Abstract

We use experimental survey methods in a nationally representative survey to test alternative ways of identifying (1) individuals in the population who would be better able to work if they received workplace accommodation for a health condition; (2) the rate at which these individuals receive workplace accommodation; and (3) the rate at which accommodated workers are still working four years later, compared to similar workers who were not accommodated. We find that question order in disability surveys matters. We present suggestive evidence of priming effects that lead people to understate accommodation when first asked about work-limiting health problems. We also find a sizeable fraction of workers who report they receive a workplace accommodation for a health problem but do not report work limitations per se. Our preferred estimate of the size of the accommodation-sensitive population is 22.8 percent of all working age adults. We find that 47–58 percent of accommodation-sensitive individuals lack accommodation and would benefit from some kind of employer accommodation to either sustain or commence work. Finally, among accommodation-sensitive individuals, workers who were accommodated for a health problem in 2014 were 13.2 percentage points (18.5 percent) more likely to work in 2018 than those who were not accommodated in 2014.

Keywords: disability, workplace accommodation, labor supply

I. Introduction

One in four Americans will become disabled before reaching age 67, according to the Social Security Administration (2015). Some will find ways to maintain engagement in the workforce, but many others will leave the labor force and perhaps enter the Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) program. What determines which path someone takes? It is not merely a matter of health. Disability arises from the dynamic interaction of an individual’s health and their personal, social, economic, and institutional environment (WHO, 2001). Whether or not someone has a work disability thus depends on how their health affects their ability to function effectively in a particular job setting at a given point in time. This implies that someone who has a work disability in one job setting would not necessarily have a work disability in all job settings. Evidence that one in five people who apply for SSDI benefits has significant work capacity (Maestas, Mullen and Strand, 2013) underscores the importance of understanding why people who could work, in at least some job settings, instead pursue disability benefits.

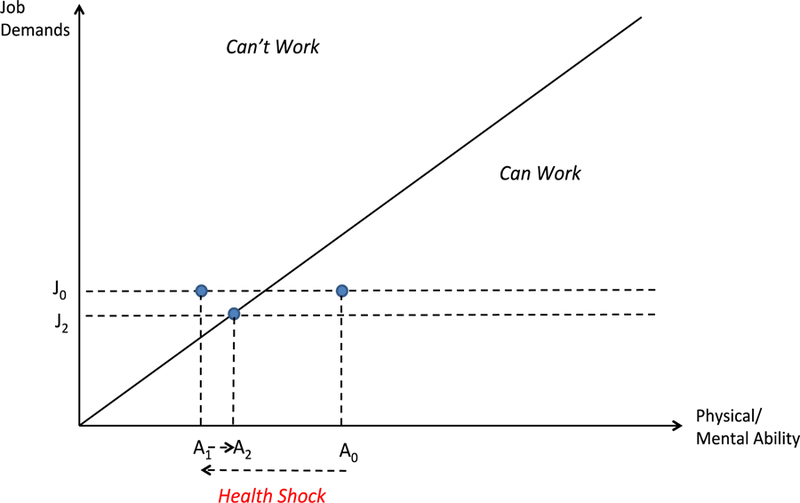

In some cases, workers who become disabled in their current job may be able to maintain employment with adjustments to their job duties or other accommodations. The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) requires that employers provide “reasonable accommodation” to employees (and applicants) with disabilities. The ADA definition of reasonable accommodation is quite broad: “any change or adjustment to a job, work environment, or the way things are usually done that would allow an individual with a disability to apply for a job, perform job functions, or enjoy equal access to benefits available to other employees” (ODEP, 2017). Figure 1 illustrates how workplace accommodation could in principle extend employment. Suppose we can represent job demands as a single index on the vertical axis and individual work ability as a single index on the horizontal axis. For all job-ability combinations lying on or below the 45-degree line, ability is sufficient to meet job demands; job-ability combinations falling above the line are infeasible and result in non-work. Suppose a worker experiences a health shock that reduces his or her ability from A0 (below the 45-degree line) to A1 (above the 45-degree line). The individual will no longer work, unless accommodations can be provided that restore some amount of ability (e.g., assistive technologies) and/or adjust job demands (e.g., changes in work tasks). The figure shows how a combination of accommodations that partially restore ability (from A1 to A2) and alter job demands (from J0 to J1) could in this instance be sufficient to shift the individual back to the 45-degree line, where their accommodated ability just meets revised job demands.

Figure 1. Conceptual Model of Workplace Accommodation Following a Health Shock.

Notes: Figure 1 provides a visual depiction of how accommodation status can affect work activity. An individual who experiences a negative health shock experiences a reduction in ability from A0 to A1, moving the individual from working to not working. However, with the help of accommodation such as assistive technology and/or a reduction in job demands, the individual moves from A1 to A2 and is able to work again.

Despite the theoretical benefits of accommodation and the fact that the ADA requires employers to provide accommodation, previous studies have produced a wide range of estimates of unmet need for workplace accommodation in the U.S.1,2 In studies using data from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS), just 20–30 percent of individuals with disabilities report receiving an accommodation from their employer at the time their health began to limit their ability to work (Burkhauser, Butler, and Kim, 1995; Daly and Bound 1996; Burkhauser et al., 1999; Yelin, Sonneborn, and Trupin, 2000; Hill, Maestas, Mullen, 2016; Bronchetti and McInerney, 2015).3 Nearly all of these studies find that workplace accommodation is only modestly effective in prolonging employment.4 On the other hand, studies focused on current workers using cross-sectional data from the National Health Interview Survey 1994–95 Disability Supplement (NHIS-D) and May 2012 Disability Supplement in the Current Population Survey (CPS) tend to find high rates of accommodation, in the range of 75–85 percent (e.g., Loprest and Maag, 2001; Zwerling et al., 2003; von Schrader et al., 2014).5 Using data from the NHIS-D, Loprest and Maag (2001) examine unmet need among nonworkers with disabilities; focusing on individuals with a “high likelihood” of returning to work (a quarter of non-workers with disabilities), they find one-third could work with accommodation. Finally, a recent study by Anand and Sevak (2017) finds 50 percent of vocational rehabilitation applicants in three states received accommodation from an employer.

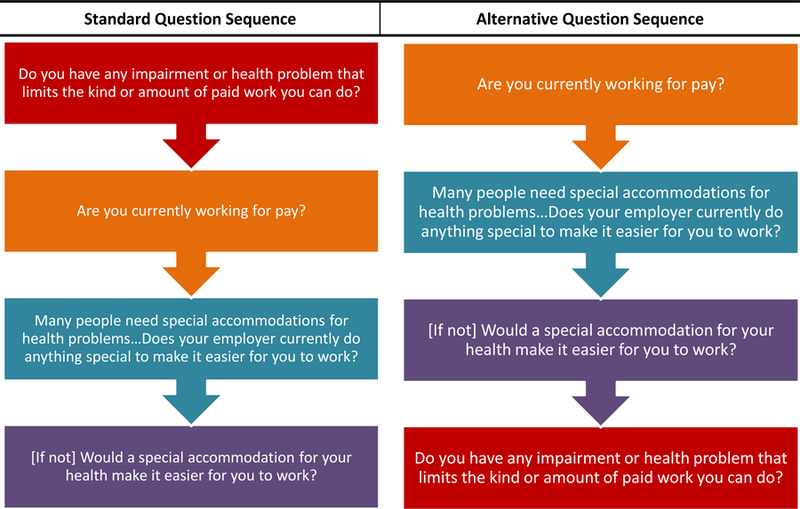

In this paper we argue that the ways in which workplace accommodation is measured in national surveys have important implications for identifying “accommodation-sensitive” individuals—that is, those individuals on the margin of working or not working depending on whether they are accommodated—and, as a result, estimating unmet need for workplace accommodation. Survey design decisions regarding question order and skip patterns affect how individuals respond to questions about employer accommodation as well as who responds to questions about employer accommodation. In order to elicit accommodation needs, one must first determine who should be in the set of those “at risk” for accommodation. Traditionally, this exercise has begun with identifying the population of individuals with disabilities, or health problems that limit the amount or kind of paid work one can do. However, asking respondents whether their health “limits” their ability to work before asking whether respondents are accommodated for a health problem may subtly encourage respondents to report accommodations only of very serious health problems. Moreover, restricting one’s attention to the set of individuals who report that their health “limits” their ability to work may exclude some accommodated workers who—precisely because of their accommodation—no longer feel that their health limits their ability to work. We argue a better approach is to instead ask individuals who do not receive an accommodation for their health whether a special accommodation for their health would make it easier for them to work, regardless of their current work status.

We use experimental survey methods in a nationally representative survey of working age adults (ages 18–70) in 2014 to test alternative ways of identifying the accommodation-sensitive population and examine how they affect estimates of unmet need. We have four key findings. Our first key finding is that question order matters, both for estimating the number of accommodated workers and for estimating the number of individuals for whom an accommodation would help. We randomly divided our sample into two groups, one receiving a survey with a “standard” question sequence where they were asked to report work-limiting health problems at the beginning of the survey, before they were asked about accommodation, and the other receiving an “alternative” question sequence that asked about work-limiting health problems at the end of the survey. Under the standard question sequence, 6.2 percent of people report a workplace accommodation for health reasons and an additional 8.6 percent say an accommodation would help, for a total of 14.8 percent of the working age population. Under the alternative question sequence, 12.1 percent report a workplace accommodation for health reasons and an additional 10.7 percent say an accommodation would help, for a total of 22.8 percent of the working age population. When we examine question order effects by work status, we find that question order matters for current employees but not for self-employed individuals or non-workers. Self-reports of work-limiting health problems are not affected by question order.

Our second key finding is that skip patterns matter for estimating the number of accommodated workers. Specifically, only 2 percent of the working age population report a workplace accommodation and that their health limits their ability to work (regardless of question sequence). By contrast, under the standard question sequence, 4.1 percent of working age individuals report a workplace accommodation and that their health does not limit their ability to work; under the alternative question sequence, this number is even greater—10.7 percent. Thus, regardless of question order, accommodated individuals who do not report a work-limiting health problem vastly outnumber accommodated individuals who do report one.

Our third key find is that the definition of the population “at risk” for workplace accommodation matters greatly for estimating unmet need. Restricting the denominator to those reporting work-limiting health problems (as necessitated by the skip pattern in the HRS) produces estimates of accommodation rates in the range of 12–15 percent in our sample of working age adults. With these estimates, one would conclude that unmet need for workplace accommodation is quite prevalent, with 85–88 percent of working age individuals potentially benefiting from a workplace accommodation they do not currently receive. Using our preferred definition of accommodation-sensitive, we find that 42–53 percent of accommodation-sensitive individuals receive a workplace accommodation. Thus, our estimates suggest that unmet need for workplace accommodation is less prevalent than suggested by previous studies using the HRS; in fact, only 47–58 percent of those who would actually benefit from a workplace accommodation do not receive one.

Finally, not only does the definition of the population “at risk” for workplace accommodation affect estimates of unmet need, but it also affects estimates of the effectiveness of workplace accommodation in prolonging labor force attachment. Specifically, among those with work-limiting health problems, we find that 70 percent of workers who received employer accommodation in 2014 were working four years later, in 2018—8.5 percentage points higher than the percent working in 2018 among similar workers who were not accommodated in 2014. By contrast, among the accommodation-sensitive, nearly 85 percent of workers who received employer accommodation in 2014 were working four years later—13.2 percentage points higher than the percent working in 2018 among similar workers who were not accommodated in 2014. Our results suggest that current estimates of the effects of workplace accommodation on working longer—primarily based on longitudinal data from the HRS—may therefore be understated.

The development of survey questions better suited to identify the accommodation-sensitive, and not only those with work-limiting health problems, has the potential to improve policymakers’ understanding of the effectiveness of ADA-regulated guidelines and policies. These findings also have implications for disability benefit policies, particularly given the increasing pressure on the financial sustainability of the SSDI program. SSDI participation has grown over the past several decades resulting from a combination of demographic changes including the aging baby boomer generation, increased female labor force participation, and programmatic features affecting the relative generosity of benefits and eligibility standards over time (Autor and Duggan, 2003; Duggan and Imberman, 2009; Liebman, 2015). The entry of every new SSDI beneficiary has fiscal costs, as it implies a reduction in tax revenue to fund the program, while it increases program outlays. These trends have led the SSDI trust fund to the brink of exhaustion at several times, most recently in 2016, and now forecasted for 2032 after reallocating funds from the Old Age and Survivors Insurance Trust Fund (Board of Trustees, 2018).

Because individuals rarely return to work once they begin receiving SSDI benefits, there has been growing policy attention surrounding potential early intervention policies to reduce the flow into the program in the first place. Workplace accommodation and rehabilitation services are often cited as two key strategies to early intervention (Autor and Duggan, 2010). The hope is that, by intervening early, policies could be more effective at rehabilitating workers before their disabilities become more severe, and at maintaining their connection with the labor force before their skills begin to depreciate (Autor et al., 2017). Because early intervention efforts would often be targeted to individuals who are still at work, several recent SSDI reform proposals emphasize that changes to employer incentives should be an important component in broader disability policy reform (e.g., Autor and Duggan, 2010; Burkhauser and Daly, 2011; Liebman and Smalligan, 2013).

Survey research will form much of the evidence base used to determine the size of the population “at risk” of entering SSDI, and in particular those individuals who could potentially be diverted from SSDI by early intervention strategies including workplace accommodation. In the latter case, overly strict definitions of disability limit the scope for evaluating whether early interventions help people sustain employment as their health problems progress from less severe to more severe. Despite the fact that accurate measurement of unmet need for accommodation is essential to guide reforms, there is growing consensus that current methods of measuring policy-relevant populations of working age individuals with disabilities in surveys are incomplete (e.g., Maag and Wittenburg, 2003; Stapleton, Burkhauser and Houtenville, 2004; Barnow, 2008; Brault, 2009; Altman, Madans and Weeks, 2017). We provide evidence of the sensitivity of estimates of unmet need to different measurement strategies, and propose a more targeted strategy to identify accommodation-sensitive individuals.

II. Design and Structure of Existing Surveys of Workplace Accommodation

There are three main nationally representative surveys used by researchers to study post-ADA workplace accommodation of adults with disabilities in the U.S. They are: the Health and Retirement Study (HRS), an ongoing longitudinal study of older Americans ages 50+ begun in 1992; the cross-sectional 1994–95 Disability Supplement in the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS); and the cross-sectional May 2012 Disability Supplement in the Current Population Survey (CPS).6,7 The design and structure of each survey subtly influences both how respondents answer questions about workplace accommodation and how researchers define the “at risk” population for workplace accommodation when constructing measures of unmet need. Table A1 summarizes the differences in question wording and conditioning sets across the surveys, discussed in greater detail below.

The HRS questionnaire is composed of several sections containing questions on topics such as demographics (Section B), physical health (C), employment (J) and disability (M). The Disability Section begins with the following: “Now I want to ask you how your health affects paid work activities. Do you have any impairment or health problem that limits the kind or amount of paid work you can do?” Respondents who answer “yes” are asked (after questions about the severity and duration of their condition(s)) if they were employed “at the time your health began to limit your ability to work” and those who were employed at onset are asked, “At the time your health started to limit your ability to work, did your employer do anything special to help you out so that you could stay at work?”8

There are at least three ways in which the HRS implicitly shapes measurement of workplace accommodation. First, the question order (asking respondents whether their health “limits” their ability to work before asking whether respondents are accommodated for a health problem) may prime respondents to report accommodations only of very serious health problems, thereby missing accommodations of less serious health problems (or those that have not yet escalated to very serious levels) that may nevertheless be effective at delaying labor force exit. Second, the skip pattern (asking only those respondents who report their health limits their work about employer accommodation) may miss instances of employer accommodations that effectively address the limitation. Finally, while a “no help needed” response option was added in 1998, no other question allows researchers to construct a measure of which respondents would benefit from employer accommodation of their health problems in order to remain at work. The implied “at risk” population for workplace accommodation is therefore individuals who report their health limits their work who were employed at the time of onset of their health condition (or who are currently working) regardless of their need for accommodation. As a result, the conditioning set includes those whose health problems are so severe no accommodation is likely to affect their ability to work and at the same time excludes those whose very accommodation enables them to work.

Like the HRS, the 1994–95 NHIS Disability Supplement (NHIS-D) prefaces employer accommodation questions with at least one question about whether health limits work. Specifically, respondents are asked “Does an ongoing health problem, impairment or disability limit your ability to work?” or, if out of the labor force or never worked, “Does an ongoing health problem, impairment or disability ENTIRELY prevent you from working?” Moreover, the NHIS-D, like the HRS, implicitly assumes that individuals who report their health does not limit or prevent their ability to work (whether or not they are currently working) would not benefit from accommodation and does not ask them any accommodation questions. On the other hand, there are at least two important differences in how the NHIS-D and HRS elicit information about accommodations. First, the NHIS-D asks those not working whether an accommodation would enable them to work9 and if so, which (specific) accommodations. Second, the NHIS-D implicitly assumes the “at risk” population for employer accommodation is those who “need” it and only asks “Do you have (feature) at work?” of those who report they need that feature.10 Additionally, in order to reduce overall respondent burden, a Phase 1 survey identified individuals with serious health problems who would receive the Phase 2 comprehensive survey; approximately 15 percent of the population met the complex criteria for inclusion in the second round.

Finally, the May 2012 CPS Disability Supplement has both advantages and disadvantages over the HRS and NHIS-D when examining workplace accommodation. One advantage is that all those in the labor force, regardless of whether or not they previously reported any health problems or limitations on their ability to work, are asked about employer accommodation. Moreover, those who did not previously report a health problem are asked about employer accommodation without any preamble asking about health problems or work limitations. At the same time, however, those individuals who did previously report any difficulty seeing, hearing, concentrating, remembering or making decisions, walking or climbing stairs, dressing or bathing, or doing errands alone such as going to the doctor’s office or going shopping, are asked at the beginning of the survey, “How has this affected your ability to complete current work duties?” if working, or “Did you ever leave or lose a job because of reasons related to this difficulty/these difficulties?” otherwise. Another disadvantage—for the purposes of understanding workplace accommodation of health problems—is that the CPS supplement does not specifically ask about health-related accommodations but instead asks, “Have you ever requested any change in your current workplace to help you do your job better? For example, changes in work policies, equipment or schedules.” Those who respond “yes” are asked what changes they requested11 and whether the requested changes were granted.12 No information is available about accommodations that did not arise specifically from a request or about whether an accommodation of a health problem would help one work or remain working. Von Schrader et al. (2014) compare accommodation requests from workers with and without a disability (as measured using the six questions in the CPS) and find that 12.7 percent of those with a disability requested an accommodation compared with 8.6 percent of those without a disability.13 Accommodations were granted at the same rate for those with and without disabilities (81.6 vs. 81.7 percent, respectively). Indeed, since the prevalence of disability is small, most accommodation requests—and accommodations—come from individuals without a disability.

One thing studies using data from these surveys all have in common is that—in the absence of questions allowing them to identify accommodation-sensitive individuals who might benefit from employer accommodation of a health problem—they tend to focus on subpopulations of individuals with very serious health problems. In other words, these survey questions are most likely effective at capturing the population of individuals far to the left on the x-axis in Figure 1, thereby over-representing those individuals with job demands that significantly exceed their physical or mental ability and who therefore are least likely to work regardless of accommodation provisions. However, the population of individuals whose work activity is most sensitive to accommodation are those who lie close to the 45-degree line in Figure 1. Thus, the accommodation-sensitive population—those on the margin of working depending on whether or not they receive accommodation—are not identifiable in existing survey data.

III. Data and Methods

We use data from the RAND American Life Panel (ALP) to provide new estimates of the size of the accommodation-sensitive population and, among them, unmet need for workplace accommodation. The RAND ALP is a nationally representative (when weighted) panel of approximately 5,700 respondents (as of May 2014) ages 18 and older who are regularly interviewed over the Internet. Individuals are recruited to participate in the ALP using both probability-based and non-probability-based sampling methods.14 Recruitment methods include in-person contact, by telephone, and by mail, providing opportunities to include individuals with a variety of impairments (e.g., an individual who is hearing-impaired may be initially contacted in person or by mail). The ALP management team ensures the panel is representative of all adults (and not just those with internet access) by providing appropriate technology to those who need it. About 3 percent of panel members are provided a laptop/tablet and/or Internet access in order to participate.15 ALP surveys meet Web Content Accessibility Guidelines and are Section 508 compliant to ensure that surveys are broadly accessible to the population of individuals with disabilities. Data sets from all surveys are publicly available (potentially after an embargo period) and can be linked to one another using a fixed respondent identification number.

In late April-May 2014, we fielded a survey in the ALP containing questions on (1) whether individuals’ health limits the kind or amount of paid work they can do, (2) whether individuals receive any special accommodation from their employer for health reasons (if working), and (3) whether a special accommodation for their health would make it easier for them to work (if not working or if working but not receiving accommodation).16 For (1) we used the same question as in the Disability Section of the HRS. The survey also includes questions about types of accommodations received (if any), whether the respondent asked for his/her current accommodation (if accommodated) or ever asked for an accommodation (if not accommodated), and, if so, the outcome of the request for accommodation. The full text of the survey is reproduced in Appendix B.

Our survey is innovative for at least three reasons. First, we investigate the role of question order and priming effects by randomizing half of the sample to receive the questions about workplace accommodations before they were asked whether their health limits their work. We did this to test the hypothesis that asking about work-limiting health problems primes respondents to focus on only the most severe health problems and neglect workplace accommodations for less severe health problems that may also affect their ability to work (and that may develop later into more severe health problems if not treated/accommodated). Figure 2 provides an overview of the question flow for those who randomly received the standard or alternative question sequences, respectively. Second, unlike other surveys, we ask all respondents about employer accommodation of health problems rather than limit these questions to those who report a work-limiting health problem. Our hypothesis was that employees who are accommodated for a health problem may not report that their health limits their ability to work because it is being accommodated. Finally, we ask those who do not report an employer accommodation (including those who are not employed)—regardless of whether they report their health limits their ability to work—if a special accommodation for their health would make it easier for them to work. We define these respondents, together with those who currently receive accommodation, as “accommodation-sensitive;” that is, a workplace accommodation could potentially enable them to work.

Figure 2. Standard and Alternative Question Sequences.

Note: Self-employed were asked “Do you do anything special when you work to accommodate a health problem?” and were not asked if an accommodation would help.

The response rate of the survey was 78 percent. We restrict our sample to respondents aged 18–70 who were randomly recruited to the panel with non-missing observations on key variables. Our final sample includes 2,484 respondents; 1,237 respondents received the “standard” question sequence with the work-limiting health impairment question as the first question in the survey, and the remaining 1,247 respondents received the “alternative” question sequence with the work-limiting health impairment question as the last question in the survey. We weighted the ALP sample to match the 2014 CPS distributions of age, race/ethnicity, education, gender, and family income.17 Table A2 shows power calculations for a range of baseline means and effect sizes. For example, we are able to detect a difference of 0.07 from a baseline mean of 0.10 approximately 80 percent of the time.

Table 1 presents summary statistics for the ALP sample, separately by question sequence (unweighted) and overall (weighted), in comparison with the (weighted) 2014 March Supplement of the Current Population Survey (CPS). Columns 1 and 2 show that demographic characteristics are balanced across the two subsamples. Columns 3 and 4 show that the weighted ALP sample matches the CPS along weighted dimensions and also nearly matches household size. However even with the weights, a significantly higher share of ALP respondents are married and were born in the United States when compared to the CPS. The ALP also yields a higher share of individuals reporting a work-limiting health problem than the CPS—15 percent in the ALP vs. 9 percent in the CPS. However, the lower rate in the CPS likely reflects differences in question wording. 18

Table 1.

Summary Statistics: ALP compared to 2014 March CPS

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALP Standard (unwt) | ALP Alternative (unwt) | ALP (wt) | CPS (wt) | |

| Weighting Variables | ||||

| Female | 0.59 | 0.61 | 0.51 | 0.51 |

| Age | 49.97 | 49.32 | 43.33 | 42.91 |

| High School or less | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.4 | 0.4 |

| Some College | 0.36 | 0.38 | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| Bachelor or More | 0.43 | 0.41 | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| White | 0.59 | 0.59 | 0.64 | 0.64 |

| Non-White | 0.41 | 0.41 | 0.36 | 0.36 |

| Income<$30,000 | 0.31 | 0.32 | 0.26 | 0.26 |

| Income $30,000-$59,999 | 0.28 | 0.29 | 0.28 | 0.28 |

| Income $60,000-$99,999 | 0.22 | 0.2 | 0.24 | 0.24 |

| Income $100,000 | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.23 | 0.23 |

|

Additional Variables | ||||

| Married | 0.58 | 0.58 | 0.64 | 0.54** |

| Household size | 2.71 | 2.81 | 3.14 | 3.07* |

| Born in the U.S. | 0.87 | 0.88 | 0.9 | 0.82** |

| Health limits work | 0.22 | 0.23 | 0.15 | 0.09** |

|

Obs (unweighted) |

1,247 |

1,237 |

2,484 |

131,009 |

| Obs (weighted) | 1 | 1 | 2 | 209,825,397 |

Notes: Table compares ALP sample from each survey sequence unweighted, andcompares the combined ALP to the 2014 CPS March supplement. Column (3) uses ALP sampling weights, and Column (4) uses CPS March supplement weights.

p < 0.10

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

Finally, to examine associations between workplace accommodations and longer-run work outcomes, we fielded a follow-up survey approximately one year later (starting in June 2015) to the N=1,412 respondents who were working at the time of the original survey, of whom, 214 were accommodated and 122 reported an accommodation would help in the original survey.19 The response rate for this survey was 83 percent overall. To examine work outcomes in 2018, we match the baseline survey to the most recent demographic records, updated quarterly by the ALP management team as part of ongoing panel maintenance.

IV. Redefining the “At Risk” Population for Workplace Accommodation

Table 2 presents the proportions of survey respondents reporting they are either (1) accommodated at their workplace, (2) not accommodated at their workplace (possibly because they are not currently working) but a special accommodation for their health would make it easier for them to work, or (3) not accommodated and a special accommodation for their health would not make it easier for them to work. The proportions are presented separately for the “standard” and “alternative” samples receiving different question sequences, and they are presented overall (Panel A) and further subdivided into whether or not the respondent also reports a work-limiting health problem (Panel B).

Table 2.

Joint Distribution of Accommodation-Sensitive and Work-Limiting Health Problems, by Question Sequence

| Standard Sequence | Alternative Sequence | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (unweighted) | sequence | (unweighte | sequence | p-value | |

| A. Overall | |||||

| Accommodated at workplace | 86 | 6.2% | 128 | 12.1% | <0.001 |

| Accommodation would help | 138 | 8.6% | 160 | 10.7% | 0.077 |

| Accommodation would not help | 1,013 | 85.1% | 959 | 77.2% | <0.001 |

| Total | 1,237 | 100.0% | 1,247 | 100.0% . | |

|

B. By Work-Limiting Health Status | |||||

| Health limits work AND | |||||

| Accommodated at workplace | 24 | 2.2% | 30 | 1.9% | 0.554 |

| Accommodation would help | 79 | 4.1% | 97 | 4.5% | 0.581 |

| Accommodation would not help | 164 | 8.4% | 155 | 9.3% | 0.428 |

| Subtotal | 267 | 14.7% | 282 | 15.7% | 0.479 |

| Health does not limit work AND | |||||

| Accommodated at workplace | 62 | 4.1% | 98 | 10.2% | <0.001 |

| Accommodation would help | 59 | 4.6% | 63 | 6.2% | 0.069 |

| Accommodation would not help | 849 | 76.7% | 804 | 67.9% | <0.001 |

| Subtotal | 970 | 85.3% | 965 | 84.3% | 0.479 |

Notes: Table shows the count, and corresponding weighted percentage, of each survey sequence sample that falls into one of six mutually exclusive groups based on their responses to questions about disability and accommodation status. Panel A compares accommodation rates between the two survey sequence groups (e.g., combining those who do and do not have a work-limiting health condition). Panel B compares accommodation rates between the survey sequence groups among those with a work-limiting health condition, and Panel C compares accommodation rates among those who do not. Percentage estimates are calculated using ALP sample weights. Column (5) reports p-values from a test of equality of the percentages in each of the two survey sequence groups. See Figure 2 for standard and alternative question sequences, respectively.

We find that question order matters for both the proportion of the population reporting receiving a workplace accommodation for their health and for the population reporting that such an accommodation would help them work. Under the standard question sequence—where respondents are first asked if they have a health problem or impairment that limits their ability to work and later asked if their employer makes any special accommodation for their health—only 6.2 percent of respondents report a workplace accommodation and an additional 8.6 percent report an accommodation would help. By contrast, under the alternative question sequence—where respondents are first asked if their employer makes any special accommodation for their health and later asked if their health limits their ability to work—nearly twice as many respondents report a workplace accommodation (12.1 percent; p<0.001). The proportion of respondents reporting an accommodation would help is also higher at 10.7 percent (p=0.077). This is consistent with the hypothesis that the work-limiting health question primes respondents to focus on more severe health problems. Note that all respondents are asked about an accommodation for their health in both question sequences, so this result reflects differences in question order only.

Panel B shows that receiving the standard or alternative question sequence: (1) does not significantly affect the proportion of respondents reporting a work-limiting health problem (14.7 percent in the standard sample vs. 15.7 percent in the alternative sample; p=0.479); and (2) only affects responses to the accommodation questions among those who report their health does not limit their ability to work. Regardless of the question sequence, approximately 2 percent of respondents report their health limits their work and they receive a workplace accommodation for their health (2.2 vs. 1.9 percent; p=0.554) and approximately 4 percent report their health limits their work and a workplace accommodation would help (4.1 vs. 4.5 percent; p=0.581). However, among those receiving the standard question sequence 4.1 percent of respondents report their health does not limit their work and yet they receive a workplace accommodation for their health; among those receiving the alternative question sequence, this proportion is significantly higher at 10.2 percent (p<0.001). An additional 4.6 percent of those receiving the standard sequence report their health does not limit their work but an accommodation would make it easier for them to work, compared to 6.2 percent of those receiving the alternative question sequence (p=0.069).

Importantly, Panel B of Table 2 shows that, regardless of question sequence, among those receiving a workplace accommodation for health reasons, respondents who report that their health does not limit their ability to work outnumber those who report that it does. This is consistent with the hypothesis that employees who are accommodated for a health problem may not report that their health limits their ability to work because it is being accommodated, and highlights the fact that a skip pattern limiting accommodation questions only to those who report a work-limiting health question will miss a sizeable fraction of respondents receiving a workplace accommodation.

Table 3 highlights our proposed definition of accommodation-sensitive by presenting, separately by question sequence, overall and by current work status, the cumulative proportions of the population: (1) reporting a workplace accommodation for health reasons, and (2), if not accommodated, reporting that an accommodation for their health would make it easier for them to work. Using the standard question sequence—with the work-limiting health question before the accommodation questions—we estimate that 14.9 percent of the population is “accommodation-sensitive”—that is, a workplace accommodation could potentially enable them to work. Coincidentally, this percentage is similar to the 14.7 percent reporting that their health limits their ability to work under the standard question sequence. Crucially, however, the two populations do not completely overlap since, as discussed above, a large fraction of the accommodation-sensitive do not report that their health limits their ability to work. Using the alternative question sequence, our estimate of the size of the accommodation-sensitive population is 22.8 percent of working-age individuals in the U.S. The latter is our preferred estimate since it does not include the priming effects from asking the work-limiting health question first.

Table 3.

Prevalence of Accommodation-Sensitive Health Problems, by Question Sequence and Work Status

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Sequence | Alternative Sequence | Diff. | P-value | |

| A. Overall (N = 2484) | ||||

| Acommodated at workplace | 6.2% | 12.1% | 5.8% | <0.001 |

| + Accommodations would help | 14.9% | 22.8% | 7.9% | <0.001 |

| Observations (unweighted) | 1237 | 1247 | ||

| Group as a percentage of total sample (weighted) | 100% | 100% | ||

|

B. Working for Someone Else (N = 1419) | ||||

| Acommodated at workplace | 8.0% | 17.2% | 9.3% | <0.001 |

| + Accommodations would help | 15.6% | 27.1% | 11.5% | <0.001 |

| Observations (unweighted) | 690 | 729 | ||

| Group as a percentage of total sample (weighted) | 65.5% | 66.0% | ||

|

C. Self-Employed (N = 193) | ||||

| Acommodated at workplace | 15.0% | 9.6% | -5.4% | 0.259 |

| Observations (unweighted) | 96 | 97 | ||

| Group as a percentage of total sample (weighted) | 6.9% | 7.8% | ||

|

D. Not Working (N = 872) | ||||

| Accommodations would help | 13.2% | 15.8% | 2.7% | 0.265 |

| Observations (unweighted) | 451 | 421 | ||

| Group as a percentage of total sample (weighted) | 27.6% | 26.8% | ||

Notes: Estimates are weighted using ALP sampling weights. The first row in Panel A shows the share of the total population reporting that are accommodated in the workplace, and the second row shows the share of the total population reporting that they are currently not accommodated, but report that accommodation would help. Panels B-D divide the overall sample into subgroups based on working status, and repeat the exercise in Panel A. See Figure 2 for standard and alternative question sequences, respectively.

To better understand what factors drive reporting of accommodation-sensitive health problems, Panels B-D of Table 3 examine the prevalence of accommodation-sensitive problems by question sequence and work status.20 Panel B shows that question order matters significantly for respondents who are currently working for an employer. Under the standard question sequence, 15.6 percent of employees are accommodation-sensitive by our definition, compared with 27.1 percent of employees under the alternative question sequence (p<0.001). Moreover, 8 percent of employees receiving the standard sequence report an accommodation, compared with 17.2 percent of employees receiving the alternative sequence (p<0.001). By contrast, Panel C-D show that question order does not significantly affect estimates of the prevalence of accommodation-sensitive health problems among the self-employed or those who are not currently working.

To learn about the specific health problems of those in the accommodation-sensitive group, we matched data from our survey to data from an earlier ALP survey that asked respondents questions from the HRS Health Section, which was fielded approximately one year prior to our accommodation survey. Pooling data from both question sequences, Table 4 presents summary statistics for three (non-mutually exclusive) groups: (1) accommodation-sensitive individuals, (2) individuals reporting their health limits their work, and (3) “healthy” individuals who are neither accommodation-sensitive nor report a work-limiting health problem. The match rate between the two surveys was similar for the accommodation-sensitive and those with work-limiting health problems (84 and 87 percent, respectively); the match rate was significantly higher for healthy respondents at 91 percent (p<0.05). Healthy respondents also tended to have a slightly longer duration between the two surveys.

Table 4.

Health Conditions One Year Prior to Survey, by Subgroup (Pooled Data)

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accommodation-Sensitive Individuals | Individuals Reporting Health Limits Work | Neither Accommodation-Sensitive Nor Reporting Health Limits Work | |

| Any limiting impairment or health problem | 0.34 | 1.00** | 0.00** |

| Currently working | 0.79 | 0.38** | 0.77 |

| High blood pressure+ | 0.3 | 0.55** | 0.24* |

| Diabetes+ | 0.11 | 0.25** | 0.07** |

| Any cancer+ | 0.04 | 0.09** | 0.07* |

| Heart condition+ | 0.07 | 0.24** | 0.03** |

| Lung Disease+ | 0.04 | 0.12** | 0.03 |

| Stroke+ | 0.02 | 0.09** | 0.00** |

| Arthritis+ | 0.26 | 0.56** | 0.15** |

| Often troubled with pain | 0.39 | 0.67** | 0.19** |

| Alzheimers+ | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Dementia+ | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.01** |

| Fair/poor memory | 0.11 | 0.20** | 0.08* |

| Emotional/Psychiatric Problems+ | 0.18 | 0.37** | 0.11** |

| Depression+ | 0.16 | 0.34** | 0.11** |

| Little energy in last week | 0.55 | 0.70** | 0.38** |

| Rarely rested in the morning | 0.16 | 0.20+ | 0.12+ |

| At least one condition reported | 0.81 | 0.96** | 0.70** |

| Total number of conditions reported |

2.41 |

4.36** |

1.58** |

| Matched to HRS questions | 0.84 | 0.87 | 0.91** |

| Months between survey start | 11.19 | 12.37 | 12.49** |

| Months between survey end | 10.92 | 12.3 | 12.47** |

|

Observations |

437 |

483 |

1,505 |

Notes: Statistics calculated with ALP sampling weights. Questions with a + were worded as follows: “(If a new interview): Has a doctor ever told you you have XX”; (If follow up interview) “Since the prior interview, has a doctor told you XX”. Prior ALP interview with HRS questions was in 2008. Column (1) includes anyone who receives accommodation or reports that accommodation would help, regardless of health status. Column (2) includes anyone who reports that they have a work-limiting health condition, regardless of accommodation status. Column (3) includes anyone who does not have a health limiting work condition and is not accommodation sensitive. Stars on column (2) indicate the results of a test equivalence of means between accommodation sensitive and health limits work group - columns (1) and (2). Stars on column (3) indicate the results of a test equivalence of means between accommodation sensitive group the remainder group - columns (1) and (3).

p < 0.10

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

Consistent with our earlier findings, only 34 percent of accommodation-sensitive individuals report a work-limiting health problem. Accommodation-sensitive individuals work at about the same rate as healthy individuals—79 vs. 77 percent, respectively—and are much more likely to work than those reporting a work-limiting health problem (38 percent; p<0.05). On average, the accommodation-sensitive group was in better health one year prior to our survey than respondents who report a work-limiting health problem and in worse health one year prior to our survey than those without any accommodation sensitivity or limitation. For example, 81 percent of accommodation-sensitive individuals report at least one condition from the list of conditions asked in the prior survey, compared with 96 percent of individuals reporting their health limits their work and 70 percent of healthy individuals. On average, accommodation-sensitive individuals reported 2.41 health conditions one year earlier, compared with 4.36 among those with work-limiting health problems and 1.58 among those with neither accommodation-sensitive nor work-limiting health problems.21

V. Implications for Unmet Need and Effectiveness of Workplace Accommodation

Next, we compare measures of unmet need for workplace accommodation, varying the question sequence and definition of the “at risk” population. Table 5 presents estimates of accommodation rates—the inverse of unmet need—unconditional and conditional on working, as well as the percent working, separately for the accommodation-sensitive (Panel A) and those reporting a work-limiting health problem (Panel B). The latter subpopulation is the implicit at-risk population implied by the skip pattern in surveys like the HRS. The former is our preferred at-risk population. As before, our preferred estimates are based on the alternative question sequence since they do not include the priming effects from asking the work-limiting health question first. For completeness, we present results for both question sequences; consistent with our earlier findings, accommodation rates are only sensitive to question order among the accommodation-sensitive.

Table 5.

Estimates of Employer Accommodation Rates for Individuals with Accommodation-Sensitive or Work-Limiting Health Problems, by Question Sequence

| Standard Question Sequence |

Alternative Question Sequence |

P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| A. Accommodation-Sensitive Sample | |||

| % Accommodated | 42.0% | 52.9% | 0.016 |

| % Working | 75.6% | 81.4% | 0.114 |

| % Accommodated | Working | 55.5% | 65.0% | 0.086 |

| N (unwt) | 224 | 288 | |

| % of Total Population | 14.9% | 22.8% | <0.001 |

|

B. Health Limits Work Sample | |||

| % Accommodated | 14.9% | 11.8% | 0.287 |

| % Working | 37.4% | 37.6% | 0.951 |

| % Accommodated | Working | 39.9% | 31.4% | 0.260 |

| N (unwt) | 267 | 282 | . |

| % of Total Population | 14.7% | 15.7% | 0.479 |

Notes: Each column represents a different sub-population, with unweighted observation counts listed in the first row of the panel. The first panel includes anyone who receives accommodation or reports that accommodation would help, regardless of health status. The second panel includes anyone who reports a health condition that limits their work, regardles of accommodation status. The second row in each panel reflects these counts as weighted share of the total survey sequence sample (total observation counts for each sequence sample are listed in the panel headers). Row (3) reflects the percentage of individuals with the disability/accommodation status who are working. Row (4) reflects the percentage of individuals with the disability/accommodation status who are accommodated (unconditional on working), and row (5) esimtates the percentage of individuals with the disability/accommodation status who are accommodated (conditional on working). Estimates are weighted using ALP sample weights. See Figure 2 for standard and alternative question sequences, respectively.

Table 5 demonstrates the importance of choosing an appropriate definition of the at-risk population when measuring unmet need for workplace accommodation. Under the alternative question sequence, 52.9 percent of the accommodation-sensitive report an accommodation at work, compared with only 11.8 percent of those reporting their health limits their work (p<0.001). Even though one must be working in order to be accommodated at work, we believe the unconditional accommodation rate more accurately captures the concept of unmet need among those whose ability to work, both on the extensive and intensive margin, could be improved by receiving employer accommodation. Consistent with our earlier findings, the accommodation-sensitive are more likely to work than those with work-limiting health problems, but even conditional on working accommodation rates are higher among the accommodation-sensitive than among those with work-limiting health problems (65 vs. 31.4 percent, respectively, under the alternative question sequence; p<0.001). Nevertheless, a substantial share of accommodation-sensitive individuals still face unmet need—47.1 percent, under the alternative question sequence.

Table 6 presents another measure of unmet need, based on whether respondents ever asked for and received any accommodation from their employer in response to their request. Panel A shows that, among the accommodation-sensitive, three-quarters of respondents say they never asked their employer for a special accommodation for their health. Nevertheless, of those who did not ask for accommodation, 43.3 percent report receiving an accommodation, perhaps because they had a visible health problem their employer could proactively address. However, those who asked for accommodation were only 10.9 percentage points more likely to be accommodated than those who did not ask at 54.2 percent (p<0.05), still reflecting a substantial amount of unmet need.

Table 6.

Accommodation and Work Status by Status of Request for Accommodation, Among Accommodation-Sensitive Individuals (Pooled Data)

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count | Pct of Subgroup (wt) | % Accommodated | % Working | |

| A. Total Accommodation- Sensitive Group | ||||

| Did not ask for accommodation | 346 | 74.7% | 43.3% | 78.5% |

| Asked for accommodation | 141 | 25.3% | 54.2% | 76.9% |

|

B. Conditional on Asking For Accommodation: | ||||

| Employer provided accommodation requested | 89 | 60.6% | 80.4% | 87.0% |

| Employer provided a different accommodation | 13 | 13.0% | 40.4% | 86.2% |

| Employer did not provide any accommodation | 39 | 25.9% | 0.0% | 48.7% |

Notes: Table 6 shows the share of accommodation-sensitive individuals (regardless of health status) who did and did not ask for accommodation, and the outcomes of those accommodation requests. Column (1) shows the unweighted total number of observations in each group. Columns (2) shows the percentage of the entire accommodation sensitive group represented by the row. Columns (3) and (4) show the share of individuals in the group (row) who are accommodated and working, respectively. Percentages calculated with ALP sampling weights.

Overall, accommodation-sensitive individuals who ever asked for accommodation were no more likely to be working at the time of the survey than those who never asked for accommodation, despite being more likely to report receiving accommodation. At the same time, Panel B reveals that, among those who asked for accommodation, receiving any accommodation—regardless of whether it was the specific accommodation requested or a different accommodation—is significantly related to work outcomes. More than 86 percent of individuals who asked for and received some type of accommodation were working at the time of the survey. By contrast, only 48.7 percent of those who asked but did not receive any accommodation were working at the time of the survey (p<0.01).

Finally, in Table 7 we examine the relationship between receiving any (specific type of) accommodation—regardless of whether it was requested—and the probability of working one and four years later, respectively. We pool data from the standard and alternative samples due to small sample sizes. Columns (1)-(4) report statistics for the subsample of accommodation-sensitive individuals who were working in 2014—that is, those who either are accommodated or report an accommodation would help them work—and columns (5)-(8) report analogous statistics for the subsample of those who report their health limits their ability to work (regardless of whether they are accommodated or report an accommodation would help). To obtain work status in 2015, we match to the 2015 follow-up survey; for 2018, we match to the most recent quarterly-updated demographic records.22 Columns 1 and 5 give the number of observations for each row, and columns 2 and 6 give the (weighted) percentage of respondents for each row. Columns 3 and 7 present the percentage of respondents working in 2015, and columns 4 and 9 present the percentage working in 2018.

Table 7:

Future Work Status by Accommodation Type (Pooled Data)

| (1) |

(2) |

(3) |

(4) |

(5) |

(6) |

(7) |

(8) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conditional on Accommodation Sensitive |

Conditional on Health Limits Work |

|||||||

| Count | Pct of Total (wgt) | % Working in 2015 | % Working in 2018 | Count | Pct of Total (wgt) | % Working in 2015 | % Working in 2018 | |

| A. Accommodation- Sensitive Individuals Working in 2014 | ||||||||

| No accommodation | 122 | 38.6% | 92.1% | 71.5% | 109 | 64.5% | 87.7% | 61.5% |

| Any accommodation | 214 | 61.4% | 83.7% | 84.7% | 54 | 35.5% | 94.8% | 70.1% |

|

B. Conditional on Any Accommodation & Working in 2014 | ||||||||

| My employer helped me learn / I learned new job skills. | 72 | 50.6% | 78.8% | 91.2% | 11 | 26.3% | 100.0% | 90.7% |

| My employer allows me to / I change change the time I come to or leave work. | 92 | 47.4% | 70.7% | 85.0% | 17 | 41.7% | 90.2% | 59.6% |

| My employer gets / I get someone to help me. | 83 | 36.1% | 83.7% | 81.3% | 20 | 48.5% | 100.0% | 62.9% |

| My employer shortens / I shorten my work day. | 40 | 31.9% | 84.1% | 69.1% | 18 | 41.2% | 93.4% | 54.6% |

| My employer allows me / I take more breaks and rest periods. | 70 | 24.6% | 87.0% | 72.5% | 20 | 36.5% | 90.8% | 46.7% |

| My employer gets me / I get special equipment for the job. | 47 | 16.3% | 79.6% | 89.8% | 11 | 13.6% | 91.8% | 57.6% |

| My employer has / I changed the job to something I can do. | 23 | 9.2% | 95.2% | 74.3% | 10 | 16.5% | 86.2% | 73.9% |

| My employer arranges / I arrange for special transportation. | 9 | 4.8% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 3 | 13.4% | 100.0% | 100.0% |

| My employer assists me in receiving / I receive rehabilitative services from an external provider. | 11 | 2.6% | 90.5% | 100.0% | 4 | 4.5% | 80.3% | 100.0% |

| My employer does / I do other things to make it easier to work. [if yes, specify] | 40 | 16.2% | 56.1% | 72.3% | 12 | 21.8% | 100.0% | 29.8% |

Notes: Column 1 shows the number of respondents reporting use of the type of accommodation listed in the row. Column (2) shows the values in column (1) as a percent of the total number of respondents who receive accommodation from an employer or self-accommodate (when self-employed). Column (3) shows the number of people who responded to the follow-up survey, conditional on receiving the accommodation in the row. Column (4) shows the response rate to the follow-up survey conditional on receiving accommodation in a given row (i.e., column (3) divided by column (1)).Column (5) shows the (weighted) percentage working one year later, conditional on receiving the type of accommodation listed in the row during the initial survey. Column (6) shows the number of people who responded to the 2018 ALP demoraphic module, conditional on responding to the baseline survey, working and being accommodated at baseline. Column (7) shows the response rates to the 2018 ALP demographic module, conditional on working and being accommodated at baseline. Column (8) shows the share of individuals who were working in 2018, conditional on working and being accommodated at baseline. Percentages calculated with ALP sampling weights.

Panel A reproduces our finding that, among accommodation-sensitive workers, nearly 40 percent did not receive a workplace accommodation for their health at the time of the original survey in 2014. Of those who did not receive accommodation, 92 percent were working one year later, falling to 72 percent four years later. By contrast, 84 percent of accommodated workers were working one year later and this number remained relatively flat at 85 percent four years later. Thus, accommodated individuals are 13.2 percentage points (18.5 percent) more likely to be working than non-accommodated individuals four years later. While not causal, this suggests accommodation may be effective at retaining workers in the medium, if not short, run. If one were to focus on individuals who report their health limits their work—a common “at risk” population for studies using the HRS and NHIS-D—then these findings are somewhat diluted. Among those who report their health limits their work, only 35.5 percent are accommodated and only 70 percent of those accommodated work four years later, compared to 62 percent of those who were not accommodated at baseline—a difference of only 8.5 percentage points, or 36 percent smaller than the same difference in the accommodation-sensitive population.

Finally, Panel B shows the distribution of different (non-mutually exclusive) types of accommodations received, conditional on accommodation (column 2) or conditional on accommodation and reporting health limits work (column 5). Differences between the two distributions tell us which types of accommodations are more or less associated with reports of work-liming health. For example, learning new skills is the most common accommodation reported in our data, with more than half of accommodated workers reporting it. However, among those who also report their health limits their ability to work, only 26 percent report learning new skills. Therefore, those who learn new skills to accommodate a health problem are much less likely to report that their health limits their work. Perhaps not surprisingly, learning new skills appears to be one of the most effective types of accommodation, with 91 percent of those receiving it working four years later (regardless of whether they report their health limits their work). The second most common accommodation—changing one’s work times—is less likely to be reported differentially overall (47 percent) vs. among those who report their health limits their work (42 percent). At the same time, three-year work rates are much higher for all those reporting changes in work times (85 percent) compared with the subsample who also report their health limits their work (60 percent).

VI. Discussion and Conclusion

In this paper we argue that the ways in which workplace accommodation is measured in national surveys have important implications for identifying “accommodation-sensitive” individuals—that is, those individuals on the margin of working or not working depending on whether they are accommodated—and, as a result, estimating unmet need for workplace accommodation. We use experimental survey methods in a nationally representative survey of working age individuals adults (ages 18–70) in 2014 to test alternative ways of identifying the accommodation-sensitive population and examine how they affect estimates of unmet need. Using our preferred estimate, we find that 22.3 percent of people aged 18–70 in the U.S. are accommodation-sensitive. One limitation of our study is that we rely on individuals to accurately assess whether or not a workplace accommodation for their health would in fact help them remain employed or regain employment. A promising direction for future research would be to evaluate whether or not this is truly the case.

Whereas prior estimates largely based on data from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS) indicated that only 20–30 percent of people with work-limiting health problems received accommodations from their employers, we present new evidence that the rate of workplace accommodation for a health problem among those who would benefit is closer to 56–65 percent among those who are employed and 42–53 percent of all accommodation-sensitive individuals.23 Our estimate accounts for three factors that bias previous estimates based on studies like the HRS and NHIS-D downward. First, our estimate is purged of question order effects that encourage people to understate the degree to which they are receiving accommodations from their employers. Second, we include cases in which people are fully accommodated, such that they no longer experience (or at least report) work limitations. Finally, we include non-workers and workers without accommodation who say an accommodation would help and we specifically exclude workers who say that workplace accommodation would not help (but who report their health limits their ability to work).

An implication of a higher accommodation rate is that estimates of the unmet need for accommodation are lower than previously thought. Nevertheless, we find that 47–58 percent of accommodation-sensitive individuals could benefit from some kind of accommodation in order to become or remain employed. One hypothesis for the prevalence of unmet need is that people who would benefit do not ask their employers for accommodations (Hill, Maestas, and Mullen, 2016). Consistent with this explanation, we find that only one-quarter of accommodation-sensitive individuals ever asked for accommodation. However, we also find that the majority of accommodations are not the result of an explicit request; of the 75 percent of accommodation-sensitive individuals who did not ask for an accommodation, 43 percent were accommodated anyway, suggesting employers may be more proactive in accommodating individuals for whom they see a need than previously thought.

Our findings suggest that the effectiveness of accommodation—that is, does it prolong employment and defer SSDI application—needs to be re-evaluated. As described earlier, the prior literature has concluded that accommodation prolongs employment by at most two-three years and has mixed effects on subsequent SSDI application. But these analyses miss a group of people whose disabilities are being fully accommodated such that they no longer experience work limitations. Our findings suggest that conclusions based on comparisons of subsequent employment rates between accommodated and non-accommodated workers depends critically on which workers are defined as “at risk” or eligible for workplace accommodation for a health problem. Focusing explicitly on accommodation-sensitive individuals, we find workers who were accommodated for a health problem in 2014 were 13.2 percentage points (18.5 percent) more likely to work in 2018 than those who were not accommodated in 2014. This estimate is 50 percent larger than the same estimate using the same method but conditional on positive reports of work-limiting health problems. Likewise, conditional on asking for accommodation, those who received accommodation (either fully or partially) were nearly twice as likely to be working at the time of the 2014 survey than those whose request for accommodation was not granted.

Unfortunately, we cannot infer a causal relationship between accommodation and work outcomes since it likely reflects unobservable differences in severity or baseline propensity to work between employees who (1) ask vs. do not ask for, and, more generally, (2) receive vs. do not receive workplace accommodation. Understanding the process by which accommodation-sensitive individuals are accommodated or not is therefore critical to understanding the effectiveness of workplace accommodation. However, identifying the appropriate “at risk” population is an important first step.

Our findings suggest accommodation efforts and ADA policies should first focus on accommodation-sensitive individuals who have unmet needs, rather than those for whom an accommodation would not help to alleviate their work limitation. Currently accommodated workers indicate that training for new skills, flexible schedules, and special assistance are the most popular forms of current accommodations. Our findings suggest that policies like employer subsidies or tax incentives to provide retraining in particular may prove fruitful. More flexible workplaces could provide accommodation to those with disabilities, for example, by enabling them to work from home or allowing employees to adjust their hours around doctor’s appointments. Additionally, given that few employees seek accommodation on their own, policymakers could consider policies where other parties, such as health providers, could directly initiate requests for accommodation.

In order to solve SSDI’s financial shortfall, several SSDI reform proposals incorporate ways to incentivize employers to hire and retain workers with disabilities. The potential success of such strategies is based on a belief that accommodation is an effective means of prolonging employment. Although the literature to date has not lent much support for that belief, this paper suggests the question is worth a second look. While the findings in this paper do not fully answer the question of the extent to which accommodation improves employment outcomes, they do provide a new framework for measuring accommodation rates and identifying the policy-relevant population of accommodation-sensitive individuals.

Acknowledgments

We thank participants of the 2015 DRC annual conference in Washington, D.C., for helpful comments and suggestions. This research was supported by the U.S. Social Security Administration through grant #1 DRC12000002–03 to the National Bureau of Economic Research as part of the SSA Disability Research Consortium and by grant R01AG056238 from the National Institute on Aging. The findings and conclusions expressed are solely those of the author(s) and do not represent the views of SSA, NIA, any agency of the Federal Government, or the NBER.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Comparison of Workplace Accommodation Questions Across Surveys

| HRS, 1992-Present | 1994–95 NHIS-D | May 2012 CPS Disability Supplement | May 2015 ALP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Work limitation | Do you have any impairment or health problem that limits the kind or amount of paid work you can do? | Are you limited in the kind or amount of work you can do because of an ongoing health problem, impairment, or disability? | [If reported difficulty in earlier survey] Previously, you mentioned that you had difficulty (hearing/seeing/concentrating, remembering or making decisions/walking or climbing stairs/dressing or bathing/doing errands alone such as going to the doctor’s office or going shopping). How has this affected your ability to complete current work duties? | [Randomized first or last] Do you have any impairment or health problem that limits the kind or amount of paid work you can do? |

| Work status | Were you employed at the time your health began to limit your ability to work? | Have you EVER worked at a job or business? Do you NOW work at at job or business? | Have you EVER worked for pay at a job or business? | Are you currently working for pay? |

| Accommodation questions | ||||

| Conditional on... | Health limits work | Health limits work | n/a | n/a |

| If not working | n/a | If enough accommodation were made in transportation and at the workplace, would you be able to work? | n/a | Would a special accommodation for your health make it easier for you to work? |

| If working | At the time your health started to limit your ability to work, did your employer do anything special to help you out so you could stay at work? | In order to work, would you NEED any of these special features at your worksite, regardless or whether or not you actually have them--- Because of an ongoing health problem, impairment, or disability, do you NEED any (other) special equipment, assistance or work arrangements in order to do your job? | Have you ever requested any change in your current workplace to help you do your job better? For example, changes in work policies, equipment, or schedules. | Many people need special accommodations for health problems to make it easier for them to work. This could include things like getting special equipment, getting someone to help them, varying their work hours, taking more breaks and rest periods, or learning new job skills. Does your employer currently do anything special to make it easier for you to work? |

| ...Conditional on… | n/a | Need accommodation | Requested any change | n/a |

| ...If accommodated | What types of accommodations? [check all that apply] | Do you have ___ at work? | What changes did you request? Were they granted? | What types of accommodations? [check all that apply] |

| ...If not accommodated | n/a | n/a | What changes did you request? Were they granted? | Would a special accommodation for your health make it easier for you to work? |

Table A2.

Power Calculations

| Difference from Baseline Mean | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.1 | ||

| Baseline Mean | 0.02 | 0.13 | 0.33 | 0.56 | 0.76 | 0.89 | 0.95 | 0.98 | 0.99 | 1 | 1 |

| 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.19 | 0.35 | 0.53 | 0.7 | 0.83 | 0.91 | 0.96 | 0.98 | 0.99 | |

| 0.1 | 0.07 | 0.13 | 0.23 | 0.36 | 0.51 | 0.65 | 0.77 | 0.86 | 0.92 | 0.96 | |

| 0.25 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.14 | 0.22 | 0.31 | 0.42 | 0.53 | 0.64 | 0.74 | 0.82 | |

| 0.5 | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.12 | 0.18 | 0.26 | 0.35 | 0.45 | 0.56 | 0.66 | 0.75 | |

Notes: Each cell in the table displays the statistical power when detecting an effect of the size shown in the column from the baseline mean represented in the row. For example, the cell in the upper lefthand corner indicates that given the effective sample size, the probability of detecting a 0.01 difference from a baseline mean of 0.02 is 13%. Effective sample size (with weights) is 460 in the alternate sample and 546 in the standard sample. Power is symmetric for proportional means: i.e., the power for a mean of 0.75 is the same as the power for the mean of 0.25.

Table A3:

Demographic Characteristics

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accommodation-Sensitive Individuals | Individuals Reporting Health Limits Work | Neither Accommodation-Sensitive Nor Reporting Health Limits Work | |

| Pct female | 0.53 | 0.56 | 0.51 |

| Age | 41.0 | 52.38** | 42.52* |

| Pct married | 0.58 | 0.58 | 0.66** |

| High School or less | 0.47 | 0.53 | 0.36** |

| Some College | 0.32 | 0.26 | 0.30 |

| Bachelor or More | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.34** |

| White | 0.52 | 0.68** | 0.66** |

| Non-White | 0.48 | 0.32** | 0.34** |

| Income<$30,000 | 0.34 | 0.40 | 0.22** |

| Income $30,000-$59,999 | 0.30 | 0.28 | 0.28 |

| Income $60,000-$99,999 | 0.25 | 0.17+ | 0.24 |

| Income $100,000 | 0.11 | 0.15 | 0.27** |

| Household size | 3.24 | 2.65** | 3.20 |

| Born in US | 0.84 | 0.89* | 0.91** |

| Northeast | 0.25 | 0.18 | 0.20* |

| Midwest | 0.15 | 0.16 | 0.19* |

| South | 0.27 | 0.33 | 0.31+ |

| West |

0.34 |

0.33 |

0.30 |

| Observations (unweighted) | 512 | 549 | 1653 |

Notes: Table compares the accomodation sensitive group (regardless of work limitations), the group with work limitations (regardless of acommodation status), and all other respondents using ALP weights. P-values between the accommodation sensitive and health limits work group shown in column (2); p-values between the accommodation sensitive group and other respondents shown in column (3).

p < 0.10

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

Appendix B. Survey Questionnaire

IF randomizer = 1 THEN

|

| Q1 Are you currently working for pay

| Are you currently working for pay?

ELSE

|

| Q11 Any limiting impairment or health problem

| Do you have any impairment or health problem that limits the kind or amount of paid work you can do?

|

| Q1 Are you currently working for pay

| Are you currently working for pay?

| ENDIF

IF Q1 = Yes THEN

|

| Q2 Employee or self-employed

| On your current (main) job, do you work for someone else, or are you self-employed?

| 1 Work for someone else

| 2 Self-employed

|

| IF Q2 != Self-employed THEN

| |

| | Q6 Does employer currently provide accomodation

| | Many people need special accommodations for health problems to make it easier for them to work.

| | This could include things like getting special equipment, getting someone to help them, varying

| | their work hours, taking more breaks and rest periods, or learning new job skills. Does your

| | employer currently do anything special to make it easier for you to work?

| |

| | IF Q6 = Yes THEN

| | |

| | | [Questions Q7 to Q7_other are displayed as a table]

| | |

| | | Q7 Employer accommodations

| | | Check all that apply.

| | | 1 My employer gets someone to help me.

| | | 2 My employer shortens my work day.

| | | 3 My employer allows me to change the time I come to or leave work.

| | | 4 My employer allows me more breaks and rest periods.

| | | 5 My employer arranges for special transportation.

| | | 6 My employer has changed the job to something I can do.

| | | 7 My employer helped me learn new job skills.

| | | 8 My employer gets me special equipment for the job.

| | | 9 My employer assists me in receiving rehabilitative services from an external provider.

| | | 10 My employer does other things to help me out.$Answer2$

| | |

| | | Q7_other Employer does other things to help OTHER

| | |

| | | String

| | |

| | | Q4 Asked employer for special accommodation

| | | [Did you ask your employer for accommodation?/Have you ever asked [your/an] employer to make a

| | | special accommodation for your health?]

| | |

| | | IF Q4 = Yes THEN

| | | |

| | | | Q5 Outcome of request for special accommodation

| | | | What was the outcome of your request?

| | | | 1 My employer provided the accommodation I requested.

| | | | 2 My employer provided a different accommodation.

| | | | 3 My employer did not provide any accommodation.

| | | |

| | | ENDIF

| | |

| | ELSEIF Q6 = No THEN

| | |

| | | Q3 Special accommodation would make work easier

| | | Would a special accommodation for your health make it easier for you to work?

| | |

| | | IF Q3 = Yes THEN

| | | |

| | | | Q4 Asked employer for special accommodation

| | | | [Did you ask your employer for accommodation?/Have you ever asked [your/an] employer to make

| | | | a special accommodation for your health?]

| | | |

| | | | IF Q4 = Yes THEN

| | | | |

| | | | | Q5 Outcome of request for special accommodation

| | | | | What was the outcome of your request?

| | | | | 1 My employer provided the accommodation I requested.

| | | | | 2 My employer provided a different accommodation.

| | | | | 3 My employer did not provide any accommodation.

| | | | |

| | | | ENDIF

| | | |

| | | ENDIF

| | |

| | ENDIF

| |

| ELSEIF Q2 = Self-employed THEN

| |

| | Q8 Self-employed any special accomodation

| | Do you do anything special when you work to accommodate a health problem?

| |

| | IF Q8 = Yes THEN

| | |

| | | [Questions Q9 to Q9_other are displayed as a table]

| | |

| | | Q9 Employer accommodations

| | | Check all that apply.

| | | 1 I get someone to help me.

| | | 2 I shorten my work day.

| | | 3 I change the times I work.

| | | 4 I take more breaks and rest periods.

| | | 5 I arrange for special transportation.

| | | 6 I have changed my job to something I can do.

| | | 7 I learned new job skills.

| | | 8 I use special equipment for the job.

| | | 9 I receive rehabilitative services from a provider.

| | | 10 I do other things to make it easier to work.$Answer2$

| | |

| | | Q9_other Self-employed does other things OTHER

| | | String

| | |

| | | Q10 Reason became self-employed

| | | You indicated that you do something special when you work to accommodate a health problem. Is

| | | that the reason you chose to become self-employed?

| | | 1 Yes

| | | 2 Partly

| | | 3 No

| | |

| | ENDIF

| |

| ENDIF

|

ELSEIF Q1 = No THEN

|

| Q3 Special accommodation would make work easier

| Would a special accommodation for your health make it easier for you to work?

|

| IF Q3 = Yes THEN

| |

| | Q4 Asked employer for special accommodation

| | [Did you ask your employer for accommodation?/Have you ever asked [your/an] employer to make a

| | special accommodation for your health?]

| |

| | IF Q4 = Yes THEN

| | |

| | | Q5 Outcome of request for special accommodation

| | | What was the outcome of your request?

| | | 1 My employer provided the accommodation I requested.

| | | 2 My employer provided a different accommodation.

| | | 3 My employer did not provide any accommodation.

| | |

| | ENDIF

| |

| ENDIF

| ENDIF

IF randomizer = 1 THEN

|