Abstract

Objective:

Autoimmune pathologies are a growing aspect of medicine. Knowledge about atypical cases is essential. This report will describe a case of unusual, alternating fluctuations in thyroid function.

Methods:

We report a case of thyrotoxicosis alternating with hypothyroidism in a 44-year-old, African-American woman and detail the clinical course and management.

Results:

The patient presented in a mildly thyrotoxic state with features of thyroiditis that resolved soon thereafter. Subsequently, the course shifted toward a hypothyroid state with a thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) level of 24.53 μIU/ml (normal range is 0.45 to 4.5 μIU/ml; measured September 5, 2013) and free thyroxine (FT4) of 0.35 ng/dL (normal range is 0.5 to 1.40 ng/dL; measured September 5, 2013). It ensued with alternating hypothyroid and hyperthyroid trajectories for several cycles. Clinical management was adjusted to negotiate each progression. During certain intervals, levothyroxine was increased. At other visits, it was decreased. Periods without medication were observed as well. Furthermore, methimazole and metoprolol were utilized when required. Reversal of the condition occurred repeatedly. The entire course is tracked with over 30 instances of thyroid function measures that included hypothyroid, euthyroid (TSH at 1.54 μIU/mL, FT4 at 1.16 ng/dL) and thyrotoxic states (TSH at <0.005 μIU/mL, FT4 at 2.67 ng/dL). Various antibody titers were elevated including thyroid-stimulating immunoglobulin, thyroid peroxidase antibody, and TSH receptor antibody. Close monitoring of TSH and FT4 allowed for appropriate medication dose adjustment.

Conclusion:

This case highlights the unusual phenomenon of fluctuating thyroid function with autoimmune involvement of thyroid-stimulating immunoglobulin and TSH receptor antibodies. Close follow up aided responsive clinical management throughout the fluctuating clinical course.

INTRODUCTION

The current prevalence of autoimmune thyroid disease is estimated at 5% (1). Typically, one might expect a rapid rise of thyroid hormone release with concomitant inflammation from an acute thyroiditis (2). A brief hypothyroid state can ensue thereafter but generally resolves, and up to 90% of patients are euthyroid within 15 weeks (3). That being said, nearly 10% of patients may become hypothyroid and require permanent levothyroxine replacement (3). Following this, thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) monitoring allows for determining an optimal and generally consistent therapeutic dose for each patient.

Rarely, patients may have recurrent fluctuations in thyroid function (4). Moreover, alternating trajectories of thyroid function may further puzzle practitioners. Antagonistic stimulatory and inhibitory TSH receptor antibodies in thyroid function cycling have been implicated in the past (5). In this case report, we describe a long-term course of alternating thyroid function in a patient.

CASE REPORT

A 44-year-old, African-American female presented to the emergency department with recurrent episodes of palpitations associated with generalized weakness, anxiety, and jitteriness. Vital signs at the time were otherwise stable, save for mild tachycardia with a heart rate of 99 beats per minute. The patient had no other reported complaints including no neck pain or discomfort. Past medical history was significant for hypertension and human immunodeficiency virus infection that were both regularly monitored, treated, and controlled. Initially, the patient was given anxiolytic medication and referred for outpatient follow up with cardiology.

Her symptoms persisted at the follow-up visit, so her blood pressure medication was changed; amlodipine was discontinued and metoprolol was started given her persistent tachycardia. Thyroid function tests were performed as well, and the results revealed an elevated free thyroxine (FT4) and low TSH (FT4 was 3.75ng/dL, TSH was 0.02 μIU/mL; measured June 18, 2013).

Upon endocrinology consultation (August 15, 2013), the symptoms had resolved and the patient was no longer feeling weak, anxious, or jittery. The physical exam was normal and heart rate was controlled. No pertinent family history was reported. Metoprolol was continued and further investigations were ordered.

Repeat testing, approximately 2 months from the initial tests, showed improved results: the TSH became 1.73 μIU/mL (normal range is 0.45 to 4.50 μIU/mL) and the FT4 was decreased to just below normal at 0.46 ng/dL (normal range is 0.50 to 1.40 ng/dL). This change occurred without any thyro-modulating intervention. Moreover, total triiodothyronine was mildly low at 81 ng/dL (normal range is 87 to 178 ng/dL) as well. In addition, the 24-hour uptake with a thyroid scan using iodine-123 (on August 21, 2013) was significantly below normal at 3.6%. A subsequent neck ultrasound (August 28, 2013) was recorded as “Normal size gland, of normal morphology. Symmetric vascular signal. No focal masses, cystic or solid. There is a minimal bulge of the left side of the isthmus, which may contain a subcentimeter isoechoic, nodule.” Lastly, metoprolol was discontinued and no further treatment was initiated. A plan for a repeat ultrasound in 6 months' time for monitoring along with a needle biopsy would be pursued if growth was appreciated.

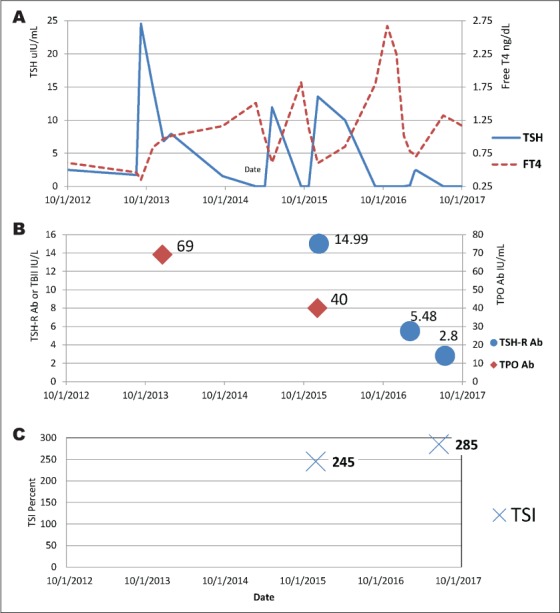

Yet, on follow up 3 weeks later, the patient had a slight intolerance to cold, coupled with dry skin and an interval weight gain of 2.7 kg. Mild pitting edema was noted as well. At this time, TSH had reversed with a marked increase to 24.53 μIU/mL and FT4 had decreased to 0.35 ng/dL (September 5, 2013). Levothyroxine therapy was initiated at 50 μg daily. The dose was titrated up first to 75 μg, and then later to 100 μg as TSH was persistently elevated on successive surveillance (Table 1). Thyroid antibodies were measured. Thyroid peroxidase antibodies were elevated at 69 IU/mL (normal range is 0 to 34 IU/mL; December 9, 2013). Continued fluctuations of TSH and FT4 in relation to autoimmune serology can be visualized over time in Figure 1.

Table 1.

Trends in Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone and Free Thyroxine Levels

| TSH* μIU/mL | FT4† ng/dL | Date | TSH* μIU/mL | FT4† ng/dL | Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.68 | 0.75 | 4/6/2010 | 0.01 | 1.82 | 9/17/2015 |

| 2.92 | 0.54 | 6/27/2011 | <0.01 | 1.13 | 10/22/2015 |

| 3.25 | 0.75 | 11/14/2011 | 13.54 | 0.60 | 12/3/2015 |

| 0.02 | 3.75 | 6/18/2013 | 9.99 | 0.85 | 4/7/2016 |

| 1.73 | 0.46 | 8/15/2013 | <0.01 | 1.79 | 8/25/2016 |

| 24.53 | 0.35 | 9/5/2013 | <0.01 | 2.67 | 10/20/2016 |

| 14.84 | 0.84 | 10/31/2013 | <0.01 | 2.25 | 12/1/2016 |

| 6.82 | 0.97 | 12/19/2013 | 0.01 | 1.01 | 1/5/2017 |

| 7.94 | 1.01 | 1/23/2014 | 0.15 | 0.78 | 2/2/2017 |

| 0.51 | NA | 6/5/2014 | 2.28 | 0.73 | 2/23/2017 |

| 1.54 | 1.16 | 9/18/2014 | 2.45 | 0.70 | 3/2/2017 |

| 0.02 | NA | 12/25/2014 | 1.06 | NA | 3/23/2017 |

| <0.01 | 1.51 | 2/19/2015 | 0.02 | 1.32 | 7/6/2017 |

| 0.01 | 1.05 | 3/26/2015 | <0.01 | 1.23 | 8/28/2017 |

| 0.02 | 0.98 | 4/2/2015 | <0.01 | 1.17 | 9/28/2017 |

| 11.92 | 0.61 | 5/5/2015 |

Abbreviations: FT4 = free thyroxine; NA = not available; TSH = thyroid-stimulating hormone.

*Normal range is 0.45 to 4.50 μIU/mL;

†normal range is 0.82 to 1.77 ng/dL.

Fig. 1.

Visual trends in TSH and FT4 (A), autoimmune antibodies (B), and TSI (C) levels. FT4 = free thyroxine; TPO Ab = thyroid peroxidase antibodies; TSH = thyroid-stimulating hormone; TSH-R Ab = thyrotropin receptor antibody; TSI = thyroid-stimulating immunoglobulin.

After 16 months, the patient presented again with complaints of palpitations, weight loss, and emotional lability. Levothyroxine was reduced from 100 μg to 75 μg. But later, repeat TSH was undetectable and FT4 was still elevated at 12.3 ng/dL. Subsequently, the levothyroxine dose was further decreased to 25 μg daily. Repeat TSH was suppressed at 0.008 μIU/mL and FT4 at 1.05 ng/dL (March 26, 2015). At this point, levothyroxine was totally stopped.

However, upon continued monitoring less than 2 months later, repeat TSH wholly reversed and was now elevated at 11.92 μIU/mL with a decreased FT4 of 0.61 ng/dL (May 5, 2015). Levothyroxine was then resumed at 50 μg daily. Within 6 months, TSH changed trajectory again and trended down to 0.011 μIU/mL and FT4 rose to 1.82 ng/dL (September 17, 2015). Levothyroxine was reduced to 25 μg daily. About a month later, on October 22, 2015, TSH continued to trend down to <0.005 μIU/mL and FT4 was 1.13 ng/dL. At this juncture, levothyroxine was reduced further to 25 μg every other day.

Later, within merely 2 months, the TSH upturned to 13.54 μIU/mL (December 3, 2015). Concurrently, thyroid peroxidase antibodies were elevated at 40 IU/mL (normal range is 0 to 34 IU/mL; December 3, 2015). Thyroid-stimulating immunoglobulin (TSI) was also simultaneously elevated at 245% (normal range is 0 to 139%) (Table 2). That same week, thyrotropin receptor antibody was also elevated at 14.99 IU/L (normal range is 0.00 to 1.75 IU/L; December 10, 2015). The patient was asymptomatic and continued with levothyroxine at 25 μg daily, up from every other day. Testing on January 26, 2016 revealed a further ascent of TSH to 27.58 μIU/mL and FT4 of 0.60 ng/dL. Levothyroxine dose was subsequently increased to 50 μg daily. The patient remained asymptomatic but the dose was further increased to 75 μg daily given repeat testing.

Table 2.

Autoimmune Serology

| Immunoprotein | Patient's value | Normal range | Date |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thyrotropin receptor antibody | 2.80 IU/L | 0.00–1.75 IU/L | 7/13/2017 |

| Thyroid-stimulating immunoglobulin | 285% | 0–139% | 7/13/2017 |

| Thyrotropin receptor antibody | 5.48 IU/L | 0.00–1.75 IU/L | 2/2/2017 |

| Thyrotropin receptor antibody | 14.99 IU/L | 0.00–1.75 IU/L | 12/10/2015 |

| Thyroid peroxidase antibodies | 40 IU/mL | 0–34 IU/mL | 12/3/2015 |

| Thyroid-stimulating immunoglobulin | 245% | 0–139% | 12/3/2015 |

| Thyroid peroxidase antibodies | 69 IU/mL | 0–34 IU/mL | 12/19/2013 |

| Anti-thyroglobulin antibody | <1.0 IU/mL | 0.0–0.9 IU/mL | 12/19/2013 |

Then, in August of 2016, the TSH declined to <0.005 μIU/mL and FT4 was 1.79 ng/dL. Reflexively, the levothyroxine dose was lowered to 50 μg daily. Incremental dose reductions were made to 37.5 μg as follow-up lab results were obtained. Eventually levothyroxine was stopped altogether once again on December 1, 2016 as TSH was still <0.005 μIU/mL and FT4 was 2.25 ng/dL. The patient remained asymptomatic throughout this period. Between January 5, 2017 and February 2, 2017, TSH gradually rose from 0.008 μIU/mL to 0.151 μIU/mL; the levothyroxine dose was held steady during this time. Thyroid receptor antibody was elevated at this point as well.

A thyroid scan was conducted on February 17, 2017 that showed a 24-hour iodine uptake of 22.15% (within the normal range) and no thyroid lesions were identified. This is in contrast to the original scan in 2013 that showed a poorly visualized right thyroid gland with 24-hour uptake significantly below normal at 3.6%. Also, a neck ultrasound was conducted that same day. It revealed that both lobes were enlarged but no discrete lesions were observed. The thyroid isthmus measured 0.5 cm and demonstrated a 0.2 × 0.4 × 0.5-cm, hypoechoic nodule. This was not dissimilar from the prior scan. No parathyroid bed mass was seen.

As the levothyroxine dose was held steady since December of 2016, the patient gradually trended with increasing levels of TSH and decreasing FT4 until March of 2017, when the direction reversed. On March 23, 2017, the TSH was slightly lower than before at 1.06 μIU/mL and continued to drop to 0.015 μIU/mL on July 6, 2017. Sensing a shift toward a hyperthyroid escapade, TSI level was measured and returned elevated at 285% (July 13, 2017; Fig. 1).

In August of 2017 the TSH level was undetectable, although the FT4 remained within normal range. During that time, the patient was asymptomatic. However, her blood pressure was elevated at 157/93 mm Hg. The pulse was not markedly elevated. A thyroid uptake scan using iodine-123 on August 8, 2017 displayed a 24-hour iodine uptake at 40.6%, normal-size right and left thyroid lobes, and no focally increased radiotracer uptake (hot nodules). On the other hand, no focally decreased radiotracer uptake (cold nodules) were recognized either. No extrathyroidal uptake or suspicious thyroid lesion was identified. The patient was diagnosed with subclinical thyrotoxicosis and restarted on oral metoprolol at 25 mg twice daily. Following this, methimazole was added at 5 mg daily. The patient is due for continued follow up for monitoring and adjustment of medication regimen. The saga continues until this day.

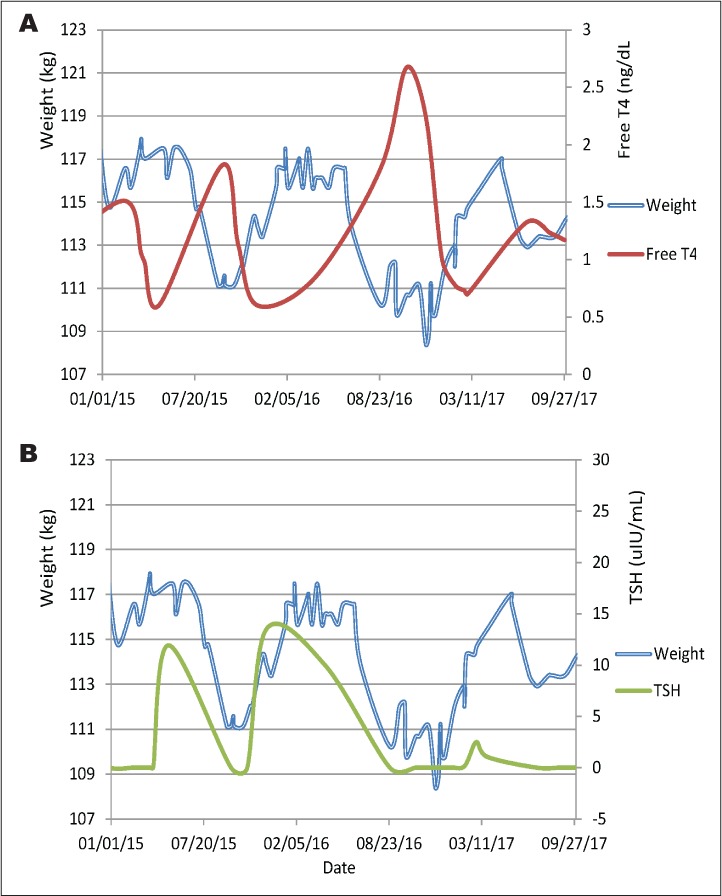

It is worth mentioning that the patient remained generally asymptomatic during follow up. However, her body weight tended to fluctuate in relation to levels of TSH and FT4 (Fig. 2). Separately, the patient had regular monitoring for human immunodeficiency virus management with an infectious disease specialist and was compliant with medication regimens. Her CD4 count was consistently above 500 since 2010. The patient adhered to a daily antiretroviral regimen that included ritonavir, emtricitabine/tenofovir, and atazanavir sulfate during the time interval examined. LabCorp (Burlington, NC) is the laboratory that conducted all antibody testing. It is important to note that LabCorp does not conduct functional assays to distinguish between stimulatory versus inhibitory subtypes.

Fig. 2.

Illustration of inverse trajectories of FT4 and body weight levels (A) as well as parallel trajectories of TSH and body weight (B) fluctuations with time. FT4 = free thyroxine; TSH = thyroid-stimulating hormone.

DISCUSSION

This case describes the clinical management of a patient with recurrent cycling of thyroid function that included both hyperthyroid and hypothyroid states over a 7-year period of time. The patient had documented reversals of her thyroid condition. Both states were directly observed with serial monitoring. The treatment regimen was adjusted to negotiate the patient's pathophysiologic trend. With the development of hypothyroidism, as corroborated by consistent incremental increases in TSH, the levothyroxine dose was adjusted to meet clinical demand. Yet, in the reverse direction, levothyroxine dosages were decreased. In addition, intervals of complete cessation of levothyroxine were encountered during this patient's clinical course.

The patient did not require therapy to directly quell hyperthyroid trajectories with thyroid ablation. Rather, the incursions self-resolved and later dipped back into hypothyroid states. Generally, intervals occurred over time periods of weeks to months and the patient's weight cycled within the same time periods (Fig. 2). Thus, body weight may be a handy presage indicating changes in thyroid function without blood testing.

Maintenance of stable TSH and FT4 levels was not possible with a regular dose over an extended period of time. Rather, the patient required close monitoring and frequent adjustment of levothyroxine doses to accommodate atypical fluctuations. Furthermore, there were intervals when the patient remained without any medication as TSH and FT4 levels did not warrant supplementation at that specific time. Nonetheless, reversion requiring supplementation did ensue. The remitting and relapsing sequence is revealing of a complex and unsettled clinical course.

Reasons that could explain this behavior are many. First might be lack of adherence to the prescribed medication regimen. It is not atypical of a patient to simply not comply with daily medication recommendations. In fact, the adherence rate for hypothyroidism treatment in one study was only 68% (6). Moreover, medication adherence in general may be lower in patients with comorbid conditions (6), such as in our case. However, the circumstances herein are wholly not consistent with medication non-adherence. Firstly, the patient's demeanor and approach to medical care was observed to be consistently serious and responsible. This was manifest in the patient's regular follow up at medical appointments that could at times reach twice monthly. This too required frequent laboratory testing. When asked about medication practice, the patient clearly iterated taking medication 30 to 60 minutes prior to breakfast every morning on an empty stomach. Therefore, while noncompliance is prevalent overall, it is unlikely for this individual patient. Medication administration time and technique, as mentioned already, were reviewed and deemed not to be a culprit either. Malabsorption is another real possibility for medication effectiveness (7), especially for patients with autoimmune diseases that could be at higher risk for celiac disease. Although celiac testing was not investigated in this case, it does not appear to be implicated as the patient remained in abnormal states even when thyroid medication was held.

This is not the first case reported with fluctuating thyroid function (4). Antagonistic stimulatory and inhibitory TSH receptor antibodies in thyroid function cycling have been described (7). Moreover, reverse shifts in thyroid function have been observed as well (8). Autoimmune derangements with dual opposing clinical effects can be implicated (9). Interestingly, in a study of 200 patients with hyperthyroid Graves disease, approximately 18% had blocking thyrotropin receptor antibodies (10). Therein, patients with the blocking thyrotropin receptor antibodies had a significantly higher prevalence of exophthalmos than patients without the antibody.

More pertinent to the case at hand, an analysis of auto-antibody “switching” (from hypothyroid to hyperthyroid state or vice versa) revealed differences of stimulatory and inhibitory antibody concentrations, and affinities in individual patients (9). Specific whole genome screening of rare switch patients to gain further understanding has been suggested (9). Altogether, careful monitoring is recommended to follow the clinical course (9,11). Ablative interventions followed by levothyroxine supplementation is a valid consideration in the repertoire of thyroid management for Graves disease, and may be reviewed in light of patient specific risks and benefits (12). One possible benefit to this treatment approach may be less frequent visitation and laboratory monitoring.

The extended time span described above is noteworthy. Additionally, the geared pivoting of clinical management as well contributes to the literature on this subject because the clinical practice utilized to meet this patient's continuously changing circumstances is elucidated. This extent of detail may benefit other physicians encountering similar perplexing cases. Furthermore, the existence of antagonistic autoimmune processes in thyroid function and clinical phenomena must continue to be recognized and discerned.

CONCLUSION

This case report describes a patient that displayed repeatedly fluctuating thyroid function with positive TSI and TSH receptor antibody. The dynamic conduct likely reflects independent competing autoimmune processes that may be responding to fluctuating triggers. Further investigation into the pathophysiology and prevalence of similar clinical states is warranted. Gaining a better understanding of autoimmune engagements with dual opposing clinical effects (9) may shed light on broader pathophysiologic states that propel autoimmune flairs in general.

In this scenario, the rapidity of thyroid function derangement, whether in a hyperthyroid or hypothyroid state, required regular follow up and close attention to patient-reported symptoms. Frequent laboratory testing helped guide dosing and adjustment of medications. In other words, “touch and go” management comes to the fore quite literally in this case. Patients with a similar clinical course may benefit from close monitoring as well.

Abbreviations:

- FT4

free thyroxine

- TSH

thyroid-stimulating hormone

- TSI

thyroid-stimulating immunoglobulin

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE

The authors have no multiplicity of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Antonelli A, Ferrari SM, Corrado A, Di Domenicantonio A, Fallahi P. Autoimmune thyroid disorders. Autoimmun Rev. 2015;14:174–180. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2014.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Caturegli P, De Remigis A, Rose NR. Hashimoto thyroiditis: clinical and diagnostic criteria. Autoimmun Rev. 2014;13:391–397. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2014.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hennessey JV. Subacute thyroiditis. In: De Groot LJ, Chrousos G, Dungan K, editors. Endotext. South Dartmouth, MA: MDText.com, Inc.; 2000–2018. , eds. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alzahrani AS, Aldasouqi S, Salam SA, Sultan A. Autoimmune thyroid disease with fluctuating thyroid function. PLoS Med. 2005;2:e89. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kraiem Z, Baron E, Kahana L, Sadeh O, Sheinfeld M. Changes in stimulating and blocking TSH receptor antibodies in a patient undergoing three cycles of transition from hypo to hyperthyroidism and back to hypothyroidism. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 1992;36:211–214. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.1992.tb00960.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Briesacher BA, Andrade SE, Fouayzi H, Chan KA. Comparison of drug adherence rates among patients with seven different medical conditions. Pharmacotherapy. 2008;28:437–443. doi: 10.1592/phco.28.4.437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Biondi B, Wartofsky L. Treatment with thyroid hormone. Endocr Rev. 2014;35:433–512. doi: 10.1210/er.2013-1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takasu N, Yamada T, Sato A et al. Graves' disease following hypothyroidism due to Hashimoto's disease: studies of eight cases. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 1990;33:687–698. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.1990.tb03906.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McLachlan SM, Rapoport B. Thyrotropin-blocking autoantibodies and thyroid-stimulating autoantibodies: potential mechanisms involved in the pendulum swinging from hypothyroidism to hyperthyroidism or vice versa. Thyroid. 2013;23:14–24. doi: 10.1089/thy.2012.0374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim WB, Chung HK, Park YJ et al. The prevalence and clinical significance of blocking thyrotropin receptor antibodies in untreated hyperthyroid graves' disease. Thyroid. 2000;10:579–586. doi: 10.1089/thy.2000.10.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fan W, Tandon P, Krishnamurthy M. Oscillating hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism – a case-based review. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2014;4 doi: 10.3402/jchimp.v4.25734. 25734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abraham P, Acharya S. Current and emerging treatment options for Graves' hyperthyroidism. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2010;6:29–40. doi: 10.2147/tcrm.s5229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]