Abstract

The past few decades have seen the proliferation of new laws criminalizing certain transnational activities, from money laundering to corruption; from insider trading to trafficking in weapons and drugs. Human trafficking is one example. We argue criminalization of trafficking in persons has diffused in large part because of the way the issue has been framed: primarily as a problem of organized crime rather than predominantly an egregious human rights abuse. Framing human trafficking as an organized crime practice empowers states to confront cross border human movements viewed as potentially threatening. We show that the diffusion of criminalization is explained by road networks that reflect potential vulnerabilities to the diversion of transnational crime. We interpret our results as evidence of the importance of context and issue framing, which in turn affects perceptions of vulnerability to neighbors’ policy choices. In doing so, we unify diffusion studies of liberalization with the spread of prohibition regimes to explain the globalization of aspects of criminal law.

The globalization of markets has been accompanied by an interesting but understudied phenomenon: the diffusion of criminal law. As markets have become more open, states have taken action to define and prohibit specific kinds of transactions world-wide as criminal.1 We explore this phenomenon by focusing on a specific kind of prohibited activity: human trafficking, the criminalization of which has dramatically increased globally. Fewer than 10 percent of the states in the world had criminal statutes against trafficking in persons as recently as 2000. By 2015, roughly 75% of countries had criminalized all forms of trafficking in persons in their domestic law. Some people may assume there is no puzzle here: trafficking in persons is bad and needs to be stopped. Yet, it is curious that so many states came to their moral senses in the 2000s. The puzzle deepens as the debate over the law-enforcement approach to human trafficking intensifies.

The recent and dramatic increase in the criminalization of human trafficking can be analyzed as an instance of policy diffusion. In a highly interdependent world, states have been concerned to criminalize the same crimes as their neighbors in order to avoid the policy externalities associated with crime diversion. We argue, however, that this response is influenced by the framing of “trafficking in persons:” when exploitation has been framed as a rights violation, state responses have been modest and episodic. But when framed as a component of transnational criminal activity, the response has been swift and more or less global. The debates of the 1990s stoked perceptions of physical vulnerability to crime diversion, which in turn increases the likelihood that certain states will adopt the criminalization policies of their neighbors.

The criminalization of human trafficking has been driven in part by classic interdependence. Policy competition to repel negative externalities is an increasingly important aspect of world politics; indeed, it is the obverse of theories of liberalization that center on competing for capital and other legitimate business. Globalization creates markets – both for goods and services that states and their societies may want, but also for persons and activities they would prefer to exclude. Disrupting and diverting those markets creates policy externalities among interdependent states. When one state criminalizes human trafficking, its neighbors anticipate that trafficking will be diverted to their own jurisdictions, along with the associated violence, fraud, illegal immigration, and drug/weapons smuggling assumed to be associated with transnational organized crime. Viewed in this context, criminalization policies are essentially “contagious,” since the potential exists for enforcement in one country to divert transnational criminal activity elsewhere.

The article is organized as follows. The first section provides some background on the context of human trafficking and anti-trafficking efforts. It defines human trafficking and discusses historical efforts and contemporary circumstances that have brought this issue to the international agenda. The second section theorizes externalities as an important driver of policy diffusion. We explain in this section why a transnational crime frame heightens perceived interdependence vulnerabilities, and why this frame in turn predicts global spatial and temporal patterns of criminalization. The third section describes the data and model used to test the implications of this claim. The fourth section presents evidence of frame-dependent diffusion: a two part process that first involves the conscious effort to shape understanding of a phenomenon and only then adoption of “appropriate” policy. We show criminalization diffuses most strongly among neighbors that are connected by dense transborder highways, which is our proxy for perceived vulnerability to human trafficking externalities. Highways, we argue, are seen as the dominant physical conduits along which criminal networks ship human beings across borders. In the final section, we summarize the general lessons to draw from this research. Our major empirical contribution is to show that the infrastructures states have created to facilitate economic integration are also interpretable as conduits for negative policy externalities of neighboring states. Our theoretical contribution fuses two strands of the diffusion literature; one stressing competitive policy innovations, and the other stressing the importance of policy frames.

Framing Human Trafficking

Trafficking in persons is “the recruitment, transfer, harboring or receipt of persons, by means of the threat or use of force or other forms of coercion, of abduction, of fraud, of deception, of the abuse of power or of a position of vulnerability or of the giving or receiving of payments or benefits to achieve the consent of a person having control over another person, for the purpose of exploitation…”2 As this definition makes clear, human trafficking involves two critical elements: coercion or deception and exploitation. The nineteenth century slave trade was an obvious form of human trafficking, but once it was outlawed in much of the world, attention turned to what in early twentieth century Europe was referred to as the “white slave trade.” Opposition to prostitution motivated such agreements as the 1921 Convention for the Suppression of the Traffic in Women and Children, and the 1949 Convention for the Suppression of the Traffic in Persons and of the Exploitation of the Prostitution of Others. These were agreements that sought to protect especially vulnerable persons from sexual and other forms of exploitation. After almost four decades of complete international silence on human trafficking from the 1950s to1980s, the issue regained salience in the 1990s, both as a human rights threat and as part of a larger concern with controlling illicit activities across newly opened borders.

Human Rights as a Lens to Understand Human Trafficking

Any discussion of the exploitation of human beings raises important human rights issues. From the 1970s to the 1990s, international legal instruments guaranteeing human rights burgeoned in a range of areas, from torture prohibition, to women’s rights, to the rights of children.3 Rights advocacy groups influenced norms, laws, and practices worldwide.4 Rights movements during these years have been credited with creating difficult-to-resist spirals5 and boomerangs,6 which eventually contributed to holding governments more accountable for human rights violations than had ever been the case in the past. Indeed, some scholars have written about the latter decades of the 20th century in terms of a veritable “rights revolution.”7

This human rights legal revolution stimulated awareness of human trafficking and encouraged the view that trafficked persons are not simply “vulnerables” to be protected, but individuals with agency that must be respected. While rights framing accepts that women and children may be especially vulnerable, it draws attention to the full spectrum of human rights violations that trafficking in persons involves, from labor violations to violations of freedom of movement to inhumane treatment to (in the extreme) the right to life itself. Human rights advocates have emphasized the coercive aspects of trafficking in persons and even the slave-like conditions in which a good many trafficked individuals are held. In 1997, for example, the Special Rapporteur on violence against women chose to describe the plight of persons trafficked in terms of slavery and torture.8 Referencing “modern day slavery”9 is an especially graphic way to emphasize that trafficking in persons is a serious violation of human rights. Importantly, the human rights perspective holds state officials responsible for preventing such violations, while fully respecting the rights of individuals in every aspect of prevention and law enforcement.

Non-state actors have been among the most determined to frame trafficking in persons as a human rights abuse.10 Amnesty International,11 the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, and international agencies including UNICEF and the International Organization for Migration (IOM), have all emphasized the rights violations associated with trafficking in persons.12 These organizations have urged states to assure the protection of the rights of trafficked persons not to be detained, not to be forced to testify against their will, and to be allowed to remain in the destination country rather than be forcibly returned to their country of origin (though they seem to understand states have little incentive to do so).13

For a number of reasons, though, using rights to frame policy debates about human trafficking has not always been effective in securing significant policy innovations. The coalition for trafficked victim protection and human rights has historically been somewhat fragile.14 Political cleavages persist regarding whether “sex work” (prostitution) is an individual choice of profession or an inherently abusive activity from which individuals should be protected.15 These divisions are clear between conservative and liberal NGOs,16 and also characterize differences among states (the Netherlands legalized and Sweden criminalized prostitution).17

Furthermore, by the 1990s, many states were simply not eager to extend or to even acknowledge their human rights obligations beyond those in existing law, especially on behalf of (often foreign) victims. Even in a human rights forum such as the Third Committee of the United Nations General Assembly, states were reluctant to fully embrace human rights justifications for trafficking resolutions. One study shows that the more rights-focused human trafficking resolutions were in this forum, the fewer sponsors such resolutions attracted, while the opposite was the case for resolutions containing references to crime.18 Tellingly, the original 1994 resolution that became the 2000 Palermo Protocol shed five references to “human rights” and accumulated six additional references to “crim-” during UN debates in order to glean state support for adoption of the treaty draft.19 In this multilateral setting, the human rights perspective was important to the discussion, but likely did not persuade many states to adopt a stronger anti-trafficking stance. States were primed to fight transnational organized crime; many felt they were saturated with human rights commitments.

Transnational Crime as a Lens on Human Trafficking

Even more important than the rights revolution for framing the human trafficking debates of the 1990s were the massive changes implied by economic and political liberalization underway at the time. Globalization of markets increased transportation links across countries and made communication easier. International trade and investment boomed. But criminal rings also exploited reductions in transactions costs by trafficking illicit drugs, weapons, and stolen and pirated goods, in turn increasing the demand for laundered money. Meanwhile, the end of the Cold War and breakdown of the Soviet Union shifted attention of many western states away from traditional security concerns and toward threats associated with transnational organized crime.20 Across Eurasia, newly permeable borders allowed for an expansive flow of people and goods—licit and illicit—that challenged newly established and developing states’ ability to control their borders and stabilize their legal institutions. In short, the economic and political liberalization of the 1990s was also a boon for unwanted goods and services, from drugs to weapons to people.21

This critical context put transnational crime front and center and framed debates about the exploitation of migrating persons in the 1990s. Concerns about transnational crime were reflected in public discourse generally. For example, references to “transnational (organized) crime” in English language books exploded during the decade.

In terms of policy priorities, the United States government elevated transnational crime to the level of an official national security threat by the middle of the decade,22 and along with several other Western European allies, pushed to address human trafficking concerns internationally through the United Nations Office of Drugs and Crime (UNODC). Discussions in this forum led to the first ever comprehensive “international crime bill”—the Convention against Transnational Organized Crime (CTOC, adopted in 2000). Three additional protocols were attached, one devoted explicitly and exclusively to all forms of human trafficking. States could not ratify the new Protocol on trafficking without first ratifying the CTOC, which made clear the required buy- in of the framing of human trafficking as a problem linked to transnational organized crime.

Transnational Crime as a Frame for Policy Action

The threat of transnational organized crime to States’ interests provided the crucial framing for anti-human trafficking policy action, and helps explain the patterns of its diffusion around the world. We argue this framing appealed to states and encouraged them to take important policy initiatives. In contrast to a human rights frame, a transnational organized crime frame highlights traffickers as a challenge to state authority and societal well-being. This frame situates trafficking in persons firmly within the broader problem of criminal networks that transcend national borders, linking it to globalization, illicit labor migration,23 money laundering or migrant, weapons and drug smuggling networks. 24 The crime frame even encourages states to see trafficking in persons as a potential national security threat.25

This emphasis on threat can be used to justify action that empowers various arms of the state, from the police to border control agents to the military, while minimally obligating the state to respect individual rights or to protect (often foreign) victims.26 By contrast, the human rights emphasis obligates states to take measures to assure that individuals’ rights will be respected. Many more states are attracted to problem framing that empowers states than to frames that imply legal obligations.

Perhaps for this reason, many developing states embraced the transnational crime frame to address human trafficking. From Africa to the Americas, state officials have linked human trafficking to gun and drug trafficking, and to transnational organized crime generally;27 some use the issue to tout the need to bolster their authority to stem the social harms resulting from organized crime. Fighting trafficking in persons is also a useful way for state officials to ask for international resources to strengthen the state and its law enforcement institutions. As we demonstrate below, this framing of the problem also helps to explain the spatial and temporal diffusion of criminalization policies world-wide.

Theory: Human Trafficking and Policy Diffusion

The literature on policy diffusion provides a useful starting point for understanding frame- dependent policy diffusion. That literature generally posits interdependent policymaking (rather than a similar response to a common stimulus or shock), and advances specific mechanisms to account for the spread of policies around the world.28 Some diffusion scholars emphasize material structures and effects; others emphasize less tangible social structures that channel peer effects, the availability of models, and social tendencies to emulate admired exemplars.29 Mechanisms that stress material forms of coercion and economic competition exemplify the former; mechanisms that stress social emulation the latter.30

Our theoretical point of departure is that policy diffusion is frame-dependent. As a human rights issue, human trafficking policies are likely to reflect the value different societies place on human rights. Viewed as a component of transnational crime, human trafficking is more likely to diffuse along networks that reflect sensitivity to the policy externalities of neighboring countries. The first process is overwhelmingly normative and has been analyzed extensively in the human rights literature.31 The second process is likely to be reflected in material interdependencies between countries and is exacerbated by policy externalities. Two strands of the diffusion literature – one stressing competitive policy innovations and the other stressing normative processes – are potentially relevant to the diffusion of anti-trafficking policies around the world.

Diffusion via Policy externalities

Competitive pressure is one of the most pervasive explanations for policy diffusion, especially economic and regulatory policy. The logic is usually presented as straight forward: governments reduce tariffs, liberalize capital markets, adapt regulatory structures, privatize industries, and design tax and spending profiles with an eye to attracting international capital and business and improving efficiency. 32 Most researchers assume that governments want to attract business to their jurisdiction. A finding that various policies attractive to globally mobile firms or factors in one jurisdiction are correlated with adoption of that policy among competitors or networks of competitors is often taken as evidence consistent with this mechanism.33

The competition mechanism has an appealing intuitive logic, but few analysts question its core assumption about government beliefs and goals. For example, competition models do not easily accommodate the interesting asymmetries in policy adoption uncovered by Chang Kil Lee and David Strang in their analysis of the diffusion of government downsizing.34 They conclude that strong ideational commitments to neoclassical economics intervene to explain the tendency to compete with the downscaling of the public sector, but not its expansion. Nor does competition theory explain why regulatory races to the bottom are actually quite rare.35 Greenhill, Mosley and Prakash inject ethical considerations into what otherwise might have been a competitive international scramble to reduce wages and permit deteriorating working conditions.36 In their model, investment and trade networks are not only conduits for economic competition but potentially structures to be leveraged to protect human rights or clean air in these cases.

The competition dynamic does not directly explain the spread of prohibition regimes, but it does contain an important insight: policies implemented elsewhere can be expected potentially to divert business from one jurisdiction to another. An obverse dynamic is at work in many prohibition regimes: when a particular activity is criminalized in one regime, (unwanted) “business” will be diverted to a nearby jurisdiction where the transaction costs are lower. Not to criminalize a particular kind of economic transaction when other countries do renders the unregulated market more “business friendly.” In both competition and criminalization cases, diversion and policy externalities are key explanations for policy diffusion.

We argue that both diversion and policy externalities are central to the dynamics of criminalizing certain economic transactions. The idea behind criminalization, prosecution and punishment is to raise the ex post cost associated with a particular behavior so as to deter it ex ante.37 Of course, not all crime can be deterred at a reasonable cost,38 but empirical studies do suggest that some (possibly a substantial portion) of criminal activity can be deterred by raising the likelihood of some kind of sanction.39 Criminalization of human trafficking, for example, is thought by many state officials to raise transaction costs high enough to deter calculating criminal networks from transporting humans into or through a state’s territorial jurisdiction in the first place.40

One problem with an enforcement regime, however, is that while it raises the costs associated with the deceitful and exploitative transportation of human beings to the criminalizing jurisdiction, it may well result in the diversion of criminal activity, rather than its aggregate reduction. Negative policy externalities arise when law enforcement efforts in Country A re- channel criminal activities to or through nearby countries. Vigorous prosecution of sex trafficking in the United States, for example, may have led to an increase in sex tourism to other jurisdictions.41 Lessons may be drawn from drug trafficking: when the United States cracked down in Puerto Rico, drug traffickers descended on Haiti.42 The fluidity of transnational crime networks provides strategic incentives for states to harmonize policies with neighbors in order to avoid becoming the weak link in the law enforcement chain and thereby become a magnet for transnational criminal activity. Discourse that emphasizes transnational crime contributes to sensitivity of states to crime diversion effects of the enforcement regimes of their neighbors.

Viewed in this way, criminalization dynamics are analogous to competition dynamics discussed in the diffusion literature on trade and capital liberalization, except that criminal law is designed to repel “business” rather than to attract it, and to deter certain population movements rather than to encourage them.43 In the case of criminalization, the more vulnerable state officials perceive their jurisdiction to be to the diversion effects of the enforcement regime of others, the stronger the incentive will be to criminalize in one’s own jurisdiction. Moreover, this framing of the issue encourages decision-makers to interpret their physical environment as more or less resistant to policy spillovers that divert trafficking from neighbors.

Diffusion via social processes

The literature on policy diffusion through various processes under the heading of “socialization” is rich. Socialization is the process whereby norms and values of an organization or society are transferred from one member to another. These processes can include persuasion, or arguments deployed to change one’s mind or preferences (a cognitive process with a focus on internalization), or through processes such as shaming, back-patting, and the sending of similar social signals about appropriate values and behaviors (where behavioral change can be much more superficial). Socialization is a group process with consequences for individual behavior.

Many different mechanisms can account for socialization, including a desire for legitimacy or status, shared identities, mimicking of respected actors, and so on. Most theories of socialization emphasize that the group setting matters greatly: actors are only likely to assume the values or mimic the actions of others with whom they want to associate or whom they hold in high regard.44 Various social processes have been theorized to account for institutional and policy changes internationally. World society theorists, for example, emphasize that policymakers derive ideas about appropriate policies from the world around them. Given changing norms, and uncertainty about which policies are most effective, policymakers copy the policies they see experts promoting and leading countries embracing.45

Diffusion through socialization can take a number of forms. Many studies have found that the likelihood of adoption of a particular policy increases with the density of such adoptions world- or region-wide and have attributed such patterns to social or emulative processes, although such correlations are also consistent with the spread of norms, learning from better information,46 salience that works through domestic politics,47 and even competition.48 Scholars of human rights policies have generally identified NGOs as important actors for defining and diffusing policy norms,49 and intergovernmental organizations (IGOs) as important sites for the of state actors’ normative socialization.50 Empirical studies typically test various theories of persuasion, emulation and socialization using detailed time-series data on nations’ IGO memberships and participation in global conferences.51

Some social processes shade into social pressure, which can be exerted by one or a few exceptionally powerful actors. Social pressure from powerful actors or institutions may ignite policy diffusion (although there is some disagreement over whether pressure or coercion ought to be considered a “diffusion” mechanism at all).52 This mechanism requires that some powerful and/or respected actor has both the motive and the means to exert some form of pressure on policymakers around the world to adopt a favored policy, law or institutional form. Pressure can be active or passive; the latter may be experienced when a powerful actor creates a compelling focal point or is able unilaterally to change the policy context to such a degree that others have strong incentives to follow. The diffusion literature recognizes that coercion need not be exclusively material,53 and the socialization literature accommodates material forms of social pressure.54 Kelley and Simmons, for example, discuss “social pressure” from the United States in the form of annual Trafficking in Persons (TIP) reports and ratings.55 The point here is simply that there is a spectrum of ways in which powerful countries can influence other states’ choices, sparking a cascade of policy adoptions around the world.

Expectations and Framing:

How is it possible to make a theoretically informed interpretation of policy diffusion based primarily on negative externalities rather than values such as commitments to human rights? It is critical, we argue, to foreground an explanation that is consistent with the discourse of the times, and to develop empirical expectations that flow from that framing of the issue. In the context of the 1990s, the emphasis on transnational crime is important to diffusion patterns because it evokes concerns about negative transnational externalities that are weak or absent when considering human trafficking as primarily a normatively motivated human rights or victim protection issue. Focusing on the crime aspect of human trafficking links it with a host of external dangers associated with transnational organized crime rings, from drug smuggling to weapons trafficking to money laundering.56 Some accounts even link human trafficking and terrorism networks,57 a claim made in the United States’ own security assessments. Traffickers are said to corrupt local border officials,58 compromising the ability to control immigration and legitimate trade. Transnational crime networks are associated with the spread of violence, communicable diseases, and the spread of illicit labor practices with spillovers into licit markets.59 This issue frame is inherently attractive to states because combatting these externalities often justifies building state capacities while avoiding additional human rights obligations. Because trafficking numbers and associated activities are unavailable, it is impossible to quantify these externalities with any precision,60 but this is what makes issue framing important: the uncertainty and fluidity of reality on the ground.

The framing of the issue therefore matters for empirical investigation. If human trafficking policies are driven by social processes relating to human rights, we might expect emulation of the policies taken by members in rights-relevant organizations. Analyzing the problem of human trafficking through a transnational crime lens, however, focuses attention specifically on negative policy externalities in the form of crime diversion; in that case, we should expect diffusion patterns that reflect this sensitivity to criminalization by neighboring countries. For human trafficking, this suggests that policy diffusion should be sensitive to the transnational infrastructure connecting states. We derive the following hypotheses to test our claims:

H1: Criminalization is associated with physical vulnerability to the policy externalities of neighboring countries – a response to anticipated policy externalities consistent with the crime frame (“externalities”).

H2: Criminalization is associated with two social processes, one of which is more consistent with human rights framing, and the other of which is less frame-determined:

H2a: Socialization opportunities through shared memberships in human rights relevant international organizations – a social process more consistent with human rights framing (“shared memberships”).

H2b: Social pressure from powerful actors, especially, the United States – which is consistent with both the human rights and crime frames (“US pressure”).61

Methods and Data 62

Scholars of international affairs do not have particularly sharp methodological tools for distinguishing empirically between mechanisms of policy diffusion. The famous “s-curve” of cumulative policy adoptions associated with diffusion processes is consistent with everything from competitive pressures to Finnemore and Sikkink’s theory of norm life cycles generally.63 Our strategy is to take context and framing seriously, and ask: what unique patterns of policy diffusion should we expect if issue framing shapes policy adoption?

Dependent Variable: Criminalization in National Law

The dependent variable in this study is the criminalization of human trafficking in domestic law. Criminalization is a core element of both the US and EU approach. It is also consistent with both transnational crime fighting and human rights enforcement (as in the criminalization of torture), and so could plausible be explained by either lens. We define “criminalization” rather strictly for the tests reported below: our definition implies that a particular country’s laws comport with international treaty standards. Countries are coded as having criminalized if they have enacted specific anti-trafficking legislation, with broad coverage admitting of no important exceptions.64

One of the more innovative aspects of this research is the use of alternative dependent variables to test for generic patterns that may simply reflect homophily.65 Specifically, our argument about externalities should not apply where there are none (victim protection), where externalities involve different interdependencies (money laundering), or where externalities are not transnational (internal trafficking). These are placebo tests, and we expect a null result.

Major Explanatory Variables:

In order to test Hypothesis 1, which is most consistent with the transnational crime frame, we have collected data on the very conduits through which we expect externalities to flow in the case of human trafficking – roads connecting one country to another. In contrast to other forms of transnational crime such as money laundering or even trafficking in high value, light-weight drugs, human trafficking generally takes place through networks of surface transportation.66 Major roads are built to accommodate increased traffic suggesting both that borders with many crossings have high travel demands and most likely connect large cities (potential markets for trafficked labor) on either side. We used satellite images available in the USGS Global GIS database to create a worldwide dataset of major highways connecting each pair of contiguous countries.67 We then created a count of the number of roads which crossed each border between two countries to create a contiguity matrix. Recognizing that persons are trafficked by sea as well, countries which are connected by a passage over water of less than 150 miles are credited with an extra “road.”68 For each country, we weighted neighboring countries’ criminalization before the current year by the number of roads connecting neighbors’ territory with their own. For example, because of the number of roads in the region, Russia’s borders with Eastern Europe are given more weight than its border with Mongolia in predicting the diffusion of criminalization. If criminalization by Neighbors Policies Weighted by the Sum of Roads is positively correlated with criminalization in a given country, this suggests a diffusion mechanism aimed at avoiding crime diversion when neighbors criminalize.69 It is an outcome uniquely consistent with the transnational crime frame, and relatively independent of human rights concerns or social influence or pressure.

If framing human trafficking as a human rights issue has influenced policy diffusion via socialization, we might expect patterns of criminalization to follow the example of other members in organizations that have a human rights mission (Hypothesis 2A).70 The intuition is that human rights organizations constitute a peer network through which the rights violations of trafficked victims and appropriate policy responses are discussed. We test this idea by examining common memberships in human rights oriented IGOs using a list derived from Greenhill.71 Following Greenhill,72 we define an IGO with a human rights mandate as one that mentions human rights in its self-reported entry in the Union of International Associations’ Yearbook of International Organizations. There are 18 such organizations in total.73 As with the other diffusion measures we count the number of neighboring countries who have criminalized human trafficking by the previous year. Here we define “neighbors” as countries which share membership in at least one IGO with a human rights mandate. If discussions in these forums account for policy diffusion, we would expect a consistently positive relationship between Criminalization Among Members of Shared Human Rights Organizations and criminalization, which would be most consistent with the human rights frame.

Finally we consider social pressure from major actors, but particularly the United States as its domestic anti-trafficking law (the Trafficking Victims Protection Act or TVPA) both establishes the U.S. Department of State’s Office to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons (“TIP Office”) and mandates it to evaluate all countries’ anti-trafficking efforts, and to publish the information in an annual report. Countries’ efforts are grouped into four tiers (Tier 1, Tier 2, Tier 2 watch list, and Tier 3), with potential economic sanctions applied to countries deemed to be making insufficient efforts to confront human trafficking (hypothesis 2B). While this is potentially a crucial mechanism for policy diffusion, it accommodates both a human rights and a crime frame.74 We expect reputational concerns associated with the tier rankings to influence states’ decisions to criminalize human trafficking. 75 Where a country is ranked as making “no effort (Tier 3)”, or is placed on the “watch list” for not making sufficient effort to combat trafficking, we code that as subject to U.S. Pressure. Although the reports have been criticized on their methodology,76 several secondary sources document the extent to which low ratings do evoke embarrassment and sometimes policy change in the targeted country.77 If the pressure tactic is effective, we expect a low tier rating to lead to a tougher policy stance on criminalization in the following year, and would be consistent with either criminal or human rights frames.

Control Variables

While we are primarily interested in exploring the dynamics of diffusion related to the human rights and the transnational crime frame, there are a number of alternative explanations to take into account as well. One possibility is that we have over-emphasized the direct social pressures that may be in play and underemphasized structural dependencies that may influence policy diffusion.78 The extent of trade dependence a country has on the United States and/or the European Union certainly could increase sensitivity to these states’ preferences, since both of these entities have taken a strong stand against human trafficking. We therefore control for US Trade Share and EU Trade Share. We also collected data on U.S. aid dependence, US aid/GPD, and Use of IMF Credits, since the more a country depends on these forms of aid, the more vulnerable it may be to material coercion through the TVPA.

The literature on human trafficking suggests a series of plausible state-level factors that could also have a significant influence on a country’s decision to criminalize human trafficking. Since criminalization is a legal outcome, the general preference and capacity for a country to implement legal innovations could be a contributing factor. We control for a country’s reputation for adherence to the Rule of Law as measured by the World Bank’s rule of law scale, as well as for Ratification of the 2000 TIP Protocol, since it requires states parties to criminalize the practice. Since human trafficking is a (coerced and deceptive) form of immigration, we anticipate that countries’ immigration preferences might color their attitude toward criminalization of the former. It is therefore appropriate to include indicators expected to have a bearing on immigration policies, such as income category (Middle Income Categories, World Bank) and dependence on foreign Remittances/GDP. We control for developmental level and perhaps cultural attitudes toward labor with an indicator for the Prevalence of Child Labor. Since human trafficking is often presented and discussed as having a strong gendered element – many of the early UN resolutions addressing the problem related specifically to women and girls – it is possible that political systems that give women a stronger voice in governance are more likely to criminalize. We control for this possibility by including a measure of the Share of Women in Parliament.

One might suspect that there is no real diffusion dynamic at work here at all, but rather a broad consensus (perhaps the result of a previous norm cascade) that human trafficking is simply a human rights issue, and can be explained by a state’s and society’s human rights stance alone. This argument requires that we control for the human rights practices of states. We expect that the better a state’s human rights practices, the more likely it will be among the earliest to criminalize human trafficking.79 A correlation between a state’s Respect for Human Rights Score and criminalization would be most consistent with a rights framing of the issue, but does not directly address policy diffusion processes.

Finally we recognize a number of plausible “ties” could explain policy diffusion relating to human trafficking, and we test for a broad range of these. For example, states learn from the policies of their neighbors, although good data do not generally exist on the effect of criminalization on trafficking in persons.80 Nonetheless, states do share concerns, policy models and theories about what might work, so we control for some of the channels through which we might expect these learning processes to occur. One possibility is that states gather information most intensively from other states with which they trade.81 This can be the result of contact at the official or the private level. We therefore control for the policies of other countries weighted by their share in the total trade of a given country (Policy Weighted by Trade Partner). Models and information may also be carried in the regional press. Using a database of all press articles from LexisNexis that mention human trafficking or a cognate phrase and mention a specific state’s name, we extract only those reports in the Regional Press Stories on Human Trafficking to see if they influence the probability of criminalization – or wash out the effects of the physical environment connected with understandings of vulnerability to crime diversion.

Another possibility is that states look well beyond their region to the set of countries that represent their developmental level for appropriate responses to human trafficking.82 We use the World Bank income categories, and code for the proportion of countries criminalizing within a given country’s Criminalization Density within Developmental Level. A country’s civilizational group might constitute an alternative peer group, since it may be that the values and purposes that guide attitudes toward criminalization of human trafficking are culturally shared (Criminalization Density within Civilizational Group). Finally, since we are examining the diffusion of law, it may be that policymakers look to countries that share their legal heritage (common law versus civil law traditions, for example) for models. Therefore, we control for Criminalization Density among Legal Family. All of these effects are lagged one period. Many of these “peer effect” measures are highly correlated, so in the tests that follow we will examine them one by one against our theory of negative policy externalities.83

Method of Analysis: Event History Models

We use a statistical method that focuses on the spell of time until the domestic criminalization of human trafficking occurs. Specifically we employ a Cox proportional hazard model (a kind of survival model) to examine the effects of a number of continuous and categorical predictors, using time varying and non-time varying covariates. Widely used in epidemiological studies that seek to understand factors that affect mortality rates, this technique can be used analogously to test for the conditions associated with a greater “risk” of these policy changes occurring (given that they have not yet occurred). Due to the potentially complex functional forms of the relationships, we fit the model using semi-parametric splines on continuous independent variables of interest.84 The Cox model leaves the baseline hazard unspecified and thus we make no assumption about whether the rates of criminalization inherently accelerate or decelerate with time. The null hypothesis is that the proportional hazard rate for any given explanatory variable is 1 (it has no effect on the baseline hazard rate). We use interval-censoring to allow for time varying covariates; consequently, the unit of analysis is the country-year. The analysis begins in 1991 (before that date, data are not widely available) and ends in 2009.85

Findings

Our central finding is that diffusion of criminalization is most consistently explained by a frame that emphasizes transnational organized crime. The results summarized in Table 1 suggest concerns about diversion of criminal networks are likely a major driver of the diffusion of the criminalization approach to human trafficking. Neighbor’s Policy Weighted by Sum of Roads 86 has a profound effect on a state’s likelihood of criminalizing. On average, each additional road connecting two jurisdictions raises the probability that a country will criminalize human trafficking in response to their neighbor’s policy by between 1 and 4%. This specific pattern supports a theory of law diffusion related to the anticipated externalities arising from criminalization in jurisdictions from which it is easiest to divert the activities of criminal trafficking networks, e.g., those connected by roads. Modern transportation networks that previously have been viewed as harbingers of regional integration, globalization or modernization are also interpretable as conduits for transnational networks of human traffickers. In particular, they potentially make a country more vulnerable to crime diversion from neighbors who themselves decide to crack down on human trafficking.

TABLE 1.

Externalities and other Influences on the Rate of Criminalization in National Law (Hazard ratios)

| Model 1 Base | Model 2 Material Coercion | Model 3 Develop. controls | Model 4 Women’s influence | Model 5 Human Rights Practices | Model 6 Human Rights Diffusion | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vulnerability to the diversion of externalities (Neighbor’s Policy Weighted by Sum of Roads) (s) | 1.02*# | 1.02*# | 1.02*# | 1.02*# | 1.03*# | 1.02* |

| U.S. pressure | 2.18* | 2.34* | 1.87* | 2.01* | 2.33* | 2.13* |

| Rule of Law (s) | 1.51*# | 1.86*# | 0.98# | .97# | 1.00# | 1.51*# |

| Ratification of 2000 TIP Protocol | 1.72* | 1.80* | 1.80* | 1.72* | 1.52* | 1.55* |

| US Aid/GDP (s) | -- | 1.08*# | -- | -- | ||

| Use of IMF Credits | -- | 9.45* | -- | -- | ||

| US Trade Share(s) | -- | 0.08*# | -- | -- | ||

| EU Trade Share (s) | -- | 0.88# | -- | -- | ||

| Prevalence of Child Labor (s) | -- | -- | 0.97* | 0.97* | ||

| Middle Income Countries | -- | -- | 0.46* | 0.42* | ||

| Remittances/GDP (s) | -- | -- | 0.99# | -- | ||

| Share of Women in Parliament (s) | -- | -- | -- | 1.02# | ||

| Respect for Human Rights Score | -- | -- | -- | -- | 1.33*# | |

| Criminalization among Members of Shared Human Rights Organizations | 1.00# |

Note: Results are from a Cox-Proportional Hazards Model. Variable names followed by (s) are fit using smoothing splines. The reported values are either the hazard ratios, or the best linear approximation to the hazard ratios. There are approximately 3000 observations in each model (and around 78 events), exact numbers vary by imputation. See Appendix for more details and a more detailed presentation of results. All results based on two-tailed tests.

= linear effect significant at the .05 level.

= non-linear effect significant at the .05 level.

Figure 3, derived from Table 1, Model 1,87 illustrates the relationship between criminalization and road connectivity using 95% confidence intervals. Initially the marginal effect of each road with a neighbor who has criminalized human trafficking is very close to linear, increasing the probability of criminalization by approximately 65% when moving from 0 to 10 roads. After about 20 roads, the marginal effect of each additional road appears to decline. This is consistent with anticipated externalities, which are likely to demonstrate similarly decreasing marginal effects after a given threshold.

FIGURE 3. The Hazard Ratio Associated with the Number of Roads to Neighbors Who Have Criminalized.

Note: The y-axis shows the hazard ratio. Units are of the hazard ratio but they are plotted on the log-scale. Shaded area represents the 95% confidence interval.

That said, all of the models in Table 1 indicate a role for certain kinds of socialization, particularly U.S. pressure (Hypothesis 2B). Placement of a country in the third tier (“no effort”) or “watch list” categories in the annual U.S. State Department Trafficking in Persons report approximately doubles, on average, the chances that the country will criminalize human trafficking in the following year, which comports well with recent research.88 All models also support the two primary control variables: Ratification of the 2000 TIP Protocol and Rule of Law. Ratification increased the probability of subsequently criminalizing human trafficking by about 80%, as required by Article V of the Protocol. A country’s reputation for the Rule of Law is nonlinear and positively correlated with criminalization as well.89

Model 2 further probes various forms of economic pressure to criminalize. Given that the U.S. is authorized by the TVPA to use its influence to block IMF loans if countries make extremely weak efforts to control human trafficking, it is not surprising that when states rely on IMF funding, they are much more likely to implement policies the U.S. and other creditors favor. At 9.45, the estimated hazard ratio for Use of IMF Credits is quite large. On the other hand, US Trade/Total Trade is negatively correlated with criminalization policy, with the range from 0 to 40% being particularly negative. EU Trade/Total Trade is basically flat, although also slightly negative along that range. This finding is consistent with the literature that emphasizes the difficulties of using trade as a sanctioning weapon for human rights or other purposes. It also supports the intended purpose of U.S. legislation: to pressure countries to criminalize and to use the threat of reducing or eliminating U.S. aid (but not trade) to do so.

We expected a country’s developmental level to have some influence on criminalization (Model 3), but found that these effects are not linear. Middle Income Countries are about 53% less likely to criminalize human trafficking than are low income and high income countries. This could reflect the tendency for wealthy countries to be trafficking destinations, and therefore more vulnerable to externalities, while the poorer countries may be offered some technical assistance for cooperative policies. Both Prevalence of Child Labor and Remittances/GDP have generally negative effects, with the largest effects being at extremely high levels of the variable. For example, at the highest levels of child labor, a country is around 20 times less likely to criminalize than a country with virtually no child labor.

Model 4 controls for an important domestic political factor: percentage of parliamentary seats held by women. Share of Women in Parliament seems to have had a strong (and, again, non-linear) effect on criminalization. A country with no women in parliament is about 10 times less likely to criminalize than the median country (which has about 10% women in parliament), while a country nearing 50% of women in parliament is around 7 times more likely to criminalize than the median. This finding supports expectations that the representation of women’s interests in policy-making institutions might positively impact legislation in what is often thought to be a highly gendered issue area. Model 5 shows that a state’s human rights practices also have an important role to play: Respect for Human Rights Score, as measured by Fariss’s physical integrity index, is associated with a higher probability of criminalization than are poor human rights. The inclusion of these control variables has minimal to no impact on the evidence for the importance of externalities; indeed the effect of interdependence as measured by transnational road connections is remarkably stable across every model in Table 1.

Finally, we test for our alternative hypothesis on social processes attendant to human rights framing. The evidence is not especially clear (Model 6). Criminalization among Members of Shared Human Rights Organizations may have some purchase on human trafficking policies among states in modestly dense human rights networks, but states in dense and sparse networks are if anything, negatively sensitive to the trafficking policies of co-members.90 In fact, the average linear effect of criminalization within human rights organizations to which a state belongs is close to zero. Certainly, this does not resoundingly confirm hypothesis 2A, though we cannot definitively reject it, either. However, the effect of interdependence by road connections remains strong, positive, and with both linear and nonlinear effects, even when we control for the possibility of diffusion consistent with human rights framing as clearly illustrated in Figure 3.

Robustness tests: Alternative Proximity Measures

Our argument about the importance of framing and perceived externalities in explaining the globalization of law in the case of human trafficking rests heavily on the finding that policy diffuses along road connections among states. Scholars in other theoretical traditions have used various measures of “proximity” to explain policy diffusion by mechanisms that are distinct from – and even contrary to – the externality argument developed here. In particular, many alternative diffusion stories also depend on co-location in space. Are alternative mechanisms as or more plausible than our framing account of negative policy externalities?

Table 2 shows that, more likely than not, policy externalities as captured by road connectivity account for this special responsiveness to the policies of near neighbors. Model 1 shows that the roads are not just picking up trading relationships that could be expected to transmit ideas from one national market to another. The roads indicator is independently significant even though there is some evidence of diffusion via trade connections. Similarly, Model 2 suggests that the roads indicator is simply not capturing the general flow of ideas from nearby countries: the number of regional news articles on human trafficking would be a natural conduit for such ideas,91 and when they are controlled for, Regional Press Stories on Human Trafficking itself is not significant, but road density remains strongly so. The density of criminalization among various “reference groups” probably does help to explain the spread of human trafficking criminalization. Civilizational emulation has the strongest positive results.

TABLE 2.

Robustness of Diffusion via Roads: Other “Proximity” Measures (Hazard ratios)

| Model 1 Trade diffusion | Model 2 Regional news coverage | Model 3 Develop- mental emulation | Model 4 Civiliza- tional emulation | Model 5 Emulation among legal families | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vulnerability to externalities (Neighbor’s Policy Weighted by Sum of Roads) (s) | 1.02*# | 1.03*# | 1.03*# | 1.02*# | 1.03*# |

| U.S. Pressure | 1.33 | 2.38* | 2.27* | 2.29* | 2.25* |

| Rule of Law (s) | 1.74*# | 1.44*# | 1.50*# | 1.22# | 1.48*# |

| Policy Weighted by Trade Partners (s) | 1.34# | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Regional Press Stories on Human Trafficking (s) | -- | 0.96# | -- | -- | -- |

| Criminalization Density within Developmental Level (s) | -- | -- | 0.98# | -- | -- |

| Criminalization Density among Civilizational Group (s) | -- | -- | -- | 1.04*# | -- |

| Criminalization Density among Legal Family (s) | -- | -- | -- | -- | 1.01# |

Note: Results are from a Cox-Proportional Hazards Model. Variable names followed by (s) are fit using smoothing splines. The reported values are either the hazard ratios, or the best linear approximation to the hazard ratios. All results based on two-tailed tests.

= linear effect significant at the .05 level.

= non-linear effect significant at the .05 level.

Criminalization in one’s civilizational group contributes an increased probability of approximately 50% across the first five criminalizing countries, after which the effect flattens off considerably.92 The density of criminalization among countries from the same legal family that have criminalized is also positively related to criminalization, although the magnitude of the effect is smaller. Somewhat surprisingly, however, there is no evidence of emulation of the policies of countries from within one’s own income level. If anything, the inverse might be the case. In all of these models, however, the density of roads contributes at least as strongly and independently to the likelihood of criminalization – a spatial relationship consistent with concerns about crime diversion when neighbors crack down on human trafficking rings.93

Robustness Tests: Alternative Dependent Variables

Rather than pile highly correlated explanatory variables upon one another, we can gain greater leverage on the plausibility of the externalities argument by thinking about the conditions under which we would expect it to hold; that is, we look at the effect of road density on different dependent variables. In this set up, roads are essentially a placebo; we would not expect them to affect outcomes. If our model explains policies where there are no externalities, or it explains policies that address negative externalities that do not make use of roads, there is a risk that our measure of connectivity is nothing more than another ambiguous proximity measure that explains “everything,” and therefore nothing.

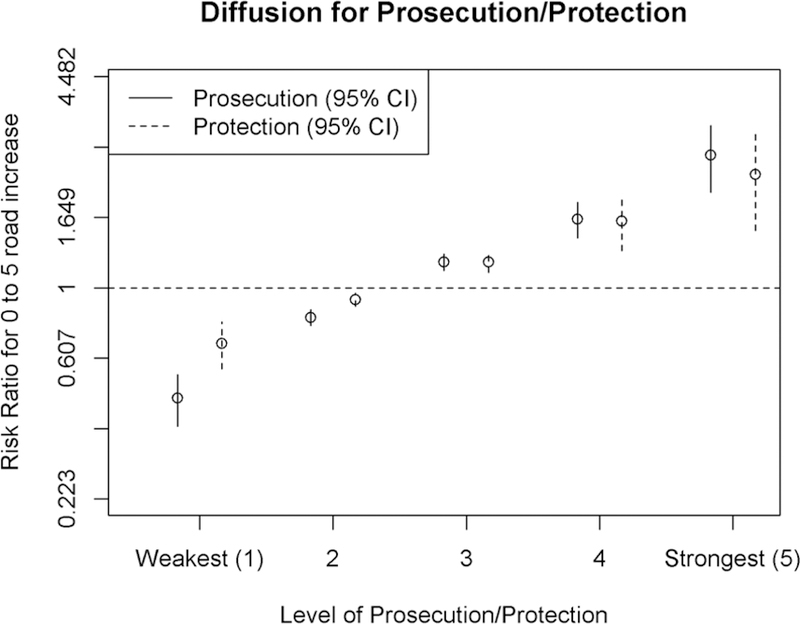

Table 3 shows what roads do and do not explain. First, compare the impact of roads where policy externalities are strong (prosecution of alleged traffickers) and where they are weak (victim protection).94 The former can be expected to disrupt transnational networks and potentially to reduce externalities. The latter concentrates on treating the victims of trafficking properly; that is, by providing them medical care, helping them retrieve proper documentation, and returning and reintegrating them into their home society. These may be good and humane policies, but they do not disrupt trafficking networks and hence are not likely to impact perceptions of the diversion of crime along transnational roadways. We would not expect the density of transnational roads to explain the diffusion of victim protection policies from one jurisdiction to another. Model 1 uses an ordinal probit model to compare the ability of the same battery of explanatory variables to explain these two subsets of human trafficking policies and shows the coefficient on protection is about two-thirds the size of that for prosecution. This suggests that roads are likely much more important for the diffusion of prosecution policies than they are for victim protection policies. We visualize this finding in Figure 4 by considering the risk ratios associated with a move from 0 to 5 neighbors who have criminalized. Clearly, for prosecution, the probability of a strong prosecutorial effort is greatest where road connections are more numerous – a result consistent with concerns about policy externalities. The relationship is different for victim protection policies, which tend to be stronger where roads are fewer. The bottom line is that road connections explain policy vectors involving externalities, but not anti- trafficking policies where externalities are absent.

TABLE 3.

Robustness of Diffusion via Roads: Other Outcomes

| Model 1: Ordinal Probit: Comparing policies within human trafficking issue area | Model 2: Hazard Model Comparing criminalization policies across crime sectors | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DV: prosecution | DV: victim protection | DV: Criminalization of human trafficking | DV: Criminalization of money laundering | |

| Vulnerability to the diversion of externalities (Neighbor’s policy weighted by Sum of Roads) (s) | 0.24* | 0.15* | 1.03*# | 1.00# |

| Rule of Law (s) | 0.29* | 0.16* | 1.55*# | .95# |

| Ratification of Human Rights Treaties | 0.06* | 0.08* | -- | -- |

| Share of Women in Parliament | 0.01* | 0.01* | -- | -- |

| HT Press Stories Mentioning Crime | -0.06 | -.08 | -- | -- |

| HT Press Stories Mentioning Victims | 0.19* | .15* | -- | -- |

| Developmental Level (s) | -- | -- | 0.91 | 1.11 |

Notes: Model 1 is estimated using an ordinal probit and coefficients are reported with hypothesis test at the .05 level. The spatial variable is fit as the inverse hyperbolic sine function of roads in this model. Data distinguishing victim protection policies from prosecution policies in Model 1 were generously supplied by Cho, Dreher, and Neumayer (2014). In Model 2, the spatial variable is fit using the cox-proportional hazards model again and all variables have smoothing splines.

There are approximately 1500 observations in each model; exact numbers vary by imputation. All results based on two-tailed tests.

FIGURE 4. Risk Ratios Associated with a Change from 0 to 5 Roads to Neighbors Who Have Criminalized (note that the y-axis is plotted on the log scale).

Note: Each additional road has a much stronger effect on prosecution than protection as evidenced by the much lower probability of being in the lower categories and the much higher probability of being in the highest category.

Model 2 addresses the plausibility of roads as conduits in the human trafficking case by presenting evidence in an area where negative externalities are not road-dependent: the criminalization of money laundering. Money laundering tends to be electronic; it does not depend on physical roads connecting jurisdictions. A comparison of the hazard ratios under Model 2 shows that a road has absolutely no effect on the probability of emulating a neighbor’s policies criminalizing money laundering, while an additional road raises the likelihood of emulating criminalization of human trafficking by about 3% on average. Figure 5 visualizes the hazard ratios between these two comparable models on the same scale. The effect is powerful when you realize it is holding constant all of the other emulation or ideational effects that we commonly see in the sociological literature on policy diffusion.

FIGURE 5. Roads to Neighbors Who Have Criminalized Have a Much Stronger Influence on Human Trafficking than Money Laundering in Comparable Models.

Note: The figure depicts hazard ratios with 95% confidence regions.

Finally, we probe the plausibility of the externalities argument by subsampling our data and testing for the conditions under which we would expect the effects to be most acute. The perceived externalities associated with human trafficking are likely to be most significant, it is plausible to assume, in countries through which traffickers are most likely to pass (transit countries) and countries in which trafficked individuals enter and ultimately are exploited (destination countries). When human trafficking is framed as linked to transnational crime, transit and destination countries should be most sensitive to the policies adopted by their neighbors. Countries with serious internal trafficking problems may have motives – including human rights motives – to crack down on transnational criminal networks involved in trafficking, but if we are correct about the importance of externalities their policies should not necessarily be sensitive to that of their neighbors’.

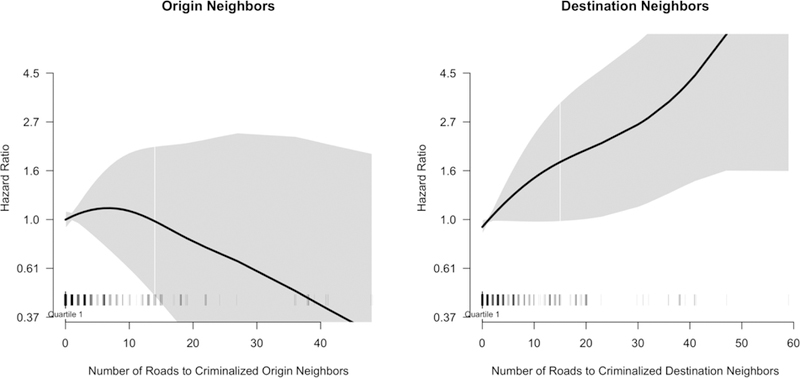

Table 4 tests for the importance of externalities using nuanced subcategories of neighbor countries, grouped by whether they are primarily a country of destination, origin, or transit, or impacted by internal trafficking. The results fit a theory of the importance of policy externalities in explaining the willingness to criminalize human trafficking. Despite the fact that the categories are noisy, it is clear that transit countries are much more strongly and consistently influenced by the policies of their neighbors than are countries that are not important transit routes. While the linear hazard ratios are the same in each sub-category, the initial effects are much stronger in transit and destination countries, as visualized in Figure 6 on the same scale. Note particularly the steep line between 0 and 10 road connections with neighbors who have criminalized human trafficking for transit countries. Road connections have their strongest effects in transit countries (and their weakest effects in countries with internal trafficking problems), consistent with our interpretation that perceived negative externalities, heightened by the salience of the transnational crime frame from the 1990s, is an important driver of the diffusion of human trafficking policies.

TABLE 4.

Effects of Externalities on Probability of Domestic Criminalization of Human Trafficking, by Exposure Category (Hazard Ratios)

| Model 1 Destination countries | Model 2 Origin countries | Model 3 Transit countries | Model 4 Internal Trafficking countries | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vulnerability to the diversion of externalities (Neighbor’s policy weighted by Sum of Roads) (s) | 1.02*# | 1.03# | 1.03*# | 1.01# |

| US pressure | 1.83 | 2.32* | 1.49 | 2.51* |

| Rule of law (s) | 1.67*# | 1.21# | 1.31# | 1.50# |

| Ratification of 2000 protocol | 1.54* | 1.46 | 1.58* | 1.36 |

Note: Results are from a Cox-Proportional Hazards Model. Variable names followed by (s) are fit using smoothing splines. The reported values are either the hazard ratios, or the best linear approximation to the hazard ratios. All results based on two-tailed tests.

= linear effect significant at the .05 level.

= non-linear effect significant at the .05 level.

FIGURE 6. Hazard Ratios Visualized on the Same Scale Across two Sub-group Types of Countries.

Note: The impact is much stronger for transit countries (and origin and destination, not shown) than for internal trafficking where the positive change is only statistically significant at extremely high numbers of roads to neighbors who have criminalized.

A similar test can be done distinguishing the nature of one’s neighbors’ position in a network by trafficking type. There is no powerful reason for countries to imitate the policies of a neighboring state that is primarily a country of origin, since such a policy should have at most a weak crime diversion impact. Cracking down at the source is more likely to reduce trafficking than to divert it. If a neighbor who is a destination country criminalizes, diversion is much more likely. Once again, this is the pattern most consistent with the data: roads matter much more when one’s neighbor is a destination. As a theory of externalities would expect, they are much flatter when a neighbor is primarily a source for trafficked labor (see Figure 7).

FIGURE 7. Hazard Ratios Visualized on the Same Scale Across two Sub-group Types of Neighbor Countries.

Note: The impact on a country is strong and positive when the neighbor is a destination. There is essentially no effect to road connections when a neighboring country of origin criminalizes.

Conclusions

Globalization has had a profound effect on a wide range of policies over the past several decades. Liberalization of trade, investment and capital account policies have been usefully theorized as competition for capital among states using policy innovations to bid for international business. A similar dynamic appears to be at work in the spread of policies meant to deter certain kinds of “business.” As transaction costs have fallen and markets have liberalized, opportunities to profit from illicit activities have grown as well. The idea that transnational organized crime is a dangerous global phenomenon with serious social and security consequences became one of the central themes of the 1990s.

Once we understand the power and the pervasiveness of the transnational crime frame in global discussions, it becomes clearer why certain states have adopted the prosecutorial approach to human trafficking: they come to see themselves in varying degrees as vulnerable to crime diversion and the policy choices of their neighbors. Primed in the 1990s by transnational crime discourse, governments have anticipated that neighborly criminalization will divert some human trafficking business to and through their own jurisdiction. Whether or not trafficking actually does increase the risks of transnational drug and weapons trafficking, money laundering, violence, illegal migration and document forgery cannot be proved definitively with the available data, especially since no one can currently document a clear global relationship nor even reasonably estimate the number of persons trafficked worldwide.95 But when human trafficking is framed as one way criminal rings make profits, as has been the case for the past two decades, governments are much more likely to take a prosecutorial approach to the exploitative movement of human beings across their borders than when victims, moral purity and human rights dominate the discussion, as they did for most of the twentieth century.

Our point is not as obvious as claiming that a crime frame leads to criminalization. Criminalization itself does not depend on the existence of externalities and interdependence. After all, states have (less widely, less enthusiastically, and with more foot-dragging) criminalized human rights violations such as torture. Our argument is rather that the crime frame provokes much stronger, swifter, and more global action than frames that emphasize victim protection or human rights. Despite the fact that the human rights frame has been “available” since the late 1940s and especially since the 1970s,96 states dealt only episodically with human trafficking throughout most of the twentieth century. The specter of transnational crime provoked action like never before in the 1990s. Moreover, it provoked very specific geographical patterns of criminalization along specific infrastructural routes that reflect potential for trafficking interdependency. We stress that criminalization is not inevitable: there remains significant contestation about whether human trafficking – opposed by many people on moral grounds – is best approached through a regime of relentless law enforcement. Indeed, a significant segment of the international community has urged a more rights- or victim-oriented approach.97 The best way to address such trafficking has, in fact, been hotly contested.

This is why issue framing is so important. Sense-making is central to the contestation among states and civil society actors that precedes the development of formal rules and practices.98 Social movement scholars in particular stress the conscious strategic efforts by groups of people to fashion shared understandings of the world and of themselves that legitimate and motivate collective action.99 These intensely political processes, the micro-foundations of which are increasingly well-understood,100 contribute to the “settlement” of norms and they facilitate the diffusion of “appropriate” policy globally.

Our key finding is that once trafficking is framed as a profit center for other transnational crimes, governments emulate their neighbors’ anti-trafficking criminal statutes, conditional on their exposure to externalities. Roads are natural conduits for human trafficking and other criminal activities about which many governments are so concerned. The finding that infrastructure matters was robust to inclusion of a broad range of other diffusion variables, and even to the inclusion of catch-all “regional effects.” This is an important addition to explanations that emphasize western leadership, and U.S. pressure via TIP Report ratings in particular. The U.S. government – with the cooperation of a broad coalition of states – has undoubtedly fueled policy diffusion by contributing to a problem definition that encourages states to respond not only to U.S. pressure but to policy changes of neighbors as well. To clarify our contribution even further, we are not saying that human rights concerns have played no role in the diffusion of human trafficking policies. The evidence is clear that states with better rights practices are much more likely to criminalize human trafficking than are those who oppress. But in the absence of its linkage to transnational organized crime, human trafficking might have remained a silent problem in the 1990s and 2000s – one quite unlikely to have been acted upon by a great many states around the world.

Moreover, it is crucial to note that roads plausibly explain the diffusion of law enforcement policies, but they do not explain everything. Externalities explain efforts to prosecute human traffickers, but they do not explain as well policies to protect and reintegrate victims into their home societies; they do not explain crimes that occur electronically, such as money laundering, and they have little if any purchase on the policies of internal trafficking states. And consistent with a theory of policy externalities, diffusion is much more likely when a destination or transit country criminalizes than when a source country does so. This combination of tests should raise confidence that policy externalities and sensitivities result from very concrete interdependencies, and not just the general transmission of models and ideas. The primary takeaway is that issue framing interacts with perceived physical vulnerability to explain very specific spatial patterns of adoption.

These findings should challenge researchers of global diffusion to connect prevalent frames with specific forms of transnational interdependence. To be plausible, diffusion models must be much more contextual than they have been in the past. New research in areas from tax policies to trade and investment now recognize that “spatio-temporal context” is crucial for understanding competitive policy dynamics.101 More broadly, this research suggests that intersubjective ideational theories and conditionally rational problem solving are both interlocking pieces of a theory of human action. These explanations must be combined to arrive at a better understanding of why laws, policies and institutional forms gain wide global adherence.

FIGURE 1. Cumulative number of states that have criminalized human trafficking.

Source: Authors’ calculations based on U.S. State Department TIP Reports and UNODC criminalization data.

FIGURE 2.

Density of written attention to “transnational (organized) crime” as represented by Google Ngrams, https://books.google.com/ngrams.

Footnotes

From Article I.3(a) to the Protocol to Prevent, Suppress, and Punish Trafficking in Persons, especially Women and Children (hereinafter, the “Palermo Protocol”) which is attached to the Transnational Organized Crime Convention. This treaty obligates state parties to criminalize trafficking in persons in their national statutes Article V), and to protect victims’ privacy and identity “in appropriate cases and to the extent possible under domestic law” (Part II, Art 6(1); see UNODC (2009) Legislative Guide for the Trafficking in Persons Protocol available at http://www.unodc.org/documents/human-trafficking/Framework_for_Action_TIP.pdf, accessed 1 December 2013).

See Radhika Coomaraswamy, Report of the Special Rapporteur on Violence against Women, its Causes and Consequences, E/CN.4/1997/47, 12 February 1997. Available at: http://www.unhchr.ch/Huridocda/Huridoca.nsf/0/043c76f98a706362802566b1005e9219?Opendocument (accessed 16 January 2014).

For evidence see Lloyd and Simmons 2015.

Amnesty International’s webpage on trafficking. Available at: http://www.amnestyusa.org/violence-against-women/end-human-trafficking/page.do?id=1108428 (accessed 15 June 2010).

Gallagher 2001. See also Special Rapporteur on Violence against Women, 1997.

For a history of the politics of consensus formation, see Chuang 2005–2006. characterizing the anti-trafficking coalition in the 1990s as “fragile.”

As Asif Efrat (2012.) has noted, the decades of market liberalization were accompanied very shortly by the counter-trend of the regulation – even the banning – of trade in newly illicit goods across borders.

Former U.S. President Bill Clinton first raised the concept of transnational organized crime as a global security threat in 1995, and the major European countries endorsed his analysis at a G8 meeting in Lyon shortly thereafter. See Van Dijk 2011. Transnational organized crime appeared in the U.S. national security threat assessment for the first time in 1996. See http://nssarchive.us/NSSR/1996.pdf.

Critical theorists make much of the claim that “globalization is increasingly serving as a means by which national criminal justice systems seek to augment their resources and (re)legitimate themselves,” and some view human trafficking policy as one example D. Nelken, quoted in Lee 2011. p. 7.

Guinea-Bissau officials have claimed the “trafficking of women had been integrated into all forms of organized crime,” and called for “strict enforcement measures.” See GA/SHC/3368 16th Meeting (PM) 28 October 1996. Available at: http://www.un.org/News/Press/docs/1996/19961028.gash3368.html (accessed 15 December 2013). Ghana called for law enforcement cooperation through regional organizations and Interpol; leaders of the Dominican Republic have lumped human trafficking along with gun trafficking as an international cooperative law enforcement priority. See Third Committee, Press Release GA/SHC/3476 15th Meeting (AM) 16 October 1998. Available at: https://www.fas.org/irp/news/1998/10/19981016_gash3476.html (accessed 20 January 2014);

For a review see Simmons, Dobbin, and Garrett 2008.

For a review of the relevant literature, see Finnemore 1996.

Another important theoretical approach to policy diffusion is learning about best practices, but for a number of reasons we feel this is less relevant to the spread of criminalization of human trafficking and for brevity’s sake we omit discussion of it here. See generally Gilardi 2012 ; Meseguer 2005.On boundedly rational learning and policy diffusion see Weyland 2006. On political learning and policy diffusion see Gilardi 2010. Lack of good data on human trafficking (Andreas and Greenhill 2010 ; Weitzer 2014.) may make it difficult to” learn” about “successful” policies elsewhere.

Enforcement need not be certain. Criminalization may constitute a signal about intent when there is little information about the actual quality of enforcement. Analogously, see the argument about signaling as competition in competitive markets where product information is poor in Cao and Prakash 2011.

See, analogously, Baybeck, Berry, and Siegel 2011.

The literature on socialization is vast, and we do not review it exhaustively here. Two of the best sources on socialization in international relations are Johnston 2001.and Goodman and Jinks 2013.

See the discussion in Dobbin, Simmons, and Garrett 2007.

US pressure int his context is exerted primarily through social pressure than through material pressure. See Kelley and Simmons 2015, especially the discussion on pp. 56–62. Since the United States has referenced both human rights and the dangers of transnational crime as reasons to fight human trafficking, this hypothesis does not adjudicate the framing argument.

Exact definitions and sources for all variables as well as discussions of the individual methods, diagnostic tests and visualizations of all results can be found in the Methodological Appendix, located on the authors’ website at […]

Source: The UN Global Report on Trafficking in Person (2009)s, available at http://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/human-trafficking/global-report-on-trafficking-in-persons.html. (Accessed July 2016). Figure 1 reflects criminalization by this definition.