Abstract

The anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome (APC/C) is a large, multisubunit ubiquitin ligase involved in regulation of cell division. APC/C substrate specificity arises from binding of short degron motifs in its substrates to transient activator subunits, Cdc20 and Cdh1. The destruction box (D-box) is the most common APC/C degron and plays a crucial role in substrate degradation by linking the activator to the Doc1/Apc10 subunit of core APC/C to stabilize the active holoenzyme and promote processive ubiquitylation. Degrons are also employed as pseudosubstrate motifs by APC/C inhibitors, and pseudosubstrates must bind their cognate activators tightly to outcompete substrate binding while blocking their own ubiquitylation. Here we examined how APC/C activity is suppressed by the small pseudosubstrate inhibitor Acm1 from budding yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae). Mutation of a conserved D-box converted Acm1 into an efficient ABBA (cyclin A, BubR1, Bub1, Acm1) motif–dependent APC/CCdh1 substrate in vivo, suggesting that this D-box somehow inhibits APC/C. We then identified a short conserved sequence at the C terminus of the Acm1 D-box that was necessary and sufficient for APC/C inhibition. In several APC/C substrates, the corresponding D-box region proved to be important for their degradation despite poor sequence conservation, redefining the D-box as a 12-amino acid motif. Biochemical analysis suggested that the Acm1 D-box extension inhibits reaction processivity by perturbing the normal interaction with Doc1/Apc10. Our results reveal a simple, elegant mode of pseudosubstrate inhibition that combines high-affinity activator binding with specific disruption of Doc1/Apc10 function in processive ubiquitylation.

Keywords: cell cycle, proteolysis, inhibitor, E3 ubiquitin ligase, inhibition mechanism, Acm1, anaphase-promoting complex, APC/C, destruction box, pseudosubstrate inhibitor

Introduction

Regulated proteolysis via the ubiquitin proteasome pathway is a critical component of many cellular processes, including the cell division cycle. Key to precise control of protein levels is the ability of E3 ubiquitin ligases to selectively bind distinct substrates under appropriate conditions to promote their polyubiquitylation and degradation. In the cell cycle, a large multisubunit E3 enzyme, called the anaphase-promoting complex or cyclosome (APC/C),5 selectively targets cyclins and other mitotic regulators for degradation to promote the events of mitotic exit, including chromosome segregation, spindle disassembly, and cytokinesis, and establishment of the ensuing G1 phase (1). Two forms of the APC/C exist in mitotically dividing cells, differing only in the identity of an activator subunit (Cdc20 or Cdh1) that both recruits substrates and promotes conformational activation of the core APC/C (2). APC/CCdc20 is active during mitosis and required for chromosome segregation and initiation of mitotic exit, whereas APC/CCdh1 is activated later, during mitotic exit, and functions throughout G1. Together, the two APC/C–activator complexes direct the ordered degradation of numerous cell cycle regulators.

The APC/C activator subunits contain a conserved WD40 repeat domain that contains docking sites for several short degron motifs. High-resolution structural studies have revealed how the consensus destruction box (D-box), KEN-box, and ABBA motif degron sequences interact with their activator docking sites (3–8). The D-box appears to be the most widespread degron in APC/C substrates (9) and is unique in the way it binds to APC/C. The N-terminal D-box segment (beginning with the signature sequence RXXL) contacts a conserved site on the surface of the activator WD40 domain, whereas the C-terminal segment binds the Doc1/Apc10 subunit of the core APC/C (8, 10, 11). The composite binding site has been termed the D-box coreceptor. By mediating a physical link between activator and core APC/C, the D-box contributes to APC/C activity by stabilizing the active, substrate-bound holoenzyme complex and possibly other mechanisms that are poorly understood (10, 12–15).

Surprisingly, given its importance, there is a remarkable lack of uniformity in the sequence of substrate D-boxes. Most amino acid positions in the D-box motif are not well-conserved, and several degenerate D-boxes lacking the Arg and/or Leu of the canonical RXXL motif have been reported (16). In addition, RXXL sequences are found ubiquitously in proteins, emphasizing that other elements and/or sequence context are critically important for D-box function. Thus, there is still much to learn about the precise composition of a functional D-box and why D-boxes vary so extensively.

In addition to promoting substrate recognition and degradation, D-boxes and other APC/C degron motifs are used by a class of APC/C regulators found broadly throughout eukaryotes, called pseudosubstrate inhibitors (17, 18). Examples include the mitotic checkpoint complex (MCC), which inhibits APC/CCdc20 in response to spindle checkpoint activation (19), and the vertebrate Emi1 protein, which suppresses APC/CCdh1 activity from early S phase through early mitosis (20). Pseudosubstrates use one or more degron motifs to competitively inhibit substrate binding, but to be effective, they must suppress their own ubiquitylation and degradation by blocking other steps in the APC/C catalytic cycle. Acm1 is a small pseudosubstrate inhibitor that uses ABBA, KEN-box, and D-box motifs to bind with high affinity to Cdh1 and prevent substrate binding (21–24). However, we do not understand how Acm1 inhibits APC/CCdh1 activity to prevent its own degradation. In this report, we describe a simple and novel mechanism of APC/C pseudosubstrate inhibition by Acm1 that combines high-affinity activator binding via multiple degron motifs with a unique D-box C terminus that disrupts the coreceptor function of Doc1/Apc10.

Results

An Acm1 D-box is required to prevent its APC/C-mediated degradation in vivo

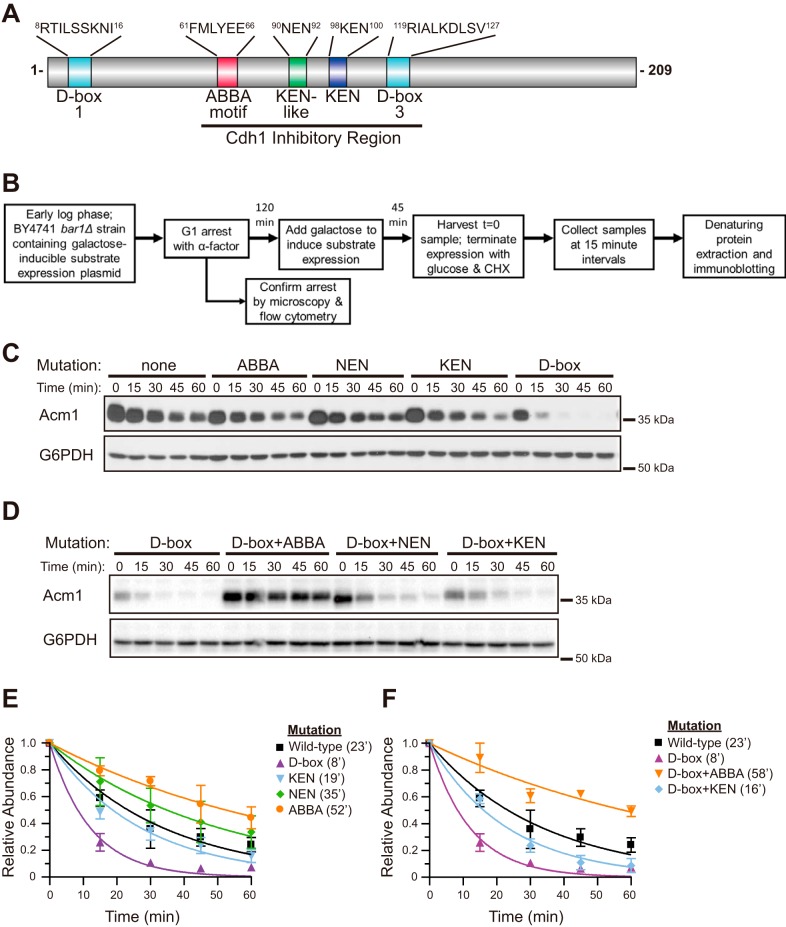

Acm1 contains several conserved sequences that match consensus APC/C degrons (Fig. 1A). The central region, which is responsible for Cdh1 inhibition, contains an ABBA motif, KEN-box, KEN-like NEN sequence, and D-box that all interact with Cdh1 directly and are responsible for the high-affinity Acm1–Cdh1 interaction (3, 21, 22, 25).

Figure 1.

D-box mutation converts Acm1 into an efficient APC/CCdh1 substrate in vivo. A, schematic of Acm1, showing the position and sequence of degron motifs. D-box 1 is recognized by Cdc20 to target Acm1 for degradation and does not contribute to Cdh1 inhibition (21, 22). The remaining motifs constitute the Cdh1 inhibitory region. A second D-box sequence that is not conserved and does not contribute to Cdh1 binding and inhibition is not shown. D-box 3 is the focus of this paper. B, methodological flow chart for the protein stability assay used throughout the paper, described previously in more detail (9). bar1Δ, deletion of the gene for Bar1 protease that cleaves the α-factor mating pheromone. CHX, cycloheximide. C, the stabilities of Acm1 variants containing mutations in the ABBA, NEN, KEN, or D-box 3 motifs were compared with WT Acm1 using an in vivo cycloheximide chase stability assay and immunoblotting. Time 0 represents the point of cycloheximide and glucose addition. D, similar to B, comparing the stability of the single D-box mutant with the indicated double mutants. In C and D, G6PDH (glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase) is a loading control, and all Acm1 variants are truncations lacking the 52 N-terminal residues fused at the C terminus to protein A as described previously (9). Anti-protein A antibody was used to detect Acm1 variants. E and F, quantitative data from experiments represented in C and D, respectively, showing means (± S.D.) relative to time 0 from three independent trials obtained by digital image analysis. Numbers in parentheses are half-life values obtained from fitting the data with a single-phase exponential decay function. The data for WT Acm1 and the single D-box mutant are the same in E and F, allowing separate comparison with the sets of single and double mutants. See Fig. S1 for examples of full Western blot images showing antibody specificity with molecular mass marker positions.

We initially hypothesized that the unusually high affinity of the Acm1–Cdh1 interaction impeded Acm1 polyubiquitylation by the APC/C. If true, then any mutation that lowers the binding affinity for Cdh1 should increase processing of Acm1 as a substrate. Prior in vitro work revealed that mutation of the central KEN-box and D-box in Acm1 led to efficient polyubiquitylation, supporting this idea (21, 22, 25). Using a cycloheximide chase assay, we recently demonstrated that combined KEN-box and D-box mutations also allow efficient APC/CCdh1-mediated degradation of Acm1 in vivo (9). We used this same in vivo stability assay here (Fig. 1B) to assess the effect of individual and combined degron motif mutations on the ability of APC/CCdh1 to use Acm1 as a substrate. Only the D-box single mutation significantly increased Acm1 turnover (Fig. 1, C and E). Combining other degron mutations with the D-box mutation decreased Acm1 turnover (Fig. 1, D and F). The combined D-box and ABBA motif mutant was particularly stable, consistent with our previous observation that the ABBA motif is a functional Cdh1 degron in budding yeast (9). These results are inconsistent with the high-affinity binding hypothesis and instead reveal that an intact D-box in the central inhibitory domain is required, paradoxically, for Acm1 to evade efficient APC/CCdh1-mediated degradation. We next set out to identify the unique properties of the inhibitory Acm1 D-box.

A short C-terminal D-box extension is required for Acm1 identity as an APC/CCdh1 inhibitor

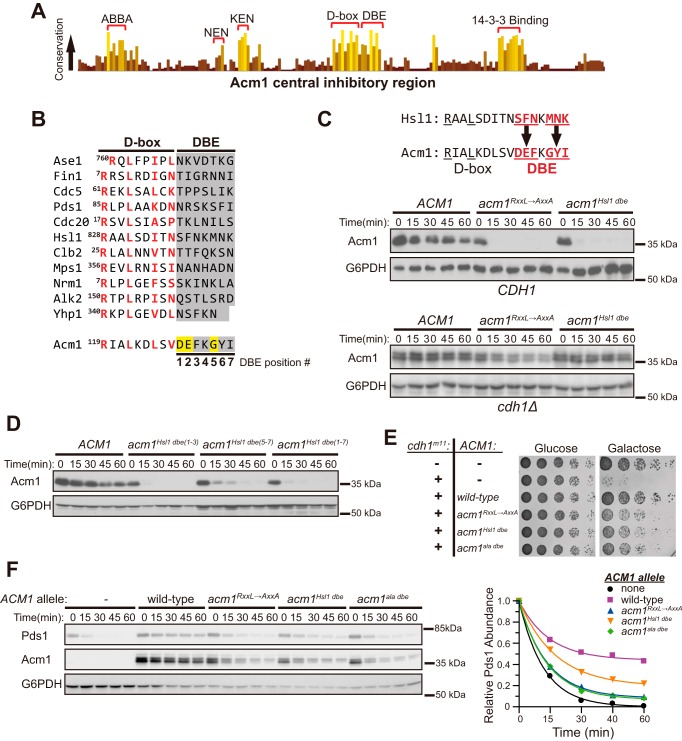

We identified and aligned Acm1 ortholog sequences from related fungal species in the class Saccharomycetes and discovered a short region of strong sequence conservation immediately following the inhibitory D-box, which hereafter we call the D-box extension (DBE) (Fig. 2A and Fig. S2). Cdh1 substrate D-boxes do not exhibit much sequence conservation in this seven-amino-acid region (Fig. 2B). However, some of the conserved DBE amino acids in Acm1 are rarely, if ever, found in Cdh1 substrates, notably the first two acidic residues (16) and glycine at the fifth position. To test whether this region influences Acm1 identity, we replaced it with all or part of the corresponding sequence following the well-studied D-box of the Cdh1 substrate Hsl1 (Fig. 2C). Surprisingly, replacement of the six amino acids that differ between Acm1 and Hsl1 (acm1Hsl1 dbe) rendered Acm1 extremely unstable in a Cdh1-dependent manner, equivalent to an RXXL→AXXA D-box mutation (Fig. 2C). Replacement of just the first three DBE positions was sufficient for the full destabilizing effect, and replacement of the last three also caused significant instability, demonstrating that the entire motif is important for reducing APC/CCdh1-mediated degradation of Acm1 in vivo (Fig. 2D). Individual mutation of each of the first three residues had partial destabilizing effects, with position 3 being the most pronounced (Fig. S3).

Figure 2.

A short sequence adjacent to the Acm1 D-box is required to evade degradation mediated by APC/CCdh1. A, a histogram reflecting conservation at each amino acid position within the central inhibitory region of Acm1. 36 ortholog sequences from Saccharomycetes were aligned using Clustal Omega (Fig. S2), and the results were visualized in Jalview (44). Highly conserved blocks are labeled and consist primarily of the APC/C degron motifs highlighted in Fig. 1A. The conserved C-terminal extension of the D-box 3 is labeled DBE. B, alignment of validated D-box sequences from several budding yeast Cdh1 substrates and the inhibitory D-box of Acm1. The most conserved positions of the core D-box motif are highlighted in red. The DBE region is shaded in gray, and positions are numbered. Yellow highlights conserved Acm1 DBE amino acids not observed at the corresponding positions in substrates. C, starting with the Acm1–protein A fusion construct from Fig. 1, the DBE sequence was replaced with the corresponding sequence from the Cdh1 substrate Hsl1 (highlighted in red). Then the relative stability of this Acm1Hsl1 dbe mutant (acm1Hsl1 dbe) was compared with WT Acm1 (ACM1) and the RXXL→AXXA D-box mutant (acm1RXXL→AXXA) in the cycloheximide chase assay. To ensure degradation was APC/CCdh1-dependent, the assay was repeated in a yeast strain lacking Cdh1 (cdh1Δ). D, similar to C, comparing the stability of Acm1 variants in which the first three (acm1Hsl1 dbe(1–3)), last three (acm1Hsl1 dbe(5–7)), or all (acm1Hsl1 dbe(1–7)) DBE positions were replaced with the corresponding sequence from Hsl1. E, serial dilutions of yeast strains harboring the indicated combinations of cdh1m11 and ACM1 variant galactose-inducible expression plasmids were spotted and grown on agar plates containing glucose or galactose as a carbon source. In acm1ala dbe, the DBE residues were replaced with alanines. F, the ability of the Acm1 variants from E to inhibit degradation of Pds1–protein A was measured using the in vivo stability assay (left panel). Both Pds1 and Acm1 were detected with protein A antibody. The immunoblot signals were quantified and plotted relative to time 0 in the right panel.

We next tested whether the inhibitory function of Acm1 was impaired upon mutation of the DBE. WT Acm1 can restore normal growth to yeast cells expressing a constitutively active Cdh1 variant lacking inhibitory phosphorylation sites (23). Mutations in Acm1 degrons, like the RXXL in the central D-box, impair its ability to suppress this Cdh1-induced toxicity (21). Replacement of the DBE with the corresponding Hsl1 sequence or with a stretch of alanines (acm1ala dbe) impaired complementation, similar to the acm1RXXL→AXXA mutant (Fig. 2E). These DBE mutations also reduced the ability of Acm1 to inhibit APC/CCdh1-mediated degradation of the substrate Pds1 in our G1 stability assay (Fig. 2F), likely because of the lower levels resulting from more rapid turnover. We conclude that the DBE is required for Acm1 function as an inhibitor by suppressing efficient APC/CCdh1-mediated Acm1 degradation.

The Acm1 DBE is sufficient to suppress APC/CCdh1 and APC/CCdc20 substrate degradation

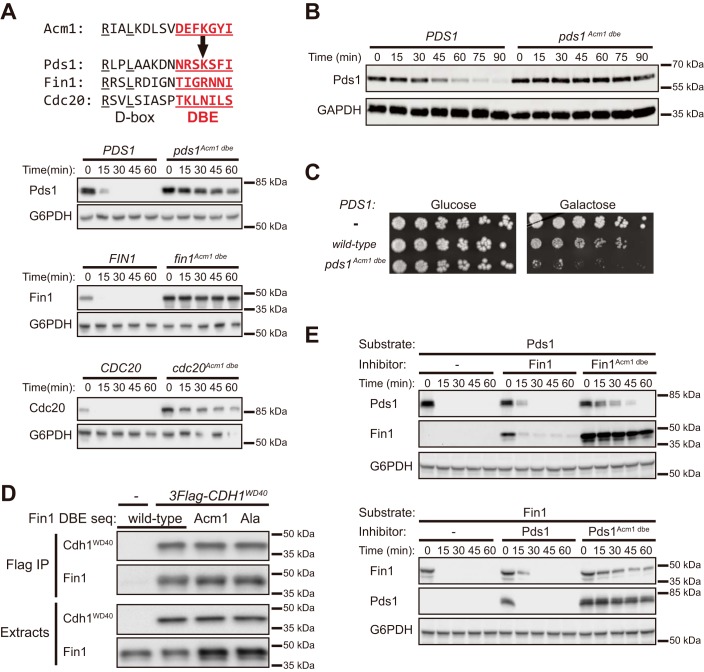

To test whether the Acm1 DBE is sufficient for evasion of APC/CCdh1-mediated degradation, we performed the reciprocal sequence swap experiment, in which the DBE sequence from Acm1 replaced the corresponding sequence in several Cdh1 substrates with well-established D-boxes (26–28). Degradation of Pds1, Fin1, and Cdc20 was almost completely abolished following replacement of their C-terminal D-box sequences with the DBE from Acm1 (Fig. 3A).

Figure 3.

The Acm1 DBE is sufficient to block degradation of APC/CCdh1 and APC/CCdc20 substrates and to confer pseudosubstrate inhibitor capacity. A, the DBE sequence (red) from Acm1 replaced the DBE of the indicated epitope-tagged Cdh1 substrates in galactose-inducible expression plasmids. The stability of these DBE variants was compared with their WT counterparts. Pds1 and Cdc20 contained C-terminal protein A tags, and Fin1 contained a C-terminal 3×HA tag. B, yeast strains carrying PDS1 or pds1Acm1 dbe (tagged with 3×FLAG) under control of the GALS promoter were grown in galactose medium containing nocodazole for 3 h and then released from the arrest by washing and transfer to medium containing glucose at time 0. Levels of Pds1 or Pds1Acm1 dbe at the indicated times following release were determined by immunoblotting. GAPDH (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) is a loading control. C, liquid yeast cultures harboring GALS promoter–driven WT PDS1 or pds1Acm1 dbe were serially diluted and plated on medium containing the indicated sugar. D, coimmunoprecipitation of WT Fin1-3×HA and variants containing the DBE sequence from Acm1 or Ala substitutions at each DBE position with the 3×FLAG-tagged Cdh1 WD40 domain. The negative control (−) represents an identical immunoprecipitation procedure using cells that do not express 3FLAG-Cdh1WD40. E, the ability of Cdh1 substrate variants containing the Acm1 DBE sequence (Fin1Acm1 dbe and Pds1Acm1 dbe) to inhibit degradation of another Cdh1 substrate was measured using the in vivo stability assay. Both substrate and inhibitor are expressed from galactose-inducible expression plasmids. Fin1 is expressed with a C-terminal 3×HA tag and Pds1 with a C-terminal protein A tag.

Pds1 degradation by APC/CCdc20 is essential for the metaphase-to-anaphase transition (27). To test whether the DBE similarly affects substrate degradation by APC/CCdc20 in vivo, yeast cells were arrested in mitosis with nocodazole, and degradation of Pds1 (expressed from the inducible GAL promoter) was monitored over time after release from nocodazole in the presence of repressing glucose. Although WT Pds1 was degraded as APC/CCdc20 was activated upon release from the nocodazole arrest, Pds1Acm1 dbe remained stable throughout the time course (Fig. 3B). We were unable to generate a yeast strain expressing the pds1Acm1 dbe allele from the natural PDS1 promoter, suggesting that it is lethal. Consistent with this possibility, constitutive expression of Pds1Acm1 dbe, but not WT Pds1, from the GAL promoter was highly toxic in a plate growth assay (Fig. 3C). Collectively, these results demonstrate that the presence of the Acm1 DBE severely impairs Pds1 degradation mediated by APC/CCdc20.

The DBE substitutions did not impair substrate interactions with Cdh1 based on a co-IP interaction assay (Fig. 3D), demonstrating that DBE function is distinct from that of the RXXL motif, which binds the activator WD40 domain. Consistent with this, substrates containing the Acm1 DBE inhibited APC/C activity toward other substrates (Fig. 3E). Inhibition was not as strong as that observed with Acm1, however (9), presumably because docking interactions were of insufficiently high affinity to fully outcompete binding of other substrates. We conclude that the DBE sequence from Acm1 is sufficient to strongly suppress APC/CCdh1- and APC/CCdc20-mediated ubiquitylation and degradation of a bound substrate.

The DBE region is important for normal substrate processing

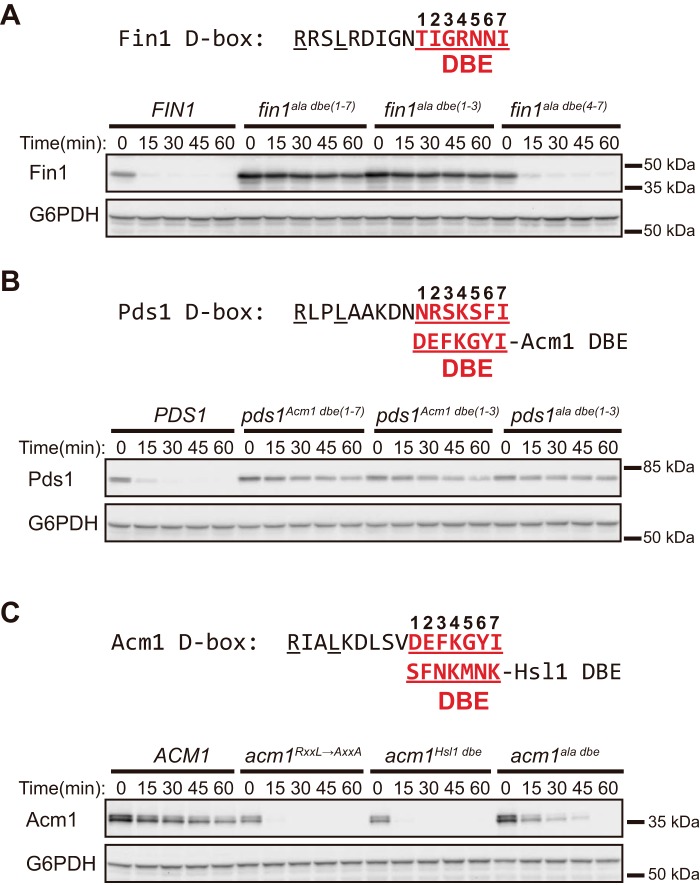

The DBE is clearly important in the pseudosubstrate inhibitor Acm1 to prevent its degradation. To test whether the corresponding region in substrates is generally important for processing by APC/CCdh1, we generated alanine mutants in the substrates Fin1 and Pds1 and measured the effect on in vivo stability. Given the lack of primary sequence similarity among substrates in this region, we expected little effect on degradation rates. To our surprise, alanine substitution at all DBE positions of Fin1 (fin1ala dbe(1–7)) severely reduced its in vivo degradation (Fig. 4A). In contrast to the inhibitory function of the Acm1 DBE, only the first three DBE positions appeared to be important for Fin1 degradation. Mutation of the first three positions of the Pds1 DBE to Ala impaired its degradation as well, similar to replacement with the Acm1 DBE sequence (Fig. 4B). These results strongly suggest that the first half of the DBE region plays a general role in D-box function and substrate processing.

Figure 4.

The DBE region is important for APC/C substrate degradation. A, the stability of substrate Fin1 and DBE variants with Ala substitutions in either the first three, last four, or all seven positions was compared in the in vivo stability assay using anti-HA antibody for Fin1-3×HA detection. B, the stability of substrate Pds1 and the indicated DBE variants was compared using anti-protein A antibody detection. C, the stability of Acm1 and the indicated D-box and DBE variants was compared using anti-protein A antibody detection.

Mutation of the Acm1 DBE to alanines (acm1ala dbe) enhanced the Acm1 degradation rate (Fig. 4C), consistent with the idea that the Acm1 DBE sequence is important for preventing degradation and allowing it to act as an inhibitor. However, Acm1ala dbe was more stable than Acm1Hsl1 DBE (Fig. 4C), supporting the idea that the DBE sequence in substrates helps promote degradation. We attribute the relative instability of Acm1ala dbe compared with Fin1ala dbe and Pds1ala dbe to the presence of the ABBA motif in Acm1, which acts as an efficient degron even in the absence of a functional D-box (see Fig. 1D). These results suggest that the DBE can exist in multiple functional states in the context of a consensus D-box: activating (e.g. Hsl1 or other substrates), inhibitory (e.g. Acm1), and nonfunctional (e.g. alanine mutants and presumably many other proteins that have minimal D-box motifs that are not functional APC/C degrons).

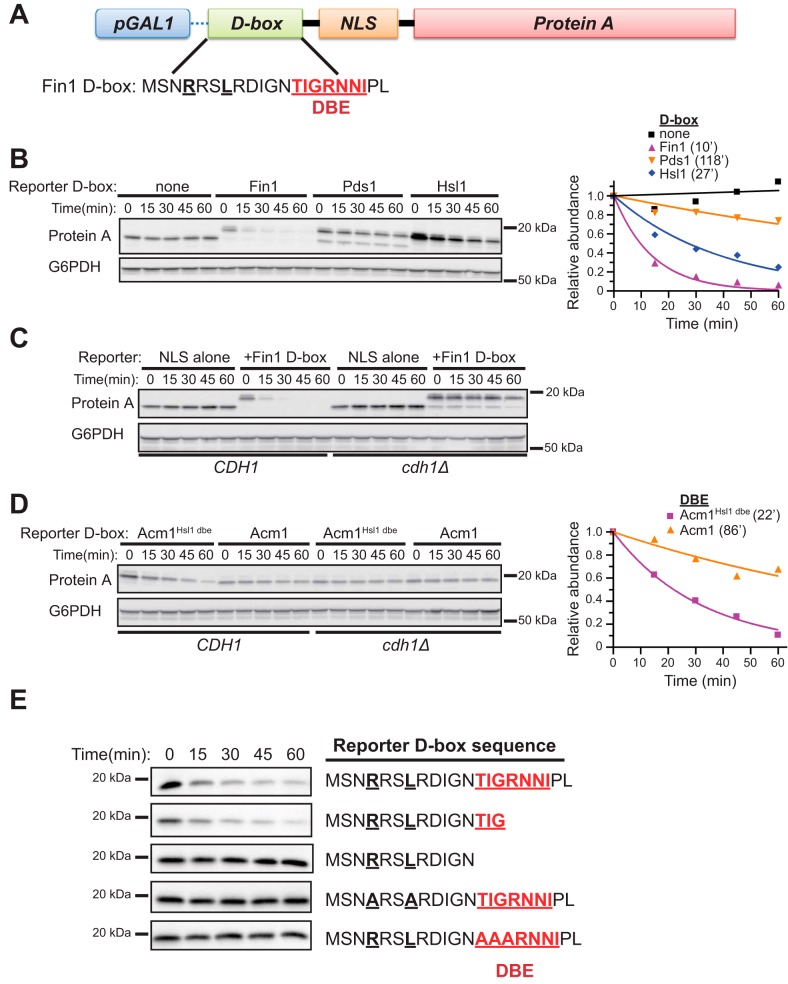

The D-box and the DBE constitute a functional, transportable APC/CCdh1 degron

Fusing the consensus D-box motif to heterologous, stable proteins is usually not sufficient to promote APC/C-mediated proteolysis, indicating that additional sequences or the appropriate sequence context are also required for recognition and processing (29, 30). In light of our studies, we wondered whether the canonical nine-residue D-box motif combined with all or part of the DBE region would be sufficient to promote degradation of a stable, heterologous protein by APC/CCdh1 in vivo. We began by fusing a sequence encoding a 20-amino-acid region encompassing the D-box and DBE of Hsl1, Fin1, Pds1, and Acm1 to an SV40 NLS–protein A construct (Fig. 5A). The NLS in this substrate reporter protein was used to ensure colocalization with APC/CCdh1, which is primarily active in the nucleus (28), and protein A has been used for similar degron fusion studies in the past (29, 30). The NLS-protein A fusion protein without an attached degron motif was stable, as expected, in the G1 cycloheximide chase assay (Fig. 5B). In contrast, addition of the Fin1 or Hsl1 D-box region resulted in rapid Protein A degradation. Addition of the Pds1 D-box had only a minor effect on protein A stability. Thus, different D-box sequences vary in their capacity to promote protein A degradation. The Fin1 D-box region was particularly effective at promoting degradation, and this effect was completely dependent on Cdh1 (Fig. 5C), demonstrating that this sequence contained a fully functional APC/CCdh1 degron. Consistent with its inhibitory function, the Acm1 D-box region was ineffective at promoting reporter degradation (Fig. 5D). However, replacing the Acm1 DBE sequence with that from Hsl1 (Acm1Hsl1 dbe) enhanced degradation, and this effect was also Cdh1-dependent. Thus, even in the context of this artificial substrate, the DBE region is important for processing.

Figure 5.

Identification of a minimal, transportable destruction box. A, reporter construct for transportable D-box characterization. A GAL1 promoter drives expression of the protein A ZZ domain containing an N-terminal SV40 NLS sequence and candidate degron. The sequence of the initial D-box region used from Fin1 is shown. B, the stability of reporter proteins containing the Fin1 D-box region from A and the equivalent D-box regions from Pds1 and Hsl1 were compared with a control NLS–protein A lacking a degron sequence. Chemiluminescent immunoblot signals were quantified by digital image analysis and plotted relative to time 0 in the graph on the right. Numbers in parentheses are half-lives from fitting data with an exponential decay function. C, the Fin1 D-box reporter and control lacking a D-box were compared in CDH1 and cdh1Δ yeast strains to ensure that instability depended on APC/CCdh1 activity. D, analysis of the reporter fused to the inhibitory D-box from Acm1 containing either its natural DBE sequence or the DBE from Hsl1. The results from the WT CDH1 strains were quantified and plotted relative to time 0 in the graph on the right. Numbers in parentheses are half-lives from the exponential decay fit. E, the stabilities of the indicated truncations of the Fin1 D-box region in the reporter construct were compared.

To further define the contribution of the DBE to the function of the transportable D-box, we evaluated a collection of truncations and point mutations in the Fin1 D-box region of the protein A reporter (Fig. 5E). A 12-residue sequence beginning with RXXL and extending through the first three DBE positions was sufficient to promote protein A degradation, whereas the reporter containing the canonical nine-residue D-box lacking the DBE was stable. Moreover, alanine substitutions at the first three DBE positions stabilized protein A, similar to the RXXL→AXXA D-box mutation. Thus, we suggest that a minimal, transportable D-box is a 12-amino-acid motif beginning with RXXL and extending through the first three positions of the DBE region.

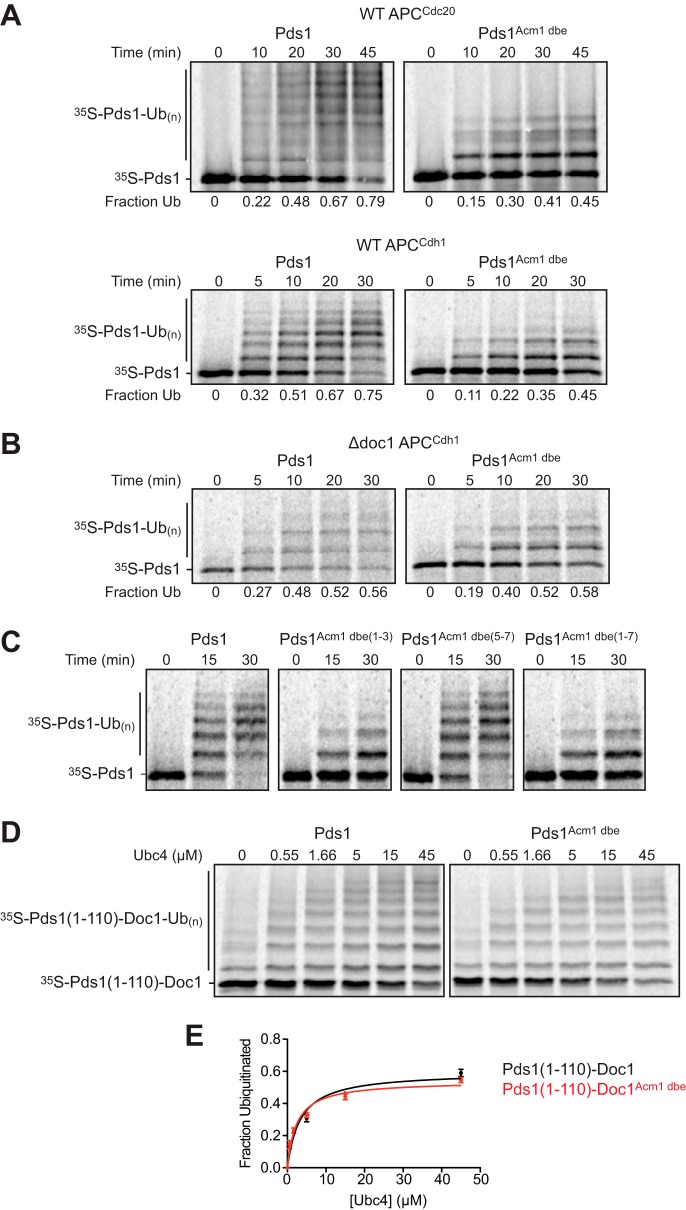

The Acm1 DBE reduces the processivity of APC/C-catalyzed polyubiquitylation in vitro

To understand the mechanism by which the Acm1 DBE blocks substrate degradation, we turned to enzyme activity assays with purified APC/C and a radiolabeled substrate, Pds1, either with its natural D-box or a variant containing the DBE sequence from Acm1. Activity with both APC/CCdc20 and APC/CCdh1 was severely reduced when the Acm1 DBE motif was present (Fig. 6A). Reduced activity was evident as a decline in the rate of substrate turnover (loss of the unmodified substrate) and a decline in the processivity of polyubiquitylation (decreased numbers of ubiquitins attached to substrate).

Figure 6.

The Acm1 DBE reduces Pds1 ubiquitylation by the APC/C in vitro. A, ubiquitylation of Pds1/securin by APC/CCdc20 and APC/CCdh1 in vitro. APC/C was immunopurified from yeast lysates and incubated with Cdc20 (top) or Cdh1 (bottom) produced by translation in vitro. APC/C–activator complexes were combined with E2-ubiquitin conjugates and then incubated for the indicated times with radiolabeled Pds1, either WT (left) or a mutant in which C-terminal D-box residues (amino acids 94–100) were replaced with the DBE of Acm1. Reaction products were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by PhosphorImager. The ubiquitylated substrate fraction is shown beneath each lane. B, APC/C was immunopurified from lysate of a doc1Δ strain, combined with Cdh1, and tested for activity toward WT or mutant Pds1 as in A. C, APC/CCdh1 was prepared as in A and tested for activity with WT Pds1 or mutant Pds1 in which various C-terminal D-box residues were replaced with equivalent DBE residues from Acm1, as indicated. D, using translation in vitro, radiolabeled fusion proteins were produced in which the N-terminal 110 residues of Pds1 (WT or carrying the Acm1 DBE) were fused to the N terminus of Doc1. Fusion proteins were incubated for 30 min with Δdoc1 APC/CCdh1 in the presence of varying concentrations of the E2 Ubc4 (15), and reaction products were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by PhosphorImager. E, quantification of the results from D from two independent experiments.

The effect of the Acm1 DBE was similar to that observed previously for APC/C lacking the core subunit Doc1/Apc10 (31). We therefore repeated the experiment using APC/CCdh1 lacking Doc1/Apc10 and found that the reaction rate and processivity with Pds1WT and Pds1Acm1 dbe were similar (Fig. 6B). Thus, the Acm1 DBE has no inhibitory effect in the absence of Doc1/Apc10, arguing that its effects with WT APC/C depend on Doc1/Apc10. Further studies revealed that the first three amino acids of the Acm1 DBE were sufficient to reduce activity toward Pds1, whereas the last three amino acids had no noticeable effect (Fig. 6C).

To further explore the inhibitory effects of the Acm1 DBE, we took advantage of a previously described fusion between Pds1 and Doc1 that bypasses the need for substrate binding to the activator and Doc1/Apc10 (15). In reactions with Δdoc1 APC/CCdh1, the rates and processivity of polyubiquitylation of the Pds1WT-Doc1 and Pds1Acm1 dbe-Doc1 fusion proteins were very similar (Fig. 6D), suggesting that the defects caused by the Acm1 DBE are overcome when the enzyme is saturated with substrate that is fused to a core subunit. Moreover, polyubiquitylation of Pds1WT-Doc1 and Pds1Acm1 dbe–Doc1 were equally sensitive to E2 concentration (Fig. 6E), indicating that the Acm1 DBE does not affect the interaction of APC/C with E2. Taken together, these results are consistent with the DBE primarily affecting D-box interaction with Doc1/Apc10.

Discussion

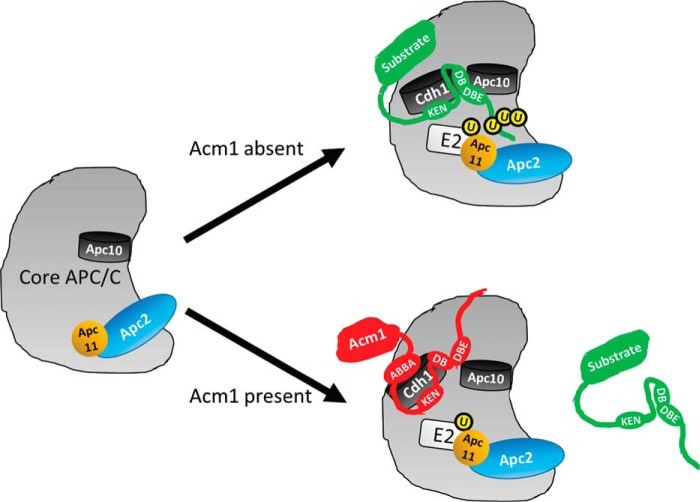

APC/C degrons, such as the KEN-box and D-box, act as docking motifs for substrate recognition. However, the D-box also contributes to APC/C catalysis by enhancing the interaction between the activator and core APC/C (12–14). It does this by simultaneously binding both the activator and the Doc1/Apc10 core subunit (10, 11), and cryo-EM data support the idea that this stabilizes the conformation of the activator WD40 domain when bound to APC/C (8, 10). The stable activator–APC/C interaction generates a catalytically competent enzyme conformation capable of recruiting and correctly positioning E2-ubiquitin (15, 32) and processively ubiquitylating substrates (31). In this report, we describe how this function of the D-box has been modified in Acm1 to create a potent pseudosubstrate inhibitor.

APC/C inhibitors that use degron-like pseudosubstrate motifs are pervasive in eukaryotic species and have been valuable models for studying mechanisms of substrate recognition and processing. For pseudosubstrates to be effective inhibitors, they must bind APC/C with high affinity to outcompete natural substrates and must employ a mechanism to evade their own ubiquitylation and degradation. The highly conserved MCC, which includes Cdc20, Mad2, and the pseudosubstrate protein Mad3/BubR1, inhibits APC/CCdc20 to delay anaphase onset until sister chromatids are correctly bioriented on the mitotic spindle (19). When bound, it occludes degron docking sites on Cdc20 as well as the binding site for the E2 UbcH10 (5, 33). Interestingly, MCC binding also disrupts the D-box coreceptor site between Cdc20 and Doc1/Apc10 by displacing APC/C-bound Cdc20. The vertebrate Emi1 protein is an APC/CCdh1 inhibitor that uses a D-box motif for Cdh1 binding and a zinc binding domain and LRRL tail sequence to block E2 binding and thereby inhibit APC/C enzyme activity (4, 34). Although Acm1 is known to competitively block substrate binding to Cdh1 through its ABBA, KEN-box, and D-box motifs (21, 22, 25, 35), its mechanism for evading degradation has remained unclear.

The D-box in the central inhibitory region of Acm1 is functionally unique in that RXXL→AXXA mutation has the opposite effect that it has in substrates; rather than stabilizing Acm1, it allows efficient APC/C-directed Acm1 degradation. This led us to the discovery of the Acm1 DBE motif, adjacent to the canonical D-box, which is primarily responsible for Acm1's inhibitory function. The most obvious biochemical effect of the inhibitory DBE is decreased processivity of substrate polyubiquitylation. The observation that the DBE had no effect on catalysis by an APC/C lacking the Doc1/Apc10 subunit links the DBE inhibitory effect to Doc1/Apc10 function. This is consistent with the fact that the C-terminal portion of the D-box directly binds Doc1/Apc10 (32). Thus, the simplest explanation is that the Acm1 DBE disrupts the interaction between the substrate and Doc1/Apc10. As a result, the stabilizing interaction between Cdh1, the D-box, and Doc1/Apc10 does not occur. This would presumably lead to more rapid substrate dissociation, rendering ubiquitylation inefficient and nonprocessive, similar to loss of Doc1/Apc10 and mutation of the D-box binding site on Doc1/Apc10 (14, 31, 36).

Although attractive, this simple mechanism alone is difficult to rationalize with the observation that the RXXL→AXXA mutation in the inhibitory D-box makes Acm1 an efficient APC/CCdh1 substrate. This result implies that the Acm1 DBE must be positioned through RXXL engagement with the D-box receptor site on Cdh1 to exert its inhibitory effect. This would not be the case if the sole function of the Acm1 DBE is to prevent interaction with Doc1/Apc10. Furthermore, the Acm1 DBE sequence is highly conserved. One would expect many amino acid combinations to be sufficient to disrupt the weak interaction between the D-box and Doc1/Apc10. The requirement for specific amino acids in the inhibitory DBE suggests an additional layer of mechanistic complexity. A previous report suggested that lack of suitably positioned lysines for ubiquitin conjugation was partly responsible for inefficient processing of Acm1 as a substrate (25). One possibility is that the Acm1 DBE, rather than simply preventing Doc1/Apc10 binding, reorients the interaction with Doc1/Apc10 in such a way that nearby lysine residues are directed away from the active site and are unable to attack the E2-ubiquitin conjugate (Fig. 7). Mutations either in the RXXL or DBE regions would then be sufficient to reduce binding and release nearby lysines from this constraint, allowing them to contact the E2 and promote processive polyubiquitylation. Relevant to this idea, a recent study revealed that two D-boxes in human cyclin A2 bind the D-box receptor of Cdc20 in distinct orientations that direct the downstream polypeptide chain in different directions and influence ubiquitylation efficiency (37). Other possibilities exist as well, and a complete understanding of the mechanism by which the Acm1 DBE inhibits APC/C processivity will require further investigation.

Figure 7.

Model for APC/C inhibition by Acm1. In the absence of activator Cdh1 (left), the core APC/C exists in an inactive conformation (2). Cdh1 recruits substrates through binding of degron motifs like the KEN-box and D-box to form a ternary complex with core APC/C (top right). Cdh1–substrate binding to core APC/C is stabilized by docking of the D-box (DB) C terminus (including the DBE region defined here) to Apc10 and triggers conformational activation of APC/C through a shift in the Apc2-Apc11 catalytic module. This allows recruitment of E2-ubiquitin and stably positions the substrate emerging from the D-box binding site for processive ubiquitin (U) chain addition. When present, Acm1 outcompetes substrates for Cdh1 binding because of the presence of the additional ABBA motif (bottom right). Rather than facilitating normal interaction of the D-box with Apc10, the inhibitory Acm1 DBE sequence interferes with Apc10's ability to promote processive ubiquitylation. This could happen in several ways. As shown here, the Acm1 DBE could interact differently with Apc10, resulting in diversion of the peptide chain away from E2-ubiquitin in the active site. Alternatively, it could actively repel Apc10, preventing Cdh1–substrate from adopting the required stable association with core APC/C for efficient, processive ubiquitylation to occur. Consequently, Acm1 is not rapidly turned over like a substrate and continually occupies Cdh1 to repress APC/C activity.

Our Acm1 DBE characterization also redefines the boundaries of a functional D-box motif. The D-box was the first APC/C degron identified and characterized, initially in sea urchin cyclin B (29, 30). It was reported then as a nine-residue motif with the consensus sequence RXXLXXXXN. However, the cyclin B consensus D-box was only functional as a transportable degron when an additional stretch of poorly conserved sequence at its C terminus was included (30). Here we found that the substrate region corresponding to the first three positions of the Acm1 DBE was critically important for in vivo degradation and that a 12-residue D-box beginning with the conserved RXXL and containing these three positions was sufficient to act as a transportable degron and should be considered the minimal functional D-box. Although the unique inhibitory Acm1 DBE is well-conserved in budding yeasts, this region of substrate D-boxes shows little sequence similarity across APC/C substrates, suggesting that it may act by promoting some general structural context satisfied by a broad range of amino acid combinations. Unfortunately, this region of substrates is not well-resolved in current high-resolution APC/C structures, and we can only speculate that it constitutes part of the Doc1/Apc10 interaction motif.

In summary, our results have revealed a novel and simple mechanism for pseudosubstrate inhibition of the APC/C. Acm1 combines high-affinity Cdh1 binding through its multiple degron motifs with an atypical D-box C terminus that disrupts Doc1/Apc10 function in processive substrate ubiquitylation. As a result, Acm1 is a potent competitive inhibitor that stably binds the substrate docking site on Cdh1 without being modified and degraded efficiently. Interestingly, the small pseudosubstrate inhibitor mes1 in Schizosaccharomyces pombe shares some features with Acm1. It inhibits the meiosis-specific activator Fzr1/Mfr1, and, similar to Acm1, mutation of the mes1 D-box motif accelerates its ubiquitylation and degradation (38). Although its role in APC/C inhibition has not been tested, the DBE region of the mes1 D-box does show some resemblance to the Acm1 DBE (ELVK in mes1, DEFK in Acm1 for positions 1–4). Thus, modified D-boxes that allow tight activator binding but impair processive ubiquitylation may represent a recurring mechanism by which pseudosubstrate inhibitors control APC/C activity.

Experimental procedures

Reagents

Details of all plasmid constructs are listed in Table S1. All site-directed mutations were generated using the QuikChange multisite-directed mutagenesis kit (Agilent Technologies, 210515) according to the provided instructions and confirmed by DNA sequencing. Yeast strains YKA233 (MATa his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 bar1::hisG), YKA247 (MATa ade2-1 can1–100 his3–11,15 leu2–3,112 trp1-1 ura3-1 bar1::URA3 acm1::KanMX4), and YKA412 (MATa his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 bar1::hisG cdh1::KanMX4) have been described previously (9, 23) and were cultured using standard methods and media as described previously (9). Cycloheximide (C1988), 3×FLAG peptide (F4799), rabbit polyclonal anti-protein A (P3775), mouse monoclonal anti-FLAG-M2 (F1804), and rabbit polyclonal anti-G6PDH (A9521) were from Sigma-Aldrich. Mouse monoclonal anti-HA (11666606001) was from Roche Applied Science. Luminata Crescendo Western HRP substrate (WBLUR0100) was from Millipore. Anti-FLAG resin (L00432) was purchased from, and α-factor peptide was synthesized by, Genscript. Horseradish peroxidase–conjugated anti-rabbit (111-035-003) and anti-mouse (115-035-003) secondary antibodies were from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories.

In vivo protein stability assay

We used an acm1 truncation allele lacking the first 52 codons and fused at its 3′ end to the coding sequence for protein A to monitor the APC/CCdh1-mediated turnover rate of Acm1. This truncated fusion protein is partially resistant to the natural APC/C-independent G1 proteolytic mechanism of Acm1 (39), making its G1-specific turnover largely dependent on Cdh1 (9). Yeast strains (YKA233 or when cdh1Δ control was required, YKA412) containing galactose-inducible expression plasmids were cultured, arrested in G1 with α-factor, induced with galactose, treated with cycloheximide and glucose to terminate expression, harvested at regular intervals, and processed for immunoblotting exactly as described previously (9). Chemiluminescent immunoblot signals were captured on autoradiograph film and a ChemiDoc Touch digital imager (Bio-Rad). All quantitation was performed from digital images using ImageLab software (Bio-Rad). For quantitation of protein stabilities, signals were adjusted based on the G6PDH loading control and normalized to time 0. Data were fit with a single-phase exponential decay function in GraphPad Prism to obtain half-life values.

Multisequence alignment

Acm1 orthologs from fungal species were identified using PSI-BLAST (40). An alignment of 36 putative orthologs was generated using Clustal Omega (41) with default settings.

In vivo inhibition assay

The in vivo Cdh1 inhibition assay on galactose-containing agar plates was performed as described previously (23).

Coimmunopurification

Co-IP of Fin1-3HA and DBE variants with the 3FLAG-Cdh1 WD40 domain was performed in strain YKA247. Saturated cultures in selective medium were used to inoculate 300 ml of standard yeast extract, peptone, and raffinose medium. These cultures were grown to A600 near 0.3 and arrested in G1 with α-factor. Expression of Fin1-3HA and 3FLAG-Cdh1WD40 were induced for 45 min by addition of 2% galactose. Cells were pelleted, washed with water, and resuspended in 25 mm HEPES (pH 7.5), 100 mm sodium acetate, 10% glycerol, 0.1% Triton X-100, and 0.5 mm DTT. Cell lysis and co-IP were then performed exactly as described previously (9).

APC/C assays

Yeast cells carrying CDC16-TAP and lacking CDH1 were lysed in 25 mm HEPES (pH 7.5), 150 mm potassium acetate, 2.5 mm MgCl2, 10% glycerol, 0.5% Triton X-100, 1 mm DTT, 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and protease inhibitor mixture. The APC/C was immunopurified using IgG-coupled magnetic beads. Cdc20 and Cdh1 were translated in vitro using the TnT T7 Quick Coupled Reticulocyte Lysate System (Promega, L1170) and incubated with APC/C at 22 °C for 30 min. To produce substrates, WT or D-box mutants of full-length Pds1 were C-terminally ZZ-tagged and translated in vitro using [35S]methionine. Substrates were purified with IgG-coupled magnetic beads and eluted from beads by cleavage with tobacco etch virus protease (Thermo Fisher, 12575015). E1 and E2 (Ubc4) were expressed in Escherichia coli and purified as described previously (42, 43). E2 charging was performed in a reaction containing 0.2 mg/ml Uba1, 2 mg/ml Ubc4, 2 mg/ml methylated ubiquitin (Boston Biochem, U-501) and 1 mm ATP at 37 °C for 30 min. The ubiquitylation reaction was initiated by mixing E2-ubiquitin conjugates, APC/CActivator, and the indicated substrate at 25 °C for the indicated times. Reactions were terminated with 2× SDS sample loading dye, separated by 10% SDS-PAGE, and analyzed with a Typhoon 9400 Imager and ImageQuant (GE Healthcare).

E2 dose–response experiments were performed as described previously (15), with the following modifications. The first 110 amino acids of Pds1 were fused to the N terminus of Doc1, translated in vitro using [35S]methionine, and incubated with immunopurified APC/C lacking Doc1/Apc10 at 25 °C for 30 min. N-terminally ZZ-tagged Cdh1 was translated in vitro with unlabeled methionine, purified with magnetic IgG beads, and cleaved with tobacco etch virus protease. Reactions were performed at 25 °C by mixing APC/CPds1(1–110)-Doc1, purified Cdh1, and varying concentrations of E2-ubiquitin conjugates. Michaelis–Menten graphs were analyzed using GraphPad Prism.

Author contributions

L. Q. and M. C. H. conceptualization; L. Q., A. M., D. O. M., and M. C. H. formal analysis; L. Q., A. M., D. S. P. S. F. G., and H. M. T. investigation; L. Q., D. O. M., and M. C. H. writing-review and editing; D. O. M. and M. C. H. supervision; D. O. M. and M. C. H. funding acquisition; D. O. M. and M. C. H. methodology; M. C. H. writing-original draft; M. C. H. project administration.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge support from the Purdue Center for Cancer Research Shared Resources Program via NIH NCI Grant P30 CA023168. We thank the Purdue University Office of the Executive Vice President for Research and Partnerships as well as the College of Agriculture for funding support.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

This article contains Figs. S1–S3 and Table S1.

- APC/C

- anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome

- D-box

- destruction box

- MCC

- mitotic checkpoint complex

- DBE

- D-box extension

- IP

- immunopurification

- NLS

- nuclear localization signal

- ABBA

- cyclin A, BUBR1, BUB1, Acm1

- G6PDH

- glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase.

References

- 1. Pines J. (2011) Cubism and the cell cycle: the many faces of the APC/C. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 12, 427–438 10.1038/nrm3132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Alfieri C., Zhang S., and Barford D. (2017) Visualizing the complex functions and mechanisms of the anaphase promoting complex/cyclosome (APC/C). Open Biol. 7, 170204 10.1098/rsob.170204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. He J., Chao W. C., Zhang Z., Yang J., Cronin N., and Barford D. (2013) Insights into degron recognition by APC/C coactivators from the structure of an Acm1-Cdh1 complex. Mol. Cell 50, 649–660 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.04.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chang L., Zhang Z., Yang J., McLaughlin S. H., and Barford D. (2015) Atomic structure of the APC/C and its mechanism of protein ubiquitination. Nature 522, 450–454 10.1038/nature14471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Alfieri C., Chang L., Zhang Z., Yang J., Maslen S., Skehel M., and Barford D. (2016) Molecular basis of APC/C regulation by the spindle assembly checkpoint. Nature 536, 431–436 10.1038/nature19083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Diaz-Martinez L. A., Tian W., Li B., Warrington R., Jia L., Brautigam C. A., Luo X., and Yu H. (2015) The Cdc20-binding Phe box of the spindle checkpoint protein BubR1 maintains the mitotic checkpoint complex during mitosis. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 2431–2443 10.1074/jbc.M114.616490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chao W. C., Kulkarni K., Zhang Z., Kong E. H., and Barford D. (2012) Structure of the mitotic checkpoint complex. Nature 484, 208–213 10.1038/nature10896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Brown N. G., VanderLinden R., Watson E. R., Weissmann F., Ordureau A., Wu K. P., Zhang W., Yu S., Mercredi P. Y., Harrison J. S., Davidson I. F., Qiao R., Lu Y., Dube P., Brunner M. R., et al. (2016) Dual RING E3 architectures regulate multiubiquitination and ubiquitin chain elongation by APC/C. Cell 165, 1440–1453 10.1016/j.cell.2016.05.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Qin L., Guimarães D. S., Melesse M., and Hall M. C. (2016) Substrate Recognition by the Cdh1 destruction box receptor is a general requirement for APC/CCdh1-mediated proteolysis. J. Biol. Chem. 291, 15564–15574 10.1074/jbc.M116.731190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. da Fonseca P. C., Kong E. H., Zhang Z., Schreiber A., Williams M. A., Morris E. P., and Barford D. (2011) Structures of APC/C(Cdh1) with substrates identify Cdh1 and Apc10 as the D-box co-receptor. Nature 470, 274–278 10.1038/nature09625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Buschhorn B. A., Petzold G., Galova M., Dube P., Kraft C., Herzog F., Stark H., and Peters J. M. (2011) Substrate binding on the APC/C occurs between the coactivator Cdh1 and the processivity factor Doc1. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 18, 6–13 10.1038/nsmb.1979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Burton J. L., Tsakraklides V., and Solomon M. J. (2005) Assembly of an APC-Cdh1-substrate complex is stimulated by engagement of a destruction box. Mol. Cell 18, 533–542 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.04.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Passmore L. A., and Barford D. (2005) Coactivator functions in a stoichiometric complex with anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome to mediate substrate recognition. EMBO Rep. 6, 873–878 10.1038/sj.embor.7400482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Matyskiela M. E., and Morgan D. O. (2009) Analysis of activator-binding sites on the APC/C supports a cooperative substrate-binding mechanism. Mol. Cell 34, 68–80 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.02.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Van Voorhis V. A., and Morgan D. O. (2014) Activation of the APC/C ubiquitin ligase by enhanced E2 efficiency. Curr. Biol. 24, 1556–1562 10.1016/j.cub.2014.05.052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Davey N. E., and Morgan D. O. (2016) Building a regulatory network with short linear sequence motifs: lessons from the degrons of the anaphase-promoting complex. Mol. Cell 64, 12–23 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.09.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Barford D. (2011) Structure, function and mechanism of the anaphase promoting complex (APC/C). Q. Rev. Biophys. 44, 153–190 10.1017/S0033583510000259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pesin J. A., and Orr-Weaver T. L. (2008) Regulation of APC/C activators in mitosis and meiosis. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 24, 475–499 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.041408.115949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lara-Gonzalez P., Westhorpe F. G., and Taylor S. S. (2012) The spindle assembly checkpoint. Curr. Biol. 22, R966–R980 10.1016/j.cub.2012.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Di Fiore B., and Pines J. (2007) Emi1 is needed to couple DNA replication with mitosis but does not regulate activation of the mitotic APC/C. J. Cell Biol. 177, 425–437 10.1083/jcb.200611166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Choi E., Dial J. M., Jeong D.-E., and Hall M. C. (2008) Unique D box and KEN box sequences limit ubiquitination of Acm1 and promote pseudosubstrate inhibition of the anaphase-promoting complex. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 23701–23710 10.1074/jbc.M803695200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Enquist-Newman M., Sullivan M., and Morgan D. O. (2008) Modulation of the mitotic regulatory network by APC-dependent destruction of the Cdh1 inhibitor Acm1. Mol. Cell 30, 437–446 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.04.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Martinez J. S., Jeong D. E., Choi E., Billings B. M., and Hall M. C. (2006) Acm1 is a negative regulator of the Cdh1-dependent anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome in budding yeast. Mol. Cell Biol. 26, 9162–9176 10.1128/MCB.00603-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ostapenko D., Burton J. L., Wang R., and Solomon M. J. (2008) Pseudosubstrate inhibition of the anaphase-promoting complex by Acm1: regulation by proteolysis and Cdc28 phosphorylation. Mol. Cell Biol. 28, 4653–4664 10.1128/MCB.00055-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Burton J. L., Xiong Y., and Solomon M. J. (2011) Mechanisms of pseudosubstrate inhibition of the anaphase promoting complex by Acm1. EMBO J. 30, 1818–1829 10.1038/emboj.2011.90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Woodbury E. L., and Morgan D. O. (2007) Cdk and APC activities limit the spindle-stabilizing function of Fin1 to anaphase. Nat. Cell Biol. 9, 106–112 10.1038/ncb1523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cohen-Fix O., Peters J. M., Kirschner M. W., and Koshland D. (1996) Anaphase initiation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae is controlled by the APC-dependent degradation of the anaphase inhibitor Pds1p. Genes Dev. 10, 3081–3093 10.1101/gad.10.24.3081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Arnold L., Höckner S., and Seufert W. (2015) Insights into the cellular mechanism of the yeast ubiquitin ligase APC/C-Cdh1 from the analysis of in vivo degrons. Mol. Biol. Cell 26, 843–858 10.1091/mbc.E14-09-1342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Glotzer M., Murray A. W., and Kirschner M. W. (1991) Cyclin is degraded by the ubiquitin pathway. Nature 349, 132–138 10.1038/349132a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. King R. W., Glotzer M., and Kirschner M. W. (1996) Mutagenic analysis of the destruction signal of mitotic cyclins and structural characterization of ubiquitinated intermediates. Mol. Biol. Cell 7, 1343–1357 10.1091/mbc.7.9.1343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Carroll C. W., and Morgan D. O. (2002) The Doc1 subunit is a processivity factor for the anaphase-promoting complex. Nat. Cell Biol. 4, 880–887 10.1038/ncb871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Chang L. F., Zhang Z., Yang J., McLaughlin S. H., and Barford D. (2014) Molecular architecture and mechanism of the anaphase-promoting complex. Nature 513, 388–393 10.1038/nature13543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Yamaguchi M., VanderLinden R., Weissmann F., Qiao R., Dube P., Brown N. G., Haselbach D., Zhang W., Sidhu S. S., Peters J. M., Stark H., and Schulman B. A. (2016) Cryo-EM of mitotic checkpoint complex-bound APC/C reveals reciprocal and conformational regulation of ubiquitin ligation. Mol. Cell 63, 593–607 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.07.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Frye J. J., Brown N. G., Petzold G., Watson E. R., Grace C. R., Nourse A., Jarvis M. A., Kriwacki R. W., Peters J. M., Stark H., and Schulman B. A. (2013) Electron microscopy structure of human APC/C(CDH1)-EMI1 reveals multimodal mechanism of E3 ligase shutdown. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 20, 827–835 10.1038/nsmb.2593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Martinez J. S., Hall H., Bartolowits M. D., and Hall M. C. (2012) Acm1 contributes to nuclear positioning by inhibiting Cdh1-substrate interactions. Cell Cycle 11, 384–394 10.4161/cc.11.2.18944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Carroll C. W., Enquist-Newman M., and Morgan D. O. (2005) The APC subunit Doc1 promotes recognition of the substrate destruction box. Curr. Biol. 15, 11–18 10.1016/j.cub.2004.12.066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Zhang S., Tischer T., and Barford D. (2019) Cyclin A2 degradation during the spindle assembly checkpoint requires multiple binding modes to the APC/C. Nat. Commun. 10, 3863 10.1038/s41467-019-11833-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kimata Y., Kitamura K., Fenner N., and Yamano H. (2011) Mes1 controls the meiosis I to meiosis II transition by distinctly regulating APC/C co-activators Fzr1/Mfr1 and Slp1 in fission yeast. Mol. Biol. Cell 22, 1486–1494 10.1091/mbc.E10-09-0774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Melesse M., Choi E., Hall H., Walsh M. J., Geer M. A., and Hall M. C. (2014) Timely activation of budding yeast APCCdh1 involves degradation of its inhibitor, Acm1, by an unconventional proteolytic mechanism. PLoS ONE 9, e103517 10.1371/journal.pone.0103517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Altschul S. F., Madden T. L., Schäffer A. A., Zhang J., Zhang Z., Miller W., and Lipman D. J. (1997) Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25, 3389–3402 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sievers F., Wilm A., Dineen D., Gibson T. J., Karplus K., Li W., Lopez R., McWilliam H., Remmert M., Söding J., Thompson J. D., and Higgins D. G. (2011) Fast, scalable generation of high-quality protein multiple sequence alignments using Clustal Omega. Mol. Syst. Biol. 7, 539 10.1038/msb.2011.75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Carroll C. W., and Morgan D. O. (2005) Enzymology of the anaphase-promoting complex. Methods Enzymol. 398, 219–230 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)98018-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Rodrigo-Brenni M. C., and Morgan D. O. (2007) Sequential E2s drive polyubiquitin chain assembly on APC targets. Cell 130, 127–139 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Waterhouse A. M., Procter J. B., Martin D. M., Clamp M., and Barton G. J. (2009) Jalview version 2: a multiple sequence alignment editor and analysis workbench. Bioinformatics 25, 1189–1191 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.