Abstract

Purpose:

To investigate how demographic factors, dating, and sexual behaviors are related to both initial and changing rates of sexting over time, we examined sexting involvement among ethnically diverse adolescents over a four-year period.

Methods:

1042 participants from seven public high schools throughout southeast Texas (Dating it Safe1 study) were asked yearly about sexting involvement, as well as sexual and dating behaviors.

Results:

Using latent growth curve modeling, results revealed that males and White participants had greater initial involvement in sexting compared to females and Hispanic and other ethnicities, respectively. In addition, we found that sexting significantly increased over the four-year period. Finally, participants who had sex and who had more dating partners at each wave were significantly more likely to be involved in sexting than their counterparts, even after controlling for their initial sexting involvement.

Conclusions:

Involvement in sexting increases steadily from adolescence into emerging adulthood. The current study extends prior research by identifying a longitudinal association between sexting and sexual activity.

Keywords: Sexting, gender, ethnicity, sexual activity, dating

Introduction

Sexting, or the exchange of self-made sexually explicit photographs via digital media, is prevalent among both adolescents and emerging adults. Coinciding with the ubiquity of smartphones, a recent meta-analysis found that sexting has been on the rise over the last decade and that, on average, 14.8% and 27.4% of teenagers are sending and receiving sexts, respectively.2 Sexting among emerging adults is estimated to be as high as 62%.3 Although cross-sectional studies have shown that sexting behavior increases as youth age, these can only provide a snapshot of a given behavior at one point in time. Longitudinal studies are a rarity in youth sexting research, but are urgently needed to adequately evaluate whether patterns of sexting change as youth age and, if so, determine what predicts change, and what associated sexual health behaviors are linked to these changes. The present study will be the first to assess sexting behavior over a four year period, and to examine how demographic variables, sexual behavior, and dating activity are related to both initial and changing rates of sexting over time.

A considerable number of studies have examined whether the prevalence of sexting varies according to the socio-demographic characteristics of participants; however, the research has been inconsistent.2 With regard to gender, some studies have found that girls are more likely to engage in sexting than boys,4 while others have either found a reverse relationship,5–7 or no gender differences at all.2,8–11 A similar pattern of inconsistency has been observed for ethnicity. Rice et al.12 and Dake, Price, Maziarz, and Ward13 found that youth who identified as Black were more likely to report engagement in sexting than their non-Black counterparts; however, Gregg et al.6 found no significant differences among ethnicity groups. With respect to socio-economic status (SES), one study found that youth who sext are more likely to perceive financial strain within their families than those who did not sext,14 whereas another study found the opposite - youth with a higher perceived family income were more likely to engage in sexting compared to youth who perceived their families’ income to be lower.8 Other studies have not found any association between adolescents’ sexting and SES.4,5,15

Taken together, studies examining the association been sexting and socio-demographic factors have displayed discrepancies. Such discrepancies could be explained by the cross-sectional nature of sexting research, as different samples and methods are often used in cross-sectional studies to explore associations between sexting and sociodemographic factors. Assessing these associations via a longitudinal analysis will help clarify whether discrepancies are due to the strength of associations shifting over time, or if they are a result of differing samples and methods that occur across cross-sectional research studies.

While the majority of adolescent sexting behavior occurs within a dating or romantic relationship,5,16 sexting can also be a modern form of flirting with the goal of initiating a romantic relationship.2,5,16 The association between sexting and number of dating partners that has been found in the literature may be due to teen sexting commonly occurring within the context of romantic relationship formation and maintenance.17 The relational context in which sexting often occurs, as well as the inherently sexual nature of sexting, predicates an association between sexting and sexual activity. Several cross-sectional studies demonstrate that engagement in sexting is associated with being sexually active4,7,18,19 and having a higher mean number of sexual partners.4,11,20 Thus, engagement in sexting can signal a willingness or readiness to engage in offline forms of sexual behavior.11,18

The current longitudinal study uses latent growth curve modeling to examine trajectories in observed sexting over a four-year period. Latent growth curve models can identify a youth’s initial sexting involvement status at the first time point, as well as the degree of change in sexting involvement over four years. Specifically, we examine whether: 1) teen involvement in sexting changes over a four-year timeframe – a period in which adolescents transition into emerging adulthood; 2) initial and changes in rates of sexting are related to age, gender, race, and SES; and 3) dating and sexual activity are associated with sexting over time. Consistent with recent meta-analytic and other empirical research,2 we predicted that sexting involvement would increase over time, and that increases in sexting would be associated with sexual activity and number of dating partners. However, given the inconsistency in the literature with regard to predictors of sexting, we did not make specific hypotheses on relations between sexting involvement and demographic variables.

Method

Procedure and Participants

Data were collected as part of Dating it Safe,1 a longitudinal study of adolescent health and risky behaviors. We recruited participants from seven public high schools throughout southeast Texas. Recruitment and baseline data collection occurred in spring 2010 during school hours in classes with mandated attendance (n = 1,042; response rate = 62%). Surveys were repeated annually (spring 2011 through spring 2015). When participants were no longer in school (e.g., transferred), the survey was completed via a web-based platform. Participants were reimbursed in the form of a $10 gift card at Waves 1–3, $20 gift card at Waves 4 and 5, and a $30 gift card at Wave 6. Written parental consent and student assent were collected prior to data collection once they indicated their willingness to participate. The study was approved by the last author’s Institutional Review Board.

At Wave 3, participants were 56% female (Mean age = 17.4 SD = 0.77), in the 11th grade (71%) or 12th grade (25%), and ethnically diverse (32% Hispanic, 27% African American, 30% White, and 12% other). Parental education was assessed with the following items: “did not graduate from high school” (16%), “finished high school or got a GED” (19%), “did some college or training after high school” (28%), and “finished college” (37%). See Table 1 for detailed characteristics of the sample by wave.

Table 1.

Demographic information for each wave of data collection

| Wave 3a | Wave 4a | Wave 5a | Wave 6a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency (%) | ||||

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 499 (55.82) | 444 (57.51) | 435 (62.59) | 460 (60.69) |

| Male | 395 (44.18) | 328 (42.49) | 260 (37.41) | 298 (39.31) |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Hispanic | 286 (31.99) | 249 (32.09) | 230 (33.09) | 247 (32.59) |

| White | 267 (29.87) | 232 (29.90) | 191 (27.36) | 218 (28.76) |

| African American | 237 (26.51) | 195 (25.13) | 188 (27.05) | 197 (25.99) |

| Others | 104 (11.63) | 100 (12.89) | 86 (12.37) | 96 (12.66) |

| Gradeb | ||||

| 10th | 8 (0.89) | - | - | - |

| 11th | 635 (71.03) | 2 (0.26) | - | - |

| 12th | 220 (24.61) | 565 (73.09) | - | - |

| other | 31 (3.47) | 22 (2.85) | - | - |

| High school | - | - | 5 (0.72) | 4 (0.53) |

| College/trade school | - | 142 (18.37) | 490 (70.20) | 495 (65.30) |

| Working | - | 42 (5.43) | 139 (20.00) | 209 (27.57) |

| Not in school and not working | - | - | 61 (8.78) | 50 (6.60) |

| Living situation* | ||||

| Both parents | 415 (46.42) | 348 (44.96) | ||

| One parent and one stepparents | 158 (17.67) | 131 (16.93) | ||

| Mother or Father (only) | 240 (26.85) | 198 (25.58) | ||

| Grandparents and others | 81 (9.06) | 97 (12.53) | ||

| Family (e.g., parents) | 392 (56.32) | 382 (50.53) | ||

| Friends/Roommates | 196 (28.28) | 172 (22.75) | ||

| Girlfriend/Wife or boyfriend/Husband | 68 (9.81) | 135 (17.86) | ||

| Alone | 37 (5.34) | 67 (8.86) | ||

| Age | 17.04 (0.77) | 17.96 (0.75) | 19.06 (0.79) | 20.03 (0.76) |

Note:

Data on sexting involvement was available for Waves 3–6

Responses options for grade and living situation were modified as participants were aged. Because we measured age only T1, the rest of waves were estimated based on survey completion each wave given information at T1.

Because relevant sexting items were not asked at Waves 1 and 2, our main outcome variable (i.e., sexting) and time-varying predictors (i.e., sexual behavior, number of dating partners, and number of sex partners) are from Waves 3 through 6. Seventy-one participants were excluded from analyses due to missing data points from Wave 3 to Wave 6 (Total N = 971). Retention, relative to Wave 1, was 93% at Wave 2, 86% at Wave 3, 75% at Wave 4, 67% at Wave 5, and 73% at Wave 6.

Measures

Sexting involvement (W3–W6) was assessed with the following four items using a yes/no format: [In the past year] (1), have you been asked to send naked pictures of yourself through text, email, or things like SnapChat?;” (2) “have you sent naked pictures of yourself to another through text, email, or SnapChat?;” (3) “have you asked someone to send naked pictures of them to you?;” and (4) “has anyone sent you a naked picture without you asking?” Items were summed (range = 0–4, Cronbach’s α = .74~.85), with greater scores indicating more involvement with sexting. We conducted confirmatory factor analysis with variance-adjusted weighted least squares to test validity of this measure. One factor model was considered as being acceptable based on fit indices (CFI: .99–1, TLI:.97–1 SRMR:.02-.05, RMSEA: .06-.11) and factor loadings (.66~.96) across all waves.

For dating behaviors (W3–W6), participants reported “How many boyfriends/girlfriends or dating partners have you had since the last survey (in the last 12 months)?” with response options from 0 = 0 dating partners to 6 = 5 or more dating partners. We did not distinguish non-dating youth from dating youth because sexting can occur among non-daters.17

For sexual behaviors (W3–W6), participants were asked whether they “have had sex (intercourse)” at each time of measure. We coded those who never had sex as 0 and those who have had sex as 1. Among youth who indicated they have had sex, we asked “In the past year (since the last survey), about how many people have you had sex (intercourse) with?” Consistent with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) definition of sexual risk behavior,21 the response options ranged between 0 = I have not had sex in the past year to 4 = 4 people or more.

Gender, ethnicity, age, and parental education served as time-invariant covariates. Gender and ethnicity were included as dummy-coded variables (e.g., male = 0 vs. female=1). White youth were considered the reference group (e.g., White = 0 vs. Hispanic = 1, White = 0 vs. African American = 1, and White = 0 vs. other ethnicity = 1).

Statistical Analysis

With Mplus 7.4,22 we used latent growth curve modeling23 with the full information maximum likelihood (FIML) method24 to deal with missing data. Because of skewness in the variables of interest, we used the robust maximum likelihood estimator.25 We conducted unconditional growth curve modeling and examined significant random variance for growth factors such as intercept and slope to investigate whether predictors of interest (e.g., gender, ethnicity) explained between-individual differences in sexting involvement. Next, we included demographic information (e.g., gender, ethnicity) and the number of dating partners and sexual activity with the full sample across waves (N = 971). The same model was then run by replacing sexual activity with number of sexual partners at Wave 3 (N = 568). Youth who were not sexually active at Wave 3 were excluded in this model. Model fit was determined with the following indices: Comparative Fit Iindex >.95, Root Mean Square Error of Appoximation <.06, and Standardized Root Mean square Residual<.08.26

Results

As shown in Table 2, involvement in sexting, sexual activity, and number of sexual partners increased over time, whereas the number of dating partners decreased. We tested whether youth who completed Wave 6 differed from those who did not. Significant differences did not emerge with respect to ethnicity, parental education, sexting involvement at each wave, number of sexual partners at each wave, and number of dating partners at Waves 4 and 5. However, significant differences did emerge with respect to the following: females χ2(1) = 24.18, less sexually active youth, χ2(1) = 4.02, p = .045, younger youth t(969) = 2.42, p = .02, and youth with fewer dating partners t(276.62) = 2.71, p < .01 at Wave 3 were more likely to complete the Wave 6 survey.

Table 2.

Frequency, Mean, SD, and associations among sexting involvement and dating and sexual behaviors

| Measures | Mean/Frequency (%) | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Sexting involvement (W3) | 1.15 Y:481 (54) N:411 (46) |

1.33 | |||||||||||||||

| 2. Sexting involvement (W4) | 1.11 Y:364 (48) N:401 (52) |

1.41 | .49 | ||||||||||||||

| 3. Sexting involvement (W5) | 1.29 Y:343 (50) N:340 (50) |

1.49 | .40 | .53 | |||||||||||||

| 4. Sexting involvement (W6) | 1.47 Y:395 (53) N:348 (47) |

1.59 | .31 | .44 | .54 | ||||||||||||

| 5. Sexually active (W3) | Y:568 (64) N:324(36) |

.33 | .19 | .16 | .12** | ||||||||||||

| 6. Sexually active (W4) | Y:567(73) N:208(27) |

.34 | .28 | .24 | .20 | .69 | |||||||||||

| 7. Sexually active (W5) | Y:554(80) N:138(20) |

.30 | .27 | .23 | .22 | .61 | .79 | ||||||||||

| 8. Sexually active (W6) | Y:653(87) N: 101(13) |

.27 | .24 | .23 | .23 | .49 | .65 | .79 | |||||||||

| 9. # of dating partner (W3) | 1.49 | 1.25 | .24 | .19 | 11** | .09* | .24 | .33 | .30 | .30 | |||||||

| 10. # of dating partner (W4) | 1.48 | 1.19 | .22 | .27 | .20 | .23 | .23 | .34 | .34 | .32 | .42 | ||||||

| 11. # of dating partner (W5) | 1.28 | 1.07 | .24 | .25 | .28 | .18 | .21 | .24 | .29 | .30 | .31 | .44 | |||||

| 12. # of dating partner (W6) | 1.30 | 1.08 | .18 | .16 | .14 | .23 | .22 | .25 | .26 | .26 | .25 | .32 | .36 | ||||

| 13. # of sex partner (W3) | 1.81 | 1.17 | .27 | .12* | .10* | .09+ | - | - | - | - | .39 | .26 | .18 | .14** | |||

| 14. # of sex partner (W4) | 1.92 | 1.20 | .23 | .27 | .16 | .16 | .14** | - | - | - | .22 | .37 | .18 | .15** | .50 | ||

| 15. # of sex partner (W5) | 1.94 | 1.25 | .23 | .23 | .35 | .23 | .11* | .14** | - | - | .17 | .29 | .43 | .18 | .40 | .45 | |

| 16. # of sex partner (W6) | 1.90 | 1.19 | .22 | .24 | .26 | .31 | .15 | .21 | .13 | - | .14 | .21 | .21 | .45 | .32 | .34 | .54 |

Note. Y indicates the number of youth (percentage) who reported engaging in sexting or sexual activity and N indicates the number of youth (percentage) who reported not engaging in sexting or sexual activity. The number of sex partners was derived only from youth who reported a history of sexual intercourse. Thus, associations between # of sex partners and being sexually active across waves are not shown. Due to missingness, sample size for each variable is not equal to N=971 and df for correlations varied. p-value for all associations was less than <.001 except for

<.05,

<.01,

<.10.

Unconditional Growth model for sexting

Model fit indices provided good fit, χ2(5) = 17.09, p = .004, RMSEA = .05, 95% CI= .03, .08, CFI = .97, SRMR = .04. Mean of the intercept (M = 1.10, p < .001) was significant indicating youth involvement in sexting (e.g., requesting, being asked, sending) at baseline (W3). The variance of the intercept (Var = 1.02, p < .001) was also significant, suggesting that sexting involvement at baseline could be explained by between-individual differences. Mean (M = .10, p < .001) and variance (0.14, p < .001) of the linear trajectory were significant, indicating that, respectively, adolescent sexting involvement increased over four years and between-individual differences exist. A significant negative correlation (r = −.11, p = .01, CI: −.19, −.02) between intercept and linear trajectory indicated that youth with more involvement in sexting at baseline had a slower growth rate compared to those with less involvement in sexting.

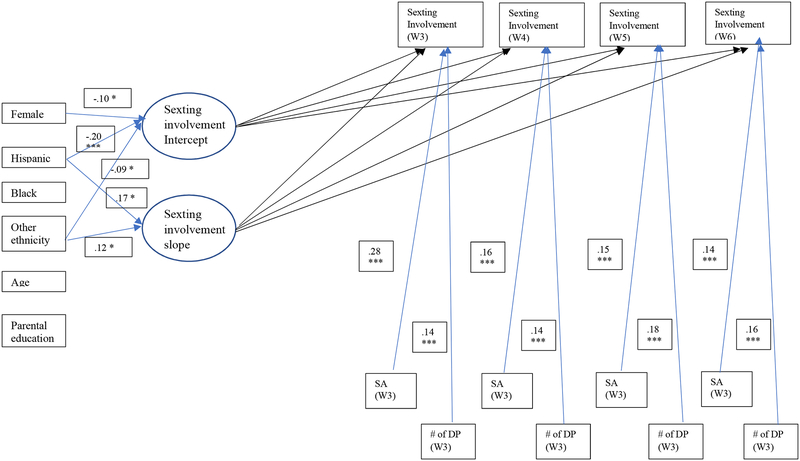

Growth curve model with variables

We included gender, ethnicity, age, parental education, number of dating partners, and sexual activity in the growth curve model (See figure 1). The model fit was acceptable, χ2(41) = 61.52, p = .02, RMSEA = .02, 95% CI: .01, .03, CFI = .98, SRMR = .03. While males were more likely to be involved in sexting at baseline (β = −.10, 95% CI: −.18, −.01), the growth rate did not differ by gender (β = −.02, p = .69, CI: −.13, .09). With respect to ethnicity, White adolescents were more involved in sexting at baseline than Hispanic (β = −.20, 95% CI: −.31, −.10) or “other” (β = −.09, 95% CI: −.18, −.00) youth. Conversely, Hispanic (β = −.17, 95% CI: .03, .32) and “other” (β = .12, 95% CI: .00, .23) youth exhibited a higher growth rate compared to White youth. Parental education (I: β = .03, p = .53; S: β = .04, p = .50) and age (I: β = .02, p = .71; S: β = −.09, p = .09) were not significantly related with the intercept or linear trajectory. Controlling for initial status and growth rate, youth who had sex at each wave and who had more dating partners had significantly greater sexting involvement over four years, relative to their counterparts.

Figure 1.

Number of dating partners and sexual activity over time.

Note. SA: being sexually active # DP: the number of dating partner, To avoid complication, variance, residual, correlation among variables, and nonsignificant paths were not shown. * <.05, **<.01, ***<.001

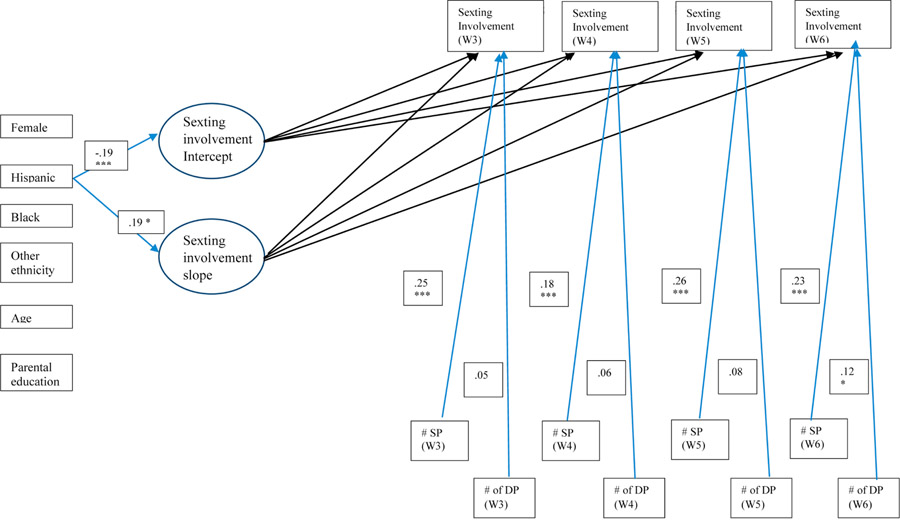

Next, we re-ran the same model with youth who reported prior sexual experience to examine whether the number of sexual partners explained the increase in sexting involvement controlling for the growth rate (See Figure 2). Based on fit (χ2(41) = 67.08, p < .01, RMSEA= .03, 95% CI: .02, .05, CFI = .95, SRMR = .03), the model was acceptable. Female, non-Hispanic ethnicity, age, and parental education did not emerge as significant predictors of initial or growth rate in sexting involvement for sexually active youth. While having more sexual partners was related to sexting involvement across four years, number of dating partners was not a significant predictor of sexting involvement until Wave 6 for this sub-sample.

Figure 2.

The number of dating and sex partners over times for youth who were sexually active at baseline.

Note. # SP = number of sex partners; # DP = number of dating partners. To avoid complication, variance, residual, correlation among variables, and nonsignificant paths for female, ethnicity, age, and parental education are not shown. * <.05, **<.01, ***<.001

Discussion

While prior sexting research has provided an understanding of the prevalence of sexting at specific time points across different ages, there remains a lack of understanding of how sexting changes over time, as well as predictors of change. Results from the current study revealed a steady linear increase in sexting among youth over a four-year period. There were also a number of demographic variables that predicted initial rates of sexting involvement, as well as rates of change over the four-year period. Finally, sexually active youth and youth with more dating partners had significantly greater sexting involvement across the four-year period.

Youth with less sexting involvement at baseline had a higher growth rate of sexting behavior over a four-year period relative to their more sexting involved counterparts. As peer norms have been shown to exert a significant influence on youth sexual activity,27–29 and findings have shown that the most important predictor of adolescents’ intentions to sext were perceived social norms29, it is possible that youth who are slower to begin sexting are influenced by peer sexting norms, thereby showing a more rapid increase in sexting involvement. Youth often misperceived and overestimated their peers’ engagement in risk behaviors, which in turn predicted an increase in their own engagement in risk behaviors over time.30 Perception of peer sexting may therefore contribute to the higher growth rate seen in youth who were originally less involved in sexting. However, this possibility must be considered in light of a simple and equally plausible explanation: That teens with high involvement in sexting at baseline had little room to grow (i.e., ceiling effect), making those less involved with sexting initially, appear to grow at a more rapid pace.

Males were more likely to be involved in sexting at baseline; however, the growth rate of sexting involvement did not differ by gender. This pattern mirrors research on sexual activity, which demonstrates that males are more likely to be engaged in sexual activity at a younger age, but by the end of the adolescent period, sexual activity occurs at the same rate for both males and females.31 Differences in socialization between males and females may partly account for these gender differences in sexual behavior. Compared to males, females tend to receive more cautionary and admonitory messages regarding their sexuality32 and tend to have more negative attitudes towards sexting,33 which may offset their initial involvement in both sex and sexting. Given that rates of sexual activity and sexting equal out over adolescence and emerging adulthood, the potential negative social consequences that initially deter females from both having sex and sexting may be eliminated once sexting has been initiated, thereby equalizing the prevalence of sexting among genders. These findings underscore the critical importance of studying sexting with longitudinal data so that sexting can be understood from a developmental perspective.

While White youth exhibited more sexting involvement at baseline, non-White youth showed a steeper increase in sexting behavior over time. While this could be secondary to a ceiling effect (white youth had little room to grow), it could also be that culture may impact the positive or negative associations individuals have to sexting. For example, Hispanic participants reported more positive expectancies of sexting, such as anticipated feelings of sexiness and excitement34. Highly acculturated young Latina women were found to ascribe to more traditional gender roles and engaged more in physical sexual communication, while less acculturated women engaged more in sexual health communication35. The impact of acculturation on sexual communication may translate to technology-based sexual interaction as well. These potential explanations are necessarily qualified by mixed findings in the literature surrounding ethnically or racially based differences in sexual behavior. The complexity of culture and its broad influence make it likely that any racially-based differences in sexting behavior are impacted by a multitude of factors that interact with culture in distinctive ways.

Sexual activity and number of sexual partners were positively associated with sexting at each time point. That is, the concurrent rise of both sexting, sexual activity, and number of sexual partners during this period reflects the sexual exploration and growth that occurs during adolescence and emerging adulthood.36 The phenomenon of sexting could be considered the manifestation of normative sexual development within a technological age; indeed, technology use has become intertwined with teens’ relational and romantic lives.37 While adolescent sexting has raised a great deal of concern in the public sphere, there is arguably little sense in viewing sexting as a deviant behavior. Rather, academic and public communities could begin to address the topic in terms of educating young people to make informed decisions about online communications with safety, privacy, and potential consequences in mind.

For youth who were sexually active at baseline, the number of dating partners was not significantly related to sexting involvement until the third time point, when youth were approximately 17 years of age. Finding that the prevalence of sexting was highest among young adults who were in committed relationships38 lends support to the idea that, relative to younger adolescents, sexting in older adolescents occurs more within exclusive or committed relationships. Findings suggest that sexting among younger adolescents is not enacted in the same relational context as it is in older adolescents. Whereas younger adolescents may jokingly exchange sexts with platonic friends, older adolescents reported sexting mainly in relation to flirting, romance, and sex.28

The current longitudinal design was able to decipher that gender and ethnicity were no longer predictors of initial rate or growth rate of sexting when assessing only those youth who were sexually active. As sexual activity is a variable that is frequently and significantly associated with sexting,39 other variables may show a less pronounced effect when sexual activity is considered in the analyses. While we cannot ascertain whether sexual activity or sexting occurs first, research has consistently shown that the relationship between sexting and sexual activity is robust.40 Temple and Choi found that sexting and sexual activity were temporally related, as there was an association between having sent a sext and being sexually active a year later39. Future longitudinal research should directly address the question of “what comes first – sexting or sexual behaviors?,” using cross lag models that can elucidate the directionality of associations. While demographic variables are important to continue to explore, results of the present study can solidify the notion that sexual activity is among the factors most strongly associated with sexting behaviors.

Limitations

Sexting was operationalized as “sexting involvement”. Specific sexting behaviors, such as being asked to send a sext, and sending, receiving, and requesting sexts, were combined into a general sexting measure. As such, we were unable to assess how distinct types of sexting behaviors changed over time. A concerning number of adolescents (12%) forward sexts without consent2. Assessing how this behavior changes over time may facilitate understanding of whether age and maturity contribute to changes in the prevalence of nonconsensual forwarding of sexts. Also, we did not measure contextual or relational factors regarding sexting. That is, sending sexts to romantic partners as opposed to friends could develop differently over time and could result in different outcomes. Future studies should address how individual, relational, and contextual risk and protective factors differentiate sexting trajectories over time. Finally, data for the current study were collected from students from a socio-economically and ethnically diverse region in Texas. Therefore, results may not be generalizable to populations from other regions or generations. Future studies should continue collecting and reporting on longitudinal research to enhance generalizability of knowledge.

Conclusions

The current study provides empirical evidence to support the notion that sexting involvement increases steadily over the period of adolescence and into early adulthood, and that a strong association exists between sexting involvement and sexual activity. Overall, assessing the longitudinal course of sexting helps to understand what variables relate to sexting rates over time, guides future research directions, and informs efforts to educate younger generations about sexuality, intimacy, and healthy communication in the digital age.

Supplementary Material

Implications and Contribution.

Sexting among late adolescents increases as youth transition to emerging adulthood. Involvement in sexting is longitudinally linked to sexual activity, suggesting that technology is interconnected with sexual development in adolescents and young adults.

Research Support:

This research was supported by grants from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development, K23HD059916 (PI: Temple), and from the National Institute of Justice, 2012-WG-BX-0005 (PI: Temple). The content of this manuscript is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not represent the official views of the sponsor. The work of Joris Van Ouytsel is supported by the Research Foundation - Flanders.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Temple J, Shorey R, Fite P, Stuart G, Le V. Substance use as a longitudinal predictor of hte perpetration of teen dating violence. J Youth Adolesc. 2013;42(4):596–606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Madigan S, Ly A, Rash CL, Van Ouytsel J, Temple JR. Prevalence of multiple forms of sexting behavior among youth: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172(4):327–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Drouin M, Coupe M, Temple JR. Is sexting good for your relationship? It depends … Comput Hum Behav. 2017;75:749–756. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ybarra ML, Mitchell KJ. “Sexting” and Its Relation to Sexual Activity and Sexual Risk Behavior in a National Survey of Adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2014;55(6):757–764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yépez-Tito P, Ferragut M, Blanca MJ. Prevalence and profile of sexting among adolescents in Ecuador. J Youth Stud. 2018:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gregg D, Somers C, Pernice F, Hillman S, Kernsmith P. Sexting Rates and Predictors from an Urban Midwest High School. J Sch Health. 2018;88(6):423–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frankel A, Bass S, Patterson F, Dai T, Brown D. Sexting, Risk Behavior, and Mental Health in Adolescents: An examination of 2015 Pennsylvania Youth Risk Behavior Survey Data. J Sch Health. 2018;88(3). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buren J, Lunde C. Sexting among adolescents: A nuanced and gendered online challenge for young people. Comput Hum Behav. 2018;85:210–217. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gamez-Guadix M, de Santisteban P. “Sex Pics?”: Longitudinal Predictors of Sexting Among Adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2018;63(5):608–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Strassberg DS, Cann D, Velarde V. Sexting by High School Students. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2017;46(6):1667–1672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Van Ouytsel J, Walrave M, Lu Y, Temple JR, Ponnet K. The Associations between Substance Use, Sexual Behavior, Deviant Behaviors and Adolescents’ Engagement in Sexting: Does Relationship Context Matter? J Youth Adolesc. 2018;47(11):2353–2370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rice E, Gibbs J, Winetrobe H, et al. Sexting and sexual behavior among middle school students. Pediatrics. 2014;134(1):e21–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dake JA, Price JH, Maziarz L, Ward B. Prevalence and Correlates of Sexting Behavior in Adolescents. AM J Sex Educ. 2012;7(1):1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Ouytsel J, Van Gool E, Ponnet K, Walrave M. Brief report: The association between adolescents’ characteristics and engagement in sexting. Journal of Adolescence. 2014;37(8):1387–1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Villacampa C Teen sexting: Prevalence, characteristics and legal treatment. Int J Law Crime Just. 2017;49:10–21. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Van Ouytsel J, Van Gool E, Walrave M, Ponnet K, Peeters E. Sexting: adolescents’ perceptions of the applications used for, motives for, and consequences of sexting. J Youth Stud. 2017;20(4):446–470. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Drouin M, Landgraff C. Texting, sexting, and attachment in college students’ romantic relationships. Comput Human Behav. 2012;28(2):444–449. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kosenko K, Luurs G, Binder AR. Sexting and Sexual Behavior, 2011–2015: A Critical Review and Meta-Analysis of a Growing Literature. J Comput-Mediat Comm. 2017;22(3):141–160. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rice E, Craddock J, Hemler M, et al. Associations Between Sexting Behaviors and Sexual Behaviors Among Mobile Phone-Owning Teens in Los Angeles. Child Dev. 2018;89(1):110–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Temple JR, Paul JA, van den Berg P, Le VD, McElhany A, Temple BW. Teen sexting and its association with sexual behaviors. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166(9):828–833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kann L, McManus T, Harris WA, et al. Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance - United States, 2017. MMRW Surveill Summ. 2018;67(8):1–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Muthén L, Muthén B. Mplus. The comprehensive modelling program for applied researchers: user’s guide. 1998–2015. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Duncan TE, Duncan SC, Strycker LA. An introduction to latent variable growth curve modeling: Concepts, issues, and application. Routledge; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Graham JW, Cumsille PE, Elek-Fisk E. Methods for Handling Missing Data. Handbook of Psychology. 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Curran PJ, West SG, Finch JF. The robustness of test statistics to nonnormality and specification error in confirmatory factor analysis. Psychol Methods. 1996;1(1):16–29. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lt Hu, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 1999;6(1):1–55. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Walrave M, Ponnet K, Van Ouytsel J, Van Gool E, Heirman W, Verbeek A. Whether or not to engage in sexting: Explaining adolescent sexting behaviour by applying the prototype willingness model. Telemat Inform. 2015;32(4):796–808. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lippman JR, Campbell SW. Damned if you do, damned if you don’t… if you’re a girl: Relational and normative contexts of adolescent sexting in the United States. J Child Media. 2014;8(4):371–386. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rice E, Rhoades H, Winetrobe H, et al. Sexually Explicit Cell Phone Messaging Associated with Sexual Risk Among Adolescents. Pediatrics. 2012;130(4):667–673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Helms SW, Choukas-Bradley S, Widman L, Giletta M, Cohen GL, Prinstein MJ. Adolescents misperceive and are influenced by high-status peers’ health risk, deviant, and adaptive behavior. Dev Psychol. 2014;50(12):2697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Martinez GM, Abma JC. Sexual activity, contraceptive use, and childbearing of teenagers aged 15–19 in the United States. 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ringrose J, Harvey L, Gill R, Livingstone S. Teen girls, sexual double standards and ‘sexting’: Gendered value in digital image exchange. Fem Theor. 2013;14(3):305–323. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Springston KM. Gender Differences in Participation in and Motivations for Sexting: The Effects of Gender Role Attitudes, Masculinity, and Femininity. Butler Journal of Undergraduate Research 2017;3(1):9. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dir AL, Coskunpinar A, Steiner JL, Cyders MA. Understanding differences in sexting behaviors across gender, relationship status, and sexual identity, and the role of expectancies in sexting. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2013;16(8):568–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alvarez C, Villarruel A. Association of gender norms, relationship and intrapersonal variables, and acculturation with sexual communication among young adult Latinos. Res Nurs Health. 2015;38(2):121–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tolman DL, McClelland SI. Normative sexuality development in adolescence: A decade in review, 2000–2009. J Res Adolesc. 2011;21(1):242–255. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lenhart A, Smith A, Anderson M. Teens, Technology and Romantic Relationships. Pew Research Center;2015. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Drouin M, Vogel KN, Surbey A, Stills JR. Let’s talk about sexting, baby: Computer-mediated sexual behaviors among young adults. Comput Human Behav. 2013;29(5):A25–A30. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Temple JR, Choi H. Longitudinal association between teen sexting and sexual behavior. Pediatrics. 2014;134(5):e1287–1292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.O’Neal N, Cummings T, Hansen C, Ott M. Predictors of sexting in a university population. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52(2):S87. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.