Abstract

As researchers who study enzyme chemistry embrace increasingly complex systems, especially biological machines, our attention is also shifting from steps involving covalent bond formation or cleavage to those that exclusively involve changes in non-covalent bonding. Assembly line polyketide synthases are an example of this growing challenge. By now, the chemical reactions underpinning polyketide biosynthesis can be unequivocally mapped to well-defined active sites and are, for the most part, readily explicable in the language of physical organic chemistry. Yet, all of these insights merely serve as a backdrop to the real problem of explaining how the catalytic functions of dozens of active sites are synchronized in order to allow these remarkable machines to turn over with remarkable specificity. Notwithstanding the fact that the time-honored language of physical organic chemistry can teach us a lot, it is often insufficient to describe many of these events, and must therefore evolve.

Keywords: enzymes, biological machine, polyketide synthase, non-covalent bonds

In a prescient 1987 article about the chemistry-biology interface, Arthur Kornberg quoted a then-recent recipient of the Nobel Prize in chemistry. When asked by a newspaper reporter whether he considered applying his novel technique to the study of enzymes, this individual replied: “I’m not about to switch from science to religion”.[1] This was back when most of the interesting questions about enzymatic catalysis could be drilled down to a few functional groups and covalent bonds in a relatively small region of the protein called an “active site”. And if a small molecule “cofactor” made an appearance in this active site, then it was expected that the enzyme mechanism could largely accountable by the intrinsic chemical reactivity of the cofactor, with the role of the polypeptide being confined to rate acceleration and substrate specificity.

How times have changed! Today, textbooks are replete with images of MDa-sized enzymatic machines depicting multiple active sites spread over hundreds of Ångstroms. Buried unceremoniously in this tour de force description is a “curly arrow” intended to convey the mechanism by which the machine converts substrate to product. (A good example is the textbook description of the catalytic cycle of the ribosome, Nature’s premiere peptide bond forming catalyst.[2]) Clearly, a profound shift appears to be occurring in the kinds of transition states that are deemed interesting in enzymology. It’s like the iPhone. While the name might suggest that this device is a legitimate descendent of Alexander Graham Bell’s invention, the similarity ends there, certainly in form and also, for the most part, in function.

This article is written from a perspective gained by having worked on multifunctional enzymes for ~ 25 years while teaching biochemistry to upper division undergraduates for about as long. Both experiences have led me to the same conclusion – the ways in which we conceptualize, interrogate and describe the “business portions” of enzymes will probably need to evolve faster, if chemistry is to keep pace with the complexity encountered at the leading edges of biology. Regrettably, I don’t have a recommendation; if I did, I’d be implementing it more aggressively in my own research and teaching activities.

For a particularly engaging account of the history of enzymology, the reader is encouraged to look at a perspective by Ringe and Petsko.[3] Rapid growth of this field over the past sixty years was propelled originally by in vitro reconstitution of the functions and X-ray crystallographic analyses of the structures of enzymes and, more recently, by methods for site-directed mutagenesis of proteins. When coupled with the principles of physical organic chemistry for analyzing structure-reactivity relationships, these technical advances led to impressive expositions of the catalytic chemistry of simple hydrolases, isomerases, bisubstrate transferases and ligases, and even some cofactor-dependent enzymes. In most cases, the approach was to first scaffold a problem in the qualitative language of arrow-pushing chemistry, and then buttress it with increasingly refined quantitative descriptions of rate-limiting steps together with the identification of individual functional groups that contribute most significantly to transition state stabilization. Needless to say, the focus was on covalent bond formation/ cleavage, presumably because this was the most fascinating aspect of the enzyme of interest.

As enzyme chemists started to interrogate more complex biological catalysts, attention (in at least some cases) shifted from steps involving covalent bond formation/cleavage to those that exclusively involved changes in non-covalent bonding. Transformations such as E→E* (or more artistic representations thereof) appeared with increasing frequency as key events in descriptions of catalytic cycles of some noteworthy enzymes. (Take, for instance, DNA polymerases.[4]) Even when X-ray crystallography yielded atomistic insight into the structural differences between E and E*, one could not turn to any time-honored principle of physical organic chemistry to find a satisfactory rationale for the interconversion between these two states. Hand-waving and unsatisfactory (at least to this author) explanations such as changes in multiple, accurately positioned non-covalent bonds became commonplace in concluding paragraphs of important papers. Chemists from other sub-disciplines found reason to deride major insights into enzyme mechanisms as little more than “blobology”.

Maybe it is precisely this feeling of dissatisfaction that motivates chemical biologists to study incredibly complex enzymes that play central roles in all sorts of life processes. But the frustration is palpable even for the most diligent students, as they make the transition from organic chemistry to enzyme chemistry. Consider the sharp contrast between the take-home messages of pyruvate dehydrogenase and ATP synthase, two classic enzymes of comparable physical complexity that students encounter within days of each other in a typical undergraduate biochemistry course. In the former case, students are enthralled by the ability to account for an impressive oxidative decarboxylation of an α-ketoacid based substantially on the properties of a simple thiazolium, dithiolane and alkylthiol. The rest, as some might say, is just “spinach”. Days later, spinach is all that stands between a downpour of protons and the formation of the most important anhydride in biology, and no jaw-dropping crystal structure or Disney video can persuade students that what they are learning is related in any way to what they already know about the chemical logic of anhydride bond formation. Surely there must be a self-consistent way to describe the functions of both these machines, not to mention scores of other biological catalysts of comparable or even greater complexity?

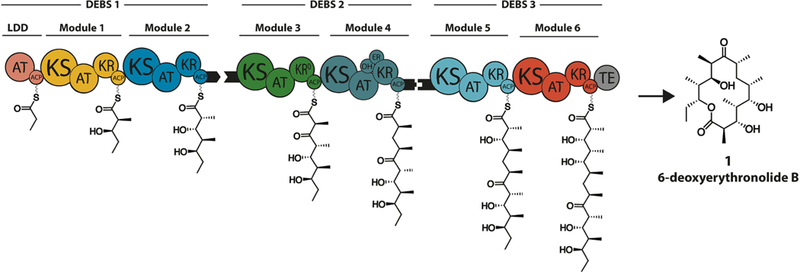

My collaborators and I have been studying enzymes that synthesize polyketide antibiotics in bacteria for more than 25 years. These remarkable enzyme assemblies catalyze elaborate multi-step metabolic transformations leading to the biosynthesis of many complex natural products. Perhaps their most distinctive feature is their ability to channel reactive intermediates between active sites with exquisite control. Nowhere is this on display more vividly than a subset of polyketide synthases (PKSs) that synthesize products via an assembly line paradigm, such as the 6-deoxyerythronolide B synthase (Figure 1).[5] It is estimated that the propionyl equivalent that primes the synthesis of 6-deoxyerythronolide B must be channeled along a ~ 500 Å trajectory before it is released as the final product. Not only is this distance considerably longer than the journey taken by glutamine-derived ammonia in the paradigmatic mammalian CAD (carbamoyl phosphate synthetase – aspartate transcarbamoylase – dihydroorotase) enzyme system,[6] but this trajectory must also be inherently flexible so as to enable rapid evolution of structurally diverse polyketide antibiotics.

Figure 1.

Architecture of the 6-deoxyerythronolide B synthase. The modular architecture of the three constituent proteins (DEBS1, DEBS2, and DEBS3) is shown in cartoon form, together with the product of each catalytic module attached to its acyl carrier protein (ACP) domain. Individual enzymatic domains are depicted as: AT – acyltransferase, KS – ketosynthase, KR – ketoreductase (KR0 – redox-inactive, epimerase-active KR), DH – dehydratase, ER – enoylreductase and TE – thioesterase. Black tabs represent docking domains, short C-terminal and N-terminal polypeptides that enable selective interactions between specific pairs of individual polypeptides.

Our studies on the 6-deoxyerythronolide B synthase began by interrogating the tolerance and specificity of individual enzymes (or clusters thereof, called “modules”) within this homodimeric multi-enzyme system harboring two copies each of twenty-two active sites. If PKSs had undergone such spectacular diversification on a relatively short evolutionary timescale, then surely they would be amenable to the power of genetic engineering? Perhaps not surprisingly, most active sites in the 6-deoxyerythronolide B synthase had modest specificity, if any, for their cognate substrates.[7] Relative kcat/KM values of 1–100 were the norm for most active sites that were probed with a systematic array of substrates; indeed, many analogues of cognate substrates were accepted with less than 10-fold discrimination. Exceptions to the general principle that Nature had harnessed non-selective enzymes to evolve assembly line PKSs were found in acyl transferases responsible for the selection of alternatively substituted malonate extender units by each module. These enzymes often exhibit > 1000X specificity for their cognate substrates, and can therefore be legitimately called “gatekeepers” of the assembly line.[8] The question of stereochemical control by assembly line PKSs also proved to be genuinely interesting. A series of investigations led by David Cane at Brown University revealed that only four active sites (the ketoreductase domains of modules 1, 2, 5, and 6 of the synthase) were necessary and sufficient for controlling eight out of ten stereocenters of 6-deoxyerythronolide B, whereas the remaining two were collaboratively installed by two or more active sites each.[9] Meanwhile, X-ray crystallographic analyses of prototypical PKS active sites confirmed that their substrate recognition features were dominated by binding pockets for the invariant pantetheine arm, a signature post-translational modification found on acyl carrier protein domains onto which PKS substrates are covalently tethered via thioester bonds. All in all, the question of tolerance and specificity of the 6-deoxyerythronolide B synthase proved to be a fascinating problem, albeit with substantial precedent in simpler, more well studied enzyme systems.

Throughout these early studies, the question of how substrates are channeled across the assembly line was side-stepped. In part, this was because available tools to interrogate PKSs were limited, but the temptation to do so was also based on the naïve assumption that the enzymes comprising PKS assembly lines were simply “beads on a string”. Evidence to the contrary started to emerge as portions of the 6-deoxyerythronolide B synthase, and eventually the complete assembly line itself, were functionally reconstituted in vitro.[10] In particular, a variety of experiments highlighted the pivotal roles of domain-domain interactions, especially those involving acyl carrier proteins and ketosynthases, in the catalytic cycle of the synthase.[11] The fact that selective perturbations of these interfacial interactions resulted in substantially diminished turnover rates strongly suggested that at least some non-reactive docking events outside enzyme active sites may be rate limiting in the PKS catalytic cycle. More recent experiments have even hinted at the existence of energetic coupling mechanisms to directionally translocate reaction intermediates over long distances.[12] It appears that Nature’s core principle for assembly line PKS diversification has been to evolve new manifolds for channeling reactive intermediates between pairs of pre-existing active sites. How a chemical biologist can be expected to reconstruct this evolutionary feat in the laboratory is beyond the scope of any established paradigm in physical organic chemistry. As the legendary Albert Eschenmoser once remarked in a private conversation after a lecture I gave in his presence, “I have a great respect for those of you who study biological processes that seem so dependent on non-covalent bonding. As if covalent bond chemistry isn’t complicated enough.”

Assembly line PKS chemistry is but one example of a growing challenge in the enzymology of biological machines. By now, the actual chemical reactions involved in polyketide biosynthesis can be unequivocally mapped to well defined active sites along the assembly line and are, for the most part, readily explicable in the language of physical organic chemistry. Yet, all of these insights merely serve as a backdrop to the “real” problem: How are the catalytic functions of dozens of active sites synchronized in order to allow a remarkable machine such as the 6-deoxyerythronolide B synthase to turn over at a velocity exceeding 1 min−1 with near-perfect functional group specificity and stereospecificity? While I don’t have a satisfactory answer to this question at present, I suspect that it will take more than arrow-pushing schemes and free-energy diagrams to formulate one. And I won’t be surprised if the most memorable scenes in an experimentally validated movie of this spectacular catalytic cycle show seemingly inconspicuous events such as the dislocation of a strand in a β-pleated sheet or the stiffening of a flexible loop. I just hope that, by then, the time-honored language of chemistry has also evolved to incorporate useful and satisfactory ways to describe the magical powers of “spinach”.

Acknowledgments

The author is especially grateful to Justin Du Bois for numerous discussions on the subject of this article in the context of our shared teaching obligations, and to David Cane and Christopher Walsh for analogous discussions in the context of our collaborative research pursuits. Research in the author’s laboratory has been supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01GM089734 and R01 DK063158).

Biography

Chaitan Khosla is a Professor in the Departments of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering at Stanford University. He received his Ph.D. from Caltech in 1990. Following postdoctoral studies at the John Innes Institute, U.K., he joined the faculty of Stanford University in 1992. Since 2013, he has also served as the founding Director of Stanford ChEM-H, an interdisciplinary institute that fosters collaborations between Stanford’s physical scientists, engineers, life scientists, and clinicians to address fundamental as well as practical challenges in human health.

References

- [1].Kornberg A, Biochemistry 1987, 26, 6888–6891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Mathews CK, van Holde KE, Appling DR, Anthony-Cahill SJ, Biochemistry (4th Edition) Pearson, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Ringe D, Petsko GA, Science 2008, 320, 1428–1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Mizrahi V, Henrie RN, Marlier JF, Johnson KA, Benkovic SJ, Biochemistry 1985, 24, 4010–4018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Fischbach MA, Walsh CT, Chem. Rev 2006, 106, 3468–3496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Moreno-Morcillo M, Grande-Garcia A, Ruiz-Ramos A, Del Cano-Ochoa F, Boskovic J, Ramon-Maiques S, Structure 2017, 25, 912–923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Khosla C, Tang Y, Chen AY, Schnarr NA, Cane DE, Annu. Rev. Biochem 2007, 76, 195–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Dunn BJ, Cane DE, Khosla C, Biochemistry 2013, 52, 1839–1841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Valenzano CR, Lawson RJ, Chen AY, Khosla C, Cane DE, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2009, 131, 18501–18511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Lowry B, Robbins T, Weng CH, O’Brien RV, Cane DE, Khosla C, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2013, 135, 16809–16812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Robbins T, Liu YC, Cane DE, Khosla C, Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol 2016, 41, 10–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Lowry B, Li X, Robbins T, Cane DE, Khosla C, ACS Cent. Sci 2016, 27, 14–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]