Abstract

West Nile virus (WNV) lineage 2 is associated with neurologic disease in horses and humans in South Africa. Surveillance in wildlife and nonequine domestic species during 2010–2018 identified WNV in 11 (1.8%) of 608 animals with severe neurologic and fatal infections, highlighting susceptible hosts and risk for WNV epizootics in Africa.

Keywords: West Nile virus, viruses, WNV lineage 1, WNV lineage 2, South Africa, wildlife, nonequine domestic animals, zoonoses, vector-borne infections, arboviruses, zoonoses

West Nile virus (WNV) is associated with febrile disease, meningoencephalitis, and death in humans and horses (1,2). WNV infections are recognized on most continents but remain underreported in Africa. An 8-year study in horses with fever, neurologic signs, or both in South Africa described WNV lineage 2 as the cause of annual outbreaks; 93.7% of WNV-positive horses displayed neurologic signs, resulting in a 34.2% fatality rate (3). In the United States, clinical WNV disease has been reported in several nonequine species: birds, crocodiles, bats, wolves, cats, dogs, cattle, and sheep (4). The disease susceptibility of wildlife species in Africa and the role they play in amplifying the virus is unknown. We conducted surveillance for neurologic disease and death in animals other than horses in South Africa during 2010–2018 to determine potential WNV reservoir species, identify susceptible hosts, and highlight potential areas for targeted surveillance.

The Study

A total of 608 specimens comprising central nervous system tissue, visceral organs, and whole blood from wildlife; nonequine domestic animals; and birds with neurologic, febrile, or respiratory signs or sudden unexpected death were submitted to the Centre for Viral Zoonoses, University of Pretoria (Pretoria, South Africa), during February 2010–June 2018. We extracted RNA from the samples using the QIAamp viral RNA (QIAGEN, https://www.qiagen.com) (blood) or RNeasy (QIAGEN) (tissue) mini-kits under Biosafety Level 3 conditions. All specimens were subjected to 1-step nested real-time reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR) targeting WNV (LightCycler FastStart DNA Master HybProbe; Roche Applied Science, https://www.lifescience.roche.com) (5).

Eleven (1.8% [95% CI 0.8%–2.9%]) of the 608 animals tested positive for WNV. A total of 519 (84.5%) specimens were from animals that died, of which 78 were found dead and classified as sudden unexpected death. WNV was detected in 6 (1.7% [95% CI 0.3%–3.0%]) of 361 wildlife and 5 (1.5% [95% CI 0%–3.3%]) of 196 nonequine domestic animals but in 0 of 51 birds (Table 1). We detected WNV RNA in 2 (2%) of 93 domestic cattle (Bos taurus), 1 (2%) of 54 African buffalo (Syncerus caffer), 1 (5%) of 22 domestic dogs (Canis lupus familiaris), 1 (33%) of 3 exotic fallow deer (Dama dama), 1 (9%) of 6 giraffes (Giraffa camelopardalis), 1 (9%) of 11 domestic goats (Capra aegagrus hircus), 1 (11%) of 9 lions (Panthera leo), 1 (2%) of 45 domestic sheep (Ovis aries), and 2 (7%) of 28 roan antelope (Hippotragus equinus) (Table 1). Only 2 of 11 infected animals survived: 1 domestic bovid and the exotic fallow deer.

Table 1. West Nile virus detected in specimens from animals with neurologic disease or unexplained death using real-time reverse transcription PCR, South Africa, 2010–2018*.

| Animal | Identifier | Origin of sample, province | No. positive/animal type (%) [95% CI] | Specimen testing positive | Co-infection (tissue source) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Domestic bovid (Bos taurus) |

ZRU181/12/1† | Gauteng | 2/93 (2.2) [0.0–5.1] |

Brain blood |

MIDV (spleen) |

| ZRU176/14/2 |

Free State |

||||

| African buffalo (Syncerus caffer) |

ZRU161/18† |

Limpopo |

1/54 (1.9) [0.0–5.5] |

Lung |

MIDV (lung, blood) |

| Domestic dog (Canis lupus familiaris) |

ZRU358/17† |

Gauteng |

1/22 (4.6) [0.0–13.3] |

Brain, lung |

AHSV (brain, lung, spleen) |

| Fallow deer (Dama dama) |

ZRU174/14 |

Gauteng |

1/3 (33.3) [0.0–86.7] |

Blood |

|

| Giraffe (Giraffa giraffa) |

ZRU87/18† |

North West |

1/6 (9.1) [0.0–46.5] |

Lung |

SHUV (blood) |

| Domestic goat (Capra aegagrus hircus) |

ZRU192/14 |

Gauteng |

1/11 (9.1) [0.0–26.1] |

Brain, spleen |

|

| Lion (Panthera leo) |

ZRU297/17† |

Mpumalanga |

1/9 (11.1) [0.0–31.2] |

Brain |

|

| Domestic sheep (Ovis aries) |

ZRU159/18† |

Gauteng |

1/45 (2.2) [0.0–6.6] |

Spleen |

|

| Roan antelope (Hippotragus equinus) |

ZRU061/16/2† | Free State | 2/28 (7.1) [0.0–16.7] |

Lung |

|

| ZRU165/16 |

Limpopo |

Lung |

|||

| Wildlife |

|

|

6/361 (1.6) [0.3–2.9] |

|

|

| Domestic animals |

|

|

5/196 (2.6) [0.3–4.8] |

|

|

| Birds |

|

|

0/51 |

|

|

| Total | 11/608 (1.8) [0.5–2.9] |

*Identifiers are ZRU laboratory number/year/sample number. AHSV, African horse sickness virus; MIDV, Middleburg virus; SHUV, Shuni virus; ZRU, Zoonosis Research Unit (now CVZ, Centre for Viral Zoonoses). †Sequence data available.

Virus isolation identified African horse sickness virus as a co-infection in the WNV-positive dog (ZRU358_17), confirmed by the Equine Research Centre (6) (Table 1). WNV neutralizing antibodies have previously been reported among dogs in South Africa, although no active infection has been described (7). The domestic bovid (ZRU181_12_1) and buffalo (ZRU161_18) had Middleburg virus co-infections, and the giraffe had Shuni virus co-infection confirmed by differential testing (8–10) at the Centre for Viral Zoonoses (Table 1). In these animals, clinical signs and death could not be attributed to any of the detected viruses alone.

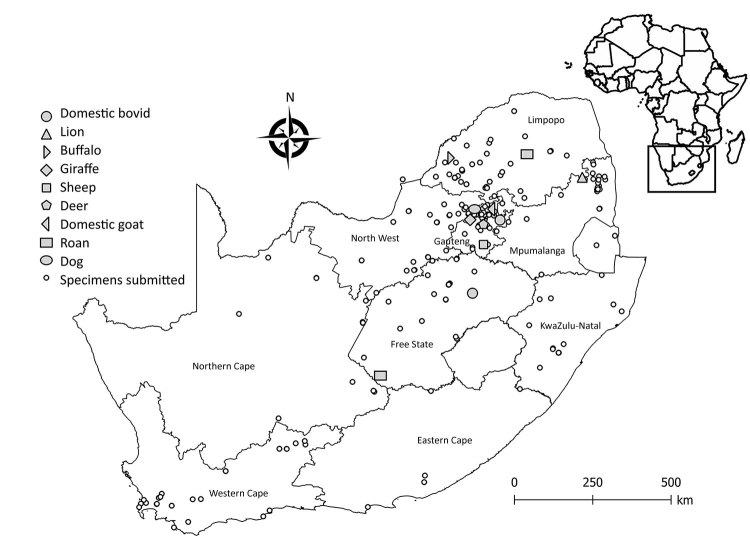

Positive WNV infections were detected in the Free State (2/45, 4%), Gauteng (5/192, 3%), North West (1/47, 2%), Limpopo (2/132, 2%), and Mpumalanga provinces (1/82, 1%) (Figure 1). Most positive animals were reported during March–June, corresponding to the arbovirus season in South Africa (Appendix).

Figure 1.

Areas where West Nile virus infections were detected in wildlife and nonequine domestic animals, South Africa, 2010–2018. Insert indicates location of South Africa in Africa.

We detected WNV in lung (5/11, 45%), brain (4/11, 36%), and spleen (2/11, 18%) tissue and in blood (2/11, 18%) (Table 1). Clinical signs noted in WNV-positive animals included neurologic (4/8, 50%) and respiratory (3/8, 38%); 2 animals with neurologic signs also had pyrexia (Table 2). The lion (ZRU297_17) and giraffe (ZRU87_18) were found dead (2/11, 18%); thus, no clinical signs were reported. The WNV-positive sheep (ZRU159_18), an indigenous Dorper, was a stillborn fetus with cerebral edema. In sheep, WNV is reported to cause neurologic symptoms (11) but has not been associated with stillbirths. The roan antelope (ZRU61_16_2), the domestic bovid (ZRU181_12_1), and the sheep fetus represented WNV-positive specimens among a cluster of animals with similar signs potentially representing larger outbreaks in these areas. Despite extensive screening for arboviruses, the causative link between the clinical presentation of the various species and the evidence of WNV infection must be regarded with caution because we could not exclude all other possible infectious and noninfectious etiologies.

Table 2. Clinical signs and outcomes in wildlife and nonequine domestic animals tested for WNV upon submission to Centre for Viral Zoonoses, South Africa, 2010–2018*.

| Variable |

No. WNV positive/total no. animals (%) |

No. WNV negative/total no. animals (%) |

Odds ratio (95% CI) |

p value† |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sign | ||||

| Fever | 2/8 (25.0) | 44/496 (8.9) | 3.4 (0.7–17.2) | 0.2 |

| Neurologic signs | 4/8 (50.0) | 422/496 (85.1) | 0.2 (0.0–0.6) | <0.05 |

| Ataxia | 2/8 (25.0) | 102/496 (20.6) | 1.3 (0.3–6.3) | 1.0 |

| Paralysis | 1/8 (12.5) | 63/496 (12.7) | 0.9 (0.1–8.0) | 1.0 |

| Hind leg paralysis | 1/8 (12.5) | 22/496 (4.4) | 3.0 (0.4–25.7) | 0.3 |

| Paresis | 2/8 (25.0) | 118/496 (23.8) | 1.1 (0.2–5.3) | 1.0 |

| Tongue paralysis | 0/8 | 4/496 (0.8) | Undefined | 1 |

| Recumbency | 2/8 (25.0) | 103/496 (20.8) | 1.3 (0.3–6.3) | 0.7 |

| Dyspnea | 3/8 (37.5) | 78/496 (15.7) | 3.2 (0.7–13.5) | 0.1 |

| Hemorrhage | 0/8 | 11/496 (2.2) | Undefined | 1 |

| Blindness | 0/8 | 11/496 (2.2) | Undefined | 1 |

| Icterus | 0/8 | 2/496 (0.4) | Undefined | 1 |

| Seizure |

0/8 |

30/496 (6.0) |

Undefined |

1 |

| Outcome‡ | ||||

| Sudden unexpected death | 2/11 (18.2) | 76/608 (12.5) | 1.5 (0.3–7.2) | 0.4 |

| Stillborn | 1/11 (9.1) | 15/608 (2.5) | 3.9 (0.5–32.3) | 0.3 |

| Abortion | 0/11 | 24/608 (4.0) | Undefined | 1 |

| Congenital deformities | 0/11 | 11/608 (1.8) | Undefined | 1 |

| Death | 9/11 (81.8) | 510/608 (84.4) | 0.8 (0.2–3.6) | 0.4 |

*WNV, West Nile virus. †p values <0.05 are significant. ‡Sudden unexplained death indicates animals found dead without an obvious reason; stillborn, abortion, and congenital deformities are related to potential cross-placental transmission; death refers to sick animals that subsequently died.

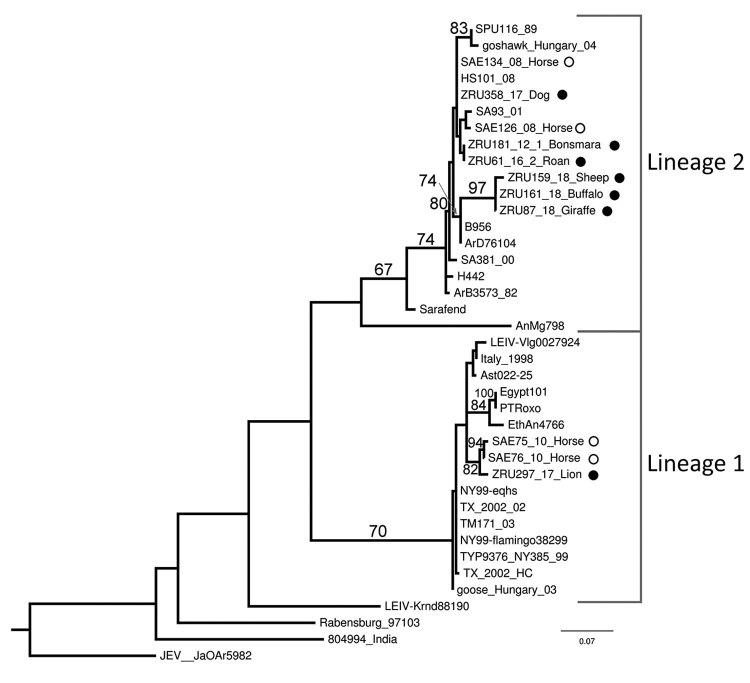

We subjected positive specimens to Sanger sequencing (Inqaba biotech, https://www.inqababiotec.co.za) and conducted sequence analysis with CLC-genomic workbench (https://www.qiagenbioinformatics.com), MAFFT (Multiple Alignment using Fast Fourier Transform) version 7 (http://mafft.cbrc.jp/alignment/server), and MEGA6.06 (https://www.megasoftware.net). We used RAxML (https://cme.h-its.org/exelixis/web/software/raxml) for maximum-likelihood phylogenetic analysis of the partial nonstructural protein 5 gene region (215 nt) and confirmed the RT-PCR results and WNV lineages (Figure 2). The lion from Kruger National Park (KNP) clustered with lineage 1 (bootstrap = 70), and all other animals clustered with lineage 2 strains from South Africa (bootstrap = 67) (Figure 2). One previous report found a lineage 1 strain that clustered with lineage 1 strains previously identified in South Africa (12).

Figure 2.

Maximum-likelihood phylogram of the partial (215-nt) nonstructural protein gene used for identification of West Nile virus infection in wildlife and nonequine domestic animals, South Africa, 2010–2018. Tree was generated with RAXML (https://cme.h-its.org/exelixis/web/software/raxml) using the general time-reversible plus gamma model with 39 taxa and the AutoMRE bootstopping function invoked (bootstraps >65 as branch support). Black circles indicate wildlife and nonequine domestic animal sequences from this study; open circles indicate horse sequences (3,12). Reference strains, GenBank accession numbers, and origins are as indicated in (4). GenBank accession numbers for the newly sequenced strains are ZRU87_18, MN270988; ZRU159_18_SA, MN270989; ZRU161_18_SA, MN27099; and ZRU181_12_1, KY176733. The sequences for strains ZRU358/17, ZRU061/16/2, and ZRU297/17 were <200 bp long and therefore could not be submitted to GenBank; the sequence data are available from the authors. Scale bar indicates nucleotide substitutions per site.

We used an epitope-blocking ELISA (13) to screen serum for WNV antibodies in 50 white rhinoceros (Ceratotherium simum) collected by the South African National Parks in March 2014 and 45 African buffalo in June 2016, all from KNP, and from 34 Nile crocodiles (Crocodylus niloticus) collected from northern KwaZulu-Natal during 2009–2012. We coated flat-bottom 96-well microtiter plates (CELLSTAR, Sigma Aldricht, https://www.sigmaaldrich.com) with 1:800 dilution of WNV cell lysate antigen, prepared according to (14) using strain HS101/08, passage 6, South Africa and WNV hyperimmune mouse ascites fluid polyclonal antibody (FC-M30200-06-1, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, https://www.cdc.gov/ncezid/dvbd/specimensub/arc) diluted 1:400 and horseradish peroxidase–conjugated rabbit antimouse IgG (BioRad Laboratories, https://www.bio-rad.com) (1:2000 dilution). We calculated the percentage inhibition of antibody binding with a cutoff value of 40% and confirmed positive reactions by microtiter virus neutralization test using a 103 50% tissue culture infectious dose stock culture (MRM61C, passage 6) (15). We detected WNV-specific antibodies in serum of 25 (50%) of white rhinoceros, of which 20 (80%) demonstrated neutralization at all 3 dilutions (1:8, 1:16, and 1:32) and 5 showed no neutralization, suggesting high-level WNV exposure. This finding highlights the prevalence of WNV in KNP despite a low number of reported clinical infections. No buffaloes or crocodiles were seropositive.

Conclusions

We recorded WNV (lineages 1 and 2) in wildlife and nonequine domestic animals in South Africa. Seroconversion to WNV was demonstrated in asymptomatic white rhinoceros from KNP. The data suggest severe disease and neurologic signs occur in species other than horses; these signs may be used for surveillance in areas of Africa where horses are less common to predict WNV outbreaks and predict spillover events into the human population. Wildlife and nonequine domestic animals are not as closely monitored for WNV as horses, and early detection is less likely. The short viremia associated with WNV infection may result in underreporting of positive animals if only RT-PCR is used for diagnosis, but a lack of conjugates for wildlife species complicates development of IgM ELISA. The epitope-blocking ELISA and microtiter virus neutralization test can be used for seroprevalence studies in animals other than horses because they are species-independent but do not differentiate between IgM and IgG and are not quantitative. Future work should focus on assay development for species other than horses.

Seasonality of West Nile virus in wildlife, nonequine domestic animals, and birds, South Africa, 2010–2018.

Acknowledgments

We thank all veterinarians and veterinary pathologists across South Africa who submitted samples, as well as Anna Jolles and Bryan Charleston for the buffalo serum samples.

This study was cleared by section 20 (12/11/1/1) approval through the Department of Agriculture Forestry and Fisheries, by the animal ethics committee (V057-15) (J.S.) and (H12/16) (M.V.) of the University of Pretoria and the PhD research committee. Buffalo samples were transported under a Red Cross permit (LDK2016/9/1) to the Biosafety Level 3 laboratory.

The work was funded through the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Global Disease Detection grant for zoonotic arboviruses under grant 1U19GH000571-01-GDD Non-Research CoAg with the National Health Laboratory Services project 23 and University of Pretoria Zoonotic Arbo and Respiratory Virus Group income-generated funds. J.S. received doctoral scholarships from the National Research Foundation (grant no. 95175), the Meat Industry Trust (grant no. IT8114/98), and the Poliomyelitis Research Foundation (grant no. 15/112) and a partial studentship from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Cooperative Agreement no. 5 NU2GGH001874-02-00 with the University of Pretoria.

Biography

Dr. Steyn is a virologist and PhD candidate at the Centre for Viral Zoonoses at the University of Pretoria. Her primary research focuses on investigating arboviruses with zoonotic potential at human–animal interface areas.

Footnotes

Suggested citation for this article: Steyn J, Botha E, Stivaktas VI, Buss P, Beechler BR, Myburgh JG, et al. West Nile virus in wildlife and nonequine domestic animals, South Africa, 2010–2018. Emerg Infect Dis. 2019 Dec [date cited]. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2512.190572

References

- 1.Murray KO, Walker C, Gould E. The virology, epidemiology, and clinical impact of West Nile virus: a decade of advancements in research since its introduction into the Western Hemisphere. Epidemiol Infect. 2011;139:807–17. 10.1017/S0950268811000185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pauli G, Bauerfeind U, Blümel J, Burger R, Drosten C, Gröner A, et al. West nile virus. Transfus Med Hemother. 2013;40:265–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Venter M, Pretorius M, Fuller JA, Botha E, Rakgotho M, Stivaktas V, et al. West Nile virus lineage 2 in horses and other animals with neurologic disease, South Africa, 2008–2015. Emerg Infect Dis. 2017;23:2060–4. 10.3201/eid2312.162078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gould LH, Fikrig E. West Nile virus: a growing concern? J Clin Invest. 2004;113:1102–7. 10.1172/JCI21623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zaayman D, Human S, Venter M. A highly sensitive method for the detection and genotyping of West Nile virus by real-time PCR. J Virol Methods. 2009;157:155–60. 10.1016/j.jviromet.2008.12.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O’Dell N, Arnot L, Janisch CE, Steyl JC. Clinical presentation and pathology of suspected vector transmitted African horse sickness in South African domestic dogs from 2006 to 2017. Vet Rec. 2018;182:715. 10.1136/vr.104611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blackburn NK, Reyers F, Berry WL, Shepherd AJ. Susceptibility of dogs to West Nile virus: a survey and pathogenicity trial. J Comp Pathol. 1989;100:59–66. 10.1016/0021-9975(89)90090-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Niekerk S, Human S, Williams J, van Wilpe E, Pretorius M, Swanepoel R, et al. Sindbis and Middelburg Old World alphaviruses associated with neurologic disease in horses, South Africa. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21:2225–9. 10.3201/eid2112.150132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van Eeden C, Zaayman D, Venter M. A sensitive nested real-time RT-PCR for the detection of Shuni virus. J Virol Methods. 2014;195:100–5. 10.1016/j.jviromet.2013.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Niekerk M, Freeman M, Paweska JT, Howell PG, Guthrie AJ, Potgieter AC, et al. Variation in the NS3 gene and protein in South African isolates of bluetongue and equine encephalosis viruses. J Gen Virol. 2003;84:581–90. 10.1099/vir.0.18749-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yaeger M, Yoon K-J, Schwartz K, Berkland L. West Nile virus meningoencephalitis in a Suri alpaca and Suffolk ewe. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2004;16:64–6. 10.1177/104063870401600111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Venter M, Human S, van Niekerk S, Williams J, van Eeden C, Freeman F. Fatal neurologic disease and abortion in mare infected with lineage 1 West Nile virus, South Africa. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17:1534–6. 10.3201/eid1708.101794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blitvich BJ, Marlenee NL, Hall RA, Calisher CH, Bowen RA, Roehrig JT, et al. Epitope-blocking enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays for the detection of serum antibodies to west nile virus in multiple avian species. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:1041–7. 10.1128/JCM.41.3.1041-1047.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ksiazek TG, West CP, Rollin PE, Jahrling PB, Peters CJ. ELISA for the detection of antibodies to Ebola viruses. J Infect Dis. 1999;179(Suppl 1):S192–8. 10.1086/514313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zaayman D, Venter M. West Nile virus neurologic disease in humans, South Africa, September 2008-may 2009. Emerg Infect Dis. 2012;18:2051–4. 10.3201/eid1812.111208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Seasonality of West Nile virus in wildlife, nonequine domestic animals, and birds, South Africa, 2010–2018.