Abstract

Purpose of Review

To describe a small city/rural area HIV prevention project (the Cross Border Project) implemented in Ning Ming County, Guangxi Province, China, and Lang Son province, Vietnam, and consider its implications for addressing the opioid/heroin epidemic in small cities/rural areas in the USA. The description and the outcomes of the Cross Border project were taken from published reports, project records, and recent data provided by local public health authorities. Evaluation included serial cross-sectional surveys of people who inject drugs to assess trends in risk behaviors and HIV prevalence. HIV incidence was estimated from prevalence among new injectors and through BED testing.

Recent Findings

The Cross Border project operated from 2002 to 2010. Key components of the project 2 included the use of peer outreach workers for HIV/AIDS education, distribution of sterile injection equipment and condoms, and collection of used injection equipment. The project had the strong support of local authorities, including law enforcement, and the general community. Significant reductions in risk behavior, HIV prevalence, and estimated HIV incidence were observed. Community support for the project was maintained. Activities have been continued and expanded since the project formally ended.

Summary

The Cross Border project faced challenges similar to those occurring in the current opioid crisis in US small cities/rural areas: poor transportation, limited resources (particularly trained staff), poverty, and potential community opposition to helping people who use drugs. It should be possible to adapt the strategies used in the Cross Border project to small cities/rural areas in the US opioid epidemic.

Keywords: Vietnam, China, Persons who inject drugs, HIV, Cross border

This special issue of Current HIV/AIDS Reports focuses on the special issues involved in providing harm reduction/substance use disorder treatment services in the small cities and rural areas that are currently experiencing the brunt of the opioid epidemic in the USA. There can be little doubt of the seriousness of the problems in these areas. Between 2000 and 2014, the rate of prescription-opioid overdose deaths nearly quadrupled (from 1.5 to 5.9 deaths per 100,000 persons), and admissions to substance abuse treatment linked to prescription opioids more than quadrupled between 2002 and 2012 [1]. Perhaps the most dramatic single instance of a negative consequence of the opioid epidemic in small city/rural areas is the 2014–2015 HIVoutbreak in Scott County, IN, in which there were 181 cases of new HIV infections associated with injecting drug use in a population of only 24,000 people [2].

Small cities and rural areas have historically lacked both HIV prevention and substance use treatment services, which are usually concentrated in large urban centers [3]. There are substantial problems for developing services in many small city/rural areas in the USA, including poor transportation systems, lack of trained professionals, and stigmatizing community attitudes toward persons who use opioid drugs and/or are infected with HIV.

The purpose of this paper is to describe an HIV prevention project conducted in small city/rural areas of the border area of southern China and northern Vietnam. This area faced many of the same issues as small city/rural areas in the USA, arguably to a greater extent, but was quite successful in reducing HIV transmission among people who inject drugs (PWID). Implications from the China-Vietnam Cross Border project experience for small city/rural areas in the USA will be discussed.

History of HIV Epidemic Among PWID in China and Vietnam

Until the early years of the twenty-first century, the “Golden Triangle” area of Laos, Thailand, and Myanmar (Burma) was the most important production area for heroin in the world. Heroin was transported out of the Triangle south and east to Thailand and northern Vietnam into southern China and Hong Kong and then distributed worldwide. As has happened in many areas throughout the world, heroin injecting developed along these transportation routes followed by HIV infection among PWID along these transportation routes [4, 5]. In the traditional opium-smoking Vietnam-China border area, the first step was smoking and inhaling heroin and then to more cost-effective heroin injection resulting in sharing of injection equipment and epidemics of HIV infection.

These heroin-injecting populations developed not only in cities but also in rural villages. Many of the villages in China, Vietnam, and Thailand were populated by ethnic minority “hill tribes,” (Karen, Lahu, Hmong, Lisu, Akha, Mien, and Padaung). The hill tribes were economically disadvantaged and also faced considerable discrimination.

History of the Cross Border Project

The “China-Vietnam Cross Border HIV Prevention Project” originated during discussions at a training for government health officials on HIV prevention among drug users that was held in Kunming, China in 1997. The fundamental premise of the project was that PWID in the China and Vietnam border areas often moved across the borders in order to obtain drugs and to avoid police activities, and would engage in injecting risk behavior on both sides of the border. Thus, successful HIV prevention for PWID in the border areas would require coordinated prevention programming in both southern China and northern Vietnam.

It took several years to fully organize the project, including coordinating governmental activities in China and Vietnam, obtaining funding for the interventions and their evaluation. The project became fully operational in 2002 and continued under various international funding sources through 2010.

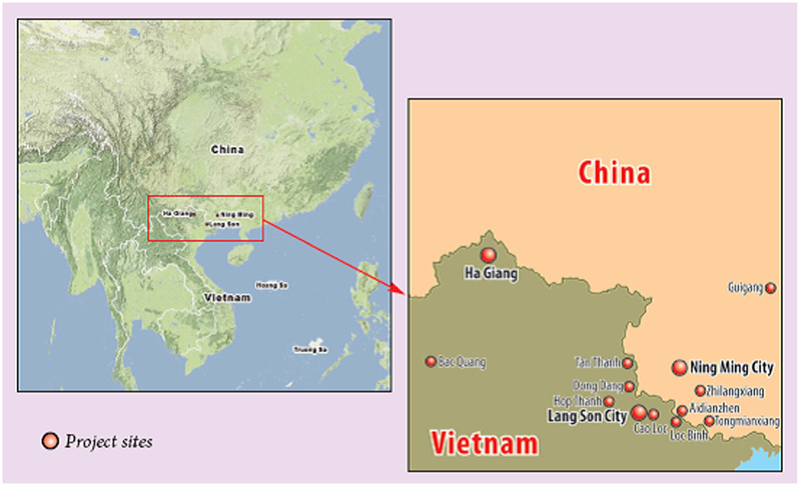

Figure 1 shows the general location of the China-Vietnam Cross Border project, and the specific cities and villages in which the project was implemented.

Fig. 1.

General location of the China-Vietnam Cross Border Project including specific cities and villages

The border area included small cities such as Ning Ming City, China, and Lang Son City, Vietnam, as well as small rural and remote mountainous villages. Transportation within the area and across the border was quite rudimentary. Many roads were unpaved, rutted, some of which required four-wheel drive vehicles to navigate during rainy periods. Some project sites could only be reached by motorbike, bicycle, or on foot. The project purchased bicycles to enable peer educators to reach some of the sites. The border itself runs through very mountainous terrain with only a few official crossings on paved roads. Otherwise, many people, and particularly PWID and those involved in drug trafficking, often crossed the border on narrow paths through the forests and mountains, with no official government monitoring or oversight.

At the time the project began, HIV prevalence was 17% in our project sites in Ning Ming County, Guangxi Province, China, and 46% among PWID in our sites in Lang Son Province, Vietnam. Prevalence was notably higher (odds ratio = 5.08, 95% CI 1.41 to 18.26) among ethnic minority (“hill tribes”) PWID compared to ethnic majority PWID in Ning Ming but not in Lang Son (Han in China, Kinh in Vietnam) [6, 7].

Organization and Activities of the Cross Border Project

The service activities of the project were initially funded jointly by the Ford Foundation and the National Institute on Drug Abuse, NIH, with later funding by the United Kingdom Department for International Development (DfID), the Global Fund for AIDS, Malaria and Tuberculosis, and an anonymous donor. The interventions were implemented by the health departments in Lang Son Province, Vietnam, and Ning Ming County and Guangxi Province, China. At the time, there were no community-based organizations working on HIV/AIDS in the area.

Peer outreach workers were paid modest stipends, provided education about HIV, distribution of sterile needles and syringes and sterile water ampoules for preparing injections. The peer workers were trained in outreach/harm reduction best practices by persons with experience in harm reduction work. The peer outreach workers also collected used injection equipment from injecting sites. The distribution of the sterile needles and syringes and the collection of used needles and syringes were separate activities and not done on an exchange basis.

Because some PWID were concerned about possessing injecting equipment if stopped by the police, the peer outreach workers also distributed pharmacy vouchers which the PWID could take to the exchange for sterile needles and syringes and ampoules of sterile water at participating pharmacies. The project then reimbursed the pharmacists for the injection supplies with a small additional reimbursement for their time and effort.

Peer workers were originally to be recruited from persons in the community with histories of drug injecting but who were no longer using. However, it was difficult to find enough former injectors so current injectors were also recruited. Methadone maintenance treatment would have been valuable for the outreach workers and PWID community in general but was not available in Lang Son or Ning Ming until the last few years of the project.

The project also conducted regular community sessions to educate the community about HIV and to build support for the project. These were led by outreach workers with participation by health department staff [8]. The relationships with and support from the police were also extremely important aspects of the project. In project sites, police generally allowed the interventions to be carried out without interference [9].

Evaluation Design

Evaluation of the interventions relied primarily on serial cross-sectional surveys of 245–331 PWID in the China sites and 327–342 PWID in Vietnam sites. Subjects were recruited through chain referral (“snowball sampling”). Interviews were conducted by Guangxi and Lang Son health department staff and blood samples were collected for HIV testing. Subjects were paid modest honoraria for their time and effort. These semi-annual surveys permitted us to conduct trend analyses for risk behavior and HIV prevalence. We also estimated HIV incidence over time using HIV prevalence among new injectors—persons who had been injecting for 5 years or less. HIV incidence was estimated assuming (1) all persons were HIV seronegative at the time they began injecting, (2) new injectors who were HIV seropositive at the time of interview had been infected with HIV at the midpoint between their time of first injection and the time of interview, and (3) no new injectors had been lost to the injecting population. The numerator for the incidence estimate was the total number of HIV seropositive new injectors and the denominator was the total time since the first injection among the HIV seronegative new injectors and one half the time since the first injection for the HIV seropositive new injectors. Later in the project, we were able to add BED testing for recent HIV infection. The two methods were highly correlated [10].

Evaluation Results

During the Cross Border interventions, HIV risk behaviors and HIV prevalence among PWID were dramatically reduced, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

HIV risk behaviors and HIV prevalence PWID in the Cross Border Project Sites

| Indicator | Ning Ming County, China | Lang Son Province, Vietnam | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (2002) (%) | 2008 (%) | p value | Baseline (2002) (%) | 2009 (%) | p value | |

| Receptive sharing of needles/syringes | 47 | 10 | < 0.001 | 5 | 1 | 0.004 |

| Distributive sharing of needles/syringes | 52 | 10 | < 0.001 | 6 | <1 | < 0.001 |

| Sharing of any injection equipment | 76 | 15 | < 0.001 | 47 | 12 | < 0.001 |

| HIV prevalence | 17 | 11 | 0.003 | 46 | 23 | < 0.001 |

Source: Hammett TM, Des Jarlais DC, Kling R, Binh KT, McNicholl JM, Wasinrapee P, McDougal JS, Liu W, Chen Y, Meng D, Doan N, Nguyen TH, Hoang QN, Hoang TV. Controlling HIVepidemics among injection drug users: 8 years of Cross Border HIV prevention interventions in Vietnam and China. PLoS One 2012, 7(8): e43141. [11]

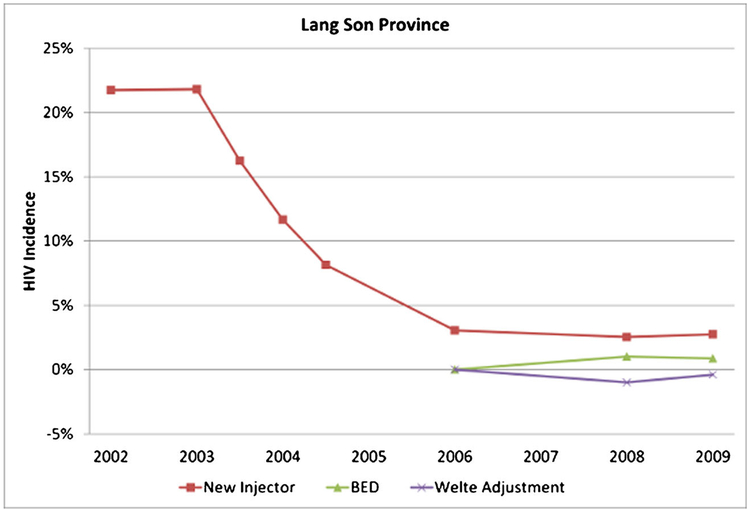

Figures 2 and 3 show the estimated annual HIV incidence by three methods (new injector, BED, and adjusted BED) over the course of the project, revealing substantial reductions in both sites.

Fig. 2.

Estimated annual HIV incidence by three methods (new injector, BED, and adjusted BED) in Ning Ming County Guangxi Province China

Fig. 3.

Estimated annual HIV incidence by three methods (new injector, BED, and adjusted BED) in Lang Son Province, Vietnam

The apparent rebound in HIV incidence among new injectors in Ning Ming toward the end of the project period requires some explanation. We believe that these later results may be unreliable, particularly given the much lower HIV incidence for these same waves based on BED testing. The new injector estimation method relies on an assumption that a new injector was HIV negative at the time he initiated injection. While this may have been a safe assumption for the early survey waves when the HIV epidemic was growing sharply among PWID, it may not be reliable for the later waves when the epidemic had become more mature and more sexual transmission had begun to occur. In these later waves, it is possible that an individual could already have been infected with HIV through sexual contact by the time he initiated injection, which would distort the incidence estimate upward. As a result, we are inclined to give more credence to the BED-based incidence estimates, especially for the later survey waves.

Update on Additional Interventions and Decline in Prevalence in Cross Border Sites

HIV prevention and care services for PWID have been continued and expanded in both Lang Son and Ning Ming since funding ended for the Cross Border Project in 2010. In Ning Ming, additional funding was obtained from national, provincial, and local governments for HIV prevention and care for PWID. The government has made HIV/AIDS prevention and care a high priority for the entire province, with multiple interventions for PWID, commercial sex workers (CSWs), men-who-have-sex-with men (MSM) and client of sex workers. HIV prevalence has continued to decline among PWID and is currently at 5% (Yi Chen, unpublished data).

In Lang Son Province, in 2017, there were a total of 1321 patients on methadone maintenance in six clinics, and a total of 653 persons receiving ART in six clinics. Funding has been provided by the Global Fund for AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, the World Bank, and the US Centers for Disease Control. HIV prevalence among PWID is currently 10% (Dr. Binh Kieu, unpublished data).

Updated HIV incidence estimates are not available for Ning Ming County or Lang Son province but the continued downward trends in HIV prevalence among PWID indicate that HIV incidence has remained low. (Note that the current prevalence includes PWID on ART, which would keep prevalence from declining rapidly.)

Application to US Small Cities/Rural Areas

As noted above the Cross Border project faced many challenges:

HIV prevalence among PWID was already quite high in both provinces at the start of the project. It was too late to prevent an HIV epidemic in the area.

PWID resided in small cities and rural areas and there was very poor transportation among the sites.

Most PWID and much of the general population were quite poor. Subsistence farming was the most common occupation in the area.

There was considerable stigmatization of both HIV infection and injecting drug use.

Many PWID belonged to highly stigmatized ethnic minority groups.

There were no community-based organizations delivering HIV/AIDS services.

Police and local authorities were generally hostile to PWID, who were often arrested and sent to compulsory drug detention centers.

The project sites were situated along a major overland heroin distribution route, so that there was a plentiful supply of very inexpensive heroin.

From our experience, these challenges were overcome through the following factors.

A strong commitment by local authorities to using a harm reduction approach to reducing HIV among PWID. This included providing the services at no cost to the PWID.

Cooperation from the police who generally did not interfere with the interventions.

The use of peer workers, including active drug users, to deliver information and safer injection supplies to PWID.

Outside experts in harm reduction provided guidance in best practices for HIV prevention for PWID. This greatly reduced the need for trial and error learning in the project.

The cooperation of community pharmacists in providing safer injection supplies.

Continuing community education to reduce stigmatization and reinforce the importance of reducing HIV infection among PWID. Collection of used needles and syringes by outreach workers contributed to community safety and won the project substantial community support

Adaptability during the implementation of the project, including changing to the use of active drug users as outreach workers and the development of the pharmacy voucher program.

The initial successes of the Cross Border Project were consolidated by the later addition of additional services—methadone maintenance treatment and antiretroviral treatment.

We believe that many challenges for addressing the opioid epidemic in small cities/rural areas in the USA will be similar to the challenges in the Cross Border project. We also believe that the Cross Border Project strategies for overcoming the challenges should be applicable to the US small city/rural areas. While we do propose the Cross Border project as a model, we must also emphasize the need for thoughtful adaptation of the Cross Border strategies to specific situations in the USA. There are obviously many differences between rural Southeast Asia and rural USA. However, a crucial lesson applicable to both settings is that it is possible to reduce the harms associated with opioid/heroin use in rural areas.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the invaluable contributions of the Guangxi Province, Ning Ming County, and Lang Son Province Health Departments, the peer outreach workers, the research participants and the evaluation funding provided by the National Institute on Drug Abuse, Ford Foundation, and an anonymous donor.

Footnotes

Competing Interests The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on The Global Epidemic

References

- 1.Compton WM, Jones CM, Baldwin GT. Relationship between nonmedical prescription-opioid use and heroin use. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:154–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peters PJ, Pontones P, Hoover KW, Patel MR, Galang RR, Shields J, et al. HIV infection linked to injection use of oxymorphone in Indiana, 2014–2015. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:229–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Des Jarlais DC, Nugent A, Solberg A, Feelemyer J, Mermin J, Holtzman D. Syringe service programs for persons who inject drugs in urban, suburban, and rural areas—United States, 2013. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR). 2015;64: 1337–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beyrer C, Razak MH, Lisam K, Chen J, Lui W, Yu X-F. Overland heroin trafficking routes and HIV-1 spread in south and south-east Asia. Aids. 2000;14:75–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stimson G. Reconstruction of subregional diffusion of HIV infection among injecting drug users in southeast Asia: implications for early intervention. Aids. 1994;8:1630–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Des Jarlais DC, Johnston P, Friedmann P, Kling R, Liu W, Ngu D, et al. Patterns of HIV prevalence among injecting drug users in the cross-border area of Lang Son Province, Vietnam, and Ning Ming County, Guangxi Province, China. BMC Public Health. 2005;5:89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Des Jarlais D, Kling R, Hammett T, Ngu D, Liu W, Chen Y, et al. Reducing HIV infection among new injecting drug users in the China-Vietnam Cross Border Project. AIDS. 2007;21:S109–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hammett T, Norton G, Kling R, Liu W, Chen Y, Ngu D, et al. Community attitudes toward HIV prevention for injection drug users: findings from a cross-border project in southern China and northern Vietnam. Journal of Urban Health. 2005;82:iv34–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hammett TM, Bartlett NA, Chen Y, Ngu D, Cuong DD, Phuong NM, et al. Law enforcement influences on HIV prevention for injection drug users: observations from a cross-border project in China and Vietnam. Int J Drug Policy. 2005;16:235–45. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shah NS, Duong YT, Le L-V, Tuan NA, Parekh BS, Ha HTT, et al. Estimating false-recent classification for the limiting-antigen avidity EIA and BED-capture enzyme immunoassay in Vietnam: implications for HIV-1 incidence estimates. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 2017;33:546–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hammett TM, Des Jarlais DC, Kling R, Kieu BT, McNicholl JM, Wasinrapee P, et al. Controlling HIV epidemics among injection drug users: eight years of cross-border HIV prevention interventions in Vietnam and China. PLoS One. 2012;7:e43141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]