Abstract

A successful pregnancy is critically dependent upon proper placental development and function. During human placentation, villous cytotrophoblast (CTB) progenitors differentiate to form syncytiotrophoblasts (SynTBs), which provide the exchange surface between the mother and fetus and secrete hormones to ensure proper progression of pregnancy. However, epigenetic mechanisms that regulate SynTB differentiation from CTB progenitors are incompletely understood. Here, we show that lysine-specific demethylase 1 (LSD1; also known as KDM1A), a histone demethylase, is essential to this process. LSD1 is expressed both in CTB progenitors and differentiated SynTBs in first-trimester placental villi; accordingly, expression in SynTBs is maintained throughout gestation. Impairment of LSD1 function in trophoblast progenitors inhibits induction of endogenous retrovirally encoded genes SYNCYTIN1/endogenous retrovirus group W member 1, envelope (ERVW1) and SYNCYTIN2/endogenous retrovirus group FRD member 1, envelope (ERVFRD1), encoding fusogenic proteins critical to human trophoblast syncytialization. Loss of LSD1 also impairs induction of chorionic gonadotropin α (CGA) and chorionic gonadotropin β (CGB) genes, which encode α and β subunits of human chorionic gonadotrophin (hCG), a hormone essential to modulate maternal physiology during pregnancy. Mechanistic analyses at the endogenous ERVW1, CGA, and CGB loci revealed a regulatory axis in which LSD1 induces demethylation of repressive histone H3 lysine 9 dimethylation (H3K9Me2) and interacts with transcription factor GATA2 to promote RNA polymerase II (RNA-POL-II) recruitment and activate gene transcription. Our study reveals a novel LSD1–GATA2 axis, which regulates human trophoblast syncytialization.

Keywords: placenta, trophoblast, transcription regulation, histone demethylase, human, cytotrophoblast, LSD1, syncytiotrophoblast

Introduction

Human pregnancy is associated with a hemochorial placentation (1, 2) in which placental trophoblasts are directly exposed to the maternal blood to establish the exchange surface for nutrients and gases at the maternal–fetal interface. This exchange surface is established via formation of multinucleated SynTBs5 (1, 2). During human placentation, two distinct SynTBs develop from two different progenitors. At the onset of human placentation, a zone of invasive primitive syncytium forms from trophectoderm cells at the blastocyst implantation site (2–4). The primitive syncytium invades the endometrium and takes up nutrients from the maternal environment to ensure further embryonic development. The primitive syncytium also produces hCG that rescues the corpus luteum to maintain progesterone production required for pregnancy (5). Afterward, columns of CTB progenitors penetrate the primitive syncytium to form primary villi. The primary villi eventually branch and mature to form villous placenta, containing two types of matured villi: (i) anchoring villi, which anchor to maternal tissue, and (ii) floating villi, which float in the maternal blood of the intervillous space (2–4). The proliferating CTBs within anchoring and floating villi adapt distinct differentiation fates during placentation (6). In anchoring villi, CTBs establish a column of proliferating CTB progenitors known as column CTBs (6), which differentiate to invasive extravillous trophoblasts. In contrast, CTB progenitors of floating villi (villous CTBs) differentiate and fuse to form the outer multinucleated SynTB layer, which is bathed in maternal blood. The villous CTB–derived SynTBs establish the nutrient, gas, and waste exchange surface, produce hormones; and promote immune tolerance to fetus throughout gestation (7–12).

CTB to SynTB differentiation is associated with cell cycle termination and alteration of gene expression programs, including activation of retroviral genes ERVW1 and ERVFRD1. ERVW1 and ERVFRD1 function as fusogen to induce CTB fusion (13–15). In addition, CTB to SynTB differentiation is also associated with the induction of CGA and CGB, which encode α and β subunits of hCG, an essential hormone for maintenance of human pregnancy (8–10). Interestingly, a single CGA gene on human chromosome 6 encodes the hCGα, whereas the hCGβ can be produced by a cluster of six paralogous genes (CGB (also known as CGB3), CGB1, CGB2, CGB5, CGB7, and CGB8) located on chromosome 19 (16–20).

Our understanding of molecular mechanisms of human SynTB differentiation mostly came from in vitro cell culture studies involving primary CTBs, which are isolated from term placenta (term CTBs) (21–23), and BeWo cells, a cell line derived from human choriocarcinoma (24, 25). The term CTBs spontaneously differentiate to SynTBs, whereas activation of the cyclic AMP (cAMP)–protein kinase A (PKA) signaling pathway in BeWo cells stimulates SynTB differentiation (26–28). The SynTB differentiation in these cells can be tested by measuring induction of ERVW1, ERVFRD1, CGA, and CGB expressions; loss of E-Cadherin expression; and induction of cell fusion. Studies on term CTBs and BeWo cells have increased our understanding of signaling pathways (22, 29, 30) and transcriptional mechanisms, which are involved in CTB to SynTB differentiation (31, 32). These studies also identified several evolutionarily conserved transcription factors, including glial cell missing 1 and GATA2 as regulators of ERVW1, ERVFRD1, CGA, and CGB transcription during SynTB differentiation (33–35). However, epigenetic mechanisms that coordinate with conserved transcription factors in response to signaling pathways to induce SynTB differentiation are poorly understood.

A study (36) with mutant mouse models and mouse trophoblast stem cells (TSCs) has implicated LSD1, the first identified histone demethylase (37), as an important regulator of trophoblast stem and progenitor cell differentiation. LSD1 is unique in its mechanism and can demethylate mono- and dimethyl groups on both histone H3 lysine 4 (H3K4) and histone H3 lysine 9 (H3K9) residues to promote either repression or activation of gene transcription (38, 39). LSD1 interacts with the corepressor to the transcription factor REST (CoREST) and the nucleosome remodeling and deacetylase (NuRD) chromatin-remodeling complexes (40–44), which are involved in transcriptional repression. As a part of these repressive complexes, LSD1 specifically mediates demethylation of mono- and dimethylated H3K4, leading to transcriptional repression of a gene. On the contrary, LSD1 changes its substrate specificity from the H3K4 to H3K9 residue when it interacts with certain transcription factors such as androgen (AR) and estrogen (ER) nuclear hormone receptors (45–48) and cMYB (49). In those contexts, LSD1 functions as an activator of gene transcription as demethylation of H3K9 residues is often associated with gene activation. Thus, depending on the cellular context and interaction with other factors, LSD1 can promote either activation or repression of a gene.

Mouse embryos with global deletion of Lsd1 gene die around embryonic day 7.5 (36). Major morphological defects and embryonic lethality are observed in trophoblast-specific Lsd1-knockout embryos. Furthermore, LSD1 has been implicated in promoting stemness (36, 50) and in preventing senescence (51) in mouse TSCs. These studies reveal LSD1 as an important regulator of trophoblast development during placentation in mouse and in utero survival of a developing mouse embryo.

Both mouse and human undergo hemochorial placentation; however, the trophoblast cell types and the placentation process in these two species differ significantly (52). For example, mouse trophoblast syncytialization is not dependent on ERVW1 or ERVFRD1 as different endogenous retrovirally encoded proteins are involved in that process (53). Furthermore, mouse placentation is not associated with induction of CGA and CGB expressions (52). Thus, despite this importance in the context of mouse placentation, the role of LSD1 in human trophoblast development is yet to be defined. In addition, it is also unknown how histone modification dynamics is regulated by LSD1 during human trophoblast development and whether LSD1 functions as a coactivator or a corepressor during that process.

Given the conserved nature of LSD1 and the phenotype of the Lsd1-mutant mice, in this study, we investigated LSD1 expression at different stages of human placentation. We found that LSD1 is highly expressed in SynTBs throughout gestation. Therefore, we tested the importance of LSD1 via loss-of-function analyses and confirmed an essential role of LSD1 in human SynTB differentiation.

Results

LSD1 is highly expressed in SynTBs of a human placenta

Studies with gene-knockout mouse models and mouse TSCs indicated that LSD1 is essential to prevent premature differentiation of mouse TSCs and is also required for directing their differentiation fate (36). A search of published studies related to LSD1 function in human trophoblasts revealed only three studies with human trophoblast cell lines (HTR-8/SVneo, JEG3, and JAR cells), implicating LSD1 as a part of the gene regulatory machinery downstream of long noncoding RNAs (54–56). However, LSD1 expression patterns in primary trophoblast cells during human placentation and the functional importance of LSD1 in the context of human trophoblast differentiation have never been studied. Hence, we started our study by looking at LSD1 expression during human placentation. We tested LSD1 protein expression in both first-trimester and term human placentae. In a first-trimester human placental villus, two trophoblast cell layers exist: a basal layer of mononuclear CTB progenitors and an outer multinucleated SynTB layer. We found that in a first-trimester human placenta, LSD1 is abundantly expressed in both CTB progenitors and differentiated SynTBs (Fig. 1A). In contrast, LSD1 expression is very low in nontrophoblast stromal cells. We also detected a high level of LSD1 expression within the SynTBs in term human placentae (Fig. 1B). Thus, our expression analyses revealed that LSD1 expression is maintained in human SynTBs throughout the gestational time period.

Figure 1.

LSD1 is abundantly expressed in human SynTBs. A, immunohistochemistry showing LSD1 is highly expressed within trophoblast cells (both CTBs (red arrows) and SynTBs (green arrows)) of a first-trimester (9-week) human placenta. IgG was used as a negative control for the immunostaining experiment. B, immunohistochemistry showing LSD1 is highly expressed in SynTBs (green arrows) of a term human placenta. C, micrographs showing altered morphology of BeWo cells when they were treated with 8-Br-cAMP for 72 h to induce SynTB differentiation. D, analysis of mRNA expression showing significant induction of SynTB-specific genes in 8-Br-cAMP–treated BeWo cells (expression level of a gene in untreated BeWo cells was considered as 1; mean ± S.E.; n = 3; *, p ≤ 0.001; Error bars represent S.E.). E, immunofluorescence images showing a high level of LSD1 expression at the nuclei of BeWo cells. F, Western blots showing LSD1 protein expression is maintained in 8-Br-cAMP–treated, differentiated BeWo cells.

LSD1 is important for CTB to SynTB differentiation

We tested the importance of LSD1 in human trophoblast syncytialization by using BeWo cells (Clone B30) as a model system. BeWo cells have been widely used to study trophoblast syncytialization as they recapitulate the cellular behavior and gene expression patterns of syncytiotrophobast development in response to PKA activators like forskolin and 8-bromo-cAMP (8-Br-cAMP) (24–28). In the standard culture condition, BeWo cells are unable to spontaneously differentiate and maintain a cellular state, equivalent to undifferentiated CTB progenitors of a third-trimester human placenta (27). However, following exposure to 8-bromo-cAMP (BeWo-differentiating condition), BeWo cells undergo morphological changes (Fig. 1C) and are a good model for testing the human SynTB differentiation process. This syncytialization process in BeWo cells could be monitored by transcriptional induction of ERVW1/ERVFRD1, CGA, and CGB (Fig. 1D).

We found that LSD1 is highly expressed in both undifferentiated and differentiated BeWo cells (Fig. 1, E and F) and localizes in the nuclei (Fig. 1E), which is consistent with its function in chromatin modification. Notably, the LSD1 protein expression level is not altered upon BeWo cell differentiation (Fig. 1F).

To test the importance of LSD1 in SynTB differentiation, we depleted LSD1 in BeWo cells via RNAi using lentiviral shRNAs. The shRNA-mediated knockdown of LSD1 resulted in a nearly 90% loss in LSD1 mRNA expression (Fig. 2A) and appeared just as efficient when LSD1 protein expression was visualized by Western blotting (Fig. 2B). Also, the knockdown efficiency was similarly maintained in LSD1-depleted BeWo cells (LSD1KD BeWo cells) when they were cultured in the differentiating culture condition with 8-Br-cAMP (Fig. 2B). However, mRNA expressions of several other histone demethylases such as KDM1B, KDM2A, KDM2B, and KDM3A were not affected in LSD1KD BeWo cells (Fig. S1A), indicating that shRNA-mediated knockdown was specific to LSD1.

Figure 2.

Loss of LSD1 impairs SynTB differentiation. A and B, quantitative RT-PCR (mean ± S.E.; n = 3; *, p ≤ 0.001) (A) and Western blot (B) analyses showing depletion of LSD1 mRNA and protein expressions in BeWo cells upon shRNA-mediated RNAi (LSD1KD BeWo). BeWo cells, which were transduced with a nonfunctional shRNA, were considered as a control. C, analysis of mRNA expression showing impaired induction of SynTB-specific genes in 8-Br-cAMP–treated LSD1KD BeWo cells (mean ± S.E.; n = 3; *, p ≤ 0.001). D, immunofluorescence images showing E-Cadherin (E-CAD) expression and nuclei of control and LSD1-depleted BeWo cells in undifferentiated and differentiating (with 8-Br-cAMP) culture conditions. Efficient syncytialization of 8-Br-cAMP–treated control BeWo cells is evident from loss of E-Cadherin and cell–cell fusion (red boundaries). Impaired syncytialization in 8-Br-cAMP–treated LSD1KD BeWo cells is evident from maintenance of E-Cadherin expression and lack of cell–cell fusion. Only a few regions (red boundary, right panel) show partial loss of E-Cadherin expression. E, Western blot analyses showing depletion of LSD1 protein expression in human term CTBs upon shRNA-mediated RNAi (LSD1KD CTBs). F, micrographs showing impaired syncytialization (monitored by cell–cell fusion; white boundaries in left control panel) in LSD1KD CTBs. The syncytialization was not evident with LSD1KD CTBs (right panel). G, quantitative RT-PCR (mean ± S.E.; n = 3; *, p ≤ 0.001) analyses showing impaired induction of ERVW1, CGA, and CGB transcription in LSD1KD CTBs. Note that the SynTB differentiation of term CTBs was not associated with an induction in ERVFRD1 transcription. Error bars in panels A, C, and G represent S.E.

Also, the depletion of LSD1 did not alter the proliferation rate of undifferentiated BeWo cells (data not shown), indicating that LSD1 is not essential for survival of BeWo cells. However, loss of LSD1 strongly impaired 8-Br-cAMP–induced mRNA expressions of SYNCYTINs, CGA, and CGB genes (Fig. 2C). Interestingly, expressions of ITGA6 and HLA-G, which are known to be expressed in human trophoblast cells (57), including the BeWo cells (58, 59) were not altered in LSD1KD BeWo cells (Fig. S1, B and C), indicating that LSD1 loss did not induce a pleotropic effect on gene expression in BeWo cells. We also analyzed E-Cadherin expression in LSD1KD BeWo cells and found that loss of LSD1 maintained E-Cadherin expression and inhibited cell–cell fusion in differentiating BeWo cells (Fig. 2D). Collectively, the impaired induction of SynTB differentiation–associated genes, the maintenance of E-Cadherin expression, and the impaired cell–cell fusion in LSD1-depleted BeWo cells indicated that LSD1 might be an important regulator for SynTB differentiation in primary CTBs. Therefore, we performed a loss-of-LSD1-function study using a human primary CTB differentiation model.

In vitro culturing of primary CTBs from term human placenta results in their spontaneous differentiation to SynTBs (23). Therefore, we depleted LSD1 in term CTBs (LSD1KD CTBs) via RNAi (Fig. 2E) and cultured them to test efficiency of SynTB differentiation. We noticed efficient cell syncytialization (Fig. 2F) and induction of ERVW1, CGA, and CGB genes (Fig. 2G) when term CTBs were differentiated to SynTBs. However, similar to our findings in BeWo cells, cell syncytialization and induction of ERVW1, CGA, and CGB genes were impaired in LSD1KD CTBs (Fig. 2, F and G). Thus, from our two-pronged analyses in BeWo cells and in primary term CTBs, we inferred that LSD1 mediates an essential function to ensure SynTB differentiation from CTB progenitors.

LSD1 eliminates repressive H3K9Me2 modification at the SynTB-associated genes

In association with repressive complexes such as Co-REST and NuRD, LSD1 demethylates mono- and dimethylated H3K4 residues, thereby promoting formation of a compact, repressive chromatin structure (Fig. 3A). In contrast, upon interacting with certain transcription factors like AR and ER (41–44), LSD1 demethylates mono- and dimethylated H3K9 residues, leading to formation of an open, transcriptionally active chromatin (Fig. 3A). Therefore, we investigated the histone demethylase properties of LSD1 in the context of SynTB differentiation. To that end, we focused on dimethylated H3K4 (H3K4Me2), a histone modification specifically enriched at the promoter regions of transcriptionally active genes as well as genes that are poised for future expression during cellular differentiation (60–62), and H3K9Me2 modification, a histone mark associated with the promoter regions of repressed genes that are predominantly localized within the euchromatin region rather than within the constitutive pericentromic heterochromatin region (63, 64).

Figure 3.

LSD1 demethylates H3K9Me2 mark at key gene promoters during SynTB differentiation. A, cartoon showing two modes of LSD1 function. LSD1 demethylates H3K4 methylation when it interacts with the CoREST or NuRD repressive complexes at transcriptionally active gene loci. In contrast, LSD1 demethylates H3K9 methylation and promotes gene transcription when it interacts with certain transcription factors like AR, ER, and cMYB. B, Western blot analyses showing similar levels of global H3K4Me2 and H3K9Me2 modifications in control and LSD1KD BeWo cells. C and D, plots showing quantitative ChIP assessment of H3K4Me2 (C) and H3K9Me2 (D) deposition at the promoter regions of SynTB-associated genes in control and LSD1KD BeWo cells. Signal from 0.2% of total input chromatin before immunoprecipitation (for details, see Ref. 94) was considered as 1 to generate the relative enrichment plot. *, p < 0.01; three independent experiments. The red dotted line indicates the average nonspecific enrichment using IgG as the negative control antibody for ChIP analyses. E, plot showing quantitative assessment of H3K9Me2 deposition at the promoter regions of SynTB-associated genes in control and LSD1KD CTBs (*, p < 0.01; three independent experiments). HDAC, histone deacetylase. Error bars in panels C, D, and E represent S.E.

We noticed that global levels of dimethylated H3K4Me2 and H3K9Me2 are not altered in LSD1KD BeWo cells (Fig. 3B). Also, quantitative ChIP analyses showed that enrichment of the H3K4Me2 mark at the promoter regions of ERVW1/ERVFRD1, CGA, and CGB3 genes was not significantly altered in BeWo cells upon induction of syncytialization with 8-Br-cAMP or in response to the loss of LSD1 expression (Fig. 3C). Rather, we noticed that SynTB differentiation of BeWo cells is associated with strong loss of H3K9Me2 modification at the ERVW1/2, CGA, and CGB3 promoter regions (Fig. 3D). However, 8-Br-cAMP treatment in LSD1KD BeWo cells was unable to reduce the H3K9Me2 mark from the promoter regions of SynTB-associated genes (Fig. 3D).

We also tested incorporation of the H3K9Me2 mark at the promoter regions of ERVW1, CGA, and CGB3 genes in primary term CTBs. We found that differentiation of CTBs is also associated with significant loss of the H3K9Me2 mark at those promoters regions, and this process is impaired in LSD1KD CTBs. (Fig. 3E). Collectively, these findings indicated that during SynTB differentiation, LSD1 functions as a transcriptional coactivator by removing the repressive H3K9Me2 mark at key gene loci.

LSD1 complexes with GATA2 and promotes RNA polymerase II (Pol-II) recruitment at the SynTB-associated genes

The coactivator function of LSD1, in which it promotes activation of gene transcription by H3K9 demethylation, depends upon its interaction with specific transcription factors like AR, ER, and cMYB. However, we noticed that these factors are either expressed at very low levels or not expressed in BeWo cells and primary CTBs. Consequently, we reasoned that other transcription factors might interact with LSD1 to promote its coactivator function during SynTB differentiation. To that end, we focused on the GATA family transcription factor GATA2, which is known to interact with LSD1 in a different cellular context (65) and is implicated in trophoblast gene regulation, including induction of ERVW1 and CGA transcription in human trophoblast cells (34, 35). In an earlier study (66), we showed that GATA2 is selectively expressed in the trophoblast cells (both in CTBs and SynTBs) of a first-trimester human placenta. GATA2 is also abundantly expressed in the SynTBs of a term human placenta (Fig. 4A) and in undifferentiated and differentiated BeWo cells (Fig. 4B). Interestingly, GATA2 expression was maintained in LSD1KD BeWo cells both in undifferentiated and differentiating culture conditions (Fig. 4B), indicating that GATA2 expression is regulated in BeWo cells via an LSD1-independent mechanism.

Figure 4.

LSD1 facilitates recruitment of GATA2 at the CGA, CGB, and ERVW1 gene loci during SynTB differentiation. A, immunohistochemistry showing GATA2 is highly expressed in SynTBs (green arrows) of a term human placenta. B, Western blot analyses showing GATA2 protein expressions in control and LSD1KD BeWo cells. C, sequence alignments of human and rhesus monkey CGA and CGB3 loci showing the presence of conserved WGATAR motifs around the transcription start site. The red vertical bars on top indicate positions of the conserved WGATAR motifs. D, positions and sequences of conserved WGATAR motifs at human CGA and CGB3 loci. E, sequence around −250 bp region of the human ERVW1 locus showing GATA motifs, which were implicated earlier in transcriptional regulation of ERVW1. F, plot showing quantitative ChIP assessment of GATA2 occupancy at the CGA, CGB3, and ERVW1 loci in control and LSD1KD BeWo cells (signal from 0.2% of total input chromatin before immunoprecipitation was considered as 1 to generate the relative enrichment plot; *, p < 0.001; three independent experiments). The red dotted line indicates the average nonspecific enrichment using IgG as the negative control antibody for ChIP analyses. Note that GATA2 occupancy was not significantly enriched at the −335 bp region of the CGA locus, which contains a WGATA(T) motif, instead of a WGATAR(A/G) motif. G, plot showing quantitative ChIP assessment of GATA2 occupancy at the CGA, CGB3, and ERVW1 loci in control and LSD1KD CTBs (*, p < 0.01; three independent experiments). Error bars in panels F and G represent S.E.

As GATA2 expression is maintained in differentiating BeWo cells with and without LSD1 depletion, we asked whether GATA2 chromatin recruitment is impaired at certain gene loci in LSD1KD BeWo cells. Earlier studies with reporter genes implicated GATA2 in transcriptional regulation of ERVW1 (34) and CGA (35) genes. However, GATA2 chromatin recruitment at the endogenous ERVW1 and CGA loci has never been tested. Therefore, we tested GATA2 chromatin occupancy at these two gene loci and at the CGB3 locus in control and LSD1KD BeWo cells.

GATA factors selectively occupy canonical W(A/T)GATAR(A/G) motifs at a chromatin locus to directly regulate gene expression program (66–68). The human CGA locus contains multiple conserved WGATAR motifs within the region spanning +1 to −1 kb of the transcription start site (Fig. 4, C and D), whereas the human CGB3 locus contains a single conserved WGATAR motif at −350 bp upstream of the transcription start site (Fig. 4, C and D). In addition, the −250 bp region of the human ERVW1 locus harbors a canonical W/(A)-GATA-R/(A) motif and a W(A)-GATAC motif (Fig. 4E), which were earlier implicated for transcriptional activation of ERVW1 (34). Therefore, we tested GATA2 chromatin occupancy at theses GATA motifs in undifferentiated and differentiated BeWo cells. We found that GATA2 occupies multiple GATA motifs at the CGA locus, the −350 bp region of the CGB3 locus and the −250 bp region of the ERVW1 locus only in differentiated BeWo cells (Fig. 4F). We also found that loss of LSD1 impairs GATA2 chromatin occupancy at the CGA, CGB, and ERVW1 loci during BeWo cell differentiation (Fig. 4F). We made a similar observation in differentiated primary CTBs in which a significant loss in GATA2 occupancy at the CGA, CGB3, and ERVW1 loci was observed upon loss of LSD1 (Fig. 4G).

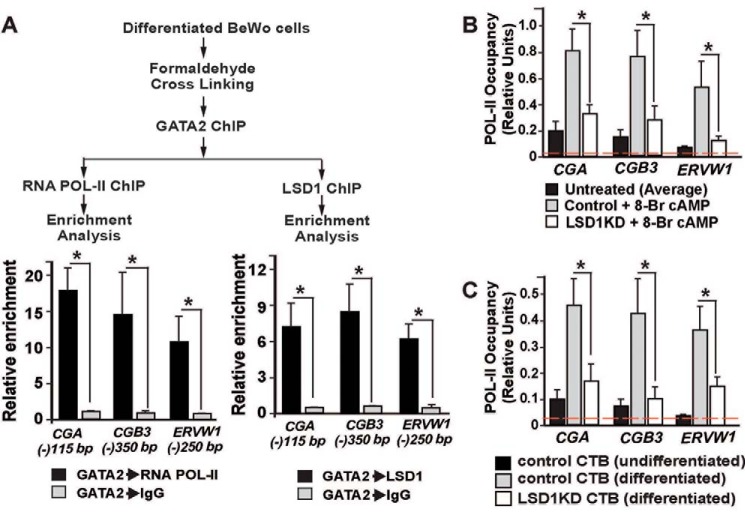

Our findings that LSD1 removes the repressive histone H3K9Me2 mark and promotes GATA2 recruitment at the SynTB-associated genes indicated that an LSD1–GATA2 transcriptional activation complex could be a part of the transcriptional machinery during SynTB differentiation. As GATA2 facilitates recruitment of RNA-POL-II at its target genes (69, 70), we also hypothesized that the LSD1–GATA2 complex promotes RNA-POL-II binding to induce transcription at GATA2 target genes during SynTB differentiation. Therefore, we next asked whether LSD1, GATA2, and RNA-POL-II physically interact at the endogenous CGA, CGB3, and ERVW1 loci and whether loss of LSD1 impairs that interaction, leading to loss of RNA-POL-II recruitment to those genes during SynTB differentiation. To that end, we performed sequential ChIP assays with differentiated BeWo cells and confirmed both LSD1–GATA2 and GATA2–RNA-POL-II interactions at the CGA, CGB3, and ERVW1 gene loci (Fig. 5A). We also confirmed loss of RNA-POL-II recruitment at the CGA, CGB3, and ERVW1 gene promoters in 8-Br-cAMP–treated LSD1KD BeWo cells (Fig. 5B) and LSD1-depleted primary CTBs (Fig. 5C). Collectively, these results provided evidence for formation of an LSD1–GATA2 complex, which recruits RNA-POL-II at key gene loci to activate their transcription during CTB to SynTB differentiation.

Figure 5.

LSD1, GATA2, and RNA-POL-II physically interact at the SynTB-associated gene loci during SynTB differentiation, and loss of LSD1 impairs RNA-POL-II recruitment. A, sequential ChIP showing co-occupancy of LSD1, GATA2, and RNA-POL-II at human CGA, CGB3, and ERVW1 gene loci. The signal from GATA2 ChIP samples that were further subjected to sequential ChIP with control IgG was considered as 1 to determine the relative enrichment (*, p < 0.001; three independent experiments). B and C, plots showing quantitative ChIP assessment of RNA-POL-II occupancy at the promoter region of human CGA, CGB3, and ERVW1 loci in control and LSD1KD BeWo cells (B) and control and LSD1KD CTBs (C) (signal from 0.2% of total input chromatin before immunoprecipitation was considered as 1 to generate the relative enrichment plot; *, p < 0.01; three independent experiments). The red dotted line indicates the average nonspecific enrichment using IgG as the negative control antibody for ChIP analyses. Error bars in all panels represent S.E.

Discussion

Epigenetic regulators, including histone-modifying enzymes, play critical roles in chromatin remodeling and influence gene expression patterns during cellular differentiation. LSD1 has been widely studied in influencing genome processes in various cellular contexts, including embryonic pluripotency, zygotic genome induction, cellular reprogramming, stem and progenitor cell differentiation, mammalian development, and cancers (43, 49, 71–81). The importance of LSD1 in the context of mouse trophoblast stem cell differentiation and mouse placentation has also been defined (36); however, its role in human trophoblast development and the placentation process remained largely unexplored. Our findings in this study establish LSD1 as an essential epigenetic regulator for human SynTB differentiation. We also identified that LSD1 could function as a transcriptional coactivator in human trophoblast cells by promoting H3K9Me2 demethylation at key SynTB gene loci.

One of our interesting findings is the synchronous existence of both H3K4Me2 and H3K9Me2 modifications at the transcriptionally repressed ERVW1, CGA, and CGB loci in undifferentiated CTBs. Bivalent histone modifications, in which functionally opposite histone modifications coexist at a chromatin region, are a common feature at the transcript start site of many developmentally regulated genes. Most of the known bivalent genes are associated with coexistence of repressive histone H3 lysine 27 trimethylation (H3K27Me3) and H3K4 trimethylation (H3K4Me3) modifications (82), which keep those genes at a transcriptionally “poised” state so they can readily be activated in response to the appropriate signal. Nevertheless, the presence of both H3K4Me2 and H3K9Me2 modifications at key SynTB gene loci indicates that these genes are at a poised bivalent state and LSD1-medited H3K9 demethylation is a key regulatory step to instigate their activation in response to SynTB differentiation cues. These data also indicate the possibility that the presence of the H3K4M2/H3K9Me2 bivalency and LSD1-mediated activation is a common regulatory mechanism at several other SynTB-associated genes during human placentation.

Our study implicated a LSD1–GATA2 gene regulatory axis that directly controls RNA-POL-II recruitment at GATA2 target genes to promote transcriptional activation during SynTB differentiation (Fig. 6). Our findings also support a recent study, which showed that CTB to SynTB differentiation is associated with increased RNA-POL-II binding to promoters of a subset of genes (83). However, we found that GATA2 is also expressed in the undifferentiated BeWo cells.

Figure 6.

The LSD1–GATA2 gene regulatory axis during SynTB differentiation. The model illustrates an LSD1–GATA2 gene regulatory axis that directly controls RNA-POL-II recruitment at GATA2 target genes to promote transcriptional activation during SynTB differentiation. From our experimental data, we propose that in the undifferentiated CTBs, SynTB-associated genes such as CGA harbor both H3K4Me2 and H3K9Me2 modifications, leading to a relatively compact chromatin inaccessible to GATA2 binding. The lack of GATA2 binding in turn results in impaired RNA-POL-II recruitment and suppression of transcription. In response to cell signaling like PKA signaling, a LSD1–GATA2 complex forms at the SynTB-associated genes, which leads to H3K9Me2 demethylation by LSD1 and instigates RNA-POL-II recruitment and gene transcription.

Thus, the question arises of what prevents GATA2 chromatin occupancy at the ERVW1/CGA/CGB gene loci in undifferentiated BeWo cells. One of the possibilities is the inaccessibility of GATA motifs due to the presence of the repressive H3K9Me2 modifications at those chromatin loci in undifferentiated BeWo cells. We predict that the induction of LSD1-mediated H3K9Me2 demethylation allows accessibility of GATA motifs, thereby allowing GATA2 binding and RNA-POL-II recruitment (Fig. 6).

Zhu et al. (36) indicated that loss of LSD1 in mouse TSCs promotes SynTB differentiation, which is different from our findings in the context of human CTBs in which LSD1 is essential for the differentiation process. An explanation for this differential outcome could be the differences in the placentation process in humans versus mice. Both human and mouse develop hemochorial placentae and are regulated by common conserved factors. However, the placentation processes in these two species are fundamentally different. Thus, it is possible that LSD1 mediates its function in trophoblast progenitors in a species-specific manner. As LSD1 can interact with multiple chromatin regulators, the differential interactions of LSD1 with other protein partners could lead to species-specific function during placentation. An alternative explanation is the improper SynTB differentiation efficiency of mouse TSCs. The mouse TSCs show a spontaneous propensity to differentiate to trophoblast giant cells and only partially recapitulate the SynTB differentiation process (84, 85). Hence, future gene-knockout studies in which LSD1 is selectively deleted in SynTB progenitors during mouse placentation could definitively indicate whether or not LSD1 mediates a conserved role in SynTB development in both mouse and human placentation.

An interesting finding of this study is the consistent expression of LSD1 in CTBs and SynTBs during the first-trimester human placentation process. These expression patterns indicate that LSD1 function could contribute to SynTB differentiation during the first trimester of pregnancy. Defective trophoblast development during first-trimester placentation is a major reason for early pregnancy loss or contributes to pregnancy-associated disorders during late gestation (86–89).

Thus, it is important to understand whether impairment of LSD1 function during first-trimester placentation contributes to placental defects. Unfortunately, the villous CTB progenitors of a first-trimester placenta are distinct from CTBs of a term placenta as they do not spontaneously differentiate to SynTBs in culture. Thus, studying the importance of LSD1 for SynTB differentiation in first-trimester CTBs is technically challenging. Also, the BeWo cells are not a proper cell system to model the first-trimester CTBs. However, recently developed human trophoblast stem cells are described to recapitulate the properties of CTB progenitors of a first-trimester placenta as those cells can be efficiently differentiated to both SynTBs and extravillous trophoblasts (90). Thus, human TSCs could be utilized to model the importance of LSD1 in early human trophoblast development.

The high-level expression of LSD1 in CTBs within the first-trimester placenta also raises the question of its importance in undifferentiated CTBs. As discussed earlier, LSD1 can also act as a corepressor by interacting with CoREST–histone deacetylase or NuRD complex. Our unpublished studies6 revealed that RCOR1, which encodes CoREST, and components of the NuRD complex, including MBD2/3, CHD4, and RBBP4, are highly expressed in first-trimester CTBs. Thus, it is attractive to hypothesize that the corepressor function of LSD1 plays an important role in regulating the biology of undifferentiated CTBs during first-trimester placentation.

In summary, in this study, we have provided experimental evidence to define LSD1 as an important regulator of CTB to SynTB differentiation. Based on its expression patterns during human placentation, we also propose that LSD1 is an important epigenetic regulator to orchestrate gene expression patterns in undifferentiated CTB progenitors. Given the dual mode of function as a coactivator and a corepressor, LSD1 could be an important therapeutic target to manipulate the gene expression program to manage pregnancy-associated disorders that originate from defective trophoblast development and function.

Experimental procedures

Cell culture and reagents

BeWo human choriocarcinoma cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium/F-12 medium with l-glutamine, 15 mm HEPES, 10% fetal bovine serum, and 2 μl/ml Primocin. For inducing syncytialization, BeWo cells were cultured for 24 h and then treated with 250 μm 8-bromoadenosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate (Sigma) for 72 h for SynTB differentiation. Human term CTBs were cultured in isobutylmethylxanthine/dexamethasone/insulin medium with 10% fetal bovine serum, 1% l-glutamine, and 1% penicillin–streptomycin. Cells were cultured for 72–96 h for SynTB differentiation.

Human placental tissues and isolation of CTBs from human term placenta

Studies with human placentae were performed after obtaining approval from the Institutional Review Board of the University of Kansas Medical Center. Formaldehyde-fixed sections of first-trimester and term human placentae were obtained from Research Centre for Women's and Infants' Health Biobank of Mount Sinai Hospital, Toronto, Canada. For isolation of CTBs, normal term placentae were obtained at the University of Kansas Medical Center following cesarean sections at birth. CTBs were isolated following an established protocol (91) with some modifications. Placental tissue was washed using one time with saline and digested with trypsin, Dispase, and DNase in Hanks' balanced salt solution buffered with HEPES. Digestion was done in a shaker incubator at 37 °C for 1 h. Additional trypsin and DNase were added after the first 30 min. The contents were then filtered into 50 ml of fetal bovine serum and subjected to a series of centrifugations. Pellets were resuspended in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium with 10% fetal bovine serum and added to a discontinuous Percoll gradient followed by centrifugation. Trophoblasts were identified by density and extracted for use in experiments.

Analysis of mRNA expression

Total RNA was extracted from cells and used to synthesize cDNA. cDNA synthesis and analysis by quantitative real-time PCR were done following a published procedure (92). The following human genes and corresponding primers were used: (i) CGA, 5′-tctggtcacattgtcggtgt-3′ and 5′-ttcctgtagcgtgcattctg-3′; (ii) CGB, 5′-gtgtgcatcaccgtcaacac-3′ and 5′-ggtagttgcacaccacctga-3′; (iii) KDM1A, 5′-ctactgtcgtgcctgggtct-3′ and 5′-tccttctctgctttggcatt-3′; GATA2, 5′-accactcatcaagcccaagc-3′ and 5′-aacaggtgccggctcttct-3′; (v) ERVW1 (SYNCYTIN1), 5′-ctaccccaactgcggttaaa-3′ and 5′-ggttcctttggcagtatcca-3′; and (vi) ERVFRD1 (SYNCYTIN2), 5′-ccaaattccctcctctcctc-3′ and 5′-cgggtgttagtttgcttggt-3′.

RNAi

Plasmids expressing shRNAs targeting human LSD1/KDM1A were obtained from Sigma. Lentiviral supernatants were prepared in HEK293T cells following a procedure described previously (92), and viral particles were concentrated by centrifugation. Undifferentiated BeWo cells and term CTBs were transduced with lentiviral particles, and cells were selected with puromycin (1 μg/ml) for subsequent studies. The LSD1 target sequences 5′-GCCTAGACATTAAACTGAATA-3′ and 5′-CCACGAGTCAAACCTTTATTT-3′ specifically knocked down expression of LSD1 mRNA by ≥90%. However, the data generated with viral vectors expressing shRNA against LSD1 target sequence 5′-GCCTAGACATTAAACTGAATA-3′ are presented here. For control experiments, cells were infected with viral vectors expressing shRNA against LSD1 target sequence 5′-AGGAAGGCTCTTCTAGCAATA-3′, which did not knock down LSD1 expression or affect SynTB differentiation potential.

Western blot analysis

Whole-cell lysates were extracted with a lysis buffer. Electrophoresis was performed using a 10–12% polyacrylamide gel in Tris–glycine running buffer (pH 8.3). Proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore, Burlington, MA). Blocking was performed with 5% nonfat dry milk (Difco) in 20 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.6) (TBS with Tween). Primary antibody incubation, washing, secondary antibody incubation, and development of chemiluminescent signals were done following a protocol published previously (93).

Quantitative ChIP and sequential ChIP

Cells were collected, and protein–DNA cross-linking was achieved by treating the cells with 1% formaldehyde (Sigma) for 10 min at room temperature with gentle rocking. 125 mm glycine was added to quench the reaction. ChIP was completed using antibodies against LSD1, GATA2, RNA-POL-II, H3K4Me2, and H3K9Me2 following protocols established previously (94, 95). Mouse IgG1 was used as a negative control for antibody binding.

Sequential ChIP analyses were performed using a protocol described earlier (96). Cross-linked chromatin fragments were prepared from differentiated BeWo cells and immunoprecipitated with anti-GATA2 antibody. Eluted chromatin was reincubated with anti-LSD1, anti-RNA-POL-II, and mouse IgG1 for overnight at 4 °C in the presence of 50 μg/ml yeast tRNA. After immunoprecipitation, chromatins were reverse cross-linked, digested with proteinase K (Sigma), and purified. Amplification by real-time PCR was used to quantify precipitated DNA. Primers for ChIP studies were designed based on gene sequences available in human genome assembly GRCh38.p12 (available in the Ensemble genome browser). The conserved GATA motifs at human CGA locus were identified via genome alignment in ECR Browser (97) (https://ecrbrowser.dcode.org).7 Sequences of ChIP primers are available on request.

Immunofluorescence

The immunofluorescence procedure was adapted from a protocol published previously (66). Cells were washed with PBS and fixed on glass coverslips with 4% paraformaldehyde (Sigma) in PBS. Cells were permeabilized in 0.25% Triton X-100 in PBS and blocked with 10% fetal bovine serum in PBS with 1% Triton X-100. Primary antibody incubation was completed in 1 h followed by washing with 0.05% Triton X-100 in PBS and then secondary antibody (conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488 (green)) incubation for 30 min while shielded from light. Next, the cells were counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (Invitrogen) and observed under a fluorescence microscope (Leica, Buffalo Grove, IL). All incubations took place at room temperature.

Immunohistochemistry

Human placental sections were deparaffinized and rehydrated using Histoclear (National Diagnostics, Atlanta, GA) followed by decreasing ethanol gradient and distilled water. Antigen retrieval occurred using Reveal Decloaker in a Decloaking Chamber (Biocare Medical, Pacheco, CA) at 90 °C for 15 min. Peroxidase blocking was done using 3% hydrogen peroxide for 10 min at room temperature followed by blocking for nonspecific binding with 10% normal goat serum (Invitrogen) for 30 min. Primary antibody and secondary antibody incubations were done for 30 min using antibody dilution buffer (1% BSA, 0.3% Tween 20 in PBS (pH 8.0)) for secondary antibody (biotinylated anti-rabbit or -mouse IgG (heavy + light) (vector) with 0.05% normal human serum). Tissues were incubated with horseradish peroxidase–streptavidin (Life Technologies) for 10 min followed by 3,3′-diaminobenzidine chromogen solution (Dako, Carpinteria, CA) for color change and Mayer's hematoxylin solution (Sigma) for 5 min. Hematoxylin color change was achieved using warm, running tap water for ∼2 min. Dehydration of the tissue was achieved using distilled water, increasing ethanol gradient, and xylene. Stained tissues were imaged using a brightfield microscope (Nikon).

Antibodies

The following antibodies were used in the study: (i) anti-E-Cadherin, ab1416 (Abcam, Cambridge, MA); (ii) anti-KDM1A/LSD1, ab17721 (Abcam); (iii) anti-GATA2, ab109241 (Abcam), (iv) anti-RNA-POL-II, MMS-126R (Covance, Princeton, NJ); (v) H3K4Me2, ab7766 (Abcam); and (vi) H3K9Me2, ab1220 (Abcam).

Author contributions

J. M.-F., S. R., and P. H. formal analysis; J. M.-F., S. R., P. H., A. G., B. B., S. B., and A. P. investigation; J. M.-F. and C. W. M. methodology; J. M.-F. writing-original draft; A. G. validation; B. B. data curation; C. W. M. and S. P. conceptualization; S. P. supervision; S. P. writing-review and editing.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Md. Rashedul Islam and Ananya Ghosh for providing valuable comments.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants HD062546, HD098880, and HD079363 and Bridging Grant P20GM103418 under the Kansas Idea Network Of Biomedical Research Excellence (K-IBRE) (to S. P.) and a University of Kansas Biomedical Research Training Program grant (to B. B.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

This article contains Fig. S1.

A. Ganguly, P. Home, and S. Paul, unpublished data.

Please note that the JBC is not responsible for the long-term archiving and maintenance of this site or any other third party-hosted site.

- SynTB

- syncytiotrophoblast

- CTB

- cytotrophoblast

- LSD1

- lysine-specific demethylase 1

- ERVW1

- endogenous retrovirus group W member 1, envelope

- ERVFRD1

- endogenous retrovirus group FRD member 1, envelope

- CG

- chorionic gonadotropin

- hCG

- human chorionic gonadotrophin

- H3K9Me2

- histone H3 lysine 9 dimethylation

- RNA-POL-II

- RNA polymerase II

- PKA

- protein kinase A

- TSC

- trophoblast stem cell

- CoREST

- corepressor to the transcription factor REST

- NuRD

- nucleosome remodeling and deacetylase

- AR

- androgen receptor

- ER

- estrogen receptor

- 8-Br-cAMP

- 8-bromo-cAMP

- KD

- knocked down expression of a gene

- H3K27Me3

- histone H3 lysine 27 trimethylation.

References

- 1. Soares M. J., Varberg K. M., and Iqbal K. (2018) Hemochorial placentation: development, function, and adaptations. Biol. Reprod. 99, 196–211 10.1093/biolre/ioy049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Knöfler M., Haider S., Saleh L., Pollheimer J., Gamage T. K. J. B., and James J. (2019) Human placenta and trophoblast development: key molecular mechanisms and model systems. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 76, 3479–3496 10.1007/s00018-019-03104-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. James J. L., Carter A. M., and Chamley L. W. (2012) Human placentation from nidation to 5 weeks of gestation. Part I: what do we know about formative placental development following implantation? Placenta 33, 327–334 10.1016/j.placenta.2012.01.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Boss A. L., Chamley L. W., and James J. L. (2018) Placental formation in early pregnancy: how is the centre of the placenta made? Hum. Reprod. Update 24, 750–760 10.1093/humupd/dmy030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Baird D. D., Weinberg C. R., McConnaughey D. R., and Wilcox A. J. (2003) Rescue of the corpus luteum in human pregnancy. Biol. Reprod. 68, 448–456 10.1095/biolreprod.102.008425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Haider S., Meinhardt G., Saleh L., Fiala C., Pollheimer J., and Knöfler M. (2016) Notch1 controls development of the extravillous trophoblast lineage in the human placenta. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, E7710–E7719 10.1073/pnas.1612335113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Beer A. E., and Sio J. O. (1982) Placenta as an immunological barrier. Biol. Reprod. 26, 15–27 10.1095/biolreprod26.1.15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yang M., Lei Z. M., and Rao Ch. V. (2003) The central role of human chorionic gonadotropin in the formation of human placental syncytium. Endocrinology 144, 1108–1120 10.1210/en.2002-220922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Costa M. A. (2016) The endocrine function of human placenta: an overview. Reprod. Biomed. Online 32, 14–43 10.1016/j.rbmo.2015.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cole L. A. (2012) hCG, the wonder of today's science. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 10, 24 10.1186/1477-7827-10-24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. PrabhuDas M., Bonney E., Caron K., Dey S., Erlebacher A., Fazleabas A., Fisher S., Golos T., Matzuk M., McCune J. M., Mor G., Schulz L., Soares M., Spencer T., Strominger J., et al. (2015) Immune mechanisms at the maternal-fetal interface: perspectives and challenges. Nat. Immunol. 16, 328–334 10.1038/ni.3131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chamley L. W., Holland O. J., Chen Q., Viall C. A., Stone P. R., and Abumaree M. (2014) Review: where is the maternofetal interface? Placenta 35, (suppl.) S74–S80 10.1016/j.placenta.2013.10.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mi S., Lee X., Li X., Veldman G. M., Finnerty H., Racie L., LaVallie E., Tang X. Y., Edouard P., Howes S., Keith J. C. Jr., and McCoy J. M. (2000) Syncytin is a captive retroviral envelope protein involved in human placental morphogenesis. Nature 403, 785–789 10.1038/35001608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mallet F., Bouton O., Prudhomme S., Cheynet V., Oriol G., Bonnaud B., Lucotte G., Duret L., and Mandrand B. (2004) The endogenous retroviral locus ERVWE1 is a bona fide gene involved in hominoid placental physiology. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 1731–1736 10.1073/pnas.0305763101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Blaise S., de Parseval N., Bénit L., and Heidmann T. (2003) Genomewide screening for fusogenic human endogenous retrovirus envelopes identifies syncytin 2, a gene conserved on primate evolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 13013–13018 10.1073/pnas.2132646100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Policastro P. F., Daniels-McQueen S., Carle G., and Boime I. (1986) A map of the hCG β-LH β gene cluster. J. Biol. Chem. 261, 5907–5916 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Talmadge K., Vamvakopoulos N. C., and Fiddes J. C. (1984) Evolution of the genes for the β subunits of human chorionic gonadotropin and luteinizing hormone. Nature 307, 37–40 10.1038/307037a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fiddes J. C., and Talmadge K. (1984) Structure, expression, and evolution of the genes for the human glycoprotein hormones. Recent Prog. Horm. Res. 40, 43–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zimmermann G., Ackermann W., and Alexander H. (2012) Expression and production of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) in the normal secretory endometrium: evidence of CGB7 and/or CGB6 β hCG subunit gene expression. Biol. Reprod. 86, 87 10.1095/biolreprod.111.092429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bo M., and Boime I. (1992) Identification of the transcriptionally active genes of the chorionic gonadotropin β gene cluster in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 267, 3179–3184 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kim H. S., Roh C. R., Chen B., Tycko B., Nelson D. M., and Sadovsky Y. (2007) Hypoxia regulates the expression of PHLDA2 in primary term human trophoblasts. Placenta 28, 77–84 10.1016/j.placenta.2006.01.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Soncin F., Natale D., and Parast M. M. (2015) Signaling pathways in mouse and human trophoblast differentiation: a comparative review. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 72, 1291–1302 10.1007/s00018-014-1794-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kliman H. J., Nestler J. E., Sermasi E., Sanger J. M., and Strauss J. F. 3rd (1986) Purification, characterization, and in vitro differentiation of cytotrophoblasts from human term placentae. Endocrinology 118, 1567–1582 10.1210/endo-118-4-1567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Orendi K., Gauster M., Moser G., Meiri H., and Huppertz B. (2010) The choriocarcinoma cell line BeWo: syncytial fusion and expression of syncytium-specific proteins. Reproduction 140, 759–766 10.1530/REP-10-0221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pattillo R. A., and Gey G. O. (1968) The establishment of a cell line of human hormone-synthesizing trophoblastic cells in vitro. Cancer Res. 28, 1231–1236 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wice B., Menton D., Geuze H., and Schwartz A. L. (1990) Modulators of cyclic AMP metabolism induce syncytiotrophoblast formation in vitro. Exp. Cell Res. 186, 306–316 10.1016/0014-4827(90)90310-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Liu F., Soares M. J., and Audus K. L. (1997) Permeability properties of monolayers of the human trophoblast cell line BeWo. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 273, C1596–C1604 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.273.5.C1596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Renaud S. J., Chakraborty D., Mason C. W., Rumi M. A., Vivian J. L., and Soares M. J. (2015) OVO-like 1 regulates progenitor cell fate in human trophoblast development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, E6175–E6184 10.1073/pnas.1507397112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gupta S. K., Malhotra S. S., Malik A., Verma S., and Chaudhary P. (2016) Cell signaling pathways involved during invasion and syncytialization of trophoblast cells. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 75, 361–371 10.1111/aji.12436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chang C. W., Wakeland A. K., and Parast M. M. (2018) Trophoblast lineage specification, differentiation and their regulation by oxygen tension. J. Endocrinol. 236, R43–R56 10.1530/JOE-17-0402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Knott J. G., and Paul S. (2014) Transcriptional regulators of the trophoblast lineage in mammals with hemochorial placentation. Reproduction 148, R121–R136 10.1530/REP-14-0072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Loregger T., Pollheimer J., and Knofler M. (2003) Regulatory transcription factors controlling function and differentiation of human trophoblast—a review. Placenta 24, Suppl. A, S104–S110 10.1053/plac.2002.0929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Baczyk D., Drewlo S., Proctor L., Dunk C., Lye S., and Kingdom J. (2009) Glial cell missing-1 transcription factor is required for the differentiation of the human trophoblast. Cell Death Differ. 16, 719–727 10.1038/cdd.2009.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Cheng Y. H., and Handwerger S. (2005) A placenta-specific enhancer of the human syncytin gene. Biol. Reprod. 73, 500–509 10.1095/biolreprod.105.039941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Steger D. J., Hecht J. H., and Mellon P. L. (1994) GATA-binding proteins regulate the human gonadotropin α-subunit gene in the placenta and pituitary gland. Mol. Cell. Biol. 14, 5592–5602 10.1128/MCB.14.8.5592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zhu D., Hölz S., Metzger E., Pavlovic M., Jandausch A., Jilg C., Galgoczy P., Herz C., Moser M., Metzger D., Günther T., Arnold S. J., and Schüle R. (2014) Lysine-specific demethylase 1 regulates differentiation onset and migration of trophoblast stem cells. Nat. Commun. 5, 3174 10.1038/ncomms4174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Shi Y., Lan F., Matson C., Mulligan P., Whetstine J. R., Cole P. A., Casero R. A., and Shi Y. (2004) Histone demethylation mediated by the nuclear amine oxidase homolog LSD1. Cell 119, 941–953 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Amente S., Lania L., and Majello B. (2013) The histone LSD1 demethylase in stemness and cancer transcription programs. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1829, 981–986 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2013.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kozub M. M., Carr R. M., Lomberk G. L., and Fernandez-Zapico M. E. (2017) LSD1, a double-edged sword, confers dynamic chromatin regulation but commonly promotes aberrant cell growth. F1000Res 6, 2016 10.12688/f1000research.12169.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lee M. G., Wynder C., Cooch N., and Shiekhattar R. (2005) An essential role for CoREST in nucleosomal histone 3 lysine 4 demethylation. Nature 437, 432–435 10.1038/nature04021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Shi Y. J., Matson C., Lan F., Iwase S., Baba T., and Shi Y. (2005) Regulation of LSD1 histone demethylase activity by its associated factors. Mol. Cell 19, 857–864 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.08.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wang Y., Zhang H., Chen Y., Sun Y., Yang F., Yu W., Liang J., Sun L., Yang X., Shi L., Li R., Li Y., Zhang Y., Li Q., Yi X., and Shang Y. (2009) LSD1 is a subunit of the NuRD complex and targets the metastasis programs in breast cancer. Cell 138, 660–672 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Whyte W. A., Bilodeau S., Orlando D. A., Hoke H. A., Frampton G. M., Foster C. T., Cowley S. M., and Young R. A. (2012) Enhancer decommissioning by LSD1 during embryonic stem cell differentiation. Nature 482, 221–225 10.1038/nature10805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Nair S. S., Li D. Q., and Kumar R. (2013) A core chromatin remodeling factor instructs global chromatin signaling through multivalent reading of nucleosome codes. Mol. Cell 49, 704–718 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.12.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Metzger E., Wissmann M., Yin N., Müller J. M., Schneider R., Peters A. H., Günther T., Buettner R., and Schüle R. (2005) LSD1 demethylates repressive histone marks to promote androgen-receptor-dependent transcription. Nature 437, 436–439 10.1038/nature04020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Wissmann M., Yin N., Müller J. M., Greschik H., Fodor B. D., Jenuwein T., Vogler C., Schneider R., Günther T., Buettner R., Metzger E., and Schüle R. (2007) Cooperative demethylation by JMJD2C and LSD1 promotes androgen receptor-dependent gene expression. Nat. Cell Biol. 9, 347–353 10.1038/ncb1546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Perillo B., Ombra M. N., Bertoni A., Cuozzo C., Sacchetti S., Sasso A., Chiariotti L., Malorni A., Abbondanza C., and Avvedimento E. V. (2008) DNA oxidation as triggered by H3K9me2 demethylation drives estrogen-induced gene expression. Science 319, 202–206 10.1126/science.1147674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Garcia-Bassets I., Kwon Y. S., Telese F., Prefontaine G. G., Hutt K. R., Cheng C. S., Ju B. G., Ohgi K. A., Wang J., Escoubet-Lozach L., Rose D. W., Glass C. K., Fu X. D., and Rosenfeld M. G. (2007) Histone methylation-dependent mechanisms impose ligand dependency for gene activation by nuclear receptors. Cell 128, 505–518 10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ahmed M., and Streit A. (2018) Lsd1 interacts with cMyb to demethylate repressive histone marks and maintain inner ear progenitor identity. Development 145, dev160325 10.1242/dev.160325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Latos P. A., Goncalves A., Oxley D., Mohammed H., Turro E., and Hemberger M. (2015) Fgf and Esrrb integrate epigenetic and transcriptional networks that regulate self-renewal of trophoblast stem cells. Nat. Commun. 6, 7776 10.1038/ncomms8776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Castex J., Willmann D., Kanouni T., Arrigoni L., Li Y., Friedrich M., Schleicher M., Wöhrle S., Pearson M., Kraut N., Méret M., Manke T., Metzger E., Schüle R., and Gunther T. (2017) Inactivation of Lsd1 triggers senescence in trophoblast stem cells by induction of Sirt4. Cell Death Dis. 8, e2631 10.1038/cddis.2017.48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Schmidt A., Morales-Prieto D. M., Pastuschek J., Fröhlich K., and Markert U. R. (2015) Only humans have human placentas: molecular differences between mice and humans. J. Reprod. Immunol. 108, 65–71 10.1016/j.jri.2015.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Dupressoir A., Vernochet C., Bawa O., Harper F., Pierron G., Opolon P., and Heidmann T. (2009) Syncytin-A knockout mice demonstrate the critical role in placentation of a fusogenic, endogenous retrovirus-derived, envelope gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 12127–12132 10.1073/pnas.0902925106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Wu D., Xu Y., Zou Y., Zuo Q., Huang S., Wang S., Lu X., He X., Wang J., Wang T., and Sun L. (2018) Long noncoding RNA 00473 is involved in preeclampsia by LSD1 binding-regulated TFPI2 transcription in trophoblast cells. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 12, 381–392 10.1016/j.omtn.2018.05.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Xu Y., Wu D., Liu J., Huang S., Zuo Q., Xia X., Jiang Y., Wang S., Chen Y., Wang T., and Sun L. (2018) Downregulated lncRNA HOXA11-AS affects trophoblast cell proliferation and migration by regulating RND3 and HOXA7 expression in PE. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 12, 195–206 10.1016/j.omtn.2018.05.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Wu D., Yang N., Xu Y., Wang S., Zhang Y., Sagnelli M., Hui B., Huang Z., and Sun L. (2019) lncRNA HIF1A antisense RNA 2 modulates trophoblast cell invasion and proliferation through upregulating PHLDA1 expression. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 16, 605–615 10.1016/j.omtn.2019.04.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Knöfler M., and Pollheimer J. (2013) Human placental trophoblast invasion and differentiation: a particular focus on Wnt signaling. Front. Genet. 4, 190 10.3389/fgene.2013.00190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Harris L. K., Keogh R. J., Wareing M., Baker P. N., Cartwright J. E., Whitley G. S., and Aplin J. D. (2007) BeWo cells stimulate smooth muscle cell apoptosis and elastin breakdown in a model of spiral artery transformation. Hum. Reprod. 22, 2834–2841 10.1093/humrep/dem303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Wang J. M., Zhao H. X., Wang L., Gao Z. Y., and Yao Y. Q. (2013) The human leukocyte antigen G promotes trophoblast fusion and β-hCG production through the Erk1/2 pathway in human choriocarcinoma cell lines. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 434, 460–465 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Bernstein B. E., Kamal M., Lindblad-Toh K., Bekiranov S., Bailey D. K., Huebert D. J., McMahon S., Karlsson E. K., Kulbokas E. J. 3rd, Gingeras T. R., Schreiber S. L., and Lander E. S. (2005) Genomic maps and comparative analysis of histone modifications in human and mouse. Cell 120, 169–181 10.1016/j.cell.2005.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Koch C. M., Andrews R. M., Flicek P., Dillon S. C., Karaöz U., Clelland G. K., Wilcox S., Beare D. M., Fowler J. C., Couttet P., James K. D., Lefebvre G. C., Bruce A. W., Dovey O. M., Ellis P. D., et al. (2007) The landscape of histone modifications across 1% of the human genome in five human cell lines. Genome Res. 17, 691–707 10.1101/gr.5704207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Orford K., Kharchenko P., Lai W., Dao M. C., Worhunsky D. J., Ferro A., Janzen V., Park P. J., and Scadden D. T. (2008) Differential H3K4 methylation identifies developmentally poised hematopoietic genes. Dev. Cell 14, 798–809 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.04.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Hublitz P., Albert M., and Peters A. H. (2009) Mechanisms of transcriptional repression by histone lysine methylation. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 53, 335–354 10.1387/ijdb.082717ph [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Peters A. H., Kubicek S., Mechtler K., O'Sullivan R. J., Derijck A. A., Perez-Burgos L., Kohlmaier A., Opravil S., Tachibana M., Shinkai Y., Martens J. H., and Jenuwein T. (2003) Partitioning and plasticity of repressive histone methylation states in mammalian chromatin. Mol. Cell 12, 1577–1589 10.1016/S1097-2765(03)00477-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Guo Y., Fu X., Huo B., Wang Y., Sun J., Meng L., Hao T., Zhao Z. J., and Hu X. (2016) GATA2 regulates GATA1 expression through LSD1-mediated histone modification. Am. J. Transl. Res. 8, 2265–2274 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Home P., Kumar R. P., Ganguly A., Saha B., Milano-Foster J., Bhattacharya B., Ray S., Gunewardena S., Paul A., Camper S. A., Fields P. E., and Paul S. (2017) Genetic redundancy of GATA factors in the extraembryonic trophoblast lineage ensures the progression of preimplantation and postimplantation mammalian development. Development 144, 876–888 10.1242/dev.145318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Paul S., Home P., Bhattacharya B., and Ray S. (2017) GATA factors: master regulators of gene expression in trophoblast progenitors. Placenta 60, Suppl. 1, S61–S66 10.1016/j.placenta.2017.05.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Bresnick E. H., Martowicz M. L., Pal S., and Johnson K. D. (2005) Developmental control via GATA factor interplay at chromatin domains. J. Cell. Physiol. 205, 1–9 10.1002/jcp.20393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Martowicz M. L., Grass J. A., and Bresnick E. H. (2006) GATA-1-mediated transcriptional repression yields persistent transcription factor IIB-chromatin complexes. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 37345–37352 10.1074/jbc.M605774200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Bresnick E. H., Lee H. Y., Fujiwara T., Johnson K. D., and Keles S. (2010) GATA switches as developmental drivers. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 31087–31093 10.1074/jbc.R110.159079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Adamo A., Atashpaz S., Germain P. L., Zanella M., D'Agostino G., Albertin V., Chenoweth J., Micale L., Fusco C., Unger C., Augello B., Palumbo O., Hamilton B., Carella M., Donti E., et al. (2015) 7q11.23 dosage-dependent dysregulation in human pluripotent stem cells affects transcriptional programs in disease-relevant lineages. Nat. Genet. 47, 132–141 10.1038/ng.3169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Adamo A., Sesé B., Boue S., Castaño J., Paramonov I., Barrero M. J., and Izpisua Belmonte J. C. (2011) LSD1 regulates the balance between self-renewal and differentiation in human embryonic stem cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 13, 652–659 10.1038/ncb2246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Di Stefano B., Collombet S., Jakobsen J. S., Wierer M., Sardina J. L., Lackner A., Stadhouders R., Segura-Morales C., Francesconi M., Limone F., Mann M., Porse B., Thieffry D., and Graf T. (2016) C/EBPα creates elite cells for iPSC reprogramming by upregulating Klf4 and increasing the levels of Lsd1 and Brd4. Nat. Cell Biol. 18, 371–381 10.1038/ncb3326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Ancelin K., Syx L., Borensztein M., Ranisavljevic N., Vassilev I., Briseño-Roa L., Liu T., Metzger E., Servant N., Barillot E., Chen C. J., Schüle R., and Heard E. (2016) Maternal LSD1/KDM1A is an essential regulator of chromatin and transcription landscapes during zygotic genome activation. Elife 5, e08851 10.7554/eLife.08851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Thambyrajah R., Mazan M., Patel R., Moignard V., Stefanska M., Marinopoulou E., Li Y., Lancrin C., Clapes T., Möröy T., Robin C., Miller C., Cowley S., Göttgens B., Kouskoff V., et al. (2016) GFI1 proteins orchestrate the emergence of haematopoietic stem cells through recruitment of LSD1. Nat. Cell Biol. 18, 21–32 10.1038/ncb3276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Takeuchi M., Fuse Y., Watanabe M., Andrea C. S., Takeuchi M., Nakajima H., Ohashi K., Kaneko H., Kobayashi-Osaki M., Yamamoto M., and Kobayashi M. (2015) LSD1/KDM1A promotes hematopoietic commitment of hemangioblasts through downregulation of Etv2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, 13922–13927 10.1073/pnas.1517326112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Saleque S., Kim J., Rooke H. M., and Orkin S. H. (2007) Epigenetic regulation of hematopoietic differentiation by Gfi-1 and Gfi-1b is mediated by the cofactors CoREST and LSD1. Mol. Cell 27, 562–572 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.06.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Wang J., Scully K., Zhu X., Cai L., Zhang J., Prefontaine G. G., Krones A., Ohgi K. A., Zhu P., Garcia-Bassets I., Liu F., Taylor H., Lozach J., Jayes F. L., Korach K. S., et al. (2007) Opposing LSD1 complexes function in developmental gene activation and repression programmes. Nature 446, 882–887 10.1038/nature05671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Tosic M., Allen A., Willmann D., Lepper C., Kim J., Duteil D., and Schüle R. (2018) Lsd1 regulates skeletal muscle regeneration and directs the fate of satellite cells. Nat. Commun. 9, 366 10.1038/s41467-017-02740-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Cai C., He H. H., Chen S., Coleman I., Wang H., Fang Z., Chen S., Nelson P. S., Liu X. S., Brown M., and Balk S. P. (2011) Androgen receptor gene expression in prostate cancer is directly suppressed by the androgen receptor through recruitment of lysine-specific demethylase 1. Cancer Cell 20, 457–471 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.09.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Harris W. J., Huang X., Lynch J. T., Spencer G. J., Hitchin J. R., Li Y., Ciceri F., Blaser J. G., Greystoke B. F., Jordan A. M., Miller C. J., Ogilvie D. J., and Somervaille T. C. (2012) The histone demethylase KDM1A sustains the oncogenic potential of MLL-AF9 leukemia stem cells. Cancer Cell 21, 473–487 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.03.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Voigt P., Tee W. W., and Reinberg D. (2013) A double take on bivalent promoters. Genes Dev. 27, 1318–1338 10.1101/gad.219626.113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Kwak Y. T., Muralimanoharan S., Gogate A. A., and Mendelson C. R. (2019) Human trophoblast differentiation is associated with profound gene regulatory and epigenetic changes. Endocrinology 160, 2189–2203 10.1210/en.2019-00144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Tanaka S., Kunath T., Hadjantonakis A. K., Nagy A., and Rossant J. (1998) Promotion of trophoblast stem cell proliferation by FGF4. Science 282, 2072–2075 10.1126/science.282.5396.2072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Quinn J., Kunath T., and Rossant J. (2006) Mouse trophoblast stem cells. Methods Mol. Med. 121, 125–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Jindal P., Regan L., Fourkala E. O., Rai R., Moore G., Goldin R. D., and Sebire N. J. (2007) Placental pathology of recurrent spontaneous abortion: the role of histopathological examination of products of conception in routine clinical practice: a mini review. Hum. Reprod. 22, 313–316 10.1093/humrep/del128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Robertson W. B., Brosens I., and Landells W. N. (1985) Abnormal placentation. Obstet. Gynecol. Annu. 14, 411–426 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Kroener L., Wang E. T., and Pisarska M. D. (2016) Predisposing factors to abnormal first trimester placentation and the impact on fetal outcomes. Semin. Reprod. Med. 34, 27–35 10.1055/s-0035-1570029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Smith G. C. (2004) First trimester origins of fetal growth impairment. Semin. Perinatol. 28, 41–50 10.1053/j.semperi.2003.10.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Okae H., Toh H., Sato T., Hiura H., Takahashi S., Shirane K., Kabayama Y., Suyama M., Sasaki H., and Arima T. (2018) Derivation of human trophoblast stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 22, 50–63.e6 10.1016/j.stem.2017.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Petroff M. G., Phillips T. A., Ka H., Pace J. L., and Hunt J. S. (2006) Isolation and culture of term human trophoblast cells. Methods Mol. Med. 121, 203–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Ray S., Dutta D., Rumi M. A., Kent L. N., Soares M. J., and Paul S. (2009) Context-dependent function of regulatory elements and a switch in chromatin occupancy between GATA3 and GATA2 regulate Gata2 transcription during trophoblast differentiation. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 4978–4988 10.1074/jbc.M807329200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Saha B., Home P., Ray S., Larson M., Paul A., Rajendran G., Behr B., and Paul S. (2013) EED and KDM6B coordinate the first mammalian cell lineage commitment to ensure embryo implantation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 33, 2691–2705 10.1128/MCB.00069-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Weinmann A. S., and Farnham P. J. (2002) Identification of unknown target genes of human transcription factors using chromatin immunoprecipitation. Methods 26, 37–47 10.1016/S1046-2023(02)00006-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Home P., Saha B., Ray S., Dutta D., Gunewardena S., Yoo B., Pal A., Vivian J. L., Larson M., Petroff M., Gallagher P. G., Schulz V. P., White K. L., Golos T. G., Behr B., et al. (2012) Altered subcellular localization of transcription factor TEAD4 regulates first mammalian cell lineage commitment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 7362–7367 10.1073/pnas.1201595109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Dutta D., Ray S., Home P., Saha B., Wang S., Sheibani N., Tawfik O., Cheng N., and Paul S. (2010) Regulation of angiogenesis by histone chaperone HIRA-mediated incorporation of lysine 56-acetylated histone H3.3 at chromatin domains of endothelial genes. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 41567–41577 10.1074/jbc.M110.190025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Ovcharenko I., Nobrega M. A., Loots G. G., and Stubbs L. (2004) ECR Browser: a tool for visualizing and accessing data from comparisons of multiple vertebrate genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, W280–W286 10.1093/nar/gkh355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.