Abstract

Mice with Plp1gene duplication model the most common form of Pelizaeus-Merzbacher disease (PMD), a CNS disease in which patients may suffer respiratory complications. We hypothesized that affected mice would lack airway responsiveness compared to wild-type and carrier mice during methacholine challenge. Wild-type (n=10), carrier female (n=6) and affected male (n=8) mice were anesthetized-paralyzed, tracheostomized and ventilated. Respiratory mechanics were recorded at baseline and during escalating doses of nebulized methacholine followed by albuterol. Lung resistance (RL) was the primary endpoint. Lung tissues were assayed for inflammatory and histological differences. At baseline, phase angles were higher in carrier and affected mice than wild-type. Dose-response RL curves in affected and carrier mice indicated a lack of methacholine response. Albuterol reduced RL in wild-type and carrier, but not affected mice. Affected mice exhibited lower interleukin (IL)-6 tissue levels and alveolar inflammatory infiltrates. Affected and carrier mice, compared to wild-type, lacked airway reactivity during methacholine challenge, but only affected mice exhibited decreased lung tissue levels of IL-6 and inflammation.

Keywords: Pelizaeus-Merzbacher disease, airway pharmacology, lung mechanics, phase angle

1. INTRODUCTION

Pelizaeus–Merzbacher disease (PMD), an X-linked neurodegenerative disease characterized by dysmyelinating (improper myelin formation) and demyelinating (degradation of myelin) processes in the central nervous system (CNS). PMD [MIM#312080] is caused by mutations of the proteolipid protein 1 gene [PLP1; MIM#300401] that encodes proteolipid protein (PLP), the most abundant protein in CNS myelin [1–2]. PLP was shown to be involved in compaction of myelin and in the formation and signaling of integrin receptor complexes in in-vitro animal cell studies [3–5]. Patients with PMD usually present with nystagmus, hypotonia, and titubations at birth or in early childhood, slowly progressing to ataxia and spasticity later in life, and hypomyelination is observed on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the CNS [6]. Heterozygous female carriers are not usually PMD affected/symptomatic [7]. The estimated prevalence of PMD in the United States is 1:200,000 to 1:500,000 [6]. The mortality rate (per million individuals per year) for ages <5 and ≥5 years is estimated to be 0.037 and 0.033, respectively, and death ranges from 4 to 66 years [8].

PMD can be caused by mutations that affect the coding region and splicing of PLP1; however, the most common mutation is the duplication of a genomic region that includes the PLP1 gene [9]. Duplication of PLP1, which accounts for approximately 62% of PMD cases when strict clinical criteria are applied [10], results in the classical form of disease that is typically in the middle of the clinical severity spectrum for PMD. Duplication may lead to overexpression of PLP, which has been shown to cause both brain inflammation and abnormal trafficking of PLP to the cell surface of oligodendrocytes, suggesting mechanisms for disease pathogenesis [11–12]. There are no therapeutic options available for PMD, but compounds that lower the expression of PLP1 may provide a rational treatment for PMD that is due to an extra copy of the gene.

Although PMD is a neurological disease of the white matter of the CNS in origin, it affects many other organ systems including the respiratory system, so a multidisciplinary approach is recommended for optimal care [6]. Airway aspiration and/or severe scoliosis are respiratory complications, which are major causes of morbidity and mortality [6, 13]. The severe or connatal/congenital form of PMD features respiratory distress, stridor and pharyngeal weakness [14].

In this study, we tested whether PMD due to genomic duplication is associated with disruption of respiratory autonomic homeostasis. We used a mouse model, called Plp1dup, that has a genomic duplication that includes Plp1 and is similar in size and structure to most human PMD duplications. These mice develop neurological sequelae that model human PMD [15], but a respiratory phenotype has not been described in this Plp1dup model. We used methacholine as a drug challenge to the respiratory control system in the mouse model. Methacholine is a cholinergic synthetic analog of acetylcholine (ACh), an important neurotransmitter in both the CNS and the peripheral nervous system that produces smooth muscle contractions of the airways through muscarinic M3 receptors located in the tracheobronchial tree and in different regions of the brain [16]. The aims of this translational study were to compare respiratory mechanics under rest, during methacholine challenge, and after β2-adrenoceptor agonist exposure to determine biomarkers of lung inflammation, and to examine structural lung tissue differences among wild-type, carrier, and Plp1dup affected mice. Our translational studies on Plp1dup mice are ongoing with the focused goal of identifying the respiratory phenotype of the disease, the mechanisms of disease pathogenesis, and identification and testing of therapeutic interventions.

2. METHODS

2.1. Animal model

Generation of the Plp1dup murine model of PMD using Mutagenic Insertion and Chromosome Engineering Resources (MICER) and characterization of the neurological phenotype are as previously described [15, 17]. Plp1dup mice are an appropriate model for our studies because they have a genomic duplication on the X-chromosome that includes Plp1 and is similar in size and structure to the duplications detected in human PMD patients and because the neurological phenotype is similar to that in human patients [15, 18–19].

2.2. Animal preparation

This study of methacholine challenge was approved by the Nemours Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, Department of Nemours Biomedical Research, in accordance with the National Institutes of Health guidelines. Three groups, wild-type mice (n=10; five females and five males), carrier mice (n=6; all females), and Plp1dup affected mice [15] (n=8; all males), were studied at 6 months of age -equivalent to 20–30 years old in human age- [20]. All mice were on a B6.129 mixed background. Animals were anaesthetized with a ketamine-xylazine cocktail (50 mg/mL:10 mg/mL, 1:1 ratio) by intraperitoneal (IP) injections at a maximal dose of 0.08 mL/10 grams (range 0.04–0.08 mL/10 grams). Oximetry, heart rate, percentage of tail perfusion were monitored using a pulse oximeter (MouseSTAT, Smiths Medical, Waukesha, WI). Body temperature was monitored using a laser thermometer (ThermoWorks, Alpine, UT) and maintained using a far infrared warming pad (Kent Scientific Corporation, Torrington, CT).

2.3. Respiratory inductance plethysmography

Before invasive procedures in the unconscious animals were performed, respiratory inductance plethysmography was performed to measure thoracoabdominal motion indices of asynchronic breathing patterns (phase angle and phase relation during total breath [PhRTB] and labored breathing index [LBI]). These measurements are not invasive as compared with conventional measurements of resistance and compliance in unconscious mice, where direct measurements of the airway flow at the tracheal opening are required. Measurements were performed using inductive bands (RespiRod bands, Wilmington, DE) designed by the first author and collaborators at the Nemours Pediatric Engineering Research Laboratory (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

RespiRodbands. The minimum total stroke volume that these bands can detect is 3 cc at a respiratory frequency of 120 breaths per minute, with a minimum positive end-expiratory pressure of 3 cm H2O.

These bands were designed for use with a snap connector and cloth fastener for use with a RespiTrace device, the SomnoStarPT Unit (Sensormedics, Yorba Linda, CA), and in mice ≥28 g. Preliminary testing was performed to assure correct operation, which consisted of observation of the Lissajours and Konno-Mead loops at different respiratory frequencies and positive end-expiratory pressures. After ensuring that the animal skin was dry and free of oil or other substances, the animal was placed on top of the two bands; the top band (RC) was positioned under the armpit of the upper limb and the bottom band (AB) at the largest abdominal circumference parallel to the RC band.

The respiratory inductance plethysmography method uses sinusoidal coils of wire sewn into elastic cloth bands. Co Flex NL (Andover, Salisbury, MA) elastic bands were used, which were identical -with respect to material properties- to the materials used in the Respiratory Plus bands (RespiBands Plus; VIASYS Respiratory Care, Yorba Linda, CA) approved for clinical use. The elastic material was shortened to 1.5-cm wide and 1-mm thick. This elastic bandage works effectively since it binds to itself and maintains elasticity when compressed. The original amplitude and frequency of the field-wire waveform in the Respiratory Plus band was not sensitive enough to pick up the diminutive movements of the rodent, so we developed the RespiRod bands as follows. We designed a custom apparatus to hold straight pins at the vertices of a new proposed field-wire waveform. A strip of the CoFlex elastic bandage was pressed onto the sharp ends of the pins protruding from the apparatus. The wire, removed from unused Respiratory Plus bands, was woven around the extended pins. A second strip of the elastic bandage was pressed onto the pins over the woven wire to complete the RespiRod band. A sandwich of bandage and wire was compressed as much as possible to stabilize the assembly and the pins were carefully removed. Once free, the new band was fed through a custom-made roller press to thoroughly compress the elastic bandage and trap the wire in between. Finally, the bands were cut to width, and snaps were attached to the measuring equipment. Several different amplitude and frequency configurations were tried until the desired results were achieved.

The principles involved in these RespiRod bands were the same as those of Respiratory Plus bands used in the clinical settings; the measurements were collected at the chest wall for thoracoabdominal motion analysis, usually with the respiratory inductance plethysmography technique. The signals from the bands around the RC and the abdomen (ABD) were treated mathematically as sine waves: bands phase angle (Ø) was then calculated from the Lissajours loop according to the equation sin Ø = (m/s) where m is the line parallel to the abscissa on the RC-ABD plot at one-half the distance between the maximal RC perpendicular intercept and the origin, and s is the length of a line from the maximal ABD perpendicular intercept minus the origin [21]. A phase angle of 0 degrees represents perfect synchrony between the chest and abdominal compartments. Higher phase angles represent greater degrees of asynchronous breathing. A phase angle of 180 degrees represents complete asynchrony. A variety of markers of thoracoabdominal asynchrony have been analyzed, to express the degree to which chest and abdominal excursions are out of phase (asynchronous): Phase angle in degrees; PhRTB; LBI, rib cage contribution to tidal volume (% rib cage/tidal volume). We used the respiratory inductance plethysmography technique alongside conventional measurement of resistance and compliance in unconscious mice to identify any correlation before tracheal surgical opening.

2.4. Baseline respiratory mechanics

Mice were tracheostomized, a 19-gauge bevel tracheal cannula was inserted into the trachea, and ligation using surgical threads was completed to avoid leak and disconnections. Mice were immediately mechanically ventilated and connected to the pneumotachograph of the plethysmography/ventilator chamber FinePointe RC (Buxco Research Systems, Wilmington, NC, USA). Respiratory function was measured using this plethysmography system, which collects invasive respiratory resistance and compliance data in anesthetized animals that are either tracheostomized or intubated. A ventilator controlled by volume, which is incorporated into the system, supports protocol-driven positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) studies. Assessment involved measurements of flow and pressure at the mouth and/or esophageal openings. ECG leads were placed for monitoring heart rate. Body temperature was maintained using the heated table of the chamber.

Mice were paralyzed by IP injections of pancuronium bromide (0.1 mg/kg). If sudden cardiac rate increases were found (>20% of the baseline), administration of more anesthetic cocktail was performed. Following instrumentation to obtain stable conditions inside the plethysmography chamber, a 10-minute acclimation period was performed. Tidal volumes of 0.05 mL/10 g, rate of 120 breaths/min, 5 cm H2O of PEEP and 3 LPM of O2 were used in all groups. A baseline recording [dynamic lung resistance (RL), dynamic lung compliance (Cdyn)] without nebulization (resting mechanics) was made at the end of the acclimation period, followed by a control recording using normal saline (0.9% NaCl). Baseline transpulmonary measurements were performed as described below. The second port of the pressure transducer was filled with 5 mL of ethanol to 20 mL of water. A two-valve stopcock was used to block the pressure port with an attached 10-mL syringe containing degassed water. An esophageal tube was connected to the end of the syringe; thereafter, the tube was advanced through the hole of the manifold chamber port. The esophageal tube was marked at a distance that approximates the level of the lungs. This water-filled tube was advanced via the mouth. Optimum placement of the balloon aiming for a 3 to 5 cm H20 deflection was confirmed by real-time monitoring of pressure tracings.

2.5. Methacholine challenge and short-acting β2-adrenoceptor agonist administration

Once a stable control-saline measurement was recorded, the plethysmography system described in section 2.4 was used to measure the effect of methacholine on airway responsiveness. Airway challenge used escalating doses of methacholine (0.1, 0.3, 0.7, 1.5, 3, and 6 mg/mL) lasting 1 minute each at a volume of 0.05 mL. Response time and recovery time were set at 2 minutes and 1 minute, respectively. A standard commercial clear Plexiglass in-line aerosol block (Buxco Research Systems, Wilmington, NC, USA) and nebulizer head with a particle size of 4–6 micron Mass Median Aerodynamic Diameter and a rate output of approximately 300 μl/min (Aerogen, Inc., Galvan, Ireland) was used. Respiratory mechanics and vital signs were measured at rest, baseline, and every 4 min during methacholine (Provocholine, Methapharm Inc, Ontario, CA) administration. The RL, heart rate and tidal volumes were recorded during the methacholine challenge. At the end of the challenge, animals were treated with one nebulization of a short-acting β2-adrenoceptor agonist, albuterol sulfate inhalation solution, 0.5% (Bausch & Lomb Incorporated, Tampa, FL) at a dose of 0.0238 μg/mL. The same nebulizer head and aerosol block delivery systems were used to evaluate dilation response. All drug delivery times were set at 4 minutes; the methacholine challenge lasted 40 minutes. Data derived from these measurements were stored automatically by the FinePointe RC software version 1.0 (Buxco Research Systems, Wilmington, NC, USA), which interfaces with the plethysmography/ventilator chamber. R L was the primary endpoint, and data presented correspond to the mean of the first 3 minutes recorded after each drug exposure expressed as absolute values.

2.6. Tissue preparation and histopathology protocol

Immediately after the physiological measurements were completed, animals were euthanized using a solution of Euthasol® (Sodium pentobarbital 390 mg with 50 mg/mL sodium phenytoin), via IP injections at 0.1 mg per gram of animal weight, and thoracotomy was performed followed by lung tissue dissection. A constant positive end-expiratory pressure of 5 cm H2O was maintained during tissue harvesting. Right non-dependent lung samples (highest part of the lungs in relation to gravity) were dissected, formalin-fixed and prepared for histological and histomorphometrical analyses. Right lung non-dependent tissue sections of wild-type (n=10), carrier (n=6), and affected (n=8) mice were stored and removed from 10% formaldehyde after 48 hrs. They were washed in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) solution and embedded in paraffin. The embedded tissue was sectioned (0.5-μm), and four samples of each were mounted on Superfrost Plus slides. Paraffin was removed from the tissues, and tissues were placed in Bouin’s fixative, and stained using hematoxylin & eosin (H&E) according to standard protocols. The samples were examined by standard light microscopy (NIS-Elements BR 3.1, Tokyo, Japan). A board-certified pathologist (PAK), who was blinded to the group of animals, analyzed each sample.

2.7. Tissue preparation and cytokine extractions

Mice were dissected and left lungs were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C, followed by homogenization at a later time. Lung tissue samples (50 mg) were washed twice with PBS and homogenized in RIPA buffer (150 mM NaCl, 1.0% IGEPAL® CA-630, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 50 mM Tris, pH 8.0; in a proportion of 10 μl to 1 mg of lung tissue) with protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO) at a 1:100 dilution. The levels of rat interleukin (IL)-6 and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α in the supernatant liquid generated from the homogenate were measured with quantitative enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using commercially available rat ELISA kits for IL-6 and TNF-α (Invitrogen Corporation, Camarillo, CA). The minimum detectable dose of mouse TNF-α and IL-6 was <3 pg/mL. Recombinant proteins were used as high and low controls, and the ranges for their respective immunoassays were as follows: High control mouse TNF-α (430–1150 pg/mL), low control mouse TNF-α (25–55 pg/mL); high control mouse IL-6 (160–415 pg/mL) and low control mouse IL-6 (15–30 pg/mL). Inter-assay and intra-assay coefficients of variation were <10% for both immunoassays.

2.8. Data analysis and statistics

Continuous variables were summarized overall by mean and standard error of the mean, and continuous non-normal dependent variables were reported using medians (interquartile range), unless otherwise indicated. Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s posttest was performed for the physiological and inflammatory markers outcomes. Confidence intervals (CI) were set at 95% with at alpha significance level of 0.05. Our primary end-point was the RL lung function parameter through methacholine challenge. Each methacholine dose-response curve was semi-log10 transformed and fitted to the Hill equation using the least square method to provide estimated half maximal effective concentration (EC50) values. Statistical analysis was performed using Friedman test with Dunn’s multiple comparison. For the bronchodilation outcomes, statistical analysis was performed by Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test and the percentage change was calculated as mean % post-challenge – higher MCh dose/higher MCh dose*100. All assumptions were tested for normalization. In case of a violation of any assumption, appropriate transformations were taken or non-parametric tests were performed. Statistical analysis was completed using Graph Pad Prism version 5.02 (San Diego, CA, USA) and SPSS version 19 (IBM, Chicago, IL, USA).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Baseline outcomes

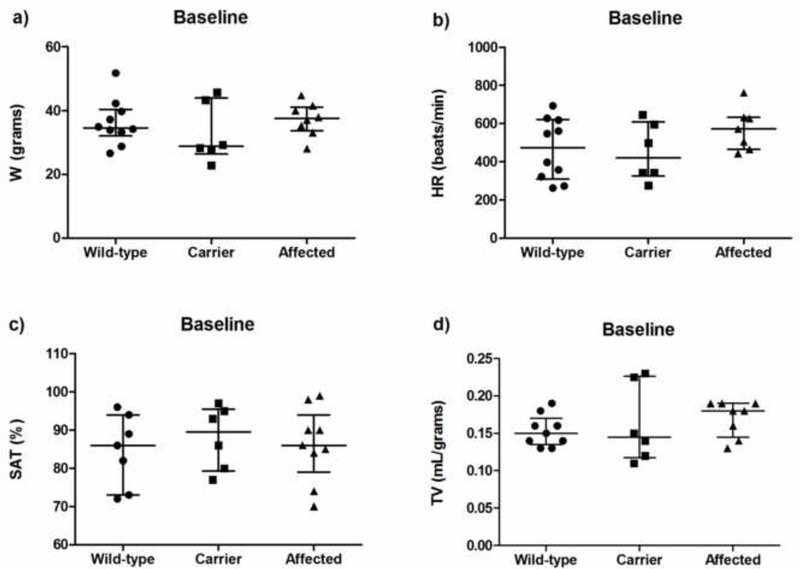

As estimated, medians (interquartile range) of body weight in grams, heart rate, oxygen saturation, and tidal volumes per weight in grams were similar in the wild-type, carrier and affected mice (Fig. 2). In comparison with the wild-type mice, respiratory phase angles were higher in the carrier and affected mice, P=0.04 (Fig. 3a). No significant differences in PhRTB, LBI, and static lung compliance (Cst) were observed between groups (Figs. 3b–d). No differences in RL or Cdyn were detected between the groups at baseline, and the medians for RL and Cdyn in wild-type, carrier, and affected mice were not different (Fig. 4).

Figure 2.

Baseline vitals and respiratory profile in wild-type (n = 10), carrier (n = 6), and affected (n = 8) mice. a) Weight [grams]: 34.5 (32.1 – 40.3) vs. 28.8 (26.4 – 43.9) vs. 37.4 (28 – 41.1) P = 0.53; b) Heart rate [beats/min]: 472 (310 – 621) vs. 421 (326 – 608) vs. 572 (465 – 633) P = 0.30; c) Oxygen saturation [%]: 86 (73 – 94) vs. 89 (79 – 95) vs. 88 (84 – 96) P = 0.75; d) Tidal volume [mL/grams]: 0.15 (0.13 – 0.17) vs. 0.14 (0.11 – 0.22) vs. 0.18 (0.13 – 0.19), P = 0.46. Carrier, carrier female mice; Affected, Plp1dup male mice; W, weight; HR, heart rate; SAT, oxygen saturation; TV, tidal volume.

Figure 3.

Thoracoabdominal indices and lung static compliance (Cst) in wild-type, carrier and Plp1dup affected mice at baseline. a) Phase angles were significantly higher in the affected and carrier groups compared with the wild-type group in spontaneously breathing mice: medians (interquartile range) in carrrier and affected mice for phase angle were 64 (43 – 114) and 75 (34 – 156) degrees, respectively, P ≤ 0.05. Wild-type group demonstrates phase angles of 18 (13 – 31) degrees. b) Phase relation during total breath (PhRTB) percentages were not different between groups: medians (interquartile range) in wild-type, carier, and affected were 34% (23 – 52%), 41% (37 – 44%), and 55% (44 – 60%), respectively, P = 0.061. c) Labored breathing index (LBI) values were not different between groups: medians (interquartile range) in wild-type, carrier, and affected were 1.10% (1.02 – 1.10%), 1.10% (1.05 – 1.10%) and 1.10% (1.00 – 1.12%), respectively, P = 0.987. d) Static lung compliance (Cst) values in mechanically ventilated wild-type, carrier, and affected mice were: 0.022 (0.020 – 0.034), 0.028 (0.022 – 0.032), and 0.031 (0.021 – 0.038) mL/cm H20, respectively, P = 0.477.

Figure 4.

Baseline respiratory mechanics in wild-type (n = 10), carrier (n = 6), and affected mice (n = 8). a) Dynamic lung resistance [cmH20/L/s]: 1.41 (1.22 – 1.59) vs. 1.3 (1.09 – 1.50) vs. 1.2 (0.9 – 1.28) P = 0.09, b) Dynamic lung compliance [mL/cmH20]: 0.022 (0.016 – 0.031) vs. 0.028 (0.022 – 0.030) vs. 0.028 (0.018 – 0.035), P = 0.68. Affected, Plp1dup male mice; RL, dynamic lung resistance; Cdyn, dynamic lung compliance.

3.2. Correlations between baseline plethysmography measurements

Correlations between baseline plethysmography measurements are shown in Table 1. In the wild-type group, very strong correlations were found between PhRTB and RL, and between PhRTB and Cdyn. LBI correlated less strongly with RL and Cdyn, and phase angle demonstrated a moderate correlation. In the carrier group, only the phase angle correlated strongly with RL and moderately with Cdyn. In the affected group PhRTB correlate with RL and LBI with Cdyn.

Table 1.

Correlation coefficients between baseline respiratory inductance plethysmography measurements, and conventional measurements of lung resistance (RL) and lung compliance (Cdyn) in unconscious mice.

| Group/parameter | Phase angle (degrees) | PhRTB (%) | LBI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-type | ||||

| RL | cmH2O/mL/sec | 0.40 | 0.80 | 0.77 |

| Cdyn | mL/cmH2O | −0.40 | −0.80 | −0.77 |

| Carrier | ||||

| RL | cmH2O/mL/sec | −0.60 | 0.30 | −0.35 |

| Cdyn | mL/cmH2O | 0.56 | −0.35 | 0.36 |

| Affected | ||||

| RL | cmH2O/mL/sec | 0.14 | 0.54 | −0.37 |

| Cdyn | mL/cmH2O | 0.10 | −0.20 | 0.52 |

PhRTB = phase relation during total breath; LBI = labored breathing index. Spearman’s correlation strength: rs .80 – 1.0 “very strong”, rs .60 – .79 “strong”, rs .40 – .59 “moderate”.

3.3. Pharmacologic outcomes

The RL dose-response curves (Fig. 5) demonstrate differences expressed by the left shift and slope of the wild-type group curve, which showed that methacholine produced a dose-dependent increase in RL, as expected. The RL log curve showed a fit of a dose-response curve to a set of data that do not delineate a top plateau; because the dose-response did not extend across a wide enough range of doses, the estimated concentration of methacholine that provoked a response halfway between the baseline and maximum response (EC50) estimated values were not obtained. The LogEC50 in the affected group did not converge (flat curve), indicating no response to any dose of methacholine. The dose-response curve of the carrier group did not delineate a top plateau, in addition to the lack of response to methacholine. Statistical analysis also demonstrated that methacholine increased RL values at a higher dose in the wild-type group (P = 0.0003), whereas carrier and affected mice lacked sensitivity to methacholine. A difference was found within the wild-type group between the baseline and 6 mg/mL of methacholine (P = 0.021). Figure 6 illustrates the heart rate and absolute changes in this parameter for all groups (wild-type, carrier, and Plp1dup affected mice) after aerosol administration of saline solution and escalating doses of methacholine. As shown, no group difference was noted after saline administration (P > 0.05). The heart rate trended higher in the wild-type group over time during methacholine administration, post test for linear trend (P = 0.0094). The heart rate did not trend in the carrier (P = 0.72) or affected group (P = 0.80). Group differences trended higher in the wild-type compared to the affected group (CI, − 0.8187 to 0.5163); however, a group difference was noted between the wild-type and carrier group at 0.7 mg/mL of methacholine (CI, − 1.404 to − 0.004030), the carrier group having a lower heart rate.

Figure 5.

Dynamic lung resistance (RL) trend to nebulized methacholine challenge in intubated, mechanically breathing 6-month-old mice. Schematic representation of the semi-log10 dose-response curves observed in wild-type, carrier, and Plp1dup mice in RL. Methacholine induces significant increases in RL as a function of dose in wild-type mice, whereas carrier and affected mice lacked sensitivity to methacholine (**P = 0.0003). A difference in the Dunn’s multiple comparison test was found between baseline and 6 mg/mL of methacholine in the wild-type group (#P = 0.021). Each data point is derived from n = 10 wild-type, n = 6 carrier, and n = 8 affected mice and presented as mean +/− standard error of the mean (SEM). Y-axis ordinate shows responses expressed as absolute values.

Figure 6.

Hear rate (HR) trend to nebulized methacholine challenge in intubated, mechanically breathing 6-month-old mice. Each data point is presented as mean +/− standard error of the mean (SEM). Y-axis ordinate shows responses expressed as absolute values. # P = 0.0049 in wild-type, and *P = < 0.05 between wild-type and carrier.

Following treatment with albuterol sulfate (Fig. 7a–c), wild-type and carrier groups showed a reduction in RL: − 10%, P = 0.019 and − 21%, P = 0.015, respectively, whereas the fall of RL in the affected group was not significant (− 5.8%, P = 0.125).

Figure 7.

Plots of percentage of change in respiratory resistance (RL) for each group, before and after nebulization of a short-acting β2-adrenoceptor agonist (albuterol). a) Wild-type group (n = 9) showed reduction in RL (− 10%, lower 95% CI = − 24.6 %); b) Carrier group (n = 6) showed significant airway dilation (− 21%, lower 95% CI = − 40 %); and c) Affected group (n = 8) demonstrated no reduction in RL (− 5.8%, lower 95% CI = − 0.7%). MCh, methacholine; RL, dynamic lung resistance.

3.4. Lung inflammatory biomarkers outcomes

In comparison with wild-type and carrier groups, concentrations of IL-6 in lung tissue were lower in the affected group (Fig. 8). No differences in lung levels of TNF-α were found in the affected group compared with wild-type and carrier groups: medians in affected (n = 6), wild-type (n = 5) and carrier mice (n = 4) for TNF-α were 453.3 (308.4 – 544.5), 449.3 (406.9 – 450.3) and 458.6 (429.6 – 487.7) pg/mL, respectively (P = 0.87).

Figure 8.

Levels of interleukin (IL)-6 cytokine in tissue homogenates after methacholine nebulization challenge and β2-adrenoceptor agonist exposure in intubated and mechanical breathing mice. Interleukin (IL)-6 was significantly lower in the affected group compared with the wild-type and carrier groups: medians (interquartile range) in wild-type (n = 6), carrier (n = 4), and affected (n = 6) for IL-6 were 184.9 (158.4 – 245.0), 231.5 (193.9 – 304.6) and 133.2 (106.0 –141.3) pg/mL, respectively, *P = 0.0049.

3.5. Lung histological outcomes

Lung histology micrographs of the wild-type and carrier groups at high magnification (200X) (Fig. 9 a–b) demonstrated normal alveolar morphology without septal widening. Alveolar septa show minimal to no inflammation in these groups. Affected mouse lungs (Fig. 9c) were characterized by patchy alveolar septal widening with a mixed cellular inflammatory infiltrate. At higher magnification (200X and 400X), the inflammatory infiltrate was comprised of mostly lymphocytes, histiocytes, and neutrophils (not shown). There was also some associated vascular congestion and mild hemorrhage in the affected group.

Figure 9.

Representative histology middle right non-dependent lung sections of a wild-type (a), carrier (b), and affected [Plp1dup ] 6-month-old mice (c) following endpoint measures. a) Normal alveolar morphology with no to minimal diffuse inflammation within alveolar septa. b) Normal alveolar morphology with none to mixed partners of patchy and diffuse mild inflammation within alveolar septa. c) Patchy moderate inflammation within alveolar septa with further septal thickening (rectangular areas). Hematoxylin and eosin stain; magnification: 200X.

DISCUSSION

Experimental animal models of PMD due to duplication, mainly rodent models, are valid models because they show signs of deficits that resemble the neurological disease in PMD patients [15, 22]. They have been used to provide information on the mechanisms of the disease at the organ, cellular, and molecular levels [12, 23]. These models are being used as surrogates to study human PMD. However, the majority of these models are targeted to understanding the neurologic pathways related to PMD. The scope of the present study is on the respiratory phenotype of the disease. We used a model of PMD, Plp1dup [15], characterized by a genomic rearrangement that leads to a neurologic phenotype similar to the pattern seen in human PMD patients with duplications that is novel compared to previous mouse models made by autosomal insertion of multiple extra copies of Plp1. PMD has an X-linked recessive inheritance pattern; therefore, these differences observed between the groups are chromosome-related, rather than sex-related, as there was little variability of the outcome measures in the wild-type group comprising equal numbers of male and female mice.

This is the first study to compare the effects of a muscarinic receptor agonist and short-acting β2-adrenoceptor agonist in this Plp1dup pre-clinical model of PMD. The endpoint used to quantify airway responses in clinical grounds is usually a lung function drug challenge, as it is in this translational study. At baseline, on average, the Plp1dup affected group showed an increase in the degree of phase angle compared to the wild-type and carrier groups (Fig. 3) during the thoracoabdominal motion analysis. Thoracoabdominal motion analysis is the non-coincident movement of the rib cage and abdomen during breathing, expressed mainly by the phase angle [21, 24]. The phase angle ranges in general from zero degrees (synchronous breathing) to 180 degrees (paradoxical breathing) with the asynchronous breathing pattern in between (90 degrees). However, based on our clinical experience, an abnormal phase angle is generally more than 25 degrees [25]. The phase angle and the other indexes of thoracoabdominal motion analysis are non-specific makers of thoracoabdominal synchrony; therefore, the thoracoabdominal asynchrony must be interpreted in the context in which it occurred [26]. PhRTB, LBI and phase angle are important indirect noninvasive markers of respiratory mechanics, which explain the relationship between these measurements and the conventional measurements of resistance and compliance (Table 1), as previously shown with phase angle in a pediatric study [27]. Our study demonstrated no differences between groups in RL, Cdyn, Cst, or any other basic respiratory parameter at baseline; thus, the more abnormal breathing pattern detected in the affected group may represent neuromuscular pharyngeal weakness, an effect of the anesthetic drugs or a combination of these factors. In this regard, phase angles in general are not influenced by gender [28] and gender differences are unlikely source of the elevated phase angles, since the phase angles were high in both affected mice, (which were all male), and carrier mice, which were all female; a more plausible reason is perhaps upper airway obstruction. Mice are obligatory nose breathers; however, nostril obstructions are not a characteristic of PMD, but dysarthria is commonly cited as a clinical sign of PMD [2] Dysarthia could result from neurological injury affecting the muscles that assist in the production of speech, suggesting that PMD patients may have also pharyngeal weakness, which is perhaps the most likely cause of obstruction in Plp1dup affected mice, but this needs to be clarified with further animal studies.

The RL dose-response studies revealed that methacholine produced a dose-dependent increase in RL in wild-type, but not in affected or carrier mice. The unchanged trend in the affected and carrier groups, in addition to the lower heart rate episodes in the carrier group, suggested autonomic dysfunction in the parasympathetic nervous system. With regard to the dose-response curve, higher concentrations of methacholine were not used because they produced lethal bradyarrhythmias in Plp1dup affected and carrier mice in the planning stage of this study. Bradyarrhythmia is a well known muscarinic side effect of methacholine at higher doses [29]. However, the doses used herein were not suboptimal since we achieved a response in the wild-type group (Fig. 6).

In the normal murine physiological state, methacholine challenge increases resistance through M3 muscarinic receptors [30], and this increment in lung resistance may reflect both airway narrowing changes and alteration in the lung periphery [31]. The lack of sensitivity to methacholine found in the carrier and affected mice may be due to a dysfunction in bronchial autonomic homeostasis that does not allow these processes to occur. This dysfunction could be a direct result of demyelination of CNS pathways leading to abnormal regulation of bronchial motor tone, or due to more local peripheral mechanisms, such as altered neural control by the autonomic nervous system or airway smooth muscle cell abnormalities involved in bronchial motor tone function in the lung. In this regard, Oldenburg et al. [30] suggested that ethanol-induced suppression of lung responsiveness in mice was not a direct result of CNS effects because they also observed suppression in whole lung slices and isolated cultures of airway smooth muscle cells.

With regard to other PMD animal models, pathologic alteration in respiratory control to a hypoxia challenge in a myelin-deficient rat model showed similarities to the fatal phenotype of the disease, presumably linked to a selective disruption of central processing –caudal brainstem- [dummy_data] of afferent neural input from peripheral chemoreceptors involved in ventilatory chemosensory responses [32]. In contrast, our Plp1dup model tolerated low oximetry saturations—as low as 84%, which is similar to the duplication phenotype, in which respiratory alterations are not severe. Innervation of the smooth muscle of the respiratory tract is a complex process. The parasympathetic nervous fibers are responsible for the baseline normal bronchial tone (bronchoconstriction state) with ACh as the primary neurotransmitter [33], whereas bronchodilation by means of β2-receptors (sympathetic) stimulation balances this baseline effect. Short-acting β2-adrenoceptor agonists such as albuterol have been the standard therapy for the symptomatic treatment of broncoconstriction [34]. The pharmacological effect of albuterol—relaxation of bronchial smooth muscle and anti-inflammatory effects—are at least in part attributable to the increase in cAMP levels and activation of β2-adrenoceptors [35]. The significant reduction in RL in the wild-type and carrier groups following albuterol in our studies (Fig. 6a–b) demonstrated stimulation of the β2-adrenoceptors leading to the dilation effect. The percentage dilation was prominent in the carrier group in comparison to the one found in the wild-type group, which leads to the speculation that partially unopposed bronchial tone occurs due to the dysfunction of the parasympathetic fibers, receptors, or neurotransmitters. By comparison, the affected group lacked both bronchochonstriction and bronchodilation responses. Thus, we speculate that altered methacholine/albuterol-associated airway responses in this study may be mediated by a mechanism other than CNS reflex responses, and may reflect differences in intrinsic autonomic nervous system reflex responses involving receptor function, neurotransmitters, or signal transduction within the effector organ or in its surroundings [29].

PLP1 tissue-specific pattern of mRNA expression has been reported in the medulla oblongata and in the spinal cord of humans, and Plp1expression in mice was mainly detected in the spinal cord [36]. Myelinated preganglionic fibers of both the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) and parasympathetic nervous system (PNS) arise from these organs via the upper six thoracic segments of the spinal cord or the pneumogastric nerve. These preganglionic fibers appear to have Schwann cells supporting the myelin sheet [37] and their function is to reach the unmyelinated postganglionic fibers of both autonomic nervous systems, which finally innervate the lung and/or the surrounding tissue via efferent and afferent autonomic fibers. The majority of the fibers are parasympathetic fibers providing the constricted baseline bronchial tone. PLP appears to be expressed in the vagal ganglion in mice during the embryonic development [38]. The main function of this ganglion is afferent autonomic function, which is involved in visceral sensation and respiratory reflexes. If PLP is expressed in the Schwann cells supporting the PNS fibers or in the vagus ganglion of our mice, the duplication may be a direct cause of the lack of protective autonomic airway reactivity reported in the Plp1dup affected mice, but will not explain the lack of methacholine response in carrier mice. At this stage, PLP expression in these neumogastric preganglionic fibers, vagus ganglion, postganglionic parasympathetic autonomic fibers and sympathetic preganglionic fibers hasn’t been analyzed in these B6.129 mixed background mice. PLP is expressed in the Schwann cells supporting the sympathetic ganglion chain in mice during the embryonic development [38]; if PLP is also expressed in the Schwann cells supporting the SNS preganglionic fibers or sympathetic ganglion chain in our Plp1dup affected mice, the duplication may be one of the direct cause of the lack of bronchial constriction response in the Plp1dup affected mice.

We recognize the bronchodilation effect of ketamine, in this regard, no significant differences in RL are expected at baseline using this anesthetic [39]. During methacholine challenge and albuterol delivery, if any bronchodilator effect is elicited by the lower doses of ketamine used herein, this effect would be irrelevant because ketamine was administered to all groups of mice. We evaluated the bronchodilation response after the bronchoconstriction response in this report because, clinically, methacholine airway challenge is followed by bronchodilator administration [40]; bronchodilation was pursued also in this model to facilitate histological evaluation of the lung.

We also have shown that Plp1dup affected mice have lower levels of IL-6 in lung tissue than wild-type and carrier mice. IL-6 has been implicated not only in immunologic functions but also in the regenerative process as well as in the maintenance of neural homeostasis. Our Plp1dup affected mice were characterized by a lack of response to methacholine, lower levels of IL-6, and marked inflammation in the lung tissue, which allows for further research regarding any link between these findings. As demonstrated in this study, there was a cellular inflammatory component to the lung tissue of the Plp1dup affected mice characterized by patchy moderate inflammation composed of mostly neutrophils, lymphocytes, and histiocytes. In this regard, more pronounced infiltration of neutrophils and lymphocytes in lung tissue was associated with a lack of IL-6 levels in an interleukin-6-deficient mouse [41]. Although we only measured tissue IL-6 and TNF-α levels and did not conduct a comprehensive analysis to detect other cytokine levels, we speculate that IL-6 may play a role in the outcomes seen in the Plp1dup affected mice. This speculation emphasises the importance of further studies with a larger cohorts of mice, and with a more comprehensive cytokine analysis.

In summary, Plp1dup affected and carrier mice compared with wild-type mice were lacking airway reactivity to a methacholine challenge, but only Plp1dup affected mice exhibited low lung tissue levels of IL-6 and lung tissue inflammation within alveolar septa and septal thickening. These results may indicate a lack of protective autonomic airway reactivity with associated disruption of the lung homeostasis. The observed respiratory autonomic disequilibrium in Plp1dup affected mice suggests that respiratory autonomic regulatory mechanisms with an inflammatory component may contribute to respiratory involvement in PMD, but this conclusion requires further investigation with a larger cohort of mice before research might begin in patients. We believe that this Plp1dup animal translational model provides a susceptible genetic animal model for the study of pulmonary involvement in PMD and for testing therapeutic interventions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Nemours Histotechology and Biomolecular Research Core Laboratories (Carol Barone and Bobbie Boyce). Thanks also to Whitney Sample and Tariq Rahman from the Nemours Pediatric Engineering Research Laboratory for the assistance provided to the first author in developing the Respirod bands used in these mice. This study was funded by the Nemours Foundation (ER, GMH, THS), Nemours Research Programs (THS), NIH 5T32GM008562-17 (ER) pediatric pharmacology fellow funded by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) under the Best Pharmaceuticals for Children Act, NIH R01NS058978 (GMH), PMD Foundation (GMH), and NIH P20GM103464 (THS, GMH). None of the funding organizations were involved with the study design, collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, writing of the manuscript, or decision to submit for publication. Contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NICHD, NIH or the PMD Foundation.

ABBREVIATIONS

- CNS

central nervous system

- Cdyn

dynamic lung compliance

- Cst

static lung compliance

- IL

interleukin

- LBI

labored breathing index

- PMD

Pelizaeus-Merzbacher disease

- PLP

proteolipid protein

- PLP1

human proteolipid protein 1 gene

- Plp1

mouse proteolipid protein 1 gene

- Plp1dup

name of the mouse model that has a genomic duplication that includes Plp1

- PhRTB

phase relation during total breath

- PNS

parasympathetic nervous system

- RL

lung resistance

- SNS

sympathetic nervous system

- TNF-α

tumor necrosis factor–α

Footnotes

STATEMENT OF INTEREST

None of the authors has a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript. The authors have reported that no significant conflict of interest exists with any companies/organizations whose products or services may be discussed in this article.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- [1].Hodes ME, Pratt VM, Dlouhy SR. Genetics of Pelizaeus-Merzbacher disease. Dev Neurosci. 1993;15:383–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Hobson GM, Garbern JY. Pelizaeus-Merzbacher disease, Pelizaeus-Merzbacher-like disease 1, and related hypomyelinating disorders. Semin Neurol. 2012;32:62–7. DOI 10.1055/s-0032-1306388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Boison D, Büssow H, D’Urso D, Muller HW, Stoffel W. Adhesive properties of proteolipid protein are responsible for the compaction of CNS myelin sheaths. J Neurosci. 1995;15:5502–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Gudz TI, Schneider TE, Haas TA, Macklin WB. Myelin proteolipid protein forms a complex with integrins and may participate in integrin receptor signaling in oligodendrocytes. J Neurosci. 2002;22:7398–407. DOI 22/17/7398 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Gudz TI, Komuro H, Macklin WB. Glutamate stimulates oligodendrocyte progenitor migration mediated via an alphav integrin/myelin proteolipid protein complex. J Neurosci. 2006;26:2458–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Hobson GM, Kamholz J. PLP1-Related Disorders In: Pagon RAAM, Bird TD, et al. , editors. GeneReviews™ [Internet], Seattle: University of Washington; 1999. June 15 [Updated 2013 Feb 28] DOI NBK1182 [book accession] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Grossi S, Regis S, Biancheri R, Mort M, Lualdi S, Bertini E, et al. Molecular genetic analysis of the PLP1 gene in 38 families with PLP1-related disorders: identification and functional characterization of 11 novel PLP1 mutations. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2011;6:40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Barczykowski AL, Foss AH, Duffner PK, Yan L, Carter RL. Death rates in the U.S. due to Krabbe disease and related leukodystrophy and lysosomal storage diseases. Am J Med Genet A. 2012;158A:2835–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Sistermans EA, de Coo RF, De Wijs IJ, Van Oost BA. Duplication of the proteolipid protein gene is the major cause of Pelizaeus-Merzbacher disease. Neurology. 1998;50:1749–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Mimault C, Giraud G, Courtois V, Cailloux F, Boire JY, Dastugue B, et al. Proteolipoprotein gene analysis in 82 patients with sporadic Pelizaeus-Merzbacher Disease: duplications, the major cause of the disease, originate more frequently in male germ cells, but point mutations do not. The Clinical European Network on Brain Dysmyelinating Disease. Am J Hum Genet. 1999;65:360–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Simons M, Kramer EM, Macchi P, Rathke-Hartlieb S, Trotter J, Nave KA, et al. Overexpression of the myelin proteolipid protein leads to accumulation of cholesterol and proteolipid protein in endosomes/lysosomes: implications for Pelizaeus-Merzbacher disease. J Cell Biol. 2002;157:327–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Tatar CL, Appikatla S, Bessert DA, Paintlia AS, Singh I, Skoff RP. Increased Plp1 gene expression leads to massive microglial cell activation and inflammation throughout the brain. ASN Neuro. 2010;2:219–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Tobias JD. Anaesthetic considerations for the child with leukodystrophy. Can J Anaesth. 1992;39:394–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Hudson LD. Pelizaeus-Merzbacher disease and spastic paraplegia type 2: two faces of myelin loss from mutations in the same gene. J Child Neurol. 2003;18:616–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Clark K, Sakowski L, Sperle K, Banser L, Landel CP, Bessert DA, et al. Gait abnormalities and progressive myelin degeneration in a new murine model of Pelizaeus-Merzbacher disease with tandem genomic duplication. J Neurosci. 2013;33:11788–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Benarroch EE. Neurotransmitters In: Waldman SA, Terzic A, editors. Pharmacology and Therapeutics: Principles To Practice, Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier; Premium edition; 2009. p. 100–3. [Google Scholar]

- [17].Adams DJ, Biggs PJ, Cox T, Davies R, van der Weyden L, Jonkers J, et al. Mutagenic insertion and chromosome engineering resource (MICER). Nat Genet. 2004;36:867–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Lee JA, Inoue K, Cheung SW, Shaw CA, Stankiewicz P, Lupski JR. Role of genomic architecture in PLP1 duplication causing Pelizaeus-Merzbacher disease. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15:2250–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Woodward KJ, Cundall M, Sperle K, Sistermans EA, Ross M, Howell G, et al. Heterogeneous duplications in patients with Pelizaeus-Merzbacher disease suggest a mechanism of coupled homologous and nonhomologous recombination. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;77:966–87. DOI: 10.1086/498048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Flurkey K, Currer JM, Harrison DE. The mouse in aging research In: Fox JG, Davisson MT, Quimby FW, Barthold SW, Newcomer CE, Smith AL, editors. The Mouse in Biomedical Research, Burlington: Elsevier, 2nd Edition; 2007, p. 645. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Allen JL, Wolfson MR, McDowell K, Shaffer TH. Thoracoabdominal asynchrony in infants with airflow obstruction. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1990;141:337–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Readhead C, Schneider A, Griffiths I, Nave KA. Premature arrest of myelin formation in transgenic mice with increased proteolipid protein gene dosage. Neuron. 1994;12:583–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Huttemann M, Zhang Z, Mullins C, Bessert D, Lee I, Nave KA, et al. Different proteolipid protein mutants exhibit unique metabolic defects. ASN Neuro. 2009;1:165–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Sivan Y, Deakers TW, Newth CJ. Thoracoabdominal asynchrony in acute upper airway obstruction in small children. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1990;142:540–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Rodriguez ME, Mackenzie WG, Ditro C, Miller TL, Chidekel A, Shaffer TH. Skeletal dysplasias: evaluation with impulse oscillometry and thoracoabdominal motion analysis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2010;45:679–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Loring HS, de Troyer A, Grassino AE. Assesment of chest wall function (ATS/ERS Statement on respiratory muscle testing). Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166:583–4. DOI: 10.1164/rccm.166.4.518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Allen JL, Greenspan JS, Deoras KS, Keklikian E, Wolfson MR, Shaffer TH. Interaction between chest wall motion and lung mechanics in normal infants and infants with bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Pediatr Pulmonol. 1991;11:37–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Parreira VF, Bueno CJ, Franca DC, Vieira DS, Pereira DR, Britto RR. Breathing pattern and thoracoabdominal motion in healthy individuals: influence of age and sex. Rev Bras Fisioter.14:411–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Lymperopoulos A, Koch WJ. Autonomic Pharmacology In: Waldman SA, Terzic A, editors. Pharmacology and Therapeutics: Principles to Practice, Philadelphia: Saunders, Premium edition ed; 2009. p. 115–20. [Google Scholar]

- [30].Oldenburg PJ, Wyatt TA, Factor PH, Sisson JH. Alcohol feeding blocks methacholine-induced airway responsiveness in mice. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2009;296:L109–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Irvin CG, Bates JH. Measuring the lung function in the mouse: the challenge of size. Respir Res. 2003;4:4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Miller MJ, Haxhiu MA, Georgiadis P, Gudz TI, Kangas CD, Macklin WB. Proteolipid protein gene mutation induces altered ventilatory response to hypoxia in the myelin-deficient rat. J Neurosci. 2003;23:2265–73. DOI: 23/6/2265 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Slomin NF, Hamilton LH. Development and functional anatomy of the bronchopulmonary system In: Carson D, editor. Respiratory physiology, St. Louis: Mosby; 1987, p. 27–47. [Google Scholar]

- [34].Kennedy MC, Simpson WT. Human pharmacological and clinical studies on salbutamol: a specific beta-adrenergic bronchodilator. Br J Dis Chest. 1969;63:165–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Weston MC, Peachell PT. Regulation of human mast cell and basophil function by cAMP. Gen Pharmacol. 1998;31:715–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Su AI, Wiltshire T, Batalov S, Lapp H, Ching KA, Block D, et al. A gene atlas of the mouse and human protein-encoding transcriptomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:6062–7. Data last accessed (03/26/2014) at http://biogps.org/#goto=genereport&id=5354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Heras F, Ramos G, Castanedo M, Cortejoso A, Duque JL, Yuste MG. [Schwannoma of the intrathoracic vagus nerve]. Arch Bronconeumol. 1997;33:360–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Timsit SG, Bally-Cuif L, Colman DR, Zalc B. DM-20 mRNA is expressed during the embryonic development of the nervous system of the mouse. J Neurochem. 1992;58:1172–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Hirshman CA, Downes H, Farbood A, Bergman NA. Ketamine block of bronchospasm in experimental canine asthma. Br J Anaesth. 1979;51:713–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Beydon N, Davis SD, Lombardi E, Allen JL, Arets HG, Aurora P, et al. Bronchial responsiveness tests (ATS/ERS Statement on Pulmonary Function Testing in Preschool Children) An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: pulmonary function testing in preschool children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:1333–8. DOI: 10.1164/rccm.200605-642ST [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Qiu Z, Fujimura M, Kurashima K, Nakao S, Mukaida N. Enhanced airway inflammation and decreased subepithelial fibrosis in interleukin 6-deficient mice following chronic exposure to aerosolized antigen. Clin Exp Allergy. 2004;34:1321–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

WEB REFERENCES

- MIM#312080, Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man, last accessed (03/25/2014), available from http://omim.org/entry/312080

- MIM#300401, Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man, last accessed (03/25/2014), available from http://omim.org/entry/3004010