Abstract

Background:

Schooling is associated with a lower risk of Herpes Simplex Virus type 2 (HSV-2) in adolescent girls and young women (AGYW), but there is little understanding of the pathways underlying this relationship.

Methods:

We used data from adolescent girls and young women in South Africa enrolled in the HIV Prevention Trials Network (HPTN) 068 study. We tested a structural equation model where individual, household and community education measures were associated directly and indirectly with incident HSV-2 through HIV knowledge, future aspirations, age-disparate partnerships, sex in the last 12 months and condomless sex.

Results:

Community, household and individual measures of schooling were all associated with incident HSV-2 infection through mediated pathways that increased likelihood of having sex. Low school attendance (<80% of school days) increased likelihood of having sex through increased age-disparate partnerships and reduced future aspirations. Fewer community years of education increased likelihood of having sex through increased age-disparate partnerships. Parental education level was indirectly associated with HSV-2 overall, although we could not identify the individual pathways that were responsible for this association

Conclusion:

Community, and individual schooling interventions may reduce risk of HSV-2 infection by influencing likelihood of having sex, partner age and future aspirations.

Keywords: HSV-2, Mediation, Education, Sexual behaviors, Multilevel, Adolescent girls and young women

Introduction

Adolescent girls and young women (AGYW) in South Africa are disproportionately at risk of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) including Herpes Simplex Virus type 2 (HSV-2) and HIV. Patterns of HSV-2 prevalence show a strong differential by sex, with an estimated prevalence of 29% among young South African women compared to 10% in young South African men aged 15–26 [1]. Risk of STIs in AGYW is strongly correlated with social and structural factors including gender inequity, stigma and discrimination (around HIV or access to health care), poverty and education [2–4]. In our prior analyses among AGYW in South Africa we found that low school attendance and school dropout were associated with over twice the risk of both incident HIV and HSV-2 [5]. Yet, there is limited research to provide a more in depth understanding of this relationship, including determining whether household and community measures of education influence risk and examining the underlying pathways between schooling and HSV-2 infection.

Connections of parental and community education with HSV-2 infection:

Individual education has been associated with both HSV-2 and HIV infection, and is strongly correlated with parental and community education levels [6–8]. However, these measures have rarely been studied independently. Parental educational attainment is associated with socioeconomic disadvantage and a reduced prevalence of HIV [9]. At the community level, individual HIV knowledge can be increased through interaction with other community members with an equal or higher education level [10]. Negative gender norms are pervasive in many community settings in South Africa and have also been associated with access to education, intimate partner violence and sexual behaviors [11–13]. Other measures that are correlated with community education such as community cohesion, group membership and civic participation are associated with increased sexual behaviors among AGYW and with risk of STIs.[8,14–20]

Mediators between education and HSV-2:

Research on pathways for the relationship between education at any level (individual, family, community) and HSV-2 infection is similarly lacking. Our previous research from South Africa found that partner age difference and number of sexual partners both singly mediated the relationships between individual school attendance and incident HIV and HSV-2 infection [21]. Though that study provided some evidence that partner characteristics are important in the relationship between school attendance and HIV and HSV-2 infection, schooling is likely to influence other sexual behaviors. Further, no studies have examined group level education measures or other related mediators that have been hypothesized to be important in the relationship between education and HSV-2 infection, such as condomless sex and knowledge about sexual health, particularly when mediators are considered simultaneously.

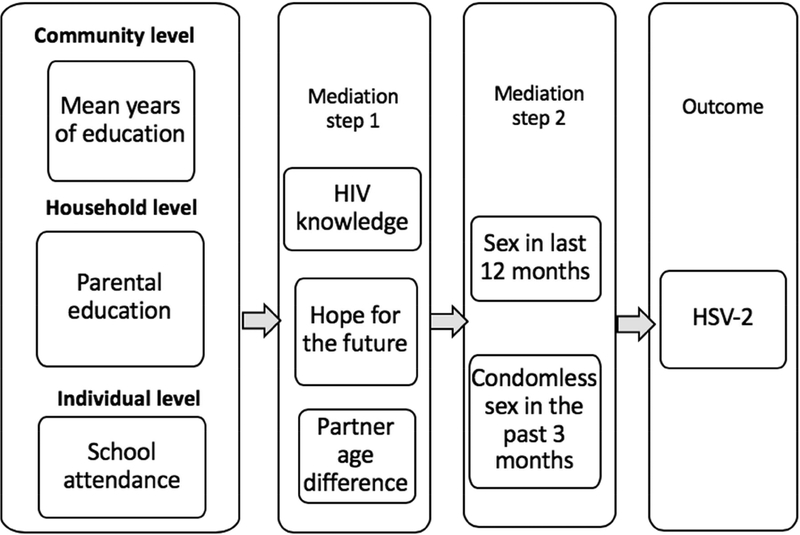

We used a comprehensive review by Jukes et al to develop our theoretical model [22]. Given the lack of research on HSV-2 and the similar pathways in the relationship between schooling and HIV infection, we used theoretical literature on HIV to guide our selection of mediators. We hypothesized that increased individual level school attendance would be related to a reduced risk of incident HSV-2 through two distinct mediation steps whereby education first influences HIV knowledge, age-disparate partnerships, or future aspirations and, through these factors, affects sexual behavior (Figure 1). HIV knowledge will be used to test the common hypothesis that more educated individuals are more exposed to preventative information about STIs and may be more likely to change their behaviors to prevent infection [22–25]. Future aspirations will be used to determine if more educated individuals have different aspirations for the future making them less inclined to engage in sexual activity that elevate exposure to STIs [22,26,27]. Lastly, partner age difference is included to examine the idea that educated individuals have different social and sexual networks based on being in school that might make them less exposed to infection [5,22]. In the second mediation step, we will examine how the first stage mediators influence sexual behaviors that can directly influence HSV-2 acquisition, including condomless sex and increased likelihood of sex in the last 12 months.

Figure 1: Conceptual model of individual, household and community measures of education leading to HSV-2 infection in young women *.

Note: This is a conceptual model and not an analytic model (e.g., DAG or SEM graph). Covariates (not shown in diagram for clarity): Age, SES, intervention randomization arm

*Definitions: Low school attendance < 80% of school days, Age disparate relationship (Partner 5 or more years older), Low HIV knowledge (≤50% correct); Community mean years of education

Overall, this study builds upon our previous research by testing a structural equation model for the relationship between multilevel measures of education and risk of incident HSV-2 infection among AGYW in South Africa. First, we tested the global fit of our theory-based structural equation model to the available empirical data. Second, we examined if individual, household and community measures of education were associated with risk of incident HSV-2. Third, we explored chained mediation pathways including through first stage (HIV knowledge, future aspirations, sexual networks) and second stage (sex in the last 12 months and condomless sex) mediators (Figure 1).

Methods

Study Population

We used longitudinal data from the HIV Prevention Trials Network 068 study (HPTN068) in rural South Africa. HPTN 068 was a randomized trial to determine if providing cash transfers, conditional on school attendance, would reduce incidence of HIV in AGYW [28,29]. The trial enrolled 2,533 AGYW in 2011 who were between the ages of 13–20, were not pregnant or married, had a parent/guardian in the household and were enrolled in grades 8–11. The study included AGYW living in 28 villages within the MRC/Wits Rural Public Health and Health Transitions Research Unit (Agincourt) in rural Mpumalanga Province, South Africa. The area is the site of the Agincourt Health and Socio-Demographic Surveillance Site (AHDSS) which includes an annual census of over 115,000 people. The area is rural with little infrastructure, high levels of poverty, unemployment and migration and high levels of social protection (80% receiving the child support grant) [30]. We included girls who were HIV and HSV-2 negative at baseline and had at least two annual follow-up visits to examine mediation, ensure temporal ordering, and isolate incident infections [29].

Young women were randomized 1:1 to the control or intervention arm and were followed annually from enrollment until study completion (up to three years in 2015) or graduation from high school, whichever came first. Young women remained in the study if they dropped out of school, were married or became pregnant. Each annual visit included an Audio Computer-Assisted Self-Interview (ACASI) survey and a test for HIV/HSV-2 for those who previously tested negative. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the University of the Witwatersrand Human Research Ethics Committee as well as the Provincial Department of Health’s Research Ethics Committee.

Ascertainment of exposures, outcome, mediators and covariates

The main exposure of time-varying, individual school attendance was defined as the percentage of school days attended in the months between study visits based on high school attendance registers [5,29]. The exposure was dichotomized as high (≥80% school days) versus low attendance (<80% school days), using the cutoff from the cash transfer intervention. [5,28]. Other multilevel measures of education included baseline parental level of education and time-varying community mean years of education (based on reported village if the girl moved). Parental education was a categorical variable defined using four categories: no school, primary school, some secondary school, and completed secondary or higher education. Mother’s educational level was used unless the mother had died, in which case father’s educational level was used. Mean community years of education was a continuous variable created using village level information from the Agincourt HDSS census about the village where the girl reported currently living [30]. This variable was constructed as the mean of the total years of education reported by all individuals living in a specific village. The outcome of incident HSV-2 infection was defined as new cases of HSV-2 detected following enrollment [28].

The time-varying mediators that were examined in our study were future aspirations (hope for the future), condomless sex in the last 3 months, age-disparate partnerships (partner ≥5 years older), having sex in the last 12 months and HIV knowledge (Figure 1). Hope for the future was a continuous variable constructed using a scale that was created and validated using the HPTN 068 cohort [31]. The hope for the future scale consists of 12 items with a 4-point likert response from ‘1’ for totally disagree to ‘4’ for totally agree. All sexual behaviors were self-reported. Condomless sex in the last 3 months was defined as not using a condom at the last vaginal or anal sex. Having an age-disparate partnership was defined as having at least one sexual or nonsexual partner five or more years older. This categorization has been used in prior HPTN068 analyses and is conventional in the literature [32]. Condomless sex and sex in the last 12 months were coded as 0 if the girl did not have sex in the last 12 months and partner age was coded as 0 if she did not report a partner. HIV knowledge score was used as a proxy for general knowledge about prevention of STIs and was defined as the number of questions answered correctly using a six-question scale. [33] HIV knowledge was dichotomized as answering more than 50% of questions correctly versus less than 50%. Mediators were ascertained from the time-point following exposures and before the outcome ascertainment.

Covariates that were included in all models were age at baseline, intervention assignment at baseline and baseline socioeconomic status (SES)). SES was constructed using principle components analysis with assets and divided into quartiles. Age was selected as a covariate as it is one of the strongest factors related to risk of HSV-2 infection [34] and SES was selected as it is closely linked to education level [22]. Randomization arm was included in all models to account for the original study design of the randomized trial.

Statistical analysis:

We used structural equation modelling in Mplus version 8.1 to test our model for the relationship between multilevel measures of education and risk of HSV-2 infection including through all mediators (Figure 1). We used a discrete time survival model with the Mplus Bayes estimator and non-informative priors to examine mediation paths. The Bayesian estimator was used instead of other available estimation options (e.g., maximum likelihood) because it simultaneously: 1) includes cases with partial data; 2) allows for correlated residuals among the multiple mediators; 3) computes optimal asymmetric credible intervals (the Bayesian analog of confidence intervals used in frequentist statistics, abbreviated as CI) for indirect effects; 4) allows for multiple mediators in a sequential arrangement (chained mediation); and 5) can be used to test a specific model within the structural equation modeling framework [35]. For continuous mediators, the model uses a normal distribution; for binary mediators and the HSV-2 outcome, a probit distribution with underlying latent variables with a standard normal residual distribution is assumed. Therefore, the coefficients (B) represent linear regression coefficients between exposures and the underlying latent representations for binary variables, including HSV-2 (i.e., the change in the continuous underlying latent variable per one unit change in the exposure). We report standardized coefficients and 95% credible intervals (CI). Global model fit for the proposed SEM was assessed using the posterior predictive p-value (PPP). PPP values close to .50 indicate excellent model-data fit whereas PPP values close to 0 or 1 indicate poorer fit [36].

We estimated both the indirect association through each of the mediated paths and the direct association not through each mediator for each exposure [37]. To account for the sequence of mediators, we modelled first stage mediators (knowledge, hope for the future, age-disparate partner), second stage mediators affected by first stage mediators (sex in the last 12 months and condomless sex) and then HSV-2 affected by all mediators. Covariates were included in the model for the first-stage mediators and the outcome.

Results:

Of the 2,533 young women enrolled in the original trial, we included 1,691 girls who were HSV-2 and HIV negative at baseline and had at least three visits (at baseline and two follow-up visits later). There were 120 incident HSV-2 infections over the study period in 6,723 study visits. At baseline, the median age was 15 years (interquartile range (IQR) 14,16), 3.7% had an age-disparate partnership, 19.5% had sex in the last 12 months, 60.0% had a low hope for the future score (below median of 35), 63.0% had low HIV knowledge, 5% had condomless sex in the last 3 months, and 96.6% had high attendance in school (>80% school days; Table 1). About 17% had a parent with no education, and the mean years of community education was 6.6, representing completion of some primary school. Over the entire study period, girls reported having a partner in the last 12 months at 29.2% of visits, an older partner at 6.5% of visits, and unprotected sex at 7.8% of visits.

Table 1:

Baseline characteristics of young women aged 13 to 20 without prevalent HSV-2 infection and at least three follow-up visits in Agincourt, South Africa from March 2011 to December 2012 (N=1,691)

| N (%) | Median (IQR) | |

|---|---|---|

| Young women’s age at baseline (year) | 15 (14,16) | |

| Age 13–14 | 685 (40.5) | |

| Age 15–16 | 772 (45.6) | |

| Age 17–18 | 203 (12.0) | |

| Age 18–20 | 31 (1.8) | |

| High attendance in school (≥80%) | 1624 (96.6) | |

| Household wealth | ||

| Low | 428 (25.3) | |

| Middle to Low | 5466 (25.3) | |

| Middle | 400 (23.7) | |

| High | 395 (23.4) | |

| Parental Education at baseline (Household) | ||

| No school | 258 (16.8) | |

| Primary School | 371 (24.2) | |

| Some secondary school | 467 (30.4) | |

| Completed secondary or higher | 440 (28.7) | |

| Community mean years of education | 6.6 (6.1,6.9) | |

| Community max years of education | 8 (7,8) | |

| Hope for the future score (continuous) | 32 (26,38) | |

| Low hope for the future score (below median) | 1006 (60.0) | |

| Low HIV knowledge (≤50% correct) | 1042 (63.0) | |

| Sex in the last 12 months | 327 (19.5) | |

| Age disparate relationship (Partner 5 or more years older) | 60.(3.7) | |

| Ever had sex | 318 (18.8) | |

| Any condomless sex in last 3 months | 84 (5.0) | |

| CCT randomization arm | 912 (53.9) | |

Total N=1,691; Missing: age 0; randomization arm 0; SES 2; age difference 55;; sex in last 12 months 15; school attendance 10; physical violence 37; ever had sex 2, partner in last 12 months 15; HIV knowledge 38; hope for the future 16; parental education 155; condomless sex 13.

For the specified structural equation model, the PPP value was 0.30, indicating satisfactory global model-data fit [36]. The percent of the variance in HSV-2 explained by the model was 21.9% (95% CI: 13.3% to 31.5%). Table 2a shows associations for the first step of the chained mediation pathway examining how multilevel exposures of education affect first stage mediators (low hope for the future, HIV knowledge and age-disparate partnerships). At the individual level, young women with low school attendance had a lower hope for the future (B - 0.12; 95% CI: −0.09, −0.15) and had a higher propensity of having an age-disparate partnership (B 0.15; 95% CI 0.11, 0.18). At the household level, young women with a parent with some secondary (B −0.04; 95% CI −0.01, −0.08) and primary education (B −0.05; 95% CI −0.01, −0.08) had lower hope for the future, compared to a parent who had completed secondary education. At the community level, lower mean years of education was associated with a higher propensity of having an age-disparate partnership (B 0.08 per 1-year decrease in mean education; 95% CI: 0.04, 0.12).

Table 2a.

Linear regression coefficients (B) and 95% credible intervals (CI) for the associations in step 1 of the mediation pathway*

| Exposures | Outcome | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Hope for the future | Older partner | Knowledge | |

| B (95% CI) | B (95% CI) | B (95% CI) | |

| Low attendance | −0.12 (−0.09,0.−15) | 0.15 (0.11,0.18) | −0.00 (−0.05,0.05) |

| Household level education | |||

| No school | 0.01 (−0.03 0.04) | 0.01 (−0.05,0.06) | 0.03 (−0.04,0.10) |

| Primary school | −0.05 (−0.01, −0.08) | 0.03 (−0.02,0.09) | 0.03 (−0.04,0.10) |

| Some secondary school | −0.04 (−0.01, −0.08) | 0.05 (−0.00,0.11) | −0.01 (−0.07,0.06) |

| completed secondary | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Mean years of community education | −0.02 (−0.05,0.01) | 0.08 (0.04,0.12) | 0.04 (−0.04,0.08) |

adjusted for SES, age, and randomization arm; HR = Approximate Hazard Ratio, CI = Confidence Interval

Table 2b shows associations between the first stage mediators (hope for the future, HIV knowledge and age-disparate partnerships) and second stage mediators (condomless sex and sex in the last 12 months). All first stage mediators were associated with sex in the last 12 months. Low hope for the future and age-disparate partnerships were associated with condomless sex, while HIV knowledge was not.

Table 2b.

Associations for step 2 of the mediation pathway

| Exposures | Outcome | |

|---|---|---|

| Condomless Sex | Sex in the last 12 months | |

| B (95% CI) | B (95% CI) | |

| Hope for the future | −0.10 (−0.15 −0.05) | −0.06 (−0.10, −0.02) |

| Partner age difference (>= 5 years) | −0.50 (−0.55 −0.45) | 0.68 (0.64,0.72) |

| HIV knowledge | −0.02 (−0.11,−0.06) | 0.16 (0.08,0.23) |

HR = Approximate Hazard Ratio, CI = Confidence Interval

Table 2c shows the third step of the mediation chain examining associations between the second stage mediators (condomless sex and sex in the last 12 months) and incident HSV-2 infection. Young women who had sex in the last 12 months had a 0.53 higher propensity of HSV-2 infection (95% CI 0.23, 0.82). However, condomless sex was not associated with an increased incidence of HSV-2 (B 0.27; 95% −0.04, 0.57).

Table 2c.

Associations for step 3 of the mediation pathway

| Exposures | Outcome |

|---|---|

| HSV-2 | |

| B (95% CI) | |

| Condomless Sex | 0.27 (−0.04,0.57) |

| Sex in the last 12 months | 0.53 (0.23,0.82) |

adjusted for low attendance, HH level education, community mean education, SES, age, randomization arm. HR = Approximate Hazard Ratio, CI = Confidence Interval, N=6,723 person-time observations from 1,691 participants.

Overall, all three multilevel measures of education were indirectly associated with incident HSV-2 infection through our mediators of interest (Table 3). At the individual level, lower school attendance was associated with a higher propensity of HSV-2 indirectly (B 0.04; 95% CI 0.02, 0.06) and overall (B 0.09; 95% CI 0.02, 0.16) (Table 3). At the household level, compared to having a parent that completed secondary school, we found an indirect association for not completing secondary school on HSV-2 (B 0.01; 95% CI 0.00 ,0.02). At the community level, a 1-year decrease in the mean level of village education was associated with a 0.01 (95% CI 0.01, 0.35) increase in the underlying propensity of HSV-2 infection. We did not identify a total association between community education and HSV-2. In this instance, the total association could be null because these associations operated in opposite directions and therefore could have cancelled each other out (Table 3) [38].

Table 3:

Linear regression coefficients (B) and 95% credible intervals (CI) for the total, direct and total indirect associations of each multilevel exposure of education with incident HSV-2 infection*

| Total | Total Indirect | Direct | |

|---|---|---|---|

| B (95% CI) | B (95% CI) | B (95% CI) | |

| Community: Mean vears of education | −0.01 (−0.08, 0.07) | 0.02 (0.01,0.03) | −0.03 (−0.10,0.05) |

| Household: Parental level of education | |||

| No school | −0.01(−0.11,0.08) | 0.00(−0.01,0.23) | −0.02(−0.12,0.08) |

| Primary school | −0.11(−0.22, −0.001) | 0.01(0.00,0.03) | −0.12(−0.23, −0.01) |

| Some secondary school | −0.04(−0.14,0.06) | 0.01(0.00,0.02)* | −0.05(−0.15,0.05) |

| Completed secondary (ref) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Individual: Low school attendance | 0.09(0.02,0.16) | 0.04(0.02,0.06) | 0.05(−0.02,0.12) |

CI = Credible Interval; Bold is P <= 0.05; N=6,723 person-time observations from 1,691 participants.

Lower bound is 0.001 due appears as 0.00 due to rounding

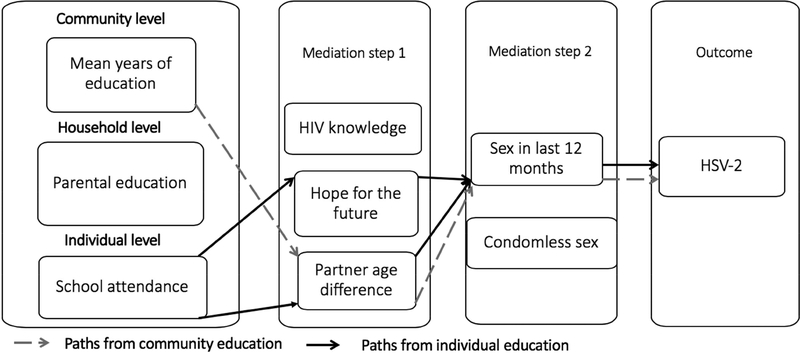

Figure 2 shows the chained (sequential) mediation pathways for the indirect associations between each measure of education and incident HSV-2 infection. Low school attendance increased incident HSV-2 infection by increasing propensity of an age-disparate partnership (B 0.05; 95% CI 0.02, 0.09) and increasing hope for the future (B 0.003; 95% CI 0.001, 0.01) which then increased sex in the last 12 months. At the household level, we did not identify any specific pathways. At the community level, a 1-year decrease in the mean level of education was associated with a higher propensity of incident HSV-2 infection because young women were more likely to have an age-disparate partnership and then more likely to have sex in the last 12 months (B 0.03; 95% CI 0.01, 0.05).

Figure 2: Significant pathways for the effect of multilevel measures of schooling on incident HSV-2 infection*.

*All paths were significant at alpha <.05; Path for mean community level of education (B: .03; 95% CI .01–.05);

Path for school attendance through future aspirations (B: .00; 95% CI .00–.01); Path for school attendance through partner age (B: .05; 95% CI .02–.09); N=6,723 person-time observations from 1,691 participants.

*Definitions: Low school attendance <80% of school days, age-disparate relationship (partner aged ≥5 years), low HIV knowledge (≤50% correct); Community mean years of education. HSV-2, Herpes simplex virus type 2

Discussion:

Low attendance in school, lower community mean years of education, and lower parental level of education were all indirectly associated with HSV-2 infection through mediation. Sequential mediation pathways ultimately operated through an increased likelihood of having sex. Low school attendance increased probability of having sex through reduced future aspirations and increased age-disparate partnerships. Lower community years of education increased probability of sex through increased age-disparate partnerships. Lower parental education level was associated with HSV-2 through mediators, although we could not identify the individual pathways that were responsible for this association.

Our results are consistent with prior studies showing a strong relationship between individual school attendance and HSV-2 infection [2,5] and identifying that this relationship operates through increased age-disparate partnerships and likelihood of having sex [21]. However, we further identify multistep mediation pathways underlying these associations and show that both increased age-disparate partnerships and reduced hope for the future increase likelihood of having sex and risk of HSV-2. Our results support previous findings that school attendance may prevent HIV and HSV-2 by reducing opportunities for sexual activity and encouraging partnerships with same-age peers rather than older partners when sexual activity does occur [21]. However, we add to these findings with evidence to support the hypothesis that young women who are in school have different aspirations for the future that reduce risk of HSV-2, in this case by reducing likelihood of having sex [26,27,39]. Structural interventions to increase individual school attendance make AGYW feel more hopeful about the future, changing sexual behavior. Building positive future aspirations is particularly critical for AGYW in contexts like the ADHSS area, where there are limited opportunities for employment or higher education and AGYW may feel pressure to start a family. In addition, the indirect association between parental education and HSV-2 highlights the importance of positive role models and support for young women, which can increase individual aspirations to complete school. [6,7]

We identified an indirect association between decreased community mean years of education, and increased incidence of HSV-2 infection that operated through an increased probability of having an age-disparate partnership. These findings could be related to men in more education communities perceiving risk to be higher in relationships with younger women and not engaging in these relationships.[40] Or, community education may be a marker for other community level variables that affect HSV-2 acquisition such as gender norms, community cohesion, group participation and stigma and discrimination which are related to HIV risk. [8,14–20] More research is needed regarding how these other factors correlate with community level education to understand how to best intervene, but we do see that age-disparate relationships, a strong determinant of HIV risk, can be changed through community level charaacteristics.

Our study is one of the first to investigate chained mediation pathways that involve multiple factors in the relationship between multilevel measures of education and incident HSV-2. However, many of the mediators of this relationship are self-reported sexual behaviors which may have resulted in under-reporting, socially desirable reporting, or recall biases. Second, in order to examine mediation, our sample was limited to participants who had at least two follow up visits and participants may be older. Additionally, the use of three visits limited our power to examine incident HIV infection and therefore only incident HSV-2 was examined as an outcome. Given our specification of a model with relatively few covariates, it is also possible that we are not including important confounders. We did not explicitly model loss to follow up in the analysis but retention was high in the study (87% control, 95% intervention). [29] The remaining few cases with partial data were included in the structural equation modeling under the relatively mild conditionally missing at random (MAR) assumption via Bayesian estimation. Lastly, we used a comprehensive review by Jukes et al to develop our theoretical model for the relationship between education and HIV infection and therefore assume that pathways in that review are most likely [22].

We used the Bayesian SEM approach implemented in Mplus because it was the only approach that allowed us to test a SEM with multiple, sequential mediators and assess model fit. However, this approach is limited in interpretability. In addition, the associations obtained are not estimates of parameters that can be defined as hypothetical interventions, as they would be if using a causal inference framework; obtaining estimates of parameters that correspond to hypothetical interventions in the context of complex SEMs with multiple sequential mediators is an area of ongoing research. Lastly, our method assumes that there is no interaction between the exposure and mediator.

In conclusion, household, community and individual measures of schooling were associated with incident HSV-2 infection among AGYW and this relationship primarily operated through likelihood of having sex. Low attendance in school led to both increased age-disparate partnerships and reduced aspirations for the future which increased likelihood of having sex. Lower community education influenced HSV-2 through increased age-disparate relationships. Structural interventions to increase access to education are important to elevate future aspirations and decrease age-disparate partnerships, thus reducing risk of HSV-2 infection. Additionally, increasing the community level of education could be a way to reduce risk of STIs in young women by reducing age-disparate partnerships.

Acknowledgement:

This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) [R01MH087118 and R01 MH110186] and by Award Numbers UM1 AI068619 (HPTN Leadership and Operations Center), UM1AI068617 (HPTN Statistical and Data Management Center), and UM1AI068613 (HPTN Laboratory Center) from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), the National Institute of Mental Health and the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Additional support was provided by the Division of Intramural Research, NIAID, NIH. This work was also supported by the Carolina Population Center and its NIH Center grant [P2C HD050924]. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. We thank the HPTN 068 study team and all trial participants. The MRC/Wits Rural Public Health and Health Transitions Research Unit and Agincourt Health and Socio-Demographic Surveillance System have been supported by the University of the Witwatersrand, the Medical Research Council, South Africa, and the Wellcome Trust, UK [058893/Z/99/A, 069683/Z/02/Z, 085477/Z/08/Z, 085477/B/08/

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of Interest: None

References:

- [1].Jewkes R, Wood K, Duvvury N. “I woke up after i joined Stepping Stones”: Meanings of an HIV behavioural intervention in rural South African young people’s lives. Health Educ Res 2010;25:1074–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Pettifor AE, Levandowski BA, Macphail C, et al. Keep them in school: The importance of education as a protective factor against HIV infection among young South African women. Int J Epidemiol 2008;37:1266–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Harrison A, Colvin CJ, Kuo C, et al. Sustained High HIV Incidence in Young Women in Southern Africa: Social, Behavioral, and Structural Factors and Emerging Intervention Approaches. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2015;12:207–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Pettifor A, Stoner M, Pike C, et al. Adolescent lives matter: Preventing HIV in adolescents. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 2018;13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Stoner MCD, Pettifor A, Edwards JK, et al. The effect of school attendance and school dropout on incident HIV and HSV-2 among young women in rural South Africa enrolled in HPTN 068. AIDS 2017;31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Dubow EF, Boxer P, Huesmann LR. Long-term Effects of Parents’ Education on Children’s Educational and Occupational Success: Mediation by Family Interactions, Child Aggression, and Teenage Aspirations. Merrill Palmer Q 2009;55:224–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Dickson M, Gregg P, Robinson H. Early, Late or Never? When Does Parental Education Impact Child Outcomes? Econ J 2016;126:F184–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Gregson S, Terceira N, Mushati P, et al. Community group participation: Can it help young women to avoid HIV? An exploratory study of social capital and school education in rural Zimbabwe. Soc Sci Med 2004;58:2119–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Bärnighausen T, Hosegood V, Timaeus IM, et al. The socioeconomic determinants of HIV incidence: evidence from a longitudinal, population-based study in rural South Africa. AIDS 2007;21 Suppl 7:S29–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].World Food Program. Literature review on the impact of education level on HIV/AIDs prevalence rates. Rome, Italy: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- [11].Pulerwitz J, Barker G. Measuring attitudes toward gender norms among young men in Brazil: Development and psychometric evaluation of the GEM scale. Men Masc 2008. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Greig A, Peacock D, Jewkes R, et al. Gender and AIDS: time to act. AIDS 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Seth P, DiClemente RJ, Lovvorn AE. State of the evidence: Intimate partner violence and HIV/STI risk among adolescents. Curr HIV Res 2013;11:528–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Jennings JM, Hensel DJ, Tanner AE, et al. Are social organizational factors independently associated with a current bacterial sexually transmitted infection among urban adolescents and young adults? Soc Sci Med 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Crosby RA, Holtgrave DR, DiClemente RJ, et al. Social capital as a predictor of adolescents’ sexual risk behavior: A state-level exploratory study. AIDS Behav 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Youngblade LM, Curry LA, Novak M, et al. The impact of community risks and resources on adolescent risky behavior and health care expenditures. J Adolesc Heal 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Gregson S, Mushati P, Grusin H, et al. Social capital and women’s reduced vulnerability to HIV infection in rural Zimbabwe. Popul Dev Rev 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Kerrigan D, Witt S, Glass B, et al. Perceived neighborhood social cohesion and condom use among adolescents vulnerable to HIV/STI. AIDS Behav 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Pronyk PM, Harpham T, Morison LA, et al. Is social capital associated with HIV risk in rural South Africa? Soc Sci Med 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Browning CR, Leventhal T, Brooks-Gun J. Sexual initiation in early adolescene: The Nexus of parental and community control. Am Sociol Rev 2005. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Stoner MC, Pettifor A, Eduwards JK, et al. Does partner selection mediate the relationship between school attendance and HIV/HSV-2 among adolescent girls and young women in South Africa: An analysis of HPTN 068 data. JAIDS (in Press 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Jukes M, Simmons S, Bundy D. Education and vulnerability: the role of schools in protecting young women and girls from HIV in southern Africa. AIDS 2008;22 Suppl 4:S41–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Gregson S, Zhuwau T, Anderson RM, et al. Is there evidence for behaviour change in response to aids in rural Zimbabwe? Soc Sci Med 1998;46:321–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Rosenstock IM. The Health Belief Model: Explaining Health Behavior Through Expectancies. Heal Behav Heal Educ 1990:39–61. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Ajzen I Perceived behavioral control, self-efficacy, locus of control, and the theory of planned behavior. J Appl Soc Psychol 2002;32:665–83. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Kirby D The impact of schools and school programs upon adolescent sexual behavior. J Sex Res 2002;39:27–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].de Walque D How does the impact of an HIV/AIDS information campaign vary with educational attainment? Evidence from rural Uganda. J Dev Econ 2007;84:686–714. [Google Scholar]

- [28].Pettifor A, MacPhail C, Selin A, et al. HPTN 068: A Randomized Control Trial of a Conditional Cash Transfer to Reduce HIV Infection in Young Women in South Africa???Study Design and Baseline Results. AIDS Behav 2016;20:1863–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Pettifor A, MacPhail C, Hughes JP, et al. The effect of a conditional cash transfer on HIV incidence in young women in rural South Africa (HPTN 068): a phase 3, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Glob Heal 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Kahn K, Collinson MA, Xavier Gómez-olivé F, et al. Profile: Agincourt health and socio-demographic surveillance system. Int J Epidemiol 2012;41:988–1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Abler L, Hill L, Maman S, et al. Hope Matters: Developing and Validating a Measure of Future Expectations Among Young Women in a High HIV Prevalence Setting in Rural South Africa (HPTN 068). AIDS Behav 2017;21:2156–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Stoner MCD, Nguyen N, Kilburn K, et al. Age-disparate partnerships and incident HIV infection in adolescent girls and young women in rural South Africa: An HPTN 068 analysis. AIDS 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Bowen P, Govender R, Edwards P. Validating survey management scales for AIDS-related knowledge and stigma among construction workers in South Africa. BMC Public Health 2016;16:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Smith JS, Robinson NJ. Age-specific prevalence of infection with herpes simplex virus types 2 and 1: a global review. J Infect Dis 2002;186 Suppl:S3–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Yuan Y, MacKinnon DP. Bayesian Mediation Analysis. Psychol Methods 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Muth B, Asparouhov T. Bayesian SEM : A more flexible representation of substantive theory. Psychol Methods 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Muthén B, Asparouhov T. Causal Effects in Mediation Modeling: An Introduction With Applications to Latent Variables. Struct Equ Model 2015;22:12–23. [Google Scholar]

- [38].MacKinnon DP, Fairchild AJ, Fritz MS. Mediation Analysis. Annu Rev Psychol 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Frye M Bright Futures in Malawi’s New Dawn: Educational Aspirations as Assertions of Identity. Am J Sociol 2012;117:1565–624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Cockcroft A, Kunda JL, Kgakole L, et al. Community views of inter-generational sex: findings from focus groups in Botswana, Namibia and Swaziland. Psychol Health Med 2010;15:507–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]