Abstract

Objective

To examine the association between sex and the use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) among adults with arthritis.

Methods

Data from the 2012 National Health Interview Survey on CAM use for adults with arthritis were analyzed. Five different multivariable regression models were used to examine the association between sex and CAM use after adjusting for demographics, socioeconomics, perceived health status, functional limitations, comorbid chronic conditions, body mass index, and personal health practices.

Results

The number of subjects who met the eligibility criteria and were eventually included in the study was 7,919 adults with arthritis. Around half of the study sample reported ever using CAM (n = 4,055), and about 27% (n = 2,016) reported using CAM in the past 12 months. Women have a significantly higher rate of ever utilization of CAM compared to their male counterparts (62.2% vs. 37.8%) as well as CAM use over the past 12 months (66.1% vs. 33.9%). After controlling for other covariates that can potentially affect the use of CAM, women had higher odds of ever using CAM (AOR = 1.68, 95% CI = 1.55–1.81) as well as the CAM use in the past 12 months (AOR = 1.63, 95% CI = 1.49–1.78) compared to men. Functional limitation and multiple comorbidities were associated with CAM use among women.

Conclusions

The utilization rate of CAM among women with arthritis is significantly higher compared to their male counterparts, which highlights the need to screen adults with arthritis, particularly women, for potential drug-CAM interactions. Also, practicing patient-centered care is important, which should allow the patients to discuss the potential benefits and risks of CAM use with their healthcare providers.

1. Introduction

Arthritis is a highly prevalent chronic health condition in the United States (US), which is projected to reach 25% of the US adult population by 2030 [1]. According to the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation Global Burden of Disease project, arthritis is ranked as one of the highest contributors to global disability [2]. Furthermore, arthritis was associated with pain, poor health-related quality of life, and productivity loss based on multiple studies [3, 4]. Therefore, arthritis patients search for different therapies including complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) to alleviate pain and improve their quality of life. CAM therapies are diverse and include practices or products that are not part of conventional medicine [5]. CAM has been accepted and practiced worldwide, including in the US [6, 7].

According to a study that was conducted using nationally representative data of the US population to explore the prevalence of CAM utilization among patients with chronic health conditions, arthritis patients were found to be the highest users of CAM in comparison to other chronic health conditions [8]. It is estimated that around 30–41% of adults with arthritis in the US are CAM users [9–12]. Various modalities of CAM are commonly used for the treatment of arthritis such as homeopathy, acupuncture, naturopathy, chiropractic or osteopathic manipulation, and massage [12–17]. The main predicting factors for CAM use among adults with arthritis were believed to be the lack of effectiveness of conventional therapy [18], joint pain, and poor functional status [12]. However, it is notable that women with arthritis are using CAM more commonly than their male counterparts [9, 11]. In a cross-sectional study of adult patients with arthritis using the 2007 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) data to investigate CAM use, a significant association between CAM use and gender was observed with women reporting higher utilization rate of CAM than their men's counterparts [11]. This was confirmed recently in the Zhang et al.'s studies using the 2012 NHIS data, where higher use of CAM among women was also noted [9, 10]. The higher utilization rate of CAM among women is believed to be due to its perceived benefits in improving the physical and mental wellbeing [10].

However, the extent to which women are using CAM more than their male counterparts among adults with arthritis needs to be explored further in order to understand the specific healthcare needs of each gender. Besides, the factors that influence the utilization of CAM among men and women with arthritis have been examined in a few studies with limited generalizability. Moreover, it is unknown which forms of CAM are most frequently used by women compared to men with arthritis. Thus, we aimed to address this research gap by exploring the extent of CAM utilization and potential factors that influence that utilization among men and women using a nationally representative sample of US adults with arthritis.

2. Methods

2.1. Data Source

The 2012 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) data were used. The NHIS is an annual cross-sectional household interview survey of the noninstitutionalized US adult population. The sampling plan for the 2012 survey follows a multistage probability design permitting a representative sampling of households and noninstitutionalized population. Participants were randomly selected from each identified household [19]. The 2012 NHIS contains the following files: core files (household, family, person, and sample adult) and adult alternative medicine file [19]. The NHIS provide information on demographics, socioeconomic status, functional status, health status, chronic health conditions, and other variables. Chronic health conditions were identified by asking the participants, whether they have ever been told by a doctor or other health professionals that they had a chronic condition. Those who answered “yes” to having chronic condition(s) are then asked the following survey question: “Have you ever been told by a doctor or other health professional that you have some form of arthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, gout, lupus, or fibromyalgia?” [20]. The adult alternative medicine file was used to identify whether the respondent used CAM and the types of CAM used.

2.2. Study Sample

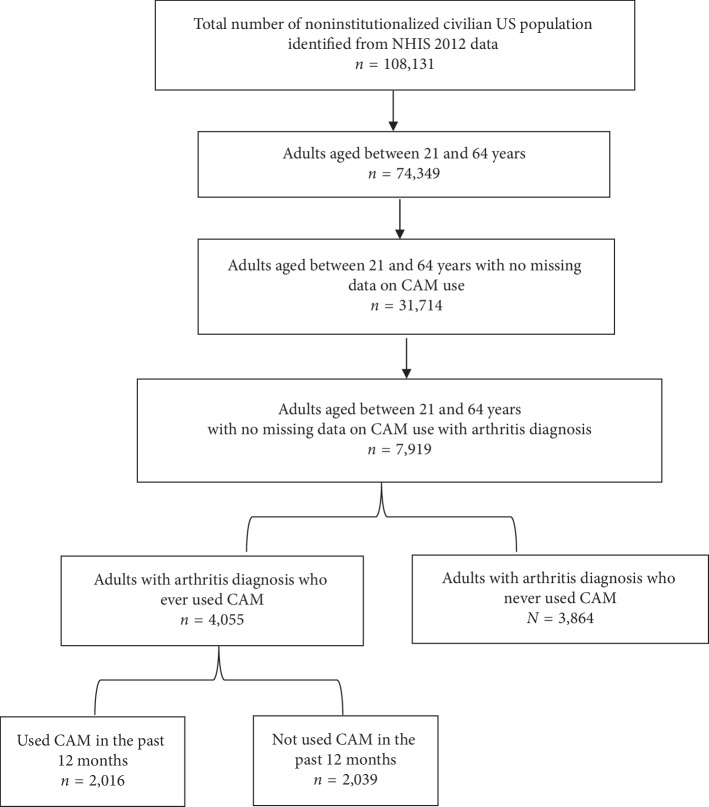

The study sample comprised adults aged >21 years with arthritis. Adults with missing data on CAM use variables were excluded. Figure 1 displays the flow diagram of study sample.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of study sample.

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Dependent Variable

CAM Use. CAM users were categorized into binary variable: (1) have ever used any type of CAM; (2) have never used any type of CAM. The CAM users in the past 12 months were categorized into binary variable: (1) have used any CAM types in the past 12 months; (2) have not used any CAM types in the past 12 months. The reported types of CAM used were classified into three broad categories: (1) alternative medical systems (AMS), which included homeopathy, acupuncture, naturopathy, and Ayurveda; (2) manipulative and body-based therapies (MBBT) which included chiropractic or osteopathic manipulation, massage, Feldenkrais, Alexander technique, Trager psychophysical integration, craniosacral therapy, and Pilates; and (3) mind-body therapies (MBT) which included biofeedback, hypnosis, yoga, tai chi, and qi gong.

2.3.2. Independent Variables

Demographics are composed of sex, age groups in years, race/ethnicity, and the region of residence. Socioeconomic status included education level, marital status, health insurance coverage, and poverty status. Other factors included perceived general health status (excellent, very good, good, fair, and poor), functional limitations, number of comorbid chronic conditions (0, 1, ≥2), and personal health practices (smoking status, alcohol use, and exercise). Body mass index (BMI) was categorized into underweight (<18.5 kg/m2); normal weight (18.5–24.9 kg/m2); overweight (25.0–29.9 kg/m2); and obese (30.0–40.0 kg/m2) [21].

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Frequencies and percentages were used to describe the categorical variables (e.g., age, sex, and marital status). Bivariate analyses were used to examine the sex differences in baseline characteristics and CAM use. Multiple binary logistic regression models were used to examine the adjusted relationships between sex and CAM use in which independent variables were entered in blocks. Adjusted odds ratios (AORs) and their corresponding 95% confidence intervals were used to present the results. Two-sided tests were used in all the statistical analyses, and a p value ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Model I assessed the association between sex and CAM use without adjusting for any independent variables (i.e., confounders). Model II adjusted for demographics (i.e., age, race/ethnicity, and the region of residence). Model III adjusted for socioeconomic status (i.e., education level, marital status, health coverage, and poverty status). Model IV adjusted for perceived health, functional limitations, and the number of chronic conditions. Lastly, model V adjusted for body mass index and personal health practices (smoking status, alcohol use, and exercise). In order to explore factors associated with CAM use among women and men, separate stratified (i.e., subgroup) binary logistic regression analyses among women and men were conducted. The sample adult weight (WTFA_SA) provided in the CAM module was used to account for the US population and missing observations [22]. The analyses controlled for the complex survey design of NHIS using SURVEYFREQ and PROC SURVEYLOGISTIC commands with strata (strat_p), cluster (psu_p), and weight (wtfa_sa) to determine weighted percentages and weighted regression. For the regression analyses, the chi-square goodness-of-fit test was used to assess the model fit. All analyses were performed using Statistical Analysis System Software (SAS 9.4 Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Description of the Study Sample

Table 1 displays the characteristics of adults with arthritis study sample (N = 7,919) and the characteristics of adults with arthritis by sex. There were statistically significant differences between men and women in sociodemographic characteristics, functional limitations, number of comorbid chronic health conditions, body mass index, smoking status, alcohol use, and exercise. For example, a significantly higher percentage of women were poor (14.2% vs. 10.2%, p value < 0.001) and had functional limitation (62.4% vs. 37.6%, p value < 0.001) as compared to men.

Table 1.

Description of the study sample by sex among adults with arthritis.

| Total sample | Women | Men | p value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Wt % | N | Wt % | N | Wt % | ||

| All | 7,919 | 100.0 | 5,002 | 59.7 | 2,917 | 40.3 | |

| Age in years | 0.460 | ||||||

| 22–39 years | 658 | 9.2 | 417 | 58.9 | 241 | 41.1 | |

| 40–49 years | 942 | 13.6 | 585 | 58.6 | 357 | 41.4 | |

| 50–64 years | 2,909 | 38.6 | 1,791 | 58.9 | 1,118 | 41.1 | |

| 65 and older | 3,410 | 38.6 | 2,209 | 61.2 | 1,201 | 38.8 | |

| Race/ethnicity | 0.048 | ||||||

| White | 5,515 | 77.4 | 3,423 | 59.1 | 2,092 | 40.9 | |

| African American | 1,285 | 11.1 | 858 | 61.9 | 427 | 38.1 | |

| Latino | 783 | 8.1 | 518 | 64.4 | 265 | 35.6 | |

| Other race | 336 | 3.4 | 203 | 55.7 | 133 | 44.3 | |

| Region | 0.521 | ||||||

| Northeast | 1,332 | 17.6 | 859 | 61.0 | 473 | 39.0 | |

| Midwest | 1,758 | 24.9 | 1,120 | 60.8 | 638 | 39.2 | |

| South | 3,004 | 37.3 | 1,919 | 59.2 | 1,085 | 40.8 | |

| West | 1,825 | 20.2 | 1,104 | 58.2 | 721 | 41.8 | |

| Marital status | <0.001 | ||||||

| Married | 3,739 | 63.2 | 2,024 | 53.2 | 1,715 | 46.8 | |

| Widow/sep/div | 3,296 | 28.8 | 2,419 | 73.9 | 877 | 26.1 | |

| Never married | 869 | 8.0 | 550 | 60.1 | 319 | 39.9 | |

| Education level | 0.295 | ||||||

| LT high school | 1,452 | 15.3 | 935 | 62.3 | 517 | 37.7 | |

| High school | 2,291 | 29.6 | 1,428 | 59.4 | 863 | 40.6 | |

| GT high school | 4,150 | 55.1 | 2,623 | 59.2 | 1,527 | 40.8 | |

| Poverty status† | <0.001 | ||||||

| Poor | 1,293 | 11.8 | 934 | 68.1 | 359 | 31.9 | |

| Near poor | 1,565 | 16.4 | 1,026 | 63.0 | 539 | 37.0 | |

| Middle income | 2,029 | 26.7 | 1,238 | 58.8 | 791 | 41.2 | |

| High income | 2,107 | 32.9 | 1,186 | 54.2 | 921 | 45.8 | |

| Missing | 925 | 12.1 | 618 | 64.3 | 307 | 35.7 | |

| Insurance | 0.483 | ||||||

| Insured | 7,211 | 91.5 | 4,576 | 59.9 | 2,635 | 40.1 | |

| Uninsured | 690 | 8.5 | 414 | 58.2 | 276 | 41.8 | |

| General health | 0.186 | ||||||

| Excellent | 821 | 11.3 | 507 | 55.8 | 314 | 44.2 | |

| Very good | 1,991 | 27.2 | 1,243 | 59.7 | 748 | 40.3 | |

| Good | 2,655 | 33.6 | 1,676 | 59.8 | 979 | 40.2 | |

| Fair | 1,750 | 19.7 | 1,106 | 60.0 | 644 | 40.0 | |

| Poor | 700 | 8.2 | 469 | 64.0 | 231 | 36.0 | |

| Functional limitation | <0.001 | ||||||

| Yes | 5,896 | 72.3 | 3,856 | 62.4 | 2,040 | 37.6 | |

| No | 2,017 | 27.7 | 1,143 | 52.6 | 874 | 47.4 | |

| #Comorbid conditions | 0.618 | ||||||

| 0 | 1,036 | 14.2 | 626 | 57.9 | 410 | 42.1 | |

| 1 | 1,602 | 21.2 | 1,007 | 60.4 | 595 | 39.6 | |

| >=2 | 5,281 | 64.5 | 3,369 | 59.9 | 1,912 | 40.1 | |

| Body mass index | <0.001 | ||||||

| Underweight | 113 | 1.2 | 97 | 87.5 | 16 | 12.5 | |

| Normal weight | 1,929 | 23.3 | 1,312 | 66.8 | 617 | 33.2 | |

| Overweight | 2,628 | 33.8 | 1,465 | 51.7 | 1,163 | 48.3 | |

| Obese | 2,994 | 38.0 | 1,893 | 58.4 | 1,101 | 41.6 | |

| Missing | 255 | 3.7 | 235 | 93.5 | 20 | 6.5 | |

| Smoking status | <0.001 | ||||||

| Never smoke | 3,850 | 48.2 | 2,743 | 67.5 | 1,107 | 32.5 | |

| Past smoker | 2,587 | 34.0 | 1,377 | 50.0 | 1,210 | 50.0 | |

| Current smoker | 1,471 | 17.8 | 874 | 56.9 | 597 | 43.1 | |

| Alcohol drinking | <0.001 | ||||||

| Light/abstainer | 1,587 | 17.4 | 1,290 | 79.6 | 297 | 20.4 | |

| Former drinker | 3,141 | 39.4 | 2,037 | 62.5 | 1,104 | 37.5 | |

| Current drinker | 3,134 | 42.7 | 1,640 | 49.2 | 1,494 | 50.8 | |

| Missing | 57 | 0.6 | 35 | 50.1 | 22 | 49.9 | |

| Exercise | <0.001 | ||||||

| Daily | 427 | 5.3 | 230 | 49.0 | 197 | 51.0 | |

| Weekly | 1,677 | 23.3 | 941 | 52.2 | 736 | 47.8 | |

| Monthly/yearly | 5,350 | 65.8 | 3,509 | 62.9 | 1,841 | 37.1 | |

| Unable | 418 | 4.8 | 296 | 65.5 | 122 | 34.5 | |

| Missing | 47 | 0.7 | 26 | 52.1 | 21 | 47.9 | |

CAM use was based on adults, age over 21 years, who had arthritis. p values represent significant sex differences in baseline characteristics based on chi-square tests. Missing indicators for alcohol use, exercise, body mass index, and poverty status were presented in the table. Missing data for martial status (n = 15); education level (n = 26); insurance (n = 18); perceived health (n = 2); functional limitations (n = 6); and smoking (n = 11). †Poor (<100% federal poverty line); near poor (100% to <200%); middle income (200% to <400%); and high income (≥400%). GT: greater than; LT: less than; Wt: weighted; #: number of chronic conditions; widow/sep/div: widowed, separated, and divorced.

3.2. CAM Use in the Study Sample

Around half of the study sample reported ever using CAM in general; however, only 26.7% of the study sample reported using CAM in the past 12 months (Table 2). The MBBT was reported to be the most commonly used CAM (20.8%) followed by MBT (8.9%) and AMS (5.6%) in the past 12 months. Chiropractic manipulation and osteopathic manipulation were most commonly used by the study sample (12%) followed by massage (11.6%) and yoga practice (7.2%).

Table 2.

Number and weighted percent of complementary and alternative medicine use by sex among adults with arthritis.

| Total sample | Female | Male | p value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Wt % | N | Wt % | N | Wt % | ||

| All | 7,919 | 100 | 5,002 | 59.7 | 2,917 | 40.3 | |

| Any CAM use | <0.001 | ||||||

| Any CAM ever | 4,055 | 53.6 | 2,650 | 62.2 | 1,405 | 37.8 | |

| No CAM ever | 3,864 | 46.4 | 2,352 | 56.8 | 1,512 | 43.2 | |

| CAM use past 12 months | <0.001 | ||||||

| CAM past 12 months | 2,016 | 26.7 | 1,390 | 66.1 | 626 | 33.9 | |

| No CAM past 12 months | 2,039 | 26.9 | 1,260 | 58.4 | 779 | 41.6 | |

| No CAM ever | 3,864 | 46.4 | 2,352 | 56.8 | 1,512 | 43.2 | |

| Alternative medical system | 0.002 | ||||||

| AMS past 12 months | 451 | 5.6 | 337 | 71.7 | 114 | 28.3 | |

| No AMS past 12 months | 7,446 | 94.4 | 4,648 | 59 | 2,798 | 41 | |

| Manipulative and body-based | 0.003 | ||||||

| MBBT past 12 months | 1,541 | 20.8 | 1,039 | 64.1 | 502 | 35.9 | |

| No MBBT past 12 months | 6,362 | 79.2 | 3,952 | 58.6 | 2,410 | 41.4 | |

| Mind-body therapy | <0.001 | ||||||

| MBT past 12 months | 670 | 8.9 | 521 | 77.5 | 149 | 22.5 | |

| No MBT past 12 months | 7,224 | 91.1 | 4,465 | 58 | 2,759 | 42 | |

| Type of CAM used past 12 months | |||||||

| Homeopathy | 199 | 2.7 | 154 | 71.7 | 45 | 28.3 | 0.016 |

| Acupuncture | 209 | 2.5 | 154 | 70.1 | 55 | 29.9 | 0.011 |

| Naturopathy | 82 | 1 | 63 | 78.7 | 19 | 21.3 | 0.004 |

| Craniosacral | 41 | 0.4 | 34 | 86 | 7 | 14 | 9.95 |

| Ayurveda | 23 | 0.3 | 19 | 83.2 | 4 | 16.8 | 0.049 |

| Chiropractic/osteopathic | 925 | 12.1 | 601 | 60.9 | 324 | 39.1 | 0.552 |

| Massage | 864 | 11.6 | 609 | 67.9 | 255 | 32.1 | <0.001 |

| Feldenkrais | 5 | 0 | 3 | 71.8 | 2 | 28.2 | 0.652 |

| Alexander Tech | 9 | 0.1 | 4 | 51 | 5 | 49 | 0.636 |

| Trager psychophysical | 3 | 0 | 2 | 91.7 | 1 | 8.3 | 0.073 |

| Pilates | 116 | 1.5 | 97 | 86.5 | 19 | 13.5 | <0.001 |

| Biofeedback | 48 | 0.8 | 36 | 79.7 | 12 | 20.3 | 0.014 |

| Hypnosis | 26 | 0.4 | 20 | 65.9 | 6 | 34.1 | 0.658 |

| Yoga practice | 532 | 7.2 | 429 | 81 | 103 | 19 | <0.001 |

| Tai chi | 142 | 1.7 | 98 | 67.9 | 44 | 32.1 | 0.177 |

| Qi gong | 45 | 0.5 | 31 | 68.4 | 14 | 31.6 | 0.34 |

CAM use was based on 7,919 adults, age over 21 years, who had arthritis, and CAM use in the past 12 months was based on 4,055 CAM users. p values represent significant sex differences by complementary alternative medicine use based on chi-square tests. AMS: alternative medical system; CAM: complementary alternative medicine; MBBT: manipulative and body-based therapies; MBT: mind-body therapy; Wt: weighted.

3.3. Sex Differences in CAM Use

Table 2 shows the rate of CAM utilization by both men and women with arthritis across different variables. As compared to men, a significantly higher percentage of women reported using CAM at least once (66.2% vs. 37.8%), and 66.1% of women compared to 33.9% of men reported using CAM in the past 12 months. Even among the different types of CAM used in the past 12 months (AMS, MBBT, and MBT), women had a significantly higher percentage of use compared to men. Also, a significantly higher percentage of women were using homeopathy, acupuncture, naturopathy, massage, Pilates, biofeedback, and yoga as compared to men.

3.4. Sex Differences in CAM Use from Adjusted Analyses

Adjusted odds ratios (AORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) on CAM use are displayed in Table 3. The odds of ever using CAM are significantly higher among women compared to men (OR = 1.24, 95% CI: 1.11–1.40). Also, the odds of using CAM in the past 12 months are significantly higher among women compared to men (OR = 1.40, 95% CI: 1.19–1.63) as shown in model I. This relationship remained significant even after controlling for a myriad of covariates as shown in models II–V (Table 3).

Table 3.

Adjusted odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals of women among adults with arthritis from logistic regressions on CAM use and CAM use in the past 12 months according to 2012 National Health Interview Survey.

| Ever used CAM (N = 4,055) | CAM use past 12 months (N = 3,864) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AOR | 95% CI | p value | AOR | 95% CI | p value | |

| Ref = (nonusers of CAM) | Ref = (nonusers of CAM in past 12 months) | |||||

| Model I, unadjusted | ||||||

| Women | 1.24 | [1.11, 1.40] | <0.001 | 1.40 | [1.19, 1.63] | <0.001 |

| Men (ref) | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Model II, adjusted for demographics | ||||||

| Women | 1.30 | [1.16, 1.46] | <0.001 | 1.41 | [1.21, 1.66] | <0.001 |

| Men (ref) | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Model III, adjusted for demographics and socioeconomics | ||||||

| Women | 1.38 | [1.22, 1.57] | <0.001 | 1.47 | [1.25, 1.73] | <0.001 |

| Men (ref) | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Model IV, adjusted for demographics, socioeconomics, perceived general health status, functional limitations, number of comorbid chronic health conditions | ||||||

| Women | 1.37 | [1.20, 1.55] | <0.001 | 1.47 | [1.25, 1.73] | <0.001 |

| Men (ref) | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Model V, adjusted for demographics, socioeconomics, perceived general health status, functional limitations, number of comorbid chronic health conditions, body mass index, smoking status, alcohol use, exercise. | ||||||

| Women | 1.54 | [1.35, 1.75] | <0.001 | 1.50 | [1.26, 1.78] | <0.001 |

| Men (ref) | ||||||

Logistic regression on CAM use was based on adults, age over 21 years, who had arthritis. Logistic regression on CAM use in the past 12 months was based on 4,055 CAM users. p values represent significant sex differences based on logistic regressions on CAM use and CAM use in the past 12 months after controlling for demographic characteristics, socioeconomic status, perceived general health status, functional limitations, number of comorbid chronic health conditions, body mass index, smoking status, alcohol use, and exercise. AOR: adjusted odds ratios; CI: confidence interval; CAM: complementary alternative medicine; ref: reference group.

3.5. Sex Differences in Factors Affecting CAM Use

Men and women with functional limitations have higher odds to ever use CAM compared to those without functional limitation (AOR = 1.38, 95% CI = 1.09, 1.75 for women) (AOR = 1.39, 95% CI = 1.12, 1.73 for men) (Table 4). The number of chronic conditions was associated with ever using CAM among women but not men (AOR = 1.76, 95% CI = 1.33–2.33). Married men, but not women, had significantly lower odds of ever using CAM compared to their never married counterparts (AOR = 0.51, 95% CI = 0.37–0.71). Women, but not men, from the Northeast and Midwest had significantly lower odds of ever using CAM compared to their counterparts from the West (AOR = 0.47, 95% CI = 0.36–0.62; and AOR = 0.68, 95% CI = 0.53–0.87, respectively). Middle-income women, but not men, had significantly lower odds of using CAM compared to their high-income counterparts (AOR = 0.69, 95% CI = 0.55–0.87). Currently smoking women, but not men, had significantly lower odds of ever using CAM compared to their never-smoker counterparts (AOR = 0.69, 95% CI = 0.55–0.87). Current and past drinking women, but not men, had higher odds of ever using CAM compared to their light/abstaining alcohol drinking women (AOR = 1.44, 95% CI = 1.16–1.79; AOR = 1.87, 95% CI = 1.49–2.34, respectively). Moreover, women but not men, who exercise on a monthly or yearly basis as well as those who are unable to exercise had significantly lower odds of ever using CAM compared to their counterparts who exercise on a weekly basis (AOR = 0.51, 95% CI = 0.40–0.65; and, AOR = 0.33, 95% CI = 0.21–0.52, respectively). Only women, but not men, from the South as well as those with low income, underweight, and exercise on a monthly or yearly basis or unable to exercise at all had significantly lower odds of using CAM in the past 12 months compared to their counterparts who are from the West, with high income, normal weight, and exercise on a weekly basis as shown in Table 5.

Table 4.

Factors affecting ever used CAM for men and women adjusted odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals from logistic regressions according to 2012 National Health Interview Survey.

| Women | Men | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AOR | 95% CI | p value | AOR | 95% CI | p value | |

| Age group | ||||||

| 22–39 (Ref.) | ||||||

| 40–49 | 0.94 | [0.68, 1.31] | 0.727 | 1.01 | [0.67, 1.53] | 0.966 |

| 50–64 | 0.81 | [0.61, 1.07] | 0.132 | 0.80 | [0.56, 1.13] | 0.208 |

| 65, + | 0.51 | [0.37, 0.71] | <0.0001 | 0.64 | [0.43, 0.95] | 0.025 |

|

| ||||||

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| White (Ref.) | ||||||

| African American | 0.50 | [0.40, 0.62] | <0.0001 | 0.45 | [0.33, 0.61] | <0.0001 |

| Latino | 0.70 | [0.53, 0.92] | 0.011 | 0.60 | [0.42, 0.86] | 0.006 |

| Other | 0.68 | [0.44, 1.06] | 0.088 | 0.60 | [0.36, 1.00] | 0.050 |

|

| ||||||

| Marital status | ||||||

| Never married (Ref.) | ||||||

| Married | 1.07 | [0.81, 1.41] | 0.615 | 1.43 | [1.02, 2.00] | 0.037 |

| Widow/sep/div | 1.08 | [0.83, 1.40] | 0.575 | 1.48 | [1.06, 2.07] | 0.022 |

|

| ||||||

| Education level | ||||||

| GT high school (Ref.) | ||||||

| LT high school | 0.41 | [0.32, 0.52] | <0.0001 | 0.52 | [0.37, 0.71] | <0.0001 |

| High school | 0.55 | [0.45, 0.66] | <0.0001 | 0.72 | [0.57, 0.90] | 0.004 |

|

| ||||||

| Region | ||||||

| West (Ref.) | ||||||

| Northeast | 0.47 | [0.36, 0.62] | <0.0001 | 0.76 | [0.54, 1.08] | 0.122 |

| Midwest | 0.68 | [0.53, 0.87] | 0.0024 | 0.77 | [0.57, 1.04] | 0.084 |

| South | 0.47 | [0.37, 0.61] | <0.0001 | 0.55 | [0.42, 0.72] | <0.0001 |

|

| ||||||

| Poverty status† | ||||||

| High income (Ref.) | ||||||

| Poor | 0.49 | [0.37, 0.66] | <0.0001 | 0.52 | [0.33, 0.82] | 0.005 |

| Near poor | 0.71 | [0.55, 0.93] | 0.012 | 0.63 | [0.46, 0.87] | 0.005 |

| Middle income | 0.69 | [0.55, 0.87] | 0.002 | 0.84 | [0.65, 1.09] | 0.194 |

| Missing | 0.78 | [0.59, 1.04] | 0.096 | 0.71 | [0.51, 0.99] | 0.045 |

|

| ||||||

| Insurance | ||||||

| Insured (Ref.) | ||||||

| Uninsured | 1.12 | [0.83, 1.52] | 0.453 | 1.42 | [0.99, 2.05] | 0.059 |

|

| ||||||

| General health | ||||||

| Excellent (Ref.) | ||||||

| Very good | 1.05 | [0.76, 1.43] | 0.776 | 1.03 | [0.72, 1.46] | 0.871 |

| Good | 1.04 | [0.76, 1.44] | 0.793 | 1.27 | [0.90, 1.79] | 0.175 |

| Fair | 1.01 | [0.69, 1.47] | 0.977 | 1.09 | [0.75, 1.58] | 0.664 |

| Poor | 0.91 | [0.59, 1.39] | 0.651 | 1.58 | [0.96, 2.58] | 0.069 |

|

| ||||||

| Functional limitation | ||||||

| No (Ref.) | ||||||

| Yes | 1.38 | [1.09, 1.75] | 0.008 | 1.39 | [1.12, 1.73] | 0.003 |

|

| ||||||

| #Comorbid conditions | ||||||

| 0 (Ref.) | ||||||

| 1 | 1.21 | [0.90, 1.63] | 0.2139 | 1.06 | [0.77, 1.44] | 0.727 |

| >=2 | 1.76 | [1.33, 2.33] | <0.0001 | 0.96 | [0.71, 1.28] | 0.760 |

|

| ||||||

| Body mass index | ||||||

| Normal weight (Ref.) | ||||||

| Under weight | 1.21 | [0.69, 2.11] | 0.502 | 0.26 | [0.05, 1.25] | 0.093 |

| Over weight | 0.94 | [0.75, 1.17] | 0.554 | 0.86 | [0.67, 1.10] | 0.225 |

| Obese | 0.95 | [0.77, 1.18] | 0.661 | 0.85 | [0.67, 1.09] | 0.210 |

| Missing | 0.75 | [0.49, 1.14] | 0.176 | 1.53 | [0.47, 4.96] | 0.475 |

|

| ||||||

| Smoking status | ||||||

| Never smoke (Ref.) | ||||||

| Past smoker | 1.11 | [0.90, 1.35] | 0.329 | 1.18 | [0.94, 1.47] | 0.153 |

| Current smoker | 0.78 | [0.63, 0.97] | 0.026 | 0.83 | [0.62, 1.12] | 0.223 |

|

| ||||||

| Alcohol drinking | ||||||

| Light/abstainer (Ref.) | ||||||

| Former drinker | 1.44 | [1.16, 1.79] | 0.001 | 1.29 | [0.92, 1.80] | 0.142 |

| Current drinker | 1.87 | [1.49, 2.34] | <0.0001 | 1.19 | [0.83, 1.70] | 0.343 |

| Missing | 0.72 | [0.32, 1.63] | 0.432 | 1.26 | [0.43, 3.68] | 0.673 |

|

| ||||||

| Exercise | ||||||

| Weekly (Ref.) | ||||||

| Daily | 1.07 | [0.69, 1.65] | 0.769 | 1.05 | [0.70, 1.60] | 0.806 |

| Monthly/yearly | 0.51 | [0.40, 0.65] | <0.0001 | 0.90 | [0.70, 1.16] | 0.433 |

| Unable | 0.33 | [0.21, 0.52] | <0.0001 | 0.81 | [0.46, 1.41] | 0.457 |

| Missing | 1.32 | [0.45, 3.90] | 0.612 | 0.32 | [0.10, 1.06] | 0.062 |

Logistic regression on CAM use by sex was based on adults, age over 21 years, who had arthritis. Logistic regression on ever used CAM use was based on 7, 919 observations. p values represent significant group differences based on logistic regressions on CAM use. †Poor (<100% federal poverty line); near poor (100% to <200%); middle income (200% to <400%); and high income (≥400%). AOR: adjusted odds ratios; CI: confidence interval; CAM: complementary alternative medicine; Ref.: reference group; widow/sep/div: widowed, separated, and divorced.

Table 5.

Factors affecting CAM use in the past 12 months for men and women adjusted odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals from logistic regressions according to 2012 National Health Interview Survey.

| Women | Men | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AOR | 95% CI | p value | AOR | 95% CI | p value | |

| Age group | ||||||

| 22–39 (Ref.) | ||||||

| 40–49 | 0.67 | [0.44, 1.04] | 0.074 | 0.62 | [0.34, 1.14] | 0.125 |

| 50–64 | 0.46 | [0.32, 0.66] | <.0001 | 0.48 | [0.27, 0.84] | 0.011 |

| 65, + | 0.34 | [0.23, 0.51] | <.0001 | 0.40 | [0.21, 0.74] | 0.003 |

|

| ||||||

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| White (Ref.) | ||||||

| African American | 0.96 | [0.67, 1.37] | 0.818 | 1.16 | [0.73, 1.83] | 0.527 |

| Latino | 0.86 | [0.60, 1.25] | 0.430 | 1.14 | [0.67, 1.96] | 0.63 |

| Other | 1.69 | [0.97, 2.94] | 0.064 | 1.01 | [0.57, 1.77] | 0.973 |

|

| ||||||

| Marital status | ||||||

| Never married (Ref.) | ||||||

| Married | 0.93 | [0.65, 1.32] | 0.679 | 1.23 | [0.68, 2.22] | 0.489 |

| Widow/sep/div | 1.00 | [0.69, 1.44] | 0.982 | 0.88 | [0.47, 1.65] | 0.689 |

|

| ||||||

| Education level | ||||||

| GT high school (Ref.) | ||||||

| LT high school | 0.65 | [0.44, 0.95] | 0.026 | 0.85 | [0.53, 1.38] | 0.512 |

| High school | 0.84 | [0.66, 1.07] | 0.157 | 0.67 | [0.47, 0.95] | 0.025 |

|

| ||||||

| Region | ||||||

| West (Ref.) | ||||||

| Northeast | 1.17 | [0.86, 1.60] | 0.307 | 1.09 | [0.74, 1.60] | 0.675 |

| Midwest | 0.98 | [0.73, 1.32] | 0.904 | 0.95 | [0.64, 1.40] | 0.785 |

| South | 0.73 | [0.56, 0.94] | 0.014 | 1.02 | [0.71, 1.47] | 0.922 |

|

| ||||||

| Poverty status† | ||||||

| High income (Ref.) | ||||||

| Poor | 0.43 | [0.29, 0.65] | <.0001 | 0.96 | [0.51, 1.84] | 0.909 |

| Near poor | 0.65 | [0.46, 0.91] | 0.012 | 0.95 | [0.56, 1.61] | 0.859 |

| Middle income | 0.65 | [0.48, 0.89] | 0.006 | 0.90 | [0.64, 1.27] | 0.553 |

| Missing | 0.56 | [0.39, 0.81] | 0.002 | 1.16 | [0.69, 1.95] | 0.570 |

|

| ||||||

| Insurance | ||||||

| Insured (Ref.) | ||||||

| Uninsured | 0.98 | [0.67, 1.43] | 0.923 | 0.91 | [0.56, 1.48] | 0.693 |

|

| ||||||

| General health | ||||||

| Excellent (Ref.) | ||||||

| Very good | 0.93 | [0.64, 1.34] | 0.686 | 1.10 | [0.70, 1.74] | 0.669 |

| Good | 0.87 | [0.59, 1.27] | 0.469 | 0.93 | [0.58, 1.51] | 0.774 |

| Fair | 0.83 | [0.53, 1.30] | 0.406 | 1.18 | [0.68, 2.05] | 0.558 |

| Poor | 0.92 | [0.53, 1.57] | 0.7538 | 0.69 | [0.33, 1.41] | 0.305 |

|

| ||||||

| Functional limitation | ||||||

| No (Ref.) | ||||||

| Yes | 0.78 | [0.60, 1.01] | 0.058 | 1.29 | [0.93, 1.78] | 0.129 |

|

| ||||||

| # Comorbid conditions | ||||||

| 0 (Ref.) | ||||||

| 1 | 1.26 | [0.87, 1.83] | 0.227 | 0.98 | [0.62, 1.53] | 0.913 |

| >=2 | 1.33 | [0.92, 1.90] | 0.125 | 0.73 | [0.46, 1.15] | 0.179 |

|

| ||||||

| Body mass index | ||||||

| Normal weight (Ref.) | ||||||

| Underweight | 0.37 | [0.14, 0.94] | 0.038 | 1.24 | [0.16, 9.46] | 0.837 |

| Overweight | 0.83 | [0.63, 1.10] | 0.193 | 0.97 | [0.65, 1.45] | 0.885 |

| Obese | 0.77 | [0.59, 1.02] | 0.072 | 0.92 | [0.58, 1.44] | 0.707 |

| Missing | 0.87 | [0.50, 1.53] | 0.634 | 1.43 | [0.30, 6.74] | 0.653 |

|

| ||||||

| Smoking status | ||||||

| Never smoke (Ref.) | ||||||

| Past smoker | 0.91 | [0.72, 1.17] | 0.474 | 0.97 | [0.68, 1.39] | 0.863 |

| Current smoker | 0.74 | [0.55, 0.99] | 0.043 | 0.58 | [0.38, 0.88] | 0.011 |

|

| ||||||

| Alcohol drinking | ||||||

| Light/abstainer (Ref.) | ||||||

| Former drinker | 1.15 | [0.86, 1.56] | 0.347 | 1.22 | [0.72, 2.06] | 0.454 |

| Current drinker | 1.16 | [0.84, 1.61] | 0.356 | 1.37 | [0.80, 2.36] | 0.249 |

| Missing | 0.51 | [0.09, 2.72] | 0.427 | 0.34 | [0.05, 2.41] | 0.280 |

|

| ||||||

| Exercise | ||||||

| Weekly (Ref.) | ||||||

| Daily | 0.83 | [0.51, 1.37] | 0.471 | 1.49 | [0.88, 2.53] | 0.136 |

| Monthly/yearly | 0.69 | [0.52, 0.93] | 0.015 | 0.74 | [0.52, 1.07] | 0.107 |

| Unable | 0.53 | [0.28, 0.99] | 0.047 | 0.89 | [0.39, 2.04] | 0.785 |

| Missing | 0.59 | [0.15, 2.36] | 0.457 | 0.69 | [0.14, 3.55] | 0.662 |

Logistic regression on CAM use by sex was based on adults, age over 21 years, who had arthritis. Logistic regression on CAM use in the past 12 months was based on 4, 055 CAM users. p values represent significant group differences based on logistic regressions on CAM use in the past 12 months. †Poor ((<100% federal poverty line); near poor (100% to <200%); middle income (200% to <400%); and high income (>400%)). AOR: adjusted odds ratios; CI: confidence Interval; CAM: complementary alternative medicine; Ref.: reference group.

4. Discussion

This study evaluated CAM use among adults with arthritis and provided understanding about the sex differences in CAM use across different variables. Nearly one out of two adults with arthritis reported using CAM which is higher than the rate published from the 2002 NHIS data in which around 41% of adults with arthritis reported using CAM [12]. Wide forms of CAM modalities were used by adults with arthritis in this study, and the most commonly reported type was the manipulative and body-based therapies which include, but not limited to, chiropractic or osteopathic manipulation and massage therapies. The higher rate of these therapies could be due to that these therapies are often covered by health insurance. Subjects with arthritis may use these types of therapies to reduce chronic pain and improve the functional status that accompanies arthritis.

The present study revealed that CAM use was more likely among women compared to men. Female patients with arthritis had higher odds of using CAM compared to their male counterparts despite controlling for a myriad of covariates in all of the performed statistical models, which highlights the strength of female gender in predicting higher utilization rate of CAM regardless of their demographic characteristics, socioeconomic characteristics, functional limitations, and medical characteristics. This finding is consistent with the literature among adults with arthritis [12] as well as adults in the general population [23–25]. A narrative review of 110 published studies has revealed that women had consistently higher rate of CAM use in community-based nonclinical population [24]. The higher utilization rate of CAM among women compared to men with arthritis could be attributable to their variable behavioral tendencies toward seeking any form of healthcare services [26] including visiting CAM providers; this tendency might be amplified when women suffer from arthritis. A study among the general US population reported higher utilization rate of CAM among females compared to their male counterparts mainly due to their positive perceptions about CAM and its impact on health and wellbeing [10].

This study has identified several factors that are associated with CAM use. Subgroup analyses revealed that poverty status, as well as education level, were significant factors for CAM use among men and women and adults with arthritis who were poor or had a lower education level were less likely to use CAM. This is consistent with other published studies among adults with arthritis as well as adults in the general population [10, 23, 24, 27]. Further, women who have two or more coexisting chronic conditions were more likely to use CAM. A review of health factors associated with CAM use revealed that CAM users tend to have more than one medical condition [24]. Besides, the functional limitation was a significant factor that affects CAM use among both men and women. In fact, poor functional status is one of the factors that influenced patients with arthritis decision of using CAM therapy [12]. Moreover, this study highlighted differences in the utilization of CAM among women themselves based on their ethnicity, weight, geographic location, and marital status, something that deserves further research to understand the main factors that have resulted in these differences.

Previously published research has found that the integration of CAM modalities and conventional treatments helps to improve the overall health of adults with arthritis [28, 29]. However, there is still inconsistency regarding the clinical efficacy and insufficient data about the safety of CAM modalities for arthritis due to the lack of well-designed clinical trials [13–16]. For instance, a systematic review of forty-three studies has evaluated the safety and efficacy of acupuncture for arthritis. The investigators concluded that acupuncture is beneficial to be used in rheumatoid arthritis to improve function and quality of life; however, there is still contradiction evidence for its clinical efficacy [29]. Therefore, adults with arthritis should use alternative therapies with caution. Besides, healthcare providers should be aware of the common CAM modalities, and also, they should discuss the possible benefits and harms of CAM use with their patients. In addition, different educational interventions customized based on the patients' response and needs should be created to improve patients' awareness of potential drug-CAM interactions that can render the antiarthritis drugs ineffective [30]. The possibility of adverse drug-CAM interactions is noteworthy especially when we know that approximately two-thirds of participants in this study had two or more chronic medical conditions, which increase their likelihood to use multiple medications leading to a higher risk of adverse drug-CAM interactions. This was reported in a study that assessed the prevalence of CAM use among adult patients with arthritis in Lebanon and found that 23% of the surveyed patients used CAM in addition to their prescription medications and around 24% sought medical care owing to potential drug-CAM side effects [31].

This study contributes to the wide literature on the use of CAM among adults with arthritis and includes a wide range of CAM modalities. It has also evaluated the gender disparities in CAM use after controlling for a comprehensive list of factors that affect CAM use. Findings of this study can be generalized to the US population. Further research should investigate whether the higher rate of CAM uses among women is due to inadequate access to healthcare, failure of women to adhere to their conventional treatments, or the inability of conventional medicine to adequately relieve arthritis. This study has some limitations. All measures were self-reported and therefore subject to recall bias. Other confounders such as the severity of arthritis-related pain, attitudes, and beliefs towards CAM use were not controlled for in the analysis because they were not assessed by the NHIS survey.

5. Conclusions

The utilization rate of CAM among women with arthritis is significantly higher compared to their male counterparts, which highlights the need to screen women with arthritis in particular for potential drug-CAM interactions. Also, the findings suggested that rheumatologists and other healthcare providers should be familiar of the most commonly used CAM modalities among women with arthritis and should discuss the possible benefits and harms of CAM use with their patients.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge financial support from the Researchers Supporting Project number (RSP-2019/16), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Abbreviations

- CAM:

Complementary and alternative medicine

- US:

United States

- NHIS:

National Health Interview Survey

- AMS:

Alternative medical systems

- MBBT:

Manipulative and body-based therapies

- MBT:

Mind-body therapies

- BMI:

Body mass index

- AORS:

Adjusted odds ratios

- CI:

Confidence intervals.

Data Availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the 2012 NHIS and openly made available from the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) or the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) at https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/nhis_2012_data_release.htm.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

Authors' Contributions

Dr.Monira Alwhaibi, Dr.Yazed AlRuthia, and Dr.Abdulkarim Meraya have contributed in study designing, writing the manuscript, analysis, interpretation of the results, revising the manuscript content, and approval of the final version of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Hootman J. M., Helmick C. G. Projections of US prevalence of arthritis and associated activity limitations. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2006;54(1):226–229. doi: 10.1002/art.21562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cross M., Smith E., Hoy D., et al. The global burden of rheumatoid arthritis: estimates from the global burden of disease 2010 study. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2014;73(7):1316–1322. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burton W., Morrison A., Maclean R., Ruderman E. Systematic review of studies of productivity loss due to rheumatoid arthritis. Occupational Medicine. 2005;56(1):18–27. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqi171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matcham F., Scott I. C., Rayner L., et al. The impact of rheumatoid arthritis on quality-of-life assessed using the SF-36: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2014;44(2):123–130. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2014.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH) Complementary and alternative medicine. JAMA. 2000;284(20):2649. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.20.2649-jbk1122-2-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fan A. Y., Faggert S. Distribution of licensed acupuncturists and educational institutions in the United States in early 2015. Journal of Integrative Medicine. 2018;16(1):1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.joim.2017.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eisenberg D. M., Cohen M. H., Hrbek A., et al. Credentialing complementary and alternative medical providers. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2002;137(12):965–973. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-12-200212170-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saydah S. H., Eberhardt M. S. Use of complementary and alternative medicine among adults with chronic diseases: United States 2002. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 2006;12(8):805–812. doi: 10.1089/acm.2006.12.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang Y., Dennis J. A., Bishop F. L., et al. Complementary and alternative medicine use by us adults with self-reported doctor-diagnosed arthritis: results from the 2012 national health interview survey. PM&R. 2019;11(10):1059–1069. doi: 10.1002/pmrj.12124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang Y., Leach M. J., Hall H., et al. Differences between male and female consumers of complementary and alternative medicine in a national US population: a secondary analysis of 2012 NIHS data. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2015;2015:10. doi: 10.1155/2015/413173.413173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mbizo J., Okafor A., Sutton M. A., Burkhart E. N., Stone L. M. Complementary and alternative medicine use by normal weight, overweight, and obese patients with arthritis or other musculoskeletal diseases. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 2016;22(3):227–236. doi: 10.1089/acm.2014.0390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Quandt S. A., Chen H., Grzywacz J. G., Bell R. A., Lang W., Arcury T. A. Use of complementary and alternative medicine by persons with arthritis: results of the National Health Interview Survey. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2005;53(5):748–755. doi: 10.1002/art.21443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Efthimiou P., Kukar M. Complementary and alternative medicine use in rheumatoid arthritis: proposed mechanism of action and efficacy of commonly used modalities. Rheumatology International. 2010;30(5):571–586. doi: 10.1007/s00296-009-1206-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dunn J. M., Wilkinson J. M. Naturopathic management of rheumatoid arthritis. Modern Rheumatology. 2005;15(2):87–90. doi: 10.3109/pl00021706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Long L., Ernst E. Homeopathic remedies for the treatment of osteoarthritis: a systematic review. British Homeopathic Journal. 2001;90(1):37–43. doi: 10.1054/homp.1999.0449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chopra A., Saluja M., Tillu G. Ayurveda-modern medicine interface: a critical appraisal of studies of ayurvedic medicines to treat osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis. Journal of Ayurveda and Integrative Medicine. 2010;1(3):p. 190. doi: 10.4103/0975-9476.72620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Park K. M., Cho T. H. Therapeutic effect of acupuncture point injection with placental extract in knee osteoarthritis. Journal of Integrative Medicine. 2017;15(2):135–141. doi: 10.1016/s2095-4964(17)60316-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khan M. U., Jamshed S. Q., Ahmad A., Bidin M. A, Siddiqui M. J, Al-Shami A. K. Use of complementary and alternative medicine among osteoarthritic patients: a review. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research: JCDR. 2016;10(2):JE01–6. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2016/15211.7169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Center for Health Statistics. National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) Survey Description 2012. Hyattsville, MD, USA: National Center for Health Statistics; 2012. ftp://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/Health_Statistics/NCHS/Dataset_Documentation/NHIS/2012/srvydesc.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Center for Health Statistics. NHIS Data, Questionnaires and Related Documentation. Hyattsville, MD, USA: National Center for Health Statistics; https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/data-questionnaires-documentation.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Janssen I., Katzmarzyk P. T., Ross R. Waist circumference and not body mass index explains obesity-related health risk. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2004;79(3):379–384. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/79.3.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) National Health Interview Survey, 2012 Data Release, Adult Alternative Medicine, Variable Frequencies. National Health Interview Survey (NHIS); 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/nhis_2012_data_release.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alwhaibi M., Sambamoorthi U. Sex differences in the use of complementary and alternative medicine among adults with multiple chronic conditions. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2016;2016:8. doi: 10.1155/2016/2067095.2067095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bishop F. L., Lewith G. T. Who uses CAM? A narrative review of demographic characteristics and health factors associated with CAM use. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2010;7(1):11–28. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nen023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Herman C. J., Allen P., Prasad A., et al. Peer reviewed: use of complementary therapies among primary care clinic patients with arthritis. Preventing Chronic Disease. 2004;1(4):1–15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bertakis K. D., Azari R., Helms L. J., Callahan E. J, Robbins J. A. Gender differences in the utilization of health care services. Journal of Family Practice. 2000;49(2):147–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fautrel B., Adam V., St-Pierre Y., Joseph L, Clarke A. E, Penrod J. R. Use of complementary and alternative therapies by patients self-reporting arthritis or rheumatism: results from a nationwide canadian survey. The Journal of Rheumatology. 2002;29(11):2435–2441. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Perlman A., Fogerite S. G., Glass O., et al. Efficacy and safety of massage for osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized clinical trial. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2019;34(3):379–386. doi: 10.1007/s11606-018-4763-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chou P.-C., Chu H.-Y. Clinical efficacy of acupuncture on rheumatoid arthritis and associated mechanisms: a systemic review. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2018;2018:21. doi: 10.1155/2018/8596918.8596918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Elmer G. W., Lafferty W. E., Tyree P. T., Lind B. K. Potential interactions between complementary/alternative products and conventional medicines in a medicare population. Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 2007;41(10):1617–1624. doi: 10.1345/aph.1k221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alaaeddine N., Okais J., Ballane L., et al. Use of complementary and alternative therapy among patients with rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2012;21(21-22):3198–3204. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2012.04169.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the 2012 NHIS and openly made available from the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) or the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) at https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/nhis_2012_data_release.htm.