Abstract

Background

There are controversies on the causal role of H. pylori in duodenal ulceration. Helicobacter pylori are curved gram-negative microaerophilic bacteria found at the layer of gastric mucous or adherent to the epithelial lining of the stomach. It’s a public health significance bacteria starting from discovery, and the prevalence and severity of the infection varies considerably among populations. H. pylori are a risk for various diseases, while the extent of host response like gastric inflammation and the amount of acid secretion by parietal cells affects the outcome of infection.

Method

Relevant literature were searched from databases such as Google Scholar, PubMed, Hinari, Web of Science, Scopus, and Science Direct.

Result

The review evidence supports a strong causal relation between H. pylori infection and duodenal ulcer, as patients are more likely to be infected by virulent strains which later cause duodenal ulceration. Thus, eradication of H. pylori infection decreases the incidence of duodenal ulcers, and prevents its recurrence by reducing both basal gastrin release and acid secretion without affecting parietal cell sensitivity. On the other hand, some studies show that H. pylori infection is not associated with the development of duodenal ulcers and such a lack of association revealed that duodenal ulceration has different pathogenesis.

Conclusion

Despite controversies observed in the causal role of H. pylori to duodenal ulceration by various studies, Hill criteria of causation proved the presence of a causal relation between H. pylori infection and duodenal ulcers. Other factors are also responsible for the development of duodenal ulcers and such factors are responsible for the differences in the prevalence of the diseases.

Keywords: H. Pylori, duodenal ulcer, causation, controversies

Introduction

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) are curved, gram-negative, microaerophilic bacteria1 found in the gastric mucous layer or adherent to the epithelial lining of the stomach.2 It has been a public health significance bacteria since 1983 as it infects the duodenum where hydrochloric acid and pepsin play a role in the digestion of food, which facilitates damage of the lining by gastric acid.3 H. pylori can elevate acid secretion in people who develop duodenal ulcers4 or hypersecretion of gastric acid can by itself evoke duodenal ulcers.5

The prevalence and the severity of the infection vary considerably among populations6 due to geographical differences and ways of leading life.4 In the US, 30–40% of people are infected with H. pylori7 and the prevalence is still high in Eastern Mediterranean countries of the healthy asymptomatic population.8 Most of the infection occurred during childhood with no difference in gender.9

Before the discovery of H. pylori, spicy food, acid, stress, and lifestyle were considered to be the causes of ulcers.2 Age, religion, and water sources are risk factors for H. pylori infection in Indonesia.10 Poor socio-economic status, genetic predisposition, and being resident in a developing country are among known risk factors for H. pylori infection.11 Sharing food or eating utensils, contact with contaminated water and with the stool, saliva, or vomit of an infected person are also potential risk factors.3,11

Dye endoscopy, forceps biopsies for culture, histology, and rapid urease test are used for diagnosis of H. pylori infection, and a patient is considered negative when the serum anti-H. pylori IgG and the three tests on biopsied specimens are all negative.12 H. pylori are associated with an increased risk for the development of duodenal and gastric ulcers, gastric adenocarcinoma, and gastric B-cell lymphoma.6,9 The bacterium attaches to epithelial cells of the stomach and duodenum, then it causes damage to the cells by secreting degradative enzymes (urease, lipases, and proteases) and bacterial virulence factors (cytotoxin-associated gene protein (CagA) and vacuolating cytotoxin (VacA)), and initiating a self-destructive immune response.13 Eradication of infection reduces the risk of duodenal ulcer,14 but the outcome depends on the extent of host response to the infection like gastric inflammation and the amount of acid secretion by parietal cells.4 This review article aims to explore the controversies on the causal role of H pylori in duodenal ulcers.

Methods

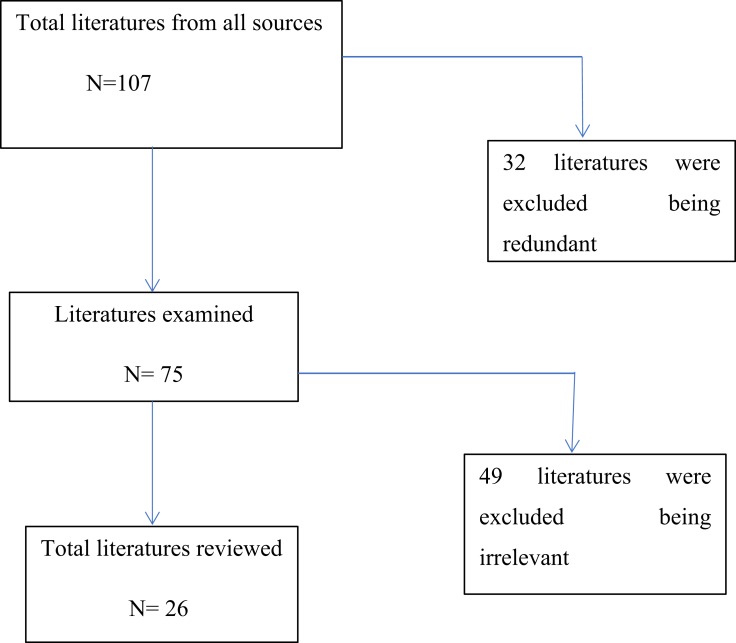

Studies were obtained from electronic databases, including Google Scholar, PubMed, Hinari, Web of Science, Scopus, and Science Direct, with hand searches and iterative reviews of reference lists of papers using the keywords “H. Pylori”, “duodenal ulcer”, “causation” and in combination from February 7–13, 2019. A total of 107 papers were obtained from all sources. After the exclusion of redundant and irrelevant literature, a total of 26 separate published empirical articles (Table 1) in peer-reviewed journals were reviewed. The searching process is displayed in Figure 1.

Table 1.

Study Characteristics Of Reviewed Articles

| No | Author | Study Design | Sample Size | Year | Country | Method | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Carrick J, Lee A, Hazell S, Ralston M, Daskalopoulos G | Cohort | 137 | 1989 | Australia | Congo Red staining | Strong risk factor (RR=51)21 |

| 2 | Moss SF, Calam J | Randomized clinical trial | 9 | 1993 | England | Endoscopy and biopsies | Eradication reduce basal plasma gastrin concentration (P<0.05), and basal acid secretion (P<0.01)39 |

| 3 | Reinbach DH, Cruickshank G, McColl KE | Matched hospital case control | 80 | 1993 | United Kingdom | Serum anti-H pylon IgG and ‘4C-urea breath tests | Prevalence 47%32 |

| 4 | Batista SA, et al | Experimental | 112 | 2011 | Brazil | Endoscopy | Number of EPIYA C segments did not associate with duodenal ulcer41 |

| 5 | Cekin AH, et al | Matched case control | 222 | 2012 | Turkey | Esophago-gastroduodenoscopy | H. pylori located in the corpus [OR]=3.00; incisura OR=2.07; and antrum [OR]=2.71. Hp positivity was 84.9%27 |

| 6 | Gisbert JP, et al | Cross-sectional | 774 | 1999 | Spain | Endoscopy | Prevalence 95.3%34 |

| 7 | Tsuji H, et al | Cross-sectional | 120 | 1999 | Japan | Endoscopic, rapid urease test and forceps biopsies | 1.7% H. pylori-negative rates12 |

| 8 | Gdalevich M, et al | Nested case control | 29 | 2000 | Israel | ELISA IgG-Ab | OR=3.831 |

| 9 | Khan MM, Shahzed MN, Jibran M, Rabbani MJ | Cross-sectional | 116 | 2009 | Pakistan | ACON® | 116 patients (92 males and 24 females) have perforated DU and more common in 30–50 age groups48 |

| 10 | Lario S, et al | Cohort | 88 | 2013 | Spain | Microarrays | Higher levels of IL8 and IL12p40 mRNAs and lower levels of GATA6 and SOCS2 mRNAs49 |

| 11 | Labenz JO, et al | Cross-sectional | 16 | 1996 | Germany | pH metry, glass electrode, urea breath test, culture, histology, and rapid urease | H. pylori eradication decrease the pH-increasing effect of omeprazole; P<0.00236 |

| 12 | Olbe L, Hamlet A, Dalenback J, Fandriks L | Cross-sectional | 16 | 1996 | Sweden | Urea breath test, culture, histology, and rapid urease | Inhibitory mechanism was restituted in 8 of 10 patients within 9 months after eradication of H. pylori infection5 |

| 13 | Chu KM, Kwok KF, Law S, Wong KH | Cross-sectional | 1343 | 2005 | China | Endoscopic, rapid urease test and biopsies | Male preponderance (M:F=2.5:1)13 |

| 14 | Syam AF, et al | Cross-sectional | 267 | 2014 | Indonesia | Culture, histology and rapid urease test |

Prevalence 22.1%10 |

| 15 | Segal ED, Cha J, Lo J, Falkow S, Tompkins LS | Laboratory | 1999 | USA | ELISA IgG-Ab | 145-kDa protein and activation of signal transduction pathways associated with the attachment of H. pylori19 | |

| 16 | Borody TJ, et al | Cohort | 302 | 1991 | Endoscopic, rapid urease test and biopsies | 94% were found to have associated H pylori44 | |

| 17 | Ng EK, et al | Cohort | 73 | 1996 | Intra-operative gastroscopy and antral biopsies | 70% had evidence of H. pylori33 | |

| 18 | Rauws EA, Tytgat GN | Randomized clinical trial | 50 | 1990 | Eradication achieved 7 of the 45 patients and there was no ulcer relapse during the first 12 months of follow-up38 | ||

| 19 | Patchett S, Beattie S, Leen E, Keane C, O’Morain C | Cohort | 51 | 1992 | Endoscopic, biopsies | Recurrence of H. pylori infection occurred in 35.3%29 | |

| 20 | Chan FK | Randomized clinical trial | 100 | 1997 | Hong Kong | Endoscopy | Eradication of H pylori before NSAID therapy reduces the occurrence16 |

| 21 | Blaser MJ, Chyou PH, Nomura A | Case control | 313 | 1995 | USA | H. pylori do not increases risk of developing duodenal ulcer40 | |

| 22 | Nomura A, Stemmermann GN, Chyou PH, Perez-Perez GI, Blaser MJ | Nested case control | 5443 | 1994 | USA | ELISA IgG-Ab | 92% patients and 78% of the matched controls had a positive test result, OR=4.028 |

| 23 | Kim JG, Graham DY | Cross-sectional | 181 | 1994 | ELISA IgG-Ab | 36% developed a duodenal ulcer45 | |

| 24 | Borody TJ, Brandl S, Andrews P, Jankiewicz E, Ostapowicz N | Cross-sectional | 115 | 1992 | Australia | Endoscopy | 47 (66%) no detectable causal factors, 21 (30%) regularly taking NSAIDs, and three (4%) had malignant GU17 |

| 25 | Bytzer P, Teglbjærg PS, Group DU | Randomized clinical trial | 276 | 2001 | Culture, immunohistochemistry, and urea breath test | Eradication therapy over 2 years is significantly poorer in H. pylori-negative patients7 | |

| 26 | Escobar MA, et al | Cross-sectional | 169 | 2004 | 12% of patients develop late complications26 |

Figure 1.

Data searching process.

The inclusion criteria were: type of study; randomized clinical trial, case-control, cohort, ecological, and cross-sectional, and systematic review, publication; academic journal (peer-reviewed) and non-reviewed reports, population; Global, time-period: 1989 to present, and language; English.

Result And Discussion

Evidence On Causal Relation Between H. pylori Infection And Duodenal Ulcer

H. pylori has a role in the etiology of duodenal ulcer.15–17 Once ingested, the attachment of H. pylori to epithelial cells of the stomach and duodenum occurs through phosphorylation of a 145 kilo Dalton protein and activation of signal transduction pathways.18,19 H. pylori infection blocks normal physiological mechanisms resulting in increased gastrin release and impaired inhibition of gastric acid secretion.18,20 Such endogenous hypersecretion of acid causes gastric metaplasia4 and synergizes ulceration.21 Thus, the prevalence of H. pylori infection in duodenal ulcer patients is higher than the normal population,22 as patients are more likely to be infected with virulent strains which later cause duodenal ulceration.23 The disease manifestations start when alteration of epithelial cell growth and enhanced apoptosis occur.24 H. pylori containing functional Cag pathogenicity island produce a vigorous inflammatory response,25 and 12% of patients develop late complications with a further 6% mortality rate.26

H. pylori plays a role in the pathogenesis of duodenal ulcer disease in 84.9% of subjects and the single causative factor in 44.1% of patients.27 Duodenal infection with H. pylori is a strong risk factor (RR=51),21 (OR=4)28 for the development of duodenal ulceration. Antral reinfection with H. pylori is also associated with relapse29 (RR=7.6).21 This evidence supports a strong causal relation between H. pylori infection and duodenal ulceration.30

Preexisting history of H. pylori is a risk for the development of duodenal ulcer,28 and it is observed that in young Israelis with an odds ratio of 3.8, the association increased as diagnosis time exceeded 2 years with 56.6% attributable risk.31

Although cigarette smoking, age, sex, and ingestion of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID) were not found to be significant risk factors for duodenal ulceration,21,32 H. pylori infection plays a role in the causation of non-NSAID-induced duodenal ulcer perforation.33 Excluding patients taking NSAIDs and/or antibiotics, H. pylori prevalence increased up to 99.1% (98.1±99.6%) among duodenal ulcer patients.34

The current therapy for H. pylori induced ulcer (a proton pump inhibitor and at least two antimicrobials with or without bismuth) is highly effective in eradicating the infection.9 Eradication of H. pylori infection decreases the incidence of duodenal ulcer and prevents its recurrence,22,35–37 and the occurrence of NSAID induced peptic ulcers16 without altering acid output.38 As a result, eradication resulted in falls in both basal gastrin release and acid secretion without affecting parietal cell sensitivity.39 On the other hand, the clinical outcome of eradication therapy over 2 years is significantly poorer in H. pylori-negative patients.7

Evidence Against Causal Relation Between H. pylori Infection And Duodenal Ulcer

A cohort study of 73 participants revealed that prior life acquisition of H. pylori was not associated with duodenal ulcer40 and only a minority of infected persons develop duodenal ulceration.22 This indicates that different pathogenesis had existed for duodenal ulceration.32 Moreover, H. pylori strain with high number of CagA EPIYA-C segments was not associated with duodenal ulcer.41

Duodenal ulcer can relapse after eradication of H. pylori infection, and the ulcer may remain healed after reduction of acid secretion in the presence of infection. Additionally, hypersecretion of gastric acid is strongly associated with the development of duodenal ulcers while it may result in a spontaneous eradication of H. pylori infection.23 The virulent strains cause delayed healing of an ulcer produced by acid hypersecretion42 by interfering with neoangiogenesis of wounded duodenal epithelial cells23 indicating the bacteria delay the healing of ulcer rather than causing it.

The annual proportion of patients with H. pylori-negative duodenal ulcers increased as the ulcers are more likely to occur in individuals with old age, pre-existing malignancy, recent surgery, underlying sepsis,43 NSAID use,43–45 a concomitant medical problem like Crohn’s disease and hypergastrinaemia,46 specific geographical distribution,47 and recent intake of antibiotics.44 Smoking and the presence of dietary lipids are also risk factors.4,23 Among 71 H. pylori-positive duodenal ulcer patients, 66% had no other detectable causal factors, 30% were regularly taking NSAIDs, and 4% had malignancy.17 Thus, H. pylori is not the primary cause of duodenal ulcer.47

Evaluation Of Causal Relation Between H. pylori Infection And Duodenal Ulcer Through Hill’s Criteria

The review assessed the causal relation between H. pylori infection and duodenal ulcer by using criteria for assessing causation proposed in 1965 by Sir Austin Bradford Hill. Despite controversies observed on the causal role of H. pylori to duodenal ulceration in various literature, Hill criteria of causation proved a causal relation between H. pylori infection and duodenal ulcer (Table 2).

Table 2.

Hill Criteria For Assessing The Causal Role Of H. Pylori On Duodenal Ulcer

| Sr. No | Hill Criteria’s | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Biological plausibility | Biologically plausible explanations for causation exist.18–20 |

| 2 | Dose response relationship | Eradication of H. pylori infection decreases the incidence of duodenal ulcer and prevents its recurrence.22,35–37,39 |

| 3 | Strength of association | Strong association.21,28,29 |

| 4 | Consistency | The association between H. pylori and duodenal ulcer has been consistently demonstrated in a number of different types of epidemiological studies (ecological, case-control, cohort, randomized clinical trial and cross-sectional). |

| 5 | Temporality | Proved in epidemiological studies (case-control, cohort, randomized clinical trial) |

| 6 | Study design | All types of epidemiological study designs (ecological, case-control, cohort, randomized clinical trial, and cross-sectional). |

| 7 | Reversibility | The removal of a possible cause (H. pylori) led to reduction of disease risk.22,35–37,39 |

| 8 | Specificity of association | No, exposure to H. pylori is also associated with other diseases like gastric ulcer,31,40 gastric cancer,28,41 gastro esophageal reflex disease.25 |

Conclusion

There are controversies among studies on the causal relation between H. pylori infection and duodenal ulcer. Several studies reported H. pylori is a strong risk factor for the development of duodenal ulcers, whereas other studies showed duodenal ulcers can recur after eradication of H. pylori infection, and the ulcer may remain healed after reduction of acid secretion in the presence of active infection, indicating the absence of a causal relation between H. pylori infection and duodenal ulcer. Despite controversies observed in the causal role of H. pylori to duodenal ulcer by various studies, critical examination of empirical evidence through Hill criteria of causation proved the presence of a causal relation between H. pylori infection and duodenal ulcer.

Acknowledgment

We are thankful to Wollo University for providing the necessary facilities for this work.

Abbreviations

H. pylori, Helicobacter pylori, NSAID, Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to data analysis, drafting or revising the article, gave final approval of the version to be published, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Mohebtash M. Helicobacter pylori and its effects on human health and disease. Arch Iran Med. 2011;14(3):192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. CDC. Helicobacter Pylori Fact Sheet for Health Care Providers.CDC Stacks. 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ra A, Tobe SW. Acute interstitial nephritis due to pantoprazole. Anns Pharmacother. 2004;38(1):41–45. doi: 10.1345/aph.1D085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Calam J, Baron J. ABC of the upper gastrointestinal tract: pathophysiology of duodenal and gastric ulcer and gastric cancer. Br Med J. 2001;323(7319):980. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7319.980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Olbe L, Fändriks L, Hamlet A, Svennerholm A-M, Thoreson A-C. Mechanisms involved in Helicobacter pylori induced duodenal ulcer disease: an overview. World J Gastroenterol. 2000;6(5):619. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v6.i5.619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cover TL, Blaser MJ. Helicobacter pylori in health and disease. Gastroenterology. 2009;136(6):1863–1873. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.01.073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bytzer P, Teglbjærg PS, Group DUS, Group US. Helicobacter pylori–negative duodenal ulcers: prevalence, clinical characteristics, and prognosis—results from a randomized trial with 2-year follow-up. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96(5):1409–1416. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03774.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eshraghian A. Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection among the healthy population in Iran and countries of the Eastern Mediterranean Region: a systematic review of prevalence and risk factors. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(46):17618. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i46.17618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Luman W. Helicobacter pylori: causation and treatment. JR Coll Physicians Edinburgh. 2005;(35):45–49. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Syam AF, Miftahussurur M, Makmun D, et al. Risk factors and prevalence of Helicobacter pylori in five largest islands of Indonesia: A preliminary study. PLoS One. 2015;10(11):e0140186. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0140186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Das JC, Paul N. Epidemiology and pathophysiology of Helicobacter pylori infection in children. J Indian Pediatr. 2007;74(3):287–290. doi: 10.1007/s12098-007-0046-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tsuji H, Kohli Y, Fukumitsu S, et al. Helicobacter pylori-negative gastric and duodenal ulcers. J Gastroenterol. 1999;34(4):455–460. doi: 10.1007/s005350050296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Costa AC, Figueiredo C, Touati E. Pathogenesis of Helicobacter pylori infection. Helicobacter. 2009;14:15–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2009.00702.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O’Morain C, et al. Current concepts in the management of Helicobacter pylori infection: the Maastricht III Consensus Report. Gut. 2007;56(6):772–781. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.101634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mégraud F, Lamouliatte H. Helicobacter pylori and duodenal ulcer. Dig Dis Sci. 1992;37(5):769–772. doi: 10.1007/bf01296437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chan FK, Sung JJ, Chung SS, et al. Randomised trial of eradication of Helicobacter pylori before non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug therapy to prevent peptic ulcers. Lancet. 1997;350(9083):975–979. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)04523-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Borody TJ, Brandl S, Andrews P, Jankiewicz E, Ostapowicz N. Helicobacter pylori-negative gastric ulcer. Am J Gastroenterol. 1992;87(10). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Graham DY, Go MF. Helicobacter pylori: current status. Gastroenterology. 1993;105(1):279–282. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(93)90038-e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Segal E, Cha J, Lo J, Falkow S, Tompkins L. Altered states: involvement of phosphorylated CagA in the induction of host cellular growth changes by Helicobacter pylori. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1999;96(25):14559–14564. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.25.14559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Olbe L, Hamlet A, Dalenback J, Fandriks L. A mechanism by which Helicobacter pylori infection of the antrum contributes to the development of duodenal ulcer. Gastroenterology. 1996;110(5):1386–1394. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v110.pm8613042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carrick J, Lee A, Hazell S, Ralston M, Daskalopoulos G. Campylobacter pylori, duodenal ulcer, and gastric metaplasia: possible role of functional heterotopic tissue in ulcerogenesis. Gut. 1989;30(6):790–797. doi: 10.1136/gut.30.6.790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kate V, Ananthakrishnan N, Tovey FI. Is Helicobacter pylori infection the primary cause of duodenal ulceration or a secondary factor? A review of the evidence. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2013;2013. doi: 10.1155/2013/425840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hobsley M, Tovey FI, Holton J. Controversies in the Helicobacter pylori/duodenal ulcer story. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2008;102(12):1171–1175. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2008.04.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tanih N, Ndip L, Clarke A, Ndip R. An overview of pathogenesis and epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection. Afr J Microbiol Res. 2010;4(6):426–436. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Graham DY, Yamaoka Y. H. pylori and cagA: relationships with gastric cancer, duodenal ulcer, and reflux esophagitis and its complications. Helicobacter. 1998;3(3):145–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Escobar MA, Ladd AP, Grosfeld JL, et al. Duodenal atresia and stenosis: long-term follow-up over 30 years. J Pediatr Surg. 2004;39(6):867–871. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2004.02.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cekin AH, Taskoparan M, Duman A, et al. The role of Helicobacter pylori and NSAIDs in the pathogenesis of uncomplicated duodenal ulcer. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2012;2012. doi: 10.1155/2012/585674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nomura A, Stemmermann GN, Chyou P-H, Perez-Perez GI, Blaser MJ. Helicobacter pylori infection and the risk for duodenal and gastric ulceration. Ann Intern Med. 1994;120(12):977–981. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-120-12-199406150-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Patchett S, Beattie S, Leen E, Keane C, O’Morain C. Helicobacter pylori and duodenal ulcer recurrence. Am J Gastroenterol. 1992;87(1). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Van Zanten SV, Sherman PM. Helicobacter pylori infection as a cause of gastritis, duodenal ulcer, gastric cancer and nonulcer dyspepsia: a systematic overview. Can Med Assoc J. 1994;150(2):177. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gdalevich M, Cohen D, Ashkenazi I, Mimouni D, Shpilberg O, Kark JD. Helicobacter pylori infection and subsequent peptic duodenal disease among young adults. Int J Epidemiol. 2000;29(3):592–595. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reinbach D, Cruickshank G, McColl K. Acute perforated duodenal ulcer is not associated with Helicobacter pylori infection. Gut. 1993;34(10):1344–1347. doi: 10.1136/gut.34.10.1344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ng E, Chung S, Sung J, et al. High prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in duodenal ulcer perforations not caused by non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Br J Surg. 1996;83(12):1779–1781. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800831237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gisbert J, Blanco M, Mateos J, et al. H. pylori-negative duodenal ulcer prevalence and causes in 774 patients. Dig Dis Sci. 1999;44(11):2295–2302. doi: 10.1023/a:1026669123593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rauws E. Eradication of Helicobacter pylori cures duodenal ulcer disease In: Helicobacter Pylori and Gastroduodenal Pathology. Springer; 1993:347–351. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Labenz J, Tillenburg B, Peitz U, et al. Helicobacter pylori augments the pH-increasing effect of omeprazole in patients with duodenal ulcer. Gastroenterology. 1996;110(3):725–732. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v110.pm8608881 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kandulski A, Selgrad M, Malfertheiner P. Helicobacter pylori infection: a clinical overview. Digestive Liver Dis. 2008;40(8):619–626. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2008.02.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rauws E, Tytgat G. Cure of duodenal ulcer associated with eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Lancet. 1990;335(8700):1233–1235. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)91301-P [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moss SF, Calam J. Acid secretion and sensitivity to gastrin in patients with duodenal ulcer: effect of eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Gut. 1993;34(7):888–892. doi: 10.1136/gut.34.7.888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Blaser MJ, Chyou P, Nomura A. Age at establishment of Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric carcinoma, gastric ulcer, and duodenal ulcer risk. Cancer Res. 1995;55(3):562–565. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Batista SA, Rocha GA, Rocha AM, et al. Higher number of Helicobacter pylori CagA EPIYA C phosphorylation sites increases the risk of gastric cancer, but not duodenal ulcer. BMC Microbiol. 2011;11(1):61. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-11-61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hobsley M, Tovey FI, Bardhan KD, Holton J. Does Helicobacter pylori really cause duodenal ulcers? No. Br Med J. 2009;339. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chu K-M, Kwok K-F, Law S, Wong K-H. Patients with Helicobacter pylori positive and negative duodenal ulcers have distinct clinical characteristics. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11(23):3518. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i23.3518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Borody TJ, George LL, Brandl S, et al. Helicobacter pylori-negative duodenal ulcer. Am J Gastroenterol. 1991;86(9). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kim JG, Graham DY. Helicobacter pylori infection and development of gastric or duodenal ulcer in arthritic patients receiving chronic NSAID therapy. Am J Gastroenterol. 1994;89(2):203–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hobsley M, Tovey FI, Holton J. Precise role of H pylori in duodenal ulceration. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12(40):6413. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i40.6413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hobsley M, Tovey F. Helicobacter pylori: the primary cause of duodenal ulceration or a secondary infection? World J Gastroenterol. 2001;7(2):149. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v7.i2.149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Khan MM, Shahzed MN, Jibran M, Rabbani MJ. Frequency of Helicobacter pylori infection in causation of duodenal ulcer perforation. Group. 2009. Jan 1;1(19/116):16–37 [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lario S, Ramirez-Lazaro MJ, Aransay AM, Lozano JJ, Montserrat A, Junquera F, Alvarez J, Segura F, Campo R, Calvet X. microRNA profiling in duodenal ulcer disease caused by Helicobacter pylori infection in a western population. Clinical microbiology and infection. 2012. Aug;18(8):E273–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]