apply during school hours and students could resort to buying the same unhealthy products after school. While healthier options in the store have always been seasonally available and transport dependant, students continued to purchase snacks high in sugar and fat. There was also a lot of push back from families who believed that the store should not limit what was sold to their daughter or son. As a result, the store manager directed store staff to inform students about the restriction applied during school hours. If students appeared in the store and attempt to purchase anything on the no junk food list, the store clerks tell the children that during school hours they cannot buy junk food.

There have been changes in managers over the years but they still support the initiative and don’t sell junk food during school hours. This is a long term relationship with the store and it is getting the manager on side as they change over. I have the deepest appreciation for this partnership’s support to help make the junk food policy a success in Aklavik.

Reflected in this quote is the significant impact of the store managers’ behaviour—it may also have to change to help support the well-established junk food policy at the school.

Enforcing the policy during evening hours

As a result of implementing the no junk food policy in the school, community members or organizations using the gymnasium in the evening also were required to support the ‘Junk Food Policy’. An agreement must be signed that commits users to follow the policy.

The junk food policy has to be followed. So we're even trying to impress that message on the community members as well, not just our students but everybody. For the most part the community does do their part and it makes us feel good as a school to get their support.

Having the policy implemented after hours not only has supported the policy generally but also indirectly has raised awareness in the community about unhealthy food. ‘It sends a very strong message about junk food acceptance.’

Acquiring a healthy food vending machine

Having a vending machine that is stocked with healthier food choices on site has not only eased staffing logistics required when the school had a canteen but also has provided better accessibility to the student body, the staff and the public at large who use the gym during evening hours.

The implementation of a vending machine was on the fence for quite some time, but when the decision was made to go ahead the food choices were healthier ones. The students overall have been very receptive to this. So it is better to see our students eating a bag of pretzels versus a bag of potato chips.

Contextual considerations: country foods

While there were a number of actions that facilitated the implementation of the policy and rippled out into the community, an important contextual factor in the policy story is the influence of country foods in the school (Inuit often use the term country food while, for example Dene use the term traditional food. For consistency, we use the term country food.). Country food is defined as mammals, fish, plants, berries and waterfowl or seabirds that are harvested from the local environment for consumption (Van Oostdam et al., 2005). Country food is more nutritious and nutrient-dense than market food, and remains important to the quality of the diets of many Indigenous people (Earle, 2011). While not officially part of the policy, the students learn about country foods by going on the land to hunt, trap, fish and harvest. Students learn how to skin, dry, preserve and cook their harvest. The children also assist in preparing and eating what they harvest. Creating and supporting opportunities for country food knowledge sharing and protection (hunting, harvesting, cooking) among school children are necessary cultural activities.

You put a granola bar and traditional food in front of them and they'll take the traditional food. So we try to have a little bit of a mixture of everything where we can and that's pretty good. Like when we came back in September, fish sticks [dried fish that has been cut into long sticks] are a popular thing. It's nice to have that and the kids thoroughly enjoy eating them and it’s nice to see them eat it with enthusiasm for this country food. You know you're on the right track when kids start to gobble that kind of stuff up.

Transferring traditional knowledge to younger generations about country food harvesting and cooking as part of the learning environment encourages a lifelong habit of healthy eating and active living. One of the current challenges regarding supporting the school food policy relates to funding country food harvesting, hunting and trapping. Moose Kerr School has a strong ‘On the Land’ program that has been in place for many years. However, expanding the program within the curriculum requires sustainable financial resources, as the funding comes from the NT’s government for limited periods.

We want to focus on bridging cultural learning with our school by having our own cultural site on the school grounds. This way students can be exposed to the culturalteachings through hands on experience. There would be tangible opportunities for them to retain the harvest, give it away or use it for school luncheons later in the year. This is one initiative that is still in planning stages and would require community support, input and financial resources to bring this to fruition.

Reflected in this quote is a desire for the school to become self-sufficient so that students can engage in activities such as going down to the local river system, setting a fish net and harvesting their own fish. Becoming self-sufficient is a future opportunity that with sustained funding, is possible. Building partnerships with On the Land programs can also facilitate building a critical mass.

DISCUSSION

The implementation of school food policies is a promising intervention that helps to create a supportive environment to promote the health of students and, with multiple actions taken simultaneously with a network of stakeholders, builds a critical mass in the broader community. Additionally, articulating the relational aspects of the networks provides insight into how the networks’ structure and function support the school food policy. Our study contributes to understanding the process of implementation and maintenance through sharing the policy story and is one of the first to be conveyed from within an Indigenous school. The transferability of policy initiatives such as this is often difficult given the context of local conditions.

Given that the policy was adopted 15 years ago, prior to any other such policies existing within the school district or in the Territory, the policy is a testament to being a successful innovation. The adoption and implementation of the junk food policy to address unhealthy eating is considered an innovation. At the time of policy adoption, 15 years ago, a program to educate students about unhealthy eating would have been the response to unhealthy eating with the assumption that if people know what to do they will act appropriately (i.e. to eat healthy). The focus on policy action at the time reflects an innovative approach in and of itself and reflects a learning organization approach. Rosa defines a learning organization as one where it is advantageous for its’ members to ‘make mistakes, take risks, acquire, share new knowledge, participate and continuous evaluation occurs’ [(Rosa, 2017), p. 308]. As a learning organization, Moose Kerr School adapted within a complex system of networks to support student health.

The implementation process at Moose Kerr School also included multiple actions that occurred simultaneously with a variety of stakeholder groups that have supported the success and facilitated sustaining the policy since 2002. The school and the community have a dynamic interconnection. Something that happens in the school influences the community and vice versa. As a result, momentum has built within the community to recognize the value of healthy food, including country food, and consequently changing the norm of consuming unhealthy food. For example, as a result of students bringing home the school handbook where the policy is provided for parents to read, discussing what they are learning in school regarding unhealthy food, the link to disease, and having access to information in the newsletters have the potential to change the behaviour of their parents. Additionally, community groups agreeing not to bring unhealthy food while using the school gym, and having a healthier food options in the vending machine that is accessible during and after school hours, also collectively, have the potential to change the behaviour of the community at large. As more people begin to discuss what is happening at the school around healthy food and more people become aware of the negative effects of unhealthy food, change can happen. It was reported by one participant that healthier and country foods are being provided at local community events. The adoption of the school food policy at a time when evidence was only emerging about the negative health effects of sugar on the health of children reflects a deep commitment by the school administration to promote student health and wellbeing. While many school districts within the NT have since adopted similar policies, the policy has not become a territory wide policy within the Government Department of Education, Culture and Employment. Participants reported that policy diffusion has been limited to the local levels.

RECOMMENDATIONS

There are several lessons that we learned in this policy story and extrapolation of the findings might be useful for policy makers elsewhere. We make four recommendations that can be used to develop a practical policy tool kit for healthy school food policy interventions in other Northern Canadian Indigenous contexts with similar concerns. First, building human resource capacity within Northern Canadian communities to provide local teaching staff is needed to ensure continuity, sustainability and cultural relevance of policies that support student learning and enhance student health. As can be seen from the policy story, leadership was key in the sustainability of the ‘Junk Food Policy’ at Moose Kerr School. In many Canadian Arctic settings, it is common to hire staff from the South to work on a contract basis. However, temporary contract-based work can lead to new policies being implemented or existing policies being eliminated as new staff bring their own agendas, do not know the history of initiatives or practices and have not developed relationships within the community. Building trust within and outside the school walls is needed when implementing policy especially when it changes a deeply rooted and long-term practice such as consuming unhealthy food and beverages.

Second, communication through multiple channels is needed to build a critical mass. Students, their families and staff all became aware of the change through classroom presentations, newsletters and frequent meetings. Additionally, the community members wishing to use the school after hours also became aware of the change when they were asked to sign a contract and agree to the school policy in order to use the facilities. Multiple communication strategies targeting multiple stakeholders implemented throughout the change period help build the necessary critical mass. Additionally, continual communication is required to keep the purpose and information of the policy at the forefront of student, parents and teacher’s minds.

Third, developing multi-sectoral partnerships are important to support the school food policy in various ways. Engaging health practitioners to provide information and raise the awareness of the health effects of unhealthy eating and the subsequent diseases can provide the students with sound knowledge to make healthier choices in their lives. Engaging local businesses such as the neighbourhood store is also recommended. Having the store implement parameters around the sale of unhealthy food and beverages sends an important message to students that consuming these products does not support their learning during school hours and sends a strong message home to parents about unhealthy food.

Fourth, providing a transition period is valuable to gain expanding support for the initiative and to address issues as these emerge with policy implementation. One of the successful strategies from the policy story was using a phased in approach to policy implementation that provided a 4-month transition period before pushing the policy into full effect. The transition period provided time to raise awareness of the policy change within the student population and their families through enforcement strategies such as warnings. It also provided time to make changes to the policy content, to help the administration decide how it would implement it for the various grade levels, and for student issues to surface and be addressed.

Future research is needed to understand the impact of incorporating country foods into the school setting through on the land programs on student learning, healthy behaviours and physical activity levels. This type of research would provide evidence to formalize policy confidently. On the land programs encourage students to return to their cultural roots, learning the values, beliefs, traditional ways of their Elders and shaping for themselves modern Indigenous ways. However, extensive funding is required to support on the land programs, as expenses related to hunting and equipment for fishing and hunting are now cost prohibitive for schools. It is well documented that dietary behaviours established in childhood generally continue into adulthood (Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, 1996), so exposing children early onto country foods and encouraging them to adopt healthy eating patterns may contribute to healthier dietary choices in the future. Future research could also include the impact of the school food policy on the behaviour of community members regarding consuming healthy food.

Limitations

This study took place in one community in the NT, thus limiting the data sample to a specific community. Consequently, the findings reflect the perspectives of a group of decision makers and policy influencers in one small community. These limitations do not allow for generalizable conclusions about how decision makers and policy influencers from other communities in NT feel about policy and policy interventions to support healthy eating and active living. However, study findings can inform reflection and examination in other jurisdictions. Another limitation is that interviews were retrospective, and recall about the implementation of the food policy processes may not be as accurate as recall about more recent changes to the policy. Additionally, as the policy was developed to address specific issues with students (behavioural and performance related) and was not implemented with evaluation in mind, assessing effectiveness retrospectively is challenging. This limitation highlights the need for future prospective research about policy development and implementation processes.

CONCLUDING THOUGHTS

In our case study, through the policy story, we have demonstrated how a local school food policy to support healthy eating was implemented and maintained during the last 15 years. The policy story at Moose Kerr School identified key factors that facilitated action to make changes to the school food environment. Using a phased-in approach to policy implementation, which included enforcement, helped to minimize barriers to effective policy implementation. Implementing the food policy changed the products available at the school store canteen, eliminated unhealthy foods from entering the school, created a list of prohibited food and beverages and created an opportunity to obtain a vending machine that contained only healthy food. Policy sustainability has been supported over time by students taking responsibility for policy adherence and compliance. Policy sustainability, however, also may be threatened over time; it may be rescinded for various reasons, and need updating as new scientific evidence emerges (Jilcott et al., 2007).

Overall, the sustained effort of policy maintenance has resulted in a more supportive learning environment for students. The longevity of the policy has created a student population that knows why they are not allowed to bring junk food to school. Not only has academic performance and behaviour improved in the classroom, but dietary behaviour has also changed. The cultural learning around hunting, fishing, trapping, and harvesting country food has supported the policy by encouraging snacking on these foods during school hours. The impact of the food policy has been far reaching; educating a generation of children in health and healthy living, building a critical mass in the community to support healthy eating and changing social norms.

FUNDING

This work was supported by the Canadian Institute of Health Research (CIHR) Training Grant in Population Intervention for Chronic Disease Prevention: A Pan-Canadian Program. Grant Number 53893, Northern Scientific Training Program (NSTP) Grant, Health Canada, and the University of Alberta Northern Research Awards (UANRA) Grant.

ETHICS APPROVAL

The study obtained ethics approval from the University of Alberta Health Research Ethics Board and a Scientific Research Licence under the Northwest Territories Scientists Act.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thank you to all the participants, co-researcher Janeta Pascal, Senior Administrative Officer Fred Beherens, Mayor Charlie Furlong for their support during the project.

REFERENCES

- Cargo M., Salsberg J., Delormier T., Desrosiers S., Macaulay A. C. (2006) Understanding the social context of school health promotion program implementation. Health Education, 106, 85–97. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (1996) Guidelines for school health programs to promote lifelong healthy eating. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 45, 1–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drewnowski A., Darmon N. (2005) The economics of obesity: dietary energy density and energy cost. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 82, 265S–273S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earle L. (2011). Traditional Aboriginal Diets and Health https://www.ccnsa-nccah.ca/495/Traditional_Aboriginal_diets_and_health_.nccah?id=44 (30 May 2018, date last accessed).

- Gracey M., King M. (2009) Indigenous health part 1: determinants and disease patterns. The Lancet, 374, 65–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health Canada. (2007) Foods to Limit. Retrieved from: http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/fn-an/food-guide-aliment/maintain-adopt/limit-eng.php (30 May 2018, date last accessed).

- Holland J. H., Green J. J., Alexander L., Phillips M. (2016) School health policies: evidenced-based programs for policy implementation. Journal of Policy Practice, 15, 314–332. [Google Scholar]

- Jilcott S., Ammerman A., Sommers J., Glasgow R. E. (2007) Applying the RE-AIM framework to assess the public health impact of policy change. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 34, 105–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles M. B., Huberman A. M. (1994) Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook. Sage: New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Power E. M. (2008) Conceptualizing food security for Aboriginal people in Canada. Canadian Journal of Public Health/Revue Canadienne De Sante'e Publique, 99, 95–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roe K. M., Minkler M., Saunders F. F. (1995) Combining research, advocacy, and education: the methods of the grandparent caregiver study. Health Education & Behavior, 22, 458–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers E. (2003) Diffusion of Innovations. Free Press: New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Rosa S. (2017) Systems thinking and complexity: considerations for health promotion schools. Health Promotion International 32, 301–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simoneau N., Receveur O. (2000) Attributes of vitamin A- and calcium-rich food items consumed in K’asho Got’ine, Northwest Territories, Canada. Journal of Nutrition Education, 32, 84–93. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma S. (2010) Assessing diet and lifestyle in the Canadian Arctic Inuit and Inuvialuit to inform a nutrition and physical activity intervention programme. Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics, 23, 5–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehy T., Roache C, Sharma S. (2013) Eating habits of a population undergoing a rapid dietary transition: portion sizes of traditional and non-traditional foods and beverages consumed by Inuit adults in Nunavut, Canada. Nutrition Journal, 12, 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shkedi A. (2005). Multiple Case Narrative: A Qualitative Approach to Studying Multiple Populations. John Benjamins Publishing: The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- Smit B. (2005) Teachers, local knowledge, and policy implementation: a qualitative policy-practice inquiry. Education and Urban Society, 37, 292–306. [Google Scholar]

- Van Oostdam J., Donaldson S. G., Feeley M., Arnold D., Ayotte P., Bondy G.. et al. (2005) Human health implications of environmental contaminants in Arctic Canada: a review. Science of the Total Environment, 351-352, 165–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vygotsky L. S. (1978) The interaction between learning and development In Cole M., John‐Steiner V., Scribner S., Souberman E. (eds). Mind in Society. The Development of Higher Psychological Processes. Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA. [Google Scholar]