Abstract

PURPOSE

Several studies have described the content of Twitter conversations about lung, breast, and prostate cancer, but little is known about how the public uses Twitter to discuss kidney cancer. We sought to characterize the content of conversations on Twitter about kidney cancer and the participants engaged in these dialogues.

METHODS

This qualitative study analyzed the content of 2,097 tweets that contained the key words kidney cancer from August 1 to 22, 2017. Tweets were categorized by content domain of conversations related to kidney cancer on Twitter and user types of participants in these dialogues.

RESULTS

Among the 2,097 kidney cancer–related tweets analyzed, 858 (41.4%) were authored by individuals, 865 (41.2%) by organizations, and 364 (17.4%) by media sites. The most common content discussed was support (29.3%) and treatment (26.5%). Among the 2,097 tweets, 825 were unique tweets, and 1,272 were retweets. The most common unique tweets were about clinical trials (23.9%), most often authored by media sites. The most common retweets were about treatment (38.5%), most often authored by organizations.

CONCLUSION

Twitter dialogues about kidney cancer are most commonly related to support and treatment. Our findings provide insights that may inform the design of new interventions that use social media as a tool to improve communication of kidney cancer information. Additional efforts are needed to improve our understanding of the value and direct utility of social media in improving kidney cancer care.

INTRODUCTION

Social media is a mode of communication that has transformed the way information is disseminated.1,2 Currently, 69% of US adults use at least one type of social media,3 and 59% of adults say that they have looked online for health information in the past year.4 Although earlier social media users were primarily young adults, the social media user base has become increasingly more representative of a more diverse population.3 Of note, older adult usage has grown in recent years, with social media engagement among adults ages 65 and older increasing from 7% to 37% between 2010 and 2018.3 Twitter, a microblogging social networking site, is one of the most popular social media platforms in the United States. According to the Pew Research Center, nearly one fourth of all adults who use social media are on Twitter. Among US adults who use social media, Twitter is most popular with women, adults ages 18 to 29 years, blacks, college graduates, and adults from urban communities.3 In addition, Twitter is an emerging medium in which cancer information is disseminated and is one of the most widely used social media platforms for cancer communication.5-10 Emerging evidence indicates that patients with cancer, their caregivers, and oncologists increasingly are using Twitter.11-13

The study of the use of Twitter in oncology is an evolving area of research. To better understand the nature and extent of social media–based cancer communication, several studies have examined the content of Twitter conversations about cancer. In general, cancer content on Twitter primarily focuses on delivering cancer information (eg, educational material) and emotional support.5,14-16 Studies have examined disease-specific content of Twitter conversations, including lung cancer, breast cancer, and prostate cancer.5 Twitter content related to disease-specific cancers often have distinguishing characteristics. For example, patients with breast cancer are more likely to tweet about their treatment than their diagnosis, whereas patients with prostate cancer are more likely to tweet about their diagnosis than their treatment.17 These differences underscore the need to examine the content of Twitter conversations across various tumor types. Moreover, to use social media effectively in improving cancer communication, a better understanding of the current landscape of Twitter conversations across tumor subtypes is needed.

Little is known about the content of Twitter discussions on kidney cancer and the participants who engage in these dialogues. Kidney cancer is one of the 10 most common malignancies diagnosed in the United States, with an estimated 65,340 diagnoses in 2018.18 In the past 10 years, a dramatic change has occurred in the management of kidney cancer as a result of the introduction of numerous targeted therapies and immunotherapeutic agents.2 These new treatment options have generated Twitter discussion in the field among patients, clinicians, researchers, advocacy communities, and pharmaceutical organizations.2,19 However, the content of conversations that exist on Twitter about kidney cancer remains unknown. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to describe how Twitter users are communicating about kidney cancer by characterizing the content, users, and dissemination of tweets related to kidney cancer.

METHODS

We used a qualitative content analysis study design adapted from our prior work.5 First, we used the Twitter search engine to identify 2,568 tweets that contained the key words kidney cancer from August 1 to 22, 2017. Second, we used NCapture, a Web-based tool of the qualitative data analysis software NVivo (version 10; QSR International, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia), to collect tweets directly from the Twitter Web page into Excel 2010 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA) for analysis. Third, we excluded 36 non-English tweets (1%) and 425 of those not related to kidney cancer (17%; eg, extraneous content, non sequiturs). Finally, we used content analysis methods to analyze and characterize our final sample of 2,097 (82%).20

The number of unique tweets and retweets (duplicate tweets) was calculated. Unique tweets were reviewed, and the content of each was categorized into the following domains: support, treatment, general information, clinical trials, diagnosis, donation, and prevention. Example tweets that best represent each content domain were selected and agreed upon by three authors (M.M.S., C.D.B., P.G.B.) who reviewed all individual tweets.

Three user categories were established (individual, organization, or media) on the basis of biographies provided on respective Twitter accounts. Individuals included self-identified patients, health professionals, and advocates, among others. Organizations included pharmaceutical companies and professional organizations, among others. Media included news and video outlets as well as blogs.

All individual tweets were reviewed independently by three authors (M.M.S., C.D.B., P.G.B.). Inter-rater agreement was tested and calculated with Cohen’s κ-coefficient (κ = 0.91; P = .005). Discrepancies were reviewed and adjudicated by consensus of the three reviewers. Descriptive statistics were used to characterize tweets and retweets by content and user. The study was reviewed and exempted by the City of Hope institutional review board.

RESULTS

Among the 2,097 tweets related to kidney cancer included in the final analysis, we found 825 (39.3%) unique tweets and 1,272 (60.7%) retweets (Table 1). The most common dialogues in the entire cohort were related to support (29.3%) and treatment (26.5%). The least prevalent tweets were those related to donation (5.2%) and prevention (1.1%).

TABLE 1.

Content Domains of Kidney Cancer–Related Tweets

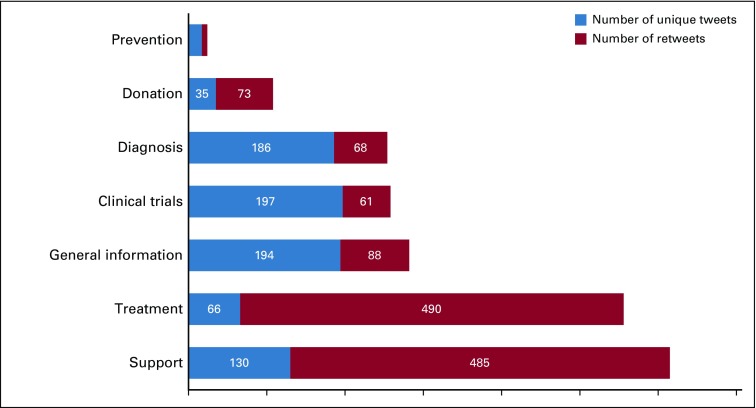

Among the 825 unique tweets, the most common dialogues were related to clinical trials (23.9%) and general information (23.5%). Among the 1,272 retweets, the majority of conversations were related to treatment (38.5%) and support (38.1%). Figure 1 shows the relative number of unique and duplicate tweets within each content domain.

FIG 1.

Content domains of 2,097 unique tweets and retweets. For Prevention, there were 17 unique tweets and 7 retweets.

Among the final sample of 2,097 kidney cancer–related tweets, conversations were generated by 858 (41.4%) individuals, 865 (41.2%) organizations, and 364 (17.4%) media sites. However, within each category of tweets, the user distribution varied (Fig 2). For example, individuals authored the largest proportion of tweets related to support (88.9%), organizations authored those related to treatment (86.3%), and media sites authored those related to clinical trials (45.7%).

FIG 2.

Content domains of 2,097 tweets from various user types. For Prevention, there was one Organization tweet.

DISCUSSION

This study is the first to our knowledge to characterize the content of conversations about kidney cancer and the participants who are engaged in these discussions. The findings reveal that conversations related to kidney cancer on Twitter are most commonly around support (29.3%) and treatment (26.5%). We also found that the majority of Twitter users engaged in dialogues about kidney cancer are individuals and organizations. Among the 2,097 tweets, 825 were unique tweets, and 1,272 were retweets. The most common unique tweets were about clinical trials (23.9%) and most often were authored by media sites. The most common retweets were about treatment (38.5%) and most often authored by organizations.

Three implications of this study add to the current evidence base on social media use in oncology. First, similar to previous studies, we observed a high prevalence of tweets about support in which a patient or loved one shared his or her history and/or asked for emotional or spiritual reassurance. This finding suggests that Twitter is a unique form of communication for kidney cancer because it provides a platform for peer support where patients, patient advocates, caregivers, and providers can offer, obtain, and exchange important resources to meet their emotional and psychological needs.5,10,19,21 Prior work has shown that peer support influences individual behavior in many health-related settings.22 Thus, social media may potentially offer a platform to provide a support network to improve the health behavior and quality of life of patients with kidney cancer. Moreover, the support content domain had the second highest retweet:tweet ratio. Prior work has shown that a retweet demonstrates support for the author of the original tweet, but the significance of a retweeted message remains unclear.23 Future studies are needed to examine how support interventions that use social media can be designed effectively.

Second, treatment was one of the most commonly discussed topics among Twitter users. Many tweets detailed novel therapies for metastatic kidney cancer (eg, frontline therapies such as cabozantinib plus nivolumab and ipilimumab, adjuvant sunitinib), which suggests that Twitter is a platform actively used for disseminating kidney cancer treatment information and relevant new research findings. This implication agrees with prior research that suggested that Twitter has the potential to help users to stay current on relevant advances in the medical field.24,25 Furthermore, the treatment content domain had the highest retweet:tweet ratio, with the majority of tweets and retweets produced by organizations (86%). This finding suggests active dissemination of treatment information among the kidney cancer Twitter community, particularly among organizations. Additional studies are needed to determine how to best use Twitter as a resource for kidney cancer treatment information.

Third, the large volume of unique tweets about kidney cancer clinical trials suggests that Twitter is emerging as a forum for sharing clinical trial information. These tweets primarily are authored by media sites, many of which provide links that contain enrollment information. This finding suggests that Twitter may potentially be leveraged to promote kidney cancer clinical trial information. Prior research has shown the potential utility of Twitter for cancer clinical trial recruitment, although little evidence of feasibility and effectiveness exists.26 Furthermore, although the clinical trial content domain has the highest volume of unique tweets about kidney cancer, it has the lowest retweet:tweet ratio, which may indicate that despite an active effort to share clinical trial content on Twitter, the information is not being disseminated effectively among users. To improve clinical trial Twitter use, additional studies are needed to measure the utility of social media for clinical trial recruitment and participation.

This study had several limitations. First, we selected a small sample of tweets over a short time frame; therefore, the findings may have limited generalizability. Second, no standard metrics exist in the literature for analyzing social media platforms; thus, our findings are limited by the qualitative content analysis we performed. However, we used multiple independent reviewers and rigorous qualitative methods to categorize tweets and ensured a high inter-rater agreement among the reviewers. Finally, our user categories are broad (eg, individuals, organizations, media) and do not reflect the granular diversity of users on Twitter (eg, patients, physicians, caregivers). However, by grouping users in these categories, we were more likely to characterize them accurately on the basis of the limited biographical information provided and were less likely to find inconsistencies in categorizations.

In summary, this study is the first to our knowledge to perform an exploratory analysis of Twitter content related to kidney cancer. Additional studies are needed to better understand the significance and value of social media conversations about kidney cancer as they relate to cancer care and research. For example, future research should focus on developing conceptual models and standard metrics on using social media to study human behavior. Efforts to incorporate machine learning into natural language processing for sentiment analysis have been made to address this challenge,27 but additional research is warranted to apply these methods to study cancer conversations on social media platforms. An understanding of the value of kidney cancer conversations on Twitter can inform the design of new interventions that leverage social media as a tool to improve cancer communication.

Footnotes

Supported by National Institutes of Health K12 Grant No. 5K12CA001727 (M.S.S.). The National Institutes of Health had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Mina S. Sedrak, Cristiane Decat Bergerot, Nazli Dizman, Sumanta K. Pal, Paulo Gustavo Bergerot

Collection and assembly of data: Meghan M. Salgia, Cristiane Decat Bergerot, Kemi Ashing-Giwa, Nazli Dizman, Sumanta K. Pal, Paulo Gustavo Bergerot

Data analysis and interpretation: Mina S. Sedrak, Meghan M. Salgia, Cristiane Decat Bergerot, Brendan N. Cotta, Jacob J. Adashek, Andrew R. Wong, Sumanta K. Pal, Paulo Gustavo Bergerot

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS’ DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/jco/site/ifc.

Mina S. Sedrak

Research Funding: Novartis (Inst)

Brendan N. Cotta

Employment: University of Miami

Sumanta K. Pal

Honoraria: Novartis, Medivation, Astellas Pharma

Consulting or Advisory Role: Pfizer, Novartis, Aveo Pharmaceuticals, Myriad Genetics, Genentech, Exelixis, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Astellas Pharma, Ipsen, Eisai

Research Funding: Medivation

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Attai DJ, Cowher MS, Al-Hamadani M, et al. Twitter social media is an effective tool for breast cancer patient education and support: Patient-reported outcomes by survey. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17:e188. doi: 10.2196/jmir.4721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Himelboim I, Han JY. Cancer talk on Twitter: Community structure and information sources in breast and prostate cancer social networks. J Health Commun. 2014;19:210–225. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2013.811321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pew Research Center Social Media Fact Sheet. 2018 http://www.pewinternet.org/fact-sheet/social-media

- 4.Fox S, Duggan M. Health Online 2013. http://www.pewinternet.org/2013/01/15/health-online-2013

- 5.Sedrak MS, Cohen RB, Merchant RM, et al. Cancer communication in the social media age. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2:822–823. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.5475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sedrak MS, Dizon DS, Anderson PF, et al. The emerging role of professional social media use in oncology. Future Oncol. 2017;13:1281–1285. doi: 10.2217/fon-2017-0161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Attai DJ, Sedrak MS, Katz MS, et al. Social media in cancer care: Highlights, challenges & opportunities. Future Oncol. 2016;12:1549–1552. doi: 10.2217/fon-2016-0065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Katz MS, Utengen A, Anderson PF, et al. Disease-specific hashtags for online communication about cancer care. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2:392–394. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.3960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chaudhry A, Glodé LM, Gillman M, et al. Trends in Twitter use by physicians at the American Society Of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting, 2010 and 2011. J Oncol Pract. 2012;8:173–178. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2011.000483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sugawara Y, Narimatsu H, Hozawa A, et al. Cancer patients on Twitter: A novel patient community on social media. BMC Res Notes. 2012;5:699. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-5-699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.George DR, Rovniak LS, Kraschnewski JL. Dangers and opportunities for social media in medicine. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2013;56:453–462. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0b013e318297dc38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murthy D, Eldredge M. Who tweets about cancer? An analysis of cancer-related tweets in the USA. Digit Health. 2016;2:2055207616657670. doi: 10.1177/2055207616657670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pemmaraju N, Thompson MA, Mesa RA, et al. Analysis of the use and impact of Twitter during American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meetings from 2011 to 2016: Focus on advanced metrics and user trends. J Oncol Pract. 2017;13:e623–e631. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2017.021634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koskan A, Klasko L, Davis SN, et al. Use and taxonomy of social media in cancer-related research: A systematic review. Am J Public Health. 2014;104:e20–e37. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.301980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Struck JP, Siegel F, Kramer MW, et al. Substantial utilization of Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, and Instagram in the prostate cancer community. World J Urol. 2018;36:1241–1246. doi: 10.1007/s00345-018-2254-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Park H, Reber BH, Chon MG. Tweeting as health communication: Health organizations’ use of Twitter for health promotion and public engagement. J Health Commun. 2016;21:188–198. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2015.1058435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crannell WC, Clark E, Jones C, et al. A pattern-matched Twitter analysis of US cancer-patient sentiments. J Surg Res. 2016;206:536–542. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2016.06.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leveridge MJ. The state and potential of social media in bladder cancer. World J Urol. 2016;34:57–62. doi: 10.1007/s00345-015-1725-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krippendorff K. Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology. ed 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lyles CR, López A, Pasick R, et al. “5 mins of uncomfyness is better than dealing with cancer 4 a lifetime”: An exploratory qualitative analysis of cervical and breast cancer screening dialogue on Twitter. J Cancer Educ. 2013;28:127–133. doi: 10.1007/s13187-012-0432-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoey LM, Ieropoli SC, White VM, et al. Systematic review of peer-support programs for people with cancer. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;70:315–337. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2007.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Majmundar A, Allem JP, Boley Cruz T, et al. The Why We Retweet scale. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0206076. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0206076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Markham MJ, Gentile D, Graham DL. Social media for networking, professional development, and patient engagement. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2017;37:782–787. doi: 10.1200/EDBK_180077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thompson MA, Ahlstrom J, Dizon DS, et al. Twitter 101 and beyond: Introduction to social media platforms available to practicing hematologist/oncologists. Semin Hematol. 2017;54:177–183. doi: 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2017.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wagle N, Painter C, Krevalin M, et al. The Metastatic Breast Cancer Project: A national direct-to-patient initiative to accelerate genomics research. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34 (suppl; abstr LBA1519) [Google Scholar]

- 27.Greaves F, Ramirez-Cano D, Millett C, et al. Use of sentiment analysis for capturing patient experience from free-text comments posted online. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15:e239. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]