Abstract

Background

Ulcerative colitis (UC) patients have an increased risk for the development of colorectal cancer (CRC). Our aim was to assess the risk of CRC in UC patients compared with disease extent, disease duration, and geographic variation.

Methods

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, we searched PubMed, scientific meetings, and the bibliographies of identified articles, with English language restrictions for studies published from 1988 to 2018, and assessed the risk of CRC in UC patients. Patients with Crohn's disease, family history of CRC, and colorectal adenomatous polyp (CAP) were excluded from this research. The study was registered with PROSPERO, number CRD42018102213.

Findings

We included 58 studies that included 267566 UC patients. Extensive UC and left-sided UC had a higher risk of CRC than proctitis UC. Geography also played a role in UC-associated CRC development. The time of malignant transformation in Asian UC patients started after 10-20 years of this disease duration. North American UC-associated CRC patients significantly increased in more than 30 years of this disease duration.

Conclusion

In a systematic review of the literature, we found that disease extent, disease duration, and geography were strong, independent risk factors in UC-associated CRC development.

1. Introduction

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is an idiopathic, chronic inflammatory disorder of the colonic mucosa, which started in the rectum and generally extended proximally in a continuous manner through part of, or the entire, colon [1]. The clinical course was unpredictable, marked by alternating periods of exacerbation and remission [2]. UC-associated colorectal cancer (CRC) represented a fraction of CRC cases, accounted for up to 5% of all CRC [3]. In contrast to sporadic CRC, UC-associated CRC did not follow the typical “adenoma-carcinoma” sequences [1]. Due to limited understanding of the natural history of UC-associated CRC, the knowledge concerning the CRC risk in UC patients was still inadequate.

The first retrospective analysis on the risk of CRC in UC was published in 1988. In this publication, the overall incidence of CRC in UC was reported as 4.25% [4]. Recent mounting evidences from numerous countries suggested that the CRC standardised incidence ratio (SIR) in UC may differ based on disease duration and geographic variation. For example, the 10-year cumulative probability of cancer after the diagnosis of UC was 4.9%, not having a higher risk of cancer than an age-and sex-matched general population [5]. However, there was no synthesis of risk factors associated with disease extent, disease duration, and geographic variation. Therefore, we did a systematic review and meta-analysis to investigate the risk of CRC in UC patients compared with disease extent, disease duration, and geographic variation.

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

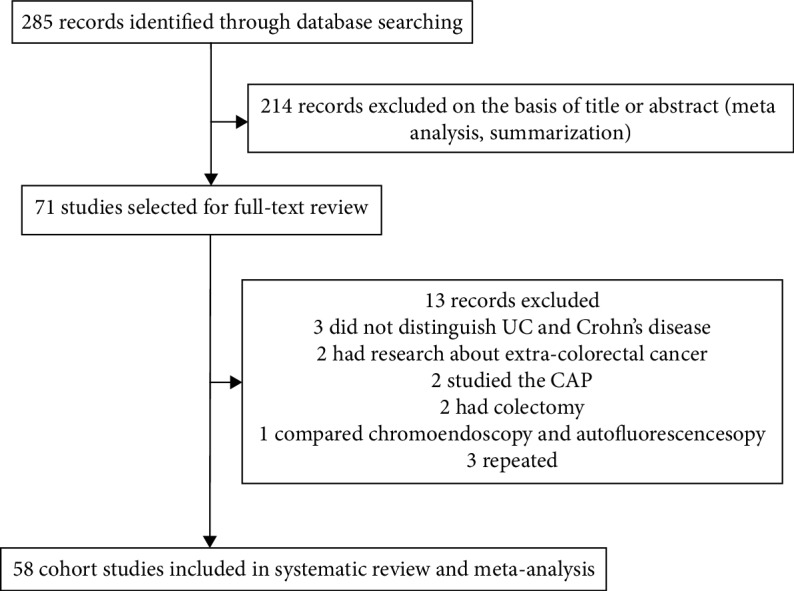

We did a comprehensive literature research according to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions and followed the PRISMA and MOOSE guidelines for the reporting of meta-analyses. We searched PubMed, scientific meetings, and the bibliographies of identified articles, with English language restrictions for studies published from 1988 to Dec. 2018. All relevant articles included UC-associated CRC patients. Medical subject heading or keywords used in the search included the following: “Ulcerative Colitis” or “Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD)” or “Colorectal Cancer” or “Colorectal Neoplasia”. The full search strategies used for each database were described in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of study selection.

Articles were eligible for inclusion if they reported the UC patients were associated with CRC in terms of the sample size. We included incidence rates in our analyses as an indirect method of adjustment for disease extent, disease duration, and geography.

Two authors (Qing Zhou and Zhao-Feng Shen) independently screened the title and abstract according to these eligibility criteria, screened data extraction, and did quality evaluation. When the evaluation result was not consistent, they consulted other researchers to further resolve differences through consultation according to the literature on the raw data. When the title and abstract met the requirements of the literature, the full text was retrieved for data extraction. NoteExpress 2.0 was adopted to manage the literature, and the repeated literature was removed. The inclusion of the literature was checked according to the abovementioned inclusion criteria, and the related references were traced.

2.2. Exclusion Criteria

We excluded the studies in this meta-analysis that met the following inclusion criteria:

The literature type did not belong to the category of UC-associated CRC

The literature type was a meta-analysis or summarization

The literature type data was incomplete (UC and Crohn's disease could not be distinguished effectively) and the additional data could not be further obtained

The literature type outcome evaluation index was not CRC

The literature type was Crohn's disease, CAP, family history of CRC, or colectomy for UC

The literature type was repeated or republished

2.3. Data Extraction

Two researchers (Qing Zhou and Zhao-Feng Shen) independently extracted relevant information from all eligible studies using a predefined data extraction form: author, publication year, sample size, age, country, gender, disease extent, and disease duration. Diagnosis and confirmation of UC and CRC were according to the criteria [6]. For missing data, the researchers tried to contact the original literature author by e-mail to obtain relevant data. Data that cannot be obtained was converted according to the relevant requirements of the Cochrane evaluation manual (such as the calculation of standard deviation in continuous data).

2.4. Outcomes

The primary outcome measure was the incidence of CRC in UC patients, reported as SIR. We included SIR in our analyses as a direct method of adjustment. No restrictions about publication year, sample size, age, country, gender, disease extent, and disease duration were applied.

The secondary outcomes were measuring the incidence of CRC in UC patients from disease extent, disease duration, geographic variation, and literature reporting time.

2.5. Analysis

We used random-effects meta-analysis to assess the incidence of CRC in UC patients. To calculate the pooled SIR of CRC, we combined the extracted study-specific estimates and 95% CIs using the DerSimonian-Laird random-effects model.

Publication bias (small-study effects) was examined with visual assessment of the symmetry of a funnel plot, the asymmetry of which will be assessed through Begg-Mazumdar's rank test. Forest plots were made for the prevalence of the outcomes in overall and within groups.

Data manipulation and statistical analyses were undertaken using the R Software (version 3.4.4). All statistical tests, with the exception of the Q statistic, used a two-sided α value of 0.05 for significance.

The study was registered with PROSPERO, number CRD42018102213.

2.6. Role of the Funding Source

This study was supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology of the People's Republic of China (2017YFC1700602), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81573978), and the State Clinical Research of TCM (JDZX2015086).

3. Results

From 285 articles of potential relevance, 71 full-text articles were examined in detail and 58 studies were included in the final analysis; studies which identified 267566 UC patients, published from Nov. 1988 to Dec. 2018, with 2663 patients that reported UC-associated CRC were included in the meta-analysis. The population characteristics and outcomes of the included studies were summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Population and study characteristics.

| Author | Sample size (UC) | Study period | Mean age at diagnosis (UC) | Country | Sample size (CRC) | Mean age at diagnosis (CRC) | Gender | Disease extent | Time of duration (year) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | Extensive | Left-sided | Proctitis | ||||||||

| Hata et al. [7] | 217 | 1979-2001 | 31.4 | Japan | 5 | 46.6 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 15.2 |

| Kim et al. [8] | 7061 | 1970-2005 | 37.9 | Korea | 26 | 49.6 | 8 | 18 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12.7 |

| Gong et al. [9] | 3922 | 1998-2009 | 40 | China | 34 | 57.5 | 14 | 20 | 10 | 12 | 12 | 12.8 |

| Matsuoka et al. [10] | 1274 | 1984-2010 | 30 | Japan | 83 | 52 | 43 | 40 | 66 | 17 | 10 | 22 |

| Zhang et al. [11] | 624 | 2000-2012 | 39 | China | 4 | 54.5 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 15.5 |

| Lee et al. [12] | 2798 | 1989-2013 | 33 | Korea | 18 | 48 | 7 | 11 | 16 | 2 | 0 | 15 |

| Choi et al. [13] | 522 | 2003-2013 | 0 | Korea | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Shi et al. [14] | 1225 | 1981-2013 | 41 | China | 15 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Yoshino et al. [15] | 2137 | 2003-2013 | 0 | Japan | 43 | 53 | 28 | 15 | 34 | 8 | 1 | 13 |

| Wang et al. [16] | 2663 | 1998-2013 | 43.1 | China | 18 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 19.27 |

| Jung et al. [17] | 9785 | 2011-2014 | 0 | Korea | 31 | 0 | 20 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Kishikawa et al. [18] | 289 | 1979-2014 | 33 | Japan | 9 | 49 | 5 | 4 | 28 | 5 | 0 | 16 |

| Bopanna et al. [19] | 1012 | 2004-2015 | 32.1 | India | 20 | 53.25 | 14 | 6 | 16 | 4 | 0 | 18.7 |

| Selinger et al. [20] | 504 | 1977-1992 | 0 | Australia | 24 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 8 | 4 | 0 |

| Gupta et al. [21] | 418 | 1996-1997 | 26.8 | USA | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Jess et al. [22] | 378 | 1940-2001 | 34 | USA | 6 | 50.67 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 13.67 |

| Bitton et al. [23] | 15346 | 1999-2008 | 0 | Canada | 53 | 0 | 37 | 16 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hou et al. [24] | 20949 | 1998-2009 | 0 | USA | 168 | 67 | 97 | 71 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3.6 |

| Ananthakrishnan et al. [25] | 5569 | 1998-2010 | 0 | USA | 126 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Navaneethan et al. [26] | 997 | 1998-2011 | 0 | USA | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Yadav et al. [5] | 462 | 1940-2011 | 35 | USA | 13 | 66 | 6 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 31 |

| Ananthakrishnan et al. [27] | 3546 | 2010-2013 | 0 | USA | 83 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Sonnenberg and Genta [28] | 37043 | 2008-2014 | 49.6 | USA | 54 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hou et al. [29] | 881 | 1999-2014 | 0 | USA | 21 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Bettner et al. [30] | 75 | 1990-2015 | 29 | USA | 1 | 59 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11.1 |

| Gyde et al. [4] | 823 | 1944-1976 | 33.66 | UK/Sweden | 35 | 56.69 | 13 | 22 | 28 | 7 | 0 | 23.03 |

| Moody et al. [31] | 175 | 1972-1981 | 58.4 | UK | 10 | 67 | 6 | 4 | 7 | 3 | 0 | 9.6 |

| Ekbom et al. [32] | 3117 | 1922-1983 | 0 | Sweden | 91 | 0 | 52 | 39 | 35 | 17 | 9 | 0 |

| Lennard-Jones et al. [33] | 401 | 1966-1987 | 29.73 | UK | 22 | 50.05 | 13 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20.31 |

| Löfberg et al. [34] | 72 | 1973-1988 | 0 | Sweden | 1 | 42.25 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Stewtnius et al. [35] | 471 | 1958-1990 | 38.3 | Sweden | 9 | 49.88 | 3 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 1 | 12.22 |

| Biasco et al. [36] | 65 | 1980-1992 | 32.9 | Italy | 4 | 59.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 13 |

| Wandall et al. [37] | 801 | 1973-1993 | 41 | Denmark | 6 | 57.33 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 10.83 |

| Palli et al. [38] | 689 | 1978-1996 | 0 | Italy | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Winther et al. [39] | 1160 | 1962-1997 | 0 | Denmark | 8 | 0 | 6 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Viscido et al. [40] | 2006 | 1964-1997 | 38.5 | Italy | 28 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Goldacre et al. [41] | 6990 | 1963-1999 | 0 | UK | 103 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Lindberg et al. [42] | 90 | 1977-2002 | 0 | Sweden | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Jess et al. [43] | 1437 | 1978-2002 | 0 | Denmark | 15 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hemminki et al. [44] | 27606 | 1964-2004 | 0 | Germany/Sweden | 482 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Katsanos et al. [45] | 182 | 1983-2004 | 51.2 | Greece | 3 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Katsanos et al. [46] | 776 | 1991-2004 | 0 | Netherlands | 7 | 61.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5.4 |

| Jess et al. [47] | 1575 | 1962-2005 | 0 | Denmark | 14 | 0 | 8 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Stolwijk et al. [48] | 293 | 1980-2005 | 33.8 | Netherlands | 23 | 49.2 | 14 | 9 | 22 | 1 | 0 | 10.2 |

| Lakatos et al. [49] | 723 | 2002-2005 | 36 | Hungary | 13 | 51 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 5 | 0 | 19 |

| Cheddani et al. [50] | 474 | 1998-2006 | 69 | France | 8 | 75 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7.4 |

| Manninen et al. [51] | 1254 | 1986-2007 | 34 | Finland | 16 | 47.69 | 14 | 2 | 10 | 6 | 0 | 16.1875 |

| Jess et al. [52] | 32911 | 1979-2008 | 44.9 | Denmark | 268 | 64 | 132 | 136 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 19.1 |

| Gordillo et al. [53] | 403 | 2006-2009 | 42.91 | Spain | 3 | 58.9 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 12.5 |

| Kappelman et al. [54] | 35152 | 1978-2010 | 46.5 | Denmark | 437 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7.8 |

| Choi et al. [55] | 1375 | 2003-2012 | 30 | UK | 88 | 55.5 | 54 | 34 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 25.5 |

| Choi et al. [56] | 987 | 2003-2012 | 30 | UK | 14 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hovde et al. [57] | 519 | 1990-2013 | 0 | Norway | 14 | 0 | 10 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Van den Heuvel et al. [58] | 1644 | 1991-2013 | 45 | Netherlands | 12 | 62.75 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 7 | 1 | 3.42 |

| Nowacki et al. [59] | 434 | 2013-2013 | 45.7 | Germany | 10 | 54.7 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 4 | 0 | 12 |

| Rutegård et al. [60] | 323 | 1977-2014 | 0 | Sweden | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Biancone et al. [61] | 22666 | 2012-2014 | 0 | Italy | 24 | 64 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12 |

| Kekilli et al. [62] | 275 | 1994-2008 | 35.9 | Turkey | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

3.1. Overall Risk of CRC in UC Patients

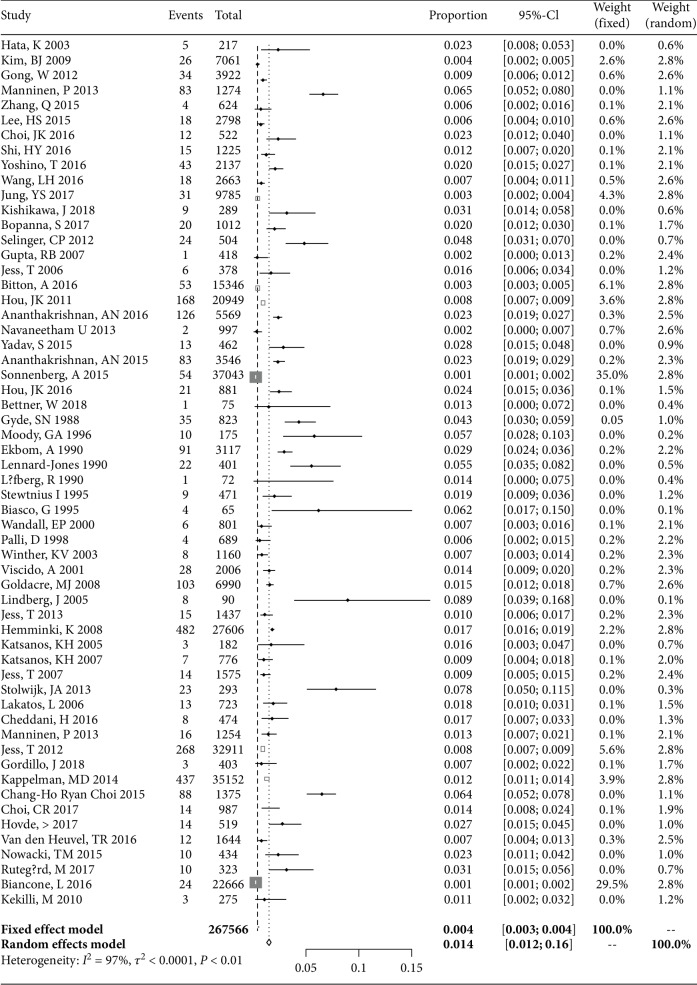

The overall risk of CRC in UC patients among the 58 studies was 1.4% (95% CI: 1.2-1.6; Figure 2). Gender-specific risk estimate for CRC in UC was reported in 30 of the 58 studies and varied from 0.89 (95% CI: 0.56-1.43) to 1.05 (95% CI: 0.68-1.63) in women and men, which has no difference (P = 0.62). Disease extent-specific risk estimates for CRC in UC were reported in 21 of the 58 studies, which show that extensive UC and left-sided UC had a higher risk of CRC (SIR: 1.42, 95% CI: 0.83-2.42; SIR: 0.56, 95% CI: 0.38-0.83) than proctitis UC (SIR: 0.18, 95% CI: 0.01-0.03) (P < 0.01) (Tables 2 and 3).

Figure 2.

Individual and SIRs of CRC risk in UC: a meta-analysis of population-based cohort studies.

Table 2.

Gender-specific risk of CRC in UC patients.

| Gender | Proportion | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Men | 0.0105 | 0.0068-0.0163 |

| Women | 0.0089 | 0.0056-0.0143 |

▲P < 0.05 vs. women; ▲▲P < 0.01 vs. women.

Table 3.

Disease extent risk of CRC in UC patients.

| Extent | Proportion | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Extensive | 0.0142▲▲ | 0.0083-0.0242 |

| Left-sided | 0.0056▲▲ | 0.0038-0.0083 |

| Proctitis | 0.0018 | 0.0010-0.0031 |

▲P < 0.05 vs. proctitis; ▲▲P < 0.01 vs. proctitis.

3.2. Disease Duration Risk of CRC in UC Patients

In the subgroup analysis by disease duration, the incidence of CRC in UC patients rose after 20 years of this disease duration (Table 4).

Table 4.

Disease duration risk of CRC in UC patients.

| Follow-up | Article (n) | Proportion | 95% CI | Weight (random) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-9 years | 11 | 0.007 | 0.005-0.009 | 22.40% |

| 10-20 years | 22 | 0.013 | 0.010-0.016 | 36.60% |

| 21-30 years | 11 | 0.02▲ | 0.014-0.026 | 15.60% |

| More than 30 years | 14 | 0.017▲ | 0.013-0.022 | 25.40% |

▲P < 0.05 vs. 1-9 years; ▲▲P < 0.01 vs. 1-9 years.

3.3. Geographic Variation Risk of CRC in UC Patients

In the subgroup analysis by geographic variation, Oceania has a higher incidence than other continents; however, it has only one article (Tables 1 and 5). In Europe, the risk of CRC in UC patients has no statistical difference in disease duration for 1-9 years, 10-20 years, 21-30 years, or more than 30 years. In Asia, the risk of CRC in UC increased after 10-20 years of this disease duration. In North America, the risk of CRC in UC increased significantly in more than 30 years of this disease duration (Tables 5 and 6).

Table 5.

Geographic variation risk of CRC in UC patients.

| Area | Article (n) | Proportion | 95% CI | Weight (random) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asia | 13 | 0.013 | 0.009-0.017 | 24.90% |

| North America | 11 | 0.011 | 0.007-0.014 | 22.20% |

| Europe | 33 | 0.017 | 0.014-0.020 | 52.20% |

| Oceania | 1 | 0.048▲ | 0.029-0.066 | 0.70% |

▲P < 0.05 vs. Europe; ▲▲P < 0.01 vs. Europe.

Table 6.

Geographic variation in UC patients in different disease durations.

| Area | 1-9 years | 10-20 years | 21-30 years | More than 30 years |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asia | 0.0032 [0.0022; 0.0045] n = 1 |

0.0128 [0.0081; 0.0201]▲ n = 6 |

0.0188 [0.0051; 0.0671]▲ n = 4 |

0.0106 [0.0013; 0.0819]▲ n = 2 |

| North America | 0.0043 [0.0009; 0.0196] n = 4 |

0.0120 [0.0058; 0.0245] n = 5 |

— | 0.0228 [0.0132; 0.0390]▲ n = 2 |

| Europe | 0.0097 [0.0020; 0.0461] n = 6 |

0.0141 [0.0089; 0.0221] n = 10 |

0.0222 [0.0104; 0.0465] n = 7 |

0.0193 [0.0144; 0.0257] n = 10 |

| Oceania | — | 0.048 [0.029; 0.066] n = 1 |

— | — |

▲P < 0.05 vs. 1-9 years; ▲▲P < 0.01 vs. 1-9 years.

Furthermore, we analyzed the CRC incidence in UC patients in each country; we found that Japan, UK, and Austria have the highest incidence, while Canada and Korea have the lowest incidence (Table 7).

Table 7.

CRC incidence in UC patients by country.

| Nation | Article (n) | Proportion | 95% CI | Weight (random) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canada | 1 | 0.003 | 0.003-0.004 | 2.80% |

| Korea | 4 | 0.005 | 0.002-0.007 | 9.30% |

| Spain | 11 | 0.007 | 0.000-0.016 | 1.70% |

| China | 4 | 0.008 | 0.006-0.010 | 9.40% |

| Italy | 4 | 0.008 | 0.000-0.016 | 7.40% |

| Denmark | 6 | 0.009 | 0.007-0.012 | 14.70% |

| Turkey | 1 | 0.011 | 0.000-0.023 | 1.20% |

| Finland | 1 | 0.013 | 0.007-0.019 | 2.10% |

| USA | 10 | 0.013 | 0.008-0.017 | 19.40% |

| Greece | 1 | 0.016 | 0.000-0.035 | 0.70% |

| France | 1 | 0.017 | 0.005-0.028 | 1.30% |

| Germany | 2 | 0.018 | 0.016-0.019 | 3.80% |

| Hungary | 1 | 0.018 | 0.008-0.028 | 1.50% |

| Netherlands | 3 | 0.019 | 0.004-0.035 | 4.80% |

| India | 1 | 0.02 | 0.011-0.028 | 1.70% |

| Norway | 1 | 0.027 | 0.013-0.041 | 1% |

| Sweden | 5 | 0.027 | 0.017-0.036 | 4.50% |

| Japan | 4 | 0.035 | 0.012-0.058 | 4.50% |

| UK | 6 | 0.039 | 0.022-0.055 | 7.50% |

| Austria | 1 | 0.048 | 0.029-0.066 | 0.70% |

3.4. The Literature Reporting Time of CRC Risk in UC Patients

In the subgroup analysis by literature reporting time, we found that the risk of CRC in UC patients was higher in 1988-1995. As the research progresses, the CRC risk in UC was stable and maintained between 1.1% and 1.6% (Table 8).

Table 8.

The literature reporting time in CRC risk in UC patients.

| Reporting time | Article (n) | Proportion | 95% CI | Weight (random) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1988-1995 | 6 | 0.033 | 0.022-0.043 | 5.40% |

| 1996-2000 | 3 | 0.011 | 0.000-0.021 | 4.60% |

| 2001-2005 | 5 | 0.014 | 0.006-0.023 | 6% |

| 2006-2010 | 9 | 0.011 | 0.005-0.016 | 6% |

| 2011-2015 | 17 | 0.016 | 0.013-0.020 | 6% |

| 2016-today | 18 | 0.012 | 0.009-0.015 | 6% |

4. Discussion

UC, an uncontrolled colorectal inflammation, associated with systemic immune dysregulation, which impaired tumor surveillance, might play a role in colorectal carcinogenesis. Unlike the “adenoma-carcinoma sequence” classically described in sporadic CRC, UC-associated CRC arose from a larger field of colorectal mucosa that was “preconditioned” with a mutational burden that conferred an increased propensity for further dysplasia progression, a phenomenon known as “field cancerization” [55], which followed a sequence of genetic alterations “inflammation-dysplasia-carcinoma” [63]. Chronic colorectal inflammation generated extensive damage to epithelial cells that led to increased cell replication and/or direct DNA damage [1], which was known as one risk factor for the occurrence of CRC in UC patients [28].

This study first provided a picture of the incidence rate of UC-associated CRC from disease extent, disease duration, and geographic variation. Results showed that the overall risk of UC-associated CRC was 1.4%, which increased with disease duration. Extensive UC and left-sided UC had a greater risk of CRC than proctitis UC. There was no obvious gender specificity in CRC risk in UC patients. The strength of this study lies in the fact that we chose to focus on the CRC risk in UC patients from geographic variation. Results showed that the Asian and North American UC patients seemed to have a higher CRC risk. The time of malignant transformation in Asian UC patients started after 10-20 years of this disease duration. North American UC-associated CRC patients significantly increased in more than 30 years of this disease duration.

In this study, we can find that UC patient-relevant endpoint, the risk of CRC, has not decreased over the past decade, and the overall CRC incidence was stable from 1996 until today, which stayed around 1.1% to 1.6%. So the management of UC is still complex, and significant gaps in the literature remained regarding how clinicians could identify the risk associated with CRC and enhance the prevention of UC-associated CRC. 5-Aminosalicylate medications (mesalamine or sulfasalazine), the foundational first-line therapy for the induction and maintenance of mild-to-moderate UC, seemed not to protect against the likelihood of carcinogenesis at doses greater than 2.4 grams daily and still needed to be proven [64]. Other medicines, such as thiopurines, reduced the immunosurveillance of malignant cells and impaired control of oncogenic viruses [65]. Prolonged treatment with thiopurines has been shown to determine an increased risk of a broad range of cancers in UC patients [66]. The impact of UC-related drug therapy on CRC development remained a matter of debate, and the potential benefit of surgery should need to be placed in the context of the risks associated with undertaking complex abdominopelvic reconstructive surgery. Therefore, UC-associated CRC rates still remained a challenging problem for UC patients.

At present, the majority of CRC cases (70%) could be explained by an inadequate surveillance procedure before the CRC diagnosis, and CRC is responsible for approximately 15% of deaths due to UC [67]. Therefore, it is not surprising that researchers have focused efforts on surveillance screening as an adjunct therapy to UC patients for CRC occurrence. UC patients need to be accurately evaluated for the risk of CRC according to the disease extent, disease duration, and geography and need to adhere to a surveillance schedule, such as screening colonoscopy, which should be performed every 1 to 3 years, because the malignant changes and the surrounding inflammation often grow flat and multifocal [68].

5. Conclusion

In a systematic review of the literature, we found that the incidence of CRC in UC patients increased with the disease duration. Asian and North American UC patients were more prone to concomitant CRC.

6. Limitations

Our study has limitations. Patients with Crohn's disease, CAP, and a family history of CRC and who have undergone colectomy for UC were not included in this study. Patients with UC associated with extracolorectal malignancies (small intestine, blood systems, lung, thyroid, hepatobiliary, skin, melanoma, urinary bladder, breast, genital tract, and so on) were not included, which greatly reduced the risk of cancer in UC. Moreover, our search had English language restrictions. Articles in languages other than English were not included.

Abbreviations

- UC:

Ulcerative colitis

- CRC:

Colorectal cancer

- IBD:

Inflammatory bowel disease

- SIR:

Standardised incidence ratio

- CAP:

Colorectal adenomatous polyp.

Contributor Information

Yu-gen Chen, Email: chenyg666@126.com.

Hai-bo Chen, Email: haibocheng@njucm.edu.cn.

Shu-tang Han, Email: 317544025@qq.com.

Data Availability

The clinical data supporting this systematic review and meta-analysis are from previously reported studies and datasets, which have been cited. The processed data are available in Table 1 of our manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Authors' Contributions

Qing Zhou and Zhao-Feng Shen independently screened the literature, extracted the data, performed the statistical analysis, cowrote the manuscript, and interpreted the statistical results. Ben-sheng Wu, Cheng-biao Xu, Zhong-qi He, Tuo Chen, Hong-tao Shang, Chao-fan Xie, and Si-yi Huang checked this work again and critically revised the paper. Yu-gen Chen was the project leader for this research and participated in the critical revision of the manuscript. Corresponding authors (Yu-gen Chen, Hai-bo Chen, and Shu-tang Han) had the final responsibility to submit for publication. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript. Qing Zhou and Zhao-Feng Shen are the first two authors who contributed equally to this paper.

References

- 1.Baker K. T., Salk J. J., Brentnall T. A., Risques R. A. Precancer in ulcerative colitis: the role of the field effect and its clinical implications. Carcinogenesis. 2018;39(1):11–20. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgx117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ordás I., Eckmann L., Talamini M., Baumgart D. C., Sandborn W. J. Ulcerative colitis. The Lancet. 2012;380(9853):1606–1619. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60150-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Herszényi L., Barabás L., Miheller P., Tulassay Z. Colorectal cancer in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: the true impact of the risk. Digestive Diseases. 2015;33(1):52–57. doi: 10.1159/000368447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gyde S. N., Prior P., Allan R. N., et al. Colorectal cancer in ulcerative colitis: a cohort study of primary referrals from three centres. Gut. 1988;29(2):206–217. doi: 10.1136/gut.29.2.206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yadav S., Singh S., Harmsen W. S., Edakkanambeth Varayil J., Tremaine W. J., Loftus E. V., Jr. Effect of medications on risk of cancer in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases: a population-based cohort study from Olmsted County, Minnesota. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 2015;90(6):738–746. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gallinger Z. R., Weizman A. V. Colorectal cancer in inflammatory bowel disease: a shift in risk? Expert Review of Anticancer Therapy. 2014;14(7):847–856. doi: 10.1586/14737140.2014.895936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hata K., Watanabe T., Kazama S., et al. Earlier surveillance colonoscopy programme improves survival in patients with ulcerative colitis associated colorectal cancer: results of a 23-year surveillance programme in the Japanese population. British Journal of Cancer. 2003;89(7):1232–1236. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim B. J., Yang S. K., Kim J. S., et al. Trends of ulcerative colitis-associated colorectal cancer in Korea: a KASID study. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2009;24(4):667–671. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2008.05730.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gong W., Lv N., Wang B., et al. Risk of ulcerative colitis-associated colorectal cancer in China: a multi-center retrospective study. Digestive Diseases and Sciences. 2012;57(2):503–507. doi: 10.1007/s10620-011-1890-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matsuoka H., Ikeuchi H., Uchino M., et al. Clinicopathological features of ulcerative colitis-associated colorectal cancer pointing to efficiency of surveillance colonoscopy in a large retrospective Japanese cohort. International Journal of Colorectal Disease. 2013;28(6):829–834. doi: 10.1007/s00384-012-1592-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang Q., Sha S., Xu B., Liang S., Wu K. Prevalence of colorectal cancer in patients with ulcerative colitis: a retrospective, monocenter study in China. Journal of Cancer Research and Therapeutics. 2015;11(4):899–903. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.143345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee H. S., Park S. H., Yang S. K., et al. The risk of colorectal cancer in inflammatory bowel disease: a hospital-based cohort study from Korea. Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology. 2015;50(2):188–196. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2014.989538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Choi J. K., Kim D. W., Shin S. Y., Park E. C., Kang J. G. Effect of ulcerative colitis on incidence of colorectal cancer: results from the nationwide population-based cohort study (2003-2013) Journal of Cancer. 2016;7(6):681–686. doi: 10.7150/jca.14264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shi H. Y., Chan F. K. L., Leung W. K., et al. Natural history of elderly-onset ulcerative colitis: results from a territory-wide inflammatory bowel disease registry. Journal of Crohn's and Colitis. 2016;10(2):176–185. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjv194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yoshino T., Nakase H., Takagi T., et al. Risk factors for developing colorectal cancer in Japanese patients with ulcerative colitis: a retrospective observational study—CAPITAL (Cohort and Practice for IBD total management in Kyoto-Shiga Links) study I. BMJ Open Gastroenterology. 2016;3(1, article e000122) doi: 10.1136/bmjgast-2016-000122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang L. H., Yang Y. J., Cheng W. C., Wang W. M., Lin S. H., Shieh C. C. Higher risk for hematological malignancies in inflammatory bowel disease: a nationwide population-based study in Taiwan. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2016;111(9):1313–1319. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2016.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jung Y. S., Han M., Park S., Kim W. H., Cheon J. H. Cancer risk in the early stages of inflammatory bowel disease in Korean patients: a nationwide population-based study. Journal of Crohn's and Colitis. 2017;11(8):954–962. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjx040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kishikawa J., Hata K., Kazama S., et al. Results of a 36-year surveillance program for ulcerative colitis-associated neoplasia in the Japanese population. Digestive Endoscopy. 2018;30(2):236–244. doi: 10.1111/den.12955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bopanna S., Kedia S., Das P., et al. Long-term follow-up reveals high incidence of colorectal cancer in Indian patients with inflammatory bowel disease. United European Gastroenterology Journal. 2017;5(5):708–714. doi: 10.1177/2050640616680552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Selinger C. P., Andrews J. M., Titman A., et al. Long-term follow-up reveals low incidence of colorectal cancer, but frequent need for resection, among Australian patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2014;12(4):644–650. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gupta R. B., Harpaz N., Itzkowitz S., et al. Histologic inflammation is a risk factor for progression to colorectal neoplasia in ulcerative colitis: a cohort study. Gastroenterology. 2007;133(4):1099–1105. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jess T., Loftus E. V., Jr., Velayos F. S., et al. Risk of intestinal cancer in inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based study from Olmsted County, Minnesota. Gastroenterology. 2006;130(4):1039–1046. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bitton A., Vutcovici M., Sewitch M., Suissa S., Brassard P. Mortality trends in Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis: a population-based study in Québec, Canada. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 2016;22(2):416–423. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hou J. K., Kramer J. R., Richardson P., Mei M., el-Serag H. B. Risk of colorectal cancer among Caucasian and African American veterans with ulcerative colitis. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 2012;18(6):1011–1017. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ananthakrishnan A. N., Cagan A., Cai T., et al. Statin use is associated with reduced risk of colorectal cancer in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2016;14(7):973–979. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2016.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Navaneethan U., Jegadeesan R., Gutierrez N. G., et al. Progression of low-grade dysplasia to advanced neoplasia based on the location and morphology of dysplasia in ulcerative colitis patients with extensive colitis under colonoscopic surveillance. Journal of Crohn's and Colitis. 2013;7(12):e684–e691. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2013.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ananthakrishnan A. N., Cagan A., Cai T., et al. Colonoscopy is associated with a reduced risk for colon cancer and mortality in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2015;13(2):322–329.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sonnenberg A., Genta R. M. Epithelial dysplasia and cancer in IBD strictures. Journal of Crohn's and Colitis. 2015;9(9):769–775. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjv108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hou J. K., Feagins L. A., Waljee A. K. Characteristics and behavior of elderly-onset inflammatory bowel disease: a multi-center US study. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 2016;22(9):2200–2205. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bettner W., Rizzo A., Brant S., et al. Low incidence of dysplasia and colorectal cancer observed among inflammatory bowel disease patients with prolonged colonic diversion. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 2018;24(5):1092–1098. doi: 10.1093/ibd/izx102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moody G. A., Jayanthi V., Probert C. S. J., Kay H. M., Mayberry J. F. Long-term therapy with sulphasalazine protects against colorectal cancer in ulcerative colitis: a retrospective study of colorectal cancer risk and compliance with treatment in Leicestershire. European Journal of Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 1996;8(12):1179–1183. doi: 10.1097/00042737-199612000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ekbom A., Helmick C., Zack M., Adami H. O. Ulcerative colitis and colorectal cancer — a population-based study. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1990;323(18):1228–1233. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199011013231802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lennard-Jones J. E., Melville D. M., Morson B. C., Ritchie J. K., Williams C. B. Precancer and cancer in extensive ulcerative colitis: findings among 401 patients over 22 years. Gut. 1990;31(7):800–806. doi: 10.1136/gut.31.7.800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Löfberg R., Broström O., Karlén P., Tribukait B., Öst Å. Colonoscopic surveillance in long-standing total ulcerative colitis a 15-year follow-up study. Gastroenterology. 1990;99(4):1021–1031. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(90)90622-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stewénius J., Adnerhill I., Anderson H., et al. Incidence of colorectal cancer and all cause mortality in non-selected patients with ulcerative colitis and indeterminate colitis in Malmö, Sweden. International Journal of Colorectal Disease. 1995;10(2):117–122. doi: 10.1007/BF00341210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Biasco G., Brandi G., Paganelli G. M., et al. Colorectal cancer in patients with ulcerative colitis a prospective cohort study in Italy. Cancer. 1995;75(8):2045–2050. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19950415)75:8<2045::AID-CNCR2820750803>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wandall E. P., Damkier P., Møller Pedersen F., Wilson B., Schaffalitzky de Muckadell O. B. Survival and incidence of colorectal cancer in patients with ulcerative colitis in Funen County diagnosed between 1973 and 1993. Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology. 2000;35(3):312–317. doi: 10.1080/003655200750024209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Palli D., Trallori G., Saieva C., et al. General and cancer specific mortality of a population based cohort of patients with inflammatory bowel disease: the Florence study. Gut. 1998;42(2):175–179. doi: 10.1136/gut.42.2.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Winther K. V., Jess T., Langholz E., Munkholm P., Binder V. Survival and cause-specific mortality in ulcerative colitis: follow-up of a population-based cohort in Copenhagen County. Gastroenterology. 2003;125(6):1576–1582. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.09.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Viscido A., Bagnardi V., Sturniolo G. C., et al. Survival and causes of death in Italian patients with ulcerative colitis a GISC∗ nation-wide study. Digestive and Liver Disease. 2001;33(8):686–692. doi: 10.1016/S1590-8658(01)80046-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Goldacre M. J., Wotton C. J., Yeates D., Seagroatt V., Jewell D. Cancer in patients with ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease and coeliac disease: record linkage study. European Journal of Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 2008;20(4):297–304. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e3282f2a5e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lindberg J., Stenling R., Palmqvist R., Rutegård J. Efficiency of colorectal cancer surveillance in patients with ulcerative colitis: 26 years’ experience in a patient cohort from a defined population area. Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology. 2005;40(9):1076–1080. doi: 10.1080/00365520510023224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jess T., Horváth-Puhó E., Fallingborg J., Rasmussen H. H., Jacobsen B. A. Cancer risk in inflammatory bowel disease according to patient phenotype and treatment: a Danish population-based cohort study. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2013;108(12):1869–1876. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hemminki K., Li X., Sundquist J., Sundquist K. Cancer risks in ulcerative colitis patients. International Journal of Cancer. 2008;123(6):1417–1421. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Katsanos K. H., Christodoulou D. K., Michael M., et al. Inflammatory bowel disease-related dysplasia and cancer: a referral center study in northwestern Greece. European Journal of Internal Medicine. 2005;16(3):170–175. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2004.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Katsanos K. H., Vermeire S., Christodoulou D. K., et al. Dysplasia and cancer in inflammatory bowel disease 10 years after diagnosis: results of a population-based European collaborative follow-up study. Digestion. 2007;75(2-3):113–121. doi: 10.1159/000104731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jess T., Riis L., Vind I., et al. Changes in clinical characteristics, course, and prognosis of inflammatory bowel disease during the last 5 decades: a population-based study from Copenhagen, Denmark. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 2007;13(4):481–489. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stolwijk J. A. M., Langers A. M. J., Hardwick J. C., et al. A thirty-year follow-up surveillance study for neoplasia of a Dutch ulcerative colitis cohort. ScientificWorldJournal. 2013;2013, article 274715:7. doi: 10.1155/2013/274715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lakatos L., Mester G., Erdelyi Z., et al. Risk factors for ulcerative colitis-associated colorectal cancer in a Hungarian cohort of patients with ulcerative colitis: results of a population-based study. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 2006;12(3):205–211. doi: 10.1097/01.MIB.0000217770.21261.ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cheddani H., Dauchet L., Fumery M., et al. Cancer in elderly onset inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based study. The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2016;111(10):1428–1436. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2016.304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Manninen P., Karvonen A. L., Huhtala H., et al. The risk of colorectal cancer in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases in Finland: a follow-up of 20 years. Journal of Crohn's and Colitis. 2013;7(11):e551–e557. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2013.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jess T., Simonsen J., Jørgensen K. T., Pedersen B. V., Nielsen N. M., Frisch M. Decreasing risk of colorectal cancer in patients with inflammatory bowel disease over 30 years. Gastroenterology. 2012;143(2):375–381.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gordillo J., Zabana Y., Garcia-Planella E., et al. Prevalence and risk factors for colorectal adenomas in patients with ulcerative colitis. United European Gastroenterology Journal. 2018;6(2):322–330. doi: 10.1177/2050640617718720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kappelman M. D., Farkas D. K., Long M. D., et al. Risk of cancer in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases: a nationwide population-based cohort study with 30 years of follow up evaluation. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2014;12(2):265–273.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.03.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Choi C.-H. R., Rutter M. D., Askari A., et al. Forty-year analysis of colonoscopic surveillance program for neoplasia in ulcerative colitis: an updated overview. The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2015;110(7):1022–1034. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2015.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Choi C.-H. R., al Bakir I., Ding N. S. (. J.)., et al. Cumulative burden of inflammation predicts colorectal neoplasia risk in ulcerative colitis: a large single-centre study. Gut. 2019;68(3):414–422. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2017-314190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hovde Ø., Høivik M. L., Henriksen M., Solberg I. C., Småstuen M. C., Moum B. A. Malignancies in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: results from 20 years of follow-up in the IBSEN study. Journal of Crohn's and Colitis. 2017;11(5):571–577. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjw193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.van den Heuvel T. R. A., Wintjens D. S. J., Jeuring S. F. G., et al. Inflammatory bowel disease, cancer and medication: cancer risk in the Dutch population-based IBDSL cohort. International Journal of Cancer. 2016;139(6):1270–1280. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nowacki T. M., Brückner M., Eveslage M., et al. The risk of colorectal cancer in patients with ulcerative colitis. Digestive Diseases and Sciences. 2015;60(2):492–501. doi: 10.1007/s10620-014-3373-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rutegård M., Palmqvist R., Stenling R., Lindberg J., Rutegård J. Efficiency of colorectal cancer surveillance in patients with ulcerative colitis: 38 years’ experience in a patient cohort from a defined population area. Scandinavian Journal of Surgery. 2017;106(2):133–138. doi: 10.1177/1457496916659224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Biancone L., Armuzzi A., Scribano M. L., et al. Inflammatory bowel disease phenotype as risk factor for cancer in a prospective multicentre nested case-control IG-IBD study. Journal of Crohn's and Colitis. 2016;10(8):913–924. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjw048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kekilli M., Dagli U., Kalkan I. H., et al. Low incidence of colorectal dysplasia and cancer among patients with ulcerative colitis: a Turkish referral centre study. Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology. 2010;45(4):434–439. doi: 10.3109/00365520903540830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Keller D. S., Windsor A., Cohen R., Chand M. Colorectal cancer in inflammatory bowel disease: review of the evidence. Techniques in Coloproctology. 2019;23(1):3–13. doi: 10.1007/s10151-019-1926-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Marion J. F., Waye J. D., Israel Y., et al. Chromoendoscopy is more effective than standard colonoscopy in detecting dysplasia during long-term surveillance of patients with colitis. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2016;14(5):713–719. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Axelrad J. E., Roy A., Lawlor G., Korelitz B., Lichtiger S. Thiopurines and inflammatory bowel disease: current evidence and a historical perspective. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2016;22(46):10103–10117. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i46.10103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Andrade P., Lopes S., Coelho R., Terroso G., Lage J., Macedo G. Squamous cell carcinoma arising from a presacral cyst in a patient with ulcerative colitis under azathioprine and infliximab: first case report. International Journal of Colorectal Disease. 2016;31(8):1509–1510. doi: 10.1007/s00384-016-2519-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mooiweer E., van der Meulen-de Jong A., Ponsioen C. Y., et al. Incidence of interval colorectal cancer among inflammatory bowel disease patients undergoing regular colonoscopic surveillance. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2015;13(9):1656–1661. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.04.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kiesslich R., Neurath M. F. Advances in detection and management of dysplasia in inflammatory bowel disease: is endoscopic submucosal dissection ready for prime time in inflammatory bowel disease? Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2015;82(4):739–741. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2015.06.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The clinical data supporting this systematic review and meta-analysis are from previously reported studies and datasets, which have been cited. The processed data are available in Table 1 of our manuscript.